1. Introduction

Malignant pathologies stand today as the main leading cause of death worldwide; despite huge improvements in anticancer therapy, modern medicine still lack the tools to avoid drug resistance or the severe side effects that accompany current treatments. Therefore, the search for new therapeutic alternatives continues, including materials of various origins. Nanotechnology has established itself in the biomedical field as a powerful weapon against various pathologies, including cancer, where it provided both therapeutic and diagnostic agents, sometimes combined in multifunctional platforms.

Among the multitude of nanoparticles synthesized to date, metallic nanoparticles carry particular importance due to their tunable properties, flexible surface functionalization and straightforward synthetic approach. Metallic nanoparticles can be obtained in a variety of size range with low dispersity indexes, are biocompatible and inert, are able to penetrate the target organs by crossing biological barriers and, more importantly, may induce an enhanced biological activity due to their specific particle size (<100 nm) and high surface area that enable their binding to cellular compounds such as proteins and nucleic acids [

1].

Magnetic nanoparticles have gained interest in the biomedical area due to their ability to be manipulated through an external magnetic field to generate heat which increases tumor temperature above the normal body temperature thus leading to its elimination (hyperthermia); this effect can be combined with drug delivery within multipurposed platforms with high anticancer efficiency [

2]. However, the intrinsic cytotoxic activity of such nanoparticles was also explored and revealed that cancer cells are more sensitive to metallic nanoparticles than normal cells. Mechanisms suggested for such effects include the generation of reactive oxygen species, the activation of caspase 3, the increase of mitochondrial permeability and the fragmentation of DNA molecules, overall activating various signaling pathways that lead to cell death [

3]. Numerous evidences suggest that nanoparticles, particularly iron oxide-based, are able to interact with the host immune system thus stimulating the immune recognition of the tumor through yet unknown mechanisms [

4]. Iron oxide nanoparticles can be doped with other elements that occupy various positions in the crystal lattice and induce the alteration of their resulting physicochemical, biological, electrical and optical properties [

5]. A challenge in obtaining doped iron oxide nanoparticles useful for the biomedical field is to find an element with strong magnetic properties combined with stability and biocompatibility; a strategy was to replace divalent iron ions with cobalt ions which are more anisotropic and display comparable ionic size [

6]. Cobalt-doped iron oxide nanoparticles also known as cobalt ferrites, possess high intrinsic magneto crystalline anisotropy values which trigger significant higher coercivity compared to pure iron oxide nanoparticles. Unlike other ferrites, cobalt ferrite exhibits an inverse spinel structure with divalent ions occupying octahedral sites in the crystal lattice while trivalent ions are distributed evenly between tetrahedral and octahedral sites [

7]. Cobalt is an interesting choice as a doping element given its intrinsic cytotoxic properties; cobalt nanoparticles were tested against breast and colon cancer cells where they easily penetrated cell membrane and induced cell apoptosis and death in a significant proportion while inducing low cytotoxic effects in healthy cells even at high concentrations [

8].

The doping process may go even further by employing rare earth elements as supplementary material in an effort to increase anticancer efficiency. Various rare earth metals were assessed among which Nd stands as one of the most widely studied in terms of bio-imaging applications due to its excitation and emission lines within the first NIR biological transparency window [

9]. Nd also displays intrinsic anticancer properties by binding to double-stranded DNA with high equilibrium association constants; additionally, Nd in high concentration is able to induce the strong condensation of the DNA’s double helix thus promoting its collapse in a similar manner with conventional chemotherapy agents [

10]. However, studies on Nd-doped cobalt ferrites are still scarce particularly in terms of molecular underlying mechanisms.

We aimed to develop Nd-doped cobalt ferrites by means of combustion, a straightforward synthetic approach. The doped ferrites were then assessed in terms of physicochemical properties by employing X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) and scanning transmitted electron microscopy (STEM) analysis. Their biological assessment was carried out using Alamar Blue and LDH release assays on normal HaCaT cell line and on cancer cell lines (A375, MCF-7, and PANC-1), complemented by immunofluorescence staining to evaluate the morphological changes that were associated with the cytotoxic effects.

4. Discussions

Metal nanoparticles are a hot topic in anticancer research, a pathology that continues to raise worldwide challenges in terms of morbidity and mortality. Among such nanoparticles, cobalt ferrites triggered numerous studies due to their potential as both imagistic and therapeutic agents. The current study aimed to investigate the newly synthesized Nd-doped cobalt ferrites which should hypothetically benefit of the anticancer properties of all components. Cobalt ferrites have already been proven as promising, highly selective anticancer agents that simultaneously display the ability to act as a platform for deciphering and controlling magnetic properties through structural chemistry manipulation [

14].

Additionally, Nd has the ability to interact with organic molecules resulting in stable complexes with high biocompatibility; its complex with phenantroline exhibited strong and selective cytotoxic effects [

15]. Similarly, Nd formed a stable complex with tungstogermanate and 5-fluorouracil which exhibited significant cytotoxic activity against two cancer cell lines where pure 5-fluorouracil induced lower anticancer effects [

16].

We aimed to synthesize Nd-doped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles that were further physiochemically analyzed by employing specific procedures.

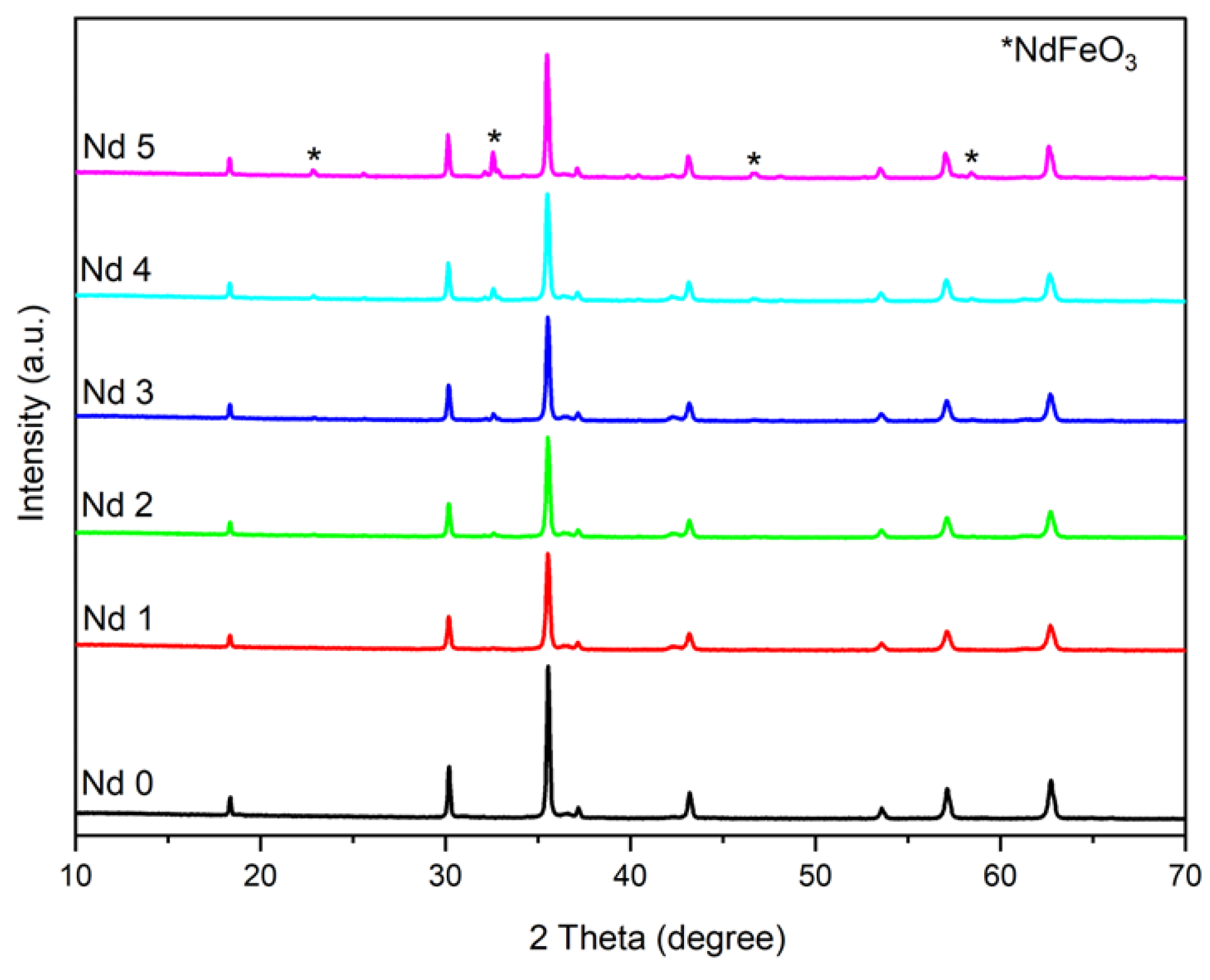

The XRD analysis shows the successful incorporation of Nd within the cubic network. The combustion method used in this case for the synthesis of doped and undoped cobalt ferrite ensured optimal conditions for the formation of single-phase cubic CoFe

