Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

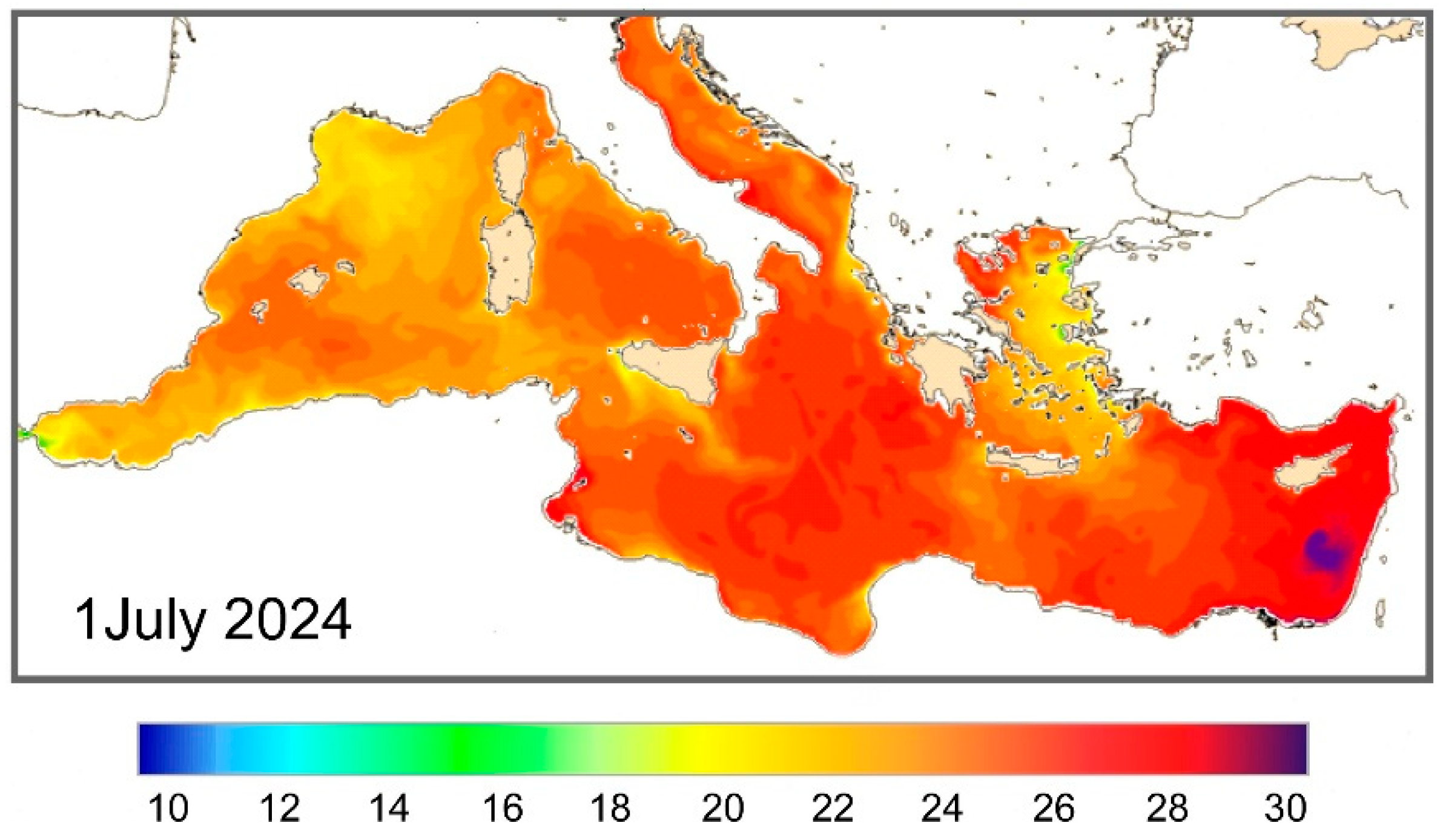

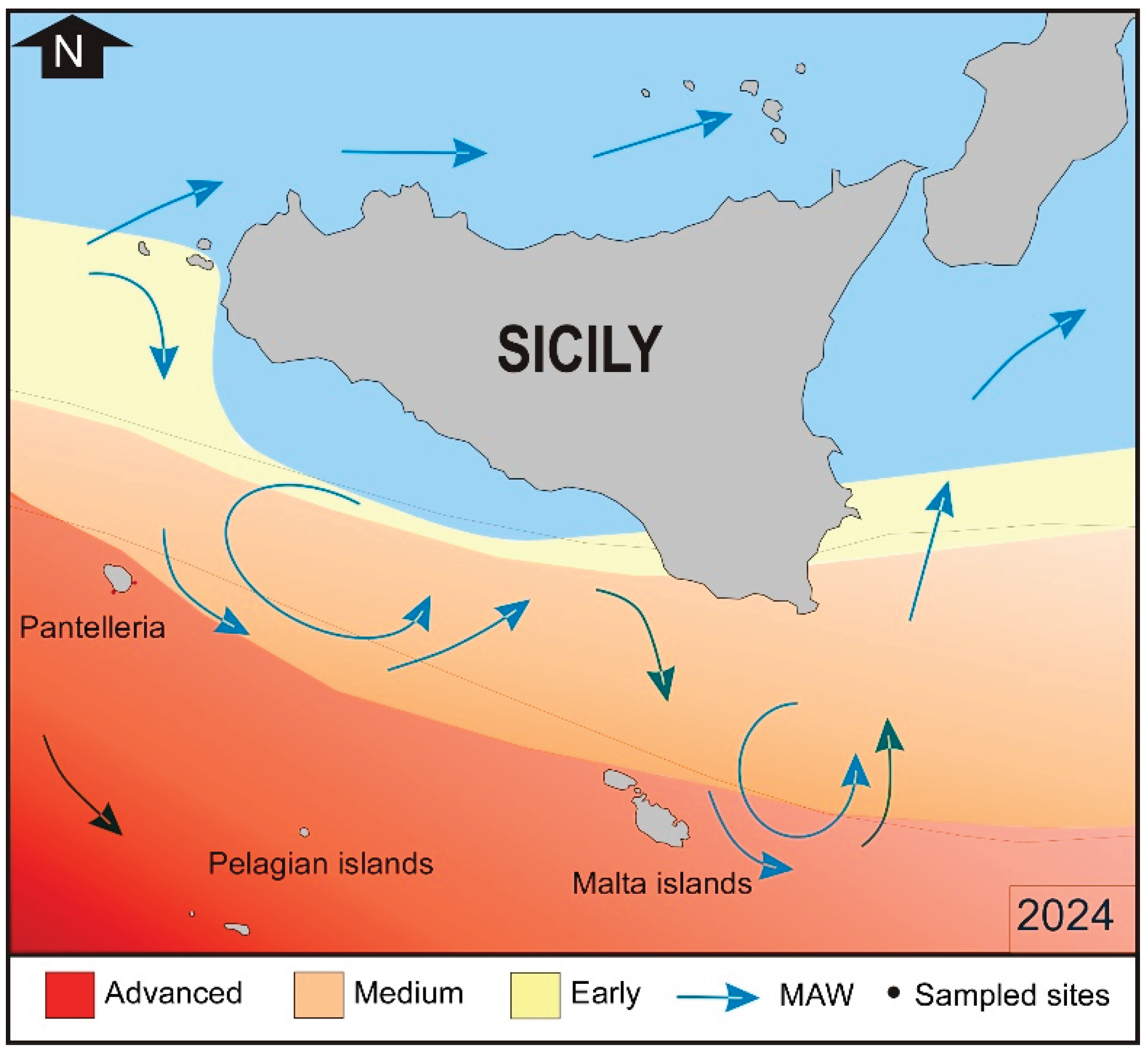

2. Study Area

2.1. Geological and Environmental Setting

2.2. Exotic Species in the Pantelleria’ Island

3. Materials and Methods

