1. Introduction

Skin cancer is the most prevalent form of cancers worldwide and it is expected to overtake heart diseases as the leading cause of death in the coming decades [

1]. It was reported that 97,160 new cases of skin cancer were diagnosed in the United States in 2023, which account for 5% of all cancer cases. Moreover, 7990 Americans lost their lives due to skin malignancies [

2]. Depending on the cell type from which the disease evolved, skin cancer is classified as melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. Melanoma is a malignant tumor derived from the melanin-producing cells, the melanocytes. According to its origin, melanoma can be classified into cutaneous and non-cutaneous (uveal and mucosal) [

3]. Cutaneous melanoma (CM) is the most aggressive and fatal malignancy among other skin cancers and its incidence has risen steadily in recent decades around the world. This rapid increase is associated with significant death rate and high health care costs. In 2020, CM accounted for about 325,000 (1.7%) cases of all diagnosed malignant cancers worldwide, with approximately 57,000 related fatalities [

4]. Although melanoma is curable at early stages via surgical removal, advanced metastatic melanomas can be challenging to treat and often resistant to therapies. Until few years ago, advanced stages of the disease were exclusively treated with traditional chemotherapy (temozolomide and dacarbazine) and immunotherapy (interleukin-2, and interferon α-2b,) [

5]. Several challenges have been associated with the above treatments, such as poor response, rapid relapse, drug toxicity, adverse side effects, and unaffordable healthcare costs [

6]. Therefore, searching for a new efficient therapeutic modality has drawn a lot of attention.

Estradiol (also known as 17β-estradiol) is the predominant and most active endogenous type of estrogens that regulates the function of reproductive organs in both sexes [

7]. Moreover, E2 plays an important role in the growth and differentiation of normal tissues as well as different types of neoplasms, like breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, lung, kidney, pancreas, colon, brain, adrenals, and bone by binding to two specific estrogen receptors (ERs): ERα and ERβ which are members of the nuclear steroid hormone receptor superfamily [

3].

Although controversial data were documented about the influence of E2 on CM, many researchers highlighted its ability to suppress tumor progression either through activation of ERβ or by receptor-independent mechanisms. In 2015, Marzagalli

et al. reported that ERβ (but not ERα) is expressed in four types of melanoma cell lines (BLM, WM115, A375, WM1552) that have various genetic mutations, and it exhibits antitumor effects in BLM (NRAS-mutant) and WM115 (BRAF V600D-mutant) cells [

8]. Therefore, hormone-related therapy has been taken into account as a promising strategy for CM treatment; it encouraged researchers to examine both endogenous and exogenous estrogens as potential drugs.

G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) is another important type of ERs. It is a member of G protein-coupled receptor family which mediates rapid non-genomic effects of E2. GPER is widely expressed in numerous tissues like reproductive, nervous, bone, adipose and digestive tissues [

9]. Activation of GPER by its specific ligand (E2) triggers several intracellular pathways such as activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC), MAPK, PI3K/Akt and trans-activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Recently, numerous studies [

10,

11] have been carried out to investigate the role of GPER activation in the development of different cancer types, mainly breast, ovarian, endometrial, and prostate cancers. Controversial results suggested that the effect of GPER varies according to tumor type, site, stage and environment [

12]. In addition to E2, which is the main endogenous ligand for GPER with binding affinity of about 3-6 nM, a number of GPER ligands with either agonistic or antagonistic effects were identified [

13]. These include other forms of estrogens such as 17-α estradiol, estrone, estriol (E3), and other compounds [

14]. The presence of selective pharmacological ligands (agonists or antagonists that bind GPER, but not ER α/β) was fundamental to clarify the physiological role of GPER. In 2006, the first GPER selective agonist, G-1 was identified [

15]. It has a stronger binding affinity for GPER than E2 and it was widely used by researchers to examine the biological effects of GPER in health and disease states and to discover new potential ligands. Subsequently, the two GPER selective antagonists, G15 and G36 were synthesized in 2009 and 2011, respectively [

16].

Phytoestrogens are secondary metabolites produced by plants under environmental stresses and can be classified into two main groups, flavonoids (isoflavones, coumestans, and prenyl flavonoids) and non-flavonoids (mainly lignans). Due to their structural similarity with E2, phytoestrogens can interact with ERs (both classical and GPER) and exert both estrogenic and/or anti-estrogenic effects [

17]. Flavonoids are natural polyphenolic compounds present in certain fruits and vegetables [

18]. Quercetin (3, 3′, 4′, 5, 7-pentahydroxyflavone) is the main flavonoid in human diet and characterized by the presence of five hydroxyl groups (-OH) that are found on C6-C3-C6 backbone structure, especially a 3-OH group on the pyran ring [

19,

20]. Quercetin acts as an anticancer agent by several mechanisms, such as cell cycle arrest, inhibition of MAPKs and Akt pathways, preventing cell proliferation as well as apoptosis induction [

21,

22]. It was demonstrated that quercetin inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis of murine B16 melanoma cell lines,

in vitro [

23]. Similarly, quercetin showed anti-melanoma effects both

in vitro and

in vivo, and increased apoptosis of A375SM human melanoma cell lines through activation of JNK/P38 MAPK signaling pathway [

24]. Regarding the phytoestrogen properties, quercetin can bind to GPER as a natural agonist as demonstrated by Maggiolini,

et al. (2004). In their study, GPER in SKBR3 breast cancer cells was activated by quercetin leading to rapid activation of ERK1/2 and up-regulation of c-fos [

25]. Within the same context, it was shown that quercetin suppressed osteoclastogenesis by GPER activation and inhibition of Akt phosphorylation [

26].

