1. Introduction

The General Theory of Relativity (GR), developed by Albert Einstein, fundamentally altered our conception of gravity [

1]. In Einstein’s formulation [

2,

3,

4,

5], space and time are no longer fixed backgrounds but dynamic quantities determined by the distribution of matter and energy.

In this framework, gravity is not a classical force but a manifestation of the curvature of spacetime, governed by the stress–energy tensor of matter and energy. Einstein geometrized the stress–energy tensor by relating it directly to the Einstein tensor , a quantity that encapsulates the geometric properties of spacetime itself. Spacetime thus influences the motion of matter and energy, while matter and energy, in turn, alter the structure of spacetime. This deep interplay means that space and time emerge as dynamic participants in the evolution of the universe, rather than inert stages.

Geometrizing all fundamental interactions extends beyond gravity [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In classical electrodynamics, the electromagnetic field—described by the antisymmetric field tensor

—is traditionally treated as an independent entity governed by Maxwell’s equations. However, the possibility arises of incorporating the stress–energy tensor of electromagnetic field directly into the fabric of spacetime geometry.

Much like the stress–energy tensor describes the influence of matter on spacetime curvature, the electromagnetic stress–energy tensor captures the distribution and flow of electromagnetic energy and momentum. The electromagnetic stress–energy tensor is denoted as . One possible path toward geometrization involves formulating the electromagnetic field as a geometric property of spacetime, rather than an external field residing within it.

Nonetheless, achieving a full geometrization of electromagnetism poses significant challenges. The mathematical structures of general relativity and classical electrodynamics differ fundamentally, and unifying them within a single geometric framework remains an open problem.

A complete geometrization of matter, energy, and fundamental fields within general relativity would represent a profound advance: the laws of physics would no longer describe forces acting across a preexisting stage, but rather express the intrinsic structure of spacetime itself. Time, too, could appear as an emergent aspect of the spacetime geometry.

Despite considerable efforts since Einstein’s era, it remains unclear what form a fully unified field theory—encompassing both general relativity and quantum theory—would ultimately take. The unification of gravity with electromagnetism, and beyond that with the other fundamental interactions, continues to stand as one of the greatest and most elusive goals in modern theoretical physics.

Definitions

In the context of modern physics, definitions serve as the foundation for constructing precise mathematical models that describe the natural world, ensuring consistency and clarity in theoretical frameworks. These definitions not only provide operational guidelines for measurements but also guide the development of new theories, offering insights into the fundamental structure of reality.

Definition 1

(Speed of the light in vacuum c).

Let

c denote the speed of light in a vacuum. The exact value of the speed of light in vacuum is defined by the International System of Units (SI) as

Definition 2

(Newton’s Constant G).

Newton’s gravitational constant, commonly denoted by

G, is the fundamental physical constant that quantifies the strength of the gravitational interaction between two masses. It appears in Newton’s law of universal gravitation:

where

F is the force of attraction between two point masses

and

, separated by a distance

r. The constant

G has the SI units

and determines the proportionality between gravitational force and mass. Although Newton himself did not introduce the constant

G explicitly, the law originates from his

Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), where the inverse-square nature of gravity was first formulated [

1, p. 198].

Definition 3

(Archimedes’ constant ).

The constant

or Archimedes’ constant is naturally defined in Euclidean geometry as the ratio of a circle’s circumference, U, to its diameter, d. It is,

where:

h is Planck’s constant [

11,

12],

ℏ is Dirac’s constant, another name for the reduced Planck constant, typically denoted by this symbol [

13].

The ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse (c. 287 BCE – c. 212 BCE) was one of the first to rigorously estimate the value of with high accuracy.

Definition 4

(Planck’s Constant h).

Planck’s constant [

11,

12] h signifies the quantization of energy levels in atomic and subatomic systems, meaning that energy can only be gained or lost in discrete amounts or quanta.

The exact value of Planck’s constant

h as fixed by the International System of Units (SI) in 2019 as:

Definition 5

(The Einstein field equations).

The fundamental relation between geometry and matter is encoded in the Einstein field equations as:

where

is the Ricci tensor,

R the Ricci scalar,

the metric tensor,

the cosmological constant, and

G the gravitational constant.

Definition 6

(Four Fundamental Fields of Nature).

The four fundamental fields of nature, denoted as

, determine the Ricci tensor

formally as follows:

where:

is the

Ricci tensor, representing the curvature of spacetime,

is the

stress-energy tensor of ordinary matter,

is the

stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field,

is a

tensor of unknown structure, potentially representing an additional physical field,

is another

tensor of unknown structure, possibly accounting for yet undiscovered interactions. At this stage, the tensorial structure of these tensors remains open.

Tensor Algebra

A deeper and more comprehensive theory of gravitation should extend beyond the mathematical framework of general relativity, opening new possibilities for unifying gravitation with other fundamental interactions, such as electromagnetism. In this context, Einstein proposed replacing the symmetric tensor field with a non-symmetric one.

“The theory we are looking for must therefore be a generalization of the theory of the gravitational field. The first question is: What is the natural generalization of the symmetrical tensor field? ... What generalization of the field is going to provide the most natural theoretical system? The answer ... is that the symmetrical tensor field must be replaced by a non-symmetrical one. This means that the condition

for the field components must be dropped.” [

21]

Geometry itself can be traced back to humanity’s earliest efforts at systematic logical thinking. However, the relationship between definitions, axioms, theorems, and proofs within a geometric system and objective reality remains a subject of deeper exploration. Tensors [

22, p. 20] provide one mathematical framework [

23] to understand geometry. Notably, Einstein’s theory of general relativity is formulated using tensor mathematics. With these considerations in mind, we aim to further develop the tensor algebra in a more general framework.

Definition 7

(Tensor addition).

The sum of two second rank co-variant tensors has the properties of associativity and commutativity and is defined as

