1. Introduction

Microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and algae play a significant role in the corrosion of metal objects. Over time, exposure to terrestrial or aquatic environments degrades the metal or alloy components of artifacts. The extent and nature of corrosion depend on the type of metal and the environmental conditions to which the object has been exposed. Most studies on the corrosion of metal works of art tend to underestimate microbial activity at excavated sites, even though the occurrence of microbial-induced corrosion processes in nature is well documented. There is no reason to exclude these processes from objects of cultural and artistic significance [

1]. Bacteria are the most common cause of biocorrosion, with different species playing distinct roles.

Among bacterial families, nitrate-reducing bacteria (NRB) have been extensively studied for their role in microbial-induced corrosion in aquatic environments. These bacteria are environmentally significant, often comprising up to 50% of the microbial population in aquatic systems [

2,

3]. Notably,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an NRB bacterium, has been widely documented for its essential role in microbial-induced corrosion processes on various metals, including copper surfaces [

4,

5,

6]. Given the widespread presence of P. aeruginosa in the Mediterranean Sea [

7] and the Mediterranean location of the authors' institutions, this bacterium was selected as the focus of the study.

To explore sustainable conservation strategies, we first investigated the antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of plant extracts against

P. aeruginosa in vitro, and then tested the same plant extracts against the bacterial colonies developed on samples of copper and its alloys. Despite being used in a few cases as an antimicrobial agent [

7], copper is susceptible to microbial corrosion [

8].

Copper and its alloys were chosen because of their important historical and cultural significance in the Mediterranean and because many artifacts recovered from the sea are made of copper-based metals.

The plants selected for testing are known to be effective corrosion inhibitors for modern and archaeological metals, as shown in studies [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, their effectiveness against biocorrosion caused by microorganisms remains unproven.

We opted for two plants: Aloe vera and Opuntia ficus-indica (prickly pear), which grow spontaneously in practically every country around the Mediterranean.

A. vera contains several secondary metabolites that account for its particular properties: anthraquinones, including aloin and emodin, which exhibit anti-bacterial activities [

15]; phenolic compounds, which are known for their antioxidant properties [

16]; saponins, which have cleansing and antiseptic properties [

15]; carotenoids, including zeaxanthin, α-carotene, and β-carotene, which are known for their antioxidant activities [

15].

Using

A. vera extract to combat biocorrosion on metallic artifacts could be a promising approach. This plant contains secondary metabolites that can act as natural corrosion inhibitors. Studies have shown that

A. vera extract can significantly inhibit steel corrosion mediated by aerobic iron-oxidizing bacteria and anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacteria. The inhibition efficiency can range from 66% to 100% depending on the concentration [

17]. The extract forms a protective film on the metal surface, preventing further corrosion. This film is formed due to the adsorption of active compounds present in

A. vera [

18].

A. vera extract is an environmentally friendly alternative to traditional synthetic corrosion inhibitors, often toxic and environmentally harmful [

18]. The extract can be prepared in various concentrations and applied to the metal surface for practical use. Studies have used 10% to 80% (v/v) concentrations to achieve effective results [

17].

O. ficus-indica contains several active secondary metabolites that contribute to its various biological activities. Phenolic compounds have strong antioxidant properties [

19]; flavonoids are known for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities [

19]; and tannins have astringent properties and can also act as natural corrosion inhibitors [

19].

The antioxidant and astringent properties of these metabolites can be beneficial for biocorrosion. These compounds can form a protective layer on the metal surface to help prevent corrosion. While specific studies on using O. ficus-indica for biocorrosion are limited, the presence of these bioactive compounds suggests potential for such applications.

Particular attention must be paid to the cleaning phase in conserving metal artifacts. The cleaning process should eliminate residues without causing further damage, respecting the principles of minimal intervention and reversibility, primarily because these methods may be successfully used to restore and conserve metals.

Extracts from these plants as anti-corrosives would represent an essential step in the search for alternative, natural, economical, and eco-sustainable materials for restoring and conserving metallic artifacts.

2. Methods

This study used a bacterium, two plant extracts, various metal samples, and an antibiotic. Two types of experiments were performed: antibacterial and anti-biofilm. Depending on the specific test, multiple samples were prepared.

2.1. P. aeruginosa

P. aeruginosa is a widespread gram-negative bacterium. We used a culture obtained from the Public Health Institute of Dubrovnik-Neretva County for our target. For the liquid cultures (in biological tubes), a tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Komed, Croatia) was used for bacterial growth, with a concentration of 105 CFU (colony-forming units) per mL. For the solid cultures (in Petri dishes), a tryptic glucose–yeast agar culture medium (Biolife, Italy) was used for bacterial growth. Pure bacterial cultures were isolated after incubating the tubes or dishes at 37 °C for 24 h.

