Introduction and Literature Review

This research explores the interactions between human investments and the natural mountain environment, including protected areas such as nature reserves, national parks, and landscape parks, with the aim of developing a sustainable mountain policy. According to the principles proposed by Rey (1997), the development of mountain regions must be integrated into a coherent European strategy that ensures the efficient coordination of sectoral policies, respects local and regional autonomy, and facilitates intercommunal and cross-border cooperation. The author proposes the creation of a flexible system that connects urban expansion areas through green corridors made up of settlements, mountain recreation areas, parks, forests, and agricultural land. This system aims to maintain a balance between urban development and the conservation of the natural environment, recognizing the identity and specificity of the mountain area, in line with the principles of sustainable development. To ensure sustainable economic development and job creation, it is essential to support and maintain small, non-polluting industries by improving mountain infrastructure and simplifying administrative and fiscal procedures. Initiatives in rural tourism and agrotourism should be promoted, considering the need to protect the natural and social mountain environment. Economic activities must be diversified to prevent the over-exploitation of mountain natural resources, thus maintaining ecological balance. Mountain areas must be equipped with infrastructure, equipment, and services that support a stable population, using technologies adapted to the mountain environment and environmentally friendly. In the energy sector, the utilization of local resources, such as hydroelectric potential, alternative and renewable energies, as well as improving heating systems through the efficient use of wood waste and other secondary resources, becomes essential for sustainable development. The main outcome of the research is the development of a model for development based on the configuration of river and road networks, which can be implemented in future regional plans, thus contributing to establishing a balance between human development and the protection of the mountain environment. This model has the potential to support the implementation of a coherent framework for the sustainable development of mountain regions, while simultaneously protecting natural landscapes and biodiversity. (Rey, 1997)

In recent decades, many European mountain regions have witnessed a profound process of economic restructuring, which has led to the decline of traditional heavy industry and the manufacturing sector. This change has had a significant impact on peripheral and rural regions, and the conversion of abandoned industrial lands has become a key issue for their sustainable development, even though the official recognition of this issue is still limited. The complex ecological, economic, and social challenges raised by the conversion of industrial lands in mountain areas, combined with the structural peculiarities of marginal contexts, require the development of a specific strategy, but adaptable to various mountain regions. The Alps, being the most developed mountain region in Europe, have the potential to become a laboratory for testing and implementing strategies for the conversion of abandoned industrial lands. Preliminary research results suggest that an effective and transferable transformation approach can be achieved through the application of a “landscape approach” based on structuralist planning principles. These principles can contribute to the development of a conversion strategy that transforms abandoned industrial lands into valuable territorial infrastructures capable of supporting the regeneration of mountain regions, rather than remaining vacant lands designated exclusively for conversion. (Modica & Weilacher, 2019).

In a polarized economic context, where the emergence of successful economic clusters contrasts with the decline of traditional industrial activities, the conversion of abandoned industrial lands becomes a strategically essential issue both at local and regional levels, especially in mountain regions. However, in the alpine context, the transformation and reuse of these decommissioned industrial sites face additional challenges related to continuously changing economic conditions and the emerging new paradigms of territorial development. In this context, the long-term sustainability of mountain economies depends on the ability to overcome traditional mono-structural economic models through the innovative and integrated use of existing territorial capital. The concept of territorial capital – which includes biophysical factors, environmental conditions, and socio-cultural capacities of a territory – is essential in this process. It requires a shift in perception, where the natural and human resources of the region are valued for the purpose of creating a sustainable economic future. A productive use of abandoned industrial lands can include a wide range of programmatic options, from business parks and innovative business incubators to centers for cultural and artistic production, thus contributing to the diversification of mountain tourism through an expanded cultural offering. (Modica, 2022)

Some authors believe that in certain areas of the world, deindustrialization must be replaced by mountain tourism. Sustainability and the management of tourism’s impact on the mountain environment are key topics in this case. However, the pandemic period, such as SARS CoV-2 COVID-19, highlighted the vulnerabilities of the mountain tourism sector, amplifying the need for resilient and flexible strategies. In addition, the concept of the experience economy is discussed, where visitors seek not only basic services but also authentic and personalized experiences, performance management, dynamic pricing policies, and investment management, all contributing to the continued success of mountain resorts. (Solelhac, 2021)

In the alpine context, other researchers believe that the interactions between human investments and the natural forms of the mountain environment, such as nature reserves, national parks, and landscape parks, can solve the reindustrialization problem through creative industries. The model proposed by these researchers aims to integrate urban expansion into a natural framework by creating ecological belts composed of settlements, mountain recreation areas, parks, forests, and agricultural land. The central idea was to ensure the harmonious coexistence of different land functions while maintaining a balance between urban development and the protection of the mountain environment. This development model aims to avoid the fragmentation of the mountain landscape and promote urbanization that respects the ecological specificity of the region. (Zareba & Krzeminska, 2010)

Methodology

This study explores the role of industrial entrepreneurship in the context of mountain economies across Europe.

