Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

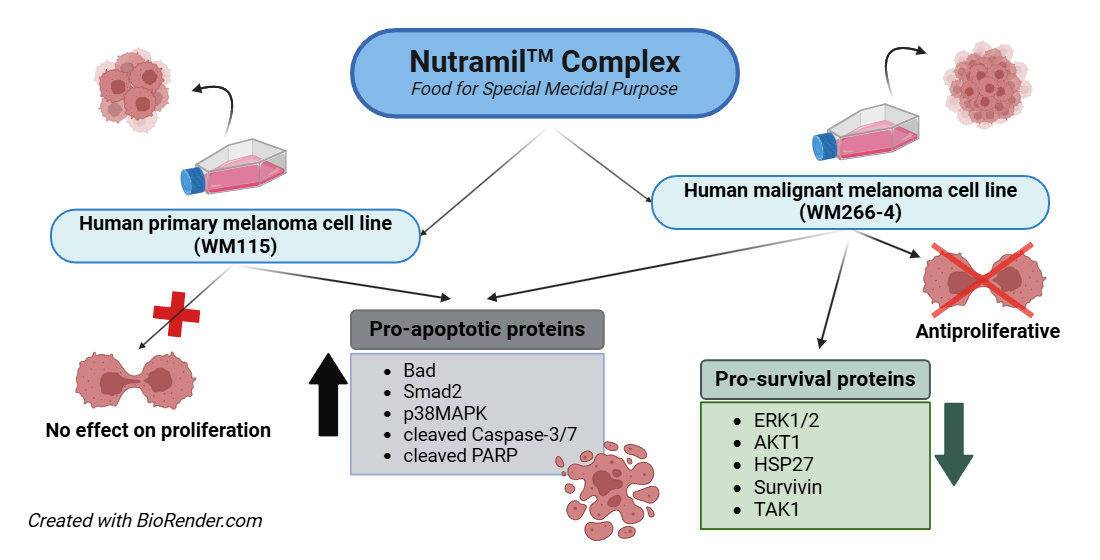

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Testing Material

2.2. Cell Cultures and Treatments

2.3. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.4. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.5. RNA Isolation, RT Reaction and Real-Time PCR Analysis

