2.3.1. Composition and Floristic Richness of Rubber Plantations

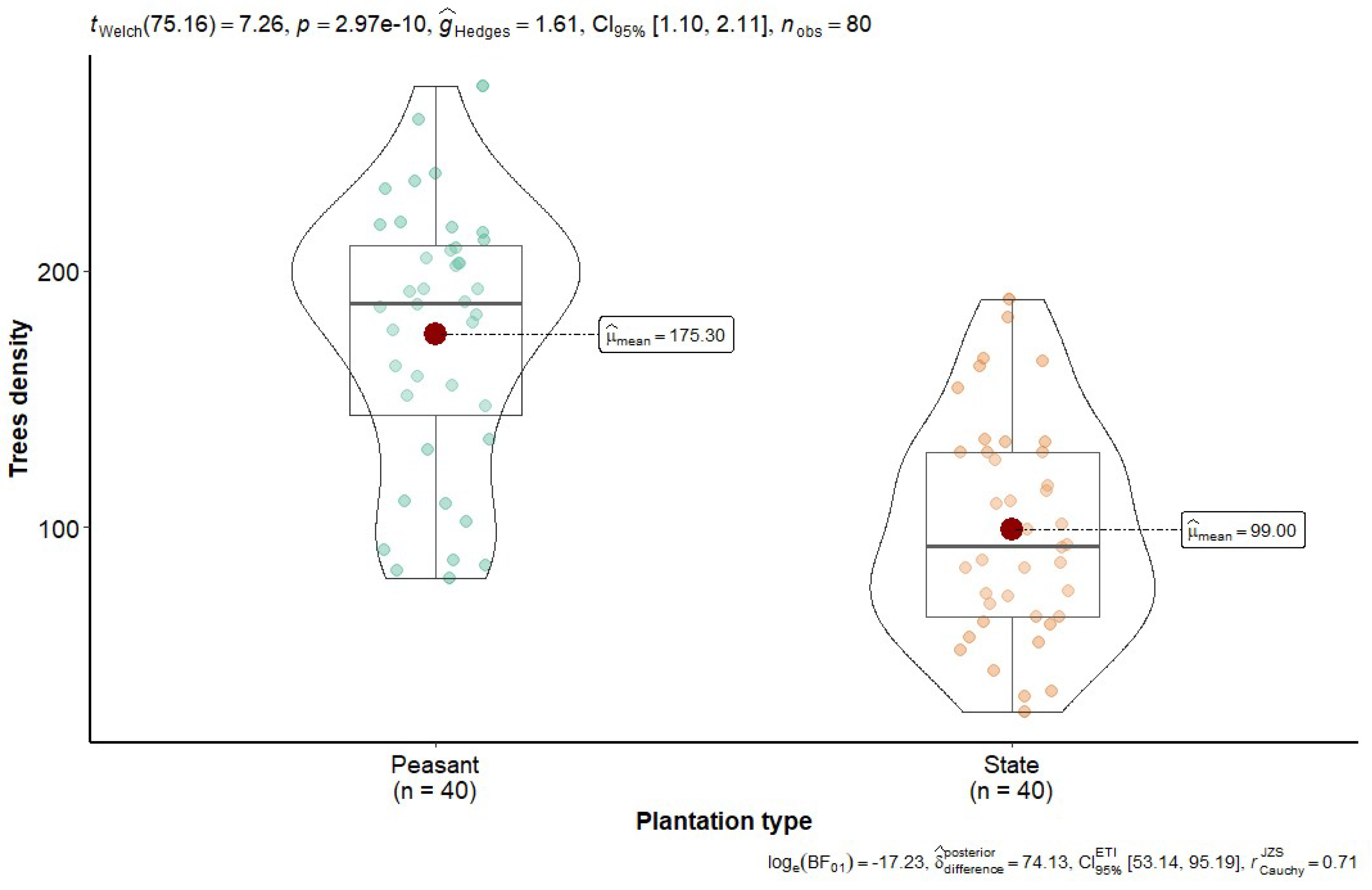

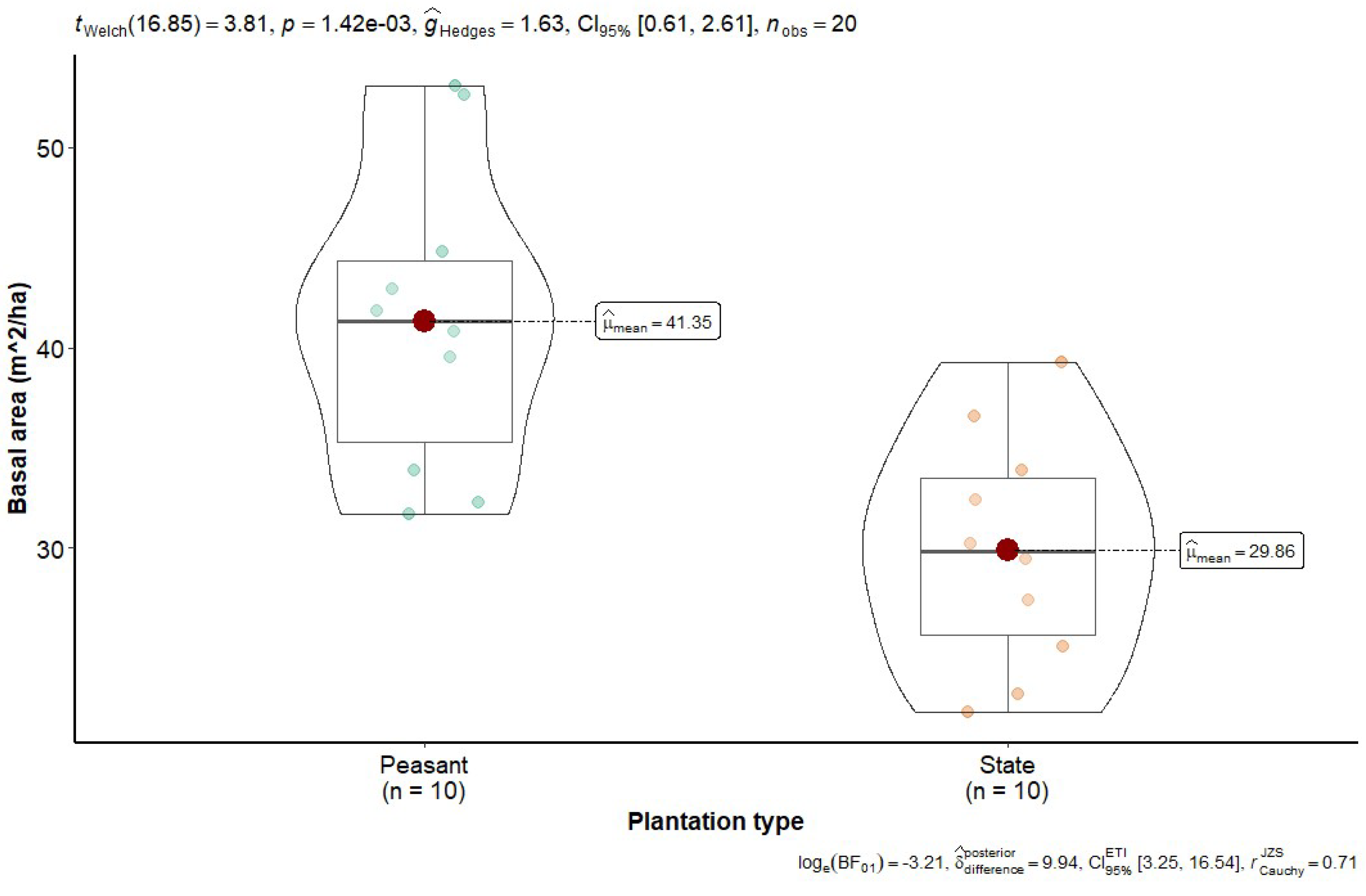

The floristic composition and richness of each rubber plantation type were assessed by analysing various floristic indicators, including the number of individuals, species, genera, and families, and basal area per sample plot (or per hectare). Relative abundance and dominance were calculated for each species and family, along with an importance value index, to classify species and families according to their level of importance in rubber plantations. The values of these indicators were calculated using Microsoft Excel 2021. The Student's t-test was implemented through the R Commander interface integrated into R [

19,

29,

30] to assess the equality of mean densities (individuals, species, and families) and mean basal area of the two plantation types. The rationale behind employing this parametric test stemmed from the findings of the Shapiro-Wilk normality test and the Fisher test, which attested to the normality and equality of variances across the diverse sets of data collected.

