Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Treatments on Tumor Growth

2.2. Histological and Immunofluorescence Analysis of Tumor Tissues

2.2.1. Regulation of MITF in Response to Treatments

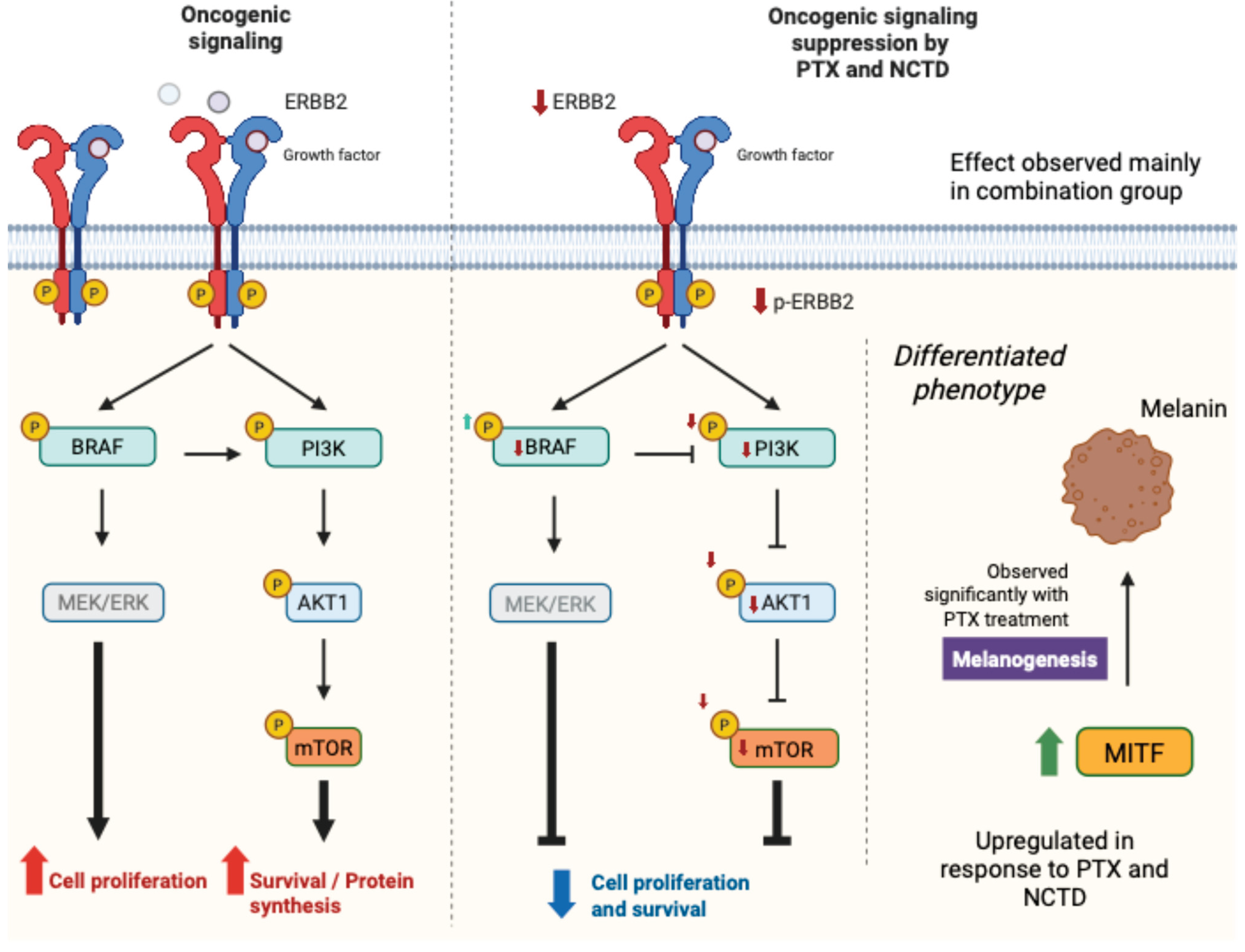

