Submitted:

17 October 2023

Posted:

18 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Breeding Forest Species in Italy

3.2. Biogeographical Peculiarities of the Breeding Forest Avifauna in Italy and the Other Peninsulas

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with the Trend Simulated in the late 21th Century

4.2. Forest Birds on Italian Peninsula and Islands

4.3. Palaeogeographical Vicissitudes of the Mediterranean

4.4. The Climatic Phases

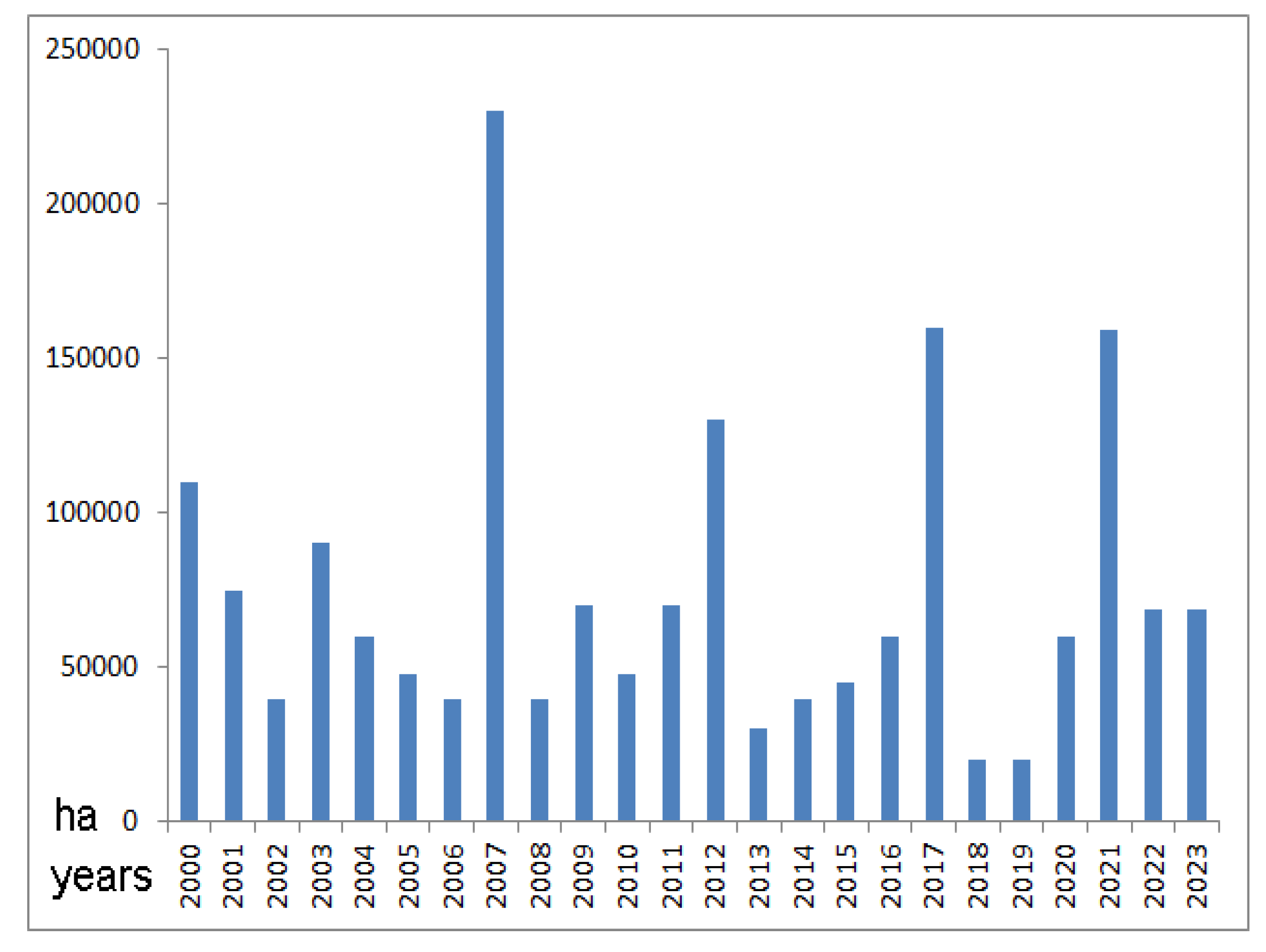

4.5. Man's Influence On Present-Day Forest Avifauna

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Dedication

| 1 | |

| 2 | The presence in Sicily of middle spotted woodpecker was erroneously reported by Minà Palumbo [34; see also 35]. |

| 3 | According to Lardelli et al. [23] the willow tit is absent from Apennines, where evidences of its presence are lacking. |

References

- Agnoletti, M.; Piras, F.; Venturi, M.; Santoro, A. Cultural values and forest dynamics: The Italian forests in the last 150 years. Forest Ecol. Manage, 2022; 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, T. Fauna d’Italia. Uccelli. Vallardi, Milano, 1872.

- Martorelli, G. Gli Uccelli d’Italia. Rizzoli and C., Milano, 1906.

- Giglioli, H.E. Secondo resoconto dei risultati dell'Inchiesta Ornitologica in Italia. Avifauna Italica. Tip. S. Giuseppe, Firenze, 1907.

- Arrigoni Degli Oddi, E. Ornitologia italiana. Hoepli, Milano, 1929.

- Schenk, H. Analisi della situazione faunistica in Sardegna. Uccelli e Mammiferi. In: SOS Fauna. Animali in pericolo in Italia. WWF Ed., Camerino, 1976, pp. 465‒556.

- Meschini, E.; Frugis, S. (Eds.) ; Atlante degli Uccelli nidificanti in Italia. Suppl. Ric. Biol. Selvaggina, 1993, 20, 1‒344.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. Ornitologia italiana. Vol. 1. Gaviidae-Falconidae. A. Perdisa Ed., Bologna, 2003.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. Ornitologia italiana. Vol. 2. Tetraonidae-Scolopacidae. A. Perdisa Ed., Bologna, 2004.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. Ornitologia italiana. Vol. 3. Stercorariidae-Caprimulgidae. A. Perdisa Ed., Bologna, 2006.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. Ornitologia italiana. Vol. 4. Apodidae-Prunellidae. A. Perdisa Ed., Bologna, 2007.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. Ornitologia italiana. Vol. 5. Turdidae-Cisticolidae. A. Perdisa Ed., Bologna, 2008.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. Ornitologia italiana. Vol. 6. Sylviidae-Paradoxornithidae. A. Perdisa Ed., Bologna, 2010.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. Ornitologia italiana. Vol. 7. Paridae- Corvidae. A. Perdisa Ed., Bologna, 2011.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. Ornitologia italiana. Vol. 8. Sturnidae-Fringillidae. A. Perdisa Ed., Bologna, 2013.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. Ornitologia italiana. Vol. 9. Emberizidae-Icteridae. A. Perdisa Ed., Bologna, 2015.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. The birds of Italy. Volume 1. Anatidae-Alcidae. Belvedere Ed., Latina, Italy, 2018.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. The birds of Italy. Volume 2. Pteroclidae-Locustellidae. Belvedere Ed., Latina, Italy, 2020.

- Corso, A. Avifauna di Sicilia. L’Epos Ed., Palermo, 2005.

