1. Introduction

Introduced as concept in 1959, nanotechnology is now considered the most promising technology of the 21st century included in the medical field where nanoparticles may serve as novel diagnostic tools, targeted drug carriers or biomedical implants [

1]. Among various types of nanoparticles, magnetic nanoparticles display unique properties such as diverse physicochemical parameters, easy synthesis, biocompatibility, and stability that render them suitable for biomedical purposes [

2]. Magnetic nanoparticles are formed from metal elements or their oxides; superparamagnetic magnetite (Fe

3O

4) is the most commonly used given its high biocompatibility [

2]. Partial substitution of iron with other metals such as Co, Ni, K, etc. produces ferrites that can be classified according to their crystal structure and magnetic properties; spinel ferrites display the general formula M

2+Fe

23+O

4 and unique multifunctional properties such as strong magnetic behavior, high specific surface area, active sites at the surface allowing further functionalization, chemical stability as well as various shapes and sizes [

3]. Unlike spinel ferrites where the divalent metal ion occupies tetrahedral sites while the iron ion Fe

3+ can be found in octahedral sites, in cobalt ferrites (CoO·Fe

2O

3) the Co

2+ ions are distributed in octahedral sites with the iron ions equally distributed in tetrahedral and octahedral sites which produces an inverse spinel structure [

4] whose properties can be altered through composition and synthesis method.

Cobalt ferrite nanoparticles have been intensively studied due to their specific chemical, physical, electrical and mechanical properties that provide them with unique features which allow their application in various fields [

5]. Unlike iron oxide nanoparticles that are prone to aggregation and oxidation and display renal and liver toxicity through oxidative cell damage following intraperitoneal administration, cobalt ferrite nanoparticles lack such toxic effects even at high doses necessary in hyperthermia [

6]. Although frequently assessed as drug carriers, cobalt ferrites can act as anticancer agents themselves presumably due to their cytotoxic effects after cellular uptake as a result of pH-dependent release of Co

2+ ions [

7]. Moreover, when comparing Co

2+ ions generated by cobalt chloride and cobalt ferrite, respectively, study showed that intrinsic cobalt toxicity prevents its use as monotherapy antitumor agent.

Cobalt ferrite nanoparticles were identified as antiproliferative agents against MCF7 breast cancer cells while lacking cytotoxic effects in HEK-293 human embryonic kidney cells thus displaying selective anticancer activity [

8]. Similar results were reported in HCT-116 human colorectal cancer cells [

9]. Studies show that at low concentrations the nanoparticles accumulate in the perinuclear region within cells; at increased concentrations, Co and Fe are present in the nuclear region triggering cell morphological alterations presumably due to an increased Co/Fe ratio as a result of biodegradation and Co accumulation in the cell nucleus [

10]. However, more studies have been conducted on doped cobalt ferrites with different metal elements in the effort to enhance their properties and therefore their biomedical applications; doping with transitional metals leads to changes in the physical properties depending on the distribution of doping ions between the two interstitial sites of the cobalt ferrite spinel structure as well as on their valence [

11]. Similarly, doping with large size rare earth metals produces significant adjustments in the physico-chemical features of cobalt ferrites such as specific surface area and particle size depending on the type and concentration of the dopant, synthesis method and cation distribution between the tetrahedral and octahedral sites [

12]. Even more important, doping may increase the cytotoxicity of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles in cancer cells; substitution of Fe

2+ with Mn

2+ decreased MCF7 breast cancer cell viability presumably due to oxidative stress [

13].

Rare earth elements or lanthanides exhibit biologic properties similar to those of calcium ions being involved in biomedical studies; they may be used as salts, coordination complexes, radioisotopes or oxides in cancer imagistic and therapy [

14]. Rare earth metal-substituted cobalt ferrites can be easily synthesized and display a pure spinel phase, uniform and narrow particle size distribution; the substitution was able to decrease particle size and coercivity [

15]. The molecular mechanism underlying the anticancer activity of such nanoparticles involves the pore formation within cell membrane, with strong selectivity versus healthy cells being reported; unlike healthy cells, cancer cell exhibits membrane depolarization that enables electroporation thus allowing delivery via induced pores [

16]. Praseodymium (Pr)-doped nanorods decorated with poly-beta-cyclodextrin were synthesized as nanocarriers for the delivery of 5-fluorouracil; they display high-loading efficacy and a strong and selective anticancer activity in MCF7 breast cancer cells [

17].

The aim of the current study was the synthesis of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles doped with praseodymium and their assessment as anticancer agents; the nanoparticles were physiochemically analyzed and tested thereafter on normal HaCaT cells and on A375, MCF-7 and HT-29 cancer cells. The biological assessment revealed that all compounds displayed a strong dose-dependent cytotoxic activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

The raw materials used for synthetic purposes were iron nitrate nanohydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, Merck), cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O, Sigma-Aldrich), dysprosium chloride x hydrate (PrCl3·xH2O, Sigma-Aldrich), glycine (C2H5NO2, Merck), (2-Hydroxypropyl)-γ-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich) and absolute ethanol (Merck).

2.2. Synthesis by Combustion Method

In order to synthesize 0.02 moles of cobalt ferrite, 0.04 moles iron nitrate, 0.02 moles cobalt nitrate and 0.09 mole of glycine were used; glycine acted as fuel while the nitrates functioned as oxidizing agent. The salts and the glycine were heated together at 60°C until the formation of a brown solution. Meanwhile, a porcelain capsule was preheated at around 350°C using a heating mantle. The mixture was then carefully poured in the capsule and the heating mantle was kept running at 350°C. After the entire water evaporated, the mixture became viscous and at some point, self-ignited. The combustion front propagated very fast in the entire mass, the reaction completing in around 9 seconds. During the reaction yellow flames indicating high temperature were observed; a black and crumbly powder formed as a result.

The praseodymium doped cobalt ferrite was synthesized following the same procedure but adding an extra step when praseodymium chloride was added into the mixture. The amount of cobalt nitrate (0.02 moles) and glycine (0.09 moles) remained unchanged while the praseodymium and iron nitrate quantities were varied. The Pr and Fe salts used are presented in

Table 1. Regarding the reaction development, it is worth noted that white gases were released, the duration increased with 3-4 seconds and the final powder exhibited a more voluminous, spongy texture compared to the undoped sample.

The powders of both doped and undoped cobalt ferrite were washed several times using warm water, then dried and manually grinded in a mortar until a very fine powder is obtained.

