1. Introduction

BIM (Building Information Modeling) is increasingly being used in risk analysis [

1,

2]. It is used as a risk management tool in the development process [

3] and is also used to generate basic data and act as a platform for BIM-based tools to perform further risk analysis [

4]. The issue of simulating crisis situations and human behavior during them is increasingly being addressed in scientific literature [

5]. Simulations are created using various methods, one of which is Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) [

6]. The idea behind agent-based modeling is to use so-called agents, a virtual environment, and agent-agent and agent-environment relationships to model various phenomena and processes occurring in space under study. Agents are autonomous units or objects with specific properties, activities and goals. The environment, in turn, constitutes the space in which agents interact. The environment can be geometric, networked or drawn from data relating to reality [

7].

Two types of software are commonly used for evacuation simulation and disaster prevention: commercial software (e.g., STEPS, Pathfinder) and open-source software (e.g., NetLogo, Repast) [

8]. The BIM models used in the simulations provide a representation of the building geometry and provide non-graphical information [

9], such as the properties of building materials [

10]. In the NetLogo environment, it is not possible to directly import BIM models [

11], and the issue of BIM data conversion for agent-based simulations in NetLogo remains almost untouched in the available literature [

12]. Thus, a research gap was identified, and to fill it, an experiment was undertaken involving the translation of data along the BIM-GIS-NetLogo line. The purpose of this publication was to present a new approach to converting BIM data for use in NetLogo and to build a fire simulation model illustrating the capabilities of the proposed method.

2. Materials and Methods

Autodesk Revit 2025.2 software was used to build the BIM model. Autodesk Revit is one of two popular BIM tools [

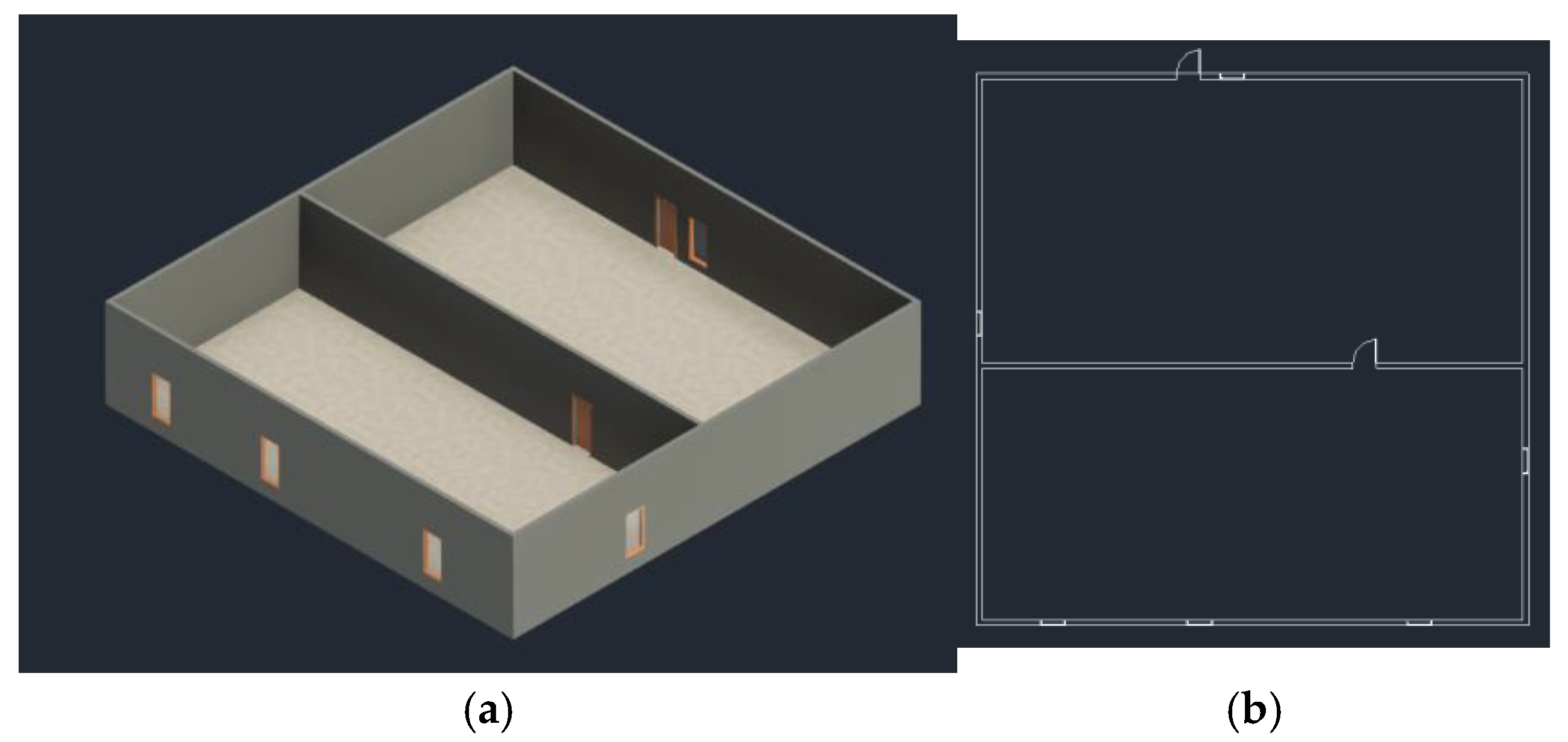

13]. For the purposes of the publication, a room model with a partition wall inside the building was created (

Figure 1). The model includes external walls, door and window openings, and a partition wall.