- Gustin, M.; Brambilla, M.; Celada, C. Stato di conservazione e valore di riferimento favorevole per le popolazioni di uccelli nidificanti in Italia. Riv. ital. Orn, 2016, 86 (2), 3‒58. [https://sisn.pagepress.org/index.php/rio/article/view/332]. [CrossRef]

- Massa, B.; Ientile, R.; Aradis, A.; Surdo, S. One hundred and fifty years of ornithology in Sicily, with an unknown manuscript by Joseph Whitaker. Biodiversity J. 2021, 12, 27‒89. [CrossRef]

- Grussu, M. New checklist of the birds of Sardinia (Italy). Edition 2022. Aves Ichnusae, 2022, 12, 3‒62. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366733621_New_checklist_of_the_birds_of_Sardinia_Italy_Edition_2022].

- Lardelli, R.; Bogliani, G.; Caprio, E.; Celada, C.; Fraticelli, F.; Gustin, M.; Janni, O.; Pedrini, P.; Puglisi, L.; Rubolini, D.; Ruggieri, L.; Spina, F.; Tinarelli, R.; Calvi, G.; Brambilla, M. (Eds.) ; Atlante degli Uccelli nidificanti in Italia. Ed. Belvedere, Latina, Italy, 2022.

- BirdLife International, European Red List of Birds. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 2015. [https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/pdf/attachment].

- Keller, V.; Herrando, S.; Voříšek, P.; Franch, M.; Kipson, M.; Milanesi, P.; Martí, D.; Anton, M.; Klvaňová, A.; Kalyakin, M.V.; Bauer, H.-G.; Foppen, R.P.B. European Breeding Bird Atlas 2: Distribution, Abundance and Change. European Bird Census Council and Lynx ed., Barcelona, 2020.

- De Juana, E.; Varela, J.M. Birds of Spain. Lynx and SEO BirdLife, Barcelona, 2016.

- Matveiev, S.D.; Vasić, V.F. Catalogus Faunae Jugoslaviae. IV/3. Aves. Academia Scientiarum et Artium Slovenica, Ljubljana, 1973.

- Matveiev, S.D.; Vasić, V.F. Catalogus Faunae Jugoslaviae. Aves. Addenda et corrigenda. Larus, 1977, 29‒30, 123‒136.

- Handrinos, G.; Akriotis, T. The Birds of Greece. C. Helm, London, 1997.

- Pielou, E.C. Mathematical Ecology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1977.

- Huntley, B.; Green, R.E.; Collingham, Y.C.; Willis, S.G. A climatic Atlas of European breeding birds. Lynx ed., Barcelona, 2007.

- Baccetti, N.; Fracasso, G. ; Commissione Ornitologica Italiana (COI). CISO-COI Checklist of the Italian Birds – 2020. Avocetta, 2021, 44, 21‒82. [https://ciso-coi.it/coi/checklist-ciso-coi-degli-uccelli-italiani/].

- Massa, B.; Schenk, H. Similarità tra le avifaune della Sicilia, Sardegna e Corsica. Lav. Soc. it. Biogeogr, 1983, 8, 757‒799. [https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4tm114bn].

- Minà Palumbo, F. Aggiunte al catalogo degli Uccelli delle Madonie. La Favilla, 1857, 1 (10-11), 84‒86.

- Massa, B.; Sarà, M. Uccelli/Birds. Iconografia della Storia Naturale delle Madonie. Vol. IV. Sellerio ed., Palermo, 2011.

- Mac Arthur, R.H.; Wilson, E.O. The theory of island Biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1967.

- Massa, B. Il gradiente faunistico nella penisola italiana e nelle Isole. Atti Soc. ital. Sc. nat. Mus. civ. St. nat. Milano.

- Battisti, C.; Testi, A. Peninsular patterns of breeding landbird richness in Italy: on the role of climatic, orographic and vegetational factors. Avocetta, 2001, 25, 289–297. [https://www.avocetta.org/articles/vol-25-2-vdd-peninsular-patterns-of-breeding-landbird-richness-in-italy-on-the-roleem-emof-climatic-orographic-and-vegetational-factors/].

- Pons, J.-M.; Olioso, G.; Cruaud, C.; Fuchs, J. Phylogeography of the Eurasian green woodpecker (Picus viridis). J. Biogeogr, 2011, 38, 311–325. [CrossRef]

- Perktas, U.; Barrowclough, E.F.; Groth, J.G. Phylogeography and species limits in the green woodpecker complex (Aves: Picidae): multiple Pleistocene refugia and range expansion across Europe and the Near East. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 2011, 104, 710–723. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231814818_Phylogeography_and_species_limits_in_the_Green_Woodpecker_complex_Aves_Picidae_multiple_Pleistocene_refugia_and_range_expansion_across_Europe_and_the_Near_East].

- Nascetti, G.; Lovari, S.; Lanfranchi, P.; Berducou, C.; Mattiucci, S.; Rossi, L.; Bullini, L. Revision of Rupicapra Genus. III. Electrophoretic studies demonstrating species distinction of chamois populations of the Alps from those of the Apennines and Pyrenees. In: Lovari, S.; Ed. The biology and management of mountain ungulates. Croom Helm, London, 1985, pp. 56-62. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310842731_Revision_of_Rupicapra_genus_III_electrophoretic_studies_demonstrating_species_distinction_of_chamois_populations_of_the_Alps_from_those_of_the_Apennines_and_Pyrenees].

- Massa, B.; Canale, E.D.; Lo Verde, G.; Congi, G.; La Mantia, T.; Ientile, R. Mediterranean Crossbills Loxia curvirostra sensu lato (Aves, Passeriformes): new data and directions for future research. Riv. ital. Orn. 2022, 92, 41‒60. [https://sisn.pagepress.org/index.php/rio/article/view/574]. [CrossRef]

- Antonioli, F.; Lo Presti, V.; Morticelli, M.G.; Mannino, M.A.; Lambeck, K.; Ferranti, L.; Bonfiglioli, C.; Mangano, V.; Sannino, G.M.; Furlani, S.; Canese, S.P. The land bridge between Europe and Sicily over the past 40 kyrs: timing of emersion and implications for the migration of Homo sapiens. Rend. Online Soc. geol. ital, 2012, 21, 1167‒1169. [https://www.rendicontisocietageologicaitaliana.it/297/article-690/the-land-bridge-between-europe-and-sicily-over-the-past-40-kyrs-timing-of-emersion-and-implications-for-the-migration-of-em-homo-sapiens-em.html].

- Alvarez, W.; Cocozza, T.; Wezel Forese, C. Fragmentation of the Alpine orogenetic belt by microplate dispersal. Nature, 1974, 248, 309‒314.

- Vaurie, C. The birds of the Palearctic fauna. Passeriformes. H.F. and G. Witherby, London, 1959. [CrossRef]

- Vaurie, C. The birds of the Palearctic fauna. Non Passeriformes. H.F. and G. Witherby, London, 1965.

- Ientile, R. Il Codibugnolo siciliano, Aegithalos caudatus siculus (Whitaker 1901): eco-etologia, morfologia e caratterizzazione genetica. Doctoral Thesis, on Evolutionary Biology, Università degli Studi di Catania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Valvo, F. The Sicilian Long-tailed Tit, Aegithalos caudatus siculus Whitaker 1901, a subspecies not to be underestimated. In: Life on Islands. 1. Biodiversity in Sicily and surrounding islands. Studies dedicated to Bruno Massa; La Mantia, T.; Badalamenti, E.; Carapezza, A.; Lo Cascio, P.; Troia, A., Eds.; Danaus Ed., Palermo, 2020, pp. 349‒354.

- La Mantia, T.; Buscemi, I.; Mingozzi, T.; Massa, B. Data analysis of extinct and living Woodpeckers (Aves Picidae) in Sicily and Calabria (Southern Italy). Naturalista sicil, 2015, 39, 29‒49. [http://www.sssn.it/indice4.htm].

