Clinical Implications:

Service providers or relevant government departments could develop and maintain an online information hub, providing information, availability, and options for support.

Health care practitioners should be supported to proactively explore the support needs of caregivers.

There is an acute need for more, and more accessible, support to be available to caregivers.

Service providers could further utilise the demonstrated benefits of lived experience in the support they offer.

Introduction

Eating disorder (ED) onset commonly begins in adolescence (American Psychiatric Association, 2022) and those presenting with symptoms are often under the care of a guardian, usually a parent. Due to increased mortality among individuals with EDs (Fichter & Quadflieg, 2016), difficulty accessing timely treatment (Ministry of Health, 2008), and the intensive nature of treatment, parents (and sometimes other family members) often adopt a caregiver role to support their loved one.

Adopting the caregiving role can significantly impact wellbeing with many experiencing caregiver burden (Fletcher, Trip, Lawson, Wilson, & Jordan, 2021; Robinson, Stoyel, & Robinson, 2020; Surgenor et al., 2022). Caregivers must frequently take time off work to support nutritional, behavioural, and psychological rehabilitation of the person with the ED (Hay, 2020). The cumulative effect of stressors can negatively impact the caregiver’s physical and psychological health, reducing their quality of life through a deterioration of mood, increased stress, and social isolation (Berglund, Lytsy, & Westerling, 2015; Calvó-Perxas et al., 2018; Donkin, Sinclair, Rowland, McDougall, & Landon, In preparation). Furthermore, caregiver life satisfaction decreases as barriers to formal support, services offered by trained healthcare providers (HCPs), are more frequently encountered (de Oliveira & Hlebec, 2016).

The amount of support caregivers receive directly influences their experience of caregiving. Support can be categorised as either direct or indirect. Direct support, such as psychotherapy, focuses on improving the caregiver's quality of life by directly addressing the caregiver’s needs (Hannah et al., 2022; Padierna et al., 2013). Indirect support focuses on improving the condition of the individual with the ED, thereby reducing the caregiver’s burden (Eating Disorder Association New Zealand, 2024; Eating Disorders Victoria, n.d.; The Eating Disorders Association of Ireland, 2024).

However, caregivers also encounter various obstacles when seeking support (Robinson et al., 2020; Surgenor et al., 2022). Financial costs, limited geographical availability of services, and lengthy waitlist times are barriers reducing accessibility to New Zealand (NZ) mental health services (Kulshrestha & Shahid, 2022). This lack of support availability and access to support impacts the burden experienced by caregivers as they take on these responsibilities.

To our knowledge, no NZ study has explored the availability or benefit of support to these caregivers. This research is particularly important to better understand how supports can be further developed and improved. Furthermore, this research is timely given the recent announcement of the refreshment of the NZ eating disorder strategy (Doocey, 2025), and the role of caregivers within this strategy. As such, we aim to document what supports are accessed by people caring for someone with an ED in NZ, and how these supports could be improved.

Method

An online anonymous survey containing both open and closed questions was used to gain insight into caregivers’ support needs and experiences. The use of a mixed methods approach was based on similar approaches documented in existing NZ ED literature (Clark et al., 2023; Fletcher et al., 2021; Surgenor et al., 2022). The survey was developed in conjunction with Eating Disorder Carer Support NZ stakeholders (EDCS; SR and KM). The survey length varied depending on the answers provided by participants. The base survey consisted of 129 closed questions and 14 open questions exploring the psychological impacts of caregiving, supports accessed, and unmet support needs. An analysis of the psychological impacts of caregiving is reported elsewhere (Donkin et al., In preparation).

Participants

Eligible participants were, or are, caregivers of an individual with a diagnosed or suspected ED, residing in NZ, over 18 years of age, proficient in English, and with access to an internet connection to complete the survey. We did not limit the study to a timeframe for caregiving, as many caregivers described ongoing caregiving duties even when their loved one was considered to be “in remission from ED” by healthcare professionals.

Recruitment

Ethical approval was received on the 26th of March 2024 from the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (24/50). Recruitment commenced on the 27th of March 2024 by disseminating a flyer via email to key ED providers identified through an internet search. Social media advertising was also undertaken by the researchers through their networks. The email and the social media advertising contained a hyperlink that directed participants to a Qualtrics-hosted Participant Information Sheet and then to the questionnaire. Participants confirmed consent by beginning the questionnaire. No compensation was provided for participating in this study.

Data Collected

Participants provided key demographic information about themselves, as well as the person they provided care for, including age, age of onset, gender, relationship with the caregiver, ED type, co-occurring mental health conditions, and treatments accessed or declined. Participants were asked about their role as a caregiver, including the recency of caregiving and whether the role was shared. Questions about caregiver support needs explored what support was received, how support was accessed, the caregiver’s experiences of that support, its benefits, and how it could be improved. When support was inaccessible, participants were asked what made the support inaccessible, why they wanted to access that support, and what would have improved accessibility. To reduce respondent burden, participants were not required to answer every question.

Data Analysis

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29. Participants who had completed less than 5% of the study (10 items) were excluded ensuring that, at minimum, demographic statistics were completed to provide an overview of caregivers in NZ. Based on kurtosis and skewness values, all variables were suitable for parametric statistics. Descriptive analyses were used to summarise demographics, the use, accessibility, and helpfulness of the supports.

Content Analysis

The qualitative data were analysed using content analysis (CA). CA is a systematic technique by which large quantities of text are compressed into categories to describe the underlying meaning of the phenomena studied (Zaidman-Zait, 2014). There are three phases to CA: preparation, organising, and reporting (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008).

