Submitted:

01 August 2023

Posted:

03 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Cell culture

2.3. Preparation of quercetin stock solution

2.4. Cell viability analysis

2.4.1. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

2.4.2. Experimental groups:

2.5. Assessment of the antioxidant activity

2.5.1. Sample preparation

2.5.2. Lipid peroxidase activity

2.5.3. Catalase activity

2.5.4. Superoxide dismutase activity

2.5.5. Total thiol content activity

2.6. Assessment of free radical scavenging activity

2.6.1. ABTS free radical scavenging activity

2.6.2. DPPH free radical scavenging activity

2.7. Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity

2.8. Gene expression analysis by qPCR

2.9. Epigenetic modification assays

2.9.1. HDAC quantification assay

2.9.2. hTERT quantification assay

2.10. Inflammatory cytokines and angiogenic factor expression analysis by ELISA

2.11. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) expression

2.12. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cell viability analysis

3.1.1. CCK-8 assay

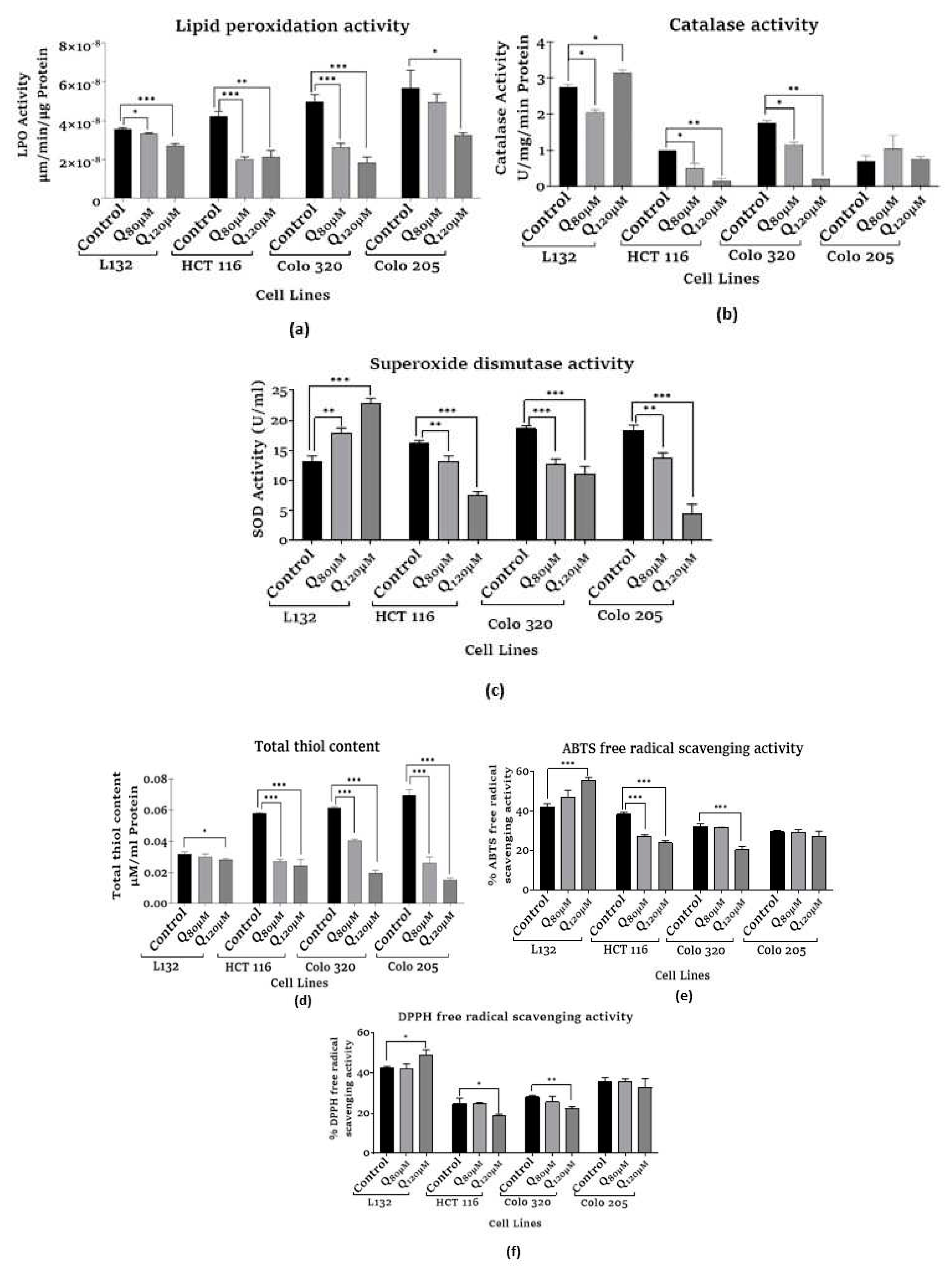

3.2. Assessment of antioxidant activity

3.2.1. Assessment of lipid peroxidation (LPO) assay

3.2.2. Assessment of catalase activity

3.2.3. Assessment of superoxide dismutase activity

3.2.4. Assessment of total thiol content

3.3. Assessment of free radical scavenging activity