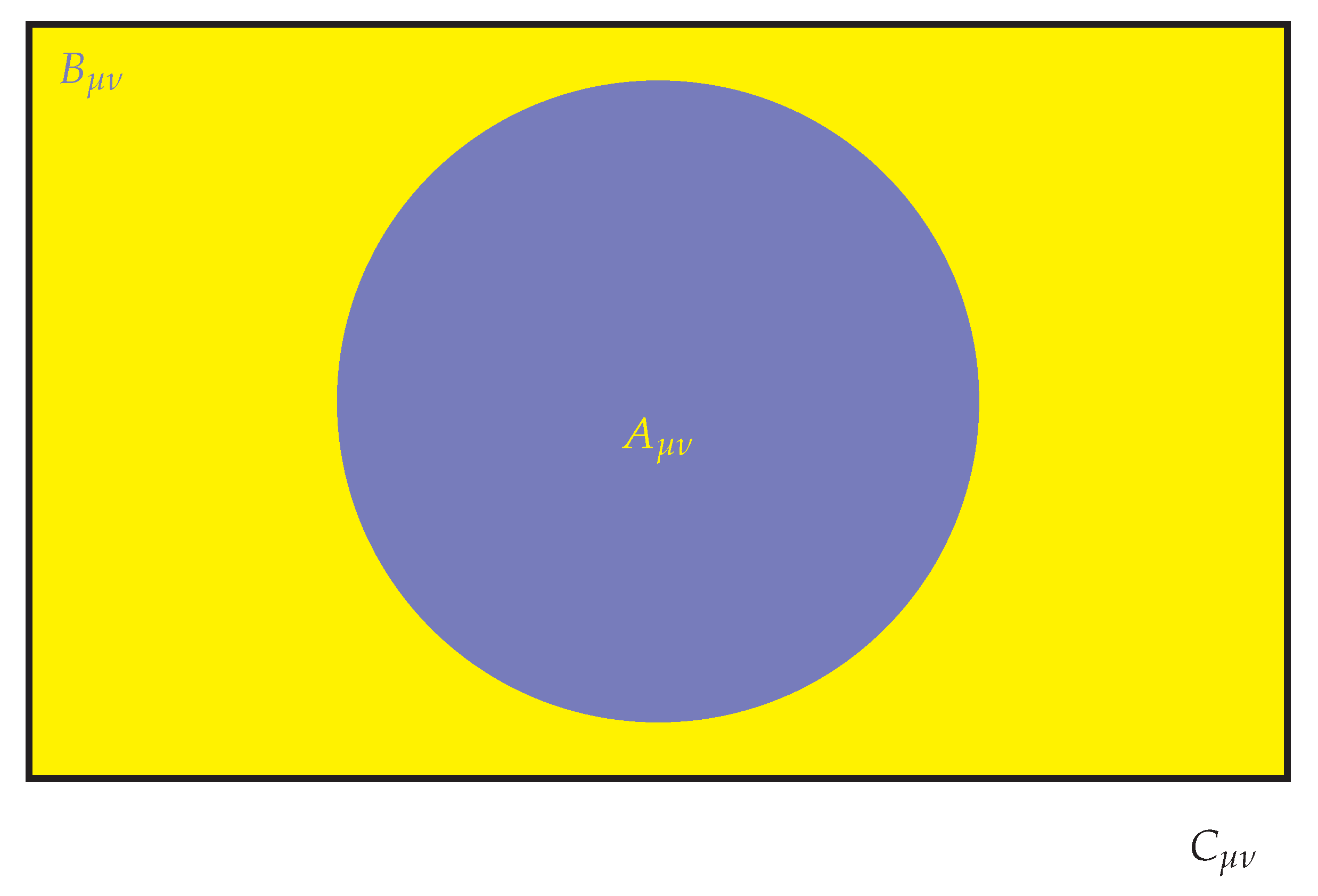

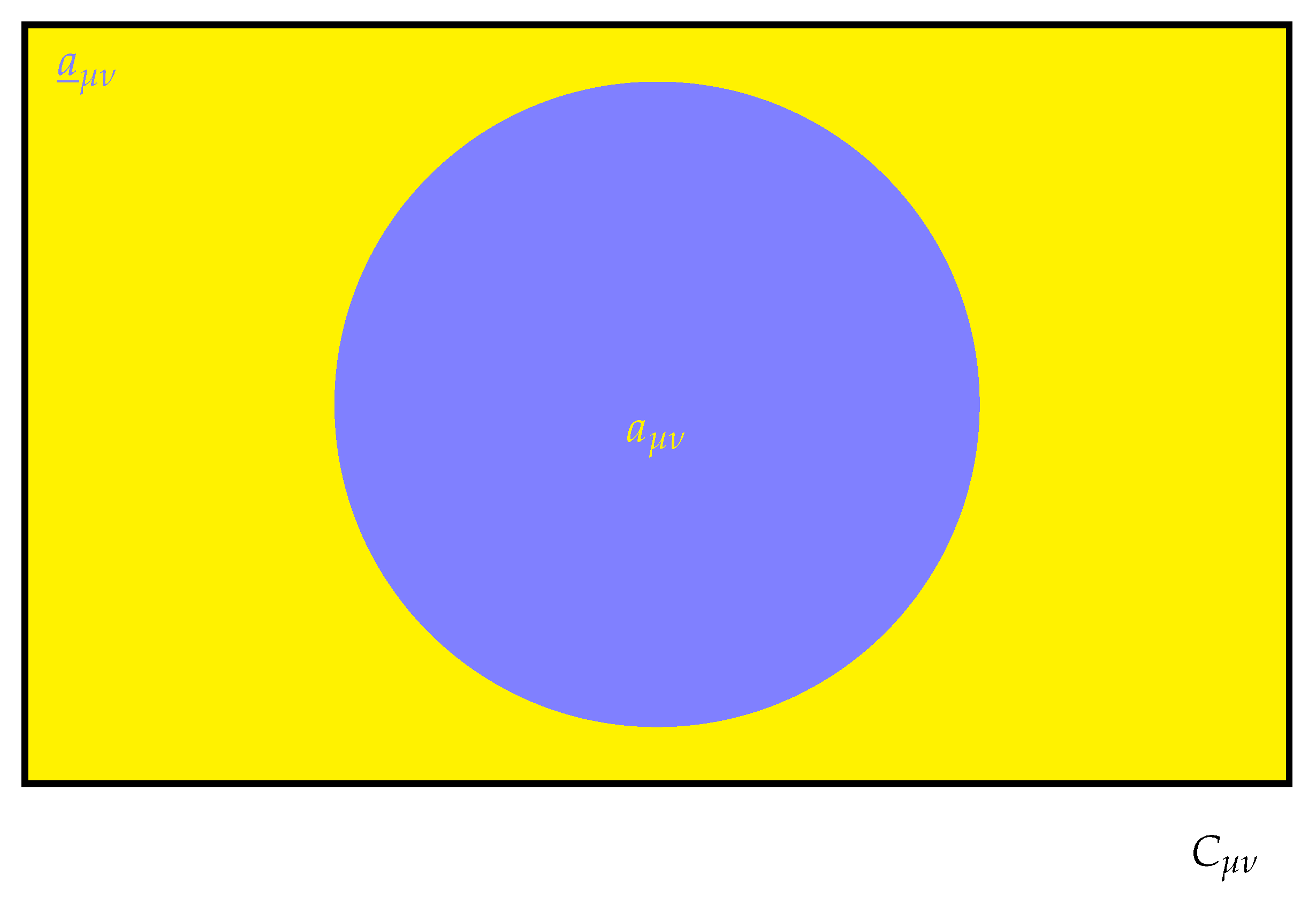

The forthcoming illustration aims to elucidate the intricate relationships between these two tensors with greater clarity.

The sum of two second rank contra-variant tensors has the properties of associativity and commutativity and is defined as

The sum of two second rank mixed tensors has the properties of associativity and commutativity and is defined as

Definition 8

(Anti Tensor I).

