Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

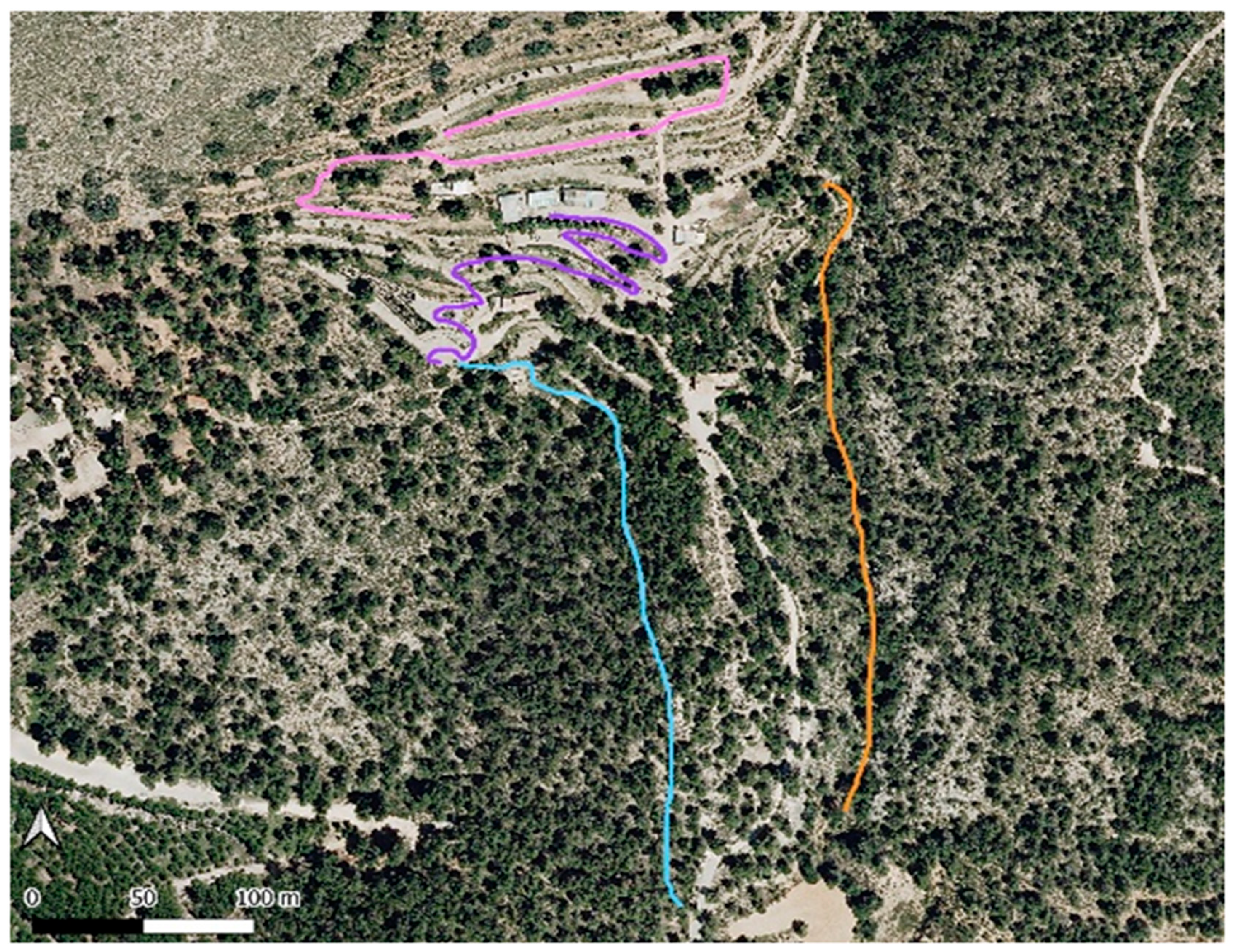

2. Materials and Methods

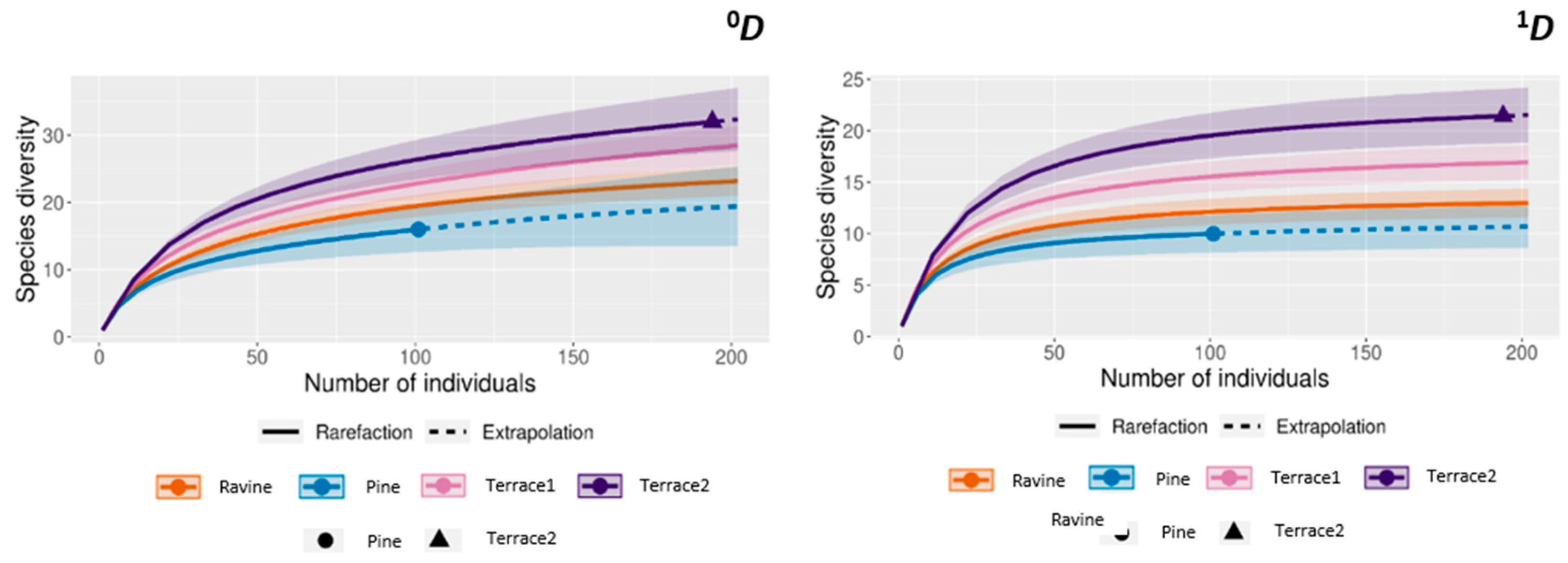

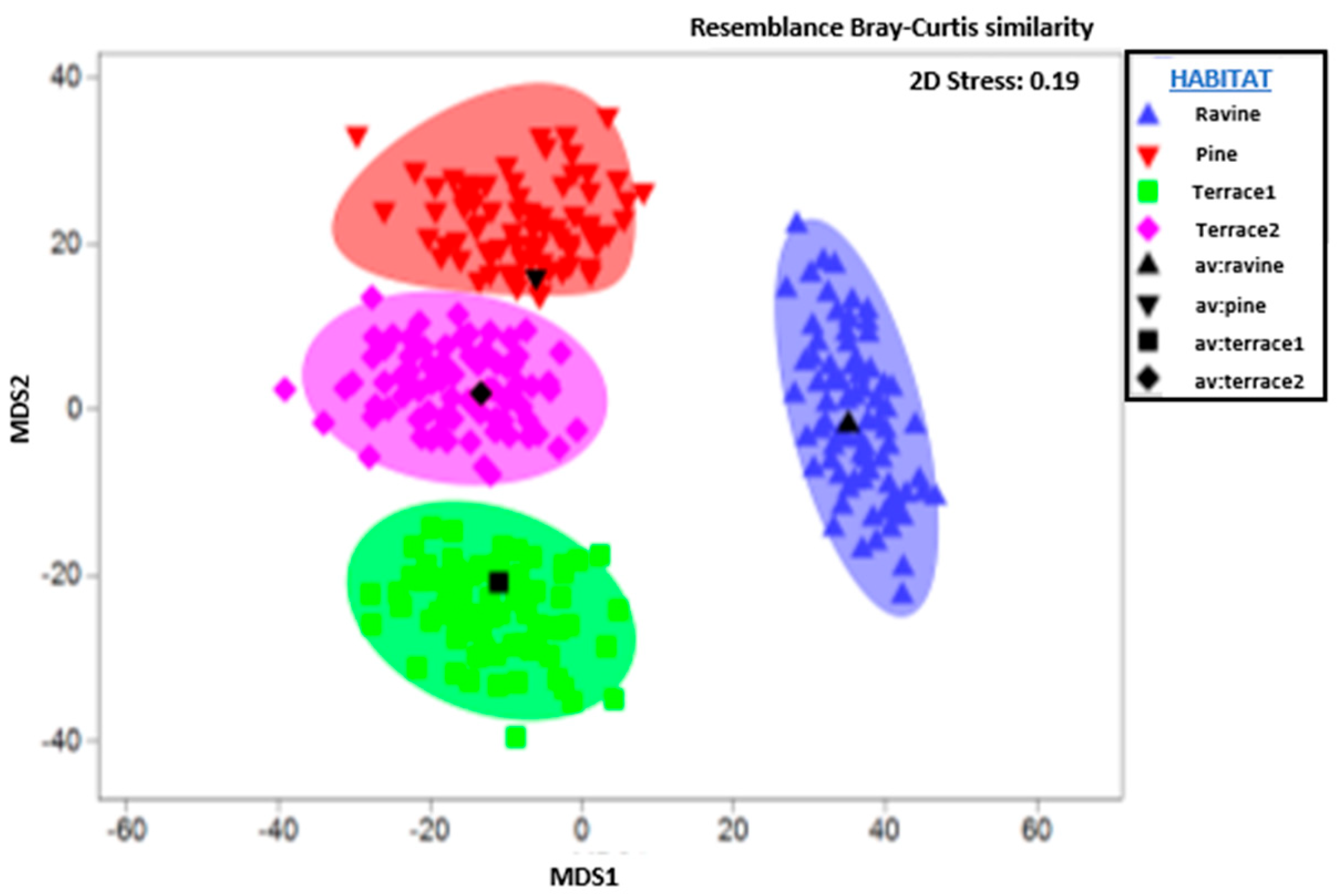

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aragón, P.; Sánchez-Fernández, D.; Hernando, C. Use of satellite images to characterize the spatio-temporal dynamics of primary productivity in hotspots of endemic Iberian butterflies. Ecological Indicators, 2019, 106, 105449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Values and Perceptions of Invertebrates. Conservation Biology 1993, 7(4): 845-855.

