Submitted:

21 October 2024

Posted:

22 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Experience or Role of Researchers

2.3. Participants and Setting

2.4. Data Collection Instrument

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Quality and Rigor Criteria

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

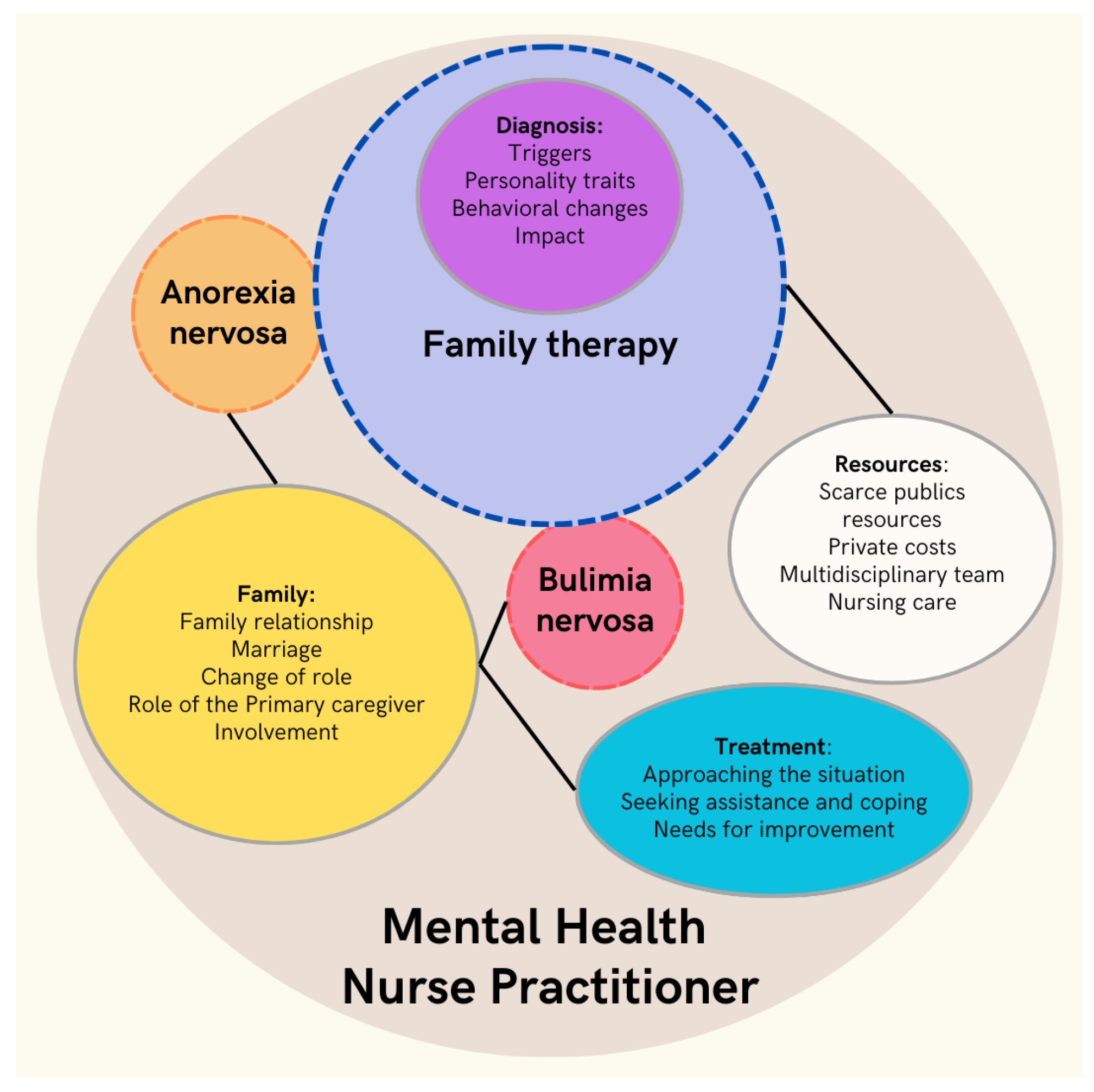

3.1. Themes

3.2. Theme 1. Diagnosis

"My relative compared herself to girls her age, questioning why they could eat without gaining weight, while she felt that she gained weight even when eating minimal amounts of food "E6.