2.6. Stress and Apoptosis Signaling Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

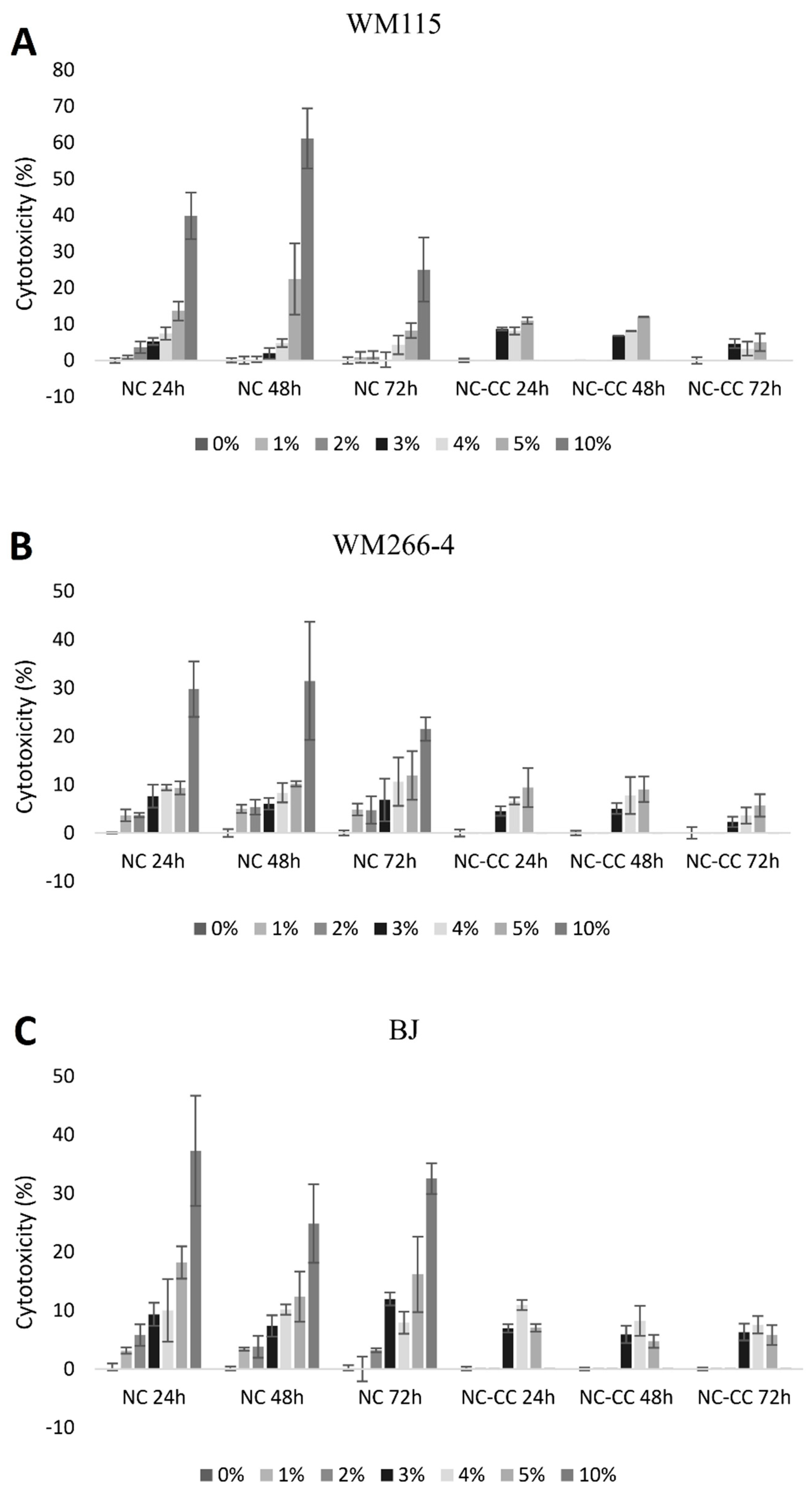

3.1. Cytotoxicity

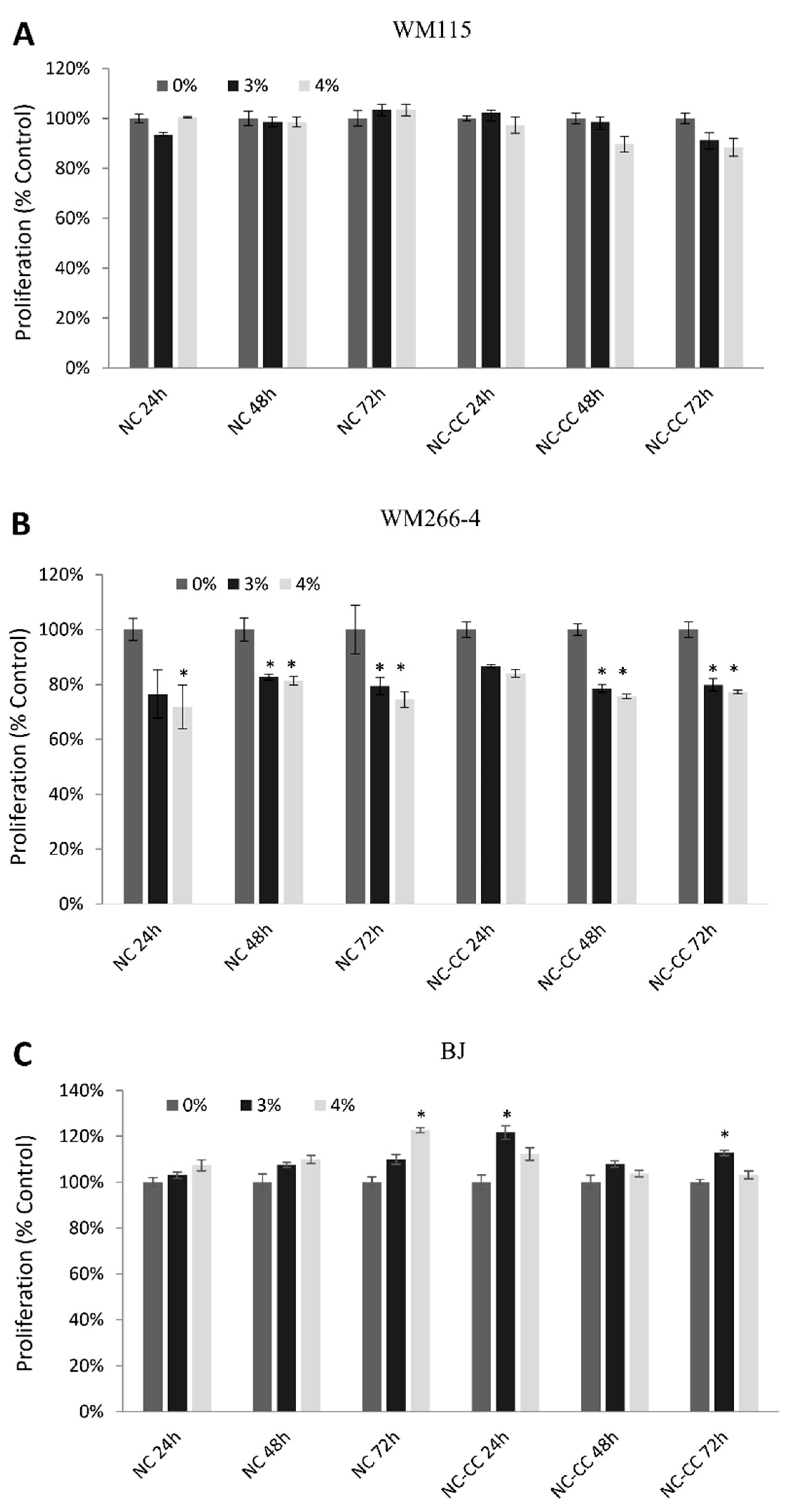

3.2. Cell Proliferation

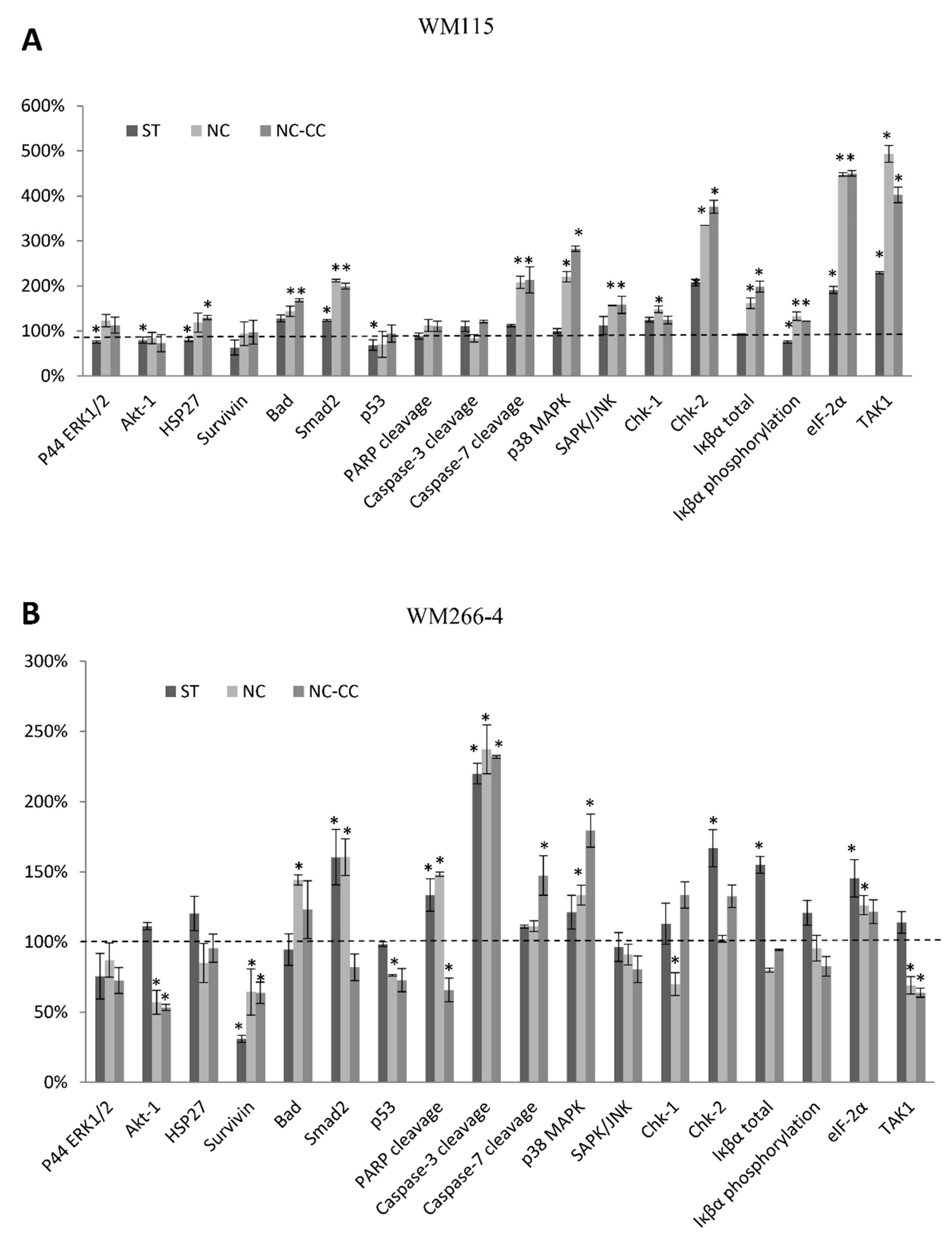

3.4. Expression of Proteins Involved in Cellular Stress and Apoptosis Signalling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomatarm I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Indicence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;71:209-249. [CrossRef]

- Globocan 2022 Global Cancer Observatory. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/16-melanoma-of-skin-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:7-33. [CrossRef]

