Introduction

Various physical and emotional impacts can arise from caring for someone with an eating disorder (ED) (Berglund et al., 2015; Calvó-Perxas et al., 2018; Fletcher et al., 2021; Robinson et al., 2020; Romero-Martínez & Moya-Albiol, 2017; Surgenor et al., 2022). Caregivers can experienced high levels of anxiety, depression, and perceived burden (Anastasiadou et al., 2014; Fox et al., 2017; Zabala et al., 2009). Guilt for their loved one’s condition may occur, worry about their loved one’s physical wellbeing, and grief when witnessing the health of the individual with the ED decline (Clark et al., 2023). When stressed and tired, irritability, anger, and frustration occur more readily. Furthermore, in some treatments, such as Family Based Treatment (FBT), the therapist intentionally increases caregiver anxiety by emphasising the seriousness of the disorder and the difficulty in achieving remission (Duclos et al., 2023) to mobilise the caregiver into action (Rienecke & Le Grange, 2022). Even following ED remission, caregivers can continue to be impacted by heightened vigilance and worry (Fletcher et al., 2021). These emotional impacts can be exacerbated by experiencing stigma around EDs, role strain, financial strain from the cost of treatment and support seeking, and the lack of information and support availability compound this psychological distress (Rhind et al., 2016; Treasure & Nazar, 2016; Whitney et al., 2007).

Positive aspects associated with caregiving do occur and can buffer the negative impacts (Hannah et al., 2021; Padierna et al., 2013). Across the literature, positive caregiving experiences have been found to mediate the relationship between caregiver burden and life satisfaction (Anastasiadou et al., 2014; Nemcikova et al., 2023; Quinn & Toms, 2019). If the caregiver considers their role to be enjoyable, meaningful or rewarding, caregiving can build self-esteem and improve life satisfaction. Seeing their loved one recover from an ED is the key goal, and seeing signs of recovery can make caregiving seem worthwhile.

Social support can considerably influence a caregiver’s capacity to cope with caregiving stressors. Caregivers receiving social support display more adaptive coping strategies than those without (Kulshrestha & Shahid, 2022). However, accommodating the perceived needs of the individual with the ED can substantially impact a caregiver’s capacity to engage in life, health and social activities (Kumar et al., 2024). For example, caregivers may avoid eating at restaurants to facilitate the observation of rigid mealtimes (Rhind et al., 2016) or due to feeling that they need to be constantly available to the person with the ED. Social engagement becomes even more reduced when caring for an individual with high needs, such as anorexia nervosa (AN) (Clark et al., 2023). Caregivers frequently sacrifice occupational, social, and leisure activities (Rhind et al., 2016), leading to feelings of isolation, disconnection, and worsening psychological and physical health.

Exploration of the impact of caregiving for individuals living with an ED in NZ is only in its infancy. Surgernor et al. (2022) found that 93.2% of caregivers felt family life had been significantly impacted while 89% of caregivers noted a reduced quality of life, reflecting the burden of care experienced. These impacts were reflected in qualitative study by Fletcher et al. (2021) that found an overarching theme that ‘life is different now’. Even following recovery, caregivers continued to be impacted by heightened vigilance and worry (Romero-Martínez & Moya-Albiol, 2017). Beyond these studies, little NZ literature explores the impact of caregiving for an individual living with an ED. Understanding the impact of caregiving could help us understand how to better support caregivers. Therefore, we aimed to explore the impacts of caregiving for an individual with an ED in NZ.

Method

This study utilised an online anonymous survey including psychometrics and open-text questions. The use of this approach is a similar methodological approach to prior NZ ED literature (Clark et al., 2023; Fletcher et al., 2021; Surgenor et al., 2022), and was developed in conjunction with Eating Disorder Carer Support NZ stakeholders (EDCS; SR and KM). The base survey consisted of 129 closed questions and 14 open questions covering a range of aspects related to caregiving experiences and support needs. Results on supports needs and access to supports is reported elsewhere (Sinclair et al., 2025).

Participants

Eligible participants were current or former adult caregivers in New Zealand of an individual with a diagnosed or suspected ED. To participate, caregivers needed to be proficient in English, and have access to an internet connection.

Recruitment

Recruitment occurred between 27th of March 2024 and 30th of June 2024 through study invitation to ED stakeholders identified through an internet search. Unpaid social media advertising was also undertaken by the researchers, and through stakeholders sharing the study invitation through their networks. Study information was provided at the start of the survey with consent being implied through participation. Ethical approval was received from the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (24/050).