2.3. Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex

In order to enable biological evaluation, all samples were incorporated into (2-hydroxypropyl)-γ-cyclodextrin which has the ability to increase their water solubility; a molar ratio of 1:1 cyclodextrin:cobalt ferrite was used. Homogenization was accomplished by using a solvent composed of 0.9 ml distilled water and 2.1 ml absolute ethanol. Further, the mixture was stirred for 30 minutes and then dried at 70°C until full solvent evaporation. The resulting complex was then manually grinded into a fine powder that was later suspended in distilled water by using a UP200S ultrasonic homogenizer (Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH, Teltow, Germany) for 2 hours at 50% amplitude and 0.8 cycles. After sonication, the particles remained suspended without the occurrence of sediments.

2.4. Characterization Methods

The investigation regarding sample phase composition was conducted through X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis by means of a Rigaku Ultima IV device (Tokyo, Japan) operating at 40 kV and 40 mA; the XRD pattern was achieved by utilizing CuKα radiation. The FTIR spectra were obtained using KBr pellets on a Shimadzu IR Affinity-1S spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments Inc., Columbia, MD, USA) operating between 400 and 4000 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1. Magnetic measurements were performed at room temperature on a LakeShore 8607 vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, Shore Cryotronics, Westerville, OH, USA) at a magnetic field ranging between 30 and -30 KOe; prior to each test, samples were demagnetized in alternating field. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed on a Verios G4 UC Scanning Electron Microscope (Thermo Scientific, Czech Republic). The samples were coated prior to examination with 6 nm platinum using a Leica EM ACE200 Sputter coater in order to increase electrical conductivity and reduce charge buildup. SEM investigations were performed in High Vacuum mode using a detector for high-resolution images (Through Lens Detector, TLD) at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. Morphological characterization was conducted in high contrast mode at 120 kV acceleration voltage on a Hitachi High-Tech HT7700 (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The instrument is equipped with a STEM module, an energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) detector that allows elemental analysis and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) apertures that could be used to collect diffraction patterns. The samples were prepared by drop casting from their water suspension on 300 mesh carbon-coated copper grids (Ted Pella) and vacuum-dried at room temperature for 24 h.

2.5. Cell Culture

Immortalized human keratinocytes HaCaT (CLS Cell Lines Service GmbH, Eppelheim, Germany), human melanoma cells A375, human breast adenocarcinoma cells MCF-7 and human colorectal adenocarcinoma HT-29 cells (American Type Culture Collection ATTC, Lomianki, Poland) were used in the current study. HaCaT and A375 cells were cultured on Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) high glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% mixture of penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL). McCoy’s 5A supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic mixture was employed for culturing the HT-29 cell line, while MCF-7 cells were cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) containing the same concentrations of FBS, antibiotic mixture and 0.01 mg/mL human recombinant insulin. All cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

2.6. Cell Viability Assessment

The Alamar blue colorimetric assay was employed to determine the cell viability percentages of HaCaT, A375, MCF-7 and HT-29 cells after stimulation with increasing concentrations (0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL) of the newly synthesized compounds for 48h. The cells (1 x 104) were seeded onto 96-well plates and incubated until reaching 85-90% confluence. The old medium was removed using an aspiration station and then replaced with fresh medium containing the tested concentrations of each compound. After 48h, 20 μL Alamar blue 0.01% was added to each well and the cells were further incubated for another 3h. To determine cell population, the absorbance of the wells was determined at two wavelengths, 570 nm and 600 nm, using a microplate reader (xMarkTM Microplate, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicates.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism version 6.0.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) were used in order to assess statistical significance; the differences between the groups were considered statistically significant if p< 0.05, as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

In the current study we aimed to achieve the synthesis of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles doped with praseodymium in the effort to identify therapeutic alternatives to fight melanoma, colorectal adenocarcinoma and breast cancer. Although conventional therapies that combine cancer staging with a multitude of strategies (chemotherapy, radiation, surgery) can produce satisfying outcomes for a limited period of time, they also come with severe side effects due to lack of selectivity and may also induce drug resistance. Additionally, conventional anticancer drugs may exhibit poor pharmacokinetic profiles that may be associated with partial lack of efficacy or toxicity. Such challenges can be overcome by using nanoformulations that provide benefits in terms of bioavailability, stability and administration [

18]. Among the huge number of metallic nanoparticles, cobalt ferrites have gained increased interest due to their high coercivity at room temperature combined with moderate magnetization [

19]. Cobalt ferrites are spinel nanoparticles that have been tested as therapeutic agents both as drug carriers as well as hyperthermia agents [

20]; however, their intrinsic anticancer properties were poorly investigated so far. One such study revealed their ability to reduce viability in MCF7 breast cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner with stronger effects compared to magnesium-doped cobalt ferrites [

21]. Such effects could be triggered by the intrinsic toxicity of cobalt ions that may act as cytotoxic agents following their release as a result of lysosome degradation of the cobalt ferrite nanoparticle in an acid environment [

21]. The use of cobalt ferrites as anticancer agents is therefore worthy of investigation particularly considering their ability to combine heat and cytotoxic effects into one single platform. Moreover, the introduction of small amounts of rare earth metals into the lattice of cobalt ferrites can tune their magnetic, electronic and cytotoxic properties presumably due to the complex interactions between the 3d cation orbitals and 2p oxygen orbitals as a result of metal distribution over the tetragonal and octahedral positions [

22]. Based on previous promising results with dysprosium doping [

4], we chose to prepare praseodymium-doped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles whose physicochemical and biological analysis was conducted; their low water solubility introduced the challenge of facilitating their uptake by the aqueous biological medium which was solved by adding the hydrophilic HPGCD.

A multitude of synthetic approaches have been designed to achieve cobalt ferrite nanoparticle, including sol-gel emulsion or auto-combustion, co-precipitation, gamma-irradiation, microwave mediated, hydrothermal, thermal decomposition [

23], displaying various challenges such as the use of toxic reagents or uncontrollable properties of the resulting nanoparticles. The combustion method used in the current study provides undisputable advantages in terms of feasibility (single-step method, easily applicable and not expensive) but also quality of the final product: high crystallinity, homogenous ferrites where the intrinsic energy of the components enable the occurrence of metastable phases in one step [

24]. Additionally, through controlling the reaction parameters, one can modulate the properties of the final nanoparticles [

25].