"My relative faced a difficult emotional circumstance after her father´s death. She had a significant bereavement problem, which led her to self-harm and injure her wrists” E2.

"Well, of course, you see yourself locked up at home without being able to go out, without being able to do sport, locked up like a family therapy beast everything. We all eat lunch, breakfast, and dinner at the same time and there is no way to escape.... So, yes, it was very traumatic then because she didn't want to leave the room, she cried...". E2

"She exercised, she went to the gym a lot, she is a very active person, very controlling, if she leaves something somewhere she wants to see it there, she has everything very controlled" E10.

"(...) but it is not about being fat or thin; it is a deeper problem of accepting yourself as you are, that is to say, that the manifestation is food, but the origin is something else" E11.

"She used to be a cheerful and outgoing adolescent, but as a result of this whole process, she became defensive, bad-tempered, overreacting to any comment and even crying. The situation became complicated for everyone." E6

"I have always kept joking, and she has always played along with me... but I remember once I made a comment about her and her reaction was to start crying inconsolably. Apart from that, she was continually defensive." E7

"Mmm, I did not feel any special way because I already suspected it." E9

"Well, the truth is that I was surprised because we were waiting to be told that, but I did not think it was or she was in such a serious moment." E4

I felt confused at the time of diagnosis because I did not know what to do..."E7.

3.3. Theme 2. Family

"We are family, the family nucleus in this case is structured, his father and I are together, and we have another son... "E1

"His father had died [...], he began to have a lot of problems at home, with his mother, he did not want to be with her, he wanted to leave home" E8.

"A normal relationship, of trust, of asking for your opinion, advice... I mean, each adolescent is different, but it was a normal relationship" E12.

"No, it didn't change, it hasn't changed. Not at all, it has strengthened; on the contrary, it has made us stronger" E1.

"To act on the illness you need to lie, don't you? And then, of course, everything changed." E9

"I had to change my daily life " E4 "The first year of holidays I remember it as a nightmare, we took her out of her comfort zone and it was chaotic." E6

"It worsened my relationship with my wife." E7

"We had many problems within the family nucleus, as my wife and I did not agree on the best way for her to be cured. We argued every day, we cried out of helplessness and although our aim was the same, we could not agree" E7.

"Above all, we saw that it was fundamental to be well in the marriage. That was paramount. And then, if you are well, you can help your children, but if not, you can't" E3.

"He changed with his siblings, because also siblings at the beginning tend to.... to watch over... and the role of siblings is not that" E4.

"You see that a person is drowning and you throw them a float, and they don't catch it" E4.

"Feeling hopeless... hopeless, I didn't see myself as capable" E7.

" (…) there were courses for families on how to deal with Christmas, meetings… and, believe me, that was fundamental to me and I truly believe, it was very important for her also" E2.

3.4. Theme 3. Resources

"The public health system, in my opinion, has very few resources for this type of patient" E7.

"Because of social security, they offered us a psychologist almost for the following year" E12.

"(…) Yes, during her hospitalization, yes… she was very grateful because all the professionals in the hospital helped her a lot, they were great, but after that... mmm... I think it was not enough, she did not have a proper follow-up" E5.

"She has been managing it privately, she has had to struggle and look for help on her own" E4

"I was shocked at the prices charged by each one, there are few of them, and on top of that, they are very expensive privately" E7.

"Nursing professionals have an essential role in the approach" E4.

"Honestly, I don't know because... surely yes, it is possible that nursing plays an important role, but so far we have not had the opportunity to learn about it" (E7).

"It is very important that the doctor sees you, but the follow-up by the nurse…" E1.

3.5. Theme 4. Treatment

"Experience is the mother of science" E2.

"Act quickly and don't keep thinking that it can't be because your daughter is idyllic... because you think that it can't happen to her and it does happen, and that ends up prejudicing the diagnosis of her illness" E6.

"I think this help could be improved by doing family therapy, group therapy, or including family members in some kind of consultation or information session... to include them in the treatment as they are going to be the main caregivers" E4.

