Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

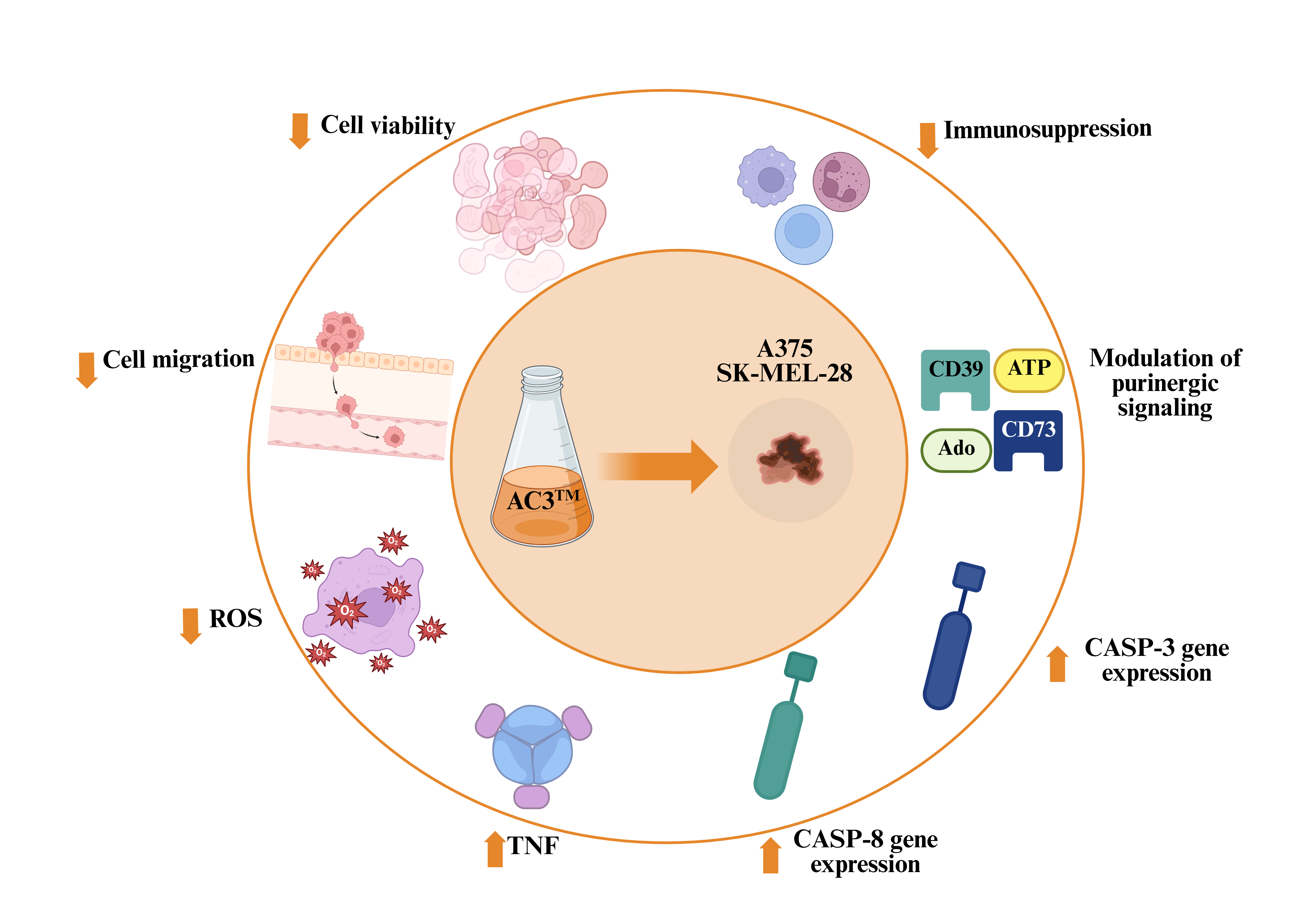

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Cell Culture and Exposure to AC3TM