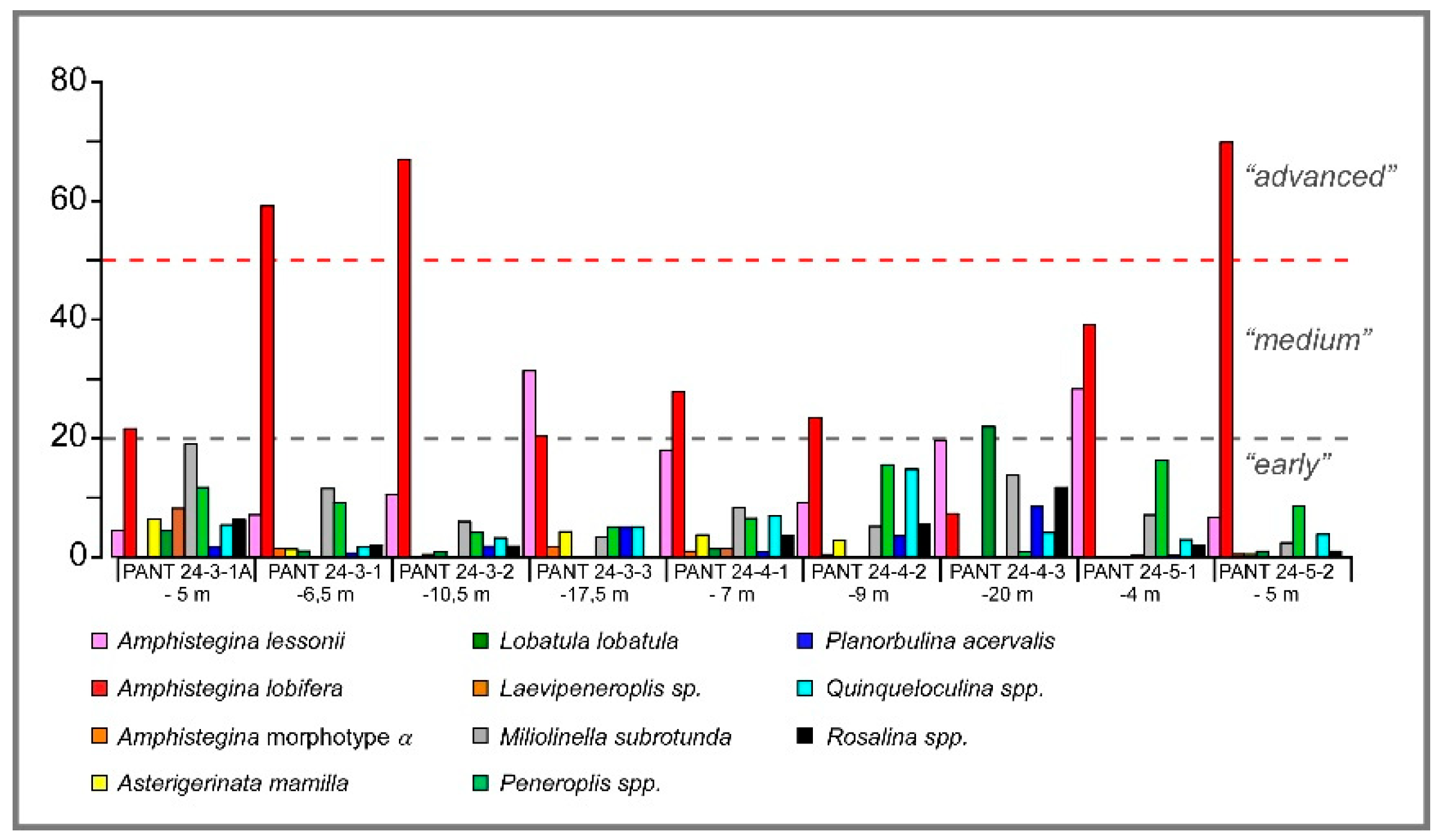

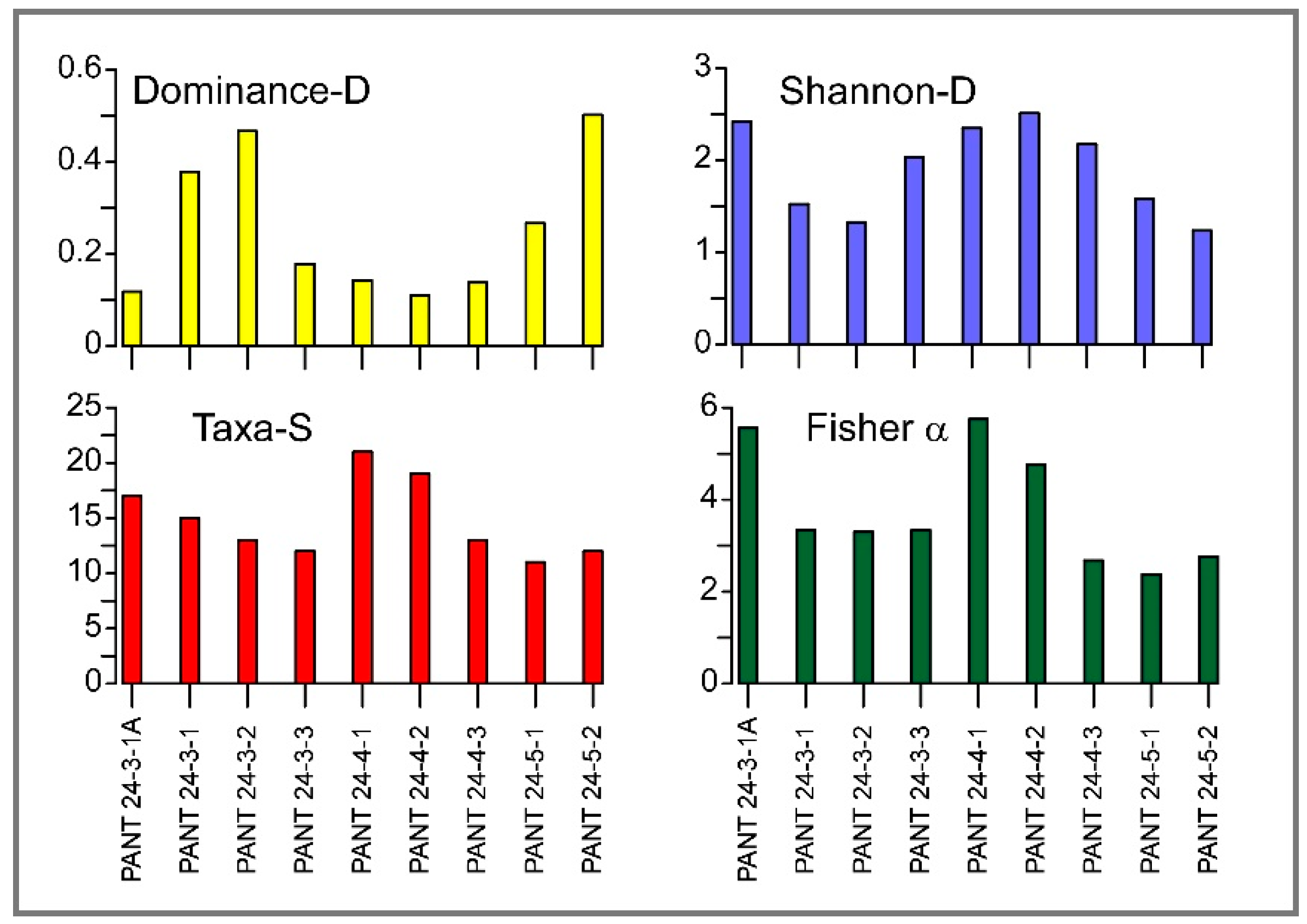

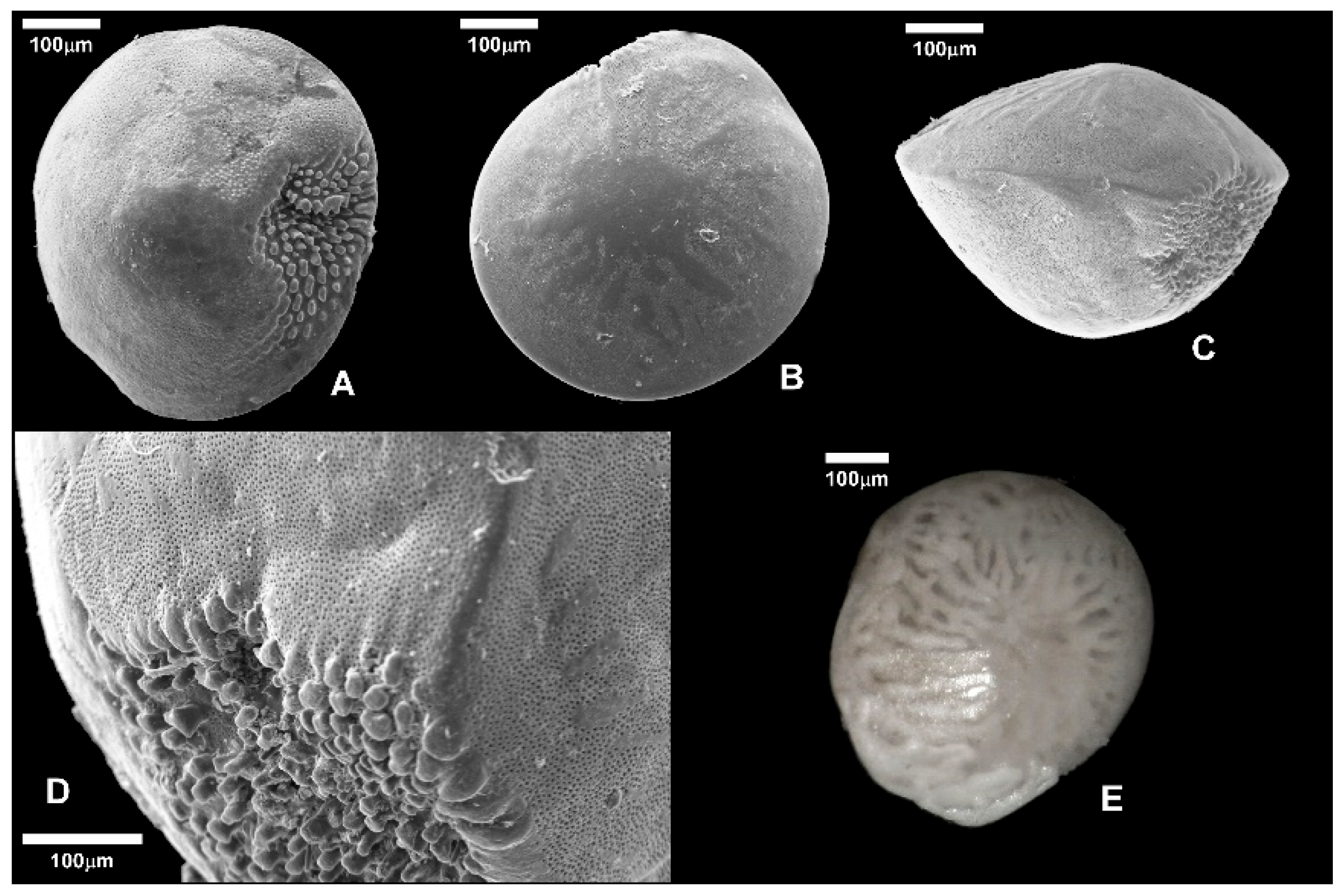

4. Results

5. Discussions

5.1. Benthic Foraminiferal Assemblages and Diversity Indexes

5.2. Benthic Foraminiferal Assemblages and Diversity Indexes

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azzurro, E.; Carnevali, O.; Bariche, M.; Andaloro, F. Reproductive features of the nonnative Siganus luridus (Teleostei, Siganidae) during early colonization at Linosa Island (Sicily Strait, Mediterranean Sea). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2006, 23, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodola, A.; Savini, D.; Occhipinti-Ambrogi, A. Alien species in the Central Mediterranean Sea: the case study of Linosa Island (Pelagian Islands, Italy). Biol. Mar. Mediterr. 2012, 19, 257–258. [Google Scholar]