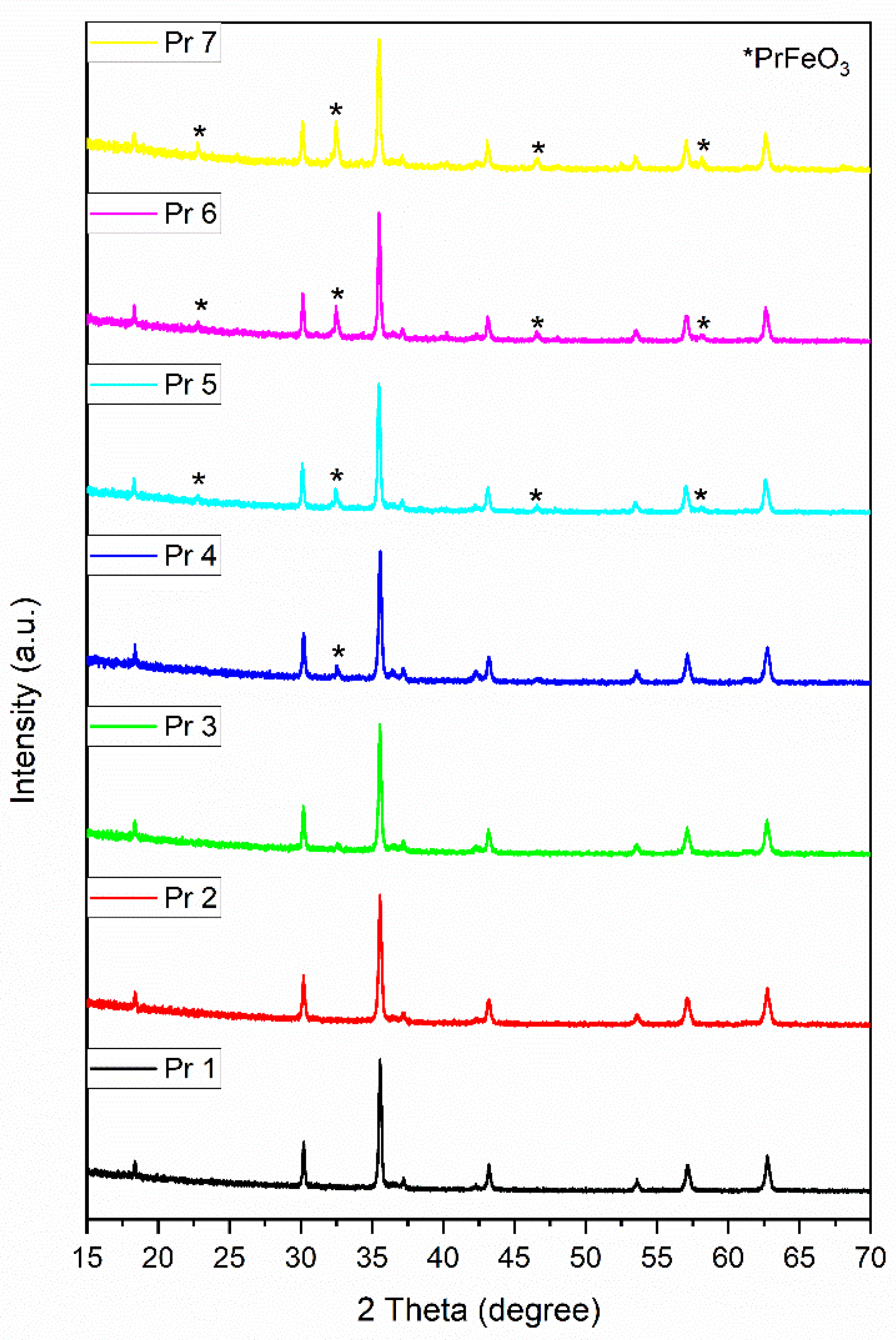

The X-ray diffraction analysis revealed the formation of cubic cobalt ferrite and the successful incorporation of praseodymium in the ferrite structure. Dheeraj Yadav et al. [

26] investigated the influence of the annealing temperature on cobalt ferrite formation. They identified the cobalt ferrite using the JCPDS file 22-1086; on the XRD spectra, the most intense maximum diffractions were located at 2θ values similar to the ones observed in the current work (e.g., 35.55° vs. 35.59°). Also, the allocated crystallographic planes were identical to our case. The same JCPDS file was employed in other studies [

27,

28,

29,

30] for the identification of the spinel structure.

In our study, the synthesis of CoFe

2-yPryO

4 led to the formation of single phase for samples Pr 1, Pr 2, Pr 3 and Pr 4 (y=0; 0.01; 0.03; 0.05, respectively), and to the occurrence of a secondary phase for samples Pr 5, Pr 6 and Pr 7 (y=0.1; 0.15; 0.2, respectively). Of note, the formation of the secondary phase did not produce a visible decrease of the peak intensity in praseodymium-doped cobalt ferrites. The secondary phase, orthorhombic perovskite PrFeO

3 was identified using the JCPDS card 047-0065 which was also used in other studies for similar purposes [

31,

32].

Our results are in agreement with those reported by Pachpinde et al. [

33] who synthetized PrxCoFe

2-xO

4 (x=0 – 0.1) by sol-gel auto combustion method using citric acid and nitrates as precursors; results showed that for x˂0.05 praseodymium was successfully incorporated into the ferrite lattice while for values above 0.05, a secondary phase of perovskite PrFeO

3was found alongside the cubic cobalt ferrite. An explanation for the occurrence of the secondary phase was provided by Nikmanesh et al. [

28] who investigated the effect of praseodymium doping on the cobalt ferrite structure; a sol-gel auto combustion method was used for the synthesis of CoFe

2−xPrxO

4 (x = 0, 0.02, 0.04, 0.06). The research focused on the synthesis and thorough investigation of the impact provided by iron substitution with a lanthanide upon the spinel lattice; a secondary phase of PrFeO

3 occurred for x=0.06 as revealed by the two diffraction peaks located at 32.56° and 46.68° in the XRD spectra, values similar to the ones recorded in our study. The authors hypothesized that such a secondary phase can be a result of the difference between the ionic radius of iron and substituting praseodymium; similar conclusions were drawn in other studies where various lanthanides were doped in ferrite structures [

34,

35,

36].