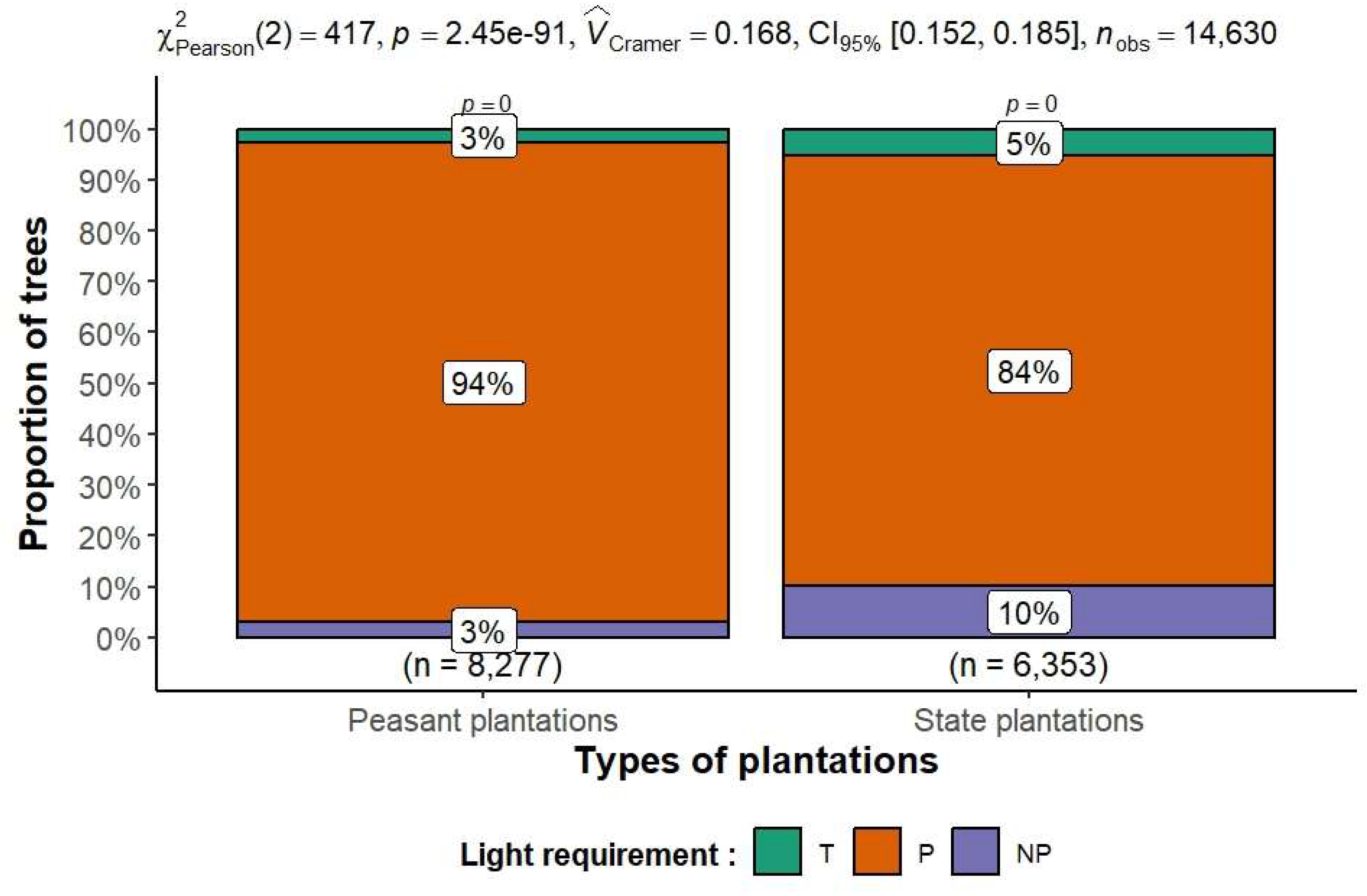

To assess the level of disturbance of rubber plantations in Sankuru, the degree of disturbance of each type of plantation was evaluated. This was achieved by determining the weight of pioneer species in relation to the total number of species inventoried. The " Pioneer " index [

30] was calculated for this purpose according to equation 1:

In this study, pi represents the number of individuals of pioneer species, np denotes the number of individuals of non-pioneer but heliophilous species, and N signifies the total number of individuals of all species inventoried. PI ranges from 0, indicating an absence of pioneer species and, consequently, an absence of disturbance, to 100, representing all species as pioneers, resulting in a complete disturbance or secondarization of the forest. This Pioneer Index is an effective metric for evaluating the extent of disturbance or degradation within a forest ecosystem. It can distinguish secondary and mature forests at the 50% threshold [

31]

.

The decision to calculate the pioneer species index as part of this study was based on the importance of understanding the ecological role of pioneer species in Sankuru's historic rubber plantations. The evaluation of this index facilitated a more profound comprehension of the dynamics of plant succession and the process of ecological regeneration in these plantations. Furthermore, it facilitated the identification of species that promote the evolution of plant communities over time. Moreover, the index has contributed to our understanding of the capacity of these plantations to restore themselves naturally, while assessing the impact of human management on biodiversity. This comprehensive approach offers a more nuanced perspective on the floristic structure of plantations, thereby facilitating biodiversity conservation and the sustainability of agricultural practices within these ecosystems.

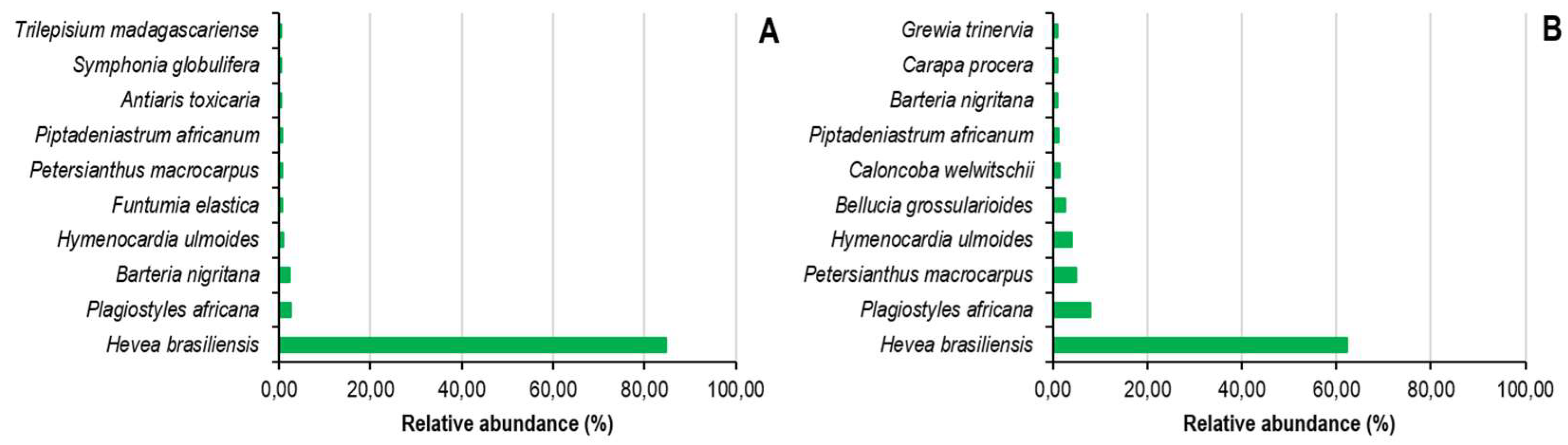

The abundance, or relative density, of a species or family is the ratio of the number of individuals of a species or family to the total number of individuals in the sample. The relative density (Dr) for each species and family was calculated using the following equation (2):

The decision to assess relative density is based on the importance of understanding species distribution within these two types of plantations. This methodological approach facilitates a more profound comprehension of floristic diversity and enables the monitoring of the evolution of historical rubber plantations. Consequently, it enhances sustainable management and conservation of local ecosystems in Sankuru.