Figure 1.

3D view and ground floor of the BIM model. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 1.

3D view and ground floor of the BIM model. Source: own elaboration.

BIM typically uses a specific software ecosystem and requires expertise in conversion, translation, and programming [

14]. In scientific literature, this is referred to as tools ecology [

15]. The fire and human evacuation simulation model was developed in the NetLogo 6.4.0 environment. The program does not support files in non-text format, excluding some extensions. Instead, the application allows loading GIS (Geographic Information System) data, which allows the use of raster data in ESRI ASCII Grid (.asc, .grd) format and vector data in Shapefile (.shp) or GeoJSON (.geojson) format.

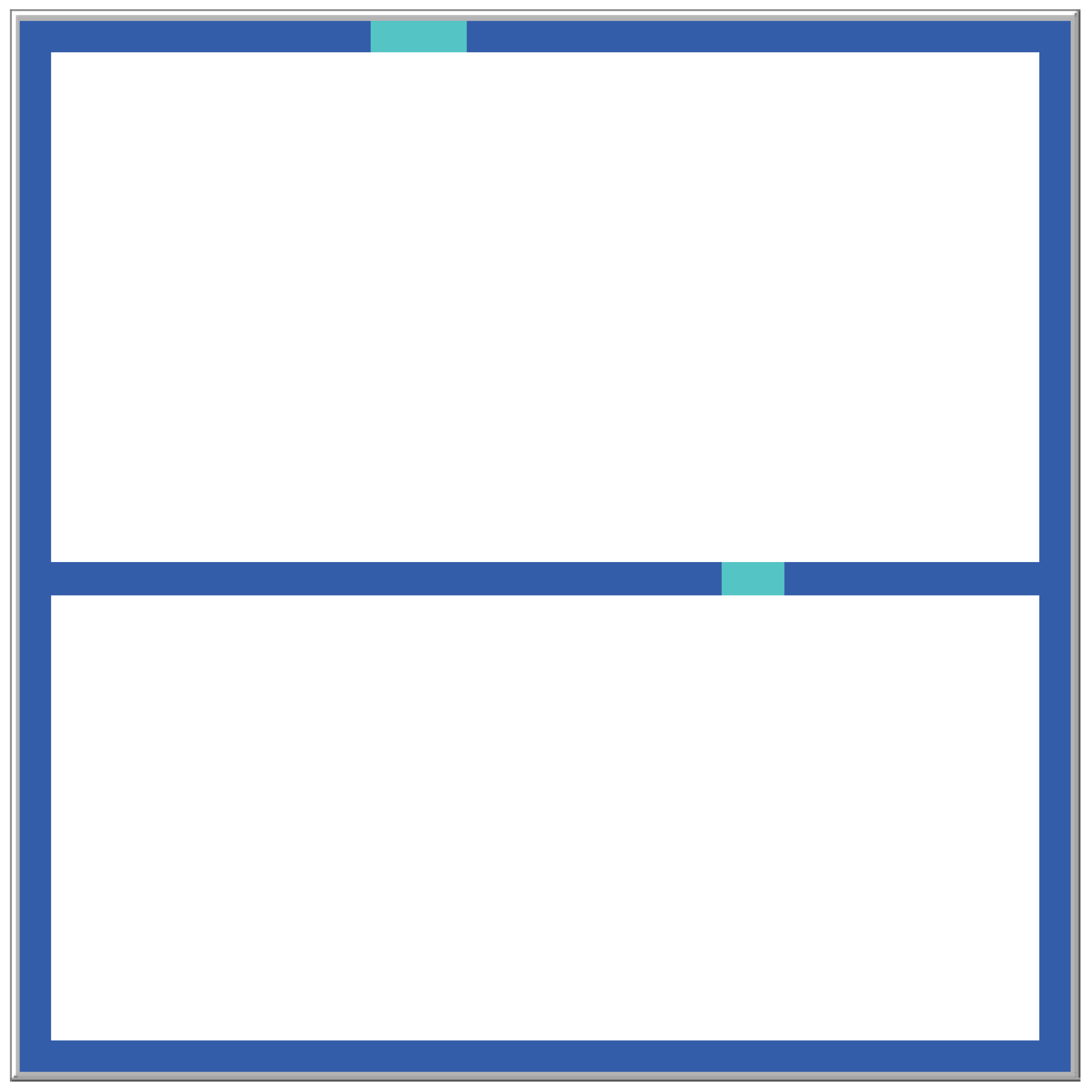

To obtain data from the BIM model in Shapefile format, a two-step conversion was used (

Figure 2). ESRI ArcGIS Pro 3.1.1 software was used to convert the data from Drawing Exchange Format (.dxf) to Shapefile format. The final product of the conversions were 2 files containing geometric representation of wall outlines and doorways. The developed algorithm created the walls and doors of the room based on the received Shapefiles (

Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Diagram showing data conversion, source: own development. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 2.

