Submitted:

22 August 2024

Posted:

27 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

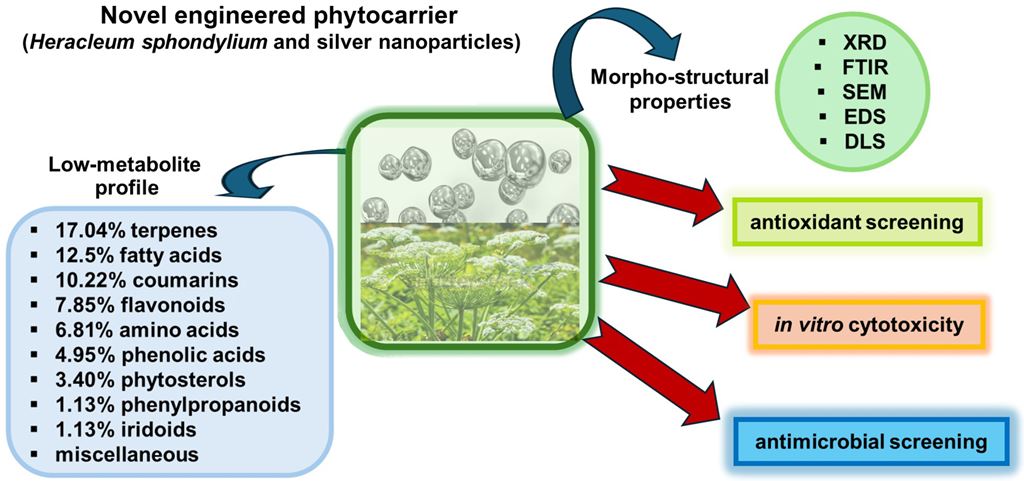

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

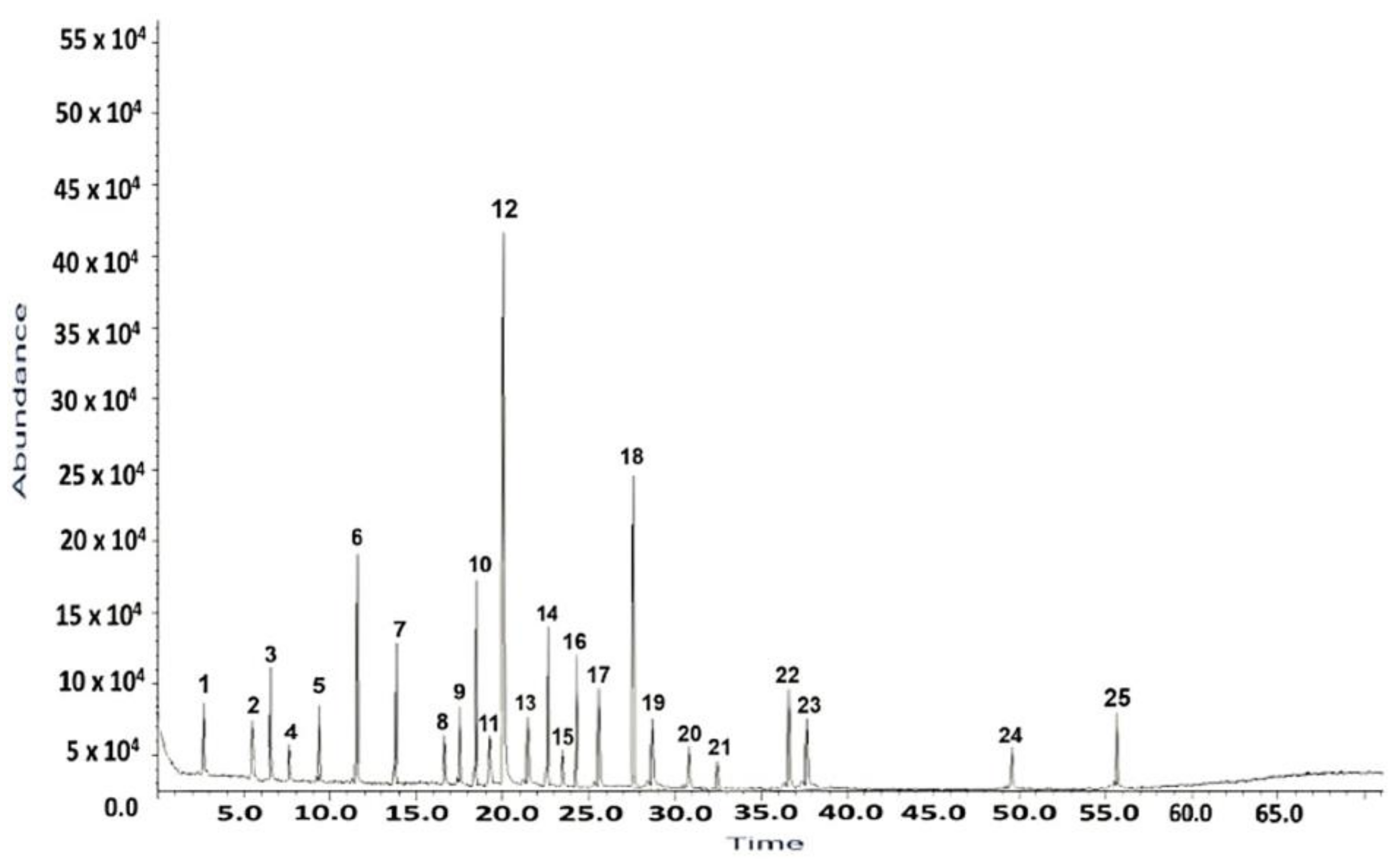

2.1. GC–MS Analysis of H. sphondylium Sample

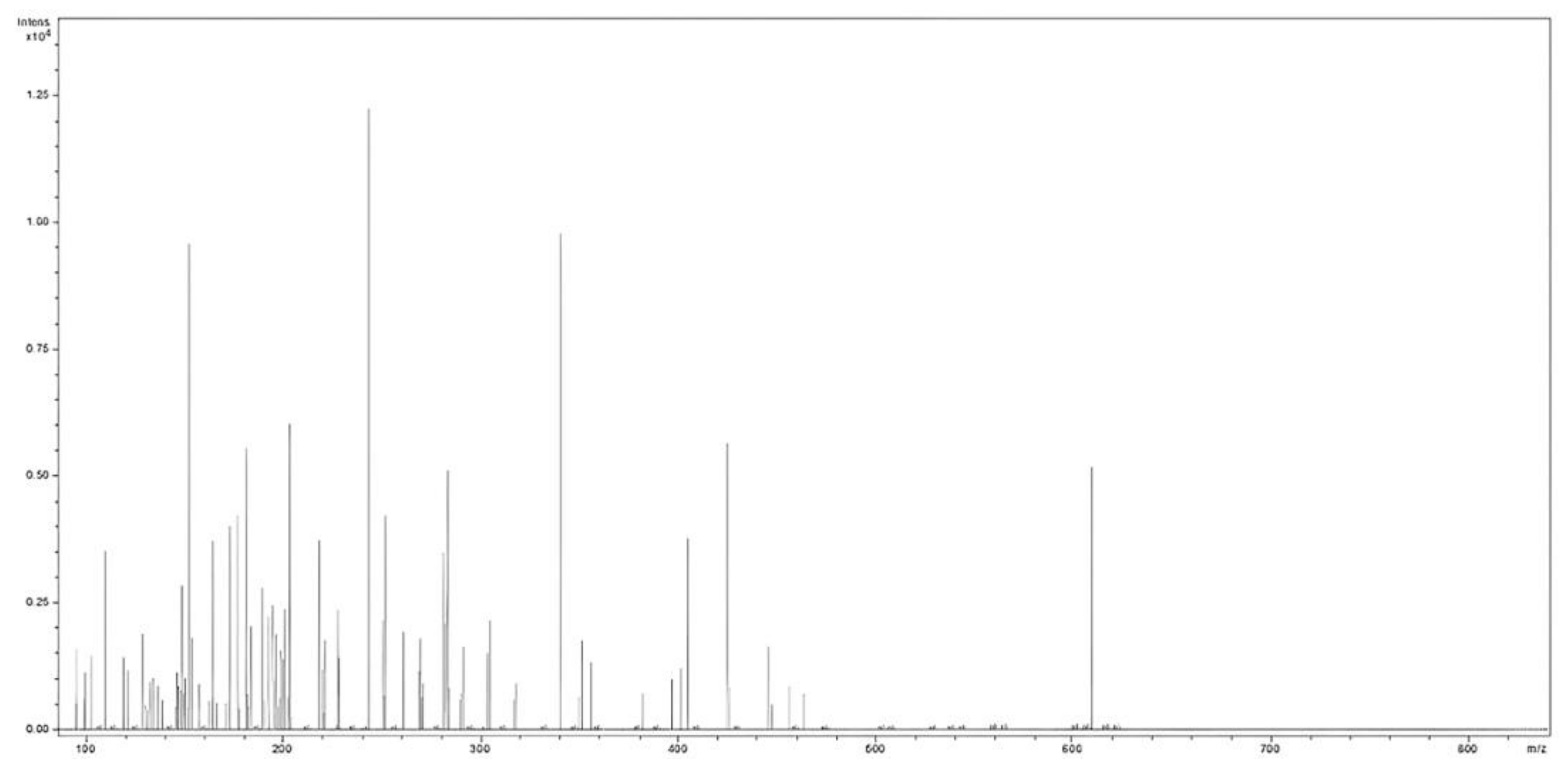

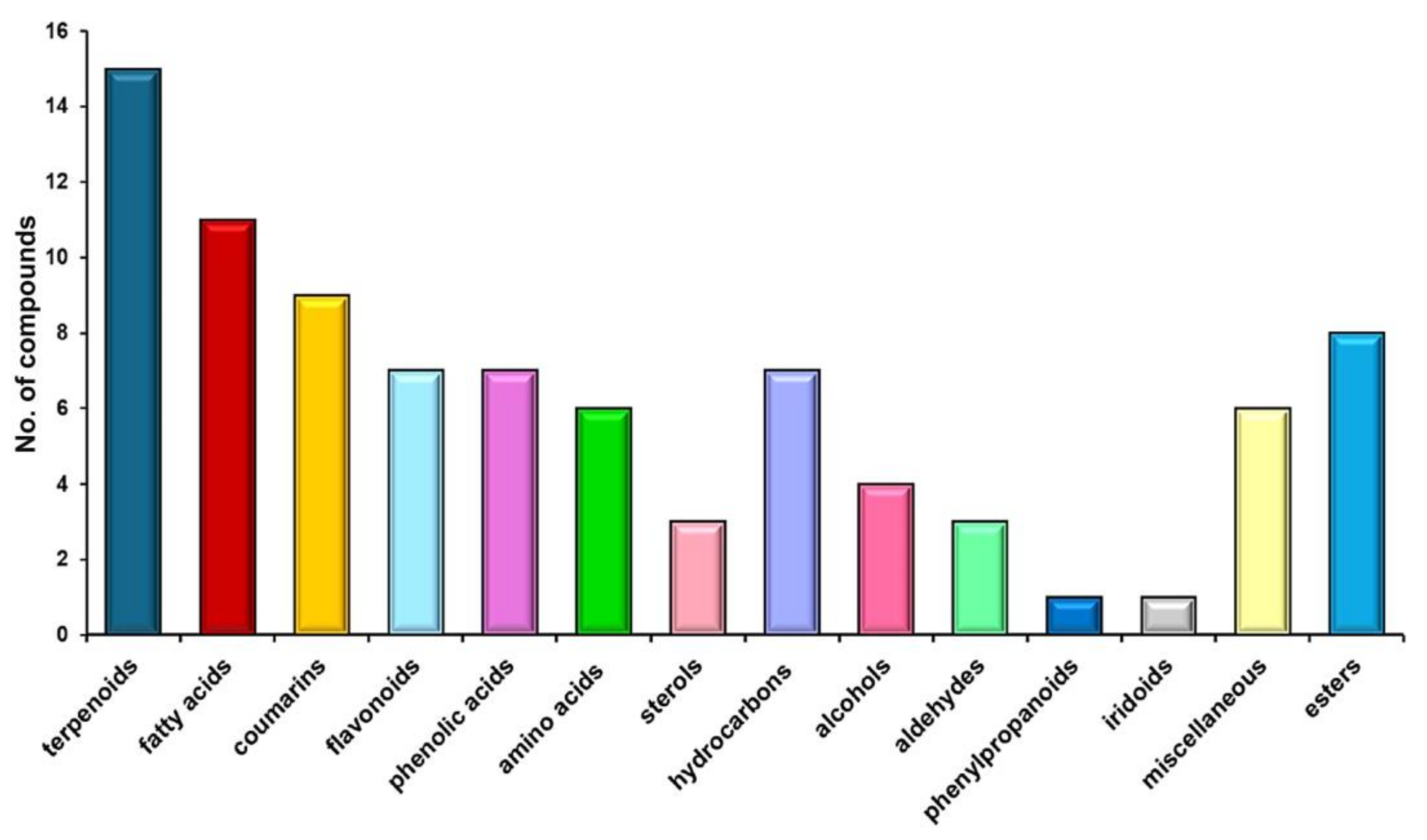

2.2. MS Analysis of H. sphondylium Sample

2.3. Chemical Screening

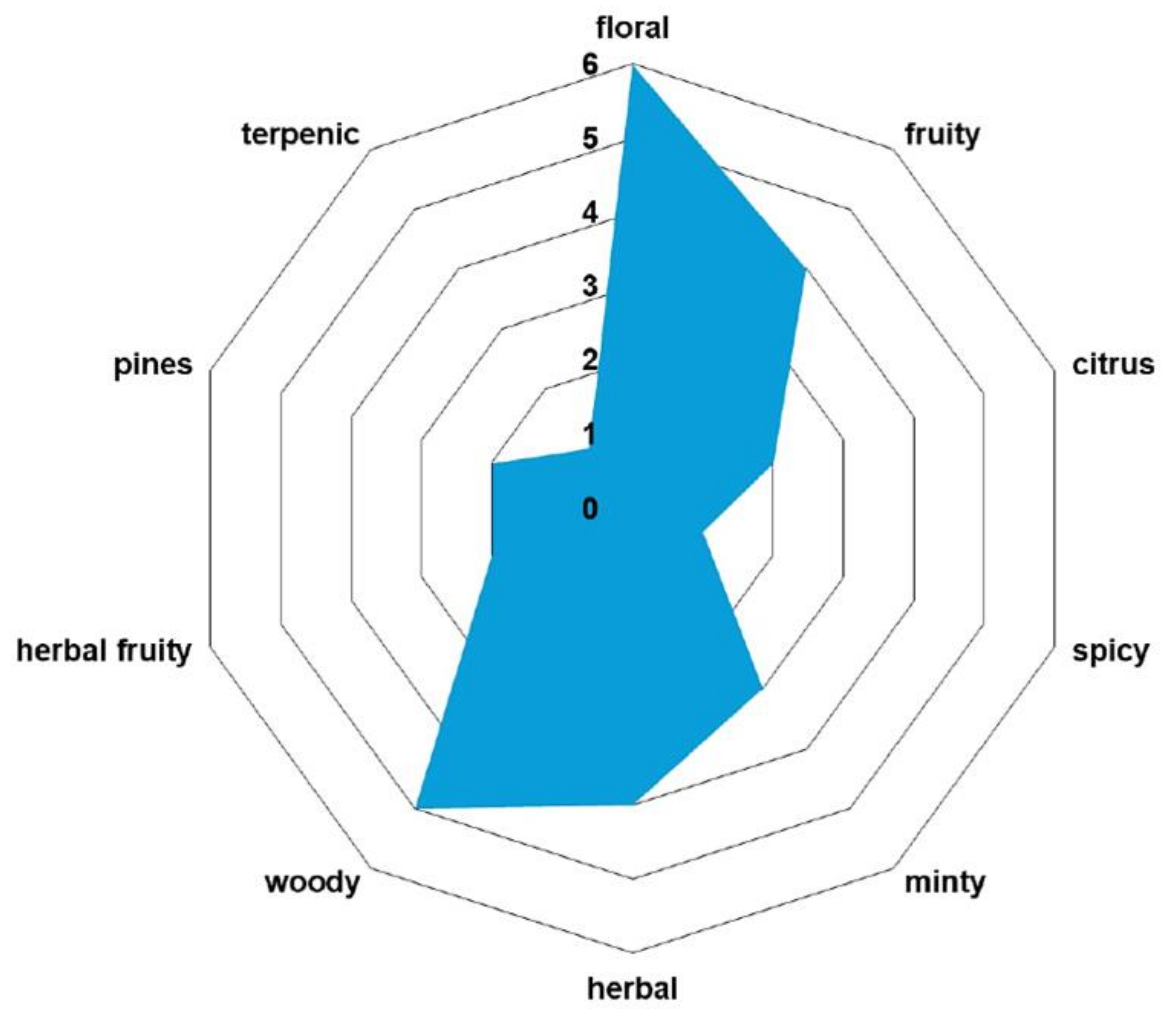

2.4. Key Aroma-Active Compounds Forming Different Flavor Characteristics

2.5. Phytocarrier Engineered System

2.5.1. FTIR Spectroscopy

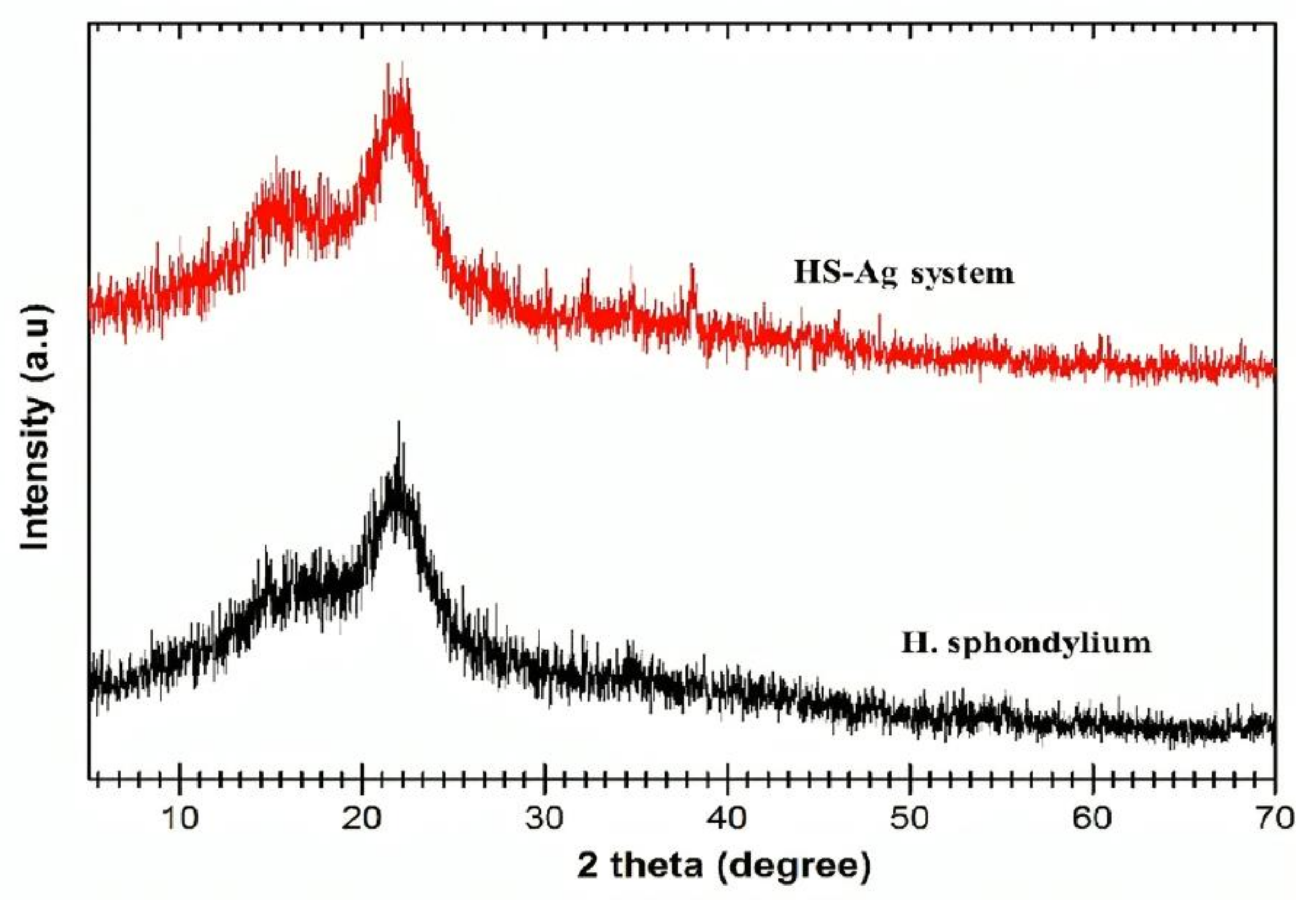

2.5.2. XRD Analysis

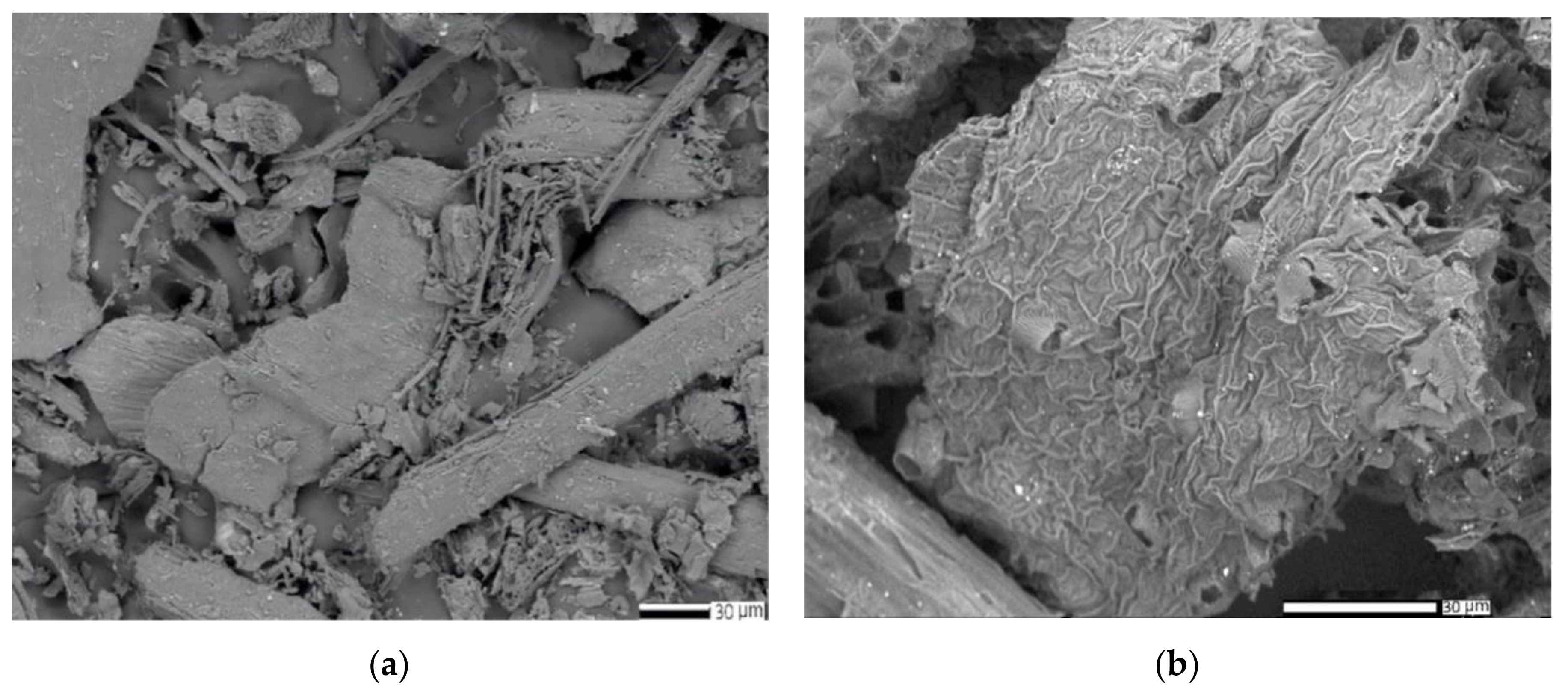

2.5.3. SEM and EDX Analysis

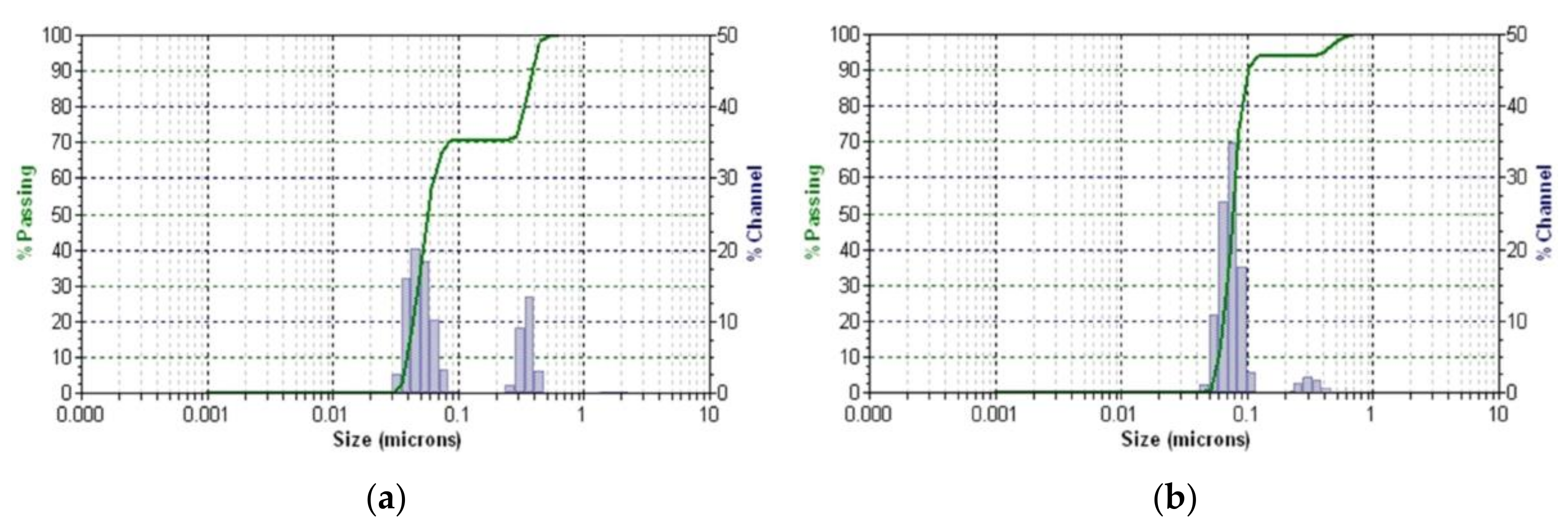

2.5.4. DLS Analysis

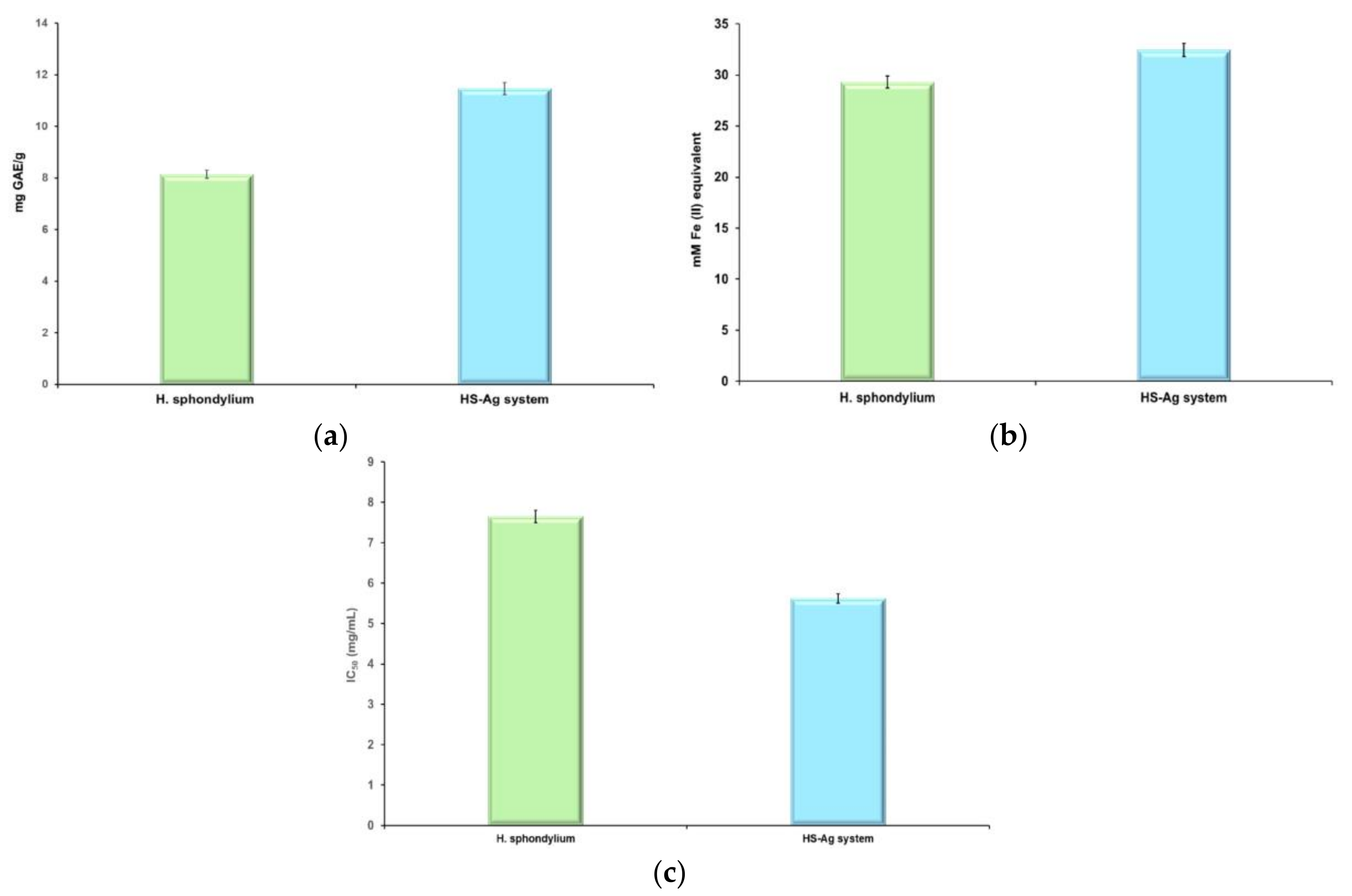

2.6. Screening of Antioxidant Potential

2.7. Antimicrobial Screening

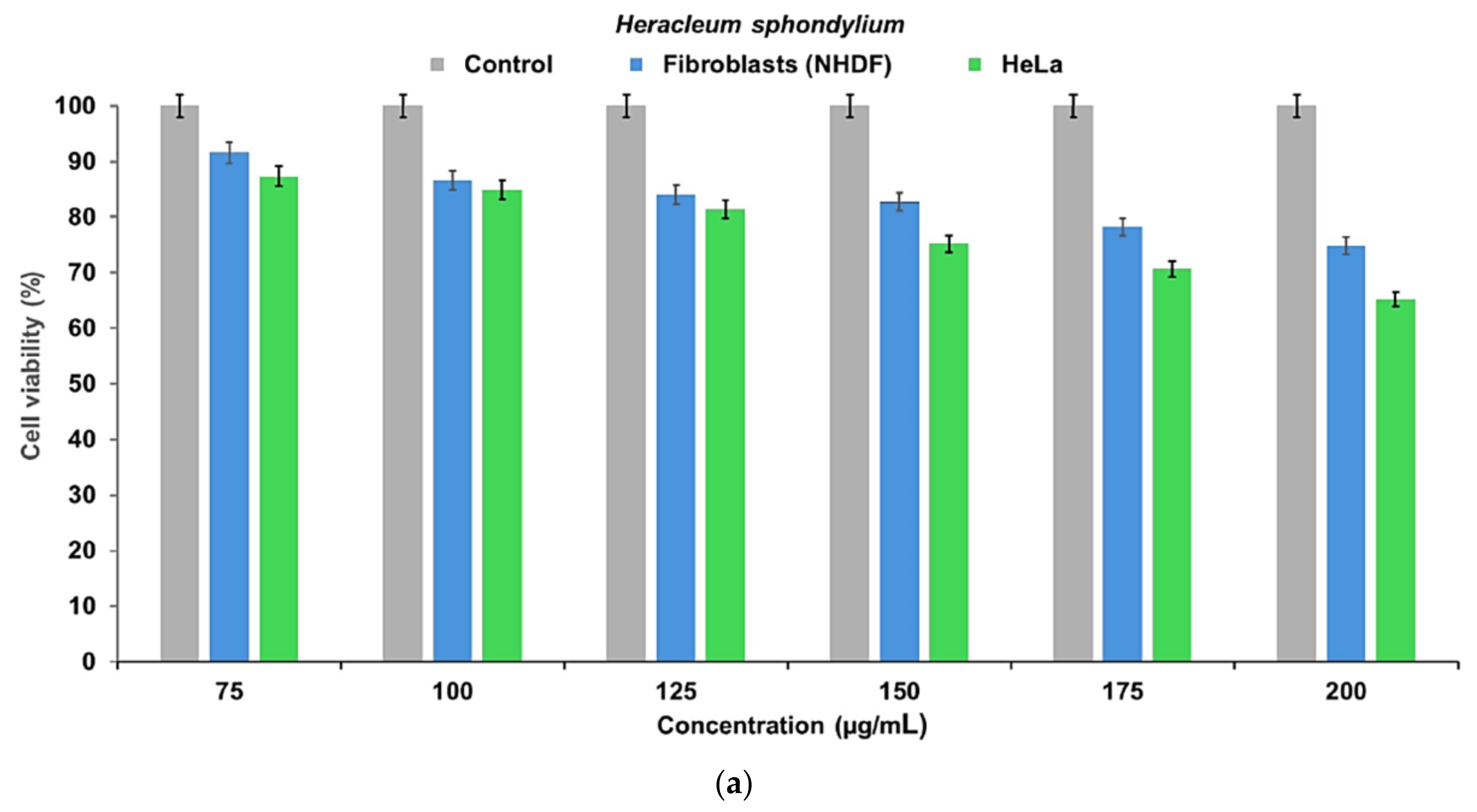

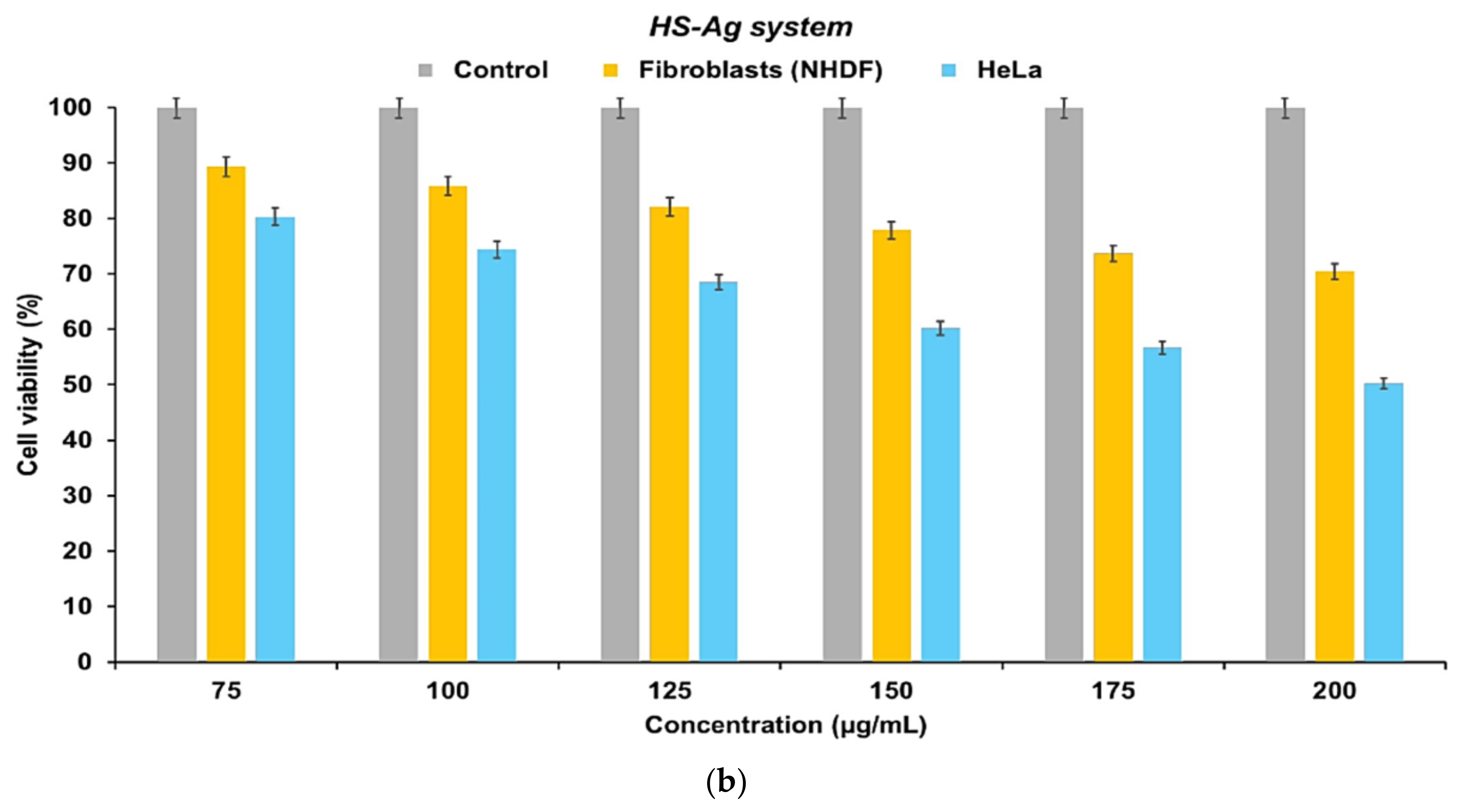

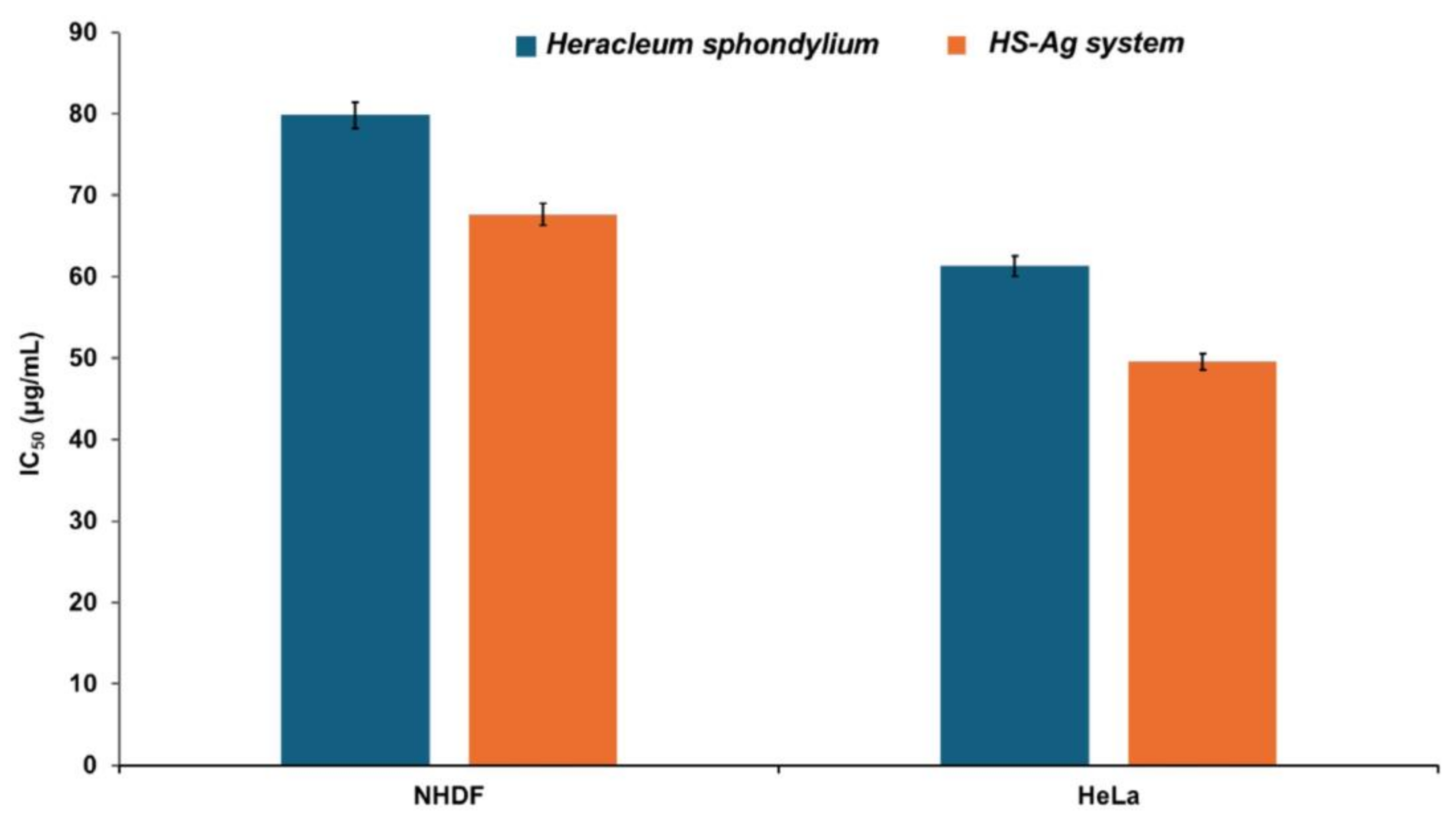

2.8. Cell Viability Assay

3. Discussion

3.1. H. sphondylium Low-Metabolic Profile

3.2. New Phytocarrier System with Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Cytotoxicity Potential

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Cell Lines

4.3. Bacterial Strains

4.4. Plant Material

4.5. Preparation of AgNPs

4.6. Plant Sample Preparation for Chemical Screening

4.7. GC–MS Analysis

4.7.1. GC–MS Separation

4.7.2. Mass Spectrometry

4.8. Phytocarrier System Preparation (HS-Ag System)

4.9. Characterization of HS-Ag System

4.9.1. FTIR Spectroscopy

4.9.2. XRD Spectroscopy

4.9.3. SEM Analysis

4.9.4. DLS Particle Size Distribution Analysis

4.10. Antioxidant Activity

4.10.1. Sample Preparation

4.10.2. Determination of TPC

4.10.3. FRAP Assay

4.10.4. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

4.11. Antimicrobial Test

4.12. Cell Culture Procedure

4.12.1. Cell Culture and Treatment

4.12.2. MTT Assay

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bahadori, M.B.; Dinparast, L.; Zengin, G. The genus Heracleum: A comprehensive review on its phytochemistry, pharmacology, and ethnobotanical values as a useful herb. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 1018–1039. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33401836/. [CrossRef]