Another important flavonoid is luteolin (3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxy flavone), which is characterized by the presence of a double bond between C2 and C3 and two hydroxyl groups in each benzene ring. As an anti-cancer agent, this compound can suppress cell transformation, angiogenesis, metastasis and invasion of cancer cells via different mechanisms including cell cycle regulation, inhibition of kinases, stimulation of apoptosis and alteration of gene expression [

27]. In melanoma, luteolin was able to block the tumor progression in murine B16F10 melanoma cell line, and to reduce the invasiveness by targeting β3 integrin and epithelial-mesenchymal transition [

28]. In another study on human choroidal melanoma, it was demonstrated that luteolin decreased the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in C918 and OCM-1 cells [

29]. Little information is available about the interaction of luteolin with ERs. Molecular docking studies suggested that luteolin has the ability to bind to ERα and ERβ as well as to GPER [

30].

The aim of the present study was to investigate the anti-tumor effects of quercetin and luteolin on GPER expressing melanoma cell line, A375. We evaluated the potential agonistic properties of quercetin and luteolin as phytoestrogens by exploring their ability to activate GPER, along with their influence on the key signaling pathways Ras/Raf/Erk and PI3K/Akt. The data shows that quercetin and luteolin increased P-ERK and c-Myc and these effects were reversed by the specific antagonist of GPER, indicating that the flavonoids’ effects were mediated by GPER, highlighting the potential anti-melanoma therapeutic effects of the two compounds.

4. Discussion

Melanoma, a type of skin cancer known for its aggressive nature, has been traditionally considered a non-hormone-related malignancy. However, emerging evidence suggests that sex hormones, particularly estradiol (E2), might influence melanoma development and progression. One significant discovery in this context is the G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER), which has been identified as a receptor for estrogens and is increasingly being explored in cancer research, including CM. Melanoma is characterized by its aggressive growth and resistance to conventional treatments, making the exploration of novel therapeutic targets, like GPER, increasingly important.

In a study by Ribeiro

et al. (2017), the inhibitory effects of GPER activation on melanoma cells were explored using the mouse K1735-M2 melanoma cell line. Using specific agonists like G-1 and 17β-estradiol, the selective ER modulators tamoxifen (TAM) and its key metabolite endoxifen (EDX) to activate GPER, these authors observed a significant reduction in cell proliferation and cell division, indicating that GPER activation might have tumor-suppressive effects in melanoma cells. Furthermore, they found that the use of GPER agonists modulated MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways by reducing the levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 [

40]. These pathways are critical for regulating cell survival, proliferation, and migration, and they are commonly activated in up to 50% of CM, contributing to its aggressive nature and resistance to conventional therapies [

41].

Recent research by Ambrosini

et al. (2023) significantly advanced our understanding of the role of GPER in melanoma, particularly in uveal melanoma, a rare and aggressive form of melanoma that typically develops in the eye [

42]. Uveal melanoma is known for its poor prognosis and resistance to conventional treatments, making it an area of intense research for novel therapeutic strategies. Ambrosini group investigated the effects of a GPER-specific agonist, LNS8801, on uveal melanoma cells and demonstrated its ability to induce mitotic arrest and apoptosis in these cells. The study found that LNS8801, by activating GPER, caused a disruption in the cell cycle, specifically at the mitotic phase. This mitotic arrest is a crucial event because it prevents the cells from progressing through critical stages of division, effectively halting their proliferation, and this disruption triggered apoptosis. The ability of LNS8801 to induce both mitotic arrest and apoptosis indicates its potential as a powerful therapeutic agent for treating uveal melanoma. Ambrosini and his colleagues also provided insights into the molecular mechanisms behind these effects. They suggested that the activation of GPER by LNS8801 might interfere with key signaling pathways that regulate cell cycle progression and survival, including the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways. These pathways are often deregulated in cancer and contribute to malignant cell behavior, such as uncontrolled proliferation and resistance to cell death. By targeting GPER with LNS8801, it was hypothesized that the balance of these pathways could be shifted in favor of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, ultimately inhibiting tumor growth [

42].

The current study aimed to investigate the role of GPER in mediating the antiproliferative and antitumor effects of two flavonoids, quercetin and luteolin, in human A375 melanoma cell line. These antiproliferative and antitumor effects were observed in cell viability, flow cytometry, cell migration, and in cell cycle experiments. We hypothesized that these flavonoids exert their effects primarily through GPER activation, which would then modulate critical signaling pathways such as Ras/Raf/Erk and PI3K/Akt. These pathways are fundamental in regulating essential cellular processes like growth, survival, and migration, all of which are crucial in melanoma progression. To examine the estrogenic properties of quercetin and luteolin, their effects were compared to those evoked by the selective agonist, G-1, which can activate the receptor and induce physiological responses at low concentrations [

43,

44]. Both flavonoids increased the expression of GPER just like G-1 and these effects seemed to be impacted by GPER blockage by the specific antagonist, G15.