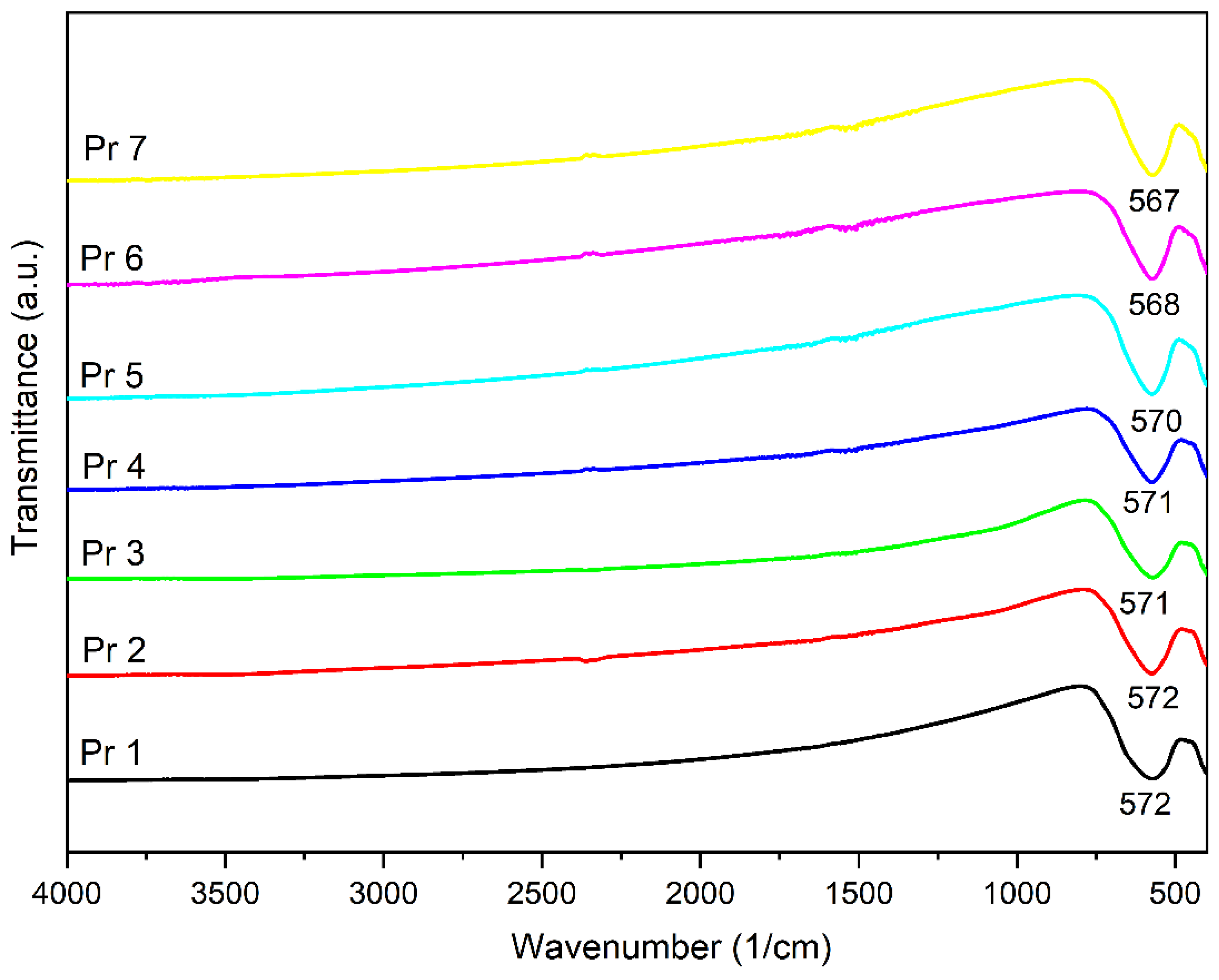

In the next step, the FTIR spectra were built, revealing a strong absorption band around 570 cm-1 in each investigated sample, with a shoulder present around 400 cm-1, characteristic for the stretching vibrations attributed to the tetrahedral vibration (metal-oxygen in site A) and the octahedral vibration (metal-oxygen in site B), respectively [

37]. In a series of trivalent ions of rare earth metals (Gd, Sm, Ho, Er, Yb, Y) used as dopants for cobalt ferrite, Jing et al. [

35] emphasized that the absorption band around 570 cm

-1 shifts to higher wavenumbers for samarium, holmium, erbium, ytterbium and yttrium while for gadolinium the shift occurs towards lower wavenumbers. Moreover, they assigned the 570 cm

-1 band to the tetrahedral stretching vibration between metal and oxygen, and the second band to the octahedral stretching vibration between metal and oxygen. Additionally, the samples that contain praseodymium exhibited a shift towards lower wavenumbers, e.g., 567 cm

-1 in Pr 7. A similar observation was previously reported in praseodymium-doped cobalt ferrite [

33] as well as in dysprosium-doped cobalt ferrite [

4], were the wavenumber decreased with the increase of the rare earth metal substitution. The replacement of iron by praseodymium, with larger ionic radius, results in an increased unit cell dimensions and alters the iron-oxygen vibrations thus leading to change in band positions. The peak intensity also changes with an increased Pr

3+ substitution; the change in the frequency of the second stretching band points to the preferred orientation of Pr

3+ ions towards octahedral sites. Also, the slight decrease of the second band frequency may be attributed to the presence of the secondary phase in samples with higher Pr

3+ substitution level [

33].

The VSM analysis revealed that the presence of praseodymium in the ferrite lattice reduced the Ms and Mr values, particularly in samples where cyclodextrin was used as coating material; such intense magnetization reduction can be attributed to the large amount of cyclodextrin that lacks magnetic behavior and is able to shield the intrinsic magnetic properties of the included ferrite. Similar data was reported in samples of CoFe

2−xPrxO

4 (x = 0, 0.02, 0.04, 0.06) [

28] where the Ms values decreased with the increase of praseodymium content; as an example, for x=0, Ms was around 80 emu/g and reached 60 emu/g for x=0.06. In our study, the Ms value for x=0 was around 73 emu/g and dropped to 66 emu/g for x=0.05. Vani et al. [

30] studied the effect of terbium ions (Tb

3+) on the cobalt ferrite structure and properties; they reached a similar conclusion in terms of magnetic properties, reporting that the value of Ms decreases with the increase of terbium concentration in the sample presumably due to the substitution of the highly magnetic iron with the less magnetic terbium. Such conclusions were supported by other studies on rare earth metal-doped cobalt ferrites where the values of both Ms and Mr could be clearly correlated with the content of the doping material [

4,

38,

39].