- Chamot-Rooke, N.; Rabaute, A.; Kreemer, C. Western Mediterranean Ridge mud belt correlates with active shear strain at the prism-backstop geological contact. Geology, 2005, 33, 861–864. [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, D.J. , Evolution and biogeography of madrean-tethyan sclerophyll vegetation. Ann. Missouri bot. Garden, 1975, 62, 280-334.

- Fauquette, S.; Suc, J.-P.; Bertini, A.; Popescu, S.-M.; Warny, S.; Bachiri Taoifiq, N.; Perez Villa, M.-J.; Chikhi, H.; Feddi, N.; Subally, D.; Clauzon, G.; Ferrier, J. How much did climate force the Messinian salinity crisis? Quantified climatic conditions from pollen records in the Mediterranean region. Palaeogeogr., Paleoclim., Palaeoecol, 2006, 238, 281‒301. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031018206001970]. [CrossRef]

- Blondel, J. Synthesis: the history of forest bird avifaunas of the world. In: Biogeography and ecology of forest bird communities, Keast, A., Ed.; SPB Academic Publ., The Hague, Netherlands, 1990, pp. 371‒377.

- Keast, A. Distribution and origins of forest birds. In: Biogeography and ecology of forest bird communities, Keast, A., Ed.; SPB Academic Publ., The Hague, Netherlands, 1990, pp. 45‒59.

- Pons, A. The History of the Mediterranean Shrublands. In: Ecosystems of the World-Mediterranean Type Shrublands, Vol. 11, Di Castri, F.; Goodall, W.; Specht, R.L., Eds.; Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1981, pp. 131‒138.

- Grove, A.T. The Historical context: before 1850. In: Mediterranean Desertification and Land Use, Brandt, C.J.; Thornes, J.B., Eds.; J. Wiley and Sons, Chichester, England, 1996, pp. 13‒28.

- Shugart, H.H. Patterns and ecology of forests. In: Biogeography and ecology of forest bird communities, Keast, A., Ed.; SPB Academic Publ., The Hague, Netherlands, 1990, pp. 7‒26.

- Massa, B. Gli Uccelli della fauna italiana. XIX Sem. Accad. Naz. Lincei, 1993, 79‒86.

- Massa, B. Biogeografia degli uccelli nidificanti in Italia. In: Atlante degli Uccelli nidificanti in Italia, Lardelli, R.; Bogliani, G.; Caprio, E.; Celada, C.; Fraticelli, F.; Gustin, M.; Janni, O.; Pedrini, P.; Puglisi, L.; Rubolini, D.; Ruggieri, L.; Spina, F.; Tinarelli, R.; Calvi, G.; Brambilla, M., Eds.; Ed. Belvedere, Latina, 2022, pp. 37‒46.

- Le Houérou, H.-N. L'impact de l'homme et de ses animaux sur la forêt méditerranéenne. 1980, 2, 31‒44, 155‒174. [https://www.foret-mediterraneenne.org].

- Marchetti, M.; Bertani, R.; Corona, P.; Valentini, R. Cambiamenti di copertura forestale e dell’uso del suolo nell’inventario dell’uso delle terre in Italia. Forest, 2012, 9, 170–184. [http://www.sisef.it/forest@/contents/?id=efor0696-009].

- Telleria, J.J.; Santos, T. Factors involved in the distribution of forest birds in the Iberian Peninsula. Birds Study, 1994, 41, 161‒169. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233249779_Factors_involved_in_the_distribution_of_forest_birds_in_the_Ibenan_Pennsula].

- Gregory, R.; Vorisek, P.; Van Strien, A.; Gmelig Mayling, A.W.; Jiguet, F.; Fornasari, L.; Reif, J.; Chylarecki, P.; Burfield, I.J. Population trends of widespread woodland birds in Europe. Ibis, 2007, 149 (suppl. 2), 78–97. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.J.; Noble, D.G.; Smith, K.W.; Vanhinsbergh, D. Recent declines in populations of woodland birds in Britain: a review of possible causes. British Birds, 2005, 98, 116–143.

- Gil-Tena, A.; Brotons, L.; Saura, S. Mediterranean forest dynamics and forest bird distribution changes in the late 20th century. Global Change Biol, 2009, 15, 474‒485. [CrossRef]

- Avery, M.; Leslie, R. Birds and Forestry. T. & A.D. Poyser, London, 1990.

- Pepe, A.; Caverni, L.; Maluccio, S. Rete Rurale Nazionale RRN 2014-2020. The state of italian forests, executive summary. Ministero delle politiche agricole alimentari e forestali. 2020. [https://www. reterurale.it].

- Blondel, J. Biogeography and history of forest bird faunas in the Mediterranean zone. Biogeography and ecology of forest bird communities, Keast, A., Ed.; SPB Academic Publ., The Hague, Netherlands, 1990, pp. 95‒107.

- Covas, R.; Blondel, J. Biogeography and history of the Mediterranean bird fauna. Ibis, 2008, 140, 395‒407. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229859515_Biogeography_and_history_of_the_Mediterranean_bird_fauna].

- Gustin, M.; Nardelli, R.; Brichetti, P.; Battistoni, A.; Rondinini, C.; Teofili, C. (Eds.) ; Lista Rossa IUCN degli uccelli nidificanti in Italia 2019. Comitato Italiano IUCN e Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare, Roma, 2019.

- La Mantia, T. Regolare nidificazione di Colombaccio, Columba palumbus, in gennaio in Sicilia. Riv. ital. Orn, 1994, 64, 77. [http://www.ornitologiasiciliana.it/bibliografia.php].

- Isenmann, P. Some recent bird invasions in Europe and the Mediterranean basin. In Biological Invasions in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin. Di Castri, F.; Hansen, A.J.; Debussche, M., Eds.; Kluwer Acad. Publ., Dordrecht, 1990, pp. 245‒261.

- Massa, B.; La Mantia, T. Forestry, pasture, agriculture and fauna correlated to recent changes in Sicily. Forest, 2007, 4 (4), 418‒438. [http://foresta.sisef.org/contents/?id=ifor0495-002Cached]. [CrossRef]

- La Mantia, T.; Bonaviri, L.; Massa, B. Ornithological communities as indicators of recent transformations on a regional scale: the case of the Sicily island. 2014, 38, 67‒81. [https://www.avocetta.org/articles/vol-38-2-xo-ornithological-communities-as-indicators-of-recent-transformations-on-a-regional-scale-sicilys-case/].