Diagram showing data conversion, source: own development. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 3.

Room created in NetLogo. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 3.

Room created in NetLogo. Source: own elaboration.

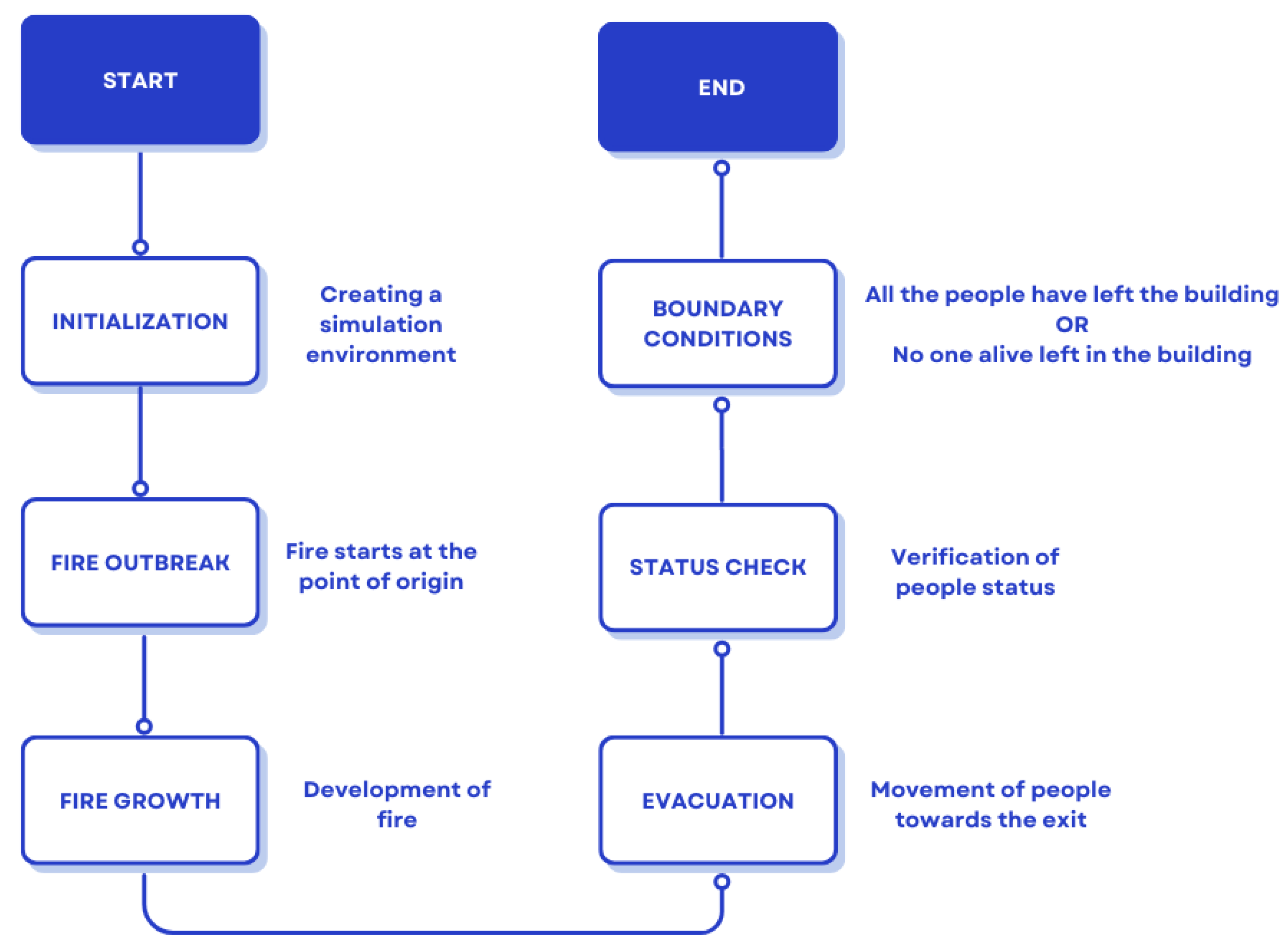

Initialization of the model results in the creation of the simulation environment, thus the room is created, people (agents) appear, and the location of the fire is defined. Calling the repetitive "go" command results in the start of the simulation, the fire begins to spread, and the people head toward the exit. In each iteration, the status of the people is verified; the final boundary conditions of the simulation are the statuses: all people have left the building or no one alive remains in the building. When either of these is met, the simulation ends, regardless of the status of the fire (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Block diagram of the simulation model operation. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 4.

Block diagram of the simulation model operation. Source: own elaboration.

