Submitted:

25 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Treatments and Tissue Collection

2.2. Microarray and Data Processing

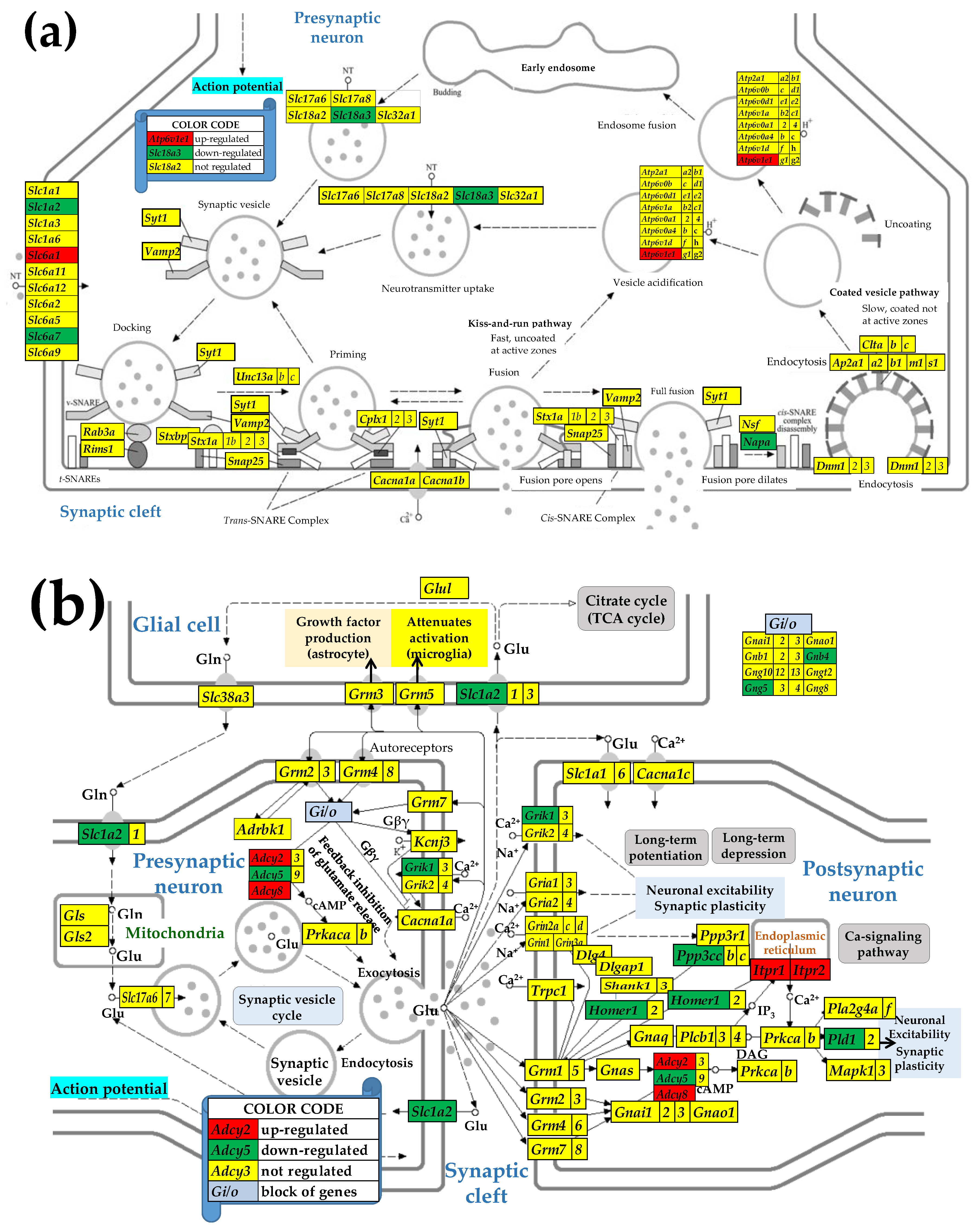

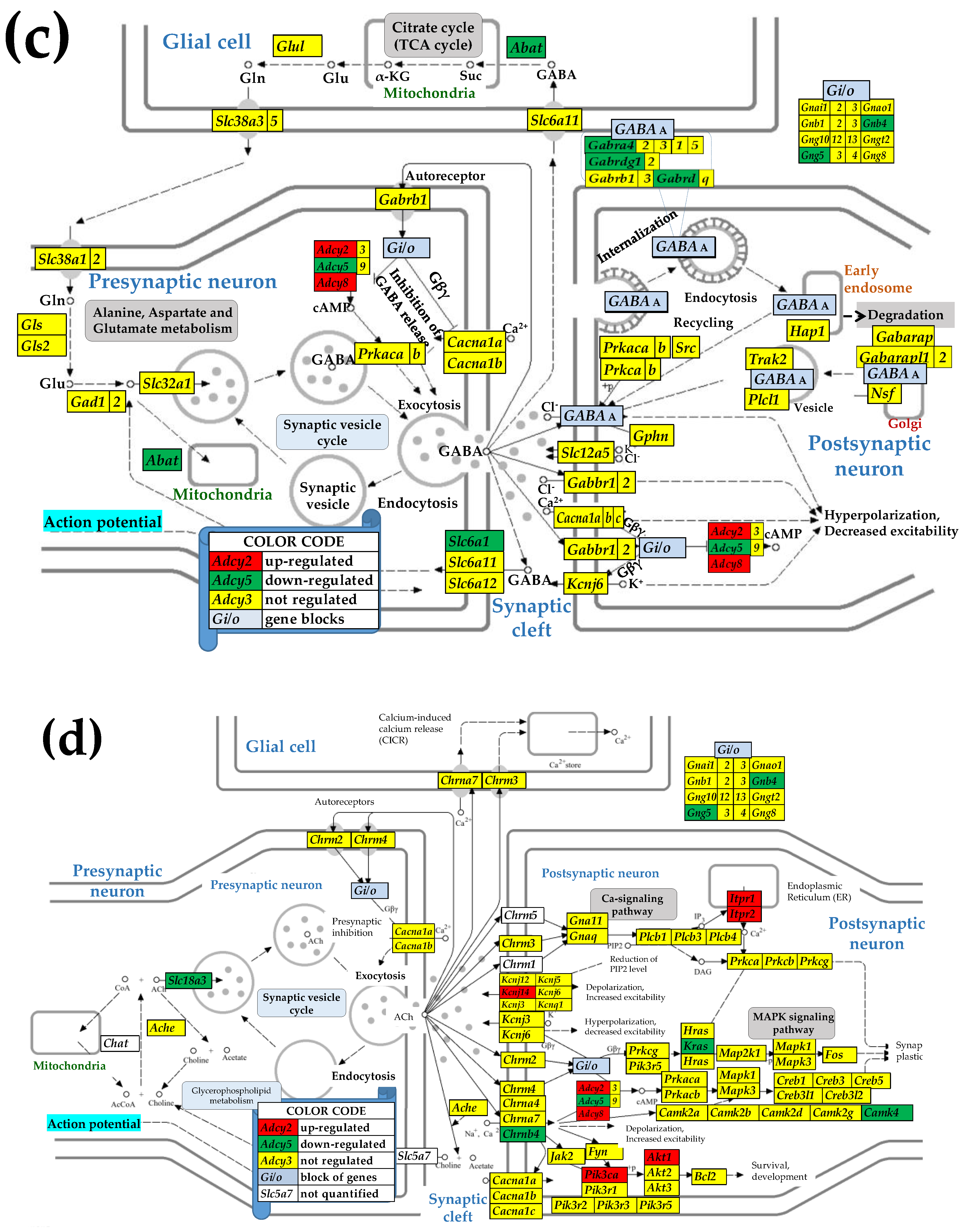

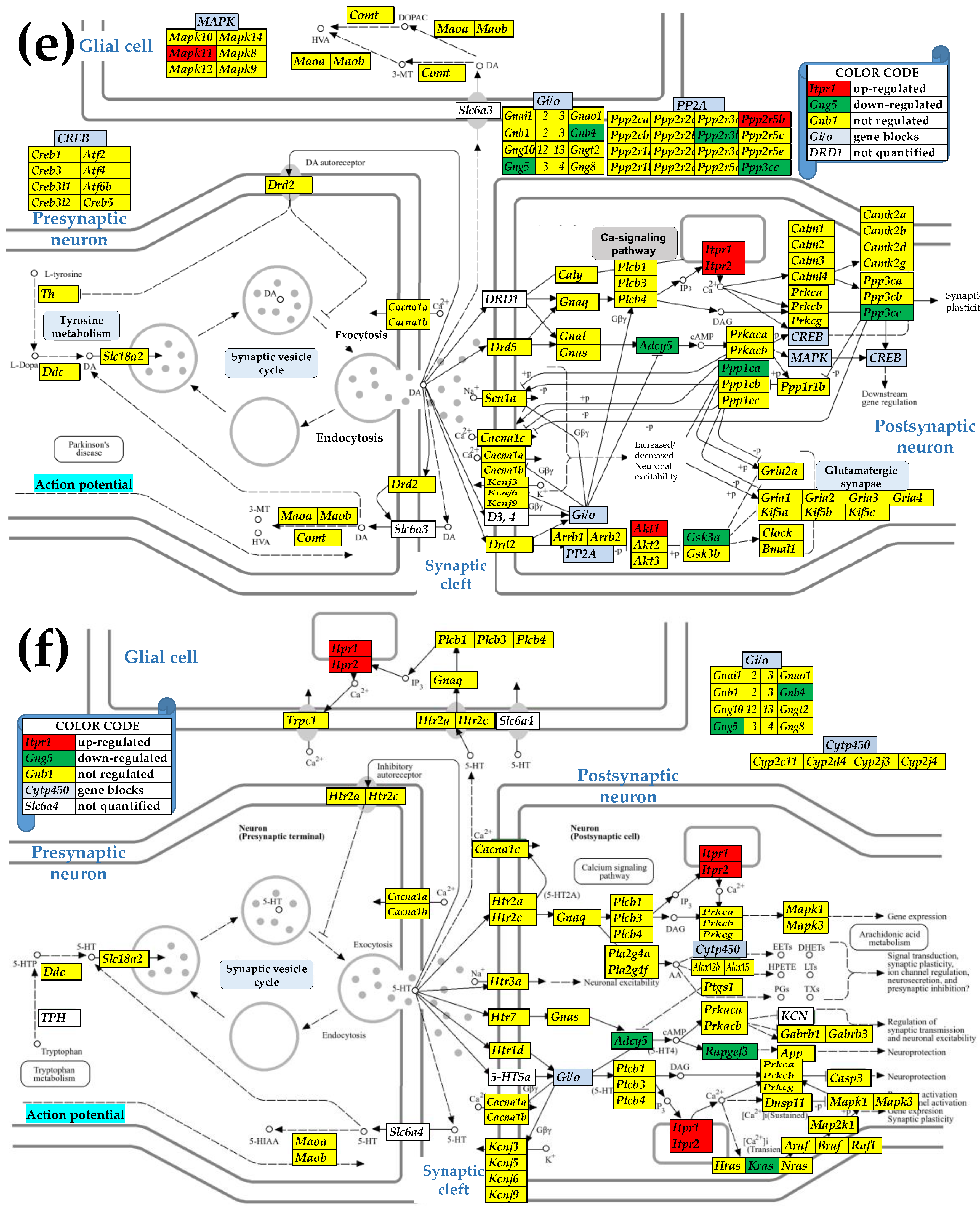