- Bariche, M.; Torres, M.; Azzurro, E. The presence of the invasive Lionfish Pterois miles in the Mediterranean Sea. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2013, 14, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahnelt, H. Translocations of tropical and subtropical marine fish species into the Mediterranean. A case study based on Siganus virgatus (Teleostei: Siganidae). Biology 2016, 71, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenetos, A.; Albano, P.G.; López Garcia, E.; Stern, N.; Tsiamis, K.; Galanidi, M. Established non-indigenous species increased by 40% in 11 years in the Mediterranean Sea. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nativ, H.; Galili, O.; Almuly, R.; Einbinder, S.; Tchernov, D.; Mass, T. New record of Dendronephthya hemprichi (Family: Nephtheidae) from Mediterranean, Israel - an evidence for tropicalization? Biology 2023, 12, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirintanis, K.; Sini, M.; Ragkousis, M.; Zenetos, A.; Katsanevakis, S. Cumulative Negative Impacts of Invasive Alien Species on Marine Ecosystems of the Aegean Sea. Biology 2023, 12, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C. Global sea warming and “tropicalization” of the Mediterranean Sea: biogeographic and ecological aspects. Biogeographia 2003, 24, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raitsos, D.E.; Beaugrand, G.; Georgopoulos, D.; Zenetos, A.; Pancucci-Papadopoulou, M.A.; Theocharis, A.; Papathanassiou, E. Global climate change amplifies the entry of tropical species into the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2010, 55, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Guidelines for the Prevention of Biodiversity Loss caused by Alien Invasive Species. In Proceedings of the Fifth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, Nairobi, Kenya, 15–26 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mannino, A.M.; Balistreri, P. Invasive alien species in Mediterranean Marine Protected Areas: the Egadi Islands (Italy) case study. Biodiversity 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokeş, M.B.; Meriç, E.; Avşar, N. On the presence of alien foraminifera Amphistegina lobifera Larsen on the coasts of the Maltese Islands. Aquat. Invasions 2007, 2, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.; Cosentino, C. The first colonization of the Genus Amphistegina and other exotic benthic foraminifera of the Pelagian Islands and South-Eastern Sicily (Central Mediterranean Sea). Mar. Micropaleontol. 2014a, 111, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guastella, R.; Marchini, A.; Caruso, A.; Cosentino, C.; Evans, J.; Weinmann, A.; Langer, M.; Mancin, N. “Hidden invaders” conquer the Sicily Channel and knock on the door of the Western Mediterranean Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 225, 106234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, C.; Guastella, R.; Mancin, N.; Caruso, A. Spatial and vertical distribution of the genus Amphistegina and its relationship with the indigenous benthic foraminiferal assemblages in the Pelagian Archipelago (Central Mediterranean Sea). Mar. Micropaleontol. 2024, 188, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulpinaite, R.; Hyams-Kaphzan, O.; Langer, M. Alien and cryptogenic Foraminifera in the Mediterranean Sea: A revision of taxa as part of the EU 2020 Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2020, 21, 719–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Gupta, B.K. Foraminifera in marginal marine environments. In Modern Foraminifera; Sen Gupta, B.K., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.B.; Medioli, F.S.; Schafer, C.T. Monitoring in Coastal Environments Using Foraminifera and Thecamoebian Indicators; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.W. Ecology and Applications of Benthic Foraminifera; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yanko, V.; Kronfeld, J.; Flexer, A. Response of benthic foraminifera to various pollution sources: implications for pollution monitoring. J. Foraminifer. Res. 1994, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontalini, F.; Buosi, C.; Da Pelo, S.; Coccioni, R.; Cherchi, A.; Bucci, C. Benthic foraminifera as bio-indicators of trace element pollution in the heavily contaminated Santa Gilla lagoon (Cagliari, Italy). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 858–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.; Cosentino, C.; Tranchina, L.; Brai, M. Response of benthic foraminifera to heavy metal contamination in marine sediments (Sicilian coasts, Mediterranean Sea). Chem. Ecol. 2011, 27, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, C.; Pepe, F.; Scopelliti, G.; Calabrò, M.; Caruso, A. Benthic foraminiferal response to trace element pollution. The case study of the Gulf of Milazzo, NE Sicily (Central Mediterranean Sea). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 8777–8802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machain-Castillo, M.L.; Ruiz-Fernández, A.C.; Alonso-Rodríguez, R.; Sanchez-Cabeza, J.A.; Gío-Argáez, F.R.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, A.; Villegas-Hernández, R.; Mora-Garcíad, A.I.; Gómez-Ponce, M.A.; Pérez-Bernal, L.H. Anthropogenic and natural impacts in the marine area of influence of the Grijalva - Usumacinta River (Southern Gulf of Mexico) during the last 45 years. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 156, 111245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamin, L.; Pierfranceschi, G.; Romano, E. Anthropogenic impact due to mining from a sedimentary record of a marine coastal zone (SW Sardinia, Italy). Mar. Micropaleontol. 2021, 169, 102036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.R. Studies of recent Amphistegina, taxonomy and some ecological aspects. Isr. J. Earth Sci. 1976, 25, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zmiri, A.; Kahan, D.; Hochstein, S.; Reiss, Z. Phototaxis and thermotaxis in some species of Amphistegina (Foraminifera). J. Protozool. 1974, 21, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, M.R.; Hottinger, L. Biogeography of selected “larger” foraminifera. Micropaleontology 2000, 46, 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, M.R. Foraminifera from the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. In Aqaba-Eilat, the Improbable Gulf; Por, F.D., Ed.; Magnes Press: Jerusalem, 2008; pp. 397–415. [Google Scholar]