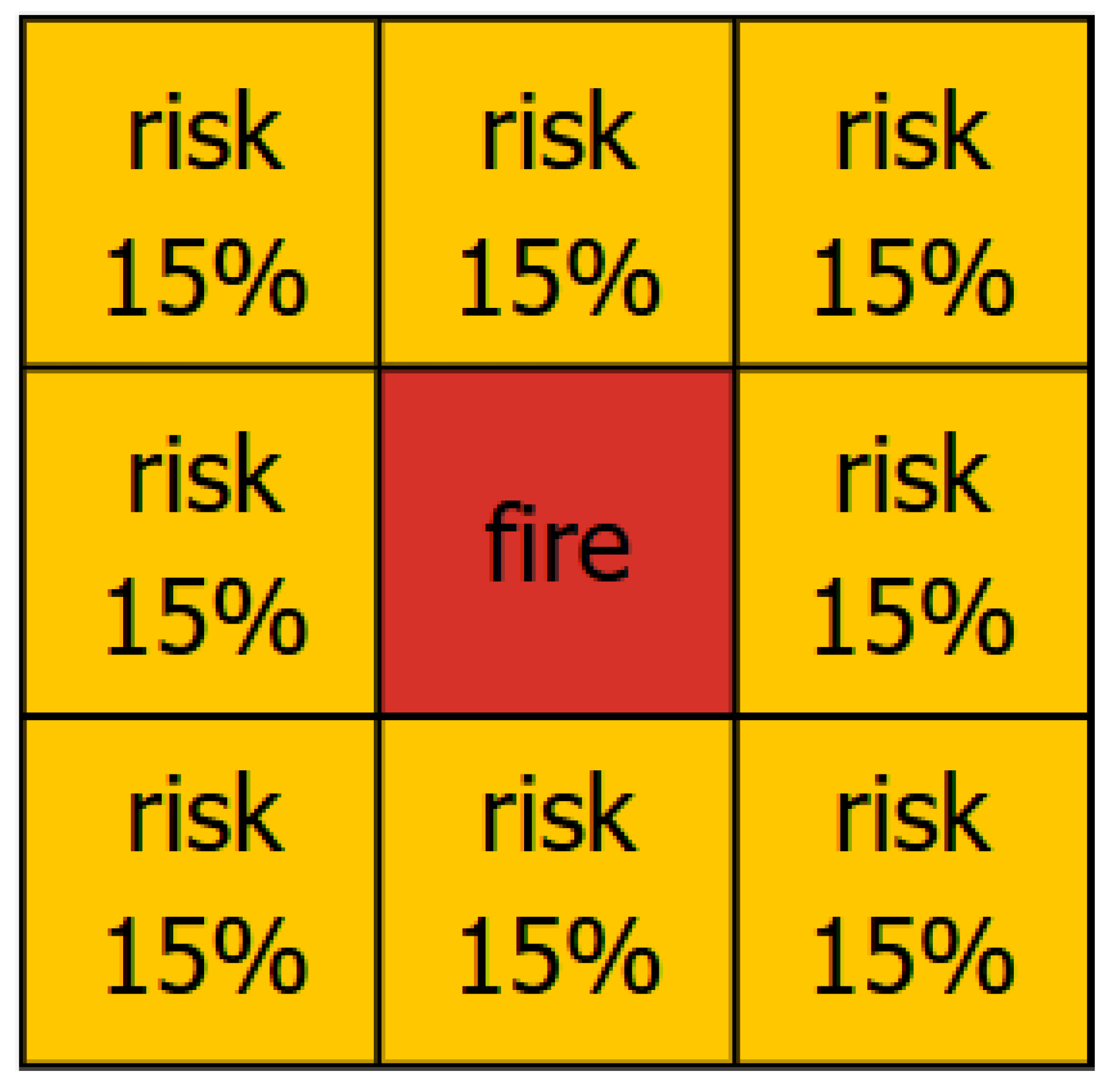

The model assumes the appearance of a fire source anywhere in the room. The fire spread method assigns a risk status to all fields adjacent to the fire source. Then, in each iteration of the simulation, there is a 15% chance of fire spreading from a field with fire status, to a field with risk status (

Figure 5). The percentage chance of fire spread is a parameter and can be freely modified from the simulation observer. This provides a wide range of possibilities for using the tool to create different scenarios, depending on the building materials used, interior design, or the function and layout of rooms in the building.

Figure 5.

Fire spread diagram. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 5.

Fire spread diagram. Source: own elaboration.