- Levente, S.; Ștefănescu R.; Cernea E. The butterflies of Romania/Fluturii de zi din România. Editorial Brasov County History Museum 2008, 305 pp.

- Boggs, C.L.; Watt W.B.; Ehrlich P.R. Butterflies. Ecology and evolution taking flight. Editorial University of Chicago Press, 2003, 739 pp.

- Thomas, J.A.; Clarke, R.T. Extinction rates and butterflies. Science 2004, 325: 80-83. [CrossRef]

- Nieukerken, Ej.; Kaila, L.; Kitching, I.J.; Kristensen, N.P.; Lees, D.C.; et al. Order Lepidoptera Linnaeus, 1758. In Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness, Zhang, Z.-Q. Ed., Zootaxa, 2011, 3148, 212–221. [CrossRef]

- Numa, C.; Van Swaay C.; Wynhoff I.; Wiemers M.; Barrios V.; Allen D.; Sayer C.; López Munguira M.; Balletto E.; Benyamini D.; Beshkov S.; Bonelli S.; Caruana R.; Dapporto L.; Franeta F.; Garcia-Pereira P.; Karaçetin E.; Katbeh-Bader A.; Maes D.; Micevski N.; Miller R.; Monteiro E.,; Moulai R.; Nieto A.; Pamperis L.; Pe’er G.; Power A.; Šašić M.; Thompson K.; Tzirkalli E.; Verovnik R.; Warren M.; Welch H.. The status and distribution of Mediterranean butterflies. IUCN, Malaga, Spain. 2016, 32 pp.