- Hottinger, L.; Halicz, E.; Reiss, Z. Recent Foraminiferida from the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea. Dela SAZU, Classis IV, Historia Naturalis, Vol. 33; Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti: Ljubljana, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Palme, T.; Nagy, M.; Heinz, P. Quantifying rates of oxygen production and consumption in the benthic foraminifer Amphistegina lobifera at different temperatures. Mar. Biol. 2025, 172, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, M.R.; Silk, M.T.; Lipps, J.H. Global ocean carbonate and carbon dioxide production; the role of reef Foraminifera. J. Foraminifer. Res. 1997, 27, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resig, J.M. Age and preservation of Amphistegina (foraminifera) in Hawaiian beach sand: implications for sand turnover rate and resource renewal. Mar. Micropaleontol. 2004, 50, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dämmer, L.K.; Ivkić, A.; de Nooijer, L.; Renema, W.; Webb, A.E.; Reichart, G.-J. Impact of dissolved CO2 on calcification in two large, benthic foraminiferal species. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyams, O.; Almogi-Labin, A.; Benjamini, C. Larger foraminifera of the south-eastern Mediterranean shallow continental shelf off Israel. Isr. J. Earth Sci. 2002, 51, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokeş, M.B.; Meriç, E.; Avşar, N. On the presence of alien foraminifera Amphistegina lobifera Larsen on the coasts of the Maltese Islands. Aquat. Invasions 2007, 2, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriç, E.; Avşar, N.; Nazik, A.; Yokeş, M.B.; Dinçer, F. A review of benthic foraminifers and ostracodes of the Antalya coast. Micropaleontology 2008, 54, 199–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphyllou, M.V.; Koukousioura, O.; Dimiza, M.D. The presence of the Indo-Pacific symbiont-bearing foraminifer Amphistegina lobifera in Greek coastal ecosystems (Aegean Sea, Eastern Mediterranean). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2009, 10, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenetos, A.; Gofas, S.; Verlaque, M.; Çinar, M.E.; García Raso, J.G.; Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C.; Azzurro, E.; Bilecenoglu, M.; Froglia, C.; et al. Alien species in the Mediterranean Sea by 2010. A contribution to the application of European Union's Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Part I. Spatial distribution. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2010, 11, 381–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Tair, N.K.; Langer, M.R. Foraminiferal Invasions: The Effect of Lessepsian Migration on the Diversity and Composition of Benthic Foraminiferal Assemblage Around Cyprus (Mediterranean Sea). Forams 2010-International Symposium on Foraminifera, Bonn, 2010, p. 42 (Abstract).

- Guastella, R.; Marchini, A.; Caruso, A.; Evans, J.; Cobianchi, M.; Cosentino, C.; Langone, L.; Lecci, R.; Mancin, N. Reconstructing Bioinvasion Dynamics through Micropaleontologic Analysis highlights the Role of Temperature Change as a driver of Alien Foraminifera Invasion. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 675807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukousioura, O.; Dimiza, M.D.; Triantaphyllou, M.V. Alien foraminifers from Greek coastal areas (Aegean Sea, Eastern Mediterranean). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2010, 11, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, M.R.; Mouanga, G.H. Invasion of amphisteginid foraminifera in the Adriatic Sea. Biol. Invasions 2016, 18, 1335–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K.; Hildreth, W. Geology of Pantelleria, a peralkaline volcano in the Strait of Sicily. Bull. Volcanol. 1986, 48, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neave, D.A.; Fabbro, G.; Herd, R.A.; Petrone, C.M.; Edmonds, M. Melting, Differentiation and Degassing at the Pantelleria Volcano, Italy. J. Petrology 2012, 53, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotolo, S.G.; Scaillet, B.; La Felice, S.; Vita-Scaillet, L. Paroxysmal eruption of Pantelleria volcano (Italy) at 45 ka: insight into caldera formation, magma recharge and compositional evolution. J. Petrology 2013, 54, 767–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.; Censi, P.; Aricò, P.; Meli, C.; Sprovieri, M. Astronomical dating of two Pliocene alkaline volcanic ash layers in the Capo Rossello area (southern Sicily, Italy): implications for the beginning of the rifting in the Sicily Channel. Bull. Soc. Géol. France 2009, 180, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Marine Service. Available online: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/.