For the preparation phase, a manifest CA approach was chosen. This focus on describing and summarising the sample’s voice enabled the researchers to analyse the participants’ responses qualitatively whilst capturing the frequencies of identified codes (Vaismoradi, Turunen, & Bondas, 2013). This process also enabled each caregiver’s views to be fully expressed whilst also capturing the proportion who held a particular view.

The organising phase was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, each participant’s responses (‘meaning units’) were selectively reduced into codes based on commonalities (Erlingsson & Brysiewicz, 2017). Frequencies for each code were calculated. Codes were then further synthesised into categories capturing higher-order themes. RS and LD collaboratively synthesised codes into categories to confirm coding frame accuracy. Code and category frequencies were counted (Nc) for reporting. As the number of caregivers responding to each question varied, Nr represented the total number of responses to each question, while nc and nr represented respective sample frequencies. The final phase involved interpreting the results with the research team. Categories and codes were used to formulate descriptions relevant to each research question (Vaismoradi et al., 2013).

Results

Demographics

A total of 273 caregivers began the survey. Of these, 153 were retained in the final sample due to meeting the minimum requirements for inclusion. Caregivers were predominantly female (94.12%, nr = 144), of European descent (97.39%, nr = 149), between 40 and 64 years old (84.97%, nr = 130), had a university qualification (81.04%, nr = 124), and were in a relationship at the time of caregiving (83.66%, nr = 128). Some caregivers did not disclose their relationship to the individual with the ED, but at least 73.20% (nr = 112) of the caregivers were a parent and 48.37% (nr = 74) of the respondents shared the caregiving role to some extent. Further demographics and caregiving role characteristics are provided in Appendices A and B.

Individuals with the ED were predominantly young (

M = 19.1 years,

SD = 6.1 years) and female with anorexia nervosa (89.06%,

nr = 114; see

Appendix C). Co-occurring mental health disorders were common, with 56.86% (

nr = 87) experiencing anxiety and 30.07% (

nr = 46) depression. Treatment was accessed predominantly through the public health service (see

Table 1).

Support Accessed by Caregivers

Caregivers more frequently accessed generalist supports than ED-specialised ones (see

Table 2). This result was reflected in the comments that highlighted the challenges faced by many caregivers in terms of being able to access supports with ED-specific training or knowledge. On average, caregivers accessed three generalist supports and two ED-specialised supports; both before being offered treatment, and throughout the recovery process. The range of support sought reflected their purpose with few, if any services, meeting all caregiver needs.

Caregivers frequently sought indirect support to access additional support for the person with the ED. Support was commonly sought while waiting for public health services to treat their loved one or for the loved one to become unwell enough to meet service admission criteria. Caregivers also noted being excluded from appointments or treatment planning once their loved one turned 18 years old.

“In the early years (ages 16 and 17) treatment was FBT based and so we were included with the counselling sessions. But as soon as my daughter became an "adult", i.e. overnight on her 18th birthday, we were excluded by the health practitioners and continue to be so. It is very very frustrating since I am at the coalface (so to speak) of dealing with the symptoms of the disease every single day, yet I feel unwelcome in any treatment assessment or planning.”

A lack of direct support for the caregiver, who was often seen as a treating team member, was apparent. Many caregivers indicated a desire for more support to enable them to better care for their loved one and their own wellbeing, particularly as caregivers delivered the bulk of many interventions at home. Caregivers would have received supervision and collegial support from the wider treating team if employed as a team member. Instead, the support caregivers received was often for the person with the ED, rather than for themselves:

“The support was always related to my daughter's treatment and I was related to as mum rather than as a person with distinct needs. It was helpful for education but not the emotional impact of what I went through as a caregiver.”

“I felt like I was doing it on my own really never told what to do at home. I only felt supported once she went into [Regional Service] as an Inpatient.”

Reasons for Accessing Supports

Caregivers primarily sought emotional or psychological support to manage their mental health and ED-specific knowledge to help facilitate ED recovery (see

Table 3). Those seeking ED-specific knowledge typically sought guidance on ED management, such as practical tools to support refeeding.

The benefits obtained by caregivers generally aligned with the support they sought (see

Table 3). Caregivers also benefited from seeking support from others caring for someone with an ED. Such support was frequently received through services such as EDCS and EDANZ. Caregivers felt peers could offer hope, guidance about what had worked for them, validation of the difficulties of caregiving and the emotional impact, and a reduction in the sense of isolation experienced. The sharing of lived experience was perceived as invaluable:

“All the support I got came through me seeking options and talking with a friend who also had a daughter with AN. None of the professionals we saw offered support or spoke about the toll being a caregiver would take.”

“Many parents have had lived experience of the ‘system’ which was nice to find others who had been there and knew how tough it is dealing with the situation your loved one was in.”

