Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

- Newtonian mechanics for centrifugal acceleration,

- Relativistic dynamics through modifications to the Friedmann equation,

- Observational constraints from Planck and JWST-era data,

- Quranic verses indicating cosmic expansion and structure.

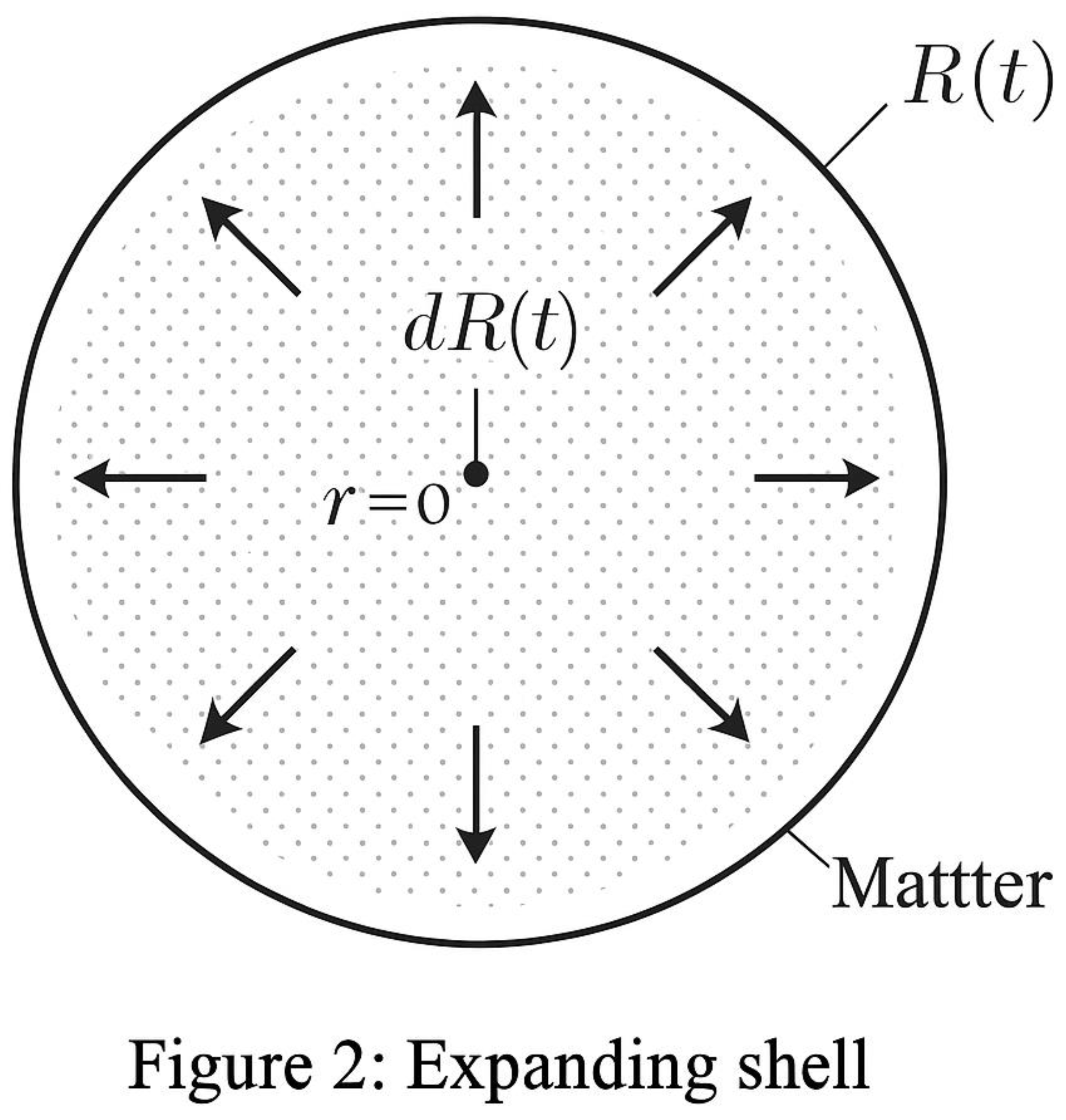

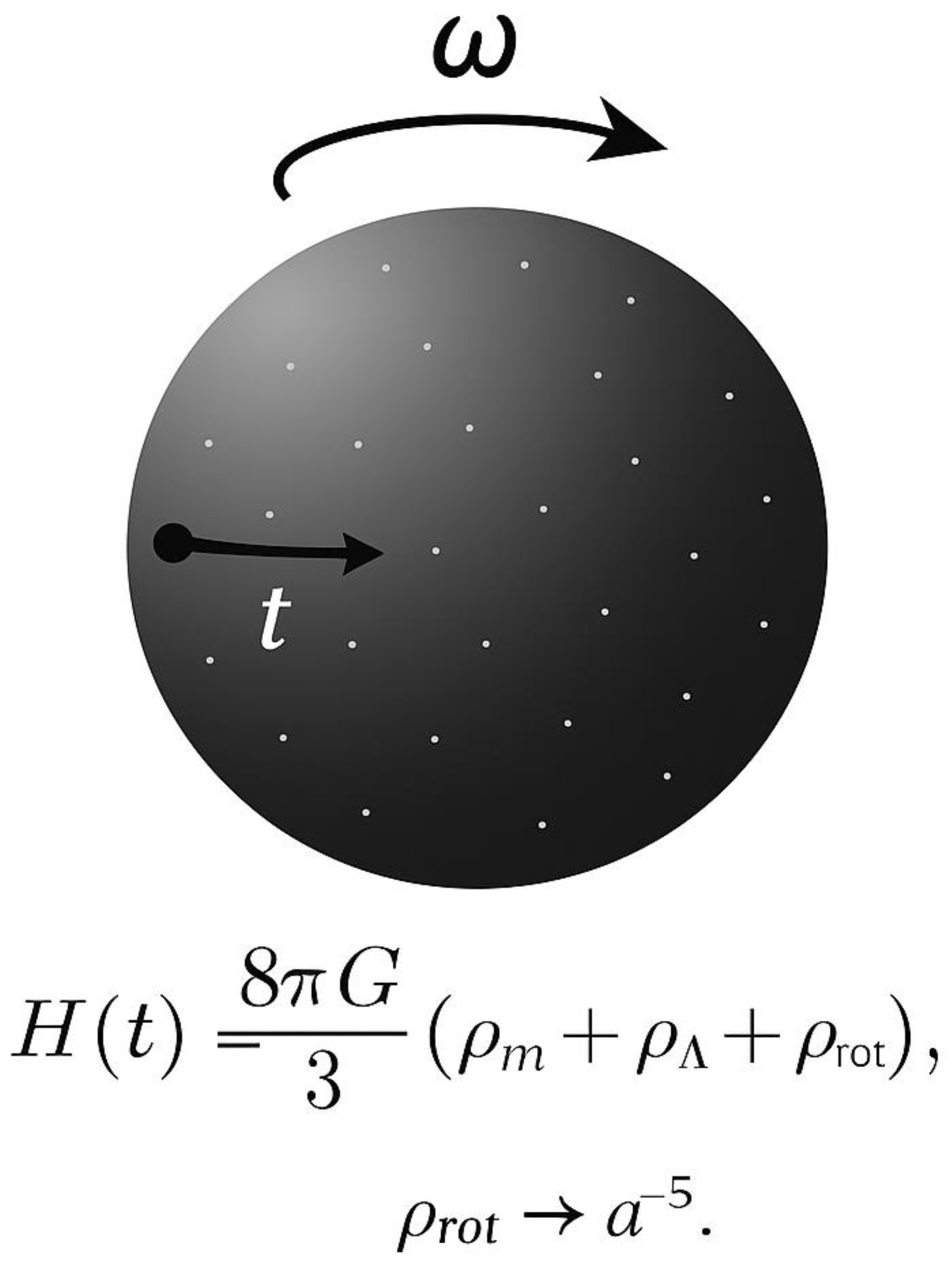

2. Rotational Model of Universal Expansion

2.1. Basic Newtonian Model

- is the centrifugal acceleration,

- is the angular velocity of the universe (in radians per second),

- is the physical radius from the axis of rotation.