The aspect of the samples illustrated in the SEM images, a sponge, foam-like cavernous structure is typical for the cobalt ferrite obtained by combustion synthesis. Similar morphological features were previously presented by Qing et al. [

40] in the case of gadolinium doped cobalt ferrite and Abbas et al. [

41] for aluminum doped cobalt ferrite, both prepared by sol-gel autocombustion method. Although, the SEM images are comparable for the undoped and doped samples, in the case of TEM images can be clearly noticed that the presence of the dopant influences the particle dimensions and shape. In addition, the images present a tendency of particle agglomeration or even superposition. In our case, was observed an increase of particle size with the increase of dopant quantity, starting from a range of 24-64 nm for the pure sample going towards 120-245 nm for sample Pr 7, that has the highest amount of dopant. Similar findings were presented by Yadav et al. [

42] in the study regarding the synthesis of CoFe

2−xPrxO

4 (x = 0.0, 0.025, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1) using starch-assisted sol–gel autocombustion. Starting with a range of 5-10 nm for the undoped sample, the particles dimension doubled in size for a content of praseodymium of 0.075. Manikandan et al. [

43] synthesized by chemical oxidation method pure and doped cobalt ferrite, using praseodymium in different ratios between 0% - 5%. The FESEM results indicated spherical particles with a range between 30 to 160 nm in the case of pure sample. When praseodymium was added into the sample, and the doping percentage increased up to 5%, was remarked an increase of particle size ranging from 70 to 200 nm. Furthermore, in the case of zinc-cobalt ferrite [

44] was observed an increase in particle dimension and altering of particle shape after praseodymium doping. Comparable findings were presented in the case of gadolinium doped cobalt ferrite CoFe

2−xGdxO

4 (x=0-0.30) [

45].

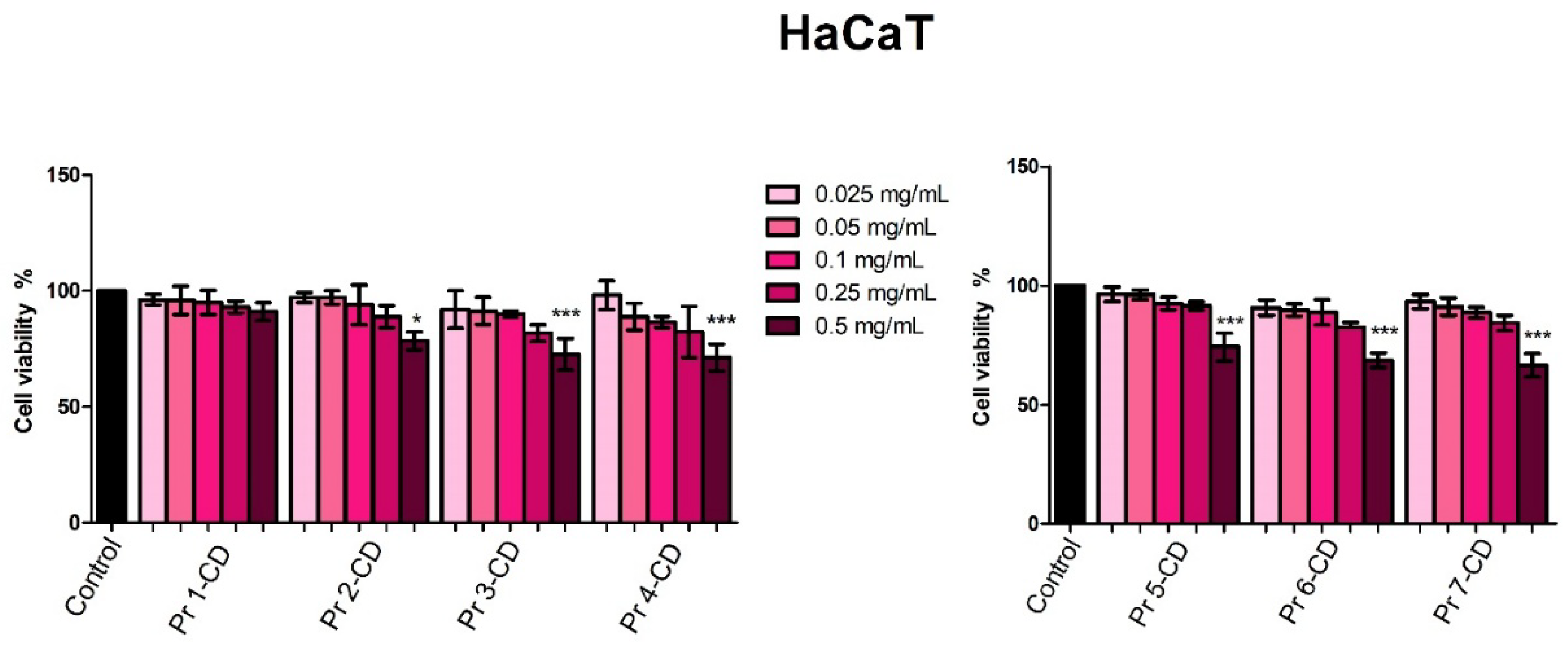

The biological evaluation of the newly synthetized Pr-doped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles as cyclodextrin inclusion complexes was conducted both on normal human keratinocytes cell line and three cancer cell lines, namely human melanoma, human breast adenocarcinoma and human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell lines. This strategy provides insights on the efficacy of the tested samples as anticancer agents while investigating their selectivity. Reference to previously reported data is challenging since, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first biological evaluation of Pr-doped CoFe

2O

4 nanoparticles. The biological assessment in HaCaT normal human keratinocytes revealed that the tested compounds exhibited low cytotoxic, dose-dependent activity; thus, an antiproliferative activity was only displayed when the highest concentration (0.5 mg/mL) of the tested compounds was applied. Moreover, taken together with the high IC

50 values (> 0.5 mg/mL) obtained, the results indicate a high biocompatibility of tested compounds as well as their potential selective anticancer activity which stands as an important parameter in the development of new anticancer agents. The high biocompatibility of our compounds when tested in HaCat cells are also in line with previous data on cobalt ferrite nanoparticles that reported low cytotoxicity even at concentrations of 2 mg/mL [

46], with significant reductions in cell viability only at concentrations as high as 4 mg/mL combined with 72 and 96 h incubation time [

46].