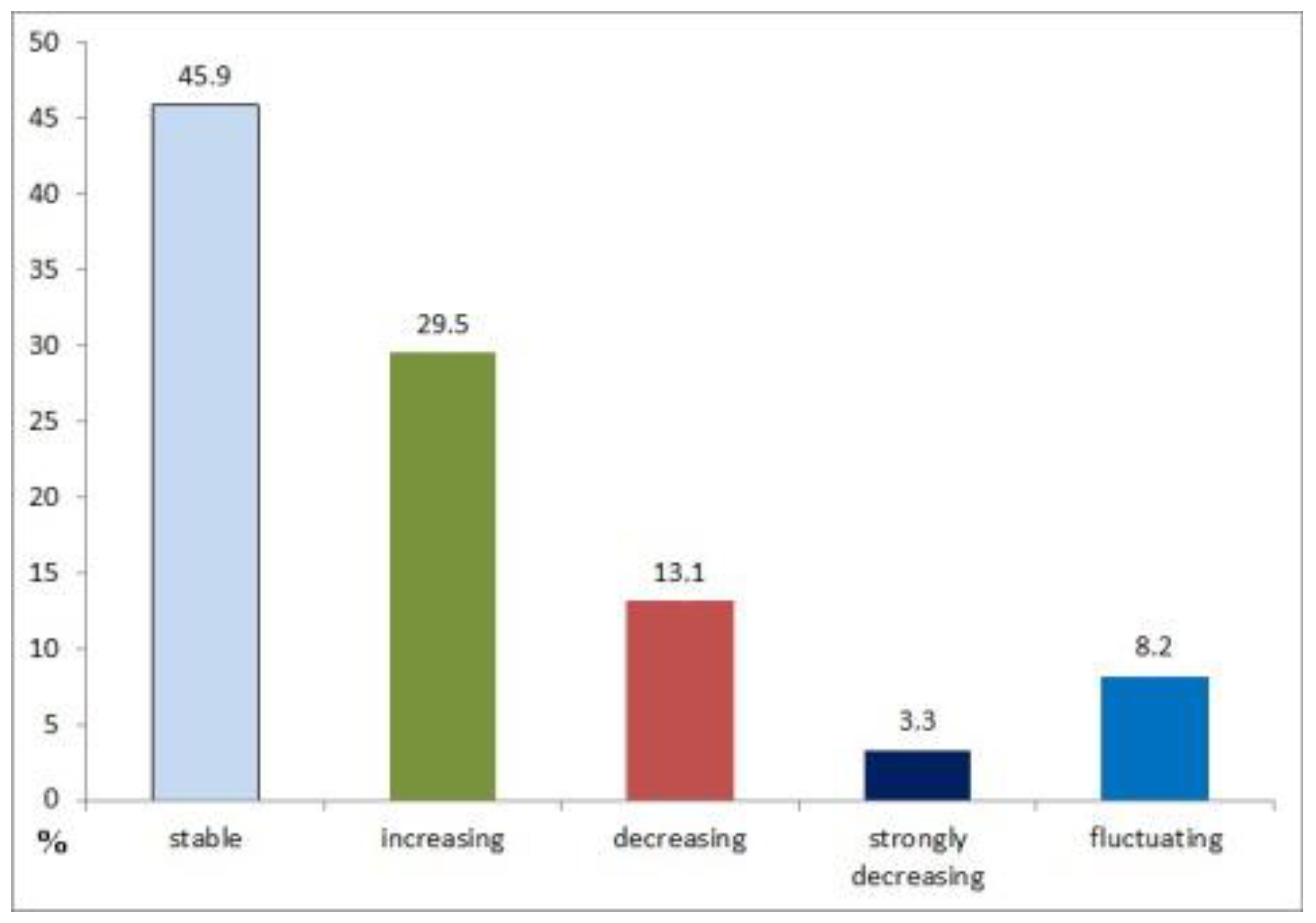

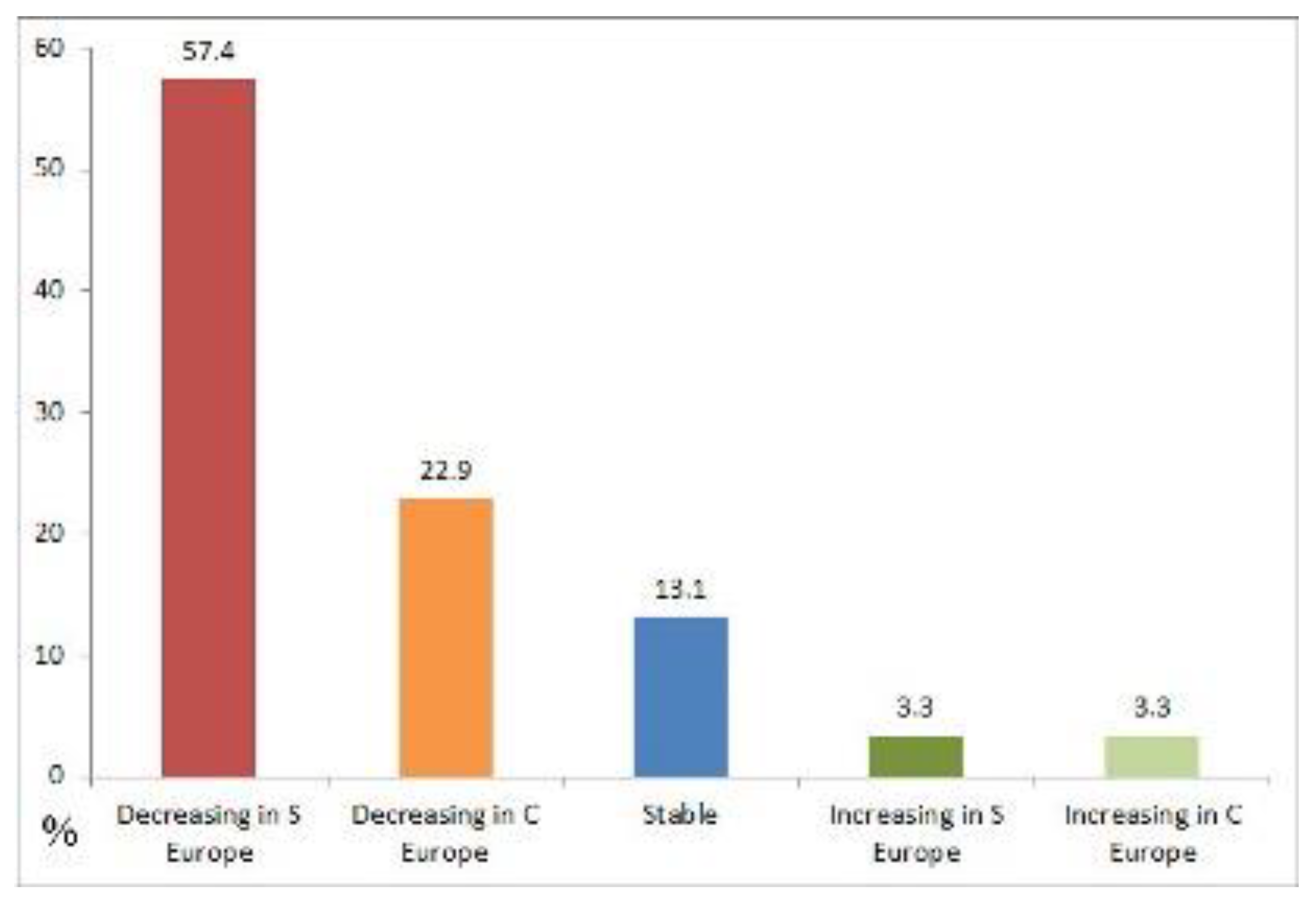

| Species (threat) | Salvadori [2] | Martorelli [3]; Giglioli [4]; Arrigoni degli Oddi [5] | Schenk [6]; Meschini and Frugis [7] | Brichetti and Fracasso [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]; Corso [19]; Gustin et al. [20]; Massa et al. [21]; Grussu [22]; Lardelli et al. [23] | Trend 1872-2022 | Huntley et al. [31], simulated trend in late XXI century | Habitat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western capercaillie Tetrao urogallus (LC) | Sedentary in Alps, decreasing | Sedentary in Alps, very decreasing | Sedentary in CE Alps, decreasing | Sedentary in CE Alps, strongly decreasing | Strongly decreasing | Decreasing in C Europe | Coniferous mixed with broadleaved woods |

| Black grouse Lyrurus tetrix (LC) | Sedentary in Alps, fairly common | Sedentary in Alps, decreasing | Sedentary in Alps, decreasing | Sedentary in Alps, decreasing | Decreasing | Decreasing in C Europe | Coniferous woods with pastures |