2.2. The Plant Extracts

The extract of

O. ficus-indica was prepared using the maceration method [

20]. The cladodes were cleaned with ethanol and peeled. The inner pulp was cut into small pieces, transferred to a beaker, and covered with distilled water. After 24 h in the dark, the gel was formed and collected by filtration.

The A. vera extraction procedure consisted of wiping the leaf with ethanol, peeling it, and cutting it horizontally into two parts along its entire length. The internal gel was then collected with a spoon and blended to achieve homogeneous consistency.

2.3. Metal Samples

Several metal samples were prepared for testing purposes. The samples (3x3 cm2) were cut from pure copper, bronze (copper and tin), and brass (copper and zinc) sheets with a thickness of 1 mm. The samples were cleaned of impurities and patina with sandpaper, then sterilised with 96% ethanol and autoclaved (Nüve OT 012). These techniques ensured the metal surface was clean, validating further test results.

2.4. Antibiotic

During the experiments, the common antibiotic azithromycin (Sumamed®) was used as a negative control to compare its established antibacterial effect with the potential bactericidal activity of the plant extracts.

2.5. Antibacterial Experiments

The antibacterial activity of plant extracts was assessed by determining the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and by performing a time-kill test to evaluate the extracts' concentration-dependent and time-dependent effectiveness in eliminating the P. aeruginosa. For this purpose, gel extracts of A. vera and O. ficus-indica were each dispersed in distilled water at four different concentrations, 12.5%, 25%, 50%, and 100% (v/v), ensuring a total volume of 1 mL for each mixture.

Eight microbiological test tubes were filled with 5 mL of TSB and 25 μL of P. aeruginosa (105 CFU/mL). Then, 1 mL of each O. ficus-indica extract suspension was added to one of four tubes, and 1 mL of each A. vera extract suspension to the other four. The samples containing TSB, P. aeruginosa, and the O. ficus-indica extract suspensions were labeled as 1-4, while those containing the A. vera extract suspensions were labeled as 5-8.

In addition, two control samples were prepared: one tube containing only 5 mL of TSB was used as the negative control (labeled as NC), while another tube containing 5 mL of TSB and 25 μL of bacterial suspension served as the positive control (labeled as PC). All ten samples (NC, PC, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8) were incubated at 37ºC for 24 hours. During the incubation, subsamples were taken after 3, 6, 18, and 24 hours to assess the time-dependent effectiveness of the extracts in eliminating the P. aeruginosa by spectrophotometric analysis and spread plate method [

21,

22].

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) defines in vitro resistance levels of specific bacteria to an antibiotic applied. The MIC value is the lowest concentration at which bacterial growth is completely inhibited. It can be determined by observing and comparing the turbidity of solutions: the dilution with the lowest concentration of the test material that exhibits no turbidity is the MIC [

22]. In this study, we determined the MIC of the antibiotic and the two plant extracts.

For the spectrophotometric analysis, 2 μL of each subsample was used to perform absorbance measurements at 625 nm by the spectrophotometer IMPLEN-NanoPhotometer N50 version. The absorptions obtained were used to quantify the number of bacteria in the tube by the equation A = εc𝓵, where A is absorption, ε is the extinction coefficient, c is the concentration of the bacterial solution, and ℓ is the path length.

For the spread-plate method (a microbiological technique used to grow and count bacteria), 1 mL of each subsample was taken and then diluted three times by a factor of ten. Specifically, 1 mL of the original solution was added to 9 mL of distilled water to obtain the first 1:10 dilution (10⁻¹). This process was repeated twice to achieve the second and third dilutions (10⁻² and 10⁻³, respectively). The result is four solutions with different concentrations.

From each dilution, 100 μL was taken and spread evenly over the surface of a solid nutrient agar plate to allow bacteria to grow into visible colonies at 37ºC for 24 hours. The bacterial colonies grown on plates were manually counted [

21], and the colony-forming unit (CFU) was used to estimate the number of colonies by the equation CFU/mL = (No. of colonies x dilution factor) / culture volume.

All experiments were replicated three times.

2.6. Anti-Biofilm Experiments

Only after completing the antibacterial experiments was it possible to evaluate the effect of the same plant extracts on the prepared metal samples. Two aspects of the extracts' anti-biofilm properties were investigated: their ability to prevent bacterial biofilm formation on the metal surface and their effectiveness in treating an already established biofilm.