To test our hypothesis, we first evaluated the antiproliferative effects of quercetin and luteolin on A375 melanoma cells using the MTT assay, a standard method for assessing cell viability. Our results revealed that both quercetin and luteolin significantly inhibited the proliferation of A375 cells. Quercetin exhibited an IC

50 value of 38.6 µM, while luteolin demonstrated a slightly more potent effect, with an IC

50 value of 19.5 µM (

Fig. 2). These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting similar effects of quercetin on other cancer cell types, such as T47D cancer stem cells [

45]. In the case of luteolin, our results align with those of Fan

et al. (2019) and Schomberg

et al. (2020) who observed comparable inhibitory effects on A431 and A375 cells, with IC

50 values of 19 µM and 12.5 µM, respectively. Collectively, these results highlight the potential of quercetin and luteolin as effective agents for targeting melanoma cells. The consistent potency of luteolin across multiple studies [

46,

47] further supports its broader applicability as a promising anticancer agent.

However, we observed some inconsistencies in the IC

50 values for quercetin, which could be attributed to variations in experimental conditions, particularly the type of cell culture medium used [

48]. In our study, we cultured the A375 cells in MEM, whereas the study by Cao

et al. (2014) used Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) for the same incubation period (48 hrs.) [

49]. These differences in medium composition, which can affect nutrient availability and overall cell growth, might explain some of the observed variation in the IC

50 values for quercetin. Such differences are commonly seen in cell-based assays and further underscore the importance of standardizing experimental conditions when comparing data across different studies.

Our MTT assay results strongly corroborated the significant effects of both quercetin and luteolin on A375 melanoma cells, providing additional support to the studies that showed these flavonoids are holding potential as therapeutic agents for melanoma treatment. In addition to their effects on proliferation, both flavonoids as well as G-1 also demonstrated significant anti-migratory activity in A375 melanoma cells (

Fig. 7). This observation aligns with previous studies indicating that quercetin and luteolin can inhibit melanoma cell migration. For example, Cao

et al. (2015) reported that quercetin suppressed A375 migration by interfering with the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/c-Met signaling pathway, a key mediator of cell migration and metastasis [

50]. Similarly, Yao

et al. (2019) showed that luteolin inhibited matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) through the PI3K/Akt pathway and reduced migration of A375 [

51]. Additionally, Hanaf

et al. (2024) demonstrated that treatment of ovarian cell lines, OV90 and OVCAR420 as well as immortalized fallopian tube cell line, FT190 with 1µM G-1 significantly decreased migration after 12 hrs. [

52]. When we used G15 to block GPER, the antimigratory effects induced by quercetin, luteolin and G-1 were partially abolished, which further supports the hypothesis that GPER activation plays a pivotal role in mediating the antiproliferative and antimigratory actions of quercetin and luteolin (

Fig. 6 and

Fig. 7).

We next investigated the effects of quercetin and luteolin on apoptosis and cell cycle regulation. Both flavonoids (30 µM and 100 µM) induced significant apoptosis and necrosis in A375 cells (

Fig. 4) in consistence with previous studies in other cancer models [

53,

54]. Furthermore, consistent with other reports, quercetin and luteolin arrested the cell cycle at S and G2/M phases (

Fig. 5) [

55,

56]. The GPER agonist G-1 also induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, providing additional evidence that GPER activation is crucial for the observed effects of quercetin and luteolin on melanoma cells.