- Matarrese, E.; Renna, M. Prospects of hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium L.) as a new horticultural crop for food and non-food uses: A review. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, Z.; Ramazani, A.; Razzaghi-Asl, N. Plants of the genus Heracleum as a source of coumarin and furanocoumarin. J. Chem. Rev. 2019, 1, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săvulescu T (Ed). Flora R.P.R., 1st ed.; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1958; Volume VI, pp. 326–334, 621–633 (in Romanian).

- Tutin, T.G.; Heywood, V.H.; Burges, N.A.; Moore, D.M.; Valentine, D.H.; Walters, S.M.; Webb, D.A. (Eds). Flora Europaea. Vol. 2: Rosaceae to Umbelliferae, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1968, pp. 315–319, 364–366.

- Ciocârlan, V. Flora ilustrată a României. Pteridophyta et Spermatophyta, 3rd ed.; Ceres Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2009; pp. 461–466, 496–498 (in Romanian).

- Sârbu, I.; Ştefan, N.; Oprea, A. Plante vasculare din România. Determinator ilustrat de teren. 1st ed.; Victor B Victor Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2013; pp. 404–416, 444–446 (in Romanian).

- Benedec, D.; Hanganu, D.; Filip, L.; Oniga, I.; Tiperciuc, B.; Olah, N.K.; Gheldiu, A.M.; Raita, O.; Vlase, L. Chemical, antioxidant and antibacterial studies of Romanian Heracleum sphondylium. Farmacia 2017, 65, 252–256. Available online: https://farmaciajournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017-02-art-15-Benedec_Oniga_Vlase_252-256.pdf.

- İşcan, G.; Demirci, F.; Kürkçüoğlu, M.; Kıvanç, M.; Başer, K.H.C. The bioactive essential oil of Heracleum sphondylium L. subsp. ternatum (Velen.) Brummitt. Z. Naturforsch. C J. Biosci. 2003, 58, 195–200. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12710728/. [CrossRef]

- Uysal, A.; Ozer, O.Y.; Zengin, G.; Stefanucci, A.; Mollica, A.; Picot-Allain, C.M.N.; Mahomoodally, M.F. Multifunctional approaches to provide potential pharmacophores for the pharmacy shelf: Heracleum sphondylium L. subsp. ternatum (Velen.) Brummitt. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019, 78, 64–73. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30500554/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozek, T.; Demirci, B.; Baser, K.H.C. Comparative study of the essential oils of Heracleum sphondylium ssp. ternatum obtained by micro- and hydro-distillation methods. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2002, 38, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senejoux, F.; Demougeot, C.; Cuciureanu, M.; Miron, A.; Cuciureanu, R.; Berthelot, A.; Girard-Thernier, C. Vasorelaxant effects and mechanisms of action of Heracleum sphondylium L. (Apiaceae) in rat thoracic aorta. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 147, 536–539. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23541934/. [CrossRef]

- Ergene, A.; Guler, P.; Tan, S.; Mirici, S.; Hamzaoglu, E.; Duran, A. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of Heracleum sphondylium subsp. artvinense. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 5, 1087–1089. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/journal/AJB/article-full-text-pdf/4597B636392.

- Maggi, F.; Quassinti, L.; Bramucci, M.; Lupidi, G.; Petrelli, D.; Vitali, L.A.; Papa, F.; Vittori, S. Composition and biological activities of hogweed [Heracleum sphondylium L. subsp. ternatum (Velen.) Brummitt] essential oil and its main components octyl acetate and octyl butyrate. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1354–1363. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24697288/. [CrossRef]

- Ušjak, L.; Sofrenić, I.; Tešević, V.; Drobac, M.; Niketić, M.; Petrović, S. Fatty acids, sterols, and triterpenes of the fruits of 8 Heracleum taxa. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierascu, R.C.; Padure, I.M.; Avramescu, S.M.; Ungureanu, C.; Bunghez, R.I.; Ortan, A.; Dinu-Pirvu, C.; Fierascu, I.; Soare, L.C. Preliminary assessment of the antioxidant, antifungal and germination inhibitory potential of Heracleum sphondylium L. (Apiaceae). Farmacia 2016, 64, 403–408. Available online: https://farmaciajournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2016-03-art-13-Fierascu_403-408.pdf.

- Matejic, J.S.; Dzamic, A.M.; Mihajilov-Krstev, T.; Ristic, M.S.; Randelovic, V.N.; Krivošej, Z.Ð.; Marin, P.D. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of essential oil and extracts from Heracleum sphondylium L. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2016, 19, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wen, K.-S.; Ruan, X.; Zhao, Y.-X.; Wei, F.; Wang, Q. Response of plant secondary metabolites to environmental factors. Molecules 2018, 23, 762. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29584636/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segneanu, A.E.; Grozescu, I.; Sfirloaga, P. The influence of extraction process parameters of some biomaterials precursors from Helianthus annuus. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2013, 8, 1423–1433. Available online: https://chalcogen.ro/1423_Segneanu.pdf.