Measures

Mood Assessment

Mood was assessed using the 21-item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). The DASS-21 consists of three subscales: Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. Subscale scores are calculated by summing the scores of the seven corresponding items for each scale. To compare to the DASS-42 scale, subscale scores can be multiplied by two. Total scores range from 0 to 126 with higher scores indicating a higher level of symptoms. The DASS-21 has sound psychometric properties, with very strong internal consistency across subscales (Depression: α = .91; Anxiety: α = .84; Stress: α =.90; Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995) and the total scale (α = .93 Henry & Crawford, 2025). The DASS-21 has been widely used internationally (Medvedev, 2023) including with caregivers of people living with an ED (Stefanini et al., 2019).

Impact of Eating Disorder Symptoms

The Eating Disorders Symptom Impact Scale (EDSIS; Speulveda et al., 2008) was used to measure caregiver burden and the impact the ED has on family life. The EDSIS comprises of 24 5-point Likert scale responses ranging from “never” (0) to “nearly always” (4). The EDSIS contains four subscales: Nutrition, Guilt, Social Isolation, and Dysregulated Behaviour. Subscale scores are calculated by summing the scores of the respective scale items. The EDSIS composite score is the sum of the subscale scores, with a possible range of 0 to 96. Higher scores indicate a more negative appraisal of the measured caregiving aspect(s).

Reliability of the EDSIS is acceptable (α = .69-.90) (Coomber & King, 2013; Sepulveda et al., 2008), with strong internal consistency across the individual subscales also (Nutrition: α = .89; Guilt: α = .84; Dysregulated Behaviours: α = .82; Social Isolation: α = .86; (Sepulveda et al., 2008)). The EDSIS has been moderately correlated with the negative burden subscale of the Experiences of Caregiving Inventory (.42 ≤ r ≤ .60) (Sepulveda et al., 2008) and the General Health Questionnaire-12 (Coomber & King, 2013).

Accommodating and Enabling Caregiver Behaviours

The Accommodation and Enabling Scale for Eating Disorders (AESED; (Sepulveda et al., 2009)) measures caregiver behaviours in response to the ED, and the emotional impact of these behaviours on caregivers. The AESED contains 33 items, 32 of which are 5-point Likert scale responses with item responses of “never” (0), through to “nearly always” (4). A Visual Analogue Scale from 0 to 10 is used for Item 28: “In general, to what extent would you say that the relative with an ED controls your family life and activities?”. For scoring purposes, Item 28 is converted to a 5-point Likert scale response (0 and 1 = 0; 2 and 3 = 1; 4, 5, and 6 = 2, 7 and 8 = 3, 9 and 10 = 4;). The AESED has five subscales: Reassurance Seeking, Avoidance and Modifying Routine, Meal Ritual, Control of Family, and Turning a Blind Eye. The AESED subscale scores are summed to calculate a total score with a possible range of 0 to 132. For both total and subscale scores, higher scores indicate greater family accommodation of ED symptoms. The AESED has sound psychometric properties with very strong internal consistency across both the total measure (α = .92), and subscales (Reassurance Seeking: α = .86; Avoidance and Modifying Routine: α = .90; Meal Ritual: α = .86; Control of Family: α = .85; Turning a Blind Eye: α = .77; (Sepulveda et al., 2009)).

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29. A sample of 153 (56.0%) people was included in the analysis based on meeting the minimum requirement of completing 5% of the survey or more. Missing data were managed by using the mean of related subscale items for that participant, with participants missing more than one item per subscale being excluded. Measures were checked for kurtosis and skewness which indicated that the data were approximately normal and therefore parametric statistics were used for the analysis. Two-tailed, one sample T-tests were used to compare the results for the DASS-21, EDSIS, and AESED with previous studies.

Analysis of Open-Text Questions

Content analysis (CA) was used for the open-text questions as it is a systematic way to meaningful handle large amounts of qualitative data (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). The method of content analysis used can be found in Sinclair et al. (in preparation).

Results

Caregiver Demographics

Caregiver demographics are presented in

Table 1. Seventy-three point two per cent (

n = 112) of participants were parents of the person with the ED, 5.9% (

n = 9) were other family members, and 2.0% (

n=3) were partners. Of those that were currently caregivers (

n = 92; 60.1%), most lived with the person that had the ED (

n = 83; 90.2%) and provided around the clock care.

In terms of the clinical presentation of the people with the ED, the average age of onset for disorder eating symptoms was 13.9 years (SD =2.8). The most common ED presentation was AN (n =109; 71.2%) followed by avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (n = 28; 18.3%), then bulimia nervosa (n = 22; 14.4%). Co-occurring mental health issues were common with approximately 57% (n = 87) experiencing anxiety, 31% (n = 47) experiencing depression, 20% (n = 31) were autistic, 15% (n = 23) had post-traumatic stress disorder, and approximately 14% (n = 21) had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. For those with co-occurring mental health conditions, 36% of people experienced the mental health difficulties developing prior to the onset of the ED.

