1. Introduction

The hypothalamus is an archetypical, evolutionary conserved vertebrate brain structure that controls essential physiological processes, including food and fluid intake, energy homeostasis, stress responses, sleep/wake cycles, as well as sexual behavior and reproduction, to ensure the subject’s survival[

1]. Consequently, the hypothalamus contains a collection of topographically segregated neuronal loci, each possessing their own molecular signature and synaptic connectivity. For instance, the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), flanking the third ventricle bilaterally, and mainly consisting of excitatory vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (

Slc17a6/VGLUT2)

+ neurons (

Figure 1a), integrates neuroendocrine and autonomic functions through its dorsolateral magnocellular and medioventral parvocellular subdivisions. Its neurosecretory magnocellular cells are large-bodied neurons expressing either vasopressin (m

AVP) or oxytocin (m

OXT), with both subpopulations projecting directly to the posterior pituitary, where they release their hormones directly into the systemic circulation to regulate blood pressure, water-balance, and maternal, social and feeding behaviors, respectively[

2]. In contrast, parvocellular (small-bodied) neurosecretory neurons contain corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH; p

CRH), thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH; p

TRH), or somatostatin (SST; p

SST) and extend their axons to the median eminence, a gateway structure for hypothalamic hormones to reach the anterior pituitary through the hypophyseal portal system. Once released into the portal blood, CRH orchestrates the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis upon stress, with sequential release events for adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary, and cortisol from the adrenal cortex. TRH stimulates the release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) from the anterior pituitary, thus controlling metabolic and cardiovascular function through the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis. Antagonistically, SST inhibits the release of TSH from the anterior pituitary[

3]. Thus, the PVN is essential for bodily metabolism with its dysfunction implicated in obesity, hypertension, diabetes insipidus

2, as well as anxiety and depression[

4,

5].

To control the many physiological processes, the PVN is innervated by long-distance afferents, both excitatory and inhibitory in nature, originating from multiple brain regions: e.g., from excitatory proopiomelanocortin (POMC)

+/

Slc17a6+ glutamatergic[

6], and inhibitory agouti-related protein (AgRP)/neuropeptide Y neurons[

7] of the arcuate nucleus to control energy expenditure[

8,

9]; glutamatergic neurons of the amygdalo-piriform transition area, and inhibitory neurons of the central amygdala to modulate CRH secretion upon fear induction[

10]; as well as inhibitory neurons of the bed nucleus of the stria terminals upon reward seeking and stress[

11]. As a general principle, the temporal precision of both its innate neurocircuits and neuroendocrine output of the PVN is controlled by inhibitory neurotransmission originating in nearby brain areas, rather than intrinsically, through GABAA receptor-dependent inhibition[

12,

13,

14]. However, synaptic integration is unlikely to be exclusively reliant on distant-positioned neurons[

12,

13], particularly in the absence of a major interneuron (GABA) contingent locally (

Figure 1a1,b)[

15]. Thus, we hypothesized that synaptic synchronization and local neurotransmitter availability, from both local collaterals and afferents, could additionally rely on fast-acting retrograde signaling. Indeed, compared to other hypothalamic areas, the PVN is known for its expression of type 1 cannabinoid receptor mRNA (

Cnr1/CB

1R)[

16], a G

i/o protein-coupled receptor negatively affecting neurotransmitter release (

Figure 1a

3,b-b

2). The activation of presynaptic CB

1Rs occurs through 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG)[

17] and anandamide (AEA)[

18], endocannabinoids produced in subsynaptic dendrites[

19]. Indeed, engagement of CB1Rs in the PVN was shown to influence energy metabolism[

20,

21], food intake[

20,

22], and the stress response[

23,

24]. However, the cellular architecture of the endocannabinoid system on identified neuronal and astrocyte populations in the PVN remains unresolved, whether during development or in adulthood.

Here, we produced a comprehensive expression map of cannabinoid receptors (

Cnr1/

Cnr2/

Gpr55), as well as the putative enzymes involved in 2-AG (

Dagla/

Daglb, Mgll) and AEA metabolism (

Napepld/

Gde1, Faah) at successive developmental stages. Particularly, we found that m

OXT and m

AVP, which appear at embryonic day (E) 15.5, expressed

Cnr1, but neither

Cnr2 nor

Gpr55, towards postnatal day (P)21, that is pre-adolescence. Once the PVN became enriched in p

TRH/p

CRH neurons, these neuronal subtypes also expressed

Cnr1. Spatiotemporal

Dagla/

Daglb and

Mgll expression tightly followed that of

Cnr1, also recapitulating a robust

Daglb-to-Dagla switch at neonatal life, in line with the predominance of DAGLα in retrograde neurotransmission at mature synapses[

25]. For p

SST neurons, which segregate lastly in the PVN, molecular arrangements were indistinguishable from other neuronal subtypes, yet expressional patterns were delayed as much as the emergence of p

SST neurons themselves.

Napepld mRNA content was minimal in all neurons, while

Faah expression increased towards P21. Single-cell RNA-seq data showed a near complete lack of cannabinoid receptors in astrocytes of the adult PVN, but revealed

Dagla expression. We found reliable amounts of neither

Napepld nor

Faah mRNA in astrocytes, reflecting previous data suggesting that astrocytes are more reliant on 2-AG signaling when interacting with nearby neurons[

26,

27]. In sum, we described the molecular constituents of the endocannabinoid system in identified magnocellular and parvocellular neurons, as well as astrocytes, at single-cell-precision during fetal and postnatal development of the PVN.