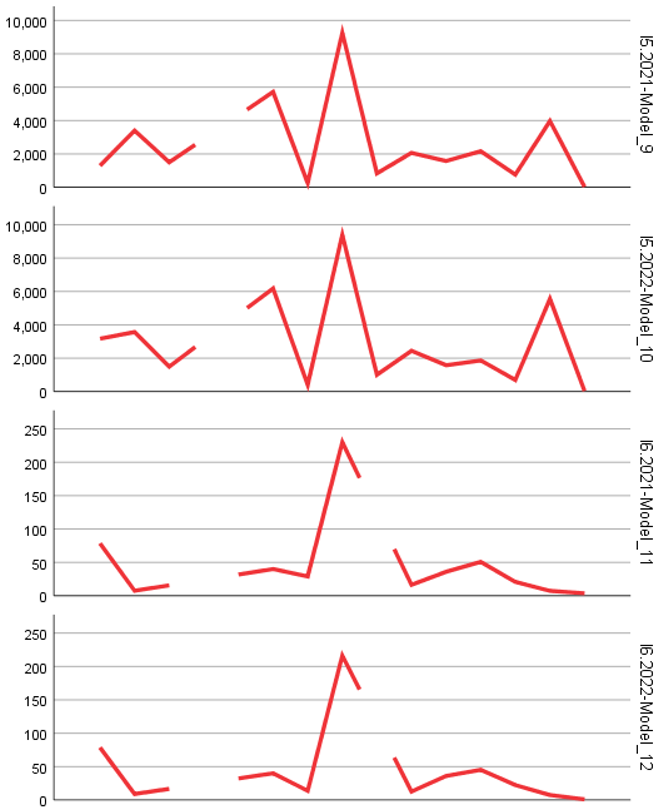

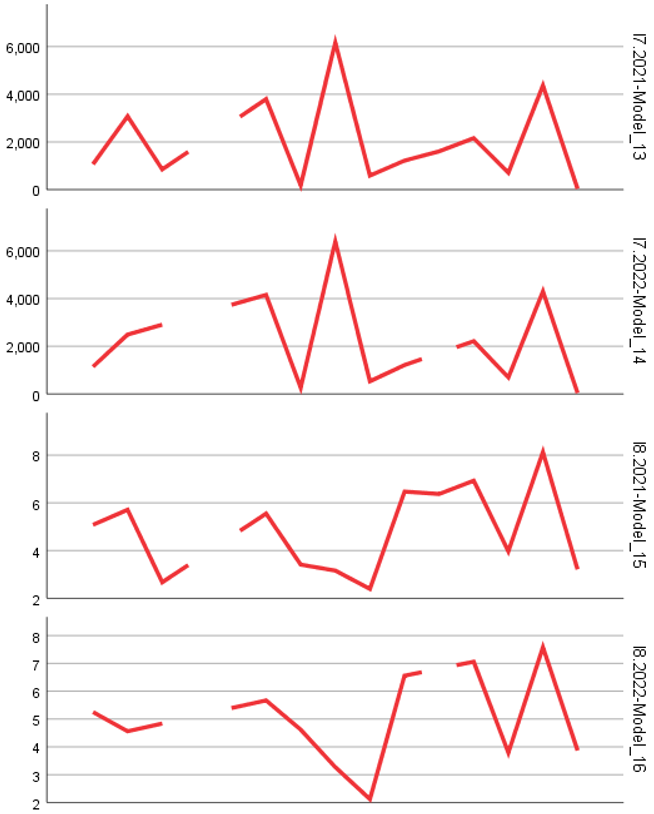

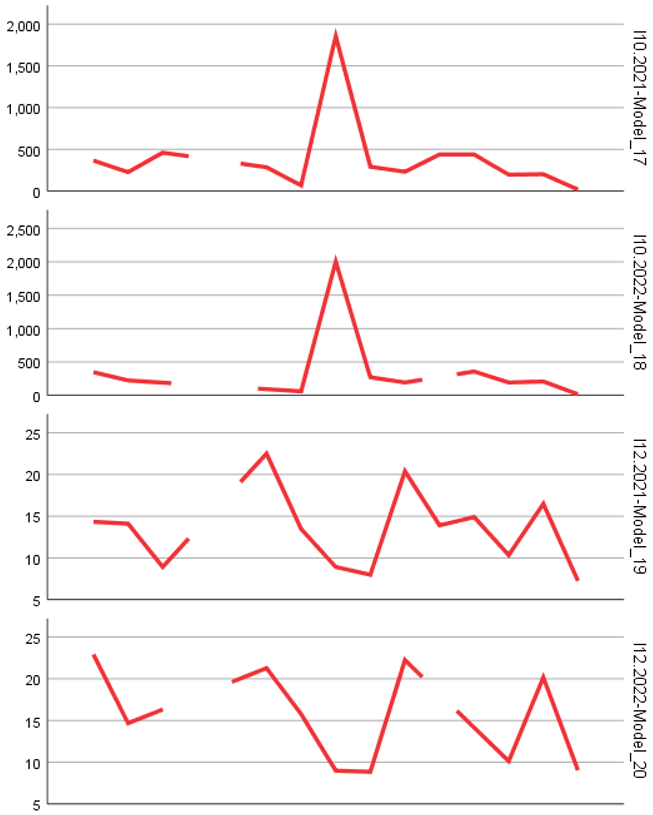

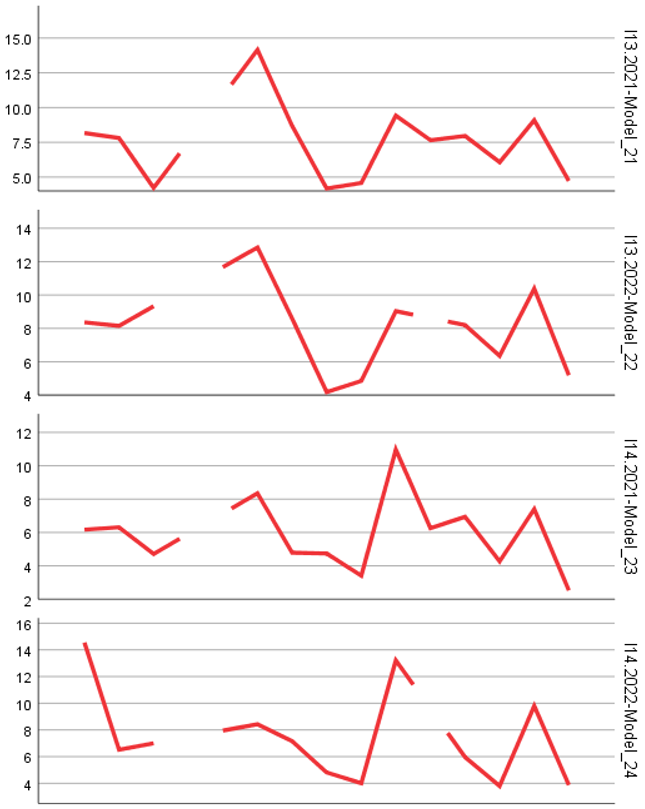

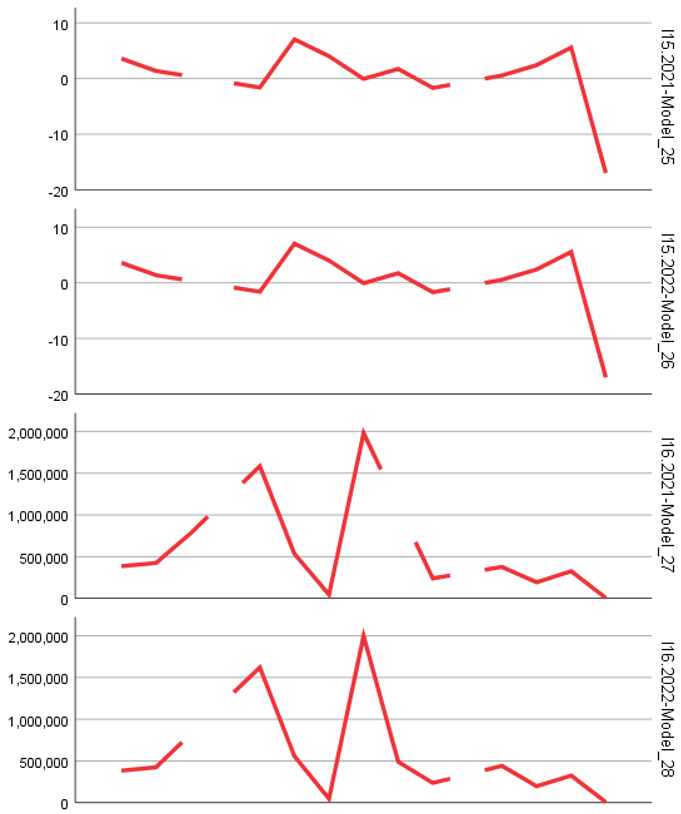

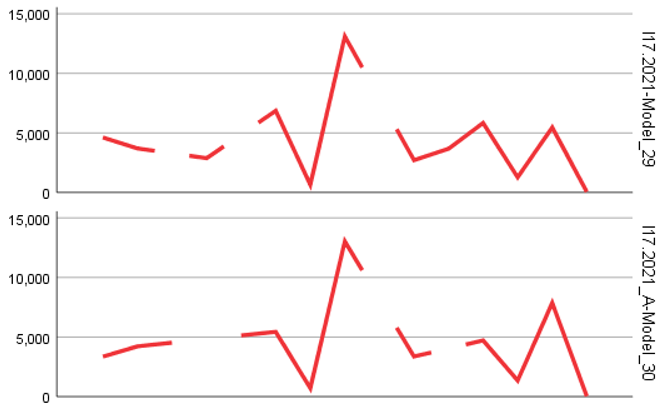

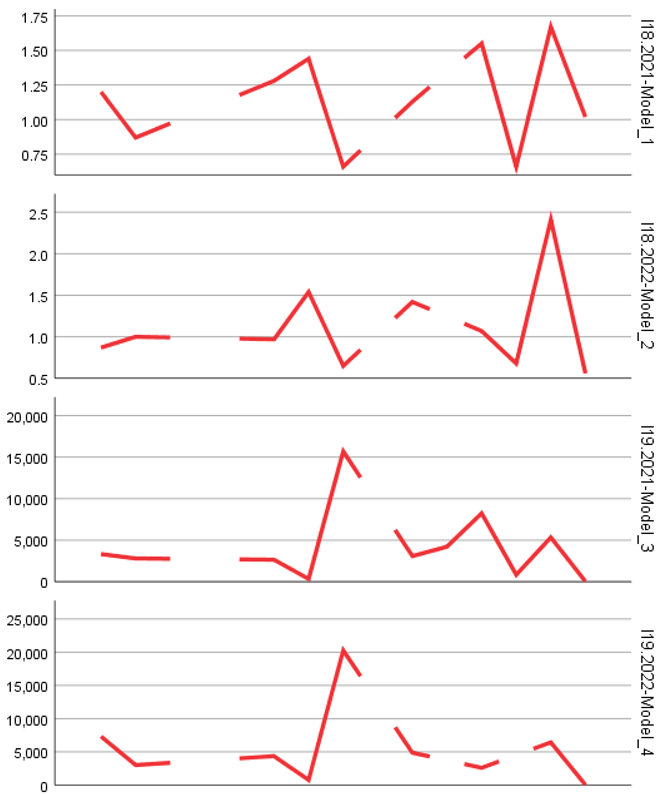

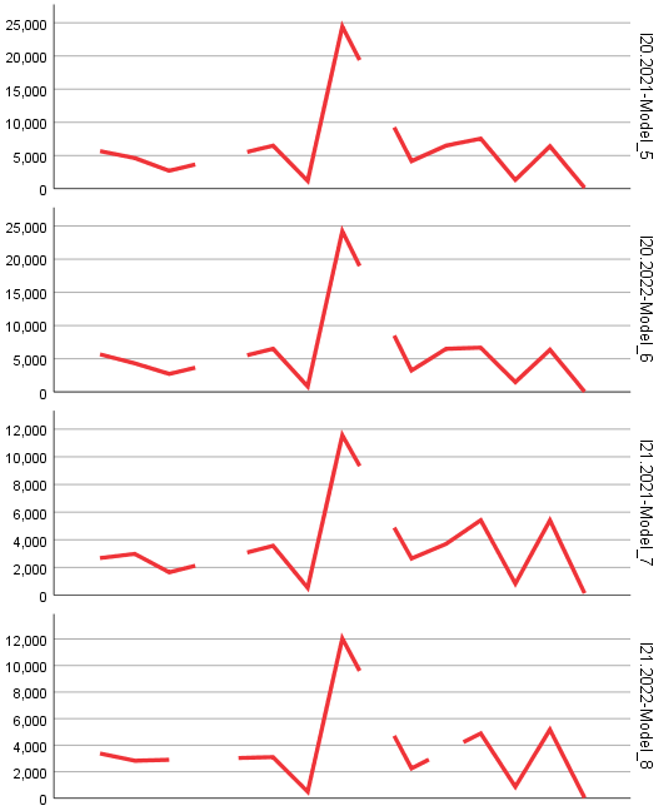

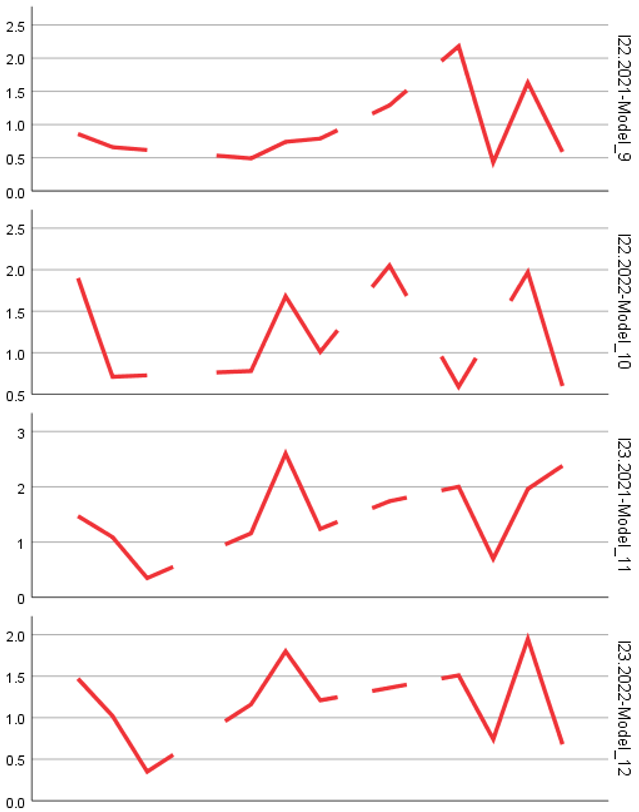

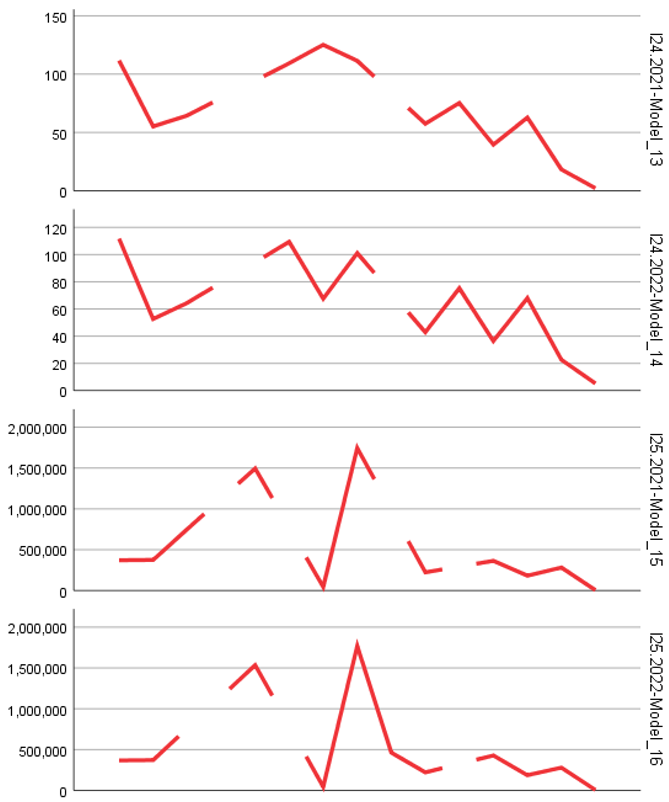

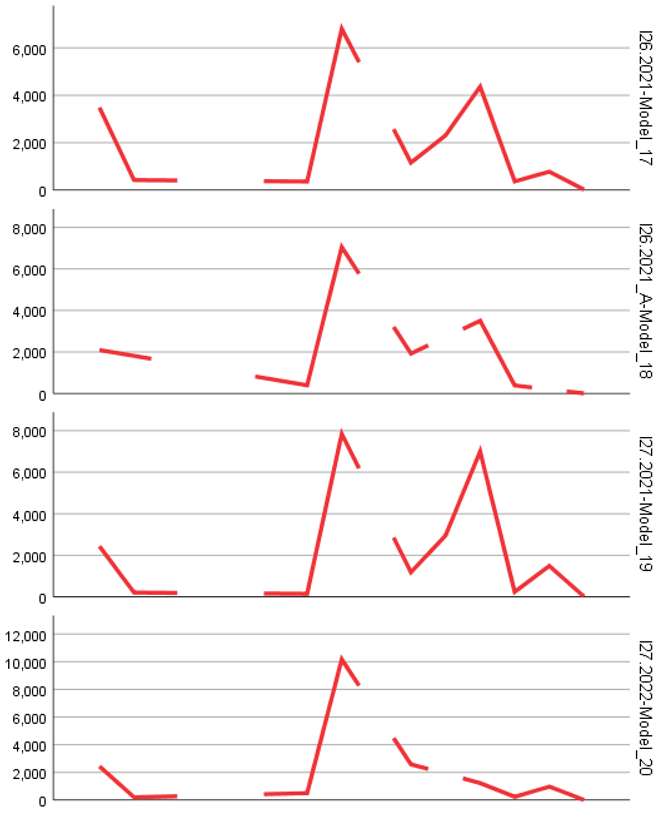

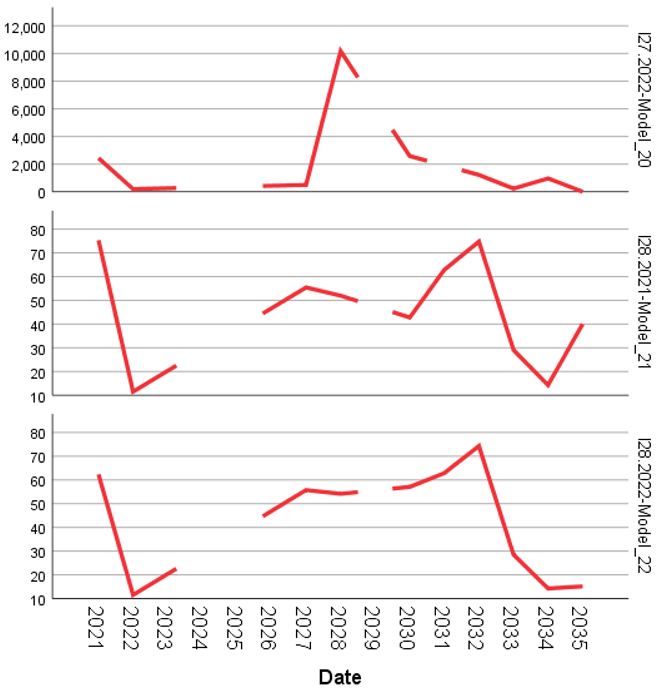

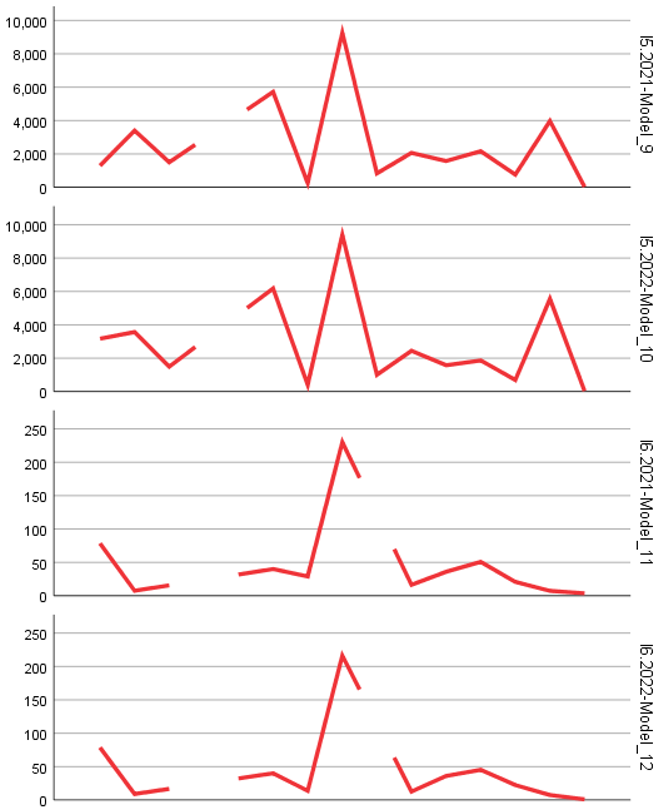

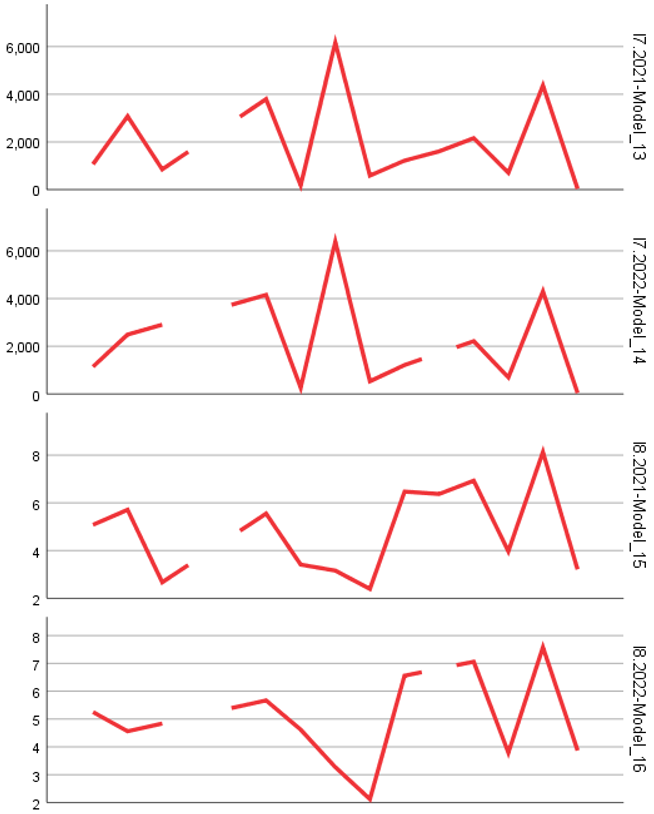

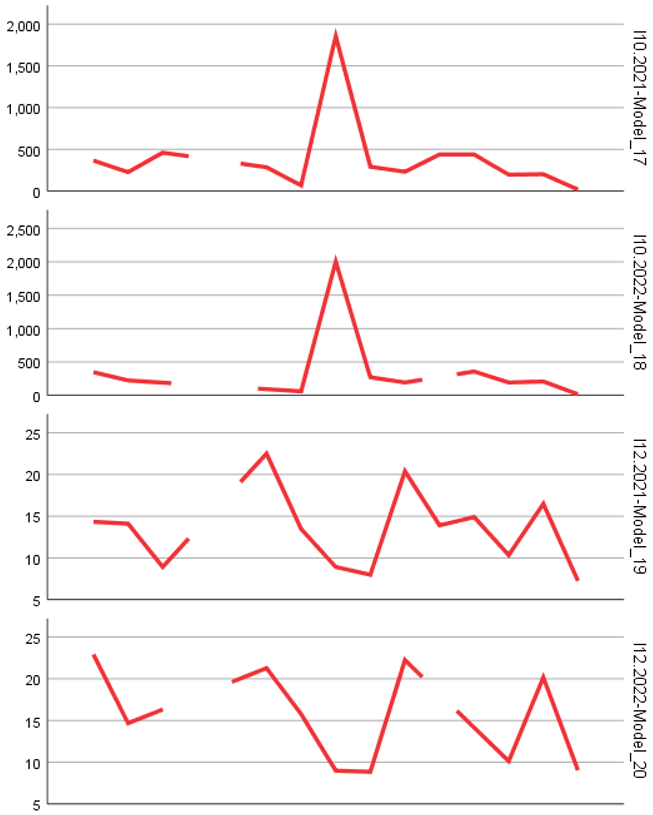

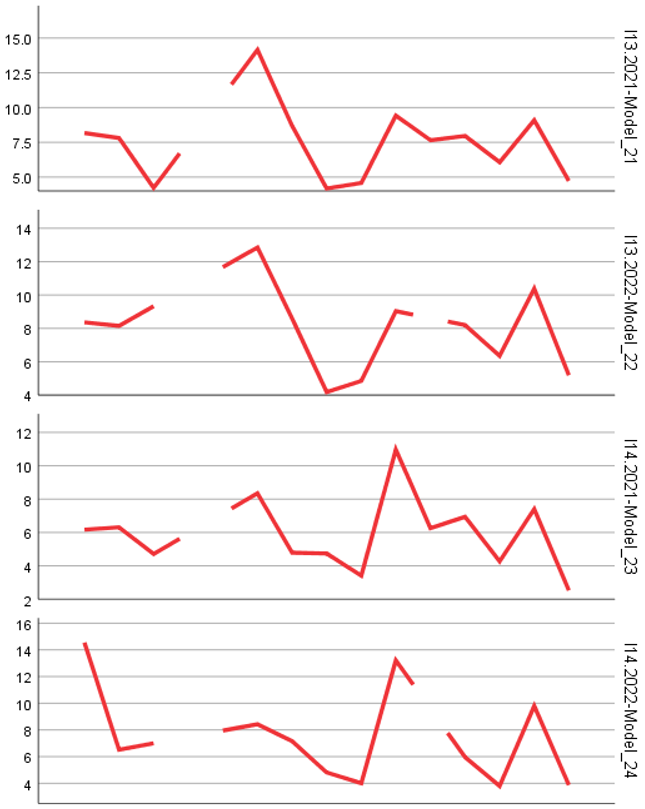

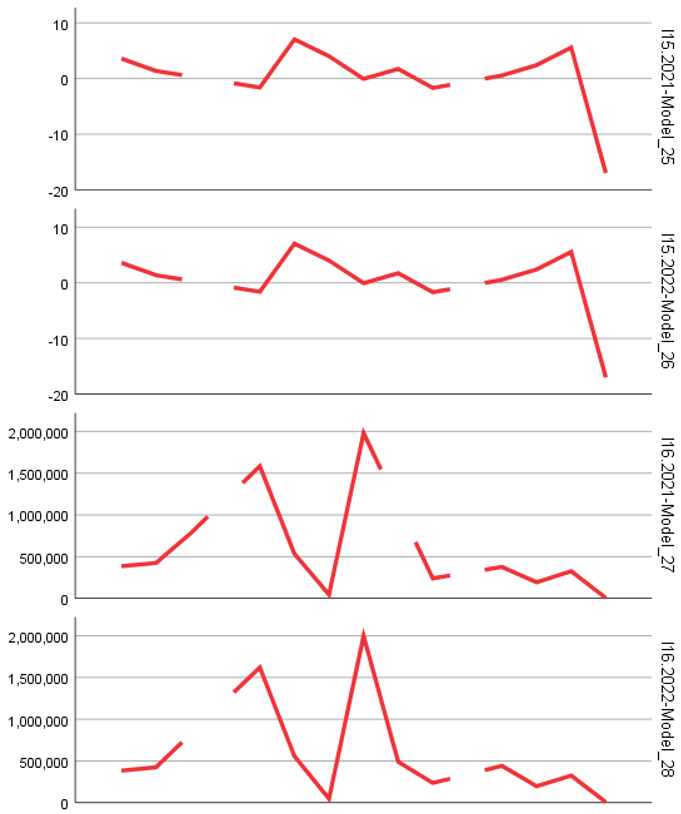

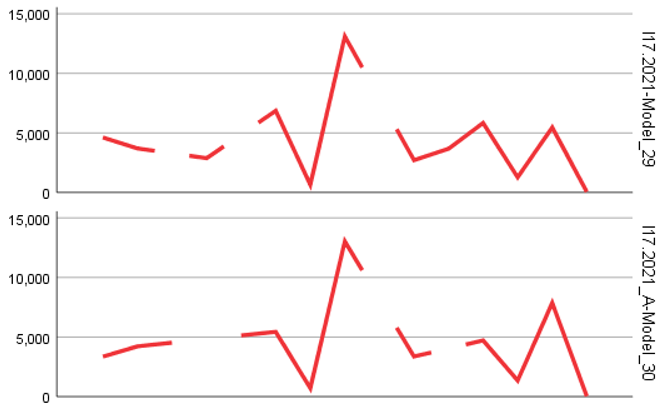

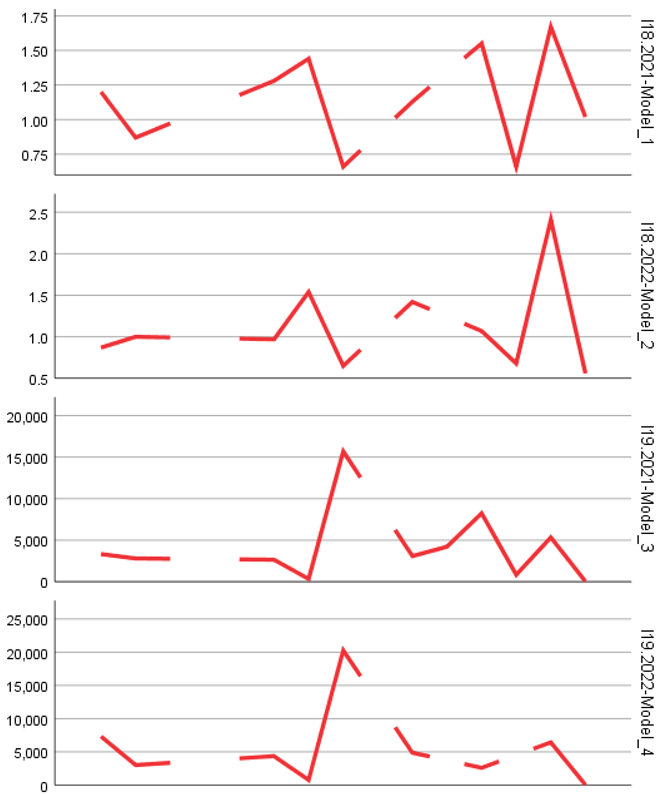

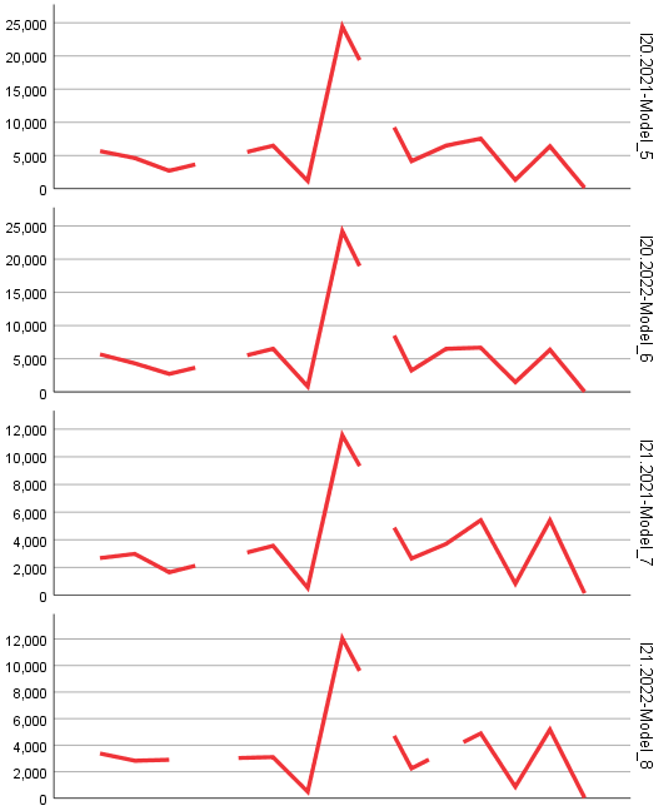

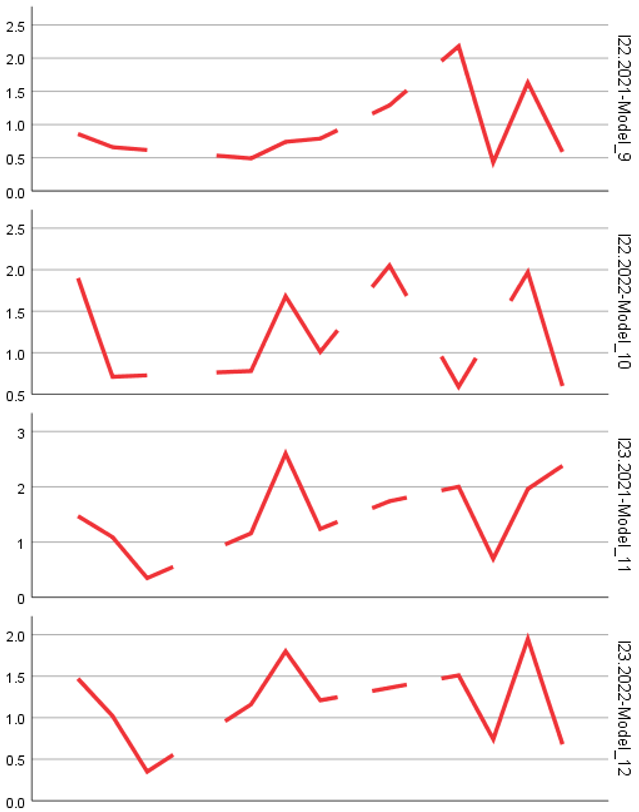

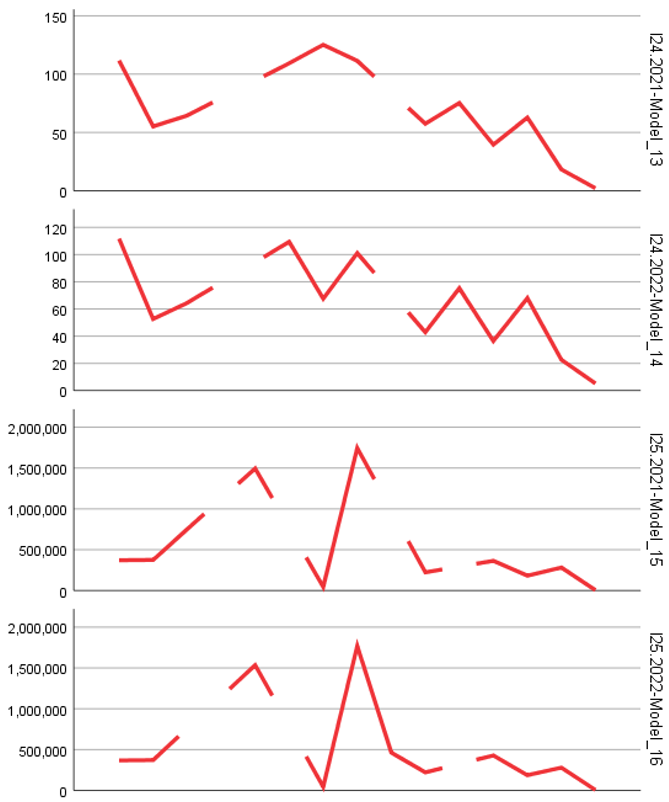

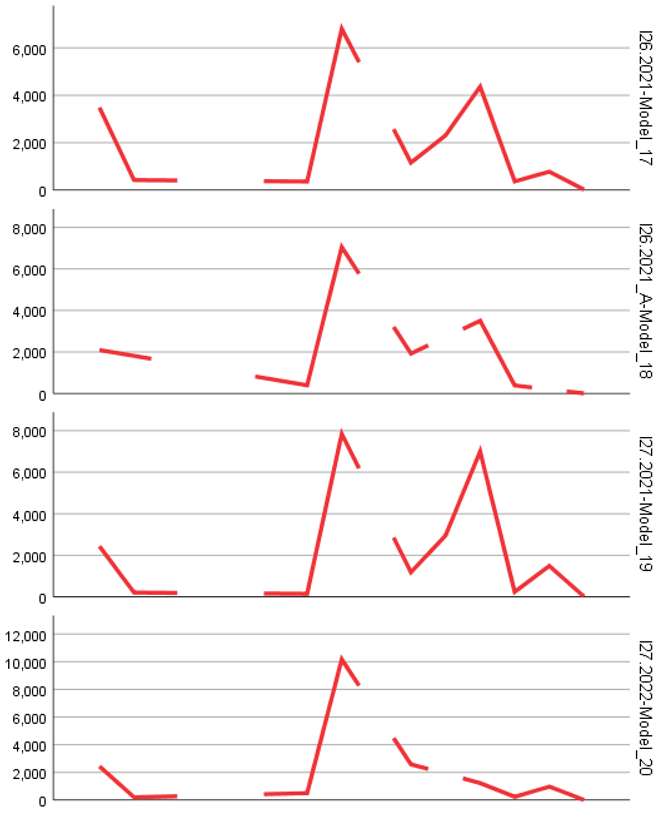

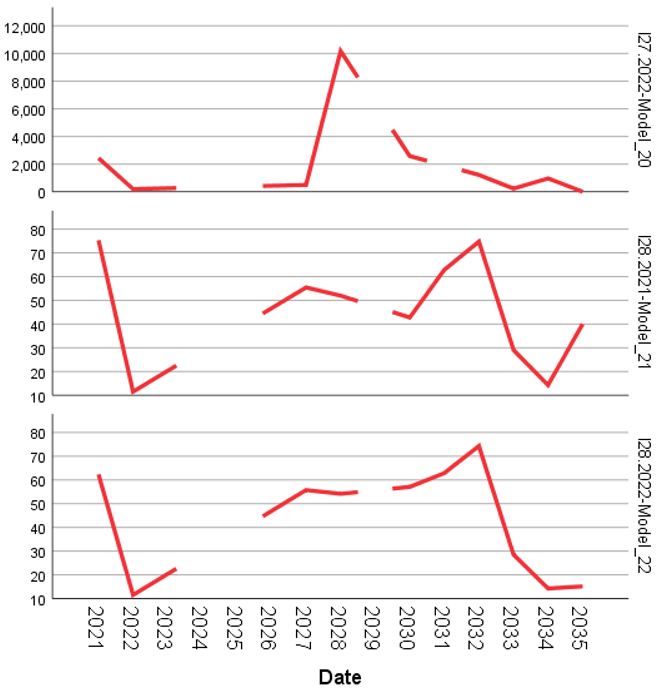

For the analysis presented in this article, data collected from official Eurostat sources concerning the mountain regions of Europe were used, including Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden. These data are structured into 28 indicators (I1-I28) for the analysis and forecast period 2021-2035, with each indicator being associated with distinct economic models (

Table 1) (detailed explanations of the indicators are available through the authors at the link