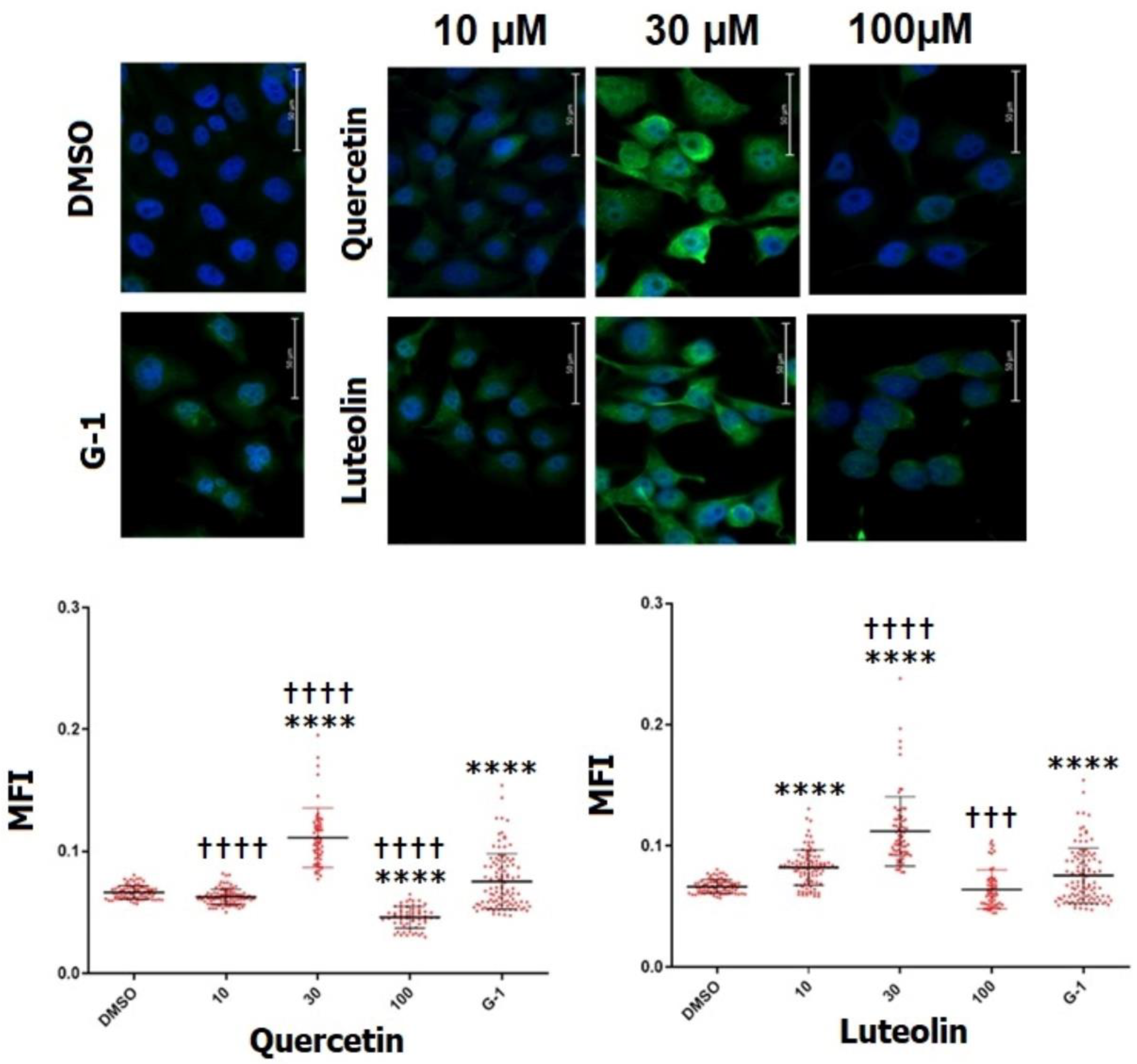

Immunostaining experiments further confirmed the expression of GPER in A375 cells and revealed that treatment with the agonist, G-1 upregulated GPER expression

(Fig. 8). Our results are in agreement with Almedia,

et al. (2022) who showed that the expression level of GPER in glioblastoma C6 was enhanced following treatment with E2 or G-1 for 48 hrs. [

57]. Interestingly, quercetin and luteolin, particularly at 30µM resulted in a pronounced increase in immunofluorescence, hence GPER expression, compared to G-1, suggesting that these flavonoids may act as agonists to GPER and could exert their physiological effects through activation of GPER in a way similar to that of G-1. This observation diverges from the findings of Sun,

et al. (2016), who reported that G-1 did not affect GPER expression in A375 melanoma cell line [

31], presumably due to differences in experimental conditions, such as the lower concentrations (0.2, 0.4, 0.8 µM) and the shorter incubation period (24 hrs.) used in their study. Of note, at the highest concentration (100 µM), quercetin caused a lower MFI value than DMSO, while the MFI of luteolin was similar to that of DMSO, possibly due to the high toxicity of the flavonoids which reduced the number of viable cells that could be counted. On the other hand, receptor desensitization and internalization as a response to sustained activation by high doses of an agonist may also be involved in this reduction [

58].