3.3.1. Assessment of ABTS free radical scavenging activity

3.3.2. Assessment of DPPH free radical scavenging activity

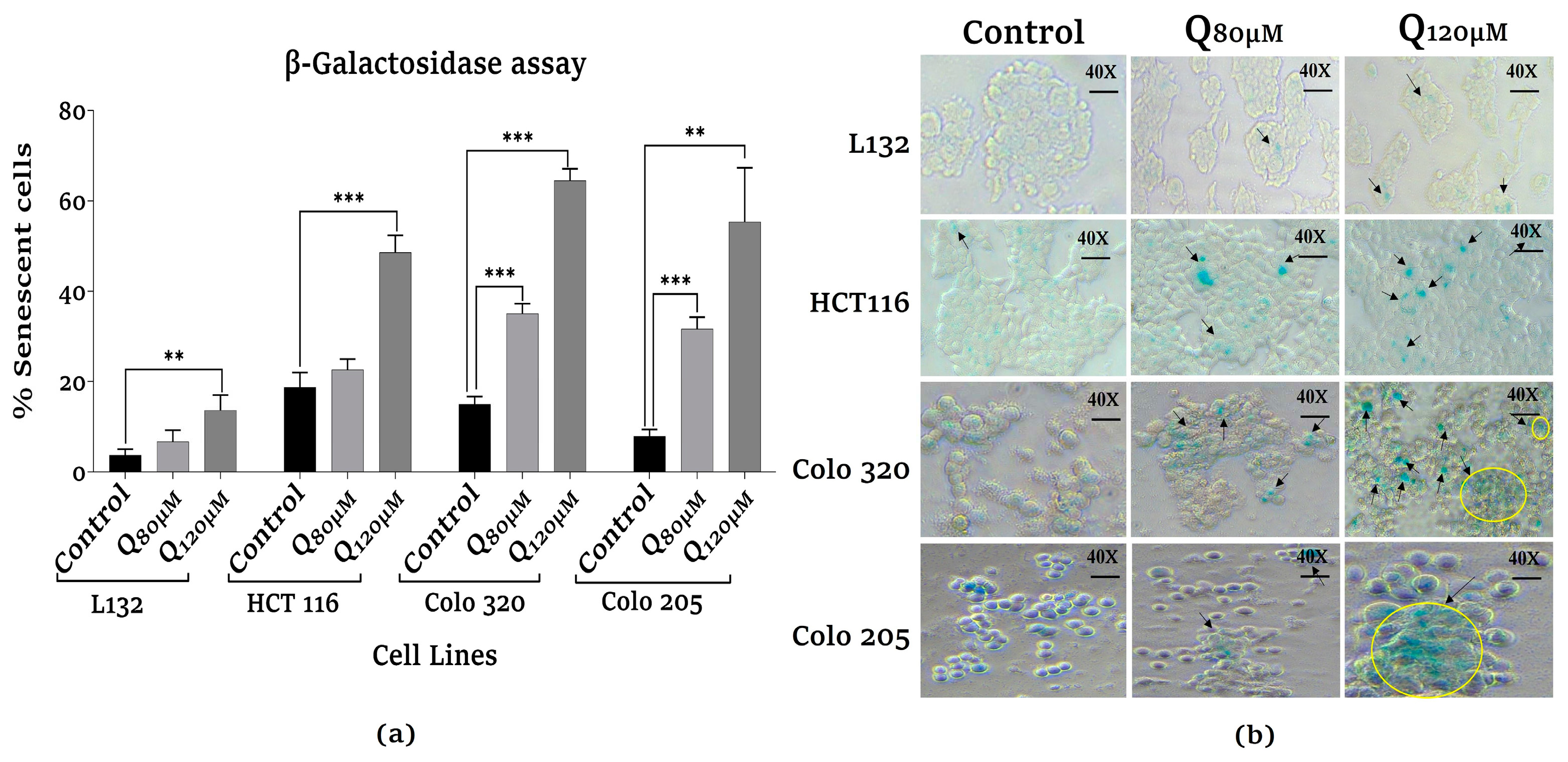

3.4. Assessment of senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity analysis

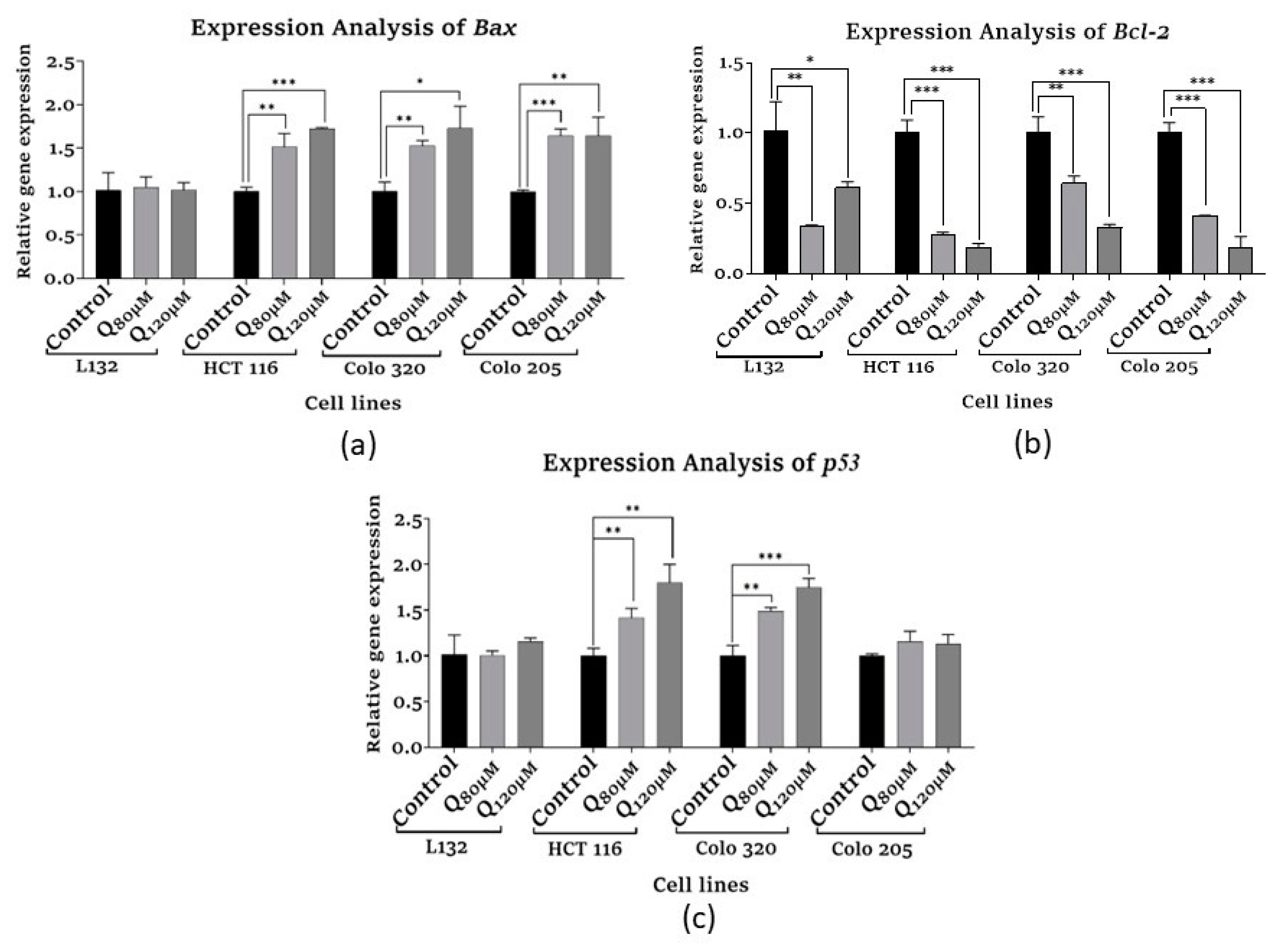

3.5. Gene expression analysis by qPCR

3.5.1. Apoptosis-related and Tumor suppressor gene expression

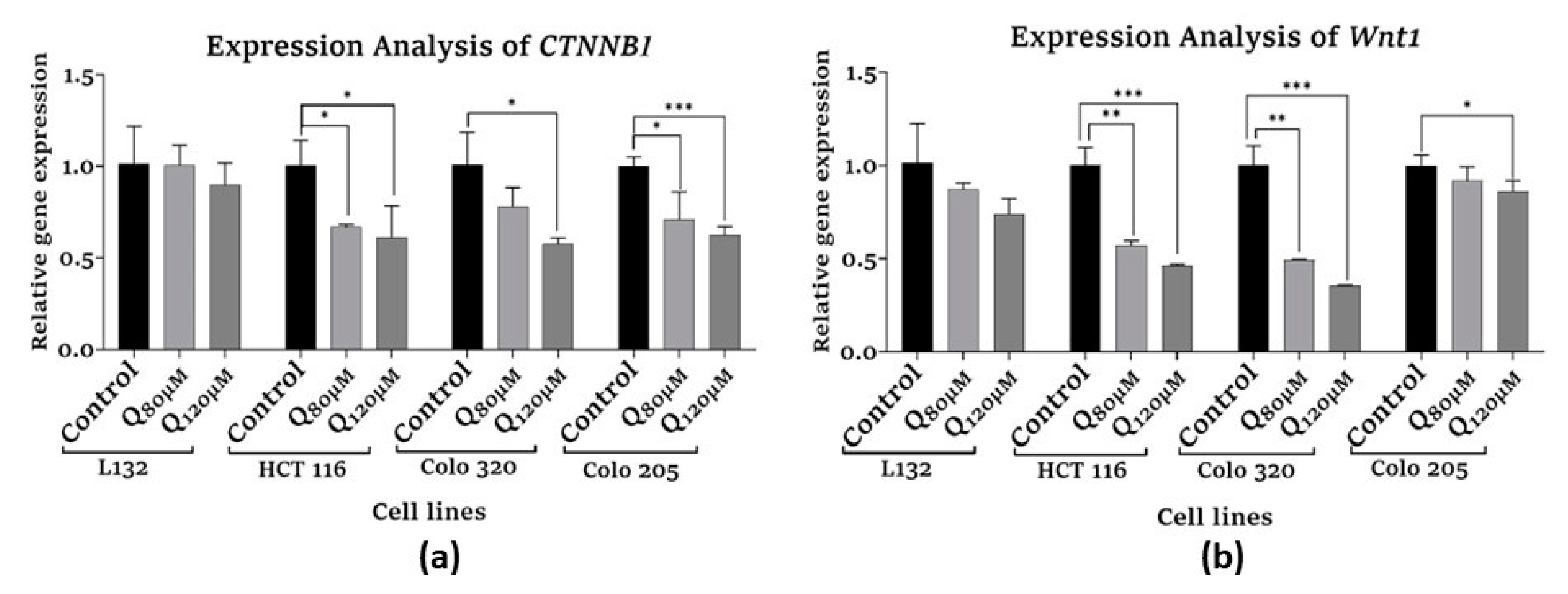

3.5.2. Proliferation-related gene expression

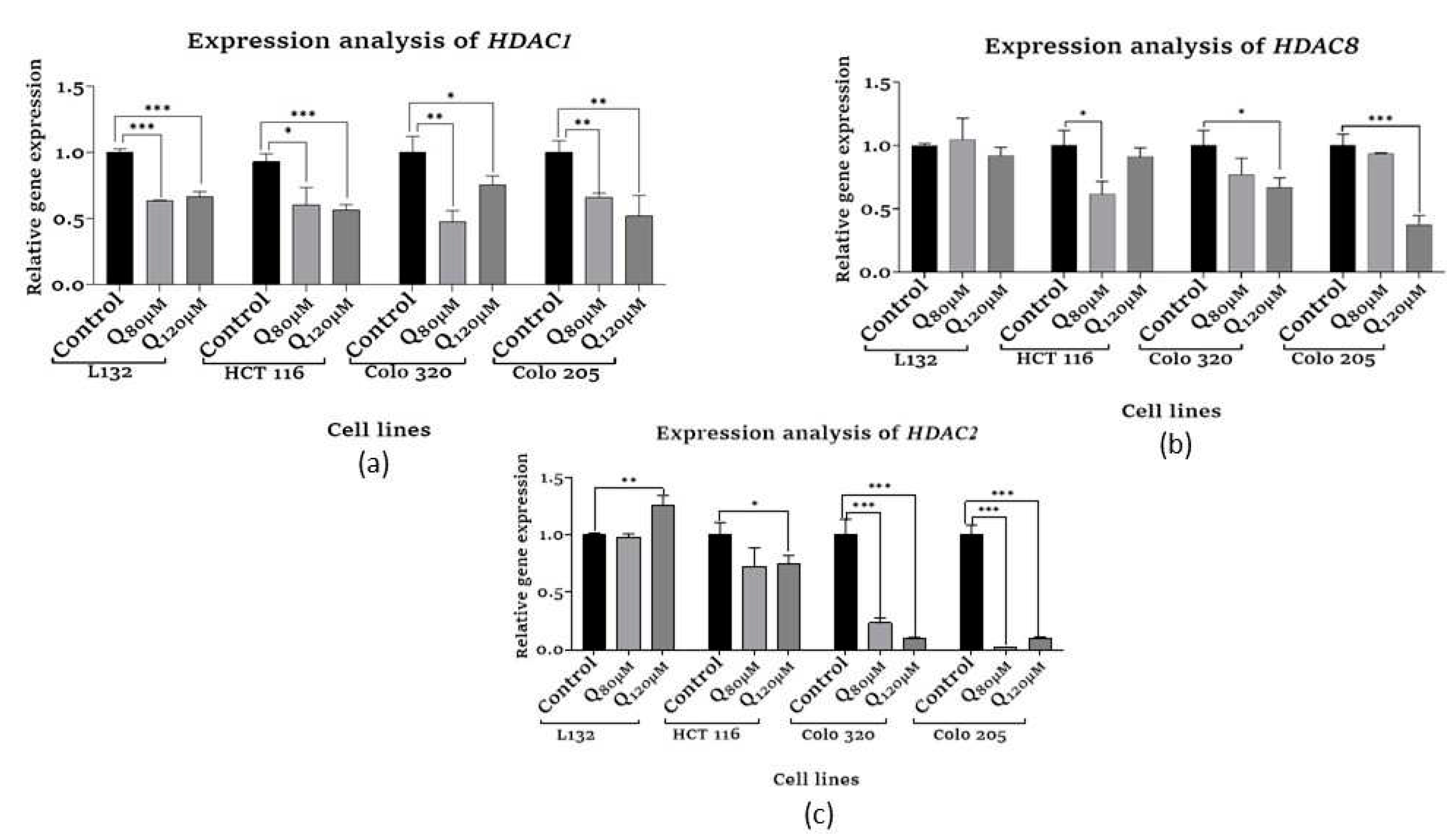

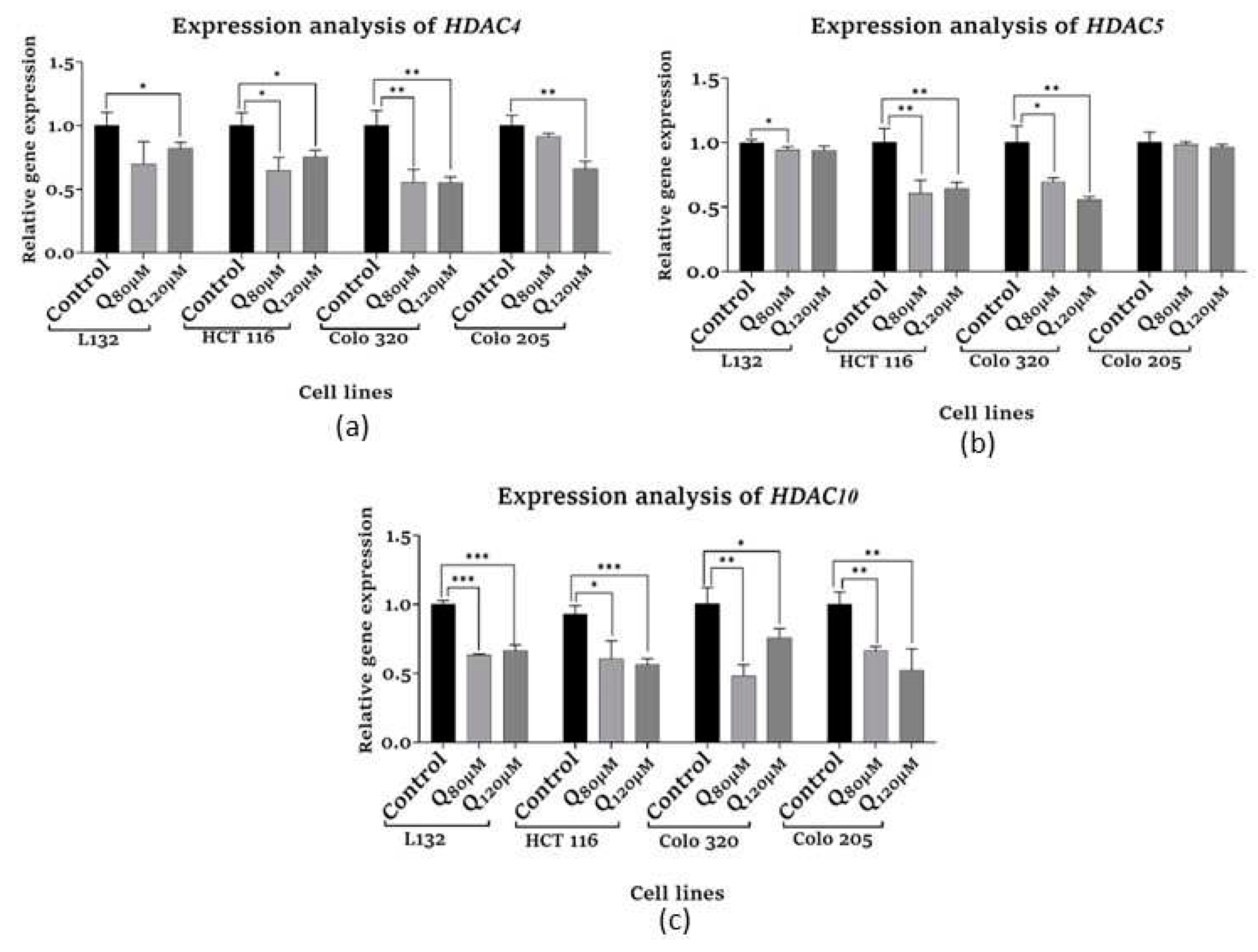

3.6. Epigenetic modification assays

3.6.1. HDAC Quantification assay

3.6.2. hTERT quantification assay

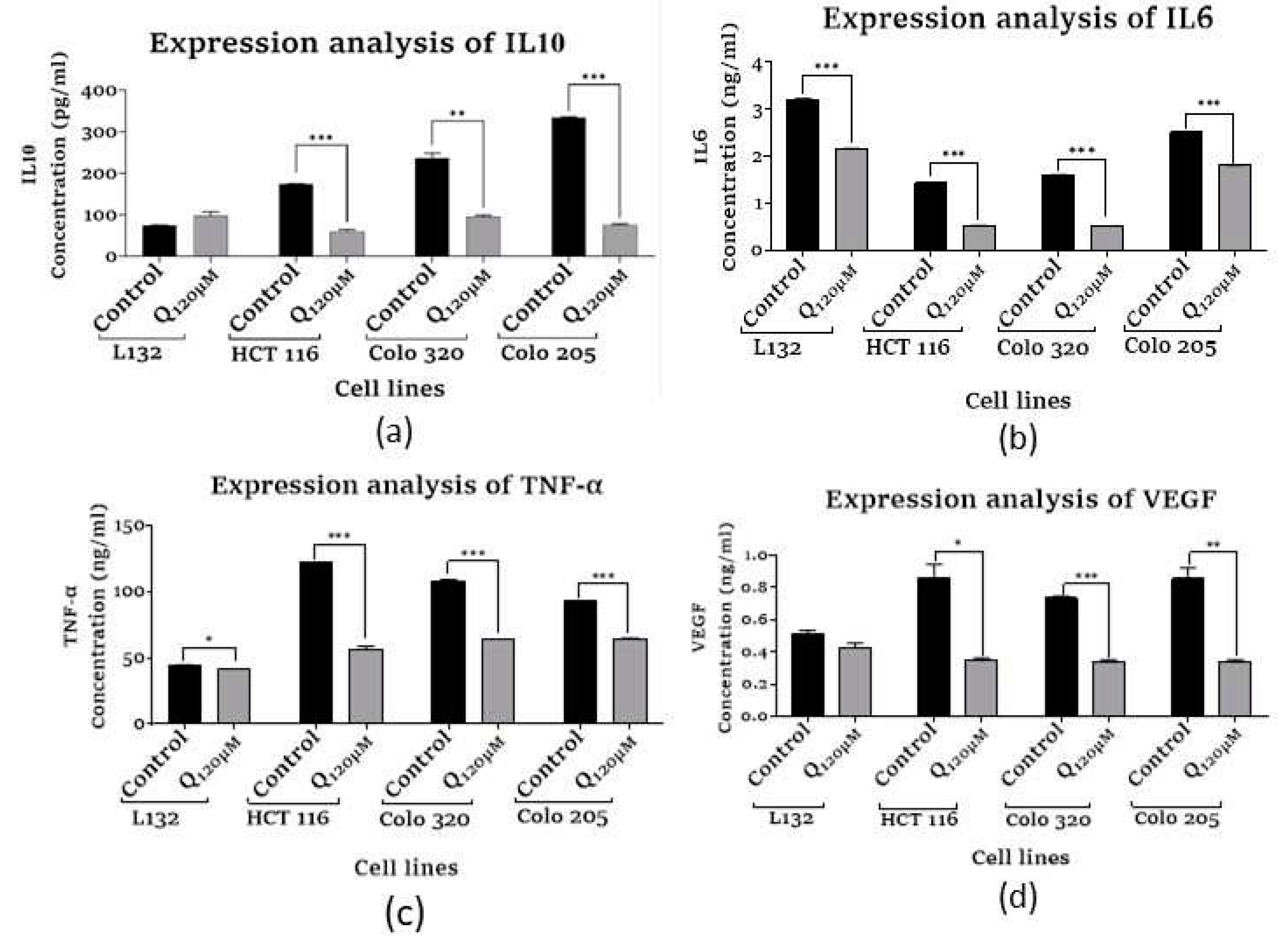