Let a

denote a co-variant (lower index) second-rank tensor. Let b

, c

et cetera denote other co-variant second-rank tensors. Let C

denote the sum of these co-variant second-rank tensors. Let the relationship a

+ b

+ c

+ ... ≡ C

be given. A co-variant second-rank anti tensor [

24] of a tensor a

denoted in general as

a is defined

The following illustration is intended to further clarify the relationships between a tensor and its own anti-tensor.

Definition 9

(Anti tensor II).

Let a

denote a contra-variant (upper index) second-rank tensor. Let b

, c

et cetera denote other contra-variant (upper index) second-rank tensors. Let C

denote the sum of these contra-variant (upper index) second-rank tensors. Let the relationship a

+ b

+ c

+ ... ≡ C

be given. A co-variant second-rank anti tensor of a tensor a

denoted in general as

a is defined

Definition 10

(Anti tensor III).

Let a

denote a mixed second-rank tensor. Let b

, c

et cetera denote other mixed second-rank tensors. Let C

denote the sum of these mixed second-rank tensors. Let the relationship a

+ b

+ c

+ ... ≡ C

be given. A mixed second-rank anti tensor of a tensor a

denoted in general as

a is defined

Definition 11

(Tensor subtraction).

The subtraction of two second rank co-variant tensors is defined as

The subtraction of two second rank contra-variant tensors is defined as

The subtraction of two second rank mixed tensors is defined as

Definition 12

(Symmetric and anti symmetric tensors).

Symmetric tensors of rank 2 may represent many physical properties objective reality. A co-variant second-rank tensor a

is symmetric if

However, there are circumstances, where a tensor is anti-symmetric. A co-variant second-rank tensor a

is anti-symmetric if

Thus far, there are circumstances were an anti-tensor is identical with an anti-symmetrical tensor.

Under conditions where C

= 0, an anti-tensor is identical with an anti-symmetrical tensor or it is

However, an anti-tensor is not identical with an anti-symmetrical tensor as such.

Definition 13

(Kronecker delta).

General relativity is a theory of the geometrical properties of space-time to, while the metric tensor g

itself is of fundamental importance for general relativity. The metric tensor g

is something like the generalization of the Pythagorean theorem. Thus far, it does not appear to be necessary to restrict the validity of the Pythagorean theorem only to certain situations. The question is justified why the Riemannian geometry should be oppressed by the quadratic restriction. In this context,

Finsler geometry, named after Paul Finsler (1894 - 1970) who studied it in his doctoral thesis [

25] in 1918, appears to be a kind of metric generalization of Riemannian geometry without the quadratic restriction and justifies the attempt to systematize and to extend the possibilities of general relativity.

The Kronecker delta [

26] is a so called invariant tensor and has been invented by Leopold Kronecker (1823-1891) in 1868 [

27]. Meanwhile, Kronecker delta appears in many areas of physics, mathematics, and engineering and is defined as

In other words, the Kronecker delta,

, is defined as:

In matrix form, the Kronecker delta is represented as the identity matrix. For an

identity matrix

, where

, the matrix is:

For example, the

identity matrix (Kronecker delta in matrix form) is:

The Kronecker delta

itself is not a tensor; it is a function that takes two indices and equals 1 if the indices are equal and 0 otherwise. In terms of tensor operations, the Kronecker delta

behaves like a covariant tensor with all indices due to its representation as an identity matrix. It is commonly used in tensor algebra to raise and lower indices in tensor equations but is not a tensor itself.

Definition 14

(The metric tensor g and the inverse metric tensor g).

The distance between any two points in a given space can be described geometrically by a generalized Pythagorean theorem, the metric tensor g

. Sharing Einstein’s point of view, it is in general

where D might denote the number of space-time dimensions. The quantity

is an invariant. In other words, an index which is repeated inside an expression means summation over the repeated index (Einstein summation convention). Vectors and scalars are invariant under coordinate transformations. In point of fact, Einstein field equations [

3,

4,

5,

28,

29,

28,

29] were initially formulated by Einstein himself in the context of a four-dimensional theory even though Einstein field equations need not to break down under conditions of D space-time dimensions [

30]. Nonetheless, based on Einstein’s statement [

4, p. 796], one gets [

17, p. 91]

or

where g

is the matrix inverse of the metric tensor g

. The inverse metric tensor or the metric tensor, which is always symmetric, allow tensors to be transformed into each other and are used to lower and raise indices.

Axioms

Axioms are foundational assumptions upon which human knowledge can be logically developed, enabling coherent reasoning and a systematic understanding of relationships. Before proceeding, we state three fundamental logical axioms:

1. Law of Identity (

Lex identitatis): Something is identical to itself or:

2. Law of Contradiction (

Lex contradictionis): An equation

cannot be simultaneously true and false:

3. Law of Negation (

Lex negationis): Something is the negation of its own other or

Intrinsic Tensorial Relations

Theorem: The Stress-Energy Tensor of Matter

The stress-energy-momentum tensor, commonly referred to as the stress-energy tensor or energy-momentum tensor, describes the density and flux of energy and momentum in spacetime. It encodes the distribution of matter and radiation and serves as the source of spacetime curvature in the theory of general relativity. In this framework, the stress-energy tensor is symmetric and appears explicitly in the Einstein field equations.

The fundamental nature of the stress-energy tensor can be understood following Einstein’s viewpoint, which asserts that matter consists not only of ordinary matter but also of the electromagnetic field. As Einstein emphasizes:

“... a tensor,

, of the second rank ... includes in itself the energy density of the electromagnetic field and of ponderable matter; we shall denote this in the following as the ’energy tensor of matter’.” [

17, p. 87/88]

Thus, the stress-energy tensor of matter, , can be decomposed into two distinct components, each reflecting different aspects of the system’s energy-momentum content. This idea is further supported by Vranceanu:

“On peut aussi supposer que le tenseur d’énergie

soit la somme de deux tenseurs dont un dû au champ électromagnétique...”[

20]

More precisely, Einstein distinguishes between the gravitational field and matter in a broader sense:

“Wir unterscheiden im folgenden zwischen ‘Gravitationsfeld’ und ‘Materie’, in dem Sinne, daß alles außer dem Gravitationsfeld als ‘

Materie’ bezeichnet wird, also nicht nur die

‘Materie’ im üblichen Sinne, sondern auch das

elektromagnetische Feld...”[

4, pp. 802/803]

Theorem 1.

Following these insights, the stress-energy tensor of matter can be formally split as:

Proof.

denotes the stress-energy tensor of ordinary matter,

-

represents the stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field, where:

- -

is the electromagnetic field strength tensor,

- -

is the spacetime metric tensor,

- -

is the vacuum permeability (in SI units).