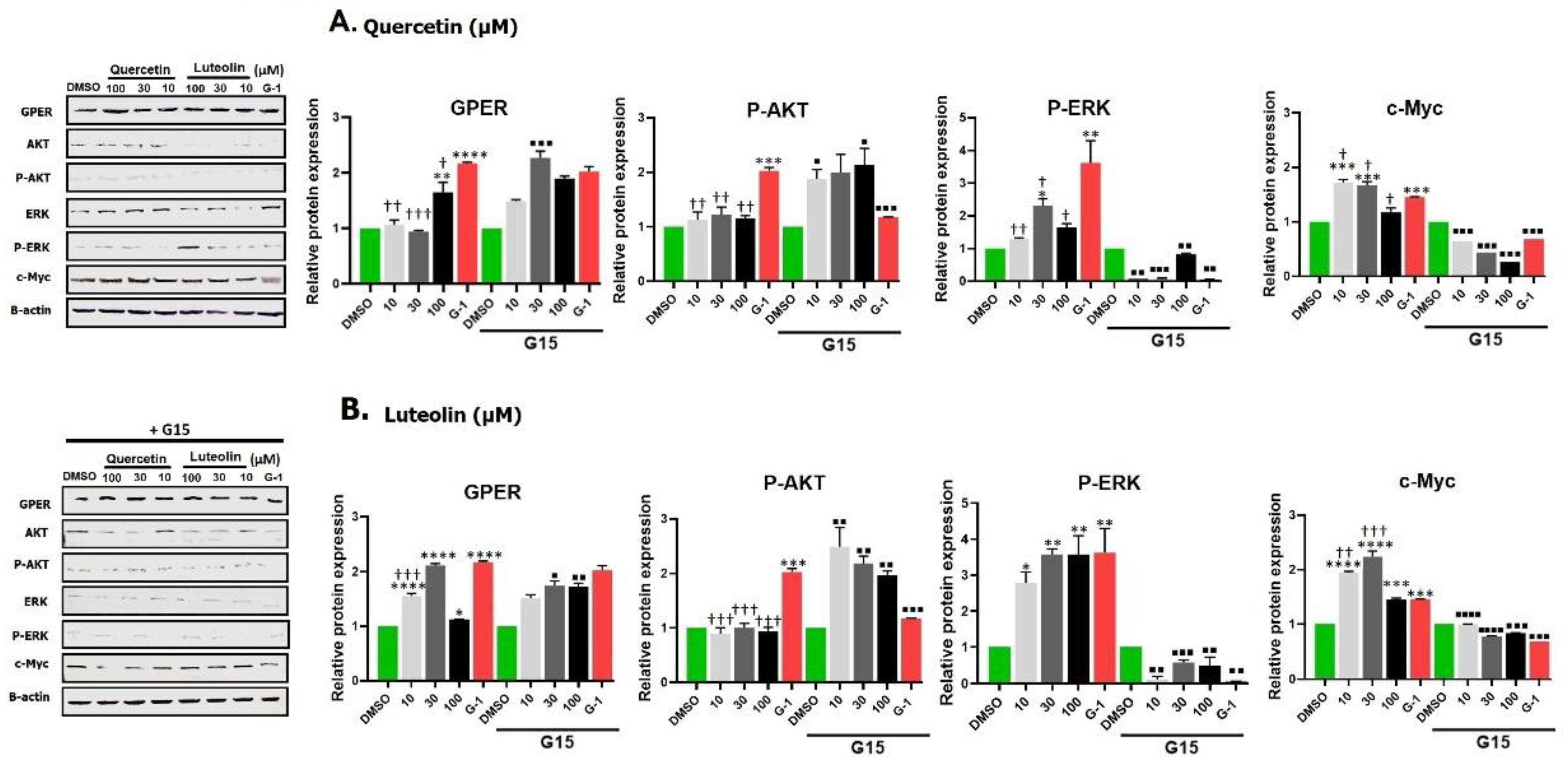

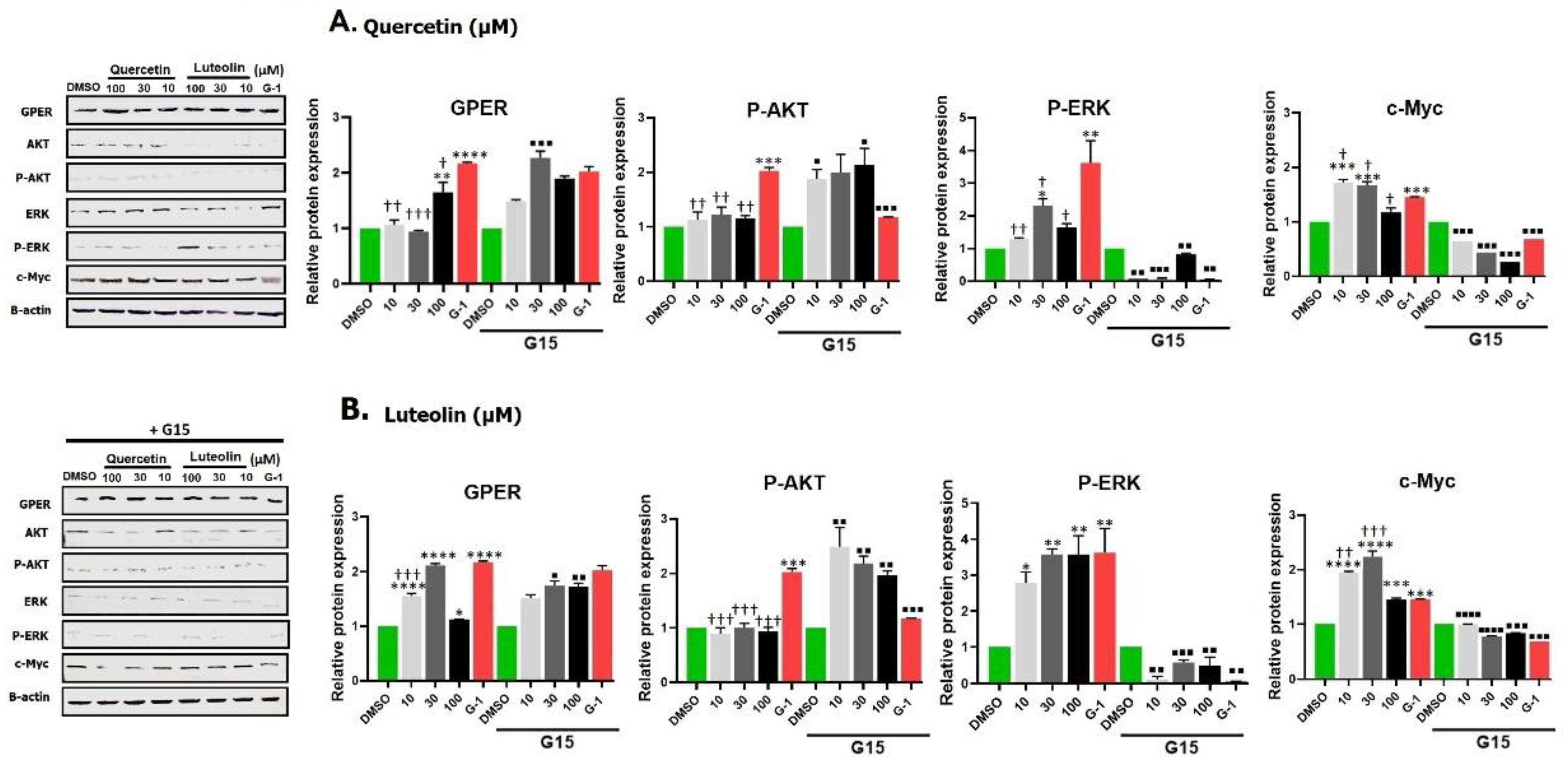

Building on these results, we aimed to investigate the underlying mechanisms through which quercetin and luteolin exert their antiproliferative effects. We examined the impact of GPER activation by G-1, quercetin, and luteolin on the Ras/Raf/Erk and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways by Western blotting. First we found that G-1, as GPER agonist, increased the expression level of GPER in A375 melanoma cells. Quercetin at 100µM and luteolin at all concentrations also increased the expression of GPER. We observed some differences between the results obtained by immunofluorescence and Western blot regarding the effect of flavonoids on GPER expression. This could be attributed to the shorter stimulation time we used in Western blot (24 hrs.) compared to immunofluorescence assay (48 hrs.). These differences suggested that quercetin at lower doses (10 and 30µM) may need a longer time to interact with GPER and increase its expression, unlike luteolin which was more efficient in its ability to bind to the receptor and elevate its level in shorter time. ERK protein is the key effector in Ras-Raf-Erk signaling pathway. Although it was found that about 40% of human cancers were associated with aberrant ERK pathway activity, a recent review by Timofeev and collaborators cited the evidence that BRAF mutant melanomas like A375 cells are sensitive to ERK activation, and overexpression of ERK has an inhibitory effect in this cell line [

59]. Others suggested that while ERK signaling is typically associated with cell survival, it can also promote cell death under certain conditions. Prolonged or excessive activation of ERK, often induced by stress or DNA damage, can lead to cellular dysfunction and apoptosis [

60]. Consistent with the above observations, we observed an increase in the expression of phosphorylated ERK (P-ERK) in response to treatment with both flavonoids as well as in G-1 (

Fig. 9). Quercetin or luteolin antioxidant properties may then alter the cellular redox state, creating an environment in which ERK activation shifts from a pro-survival signal to one that increases cellular stress, potentially shifting the balance toward cell death. These findings underscore the complexity of signaling networks in melanoma cells and highlight the balance between pro-survival and pro-apoptotic pathways in response to quercetin and GPER activation. Taken together, the data indicate that GPER activation can transactivate the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and activate the Ras/Raf/Erk pathway. This conclusion is substantiated by the finding that the effect of both flavonoids and G-1 was consistently reversed in the presence of the antagonist G-15.

c-Myc is a transcription factor that plays an important role in proliferation, metabolism, cell cycle and apoptosis. Its expression is elevated in about 50% of cancers including CM, mainly through Ras/Raf/Erk and/or PI3K/Akt pathways, leading to tumor progression [