- Popescu, C.; Fitigau, F.; Segneanu, A.E.; Balcu, I.; Martagiu, R.; Vaszilcsin, C.G. Separation and characterization of anthocyanins by analytical and electrochemical methods. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2011, 10, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaszilcsin, C.G.; Segneanu, A.E.; Balcu, I.; Pop, R.; Fitigău, F.; Mirica, M.C. Eco-friendly extraction and separation methods of capsaicines. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2010, 9, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segneanu, A.E.; Damian, D.; Hulka, I.; Grozescu, I.; Salifoglou, A. A simple and rapid method for calixarene-based selective extraction of bioactive molecules from natural products. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 849–858. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26597796/. [CrossRef]

- Emran, T.B.; Shahriar, A.; Mahmud, A.R.; Rahman, T.; Abir, M.H.; Siddiquee, M.F.R.; Ahmed, H.; Rahman, N.; Nainu, F.; Wahyudin, E.; et al. Multidrug resistance in cancer: Understanding molecular mechanisms, immunoprevention and therapeutic approaches. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 891652. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35814435. [CrossRef]

- Nath, R.; Roy, R.; Barai, G.; Bairagi, S.; Manna, S.; Chakraborty, R. Modern developments of nano based drug delivery system by combined with phytochemicals – presenting new aspects. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2021, 8, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Blanco, J.; Vishwakarma, N.; Lehr, C.M.; Prestidge, C.A.; Thomas, N.; Roberts, R.J.; Thorn, C.R.; Melero, A. Antibiotic resistance and tolerance: What can drug delivery do against this global threat? Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024, 14, 1725–1734. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38341386/. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Hussein, S.; Qurbani, K.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Fareeq, A.; Mahmood, K.A.; Mohamed, M.G. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. J. Med. Surg. Publ. Health 2024, 2, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; Fraceto, L.F.; Campos, E.V.R.; del Pilar Rodriguez-Torres, M.; Acosta-Torres, L.S.; Diaz-Torres, L.A.; Grillo, R.; Swamy, M.K.; Sharma, S.; et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: Recent developments and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chauhan, A.; Ranjan, A.; Mathkor, D.M.; Haque, S.; Ramniwas, S.; Tuli, H.S.; Jindal, T.; Yadav, V. Emerging challenges in antimicrobial resistance: Implications for pathogenic microorganisms, novel antibiotics, and their impact on sustainability. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1403168. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38741745/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewi, M.K.; Chaerunisaa, A.Y.; Muhaimin, M.; Joni, I.M. Improved activity of herbal medicines through nanotechnology. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4073. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36432358/. [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Khan, J.M.; Alhomida, A.S.; Ola, M.S.; Alshehri, M.A.; Ahmad, A. Metal nanoparticles: Biomedical applications and their molecular mechanisms of toxicity. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 6073–6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meher, A.; Tandi, A.; Moharana, S.; Chakroborty, S.; Mohapatra, S.S.; Mondal, A.; Dey, S.; Chandra, P. Silver nanoparticle for biomedical applications: A review. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 6, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segneanu, A.-E.; Vlase, G.; Lukinich-Gruia, A.T.; Herea, D.-D.; Grozescu, I. Untargeted metabolomic approach of Curcuma longa to neurodegenerative phytocarrier system based on silver nanoparticles. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11, 2261. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36421447/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Činčala, Ľ.; Illeová, V.; Antošová, M.; Štefuca, V.; Polakovič, M. Investigation of plant sources of hydroperoxide lyase for 2(E)-hexenal production. Acta Chim. Slovaca 2015, 8, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, I.L.J.; Mišan, A.Č.; Sakač, M.B.; Čabarkapa, I.S.; Šarić, B.M.; Matić, J.J.; Jovanov, P.T. Evaluation of a GC-MS method for the analysis of oregano essential oil composition. Food Feed Res. 2009, 36, 75–79. Available online: http://foodandfeed.fins.uns.ac.rs/uploads/Magazines/magazine_49/evaluation-of-a-gc-ms-method-for-the-analysis-of-oregano-essential-oil-composition.pdf.