"I would like everything to be easier and quicker" E6.

"Like when you have a cold and they prescribe paracetamol, just the same” E1.

"I've read that it's what we know the least about; maybe they need to do more research" E5.

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Nursing Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfoukha, M.M.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; Banihani, M.A. Social and psychological factors related to risk of eating disorders among high school girls. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 35, 169–177. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Romero, M.R.; Montoro-Pérez, N.; Martín-Baena, D.; Talavera-Ortega, M.; Montejano-Lozoya, R. A descriptive cross-sectional study on eating disorders, suicidal thoughts, and behaviors among adolescents in the Valencian Community (Spain). The pivotal role of school nurses. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2024, 75, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Jowik, K.; Dutkiewicz, A.; Słopień, A.; Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M. A multi-perspective analysis of dissemination, etiology, clinical view and therapeutic approach for binge eating disorder (BED). Psychiatr. Pol. 2020, 54, 223-238. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-V-TR; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Yu, Z.; Muehleman, V. Eating disorders and metabolic diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2446. [CrossRef]

- Mora, F.; Alvarez-Mon, M.A.; Fernandez-Rojo, S.; Ortega, M.A.; Felix-Alcantara, M.P.; Morales-Gil, I.; Quintero, J. Psychosocial factors in adolescence and risk of development of eating disorders. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1481. [CrossRef]

- Wilksch, S.M.; O'Shea, A.; Ho, P.; Byrne, S.; Wade, T.D. The relationship between social media use and disordered eating in young adolescents. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 96–106. [CrossRef]

- Phillipou, A.; Meyer, D.; Neill, E.; Tan, E.J.; Toh, W.L.; Van Rheenen, T.E.; Rossell, S.L. Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1158–1165. [CrossRef]

- Alsheweir, A.; Goyder, E.; Alnooh, G.; Caton, S.J. Prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviours amongst adolescents and young adults in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4643. [CrossRef]

- Van Eeden, A.E.; Van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 515–524.

- Lozano, N.; Borrallo, Á.; Guerra, M.D. Anales del sistema sanitario de Navarra. An. Sist. San. Navarra 2022, 45, e1009.

- Lindvall Dahlgren, C.; Wisting, L.; Rø, Ø. Feeding and eating disorders in the DSM-5 era: A systematic review of prevalence rates in non-clinical male and female samples. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 56. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.R.; Zuromski, K.L.; Dodd, D.R. Eating disorders and suicidality: What we know, what we don’t know, and suggestions for future research. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 22, 63–67. [CrossRef]

- Sattler, F.A.; Eickmeyer, S.; Eisenkolb, J. Body image disturbance in children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A systematic review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2020, 25, 857–865. [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 231–243. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H.; Prawira, B.; Windfuhr, K.; Irmansyah, I.; Lovell, K.; Syarif, A.K.; Dewi, S.Y.; Pahlevi, S.W.; Rahayu, A.P.; Syachroni; Afrilia.; et al. Mental health literacy amongst children with common mental health problems and their parents in Java, Indonesia: A qualitative study. Glob. Ment. Health (Camb.)2022, 9, 72–83. [CrossRef]

- Özer, D.; Şahin Altun, Ö. Nursing students' mental health literacy and resilience levels: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2024, 51, 222–227.

- Nobre, J.; Oliveira, A.P.; Monteiro, F.; Sequeira, C.; Ferré-Grau, C. Promotion of mental health literacy in adolescents: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9500. [CrossRef]

- Cormier, E.; Park, H.; Schluck, G. College students' eMental health literacy and risk of diagnosis with mental health disorders. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10, 2406. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.; Sequeira, C.; Querido, A.; Tomás, C.; Morgado, T.; Valentim, O.; Moutinho, L.; Gomes, J.; Laranjeira, C. Positive mental health literacy: A concept analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 877611. [CrossRef]

- Flütsch, N.; Hilti, N.; Schräer, C.; Soumana, M.; Probst, F.; Häberling, I.; Berger, G.; Pauli, D. Feasibility and acceptability of home treatment as an add-on to family-based therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: A case series. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1707–1710. [CrossRef]