To test the ability of extracts to prevent bacterial biofilm formation, four solutions were prepared and applied to metal samples, four of which were copper, bronze, and brass, resulting in 16 total samples. The first solution consisted of 500 μL of bacterial suspension of P. aeruginosa and served as a positive control. The other three solutions were prepared by mixing 500 μL of bacterial suspension with 100 μL of one of the antibacterial agents: the antibiotic (azithromycin) as a negative control, the extract of

O. ficus-indica, and the extract of

A. vera. The metal samples treated with these solutions were incubated at 37ºC for 48 hours. After this time, biofilm formation was seen on all metal samples, then the colonies formed on the metal surfaces were transferred to tryptic glucose yeast agar plates and washed with 100 μL of autoclaved distilled water. The 12 samples obtained were labeled as shown in

Table 1.

After 48 hours of incubation at 37ºC, the colonies on the plates were compared to visualize the differences in bacterial density.

To test the effectiveness of extracts in treating an already established biofilm, three samples of each metal were first exposed to 500 μL of bacterial suspension. The samples were then incubated at 37ºC for 72 hours to allow bacterial growth and biofilm formation on the metal surfaces. After incubation, one sample of each metal was left untreated as a control, while the remaining two samples were each treated with 500 μL of O. ficus indica extract or A. vera extract and then incubated again for 48 hours. After this, the colonies were transferred from the metal surfaces to microscope slides and stained with a methylene blue solution prepared by adding 0.8 g of methylene blue powder to 80 mL of distilled water and mixing for 45 minutes at 600 rpm on a magnetic stirrer. In this way, when the slide was placed under the microscope (Olympus optical, Japan, CH20BIMF200), it was possible to see the stained blue bacteria against a colorless background and visualise the differences in bacterial density.

2.7. Evaluation and Cleaning of Metal Samples

All samples were visually examined after the biofilm removal tests to check for residues or surface changes. The samples were then cleaned with a damp cotton cloth to remove the traces of extracts from the surface.

3. Results

3.1. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

To determine the MIC of the plant extracts, the tube samples NC, PC, 1, 2, 3, and 4 (for

O. ficus-indica) and NC, PC 5, 6, 7, and 8 (for

A. vera) were observed and compared (

Figure 1a,b). The absence of turbidity in samples 3 and 7 indicated that, for both extracts, the MIC was 50% (v/v).

3.2. Time-Kill Test

The results of the time-kill tests, expressed as the average bacterial cell counts from three experimental series, using both spectrophotometric analysis and the spread-plate method, were analysed as killing curves by plotting the log10 colony-forming unit per milliliter (CFU/mL) versus time (hours). Antimicrobial agents can kill (bactericidal activity) or inhibit bacterial growth (Bacteriostatic activity). A reduction of at least 3 log10 colony-forming units per milliliter compared to the initial bacterial count indicates that the agent is bactericidal active, while a reduction of less than 3 log10 indicates bacteriostatic activity [

23,

24].