2.2.2. Expression and Activation of Key Oncogenic Signaling Proteins

2.3. Transcriptomic Analysis via RNA-Seq

2.3.1. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

2.3.2. Clustered Gene Expression Patterns

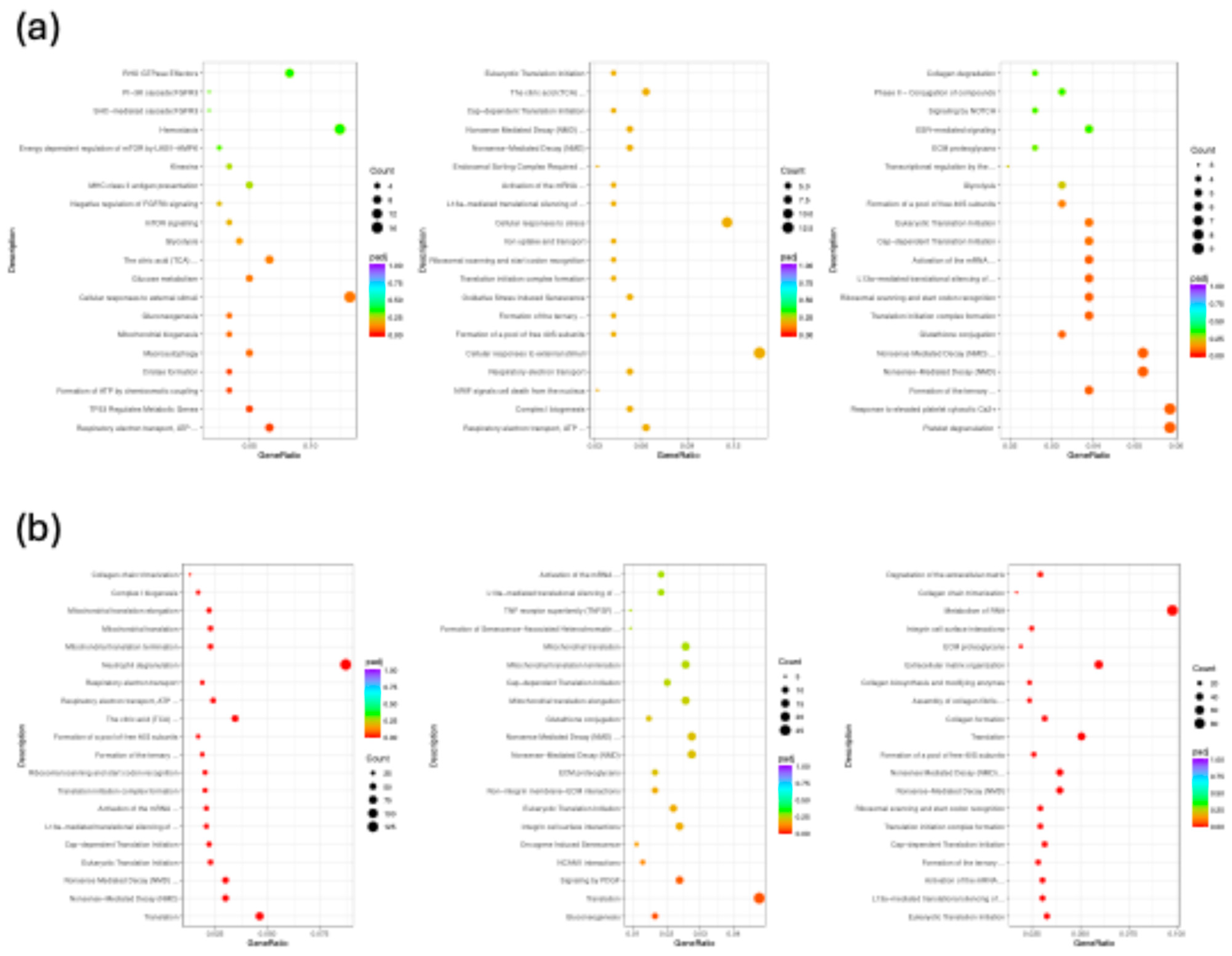

2.3.3. Functional Enrichment and Pathway Analysis