2.2. Connection with Hubble Expansion

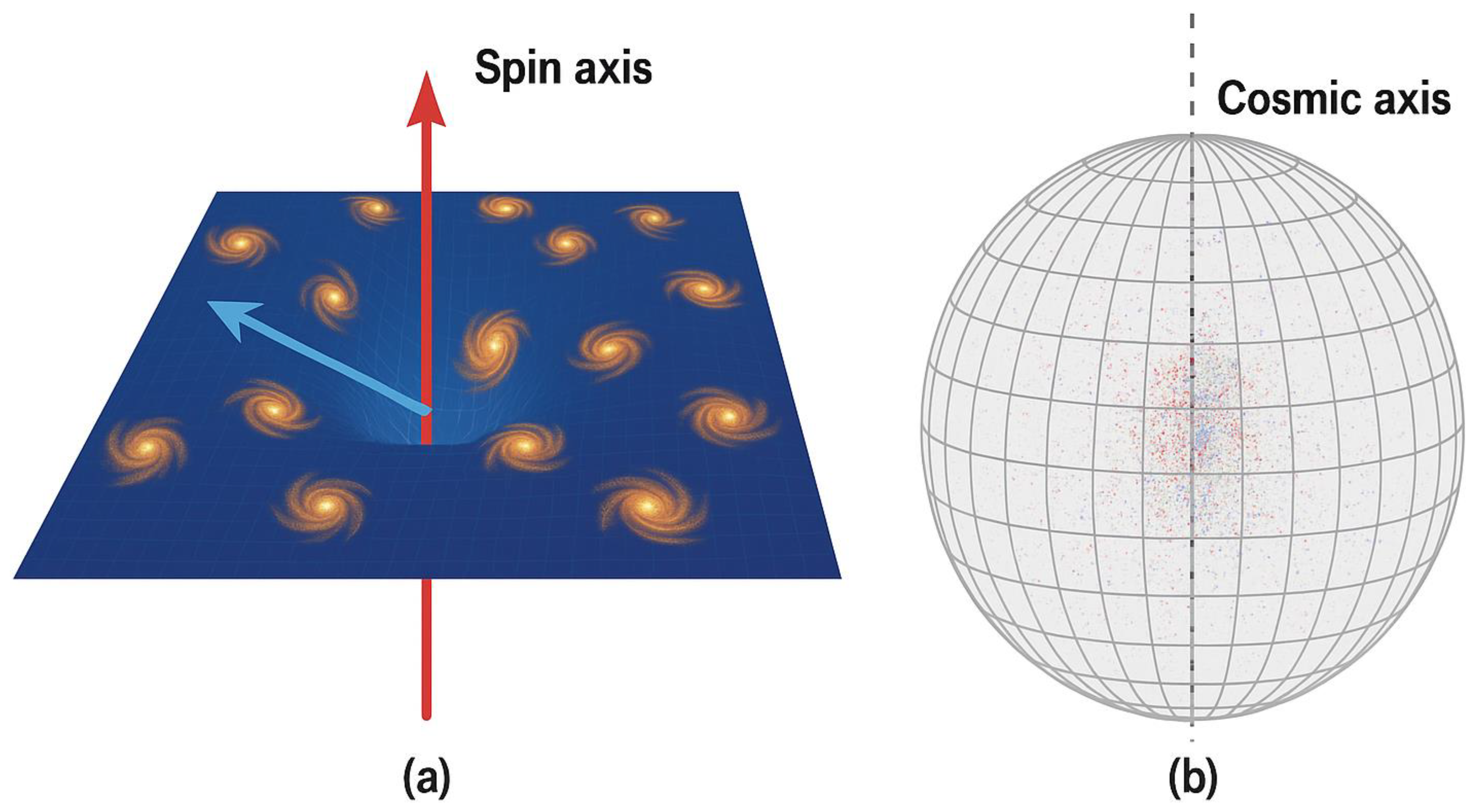

2.3. Directional Dependence and Anisotropy

- Maximal acceleration occurs in the equatorial plane (perpendicular to the axis).

- Zero acceleration occurs along the axis itself.

3. Newtonian Analysis of Rotational Expansion

3.1. Centrifugal Acceleration

- Angular velocity (approximate value of the Hubble constant),

- Distance (a galaxy ~10 billion light-years away).