Impact of Caregiving

Caregivers reported a range of negative impacts related to caregiving but were also able to describe positive experiences (see

Table 2). It is noted that the majority of codes generated related to the negative emotional impact of caregiving and few participants reported the positive aspects, likely reflecting the burden experie

nced by caregivers.

“Everything. The stress of trying to get them to eat, the mental anguish they have, self-harm, suicidal thoughts and will they act on that? Trying to be there for your other loved ones as they need their mum and wife also. The financial toll, having to give up work and to get specialist help means you pretty much have to go private. And the help that is given is to the person with the eating disorder which is the most important, but you feel left out in the cold trying to make your child eat and navigate all that entails.”

“The stress, exhaustion, effects on my mental and physical health and finances.”

Emotional Impact of Caregiving

Of the role-related factors that negatively impacted caregivers (nc = 704), the emotional impact was the greatest occurring in 63.21% of codes (nc = 445). The main emotional impacts experienced by caregivers were feelings of anxiety (23.82%, nc = 106), depression (11.91%, nc = 53), and isolation (10.79%, nc = 48).

“A lonely process, but worth every tear, every ounce of pain to get my [child] well.”

“It feels very lonely as it is not something people really understand unless they have been there. People think that you can just tell the child to eat more and it will all be sorted. They don't understand that the mental battle going on means the child can't eat normally. It is the hardest and most isolating experience I have ever been through.”

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Symptoms

Caregiving led to a decline in the mental (8.81%, nc = 62) and physical health of caregivers (3.84%, nc = 27), as well as having negative financial impacts (5.40%, nc = 48). Pervasive psychosocial impacts (10.09%, nc = 71) were also evident as the ED impacted not only the caregiver but also their immediate family and jobs:

“Fear that she'll never recover, terror that in the morning I'll wake up and find her dead.”

“Managing own emotions (fear, despair, sadness) in order to help my daughter manage her strong emotions.”

“Constant worry about relapse into full blown refusal to eat. The stress is all day every day.”

Psychometric scores for all scales used can be found in

Table 3. The mean score for caregivers fell in the moderate range for depression and stress, and the mild range for anxiety. When comparing participants who were currently caregivers with those who are no longer caregiving, participants currently caring for an individual with an ED had significantly higher levels of depression (

t(126) = 3.98,

p < .001) and stress (

t(126) = 3.79,

p < .001) than those no longer caregiving. Anxiety levels approached but did not reach significa

nce with anxiety being lower in past caregivers compared to current caregivers (

t(126) = 1.69,

p = .09).

Compared to the Australian general population (Crawford et al., 2011), current caregivers experienced significantly higher levels of depression (t(76) = 11.530, p < .001), anxiety (t(76) = 7.290, p < .001) and stress (t(76) = 14.726, p < .001). Overall, respondents were also found to have significantly higher levels of depression (t(76) = 5.967, p < .001), anxiety (t(76) = 3.987, p < .001) and stress (t(76) = 5.847, p < .001) than Australian caregivers.

Impact of the ED on Caregivers and Families

There were notable differences in the types of accommodating and enabling behaviours NZ and Australian caregivers (Stefanini et al., 2019) engaged in as measured by the EDSIS. Compared to Australian caregivers, participants were more accommodating and enabling of meal rituals (t(57) = 4.317, p < .001) and avoidant and modifying of routines (t(57) = 5.932, p < .001). However, Australian caregivers felt that their family was more controlled by the ED (t(58) = -2.505, p < .015) and the individual with the ED needed more reassurance (t(56) = -2.262, p = .028).

“The impact on our family and younger siblings. Eating disorder has and remains the constant focus. Trauma for our younger children due to FBT and watching their sister struggle every day, every meal. Constantly in a state of vigilance, constantly providing oversight. High levels of stress at times.”

The impact of ED symptoms on family life and the level of caregiver burden experienced as measured by the AESES was higher in our participants than in Australian caregivers (Lefkovits et al., 2024) (t(59) = 3.384, p= .001). Specifically, the family lives of our participants were found to be more impacted by guilt (t(59) = 2.813, p =.007), dysregulated behaviour (t(59) = 6.105, p<.001), and the social impact of the ED (t(59) = 2.054, p=.044) than Australian caregivers.

“Hide/secure sharp objects and meds, reducing paid work, having to travel to school to supervise eating, not being able to attend school full time, not being able to commit to future plans, needing to be contactable at all times… I could go on.”

Many participants described financial impacts on their families from being unable to work or being under significant stress due to balancing work, caregiving and the needs of other children. This adversely impacted the mental health of participants and their ability to care for their loved one.