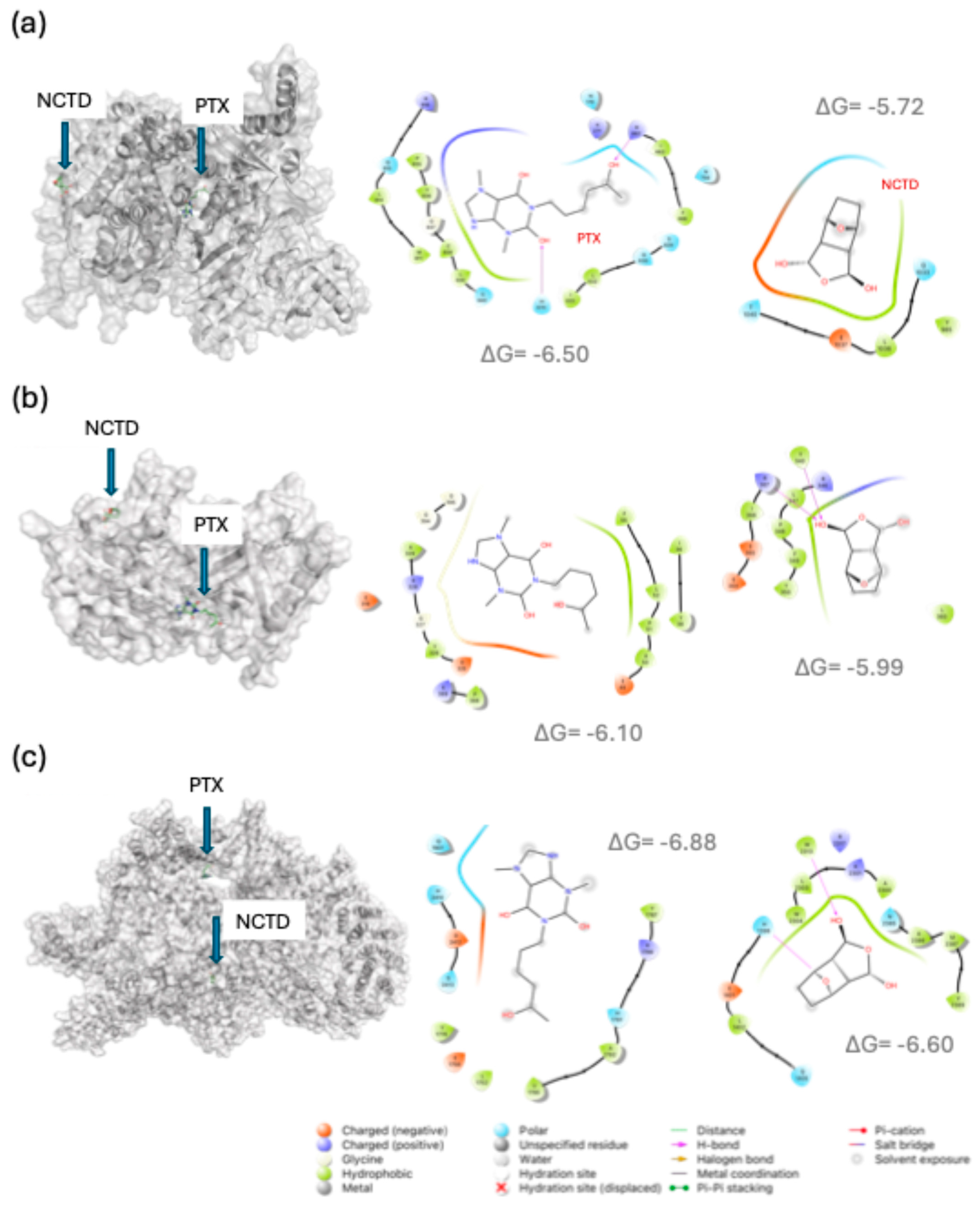

2.4. In Silico Analysis of Drug–Target Interactions

- For B-RAF, PTX showed predicted interactions with Lys483 and Asp594, both essential residues within the ATP-binding site [18], suggesting potential interference with kinase activity.