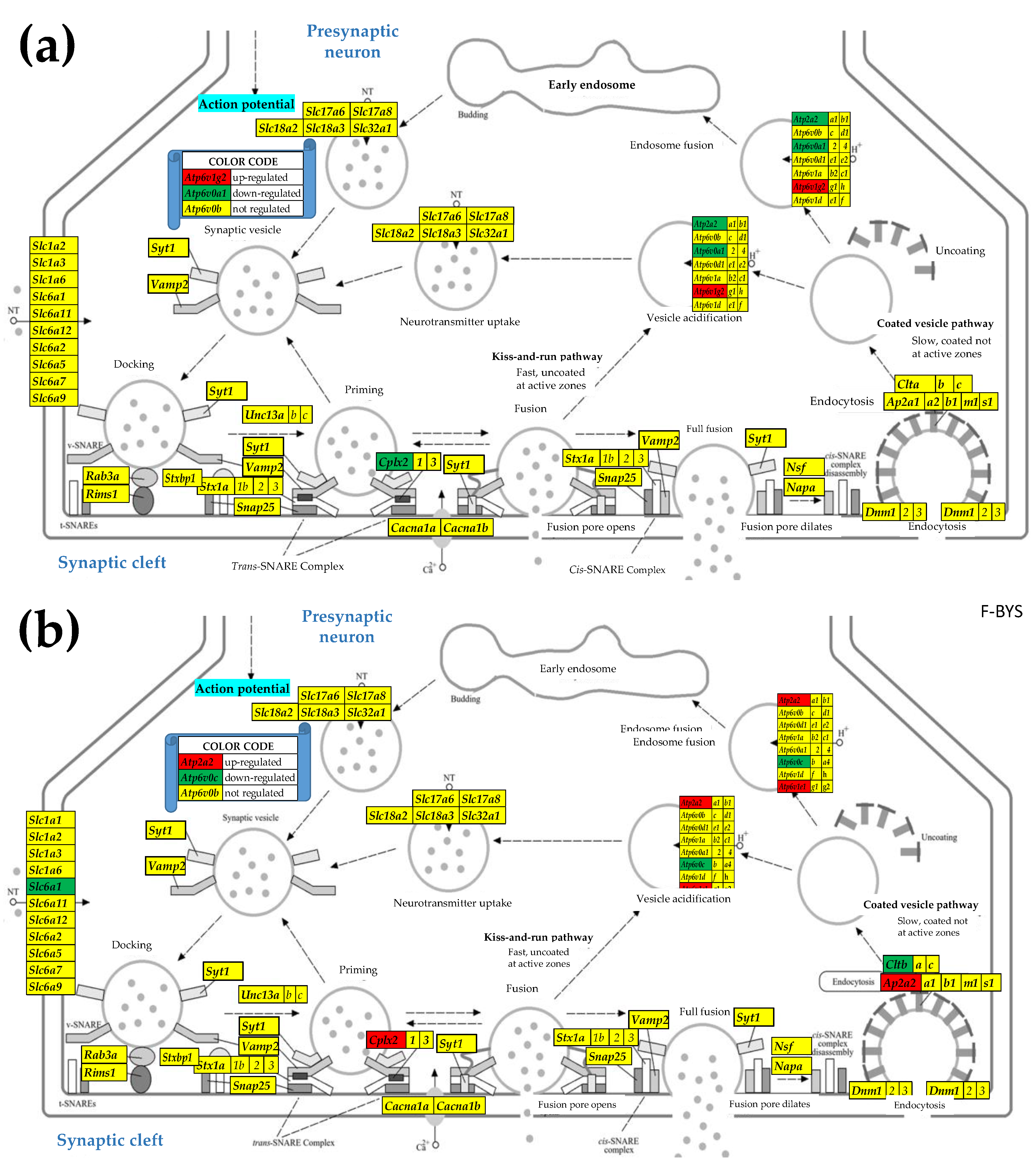

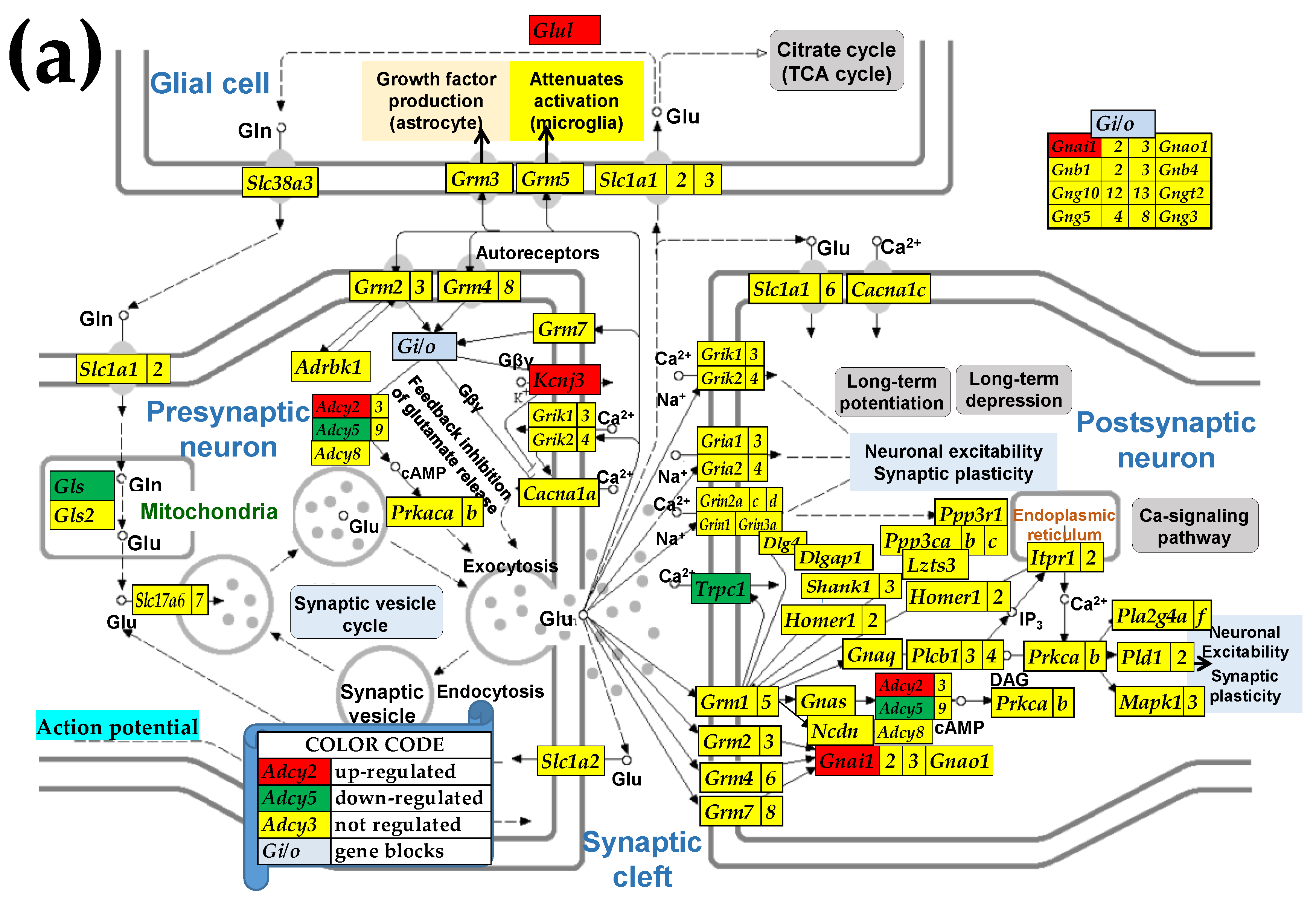

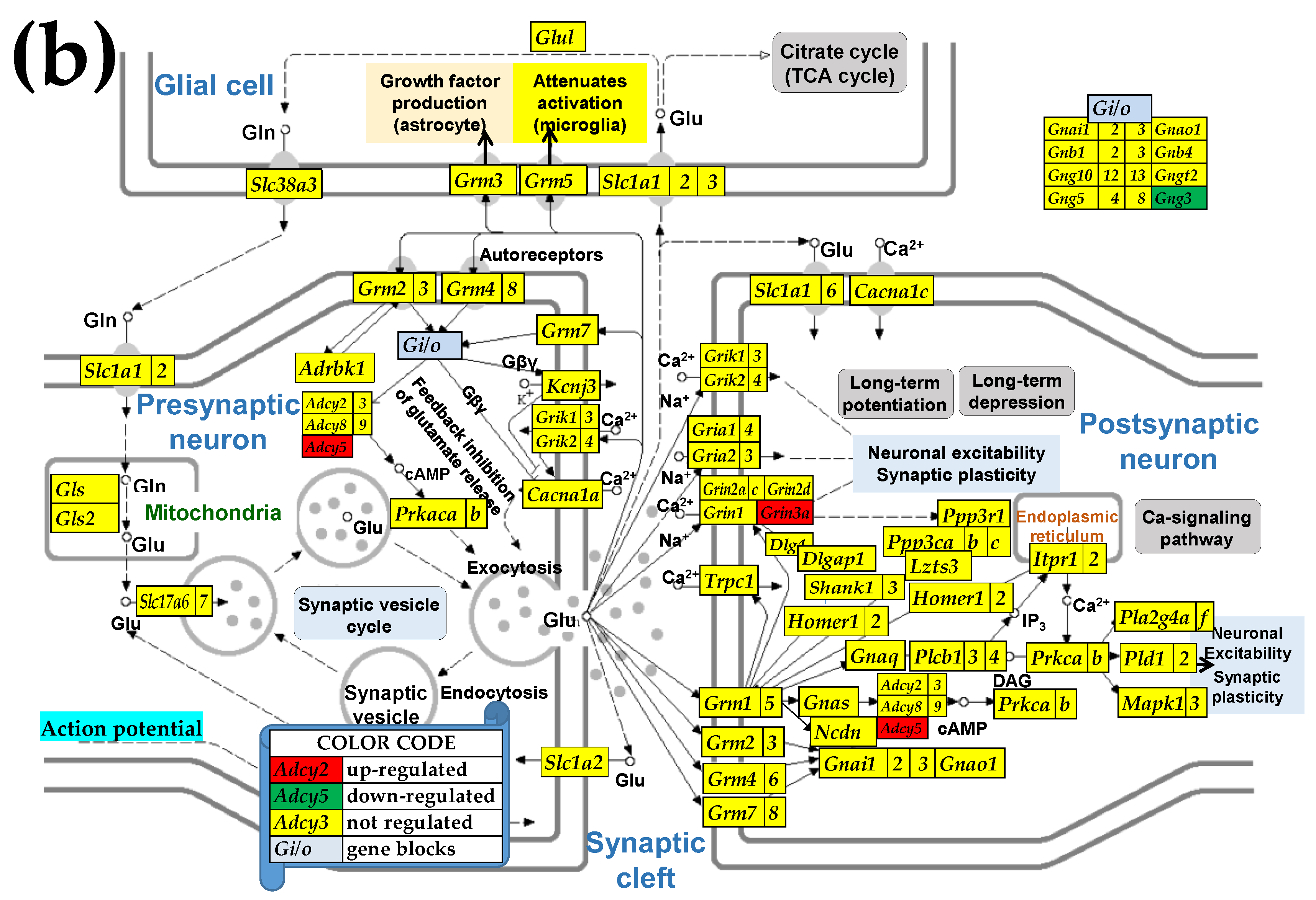