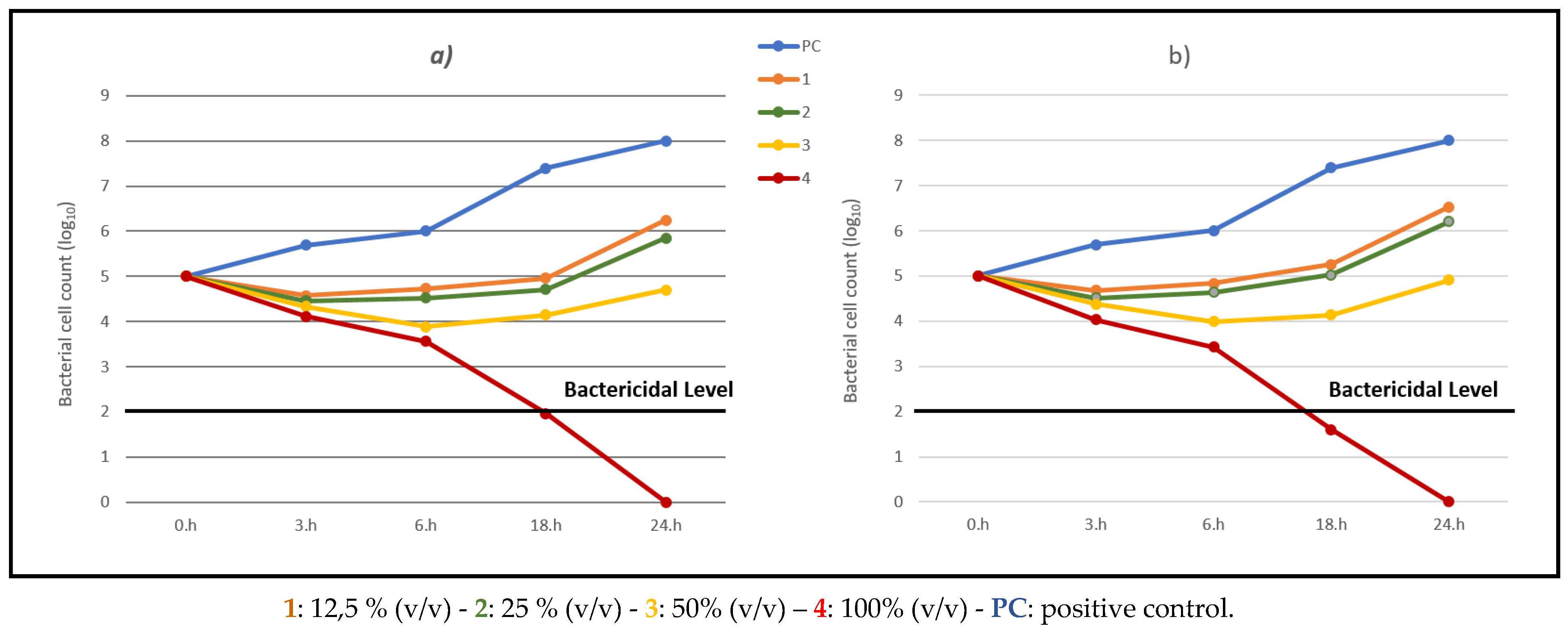

Figure 2a,b reports the killing curves for spectrophotometric analysis and the spread-plate method for the

O. ficus-indica extract.

The time-kill profiles show a consistent trend regardless of the methods used, confirming the validity of the two analytical approaches. As expected, bacterial growth in the positive control (PC) increased steadily over time. In contrast, the kill kinetic profiles for the sample treated with extract of

O. ficus-indica with 100% (v/v), 4, displayed a rapid bactericidal activity for the concentration, showing a ≥3 log10 reduction in viable cell count relative to the initial value after 18h of incubation (

Figure 2a,b).

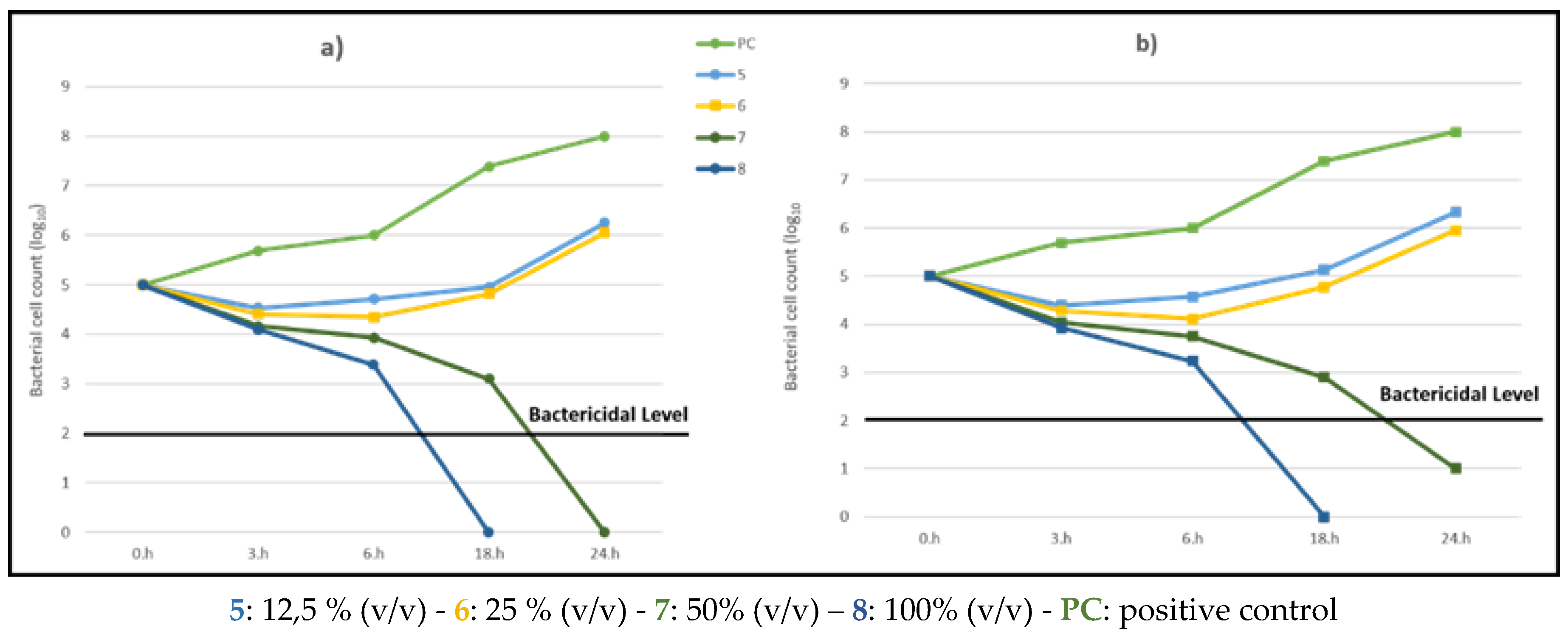

The killing curves for both spectrophotometric analysis and the spread-plate method for the