- For mTOR, PTX docked at residues Gln1901, His2410, and Asp2412, located near the kinase catalytic site [19].

- For PIK3CA (PI3K catalytic subunit alpha), PTX interacted with residues such as His670 and Arg818, known to participate in PI3K activation [20].

- For HIF1A, NCTD showed the strongest binding energy (–7.8 kcal/mol), with interactions at residues Arg383 and His374, both involved in transcriptional regulation under hypoxic conditions [21].

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Establishment of the Murine Melanoma Model

4.3. Pharmacological Treatments

4.4. Total RNA Extraction and cDNA Library Preparation

4.5. RNA Sequencing and Data Acquisition

4.6. RNA-Seq Data Analysis Pipeline

4.7. Tumor Tissue Immunofluorescence

4.8. Molecular Docking Studies

4.9. Statical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDH1 | E-cadherin |

| FZD8 | Frizzled-8 receptor |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| CTNND1 | p120-catenin |

| LFA-1 | CD11a/CD18 integrin complex = ITGAL/ITGB2 |

| CXCL12γ | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12, gamma subunit |

| Claudin-2 | CLDN2 |

| PIK3CA | PI3K catalytic subunit p110α |

| AKT1 | AKT serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| ERK2 | MAPK1 protein |

| CD117 | KIT receptor |

| KITLG | Stem Cell Factor (KIT ligand) |

| KDM5B | histone demethylase |

| MITF | Microphthalmia-associated TF |

| B-RAF | B-Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase |

| ERBB2 | HER2 receptor |

| HIF1A | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha |

| VEGF-A | Vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| TWIST1 | Twist-related protein 1 |

| PTGS2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| PDPK1 | 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 |

| NF-κB | NF-κB complex |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| Reactome | Reactome Pathway Database |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

References

- Schadendorf D, Fisher DE, Garbe C, Gershenwald JE, Grob J-J, Halpern A, et al. Melanoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015;1:15003. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Ma S, Zhu S, Zhu L, Guo W. Advances in Immunotherapy and Targeted Therapy of Malignant Melanoma. Biomedicines 2025;13:225. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Vega I, Vega-López A. Combinational photodynamic and photothermal - based therapies for melanoma in mouse models. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2023;43:103596. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Vega I. Upgrading Melanoma Treatment: Promising Immunotherapies Combinations in the Preclinical Mouse Model. Curr Cancer Ther Rev 2024;20:489–509. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Vega I, Correa-Lara MVM, Vega-López A. Effectiveness of radiotherapy and targeted radionuclide therapy for melanoma in preclinical mouse models: A combination treatments overview. Bull Cancer 2023. [CrossRef]

- Aszalos A, Grimley PM, Balint E, Chadha KC, Ambrus JL. On the mechanism of action of interferons: interaction with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, pentoxifylline (Trental) and cGMP inducers. J Med 1991;22:255–71.

- Inacio MD, Costa MC, Lima TFO, Figueiredo ID, Motta BP, Spolidorio LC, et al. Pentoxifylline mitigates renal glycoxidative stress in obese mice by inhibiting AGE/RAGE signaling and increasing glyoxalase levels. Life Sci 2020;258:118196. [CrossRef]

- Kulcu Cakmak S, Cakmak A, Gonul M, Kilic A, Gul U. Pentoxifylline Use in Dermatology. Inflammation & Allergy-Drug Targets 2012;11:422–32. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J, Ren Y, Tan L, Song X, Wang M, Li Y, et al. Norcantharidin: research advances in pharmaceutical activities and derivatives in recent years. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020;131:110755. [CrossRef]