61]. In the current study, we noticed an unexpected increase in the level of c-Myc following treatment with both flavonoids and G-1. This observation was different from the findings of Natale,

et al. (2017), who showed that loss of c-Myc is a major pathway of the anti-proliferative effects of GPER signaling in melanoma [

62]. Although Myc is a potent stimulus of growth and proliferation, it was found to sensitizes cells to apoptosis which limits its tumorigenic capacity. This Myc sensitization was interpreted as triggered by the limitation of the tricarboxylic cycle [

63] or due to imbalance of metabolic/energetic supply and demand. We speculate that the observed upregulation of c-Myc may represent a compensatory mechanism in response to DNA damage or toxicity induced by the treatments. Alternatively, it was proposed that c-Myc directs P53 functions towards apoptosis rather than cell cycle arrest and reduces the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 [

64]. Within the same context, it was previously demonstrated that c-Myc upregulation leads to accumulation of P53 which increases cell apoptosis in murine intestinal enterocytes following DNA damage [

65]. The increase in the expression of c-Myc by both flavonoids and by G-1 was significantly reversed when cells were treated with the G-15 antagonist, indicating that this increase in c-Myc was mediating GPER activation by these phytoestrogens, and again confirming the potential therapeutic effect of these flavonoids in management of CM.

We also observed no change in Akt phosphorylation (P-Akt) after quercetin and an insignificant decrease after luteolin but an unexpected increase after G-1 treatment, which contrasts with the findings of Liu,

et al. (2022), who reported a decrease in P-Akt following G-1 treatment in SKBR-3 breast cancer cells [

66]. This difference may be attributed to differences in cell type and experimental conditions. High levels of P-Akt are usually associated with increased cell growth and anti-apoptotic effects. Additionally, although quercetin and luteolin did not significantly alter Akt phosphorylation in A375 cells, luteolin did reduce total Akt levels, in agreement with the findings by Yao

et al. (2019) in melanoma cells, suggesting an inhibition of cell proliferation and survival [

51]. These results suggest that GPER-mediated effects on the PI3K/Akt pathway may vary depending on the cellular context, underscoring the complexity of GPER signaling in melanoma. In our experiment, the antagonist G15 significantly reversed the effects of the flavonoids as well as those of G-1, indicating that these effects were mediated through GPER activation. Concerning the estrogen agonistic potency of quercetin and luteolin, Nordeen

et al. (2013) showed that luteolin displayed greater estrogen agonistic activity than quercetin in T47D (A1-2) cells that express progesterone and estrogen receptors [