3.7. Inflammatory cytokines and angiogenic factor expression analysis

3.7.1. Assessment of Human Interleukin 10

3.7.2. Assessment of Human Interleukin 6

3.7.3. Assessment of Human Tumor Necrosis Factor-α

3.7.4. Assessment of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R. L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71 (3), 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Sawicki T; Ruszkowska M; Danielewicz A; Niedźwiedzka E; Arłukowicz T; Przybyłowicz KE. A Review of Colorectal Cancer in Terms of Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Development, Symptoms and Diagnosis. Cancers (Basel), 2021;13(9):2025. [CrossRef]

- Jung G; Hernández-Illán E; Moreira; Balaguer F; Goel A. Epigenetics of colorectal cancer: biomarker and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020;17(2):111-130. [CrossRef]

- Sriramulu, S; Malayaperumal, S; Deka, D.; Banerjee, A. and Pathak, S. A General Overview on Causes, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Role of Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer. Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects,2022, 3877-3895. [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski I; Kulcenty K; Suchorska W. Interplay between inflammation and cancer. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother, 2020;25(3):422-427. [CrossRef]

- D'Orazi G; Cordani M; Cirone M. Oncogenic pathways activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines promote mutant p53 stability: clue for novel anticancer therapies. Cell Mol Life Sci,2021;78(5):1853-1860. [CrossRef]

- Singh N; Baby D; Rajguru JP; Patil PB; Thakkannavar SS; Pujari VB. Inflammation and cancer. Ann Afr Med, 2019;18(3):121-126. [CrossRef]

- Fernández J, Silván B, Entrialgo-Cadierno R, et al. Antiproliferative and palliative activity of flavonoids in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother, 2021;143:112241. [CrossRef]

- Esmeeta A; Adhikary S; Dharshnaa V, et al. Plant-derived bioactive compounds in colon cancer treatment: An updated review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;153:113384. [CrossRef]