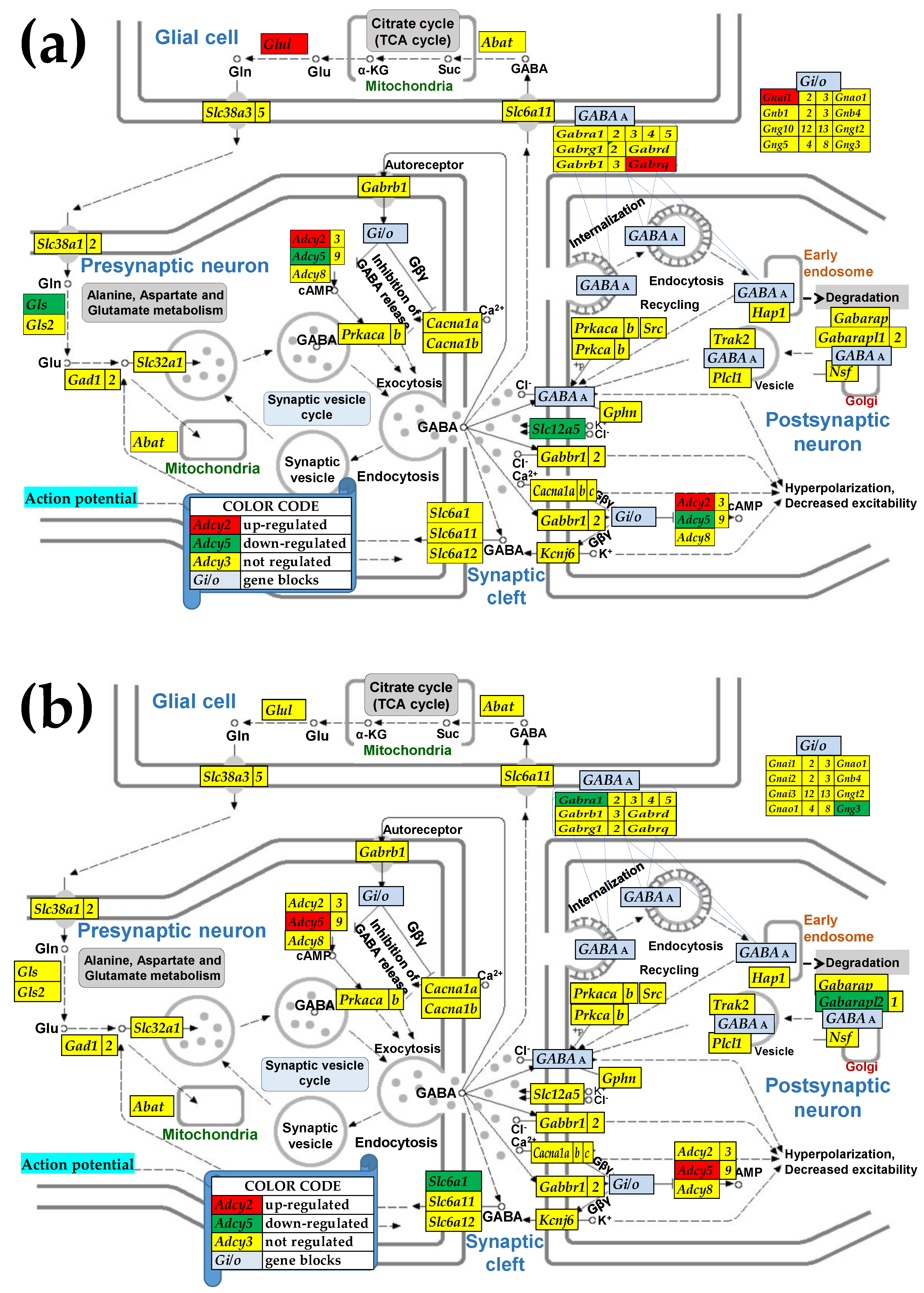

2.3. KEGG-Constructed Functional Neurotransmission Pathways

3. Results

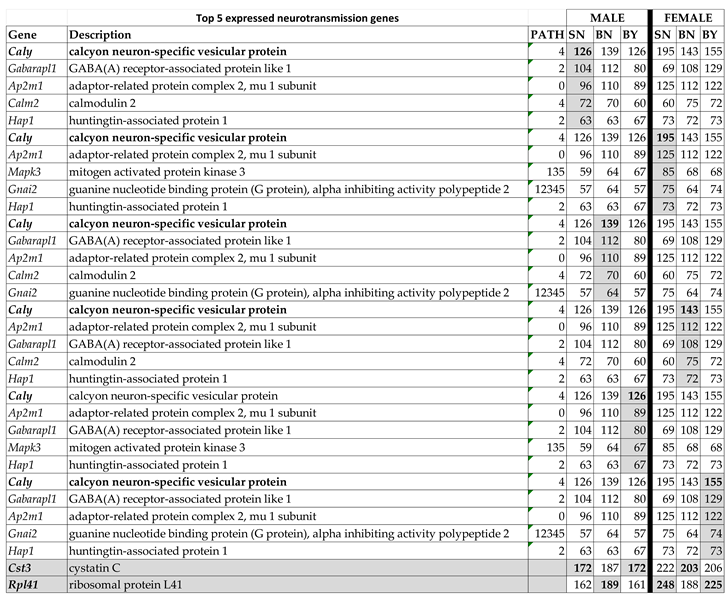