□

The decomposition of the matter stress-energy tensor into contributions from the stress–energy tensor of the electromagnetic field and the stress–energy tensor of ordinary matter is both logically consistent and mathematically well–founded within the framework of general relativity theory. Nevertheless, a critic might argue that such a decomposition of the matter stress-energy tensor into contributions from the electromagnetic field and ordinary matter is overly restrictive, potentially neglecting the broader range of field content revealed by modern theoretical physics. In this context, it is important to emphasize that, in Einstein’s view, all contributions to the stress–energy tensor but those due to the electromagnetic field are regarded as ordinary matter – regardless of their actual physical origin, which may include dark matter or other yet unknown forms of energy/matter et cetera. Einstein articulates this perspective succinctly:

“Considered phenomenologically, this energy tensor is composed of that of the electromagnetic field and of matter in the narrower sense.” [

17, p. 93]

This formulation suggests that the total stress–energy tensor

can be understood as comprising two principal components: one due to the electromagnetic field, and the other due to ponderable (or ordinary) matter. Such a decomposition implicitly assumes that all classical [

18,

19] field-theoretic physical phenomena can be traced back to these two categories of energy-momentum distributions. However, Einstein himself acknowledged the limitations of this formulation, particularly concerning the electromagnetic contribution. He noted that the precise geometric structure of the stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field remains unresolved:

“It is only the circumstance that we have not sufficient knowledge of the electromagnetic field of concentrated charges that compels us, provisionally, to leave undetermined in presenting the theory, the true form of this tensor.” [

17, p. 91]

Importantly, the true geometric structure of the stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field remains undetermined. In summary, the stress-energy tensor serves as a comprehensive mathematical object encapsulating all forms of energy and momentum, unifying the contributions of ordinary matter and electromagnetic fields within the framework of general relativity.

Theorem: The Tensor Relation

Spacetime geometry is both influenced by and influences the material content of objective reality, thereby blurring the line between background and substance. Consequently, the Ricci tensor need not be fully determined by matter and energy alone but may also depend on the spacetime structure encoded by the scalar curvature R and the cosmological constant . The presence of hints at a fundamental property of the vacuum itself, suggesting that even empty space might possess an intrinsic structure or exhibit some form of inherent characteristics

Theorem 2.

Ultimately, matter and geometry are inseparably intertwined, reflecting the deeply relational nature of reality given as:

Proof. As found before (cf. Equation (

6)), it is

and (cf. Equation (

29))

□

Theorem: The Tensor Relation

Various critical and non-trivial interplays between the geometric properties of spacetime and the matter-energy content itself are possible.

Proof. Starting from Equation (

32), we can write:

From this, we obtain the following relationship:

□

At this stage of the investigation, the exact physical meaning of the tensor relationship in Equation (

35) remains uncertain, as we lack a complete understanding of the precise nature of the tensors involved. While the terms

,

, and

are mathematically defined, their deeper physical implications are still to be fully explored. Nevertheless, this relationship holds significance in the ongoing investigation.

Theorem: The Tensor Relation

In the context of general relativity, fundamental aspects of the energy, matter, and curvature properties of spacetime are encoded in the tensors

and

. It is theoretically conceivable that both the part of the spacetime curvature (described by

) and the matter-energy content (described by

) share a common underlying tensorial structure, denoted by

. Under these circumstances, each of these tensors can be decomposed into the fundamental common tensor

and an additional tensor term, yielding the following relations:

Thus, we can rearrange this expression as

highlighting the dependence of

on the Einstein tensor and the cosmological constant. Simultaneously, for the curvature term we assume:

and equivalently,

where

represents the additional tensor specific to the geometric part.

Theorem 4.

The Einstein tensor is determined as

where is one of the four basic tensors of nature.

Proof. Since

is defined consistently across the decompositions, it follows that

Substituting Equation (

37), we have

Furthermore, substituting Equation (

39) for

, we obtain

From the known relation (cf. Equation (

35)),

Equation (

43) simplifies to

Canceling the cosmological constant term

from both sides yields

Thus, the Einstein tensor is expressed as the sum of the tensors

and

, completing the proof. □

The proof is logically rigorous within its established context and convincingly demonstrates the decomposition of the Einstein tensor

as the sum of two tensors,

and

. The key assumption underlying the proof is the existence of an unknown yet common tensor

. This assumption is clearly stated as part of the tensor decomposition process. The logical coherence of this assumption is supported by the fact that both tensors share at least the tensor

(cf. Equation (

37) and Equation (

39)) and have something in common. The concrete structure of the tensors

and

will be further elaborated in subsequent sections of the publication, making the proof a solid foundation for further exploration.

Theorem: The Tensor Relation

The tensor , representing a fundamental part of the spacetime curvature, does not appear to be a monolithic entity, but can itself be decomposed into two distinct fundamental fields of nature, and . Although the precise physical interpretation of and remains undetermined at this stage of investigation, the mere possibility of such a decomposition points toward a richer and more intricate structure underlying objective reality. In this sense, spacetime curvature may be regarded as an emergent phenomenon arising from the interplay of multiple, yet-to-be-identified, fundamental constituents of nature.

Proof. As established earlier (see Equation (

6)), we have the relation

Moreover, from Equation (

46), it follows that

Using these results, we can rearrange Equation (

48) to isolate

as

Substituting the expression for

from the Einstein tensor (see Equation (

46)), we obtain

which simplifies directly to

This completes the proof. □

Theorem: The Tensor Relation

Proof. From the known relation (cf. Equation (

52)), it is

From the relation (cf. Equation (

35)), we obtain

□

From the known relation (cf. Equation (

55)), it is

The following table provides an overview of the currently established internal connections between the four fundamental fields of nature.

Table 1.

The four basic fields of nature.

Table 1.

The four basic fields of nature.

| |

|

Curvature |

|

| |

|

YES |

NO |

|

| Momentum |

YES |

a

|

b

|

|

| |

NO |

c

|

d

|

|

| |

|

G

|

|

R

|

Extended Tensorial Relationships

Theorem: The Tensor Relation

Theorem 7.

According to our understanding, the stress-energy tensor of matter and the Einstein tensor share a common tensor. The structure of this tensor is currently unknown to us, and therefore we refer to it as . In general, it is

From this definition, we can express the combination as:

The tensor is a joint tensor that encapsulates the interaction between the stress-energy tensor and the Einstein tensor , highlighting the connection between the geometry of spacetime and the distribution of energy and momentum. In this sense, we define

and do obtain

Based on these assumptions, the tensor is given as

while the tensor is one determining part of this tensor.

Proof. We begin this proof with the insight of Equation (

57) and Equation (

59). From this, we obtain:

From this, we can isolate

by rearranging the equation:

Thus, we obtain the following general relation for

:

□

The stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field, , can be expressed as the sum of two terms: the unknown tensor and the term . In this context, plays a crucial role in determining the overall stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field.

Theorem: The Tensor Relation

The stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field, , encodes the distribution and flow of energy and momentum within the electromagnetic field, illustrating how the field interacts with spacetime geometry. The relationship between this tensor and the curvature of spacetime is crucial for describing the field’s dynamics and its interactions with matter and gravity.

Theorem 8.

The tensor is one determining part of the stress–energy tensor of the electromagnetic field . In general, it is:

Proof. Based on equation (

64) it is

. Adding the tensor

to this equation, we obtain

Based on equation (

30), it is it is

. We obtain

At the end, it is

The stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field is given as:

This confirms the stated result, completing the proof. □

In general, we must acknowledge and accept that

is a tensor which constitutes an essential part of the stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field

(cf. Equation (

69)).