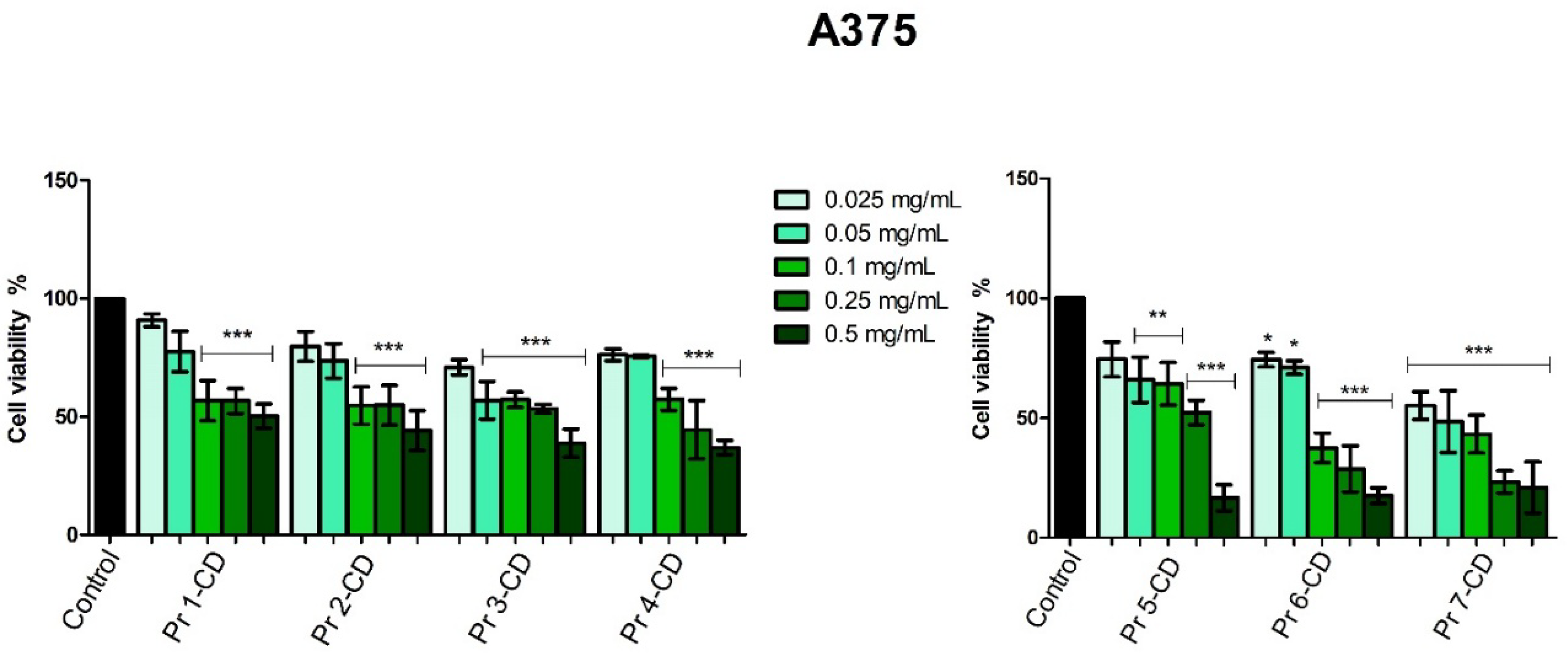

The evaluation of Pr-doped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles cytotoxic effects in A375 human melanoma cells disclosed a dose-dependent antiproliferative activity notably after treatment with the highest concentration of each compound (0.5 mg/mL). The intensity of the cell viability inhibitory activity correlates with the amount of Pr in the tested cobalt ferrite nanoparticles; the cytotoxic activity of the tested compounds increased exponentially with the amount of Pr. The role of Pr in exerting the inhibitory effect is obvious when comparing the doped cobalt ferrites to the undoped ones, in all tested concentrations (e.g., Pr 1-CD vs. Pr 2-CD). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first assessment of Pr-doped cobalt ferrites as anticancer agents; however, we previously conducted similar studies on Dy-doped CoFe

2O

4 nanoparticles that revealed a dose-dependent cytotoxic activity against the A375 cell line which was also correlated to the amount of dysprosium used as substitution for the iron ions [

4]. Cobalt ferrite nanoparticles were also previously investigated for magnetic hyperthermia and light-based treatments in the eradication of cancer stem cells in A375 cell line, displaying effective cytotoxicity with IC

50 values of 0.025 mg/ml [

47].