- Tong LX, Young LC. Nutrition: the future of melanoma prevention? J Am Aca. Dermatol. 2014;71:151-160. [CrossRef]

- Koronowicz AA, Drozdowska M, Wielgos B, Piasna-Słupecka E, Domagała D, Dulińska-Litewka J, Leszczyńska T. The effect of “NutramilTM Complex”, food for special medical purpose, on breast and prostate carcinoma cells. PLOS ONE 2018;13: e0192860. [CrossRef]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001;25:402-408. [CrossRef]

- Yang K, Fung TT, Nan H. An Epidemiological Review of Diet and Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27:1115-1122. [CrossRef]

- Eberle J, Kurbanov BM, Hossini AM, Trefzer U, Fecker LF. Overcoming apoptosis deficiency of melanoma-hope for new therapeutic approaches. Drug Resist Updat. 2007;10: 218-234. [CrossRef]

- Master A, Nauman A. Molecular mechanisms of protein biosynthesis initiation-biochemical and biomedical implications of a new model of translation enhanced by the RNA hypoxia response element (rHRE). Postepy Biochem. 2014;60:39-54.

- McConkey DJ, Zhu K. Mechanisms of proteasome inhibitor action and resistance in cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 2008;11:164-179. [CrossRef]

- Cichorek M, Kozłowska K, Wachulska M, Zielińska K. Spontaneous apoptosis of melanotic and amelanotic melanoma cells in different phases of cell cycle: relation to tumor growth. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2006;44: 31-36.

- Pokrywka M, Litynska A. Targeting the melanoma. Postepy Biol. Komorki 2012;39:3-24.