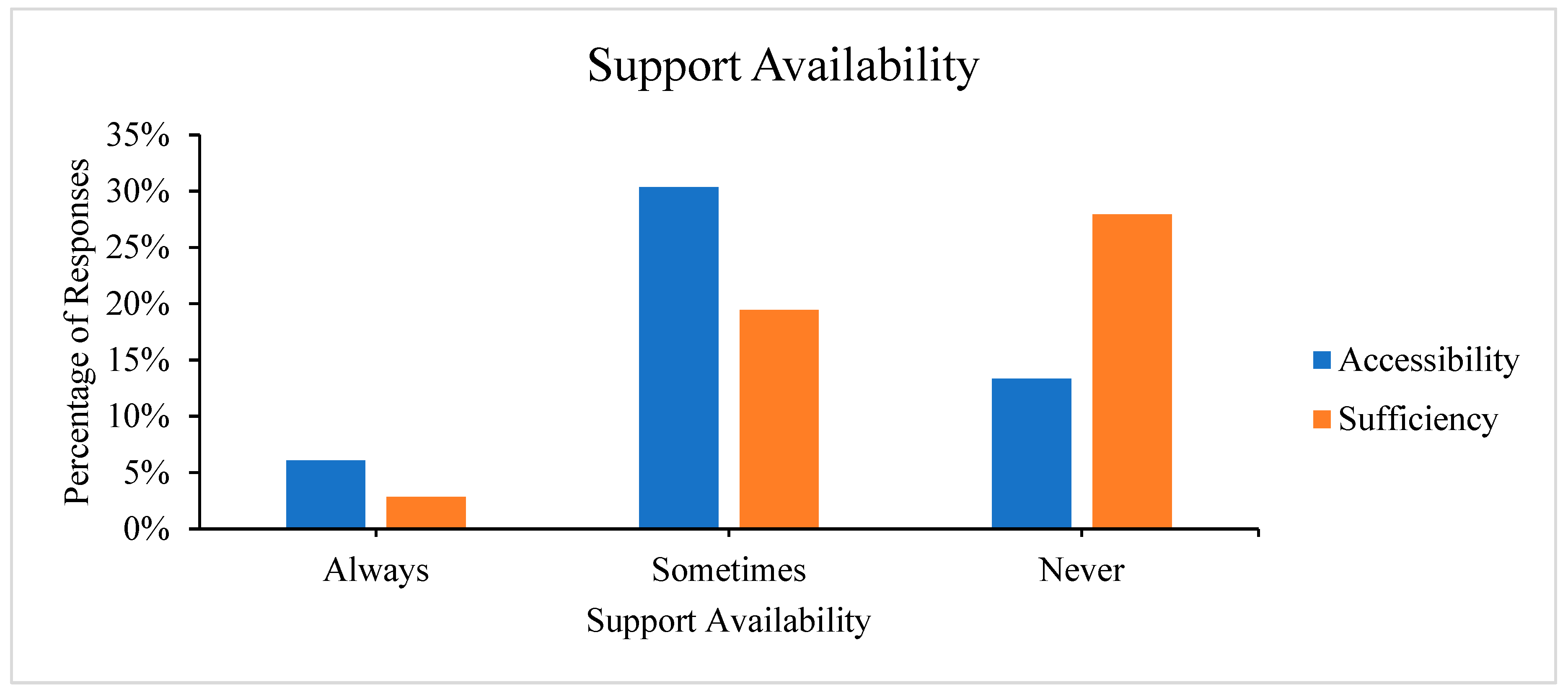

Accessibility and Sufficiency of Caregiver Support

Few caregivers described support as always accessible (i.e., able to be reached;

nc = 15) or sufficient (i.e., enough to meet the caregiver’s needs;

nc = 7;

Figure 1). Of the inaccessible supports mentioned (

nc = 57), caregivers were primarily unable to access ED-specialised support (35.09%;

nc = 20) and functional support (14.04%;

nc = 8), such as meal support (see

Appendix D). Other barriers encountered were financial (35.48%;

nc = 22), lack of support availability (35.48%;

nc = 22), and treatment ineligibility of the individual with the ED (9.68%;

nc = 6). These barriers are not easily navigated as the contributing factors are often outside the caregiver’s control.

“I have been told so many times that I need support and asked what support can we give you. But I don’t know what support there is. I haven't been provided with an assortment of options or services to select from, it's felt very much that's it's my job on top of everything else to go and arrange that for myself and find it.”

“Once discharged from hospital no one could ever give us a definitive plan for how to help our daughter - felt very much like we had to figure out what worked on our own.”

Difficulty accessing ED-specific knowledge was frequently highlighted as an issue. Even within speciality services, challenges were faced where the person living with the ED had other co-occurring difficulties such as self-harm, diabetes mellitus or autism spectrum disorder. Thus, the management of co-occurring disorders frequently required support from additional services or were not considered in the delivery of treatment, likely impacting their effectiveness.

“Never received any ED outpatient treatment as they would not take her due to Autism (high functioning). Has been under MHA multiple times in psychiatric wards for severe suicidality and self-harm, and has had 3 inpatient stays in a ED ward, however they have now discharged, said she is severe, and is no longer allowed back. She is dying in front of my eyes.”

“Treatment was declined for the eating disorder by the public system because she is also a diabetic but her self-harm made her too risky for any private clinic. The public system also won’t treat her because her weight is too high.”

Funding Support

Of the 108 responses from caregivers about accessing funding, 61.11% (nc = 66) noted not receiving any funding and 11.11% (nc = 12) reported funding as being caregiver-sourced. Caregivers sourced funding through private sponsorship, private insurance, church trusts, withdrawing superannuation funds, and fundraising:

“I raised money by shaving my head.”

“The ED has cost us our savings, home, career - but recovery is worth it.”

Where people were able to access public funding, the two main funding sources were the Child Disability Allowance (12.96%, nc = 14) and the Work and Income New Zealand Carer Support Subsidy (7.41%, nc = 8). Thus, only approximately 25.00% (nc = 27) of caregivers received government funding to enable them to care for their loved one with an ED.

Support Improvements

Caregivers were asked to recommend improvements for each support type. The answers (Nc = 319) reflected the challenges experienced and supports available in NZ. Predominantly, caregivers desired a centralised system containing information and resources that would support them during recovery (24.14%, nc = 77). Greater ED-related training for non-specialist healthcare professionals (18.18%, nc = 58) and increased availability of ED-specialised supports (15.36%, nc = 49) were also desired. Increasing funding availability (9.40%, nc = 30) and availability of direct support specifically for caregivers (8.60%, nc = 27) were also commonly mentioned.