3.2. Angular Momentum and Universe-Scale Rotation

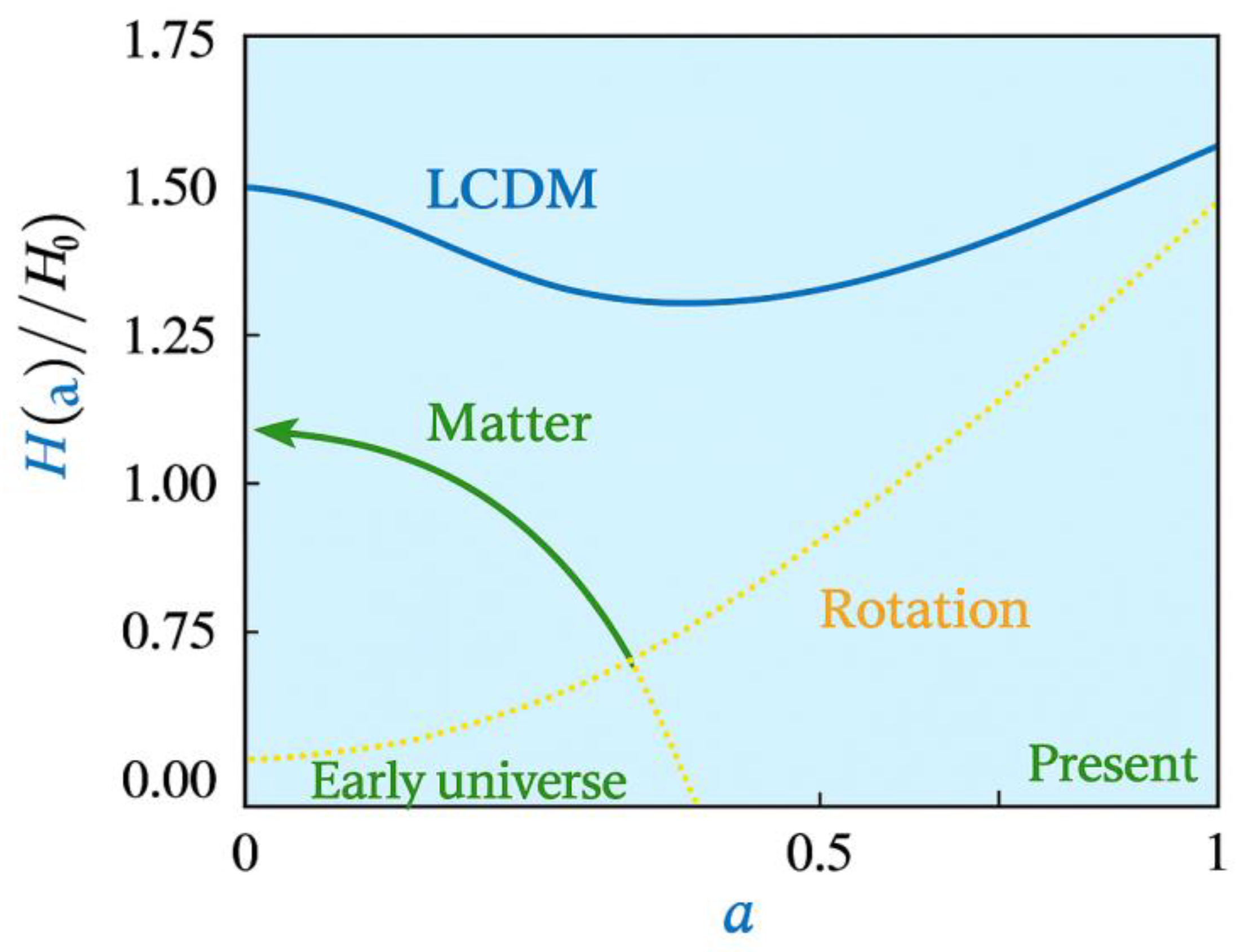

3.3. Effective Energy Density of Rotation

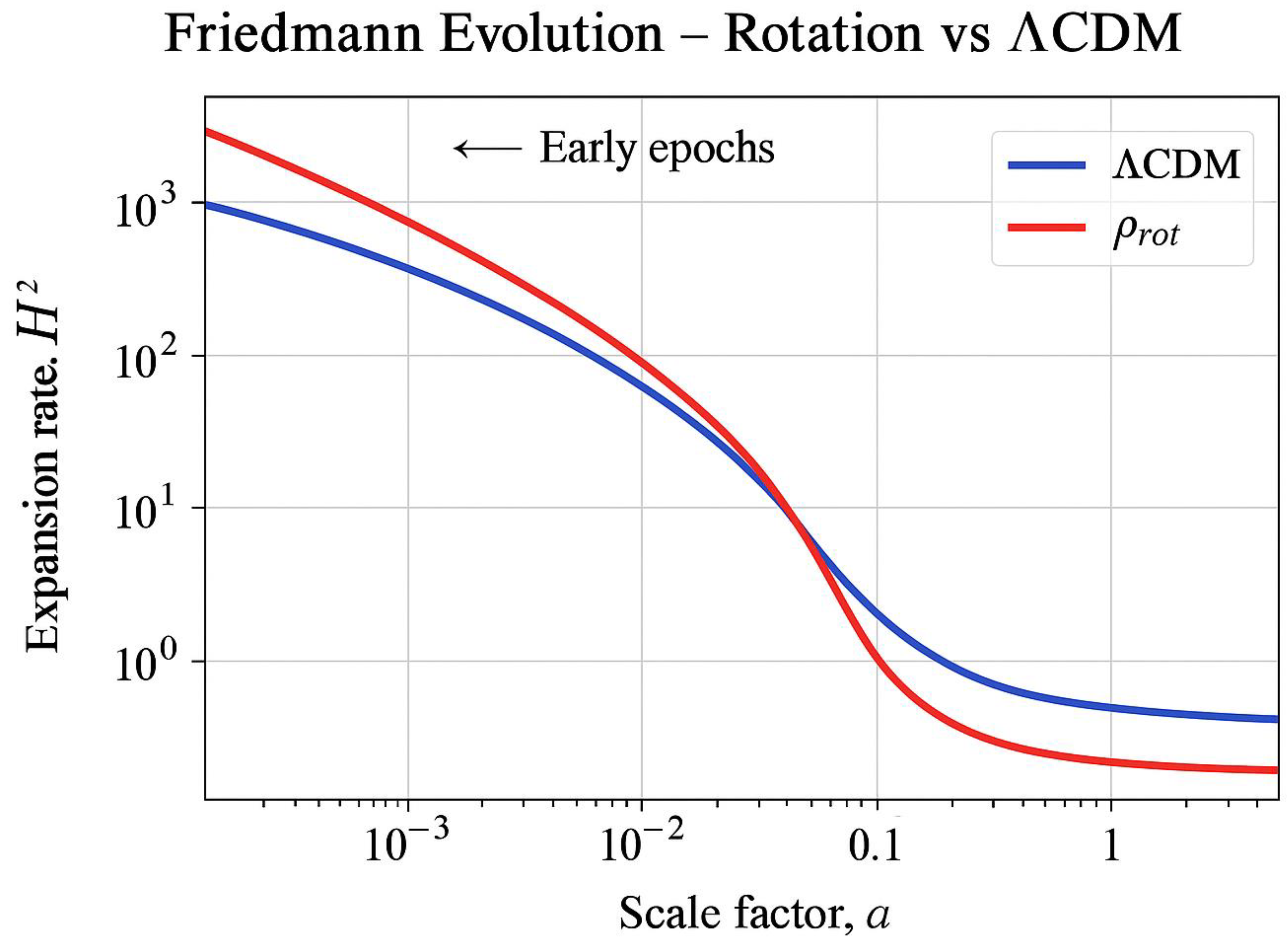