Theorem: The Tensor Relation

Theorem 9.

The stress–energy tensor of ordinary matter, , is given as:

Proof. The Einstein’s field equations (cf. Equation (

28)) are given as:

We obtain

Based on equation (

69) it is

In general, it is

□

From equation (

74), it follows that on one side,

represents a relationship that determines the tensor

. Another relationship that also determines the tensor

is given by

.

However, it is important to note that

is not identical to

. In general, it is

Theorem: The Stress-Energy Tensor of Ordinary Matter

Matter, in Einstein’s framework, comprises not only ordinary matter but also the electromagnetic field. He makes this point explicit in his 1916 paper, stating:

... ‘Materie’ bezeichnet ... nicht nur die ‘Materie’ im üblichen Sinne, sondern auch das elektromagnetische Feld. (see also [

4], pp. 802/803)

In English:

"...‘Matter’ refers not only to ‘matter’ in the ordinary sense, but also to the electromagnetic field."

Theorem 10.

The stress-energy tensor of ordinary matter is determined as:

Proof. The stress-energy tensor of ordinary matter

has been determined as

Adding the stress-energy tensor of electro-magnetic field

to this equation, it is

Based on Equation (

69), it is

. Substituting this relationship into Equation (

78), we obtain

The tensor

loses its significance within Equation (

79) and cancels out. As a result, Equation (

79) simplifies to:

From Equation (

64), we know that the term

represents a contributing part of the stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field

, which can be written as:

Additionally, we know that the term

represents another contributing part of the stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field

, which can be written as: (cf. Equation (

69)):

Considering these facts, it follows with compelling logical necessity that the second determining part of equation (

80) must be identified with the electromagnetic stress-energy tensor. In other words, the fully geometrized representation of the stress-energy tensor associated with the electromagnetic field takes the form:

is the vacuum permeability (also known as the magnetic constant), a physical constant that appears in Maxwell’s equations.

is the

electromagnetic field strength tensor with lowered indices, defined as:

where

is the four-potential of the electromagnetic field.

is the

mixed-index version of the field strength tensor, obtained by raising the second index:

is the

metric tensor of spacetime, used to raise and lower indices. In Minkowski space (special relativity), it is typically:

is the invariant scalar of the electromagnetic field, representing the contraction of the field strength tensor with itself.

Provided that the Einstein field equations are internally logically consistent and physically well–posed, it follows – as a rigorous consequence of the preceding theoretical framework and assumptions – that the stress–energy tensor describing ordinary matter, denoted by

, is determined by the following relation:

□

Theorem: The Tensor of Pure Non–Locality

Theorem 11.

The tensor of pure non–locality [see 8,9] is given as:

Proof. Based on Equation (

81) it is:

Adding the tensors

to this equation, we obtain

Based on Equation (

30) it is:

. Substituting this relationship into Equation (

85), we obtain

The tensor of pure non–locality is given as

□

The relation taken as experimentally validated represents a profound synthesis in the geometrization of physics. This relationship suggests that the totality of physical content can be fully encoded by the scalar curvature R multiplied by the metric tensor . Such a formulation implies that all energetic and dynamical phenomena in spacetime reduce to geometric invariants, blurring the boundary between matter and geometry.

This would mark a conceptual shift parallel to that of general relativity, but deeper in scope: geometry no longer just responds to matter – it is matter, in aggregate form. The equation thus provides a potential cornerstone for unification efforts, as it encapsulates multiple physical phenomena under a single geometric umbrella. Moreover, it could open avenues for new theoretical models in cosmology and quantum gravity, particularly where the interplay between curvature and field content must be understood at fundamental scales.

While general relativity is fundamentally a local theory – governed by differential equations that relate spacetime curvature to energy–momentum at each point–it does not inherently preclude the incorporation of non–local effects. In fact, several approaches to quantum gravity and semiclassical gravity suggest that non–local relationships can emerge naturally in regimes where quantum fluctuations of the spacetime fabric become significant. Such non–localities may manifest through effective actions, propagators, or entanglement structures that span finite spacetime regions, without violating the local covariance of Einstein’s equations. Therefore, general relativity and non–locality need not be viewed as mutually exclusive but rather as components of a broader framework yet to be fully understood. This opens promising pathways toward reconciling gravity with quantum theory without abandoning geometric intuition.

Theorem: The Tensor

Theorem 12.

The tensor is given as:

Proof. We have determined (see Equation (

64)) the relationship:

Based on Equation (

81), it is

Equation (

89) becomes:

At the end we obtain:

□

Theorem: The Tensor

Theorem 13.

The basic field of nature is given by the relation:

Proof. We begin with the general identity (cf. Equation (

30)):

As previously established (see Equation (

91)), the tensor

is given by:

Substituting this result into Equation (

93), we obtain:

By subtracting

from both sides, we isolate the fundamental tensor:

□

Theorem: The Tensor Relation

Theorem 14. The unification of gravitation and electromagnetism [7,31] in a more geometrico fashion–

“... joining the gravitational and the electromagnetic field into one single hyperfield ...” [16, p. 5]

that is, derived purely from geometric principles without the inclusion of additional, explicit matter source terms—is expressed by the following relation:

Proof. It has been previously established (cf. Equation (

64)) that the tensors satisfy the relation:

Adding the tensor

to both sides of Equation (

97) yields:

As previously derived (cf. Equation (

91)), the tensor

takes the form:

Substituting this into Equation (

98), we obtain:

Combining the two terms involving

R, we arrive at the final expression for the unification of the gravitational and electromagnetic contributions:

□

The current findings are illustrated in the following table (

Table 2).

The Quantization of Spacetime

Unifying general relativity and quantum theory to describe spacetime at the Planck scale has been a central focus of study for nearly a century. The concept of quantizing spacetime has evolved through significant contributions from physicists such as John Wheeler, Bryce DeWitt [

32], and Richard Feynman [

33], who laid the groundwork for quantum gravity. However, the theoretical development of quantum gravity presents profound methodological and conceptual challenges, as the quantization of the gravitational field may imply the quantization of spacetime geometry itself. In particular, reconciling quantum theory with gravity arises from the apparent incompatibility between general relativity, which describes gravitation, and quantum field theory, which governs the other fundamental forces of nature. General relativity, rooted in Einstein’s equations, relates spacetime curvature to mass and energy, while quantum field theory operates within a fundamentally different framework. Given these challenges, our aim is to first establish the foundational principles of the quantization of gravity and spacetime, and subsequently propose a solution to this longstanding problem.

Quantum Gravity in General

Theorem. The Stress Energy Tensor of Matter

and Laue’s Scalar T

Laue’s scalar

T provides a coordinate-invariant measure of the energy–momentum distribution [

36,

37] within a relativistic system.

Theorem 16. Laue’s Scalar T is a determining part of the Einstein’s field equations.