- Holtom-Viesel, A.; Allan, S. A systematic review of the literature on family functioning across all eating disorder diagnoses in comparison to control families. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 29–43. [CrossRef]

- Dezutti, J.E. Eating disorders and equine therapy: A nurse's perspective on connecting through the recovery process. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2013, 51(9), 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Navas-Echazarreta, N.; Satústegui-Dordá, P.J.; Rodríguez-Velasco, F.J.; García-Perea, M.E.; Martínez-Sabater, A.; Chover-Sierra, E.; Ballestar-Tarín, M.L.; Del Pozo-Herce, P.; González-Fernández, S.; de Viñaspre-Hernández, R.R.; et al. Media Health Literacy in Spanish Nursing Students: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2565–2579. [CrossRef]

- Cole, B. Understanding eating disorders and the nurse's role in diagnosis, treatment, and support. J. Christ. Nurs. 2024, 41(2), 80–87.

- Giorgi, A. Concerning the application of phenomenology to caring research. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2000, 14(1), 11–15. [CrossRef]

- Norlyk, A.; Harder, I. What makes a phenomenological study phenomenological? An analysis of peer-reviewed empirical nursing studies. Qual. Health Res. 2010, 20(3), 420–431. [CrossRef]

- Van Hout, M.C.; Crowley, D.; O'Dea, S.; Clarke, S. Chasing the rainbow: Pleasure, sex-based sociality and consumerism in navigating and exiting the Irish Chemsex scene. Cult. Health Sex. 2019, 21(9), 1074–1086. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.; Poth, C. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2018.

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A.L. Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge, 2017.

- Kusi, G.; Boamah Mensah, A.B.; Boamah Mensah, K.; Dzomeku, V.M.; Apiribu, F.; Duodu, P.A.; Adamu, B.; Agbadi, P.; Bonsu, K.O. The experiences of family caregivers living with breast cancer patients in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9(1), 165. [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection, and analysis. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24(1), 9–18. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Is thematic analysis used well in health psychology? A critical review of published research, with recommendations for quality practice and reporting. Health Psychol. Rev. 2023, 17(4), 695–718. [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Criterios consolidados para informar investigaciones cualitativas (COREQ): Una lista de verificación de 32 elementos para entrevistas y grupos focales. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357.

- O'Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89(9), 1245–1251.

- Canals, J.; Arija, V. Risk factors and prevention strategies in eating disorders [Factores de riesgo y estrategias de prevención en los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria]. Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39(Spec No2), 16–26.

- Mora, F.; Álvarez-Mon, M.A.; Fernández-Rojo, S.; Ortega, M.A.; Félix-Alcantara, M.P.; Morales-Gil, I.; Rodríguez-Quiroga, A.; Álvarez-Mon, M.; Quintero, J. Psychosocial factors in adolescence and risk of development of eating disorders. Nutrients 2022, 14(7), 1481. [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.; Žigić Antić, L.; Žaja, O.; Jakovina, T.; Begovac, I. Predictor of eating disorder risk in anorexia nervosa adolescents. Acta Clin. Croat. 2018, 57(3), 399-410.

- Mento, C.; Silvestri, M. C.; Muscatello, M. R. A.; Rizzo, A.; Celebre, L.; Praticò, M.; Zoccali, R. A.; Bruno, A. Psychological impact of pro-anorexia and pro-eating disorder websites on adolescent females: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res and Public Health 2021, 18(4), 2186. [CrossRef]

- Joy, E. A.; Wilson, C.; Varechok, S. The multidisciplinary team approach to the outpatient treatment of disordered eating. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2003, 2(6), 331-336. [CrossRef]

- Guillén, V.; Arnal, A.; Pérez, S.; Garcia-Alandete, J.; Fernandez-Felipe, I.; Grau, A.; Botella, C.; Marco, J. H. Family connections in the treatment of relatives of people with eating disorders and personality disorders: Study protocol of a randomized control trial. BMC Psychol 2023, 11(1), 88. [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.; Tay, Y.; Klainin-Yobas, P. Mental health literacy levels. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 757–763. [CrossRef]

- Pelone, F., Jacklin, P., Francis, J. M., & Purchase, B. Health economic evaluations of interventions for supporting adult carers in the UK: A systematic review from the NICE Guideline. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2022, 34(9), 839-852. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M., Corral, I., González, J., Fernández, S., Becerro, R., & Losa, M. Anales del sistema sanitario de Navarra. An. sist. Sanit. 2021, 44(1), 41-49.