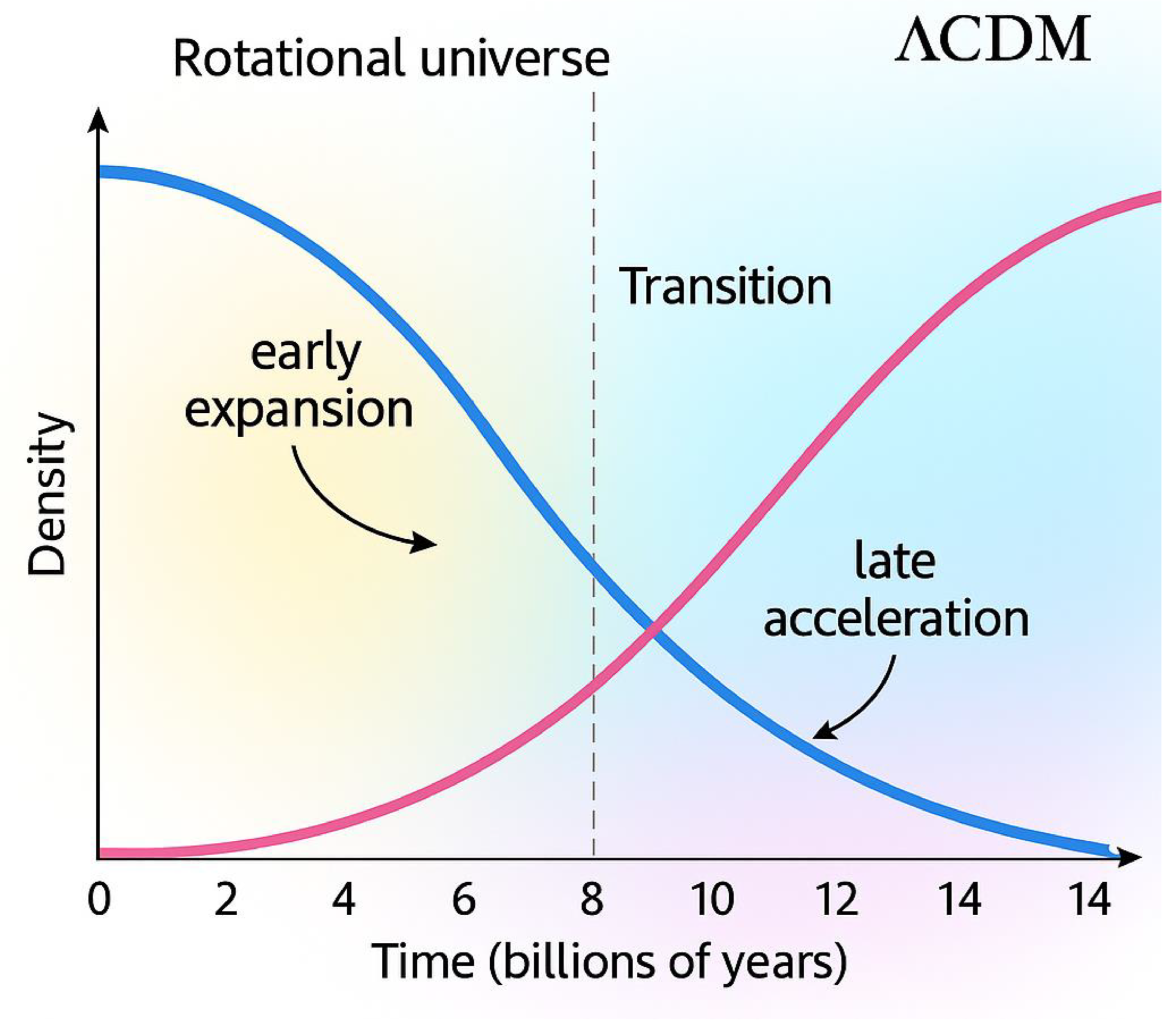

- Rotation could have dominated briefly after the Big Bang.

- Its influence would fade over time, avoiding conflict with today’s observations.