2. Results

Neuronal diversity in the PVN during brain development. We defined neuronal subtypes in the PVN by combining neurotransmitter and neuropeptide-related gene signatures at embryonic (E15.5-E17.5), neonatal (P0), juvenile (P2, P10), and pre-adolescent (P23) hypothalamus datasets (

Supporting Figure 1a)[

15]. At E15.5, magnocellular neurosecretory cells expressing

Oxt (m

OXT) and

Avp (m

AVP) mRNA appeared first, with mRNA levels gradually rising to P21 (

Figure 2a-a

1). We caution that the sequence similarity between

Oxt and

Avp could have limited the precise assessment of

Avp mRNA present, for which

Avp itself was excluded for subsequent analysis[

28]. Next, we distinguished parvocellular cells at E17.5, particularly p

CRH and p

TRH neurons, as well as a late-emerging p

SST group after birth (

Figure 2a2-a4). For parvocellular cells, mRNA levels increased as a factor of developmental stage and peaked at P10-to-P21. The temporal pattern described here was validated by an RNA-sequencing dataset published earlier[

29], which also show m

OXT/m

AVP > p

CRH/p

TRH > p

SST neurons, even if at shallower resolution (

Supporting Figure 1a vs. a1;

Supporting Figure 2a-a4). This sequence of events is compatible with the concept that long-range projection neurons of the hypothalamus mature earlier than locally-targeting neurons and/or interneurons[

15].

Assembly of the endocannabinoid system. To map genes broadly associated with the ‘endocannabinoid system’, we first examined gene expression for

Cnr1,

Cnr2[

16,

30], and

Gpr55[

31]. We found

Cnr1 expression at molecule numbers exceeding 3,000 per cell at E15.5 and E17.5 in subsets of m

OXT, p

TRH, and p

CRH neurons, with its levels maintained until P21 (>1,000 mRNA copies per cell;

Figure 3a,b). In p

SST neurons,

Cnr1 was detected in 15-20% of cells only postnatally, correlating the temporal expression pattern of

Sst itself (

Figure 2a

4), even if in a small sample size that was not processed further. Even though

Cnr2 mRNA was previously found in the hypothalamus[

32], we could not reliably detect

Cnr2 mRNA transcripts by single-cell RNA-seq in neurons

, suggesting limited, if any,

Cnr2 contributions to neuronal development, at least in the

PVN (

Figure 3a

1). In contrast, we detected a few

Gpr55-containing neurons, mainly m

OXT and p

TRH cells, with low mRNA copy numbers (<100 mRNA copies per cell) at neonatal and juvenile

ages (

Figure 3a

2,b) [

33]. In sum,

Cnr1 is the main cannabinoid receptor in neurons of the PVN to respond to (endo-)cannabinoid signals, whether during axonal growth and guidance, synaptogenesis, or retrograde signaling at maturity[

34].

Next, we assessed

Dagla,

Daglb[

35], and

Mgll[

36] mRNA expression. Both

Dagla and

Daglb were found in m

OXT, p

TRH, and p

CRH neurons at both E15.5 and E17.5, with mRNA levels, but not cell abundance, diminishing into pre-adolescence (

Figure 4a,a

1,b). Expression of

Dagla/

Daglb in p

SST cells was delayed to postnatal life, as much as seen for

Cnr1 and

Sst mRNAs (

Figure 2a

4 and

Figure 4a). During embryonic stages, we found a ~2.5-fold higher number of neurons expressing

Daglb, as compared to

Dagla (84 vs. 35 cells, over m

OXT and p

TRH neurons), which reversed between E17.5 and P10 (52 vs. 86 cells;

Figure 4b), corroborating a developmental isoform switch model proposed earlier[

25,

35,

37]. In parallel,

Mgll expression gradually decreased towards P21. Of note,

Mgll mRNA was found in the same neuronal clusters, but not cells, as

Dagla/

Daglb (

Figure 4a

2,b). These data suggest that molecular and rate-limiting constituents of 2-AG signaling are present throughout neuronal diversification in the PVN, and could contribute to cell-state-specific intercellular communication, e.g., neuritogenesis[

38,

39].