- Ollerton, J.; Tarrant, S.; Winfree, R. How many flowering plants are pollinated by animals? Oikos 2011, 120, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.L. Selecting indicator taxa for the quantitative assessment of biodiversity, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B,Biological Sciences, 1994, 345(1311): 75-79. [CrossRef]

- New, T.; Pyle R.M.; Thomas J.A.; Thomas C.D.; Hammond P.C. Butterfly conservation management. Annual Review of Entomology 1995, 40: 57-83.

- Blondel, J.; Aronson J. Biology and wildlife of the Mediterranean region. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, 327 pp.

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 2000, 403: 853-858. [CrossRef]

- Lucio, J.V.; Gómez Limón J. Percepción de la diversidad paisajística. In La Diversidad Biológica de España, Pineda, F.; De Miguel J.; Casado M. Eds., Prentice Hall, Madrid 2002, 101-110.

- Galante, E. Diversité entomologique et activité agro-sylvo-pastorale. In Conservation de la biodiversité dans les paysages ruraux européens, Lumaret J.P.; Jaulin S.; Soldati F.; Pinault G.; Dupont P. Eds., UPV/CIBIO/PNR de la Narbonnaise en Méditerranée/OPIE-LR, Montpellier 2005, 185 pp.

- Galante, E.; Marcos-García M.A., El Bosque Mediterráneo. Los Invertebrados. In La Red española de Parques Nacionales, García-Canseco V.; Asensio B. Eds., Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Madrid 2004, 272-282.

- Galante, E.; Marcos-García M.A. El bosque mediterráneo ibérico: un mundo manejado y cambiante. In Los insectos saproxílicos del Parque Nacional de Organismo Autónomo de Parques Nacionales, Micó, E.; Galante, E.; Marcos-García M.A., Eds., Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente, Madrid. Cabañeros 2013, 12-32.

- Sundseth, K. Natura 2000 in the Mediterranean Region. Luxembourg, Directorate General for the Environment (European Commission) 2009, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779/77695.

- Van Swaay, C.A.M.; Warren, M.S. Red Data book of European butterflies (Rhopalocera). Nature and Environment, 1999, 99, Council of Europe Publishing,Strasbourg, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234022271.

- García-Barros, E.; Romo H.; Monteys V.; Munguira M.L.; Baixeras J.; Moreno A.V; Yela García J.L. Clase Insecta. Orden Lepidoptera. Revista IDE@-SEA 2015 65: 1-21.

- Asociación Zerynthia, Mariposas de España. Listado de especies de las mariposas de España. 2023, https://www.asociacion-zerynthia.org/especies.

- Galante, E. Los Insectos, esos pequeños seres imprescindibles para nuestra vida. In Bases técnicas para la conservación de los lepidópteros amenazados en España, Jubete, F. (Coord.); Barea-Azcón J.M; Escobés R.; Galante E.; Gómez-Calmaestra R.; Manceñido D.C-; Monasterio Y.; Mora A.; Munguira M.L.; Stefanescu C.; Tinaut A., Eds.; Asociación de Naturalistas Palentinos 2019, 15-25.