- Blokx WA, van Dijk MC, Ruiter DJ. Molecular cytogenetics of cutaneous melanocytic lesions - diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic aspects. Histopathology. 2010;56:121-132. [CrossRef]

- Gray-Schopfer V, Wellbrock C, Marais R. Melanoma biology and new targeted therapy. Nature 2007;445:851-857. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan RJ, Atkins MB. Molecular-targeted therapy in malignant melanoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:567-581. [CrossRef]

- Sidor-Kaczmarek J, Cichorek M, Spodnik JH, Wójcik S, Moryś J. Proteasome inhibitors against amelanotic melanoma. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2017;33:557-573. [CrossRef]

- Parcellier A, Brunet M, Schmitt E, Col E, Didelot C, Hammann A, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI, Khochbin S, Solary E, Garrido C. HSP27 favors ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of p27Kip1 and helps S-phase re-entry in stressed cells. FASEB J. 2006;20:1179-1181. [CrossRef]

- Okada M, Matsuzawa A, Yoshimura A, Ichijo H. The lysosome rupture-activated TAK1-JNK pathway regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Biol Chem. 2014; 289:32926-32936. [CrossRef]

- Dahl C, Guldberg P. The genome and epigenome of malignant melanoma. APMIS 2007;115:1161-1176. [CrossRef]

- Yajima I, Kumasaka MY, Thang ND, Goto Y, Takeda K, Yamanoshita O, Iida M, Ohgami N, Tamura H, Kawamoto Y, Kato M. RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/AKT Signaling in Malignant Melanoma Progression and Therapy. Dermatol Res Pract 2012;2012. [CrossRef]

- Krześlak A. Akt kinase: a key regulator of metabolism and progression of tumors. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2010;64:490-503.

- Koronowicz AA, Banks P, Domagała D, Master A, Leszczyńska T, Piasna E, Marynowska M, Laidler P. Fatty acid extract from CLA-enriched egg yolks can mediate transcriptome reprogramming of MCF-7 cancer cells to prevent their growth and proliferation. Genes Nutr 2016;11:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Jochemsen AG. Reactivation of p53 as therapeutic intervention for malignant melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2014;26:114-119. [CrossRef]

- Kyrgidis A, Tzellos TG, Triaridis, S. Melanoma: Stem cells, sun exposure and hallmarks for carcinogenesis, molecular concepts and future clinical implications. J Carcinog. 2010;9:3. [CrossRef]

- Ko JM, Velez NF, Tsao H. Pathways to melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29: 210-217. [CrossRef]

- Wheatley SP, McNeish IA. Survivin: a protein with dual roles in mitosis and apoptosis. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;247:35-88. [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll L, Linehan R, Clynes M. Survivin: role in normal cells and in pathological conditions. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2003;3:131-152. [CrossRef]

- Tamm I, Wang Y, Sausville E, Scudiero DA, Vigna N, Oltersdorf T, Reed JC. IAP-family protein survivin inhibits caspase activity and apoptosis induced by Fas (CD95), Bax, caspases, and anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5315-5320.

- Ikeguchi M, Hirooka Y, Kaibara N. Quantitative analysis of apoptosis-related gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:1938-1945. [CrossRef]

- Grossman D, Altieri DC. Drug resistance in melanoma: mechanisms, apoptosis, and new potential therapeutic targets. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2001;20:3-11. [CrossRef]

- Gradilone A, Gazzaniga P, Ribuffo D, Scarpa S, Cigna E, Vasaturo F, Bottoni U, Innocenzi D, Calvieri S, Scuderi N, Frati L, Aglianò AM. Survivin, bcl-2, bax, and bcl-X gene expression in sentinel lymph nodes from melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:306-312. [CrossRef]

| Gene Symbol |

WM-115 | WM266-4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC vs UC | NC-CC vs UC | NC vs UC | NC-CC vs UC | |||||