| Hazel grouse Bonasa bonasia (LC) | Sedentary in Alps, decreasing | Sedentary in Alps, very decreasing | Sedentary in Alps, recently increasing | Sedentary in Alps, in recent westward expansion | Fluctuating | Decreasing in S Europe | Coniferous mixed with broadleaved woods and common hazel |

| Common woodpigeon Columba palumbus (LC) | Common sedentary breeder in all Italy | Common sedentary breeder in all Italy, also in parks of some towns | Common sedentary breeder in all Italy, also in urban parks, increasing | Sedentary and migrant breeder, increasing in all Italian regions | Increasing | Stable | Coniferous and broadleaved woods |

| Stock dove Columba oenas (LC) | Common passage migrant, rare as breeding | Scarce in all Italy as breeding, more common as migrant and wintering | Very scarce migrant and rare breeder in scattered sites of Italian peninsula and Sicily | Migrant breeder fluctuating, disappearing in C-S Italy, breeding only in NW Italy | Strongly decreasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Coniferous and broadleaved woods |

| European nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus (LC) | Migrant breeder in all Italy | Migrant breeder in all Italy | Migrant breeder in all Italy | Migrant breeder in all Italy, increasing | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Wooded areas with clearings |

| Eurasian woodcock Scolopax rusticola (LC) | Common wintering, some pairs breed in N Italy | Common migrant wintering, rare breeder in Tuscany, Piedmont, Veneto, Lombardy, Trentino | Rare migrant breeder in N Italy, not confirmed in Tuscany, common wintering | Rare migrant breeder in Alps and N Apennines, common wintering | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Eurasian eagle-owl Bubo bubo (LC) | All Italian peninsula and Sicily | Sedentary in all Italian peninsula and Sicily, decreasing | Sedentary in Italian peninsula, decreasing, extinct in Sicily | Sedentary in Italian peninsula, probably fluctuating | Decreasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Cliffs next to woods |

| Boreal owl Aegolius funereus (LC) | Accidental | Very rare | Sedentary breeder in Alps | Sedentary breeder in Alps | Increasing | Decreasing in C Europe | Pure and mixed coniferous woods |

| Eurasian pygmy-owl Glaucidium passerinum (LC) | Accidental | Rare breeding in E Alps | Rare sedentary breeder in Alps | Scarce sedentary breeder in Alps | Stable | Decreasing in C Europe | Uneven-aged coniferous woods |

| Northern long-heared owl Asio otus (LC) | Common in Italian peninsula | Rare breeder in N-C Italy and Sicily | Scarce migrant breeder in N Italy, rarer in C-S Italy and Sicily, wintering | Scarce migrant and sedentary breeder in N Italy, C-S Italy, Sardinia and Sicily, wintering | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Coniferous and broadleaved woods |

| Tawny owl Strix aluco (LC) | Common in Italian peninsula and Sicily | Common sedentary in Italian peninsula and Sicily | Common sedentary breeder in all Italian peninsula and Sicily | Common sedentary breeder in all Italian peninsula and Sicily | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Ural owl Strix uralensis (LC) | Accidental | Very rare | Unrecorded as breeding | First breeding in 1994 (Udine), later increasing westwards | Increasing | Decreasing in C Europe | Beech and alpine coniferous woods |

| European honey-buzzard Pernis apivorus (LC) | Uncommon migrant | Uncommon migrant breeder in mounts over Po Valley, Tuscany, etc., decreasing | Uncommon migrant breeder in Italian peninsula, mainly in N Italy | Uncommon migrant breeder in Italian peninsula, mainly in N Italy | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Short-toed snake-eagle Circaetus gallicus (LC)* | Common migrant breeder in Latium and Tuscany, rarely wintering | Common sedentary breeder from Alps to islands | Migrant breeder in Italian peninsula, mainly NW Italy | Migrant breeder in Italian peninsula, absent in islands | Increasing | Increasing in C Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods with clearings |

| Booted eagle Hieraetus pennatus (LC) | Migrant, very rare | Migrant, very rare | Unrecorded as breeding | Migrant and wintering, common in some regions, breeding in scattered sites | Increasing | Increasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Eurasian sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus (LC) | Breeding in N Italy | Common breeder in all Italy | Common sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder, increasing in all Italy since mid ‘1980 | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Northern goshawk Accipiter gentilis (LC) | Uncommon in Sardinia and Italian peninsula | Uncommon breeder in Tuscany, Abruzzo, Molise, Alps, common in Sardinia | Sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula, mainly N Italy, and Sardinia | Sedentary breeder in all Italian peninsula and Sardinia | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Eurasian buzzard Buteo buteo (LC) | Very common in all Italy | Very common breeder in all Italy | Common sedentary breeder in all Italy | Common sedentary breeder in all Italy | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Black woodpecker Dryocopus martius (LC) | Alps, central Apennines and Sicily (rare) | Sedentary in Alps, to be confirmed in Apennines and Sicily | Sedentary in Alps and scattered zones of C-S Apennines, extinct in Sicily (1900) | Sedentary in Alps and scattered zones of C-S Apennines, accidental in Sicily | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Mature broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Grey-faced woodpecker Picus canus (LC) | Sedentary in Alps | Sedentary in Alps | Sedentary breeder in C-E Alps | Sedentary breeder in C-E Alps | Stable | Decreasing in C Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Eurasian green woodpecker Picus viridis (LC) | Very common, rare in Sicily, never found in Sardinia | Common sedentary breeder, rare in Sicily, absent in Sardinia | Sedentary breeder in all Italy, extinct in Sicily (1930) | Sedentary breeder in the peninsula, increasing | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Three-toed woodpecker Picoides tridactylus (LC) | Alps (rare) | Accidental | Very local sedentary breeder in E Alps | Very local sedentary breeder in C-E Alps | Stable | Decreasing in C Europe | Coniferous woods |

| Lesser spotted woodpecker Dryobates minor (LC) | All Italy, but no abundant | Local in all Italy, including Sicily and Sardinia | Uncommon sedentary breeder in W Alps and Apennines, extinct in Sicily (1930), no data in Sardinia from 1980 1 | Sedentary breeder in all Italian peninsula, increasing | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Middle spotted woodpecker Leiopicus medius (LC) | Central Italy (rare) | Sedentary in mounts over Po Valley, Umbria, Tuscany, Abruzzo, Latium and Sicily 2 | Sedentary breeder in scattered sites of C-S Apennines | Sedentary breeder in scattered sites of C-S Apennines, colonized Friuli | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved woods |

| Great spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos major (LC) | Common in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy, decreasing for deforestation | Sedentary breeder in all Italy, decreasing for deforestation | Sedentary breeder in all Italy, increasing | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| White-backed woodpecker Dendrocopos leucotos (LC) | East Alps | Accidental, breeder in Abruzzo | Sedentary in C Apennines and Gargano (Apulia) | Sedentary in C Apennines, unconfirmed in Apulia | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved woods |

| Eurasian hobby Falco subbuteo (LC)* | Migrant, breeding not confirmed | Migrant, breeding not confirmed | Migrant breeder in all Italy | Migrant breeder in all Italy, increasing | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Edge of broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Eurasian jay Garrulus glandarius (LC) | Common breeder in all Italy | Common breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy, increasing in urban habitats | Increasing | Stable | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Northern nutcracker Nucifraga caryocatactes (LC) | Uncommon breeder in Alps | Uncommon breeder in Alps, mainly Trentino, Veneto, Lombardy | Sedentary breeder in Alps | Sedentary breeder in Alps | Stable | Decreasing in C Europe | Alpine woods of Pinus cembra |