2.3. Cell Viability by MTT Assay

2.4. Cell Viability by Fluorescence Microscopy Assay

2.5. Measurement of Mitochondrial Transmembrane Potential (ΔΨm)

2.6. Wound-Healing Migration Assay

2.7. Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

2.8. Gene Expression

2.9. Assessment of CD39 and CD73 Enzymatic Activities

2.10. Protein Determination

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

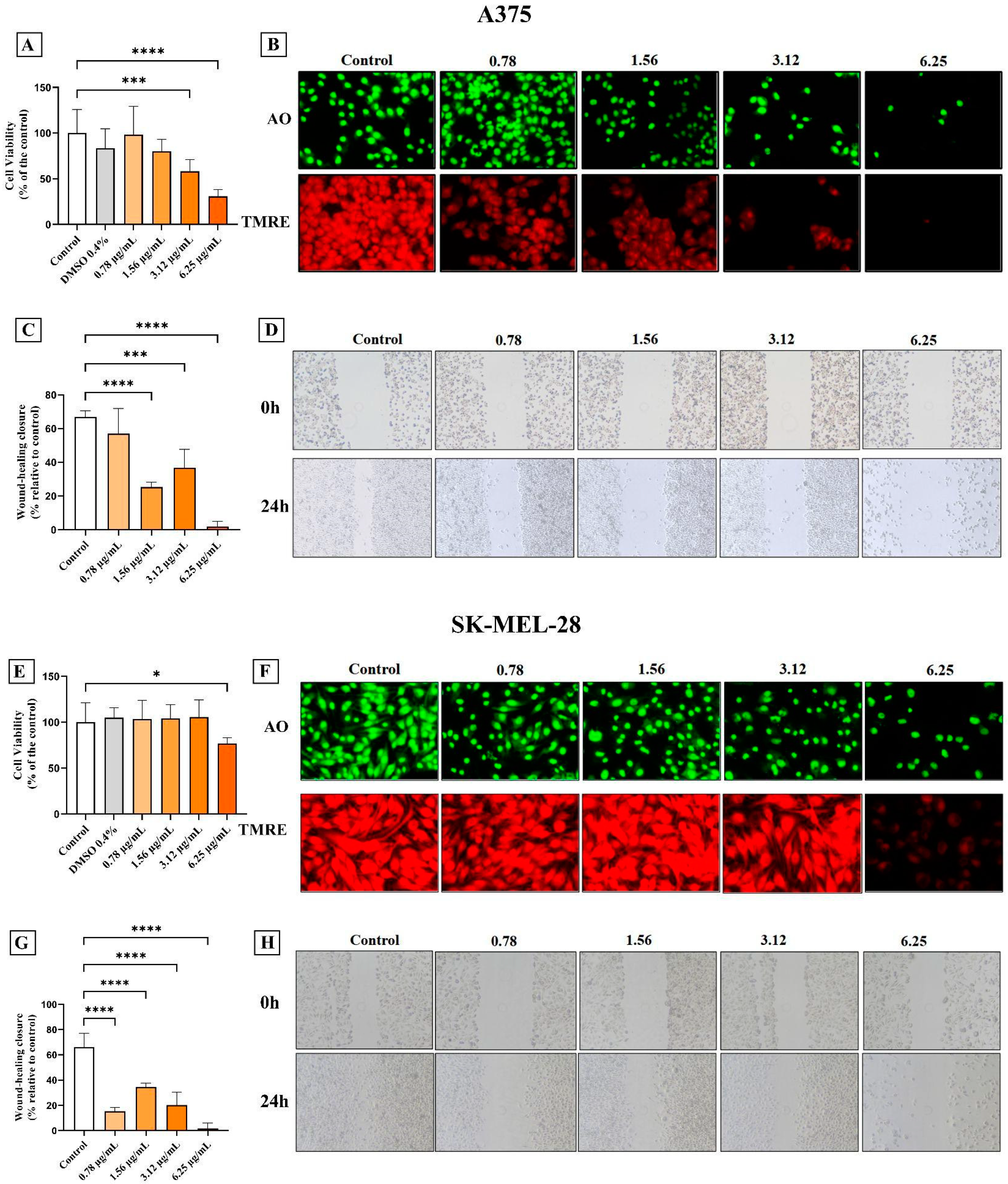

3.1. AC3TM Decreased Viability and Migration of Melanoma Cells

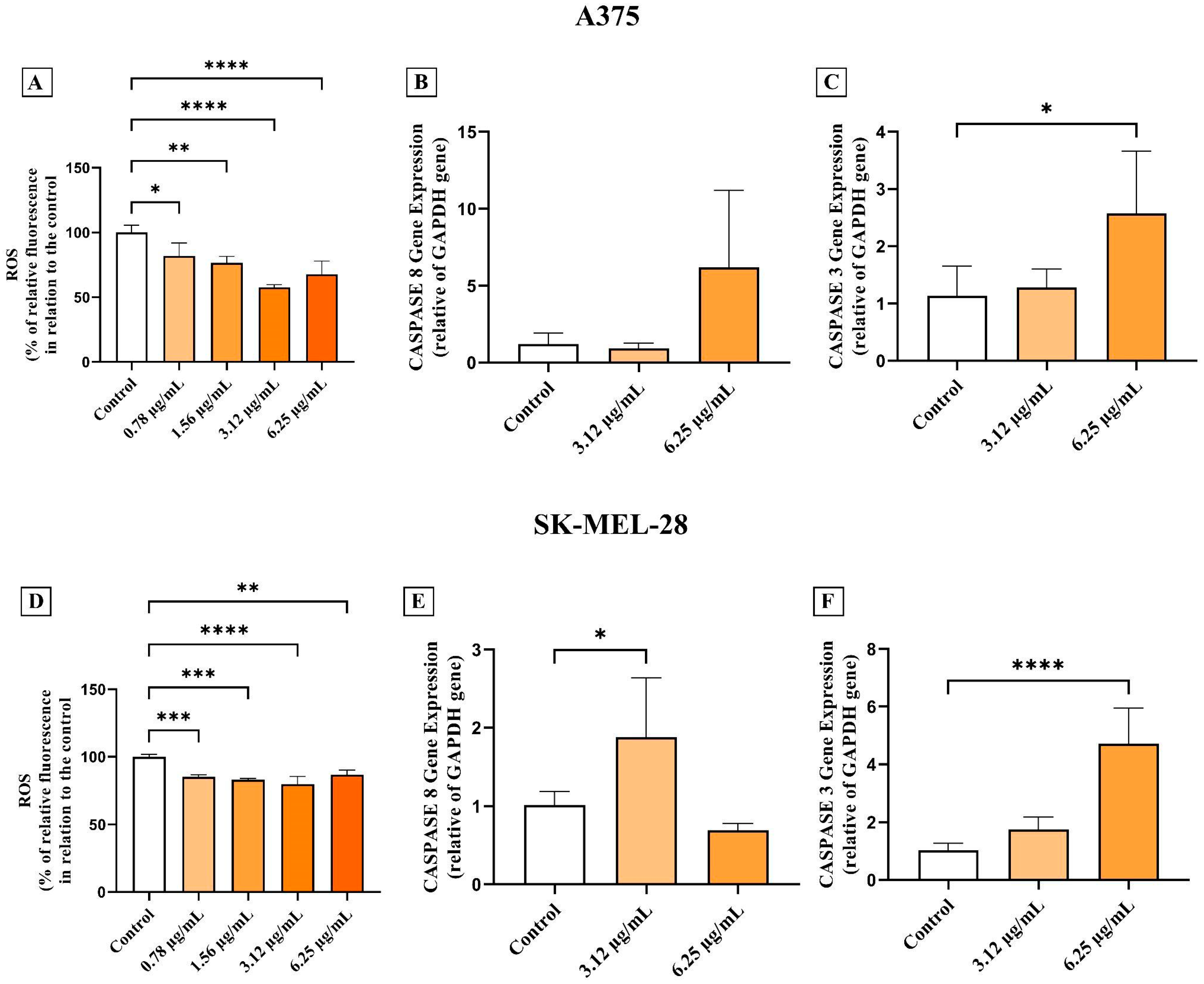

3.2. AC3TM Decreases ROS Levels and Modulates Caspase Expression in CM A375 and SK-MEL-28 Cells

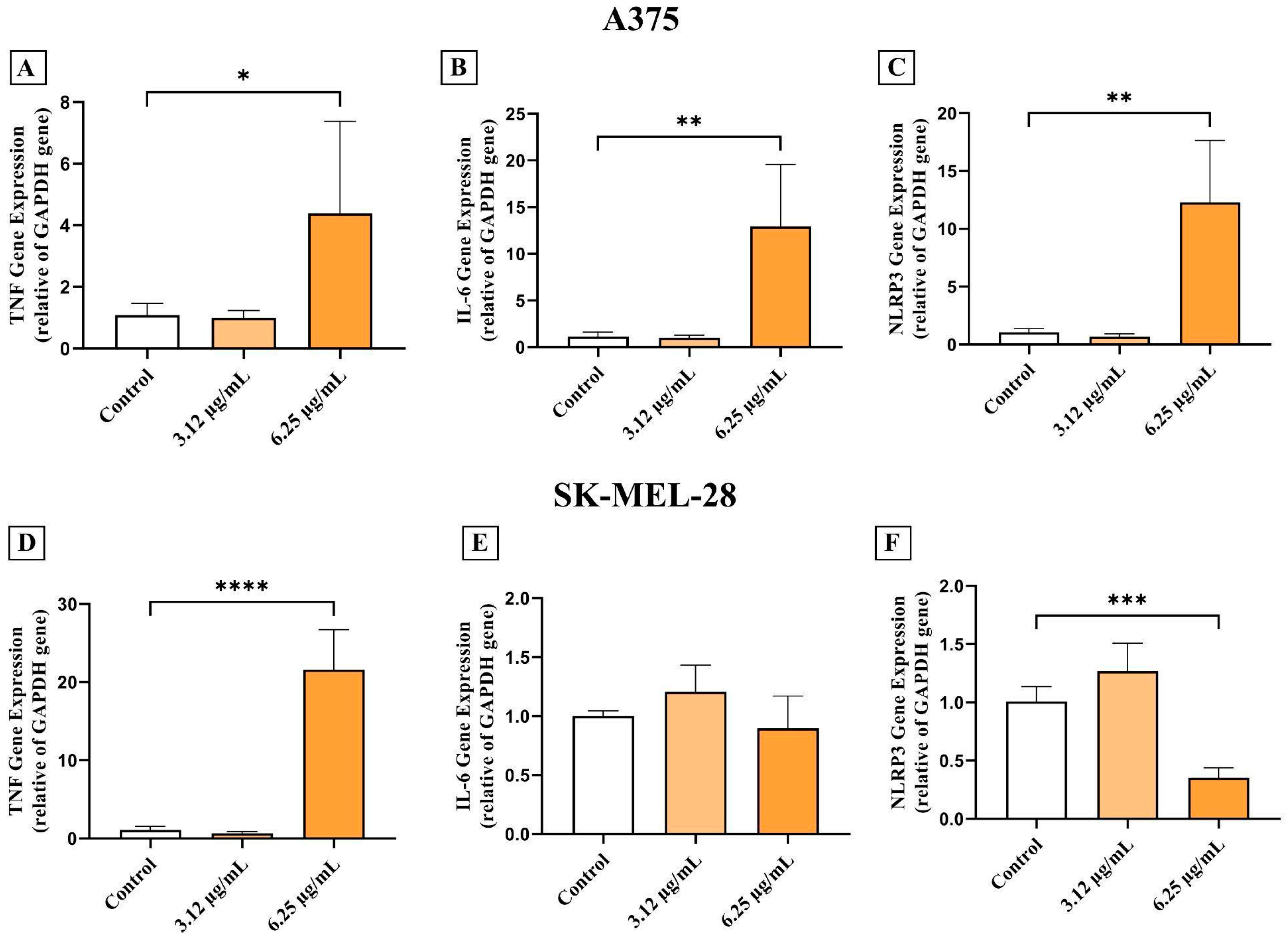

3.3. AC3TM Modulates the Inflammatory Cascade

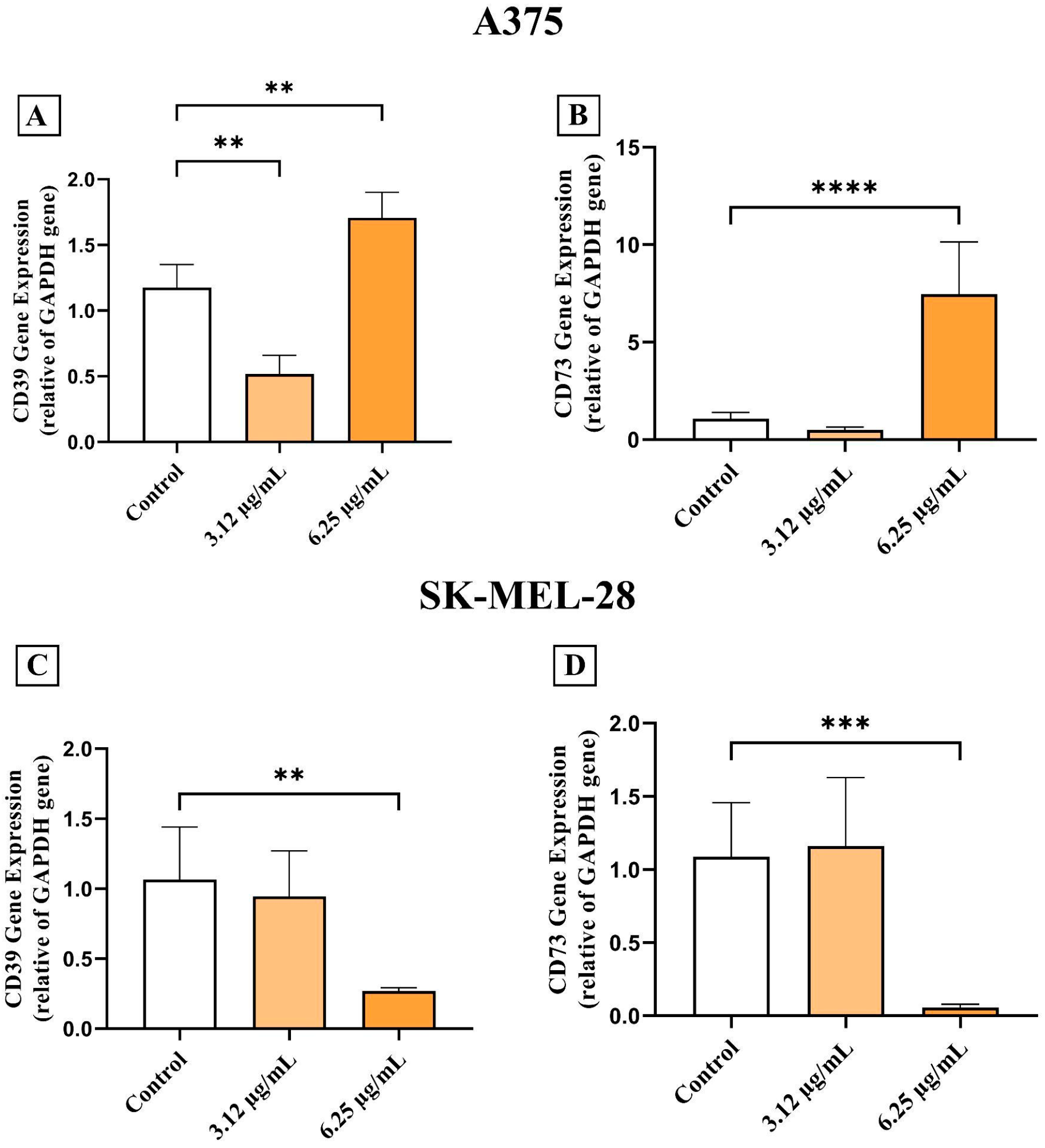