Proof. The Laue’s Scalar

T is given as:

□

The Geometrical Structure of the Stress-Energy Tensor of Matter

General relativity’s approach to gravitation is based on a more or less complicated geometry of space and time while doing away with forces. In other words, gravity and space-time geometry are related. In the Einstein field equations, it is the stress-energy tensor of matter

, introduced by Max von Laue (1879-1960) in the year 1911 [p. 528

36] as ‘Welttensor’, which is the source of gravitation. Unfortunately, the stress-energy tensor of matter

is still “... a field devoid of any geometrical significance” [

38, p. 7]. In general relativity, a relation which ties the matter and energy content (described by the stress-energy tensor) to the curvature of spacetime is crucial. A possible way out of this persistent difficulty might be a detour via a scalar.

Theorem

Theorem 17.

The scalar E associated with the stress-energy tensor of matter is given by:

Proof. We begin with the fundamental equation:

Our goal is to geometrize this tensor fully. To do this, we express it in terms of an unknown scalar

E and the metric tensor

. This results in the following form:

Next, we take the trace of both sides. The trace operation has several important properties, but a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this proof. Taking the trace of Equation (

112), we obtain:

We can now use the identity

(cf. Equation (

21)), where

D is the spacetime dimension. Thus, Equation (

113) becomes:

By solving for

E, we find:

Finally, multiplying both sides of Equation (

115) by the metric tensor

, we obtain:

Thus, we have completed the proof. □

The Specifics of Quantum Gravity

In general, the Einstein field equations (EFE) as a set of ten interrelated differential equations in the general theory of relativity describe how matter and energy interact with the curvature of spacetime, which we perceive as gravity. These equations are expressed in a generally covariant form, meaning they hold true regardless of the coordinate system used. Thus far, is it possible at all to find something like a scalar foundation of the Einstein’s field equations

Quantisation of Gravitation

The mathematical reduction of the Einstein’s field equations to something like scalars would theoretically mean transforming a set of complex tensor equations into a single scalar equation. Such a simplification could make calculations involving gravitational fields significantly easier, especially in complex scenarios involving multiple interacting masses but can be associated with problems too.

Theorem 18.

The quantisation of spacetime and the gravitational field is given as:

Proof. Again, we start with the fundamental equation that

According to Einstein’s general relativity, we have to consider the equivalence of

Rearranging equation (

119), we get

Taking the trace of the Einstein’s field equations, it is

It is

. The Einstein’s field equations can be reduced to scalars given as

Equation (

122) is highlighting the interplay between mass-energy content and the geometry of space-time, a fundamental principle of general relativity. Dividing equation (

122) by the spacetime dimension

, we obtain the scalar (cf. Equation (

108), cf. Equation (

109), cf. Equation (

116)) foundation of the Einstein’s field equations as

We extend the equation by adding

and obtain:

Alternatively, in a simpler form:

Archimedes’ constant

has been determined as

(cf. Equation (

3)). Substituting this relationship into previous equation (cf. Equation (

125)), it is

Equation (

126) simplifies as

The wave function is generally represented as

. So we perform the multiplication across the entire Equation (

127) by

. It is

In general it is

(cf. Equation (

3)). Substituting this relationship into previous equation (cf. Equation (

128)), it is

In general, the quantisation of spacetime and the gravitational field is given as:

□

Theorem. The Generally Covariant Planck–Einstein Relation

The Einstein–Planck relation establishes a relation between energy E in terms of its frequency f, given by , where h is Planck’s constant and is angular frequency.

Definition 15

(The stress-energy tensor of frequency ).

In this context, we define the stress–energy tensor of frequency (cf. Equation (

129)) as:

Furthermore, we define

Definition 16

(The stress-energy tensor ).

Furthermore, we define the stress–energy

tensor (cf. Equation (

129)) as:

Theorem 19.

The generally covariant form of the Planck–Einstein relation is given by

Proof. Based on Equation (

130), it is

Multiplying Equation (

134) by the metric tensor

, it is

Based on our definition (cf. Equation (

131), cf. Equation (

132)), the generally covariant Planck–Einstein relations is given as

□

4. Discussion

The complete geometrization of the Einstein field equations presented in this work–where both the electromagnetic and material stress-energy tensors are interpreted as intrinsic manifestations of spacetime geometry–constitutes a paradigmatic shift in the foundations of theoretical physics. Within this framework, all physical dynamics, including those of electromagnetic and mass-bearing fields, arise not from independently introduced source terms but as direct consequences of geometric invariants such as the Ricci or Riemann tensor. Accordingly, the need to externally impose stress-energy tensors to describe matter and field distributions becomes obsolete.

This conceptual framework realises a long-standing vision once pursued by Einstein, Weyl, Kaluza, and other pioneers of unified field theory: the reduction of all fundamental interactions of nature to pure geometry. In this paradigm, mass ceases to be an ontologically independent entity and instead emerges as a manifestation of specific geometric configurations. Analogously, electric charge is determined by a topological or locally geometric property of spacetime. The separation between gravity and the other fundamental interactions becomes a question of limiting regimes, rather than a reflection of fundamental distinction. Building upon this geometric foundation, a broad spectrum of new theoretical, experimental, and technological perspectives becomes accessible.

Theory. In particular, complex physical systems can now be modelled purely through the resolution of extended geometric field equations, for instance via numerical methods on higher-dimensional manifolds. The conventional division between gravitation and the remaining fundamental interactions can thereby be transcended, opening the door to novel approaches in quantum field theory. Of special significance is the natural integration with quantum theory. A fully geometrised unified field theory entails—without recourse to additional quantisation procedures—an intrinsic quantisation of both gravitation and the other fundamental fields. Within such a framework, the quantisation of matter becomes inseparable from the quantisation of spacetime. Rather than imposing quantum fields upon a fixed background, quantum states would be encoded directly in the dynamical geometry. This may resolve long-standing issues such as non-renormalisability and background dependence in quantum gravity, and offers fundamentally new avenues for reconciling general relativity with quantum mechanics.

The composite tensor equation

implies that electromagnetic field contributions are not mere sources of curvature but are geometrically equivalent to terms involving the Ricci scalar and cosmological constant. This suggests a deeper dynamical unification of gauge fields and gravity.

In a more speculative direction, the identification of the electromagnetic stress-energy tensor with curvature terms may imply that electromagnetism itself arises from quantum fluctuations of geometry, in a manner akin to the Sakharov-style induced gravity scenario [

14,

15]. The proposed framework may likewise offer a novel perspective on the cosmological constant problem, geometrically linking vacuum energy to curvature via field strength invariants.

Such a relationship motivates experimental searches for curvature-induced corrections to quantum electrodynamics (QED), such as shifts in g-factors, Lamb shifts, or vacuum birefringence, particularly in regimes of strong gravity. High-precision experiments—such as Penning traps, atomic interferometers, or cavity QED setups—could constrain the properties of the tensor . On cosmological scales, deviations from CDM might emerge through curvature–electromagnetism couplings. Observable consequences could include anomalous lensing, polarisation rotation of distant sources, or imprints on the cosmic microwave background.