A. vera extract are reported in

Figure 3a,b. The two analytical approaches are still valid, but in this case the kill kinetic profiles of the samples treated with extracts of

A. vera with 50 and 100% (v/v) concentrations,

7 and

8, displayed a bactericidal activity with a ≥3 log10 reduction in viable cell count relative to the initial value after 18h and 24h of incubation, respectively.

Comparing the two extracts, we can conclude that A. vera has a higher bactericidal activity, showing a ≥3 log10 reduction already at a lower concentration.

3.3. Antibiofilm Experiments

3.3.1. Prevention of Biofilm Formation

Figure 3a–c show the differences in bacterial density for samples B1-B4, C1-C4, and Br1-Br4 (see Table 2). Cloudy or opaque areas indicate the presence of

P. aeruginosa biofilm, clear or transparent zones suggest the absence of bacterial growth, and dotted or uneven patterns represent areas where the biofilm was partially disrupted or eliminated.

The density is the highest for the positive control samples B1, C1, and Br1, while for samples B2, C2, and Br2, it is practically zero, as the antibiotic kills the bacterium. In the other samples, B3- B4, C3-C4, and Br3-Br4, the density decreased significantly compared with the positive samples. The best results were obtained with the extract of A. vera regardless of the type of metal, i.e., samples B4, C4, and Br4.

3.3.2. Prevention of Biofilm Formation

Figure 4a–c shows the results obtained for the stained samples (see section 3.6) by treating the metal samples with the plant extracts after forming a bacterial biofilm.

Figure 3.

Bacterial densities on (a) brass samples, (b) copper samples, and (c) bronze samples. Composition of treatment solutions: B1, C1, Br 1: Bacteria / B2, C2, Br2: Bacteria + Antibiotic/ B3, C3, Br3: Bacteria + O. ficus-indica extract / B4, C4, Br4: Bacteria + A. vera extract).

Figure 3.

Bacterial densities on (a) brass samples, (b) copper samples, and (c) bronze samples. Composition of treatment solutions: B1, C1, Br 1: Bacteria / B2, C2, Br2: Bacteria + Antibiotic/ B3, C3, Br3: Bacteria + O. ficus-indica extract / B4, C4, Br4: Bacteria + A. vera extract).

Figure 4.

Stained bacterial biofilm from (a) copper samples, (b) brass samples, and (c) bronze samples.

Figure 4.

Stained bacterial biofilm from (a) copper samples, (b) brass samples, and (c) bronze samples.

Regardless of the type of metal, the number of bacterial cells (blue-stained) is higher in the three positive controls, untreated samples, and lower in the treated samples. Also, in this case, the extract of A. vera is more effective than that of O. ficus-indica.

3.3.3. Evaluation of the Metal Surface Condition After Biofilm Removal and Cleaning Treatments

After the bacterial colonies were incubated and transferred, the samples were prepared to test the effectiveness of the plant extracts on pre-formed biofilms, as shown in

Figure 5.

It is important to note that, although the bacterial load on the three treated samples was significantly reduced, complete bacterial elimination was not achieved. For safety reasons and to ensure the inactivation of any remaining bacteria, all samples, including controls, were sterilized by autoclaving before further handling.

As visible in

Figure 5, the surface of all samples was stained: the visible stain on the untreated sample indicated that the bacterium formed a visible biofilm, and the stains on the remaining samples suggested that the corrosion inhibitors (plant extracts) also changed the surface appearance.

Plant extract traces were easily removed by cleaning with a soft cotton cloth slightly moistened with distilled water. This gentle mechanical measure was sufficient to remove most superficial residues and stains.

Figure 5.

Metal surface condition after biofilm removal and control samples of entreated metals, Bronze (Br), Copper (Cu), and Brass (B). Control samples bacteria: P. aeruginosa. / 1: Bacteria, 2: Bacteria + Antibiotic, 3: Bacteria + O. ficus-indica extract, 4: Bacteria + A. vera extract.

Figure 5.

Metal surface condition after biofilm removal and control samples of entreated metals, Bronze (Br), Copper (Cu), and Brass (B). Control samples bacteria: P. aeruginosa. / 1: Bacteria, 2: Bacteria + Antibiotic, 3: Bacteria + O. ficus-indica extract, 4: Bacteria + A. vera extract.