67]. Little differences were noticed in our study between the effects of the two phytoestrogens on A375 melanoma cell line. As we noticed that 100 µM could be more toxic to cells, the dose of 30 µM is preferable in future research on this cell line, since it is also the nearest to the IC

50 of quercetin and luteolin. Structure of the two flavonoids plays a fundamental role in the nature and potency of their activity. Number and position of hydroxyl groups, as well as the presence of the double bond between carbons 2 and 3 and the presence or absence of methyl groups are the main factors that determine the estrogenic activity of these flavonoids [

68,

69]. Quercetin and luteolin have 5 and 4 hydroxyl groups, respectively, and both have a double bond between C2-C3 that confers on them high potency.

Our study provides novel insights into the role of GPER in mediating the anticancer effects of quercetin and luteolin in melanoma cells. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that these flavonoids can induce antiproliferative, pro-apoptotic, and antimigratory effects through GPER activation in A375 melanoma cells, highlighting the potential of GPER-targeted therapeutic strategies for melanoma treatment. Future studies should continue to explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the role of GPER in melanoma and other cancers, with a particular focus on the differential cellular responses to phytoestrogens like quercetin and luteolin. Understanding these mechanisms will be essential for developing more effective therapeutic approaches targeting GPER in melanoma and other malignancies.

Figure 1.

Cell viability of A375 melanoma cell line at different incubation periods. Cells were treated with quercetin (A) or luteolin (B) at 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 µM and DMSO (0.2%) as a negative control. MTT assay was performed to assess cell viability after 24, 48, and 72 hrs. Data are presented as the means ±SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 1.

Cell viability of A375 melanoma cell line at different incubation periods. Cells were treated with quercetin (A) or luteolin (B) at 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 µM and DMSO (0.2%) as a negative control. MTT assay was performed to assess cell viability after 24, 48, and 72 hrs. Data are presented as the means ±SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Effects of the tested flavonoids on proliferation of A375 melanoma cells. Cells were treated for 48 hrs. with 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100µM of quercetin (A) or luteolin(B); G-1 (1µM) served as a positive control, and DMSO (0.2%) as a negative control. Data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001 compared to DMSO; ††† p <0.001, †††† p <0.0001 compared to G-1).

Figure 2.

Effects of the tested flavonoids on proliferation of A375 melanoma cells. Cells were treated for 48 hrs. with 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100µM of quercetin (A) or luteolin(B); G-1 (1µM) served as a positive control, and DMSO (0.2%) as a negative control. Data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001 compared to DMSO; ††† p <0.001, †††† p <0.0001 compared to G-1).

Figure 3.

Effects of quercetin and luteolin on the growth and morphology of A375 melanoma cells. Cells were treated with DMSO (0.2%) as a negative control and G-1 as a positive control, and with the indicated concentrations of quercetin (upper panel) or luteolin (lower panel). .

Figure 3.

Effects of quercetin and luteolin on the growth and morphology of A375 melanoma cells. Cells were treated with DMSO (0.2%) as a negative control and G-1 as a positive control, and with the indicated concentrations of quercetin (upper panel) or luteolin (lower panel). .

Figure 4.

Flow cytometry analysis of cell apoptosis. A375 cells were treated with.

Figure 4.

Flow cytometry analysis of cell apoptosis. A375 cells were treated with.

Figure 5.

Cell cycle distribution of A375 melanoma cell lines. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of quercetin (A) or luteolin (B), 1µM of G-1 as a positive control, and 0.2% DMSO as a negative control. After 48 hrs., cells were fixed, stained with PI and analyzed flow cytometry (right panels). The percentage of cells in G1, S and G2/M phases for each treatment was calculated and analyzed (left panels). Data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. (****p < 0.0001 compared to DMSO; ††p <0.01, †††† p <0.0001 compared to G-1).

Figure 5.

Cell cycle distribution of A375 melanoma cell lines. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of quercetin (A) or luteolin (B), 1µM of G-1 as a positive control, and 0.2% DMSO as a negative control. After 48 hrs., cells were fixed, stained with PI and analyzed flow cytometry (right panels). The percentage of cells in G1, S and G2/M phases for each treatment was calculated and analyzed (left panels). Data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. (****p < 0.0001 compared to DMSO; ††p <0.01, †††† p <0.0001 compared to G-1).

Figure 6.

Effects of pretreatment with the GPER inhibitor, G15, on proliferation of melanoma cells. A375 cells were incubated for 24 hrs. with 3 µM G15 before being treated with 10, 30, and 100µM of quercetin (A) or luteolin (B), or G-1 (1µM) as a positive control. 0.2% DMSO was used as a negative control. Data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis. Significance levels: ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.000, compared to treatments with G15.

Figure 6.

Effects of pretreatment with the GPER inhibitor, G15, on proliferation of melanoma cells. A375 cells were incubated for 24 hrs. with 3 µM G15 before being treated with 10, 30, and 100µM of quercetin (A) or luteolin (B), or G-1 (1µM) as a positive control. 0.2% DMSO was used as a negative control. Data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis. Significance levels: ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.000, compared to treatments with G15.

Figure 7.