- Asgharian P; Tazekand AP; Hosseini K; et al. Potential mechanisms of quercetin in cancer prevention: focus on cellular and molecular targets. Cancer Cell Int, 2022;22(1):257. [CrossRef]

- Bhatiya M; Pathak S; Jothimani G; Duttaroy AK; Banerjee A. A Comprehensive Study on the Anti-cancer Effects of Quercetin and Its Epigenetic Modifications in Arresting Progression of Colon Cancer Cell Proliferation. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz), 2023;71(1):6. [CrossRef]

- Kesavan, P; Banerjee, A; Banerjee, A; Murugesan, R; Marotta, F and Pathak, S. An overview of dietary polyphenols and their therapeutic effects. Polyphenols: Mechanisms of Action in Human Health and Disease, 2018,221-235. [CrossRef]

- Batiha, GE; Beshbishy,AM; Ikram M; et al. The Pharmacological Activity, Biochemical Properties, and Pharmacokinetics of the Major Natural Polyphenolic Flavonoid: Quercetin. Foods, 2020;9(3):374. [CrossRef]

- Li Y; Zhang T; Chen GY. Flavonoids and Colorectal Cancer Prevention. Antioxidants (Basel),2018;7(12):187. [CrossRef]

- Zeb A; Ullah F. A Simple Spectrophotometric Method for the Determination of Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances in Fried Fast Foods. J Anal Methods Chem, 2016;2016:9412767. [CrossRef]

- Hadwan MH; Abed HN. Data supporting the spectrophotometric method for the estimation of catalase activity. Data Brief,2015;6:194-199. [CrossRef]

- Weydert CJ; Cullen JJ. Measurement of superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase in cultured cells and tissue. Nat Protoc, 2010;5(1):51-66. [CrossRef]

- Majkić N; Berkes I. Determination of free and esterified cholesterol by a kinetic method. I. The introduction of the enzymatic method with 2,2'-azino-di-3[ethyl-benzthiazolin sulfonic acid (6)] (ABTS). Clin Chim Acta, 1977;80(1):121-131. [CrossRef]

- Yuan XG; Huang YR; Yu T; Jiang HW; Xu Y; Zhao XY. Chidamide, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, induces growth arrest and apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells in a caspase-dependent manner. Oncol Lett, 2019;18(1):411-419. [CrossRef]

- Neamtu AA; Maghiar TA; Alaya A, et al. A Comprehensive View on the Quercetin Impact on Colorectal Cancer. Molecules, 2022;27(6):1873. [CrossRef]

- Xu D; Hu MJ; Wang YQ; Cui YL. Antioxidant Activities of Quercetin and Its Complexes for Medicinal Application. Molecules, 2019;24(6):1123. [CrossRef]

- Lo S; Leung E; Fedrizzi B; Barker D. Synthesis, Antiproliferative Activity and Radical Scavenging Ability of 5-O-Acyl Derivatives of Quercetin. Molecules, 2021;26(6):1608. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq IZ. Free Radicals and Oxidative Stress: Signaling Mechanisms, Redox Basis for Human Diseases, and Cell Cycle Regulation. Curr Mol Med, 2023;23(1):13-35. [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu ID; Sarteshnizi RA; Udenigwe CC; Aluko RE. A Concise Review of Current In Vitro Chemical and Cell-Based Antioxidant Assay Methods. Molecules, 2021;26(16):4865. [CrossRef]

- Di Micco R; Krizhanovsky V; Baker D; d'Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence in ageing: from mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2021;22(2):75-95. [CrossRef]

- Fakhri S; Zachariah Moradi S; DeLiberto LK; Bishayee A. Cellular senescence signaling in cancer: A novel therapeutic target to combat human malignancies. Biochem Pharmacol, 2022;199:114989. [CrossRef]

- González-Gualda E; Baker AG; Fruk L; Muñoz-Espín D. A guide to assessing cellular senescence in vitro and in vivo. FEBS J,2021;288(1):56-80. [CrossRef]

- Valieva Y, Ivanova E, Fayzullin A, Kurkov A, Igrunkova A. Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Detection in Pathology. Diagnostics (Basel), 2022;12(10):2309. [CrossRef]

- Chota A; George BP; Abrahamse H. Interactions of multidomain pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins in cancer cell death. Oncotarget, 2021;12(16):1615-1626. [CrossRef]

- Akim AM; Sung YY; Muhammad TST. Cancer and Apoptosis. Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2543:191-210. [CrossRef]

- Ozaki T; Nakagawara A. Role of p53 in Cell Death and Human Cancers. Cancers (Basel),2011;3(1):994-1013. [CrossRef]

- Samatha Jain, M; Makalakshmi, M.K; Deka, D; Pathak, S. and Banerjee, A., 2022. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in Stem Cells for ROS-Induced Cancer Progression. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects (pp. 2133-2151). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A; Rowlo, P; Jothimani, G; Duttaroy, A.K and Pathak, S. Wnt signalling inhibitors potently drive trans-differentiation potential of mesenchymal stem cells towards neuronal lineage. J. Med. Biol. Eng ,2022, 42(5),630-646. [CrossRef]