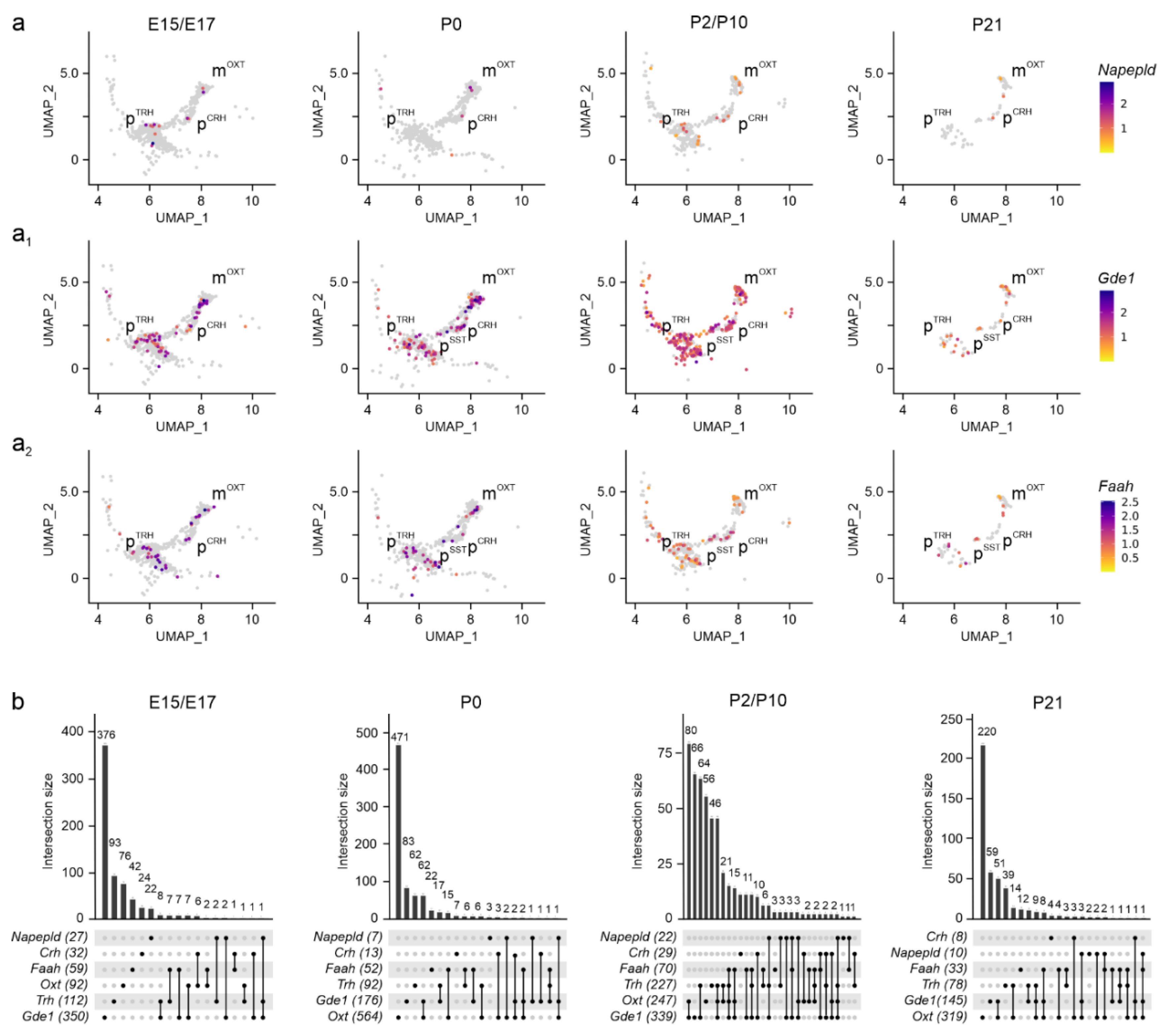

Subsequently, we determined the cellular foci for

Napepld mRNA expression, implicated in AEA synthesis[

40,

41].

Napepld mRNA was sparse in both magnocellular and parvocellular PVN neurons at any time point (

Figure 5a,b). In contrast,

Gde1 expression[

42] was promiscuous and significant in all neuronal clusters (

Figure 5a1,b). The expression of

Faah, the enzyme chiefly degrading AEA[

43], was pronounced (>500 mRNA molecules/cell) throughout brain development in both magnocellular and parvocellular neurons (

Figure 5a

2,b). These data suggest 2-AG signaling in the PVN could affect many more neurons, corroborating its proposed role as the primary endocannabinoid involved with both neuritogenesis and retrograde signaling[

44].

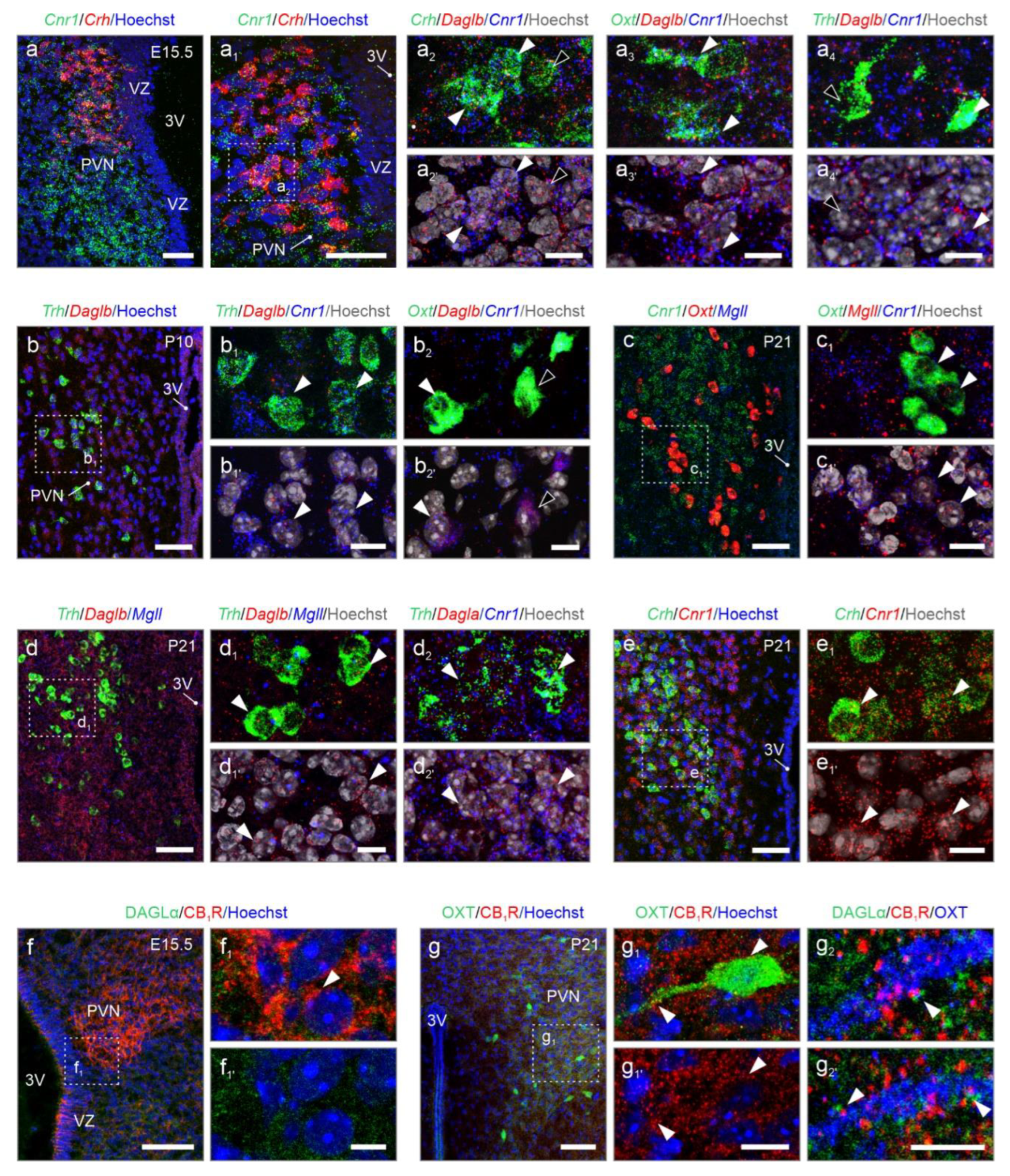

Nanoscale anatomy of 2-AG signaling revealed by in situ hybridization. We have performed multiplexed fluorescence in situ hybridization to reconstruct 2-AG signaling, which appeared superior relative to AEA in the PVN (