2-zNd

zO

4 (Fd3m group) in samples Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (z = 0; 0.01 and 0.02, respectively). The formation of a secondary orthorhombic phase NdFeO

3 (Pbnm group) was reported in samples Nd3 – Nd5 (z = 0.03; 0.05; 0.1, respectively). Furthermore, in sample Nd3 (z = 0.03) only a small peak was noticed, suggesting a trace amount of the secondary phase which did not alter the characteristic patterns of the Nd-doped cobalt ferrite in terms of position and intensity. Muskan et al. [

17] also reported the formation of the orthoferrite NdFeO

3 as secondary phase in their study that focused on CoNd

xFe

2-xO

4 (x = 0.0 - 0.6) nanoparticles.

Our findings are similar to those reported by Wang et al. [

18] who used nitrates, citric acid and the sol–gel self-propagating method to synthesize CoNd

xFe

2-xO

4 (0 ≤ x ≤0.2) nanoparticles. They showed that a doping amount of Nd that exceeded x=0.05 led to the formation of NdFeO

3 secondary phase in addition to the cubic cobalt ferrite. In another study focused on Nd-doped cobalt ferrite, Muskan et al. [

19] identified x=0.05 as the molar ratio that led to the formation of a secondary phase. In the current study, we synthesized CoFe

2-zNd

zO

4 nanoparticles and the presence of NdFeO

3 as secondary phase was confirmed for z=0.05 while only traces were present for z=0.03. The occurrence of the secondary phase can be explained by the difference in the ionic radius between elements, the larger ionic radius (1.07 Å) Nd substituting the smaller ionic radius (0.64 Å) iron within the crystal lattice. Therefore, only a limited amount of Nd will be accommodated into the spinel structure.

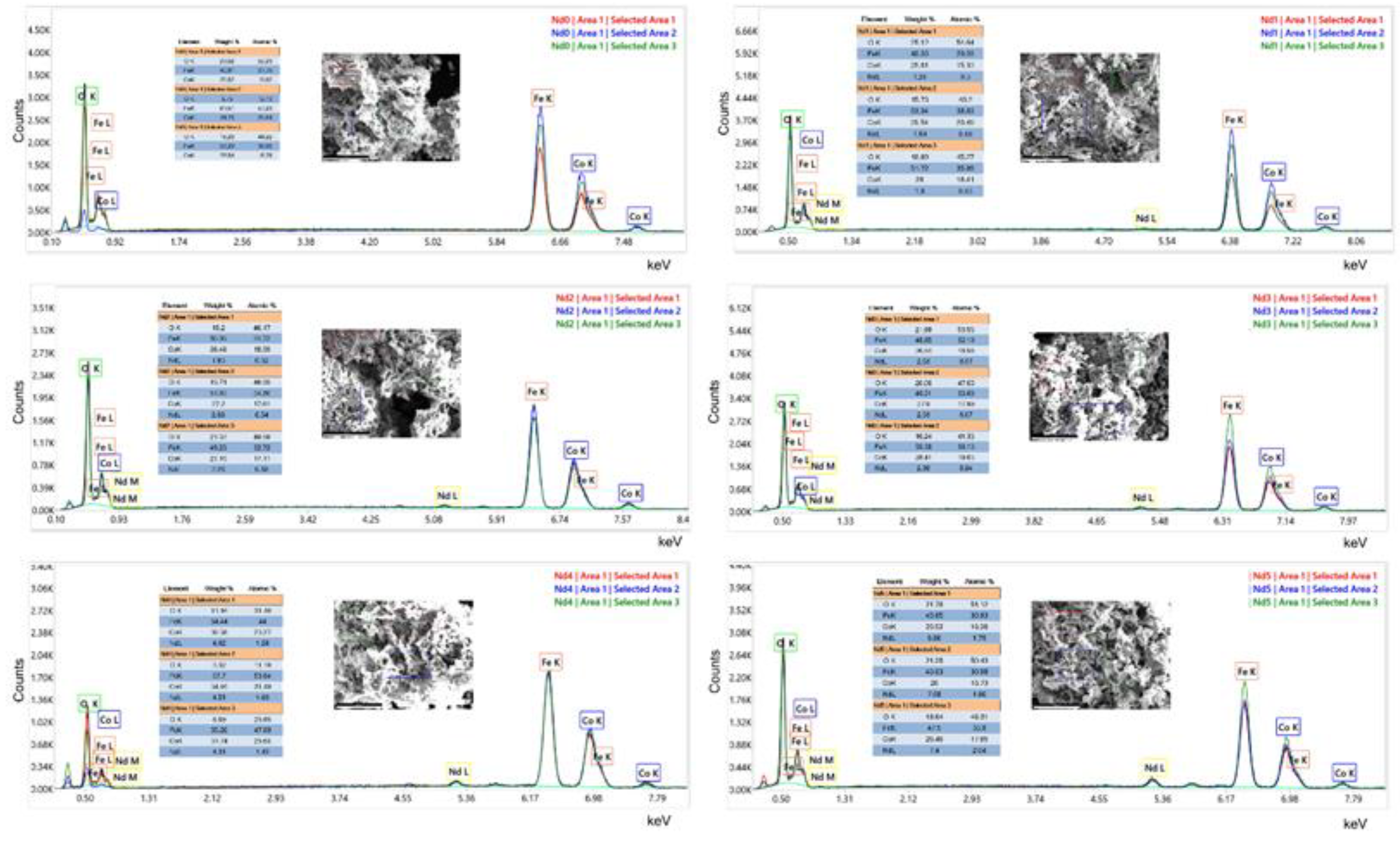

In all samples, the lattice parameter a from the cubic spinel network increases with the increase of the Nd content as revealed by the Rietveld refinement thus suggesting that a higher amount of Nd successfully enters the cubic lattice. Consequently, the presence of Nd with a higher atomic radius caused the expansion of the unit cell, and simultaneously of the lattice parameter. The EDAX analysis showed that the characteristic band for Nd in present in samples Nd1 – Nd5 which, combined with the increase in lattice parameter, can be interpreted as proof for the successful inclusion of Nd into the spinel lattice.