| Coal tit Periparus ater (LC) | Uncommon breeder in all Italy | Uncommon breeder in montane areas of Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy, increasing | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Coniferous and broadleaved woods |

| Crested tit Lophophanes cristatus (LC) | Breeding in Alps | Breeding in Alps | Sedentary breeder in Alps | Sedentary breeder in Alps and N Apennines, increasing | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Coniferous woods, also mixed with broadleaved trees |

| Marsh tit Poecile palustris (LC) | Uncommon breeder in all Italy, unrecorded in Sardinia | Uncommon breeder in all Italy, vagrant in Sardinia | Sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula and local in Sicily | Sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula and local in Sicily | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Mature broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Willow tit Poecile montanus (LC) | Breeding in Alps | Breeding in Alps | Sedentary breeder in Alps and C Apennines 3 | Sedentary breeder in Alps | Stable | Decreasing in C Europe | Montane coniferous woods |

| Great tit Parus major (LC) | Very common breeder in all Italy | Very common sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Stable | Stable | Woods and wooded areas |

| Eurasian blue tit Cyanistes caeruleus (LC) | Common breeder in all Italy | Common sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Stable | Stable | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Western Bonelli’s warbler Phylloscopus bonelli (LC)* | Breeding? | Migrant breeder, more in N Italy | Migrant breeder in Alps and Apennines, rare in S Italy | Migrant breeder in Alps, Apennines and Sardinia, rare in S Italy | Fluctuating | Increasing in C Europe | Coniferous and broadleaved woods |

| Common chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita (LC) | Breeding in all Italy | Common migrant and sedentary breeding in all Italy, wintering south of Tuscany | Migrant and sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula and Sicily | Migrant and sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula and Sicily, colonized Sardinia | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Wood warbler Phylloscopus sibilatrix (LC)* | Migrant breeder in montane areas | Migrant breeder, rare in Sardinia and Apulia | Migrant breeder in Alps and Apennines | Migrant breeder in Alps, Apennines and possible breeder in Apulia | Stable | Decreasing in C Europe | Broadleaved woods |

| Long-tailed tit Aegithalos caudatus (LC) | Very common breeder in all Italy, unrecorded in Sardinia | Common breeder in all Italy, absent in Sardinia | Sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula and Sicily | Sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula and Sicily | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Garden warbler Sylvia borin (LC)* | Rare migrant breeder in C-N Italy | Migrant breeder in montane areas, Po Valley, C Italy | Migrant breeder in N Italy, a single population in C Apennines | Migrant breeder in Alps and N Apennines, decreasing | Decreasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Woods with undergrowth |

| Eurasian blackcap Sylvia atricapilla (LC) | Very common sedentary breeder in all Italy | Very common sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods, gardens |

| Barred warbler Sylvia nisoria (LC)* | Rare migrant breeder in N-E Italy | Local migrant breeder in the Po Valley | Local migrant breeder in N Italy | Local migrant breeder in Lombardy and Friuli, decreasing | Decreasing | Stable | Thermophilic bushy woods |

| Western orphean warbler Sylvia hortensis (LC)* | Migrant breeder in montane areas of N Italy | Migrant breeder in hillsides of N Italy | Migrant breeder in scattered sites of all Italian peninsula | Migrant breeder in scattered sites of all Italian peninsula, decreasing | Decreasing | Stable | Edges of woods |

| Short-toed treecreeper Certhia brachydactyla (LC) | Common sedentary breeder in all Italy, unrecorded in Sardinia | Common sedentary breeder in all Italy, absent in Sardinia | Sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula and Sicily | Sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula and Sicily | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Mature broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Eurasian treecreeper Certhia familiaris (LC) | Breeding in Alps | Breeding in Alps and probably in Apennines | Sedentary breeder in Alps and C Apennines | Sedentary breeder in Alps and C Apennines | Stable | Decreasing in C Europe | Mature coniferous woods |

| Eurasian nuthatch Sitta europaea (LC) | Common in all Italy, unrecorded in Sardinia | Common in all Italy, absent in Sardinia | Sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula and Sicily | Sedentary breeder in Italian peninsula and Sicily | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Mature broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Northern wren Troglodytes troglodytes (LC) | Common breeder in all Italy | Common breeder in all Italy, mainly in montane and hilly areas | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Stable | Stable | Woods with undergrowth |

| Fieldfare Turdus pilaris (LC) | Breeding in Alps | Breeding in Alps? | Partially sedentary and migrant breeder in Alps | Partially sedentary and migrant breeder in Alps, declining | Decreasing | Decreasing in C Europe | Coniferous woods |

| Mistle thrush Turdus viscivorus (LC) | Common breeder in all Italy | Common breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Song thrush Turdus philomelos (LC) | Uncommon breeder in N Italy | Uncommon breeder from Alps to Apennines | Migrant breeder in Alps and Apennines | Migrant breeder in Alps and Apennines | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Ring ouzel Turdus torquatus (LC) | Rare breeder in C-N Italy | Rare breeder in Alps and Apennines | Migrant breeder in Alps and scattered sites of C Apennines | Migrant breeder in Alps and N Apennines, not confirmed in C Apennines | Decreasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Coniferous woods with bushy environments |

| European robin Erithacus rubecula (LC) | Very common breeder in all Italy | Very common breeder in montane areas of all Italy | Migrant breeder in all Italy | Abundant in all Italy, locally increasing | Increasing | Decreasing in S Europe | Woods with abundant undergrowth |

| Collared flycatcher Ficedula albicollis (LC)* | Rare migrant breeder | Local migrant breeding in Veneto, Lombardy, Piedmont, Liguria, Tuscany, Latium, Molise and probably Calabria | Local migrant breeder in Alps, N Italy, C-S Apennines, mainly in Abruzzo, Molise and Calabria | Local migrant breeder in Alps, N Italy, C-S Apennines, fluctuating | Fluctuating | Decreasing in S Europe | Mature broadleaved woods |

| Goldcrest Regulus regulus (LC) | Scarce breeder in all Italy | Scarce breeder in Italian peninsula and Sardinia | Sedentary breeder in Alps and Apennines, wintering in S Italy, unrecorded in Sardinia | Sedentary breeder in Alps and Apennines, wintering in S Italy, absent in Sardinia and Sicily | Stable | Decreasing in C Europe | Coniferous woods with undergrowth |

| Common firecrest Regulus ignicapilla (LC) | Scarce in all Italy | Scarce in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Sedentary breeder in all Italy | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Coniferous and broadleaved woods with undergrowth |

| Common chaffinch Fringilla coelebs (LC) | Very common wintering and breeder in all Italy | Very common wintering and breeder in all Italy | Migrant and sedentary breeder in all Italy | Migrant and sedentary breeder in all Italy, fluctuating, locally decreasing | Decreasing | Stable | Coniferous and broadleaved woods |

| Hawfinch Coccothraustes coccothraustes (LC) | Uncommon breeder in C-N Italy | Uncommon breeder in montane areas, common in Sardinia | Sedentary and migrant breeder in scattered sites of Italian peninsula and Sardinia | Sedentary and migrant breeder in scattered sites of Italian peninsula and Sardinia | Fluctuating | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved woods |

| Red crossbill Loxia curvirostra (LC) | Irregularly breeder in C-N Italy | Sedentary breeder in C-N Italy | Sedentary and migrant breeder in Alps, scattered sites of Apennines and Sicily | Sedentary and migrant breeder in Alps, Apennines, Sardinia and Sicily | Fluctuating | Decreasing in S Europe | Coniferous woods |