Figure 6). At E15.5, the prospective territory of the PVN was outlined by

Cnr1 mRNA expression, which reminisced the shape of the adult structure (

Figure 6a,a

1 vs.

Figure 1b):

Cnr1 mRNA localized to the majority of p

CRH neurons (

Figure 6a

1,2), alike to subpopulations of m

OXT and p

TRH neurons (

Figure 6a

3,4). While

Daglb mRNA transcripts were found in most p

CRH, m

OXT and p

TRH cells (

Figure 6a

1-4),

Dagla was not detected reliably by in situ hybridization at E15.5, even if we excluded technical frailties by visualizing

Dagla in the hippocampus

en masse during embryogenesis (

Figure S3a,b). Thus, we continued with the analysis of

Daglb for developmental stages and found

Daglb mRNA abundantly at E15.5 (

Figure 6a

2). At P10, both

Cnr1 and

Daglb remained expressed in both p

TRH and m

OXT cells (

Figure 6b-c

1).

Mgll was present in m

OXT neurons, and co-existed with

Cnr1 (

Figure 6c

1,c

1). At P21,

Daglb and

Mgll were rarely expressed. In contrast,

Dagla co-localized with

Cnr1 primarily in p

TRH neurons (

Figure 6d-d

2). Similarly, we continued to detect

Cnr1 mRNA in p

CRH cells (

Figure 6e,e

1).

Subsequently, we performed immunohistochemistry for DAGLα and CB

1Rs at E15.5 and P21. In accord with our results using in situ hybridization, CB

1R protein accumulated in the fetal PVN, and decorated punctae and processes, which we have interpreted as labeling of growth cones and nascent synapses on afferent input. In contrast, DAGLα immunoreactivity was minimal (

Figure 6f-f

1). At P21, CB

1Rs continued to decorate terminal-like punctae, encircling perikarya and processes of, e.g., m

OXT-containing neurons (

Figure 6g,g

1), with DAGLα confined mostly along the dendrites of neurons and in apposition to CB

1Rs (

Figure 6g,g

2). In sum, cell-resolved neuroanatomy confirmed cell identities, transcript switches for

Dagla and

Daglb, the developmental dynamics for

Cnr1 mRNA, and classical configuration of DAGLα and CB

1R for retrograde signaling at the protein level.