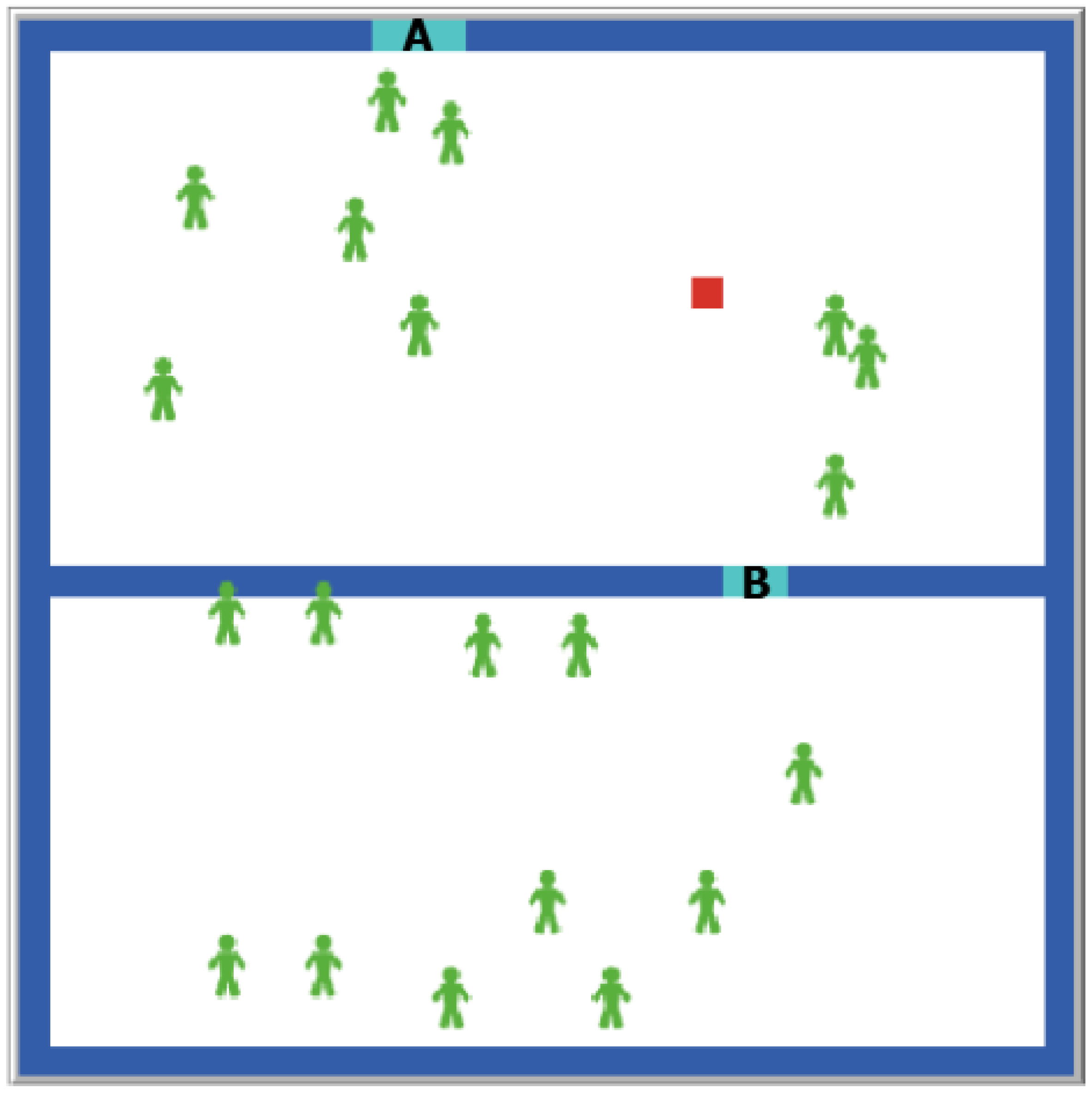

Each time the model is called, people are randomly placed in its space. When a fire breaks out, their goal becomes evacuation from the room, interpreted as reaching the outer door. People in the lower part of the room, initially have to go through the inner door, which becomes their intermediate goal (

Figure 6). The goal is thus dependent on the location of the person in the two-dimensional simulation space, his x and y coordinates. Considering the third dimension in CDF (Computational Fluid Dynamics) software, it is also possible to propose a numerical simulation of evacuation in smoke conditions, using the smoke distribution obtained from three-dimensional CFD [

16].

The developed simulation model is a sophisticated method for analyzing complex fire scenarios based on the probability of spreading hazards. Based on the input parameters, the variables included in the simulations include, among others, the number of people, the probability of individual objects igniting, the speed of movement of agents, the level of panic, the availability of alternative escape routes, the agents' familiarity with the area, and the density of smoke limiting visibility and affecting the dynamics of movement.

Figure 6.

Marking of evacuation targets, A - external doors, B - internal doors. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 6.

Marking of evacuation targets, A - external doors, B - internal doors. Source: own elaboration.