3.1. There Is Little Sex Dichotomy of the Most Highly Expressed Neurotransmission Genes

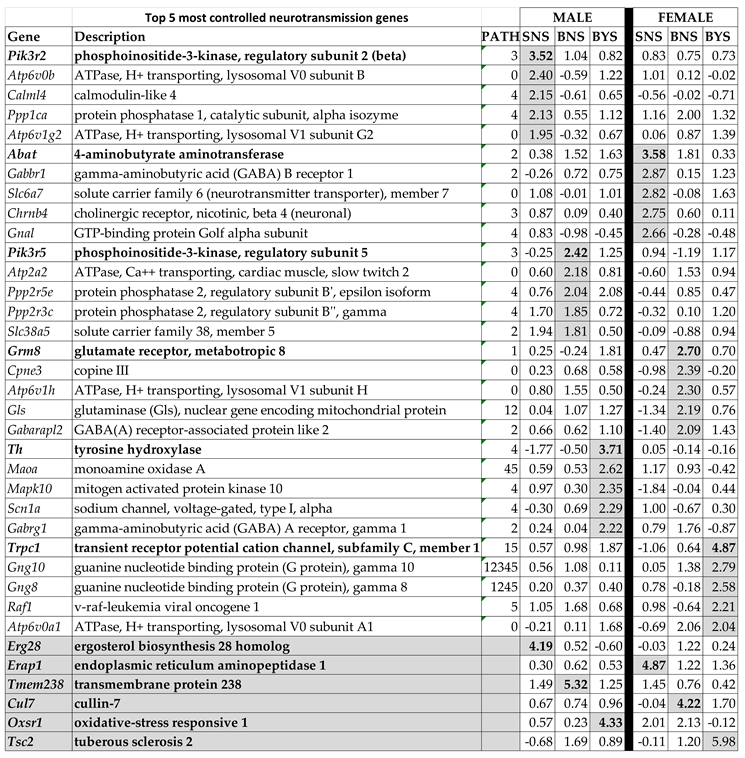