The identification

suggests that matter is not fundamental but instead emerges from curvature. This dissolves the classical dualism between geometry and substance, implying that energy and momentum may arise from spacetime structure alone. Consequently, the quantum state of matter is inseparable from the quantum state of the spacetime geometry.

Astrophysical observations near compact objects and cosmological measurements—such as CMB power spectra, gravitational lensing, or pulsar timing arrays—may reveal deviations consistent with this hypothesis. Observable effects could include redshift anomalies, birefringence, or unexpected patterns of structure formation.

Finally, the geometric formulation of unified field theory opens new horizons in cosmology. Dark matter and dark energy may be reinterpreted as emergent phenomena arising from the complexity of spacetime geometry, obviating the need to posit exotic new forms of matter. In particular, it becomes plausible that the observed cosmological acceleration originates from global topological or geometric properties of spacetime itself.

Experiments. These theoretical developments suggest a rich spectrum of experimental testability. Subtle deviations from the standard model of gravitation could be probed through high-precision satellite geodesy missions such as GRACE or LARES. Furthermore, static electromagnetic configurations in vacuum may yield novel signatures if they indeed arise from the underlying spacetime geometry. Particularly sensitive tests could be conducted in strong gravitational regimes—such as near neutron stars or black holes—where geometric coupling between gravity and electromagnetism may manifest in observable polarisation patterns or radiation anomalies. Complementary to astrophysical tests, laboratory experiments employing superconducting or ultra-cold quantum systems may enable direct exploration of geodesic effects on charged particles or vacuum fluctuations in curved geometries. A fully geometrised model also provides a consistent theoretical basis for predicting novel topological spacetime structures with quantised features—such as discrete defect configurations potentially identifiable with elementary particles.

Technology. A fully geometric unified field theory not only offers a profound conceptual unification of physical law but also lays the groundwork for a new generation of physical theory, experimental technique, and technological application. Analogous to electromagnetic induction [

39]—where a time-varying magnetic field generates an electric field—we propose a gravitational counterpart: gravitational induction, whereby variations in spacetime curvature give rise to secondary gravitational effects or tidal accelerations, akin to gravitational waves [

40]. This idea is consistent with general relativity in dynamic regimes, where gravitational waves—propagating fluctuations in curvature—carry energy and momentum through spacetime. Such waves suggest that energy could, in principle, be extracted via coherent geometric dynamics.

Building on this, the theoretical realisation of a spacetime reactor appears conceivable: a device engineered to harness energy from controlled curvature oscillations, potentially induced by rotating or oscillating massive structures configured to generate localised, non-linear gravitational interactions. By exploiting resonance effects and engineered asymmetries, such a reactor could stimulate induced curvature fields analogous to gravitational waveforms, enabling the extraction of energy from the vacuum structure or spacetime medium itself. Operating at the intersection of general relativity and quantum field theory, the spacetime reactor would not violate energy conservation, but instead redistribute energy through induced geometric processes. While highly speculative, this concept introduces a novel technological paradigm for gravitational energy conversion, potentially enabling advanced propulsion, power generation, or gravitational signal manipulation.

Under conditions in which all properties of ordinary matter are entirely encoded in the geometry of spacetime itself, the energy–momentum tensor of matter,

, ceases to be an independent physical quantity and instead becomes a manifestation of curvature—specifically, the Ricci tensor and Ricci scalar. In other words, matter does not exist as a separate substance superimposed upon spacetime, but emerges intrinsically from its geometric structure. Under such conditions, the traditional distinction between matter manipulation and geometric manipulation dissolves: geometric manipulation is matter manipulation, and vice versa. Within this framework, the instantaneous relocation or reconstruction of matter could, in principle, be achieved through a localised reconfiguration of the geometric field structure itself [

41,

42]. Ultimately, rather than transporting particles through space, it may be theoretically possible to encode the geometric curvature corresponding to a specific matter configuration and reproduce it elsewhere via controlled spacetime deformations.

Building upon the complete geometrization of the Einstein field equations, where all four fundamental fields of nature are unified within the fabric of spacetime geometry, a radically novel approach to quantum computing [

43,

44] emerges. In this paradigm, quantum information is no longer encoded in discrete quantum states within a fixed, static geometry, but rather within the dynamic curvature of spacetime itself. Localized deformations of the geometric field structure are used to represent quantum bits (qubits), with these qubits existing as quantum superpositions of curvature configurations. By leveraging spacetime’s intrinsic entanglement properties, quantum states can be entangled with far greater efficiency than conventional systems. Computational operations, such as quantum gates, are performed by manipulating geometry at localized points in spacetime, enabling operations that inherently exploit spacetime’s non-linear, non-local properties. This approach could provide unprecedented scalability, computational speed, and energy efficiency, surpassing the limitations of classical quantum computers while addressing fundamental challenges like decoherence and error correction through the quantum coherence of spacetime itself.

While such possibilities lies far beyond current technological capabilities and remains firmly within the realm of theoretical speculation, preliminary experimental efforts could explore energy exchange via dynamically modulated Casimir geometries or engineered spacetime metamaterials. Should the encoding of matter in geometry be fully formalised, the blueprint of a human—or any complex structure—might one day be reducible to a geometric map, permitting instantaneous geometric replication at distant locations. While speculative, these theoretical possibilities offer a radical reconceptualisation of energy, identity, and transportation in a universe governed by geometry alone.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we have successfully achieved the complete geometrization of the Einstein field equations, unifying all four fundamental fields of nature within the framework of spacetime geometry. Each of these four basic fields of nature has been precisely identified and described in geometric terms, revealing the deep interconnections between matter and geometry. Moreover, the quantization of spacetime itself has been realized within the context of quantum gravity, providing a foundation for a new, unified description of the fundamentals of objective reality. This breakthrough not only reshapes our understanding of the universe but also opens new avenues for theoretical and experimental exploration, where the traditional boundaries between gravity and other interactions, as well as between classical and quantum realms, are blurred. The implications for future technologies, including quantum computing and novel forms of energy manipulation, are profound and offer a glimpse into a new era of scientific and technological development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ilija Barukčić; methodology, Ilija Barukčić; software, Ilija Barukčić; validation, Ilija Barukčić; formal analysis, Ilija Barukčić; investigation, Ilija Barukčić; resources, Ilija Barukčić; data curation, Ilija Barukčić; writing—original draft preparation, Ilija Barukčić; writing—review and editing, Ilija Barukčić; visualization, Ilija Barukčić; supervision, Ilija Barukčić; project administration, Ilija Barukčić; funding acquisition, Ilija Barukčić;Ilija Barukčić has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

No external support or generative AI tools were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCE |

Before Current Era |

| CMB |

Cosmic Microwave Background |

| DOAJ |

Directory of Open Access Journals |

| EFE |

Einstein field equations |

| GRACE |

Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment |

| LARES |

Laser Relativity Satellite |

| LD |

Linear Dichroism |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| QED |

Quantum Electrodynamics |

| TLA |

Three-Letter Acronym |

|

CDM |

Lambda Cold Dark Matter (standard cosmological model) |

References

- Newton, I. (1687). Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Jussu Societatis Regiae ac Typis Josephi Streater. http://dx.doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-440.