Discussion

The Support Needs of Caregivers

This is the first study to explore the support needs of caregivers of those affected by an ED in NZ, and the findings largely reflect a lack of perceived support across public providers for the individuals with an ED and their caregivers. Issues regarding the accessibility and sufficiency of supports available were also evident across public and private services.

Caregivers identified a broad range of needs focused on emotional, informational, functional and financial support. The supports most frequently accessed by caregivers were support groups and self-help materials, likely due to their ease of access and low cost. Support groups provided peer support that helped caregivers feel understood and reduced their sense of isolation, offering the desired emotional and social support, and provided valued tips and strategies (Binford Hopf, Grange, Moessner, & Bauer, 2013; Fox, Dean, & Whittlesea, 2017; Grennan et al., 2022). However, the strong theme of lack of support, irrespective of accessing support groups, indicates that these groups cannot replace formal direct support but instead play a crucial supplementary role.

ED-specialised and functional supports were the most inaccessible support options. ED-specialised and functional supports are likely challenging to access due to the limited number of professionals trained to work with individuals affected by an ED (Ministry of Health, 2023). Furthermore, as ED specialists are often considered the best support for EDs, many seek their services, resulting in lengthy waitlists (Johns, Taylor, John, & Tan, 2019). This is exacerbated by the high turnover of staff across the NZ mental health sector resulting in the loss of skills and knowledge required to provide specialised and functional support (Te Hiringa Mahara- the New Zealand Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission, 2024).

Finances and lack of support availability were the main barriers to support. As caregivers focus their resources on ensuring the recovery of the individual with the ED, their ability to afford support for themselves is compromised. This financial strain is exacerbated by many caregivers having to reduce work hours. Financial support directly available to caregivers remains limited despite the New Zealand government investing approximately $15.5 million into regional ED services annually (New Zealand Government, 2022). Increasing accessibility to financial support would increase access formal support, such as mental health therapists, through which the range of support needs of caregivers could be addressed. This in turn may mitigate the impact burden of caregiving and improve ED outcomes (Te Hiringa Mahara, 2024).

The support afforded to the individual with the ED directly impacted caregiver burden. Several caregivers shared that their child fell through the cracks as their condition was too severe to receive private treatment, but not acute enough to receive public treatment. This situation is also common in the UK and Australia, with few private specialists taking on clients with acute needs due to their inability to provide 24/7 support with the associated management of medical risk (Robinson et al., 2020; Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, 2021). Furthermore, a systematic review noted that those with lower BMIs were prioritised for specialist care, hindering those with EDs not characterised by low BMI from receiving treatment (Johns et al., 2019). Delaying admissions raises the risk of morbidity and mortality, placing greater pressure on the caregivers to provide comprehensive support. This also drives up treatment costs due to the increased need for comprehensive support and additional staff time, reducing caregivers’ financial capacity to seek support for themselves.

Even though a lack of support was evident, caregivers described multiple benefits of support they accessed. Caregivers particularly valued receiving emotional and psychological support likely because it bolstered their mental health and facilitated the development of coping strategies. Gaining ED-specific knowledge was also a key benefit as it enabled caregivers to be more effective support providers, thereby reducing some distress (Haigh & Treasure, 2003). Psychoeducation around the causes, symptoms, and potential implications of the ED can also support caregivers in “separating” their loved one from the ED, reducing caregiver engagement in ED reinforcement (Kurnik Mesarič, Damjanac, Debeljak, & Kodrič, 2024; Uehara, Kawashima, Goto, Tasaki, & Someya, 2001). Caregivers also valued acquiring ED management skills, such as how to facilitate refeeding (Kurnik Mesarič et al., 2024). This is unsurprising as restoring eating behaviours and extinguishing ED behaviours are central to FBT (Monteleone et al., 2022).

Practical Recommendations

Develop and Maintain an Information Hub

Identifying available services can be challenging for caregivers. A website containing up-to-date details of reliable resources and recommended support services should be established such as those seen in Australia (Institute for Eating Disorders, 2024; n.d.). This central database for ED support would be searchable, enabling easier identification of available evidence-based resources, thereby increasing information and support accessibility and reducing the time required to find adequate supports.

Increase Support Availability for Caregivers

Established caregiver ED support organisations in NZ such as EDANZ or EDCS, already offer services such as virtual support groups and telephone helplines (Eating Disorder Association New Zealand, n.d.; Eating Disorders Carer Support, n.d.). These services fill gaps in the current support available and align with the government’s interest in establishing a peer support workforce (New Zealand Government, 2022). However, as these services are run by a small number of volunteers, to improve support availability and accessibility, we recommend funding peer support staff to cover peak service times. Likewise, better support for the peer workforce such as access to training and supervision would likely improve the longevity and wellbeing of this important workforce.

Increase Funding Availability for Caregivers

Neither the child disability allowance nor the carer support subsidy enabled caregivers to access formal support services other than relief care (Ministry of Social Development, n.d.; Te Whatu Ora, n.d.). However, finding time for respite can be difficult, particularly when undertaking FBT or maintaining feeding routines (Forsberg, Lock, & Grange, 2018). Therefore, we recommend amending the carer support subsidy purchasing rules so caregivers can use the funding for formal support services or ED-related support in a manner that works for them (Te Whatu Ora, 2023). This could increase accessibility to ED-specific information and emotional support for the caregiver, subsequently improving the emotional, psychological, informational, and financial support received.