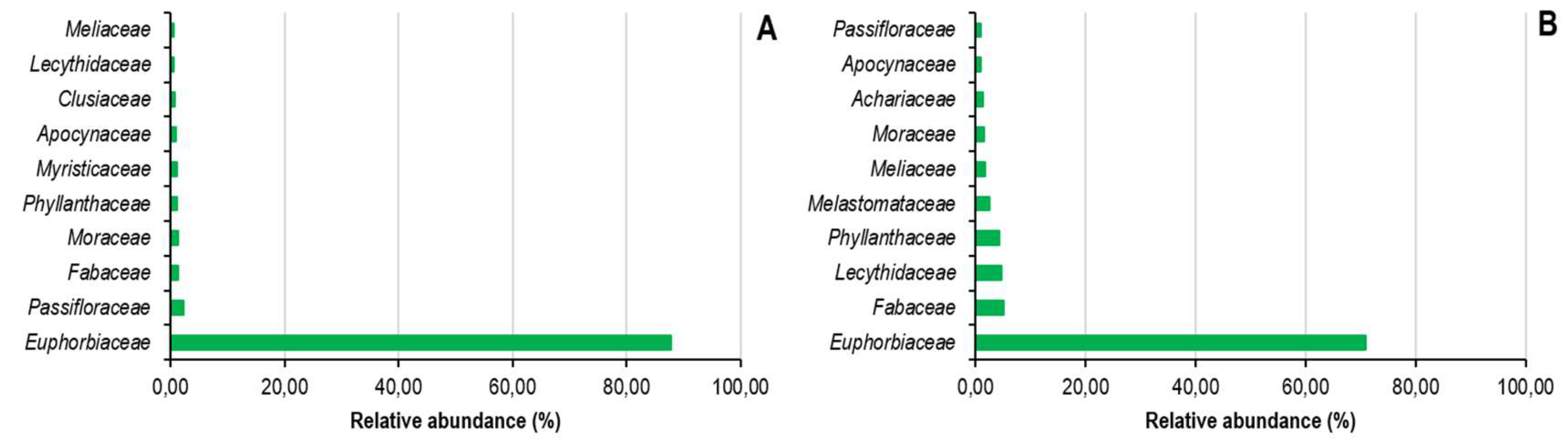

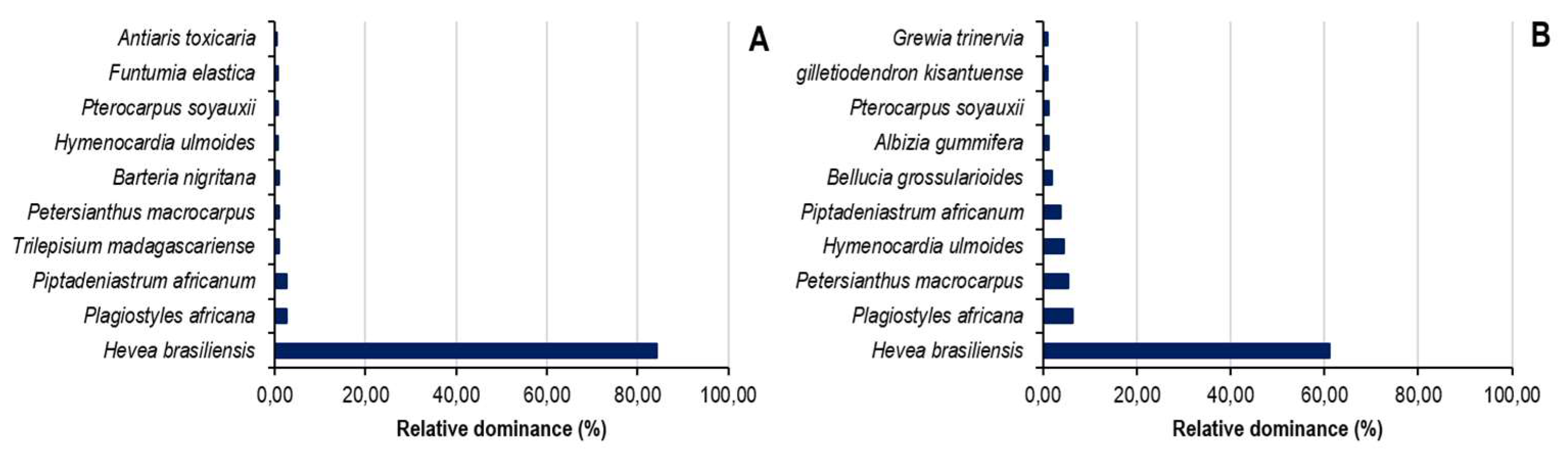

Relative dominance is defined as the ratio of the basal area of a given species or family to the total basal area. The relative dominance (Dor) for each species and family was calculated using the following equation (3):

The decision to assess relative dominance in this study was based on the need to understand the impact of the most abundant species (basal area) within the historical rubber plantations of Sankuru. This approach facilitated the identification of species that dominate the plant landscape, thereby influencing the structure and dynamics of local ecosystems. By assessing relative dominance, we could better understand the mechanisms of natural regeneration, the interactions between species, and their role in the ecological balance of plantations. This approach is instrumental in formulating sustainable management and conservation strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of Sankuru ecosystems.