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14713867). For example, I1.2021 corresponds to Model_1, and I1.2022 corresponds to Model_2. Each indicator reflects the economic developments and trends within the entrepreneurial sector of the mountain industry in these countries.

The targeted indicators are specific to the mountain economy, including data on entrepreneurial activities in industrial sectors such as industrial production, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), infrastructure investments, and other aspects relevant to the sustainable development of the mountain industry.

Before applying statistical models, the data underwent a rigorous processing process:

- managing missing data: missing values were identified and addressed through imputation or elimination, depending on the nature and severity of data absences, to ensure consistency and accuracy in the analysis;

- detecting outliers: to ensure the integrity of the datasets, extreme values were detected and managed using appropriate statistical techniques (such as Z-scores and boxplot diagrams), and outliers were excluded from the final analysis;

- data normalization: the values of the indicators were normalized to make data from different sources and with varying measurement scales comparable. This step was crucial to ensure uniform analysis of data from various European countries.

The analysis was conducted using several statistical models, selected based on the typology of each indicator and the economic relationships being analyzed (

Table 2):

- time series forecasting models: for indicators that exhibit clear temporal dependencies, ARIMA (0,0,0) (AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average) models were used (with the exceptions described later). For example, Model_13 (I7.2021) was analyzed with ARIMA (1,0,0), a model suitable for forecasting economic indicators based on historical values from previous years;

- simple regression models: for indicators that had a linear relationship between variables, simple linear regression models were applied (for example, Model_43 for I24.2021) to explore economic links within the mountain industry, such as correlations between entrepreneurship and infrastructure development;

- Holt exponential smoothing method: for indicators exhibiting seasonal or long-term trends (such as for I24.2022 Model_44), the Holt model, an exponential smoothing technique, was applied, which is suitable for data that varies based on seasonality and economic trends.

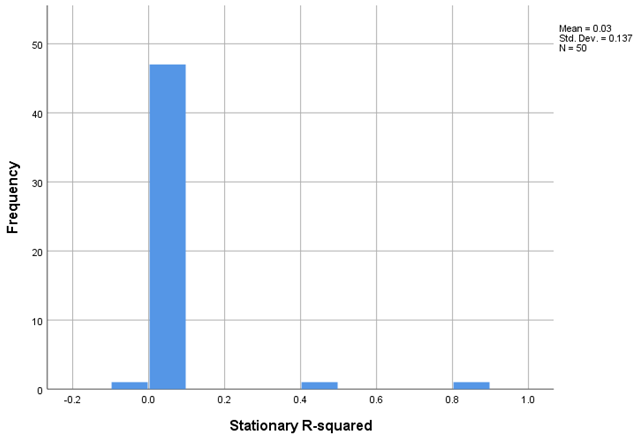

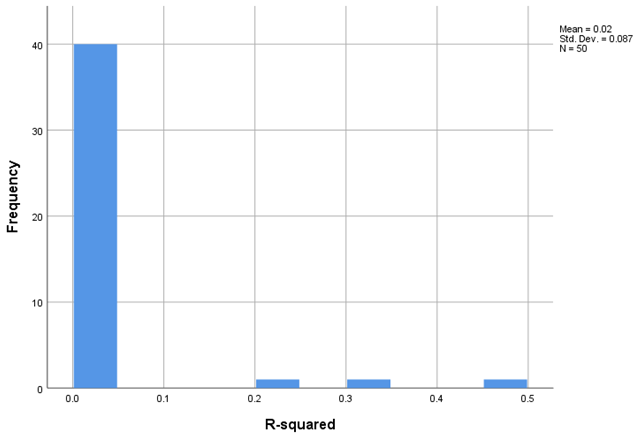

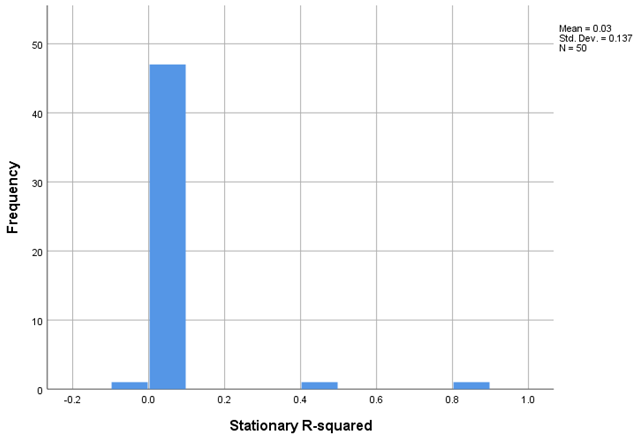

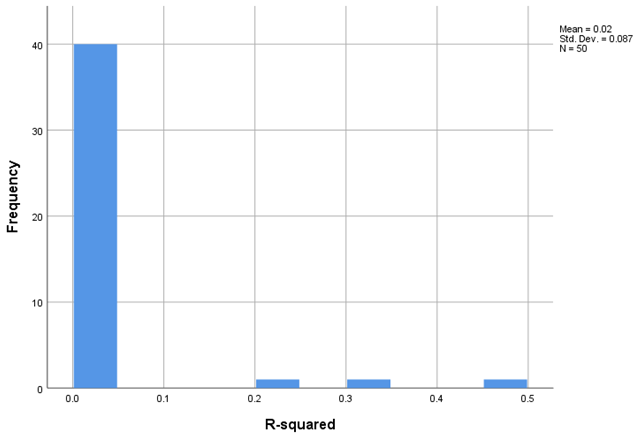

To assess the effectiveness and accuracy of the applied models, several adjustment statistics were calculated, allowing comparison of their performance (figures in methodology):

- R-squared (R2): this measures the proportion of variability in the dependent indicator explained by the applied models. Values closer to 1 indicate better explanation of economic variability within the mountain entrepreneurial sector;

- Stationary R-squared: a variant of R2, used for time series models, measuring the adjustment of the model to stationary data;

- RMSE (Root Mean Square Error): this measures the errors between observed and predicted values by the models. A lower RMSE indicates greater accuracy in economic forecasts;

- MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error): represents the average percentage error between the predicted and observed values, being an important accuracy indicator, with lower values indicating a more accurate forecast;

- MaxAPE (Maximum Absolute Percentage Error): measures the maximum absolute error in percentage form, useful for evaluating forecast extremes;

- MAE (Mean Absolute Error): the average of absolute differences between observed and predicted values, with lower values being desired;

- MaxAE (Maximum Absolute Error): represents the maximum absolute error between predicted and actual values, indicating possible large deviations in forecast models;

- Normalized BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion): used for comparing models, with smaller BIC values indicating a more efficient model.