- Cardoso, P.; Barton, P.H.S.; Birkhofer, K.; Chichorro, F.; Deacon, C.H.; Fartmann, T.H.; Fukushima, C.S.; Gaigher, R.; Habel, J.C.; Hallmann, C.A.; Hill, M.J.; Hochkirch, A.; Kwak, M.L.; Mammola, S.T.; Noriega, J.A.; Orfinger, A.B.; Pedraza, F.; Pryke, J.S.; Roque, F.O.; Settele, J.; Simaika, J.; Pstork, N.E.; Suhling, F.; Vorster, C.; Samways, M.J. Scientists' warning to humanity on insect extinctions. Biological Conservation, 2020, 242, 108426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, P.H.; Wagner, D.L. Agricultural intensification and climate change are rapidly decreasing insect diversity. PNAS, 2020, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Köthe, S.; Bakanov N.; Brühl C.A.; Eichler L.; Fickel T.; Gemeinholzer B.; Hörren T.; Jurewicz A.; Lux A.; Meinel G.; Mühlethaler R.; Schäffler L.; Scherber C.; Schneider F.D.; Sorg M.; Swenson S.J.; Terlau W.; Turck A.; Lehmann G.U.C. Recommendations for effective insect conservation in nature protected areas based on a transdisciplinary project in Germany. Environmental Sciences Europe, 2023, 35:102. [CrossRef]

- Parmesan, C.; Ryrholm N.; Stefanescu C.; Hill J.K.; Thomas Ch.D.; Descimon H.; Huntley B.R.; Kaila L.; Kullberg J.; Tammaru T.; Tennent W.J.; Thomas J.A.; Warren M., Poleward shifts in geographical ranges of butterfly species associated with regional warming. Nature 1999, 399, 579-583.

- Wilson, R.J.; Gutiérrez, D.; Gutiérrez, J.; Monserrat, V.J. An elevational shift in butterfly species richness and composition accompanying recent climate change. Global Change Biology, 2007, 13(9), 1873-1887. [CrossRef]

- Settele, J., Kudrna, O., Harpke, A.; Kühn, I.; Van Swaay, Ch.; Verovnik, R.; Warren, M.; Wiemers, M.; Hanspach, J. ; Hickler, T.H.; Kühn, E.; Van Halder, I. ; Veling, K.; Vliegenthart, A.; Wynhoff I.; Schweiger, O. Climatic Risk Atlas of European Butterflies. Pensift Publishers, Sofia. Bulgaria 2008, 172 pp. [CrossRef]

- Devictor, V.; Van Swaay C.; Brereton T.; Brotons L.; Chamberlain D.; Heliölä J.; Herrando S.; Julliard R.; Kuussaari M.; Lindström Å.; Reif J.; Roy D.B.; Schweiger O.; Settele J.; Stefanescu C.; Van Strien A.; Van Turnhout C.; Vermouzek Z.; Wallisdevries M.; Wynhoff I.; Frédéric J. Differences in the climate debts of birds and butterflies at a continental scale. Nature Climate Change 2012., 2, 121-124. [CrossRef]

- Rödder, D.; Schmitt,T.H., Gross, P., Ulrich, W.; Habel, J Ch. Climate change drives mountain butterfies towards the summits. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 14382. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E.M.; Esteban, M.; Aniorte, N.; Ricarte, A.; Marcos-García, M.A. Diversidad de sírfidos (Dipteta: Syrphidae) de la Estación Biológica de Torretes (Alicante, España). Cuadernos de Biodiversidad 2017, 52(52), 38-45. [CrossRef]

- Dades climatològiques de Ibi Torretes/ Font Roja, Avamet, Asociación Valenciana de Meteorología, 2023, https://www.avamet.org/mx-clima.php?

- Ríos, S.; Martínez-Francés V.; Eslava A.; Poyatos R. Guía de la estación biológica. Jardín botánico de Torretes. Editorial Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante 2021, 61 pp.

- Pollard, E.; Yates T.J. Monitoring Butterflies for Ecology and Conservation: The British Butterfly Monitoring Scheme. Editorial Springer Science & Business Media 1993, 274 pp.

- Chao, A.; Jost L. Coverage-based rarefaction and extrapolation: standardizing samples by completeness rather than size. Ecology, 2012, 93(12): 2533-2547. [CrossRef]

- Jost, L.; González-Oreja A. Midiendo la diversidad biológica: más allá del índice de Shannon. Acta Zoologica Lilloana 2012, 56: 3-14.