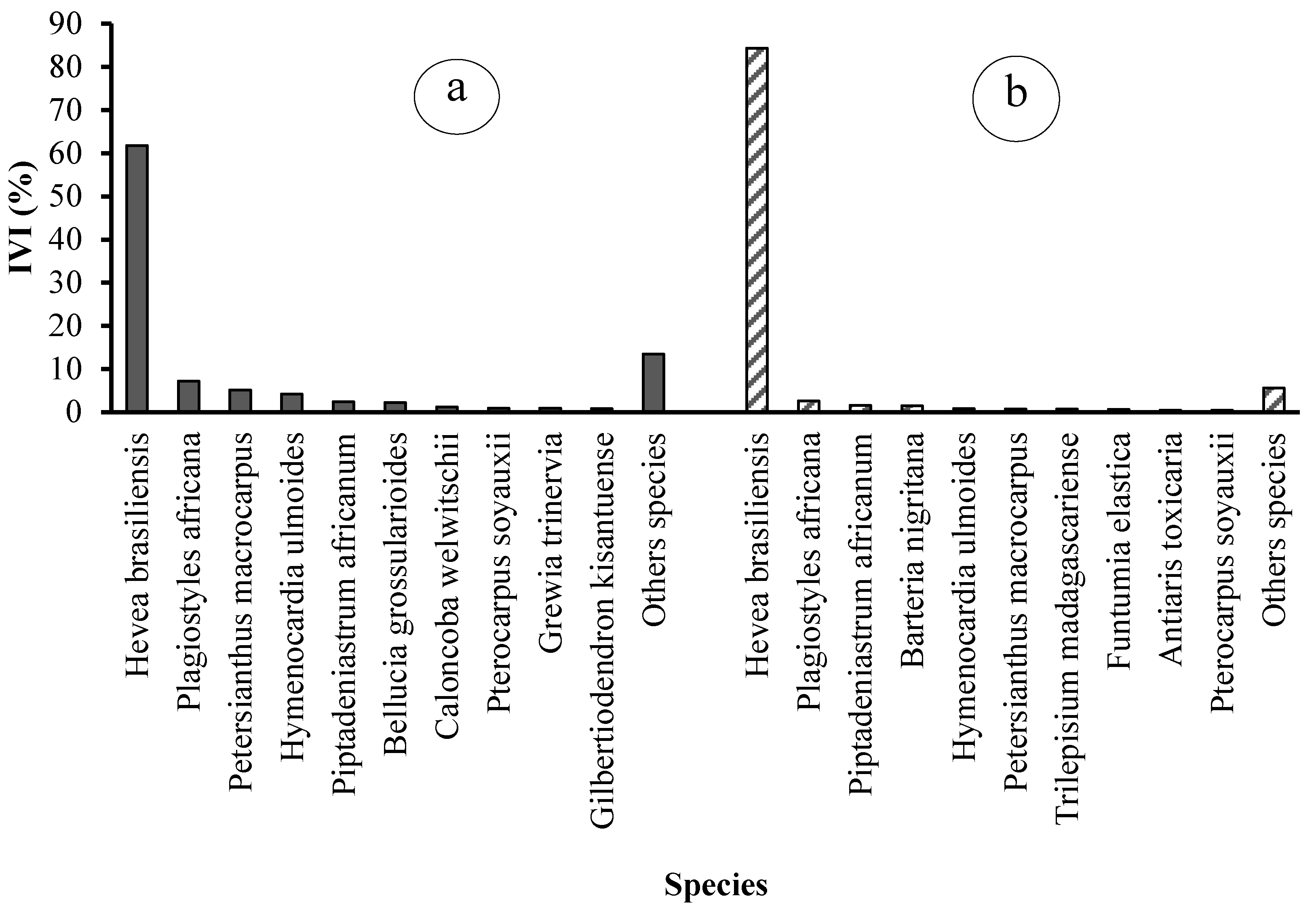

The importance value index is a metric that quantifies a species' dominance within a specific environment. It is calculated by the sum of relative abundance (Dr) and relative dominance (Dor), with a range of values from 0 to 100. The importance value index has been calculated for species and families in state and farmer plantations using formula (4) for species and formula (5) for families.

In this study, a family's relative diversity (Dr) is the ratio between the number of species in the family and the total number of species. The relative density (Dr) is expressed as the ratio between the number of species in the family and the total number of species. The relative dominance (Dor) is calculated as the ratio between the number of species in the family and the total number of species. The rationale for evaluating the species importance value index in this study is predicated on the necessity to obtain an integrated measure of the relative importance of each species within historical rubber plantations. The utilization of this index in the present study enables the identification of species that necessitate consideration for developing sustainable management strategies, thereby fostering biodiversity conservation in rubber plantations within the Sankuru region.

The area-species curve is a graphical representation of the increase in species found in a biotope as a function of the number of samples taken. The individuals-species curve, on the other hand, signifies the number of individuals per species surveyed. The area-species and individual-species curves were calculated using the specaccum function in the vegan package of R software [

19], using the random method. The red line in the centre represents the area-species curve, and the coloured area (green or pink) represents the confidence interval.

The choice to evaluate the area-species and individual-species curves in this study is based on the desire to analyse the dynamics of floristic diversity within the historical rubber plantations of Sankuru. The area-species curve is a quantitative metric that quantifies the relationship between the number of species present and the sample area. It provides information on species richness and distribution in different plantation areas. Conversely, the individual-species curve facilitates the visualisation of species distribution according to their abundance, thereby identifying the most abundant and the rarest species. This, in turn, contributes to a more profound comprehension of the plant community's structural dynamics. The integration of richness and abundance dimensions offered by these two curves provides fundamental insights into the ecological equilibrium and species diversity within these plantations. This, in turn, enables the adaptation of sustainable management strategies to ensure the preservation of local biodiversity and the regeneration of tropical ecosystems in the Sankuru region.