3.4. AC3TM Modulates Gene Expression of CD39 and CD73

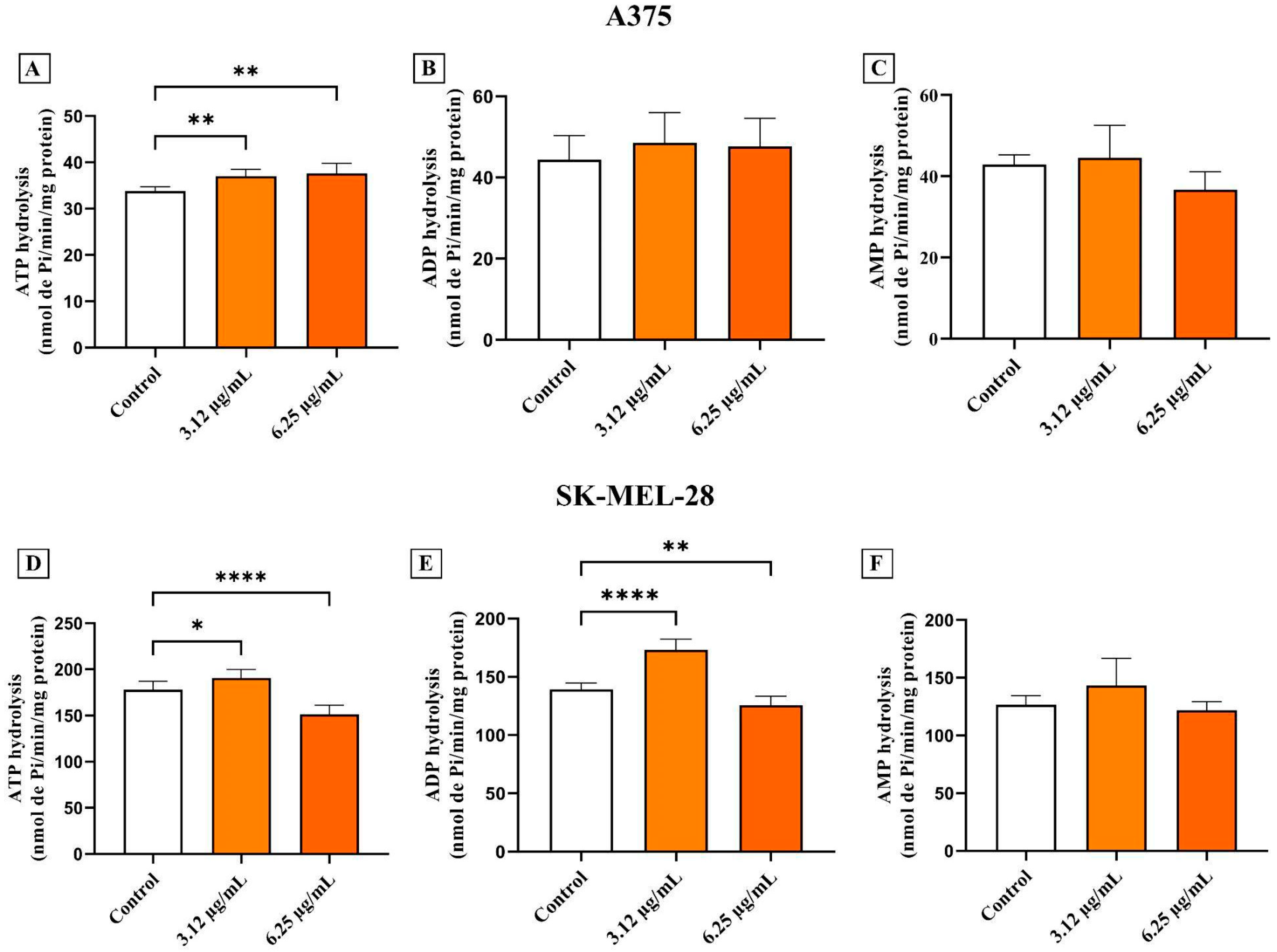

3.5. AC3TM Modulates Enzymatic Activity of CD39 and CD73

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interests

Abbreviations

| CM | Cutaneous melanoma |

| AC3TM | Advanced Curcumin C3 Complex |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| NLRP3 | NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 |