The adjustment statistics and standard errors obtained for the entire range of models are as follows: - R-squared: Mean = 0.021, SE = 0.087; - Stationary R-squared: Mean = 0.025, SE = 0.137; - RMSE: Mean = 49025.819, SE = 159457.822; - MAPE: Mean = 597.758, SE = 1008.063; - MaxAPE: Mean = 5084.278, SE = 7647.604; - MAE: Mean = 35023.827, SE = 114180.199; - MaxAE: Mean = 110834.493, SE = 356946.139; - Normalized BIC: Mean = 10.676, SE = 8.711.

Results

This study presents the dynamics of mountain entrepreneurship in the European industry, using advanced statistical models to assess trends and forecast the development of the industrial sector. The results highlight both the growth potential of this economic niche and the specific challenges faced by businesses in mountain areas.

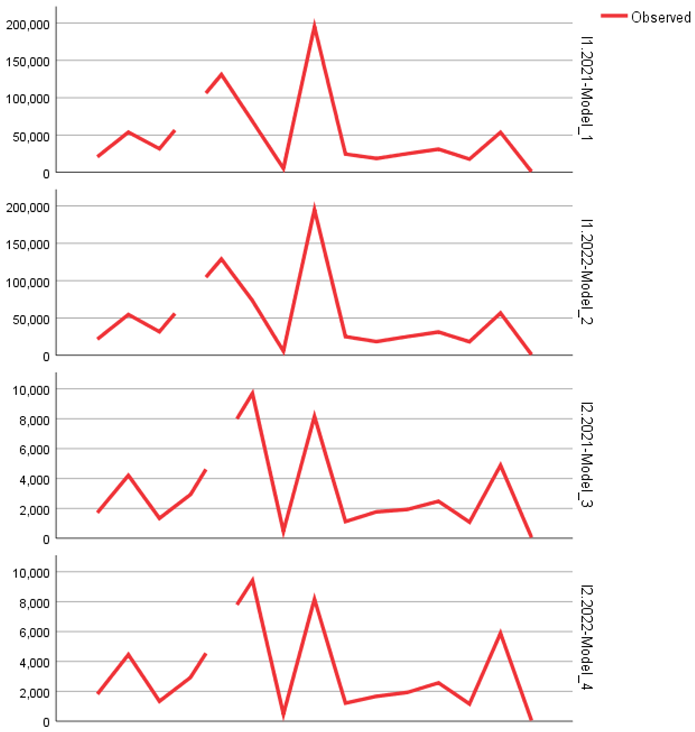

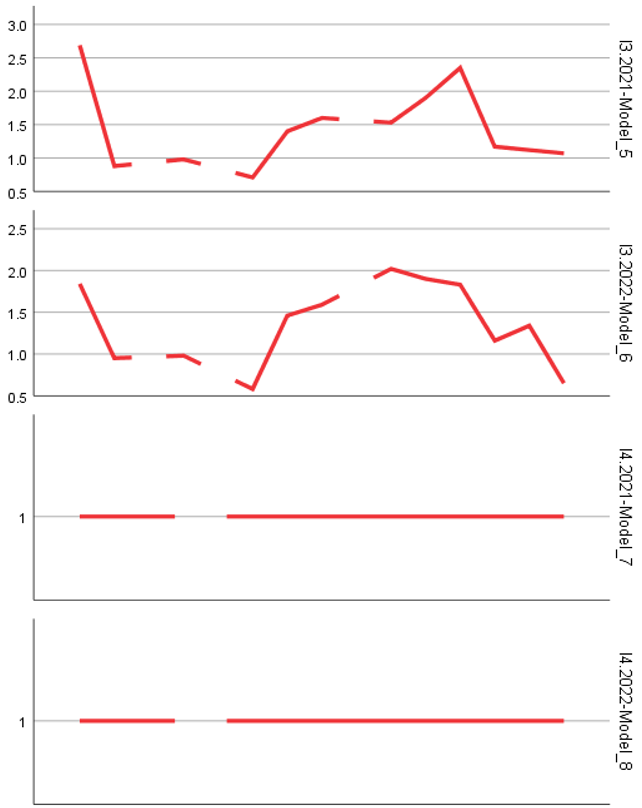

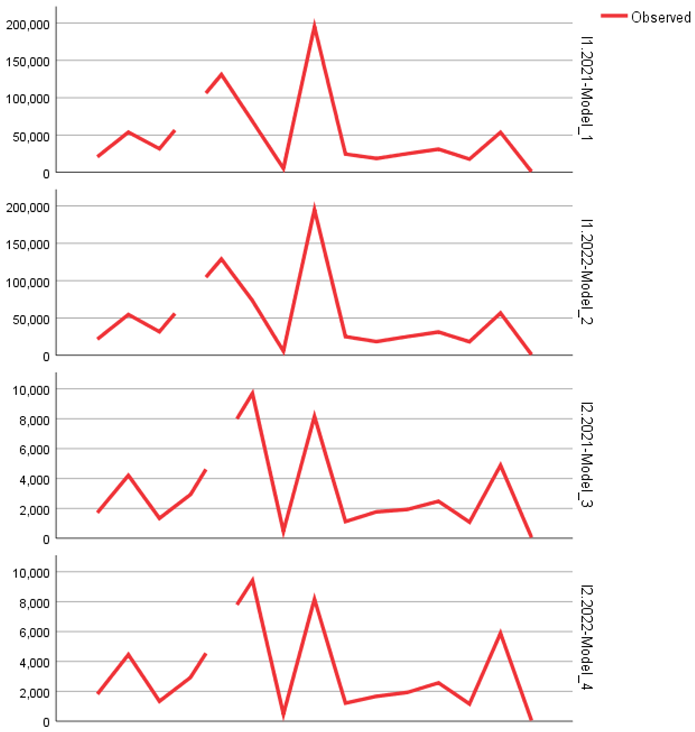

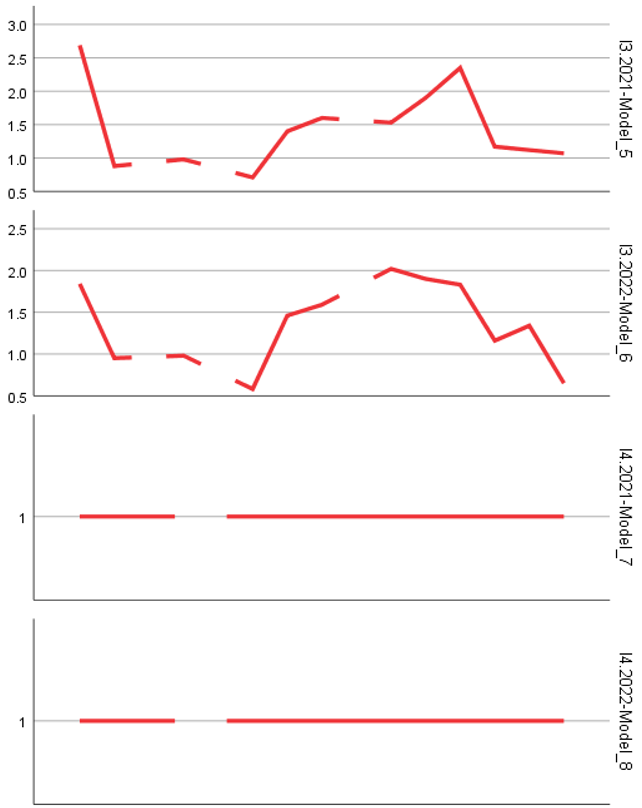

ARIMA models provide strong forecasts for the evolution of mountain businesses, capturing both seasonality and long-term trends, as shown in the following tables and figures:

- the models with the best accuracy (e.g., I3.2021-Model_5, I3.2022-Model_6) exhibited low errors (RMSE under 0.6, MAPE ~35-40%), indicating good adaptation to the small fluctuations’ characteristic of mountain economic activities;

- the models with large variations (e.g., I16.2021-Model_27, RMSE>600000) reflect the volatility of certain segments, especially against the backdrop of external factors (climate change, strong tourist seasonality, or limited access to resources).

Linear regressions confirmed significant correlations between entrepreneurship stimulation policies (subsidies, infrastructure) and the growth of mountain businesses, especially in the fields of tourism, mountain agriculture, and local craftsmanship (as shown in the following tables and figures).

The study of mountain entrepreneurship in the European industry highlights several relevant aspects for the development and sustainability of this sector. Based on the conducted analyses, the main characteristics of mountain businesses, success factors, challenges, and emerging opportunities for entrepreneurs in European mountain regions were identified.

European mountain entrepreneurship is characterized by several distinctive features, including:

- dependence on natural resources: most businesses in mountain areas rely on the sustainable use of local resources, including organic farming, mountain tourism, and forestry;

- small business sizes: micro-enterprises and small businesses dominate this sector, many of which are family-owned businesses;

- focus on innovation and sustainability: the use of green technologies and the integration of eco-friendly practices are fundamental aspects of mountain entrepreneurship.

Mountain industrial entrepreneurship plays a crucial role in the economic development of alpine and subalpine regions. Its main features include:

- exploitation and processing of local resources: the mountain industry relies on the extraction of local raw materials such as timber, stone, and rare metals, which are used in various industrial sectors;

- specialized production and traditional crafts: in addition to large production units, mountain areas are recognized for traditional craftsmanship and artisanal industries;

- advanced technologies and sustainability: the development of eco-friendly technologies, such as energy-efficient factories and raw material recycling, contributes to reducing the environmental impact.

From the analysis of the collected data, several essential factors for the success of mountain entrepreneurs emerge:

- access to finance and institutional support: EU funds and rural development programs have a significant impact on the sustainability of mountain businesses;

- collaboration between entrepreneurs and local communities: partnerships and cooperation with local authorities and other businesses contribute to increased competitiveness;

- adaptability to market changes: the ability to innovate and adapt to fluctuating market demands is a key determinant for the longevity of mountain businesses.

Among the main obstacles faced by mountain entrepreneurs, especially in the industrial sector, are as following:

- limited accessibility and deficient infrastructure: transportation and logistics difficulties hinder development and market access;

- dependence on seasonality: most mountain economic activities are strongly influenced by seasonality, leading to fluctuating income;

- challenges in attracting labor: the active population tends to migrate to urban areas, reducing the availability of skilled labor.

Despite the challenges, mountain entrepreneurship benefits from multiple development opportunities:

- growing interest in eco-friendly and sustainable tourism: current trends favor the development of mountain tourism businesses focused on authentic experiences and ecotourism;

- digitalization and online commerce: expanding sales through digital platforms offers new opportunities for accessing international markets;

- renewable energy innovations: the use of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, can help reduce costs and increase sustainability.