- Zeng B, Chen X, Zhang L, Gao X, Gui Y. Norcantharidin in cancer therapy – a new approach to overcoming therapeutic resistance: A review. Medicine 2024;103:e37394. [CrossRef]

- Correa-Lara MVM, Lara-Vega I, Nájera-Martínez M, Domínguez-López ML, Reyes-Maldonado E, Vega-López A. Tumor-Infiltrating iNKT Cells Activated through c-Kit/Sca-1 Are Induced by Pentoxifylline, Norcantharidin, and Their Mixtures for Killing Murine Melanoma Cells. Pharmaceuticals 2023;16:1472. [CrossRef]

- González-Quiroz JL, Ocampo-Godínez JM, Hernández-González VN, Lezama RA, Reyes-Maldonado E, Vega-López A, et al. Pentoxifylline and Norcantharidin Modify p62 Expression in 2D and 3D Cultures of B16F1 Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:5140. [CrossRef]

- Chen F, Wang S, Wei Y, Wu J, Huang G, Chen J, et al. Norcantharidin modulates the miR-30a/Metadherin/AKT signaling axis to suppress proliferation and metastasis of stromal tumor cells in giant cell tumor of bone. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018;103:1092–100. [CrossRef]

- Madera-Sandoval RL, Tóvári J, Lövey J, Ranđelović I, Jiménez-Orozco A, Hernández-Chávez VG, et al. Combination of pentoxifylline and α-galactosylceramide with radiotherapy promotes necro-apoptosis and leukocyte infiltration and reduces the mitosis rate in murine melanoma. Acta Histochem 2019;121:680–9. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Razo G, Pires PC, Avilez-Colin A, Domínguez-López ML, Veiga F, Conde-Vázquez E, et al. Evaluation of a Norcantharidin Nanoemulsion Efficacy for Treating B16F1-Induced Melanoma in a Syngeneic Murine Model. Int J Mol Sci 2025;26:1215. [CrossRef]

- Mahdi AF, Ashfield N, Crown J, Collins DM. Pre-Clinical Rationale for Amcenestrant Combinations in HER2+/ER+ Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2025;26. [CrossRef]

- Smith LK, Sheppard KE, McArthur GA. Is resistance to targeted therapy in cancer inevitable? Cancer Cell 2021;39:1047–9. [CrossRef]

- Jabbarzadeh Kaboli P, Ismail P, Ling K-H. Molecular modeling, dynamics simulations, and binding efficiency of berberine derivatives: A new group of RAF inhibitors for cancer treatment. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193941. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Rudge DG, Koos JD, Vaidialingam B, Yang HJ, Pavletich NP. mTOR kinase structure, mechanism and regulation. Nature 2013;497:217–23. [CrossRef]

- Vadas O, Burke JE, Zhang X, Berndt A, Williams RL. Structural Basis for Activation and Inhibition of Class I Phosphoinositide 3-Kinases. Sci Signal 2011;4. [CrossRef]

- McDonough MA, Li V, Flashman E, Chowdhury R, Mohr C, Liénard BMR, et al. Cellular oxygen sensing: Crystal structure of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase (PHD2). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006;103:9814–9. [CrossRef]

- Nájera-Martínez M, Lara-Vega I, Avilez-Alvarado J, Pagadala NS, Dzul-Caamal R, Domínguez-López ML, et al. The Generation of ROS by Exposure to Trihalomethanes Promotes the IκBα/NF-κB/p65 Complex Dissociation in Human Lung Fibroblast. Biomedicines 2024;12:2399. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Wan Y, Huang C. The Biological Functions of NF-kappaB1 (p50) and its Potential as an Anti-Cancer Target. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2009;9:566–71. [CrossRef]

- Anderson MG, Smith RS, Hawes NL, Zabaleta A, Chang B, Wiggs JL, et al. Mutations in genes encoding melanosomal proteins cause pigmentary glaucoma in DBA/2J mice. Nat Genet 2002;30:81–5. [CrossRef]