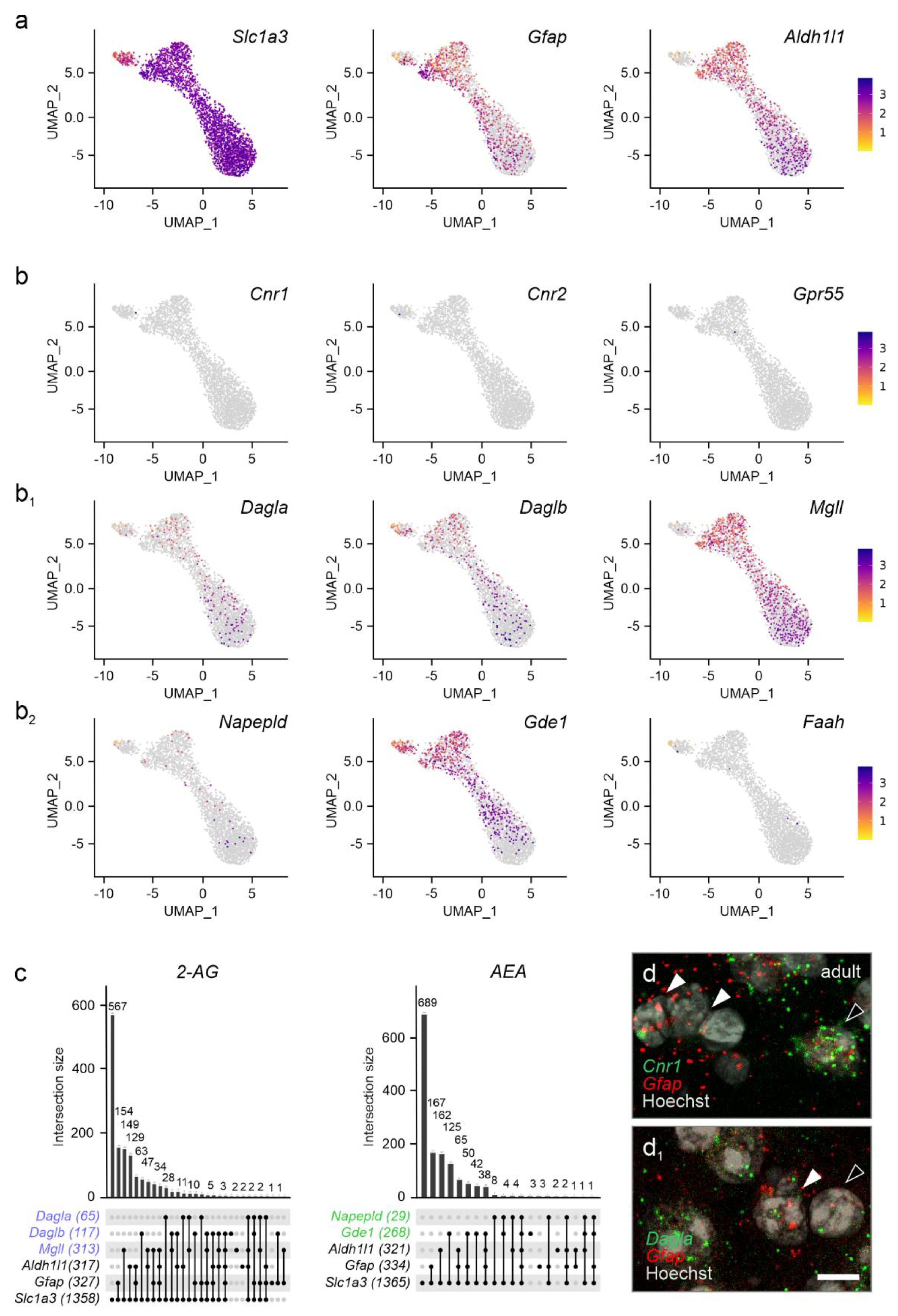

The endocannabinoid system in astrocytes. As endocannabinoid signaling is essential for neuron-to-astrocyte communication in multiple physiological processes[

45,

46,

47], we addressed if cannabinoid receptors and enzymes related to endocannabinoid metabolism were expressed in astrocytes in the pre-adolescent PVN. We justify the choice of P21 by the postnatal window of astrocytogenesis and maturation that sequentially occur between P2-P14[

48]. Thus, terminally-differentiated astrocytes that could reflect

bona fide PVN-related signaling could be resolved starting at P21[

48]. We subdivided astrocytes based on their prototypical markers: excitatory amino acid transporter 1 (

Slc1a3)[

49], glial fibrillary acidic protein (

Gfap)[

50], and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 (

Aldh1l1)[

51], which jointly defined a cellular cluster (

Figure 7a). When plotting cannabinoid receptors, we found a near complete lack of

Cnr1,

Cnr2 and

Gpr55 mRNA (

Figure 7b,c), which was unexpected as functional CB

1Rs have previously been localized to hypothalamic nuclei other than the PVN[

52], as well as also to extrahypothalamic regions[

26,

46,

53,

54]. Both

Dagla and

Daglb mRNA were found in subsets of astrocytes, while

Mgll mRNA was present in a larger subset (

Figure 7b

1,c). Despite

Gde1 being present in astrocytes, neither

Napepld nor

Faah could be detected reliably (

Figure 7b

2,c). We validated the above data by in situ hybridization, which showed the lack of

Cnr1 mRNAs but the presence of

Dagla (

Figure 7d,d

1). Thus, astrocytes in the PVN could contribute to endocannabinoid metabolism and assist in shaping synaptic neurotransmission[

55].

3. Discussion

This study describes the developmental dynamics of cannabinoid receptor and endocannabinoid metabolism-related enzyme expression in the PVN of mice. Major findings include that all neurons go through a CB

1R

+ phase during embryonic and postnatal development, which is compatible with previous proposals on CB

1R being ubiquitously expressed upon neurogenic commitment in vertebrates[

38,

56], and is associated with axonal growth and guidance. For 2-AG synthesis, our data recapitulates a developmentally regulated

Daglb-to-

Dagla switch, that has been shown for the cerebral cortex[

57] but not the hypothalamus earlier. Moreover, the finding that

Daglb and

Dagla, but lower amounts of

Mgll, are expressed in neurons of the PVN is compatible with known anatomical arrangements with the PVN being reliant on monosynaptic afferents from external sources (BNST, amygdala, arcuate nucleus, suprachiasmatic nucleus) rather than local interneurons to synchronize its endocrine output. Accordingly, MAGL, together with CB

1Rs, are expected to be expressed outside the PVN to time the presynaptic action of endocannabinoids produced by PVN neurons. Thus, the spatial configuration of endocannabinoid signaling during neuronal diversification in the PVN and in adulthood is adequate to control the avalanche of synaptic inputs arriving from intra- and extrahypothalamic areas. In addition, the importance of retrograde neurotransmission in the PVN is highlighted by the use of gaseous neuromodulators, particularly nitric oxide (NO). Neuronal NO synthase (

Nos1) is particularly abundant in the PVN, as compared to other hypothalamic nuclei, and its effects on food intake[

58,

59], renal sympathetic nerve activity[

60,

61], and sympatho-adrenomedullary outflow[

62] are well described.

Besides cannabinoid receptors, we mapped the cellular distribution of

Dagla, Daglb, Napepld, Gde1, and

Faah, enzymes that are fundamental to the turnover of endocannabinoids. Even though these enzymes are the most abundant to modulate endocannabinoid levels in the brain and at the periphery, we acknowledge the contributions of others that have not been studied: e.g., MGL degrades ~85% of 2-AG in the brain[

63]. In contrast, α/β-hydrolase domain containing 6 (

Abhd6)[

64] and 12 (

Abhd12)[

65] account for ~4% and ~9% of 2-AG degradation, respectively[

63]. Similarly, the metabolic pathway for AEA is complex, and includes

Abhd4, Gde4/7,

Ptpn22, as well as

Lox and

Cox2, for synthesis and degradation respectively (

for extensive reviews see Refs.[

66,

67]). As the biological significance of these enzymes is less well understood, we did not pursue them in this report. We also note that

Gde1 has been found important to AEA synthesis, at least in vitro. Yet, AEA levels in the brain of

Gde1-/- mice do not differ, questioning its role in AEA synthesis in vivo[

68]. Therefore, and given the low abundance of

Napepld mRNA expression, we hypothesize that 2-AG signaling might be more prevalent than AEA in the PVN. While we are confident that our study still provides substantial insights into the architecture of endocannabinoid signaling in the PVN, our datasets will certainly be amenable for further focused analysis if and when those aims are justified.