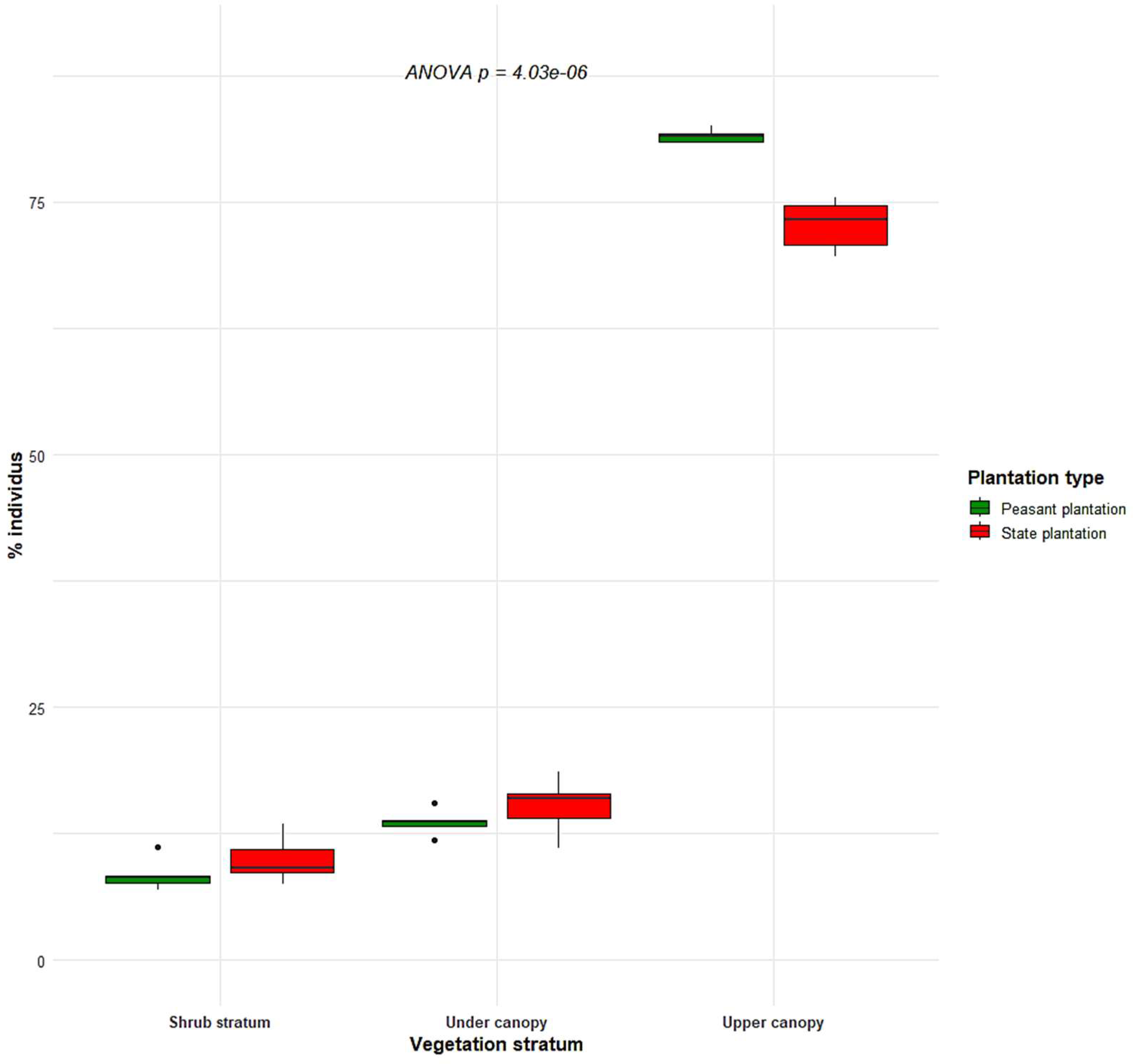

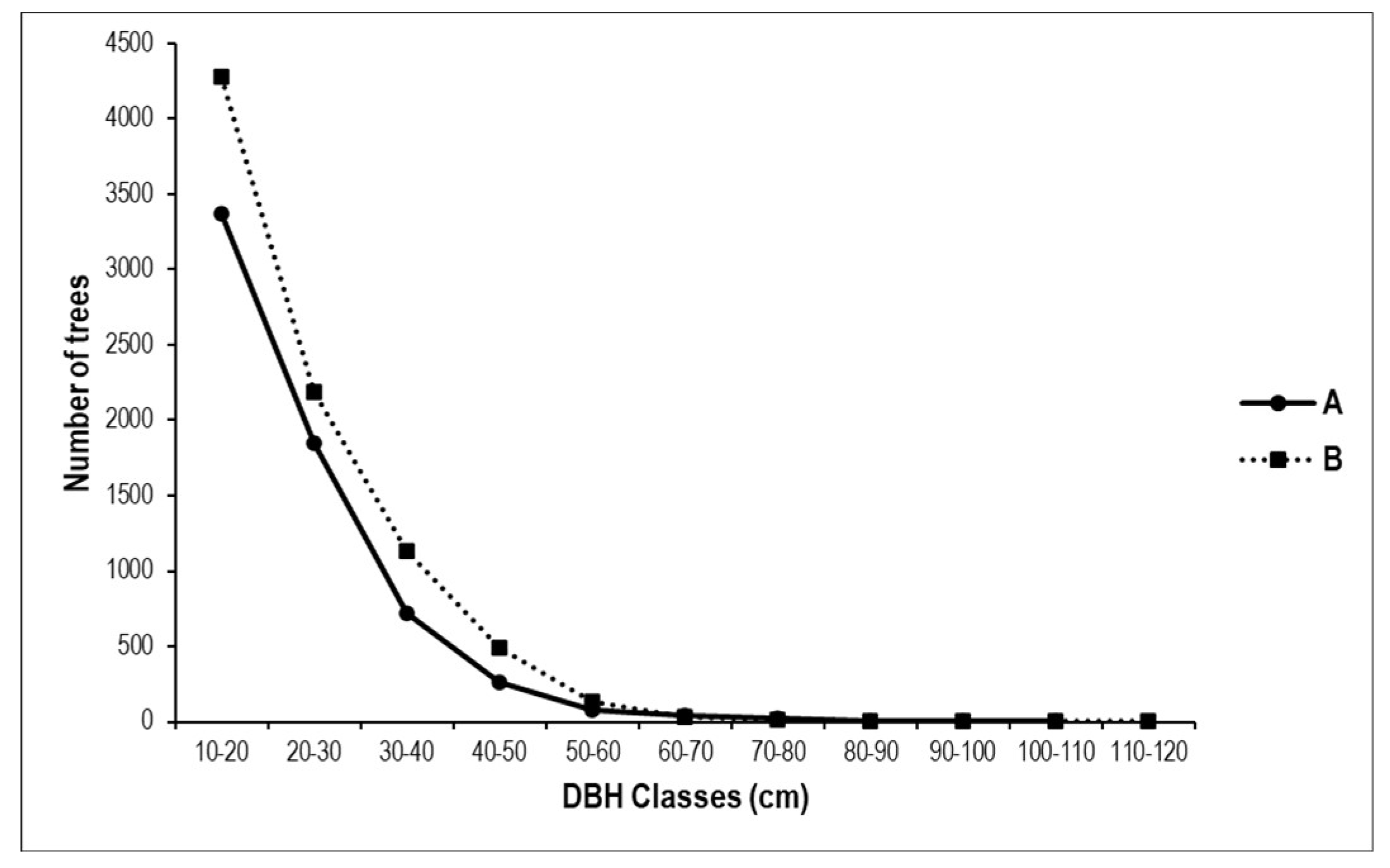

Tree populations were classified into 10 diameter classes to characterise the two plantation types and compare them in stand structure. The diameter classes were established using diameter at breast height (dbh) data as a reference. The horizontal and vertical structures of the former Lodja and Lomela plantations were then compared. To this end, an analysis of variance was performed to assess differences between plantations and standardised values of structural parameters. To examine variations in tree land area in former rubber plantations in the Lodja and Lomela territories, a one-factor analysis of variance was performed when all conditions were met. The Kruskal-Wallis test was employed when the conditions were not met.

The decision to evaluate the diametric structure of the study area is rooted in its significance in elucidating diametric class distribution and growth dynamics. This analysis provides insights into the age, regeneration, and overall health of the Sankuru's historic rubber plantations. We have discerned salient trends through meticulous analysis, including the prevalence of young, rapidly growing individuals, suggesting active regeneration. Conversely, the absence of young trees could indicate a paucity of natural renewal. This approach also provides essential information for plantation management by identifying potential imbalances in size distribution, which could impact long-term productivity and biodiversity. This assessment is a pivotal instrument for elucidating the dynamics of rubber stands and fostering a more profound comprehension of their evolution within the paradigm of sustainable management and conservation of local ecosystems in the Sankuru region.