- Chen, Q.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, P.; Yang, Y.; Ni, Y. Preparative isolation and purification of cuminaldehyde and p-menta-1,4-dien-7-al from the essential oil of Cuminum cyminum L. by high-speed counter-current chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2011, 689, 149–154. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21338771/. [CrossRef]

- Segneanu, A.-E.; Vlase, G.; Vlase, T.; Ciocalteu, M.-V.; Bejenaru, C.; Buema, G.; Bejenaru, L.E.; Boia, E.R.; Dumitru, A.; Boia, S. Romanian wild-growing Chelidonium majus—An emerging approach to a potential antimicrobial engineering carrier system based on AuNPs: In vitro investigation and evaluation. Plants (Basel) 2024, 13, 734. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38475580/. [CrossRef]

- Mickus, R.; Jančiukė, G.; Raškevičius, V.; Mikalayeva, V.; Matulytė, I.; Marksa, M.; Maciūnas, K.; Bernatonienė, J.; Skeberdis, V.A. The effect of nutmeg essential oil constituents on Novikoff hepatoma cell viability and communication through Cx43 gap junctions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 135, 111229. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33444950/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminkhah, M.; Asgarpanah, J. GC-MS analysis of the essential oil from Artemisia aucheri Boiss. fruits. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2017, 62, 3581–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijit, N.; Prasitwattanaseree, S.; Mahatheeranont, S.; Wolschann, P.; Jiranusornkul, S.; Nimmanpipug, P. Estimation of retention time in GC/MS of volatile metabolites in fragrant rice using principle components of molecular descriptors. Anal. Sci. 2017, 33, 1211–1217. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29129857/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangchuk, P.; Keller, P.A.; Pyne, S.G.; Taweechotipatr, M.; Kamchonwongpaisan, S. GC/GC-MS analysis, isolation and identification of bioactive essential oil components from the Bhutanese medicinal plant, Pleurospermum amabile. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 1305–1308. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24273872/. [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubaye, A.F.; Kadhim, M.J.; Hameed, I.H. Determination of bioactive chemical composition of methanolic leaves extract of Sinapis arvensis using GC-MS technique. Int. J. Toxicol. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 9, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumari, P.; Somasundaram, S.T. Gas chromatography-mass spectrum (GC-MS) analysis of bioactive components of the methanol extract of halophyte, Sesuvium portulacastrum L. Int. J. Adv. Pharm. Biol. Chem. 2014, 3, 766–772. Available online: https://www.ijapbc.com/files/07-10-2015/39-3396RR.pdf.

- Viet, T.D.; Xuan, T.D.; Anh, L.H. α-Amyrin and β-amyrin isolated from Celastrus hindsii leaves and their antioxidant, anti-xanthine oxidase, and anti-tyrosinase potentials. Molecules 2021, 26, 7248. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34885832/. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Careri, M.; Mangia, A.; Musci, M. Retention indices in the analysis of food aroma volatile compounds in temperature-programmed gas chromatography: Database creation and evaluation of precision and robustness. J. Sep. Sci. 2007, 30, 563–572. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17444225/. [CrossRef]

- Segneanu, A.-E.; Cepan, M.; Bobica, A.; Stanusoiu, I.; Dragomir, I.C.; Parau, A.; Grozescu, I. Chemical screening of metabolites profile from Romanian Tuber spp. Plants (Basel) 2021, 10, 540. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33809254/. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Calderon, O.; Chavez, H.; Enciso-Roca, E.C.; Común-Ventura, P.W.; Hañari-Quispe, R.D.; Figueroa-Salvador, L.; Loyola-Gonzales, E.L.; Pari-Olarte, J.B.; Aljarba, N.H.; Alkahtani, S.; et al. GC-MS profile, antioxidant activity, and in silico study of the essential oil from Schinus molle L. leaves in the presence of mosquito juvenile hormone-binding protein (mJHBP) from Aedes aegypti. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5601531. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35615009/. [CrossRef]

- Słowiński, K.; Grygierzec, B.; Synowiec, A.; Tabor, S.; Araniti, F. Preliminary study of control and biochemical characteristics of giant hogweed (Heracleum sosnowskyi Manden.) treated with microwaves. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicchi, C.; D’Amato, A.; Frattini, C.; Cappelletti, E.M.; Caniato, R.; Filippini, R. Chemical diversity of the contents from the secretory structures of Heracleum sphondylium subsp. sphondylium. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 1883–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, Z.; Sadati Lamardi, S.N. Phytochemistry and biological activities of Heracleum persicum: A review. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 16, 223–235. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29866612/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazrati, S.; Mollaei, S.; Rabbi Angourani, H.; Hosseini, S.J.; Sedaghat, M.; Nicola, S. How do essential oil composition and phenolic acid profile of Heracleum persicum fluctuate at different phenological stages? Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 6192–6206. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33282270/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Zhong, A.; Shen, P.; Zhu, J.; Li, L.; Xia, G.; Zang, H. Chemical constituents, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oil from the flowering aerial parts of Heracleum moellendorffii Hance. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2325198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segneanu, A.-E.; Vlase, G.; Vlase, T.; Bita, A.; Bejenaru, C.; Buema, G.; Bejenaru, L.E.; Dumitru, A.; Boia, E.R. An innovative approach to a potential neuroprotective Sideritis scardica–clinoptilolite phyto-nanocarrier: In vitro investigation and evaluation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1712. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38338989/. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.A.; Mustafa, Y.F.; Ibrahim, B.Y. Isolation and characterization of furanocoumarins from golden delicious apple seeds. J. Med. Chem. Sci. 2022, 5, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Hu, J.; Dang, Y.; Deng, H.; Ren, J.; Cheng, S.; Tan, M.; Zhang, H.; He, X.; Yu, H.; et al. Sphondin efficiently blocks HBsAg production and cccDNA transcription through promoting HBx degradation. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28578. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36846971/. [CrossRef]

- Krysa, M.; Szymańska-Chargot, M.; Zdunek, A. FT–IR and FT–Raman fingerprints of flavonoids – A review. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133430. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35696953/. [CrossRef]

- Bensemmane, N.; Bouzidi, N.; Daghbouche, Y.; Garrigues, S.; de la Guardia, M.; El Hattab, M. Quantification of phenolic acids by partial least squares Fourier-transform infrared (PLS–FTIR) in extracts of medicinal plants. Phytochem. Anal. 2021, 32, 206–221. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32666562/. [CrossRef]

- Zając, A.; Michalski, J.; Ptak, M.; Dymińska, L.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Zierkiewicz, W.; Hanuza, J. Physicochemical characterization of the loganic acid – IR, Raman, UV–Vis and luminescence spectra analyzed in terms of quantum chemical DFT approach. Molecules 2021, 26, 7027. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34834118/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, A.; Idris, M.M.; Ali, U.; Umar, A.; Sirat, H.M. Characterization and tyrosinase activities of a mixture of β-sitosterol and stigmasterol from Bauhinia rufescens Lam. Acta Pharm. Indones. 2023, 11, 6284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.K.; Yadav, B.; Srivastav, G.; Jha, O.; Yadav, R.A. Conformational, structural and vibrational studies of estragole. Vib. Spectrosc. 2021, 117, 103317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.S.S.; Estrella-Pajulas, L.L.; Alemaida, I.M.; Grilli, M.L.; Mikhaylov, A.; Senjyu, T. Green synthesis of silver oxide nanoparticles for photocatalytic environmental remediation and biomedical applications. Metals 2022, 12, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatage, S.T.; Hebalkar, A.S.; Dhobale, S.V.; Mali, O.R.; Kumbhar, P.S.; Nikade, S.V.; Killedar, S.G. Silver nanoparticles: Properties, synthesis, characterization, applications and future trends. In Silver Micro-Nanoparticles—Properties, Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications; Kumar, S., Kumar, P., Pathak, C.S., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; Chapter 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaja, M.; Annadurai, G. Coleus aromaticus leaf extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its bactericidal activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2013, 3, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekhar Reddy, G.; Bertie Morais, A.; Nagendra Gandhi, N. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl free radical scavenging assay and bacterial toxicity of protein capped silver nanoparticles for antioxidant and antibacterial applications. Asian J. Chem. 2013, 25, 9249–9254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segneanu, A.-E.; Vlase, G.; Vlase, T.; Sicoe, C.A.; Ciocalteu, M.V.; Herea, D.D.; Ghirlea, O.-F.; Grozescu, I.; Nanescu, V. Wild-grown Romanian Helleborus purpurascens approach to novel chitosan phyto-nanocarriers—metabolite profile and antioxidant properties. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12, 3479. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37836219/. [CrossRef]

- Dash, D.K.; Tyagi, C.K.; Sahu, A.K.; Tripathi, V. Revisiting the medicinal value of terpenes and terpenoids. In Revisiting Plant Biostimulants; Meena, V.S., Parewa, H.P., Meena, S.K., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendra, C.K.; Tan, L.T.H.; Lee, W.L.; Yap, W.H.; Pusparajah, P.; Low, L.E.; Tang, S.Y.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H.; Goh, B.H. Angelicin – A furocoumarin compound with vast biological potential. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 366. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32372949/. [CrossRef]

- Liga, S.; Paul, C.; Péter, F. Flavonoids: Overview of biosynthesis, biological activity, and current extraction techniques. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12, 2732. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37514347/. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, P.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, Y. A brief review of phenolic compounds identified from plants: Their extraction, analysis, and biological activity. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2022, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobiuc, A.; Pavăl, N.-E.; Mangalagiu, I.I.; Gheorghiţă, R.; Teliban, G.-C.; Amăriucăi-Mantu, D.; Stoleru, V. Future antimicrobials: Natural and functionalized phenolics. Molecules 2023, 28, 1114. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36770780/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Dai, X.; Xu, H.; Tang, Q.; Bi, F. Regulation of ferroptosis by amino acid metabolism in cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 1695–1705. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35280684/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holeček, M. Aspartic acid in health and disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4023. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37764806/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coniglio, S.; Shumskaya, M.; Vassiliou, E. Unsaturated fatty acids and their immunomodulatory properties. Biology 2023, 12, 279. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36829556/. [CrossRef]