3. Results

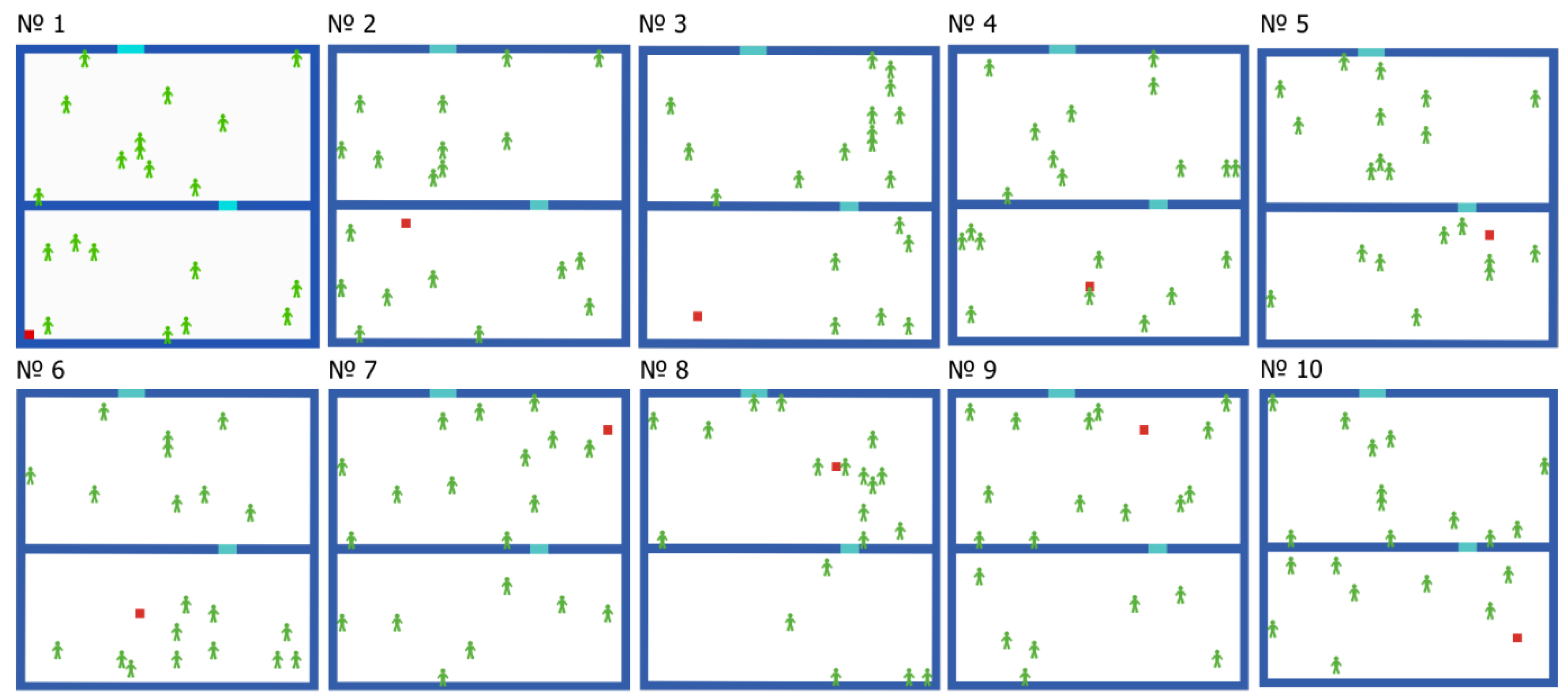

The simulation model created was run ten times, each time creating an environment that differed in the distribution of people and the location of the fire outbreak. Initially, there were 20 people in the room (

Figure 7). Both the number of iterations and the number, behavior, and distribution of people at each stage can be modified.

Figure 7.

Initial phases of 10 consecutive simulations. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 7.

Initial phases of 10 consecutive simulations. Source: own elaboration.

On average, 16 evacuated the building, and 4 people died. In 3 cases, all people managed to leave the building, even though the fire then occupied an average of 42.18% of the room area. In the worst case, No. 8, 12 people died, the site of the fire outbreak was near the gathering of people, on the way towards the exit (

Table 1). It should be emphasized here that the behavior of agents can be defined, as it will depend on the nature of the work in the building, the purpose or length of stay.

Table 1.

Simulation results. Source: own elaboration.

Table 1.

Simulation results. Source: own elaboration.