“She was living with me, I'm a solo mum, [she] needed 24/ 7 care. I had to work; her treatment team told me not to, but defaulting on my mortgage and not having money to pay for all the food and medical treatment was not an option. [Financial aid service] are useless. I had no/minimal family support”.

“This is the hardest thing our family has ever had to go through. It impacted every aspect of our family life and to this day I am still trying to come to terms with the treatment and life moving forward when life has been on hold for so long.”

“Juggling the opposing needs of 2 children with different disorders (1 recovering from anorexia and 1 with ASD [autism spectrum disorder] and ARFID [avoidant restrictive food intake disorder] possibly triggered by the anxiety of living with their sibling through family-based treatment).”

Long-term impact on Caregivers

The greatest long-term impacts reported by caregivers (nc = 376) were the emotional impacts (47.87%, nc = 180), and the impact on the caregiver’s mental (10.11%, nc = 38) and physical health (9.57%, nc = 36). Caregivers were emotionally impacted in multiple ways, particularly with long-term anxiety, often associated with fear of relapse:

“Our [child] struggled with an eating disorder for approximately 12 months. It was a very difficult and stressful period which brings back painful memories. While [they] have made a good recovery you never assume that will always be the case so I guess there is a degree of anxiety around the future for [them] at times.”

“It has broken a tight relationship my daughter I have always had. Being made to go through the FBT model with no other members in the household my daughter or her ED hates me with a passion I just want to be her mum and be there for her and hold her and comfort her not drive her away from me. I’ve had to give up work I'm isolated and there is no support to treat this.”

Specific long-term challenges that caregivers continued to experience were anxiety and fear (22.78%, nc = 4), ongoing intrusive memories and hypervigilance related to caring for their loved ones (18.33%, nc = 33), a continued sense of disconnection and isolation from peers (10.56%, nc = 19), chronic exhaustion (8.33%, c 15), ongoing restlessness (5.56%, nc = 10), and depression (5.0%, nc = 9). A further 29.4% (nc = 53) reported ongoing unspecified symptoms that indicated a worsening of mental and physical health compared to before becoming a caregiver.

“Social isolation for the initial period when my daughter did not want to disclose her condition to anyone, continued social isolation as even those who know cannot understand the stress and continued worry about a lasting recovery.”