HCPs Proactively Assess Support Needs

We are conscious of the pressure HCPs currently experience in NZ. Nonetheless, HCPs should be further supported to be more proactive in engaging with caregivers about their current wellbeing and support needs. This includes providing information about services available and checking in with caregivers regularly to assess changes in support needs and ensure they are receiving adequate support. Multiple prior studies noted a lack of ED-related information available from HCPs (Fletcher et al., 2021; Fox et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2020), suggesting that this need is unmet internationally. HCPs providing reliable and sufficient information could assist in reducing a caregiver’s burden of responsibility and psychological stress by meeting their need for ED-specific knowledge (Fletcher et al., 2021; Rhind et al., 2016).

Targeted ED-Specialised Support

We recommend implementing tools to support HCPs, such as the development/utilisation and dissemination of a reliable and valid ED triage questionnaire to streamline the assessment process. Utilising a reliable and validated ED triage questionnaire, alongside upskilling non-specialised HCPs, would enable better detection of EDs and assessment of needs (Machado, Grilo, Rodrigues, Vaz, & Crosby, 2020). In turn, the number of individuals with EDs requiring specialised care will likely reduce (Kalindjian et al., 2022). We recognise that increased screening may lead to increased detection in an already overburdened NZ health system (Ministry of Health, 2024). However, early detection would be advantageous, while inadequate triaging can result in a rapid decline in the health of those with acute needs due to insufficient or a lack of timely care.

Limitations

Of the 153 eligible participants, 38.56% (n = 59) did not complete the survey. These incomplete responses may be due to the survey’s length (up to 190 questions if participants endorsed all types of support). As participants experienced a significant caregiver burden, having to commit their time and energy to ill dependents, a high level of motivation was required to complete the survey (Fox et al., 2017). However, many participants did not complete the basic demographic information. Such participants may have been interested in learning about the survey but were less motivated to complete it. This indicates that it is likely various factors contributed to the high non-completion rate. It is unclear how this would impact the results.

The recruitment methods here (primarily through ED networks) increased the likelihood of participants being aware of or enrolled in a support service. Thus, our results are likely biased towards the views of caregivers already recognising the need for support. They may be less reflective of the views of caregivers new to the role without the same connections or those experiencing less caregiver burden and thus have not sought support. As such, broader recruitment methods, such as a prospective design, should be adopted in future research.

Future Research

The perceived availability and sufficiency of supports across ED types should be studied as the objective hardship experienced by caregivers can differ by ED type (Yates, Tennstedt, & Chang, 1999). We anticipate greater support will be available for individuals with EDs widely recognised within NZ, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. A lack of research on less-known EDs within NZ (Cleland et al., 2023), such as rumination disorder, may result in individuals with EDs encountering more treatment barriers, such as ineligibility for financial support.

Conclusion

This study found that treatment barriers and lack of support were the most common challenges reported by caregivers, likely contributing to the high usage of self-help materials, online support groups, and GPs. Our findings highlight the need for HCP training and funding to establish or augment caregiver support services to reduce the caregiver burden and the morbidity and mortality associated with ED.

Reflective Statement

RS is a counselling psychologist intern who has observed the impact of EDs on two of her friends and their caregivers. Previously, RS was a police officer for the NZ Police. As part of this role, she worked with multiple individuals experiencing mental distress.

JL is an academic psychologist who has undertaken research understanding the needs of caregivers and documenting the impacts associated with caregiving for family members experiencing various conditions.

SR is a dedicated advocate and ambassador for eating disorders and multi-sector system reform, driven by her personal lived experience and caregiving journey in New Zealand and Australia. Her work emphasises essential carer and family inclusion, and she is a co-founder of EDCS.

KM (Ngāti Porou) is a lived experience caregiver. Having navigated the complexities of supporting a loved one with an eating disorder in both NZ and Australia, now advocates for positive sector change, increased peer support, and greater inclusion of caregivers and whānau in their vital role supporting recovery. This advocacy is amplified through the lived experience voice.

LD is a health and clinical psychologist who has worked with EDs in private practice, at a tertiary specialty service, and secondary mental health services. For the past two years, she has also been a caregiver to a child with deteriorating health.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Caregiver Demographic Statistics.

Table A1.

Caregiver Demographic Statistics.