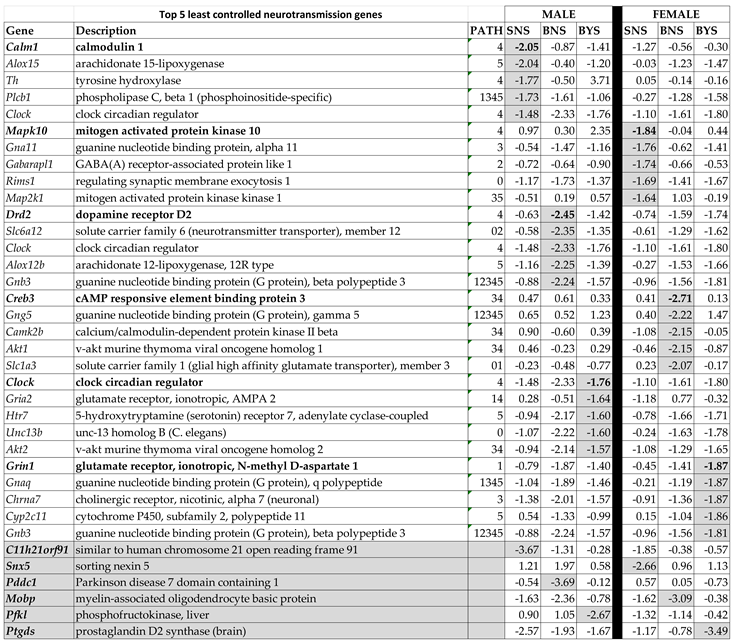

3.2. Sex Dichotomy in the Expression Control in the Three Conditions and Control Alteration by IS