4. Relativistic Framework Using Einstein’s Field Equations

4.1. The Standard Friedmann Equation

- is the Hubble parameter (expansion rate),

- is the scale factor,

- is the gravitational constant,

- is the total energy density,

- is the spatial curvature parameter (0 for flat),

- is the speed of light.

4.2. Including Rotational Energy

- is the angular velocity (scales as ),

- is the matter density (scales as ),

- is the physical radius.

4.3. Contribution to Cosmic Acceleration

- For Λ: (accelerated expansion),

- For rotation: no pressure term, but effective acceleration arises from geometry.

5. Angular Momentum and Rotational Energy

5.1. Angular Momentum Conservation

- is the moment of inertia,

- is the angular velocity.

5.2. Rotational Energy Evolution

- Rotational energy per unit volume drops faster than radiation (),

- Its contribution was only significant at small scale factors, i.e. in the early universe.

5.3. Maximum Allowable Angular Speed

6. Observed Acceleration vs Rotational Contribution

- Fully replace the cosmological constant (Λ),

- Partially supplement it,

- Or simply serve as a mathematically consistent but observationally negligible correction.

6.1. Dark Energy Acceleration Scale

- ,

- ,

6.2. Rotational Acceleration Estimate

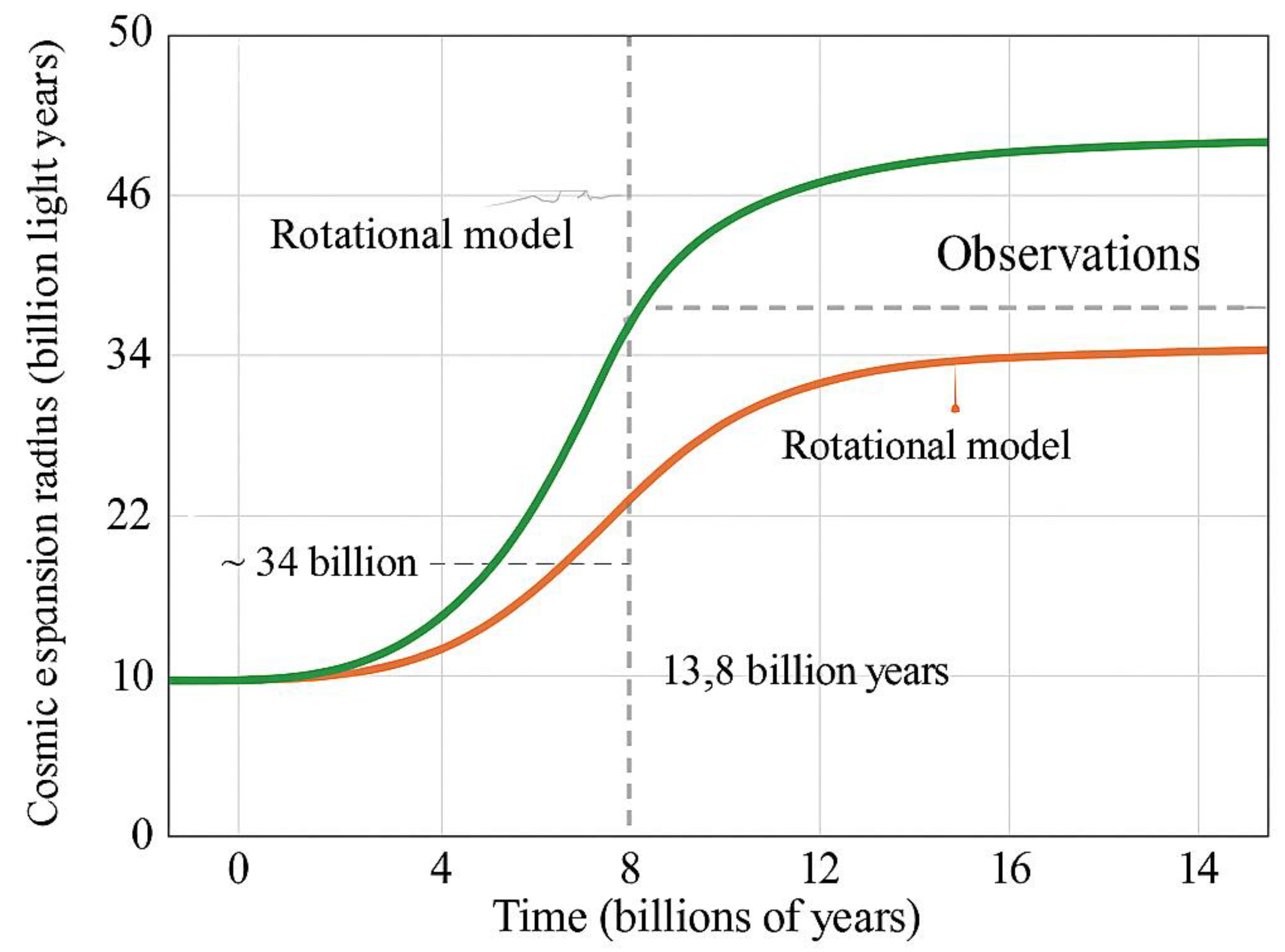

6.3. Cosmic Expansion Radius: Observational vs Model

- ΛCDM requires a constant energy density to sustain expansion at this scale,

- Rotational models must combine with other early-universe phenomena (like inflation) to explain the full cosmic size.