- Carapezza, A. Gli Eterotteri Dell’Isola Di Pantelleria (Insecta, Heteroptera). Il Nat. Sicil. 1981, 4, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Galasso, G.; Montoleone, E.; Federico, C. Persicaria senegalensis (Polygonaceae), entità nuova per la flora italiana, e chiave di identificazione delle specie del genere Persicaria in Italia. NHS Nat. Hist. Sci. Atti Soc. Ital. Sci. Nat. Museo Civ. Storia Nat. Milano 2014, 1, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Luca, M.; Toma, L.; Severini, F.; Boccolini, D.; D’Avola, S.; Todaro, D.; Stancanelli, A.; Antoci, F.; La Russa, F.; Casano, S.; Sotera, S.D.; Carraffa, E.; Versteirt, V.; Schaffner, F.; Romi, R.; Torina, A. First record of the invasive mosquito species Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) on the southernmost Mediterranean islands of Italy and Europe. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofaro, M.; Sforza, R.F.H.; Roselli, G.; Paolini, A.; Cemmi, A.; Musmeci, S.; Anfora, G.; Mazzoni, V.; Grodowitz, M. Effects of Gamma Irradiation on the Fecundity, Fertility, and Longevity of the Invasive Stink Bug Pest Bagrada hilaris (Burmeister) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Insects 2022, 13, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, E.; Magoga, G.; Mazza, G. New records based on citizen-science report alien land planarians in the three remaining Italian regions and Pantelleria Island, and first record of Dolichoplana striata (Platyhelminthes Tricladida Contineticola Geoplanidae) in Italy. Redia 2022, 105, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minissale, P.; Cambria, S.; Montoleone, E.; Tavilla, G.; Giusso del Galdo, G.; Sciandrello, S.; Badalamenti, E.; La Mantia, T. The alien vascular flora of the Pantelleria Island National Park (Sicily Channel, Italy): new insights into the distribution of some potentially invasive species. BioInvasions Rec. 2023, 12, 861–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, A.; Musmeci, S.; Mainardi, C.E.; Peccerillo, C.; Cemmi, A.; Di Sarcina, I.; Marini, F.; Sforza, R.F.H.; Cristofaro, M. Age-dependent variation in longevity, fecundity and fertility of gamma-irradiated Bagrada hilaris (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae): insights for a sustainable SIT program. Insects 2025, 16, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccone, G.; Scammacca, B.; Cinelli, F.; Sartoni, G.; Furnari, G. Studio preliminare sulla tipologia della vegetazione sommersa del Canale di Sicilia e isole vicine. Giorn. Bot. Ital. 1972, 106, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccone, G.; Sortino, M.; Solazzi, A.; Tolomio, C. Tipologia e distribuzione estiva della vegetazione sommersa dell’isola di Pantelleria. Lav. Reale Ist. Bot. Reale Giard. Colon. Palermo 1973, 25, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, R.; Calvo, S.; Sortino, M. Contributo alla conoscenza della flora sommersa del porto di Pantelleria (Canale di Sicilia). Giorn. Bot. Ital. 1978, 112, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, S.; Sortino, M. Tipologia e distribuzione della vegetazione sommersa del porto di Pantelleria (Canale di Sicilia). Inform. Bot. Ital. 1979, 11, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Marletta, G.; Lombardo, A. The Fucales (Ochrophyta, Phaeophyceae) of the Island of Pantelleria (Sicily Channel, Mediterranean Sea): a new contribution. Ital. Bot. 2023, 15, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetta, F.; Agius, D.; Balistreri, P.; Bariche, M.; Bayhan, Y.K.; Çakir, M.; Ciriaco, S.; Corsini-Foka, M.; Deidun, A.; El Zrelli, R.; Ergüden, D.; Evans, J.; Ghelia, M.; Giavasi, M.; Kleitou, P.; Kondylatos, G.; Lipej, L.; Mifsud, C.; Özvarol, Y.; Pagano, A.; Portelli, P.; Poursanidis, D.; Rabaoui, L.; Schembri, P.J.; Taşkin, E.; Tiralongo, F.; Zenetos, A. New Mediterranean Biodiversity Records (October 2015). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2015, 16, 682–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castriota, L.; Falautano, M.; Maggio, T.; Perzia, P. The Blue Swimming Crab Portunus segnis in the Mediterranean Sea: Invasion Paths, Impacts and Management Measures. Biology 2022, 11, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenzia Regionale per la Protezione dell’Ambiente, Arpa Sicilia. Progetto Caulerpa – Indagini ambientali e rilievi sulla diffusione della Caulerpa nel Canale di Sicilia, 2014, 79 pp.

- Title of Site. Available online: https://www.regionieambiente.it/specie-aliene-ispra/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Walton, W.R. Techniques for recognition of living foraminifera. Contrib. Cushman Found. Foram. Res. 1952, 3, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schönfeld, J.; Alve, E.; Geslin, E.; Jorissen, F.; Korsun, S.; Spezzaferri, S.; Members of The, Fobimo. The Fobimo (FOraminiferal BIo-MOnitoring) initiative—towards a standardized protocol for soft-bottom benthic foraminiferal monitoring studies. Mar. Micropaleontol. 2012, 94–95, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeblich, A.R.; Tappan, J.H. Foraminiferal Genera and their Classification, 4th ed.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cimerman, F.; Langer, M.R. Mediterranean Foraminifera. Slovenska Akademija Znanosti in Umetnosti, 33, Ljubljana, 1991.

- Caruso, A.; Cosentino, C. Classification and Taxonomy of Modern Benthic Shelf Foraminifera of the Central Mediterranean Sea. In Foraminifera: Aspects of Classification; Georgescu, M.D., Ed.; Nova Publishers: New York, USA, 2014b; pp. 249–313. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.A.; Corbet, A.S.; Williams, C.B. The relationship between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. J. Anim. Ecol. 1943, 12, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.W. Distribution and Ecology of Living Benthic Foraminiferids; Heinemann Educational Books: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Guastella, R.; Evans, J.; Mancin, N.; Caruso, A.; Marchini, A. Assessing the effect of Amphistegina lobifera invasion on infralittoral benthic foraminiferal assemblages in the Sicily Channel (Central Mediterranean). Mar. Environ. Res. 2023, 192, 106247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinmann, A.E.; Koukousioura, O.; Triantaphyllou, M.V.; Langer, M.R. Invasive shallow water foraminifera impacts local biodiversity mostly at densities above 20 %: the case of Corfu Island. Web Ecol. 2023, 23, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgarrella, F.; Moncharmont Zei, M. Benthic foraminifera of the Gulf of Naples (Italy): systematics and autoecology. Boll. Soc. Paleontol. Ital. 1993, 32, 145–264. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, M.R. Epiphytic foraminifera. Mar. Micropaleontol. 1993, 20, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Title of Site. Available online: https://marine.copernicus.eu/it/ocean-climate-portal/sea-surface-temperature (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- DIRECTIVE 2008/56/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 17 June 2008 establishing a framework for community action in the field of marine environmental policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive). Official Journal of the European Union.

- EU. Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species. Official Journal of the European Union L 317, 35–55.