2.3.2. Characterization of Floristic Diversity in Rubber Plantations

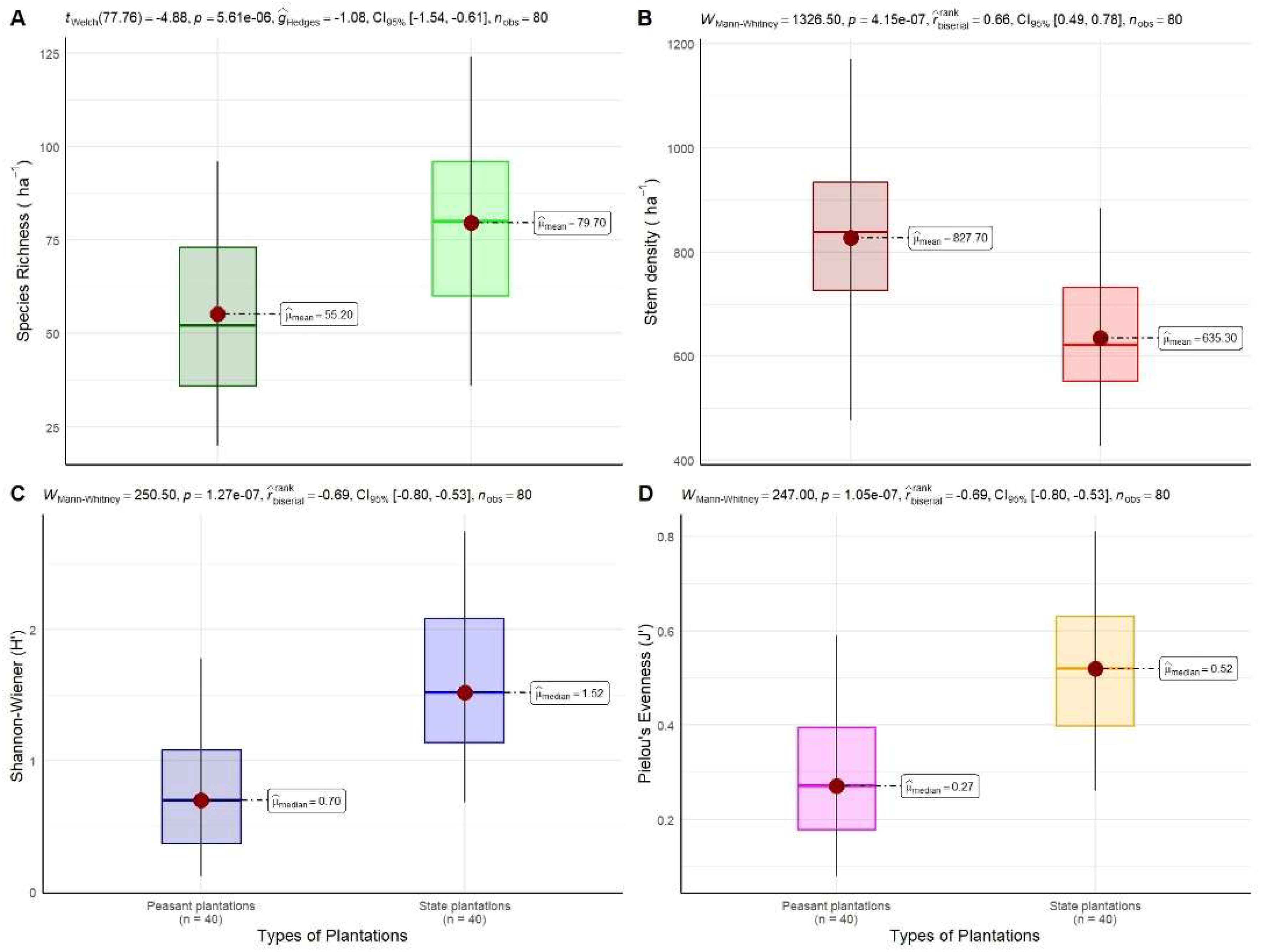

Quantitative diversity, which considers both species richness and the number of individuals within a species, was evaluated using the Shannon-Wiener [

32], Simpson [

33], and Piélou [

34] diversity and equitability indices. These indices were calculated using PAST 4.0.3 software [

34]. The Shannon-Wiener diversity index was calculated using the following formula [

35]:

In this study, H' is defined as the Shannon diversity index, m is the total number of species recorded in the ecosystem in question, and Pi is the individual proportion of species i. The Shannon index is a widely used metric for assessing species richness and evenness in an ecosystem [

36]. In the context of our study, this index is particularly relevant for quantifying the diversity of plant species present in historical rubber plantations. Higher values of the index indicate greater specific diversity. This index enabled a comparative analysis of plant diversity between state-owned and peasant plantations, providing crucial information for understanding the impact of plantation management and structure on local biodiversity. The index typically ranges from 1 to 5 [

36]. The index is classified as low when H' is less than 3 bits, medium when H' is between 3 bits and 4 bits, and high when H' is between 4 and 5 bits, with H' rarely exceeding 5 bits [

36].

Simpson's index, developed by Edward Simpson in 1949, is a metric for assessing biodiversity. It calculates the probability that two randomly selected individuals belong to the same species. The formula employed to calculate Simpson's index is as follows (7):

In this study, Simpson's index (1-D) was employed to measure diversity, with S representing the number of species, ni denoting the number of individuals of species i, and N signifying the total number of individuals. This index will have a value of 1 to determine maximum diversity, while minimum diversity (all individuals belonging to a single species) is indicated by a value of 0.

The Piélou equitability index was calculated using the following formula (8):

In this study, J is defined as Pielou’s equitability index, H′ is Shannon's diversity index, S is the total number of species recorded in the ecosystem under consideration, and ln is the natural logarithm. Ln S is the theoretical maximum diversity value. The J equitability index quantifies the distribution of individuals across the species present in an ecosystem. It facilitates the assessment of population distribution across species within a plantation, potentially unveiling significant ecological dynamics such as the dominance of one species over others. The J index ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more balanced environments, and 1 representing the maximum attainable value. The student’s t-test assessed the equality of the mean values of Shannon's diversity index, Simpson's diversity index, and Pielou's equitability index.