7. ROLE OF AN EXTERNAL FORCE

7.1. Conservation of Angular Momentum and Origin of Rotation

- Initial asymmetry in the distribution of matter-energy at or before the Big Bang,

- A rotating inflationary field that imparted spin during rapid early expansion,

- A topological property of higher-dimensional spacetime,

- Or, from a philosophical or theological view, a divine origin — the rotation is inherent by design.

7.2. Rotation Without Torque – Is It Possible?

- The frame-dragging effect seen near rotating massive objects (e.g., Kerr black holes) is a demonstration of how spacetime can rotate locally,

- Similarly, on cosmological scales, a global vorticity can be encoded into the spacetime metric without requiring an external torque [Obukhov, 2000] [11].

7.3. Quranic Implications and Interpretation

“And it is He who created the night and the day and the sun and the moon; all [heavenly bodies] in an orbit are swimming.”— Surah Al-Anbiya (21:33)

8. Comparison of Newtonian and Relativistic Results

8.1. Acceleration and Angular Velocity

| Parameter | Newtonian Model | Relativistic Model |

| Acceleration | ||

| Energy Density Scaling | Same, derived from fluid + metric assumptions | |

| Angular Velocity Scaling | , via angular momentum conservation | |

| Force Source | Centrifugal force from mass | Geometric effect from rotating spacetime |

| Constraints | Avoidance of closed time-like curves, causality limits | |

| Observable Prediction | Directional redshift anisotropy | CMB dipole/quadrupole, Bianchi-type signatures |

8.2. Observational Effects: Consistency Between Models

- Anisotropic expansion, more prominent in the equatorial plane than along the rotation axis,

- Directional variations in galaxy recession velocities,

- Potential alignment in CMB patterns (dipole/quadrupole modes),

- Preferred orientation in large-scale structure (e.g., galaxy spin alignments).

8.3. Limitations of Newtonian View

- Gravitational lensing effects,

- Time dilation and redshift due to curvature,

- The distinction between coordinate motion and geodesic motion in expanding space.

9. Quranic Perspective on Cosmic Expansion

9.1. Continuous Expansion

"And the heaven We constructed with strength, and indeed, We are [its] expander."Surah Adh-Dhariyat (51:47)

9.2. Structured and Layered Heavens

"It is He who created seven heavens in layers. You do not see in the creation of the Most Merciful any inconsistency."Surah Al-Mulk (67:3)

- Multiverse theories (stacked dimensions),

- Layered gravitational shells in a rotating model,

- Bianchi-type cosmologies that permit anisotropic yet layered solutions.

9.3. Rotational Motion Implied in Orbits

"Each [heavenly body] is swimming along in its orbit."Surah Ya-Sin (36:40)

"They all float, each in an orbit."Surah Al-Anbiya (21:33)

9.4. Divine Origin of Motion

"He created the heavens and the earth in truth. He wraps the night over the day and wraps the day over the night."Surah Az-Zumar (39:5)

9.5. Synthesis with Rotational Cosmology

- The universe is continuously expanding (Surah 51:47),

- It is structured in layers or shells (Surah 67:3),

- Rotational motion is a foundational cosmic principle (Surah 36:40, 21:33),

- Such motion is a deliberate creation of Allah (Surah 39:5).

10. Section X: Conceptual Origin of the Rotating Universe Theory

10.1. Universal Motion as Sujood (Prostration)

“Do you not see that to Allah prostrates whoever is in the heavens and whoever is on the earth, and the sun, the moon, the stars, the mountains, the trees, the moving creatures and many of the people?”— Surah Al-Hajj (22:18)

- Planets revolve around stars,

- Stars orbit galactic centers,

- Galaxies rotate and migrate through cosmic filaments,

- Even subatomic particles revolve in quantized states.

10.2 The Seed of the Rotational Model

“And each [heavenly body] is swimming along in its orbit.”—Surah Ya-Sin (36:40)

“And the heaven, We constructed it with strength, and verily, We are [its] expander.”—Surah Adh-Dhariyat (51:47)

10.3 Philosophy Elevated by Physics

- Observational hints of a cosmic axis,

- Theoretical solutions like Gödel’s rotating universe,

- And relativistic frameworks (e.g. Bianchi models) that mathematically permit rotation.

10.4 Quranic Symmetry and the Laws of Physics

“And the heaven He raised and imposed the balance (mīzān).”— Surah Ar-Rahman (55:7)

- The orbits of planets are balanced by gravity and inertia.