4. Discussion

The antibacterial and antibiofilm properties of

A. vera and

O. ficus-indica extracts against

P. aeruginosa were confirmed through both the spread-plate method and spectrophotometric analysis. The secondary metabolites present in

A. vera, such as anthraquinones, phenolic compounds, saponins, and carotenoids, are likely to contribute to its strong antibacterial activity. Similarly, the phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and tannins in

O. ficus-indica play a crucial role in inhibiting bacterial growth and biofilm formation. These findings align with previous studies that have demonstrated the antimicrobial properties of these plants [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

The spread-plate method and spectrophotometric analysis were employed to determine if one method could be advantageous when working with a plant extract. The results show no differences between the two approaches. While the spectrophotometric method offers the advantage of being faster, the spread-plate method requires only basic laboratory equipment, making it accessible and cost-effective. Both methods proved to be consistent and repeatable.

The anti-biofilm tests were presented in the second part of this study. First, we demonstrated that the

P. aeruginosa forms a biofilm on all tested copper metal samples, although these are often described in the literature as metals with antibacterial properties [

30,

31]. This result confirms our original hypothesis that these metals are susceptible to microbial corrosion despite their use as antimicrobial agents. A relatively recent review on this topic reports that microorganisms can degrade the quality of many metals, including aluminum, copper, nickel, and titanium, even if most microbiological research has focused on the role of microorganisms in the corrosion of iron-containing ferrous metals, such as carbon and stainless steel [

32].

Indeed, it is frequently reported in the literature that the formation of a biofilm on the metal surface is the first step of bio-corrosion, implying that the metabolites present at the biofilm–metal interface are likely to be more relevant to the processes related to microbial-induced corrosion [

33,

34]. Inhibiting the formation of a biofilm or treating an existing biofilm can prevent bio-corrosion and metal deterioration. The

A. vera and

O. ficus-indica extracts were tested for these purposes.

The potential of these two plant extracts as metal corrosion inhibitors [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] is well known, while their possible impact on biocorrosion had not been thoroughly explored until this study. Many different methods, including chemical techniques, spectrophotometric methods, electron microscopy techniques, stereo microscopy methods, etc, can usually analyze anti-biofilm activities. In our study, the precise quantification of bacterial cells was not the primary objective; instead, it was on comparing treated and untreated samples to assess where the biofilm had decreased.

Our results show that both plant extracts are effective in preventing biofilm and thus biocorrosion when applied before bacterial colonization, and that they can effectively eliminate P. aeruginosa biofilm once it has already formed on metal surfaces.

After biofilm removal, we examined the metal surfaces for possible future applications in conserving and restoring metal artifacts. Stains were observed on the treated metals, but these could be partially removed with a soft cotton cloth moistened with distilled water. This is in line with previous studies that have shown the reversibility of

O. ficus-indica extract [

35].

Due to their low thickness, the protective layers of green corrosion inhibitors of archeological metal artifacts are usually invisible. However, the inhibitors lead to visible changes in other cases, and all layers are chemically stable in the environment. Due to their thinness, they are not resistant to mechanical removal [

18].

In these cases, standard conservation and restoration cleaning techniques should be applied to copper and copper alloys to ensure complete removal of active corrosion.

The application method is crucial in ensuring uniform coverage and minimal visual alteration. In previous tests conducted by some of the authors (unpublished), the same extracts were applied by brushing or immersing the metal samples in the extract solution for two hours. The brushed samples exhibited surface discoloration due to uneven application, as the liquid collected in certain areas due to surface tension. In contrast, immersion resulted in a more uniform distribution of the extract. Since conservation practice prioritises preserving an object’s original appearance, brushing may not be a suitable application method for these extracts [

36].

These observations lead us to believe immersion would have provided a more homogeneous application and minimized surface alterations in these tests.

5. Conclusions

The results reported in this study demonstrated that:

- P. aeruginosa forms a biofilm on all tested metal surfaces, confirming that biological activity can result in biocorrosion of copper and its alloys.

- A. vera and O. ficus-indica extracts effectively prevent biofilm formation when applied prior to bacterial colonization.

- Both extracts can eradicate established biofilms by eliminating bacterial cells on the metal surface.

The use of plant extracts as biocorrosion inhibitors offers significant environmental benefits, providing a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative to synthetic chemicals. The practical application of these extracts in cultural heritage conservation is promising, given their ease of preparation and effectiveness.

A key distinction between using these extracts as simple corrosion inhibitors and as biocorrosion inhibitors lies in their dual functionality. As simple corrosion inhibitors, A. vera and O. ficus-indica extracts form a protective layer on the metal surface, reducing the chemical or electrochemical corrosion rate. However, as biocorrosion inhibitors, these extracts also target the microorganisms responsible for biocorrosion. The secondary metabolites in the extracts inhibit bacterial growth and biofilm formation, providing a comprehensive approach to metal conservation. This dual functionality enhances the potential of these plant extracts in preserving metal artifacts from both chemical and biological degradation.