| No |

evacuated people |

dead people |

% of building on fire |

| 1 |

20 |

0 |

46.65% |

| 2 |

14 |

6 |

70.34% |

| 3 |

20 |

0 |

27.27% |

| 4 |

15 |

5 |

39.12% |

| 5 |

13 |

7 |

40.04% |

| 6 |

17 |

3 |

47.38% |

| 7 |

18 |

2 |

26.45% |

| 8 |

8 |

12 |

34.8% |

| 9 |

10 |

10 |

35.72% |

| 10 |

20 |

0 |

52.62% |

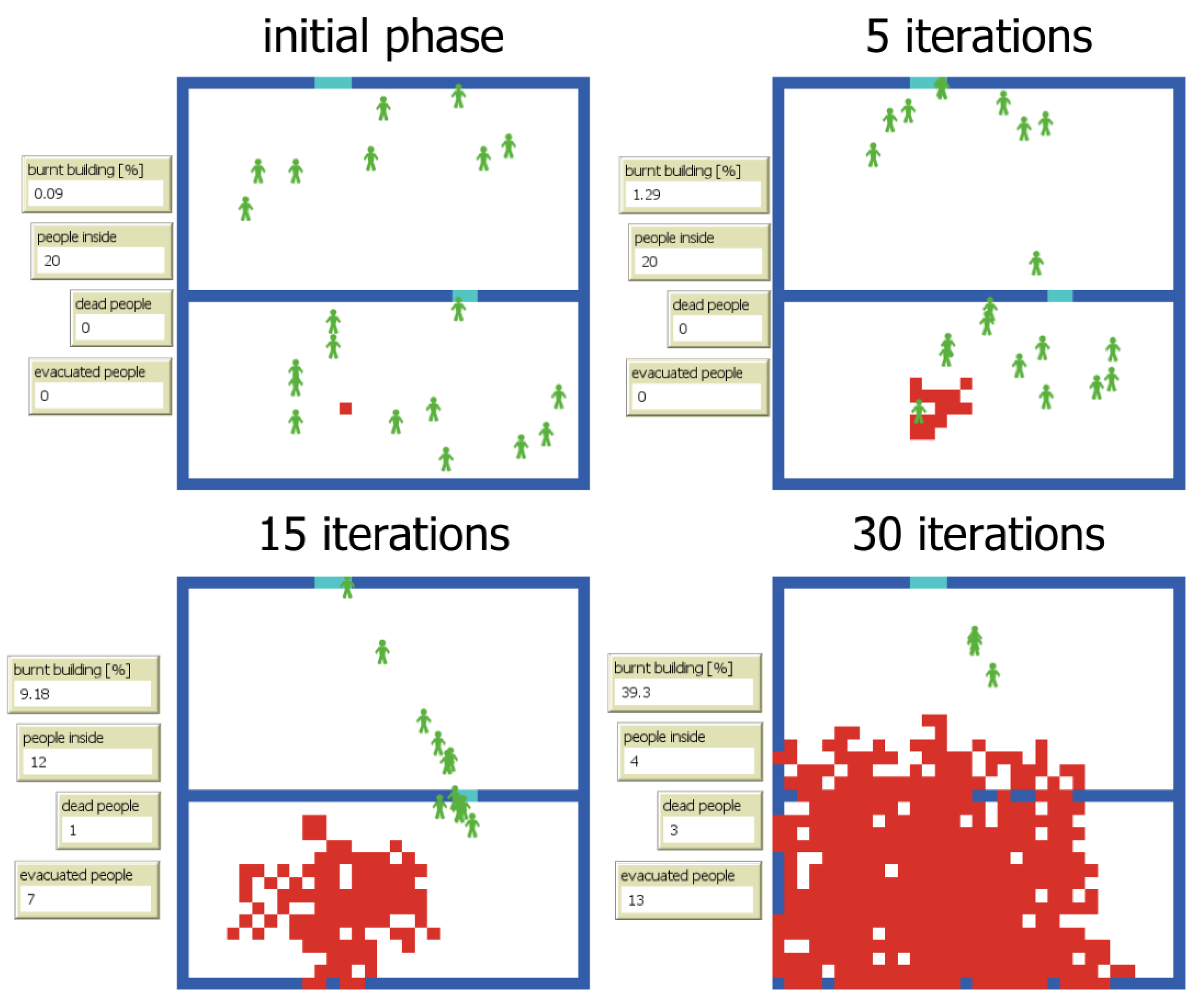

The spreading fire, symbolized by the red fields, occupies an increasing area of the room. As soon as the fire occupies the field where a person resides, a symbolic death occurs (

Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Results of an example simulation. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 8.

Results of an example simulation. Source: own elaboration.

The interior space of buildings is becoming increasingly complex and dynamic, making it difficult for internal staff to find their way around the layout of rooms for evacuation purposes. Emergency evacuation simulations can also be analyzed based on the information exchange mechanism to examine the impact of relevant information exchange factors on emergency evacuation in rooms. The results of previous studies show that even incomplete information exchange between evacuees can improve evacuation navigation, and the overall effectiveness of evacuation is better even if not all evacuees shared information [

17].

4. Discussion

The resulting simulation model makes it possible to analyze various fire scenarios, depending on the number of people, their location in the building, the location of the fire outbreak or the rate of fire spread. Further work and analysis could focus on expanding the model with elements that enrich its performance (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Possible directions for expanding the model, source: own development based on Sun & Turkan, 2020. Source: own elaboration.

Table 2.

Possible directions for expanding the model, source: own development based on Sun & Turkan, 2020. Source: own elaboration.

| Lp. |

Category |

Elements of |

| 1 |

Psychophysical factors |

Reaction time, resistance to stress, speed of movement, physical condition |

| 2 |

Fire behavior |

Physical and chemical properties of the combustion process |

| 3 |

Moving |

Improved movement model, taking into account visibility and other obstacles |

| 4 |

Properties of materials |

Flammability classes of building materials |

| 5 |

Additional factors |

Spread of smoke, reduced visibility |

| 6 |

Extinguishing agents and equipment |

Location of sprinklers, fire extinguishers, hydrants |

| 7 |

BIM model elements |

Windows, furniture |

Properly streamlined, the model could assist in planning evacuation activities, such as delineating escape routes and door placement. The model could also be used in creating fire safety manuals. BIM can support fire safety management in buildings, and a holistic BIM model should consist of four modules: evacuation assessment, escape route planning, safety education, and equipment maintenance [

18]. The construction industry is considered the fourth most dangerous industry in terms of fatalities. On construction sites, assessing evacuation risks in emergency situations is also a difficult task due to their constantly changing nature [

19]. Therefore, such analyses should be carried out during the design, implementation, and operation phases. Therefore, such analyses should be carried out at the design, implementation, and operation stages. Throughout the life cycle of a building, CDE (Common Data Environment) information systems are used to support the exchange and verification of information [

20]. Such platforms should also allow for a range of analyses and simulations to be carried out, such as evacuation simulations.

Fire modeling is a common practice in building fire safety analysis, but it is costly. The growing use of AI software such as Intelligent Fire Engineering Tool (IFETool) can speed up fire safety analysis and quickly identify design limitations [

21]. In recent years, the implementation of digital twin (DT) has gained significant attention across various industries. However, the fire safety management (FSM) sector has been relatively slow to adopt this technology compared to other major industries. The main barriers to DT implementation in FSM include a lack of knowledge about DT, initial costs, user acceptance, system integration difficulties, training costs, lack of expertise, development complexity, data management difficulties, and lack of trust in data security [

22].