- Johns, G., Taylor, B., John, A., & Tan, J. Current eating disorder healthcare services: The perspectives and experiences of individuals with eating disorders, their families, and health professionals. BJPsych Open 2019, 5(4), e59.

- Figueroa, L. M., & Soto, M. Transitional care from adolescence to adulthood. Rev. de Salud Pública (Bogotá, Colombia) 2018, 20(6), 784-786.

- Corral, I., Alonso, M., González, J., Fernández, S., Becerro, R., & Losa, M. Holistic nursing care for people diagnosed with an eating disorder: A qualitative study based on patients and nursing professionals' experience. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58(2), 840-849.

- Morgado, T., & Botelho, M. R. Intervenções promotoras da literacia em saúde mental dos adolescentes: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Revista Portuguesa de Enfermagem e Saúde Mental 2014, 1, 90–96.

- Kieling, C., Baker-Henningham, H., Belfer, M., Conti, G., Ertem, I., Omigbodun, O., Rohde, L. A., Srinath, S., Ulkuer, N., & Rahman, A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. The Lancet 2011, 378, 1515–1525. [CrossRef]

| Participants | Sex of interviewee | Age of interviewee | Relationship | EDs diagnosis | Age at diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E 1 | Woman | 56 | Mother | Anorexia nervosa | 19 |

| E 2 | Woman | 51 | Mother | Anorexia nervosa | 17 |

| E 3 | Man | 54 | Father | Anorexia nervosa | 17 |

| E 4 | Woman | 21 | Sister | Anorexia nervosa | 18 |

| E 5 | Man | 75 | Grandfather | Bulimia nervosa | 17 |

| E 6 | Woman | 49 | Mother | Anorexia nervosa | 17 |

| E 7 | Man | 50 | Father | Anorexia nervosa | 17 |

| E 8 | Woman | 25 | Sister | Bulimia nervosa | 18 |

| E 9 | Woman | 54 | Mother | Anorexia nervosa | 17 |

| E 10 | Man | 51 | Father | Anorexia nervosa | 17 |

| E 11 | Woman | 57 | Mother | Anorexia nervosa | 18 |

| E 12 | Man | 52 | Father | Bulimia nervosa | 17 |

| Research area | Interview Questions |

| Diagnostic feeling |

|

| Family relations |

|

| Assistance |

|

| Treatment |

|

| Criteria | Techniques and procedures used |

| Credibility | - Researcher triangulation: each interview was analyzed by five researchers (E.G.C-B, C.G-M, A. T-R, E.M-M, P.D.-H) and two researchers with clinical and research experience in mental health (P.D.-H; C.G.-N). Team meetings were held to compare analyses and identify categories and themes with the rest of the team. - The analysis was carried out by five researchers and an external auditor (E.V-V). - Triangulation of data collection methods: Semi-structured interviews were conducted and field notes were taken by the researchers. - Participant validation (member-checking): Participants were offered the opportunity to review the audio recordings to confirm their experience. No additional comments were made by any of the participants. |

| Transferability | - Detailed descriptions of the study conducted, detailing the characteristics of the researchers, participants, settings, sampling strategies, and data collection and analysis procedures. |

| Reliability / Trustworthiness | - External researcher audit: An external researcher (E.V-V) assessed the research protocol, focusing on the methods applied and the study design. |

| Confirmability | - Researcher triangulation, member checking, and data collection triangulation. |

| Themes (T) | Categories | |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | Diagnosis | Triggers Personality traits Behavioral changes Impact |

| T2 | Family | Family relationship Marriage Change of role Role of the primary caregiver Involvement |

| T3 | Resources | Scarce publics resources Private costs Multidisciplinary team Nursing care |

| T4 | Treatment | Approaching the situation Seeking assistance and coping Needs for improvement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).