- Weinzweig J, Tattini C, Lynch S, Zienowicz R, Weinzweig N, Spangenberger A, et al. Investigation of the Growth and Metastasis of Malignant Melanoma in a Murine Model: The Role of Supplemental Vitamin A. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;112:152–8. [CrossRef]

- Overwijk WW, Restifo NP. B16 as a Mouse Model for Human Melanoma. Curr Protoc Immunol 2000;39. [CrossRef]

- Champiat S, Tselikas L, Farhane S, Raoult T, Texier M, Lanoy E, et al. Intratumoral Immunotherapy: From Trial Design to Clinical Practice. Clinical Cancer Research 2021;27:665–79. [CrossRef]

- Levy C, Khaled M, Fisher DE. MITF: master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol Med 2006;12:406–14. [CrossRef]

- Hoek KS, Eichhoff OM, Schlegel NC, Döbbeling U, Kobert N, Schaerer L, et al. In vivo Switching of Human Melanoma Cells between Proliferative and Invasive States. Cancer Res 2008;68:650–6. [CrossRef]

- Ribas A, Flaherty KT. BRAF targeted therapy changes the treatment paradigm in melanoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011;8:426–33. [CrossRef]

- Chamcheu J, Roy T, Uddin M, Banang-Mbeumi S, Chamcheu R-C, Walker A, et al. Role and Therapeutic Targeting of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Skin Cancer: A Review of Current Status and Future Trends on Natural and Synthetic Agents Therapy. Cells 2019;8:803. [CrossRef]

- Rozeman EA, Dekker TJA, Haanen JBAG, Blank CU. Advanced Melanoma: Current Treatment Options, Biomarkers, and Future Perspectives. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018;19:303–17. [CrossRef]

- Marabelle A, Tselikas L, de Baere T, Houot R. Intratumoral immunotherapy: using the tumor as the remedy. Annals of Oncology 2017;28:xii33–43. [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran S, Cheng S, Gajendran N, Shekoohi S, Chesnokova L, Yu X, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of melanoma cells reveals an association of α-synuclein with regulation of the inflammatory response. Sci Rep 2024;14:27140. [CrossRef]

- Yan G, Shi L, Zhang F, Luo M, Zhang G, Liu P, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of mechanism of melanoma cell death induced by photothermal therapy. J Biophotonics 2021;14:e202100034. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Li Z, Luo T, Shi H. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAF/MEK/ERK pathways for cancer therapy. Molecular Biomedicine 2022;3:47. [CrossRef]

- Qi X, Chen Y, Liu S, Liu L, Yu Z, Yin L, et al. Sanguinarine inhibits melanoma invasion and migration by targeting the FAK/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway. Pharm Biol 2023;61:696–709. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira L, Dos Santos R, Oliva G, Andricopulo A. Molecular Docking and Structure-Based Drug Design Strategies. Molecules 2015;20:13384–421. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Vega I, Vega-López A. Molecular Docking Simulations of Protoporphyrin IX, Chlorin e6, and Methylene Blue for Target Proteins of Viruses Causing Skin Lesions: Monkeypox and HSV. Lett Drug Des Discov 2024;21:2939–57. [CrossRef]

- Savoia P, Cremona O, Fava P. New Perspectives in the Pharmacological Treatment of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer. Curr Drug Targets 2016;17:353–74. [CrossRef]

- EUR-Lex. THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes Text with EEA relevance. Official Journal of the European Union 2010:33–79.

- Martínez-Razo G, Domínguez-López ML, de la Rosa JM, Fabila-Bustos DA, Reyes-Maldonado E, Conde-Vázquez E, et al. Norcantharidin toxicity profile: an in vivo murine study. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2023;396:99–108. [CrossRef]

- Tomayko MM, Reynolds CP. Determination of subcutaneous tumor size in athymic (nude) mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1989;24:148–54. [CrossRef]

- Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data 2010.