2-AG is considered to be the main circuit-breaker driving retrograde signaling in a fast, but phasic, manner[

69,

70], since 2-AG is a more potent agonist at the CB1R[

71], is available at up to a 1,000-fold higher concentrations in the brain[

18,

69], and its absence curtails retrograde signaling in the DAGLα knockout mice[

25]. Conversely, AEA is regarded as tonically inhibiting neuronal activity[

44,

70]. In accord with this hypothesis, previous reports suggest that tonic regulation of the HPA axis by AEA occurs either directly at neurons of the PVN[

72] or indirectly through extrahypothalamic sites, such as the basolateral amygdala[

44]. Nevertheless, mRNA levels predict neither protein abundance, nor enzymatic activity[

73]. Therefore, cell-resolved electrophysiology will be best placed to define the contribution of these endocannabinoids to regulating specific behaviors.

While endocannabinoids limit neurotransmitter release through neuronal CB

1Rs, recent studies have proposed that CB

1Rs on astrocytes could instead promote neuronal activity by controlling metabolite availability[

27]. Accordingly, activation of mitochondrial CB

1Rs in astrocytes could regulate glucose metabolism to ensure neuronal bioenergetics[

53]. Furthermore, CB

1Rs localized to astrocyte leaflets ensheathing blood vessels in the nucleus accumbens were implicated in regulating anxiety and depression-like behaviors[

54]. In the hypothalamus, engagement of CB

1Rs on or in astrocytes might regulate processes involved with energy metabolism, including leptin signaling and glycogen storage[

52]. Therefore, we expected astrocytes in the PVN to express CB1Rs (and probably also others). Nevertheless, we could not detect any with the tools available this time. We did however find substantial expression of both DAGL isoforms, implicating astrocytes in 2-AG metabolism. As 2-AG can be released by astrocytes in response to other non-endocannabinoid-mediated signals, such as ATP[

74], we propose that astrocytes could tune neuronal activity through CB

1R-independent 2-AG release. Thus, our findings suggest novel, metabolism-driven endocannabinoid availability as a potential rate-limiting step for the processing of synaptic inputs and translating those into hormonal output at the level of PVN neurons.

4. Materials and Methods

Ethical considerations. Mice were housed under standard husbandry conditions in a temperature and humidity-controlled room (12h/12h light cycle, 55% humidity, 22-24 oC ambient temperature). Animals had ad libitum access to food and water throughout. The maintenance and welfare of the animals conformed to the 2010/63/European Communities Council directive. Experimental protocols for tissue collection were approved by the Austrian Ministry of Science and Research (66.009/0145-WF/II/3b/2014 and 66.009/0277-WF/V3b/2017). Pregnant (embryonic day (E) 15.5), and postnatal day (P) 4, P10, and P21 C57BL/6JRj mice were obtained from Janvier Labs and kept on site as adequate.

Single-Cell RNA-seq data acquisition, and harmonization. This study utilized two publicly available single-cell RNA-seq datasets to examine the expressional dynamics of genes related to endocannabinoid signaling during mouse hypothalamus development. The principal dataset comprised 51,199 cells, 24,340 features, and encompassed all developmental stages[

15]. A second dataset was obtained as a pre-processed AnnData object, and contained 128,006 cells profiled for 27,998 genes along complementary developmental time points[

29,

75]. All subsequent analyses were performed in

R (version 4.3 or higher) within a reproducible workflow framework documented using Quarto notebooks[

76]. Gene expression matrices were appropriately transposed, and cell/gene metadata were standardized. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) coordinates within the dataset were integrated as distinct dimensionality reduction objects within Seurat[

77,

78,

79]. Metadata pertaining to developmental stages and original cluster annotations were preserved. The Romanov

et al.

15 dataset, available as a Seurat RDS file, was loaded and updated to the latest Seurat object specifications. Cluster identities and associated colour palettes were harmonized across both datasets to facilitate comparative analyses.

Cellular quality control and filtering. Stringent quality control was performed on both datasets to exclude potentially compromised cells and technical artefacts. Cells were retained if they had more than 500 unique genes and fewer than 25,000 unique molecular identifiers (UMIs). Additional filtering excluded cells based on high percentages of mitochondrial, ribosomal, or hemoglobin genes, elevated doublet prediction scores, and low transcriptomic complexity (log10 genes per UMI). These thresholds were enforced to enrich high-quality cellular profiles while acknowledging the potential exclusion of certain biological states, as per any filtering strategy[

15,

80].

Gene set curation and expression analysis. Gene sets representing canonical endocannabinoid receptors (

Cnr1, Cnr2, Gpr55), metabolic enzymes (

Dagla, Daglb, Gde1, Mgll, Napepld, Faah), and neuropeptides pertinent to hypothalamic classification (

Oxt, Avp, Crh, Sst, Trh) were defined based on established literature[

19,

81,

82,

83,

84]. To focus analyses on more robustly expressed genes and to mitigate noise from sparse detection, expression matrices were filtered to include only genes ranking above the 40th percentile of mean expression across all cells. For qualitative assessment of co-expression, gene expression was binarized based on detection status (expression > 0.5th percentile for each gene separately) within individual cells. Therefore, intersectional co-expression patterns among key gene sets could be visualized using

UpSet plots generated with the

UpSetR package[

80,

85]. UMAP was used to visualize high-dimensional cellular states in two dimensions, primarily using coordinates provided in the original datasets or recomputed as necessary[

15,

29,

78,

79,

80]. The expression patterns of specific genes and the aggregate expression of curated gene sets were visualized across developmental stages and cell clusters using Seurat’s

FeaturePlot function, optimizing parameters such as point size and transparency for clarity[

77].