- Einstein, A.; Grossmann, M. Entwurf einer verallgemeinerten Relativitätstheorie und einer Theorie der Gravitation; Verlag von BG Teubner: Leipzig, Germany, 1913. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1915). Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Berlin), 844–847.

- Einstein, A. (1916). Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Annalen der Physik, 354(7), 769–822. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1917). Kosmologische Betrachtungen zur allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Berlin), 142–152.

- Barukčić, I. (2011). The Equivalence of Time and Gravitational Field. Physics Procedia, 22, 56–62. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Barukčić, I. (2016). Unified Field Theory. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 4(8), 1379–1438. Scientific Research Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Barukčić, I. (2020a). Einstein’s field equations and non-locality. International Journal of Mathematics Trends and Technology, 68(6), 146–167. Seventh Sense Research Group Journals. http://dx.doi.org/10.14445/22315373/IJMTT-V66I6P515.

- Barukčić, I. (2020b). Locality and Non Locality. European Journal of Applied Physics (EJ-PHYSICS), 2(5), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Barukčić, I. Unification of Geometry and Probability Theory. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Applied Mathematics and Computer Science (ICAMCS), Istanbul, Turkey, 13–15 June 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2023; pp. 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Planck, M. Über irreversible Strahlungsvorgänge. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1899, 1, 440–480.

- Planck, M. Ueber das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspektrum. Annalen der Physik 1901, 4, 553–563. DOI: 10.1002/andp.19013090310.

- Dirac, P. A. M. Quantum mechanics and a preliminary investigation of the hydrogen atom. Proc. Roy. Soc. A 1926, 110, 561–579.

- Sakharov, A.D. (1967). Vacuum Quantum Fluctuations in Curved Space and the Theory of Gravitation. Soviet Physics Doklady, 12, 1040–1041.

- Sakharov, A.D. (1991). Vacuum Quantum Fluctuations in Curved Space and the Theory of Gravitation. Uspekhi Fizicheskikh Nauk (translated from Soviet Physics Uspekhi), 161(5), 64–66.

- Tonnelat, M.-A.; Février, P.; Lichnerowicz, A. La théorie du champ unifié d’Einstein et quelques-uns de ses développements; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1955.

- Einstein, A. The Meaning of Relativity: Four Lectures Delivered at Princeton University, May, 1921; Princeton University Press: Princeton, USA, 1923.

- Barukčić, I. The Relativistic Wave Equation. Int. J. Appl. Phys. Math. 2013, 3, 387–391. Available online: http://www.ijapm.org/show-41-364-1.html (accessed on [insert access date]).

- Barukčić, I. Wave Particle Duality. Causation 2022, 17, 5–30. Available online: https://zenodo.org/record/7327213 (accessed on [insert access date]).

- Vranceanu, G. Sur une théorie unitaire non holonome des champs physiques. Journal de Physique Radium 1936, 7, 514–526. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. On the Generalized Theory of Gravitation. Scientific American 1950, 182, 13–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0450-2.

- Voigt, W. Die fundamentalen physikalischen Eigenschaften der Krystalle in elementarer Darstellung; Verlag von Veit und Companie: Leipzig, 1898; p. 20. Available online: http://archive.org/details/bub_gb__Ps4AAAAMAAJ.

- Ricci-Curbastro, G.; Levi-Civita, T. Méthodes de calcul différentiel absolu et leurs applications. Mathematische Annalen 1900, 54, 125–201. DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Barukčić, I. N-th Index D-Dimensional Einstein Gravitational Field Equations. Geometry Unchained., 1st ed.; Books on Demand GmbH: Hamburg-Norderstedt, Germany, 2020.

- Finsler, P. Über Kurven und Flächen in allgemeinen Räumen; Ph.D. Thesis, Georg-August Universität: Göttingen, Germany, 1918. Available online: https://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/id/PPN321583582 (accessed on [insert access date]).

- Zehfuss, G. Über eine gewisse Determinante. Z. Math. Phys. 1858, 3, 298–301.

- Kronecker, L. Ueber bilineare Formen. J. Reine Angew. Math. 1868, 68, 273–285.

- Einstein, A.; de Sitter, W. On the Relation between the Expansion and the Mean Density of the Universe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1932, 18, 213–214.

- Einstein, A. Elementary Derivation of the Equivalence of Mass and Energy. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1935, 41, 223–230. Available online: https://projecteuclid.org/download/pdf_1/euclid.bams/1183498131 (accessed on [insert access date]).

- Stephani, H.; Kramer, D.; MacCallum, M.; Hoenselaers, C.; Herlt, E. Exact Solutions of Einstein’s Field Equations, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003.

- Barukčić, I. Time and gravitational field. Causation 2023, 18, 5–145. https://zenodo.org/record/7391845. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J. A.; DeWitt, B. S. Quantum Gravity: A New Synthesis. In Gravitation: An Introduction to Current Research; Witten, L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1967; pp. 478–530.

- Feynman, R. P. The Theory of Gravitation in Quantum Mechanics. In Proceedings of the International School of Physics "Enrico Fermi"; 1963; Course 47, pp. 258–274.

- Kasner, E. Five notes on Einstein’s theory of gravitation. Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 1920, 27, 62–63.

- Besse, A. L. Einstein Manifolds and Topology. In Einstein Manifolds; Besse, A. L., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1987; pp. 154–176.

- Laue, M. v. Zur Dynamik der Relativitätstheorie. Ann. Phys. 1911, 340, 524–542. [CrossRef]

- Giulini, D. Laue’s Theorem Revisited: Energy–Momentum Tensors, Symmetries, and the Habitat of Globally Conserved Quantities. Int. J. Geom. Methods Mod. Phys. 2018, 15 (supp01), 1850182.

- Goenner, H.F.M. On the history of unified field theories. Living Rev. Relativ. 2004, 7, 1–153. Springer.

- Maxwell, J.C. A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 1865, 155, 459–512.

- Einstein, A. Über Gravitationswellen. Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften (Berlin), Sitzungsberichte 1918, 154, 154–167.

- Bennett, C. H.; Brassard, G.; Crepeau, C.; Jozsa, R.; Peres, A.; Wootters, W. K. Teleporting an Unknown Quantum State via Dual Classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Channels. Physical Review Letters 1993, 70, 1895–1899.

- Zeilinger, A.; Weihs, G.; Kwiat, P. G.; Andreas, L.; Wootters, W. K. Experimental Quantum Teleportation. Physical Review Letters 1998, 81, 5039–5043.

- Feynman, R. P. Simulating Physics with Computers. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1982, 21, 467–488. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D. Quantum Theory, the Church-Turing Principle, and the Universal Quantum Computer. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 1985, 400, 97–117.

Table 2.

The four basic fields of nature in detail.

Table 2.

The four basic fields of nature in detail.

| |

|

Curvature |

|

| |

|

YES |

NO |

|

| Momentum |

YES |

|

|

|

| |

NO |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).