These results underscore the importance of supporting mountain entrepreneurship through appropriate policies and support programs to ensure the sustainable economic development of European mountain regions.

European mountain entrepreneurship has significant potential but requires policies tailored to the specific geographical and economic characteristics. The study demonstrates that statistical forecasting tools can guide decisions for:

- supporting mountain SMEs (access to finance, digitalization);

- diversifying economic activities (green energy, agro-tourism);

- strengthening resilience to crises.

The results serve as a basis for future research and regional policies focused on sustainability. These findings allow for the evaluation of the impact of various economic policies and development strategies on the entrepreneurial sector in mountain regions, highlighting opportunities for growth and sustainable development in this field.

The results suggest that entrepreneurial development strategies in the mountain industry should be adapted to the specifics of each European mountain region. Forecast models and econometric analysis can assist decision-makers in these regions in developing more targeted economic policies that support SME growth, stimulate mountain tourism, and ensure the development of a sustainable mountain economy. Additionally, forecasting models can be used to anticipate economic trends and adjust long-term development strategies in these regions.

Among the most important methods for solving problems in the mountain industry are the development of the food industry and small industries. The food industries and small industries in mountain regions play an essential role in the economy of these areas, having a significant impact on economic development and maintaining the stability of the local population. In the context of European mountain economies, these industries are closely linked to the use of natural resources, such as mountain agricultural products, traditional foods, and local craftsmanship. The food industries, through product diversification and the implementation of eco-friendly technologies, contribute not only to sustaining the local economy but also to creating sustainable jobs. These sectors are often based on traditional production processes, and small businesses, mostly family-owned, play a key role in maintaining the authenticity and distinctiveness of the mountain region.

According to research on mountain economies in Europe, the food industry and small industries have great potential for sustainable development, given the growing demand for eco-friendly and authentic products. At the same time, challenges remain significant, including deficient infrastructure and accessibility issues that limit the expansion of markets for local products. However, there are multiple opportunities for these industries, especially through digitalization and diversification of economic activities such as agro-tourism and rural tourism, which bring additional economic benefits. Investments in infrastructure, institutional support, and the promotion of a favorable legislative framework are essential for increasing the competitiveness and resilience of these industries in the face of economic and climate challenges.

The main conceptual results of the paper can be summarized as follows:

- adapting to the specificity of mountain areas: the results show that uniform strategies are not effective. For example, some regions benefit from investments in tourism, while others need support for traditional industries (wood, dairy products);

- reducing economic gaps: the models identified significant disparities between regions, suggesting the need for differentiated funding programs;

- anticipating risks: data-based forecasts can help manage the impact of climate change and seasonal variations on small businesses.

Conclusion

Mountain industrial entrepreneurship in Europe has significant growth potential but is influenced by both economic and ecological challenges. The forecasting models applied in this study highlighted the main trends and factors that will determine the development of this sector from 2021 to 2035. Initial growth will be supported by sustainable tourism policies and infrastructure investments, while digitalization and economic activity diversification will accelerate development between 2026 and 2030. By 2035, the sector will stabilize, and its development will depend on factors such as automation, adaptation to climate change, and cross-border collaborations. However, regional disparities will persist, with Western European regions holding a significant advantage due to better access to funding and favorable policies.

To ensure the sustainable development of mountain industrial entrepreneurship, it is essential to invest in infrastructure, promote digital innovations, and support economic policies that assist SMEs and the diversification of economic activities. Collaboration between entrepreneurs and local authorities is another key factor for increasing competitiveness and adaptability in the face of economic and climate changes. Additionally, implementing strategies for the repurposing of abandoned industrial lands in mountain regions could represent an important opportunity for revitalizing these areas and creating new sources of sustainable income.

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized artificial intelligence tools for assistance in statistical analysis and data interpretation. Following this, the authors rigorously reviewed, validated, and refined all results, ensuring accuracy and coherence. The final content reflects the authors’ independent analysis, critical revisions, and scholarly judgment. The authors assume full responsibility for the integrity and originality of the published work.

References

- Eurostat (2025). Business demography and high growth enterprises by NACE Rev. 2 activity and other typologies [urt_bd_hgn__custom_15325082].

- European Environment Agency. (2010). Recognising the true value of Europe’s mountains. https://www.eea.europa.eu/highlights/recognising-the-true-value-of.

- Flury, C., Moschitz, H., & Perlik, M. (2013). Agrifood systems in mountain regions: From subsistence to specialization. Mountain Research and Development, 33(2), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Fournier, M., Guiraud, V., & Morsel, J. (2023). Mountains and food: Current trends and challenges in Europe’s mountain regions. Revue Géographique Alpine, 111(1), 1–16. https://journals.openedition.org/rga/10885.

- Grison, S., & Créti, L. (2023). Territorialising industries in the French Alps. Regional Studies, 57(4), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Grison, S., Créti, L., & Guiraud, V. (2023). Livestock industries and urban-rural dynamics in the French Alps. Journal of Rural Studies 2023, 85, 123–134.

- . [CrossRef]

- Guiraud, V., Fournier, M., & Morsel, J. (2023). Gardens and self-consumption in mountain territories. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 12(2), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Jelev, V. Natural resources and sustainable development in a mountain economy. Annals of Spiru Haret University. Economic Series 2023, 23, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- . [CrossRef]

- López-i-Gelats, F. Rural development and food systems in mountain regions. Journal of Rural Studies 2013, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, M. (2022). The Alps as context. In Alpine industrial landscapes: Towards a new approach for brownfield redevelopment in mountain regions (pp. 29-61). Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Modica, M., & Weilacher, U. (2019). Alpine industrial landscapes in transition: Towards a transferable strategy for brownfield transformation in mountain regions. AESOP 2019 Conference - Book of Papers. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marcello-Modica-2/publication/333531855_Alpine_Industrial_Landscapes_in_Transition_Towards_a_transferable_strategy_for_brownfield_transformation_in_mountain_regions/links/5d2d74f2299bf1547cb9e0cd/Alpine-Industrial-Landscapes-in-Transition-Towards-a-transferable-strategy-for-brownfield-transformation-in-mountain-regions.pdf.

- Perlik, M. (2019). The reconfiguration of mountain populations and urban-rural relations. Mountain Research and Development, 39(4), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Pettenati, M. (2022). Metromountain policies: Urban-rural interactions in mountain regions. Urban Studies, 59(3), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Rey, R. Politici de dezvoltare durabilă în Carpații României. Calitatea Vieții 1997, 8, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Solelhac, A. (2021). Mountain resort marketing and management. Routledge.

- Zareba, A., & Krzeminska, A. (2010). The concept of the model mountain valley: A case study of the Biala Ladecka river. Problemy Ekologii Krajobrazu, (28).

Table 1.

Model Forecast Statistics.

Table 1.

Model Forecast Statistics.