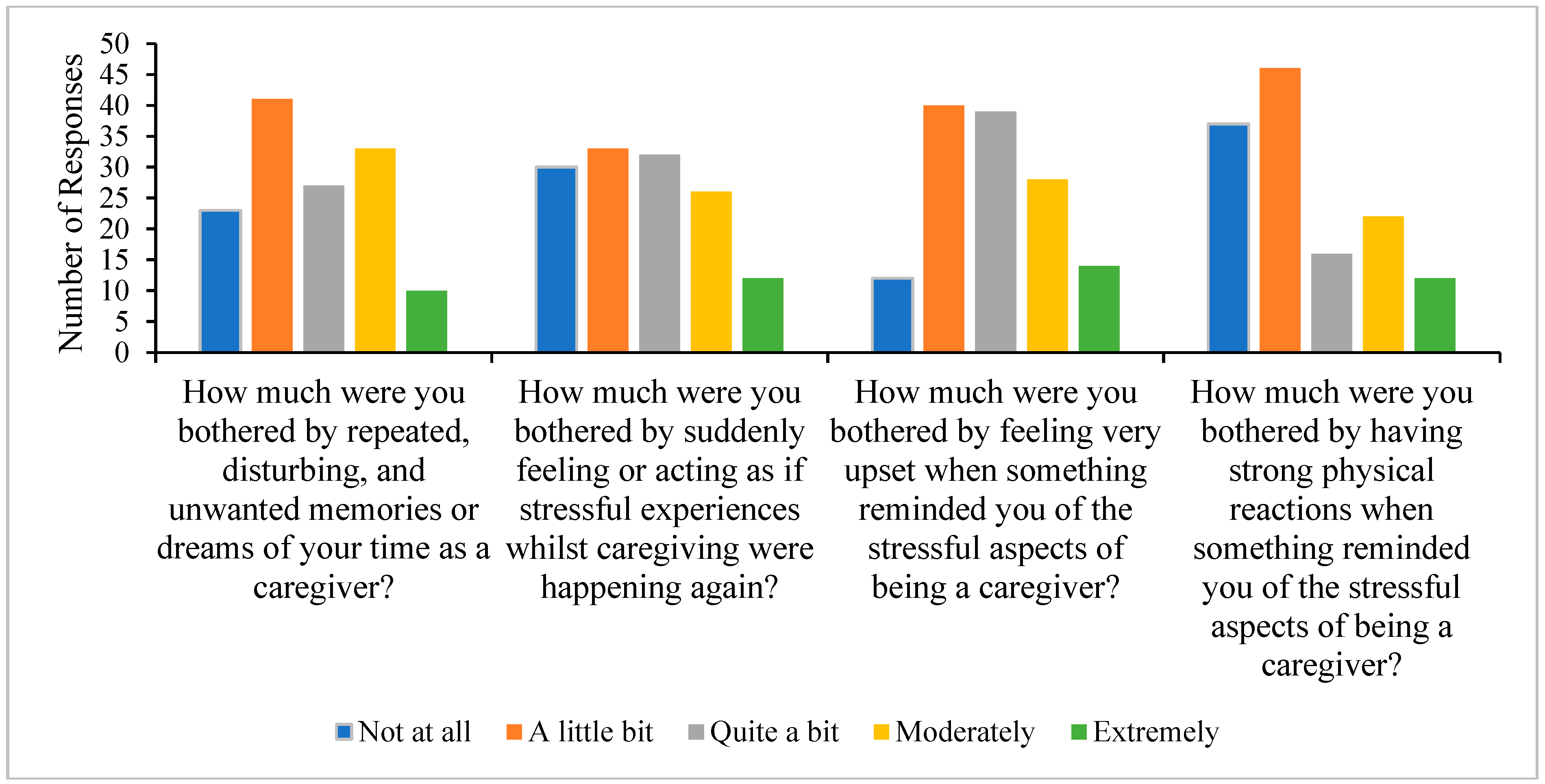

Caregivers were also vulnerable to experiencing traumatic stress-like symptoms as a result of the caregiving of their loved one through the recovery process (refer to

Figure 1). More than 30% of participants reported being moderately or extremely bothered by disturbing memories of their time being a caregiver, approximately 38% were moderately to extremely distressed from feeling as though they were reliving their caregiving experie

nce, approximately 31% were moderately or severely distressed when reminded about their caregiving experie

nce, and approximately 25% had moderate to severe physical reactions to reminders of caregiving.

“I can no longer care for her. I have PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] and get panic attacks. She's living with [parent] who has stepped up for the first time in over two years. Before she went to her [other parent's] I wasn’t sleeping, it was affecting my work. My kids are as burnt out from anorexia as I am. I said to [regional specialist service], I'm collateral damage and you don't give a f##&.”

“My therapist has suggested that through caring for my [loved one], I developed a difficulty to detach from conflict, and am often unable to temper my response. I jump to worst case scenario and catastrophize things in my head. [Therapist] thought that this may have been because when my [loved one] was sick it was a 'help/react or she dies' situations a lot of the time.”

Positive Experiences of Caregiving

Even though the emotional impact associated with caregiving was significant, a few caregivers noted positive experiences arising from their caregiving journey (3.41%; nc = 24). Previous caregivers described experiences that included post-ED growth, the development of positive coping strategies, a strengthened family unit, gratitude, and hope for the future. Despite all the support received, very few supports were considered to contribute to positive experiences. Moreover, the number of positive caregiving experiences was hugely outweighed by negatively perceived impacts.

Discussion

This study identified significant caregiver burdens associated with caring for a loved one with an ED in NZ. Specifically, high levels of anxiety, depression, and stress were found, exceeding those reported in the Australian ED caregiver and general populations (Lefkovits et al., 2024; Stefanini et al., 2019). Whilst it was found that the levels of distress decreased following recovery, many caregivers reported ongoing symptoms of the traumatic stress that they experienced during caregiving, hypervigilance for signs that their loved one was relapsing, and ongoing disconnection and isolation from their peers. Positive aspects of caregiving were occasionally noted but these were outweighed by the negative impacts.

The high level of psychological burden associated with caregiving supports local (Fletcher et al., 2021; Surgenor et al., 2022) and international evidence (Berglund et al., 2015; Calvó-Perxas et al., 2018; Cribben et al., 2021; Robinson et al., 2020; Romero-Martínez & Moya-Albiol, 2017). Qualitative comments contextualised these findings through an emphasis on the overwhelming sense of responsibility for being the person keeping their loved one alive, the pervasiveness and relentlessness of the role, the negative impact on the relationship with the loved one with the ED and the wider family, and the need to constantly juggle competing demands.

The increasing rates of EDs (Haripersad et al., 2021) along with a shortage of specialist clinicians and often long waits for treatment means that increasingly, caregivers are required to support their loved one with the ED whilst waiting for care and that more caregivers are required to do this than ever before. Given the high burden of caregiving, better support for caregivers is needed to help reduce this burden, both during recovery and after remission is achieved.