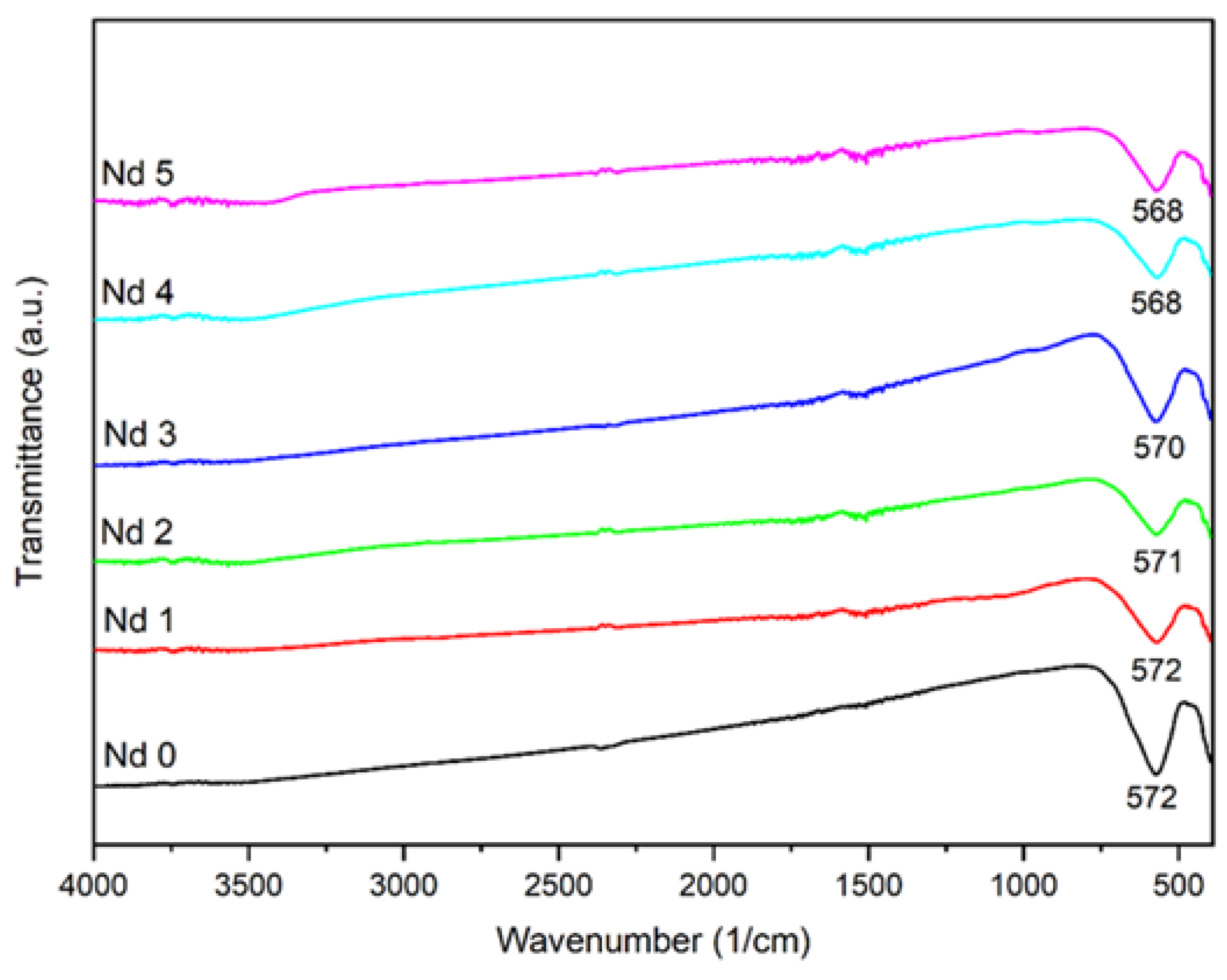

The FTIR spectra of the undoped and doped samples show similar absorption bands, characteristic for cobalt ferrite. The intense band located at approximatively 570 cm

-1 could be attributed to the metal-oxygen stretching vibration of the tetrahedral sites while the partially visible one around 400 cm

-1 can be allocated to the metal-oxygen stretching vibration from the octahedral sites. In addition, a small shift of the absorption band occurred, from 572 cm

-1 in Nd0 to 568 cm

-1 in Nd5 which contains the highest dopant quantity; this small shift can be attributed to the presence of Nd whose amount triggers the band movement towards lower wavenumbers due to alterations in cation distribution as well as lattice distortion. Furthermore, the band is attributed to the metal-oxygen stretching vibration from tetrahedral sites, so the shift could also indicate a tampering in the metal-oxygen bond [

20]. Moreover, Iram et al. [

21] studied lanthanum- and Nd-doped cobalt-strontium ferrite and underlined the build-up tension in the spinel structure caused by the presence of higher ionic radius rare earth elements. Additionally, they mentioned that during cation redistribution at the octahedral site the ions of the doping elements could overlap the iron ions leading to distortions at the interstitial positions.

Wu et al. [

22] synthetized CoFe

1.9RE

0.1O

4 (RE = Ho

3+, Sm

3+, Tb

3+, Pr

3+) nanoparticles by means of the hydrothermal method and similarly reported the two bands characteristic for cobalt ferrite as well as a slight shift in the absorption maximum for the doped samples. Moreover, due to the affinity of rare earth elements for octahedral sites, as well the formation of vacancies, cation redistribution and a potential migration of iron from octahedral to tetrahedral sites, the metal-oxygen vibration will be altered, indicating changes in the Fe-O bond length and strength [

18,

23].

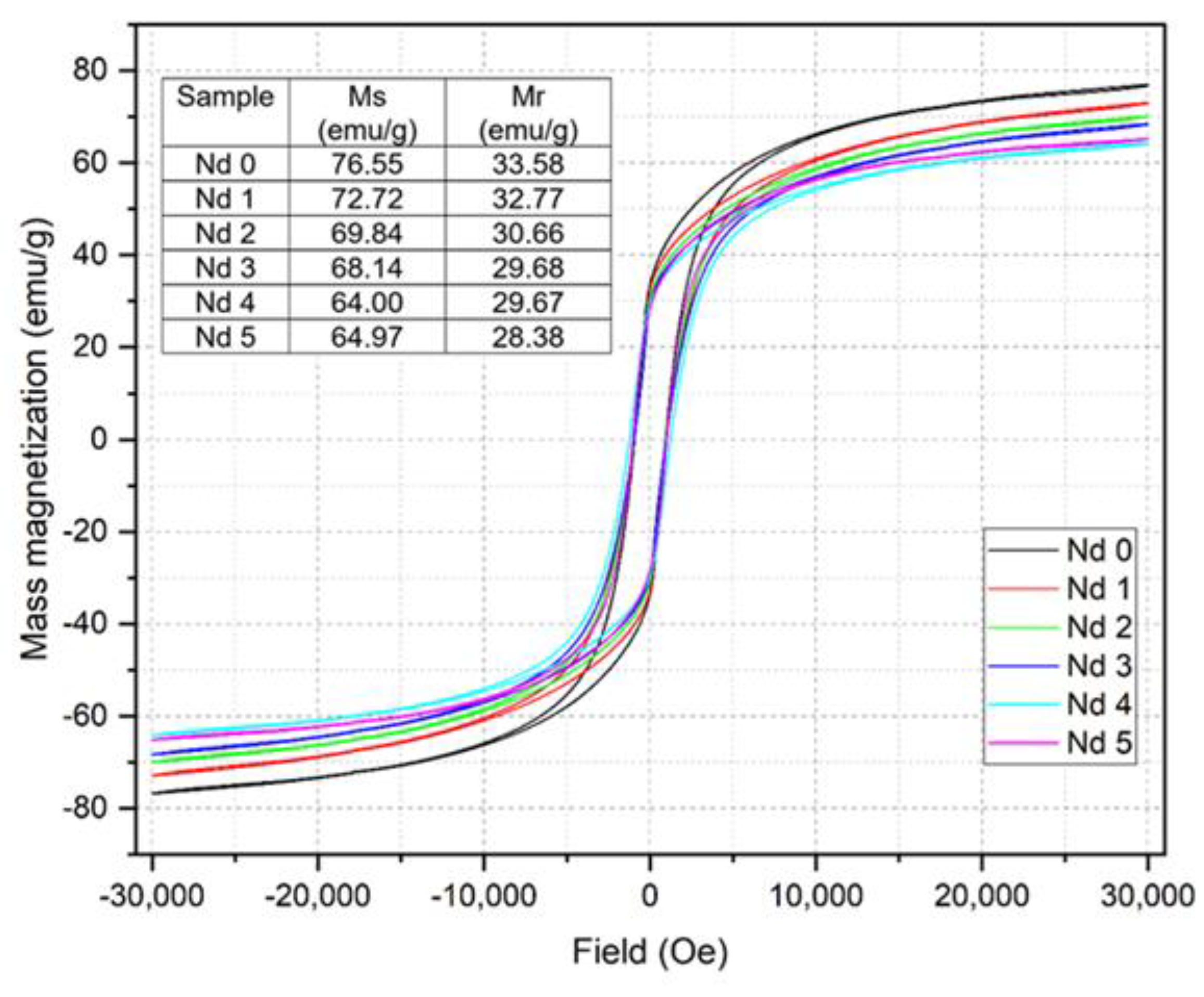

The magnetic measurements revealed a linear decrease in both mass magnetization Ms and remnant magnetization Mr with the increase of the Nd content. While for the undoped sample Nd0 the values of Ms and Mr are 76.55 emu/g and 33.58 emu/g, respectively, in sample Nd5 the values decrease to 64.97 emu/g and 28.38 emu/g, respectively. The reduced magnetization was also reported in another CoFe

2-xNd

xO

4 study [

19] where the Ms starting value of 54.61 emu/g for the undoped sample dropped to 34.53 emu/g for x=0.06. Furthermore, Wang et. al. [

18] noted a similar impact exerted by Nd on the magnetic properties of the resulting nanoparticles, stating that the phenomenon could be considered an indirect proof that Nd has successfully entered the ferrite lattice.