- Disoma C; Zhou Y; Li S; Peng J; Xia Z. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer: Is therapeutic targeting even possible?. Biochimie, 2022;195:39-53. [CrossRef]

- Neganova ME; Klochkov SG; Aleksandrova YR; Aliev G. Histone modifications in epigenetic regulation of cancer: Perspectives and achieved progress. Semin Cancer Biol, 2022;83:452-471. [CrossRef]

- Pant K; Peixoto E; Richard S; Gradilone SA. Role of Histone Deacetylases in Carcinogenesis: Potential Role in Cholangiocarcinoma. Cells, 2020;9(3):780. [CrossRef]

- Patra S; Panigrahi DP; Praharaj PP; et al. Dysregulation of histone deacetylases in carcinogenesis and tumor progression: a possible link to apoptosis and autophagy. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2019;76(17):3263-3282. [CrossRef]

- Milazzo G; Mercatelli D; Di Muzio G; et al. Histone Deacetylases (HDACs): Evolution, Specificity, Role in Transcriptional Complexes, and Pharmacological Actionability. Genes (Basel), 2020;11(5):556. [CrossRef]

- Argüelles S; Guerrero-Castilla A; Cano M, Muñoz MF; Ayala A. Advantages and disadvantages of apoptosis in the aging process. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2019;1443(1):20-33. [CrossRef]

- Lee HY; Tang DW; Liu CY; Cho EC. A novel HDAC1/2 inhibitor suppresses colorectal cancer through apoptosis induction and cell cycle regulation. Chem Biol Interact, 2022;352:109778. [CrossRef]

- Yang J; Gong C; Ke Q; et al. Insights Into the Function and Clinical Application of HDAC5 in Cancer Management. Front Oncol, 2021;11:661620. [CrossRef]

- Cheng F; Zheng B; Wang J; et al. Histone deacetylase 10, a potential epigenetic target for therapy. Biosci Rep. 2021;41(6):BSR20210462. [CrossRef]

- Alseksek RK; Ramadan WS; Saleh E; El-Awady R. The Role of HDACs in the Response of Cancer Cells to Cellular Stress and the Potential for Therapeutic Intervention. Int J Mol Sci, 2022;23(15):8141. [CrossRef]

- Deka D; Scarpa M; Das A; Pathak S; Banerjee A. Current Understanding of Epigenetics Driven Therapeutic Strategies in Colorectal Cancer Management. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets, 2021;21(10):1882-1894. [CrossRef]

- Jothimani G; Bhatiya M; Pathak S; Paul S; Banerjee A. Tumor Suppressor microRNAs in Gastrointestinal Cancers: A Mini-Review. Recent Adv Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov, 2022;16(1):5-15. [CrossRef]

- Li L; Yu R; Cai T; et al. Effects of immune cells and cytokines on inflammation and immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Int Immunopharmacol, 2020;88:106939. [CrossRef]

- Dash S; Sahu AK; Srivastava A; Chowdhury R; Mukherjee S. Exploring the extensive crosstalk between the antagonistic cytokines- TGF-β and TNF-α in regulating cancer pathogenesis. Cytokine, 2021;138:155348. [CrossRef]

- Teleanu RI; Chircov C; Grumezescu AM; Teleanu DM. Tumor Angiogenesis and Anti-Angiogenic Strategies for Cancer Treatment. J Clin Med, 2019;9(1):84. [CrossRef]

- Rebecca RJ; Janaki CS; Jayaraman S; et al. Carica Papaya Reduces High Fat Diet and Streptozotocin-Induced Development of Inflammation in Adipocyte via IL-1β/IL-6/TNF-α Mediated Signaling Mechanisms in Type-2 Diabetic Rats. Curr Issues Mol Biol, 2023;18;45(2):852-884. [CrossRef]

- Bhat AA; Nisar S; Singh M; et al. Cytokine- and chemokine-induced inflammatory colorectal tumor microenvironment: Emerging avenue for targeted therapy. Cancer Commun (Lond), 2022;42(8):689-715. [CrossRef]

- V A; Nayar PG; Murugesan R; S S; Krishnan J; Ahmed SS. A systems biology and proteomics-based approach identifies SRC and VEGFA as biomarkers in risk factor mediated coronary heart disease. Mol Biosyst, 2016;12(8):2594-2604. [CrossRef]

- Riccardi C; Napolitano E; Platella C; Musumeci D; Melone MAB; Montesarchio D. Anti-VEGF DNA-based aptamers in cancer therapeutics and diagnostics. Med Res Rev, 2021;41(1):464-506. [CrossRef]

- Subbaraj GK; Masoodi T; Yasam SK; et al. Anti-angiogenic effect of nano-formulated water soluble kaempferol and combretastatin in an in vivo chick chorioallantoic membrane model and HUVEC cells. Biomed Pharmacother, 2023;163:114820. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).