Consistent with the findings in our study that caregiver burden decreased between being a current caregiver and previously caregiving, research has shown that ED symptom impact decreases over the course of recovery (Dennhag et al., 2021). This may be representative of seeing signs of recovery buffering the impact of burden and offering hope. However, this may mean that for caregivers of people with long-lasting or multi-problematic presentations, where initial treatments have been ineffective, hopelessness and a sense of pervasiveness may lead to worsening mental health.

Finally, the endorsement of symptoms related to traumatic stress is consistent with previous findings (Hazell et al., 2014; Irish et al., 2024; Timko et al., 2023; Wufong et al., 2019), albeit at a lesser level than other studies (Timko et al., 2023). Given that the traumatic stress symptoms have been associated with mood and coping during caregiving, this provides further support for the need to intervene and support caregivers to reduce the long-term burden experienced. Similarly, self-blame as often evidenced by guilt, is associated with PTSD (Irish et al., 2024), thereby highlighting the importance of early education and awareness of messages conveyed to parents about the multifactorial aetiological factors of EDs.

Limitations

The non-completion rate for the study was high, and whilst this could be due to the length of the study, many participants stopped before completing basic demographic information, unaware of the survey’s length. It may be that the people who did not complete the survey in the early phases were curious about the survey but less motivated to complete the study. Additionally, the significant burden of caregiving, as highlighted in this study, may have meant that the demands of caregiving made it difficult to complete the survey, or that only those with the capacity could engage. Thus, there are several unknowns about the reasons for non-completion. It is unclear what impact this would have on the results. Given this, results should be interpreted with a degree of caution.

Recruitment occurred through caregiver networks, such as the EDCS network, which would imply that caregivers were likely engaging in some level of support seeking. It is possible that being engaged with a support network indicates a recognition of the need for support, and that a willingness to seek support may be protective. Conversely, it could be that people who are not engaged in support are experiencing less caregiving burden and thus have not sought support. Given this, future research should use broader recruitment methods, ideally using a prospective design.

The discussion of traumatic stress symptoms is limited by a lack of validated measures to assess these symptoms. Whilst the study could have used a validated measure for PTSD, we were aware this would have added more items to an already long survey. Thus, we can only suggest that participants have indications of traumatic stress symptoms, but not PTSD. Diagnostic indications would also be complicated by the ongoing debate in the literature about what constitutes an event that meets the criteria for PTSD and if caregiving for a loved one who is acutely unwell meets these criteria.

Future Research

Whilst this research has emphasised the negative impact of caring for people with EDs, it would be useful to consider a strengths-based approach and examine the factors that are protective in maintaining wellbeing during caregiving. Ideally, such a study would be prospective in nature and follow people through treatment, offering greater insight into which caregivers can best buffer the effects of their role and why. This could include an analysis of clinical indicators, factors related to individual with ED, caregiver factors and treatment factors to explore the contribution of each of these to wellbeing, but what has the greatest impact throughout different stages of the therapeutic process.

Research has shown that interventions for caregivers are moderately effective at reducing caregiver distress (Hibbs et al., 2015) and may improve recovery outcomes for the person with the ED (Hannah et al., 2022). However, it is unclear how beneficial these interventions are for caregivers who may be from minority groups including indigenous populations and those who are neurodiverse. Future research could explore how to integrate caregiver support programmes into standard care and the subsequent impacts, how to adapt these programmes for caregivers who might be poorly served by standard care, and how such programmes impact outcomes for both caregivers and people with EDs.

Conclusion

The profound negative impact on caregiver wellbeing can persist after recovery from the ED has been obtained. The anxiety experienced, particularly during caregiving, can continue to occur in the form of long-term post-traumatic stress symptoms. Better support needs to be provided for caregivers during the treatment process to potentially reduce this psychological morbidity.

Practice Implications

Caregiving burden is linked to difficulty accessing support, balancing competing demands, financial stress, and the perceived relentlessness of the role of caregiving.

Caregivers of people with eating disorders report a high level of distress that can persist after the person with the ED is considered to be recovered.

Approximately one third of caregivers experience traumatic stress-like symptoms related to their caregiving experience.

Caregivers should be supported throughout the recovery process in order to provide support and intervention to reduce caregiver distress.

Reflective Statement

LD is a health and clinical psychologist who has worked with EDs in private practice, at a tertiary specialty service, and secondary mental health services. For the past two years, she has also been a caregiver to a child with deteriorating health.

RS is a counselling psychologist intern who has observed the impact of EDs on two of her friends and their caregivers. Previously, RS was a police officer for the NZ Police. As part of this role, she worked with multiple individuals experiencing mental distress.

SR is a dedicated advocate and ambassador for eating disorders and multi-sector system reform, driven by her personal lived experience and caregiving journey in New Zealand and Australia. Her work emphasises essential carer and family inclusion, and she is a co-founder of EDCS.