The magnetization reduction can be explained by the substitution of the smaller ionic radius Fe

3+ with the larger ionic radius Nd

3+. As previously mentioned, this notable difference in ionic radius disrupts the crystal structure leading to lattice distortion, cation redistribution between sites, and the occurrence defects. Moreover, the replacement of Fe

3+ with Nd

3+ in the B site will impair the super exchange interaction between A (tetrahedral) and B (octahedral) sites; according to Wang et al. [

18], the super exchange interaction between A and B sites (Fe

3+A—O

2—Fe

3+B or Fe

3+A—O

2—Co

2+B) are weakened, while the interactions from B and B sites (Fe

3+B—O

2—Co

2+B or Fe

3+B—O

2—Fe

3+B) will exhibit an increase in the negative exchange, showing stronger antiferromagnetic behavior.

In addition, a contribution to the decline of the magnetic properties can also be attributed to the presence of the NdFeO

3 secondary phase that could disrupt the interaction within the crystal lattice [

24].

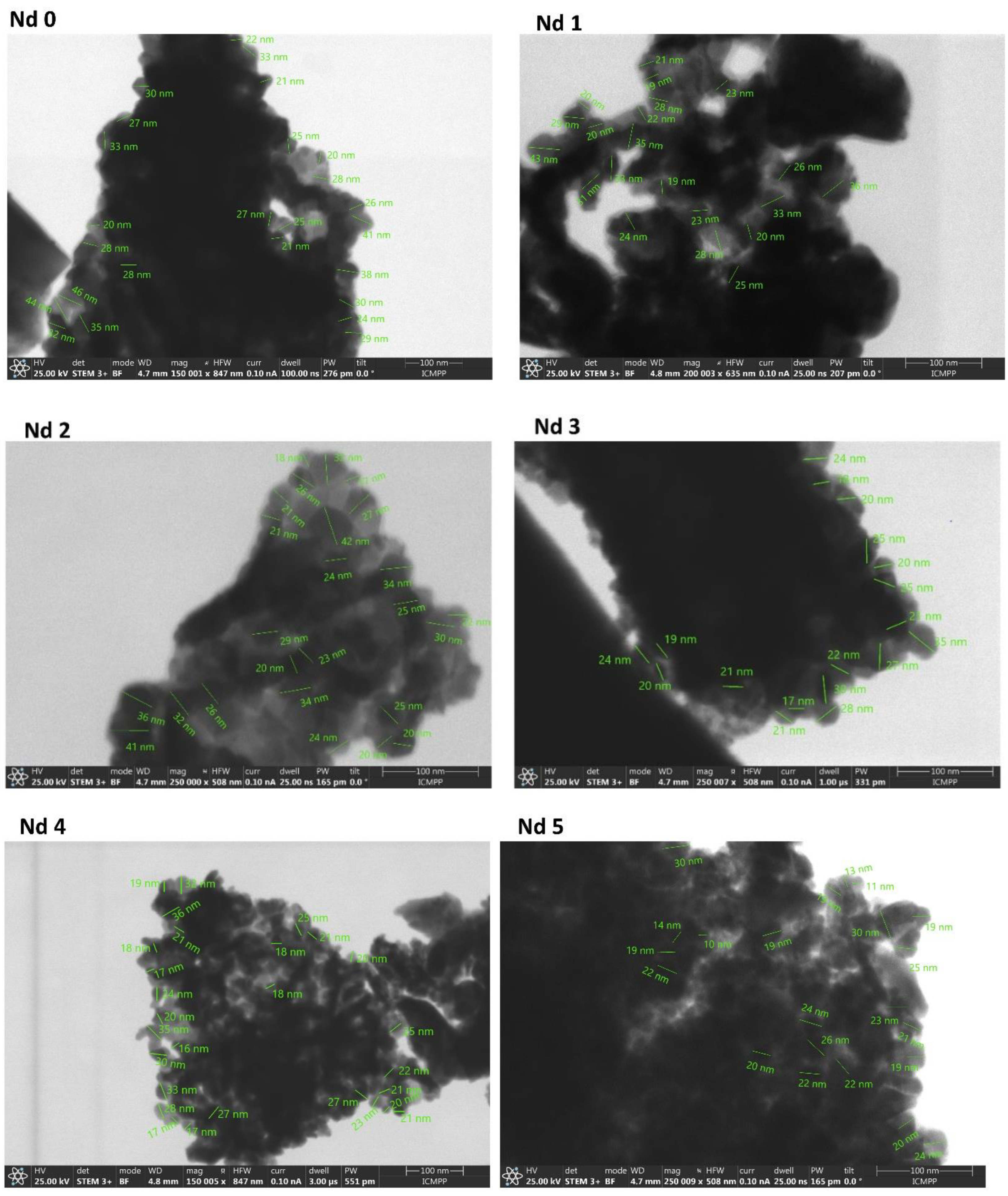

The STEM analysis revealed that the reaction yielded particles with dimension between 10 and 46 nm. The insertion of Nd into the ferrite lattice caused a decrease in particle size depending on the Nd content; thus, the smallest nanoparticles (10-30 nm) were identified in sample Nd5 which contained the highest amount of the doping element. In our previous study [

25] we focused on dysprosium-doped cobalt ferrite CoFe

2-xDy

xO

4 (x=0; 0.1; 0.2; 0.4) and achieved comparable results, with increasingly reduced nanoparticle as the dysprosium content increased. Similar results were reported by Yusafi et al. [

23] who synthesized CoNd

xFe

2-xO

4 for x=0.0-0.5 and recorded a particle decrease with the increase of the Nd content. They also noted an intense particle agglomeration as well as a tendency towards irregular nanoparticle shape following Nd insertion into the ferrite lattice. As previously explained, this phenomenon is caused by the difference in ionic radius between iron and Nd which induces alterations in the spinel lattice. Furthermore, Wang [

18] noted that, in addition to the Nd insertion in the crystal lattice, the occurrence of the secondary phase can also alter the normal formation of the ferrite grains. As an example, in gadolinium doped nickel ferrites [

26] the particle size decrease was justified by the pressure created by Gd

3+ ions at the grain boundaries, leading to growth restriction. Moreover, in the case of praseodymium-, holmium-, terbium- and samarium-doped cobalt ferrite, Wu et al. [

22] observed that all rare earths induced a particle size reduction, attributed to the localization of the dopants at the boundaries of the grain, thereby exerting pressure and inhibiting their growth.