The Shannon-Wiener, Simpson, and Piélou indices were selected based on their demonstrated capacity to furnish pertinent information concerning biodiversity. These indices were chosen to support the study's objective of characterising the floristic diversity and ecological dynamics of rubber plantations in Sankuru. These indices enabled the exploration of the complex relationships between plantation management, species diversity, and the ecosystem services provided by these plantations. This exploration contributed to a better understanding of the mechanisms of conservation and sustainable management of natural resources in this region.

2.3.3. Assessing the Similarity of Different Plantations

The degree of floristic similarity between different rubber plantation sites is determined using Sørensen's similarity coefficient. This coefficient is a quantitative metric that quantifies the degree of similarity between two environments [

37]. The coefficient is calculated by the following formula (9):

In ecological analysis, Sørensen's coefficient of similarity (Cs) is a metric that quantifies the degree of similarity between two biological communities, or environments, A and B. The coefficient is calculated as follows: Cs = a + b – c, where a is the number of species common to environments A and B, b is the number of species found in environment B, and c is the number of species found in environment A. This coefficient measures the similarity between the two environments regarding their floral composition. This index is frequently employed in ecological studies to compare the specific composition of diverse plant communities [

36]. In this study, we used this coefficient to assess the floristic similarity between different rubber plantations, specifically between state and peasant plantations, to elucidate the similarities and differences in the species present. This is imperative for the analysis of local biodiversity and the management of these ecosystems. This analysis is crucial for assessing the role of historical rubber plantations in terms of biodiversity conservation and for formulating recommendations for the sustainable management of natural resources. The range of Cs values is from 0 to 100%.

The greater the number of species common to the plantations, the more Cs approaches 100%. Conversely, when the floristic dissimilarity is high, the similarity coefficient approaches 0. It is widely accepted that two environments are considered similar when the similarity coefficient is greater than or equal to 50%. Conversely, if the similarity coefficient is less than 50%, it is concluded that there is an absence of similarity between the floristic lists of the environments in question [

36].

The decision to use Sørensen's coefficient of similarity in this study is based on its ability to comparatively analyse the floristic composition of different plantation types, particularly between state and peasant rubber plantations in Sankuru. This index has facilitated the acquisition of pivotal information regarding the similarity of two distinct plantation types, a prerequisite for comprehending the repercussions of management practices (state versus peasant) on floristic diversity. Furthermore, it offers a reliable instrument for evaluating the consequences of natural regeneration, silvicultural interventions, and environmental disturbances on the structure of rubber plantations. This is a pivotal step in formulating strategies for the sustainable management and conservation of these ecosystems in the Sankuru region.