KM (Ngāti Porou) is a lived experience caregiver. Having navigated the complexities of supporting a loved one with an eating disorder in both NZ and Australia, now advocates for positive sector change, increased peer support, and greater inclusion of caregivers and whānau in their vital role supporting recovery. This advocacy is amplified through the lived experience voice.

JL is an academic psychologist who has undertaken research understanding the needs of caregivers and documenting the impacts associated with caregiving for family members experiencing various conditions.

References

- Anastasiadou, D., Medina-Pradas, C., Sepulveda, A. R., & Treasure, J. (2014). A systematic review of family caregiving in eating disorders. Eating behaviors, 15(3), 464-477.

- Berglund, E., Lytsy, P., & Westerling, R. (2015). Health and wellbeing in informal caregivers and non-caregivers: a comparative cross-sectional study of the Swedish general population. Health and quality of life outcomes, 13, 1-11.

- Calvó-Perxas, L., Vilalta-Franch, J., Litwin, H., Turró-Garriga, O., Mira, P., & Garre-Olmo, J. (2018). What seems to matter in public policy and the health of informal caregivers? A cross-sectional study in 12 European countries. PloS one, 13(3), e0194232.

- Clark, M. T. R., Manuel, J., Lacey, C., Pitama, S., Cunningham, R., & Jordan, J. (2023). Reimagining eating disorder spaces: a qualitative study exploring Māori experiences of accessing treatment for eating disorders in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 22.

- Coomber, K., & King, R. M. (2013). An investigation of the psychometric properties of the Eating Disorder Symptom Impact Scale within an Australian sample. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65(2), 71-78. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J., Cayley, C., Lovibond, P. F., Wilson, P. H., & Hartley, C. (2011). Percentile norms and accompanying interval estimates from an Australian general adult population sample for self-report mood scales (BAI, BDI, CRSD, CES-D, DASS, DASS-21, STAI-X, STAI-Y, SRDS, and SRAS). Australian Psychologist, 46(1), 3-14.

- Cribben, H., Macdonald, P., Treasure, J., Cini, E., Nicholls, D., Batchelor, R., & Kan, C. (2021). The experiential perspectives of parents caring for a loved one with a restrictive eating disorder in the UK. BJPsych Open, 7(6), e192, Article e192. [CrossRef]

- Dennhag, I., Henje, E., & Nilsson, K. (2021). Parental caregiver burden and recovery of adolescent anorexia nervosa after multi-family therapy. Eating Disorders, 29(5), 463-479. [CrossRef]

- Duclos, J., Piva, G., Riquin, É., Lalanne, C., Meilleur, D., Blondin, S., Berthoz, S., Duclos, J., Mattar, L., Roux, H., Thiébaud, M.-R., Vibert, S., Hubert, T., Courty, A., Ringuenet, D., Benoit, J.-P., Blanchet, C., Moro, M.-R., Bignami, L.,…Group, E. (2023). Caregivers in anorexia nervosa: is grief underlying parental burden? Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 28(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, L., Trip, H., Lawson, R., Wilson, N., & Jordan, J. (2021). Life is different now–impacts of eating disorders on Carers in New Zealand: a qualitative study. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 1-12.

- Fox, J. R., Dean, M., & Whittlesea, A. (2017). The experience of caring for or living with an individual with an eating disorder: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 24(1), 103-125.

- Hannah, L., Cross, M., Baily, H., Grimwade, K., Clarke, T., & Allan, S. M. (2021). A systematic review of the impact of carer interventions on outcomes for patients with eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 1-10.

- Hannah, L., Cross, M., Baily, H., Grimwade, K., Clarke, T., & Allan, S. M. (2022). A systematic review of the impact of carer interventions on outcomes for patients with eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 27(6), 1953-1962. [CrossRef]

- Haripersad, Y. V., Kannegiesser-Bailey, M., Morton, K., Skeldon, S., Shipton, N., Edwards, K., Newton, R., Newell, A., Stevenson, P. G., & Martin, A. C. (2021). Outbreak of anorexia nervosa admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of disease in childhood, 106(3), e15-e15.

- Hazell, P., Woolrich, R., & Horsch, A. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder in mothers of individuals with anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. Advances in Eating Disorders: Theory, Research and Practice, 2(1), 31-41.

- Hibbs, R., Rhind, C., Leppanen, J., & Treasure, J. (2015). Interventions for caregivers of someone with an eating disorder: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(4), 349-361. [CrossRef]

- Irish, M., Adams, J., & Cooper, M. (2024). Investigating self-blame and trauma symptoms in parents of young people with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 32(1), 80-89. [CrossRef]

- Kulshrestha, V., & Shahid, S. M. (2022). Barriers and drivers in mental health services in New Zealand: current status and future direction. Global Health Promotion, 29(4), 83-86.