| FC value | Adjusted p-values |

FC value | Adjusted p-values |

FC value | Adjusted p-values |

FC value | Adjusted p-values |

|

| Pro-apoptotic genes | ||||||||

| APAF1 | ↑4,52* | 1,1E-07 | ↑4,73* | 0,00003 | ↓-4,56* | 0,00001 | ↓-2,69* | 0,00010 |

| BAD | ↑1,59* | 0,01212 | ↑1,25* | 0,00007 | ↑6,20* | 0,01623 | ↑3,62* | 0,00128 |

| BAX | ↑1,37* | 0,00064 | 1,44 | 0,07656 | ↑2,12* | 0,00005 | 1,29 | 0,05086 |

| BID | ↑1,78* | 0,02290 | ↑1,25* | 0,00552 | ↑2,58* | 0,00013 | 1,74 | 0,12706 |

| CASP3 | ↑2,42* | 0,00017 | ↑2,79* | 5,0E-07 | ↑4,00* | 0,00017 | ↑3,27* | 0,00005 |

| CASP8 | ↑4,01* | 0,00015 | ↑5,53* | 0,00007 | ↓-1,55* | 0,00001 | ↓-2,28* | 0,00013 |

| CASP9 | ↑2,91* | 0,00148 | ↑1,40* | 0,00752 | ↑4,80* | 0,00148 | ↑2,93* | 0,00007 |

| CYCS | ↑1,73* | 0,03390 | ↑1,48* | 0,00641 | ↓-2,06* | 0,00295 | ↓-2,76* | 0,00006 |

| FADD | 1,20 | 0,08572 | ↑1,47* | 0,01262 | ↑3,16* | 0,00008 | 1,87 | 0,163556 |

| FAS | 1,01 | 0,3740 | ↑1,12* | 2,80E-05 | 1,12 | 0,37390 | ↑1,34* | 0,00006 |

| TP53 | 1,02 | 0,09595 | ↑1,49* | 0,02467 | ↑1,72* | 0,00001 | 1,28 | 0,06596 |

| Pro-survival genes | ||||||||

| AKT1 | 1,05 | 0,28798 | 1,18 | 0,12187 | ↓-1,97* | 0,00014 | ↓-1,42* | 0,02336 |

| BCL2 | -1,36 | 0,19346 | ↓-1,37* | 0,00859 | ↓-1,57* | 0,00022 | ↓-2,53* | 0,00023 |

| HRAS | ↓-1,82* | 0,02360 | -1,69 | 0,51894 | ↓-2,38* | 0,00033 | ↓-1,64* | 0,00358 |

| IGF1 | ↓-3,04* | 0,04336 | 1,01 | 0,11020 | ↓-7,70* | 0,00003 | -2,16 | 0,08021 |

| IGF1R | ↑1,56* | 0,00003 | ↑1,27* | 0,00040 | -2,01 | 0,43357 | ↓-1,43* | 0,00005 |

| KRAS | ↓-2,28* | 0,00004 | ↓-1,18* | 0,00008 | ↓-2,67* | 0,00004 | ↓-3,29* | 0,00009 |

| MYC | ↓-2,55* | 0,00366 | ↑1,12* | 0,00006 | ↓-1,10* | 0,00006 | ↓-1,23* | 0,03746 |

| NRAS | ↑1,16* | 0,00015 | ↑1,18* | 0,00018 | -3,43* | 0,00001 | ↓-3,70* | 0,00001 |

| RRAS | ↑1,34* | 0,01637 | -1,60 | 0,60253 | ↑1,17* | 0,00007 | -1,15 | 0,05788 |

| YWHA family genes | ||||||||

| YWHAB | ↓-2,27* | 0,00027 | ↑1,04* | 0,00038 | ↓-2,46* | 0,00001 | ↓-1,27* | 0,00014 |

| YWHAE | ↓-1,57* | 0,00001 | ↓-1,29* | 0,00003 | ↓-2,92* | 0,00001 | ↓-3,86* | 0,00001 |

| YWHAG | ↓-1,85* | 0,01506 | ↓-1,29* | 0,00280 | ↓-1,08* | 0,00008 | ↓-1,56* | 0,00496 |

| YWHAH | ↓-1,73* | 0,00376 | ↓-1,38* | 0,00007 | ↓-1,88* | 0,00009 | ↓-1,55* | 0,00754 |

| YWHAQ | 1,01 | 0,10424 | ↓-1,10* | 0,00007 | ↓-2,35* | 0,00001 | ↓-4,10* | 0,00001 |

| YWHAZ | ↓-1,10* | 0,00029 | ↑1,10* | 0,00081 | ↓-2,38* | 0,00002 | ↓-4,10* | 0,00082 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).