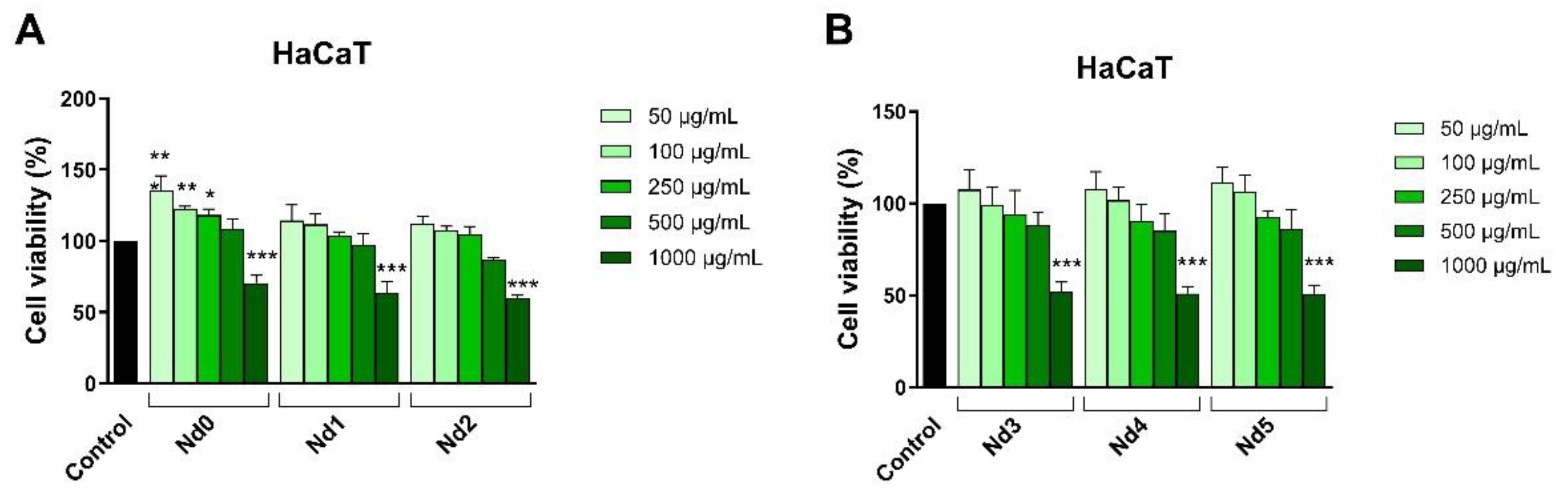

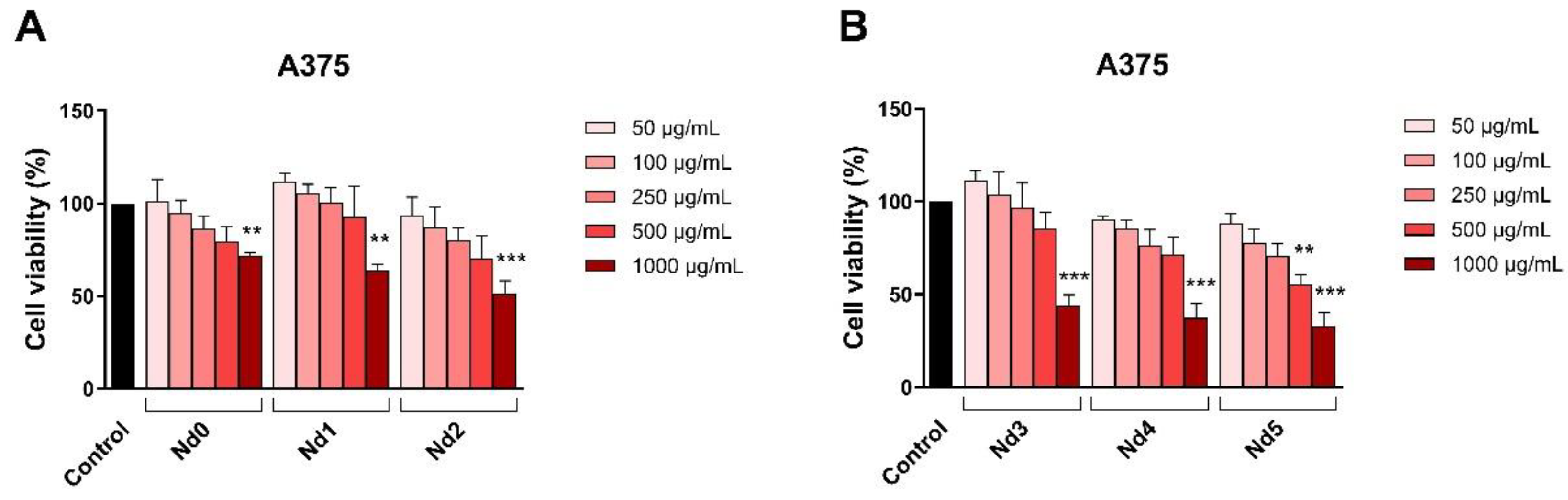

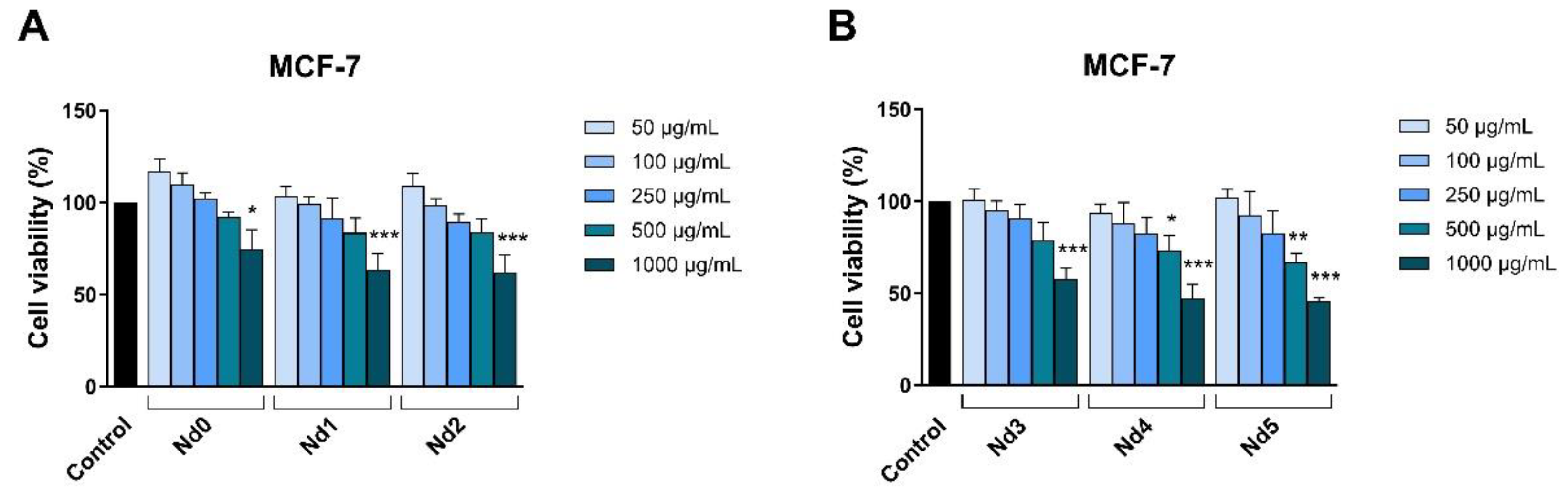

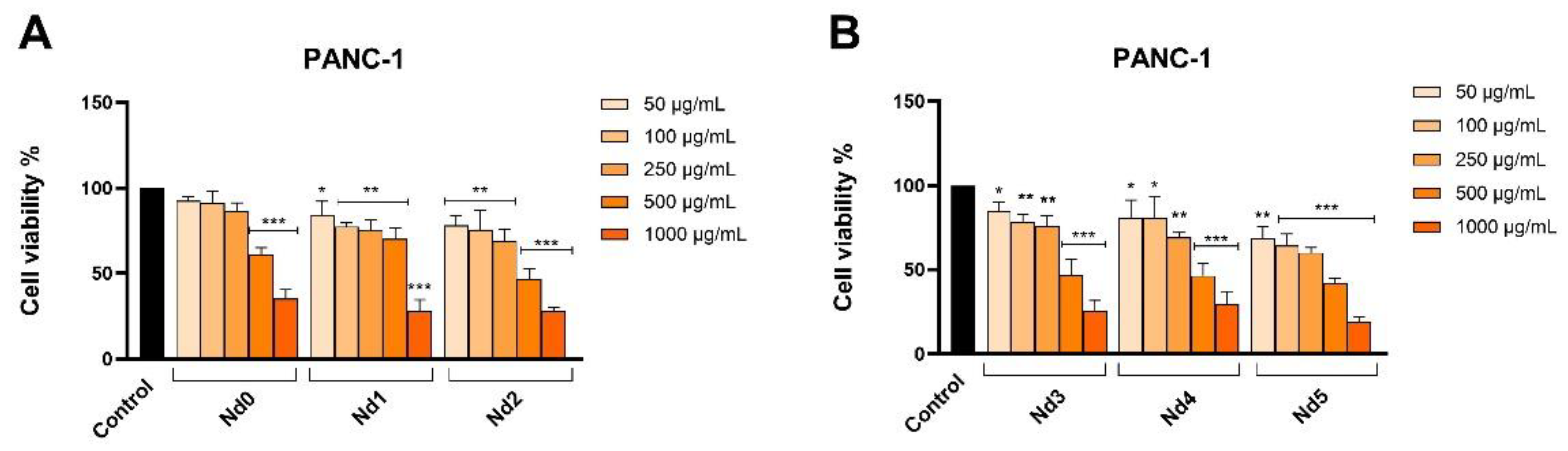

The newly synthesized nanoparticles were tested in terms of antiproliferative activity against three cancer cell lines aiming to identify a potential correlation between the Nd content and the respective biological effect. The antiproliferative activity was assessed by means of Alamar Blue assay. The antiproliferative effect manifested in a dose-dependent manner with the lowest cell viability reported for the highest applied concentrations of the tested samples. Remarkably, the Nd content significantly influenced the cell viability-decreasing action of the respective compound, its increase being directly proportional to the potency of the antiproliferative action. As clearly shown by previous studies, cobalt ferrites induce anticancer effects in a variety of cancer cells, fact validated in our study by the behavior of the Nd0 sample; however, the insertion of Nd into the cobalt ferrite crystal lattice increased the sample’s antiproliferative effects in all three cancer cell lines. The cytotoxic effect exerted by Nd in MCF-7 cancer cells was revealed by several studies that investigated Nd complexes [