| Eurasian bullfinch Pyrrhula pyrrhula (LC) | Uncommon breeder in beech woods of C-N Italy | Uncommon breeder in beech woods of C-N Italy | Sedentary breeder in Alps and Apennines | Sedentary breeder in Alps and Apennines | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Broadleaved and coniferous woods |

| Eurasian siskin Spinus spinus (LC) | Breeding in N Italy? | Migrant, some pairs breed in Alps | Sedentary and migrant breeder in Alps, S Apennines and Sardinia | Sedentary and migrant breeder in Alps, S Apennines, Sicily, Sardinia (?) | Stable | Decreasing in S Europe | Coniferous woods, also afforestation |

| Ecological niche | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Habitat | Trees | Soil (litter) | Undergrowth |

| Phasianidae (3 species) | Coniferous mixed with broadleaved woods, coniferous woods with pastures and common hazel | Feeding | Nesting | Feeding |

| Columbidae (2 species) | Coniferous and broadleaved woods, with clearings | Feeding and nesting | Feeding | Feeding |

| Caprimulgidae (1 species) | Wooded areas with wide clearings and shrubs (aeroplanktophagous species) | Perching | Nesting | Feeding |

| Scolopacidae (1 species) | Broadleaved and coniferous woods with pastures at the edge | Nesting and feeding | ||

| Strigidae (6 species) | Cliffs next to woods, broadleaved and coniferous woods, pure and mixed coniferous woods, uneven-aged coniferous woods, beech and alpine coniferous woods, generally with big trees and holes for nesting | Nesting | Feeding | |

| Accipitridae (6 species) | Broadleaved and coniferous woods with clearings | Nesting | Feeding | |

| Picidae (8 species) | Mature broadleaved and coniferous woods with clearings | Nesting and feeding | Feeding | |

| Falconidae (1 species) | Edge of broadleaved and coniferous woods | Nesting | Feeding | |

| Corvidae (2 species) | Broadleaved and coniferous woods, alpine woods of Pinus cembra (nutcracker) | Nesting | Feeding | Feeding |

| Paridae (6 species) | Mature broadleaved and coniferous woods, also mixed with clearings | Nesting and feeding | Feeding | Feeding |

| Phylloscopidae (3 species) | Broadleaved and coniferous woods with clearings | Nesting and feeding | Feeding | |

| Aegithalidae (1 species) | Broadleaved and coniferous woods | Nesting and feeding | Feeding | |

| Sylviidae (4 species) | Woods with undergrowth, edges of woods, thermophilic bushy woods (barred warbler) | Nesting and feeding | Feeding | Nesting and feeding |

| Certhiidae (2 species) | Mature broadleaved and coniferous woods | Nesting and feeding | ||

| Sittidae (1 species) | Mature broadleaved and coniferous woods | Nesting and feeding | ||

| Troglodytidae (1 species) | Woods with undergrowth | Nesting | Feeding | Nesting and feeding |

| Turdidae (4 species) | Broadleaved and coniferous woods, coniferous woods with bushy environments | Nesting and feeding | Feeding | Feeding |

| Muscicapidae (2 species) | Woods with abundant undergrowth, mature broadleaved woods | Nesting and feeding | Feeding | Nesting and feeding |

| Regulidae (2 species) | Coniferous and broadleaved woods with undergrowth | Nesting and feeding | ||

| Fringillidae (5 species) | Coniferous and broadleaved woods | Nesting and feeding | Feeding | Feeding |

| Iberian peninsula | Italian peninsula | Balkan peninsula | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrao urogallus (3) | X | X | X |