| Sociodemographic factors |

n (%) |

| Gender |

|

| Female |

144 (94.12) |

| Male |

7 (4.58) |

| Transman |

1 (0.65) |

| Did not answer |

1 (0.65) |

| Relationship status |

|

| Single |

12 (7.84) |

| Dating |

4 (2.61) |

| Has partner/Married |

124 (81.05) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed |

11 (7.18) |

| Did not answer |

2 (1.31) |

| Agea

|

|

| 18 - 39 |

16 (10.46) |

| 40 - 64 |

130 (84.97) |

| 65 ≤ |

6 (3.92) |

| Did not answer |

1 (0.65) |

| Ethnicity |

|

| NZ European/European |

149 (97.39) |

| Māori |

10 (6.54) |

| Pacific Peoples |

2 (1.31) |

| Asian |

1 (0.65) |

| Other |

3 (1.96) |

| Education level |

|

| High school (NCEA Level 1, 2, or 3) |

22 (14.38) |

| University certificate or diploma |

38 (24.84) |

| Bachelor’s degree |

43 (28.10) |

| Postgraduate |

43 (28.10) |

| Overseas secondary school qualification |

1 (0.65) |

| No qualification |

2 (1.31) |

| Did not answer |

4 (2.61) |

| Household income (NZD) |

|

| ≤ $40,000 |

10 (6.54) |

| $40,000 – $59,999 |

10 (6.54) |

| $60,000 - $79,999 |

8 (5.23) |

| $80,000 - $99,999 |

9 (5.88) |

| $100,000 - $149,999 |

38 (24.84) |

| $150,000 - $199,999 |

17 (11.11) |

| $200,000 ≤ |

42 (27.45) |

| Preferred not to answer |

19 (12.42) |

| Employment Status |

|

| Full-time |

56 (36.60) |

| Part-time |

54 (35.29) |

| Working multiple jobs |

5 (3.27) |

| Unemployed |

28 (18.30) |

| Studying |

5 (3.27) |

| Did not answer |

5 (3.27) |

| Number of children |

|

| None |

11 (7.19) |

| One |

16 (10.46) |

| Two |

70 (45.75) |

| Three |

49 (32.03) |

| Over three |

7 (4.58) |

| Region |

|

| Northland |

7 (4.58) |

| Auckland |

49 (32.03) |

| Waikato |

8 (5.23) |

| Bay of Plenty |

13 (8.50) |

| Hawkes Bay |

5 (3.27) |

| Taranaki |

4 (2.61) |

| Manawatū-Whanganui |

4 (2.61) |

| Wellington |

24 (15.69) |

| Tasman/Nelson/Marlborough |

6 (3.92) |

| West Coast/Southland |

2 (1.31) |

| Canterbury |

28 (18.30) |

| Otago |

3 (1.96) |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Caregiver Role Characteristics.

Table A2.

Caregiver Role Characteristics.

| Role Factors |

n (%) |

| Relationship to person with the ED |

|

| Parent |

112 (73.20) |

| Partner |

3 (1.96) |

| Sibling |

3 (1.96) |

| Friend |

1 (0.65) |

| Other whānau member |

6 (3.92) |

| Other |

2 (1.31) |

| Did not answer |

26 (16.99) |

| Recency of caregiving |

|

| Currently a caregiver |

92 (60.13) |

| < 2 years ago |

29 (18.95) |

| 3-5 years ago |

18 (11.76) |

| 6-10 years ago |

9 (5.88) |

| >10 years ago |

3 (1.96) |

| Did not answer |

2 (1.31) |

| Hours per week of caregiving |

|

| < 20 hours |

6 (3.92) |

| 20-40 hours |

3 (1.96) |

| Over 40 hours/lives with person with ED |

83 (54.25) |

| Did not answer |

61 (39.87) |

| Sharing of the caregiver role |

|

| Regularly shared |

46 (30.07) |

| Occasionally shared |

28 (18.30) |

| Not shared |

21 (13.73) |

| Did not answer |

58 (37.91) |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Demographic Statistics of Individuals With the Eating Disorder.

Table A3.

Demographic Statistics of Individuals With the Eating Disorder.

| Sociodemographic Factors |

M (SD) |

| Current Age |

19.1 (6.1) |

| Age at Onset |

13.9 (2.8) |

| |

n (%) |

| Gendera

|

|

| Woman |

114 (89.06) |

| Man |

11 (8.59) |

| Non-binary |

3 (2.34) |

| Co-occurring Mental Health Disorders |

|

| Anxiety disorder |

87 (56.86) |

| Depressive disorder |

46 (30.07) |

| Autism spectrum disorder |

31 (20.26) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder |

23 (15.03) |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

21 (13.73) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

11 (7.19) |

| Other |

24 (15.69) |

| Timing of Development of Co-occurring Mental Health Disorder |

|

| Prior to developing ED |

55 (35.95) |

| After developing ED |

23 (15.03) |

| During |

22 (14.38) |

| Unsure |

5 (3.27) |

| Did not answer |

48 (31.37) |

| Eating disorder presentation |

n (%) |

| Diagnosed |

Suspected |

| Anorexia nervosa |

102 (66.67) |

6 (3.92) |

| Bulimia nervosa |

17 (11.11) |

5 (3.27) |

| Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder |

15 (9.80) |

11 (7.19) |

| Binge-eating disorder |

7 (4.58) |

5 (3.27) |

| Orthorexia |

1 (0.65) |

6 (3.92) |

| Rumination disorder |

3 (1.96) |

0 (0.00) |

| Other specified feeding or eating disorder |

3 (1.96) |

1 (0.65) |

| Unspecified feeding or eating disorder |

2 (1.31) |

3 (1.96) |

| Other |

4 (2.61) |

0 (0.00) |

Appendix D

Table A4.

Summary of Findings – Inaccessible Supports.

Table A4.

Summary of Findings – Inaccessible Supports.

| Inaccessible Supports |

Nr |

% |

| Inaccessible Supportsa

|

|

|

| Eating disorder-specialised support |

20 |

35.09 |

| Functional support |

8 |

14.04 |

| Financial support |

6 |

10.53 |

| Psychologists |

6 |

10.53 |

| Support groups |

6 |

10.53 |

| Therapy (unspecified) |

6 |

10.53 |

| Counselling |

5 |

8.77 |

| Reasons Support Soughtb

|

|

|

| General need for support |

10 |

41.67 |

| Need for caregiver mental health support |

7 |

29.17 |

| Caregiver unable to work without the additional support |

4 |

16.67 |

| Prior supports accessed were unhelpful |

3 |

12.50 |

| Main Barriersc

|

|

|

| Finances |

22 |

35.48 |

| Lack of availability |

22 |

35.48 |

| Individual with the ED being ineligible for support |

6 |

9.68 |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Feeding and Eating Disorders. In DSM Library. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th, text revision ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787.x10_Feeding_and_Eating_Disorders.