Migration of A375 cells under different treatments. Cells were exposed for 48 hrs. to the indicated concentrations of quercetin (A) or luteolin (B), G-1 (positive control), and 0.2% DMSO (negative control), with or without 3µM of G15 (GPER antagonist). Transwell migration assay was performed for 48 hrs. and the number of the migrating cells is shown in the right panel. Values are means±SD of 10 fields/treatment. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to DMSO; †p < 0.05, †††† p <0.0001 compared to G-1; ■P < 0.05, ■■P < 0.01compared to treatment with G15).

Figure 7.

Migration of A375 cells under different treatments. Cells were exposed for 48 hrs. to the indicated concentrations of quercetin (A) or luteolin (B), G-1 (positive control), and 0.2% DMSO (negative control), with or without 3µM of G15 (GPER antagonist). Transwell migration assay was performed for 48 hrs. and the number of the migrating cells is shown in the right panel. Values are means±SD of 10 fields/treatment. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to DMSO; †p < 0.05, †††† p <0.0001 compared to G-1; ■P < 0.05, ■■P < 0.01compared to treatment with G15).

Figure 8.

Detection of GPER expression in A375 melanoma cells by immunofluorescence staining. Cells were treated for 48 hrs. with 10, 30 and 100 µM of quercetin, luteolin, or 1µM G-1 as a positive control. DMSO (0.2%) was used as negative control. Representative immunofluorescence images captured by time-lapse fluorescence microscope are shown (upper panels). Green signal indicates positive staining for GPER, while the blue signal (DAPI) represents the nuclei. Scatter dot plots show the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for GPER determined by cell profiler software (Lower panels). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (****p < 0.0001 compared to DMSO; ††† p <0.001, †††† p <0.0001 compared to G-1).

Figure 8.

Detection of GPER expression in A375 melanoma cells by immunofluorescence staining. Cells were treated for 48 hrs. with 10, 30 and 100 µM of quercetin, luteolin, or 1µM G-1 as a positive control. DMSO (0.2%) was used as negative control. Representative immunofluorescence images captured by time-lapse fluorescence microscope are shown (upper panels). Green signal indicates positive staining for GPER, while the blue signal (DAPI) represents the nuclei. Scatter dot plots show the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for GPER determined by cell profiler software (Lower panels). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (****p < 0.0001 compared to DMSO; ††† p <0.001, †††† p <0.0001 compared to G-1).

Figure 9.

Effects of different treatments with quercetin (

A) or luteolin (

B), G-1 (positive control), and 0.2% DMSO (negative control) on the expression of GPER, P-Akt, P-ERK, and c-Myc in A375 melanoma cell line. Representative Western blots images are shown (

left panels). Densitometry analysis was performed and the relative protein expression was normalized to β-actin (

right panels). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (*p < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to DMSO; †p < 0.05, ††p <0.01, ††† p <0.001, †††† p <0.0001 compared to G-1. In the presence of 3µM of the antagonist G15, the relative protein expressions were significantly reversed where:

■P < 0.05,

■■P < 0.01,

■■■P < 0.001,

■■■■P < 0.0001 compared to the same concentration and ligand in its absence. A complete densitometry analysis for GPER, total Akt, p-Akt, p-Akt/total Akt, total ERK, p-ERK, p-ERK/total ERK, and c-Myc for quercetin and luteolin is shown in

Appendix Figure (

Fig. A1).

Figure 9.

Effects of different treatments with quercetin (

A) or luteolin (

B), G-1 (positive control), and 0.2% DMSO (negative control) on the expression of GPER, P-Akt, P-ERK, and c-Myc in A375 melanoma cell line. Representative Western blots images are shown (

left panels). Densitometry analysis was performed and the relative protein expression was normalized to β-actin (

right panels). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (*p < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to DMSO; †p < 0.05, ††p <0.01, ††† p <0.001, †††† p <0.0001 compared to G-1. In the presence of 3µM of the antagonist G15, the relative protein expressions were significantly reversed where:

■P < 0.05,

■■P < 0.01,

■■■P < 0.001,

■■■■P < 0.0001 compared to the same concentration and ligand in its absence. A complete densitometry analysis for GPER, total Akt, p-Akt, p-Akt/total Akt, total ERK, p-ERK, p-ERK/total ERK, and c-Myc for quercetin and luteolin is shown in

Appendix Figure (

Fig. A1).

Table 1.

Primary antibodies that were used in Western blots.

Table 1.

Primary antibodies that were used in Western blots.

| Antibody |

Host species |

Cat. No. |

Supplier |

Dilution |

Band size(kDa) |

| GPER |

Rabbit |

ES11471 |

ELK Biotechnology |

1:500 |

41 |

| ERK1/2 |

Rabbit |

EA331 |

ELK Biotechnology |

1:500 |

42-44 |

| P-ERK1/2 |

Mouse |

Sc-136521 |

Santa Cruz |

1:500 |

42-44 |

| Akt 1/2/3 |

Mouse |

Sc- 56878 |

Santa Cruz |

1:500 |

62 |

| P-Akt |

Rabbit |

Ab38449 |

Abcam |

1:500 |

56 |

| c-Myc |

Rabbit |

EA053 |

ELK Biotechnology |

1:1000 |

57-65 |

| B-actin |

Rabbit |

GW0061R |

GenoChem World |

1:1000 |

42 |