- The spin of electrons is quantized and balanced within atoms.

- The expansion of the universe itself is delicately balanced between gravity and cosmic acceleration.

10.5 Sujood and Curved Paths

- The Earth’s curved path around the sun is due to submission to gravity.

- A rotating galaxy curves under its own gravitational field.

- Even light bends in curved space-time, “submitting” to the gravitational field of massive bodies.

10.6 The Quran as a Source of Scientific Foresight

- Layered dimensions (67:3),

- Expansion (51:47),

- Universal motion (36:40),

- And obedience through motion (22:18).

- Movement,

- Obedience,

- Structure,

- Expansion.

10.7 How This Concept Shaped the Entire Research Direction

- The Quranic verses were taken as the starting point,

- Reflected upon deeply,

- And then mapped scientifically using tools of modern physics.

- If celestial bodies orbit as an act of obedience,

- And if expansion is explicitly mentioned in the Quran,

- Then could expansion itself be a result of rotation, ordained from creation?

- Rotation may not just be a secondary motion but the driving cause of expansion,

- The universe could be curved outward by centrifugal effects,

- And dark energy might be explained, at least partially, by such dynamics.

10.8 A Call to Reflect and Re-Evaluate Origins of Knowledge

- Newton believed in divine order.

- Einstein famously said: “God does not play dice.”

- Muslim scientists like Ibn al-Haytham, Al-Biruni, and Al-Tusi grounded their work in the Quran.

“Do they not reflect upon the creation of the heavens and the earth?”— Surah Sad (38:27)

10.9 Final Reflection: The Universe in Sujood

“And to Allah prostrates whatever is in the heavens and the earth...”— Surah Ar-Ra’d (13:15)

- Each curved geodesic is a bow to the center of gravity,

- Each expansion of space is an obedience to a higher command,

- Each spin of a galaxy is a silent dhikr written in light-years.

10.10. Closing Reflection

- That the truths of the cosmos and the truths of the Quran are not two separate paths —

- They are parallel orbits, revolving around the same Center.

- When the stars expand, they obey.

- And when we observe them with humility, we too enter into sujood —

- not with our bodies, but with our minds.

11. Conclusions

- Mathematically, rotational acceleration produces a repulsive effect similar in magnitude (if ) to that caused by dark energy.

- Energetically, rotational contributions scale with , meaning they were stronger in the early universe but decay rapidly — making them consistent with current isotropy observations.

- Relativistically, inclusion of -dependent terms into the Friedmann equation provides an effective acceleration term , analogous to the effect of Λ.

- Observationally, recent studies (2023–2025) show that a small rotation (e.g. ) could potentially resolve the Hubble tension without violating Planck or supernova constraints.

- Scripturally, several Quranic verses describe an expanding, structured, and motion-filled universe — consistent with the physical properties expected in a rotational model.

- Rotation alone cannot fully replace the role of dark energy, but it may serve as a natural supplement, especially during mid-era cosmological epochs.

- The origin of rotation — whether physical (e.g., from inflation or initial asymmetry) or metaphysical (a divine design) — remains an open and profound question.

Final Thoughts

References

- Hubble, E. (1929). A Relation Between Distance and Radial Velocity Among Extra-Galactic Nebulae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 15(3), 168–173. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. (1989). The Cosmological Constant Problem. Reviews of Modern Physics, 61(1), 1–23.

- Riess, A. G., et al. (2019). Large Magellanic Cloud Cepheid Standards Provide a 1% Foundation for the Determination of the Hubble Constant. The Astrophysical Journal, 876(1), 85. [CrossRef]

- Szigeti, B. E., Szapudi, I., Barna, I. F., & Barnaföldi, G. G. (2025). Can Rotation Solve the Hubble Puzzle? Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 538, 3038–3044.

- Pál, B., Goh, T., Rácz, G., et al. (2025). Simulating Rotating Newtonian Universes. European Physical Journal Special Topics, 234(8), 1681–1693.

- Saadeh, D., et al. (2016). How Isotropic Is the Universe? Constraints on Rotation and Shear from the Planck Satellite. Physical Review Letters, 117, 131302.

- Campanelli, L., Cea, P., & Tedesco, L. (2011). Cosmological Axis of Evil Revisited. Modern Physics Letters A, 26, 1169–1181.

- Weinberg, S. (2008). Cosmology. Oxford University Press.

- Barnaföldi, G. G., Szigeti, B. E., & Szapudi, I. (2025). Inflation and Rotation: Hybrid Solutions to Early- and Late-Time Acceleration. Preprint.

- Gödel, K. (1949). An Example of a New Type of Cosmological Solution of Einstein’s Field Equations of Gravitation. Reviews of Modern Physics, 21, 447–450. [CrossRef]

- Obukhov, Y. N. (2000). On Physical Foundations and Observational Effects of Cosmic Rotation. In Scherfner et al. (Eds.), Colloquium on Cosmic Rotation. Springer.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).