- Berglund, E., Lytsy, P., & Westerling, R. (2015). Health and wellbeing in informal caregivers and non-caregivers: A comparative cross-sectional study of the Swedish general population. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13(1), 109. [CrossRef]

- Binford Hopf, R. B., Grange, D. L., Moessner, M., & Bauer, S. (2013). Internet-Based Chat Support Groups for Parents in Family-Based Treatment for Adolescent Eating Disorders: A Pilot Study. European Eating Disorders Review, 21(3), 215–22. [CrossRef]

- Calvó-Perxas, L., Vilalta-Franch, J., Litwin, H., Turró-Garriga, O., Mira, P., & Garre-Olmo, J. (2018). What seems to matter in public policy and the health of informal caregivers? A cross-sectional study in 12 European countries. PLOS ONE, 13(3), e0194232. [CrossRef]

- Carers WA. (2024). Carers WA Policy Submission WA Eating Disorder Framework. Retrieved from https://www.carerswa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Carers-WA-Policy-Submission-WA-Eating-Disorder-Framework-1.pdf.

- Clark, M. T. R., Manuel, J., Lacey, C., Pitama, S., Cunningham, R., & Jordan, J. (2023). Reimagining eating disorder spaces: A qualitative study exploring Māori experiences of accessing treatment for eating disorders in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 22. [CrossRef]

- Cleland, L., Kennedy, H. L., Pettie, M. A., Kennedy, M. A., Bulik, C. M., & Jordan, J. (2023). Eating disorders, disordered eating, and body image research in New Zealand: A scoping review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J., Cayley, C., Lovibond, P. F., Wilson, P. H., & Hartley, C. (2011). Percentile Norms and Accompanying Interval Estimates from an Australian General Adult Population Sample for Self-Report Mood Scales (BAI, BDI, CRSD, CES-D, DASS, DASS-21, STAI-X, STAI-Y, SRDS, and SRAS). Australian Psychologist, 46(1), 3–14. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, D. C., & Hlebec, V. (2016). Predictors of Satisfaction with Life in Family Carers: Evidence From the Third European Quality of LIfe Survey. Teorija in Praksa, 53(2). Retrieved from https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/output/781337.

- Donkin, L., Sinclair, R., Rowland, S., McDougall, K., & Landon, J. (In preparation). “It’s never ending and overwhelming difficult”: The Impact of Caregiving for a Loved One With an Eating Disorder in New Zealand.

- Doocey, M. (2025, February 25). Refreshed eating disorders strategy announced during awareness week. Retrieved 13 March 2025, from Beehive.govt.nz website: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/refreshed-eating-disorders-strategy-announced-during-awareness-week.

- Eating Disorder Association New Zealand. (2024). Getting help: Eating disorder services in New Zealand. Retrieved 4 March 2024, from EDANZ website: https://www.ed.org.nz/getting-help/eating-disorder-services/.

- Eating Disorder Association New Zealand. (n.d.). Need help now? Retrieved 10 October 2024, from https://www.ed.org.nz/need-help-now.

- Eating Disorders Carer Support. (n.d.). Support, Resources & Advocacy for Carers in New Zealand/ Aotearoa. Retrieved 12 October 2024, from https://www.edcs.co.nz/home.

- Eating Disorders Victoria. (n.d.). Find Eating Disorder Support. Retrieved 17 May 2024, from Eating Disorders Victoria website: https://www.eatingdisorders.org.au/find-support/.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Erlingsson, C., & Brysiewicz, P. (2017). A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 7(3), 93–99. [CrossRef]

- Fichter, M. M., & Quadflieg, N. (2016). Mortality in eating disorders—Results of a large prospective clinical longitudinal study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(4), 391–401. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, L., Trip, H., Lawson, R., Wilson, N., & Jordan, J. (2021). Life is different now – impacts of eating disorders on Carers in New Zealand: A qualitative study. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9(1), 91. [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, S., Lock, J., & Grange, D. L. (2018). Family Based Treatment for Restrictive Eating Disorders: A Guide for Supervision and Advanced Clinical Practice. New York: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. R., Dean, M., & Whittlesea, A. (2017). The Experience of Caring For or Living with an Individual with an Eating Disorder: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 103–125. [CrossRef]

- Grennan, L., Nicula, M., Pellegrini, D., Giuliani, K., Crews, E., Webb, C., … Couturier, J. (2022). “I’m not alone”: A qualitative report of experiences among parents of children with eating disorders attending virtual parent-led peer support groups. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 195. [CrossRef]

- Haigh, R., & Treasure, J. (2003). Investigating the needs of carers in the area of eating disorders: Development of the Carers’ Needs Assessment Measure (CaNAM). European Eating Disorders Review, 11(2), 125–141. [CrossRef]

- Hannah, L., Cross, M., Baily, H., Grimwade, K., Clarke, T., & Allan, S. M. (2022). A systematic review of the impact of carer interventions on outcomes for patients with eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 27(6), 1953–1962. [CrossRef]

- Hay, P. (2020). Current approach to eating disorders: A clinical update. Internal Medicine Journal, 50(1), 24–29. [CrossRef]

- Institute for Eating Disorders. (2024). Treatment Services Database. Retrieved 16 October 2024, from InsideOut website: https://insideoutinstitute.org.au/treatment-services.