| CD39 | Ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 |

| CD73 | Ecto-5'-nucleotidase |

| CASP-8 | Caspase-8 |

| CASP-3 | Caspase-3 |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| CUR | Curcumin |

| DMC | Demethoxycurcumin |

| BDMC | Bisdemethoxycurcumin |

| BCRJ | Bank of Cell of Rio de Janeiro |

| DMEM | Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide |

| AO | Acridine orange |

| TMRE | Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| ADA | Adenosine deaminase |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| MMP-2 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 |

| MMP-9 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| MAGS | Melanoma Agressiveness Score |

| NF-kB | Nuclear factor-κB |

| DR1/TNFR1 | TNF receptor 1 |

| TRADD | TNFR-associated death domain |

| FADD | Fas-associated death domain |

| TRAIL | Tumor necrosis factor ligand gene |

| anti-PD-1 | Anti-programmed cell death 1 |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| Ado | Adenosine |

| AMP | Adenosine monophosphate |

| DAMP | Danger-Associated Molecular Pattern |

| ICIs | Inhibiting immune checkpoints |

References

- Pan, S.-Y.; Litscher, G.; Gao, S.-H.; Zhou, S.-F.; Yu, Z.-L.; Chen, H.-Q.; Zhang, S.-F.; Tang, M.-K.; Sun, J.-N.; Ko, K.-M. Historical Perspective of Traditional Indigenous Medical Practices: The Current Renaissance and Conservation of Herbal Resources. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014, 2014, 525340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Qu, L.; Yu, W.; Liu, T.; Ning, F.; Li, J.; Guo, X.; Sun, F.; Sun, B.; et al. Potential Implications of Natural Compounds on Aging and Metabolic Regulation. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merenda, T.; Juszczak, F.; Ferier, E.; Duez, P.; Patris, S.; Declèves, A.-É.; Nachtergael, A. Natural Compounds Proposed for the Management of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2024, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzino, S.; Sofia, M.; Mazzone, C.; Litrico, G.; Greco, L.P.; Gallo, L.; La Greca, G.; Latteri, S. Innovative Treatments for Obesity and NAFLD: A Bibliometric Study on Antioxidants, Herbs, Phytochemicals, and Natural Compounds. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Thi, P.-T.; Vo, T.K.; Pham, T.H.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Van Vo, G. Natural Flavonoids as Potential Therapeutics in the Management of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review. 3 Biotech 2024, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Li, S.; Lin, X.; Yang, S.; Zhu, R.; Fu, C.; Zhang, Z. Harnessing Nature’s Pharmacy: Investigating Natural Compounds as Novel Therapeutics for Ulcerative Colitis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1394124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natesan, V.; Kim, S.-J. Natural Compounds in Kidney Disease: Therapeutic Potential and Drug Development. Biomol. Ther. 2025, 33, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Gong, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, D.; Yan, L. The Therapeutic Effect of Natural Compounds on Osteoporosisthrough Ferroptosis. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 2629–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem, M.; Khan, A.; Shah, F.A. Pharmacological Investigation of Natural Compounds for Therapeutic Potential in Neuropathic Pain. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurakova, A.; Koklesova, L.; Samec, M.; Kudela, E.; Kajo, K.; Skuciova, V.; Csizmár, S.H.; Mestanova, V.; Pec, M.; Adamkov, M.; et al. Anti-Breast Cancer Effects of Phytochemicals: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Care. EPMA J. 2022, 13, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsiogianni, M.; Koutsidis, G.; Mavroudis, N.; Trafalis, D.T.; Botaitis, S.; Franco, R.; Zoumpourlis, V.; Amery, T.; Galanis, A.; Pappa, A.; et al. The Role of Isothiocyanates as Cancer Chemo-Preventive, Chemo-Therapeutic and Anti-Melanoma Agents. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagar, A.; Dubey, A.; Sharma, A.; Singh, M. Exploring Promising Natural Compounds for Breast Cancer Treatment: In Silico Molecular Docking Targeting WDR5-MYC Protein Interaction. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asma, S.T.; Acaroz, U.; Imre, K.; Morar, A.; Shah, S.R.A.; Hussain, S.Z.; Arslan-Acaroz, D.; Demirbas, H.; Hajrulai-Musliu, Z.; Istanbullugil, F.R.; et al. Natural Products/Bioactive Compounds as a Source of Anticancer Drugs. Cancers 2022, 14, 6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saberi-Karimian, M.; Katsiki, N.; Caraglia, M.; Boccellino, M.; Majeed, M.; Sahebkar, A. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor: An Important Molecular Target of Curcumin. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juturu, V.; Sahin, K.; Pala, R.; Tuzcu, M.; Ozdemir, O.; Orhan, C.; Sahin, N. Curcumin Prevents Muscle Damage by Regulating NF-kB and Nrf2 Pathways and Improves Performance: An in Vivo Model. J. Inflamm. Res. 2016, Volume 9, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, L.; Ye, H.; Liu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Miao, D.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Jia, Y.; Shen, J.; et al. Nrf2 Is a Key Factor in the Reversal Effect of Curcumin on Multidrug Resistance in the HCT-8/5-Fu Human Colorectal Cancer Cell Line. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, Z.; Sadia, H.; Iqbal, M.J.; Shamas, S.; Malik, K.; Ahmed, R.; Raza, S.; Butnariu, M.; Cruz-Martins, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Apigenin Role as Cell-Signaling Pathways Modulator: Implications in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topçu-Tarladaçalışır, Y.; Sapmaz-Metin, M.; Mercan, Z.; Erçetin, D. Quercetin Attenuates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Apoptosis in TNBS-Induced Colitis by Inhibiting the Glucose Regulatory Protein 78 Activation. Balk. Med. J. 2024, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayad, S.; Wahnou, H.; El Kebbaj, R.; Liagre, B.; Sol, V.; Oudghiri, M.; Saad, E.M.; Duval, R.E.; Limami, Y. The Promise of Piperine in Cancer Chemoprevention. Cancers 2023, 15, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murlimanju, B.V. Neuroprotective Effects of Resveratrol in Alzheimer Rsquo s Disease. Front. Biosci. 