27], Nd

2O

3 nanoparticles [

28], Nd-doped carbon dots [

29] and Nd

3+-doped GdPO

4 core nanoparticles [

30]; in all studies, the cytotoxic activity was accompanied by reduced toxicity. The gradual increase in Nd content from sample Nd1 to Nd5 is accompanied by a proportional decrease in the nanoparticle’s size which could explain the increased antiproliferative activity by the increased surface-to-volume ratio that ensures a better contact between the nanoparticle and the biological environment. Most importantly, the presence of Nd is essential for the antiproliferative activity; in the form of oxide, Nd

2O

3, it triggers the production of reactive oxygen species able to alter in a dose-dependent manner the function of cellular components such as DNA, protein and lipids and induce cell death [

31]. Such effects add to the anticancer properties of the cobalt ferrite itself which significantly decreased MCF-7 cell viability following uptake or adsorption by means of apoptosis induction [

32]. When screening for anticancer therapeutic options one must investigate the selectivity of newly developed agents in order to avoid systemic toxicity; one suitable test is in vitro cell viability in normal cells. We used HaCaT cells (immortalized human keratinocytes) that are widely used as research material due to their facile culture while maintain a relatively stable phenotype [

33]. It is of note that in low concentrations all samples lacked antiproliferative effects in HaCaT cells; moreover, some samples (e.g., Nd1, Nd2) even increased cell viability when applied in concentrations up to 500 μg/ml. Only when sample concentration increased to 1000 μg/ml HaCaT cell viability decreased; overall, such behavior characterized a highly selective anticancer activity [

34] which might hold promise for future therapeutic opportunities.