| Lyrurus tetrix (3) | X | X | |

| Bonasa bonasia (3) | X | X | |

| Columba oenas (3) | X | X | X |

| Columba palumbus (1) | X | X | X |

| Caprimulgus europaeus (2) | X | X | X |

| Scolopax rusticola (3) | X | X | X |

| Bubo bubo (2) | X | X | X |

| Strix aluco (1) | X | X | X |

| Strix uralensis (3) | X | X | |

| Glaucidium passerinum (3) | X | X | |

| Aegolius funereus (3) | X | X | |

| Asio otus (1) | X | X | X |

| Buteo rufinus (2) | X | ||

| Buteo buteo (1) | X | X | X |

| Circaetus gallicus* (2) | X | X | X |

| Hieraetus pennatus (3) | X | X | X |

| Pernis apivorus* (2) | X | X | X |

| Accipiter nisus (2) | X | X | X |

| Accipiter gentilis (2) | X | X | X |

| Dryobates minor (2) | X | X | X |

| Leiopicus medius (3) | X | X | X |

| Dendrocopos leucotos (3) | X | X | X |

| Dendrocopos major (1) | X | X | X |

| Dendrocopos syriacus (1) | X | ||

| Picoides tridactylus (3) | X | X | |

| Dryocopus martius (2) | X | X | X |

| Picus sharpei (3) | X | ||

| Picus viridis (2) | X | X | |

| Picus canus (3) | X | X | |

| Falco subbuteo* (2) | X | X | X |

| Garrulus glandarius (1) | X | X | X |

| Nucifraga caryocatactes (3) | X | X | |

| Poecile lugubris (3) | X | ||

| Poecile palustris (2) | X | X | X |

| Poecile montanus (3) | X | X | |

| Periparus ater (2) | X | X | X |

| Lophophanes cristatus (2) | X | X | X |

| Parus major (1) | X | X | X |

| Cyanistes caeruleus (1) | X | X | X |

| Phylloscopus trochilus (2) | X | ||

| Phylloscopus collybita (2) | X | X | X |

| Phylloscopus ibericus* (3) | X | ||

| Phylloscopus bonelli* (3) | X | X | |

| Phylloscopus sibilatrix* (2) | X | X | |

| Aegithalos caudatus (1) | X | X | X |

| Sylvia atricapilla (1) | X | X | X |

| Sylvia borin* (2) | X | X | X |

| Sylvia nisoria* (3) | X | X | |

| Sylvia hortensis* (3) | X | X | |

| Certhia familiaris (2) | X | X | X |

| Certhia brachydactyla (1) | X | X | X |

| Sitta europaea (2) | X | X | X |

| Sitta krueperi (2) | X | ||

| Troglodytes troglodytes (1) | X | X | X |

| Turdus torquatus (3) | X | X | X |

| Turdus pilaris (2) | X | X | |

| Turdus philomelos (2) | X | X | X |

| Turdus viscivorus (2) | X | X | X |

| Ficedula albicollis* (3) | X | X | |

| Erithacus rubecula (1) | X | X | X |

| Regulus regulus (2) | X | X | X |

| Regulus ignicapilla (1) | X | X | X |

| Fringilla coelebs (2) | X | X | X |

| Loxia curvirostra (2) | X | X | X |

| Spinus spinus (2) | X | X | X |

| Pyrrhula pyrrhula (2) | X | X | X |

| Coccothraustes coccothraustes (3) | X | X | X |

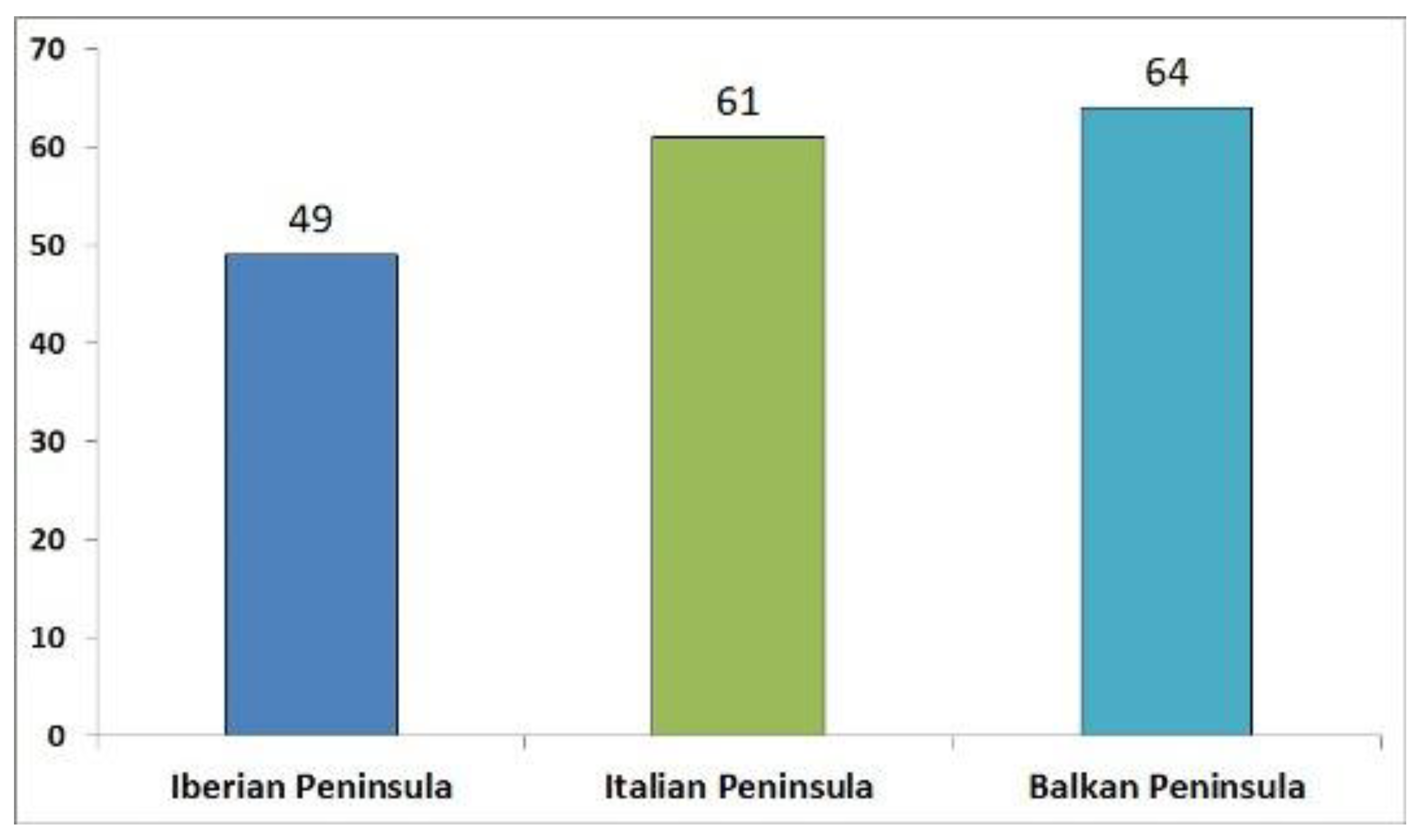

| Total No. of species | 49 | 61 | 64 |

| Sum and mean of ecological value of species | 96, 2.0 | 130, 2.1 | 134, 2.1 |

| Iberian peninsula | Italian peninsula | Balkan peninsula | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of breeding forest birds | 49 | 61 | 64 |

| Iberian/Balkan peninsulas | Iberian/Italian peninsulas | Italian/Balkan peninsulas | |

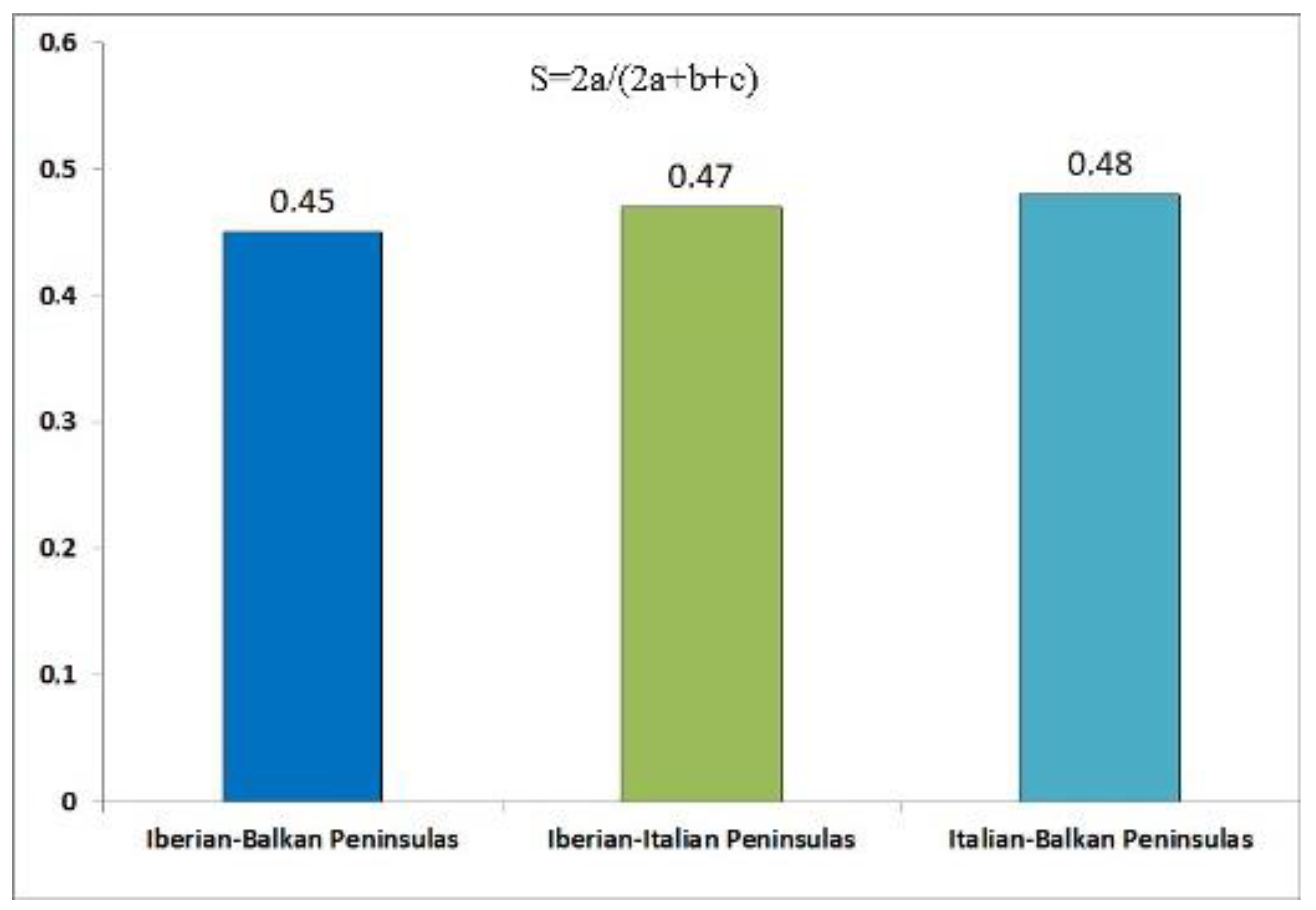

| Sørensen's similarity index | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).