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014;30:2114–20. [CrossRef]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013;29:15–21. [CrossRef]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15:550. [CrossRef]

- Yu G, Wang L-G, Han Y, He Q-Y. clusterProfiler: an R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS 2012;16:284–7. [CrossRef]

- R Foundation for Statistical Computing VAustria. R: A language and environment for statistical ## computing. 2021.

- Posit Team / Software PBMA. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. 2025.

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 2012;9:671–5. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J, He S, et al. PubChem 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2025;53:D1516–25. [CrossRef]

- Berman HM. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 2000;28:235–42. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Vega I, Vega-López A. Mapping immunogenic epitopes of F13L protein in Mpox Clade Ib: HLA-B*08 and HLA-DRB1*01 as predictors of antigen presentation, disease incidence, and lethality. Gene Rep 2025;40:102232. [CrossRef]

| Protein | PDB ID | Ligand | Binding Energy (ΔG, kcal mol-1) | Binding site / Residues |

| Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) | ||||

| CDH1 | 3Q2V | NCTD | -4.76 | Tyr175, Asp168. Leu167 |

| PTX | -4.96 | Met193, Glu190, His180 | ||

| LIM domain-binding protein 1 | 6PTL | NCTD | -5.47 | Gln125, Gly144, Glu143 |

| PTX | -5.23 | Ile165, Phe72, Ile70, Met128, Tyr91, Ile95, Ser94, His132 | ||

| FZD8 | 1IJY | NCTD | -6.16 | Gly113, Val114, Cys115, Val109, Pro108, Lys77 |

| PTX | -6.44 | Ser78, Cys115, Gly113, Lys77, Pro108, Lys74, Val109 | ||

| TGF-β1 | 1KLC | NCTD | -4.79 | Arg25, Lys37, Phe24, His34 |

| PTX | -5.00 | Arg25, Phe24, His34 | ||

| CTNND1 | 3L6X | NCTD | -5.52 | Asp510, Arg383 |

| PTX | -5.20 | Lue620, Glu521, Arg326, Arg329, Val514, Asn517 | ||

| LFA-1 | 3F74 | NCTD | -4.91 | Gly262, Leu289, Ile288, Asp290 |

| PTX | -5.06 | Thr164, Tyr166, Ser165, Thr231, Gly128 | ||

| CXCL12γ | 6EHZ | NCTD | -5.11 | Arg12, Cys50, Val49 |

| PTX | -5.06 | Arg12, Cys50, Arg47, Val39, Gln46 | ||

| Claudin-2 | 4YYX | NCTD | -6.18 | Ile38, Ile36, Gly35, Phe34, Leu95, Arg96 |

| PTX | -6.47 | Asn72, Arg74, Glu51, His46, Gly40, Val55 | ||

| Cell Proliferation | ||||

| PIK3CA | 4A55 | NCTD | -5.72 | Gln1033, Leu1036, Glu1037, Thr1040 |

| PTX | -6.50 | His670, Arg662, Asn170, Arg818, Cys838, Leu839 | ||

| AKT1 | 3O96 | NCTD | -5.99 | Leu360, Tyr340, Arg367, Arg346, Leu347, Pro358, Phe349, Tyr350 |

| PTX | -6.10 | Leu52, Pro51, Asp325, Gly327 | ||

| mTOR | 6BCX | NCTD | -6.60 | His1398, Trp2313, Trp2304, Ala2386 |

| PTX | -6.88 | Gln1901, His2410, Asp2412 | ||

| ERK2 | 6GJD | NCTD | -6.60 | Val39, Lys54, Thr105 |

| PTX | -6.70 | Leu156, Lys54, Ala52, Ile31, Ile86 | ||

| Melanoma Stem Cell Marker | ||||

| CD117 | 1PKG | NCTD | -6.62 | Ala621, Cys809, Leu799, Lys623, Thr670, Val603 |

| PTX | -7.40 | Ala597, Asp810, Asp677, Cys809, Gly596, Leu799, Lys623, Thr6670, Val603 | ||