A key limitation of this study for conservation applications is that the extracts left visible traces on the metal surface. While these stains were partially removed with simple wet cleaning, slight surface alterations remained, indicating the need for standard conservation cleaning techniques to completely remove biofilm residues and corrosion products.

Future research should concentrate on:

- Optimizing the application method to reduce visual impact on metal surfaces.

- Test the extracts on archaeological objects to evaluate their practical effectiveness and reversibility.

In conclusion, this study offers strong evidence that A. vera and O. ficus-indica extracts could be sustainable alternatives for preventing and mitigating biocorrosion, with potential applications in conserving and restoring metal cultural heritage objects.

Author Contributions

Writing - Original Draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, C.Ö., Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing, visualization, L.E., Methodology. Writing - Review & Editing, M-K., Methodology, Formal analysis., Writing - Review & Editing, M.B.Š., Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, L.S., Supervision, Visualization, Validation, S.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was supported by TECH4YOU - Technologies for Climate Change Adaptation and Quality of Life Improvement. CODE, ECS_00000009 - CUP C43C22000400006.

Acknowledgments

C.Ö. acknowledges the project TECH4YOU for his doctoral fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Del Junco, A. S.; Moreno, D. A.; Ranninger, C.; Ortega-Calvo, J. J.; Sáiz-Jiménez, C. Microbial induced corrosion of metallic antiquities and works of art: a critical review. Inter. Biodeter. Biodegr. 1992, 2, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuk, S.; Azam, A. H.; Miyanaga, K.; Tanji, Y. The contribution of nitrate-reducing bacterium Marinobacter YB03 to biological souring and microbiologically influenced corrosion of carbon steel. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020, 156, 107520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Du, C.; Li, X. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of X80 pipeline steel by nitrate reducing bacteria in artificial Beijing soil. Bioelectrochemistry 2020, 135, 107551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, M.; Du, M.; Zheng, Z.; Ma, L. Mechanism underlying the acceleration of pitting corrosion of B30 copper–nickel alloy by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1149110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; L Narenkumar, J.; Rajasekar; A. et al. Biocorrosion of mild steel and copper used in cooling tower water and its control. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W. , Pu, Y., Gu, T., Chen, S., Chen, Z., & Xu, Z. Biocorrosion of copper by nitrate-reducing Pseudomonas aeruginosa with varied headspace volume. Inter. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2022, 171, 105405. [Google Scholar]

- Mates, A. The significance of testing for Pseudomonas aeruginosa in recreational seawater beaches. Microbios. 1992, 71, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amendola, R.; Acharjee, A. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of copper and its alloys in anaerobic aqueous environments: a review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 806688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzidia, B.; Barbouchi, M.; Rehioui, M.; Hammouch, H.; Erramli, H.; Hajjaji, N. Aloe vera mucilage as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for bronze in chloride media: Combining experimental and theoretical research. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2023, 35, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiola, O. K.; James, A. O. The effects of Aloe vera extract on corrosion and kinetics of corrosion process of zinc in HCl solution. Corros. Sci., 2010, 52, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Parra, J.R.; Di Turo, F. Using Plant Extracts as Sustainable Corrosion Inhibitors for Cultural Heritage Alloys: A Mini-Review. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, G. A.; Abdel-karim, A. M.; Saleh, S. M.; El-Meligi, A. A.; El-Rashedy, A. A. Corrosion inhibition of copper alloy of archaeological artifacts in chloride salt solution using Aloe vera green inhibitor. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Acosta, A.A.; González-Calderón, P.Y. Opuntia ficus-indica (OFI) Mucilage as Corrosion Inhibitor of Steel in CO2-Contaminated Mortar. Materials 2021, 14, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulos, V.; Boyatzis, S.C.; Giannoulaki, M.; Guilminot, E.; Zacharopoulou, A. Organic Green Corrosion Inhibitors Derived from Natural and/or Biological Sources for Conservation of Metals Cultural Heritage. In: Joseph, E. (eds) Microorganisms in the Deterioration and Preservation of Cultural Heritage. 2021, Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Dong-Myong, K.; Ju-Yeong, J.; Hyung-Kon, L.; Yong-Seong, K.; Yeon-Mea, C. Determination and Profiling of Secondary Metabolites in Aloe vera, Aloe Arborescens and Aloe Saponaria. Biomed. J. Sci. & Tech. Res. 2021, 40, 32555–32563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N.S.; Singh, H.B.; Vaishnav, A. Mechanistic understanding of metabolic cross-talk between Aloe vera and native soil bacteria for growth promotion and secondary metabolites accumulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1577521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwa, O.K.; Iyalla, D.; Abu, G.O. Inhibition of bio-corrosion of steel coupon by sulphate reducing bacteria and iron oxidizing bacteria using Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis) extracts. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 2017, 21, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Karim, A.M.; El-Shamy, A.M. A Review on Green Corrosion Inhibitors for Protection of Archeological Metal Artifacts. J. Bio. Tribo Corros., 2022, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarena-Rangel, N.G.; Barba-De la Rosa, A.P.; Herrera-Corredor, J.A.; et al. Enhanced production of metabolites by elicitation in Opuntia ficus-indica, Opuntia megacantha, and Opuntia streptacantha callus. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2017, 129, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ex 15 ora 20.