Descriptive statistics and exploratory analysis. Quantitative summaries of gene expression, including mean, standard deviation, and quartiles, were calculated for the specified target genes at the developmental periods indicated. The

skimr package was used for descriptive statistics for numerical metadata and expression features, ensuring transparency regarding data distributions and completeness[

80].

In situ hybridization: Embryonic heads (E15.5) and extracted brains (P10, P21) were rapidly frozen on dry-ice in plastic moulds filled with optimal cutting medium (O.C.T; Sakura), and cryosectioned at 16-µm thickness on a Leica CM1860 cryostat microtome. Coronal sections containing the PVN were collected serially on SuperFrost+ glass slides (ThermoFisher), air-dried for 20 min, and stored at -80 °C until processing. Tissue sections were immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.05M phosphate buffered-saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 4 °C for 20 min, rinsed in PBS, and subsequently dehydrated in an ascending gradient of ethanol (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%, 5 min each). In situ hybridization was multiplexed according to the HCR v3.0 protocol for ‘generic sample on slide’ with probe sets combining Slc32a1, Crh, Trh, Oxt, Cnr1, Dagla, Daglb, and Mgll (all from Molecular Instruments). Sections were counterstained with Hoechst 33,342 (Sigma Aldrich) and mounted with Entellan (Merck). Sections with two or more colours from appropriately labelled hairpin combinations were imaged on an LSM880 confocal microscope (Zeiss; pinhole set to 1 airy unit, and minimal laser power [<5% per channel]; 20x/0.8 NA objective for survey images and Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 N.A. objective for high-resolution images), processed with the ZEN software (Zeiss), and compiled as multi-panel images in CorelDRAW 2022 (Corel Corp.).

Immunohistochemistry. Whole heads of mouse foetuses (E15.5) were immersion fixed overnight with 4% PFA in 0.05M PBS at 4 °C before cryoprotection in 30% sucrose in 0.05M PBS. P21 mice were transcardially perfused with 4% PFA in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4), with their brains removed and post-fixed at 4 °C overnight, before cryoprotection in 30% sucrose in 0.05M PBS. Tissues were rapidly frozen and cryosectioned on a Leica CM1860 cryostat at either 20 µm (E15.5) and collected on SuperFrost+ glass slides (Thermo Fisher) or 50 µm for free-floating labelling (P21). Next, sections were incubated with a blocking solution containing 5% normal donkey serum (NDS, Jackson ImmunoResearch), 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma) and 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS at room temperature for 1h to block non-specific binding. Tissues were subsequently exposed to a combination of primary antibodies (guinea pig anti-CB1R [Af530], 1:500, Nittobo Medical; goat anti-DAGLα [Af1080], 1:500, Nittobo Medical, and rabbit anti-oxytocin [AB911], 1:1,000; Merck Millipore) diluted in 2% NDS, 0.1% BSA, 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS at 4 °C for 72h. After extensive rinsing in PBS, appropriate combinations of secondary IgGs conjugated with carbocyanine (Cy)2, 3 or 5 (raised in donkey, 1:300, Jackson ImmunoResearch) were applied at 22-24 oC for 2h. Sections were counterstained with Hoechst 33,342 (Sigma Aldrich) to visualize nuclei. After extensive washing in PBS, sections were rinsed in distilled water, air-dried, and cover slipped with Entellan (in xylene, Sigma-Aldrich).

Figure 1.

Cnr1 mRNA expression in the adult mouse PVN. (

a-a2) Open-source in situ hybridization data from the Allen Brain Atlas (

https://portal.brain-map.org/) in the adult mouse PVN reveals glutamatergic (

Slc17a6+), but not GABAergic (

Slc32a1+) neurons, along with the accumulation of

Cnr1 mRNA. (

b-b2) Multiplexed in situ hybridization confirmed

Cnr1 mRNA expression in the PVN, at levels more pronounced than in neighboring regions, and

Trh+ neurons being particularly labelled (

closed vs.

open arrowheads).

Abbreviations: 3V, third ventricle; AHN, anterior hypothalamic nucleus; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus.

Scale bars = 350 µm (a-a

3), 200 µm (b), 50 µm (b

1), 20 µm (b

2).

Figure 1.

Cnr1 mRNA expression in the adult mouse PVN. (

a-a2) Open-source in situ hybridization data from the Allen Brain Atlas (

https://portal.brain-map.org/) in the adult mouse PVN reveals glutamatergic (

Slc17a6+), but not GABAergic (

Slc32a1+) neurons, along with the accumulation of

Cnr1 mRNA. (

b-b2) Multiplexed in situ hybridization confirmed

Cnr1 mRNA expression in the PVN, at levels more pronounced than in neighboring regions, and

Trh+ neurons being particularly labelled (

closed vs.

open arrowheads).

Abbreviations: 3V, third ventricle; AHN, anterior hypothalamic nucleus; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus.

Scale bars = 350 µm (a-a

3), 200 µm (b), 50 µm (b

1), 20 µm (b

2).

Figure 2.

Neuropeptide identifiers of the PVN. (a-a2) Multidimensional clustering based on neuropeptides revealed discrete magnocellular (mOXT, mAVP), and parvocellular cells, the latter containing Crh, Trh and Sst (pCRH, pTRH, pSST), across successive developmental stages in the PVN. Relative expression was color-coded for each gene analyzed (to the right).

Figure 2.

Neuropeptide identifiers of the PVN. (a-a2) Multidimensional clustering based on neuropeptides revealed discrete magnocellular (mOXT, mAVP), and parvocellular cells, the latter containing Crh, Trh and Sst (pCRH, pTRH, pSST), across successive developmental stages in the PVN. Relative expression was color-coded for each gene analyzed (to the right).

Figure 3.