- Vezza, T.; Canet, F.; de Marañón, A.M.; Bañuls, C.; Rocha, M.; Víctor, V.M. Phytosterols: Nutritional health players in the management of obesity and its related disorders. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 1266. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33322742/. [CrossRef]

- Mahendra, M.Y.; Purba, R.A., Dadi, T.B., Pertiwi, H. Estragole: A review of its pharmacology, effect on animal health and performance, toxicology, and market regulatory issues. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 2023, 37, 537–546. [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, O.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Kobus-Cisowska, J. Hypoglycaemic, antioxidative and phytochemical evaluation of Cornus mas varieties. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambwani, S.; Tandon, R.; Ambwani, T.K. Metal nanodelivery systems for improved efficacy of herbal drugs. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 2019, 16, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedlovičová, Z.; Strapáč, I.; Baláž, M.; Salayová, A. A brief overview on antioxidant activity determination of silver nanoparticles. Molecules 2020, 25, 3191. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32668682/. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.; Ali, W.; Ali, M.; Khan, N.Z.; Aasim, M.; Khan, A.A.; Khan, T.; Ali, M.; Ali, A.; Ayaz, M.; et al. Delpinium uncinatum mediated green synthesis of AgNPs and its antioxidant, enzyme inhibitory, cytotoxic and antimicrobial potentials. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0280553. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37014921/. [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Filimban, F.Z.; Ambrin; Quddoos, A.; Sher, A.A.; Naseer, M. Phytochemical screening, HPLC analysis, antimicrobial and antioxidant effect of Euphorbia parviflora L. (Euphorbiaceae Juss.). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5627. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38454096. [CrossRef]

- Seneme, E.F.; dos Santos, D.C.; Silva, E.M.R.; Franco, Y.E.M.; Longato, G.B. Pharmacological and therapeutic potential of myristicin: A literature review. Molecules 2021, 26, 5914. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34641457/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, I.; Fujita, K.; Nihei, K. Antimicrobial activity of anethole and related compounds from aniseed. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahizan, N.A.; Yang, S.-K.; Moo, C.-L.; Song, A.A.-L.; Chong, C.-M.; Chong, C.-W.; Abushelaibi, A.; Lim, S.-H.E.; Lai, K.-S. Terpene derivatives as a potential agent against antimicrobial resistance (AMR) pathogens. Molecules 2019, 24, 2631. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31330955/. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, S.; Wang, Z.; Yu, X. Advances in pharmacological activities of terpenoids. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasihun, Y.; Alekaw Habteweld, H.; Dires Ayenew, K. Antibacterial activity and phytochemical components of leaf extract of Calpurnia aurea. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9767. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37328478/. [CrossRef]

- Nga, N.T.H.; Ngoc, T.T.B.; Trinh, N.T.M.; Thuoc, T.L.; Thao, D.T.P. Optimization and application of MTT assay in determining density of suspension cells. Anal. Biochem. 2020, 610, 113937. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32896515/. [CrossRef]

- Aslantürk, Ö.S. In vitro cytotoxicity and cell viability assays: Principles, advantages, and disadvantages. In Genotoxicity—A Predictable Risk to Our Actual World; Larramendy, M.L., Soloneski, S., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirait, M.; Sinulingga, K.; Siregar, N.; Doloksaribu, M.E.; Amelia. Characterization of hydroxyapatite by cytotoxicity test and bending test. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2193, 012039. [CrossRef]

- Miura, N.; Shinohara, Y. Cytotoxic effect and apoptosis induction by silver nanoparticles in HeLa cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 390, 733–737. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19836347/. [CrossRef]

- Kavaz, D.; Faraj, R.E. Investigation of composition, antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic characteristics from Juniperus sabina and Ferula communis extracts. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7193. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37137993/. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.L.; Lim, L.Y.; Hammer, K.; Hettiarachchi, D.; Locher, C. A review of commonly used methodologies for assessing the antibacterial activity of honey and honey products. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 975. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35884229/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.M. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 48 (Suppl 1), 5–16. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11420333/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, S.; Sengupta, D.; Deb, M.; Shilpi, A.; Parbin, S.; Rath, S.K.; Pradhan, N.; Rakshit, M.; Patra, S.K. Expression profiling of DNA methylation-mediated epigenetic gene-silencing factors in breast cancer. Clin. Epigenetics 2014, 6, 20. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25478034. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | RT [min] | RI determined | Area [%] | Compound name | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.13 | 821 | 1.18 | 2-hexenal | [33] |

| 2 | 5.73 | 1021 | 0.86 | p-cymene | [34] |

| 3 | 6.39 | 938 | 1.52 | α-pinene | [34] |

| 4 | 9.65 | 1228 | 0.67 | cuminaldehyde | [35] |

| 5 | 7.87 | 1034 | 1.48 | limonene | [34,36] |

| 6 | 11.60 | 1488 | 4.43 | β-ionone | [34,36] |

| 7 | 12.46 | 988 | 3.36 | myristicin | [37] |

| 8 | 16.15 | 1090 | 0.61 | linalool | [34,36] |

| 9 | 17.14 | 1212 | 1.56 | myrtenal | [38] |

| 10 | 18.32 | 1843 | 4.51 | anethole | [34] |

| 11 | 19.42 | 1165 | 0.79 | decanal | [39] |

| 12 | 20. 09 | 1473 | 19.49 | α-curcumene | [34] |

| 13 | 21.43 | 1247 | 1.85 | carvone | [34,36] |

| 14 | 22.67 | 1663 | 3.42 | apiole | [40] |

| 15 | 23.39 | 3113 | 1.08 | campesterol | [41] |

| 16 | 25.66 | 4776 | 4.81 | n-hentriacontane | [42] |

| 17 | 27.19 | 1365 | 4.76 | vanillin | [39] |

| 18 | 28.81 | 3333 | 11.78 | β-amirin | [43] |

| 19 | 30.68 | 1587 | 3.12 | spathulenol | [34] |

| 20 | 32.38 | 1193 | 0.37 | octyl acetate | [44] |

| 21 | 36.65 | 3139 | 0.92 | stigmasterol | [45] |

| 22 | 37.17 | 3289 | 4.38 | β-sitosterol | [45] |

| 23 | 37.57 | 1293 | 2.29 | germacrene D | [34,46] |

| 24 | 49.57 | 1507 | 0.89 | cadinene | [46] |

| 25 | 55.89 | 1627 | 2.25 | cadinol | [46] |

| No. | Detected m/z | Theoretical m/z | Molecular formula | Tentative of identification |

Category | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 76.07 | 75.07 | C2H5NO2 | glycine | amino acids | [47] |

| 2 | 90.88 | 89.09 | C3H7NO2 | alanine | amino acids | [47] |

| 3 | 106.08 | 105.09 | C3H7NO3 | serine | amino acids | [47] |

| 4 | 121.13 | 119.12 | C4H9NO3 | threonine | amino acids | [47] |

| 5 | 134.11 | 133.10 | C4H7NO4 | aspartic acid | amino acids | [47] |

| 6 | 148.12 | 147.13 | C5H9NO4 | glutamic acid | amino acids | [47] |

| 7 | 187.15 | 186.16 | C11H6O3 | angelicin | coumarins | [1] |

| 8 | 193.17 | 192.17 | C10H8O4 | scopoletin | coumarins | [1] |

| 9 | 203.17 | 202.16 | C11H6O4 | xanthotoxol | coumarins | [16] |

| 10 | 217.21 | 216.19 | C12H8O4 | sphondin | coumarins | [16] |

| 11 | 247.22 | 246.21 | C13H10O5 | isopimpinellin | coumarins | [2] |

| 12 | 271.29 | 270.28 | C16H14O4 | imperatorin | coumarins | [1,48] |

| 13 | 287.27 | 286.28 | C16H14O5 | heraclenin | coumarins | [1,2,48] |

| 14 | 305.28 | 304.29 | C16H16O6 | heraclenol | coumarins | [1,2,48] |

| 15 | 317.31 | 316.30 | C17H16O6 | byakangelicol | coumarins | [48] |

| 16 | 173.25 | 172.26 | C10H20O2 | capric acid | fatty acids | [1] |

| 17 | 201.33 | 200.32 | C12H24O2 | lauric acid | fatty acids | [1] |

| 18 | 229.37 | 228.37 | C14H28O2 | myristic acid | fatty acids | [15] |

| 19 | 255.42 | 254.41 | C16H30O2 | palmitoleic acid | fatty acids | [15] |

| 20 | 257.43 | 256.42 | C16H32O2 | palmitic acid | fatty acids | [1] |

| 21 | 271.49 | 270.50 | C17H34O2 | margaric acid | fatty acids | [15] |

| 22 | 281.39 | 280.40 | C18H32O2 | linoleic acid | fatty acids | [1,16] |

| 23 | 283.51 | 282.50 | C18H34O2 | oleic acid | fatty acids | [1] |

| 24 | 284.49 | 284.50 | C18H36O2 | stearic acid | fatty acids | [1] |

| 25 | 313.49 | 312.50 | C20H40O2 | arachidic acid | fatty acids | [15] |

| 26 | 341.59 | 340.60 | C22H44O2 | behenic acid | fatty acids | [15] |

| 27 | 271.25 | 270.24 | C15H10O5 | apigenin | flavonoids | [8,10] |

| 28 | 287.23 | 286.24 | C15H10O6 | kaempferol | flavonoids | [8,10] |

| 29 | 291.28 | 290.27 | C15H14O6 | catechin | flavonoids | [10] |

| 30 | 303.24 | 302.23 | C15H10O7 | quercetin | flavonoids | [8,10] |

| 31 | 449.41 | 448.40 | C21H20O11 | astragalin | flavonoids | [1] |

| 32 | 465.39 | 464.40 | C21H20O12 | hyperoside | flavonoids | [1] |

| 33 | 611.49 | 610.50 | C27H30O16 | rutin | flavonoids | [8] |

| 34 | 377.35 | 376.36 | C16H24O10 | loganic acid | iridoids | [1] |

| 35 | 139.11 | 138.12 | C7H6O3 | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | phenolic acids | [10] |