- Perzia, P.; Cillari, T.; Crociata, G.; Deidun, A.; Falautano, M.; Franzitta, G.; Galdies, J.; Maggio, T.; Vivona, P.; Castriota, L. Using Local Ecological Knowledge to Search for Non-Native Species in Natura 2000 Sites in the Central Mediterranean Sea: An Approach to Identify New Arrivals and Hotspot Areas. Biology 2023, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sites | Latitude | Longitude | sites | SST (°C) | SSS (‰) | Depth (m) | Sample type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gadir | 36 48' 42'' N | 12 01' 32'' E | PANT 24-3-1A | 24* - 22.6 | 37*- 37.5 | 5 | P. oceanica's rhizomes |

| PANT 24-3-1 | 6,5 | P. oceanica's rhizomes | |||||

| PANT 24-3-2 | 10,5 | P. oceanica's rhizomes | |||||

| PANT 24-3-3 | 17,5 | P. oceanica's rhizomes | |||||

| Cala Tramontana | 36 47' 54'' N | 12 02' 52'' E | PANT 24-4-1 | 24* - 22.8 | 37* - 37.5 | 7 | brown algae Halopteris scoparia |

| PANT 24-4-2 | 9 | P. oceanica's rhizomes | |||||

| PANT 24-4-3 | 20 | brown algae Halopteris scoparia | |||||

| Balata dei Turchi | 36 44' 10'' N | 12 01' 09'' E | PANT 24-5-1 | 24* - 22.9 | 37*- 37.5 | 4 | brown algae Halopteris scoparia |

| PANT 24-5-2 | 5 | sediment |

| Sampling sites | N. of living specimens | N. of dead specimens | N. of total specimens (living + dead) |

Total living foraminifera (%) | Total dead foraminifera (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANT 24-3-1A | 111 | 0 | 111 | 100,00 | 0,00 |

| PANT 24-3-1 | 296 | 0 | 296 | 100,00 | 0,00 |

| PANT 24-3-2 | 218 | 0 | 218 | 100,00 | 0,00 |

| PANT 24-3-3 | 118 | 31 | 149 | 79,19 | 20,81 |

| PANT 24-4-1 | 216 | 13 | 229 | 94,32 | 5,68 |

| PANT 24-4-2 | 251 | 15 | 266 | 94,36 | 5,64 |

| PANT 24-4-3 | 342 | 19 | 361 | 94,74 | 5,26 |

| PANT 24-5-1 | 240 | 3 | 243 | 98,77 | 1,23 |

| PANT 24-5-2 | 209 | 81 | 290 | 72,07 | 27,93 |

| Benthic foraminiferal species | PANT 24-3-1A | PANT 24-3-1 | PANT 24-3-2 | PANT 24-3-3 | PANT 24-4-1 | PANT 24-4-2 | PANT 24-4-3 | PANT 24-5-1 | PANT 24-5-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adelosina sp1. | 0,90 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 3,59 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Adelosina sp.2 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,93 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Amphisorus hemprichii | 0,00 | 0,34 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Amphistegina lobifera | 21,62 | 59,12 | 66,97 | 20,34 | 27,78 | 23,51 | 7,31 | 39,17 | 69,86 |

| Amphistegina lessonii | 4,50 | 7,09 | 10,55 | 31,36 | 18,06 | 9,16 | 19,59 | 28,33 | 6,70 |

| Amph. morphotype alfa | 0,00 | 1,35 | 0,00 | 1,69 | 0,93 | 0,40 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,48 |

| Asterigerinata mamilla | 6,31 | 1,35 | 0,46 | 4,24 | 3,70 | 2,79 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,48 |

| Bolivina catanensis | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,40 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Cribroelphidium sp. | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,80 | 0,29 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Cyclocibicides vermiculatus | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 4,24 | 0,93 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Cymbaloporetta squammosa | 2,70 | 0,68 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 1,39 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Laevipeneroplis sp. | 8,11 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 1,39 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,42 | 0,00 |

| Lachlanella variolata | 2,70 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Lobatula lobatula | 4,50 | 1,01 | 0,92 | 0,00 | 1,39 | 0,00 | 21,93 | 0,00 | 0,96 |

| Miliolinella subrotunda | 18,92 | 11,49 | 5,96 | 3,39 | 8,33 | 5,18 | 13,74 | 7,08 | 2,39 |

| Peneroplis pertusus | 10,81 | 9,12 | 3,21 | 3,39 | 5,56 | 13,55 | 0,00 | 16,25 | 6,22 |

| Peneroplis planatus | 0,90 | 0,00 | 0,92 | 1,69 | 0,93 | 1,99 | 0,88 | 0,00 | 2,39 |

| Planorbulina acervalis | 1,80 | 0,68 | 1,83 | 5,08 | 0,93 | 3,59 | 8,48 | 0,42 | 0,00 |

| Quinqueloculina sp.1 | 0,90 | 1,35 | 0,92 | 5,08 | 3,70 | 7,17 | 2,34 | 0,83 | 1,44 |

| Quinqueloculina sp.2 | 4,50 | 0,34 | 2,29 | 0,00 | 2,78 | 7,57 | 1,75 | 2,08 | 2,39 |

| Quinqueloculina sp.3 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,46 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Quinqueloculina sp.4 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 2,34 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Rosalina bradyi | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,80 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Rosalina obtusa | 6,31 | 2,03 | 1,83 | 0,00 | 3,70 | 4,78 | 11,70 | 2,08 | 0,96 |

| Spiroloculina excavata | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 1,99 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Spiroloculina sp. | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,46 | 1,99 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Textularia pala | 1,80 | 3,04 | 1,38 | 16,10 | 12,50 | 7,57 | 4,39 | 2,50 | 5,74 |

| Tretomphalus bulloides | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,46 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 |

| Vertebralina striata | 2,70 | 1,01 | 2,75 | 3,39 | 3,70 | 3,19 | 5,26 | 0,83 | 0,00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).