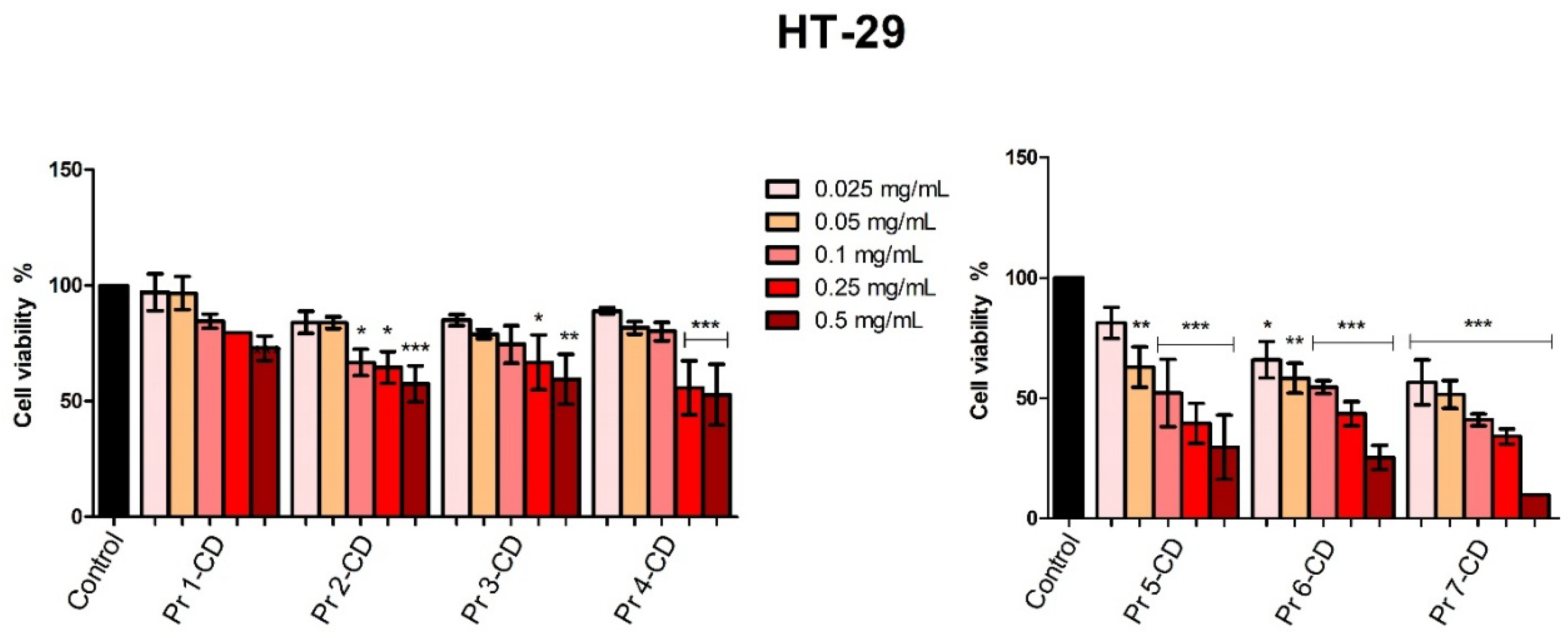

The antiproliferative activity of the tested compounds was confirmed in HT-29 colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line. When tested in the highest concentration, all compounds displayed a strong dose-dependent cytotoxic activity. Compounds Pr 5-CD and notably Pr 6-CD exhibited exponential cytotoxicity in correlation to an increased praseodymium substitution, with cell viability values of 29.54% and 25.28% respectively. Pr 7-CD exhibited the strongest antiproliferative activity in all tested concentrations, decreasing HT-29 cell viability to 9.28% when tested in the highest concentration, presumably due to its high amount of Pr. As we stated previously, we were not able to find another attempt to assess the anticancer activity of Pr-doped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles; however, in a similar study, Pr-substituted Ni-Co nano-spinel ferrites exhibited efficient cell viability inhibition in HCT-116 colorectal carcinoma cells, displaying an average inhibitory activity of 50% [

16]. Moreover, Nd

3+ and Ce

3+ co-substituted Co ferrite nanoparticles were tested on the same colorectal carcinoma cell line, results indicating significantly reduced cell viability through dose-dependent apoptotic effects [

48].

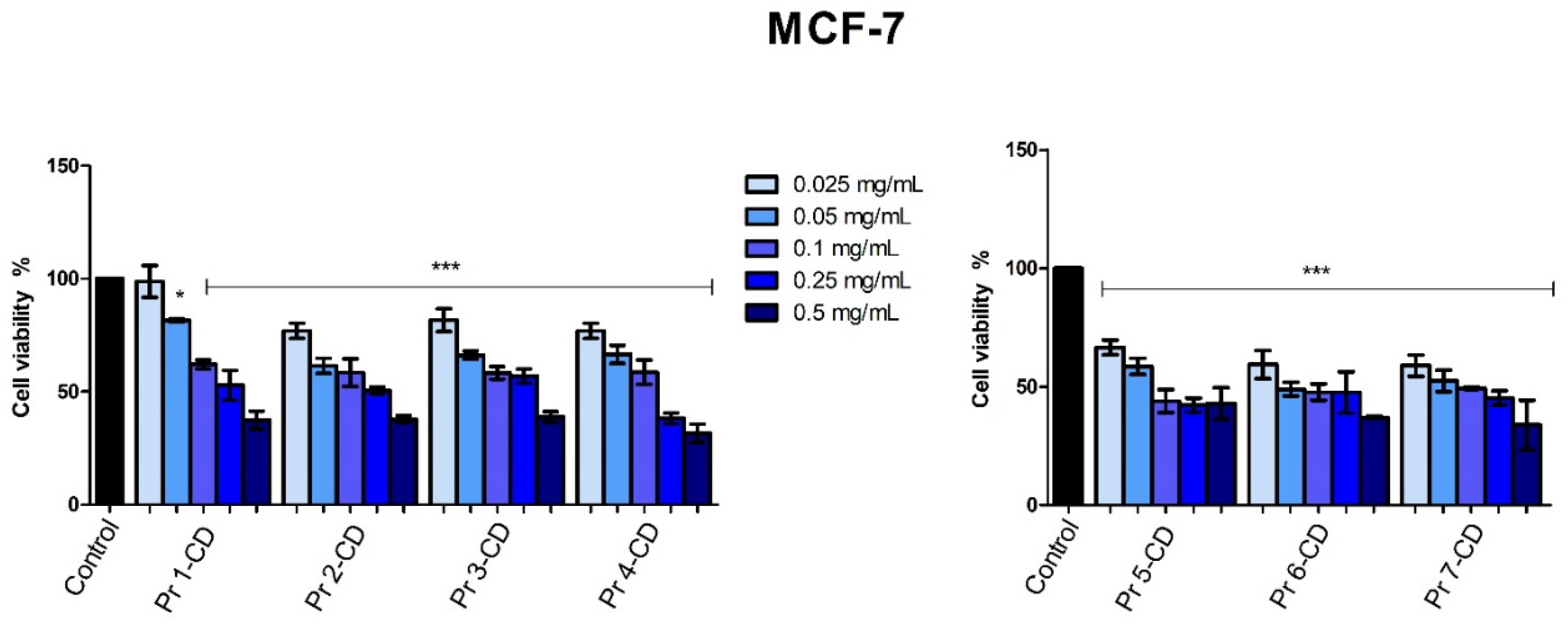

When tested on the MCF-7 breast adenocarcinoma cell line, all compounds displayed a dose-dependent antiproliferative activity, with IC

50 values ranging from 0.08 to 0.32 (

Table 2). The cytotoxic activity in MCF-7 cells is more evident when compared to results on the HaCaT cell line, where an IC

50 value >0.5 was obtained for all compounds, thus emphasizing the selectivity of the tested compounds against MCF-7 cells. An overview of cell viability inhibition in all tested cancer cell lines, with respect to their IC

50 values (

Table 2), revealed that the MCF-7 cell line was the most responsive to the antiproliferative effect exerted by the Pr-doped CoFe

2O

4 nanoparticles. When compared to our previous results on Dy-doped CoFe

2O

4 nanoparticles, the Pr-doped CoFe

2O

4 nanoparticles displayed higher cytotoxicity, reducing MCF-7 cell viability to less than 50% when using half the concentration [

4]. Pr-metal nanorods coated with poly-CD polymer were synthesized as carrier for 5-fluorouracil and investigated in terms of their anticancer potential against the MCF-7 cell line; they were revealed as a suitable vehicle while providing sustained release for the incorporated drug [