| CD117 (Extracellular domain) | 2EC8 | NCTD | -4.90 | Gln346, Pro343 |

| PTX | -5.24 | Glu228, Glu368, Leu222, Leu223, Lys342, Thr230, Thr342 | ||

| KITLG | 1EXZ | NCTD | -5.56 | Ala147, Arg13, Gly151, Tyr150, Val73, Val170 |

| PTX | -6.01 | Ala147, Arg13, Arg14, Ile152, Ser11, Thr71 | ||

| KDM5B | 5A3P | NCTD | -6.52 | Leu716, Met701, Phe700 |

| PTX | -5.57 | Asp77, Leu81, Phe438, Pro439, Val440 | ||

| Key Drivers of Melanocytic Transformation | ||||

| MITF | 4ATK | NCTD | -4.66 | Asp252 |

| PTX | -5.53 | Ala249, Lys233, Met239, Pro232, Tyr253 | ||

| B-RAF | 4MNF | NCTD | -6.22 | Cys532, Phe583, Trp531 |

| PTX | -7.44 | Lys483, Ala481, Asp594, Gly466, Lau514, Phe583, Thr529 | ||

| RAF-MEK1 complex | 4MNE | NCTD | -6.34 | Leu74, Leu197, Met146 |

| PTX | -7.33 | Asp208, Gly210, Lys97, Met219, Leu215, Phe209 | ||

| ERBB2 | 2A91 | NCTD | -6.01 | Pro279, Phe270, Ans467 |

| PTX | -6.73 | Asn467, Gly443, Leu28, Tyr280, Val4 | ||

| NRAS GTPase | 6E6H | NCTD | -5.91 | Asp13, Gly15, Lys16, Ser17, Val14 |

| PTX | -6.61 | Asp13, Ala18, Ala146, Lys117, Lys147, Phe28, Ser17 | ||

| Vascularization and Angiogenesis | ||||

| HIF1A | 3HQR | NCTD | -7.83 | Arg383, Ile327, His374, Thr387, Val376 |

| PTX | -6.34 | Arg322, Ile251, Leu240, Tyr310, Val241, Val314 | ||

| VEGF-A | 2VPF | NCTD | -4.53 | Ile46, Phe36, Phe47 |

| PTX | -4.74 | Asp63, Cys61, Cys68, Glu64, Lys107 | ||

| EGF | 1IVO | NCTD | -3.51 | Lys48 |

| PTX | -4.43 | Gly36, Trp49, Trp50 | ||

| TWIST1 | 2MVJ | NCTD | -4.01 | Ala9 |

| PTX | -4.04 | Ala6, Ala9, Gly89, Lys10, Ser11 | ||

| PDPK1 | 1H1W | NCTD | -6.51 | Phe93, ser94, Val127 |

| PTX | -6.41 | Glu130, Lys111, Lys123, Leu113, Ser94 | ||

| PTGS2 | 1PXX | NCTD | -6.13 | Val291 |

| PTX | -7.33 | Arg44, Leu152, Lys468 | ||

| Matrix metalloproteinase-1 | 966C | NCTD | -5.90 | Thr241, Val246 |

| PTX | -5.53 | Arg214, Asn205, Asn211, his132, his213, Lys136 | ||

| Matrix metalloproteinase-2 | 1QIB | NCTD | -6.53 | Leu218, Thr227, Tyr223 |

| PTX | -6.83 | Leu164, Tyr223, Val198 | ||

| Matrix metalloproteinase-9 | 5UE3 | NCTD | -6.54 | Arg249, His228, Leu222, Leu243, Tyr248 |

| PTX | -7.02 | Arg249, His257, Leu243, Thr251 | ||

| NF-κB(p50 subunit) | 1SVC | NCTD | -5.42 | Lys147 |

| PTX | -5.34 | Lys147, Phe151, Thr205, Val150 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).