2020, 12, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, G.B.; Manica, D.; Da Silva, A.P.; Marafon, F.; Moreno, M.; Bagatini, M.D. Rosmarinic Acid Decreases Viability, Inhibits Migration and Modulates Expression of Apoptosis-Related CASP8/CASP3/NLRP3 Genes in Human Metastatic Melanoma Cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 375, 110427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.-Y.; Hsu, T.-W.; Chen, Y.-R.; Kao, S.-H. Rosmarinic Acid Potentiates Cytotoxicity of Cisplatin against Colorectal Cancer Cells by Enhancing Apoptotic and Ferroptosis. Life 2024, 14, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Thomas, S.G.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Sundaram, C.; Harikumar, K.B.; Sung, B.; Tharakan, S.T.; Misra, K.; Priyadarsini, I.K.; Rajasekharan, K.N.; et al. Biological Activities of Curcumin and Its Analogues (Congeners) Made by Man and Mother Nature. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 76, 1590–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, T.; Gilani, A. Therapeutic Potential of Turmeric in Alzheimer’s Disease: Curcumin or Curcuminoids? Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammon, H.; Wahl, M. Pharmacology of Curcuma Longa. Planta Med. 1991, 57, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.-H.; Lu, P.W.-A.; Lu, E.W.-H.; Lin, C.-W.; Yang, S.-F. Curcumin and Its Analogs and Carriers: Potential Therapeutic Strategies for Human Osteosarcoma. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 1241–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.; Yang, Y.; Cui, L.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Duan, H. Bisdemethoxycurcumin Inhibits Ovarian Cancer via Reducing Oxidative Stress Mediated MMPs Expressions. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandur, S.K.; Pandey, M.K.; Sung, B.; Ahn, K.S.; Murakami, A.; Sethi, G.; Limtrakul, P.; Badmaev, V.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin, Demethoxycurcumin, Bisdemethoxycurcumin, Tetrahydrocurcumin and Turmerones Differentially Regulate Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Proliferative Responses through a ROS-Independent Mechanism. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 1765–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, K.-Y.; Majeed, A.; Ho, C.-T.; Pan, M.-H. Bisdemethoxycurcumin and Curcumin Alleviate Inflammatory Bowel Disease by Maintaining Intestinal Epithelial Integrity and Regulating Gut Microbiota in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 3494–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanawala, S.; Shah, R.; Alluri, K.V.; Somepalli, V.; Vaze, S.; Upadhyay, V. Comparative Bioavailability of Curcuminoids from a Water-Dispersible High Curcuminoid Turmeric Extract against a Generic Turmeric Extract: A Randomized, Cross-over, Comparative, Pharmacokinetic Study. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohankumar, K.; Sridharan, S.; Pajaniradje, S.; Singh, V.K.; Ronsard, L.; Banerjea, A.C.; Somasundaram, D.B.; Coumar, M.S.; Periyasamy, L.; Rajagopalan, R. BDMC-A, an Analog of Curcumin, Inhibits Markers of Invasion, Angiogenesis, and Metastasis in Breast Cancer Cells via NF-κB Pathway—A Comparative Study with Curcumin. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 74, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Lu, H.-F.; Chen, Y.-H.; Chen, J.-C.; Chou, W.-H.; Huang, H.-C. Curcumin, Demethoxycurcumin, and Bisdemethoxycurcumin Induced Caspase-Dependent and –Independent Apoptosis via Smad or Akt Signaling Pathways in HOS Cells. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, C.; Amaral, T.; Peris, K.; Hauschild, A.; Arenberger, P.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Bastholt, L.; Bataille, V.; del Marmol, V.; Dréno, B.; et al. European Consensus-Based Interdisciplinary Guideline for Melanoma. Part 1: Diagnostics: Update 2022. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 170, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarelli, A.; Tucci, M.; Mannavola, F.; Felici, C.; Silvestris, F. The Metabolic Milieu in Melanoma: Role of Immune Suppression by CD73/Adenosine. Tumor Biol. 2019, 41, 101042831983713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carvalho Braga, G.; Coiado, J.V.; De Melo, V.C.; Loureiro, B.B.; Bagatini, M.D. Cutaneous Melanoma and Purinergic Modulation by Phenolic Compounds. Purinergic Signal. 2024, 20, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manica, D.; Da Silva, G.B.; Narzetti, R.A.; Dallagnoll, P.; Da Silva, A.P.; Marafon, F.; Cassol, J.; De Souza Matias, L.; Zamoner, A.; De Oliveira Maciel, S.F.V.; et al. Curcumin Modulates Purinergic Signaling and Inflammatory Response in Cutaneous Metastatic Melanoma Cells. Purinergic Signal. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, I.; Vigano, S.; Faouzi, M.; Treilleux, I.; Michielin, O.; Ménétrier-Caux, C.; Caux, C.; Romero, P.; De Leval, L. CD73 Expression and Clinical Significance in Human Metastatic Melanoma. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 26659–26669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnstock, G.; Di Virgilio, F. Purinergic Signalling and Cancer. Purinergic Signal. 2013, 9, 491–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGahon, A.J.; Martin, S.J.; Bissonnette, R.P.; Mahboubi, A.; Shi, Y.; Mogil, R.J.; Nishioka, W.K.; Green, D.R. Chapter 9 The End of the (Cell) Line: Methods for the Study of Apoptosis in Vitro. In Methods in Cell Biology; Elsevier, 1995; Vol. 46, pp. 153–185 ISBN 978-0-12-564147-0.