- Scognamiglio, F.; Mirabile Gattia, D.; Roselli, G. , Persia, F.; De Angelis, U.; Santulli, C. Thermoplastic starch films added with dry nopal (opuntia Ficus Indica) fibers. Fibers. 2019, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, Ç.; Erol, A.; Scrano, L. Comparative examination of in vitro methods to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of biomaterials. Emergent mater. 2024, 7, 2605–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Weir, M.D.; Fouad, A.F.; Xu, H.H. Time-kill behaviour against eight bacterial species and cytotoxicity of antibacterial monomers. J Dent 2013, 41, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, P. J.; Jones, C. H.; Bradford, P. A. (2007). In vitro antibacterial activities of tigecycline and comparative agents by time-kill kinetic studies in fresh Mueller-Hinton broth. Diagn. Micr. Infec. Dis., 2007, 59, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J. H.; Jamaludin, N. S.; Khoo, C. H.; Cheah, Y. K.; Halim, S. N. B. A.; Seng, H. L.; Tiekink, E. R. In vitro antibacterial and time-kill evaluation of phosphanegold (I) dithiocarbamates, R 3 PAu [S 2 CN (iPr) CH 2 CH 2 OH] for R= Ph, Cy and Et, against a broad range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Gold Bulletin, 2014, 47, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesbah, M.; Douadi, T.; Sahli, F.; Issaadi, S.; Boukazoula, S.; Chafaa, S. Synthesis, characterization, spectroscopic studies and antimicrobial activity of three new Schiff bases derived from Heterocyclic moiety. J. Mol. Struct., 2018, 1151, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennouri, M.; Ammar, I.; Khemakhem, B.; Attia, H. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of Opuntia ficus-indica F. Inermis (Opuntia ficus-indica Pear) Flowers. J Med Food, 2014, 17, 908–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbab, S.; Ullah, H.; Weiwei, W.; Wei, X.; Ahmad, S.U.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J. Comparative study of antimicrobial action of Aloe vera and antibiotics against different bacterial isolates from skin infection. Vet Med Sci. 2021, 7, 2061–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitgeb, M.; Kupnik, K.; Knez, Ž.; Primožič, M. Enzymatic and Antimicrobial Activity of Biologically Active Samples from Aloe arborescens and Aloe barbadensis. Biology 2021, 10, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurashi, A.S.; Al Masoudi, L.M.; Hamdi, H.; Abu Zaid, A. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant, Antiviral, Antifungal, Antibacterial and Anticancer Potentials of Opuntia ficus indica Seed Oil. Molecules 2022, 27, 5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, I.; Parkin, I.P.; Allan, E. Copper as an antimicrobial agent: recent advances. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 18179–18186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y. G.; LI, H. Y.; Yuan, X. Y.; Jiang, Y. B.; Xiao, Z. A.; Zhou, L. Review of copper and copper alloys as immune and antibacterial element. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China, 2022, 32, 3163–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Gu, T.; Lovley, D. R. Microbially mediated metal corrosion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 2023, 21, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, Y. T.; Power, A.; Cozzolino, D.; Dinh, K. B.; Ha, B. S.; Kolobaric, A.; et al. Analytical characterisation of material corrosion by biofilms. Journal of Bio-and Tribo-Corrosion, 2022, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M. K.; Lavanya, M. Microbial influenced corrosion: understanding bioadhesion and biofilm formation. Journal of Bio-and Tribo-Corrosion, 2022, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuele, L.; Dujaković, T.; Roselli, G.; Campanelli, S.; Bellesi, G. The Use of a Natural Polysaccharide as a Solidifying Agent and Color-Fixing Agent on Modern Paper and Historical Materials. Organics 2023, 4, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuele, L.; Kotlar, M.; Novalija, J.M.; Scrano, L.; Kurajica, S. Testing the green corrosion inhibitors prickly pear and aloe vera on an archeological iron sample. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2025, (submitted).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).