5. Conclusions

To date, literature has lacked an effective way to integrate BIM and NetLogo. The proposed approach fills this research gap by developing a data conversion method that streamlines the integration of BIM and agent-based modeling technologies, which in the long run allows simulation tools to be applied at various stages of building operation, from the design phase, through the construction phase, to operation. Consideration of the issues raised in the discussion can significantly contribute to improving fire safety in buildings. The presented algorithm can be further developed. BIM integrates with other technologies towards the idea of Digital Twin. Without its achievement, it is difficult to imagine the ambitious goals of the circular economy being met. The methodology developed along the BIM-GIS-NetLogo line can be used in digital tools for designers and property managers. More and more applications enable evacuation simulations, and further research and development will support the development of these products. The growing trend of integrating artificial intelligence with BIM points to the automation, minimization, or elimination of manual work currently performed by humans. Machines will play an increasingly important role in shaping the idea of digital twins.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.B. and M.W.; methodology, A.S.B.; validation, A.S.B.; formal analysis, M.W.; resources, M.W.; data curation, M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.B. and M.W.; writing—review and editing, A.S.B. and M.W.; visualization, M.W.; supervision, A.S.B.; funding acquisition, A.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Thanks go to the Faculty of Geodesy and Cartography (Warsaw University of Technology) for their support during the research and development work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Algorithm code integrating data.

Figure A1.

Algorithm code integrating data.

References

- Park, E.S.; Seo, H.C. Risk Analysis for Earthquake-Damaged Buildings Using Point Cloud and BIM Data: A Case Study of the Daeseong Apartment Complex in Pohang, South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wenxian, L.; Weimin, F.; Ruiyin, Y. Fire risk assessment for building operation and maintenance based on BIM technology. Building and Environment 2021, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.; Yang, Y.; Tetteh, M.O. Building information modeling (BIM)-based modular integrated construction risk management–Critical survey and future needs. Computers in Industry 2020, 123, 103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Kiviniemi, A.; Jones, S.W. A review of risk management through BIM and BIM-related technologies. Safety Science 2017, 97, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arru, M.; Negre, E. (2017). People behaviors in crisis situations: Three modeling propositions. In 14th international conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (ISCRAM 2017) (pp. 139–149).

- Wagner, N.; Agrawal, V. An agent-based simulation system for concert venue crowd evacuation modeling in the presence of a fire disaster. Expert Systems with Applications 2014, 41, 2807–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilensky, U.; Rand, W. (2015). "An Introduction to Agent-Based Modeling." The MIT Press: London, England. 32 s.

- Hu, M.; Shi, Q. Comparative study of pedestrian simulation model and related software. Transp. Inf. Secur. 2009, 4, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski, A.S.; Maroń, M. Semantic Enrichment of Non-graphical Data of a BIM Model of a Public Building from the Perspective of the Facility Manager. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Turkan, Y. A BIM-based simulation framework for fire safety management and investigation of the critical factors affecting human evacuation performance. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2020, 44, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, M.; Pellegrini, L.; Accardo, D.; Sulis, E.; Tagliabue, L.C.; Di Giuda, G.M. People flow management in a healthcare facility throughcrowd simulation and agent-based modeling methods. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2023, 2600, 142007. [Google Scholar]

- Rozo, K.R.; Arellana, J.; Santander-Mercado, A.; Jubiz-Diaz, M. Modelling building emergency evacuation plans considering the dynamic behavior of pedestrians using agent-based simulation. Safety Science 2019, 113, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waas, L. Review of BIM-based software in architectural design: graphisoft archicad VS autodesk revit. Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Architecture 2022, 1, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, A.S. Experiential learning in the context of BIM. STEM Education 2023, 3, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, D. Design exploration supported by digital tool ecologies. Automation in Construction 2016, 72, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seike, M.; Kawabata, N.; Hasegawa, M. Quantitative assessment method for road tunnel fire safety: Development of an evacuation simulation method using CFD-derived smoke behavior. Safety science 2017, 94, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Wei, X.; Deng, Y.; Pan, H.; Deng, Q. Can information sharing among evacuees improve indoor emergency evacuation? An exploration study based on BIM and agent-based simulation. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 62, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.H.; Wang, W.C.; Wang, K.C.; Shih, S.Y. Y. Applying building information modeling to support fire safety management. Automation in construction 2015, 59, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, O.; Maghrebi, M. Risk of fire emergency evacuation in complex construction sites: Integration of 4D-BIM, social force modeling, and fire quantitative risk assessment. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2021, 50, 101378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, A.S.; Brożyna, J.; Litwin, J.; Rączka, W.; Szporanowicz, A. Use of the CDE environment in team collaboration in BIM. Informatyka, Automatyka, Pomiary w Gospodarce i Ochronie Środowiska 2023, 13, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Su, L.C.; Wu, X.; Xinyan, H. Artificial Intelligence tool for fire safety design (IFETool): Demonstration in large open spaces. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2022, 40, 102483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatared, M.; Liu, H.; Abudayyeh, O.; Hakim, O.; Sulaiman, M. Digital-twin-based fire safety management framework for smart buildings. Buildings 2023, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).