- Joshi, D.C.; Bakowska, J.C. Determination of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Reactive Oxygen Species in Live Rat Cortical Neurons. J. Vis. Exp. 2011, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justus, C.R.; Leffler, N.; Ruiz-Echevarria, M.; Yang, L.V. In Vitro Cell Migration and Invasion Assays. J. Vis. Exp. 2014, 51046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manica, D.; Silva, G.B.D.; Silva, A.P.D.; Marafon, F.; Maciel, S.F.V.D.O.; Bagatini, M.D.; Moreno, M. Curcumin Promotes Apoptosis of Human Melanoma Cells by Caspase 3. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2023, 41, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilla, C.; Emanuelli, T.; Frassetto, S.S.; Battastini, A.M.O.; Dias, R.D.; Sarkis, J.J.F. ATP Diphosphohydrolase Activity (Apyrase, EC 3.6.1.5) in Human Blood Platelets. Platelets 1996, 7, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunkes, G.I.; Lunkes, D.; Stefanello, F.; Morsch, A.; Morsch, V.M.; Mazzanti, C.M.; Schetinger, M.R.C. Enzymes That Hydrolyze Adenine Nucleotides in Diabetes and Associated Pathologies. Thromb. Res. 2003, 109, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manica, D.; Da Silva, G.B.; De Lima, J.; Cassol, J.; Dallagnol, P.; Narzetti, R.A.; Moreno, M.; Bagatini, M.D. Caffeine Reduces Viability, Induces Apoptosis, Inhibits Migration and Modulates the CD39/CD73 Axis in Metastatic Cutaneous Melanoma Cells. Purinergic Signal. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Guo, T.; Lin, J.; Huang, X.; Ke, Q.; Wu, Y.; Fang, C.; Hu, C. Curcumin Inhibits the Invasion and Metastasis of Triple Negative Breast Cancer via Hedgehog/Gli1 Signaling Pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 283, 114689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadian, M.; Bahrami, A.; Moradi Binabaj, M.; Asgharzadeh, F.; Ferns, G.A. Molecular Targets of Curcumin and Its Therapeutic Potential for Ovarian Cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 2713–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.-Z.; Liu, T.-D.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J.-X.; Kang, X. The Effect of Curcumin on Cell Adhesion of Human Esophageal Cancer Cell. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Han, X.; Zheng, S.; Li, Z.; Sha, Y.; Ni, J.; Sun, Z.; Qiao, S.; Song, Z. Curcumin Induces Autophagy, Inhibits Proliferation and Invasion by Downregulating AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Human Melanoma Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Yu, T.; Wang, W.; Pan, K.; Shi, D.; Sun, H. Curcumin-Induced Melanoma Cell Death Is Associated with Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore (mPTP) Opening. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 448, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Song, E.; Hu, D.-N.; Chen, M.; Xue, C.; Rosen, R.; McCormick, S.A. Curcumin Induces Cell Death in Human Uveal Melanoma Cells through Mitochondrial Pathway. Curr. Eye Res. 2010, 35, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.-J.; Kim, K.; Kim, C.; Lee, S.-E. Antimelanogenic Effects of Curcumin and Its Dimethoxy Derivatives: Mechanistic Investigation Using B16F10 Melanoma Cells and Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryos. Foods 2023, 12, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-J.; Yang, Z.-X.; Dai, X.-T.; Chen, Y.-F.; Yang, H.-P.; Zhou, X.-D. Bisdemethoxycurcumin Sensitizes Cisplatin-Resistant Lung Cancer Cells to Chemotherapy by Inhibition of CA916798 and PI3K/AKT Signaling. Apoptosis 2017, 22, 1157–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-L.; Chu, Y.L.; Lin, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hsu, M.-J.; Liu, K.-C.; Lai, K.-C.; Huang, A.-C.; Chung, J.-G. Bis Demethoxycurcumin Suppresses Migration and Invasion of Human Cervical Cancer HeLa Cells via Inhibition of NF-ĸB, MMP-2 and -9 Pathways. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 3989–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Cordella, M.; Tabolacci, C.; Nassa, G.; D’Arcangelo, D.; Senatore, C.; Pagnotto, P.; Magliozzi, R.; Salvati, A.; Weisz, A.; et al. TNF-Alpha and Metalloproteases as Key Players in Melanoma Cells Aggressiveness. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunkes, V.L.; Palma, T.V.; Mostardeiro, V.B.; Mastella, M.H.; Assmann, C.E.; Pillat, M.M.; Cruz, I.B.M. da; Morsch, V.M.M.; Chitolina, M.R.; Andrade, C.M. de Curcumin and Vinblastine Induce Apoptosis and Impair Migration in Human Cutaneous Melanoma Cells. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e20511225611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlasa, W.; Supplitt, S.; Drąg-Zalesińska, M.; Przystupski, D.; Kotowski, K.; Szewczyk, A.; Kasperkiewicz, P.; Saczko, J.; Kulbacka, J. Effects of Curcumin Based PDT on the Viability and the Organization of Actin in Melanotic (A375) and Amelanotic Melanoma (C32) – in Vitro Studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 132, 110883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlichting, L.; Valentini, G.; Santos, B.M.; Sanches, M.P.; Soares, R.V.; Saatkamp, R.H.; Kviecinski, M.R.; Zamoner, A.; Parize, A.L. Chitosan/Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose Acetate Succinate Nanoparticles as a Promising Delivery System for Curcumin in MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 429, 127600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocyigit, A.; Guler, E.M. Curcumin Induce DNA Damage and Apoptosis through Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Reducing Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in Melanoma Cancer Cells. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2017, 63, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Xiang, W.; Wang, F.