- Cumming, G.; Fidler F.; Vaux D.L. Error bars in experimental biology, The Journal of Cell Biology, 2007, 177(1): 7-11. [CrossRef]

- Chao, A; Gotelli N.J.; Hsieh T.C.; Sander E.L.; Ma K.H.; Colwell R.K.; Ellison A.M. Rarefaction and extrapolation with Hill numbers: A framework for sampling and estimation in species diversity studies. Ecological Monographs, 2014, 84, 45-67. [CrossRef]

- Chao, A; Ma K.H.; Hsieh T.C. iNEXT Online: Software for Interpolation and Extrapolation of Species Diversity. Program and User’s Guide published 2016 http://chao.stat.nthu.edu.tw/wordpress/software_download/inextonline/.

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An Ordination of the Upland Forest Communities of Southern Wisconsin, Ecological Monographs, 1957, 27(4), 325-349. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley R.N. PRIMER v7; PRIMER-E: Plymouth’. UK. 2015, https://www.primer-e.com/our-software/primer-version-7/.

- Robert, J.H.; Escarré, A.; García, T.; Martínez, P. Fauna Alicantina IV. Lepidópteros Ropalóceros, sus plantas nutricias y su distribución geográfica en la provincia de Alicante. Editorial Instituto de Estudios Alicantinos 1983, 435 pp.

- Viejo, J.L.; Llorente, J.J.; Martín, J.; Sánchez, C. Patrones de distribución de las mariposas de Alicante (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea y Hesperoidea). Ecología 1994, 8, 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- García-Barros, E.; Munguira, M.L.; Martín Cano, J.; Romo Benito, H.; Garcia-Pereira, P.; Maravalhas, S. Atlas de las mariposas diurnas de la Península Ibérica e islas Baleares (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea & Hesperioidea) Atlas of the butterflies of the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea & Hesperioidea). MONOGRAFÍAS SEA 11, Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa (SEA), Zaragoza 2004, 231 pp.

- Castaño, F.; Galante E. Mariposas diurnas (Lepidoptera) de la Estación Biológica de Torretes (Ibi, Alicante). Cuadernos de Biodiversidad, 2018, 55(55):, 41-53. [CrossRef]

- Atauri, J.A. , De Lucio J.V. The role of landscape structure in species richness distribution of birds, amphibians, reptiles and lepidopterans in Mediterranean landscapes. Landscape Ecology, 2001, 16, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R.J.; Brereton T.M; Dennis R.L.H.; Carbone C.; Isaac N.J.B., Butterfly abundance is determined by food availability and is mediated by species traits. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2015. 52(6): 1676-1684. [CrossRef]

- Wix, N.; Reich, M.; Schaarschmidt, F. Butterfly richness and abundance in flower strips and field margins: the role of local habitat quality and landscape context. Heliyon, 2019 5(5).

- Clench, H.K., Behavioral Thermoregulation in Butterflies. Ecology, 1966, 47(6),1021-1034. [CrossRef]

- Barranco, M.N. Factores que influyen en la diversidad y distribución de lepidópteros en el parque estatal Flor del bosque, Puebla, México. Tesis doctoral División de Ciencias Ambientales del Instituto Potosino de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, A.C., México. 2016, 96 pp.

- Bellmann, H. Guía de las mariposas de Europa. Editorial Omega, 2017, 448 pp.

- Niell, L.E. Effects of environmental factors on butterfly species in an urban setting. Tesis doctoral University of Nevada, Reno 2007, 46 pp.

- Wiklund, C.; Persson, A. Fecundity and the relation of egg weight variation to offspring fitness in the speckled wood butterfly Pararge aegeria, or why don’t butterfly females lay more eggs? Oikos 40(1), 53–63. [CrossRef]

- Merckx, T.; Van Dyck H. Mate location behaviour of the butterfly Pararge aegeria in woodland and fragmented landscapes. Animal Behaviour 2005, 70(2): 411-416. [CrossRef]

- González, F. Mariposas diurnas del parque regional de Sierra Espuña. Editorial Consejería de Desarrollo Sostenible y Ordenación del Territorio 2008, 228 pp.