- Johns, G., Taylor, B., John, A., & Tan, J. (2019). Current eating disorder healthcare services – the perspectives and experiences of individuals with eating disorders, their families and health professionals: Systematic review and thematic synthesis. BJPsych Open, 5(4), e59. [CrossRef]

- Kalindjian, N., Hirot, F., Stona, A.-C., Huas, C., & Godart, N. (2022). Early detection of eating disorders: A scoping review. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 27(1), 21–68. [CrossRef]

- Kulshrestha, V., & Shahid, S. M. (2022). Barriers and drivers in mental health services in New Zealand: Current status and future direction. Global Health Promotion, 29(4), 83–86. [CrossRef]

- Kurnik Mesarič, K., Damjanac, Ž., Debeljak, T., & Kodrič, J. (2024). Effectiveness of psychoeducation for children, adolescents and caregivers in the treatment of eating disorders: A systematic review. European Eating Disorders Review, 32(1), 99–115. [CrossRef]

- Machado, P. P. P., Grilo, C. M., Rodrigues, T. F., Vaz, A. R., & Crosby, R. D. (2020). Eating Disorder Examination – Questionnaire short forms: A comparison. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(6), 937–944. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. (2008, January 1). Future directions for eating disorders services in New Zealand. Retrieved 3 May 2024, from National Library of New Zealand website: https://natlib.govt.nz/records/20906723.

- Ministry of Health. (2023). Quarterly Mental Health Report Quarter 4 2022/2023. Retrieved from https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/information-release/quarterly_mental_wellbeing_report_to_q4_2022_2023_watermarked_for_pr_1.pdf.

- Ministry of Health. (2024, March 14). Ministry of Health Eating Disorders Briefing. Retrieved from Eating disorders website: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/2024-08/h2024036864-briefing-eating-disorders.pdf.

- Ministry of Social Development. (n.d.). Child Disability Allowance. Retrieved 5 October 2024, from https://www.studylink.govt.nz/products/a-z-products/child-disability-allowance.html.

- Monteleone, A. M., Pellegrino, F., Croatto, G., Carfagno, M., Hilbert, A., Treasure, J., … Solmi, M. (2022). Treatment of eating disorders: A systematic meta-review of meta-analyses and network meta-analyses. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 142, 104857. [CrossRef]

- National Eating Disorders Collaboration. (n.d.). Service locator. Retrieved 16 October 2024, from NEDC website: https://nedc.com.au/support-and-services/service-locator.

- New Zealand Government. (2022, May 26). Further support for eating disorder services. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from Beehive.govt.nz website: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/further‐support‐eating‐disorderservices.

- Padierna, A., Martín, J., Aguirre, U., González, N., Muñoz, P., & Quintana, J. M. (2013). Burden of caregiving amongst family caregivers of patients with eating disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(1), 151–161. [CrossRef]

- Rhind, C., Salerno, L., Hibbs, R., Micali, N., Schmidt, U., Gowers, S., … Treasure, J. (2016). The Objective and Subjective Caregiving Burden and Caregiving Behaviours of Parents of Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review : The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 24. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, I., Stoyel, H., & Robinson, P. (2020). “If she had broken her leg she would not have waited in agony for 9 months”: Caregiver’s experiences of eating disorder treatment. European Eating Disorders Review, 28(6), 750–765. [CrossRef]

- Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System. (2021). Final Report – Summary and recommendations. Victoria. Retrieved from https://www.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-01/RCVMHS_FinalReport_ExecSummary_Accessible.pdf.

- Smith, A. R., Zuromski, K. L., & Dodd, D. R. (2018). Eating disorders and suicidality: What we know, what we don’t know, and suggestions for future research. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 63–67. [CrossRef]

- Surgenor, L. J., Dhakal, S., Watterson, R., Lim, B., Kennedy, M., Bulik, C., … Jordan, J. (2022). Psychosocial and financial impacts for carers of those with eating disorders in New Zealand. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 37. [CrossRef]

- Te Hiringa Mahara- the New Zealand Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission. (2024). Kua Tīmata Te Haerenga—The Journey Has Begun. New Zealand. Retrieved from https://www.mhwc.govt.nz/news-and-resources/kua-timata-te-haerenga/.

- Te Whatu Ora. (2023, June). Te Whatu Ora Carer Support Subsidy Purchasing Guidelines. Retrieved 11 October 2024, from https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/assets/Whats-happening/What-to-expect/For-the-health-workforce/Pay-equity-settlements/Care-and-support-workers/Te-Whatu-Ora-Carer-Support-Subsidy-Purchasing-Guidelines.pdf.

- Te Whatu Ora. (n.d.). Carer support subsidy. Retrieved 11 October 2024, from Seniorline website: https://www.seniorline.org.nz/support-for-carers-2/carer-support-subsidy/.

- The Eating Disorders Association of Ireland. (2024). Bodywhys—Support Services. Retrieved 17 May 2024, from Bodywhys website: https://www.bodywhys.ie/recovery-support-treatment/support-services-2/.

- Tse, A., Xavier, S., Trollope-Kumar, K., Agarwal, G., & Lokker, C. (2022). Challenges in eating disorder diagnosis and management among family physicians and trainees: A qualitative study. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 45. [CrossRef]

- Udo, T., & Grilo, C. M. (2019). Psychiatric and medical correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(1), 42–50. [CrossRef]

- Uehara, T., Kawashima, Y., Goto, M., Tasaki, S., & Someya, T. (2001). Psychoeducation for the families of patients with eating disorders and changes in expressed emotion: A preliminary study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 42(2), 132–138. [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. [CrossRef]

- Whāraurau. (n.d.). Online courses. Retrieved 8 October 2024, from Whāraurau website: https://www.wharaurau.org.nz/resource-category/online-courses.

- Yates, M. E., Tennstedt, S., & Chang, B.-H. (1999). Contributors to and Mediators of Psychological Well-Being for Informal Caregivers. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 54B(1), P12–P22. [CrossRef]

- Zaidman-Zait, A. (2014). Content Analysis. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research (pp. 1258–1261). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).