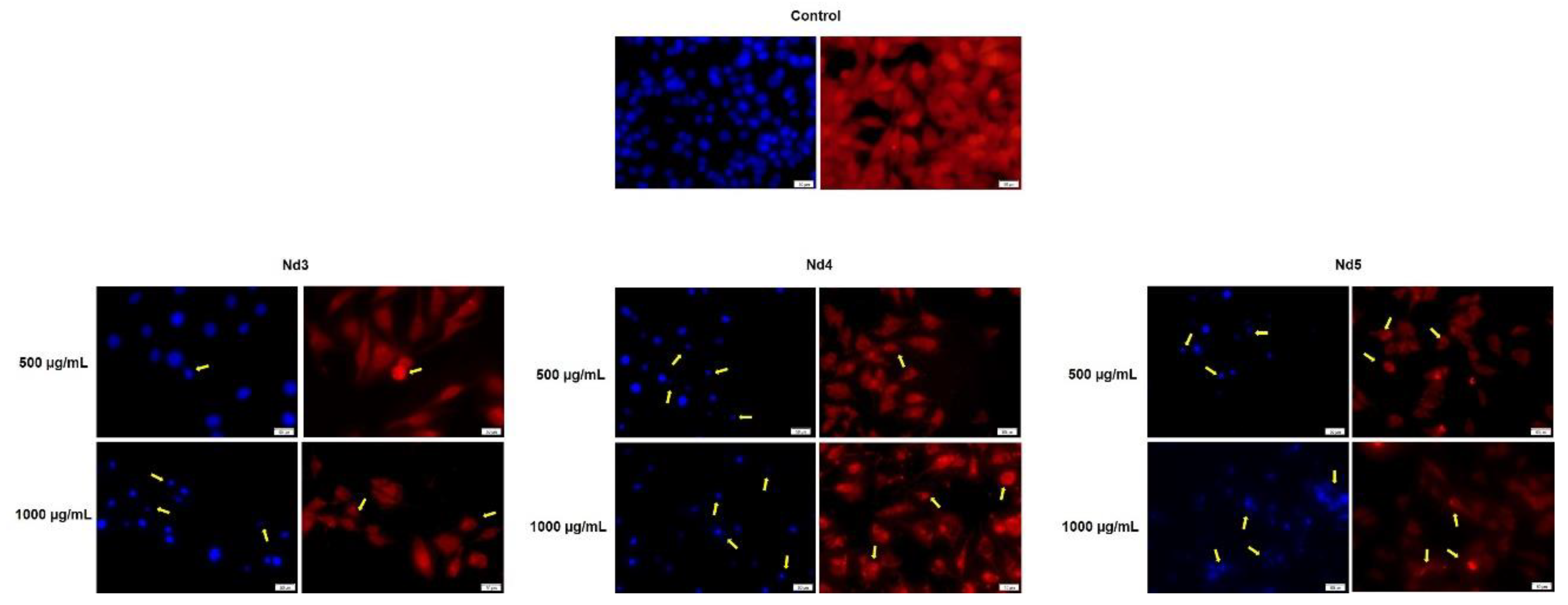

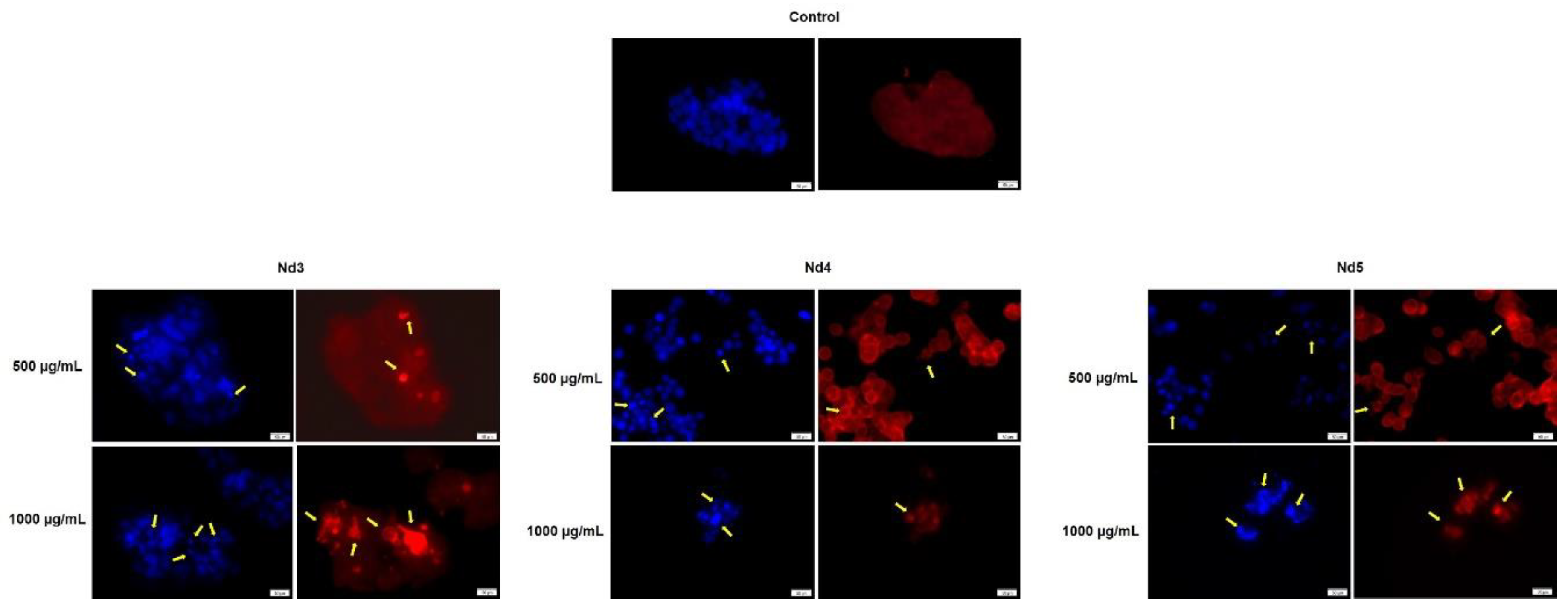

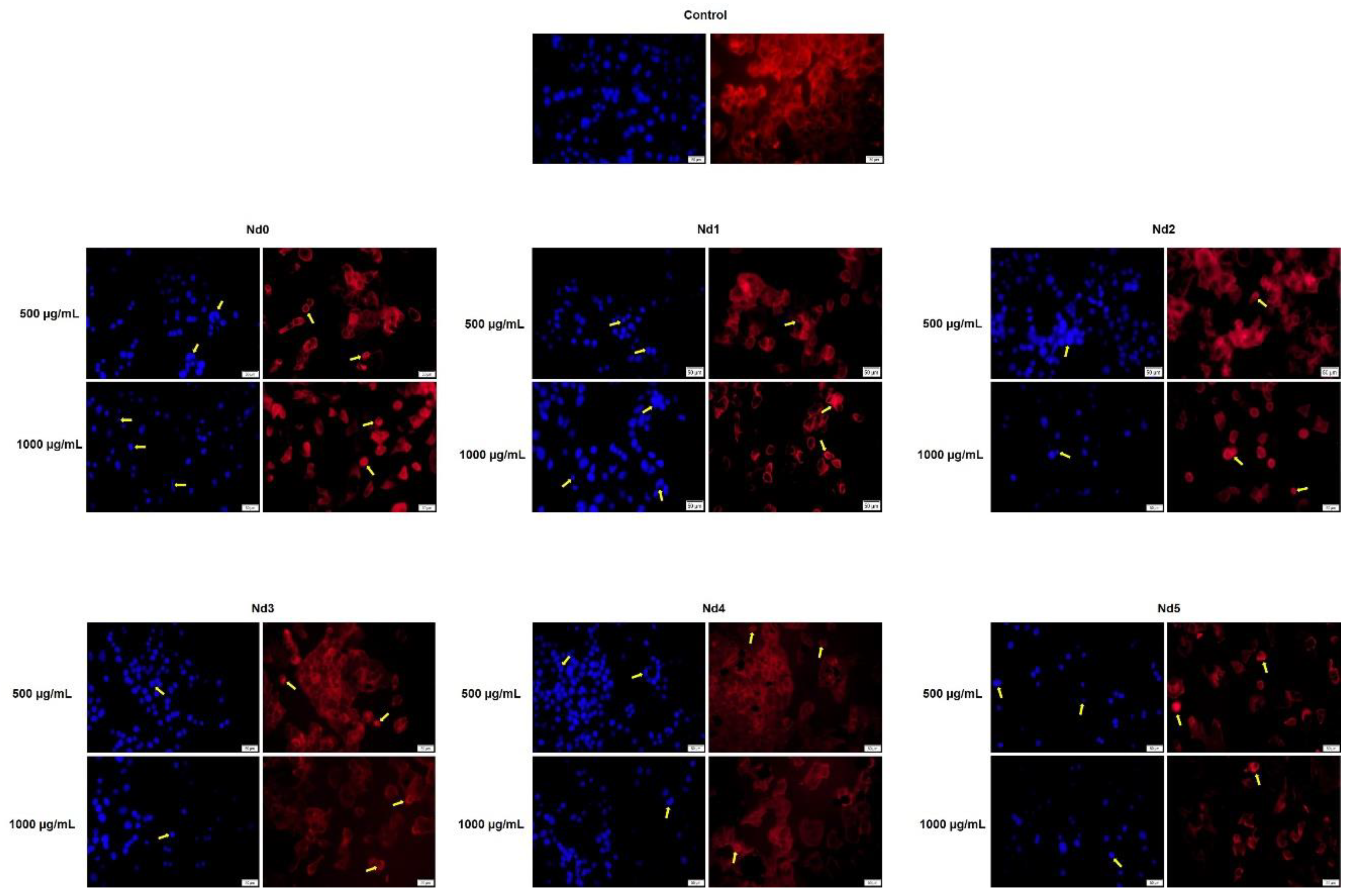

In agreement with cell viability tests, the morphological assessment using a immunofluorescence assay revealed spherical nuclei with evenly distributed chromatin in control cells accompanied by well-organized actin fibers within the cytoplasm. Treatment with metallic nanoparticles induced an altered morphology in all cancer cell types with nuclear condensation and fragmentation and the constriction of the actin fibers; cell shrinkage was also noticed thus indicating apoptotic effects [

35] whose intensity increased with the Nd content. Indeed, Nd was previously reported as an apoptosis inducer in mouse liver cells but in its most water-soluble form as Nd nitrate which was studied as an environmental pollutant [

36]. When tested as Nd

2O

3 nanoparticles in non-small lung cancer cells, Nd exerted cytotoxic effects mainly through autophagy instead of apoptosis [

37]. However, the apoptotic mechanism of cell death was previously reported for undoped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles in liver and colon cancer cells in a concentration-dependent manner [

38]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on the cytotoxic effects of Nd-doped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles that occur through apoptotic mechanisms.