| Model |

Stationary R-squared |

R-squared |

RMSE |

MAPE |

MAE |

MaxAPE |

MaxAE |

Normalized BIC |

| I1.2021-Model_1 |

2.220E-16 |

2.220E-16 |

53512.539 |

410.551 |

37124.816 |

4001.255 |

146901.143 |

21.964 |

| I1.2022-Model_2 |

2.220E-16 |

2.220E-16 |

53373.319 |

473.371 |

37629.745 |

4896.578 |

146220.643 |

21.959 |

| I2.2021-Model_3 |

1.110E-16 |

1.110E-16 |

2855.529 |

475.876 |

2141.551 |

5238.903 |

6700.214 |

16.103 |

| I2.2022-Model_4 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

2870.759 |

526.423 |

2231.286 |

5937.255 |

6338.000 |

16.113 |

| I3.2021-Model_5 |

1.332E-15 |

1.332E-15 |

0.604 |

36.010 |

0.470 |

104.225 |

1.240 |

-0.803 |

| I3.2022-Model_6 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.496 |

39.831 |

0.415 |

134.195 |

0.778 |

-1.195 |

| I4.2021-Model_7 |

|

|

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

|

| I4.2022-Model_8 |

|

|

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

|

| I5.2021-Model_9 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

2575.481 |

776.120 |

1884.994 |

8324.615 |

6736.615 |

15.905 |

| I5.2022-Model_10 |

2.220E-16 |

2.220E-16 |

2713.581 |

694.858 |

2074.414 |

7469.636 |

6517.538 |

16.009 |

| I6.2021-Model_11 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

64.512 |

255.148 |

39.552 |

1185.203 |

182.705 |

8.552 |

| I6.2022-Model_12 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

61.427 |

516.093 |

37.934 |

4076.364 |

172.418 |

8.454 |

| I7.2021-Model_13 |

0.476 |

0.476 |

1401.245 |

184.267 |

1094.184 |

1102.151 |

2771.294 |

14.885 |

| I7.2022-Model_14 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

2035.800 |

643.814 |

1618.661 |

5505.981 |

4264.727 |

15.455 |

| I8.2021-Model_15 |

1.221E-15 |

1.221E-15 |

1.837 |

38.846 |

1.583 |

102.929 |

3.280 |

1.414 |

| I8.2022-Model_16 |

1.110E-15 |

1.110E-15 |

1.678 |

33.251 |

1.348 |

133.062 |

2.821 |

1.254 |

| I10.2021-Model_17 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

460.679 |

236.278 |

250.852 |

2070.085 |

1465.385 |

12.463 |

| I10.2022-Model_18 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

577.747 |

309.357 |

323.100 |

2052.778 |

1615.500 |

12.949 |

| I12.2021-Model_19 |

1.110E-15 |

1.110E-15 |

4.669 |

30.863 |

3.587 |

83.863 |

9.152 |

3.279 |

| I12.2022-Model_20 |

-2.442E-15 |

-2.442E-15 |

5.608 |

35.869 |

4.708 |

72.614 |

7.616 |

3.666 |

| I13.2021-Model_21 |

2.109E-15 |

2.109E-15 |

2.779 |

32.375 |

2.066 |

77.972 |

6.711 |

2.241 |

| I13.2022-Model_22 |

2.331E-15 |

2.331E-15 |

2.562 |

29.418 |

1.955 |

87.342 |

5.019 |

2.099 |

| I14.2021-Model_23 |

-2.442E-15 |

-2.442E-15 |

2.229 |

34.263 |

1.695 |

133.658 |

5.058 |

1.800 |

| I14.2022-Model_24 |

1.887E-15 |

1.887E-15 |

3.718 |

45.678 |

2.932 |

96.930 |

7.086 |

2.844 |

| I15.2021-Model_25 |

1.110E-16 |

1.110E-16 |

6.115 |

155.923 |

3.719 |

923.611 |

17.474 |

3.828 |

| I15.2022-Model_26 |

1.110E-16 |

1.110E-16 |

6.115 |

155.923 |

3.719 |

923.611 |

17.474 |

3.828 |

| I16.2021-Model_27 |

-2.220E-16 |

-2.220E-16 |

607177.035 |

959.081 |

437344.125 |

9633.142 |

1406132.250 |

26.840 |

| I16.2022-Model_28 |

1.110E-16 |

1.110E-16 |

612200.047 |

935.196 |

416188.611 |

9451.229 |

1437255.833 |

26.857 |

| I17.2021-Model_29 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

3482.545 |

669.528 |

2449.611 |

6957.778 |

8862.333 |

16.518 |

| I18.2021-Model_30 |

2.998E-15 |

2.998E-15 |

0.351 |

28.609 |

0.280 |

73.939 |

0.522 |

-1.863 |

| I18.2022-Model_31 |

-1.776E-15 |

-1.776E-15 |

0.554 |

39.767 |

0.404 |

99.464 |

1.293 |

-0.952 |

| I19.2021-Model_32 |

1.110E-16 |

1.110E-16 |

4467.195 |

1261.917 |

3012.132 |

11994.545 |

11455.909 |

17.027 |

| I19.2022-Model_33 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

6025.749 |

1847.049 |

3878.741 |

15663.492 |

14742.778 |

17.652 |

| I20.2021-Model_34 |

2.220E-16 |

2.220E-16 |

6316.157 |

433.367 |

3618.486 |

4141.012 |

18513.583 |

17.709 |

| I20.2022-Model_35 |

-2.220E-16 |

-2.220E-16 |

6300.247 |

1283.167 |

3617.181 |

14171.458 |

18519.417 |

17.704 |

| I21.2021-Model_36 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

3086.549 |

300.302 |

2089.514 |

2401.156 |

8141.417 |

16.277 |

| I21.2022-Model_37 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

3462.888 |

1027.351 |

2317.940 |

9131.842 |

8540.900 |

16.530 |

| I22.2021-Model_38 |

8.882E-16 |

8.882E-16 |

0.564 |

51.857 |

0.440 |

124.651 |

1.214 |

-0.916 |

| I22.2022-Model_39 |

-6.661E-16 |

-6.661E-16 |

0.632 |

57.538 |

0.574 |

112.618 |

0.796 |

-0.674 |

| I23.2021-Model_40 |

2.220E-15 |

2.220E-15 |

0.694 |

62.114 |

0.562 |

333.506 |

1.167 |

-0.513 |

| I23.2022-Model_41 |

2.220E-16 |

2.220E-16 |

0.485 |

47.953 |

0.377 |

244.156 |

0.855 |

-1.228 |

| I24.2021-Model_42 |

-0.066 |

0.246 |

33.854 |

154.331 |

26.987 |

1233.983 |

55.603 |

7.251 |

| I24.2022-Model_43 |

0.852 |

0.325 |

28.859 |

79.821 |

23.509 |

552.470 |

44.761 |

7.139 |

| I25.2021-Model_44 |

1.110E-16 |

1.110E-16 |

576619.430 |

1079.848 |

436447.521 |

10025.736 |

1215095.455 |

26.748 |

| I25.2022-Model_45 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

582961.784 |

1026.026 |

413287.471 |

9548.053 |

1254080.545 |

26.770 |

| I26.2021-Model_46 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

2233.096 |

994.509 |

1785.320 |

8267.083 |

4796.900 |

15.653 |

| I27.2021-Model_47 |

2.220E-16 |

2.220E-16 |

2864.595 |

2724.302 |

2168.280 |

23404.000 |

5503.600 |

16.151 |

| I27.2022-Model_48 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

3191.451 |

1859.566 |

2017.407 |

14456.349 |

8133.111 |

16.381 |

| I28.2021-Model_49 |

1.998E-15 |

1.998E-15 |

22.674 |

73.220 |

18.276 |

297.552 |

34.278 |

6.473 |

| I28.2022-Model_50 |

-4.441E-16 |

-4.441E-16 |

23.652 |

89.175 |

20.986 |

278.498 |

32.083 |

6.557 |

Table 2.

Model Parameters.

Table 2.

Model Parameters.

| Arima Model Parameters |

|---|

| Model |

Transformation |

Estimate |

SE |

t |

Sig. |

| I1.2021-Model_1 |

Constant |

48558.857 |

14301.828 |

3.395 |

0.005 |

| I1.2022-Model_2 |

Constant |

49116.357 |

14264.620 |

3.443 |

0.004 |

| I2.2021-Model_3 |

Constant |

2989.786 |

763.172 |

3.918 |

0.002 |

| I2.2022-Model_4 |

Constant |

3079.000 |

767.243 |

4.013 |

0.001 |

| I3.2021-Model_5 |

Constant |

1.450 |

0.174 |

8.323 |

0.000 |

| I3.2022-Model_6 |

Constant |

1.358 |

0.143 |

9.486 |

0.000 |

| I4.2021-Model_7 |

Constant |

1.000 |

0.000 |

|

|

| I4.2022-Model_8 |

Constant |

1.000 |

0.000 |

|

|

| I5.2021-Model_9 |

Constant |

2527.385 |

714.310 |

3.538 |

0.004 |

| I5.2022-Model_10 |

Constant |

2876.462 |

752.612 |

3.822 |

0.002 |

| I6.2021-Model_11 |

Constant |

47.295 |

19.451 |

2.431 |

0.035 |

| I6.2022-Model_12 |

Constant |

43.852 |

18.521 |

2.368 |

0.039 |

| I7.2021-Model_13 |

Constant |

2072.089 |

235.791 |

8.788 |

0.000 |

| |

AR |

-0.703 |

0.214 |

-3.290 |

0.007 |

| I7.2022-Model_14 |

Constant |

2130.273 |

613.817 |

3.471 |

0.006 |

| I8.2021-Model_15 |

Constant |

4.850 |

0.510 |

9.519 |

0.000 |

| I8.2022-Model_16 |

Constant |

4.941 |

0.506 |

9.763 |

0.000 |

| I10.2021-Model_17 |

Constant |

390.615 |

127.769 |

3.057 |

0.010 |

| I10.2022-Model_18 |

Constant |

387.500 |

182.700 |

2.121 |

0.063 |

| I12.2021-Model_19 |

Constant |

13.348 |

1.295 |

10.309 |

0.000 |

| I12.2022-Model_20 |

Constant |

15.294 |

1.691 |

9.045 |

0.000 |

| I13.2021-Model_21 |

Constant |

7.439 |

0.771 |

9.652 |

0.000 |

| I13.2022-Model_22 |

Constant |

7.831 |

0.772 |

10.139 |

0.000 |

| I14.2021-Model_23 |

Constant |

5.912 |

0.618 |

9.563 |

0.000 |

| I14.2022-Model_24 |

Constant |

7.464 |

1.121 |

6.659 |

0.000 |

| I15.2021-Model_25 |

Constant |

0.494 |

1.765 |

0.280 |

0.785 |

| I15.2022-Model_26 |

Constant |

0.494 |

1.765 |

0.280 |

0.785 |

| I16.2021-Model_27 |

Constant |

573184.750 |

175277.023 |

3.270 |

0.007 |

| I16.2022-Model_28 |

Constant |

560657.167 |

176726.991 |

3.172 |

0.009 |

| I17.2021-Model_29 |

Constant |

4234.667 |

1005.324 |

4.212 |

0.001 |

| I18.2021-Model_30 |

Constant |

1.148 |

0.111 |

10.338 |

0.000 |

| I18.2022-Model_31 |

Constant |

1.117 |

0.175 |

6.378 |

0.000 |

| I19.2021-Model_32 |

Constant |

4233.091 |

1346.910 |

3.143 |

0.010 |

| I19.2022-Model_33 |

Constant |

5517.222 |

2008.583 |

2.747 |

0.025 |

| I20.2021-Model_34 |

Constant |

5937.417 |

1823.317 |

3.256 |

0.008 |

| I20.2022-Model_35 |

Constant |

5708.583 |

1818.725 |

3.139 |

0.009 |

| I21.2021-Model_36 |

Constant |

3426.583 |

891.010 |

3.846 |

0.003 |

| I21.2022-Model_37 |

Constant |

3508.100 |

1095.061 |

3.204 |

0.011 |

| I22.2021-Model_38 |

Constant |

0.966 |

0.178 |

5.417 |

0.000 |

| I22.2022-Model_39 |

Constant |

1.254 |

0.211 |

5.956 |

0.000 |

| I23.2021-Model_40 |

Constant |

1.517 |

0.209 |

7.252 |

0.000 |

| I23.2022-Model_41 |

Constant |

1.205 |

0.146 |

8.232 |

0.000 |

| I25.2021-Model_44 |

Constant |

530588.545 |

173857.374 |

3.052 |

0.012 |

| I25.2022-Model_45 |

Constant |

515495.455 |

175769.564 |

2.933 |

0.015 |

| I26.2021-Model_46 |

Constant |

2008.100 |

706.167 |

2.844 |

0.019 |

| I27.2021-Model_47 |

Constant |

2350.400 |

905.865 |

2.595 |

0.029 |

| I27.2022-Model_48 |

Constant |

2037.889 |

1063.817 |

1.916 |

0.092 |

| I28.2021-Model_49 |

Constant |

45.798 |

7.170 |

6.387 |

0.000 |

| I28.2022-Model_50 |

Constant |

43.603 |

7.479 |

5.830 |

0.000 |

| Exponential Smoothing Model Parameters |

| Model |

Transformation |

Estimate |

SE |

t |

Sig. |

| I24.2021-Model_42 |

Alpha (Level) |

0.731 |

0.287 |

2.545 |

0.027 |

| I24.2022-Model_43 |

Alpha (Level) |

0.100 |

0.104 |

0.963 |

0.358 |

| |

Gamma (Trend) |

2.336E-05 |

0.129 |

0.000 |

1.000 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).