- Kumar, A., Himmerich, H., Keeler, J. L., & Treasure, J. (2024). A systematic scoping review of carer accommodation in eating disorders. Journal of Eating Disorders, 12(1), 143. [CrossRef]

- Lefkovits, A. M., Pepin, G., Phillipou, A., Giles, S., Rowan, J., & Krug, I. (2024). Striving to support the supporters: A mixed methods evaluation of the strive support groups for caregivers of individuals with an eating disorder. European Eating Disorders Review, 32(5), 880-897.

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). Depression anxiety and stress scales. Behaviour Research and Therapy.

- Medvedev, O. N. (2023). Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21) in international contexts. In International Handbook of Behavioral Health Assessment (pp. 1-15). Springer.

- Nemcikova, M., Katreniakova, Z., & Nagyova, I. (2023). Social support, positive caregiving experience, and caregiver burden in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia [Original Research]. Frontiers in Public Health, 11. [CrossRef]

- Padierna, A., Martín, J., Aguirre, U., González, N., Munoz, P., & Quintana, J. M. (2013). Burden of caregiving amongst family caregivers of patients with eating disorders. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 48, 151-161.

- Quinn, C., & Toms, G. (2019). Influence of positive aspects of dementia caregiving on caregivers’ well-being: A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 59(5), e584-e596.

- Rhind, C., Salerno, L., Hibbs, R., Micali, N., Schmidt, U., Gowers, S., Macdonald, P., Goddard, E., Todd, G., & Tchanturia, K. (2016). The objective and subjective caregiving burden and caregiving behaviours of parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 24(4), 310-319.

- Rienecke, R. D., & Le Grange, D. (2022). The five tenets of family-based treatment for adolescent eating disorders. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 60. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, I., Stoyel, H., & Robinson, P. (2020). “If she had broken her leg she would not have waited in agony for 9 months”: Caregiver's experiences of eating disorder treatment. European Eating Disorders Review, 28(6), 750-765.

- Romero-Martínez, Á., & Moya-Albiol, L. (2017). Stress-induced endocrine and immune dysfunctions in caregivers of people with eating disorders. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14(12), 1560.

- Sepulveda, A. R., Kyriacou, O., & Treasure, J. (2009). Development and validation of the accommodation and enabling scale for eating disorders (AESED) for caregivers in eating disorders. BMC Health Services Research, 9, 1-13.

- Sepulveda, A. R., Whitney, J., Hankins, M., & Treasure, J. (2008). Development and validation of an Eating Disorders Symptom Impact Scale (EDSIS) for carers of people with eating disorders. Health and quality of life outcomes, 6, 1-9.

- Sinclair, R., Landon, J., Rowland, S., MacDougall, K., & Donkin, L. (2025). “The ED has cost us our savings, home, career - but recovery is worth it.”: Support Needs of Adult Caregivers of People With a Diagnosed or Suspected Eating Disorder in New Zealand. A Mixed Methods Study. Submitted to Eating Disorders, In preparation.

- Stefanini, M. C., Troiani, M. R., Caselli, M., Dirindelli, P., Lucarelli, S., Caini, S., & Martinetti, M. G. (2019). Living with someone with an eating disorder: factors affecting the caregivers’ burden. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 24(6), 1209-1214. [CrossRef]

- Surgenor, L. J., Dhakal, S., Watterson, R., Lim, B., Kennedy, M., Bulik, C., Wilson, N., Keelan, K., Lawson, R., & Jordan, J. (2022). Psychosocial and financial impacts for carers of those with eating disorders in New Zealand. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 37.

- Timko, C. A., Dennis, N. J., Mears, C., Rodriguez, D., Fitzpatrick, K. K., & Peebles, R. (2023). Post-traumatic stress symptoms in parents of adolescents hospitalized with Anorexia nervosa. Eating Disorders, 31(3), 212-224. [CrossRef]

- Treasure, J., & Nazar, B. P. (2016). Interventions for the carers of patients with eating disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18, 1-7.

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & health sciences, 15(3), 398-405.

- Whitney, J., Haigh, R., Weinman, J., & Treasure, J. (2007). Caring for people with eating disorders: Factors associated with psychological distress and negative caregiving appraisals in carers of people with eating disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46(4), 413-428.

- Wufong, E., Rhodes, P., & Conti, J. (2019). “We don’t really know what else we can do”: Parent experiences when adolescent distress persists after the Maudsley and family-based therapies for anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders, 7, 1-18.

- Zabala, M. J., Macdonald, P., & Treasure, J. (2009). Appraisal of caregiving burden, expressed emotion and psychological distress in families of people with eating disorders: a systematic review. European Eating Disorders Review: The Professional Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 17(5), 338-349.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).