17]. Also, cobalt ferrites were investigated as drug carriers in MCF-7 cells; one study involved the use of cobalt ferrites for the delivery of docetaxel where an intrinsic cytotoxicity of the bare nanoparticles was reported [

49]. Conversely, another study where the cobalt ferrite nanoparticles were used as carriers for letrozole revealed the absence of cytotoxicity of the bare nanoparticles in breast cancer cells; however, an additional coating with methionine was applied in this case which might have increased their physiological acceptance [

50]. In addition, cobalt ferrite nanoparticles demonstrated a mild anti-proliferative activity against MCF-7 cancer cell line promoting a mean viability of 74-85% viability in all tested concentrations [

51]. It is important to note however that the enhanced inhibitory activity of Pr-doped cobalt ferrites could be previewed if considering the promising results reported by Andiappan et al. when investigating the anticancer effects of Pr-doped Schiff bases in several cancer cells; they revealed that the metal ions (Pr

3+) exhibited strong affinity for the cell walls thus leading to DNA fragmentation and arresting cell proliferation [

52]. Additionally, a polymeric quadrivalent praseodymium complex was tested in seven cancer cell lines and, although weaker than conventional anticancer agents, they induced cytotoxic effects in all types of cancer cells but particularly in A375 melanoma cells [

53]. Exposure of cancer cells to low concentrations of a small coordinated complex of Pr and pyrithione significantly diminishes cell survival regardless of drug-resistant phenotype by affecting the cell waste clearing mechanisms as well as mitochondrial metabolism [

54]. Collectively, our data corroborate with previously published results in terms of the anticancer effects of both Pr and cobalt ferrites thus emphasizing the potential of Pr-doped nanoparticles to act as an effective alternative to conventional treatments.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of the samples.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of the samples.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the samples.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the samples.

Figure 3.

Magnetic hysteresis of samples.

Figure 3.

Magnetic hysteresis of samples.

Figure 4.

SEM of the samples.

Figure 4.

SEM of the samples.

Figure 5.

TEM of the samples.

Figure 5.

TEM of the samples.

Figure 6.

HaCaT cell viability 48h post-treatment with Pr 1-CD, Pr 2-CD, Pr 3-CD, Pr 4-CD, Pr 5-CD, Pr 6-CD and Pr 7-CD (0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL). The results are expressed as viability percentages compared to the control group (100%) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01). The data represents the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Figure 6.

HaCaT cell viability 48h post-treatment with Pr 1-CD, Pr 2-CD, Pr 3-CD, Pr 4-CD, Pr 5-CD, Pr 6-CD and Pr 7-CD (0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL). The results are expressed as viability percentages compared to the control group (100%) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01). The data represents the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Figure 7.

A375 cell viability 48h post-treatment with Pr 1-CD, Pr 2-CD, Pr 3-CD, Pr 4-CD, Pr 5-CD, Pr 6-CD and Pr 7-CD (0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL). The results are expressed as viability percentages compared to the control group (100%) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). The data represents the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Figure 7.

A375 cell viability 48h post-treatment with Pr 1-CD, Pr 2-CD, Pr 3-CD, Pr 4-CD, Pr 5-CD, Pr 6-CD and Pr 7-CD (0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL). The results are expressed as viability percentages compared to the control group (100%) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). The data represents the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Figure 8.

HT-29 cell viability 48h post-treatment with Pr 1-CD, Pr 2-CD, Pr 3-CD, Pr 4-CD, Pr 5-CD, Pr 6-CD and Pr 7-CD (0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL). The results are expressed as viability percentages compared to the control group (100%) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). The data represents the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Figure 8.

HT-29 cell viability 48h post-treatment with Pr 1-CD, Pr 2-CD, Pr 3-CD, Pr 4-CD, Pr 5-CD, Pr 6-CD and Pr 7-CD (0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL). The results are expressed as viability percentages compared to the control group (100%) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). The data represents the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Figure 9.

MCF-7 cell viability 48h post-treatment with Pr 1-CD, Pr 2-CD, Pr 3-CD, Pr 4-CD, Pr 5-CD, Pr 6-CD and Pr 7-CD (0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL). The results are expressed as viability percentages compared to the control group (100%) (* p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001). The data represents the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Figure 9.

MCF-7 cell viability 48h post-treatment with Pr 1-CD, Pr 2-CD, Pr 3-CD, Pr 4-CD, Pr 5-CD, Pr 6-CD and Pr 7-CD (0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL). The results are expressed as viability percentages compared to the control group (100%) (* p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001). The data represents the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Table 1.

Sample composition.

Table 1.

Sample composition.

| Sample |

PrCl3·xH2O (moles) |

Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (moles) |

| Pr1 |

- |

0.0400 |

| Pr2 |

0.0002 |

0.0398 |

| Pr3 |

0.0006 |

0.0394 |

| Pr4 |

0.0010 |

0.0390 |

| Pr5 |

0.0020 |

0.0380 |

| Pr6 |

0.0030 |

0.0370 |

| Pr7 |

0.0040 |

0.0360 |

Table 2.

The calculated IC50 values (mg/mL) of Pr 1-CD, Pr 2-CD, Pr 3-CD, Pr 4-CD, Pr 5-CD, Pr 6-CD and Pr 7-CD on HaCaT, A375, HT-29 and MCF-7 cell lines 48h post-stimulation.

Table 2.

The calculated IC50 values (mg/mL) of Pr 1-CD, Pr 2-CD, Pr 3-CD, Pr 4-CD, Pr 5-CD, Pr 6-CD and Pr 7-CD on HaCaT, A375, HT-29 and MCF-7 cell lines 48h post-stimulation.

| Compound |

HaCaT |

A375 |

HT-29 |

MCF-7 |

| Pr 1-CD |

> 0.5 |

> 0.5 |

> 0.5 |

0.25 |

| Pr 2-CD |

> 0.5 |

0.28 |

> 0.5 |

0.19 |

| Pr 3-CD |

> 0.5 |

0.20 |

> 0.5 |

0.32 |

| Pr 4-CD |

> 0.5 |

0.18 |

> 0.5 |

0.14 |

| Pr 5-CD |

> 0.5 |

0.22 |

0.13 |

0.12 |

| Pr 6-CD |

> 0.5 |

0.08 |

0.17 |

0.08 |

| Pr 7-CD |

> 0.5 |

0.05 |

0.049 |

0.08 |