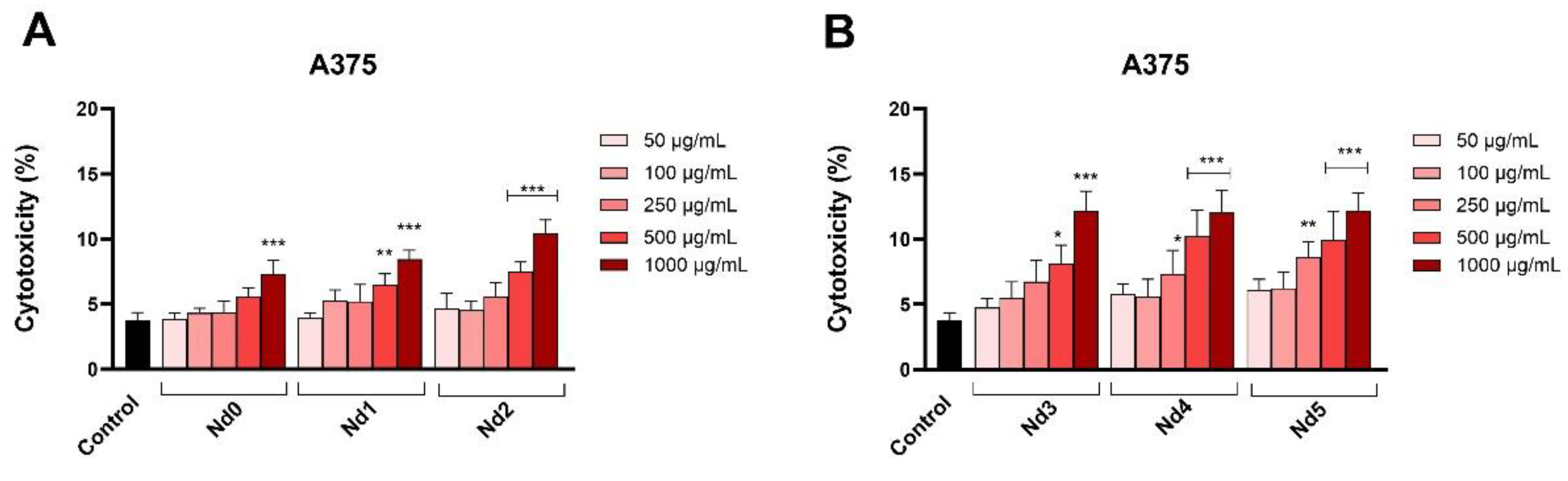

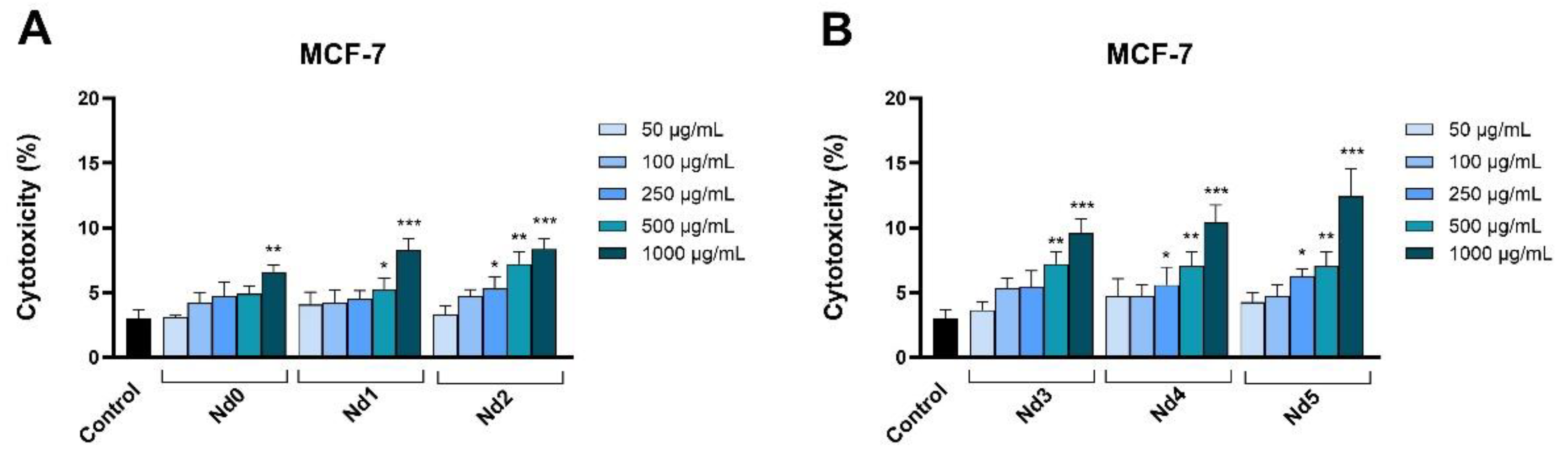

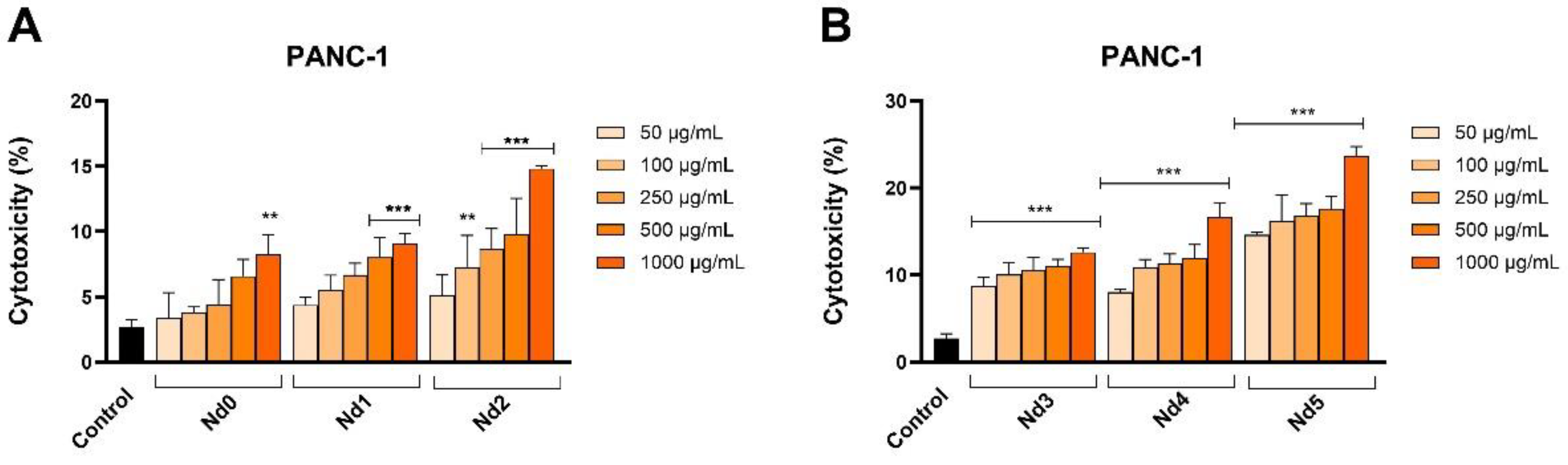

In order to confirm their cytotoxic activity, we also assessed the release of lactate dehydrogenase in tested cancer cells following cell membrane alterations at 48h post-treatment. In all three cancer cells, the Nd-free sample Nd0 exhibited cytotoxic effects only when applied in high concentrations while the Nd-doped samples significantly increased the LDH release. LDH is an enzyme that catalyzes the metabolic conversion of pyruvate to lactate in the cytosol whose release in the extracellular space occurs following cell membrane damage or cell death thus making LDH release a reliable marker of cytotoxic effects [

39]. Cobalt ferrite nanoparticles were already reported to induce increased LDH release in A549 lung cancer cells [

40]; our results confirm such results that also validate cell viability tests.

Figure 1.

XRD spectra of the samples.

Figure 1.

XRD spectra of the samples.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the samples.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the samples.

Figure 3.

Magnetic hysteresis of samples.

Figure 3.

Magnetic hysteresis of samples.

Figure 4.

STEM images for samples Nd0 – Nd5.

Figure 4.

STEM images for samples Nd0 – Nd5.

Figure 6.

The viability of HaCaT cells treated for 48h with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as cell viability % normalized to control (100%, cells without treatment) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

The viability of HaCaT cells treated for 48h with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as cell viability % normalized to control (100%, cells without treatment) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

The viability of A375 cancer cells treated for 48h with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as cell viability % normalized to control (100%, cells without treatment) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

The viability of A375 cancer cells treated for 48h with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as cell viability % normalized to control (100%, cells without treatment) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 8.

The viability of MCF-7 cancer cells treated for 48h with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as cell viability % normalized to control (100%, cells without treatment) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 8.

The viability of MCF-7 cancer cells treated for 48h with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as cell viability % normalized to control (100%, cells without treatment) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 9.

The viability of PANC-1 cancer cells treated for 48h with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as cell viability % normalized to control (100%, cells without treatment) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 9.

The viability of PANC-1 cancer cells treated for 48h with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as cell viability % normalized to control (100%, cells without treatment) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 10.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release percentages in A375 cancer cells after 48h treatment with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and after treatment with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as LDH Release (%) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 10.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release percentages in A375 cancer cells after 48h treatment with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and after treatment with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as LDH Release (%) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 11.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release percentages in MCF-7 cancer cells after 48h treatment with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and after treatment with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as LDH Release (%) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 11.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release percentages in MCF-7 cancer cells after 48h treatment with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and after treatment with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as LDH Release (%) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 12.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release percentages in PANC-1 cancer cells after 48h treatment with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and after treatment with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as LDH Release (%) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 12.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release percentages in PANC-1 cancer cells after 48h treatment with Nd0, Nd1 and Nd2 (A) and after treatment with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 (B) at five concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL). These results are presented as LDH Release (%) and represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 and *** p < 0.001).

Figure 13.

Aspect of the nuclei and F-actin fibers in A375 cells treated for 48 h with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 at two representative concentrations (500 and 1000 μg/mL). The scale bars indicate 50 µm.

Figure 13.

Aspect of the nuclei and F-actin fibers in A375 cells treated for 48 h with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 at two representative concentrations (500 and 1000 μg/mL). The scale bars indicate 50 µm.

Figure 14.

Aspect of the nuclei and F-actin fibers in MCF-7 cells treated for 48 h with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 at two representative concentrations (500 and 1000 μg/mL). The scale bars indicate 50 µm.

Figure 14.

Aspect of the nuclei and F-actin fibers in MCF-7 cells treated for 48 h with Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 at two representative concentrations (500 and 1000 μg/mL). The scale bars indicate 50 µm.

Figure 15.

Aspect of the nuclei and F-actin fibers in PANC-1 cells treated for 48 h with Nd0, Nd1, Nd2, Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 at two representative concentrations (500 and 1000 μg/mL). The scale bars indicate 50 µm.

Figure 15.

Aspect of the nuclei and F-actin fibers in PANC-1 cells treated for 48 h with Nd0, Nd1, Nd2, Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 at two representative concentrations (500 and 1000 μg/mL). The scale bars indicate 50 µm.

Table 1.

The sample composition.

Table 1.

The sample composition.

| Sample |

NdCl3·6H2O (moles) |

Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (moles) |

| Nd0 |

- |

0.0400 |

| Nd1 |

0.0002 |

0.0398 |

| Nd2 |

0.0004 |

0.0396 |

| Nd3 |

0.0006 |

0.0394 |

| Nd4 |

0.0010 |

0.0390 |

| Nd5 |

0.0020 |

0.0380 |

Table 2.

Calculated lattice parameter a.

Table 2.

Calculated lattice parameter a.

| Sample |

Lattice parameter a

(Å) |

| Nd0 |

8.3762 ± 0.0003 |

| Nd1 |

8.3781 ± 0.0004 |

| Nd2 |

8.3796 ± 0.0004 |

| Nd3 |

8.3799 ± 0.0004 |

| Nd4 |

8.3830 ± 0.0004 |

| Nd5 |

8.3873 ± 0.0002 |

Table 3.

The calculated IC50 values (µg/mL) of Nd0, Nd1, Nd2, Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 in HaCaT, A375, MCF-7 and PANC-1 cells after a 48h treatment.

Table 3.

The calculated IC50 values (µg/mL) of Nd0, Nd1, Nd2, Nd3, Nd4 and Nd5 in HaCaT, A375, MCF-7 and PANC-1 cells after a 48h treatment.

| |

HaCaT |

A375 |

MCF-7 |

PANC-1 |

| Nd0 |

>1000 |

>1000 |

>1000 |

748.7 |

| Nd1 |

>1000 |

>1000 |

>1000 |

687.9 |

| Nd2 |

>1000 |

>1000 |

>1000 |

593.5 |

| Nd3 |

>1000 |

943.5 |

>1000 |

581.8 |

| Nd4 |

>1000 |

798.8 |

956.3 |

572.3 |

| Nd5 |

>1000 |

650.7 |

877.2 |

397.7 |