Cannabinoid receptors in the PVN. (a-a2) UMAP representation of cannabinoid receptors identified Cnr1 as the dominant receptor in both magnocellular and parvocellular cells at all developmental stages analyzed, with minimal contributions from Cnr2 (a1) and Gpr55 (a2). Relative expression was color-coded for each gene analyzed (to the right). (b) UpSet plots showing gene enrichment and co-expression along brain development. Note the particular enrichment in mOXT and pTRH clusters (in blue), as compared to pCRH.

Figure 3.

Cannabinoid receptors in the PVN. (a-a2) UMAP representation of cannabinoid receptors identified Cnr1 as the dominant receptor in both magnocellular and parvocellular cells at all developmental stages analyzed, with minimal contributions from Cnr2 (a1) and Gpr55 (a2). Relative expression was color-coded for each gene analyzed (to the right). (b) UpSet plots showing gene enrichment and co-expression along brain development. Note the particular enrichment in mOXT and pTRH clusters (in blue), as compared to pCRH.

Figure 4.

Dagla/b and Mgll expression in the PVN. (a-a2) UMAP representation in developing neurons showed Dagla << Daglb until birth (b, in blue), and Mgll at all time points. Relative expression was color-coded (to the right) for each gene analyzed. (b) UpSet plots showing gene enrichment and co-expression along brain development for the genes analyzed.

Figure 4.

Dagla/b and Mgll expression in the PVN. (a-a2) UMAP representation in developing neurons showed Dagla << Daglb until birth (b, in blue), and Mgll at all time points. Relative expression was color-coded (to the right) for each gene analyzed. (b) UpSet plots showing gene enrichment and co-expression along brain development for the genes analyzed.

Figure 5.

Napepld, Gde1, and Faah expression in the PVN. (a-a2) UMAP representation of Napepld, Gde1, and Faah expression in neurons populating the PVN. Relative expression was color-coded (to the right) for each gene analyzed. (b) UpSet plots showing gene enrichment and co-expression along brain development for the genes analyzed.

Figure 5.

Napepld, Gde1, and Faah expression in the PVN. (a-a2) UMAP representation of Napepld, Gde1, and Faah expression in neurons populating the PVN. Relative expression was color-coded (to the right) for each gene analyzed. (b) UpSet plots showing gene enrichment and co-expression along brain development for the genes analyzed.

Figure 6.

Cell-type-specific localization of Dagla, Daglb, Magll, and Cnr1 by in situ hybrization. (a-a4) Already at E15.5, distinct neuronal populations expressed either Cnr1 or Daglb, or both. (b) At postnatal day 10 (P10), both Cnr1 and Daglb expression were maintained. (c-e1) At P21, PVN neurons continued to express Cnr1, Daglb, and Mgll, along with noticeable levels of Dagla (d2). (f-g2) Immunohistochemistry revealed the focal accumulation of CB1Rs in the PVN at E15.5, which remained unchanged until P21 (arrowheads, f1 vs. g1). DAGLα dominated at P21, when it frequently apposed CB1Rs in the somata and processes of, e.g., mOXT neurons (arrowheads, g2). Scale bars = 50 µm (a,a1,b,c,d,e,f,g), 20 µm (g1), 10 µm (a2,a3,a4,b1,b2,c1,d1,d2,e1), 5 µm (f1,g2).

Figure 6.

Cell-type-specific localization of Dagla, Daglb, Magll, and Cnr1 by in situ hybrization. (a-a4) Already at E15.5, distinct neuronal populations expressed either Cnr1 or Daglb, or both. (b) At postnatal day 10 (P10), both Cnr1 and Daglb expression were maintained. (c-e1) At P21, PVN neurons continued to express Cnr1, Daglb, and Mgll, along with noticeable levels of Dagla (d2). (f-g2) Immunohistochemistry revealed the focal accumulation of CB1Rs in the PVN at E15.5, which remained unchanged until P21 (arrowheads, f1 vs. g1). DAGLα dominated at P21, when it frequently apposed CB1Rs in the somata and processes of, e.g., mOXT neurons (arrowheads, g2). Scale bars = 50 µm (a,a1,b,c,d,e,f,g), 20 µm (g1), 10 µm (a2,a3,a4,b1,b2,c1,d1,d2,e1), 5 µm (f1,g2).

Figure 7.

Cannabinoid receptors and enzymes in astrocytes of the adult PVN. (a) Gene set used to identify astrocytes. (b-b2) Cannabinoid receptors (b), but not the machinery to control the bioavailability of 2-AG, were lacking in astrocytes. Relative expression was color-coded for each gene analyzed (to the right). (c) UpSet plots for gene enrichment in PVN astrocytes. Note the higher reliance on 2-AG signalling as compared to AEA (blue vs. green). (d) In situ hybridization confirmed the lack of Cnr1 in Gfap+ astrocytes (arrowheads indicate Gfap+/Cnr1- astrocytes vs. open arrowheads denoting Gfap-/Cnr1+ cells, presumed neurons). (d1) Gfap+ astrocytes contained Dagla mRNA, even if at low abundance (arrowheads). Scale bar = 5 µm (d1).

Figure 7.

Cannabinoid receptors and enzymes in astrocytes of the adult PVN. (a) Gene set used to identify astrocytes. (b-b2) Cannabinoid receptors (b), but not the machinery to control the bioavailability of 2-AG, were lacking in astrocytes. Relative expression was color-coded for each gene analyzed (to the right). (c) UpSet plots for gene enrichment in PVN astrocytes. Note the higher reliance on 2-AG signalling as compared to AEA (blue vs. green). (d) In situ hybridization confirmed the lack of Cnr1 in Gfap+ astrocytes (arrowheads indicate Gfap+/Cnr1- astrocytes vs. open arrowheads denoting Gfap-/Cnr1+ cells, presumed neurons). (d1) Gfap+ astrocytes contained Dagla mRNA, even if at low abundance (arrowheads). Scale bar = 5 µm (d1).