-F.; Wang, R.; Ding, Y. Curcumin Inhibited Growth of Human Melanoma A375 Cells via Inciting Oxidative Stress. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 95, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, Z.; Shukla, Y. Death Receptors: Targets for Cancer Therapy. Exp. Cell Res. 2010, 316, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiraz, Y.; Adan, A.; Kartal Yandim, M.; Baran, Y. Major Apoptotic Mechanisms and Genes Involved in Apoptosis. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 8471–8486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyciakova, S.; Valova, V.; Svitkova, B.; Matuskova, M. Overexpression of TNFα Induces Senescence, Autophagy and Mitochondrial Dysfunctions in Melanoma Cells. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamarsheh, S.; Zeiser, R. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Cancer: A Double-Edged Sword. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deventer, H.W.; Burgents, J.E.; Wu, Q.P.; Woodford, R.-M.T.; Brickey, W.J.; Allen, I.C.; McElvania-Tekippe, E.; Serody, J.S.; Ting, J.P.-Y. The Inflammasome Component Nlrp3 Impairs Antitumor Vaccine by Enhancing the Accumulation of Tumor-Associated Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 10161–10169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.H.; Ellis, L.Z.; Fujita, M. Inflammasomes as Molecular Mediators of Inflammation and Cancer: Potential Role in Melanoma. Cancer Lett. 2012, 314, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhouhesh Far, N.; Hajiheidari Varnousafaderani, M.; Faghihkhorasani, F.; Etemad, S.; Abdulwahid, A.R.R.; Bakhtiarinia, N.; Mousaei, A.; Dortaj, E.; Karimi, S.; Ebrahimi, N.; et al. Breaking the Barriers: Overcoming Cancer Resistance by Targeting the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 182, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegutkin, G.G. Nucleotide- and Nucleoside-Converting Ectoenzymes: Important Modulators of Purinergic Signalling Cascade. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Res. 2008, 1783, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xie, W.; Li, Y.; Ni, Q.; Timashev, P.; Lyu, M.; Xia, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Biomimetic Nanocarriers Guide Extracellular ATP Homeostasis to Remodel Energy Metabolism for Activating Innate and Adaptive Immunity System. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2105376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredholm, B.B.; IJzerman, A.P.; Jacobson, K.A.; Linden, J.; Müller, C.E. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and Classification of Adenosine Receptors—An Update. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boison, D.; Yegutkin, G.G. Adenosine Metabolism: Emerging Concepts for Cancer Therapy. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faas, M.M.; Sáez, T.; De Vos, P. Extracellular ATP and Adenosine: The Yin and Yang in Immune Responses? Mol. Aspects Med. 2017, 55, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Tait, S.W.G. Targeting Immunogenic Cell Death in Cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 2994–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, D.; Young, A.; Teng, M.W.L.; Smyth, M.J. Targeting Immunosuppressive Adenosine in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziogas, D.C.; Theocharopoulos, C.; Koutouratsas, T.; Haanen, J.; Gogas, H. Mechanisms of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Melanoma: What We Have to Overcome? Cancer Treat. Rev. 2023, 113, 102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.; Yin, S.; To, K.K.W.; Fu, L. CD39/CD73/A2AR Pathway and Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, M.; Calaf, G.M. Curcumin Inhibits Invasive Capabilities through Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraulo, C.; Orlando, L.; Morretta, E.; Voli, A.; Plaitano, P.; Cicala, C.; Potaptschuk, E.; Müller, C.E.; Tosco, A.; Monti, M.C.; et al. High Levels of Soluble CD73 Unveil Resistance to BRAF Inhibitors in Melanoma Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 117033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, A.; Gupte, A.A.; Hamilton, D.J. Plumbagin Elicits Cell-Specific Cytotoxic Effects and Metabolic Responses in Melanoma Cells. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, A.; Farshchi, H.K.; Mirzavi, F.; Zamani, P.; Ghaderi, A.; Amini, Y.; Khorrami, S.; Mashayekhi, K.; Jaafari, M.R. The Therapeutic Potential of Targeting CD73 and CD73-Derived Adenosine in Melanoma. Biochimie 2020, 176, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlino, M.S.; Larkin, J.; Long, G.V. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Melanoma. The Lancet 2021, 398, 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.-J.; Rutkowski, P.; Lao, C.D.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Dummer, R.; et al. Five-Year Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, E.; McGlinchey, K.; Wang, J.; Martin, P.; Ching, S.L.K.; Floc’h, N.; Kurasawa, J.; Starrett, J.H.; Lazdun, Y.; Wetzel, L.; et al. Anti–PD-L1 and Anti-CD73 Combination Therapy Promotes T Cell Response to EGFR-Mutated NSCLC. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e142843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | CTCCTCACAGTTGCCATGTA | GTTGAGCACAGGGTACTTTATTG |

| CASP-8 | AGGAGCTGCTCTTCCGAATT | CCCTGCCTGGTGTCTGAAGT |

| CASP-3 | TTTGAGCCTGAGCAGAGACATG | TACCAGTGCGTATGGAGAAATGG |

| TNF-α | CAGGCAGTCAGATCATCTTC | GCTTGAGGGTTTGCTACAAC |

| IL-6 | TCATCCCATAGCCCAGAGCA | CTGGCATTTGTGGTTGGGTC |

| NLRP3 | AACATGCCCAAGGAGGAAGA | GGCTGTTCACCAATCCATGA |

| CD39 | GCCCTGGTCTTCAGTGTATTAG | CTGGCATAACCTACCTACTCTTTC |

| CD73 | GTGCCTTTGATGAGTCAGGTAG | TTCCTTTCTCTCGTGTCCTTTG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).