| 36 | 155.13 | 154.12 | C7H6O4 | gentisic acid | phenolic acids | [8] |

| 37 | 165.15 | 164.16 | C9H8O3 | p-coumaric acid | phenolic acids | [8,10] |

| 38 | 171.11 | 170.12 | C7H6O5 | gallic acid | phenolic acids | [10] |

| 39 | 181.17 | 180.16 | C9H8O4 | caffeic acid | phenolic acids | [8,10] |

| 40 | 195.18 | 194.18 | C10H10O4 | ferulic acid | phenolic acids | [8,10] |

| 41 | 355.32 | 354.31 | C16H18O9 | chlorogenic acid | phenolic acids | [8] |

| 42 | 149.19 | 148.20 | C10H12O | estragole | phenylpropanoids | [49] |

| 43 | 401.71 | 400.70 | C28H48O | campesterol | sterols | [15] |

| 44 | 413.69 | 412.70 | C29H48O | stigmasterol | sterols | [15] |

| 45 | 415.71 | 414.70 | C29H50O | β-sitosterol | sterols | [1,15] |

| 46 | 135.23 | 134.22 | C10H14 | p-cymene | terpenoids | [14,17] |

| 47 | 137.24 | 136.23 | C10H16 | α-pinene | terpenoids | [14,17] |

| 48 | 151.23 | 150.22 | C10H14O | carvone | terpenoids | [49] |

| 49 | 153.22 | 152.23 | C10H16O | phellandral | terpenoids | [49] |

| 50 | 155.25 | 154.25 | C10H18O | linalool | terpenoids | [49] |

| 51 | 156.25 | 156.26 | C10H20O | menthol | terpenoids | [49] |

| 52 | 193.31 | 192.30 | C13H20O | β-ionone | terpenoids | [49] |

| 53 | 203.34 | 202.33 | C15H22 | α-curcumene | terpenoids | [17,50] |

| 54 | 205.36 | 204.35 | C15H24 | germacrene D | terpenoids | [14,17] |

| 55 | 207.36 | 206.37 | C15H26 | cadinene | terpenoids | [51] |

| 56 | 221.34 | 220.35 | C15H24O | spathulenol | terpenoids | [50] |

| 57 | 223.38 | 222.37 | C15H26O | cadinol | terpenoids | [51] |

| 58 | 251.34 | 250.33 | C15H22O3 | xanthoxin | terpenoids | [48] |

| 59 | 273.51 | 272.50 | C20H32 | β-springene | terpenoids | [50] |

| 60 | 427.69 | 426.70 | C30H50O | β-amirin | terpenoids | [48] |

| 61 | 149.21 | 148.20 | C10H12O | anethole | miscellaneous | [1] |

| 62 | 151.23 | 150.22 | C10H14O | myrtenal | miscellaneous | [17] |

| 63 | 153.16 | 152.15 | C8H8O3 | vanillin | miscellaneous | [10] |

| 64 | 193.22 | 192.21 | C11H12O3 | myristicin | miscellaneous | [14] |

| 65 | 223.25 | 222.24 | C12H14O4 | apiole | miscellaneous | [2] |

| 66 | 255.23 | 254.24 | C15H10O4 | chrysophanol | miscellaneous | [1] |

| 67 | 131.22 | 130.23 | C8H18O | n-octanol | alcohols | [14] |

| 68 | 117.19 | 116.20 | C7H16O | heptanol | alcohols | [49] |

| 69 | 75.13 | 74.12 | C4H10O | butanol | alcohols | [49] |

| 70 | 103.18 | 102.17 | C6H14O | hexanol | alcohols | [49] |

| 71 | 99.15 | 98.14 | C6H10O | hexanal | aldehydes | [14,17] |

| 72 | 129.22 | 128.21 | C8H16O | octanal | aldehydes | [17] |

| 73 | 157.25 | 156.26 | C10H20O | decanal | aldehydes | [17] |

| 74 | 145.22 | 144.21 | C8H16O2 | isobutyl isobutyrate |

esters | [17] |

| 75 | 163.19 | 162.18 | C10H10O2 | methyl cinnamate | esters | [1] |

| 76 | 173.27 | 172.26 | C10H20O2 | octyl acetate | esters | [14] |

| 77 | 187.28 | 186.29 | C11H22O2 | hexyl 2-methyl butanoate |

esters | [17] |

| 78 | 199.31 | 198.30 | C12H22O2 | dihydrolinalyl acetate |

esters | [17] |

| 79 | 197.28 | 196.29 | C12H20O2 | bornyl acetate | esters | [17] |

| 80 | 201.33 | 200.32 | C12H24O2 | octyl isobutyrate | esters | [14,17] |

| 81 | 229.36 | 228.37 | C14H28O2 | octyl hexanoate | esters | [14] |

| 82 | 219.37 | 218.38 | C16H26 | 5-phenyldecane | hydrocarbons | [46] |

| 83 | 261.49 | 260.50 | C19H32 | 4-phenyltridecane | hydrocarbons | [46] |

| 84 | 353.69 | 352.70 | C25H52 | pentacosane | hydrocarbons | [1] |

| 85 | 381.69 | 380.70 | C27H56 | heptacosane | hydrocarbons | [1] |

| 86 | 395.81 | 394.80 | C28H58 | octacosane | hydrocarbons | [1] |

| 87 | 423.79 | 422.80 | C30H62 | triacontane | hydrocarbons | [1] |

| 88 | 437.81 | 436.80 | C31H64 | n-hentriacontane | hydrocarbons | [1] |

| Volatile organic compound | Odor profile |

|---|---|

| p-cymene | woody |

| α-pinene | piney |

| carvone | minty |

| phellandral | pungent, terpenic |

| linalool | floral, woody |

| menthol | minty |

| β-ionone | woody |

| α-curcumene | herbal |

| germacrene D | woody |

| cadinene | woody |

| spathulenol | herbal, fruity |

| cadinol | herbal |

| xanthoxin | floral |

| anethole | minty |

| myrtenal | herbal |

| vanillin | vanilla |

| myristicin | spicy |

| apiole | herbal |

| hexanal | herbal |

| octyl acetate | fruity |

| octyl butyrate | fruity |

| octanal | citrus |

| decanal | citrus |

| isobutyl isobutyrate | sweet |

| methyl cinnamate | fruity |

| hexyl 2-methyl butanoate | sweet, fruity |

| bornyl acetate | piney |

| octyl hexanoate | fruity, herbal |

| Biomolecules category |

Wavenumber [cm−1] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| terpenoids | 2974, 2943, 2350, 1746, 1708, 1450, 1088, 882 | [52] |

| coumarins | 1730, 1630, 1608, 1589, 1565, 1510, 1265, 1140 | [53] |

| flavonoids | 4002–3124, 3402–3102, 1654, 1645, 1619, 1574, 1504, 1495, 1480, 1368, 1271, 1078, 768, 536 | [54,55] |

| phenolic acids | 3442, 1733, 1634, 1594, 1516, 1458, 1242, 1158, 881 | [52,56] |

| amino acids | 3400, 3332–3128, 2922, 2362, 2133, 1724–1755, 1689, 1677, 1643, 1649, 1644, 1632, 1628, 1608, 1498–1599 | [52] |

| fatty acids | 3606, 3009, 2962, 2932, 2848, 1700, 1349, 1249, 1091, 722 | [36] |

| iridoids | 1448, 1371, 1346, 1235, 1151 | [57] |

| phytosterols | 3431, 3028, 2938, 1641, 1463, 1060 | [57,58] |

| phenylpropanoids | 3188, 3002, 1636, 1504, 1449, 1248 | [59] |

| Sample | TPC [mg GAE/g] | FRAP [mM Fe2+] | DPPH IC50 [mg/mL] |

|---|---|---|---|

| H. sphondylium | 8.14±0.18 | 29.31±0.11 | 7.65±0.05 |

| HS-Ag system | 11.47±0.16 | 32.44±0.08 | 5.62±0.07 |

| Pathogenic microorganism |

Sample | Inhibition zone diameter [mm] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample concentration [μg/mL] |

Positive control (Gentamicin 100 μg/mL) |

Negative control (DMSO) | ||||||

| 100 | 125 | 150 | 175 | 200 | ||||

|

Staphylococcus aureus |

H. sphondylium | 11.23±0.75 | 13.98±1.17 | 17.06±0.68 | 21.19±0.72 | 25.46±0.45 | 9.57±0.35 | 0 |

| HS-Ag system | 14.78±0.54 | 17.27±0.78 | 21.62±0.47 | 28.52±0.56 | 34.14±0.56 | |||

| Bacillus subtilis | H. sphondylium | 19.83±0.09 | 21.47±0.43 | 24.36±0.32 | 27.69±0.38 | 31.22±0.31 | 17.89±0.28 | 0 |

| HS-Ag system | 23.11±0.41 | 25.38±0.36 | 29.51±0.16 | 32.76±0.47 | 36.25±0.28 | |||

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

H. sphondylium | 10.64±0.27 | 14.09±0.21 | 16.73±0.25 | 18.95±0.82 | 20.38±0.17 | 18.67±0.19 | 0 |

| HS-Ag system | 21.78±0.19 | 23.01±0.17 | 24.74±0.32 | 26.18±0.61 | 27.65±0.19 | |||

| Escherichia coli | H. sphondylium | 11.84±0.37 | 14.69±0.34 | 17.15±0.51 | 19.03±0.43 | 21.49±0.34 | 20.69±0.31 | 0 |

| HS-Ag system | 20.88±0.28 | 21.63±0.25 | 23.06±0.42 | 25.02±0.47 | 27.12±0.58 | |||

| Pathogenic microorganism | Sample | MIC [μg/mL] | MBC [μg/mL] | Gentamicin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC [μg/mL] | MBC [μg/mL] | ||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | H. sphondylium | 0.22±0.07 | 0.23±0.19 | 0.62±0.22 | 0.62±0.21 |

| HS-Ag system | 0.12±0.03 | 0.11±0.16 | |||

| Bacillus subtilis | H. sphondylium | 0.28±0.19 | 0.24±0.12 | 0.49±0.18 | 0.43±0.19 |

| HS-Ag system | 0.16±0.08 | 0.15±0.23 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | H. sphondylium | 0.98±0.11 | 0.99±0.14 | 1.27±0.16 | 1.26±0.19 |

| HS-Ag system | 0.52±0.07 | 0.59±0.37 | |||

| Escherichia coli | H. sphondylium | 0.38±0.09 | 0.31±0.21 | 0.82±0.19 | 0.82±0.17 |

| HS-Ag system | 0.26±0.13 | 0.26±0.15 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).