- Moreno-Benítez, J. M, Mariposas diurnas de la Gran Senda de Málaga | Fichas descriptivas. Editorial Diputación de Málaga / Equipo Gran Senda de Málaga 2017, 11 pp.

- Pérez, J.L.; Zeledón, F.O. Diversidad de lepidópteros diurnos: Papilionidae, Pieridae y Nymphalidae en 11 hábitats de la zona núcleo de la reserva natural El Tisey, Estelí, Nicaragua, 2013. Trabajo de graduación Universidad Nacional Agraria 2014, 88 pp.

- Dennis, R.L.H. A resource-based habitat view for conservation: butterflies in the British landscape. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, UK, 2010, 420 pp.

| Family | Species | Abundance |

|---|---|---|

| Hesperiidae | Carcharodus alceae (Esper, 1780) | 1 |

| Erynnis tages (Linnaeus, 1758) | 1 | |

| Muschampia proto (Ochsenheimer, 1808) | 4 | |

| Lycaenidae | Aricia cramera (Eschscholtz, 1821) | 6 |

| Callophrys rubi (Linnaeus, 1758) | 54 | |

| Celastrina argiolus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 2 | |

| Glaucopsyche alexis (Poda, 1761) | 4 | |

| Glaucopsyche melanops (Boisduval 1828) | 8 | |

| Lampides boeticus (Linnaeus, 1767) | 65 | |

| Leptotes pirithous (Linnaeus, 1767) | 82 | |

| Lycaena phlaeas (Linnaeus, 1761) | 1 | |

| Polyommatus bellargus (Rottemburg, 1775) | 3 | |

| Polyommatus icarus (Rottemburg, 1775) | 2 | |

| Pseudophilotes panoptes (Hübner, 1813) | 24 | |

| Satyrium spini (Denis y Schiffermüller, 1775) | 2 | |

| Nymphalidae | Hipparchia fidia (Linnaeus, 1767) | 7 |

| Hipparchia semele (Linnaeus, 1758) | 3 | |

| Hipparchia statilinus (Hufnagel, 1766) | 3 | |

| Lasiommata maera (Linnaeus, 1758) | 8 | |

| Lasiommata megera (Linnaeus, 1767) | 83 | |

| Maniola jurtina (Linnaeus, 1758) | 2 | |

| Melanargia ines (Hoffmannsegg, 1804) | 4 | |

| Melanargia occitanica (Esper, 1793) | 1 | |

| Melitaea deione (Geyer, 1832) | 6 | |

| Melitaea phoebe (Denis y Schiffermüller, 1775) | 27 | |

| Nymphalis polychloros (Linnaeus, 1758) | 3 | |

| Pararge aegeria (Linnaeus, 1758) | 73 | |

| Pyronia bathseba (Fabricius, 1793) | 70 | |

| Vanessa atalanta (Linnaeus, 1758) | 1 | |

| Vanessa cardui (Linnaeus, 1758) | 29 | |

| Papilionidae | Iphiclides feisthamelii (Duponchel, 1832) | 11 |

| Papilio machaon Linnaeus, 1758 | 8 | |

| Zerynthia rumina (Linnaeus, 1758) | 1 | |

| Pieridae | Anthocharis euphenoides Staudinger, 1869 | 42 |

| Colias croceus (Geoffroy, 1785) | 55 | |

| Gonepteryx cleopatra (Linnaeus, 1767) | 68 | |

| Leptidea sinapis (Linnaeus, 1758) | 7 | |

| Pieris brassicae (Linnaeus, 1758) | 32 | |

| Pieris mannii (Mayer, 1851) | 8 | |

| Pieris rapae (Linnaeus, 1758) | 16 | |

| *Pieris sp. Schrank, 1801 | 61 | |

| Pontia daplidice (Linnaeus, 1758) | 69 | |

| Total | 957 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).