3.3. Sex Differences in the Unaltered State of the Six Neurotransmission Pathways

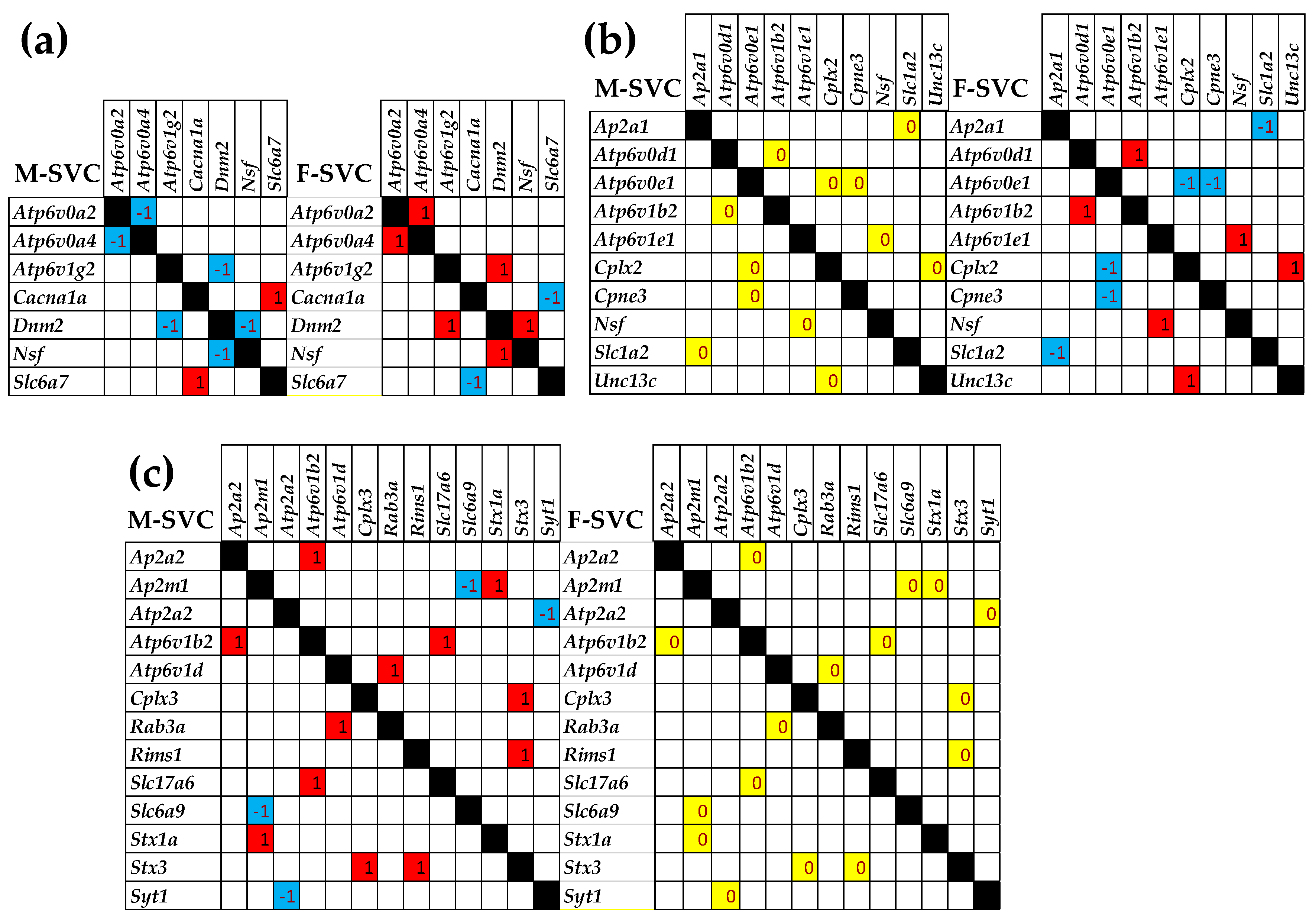

3.4. Sex Differences Between the Significantly Regulated SVC Genes in the PVN by the Induction of Spasms in the Betamethasone-Primed Rats

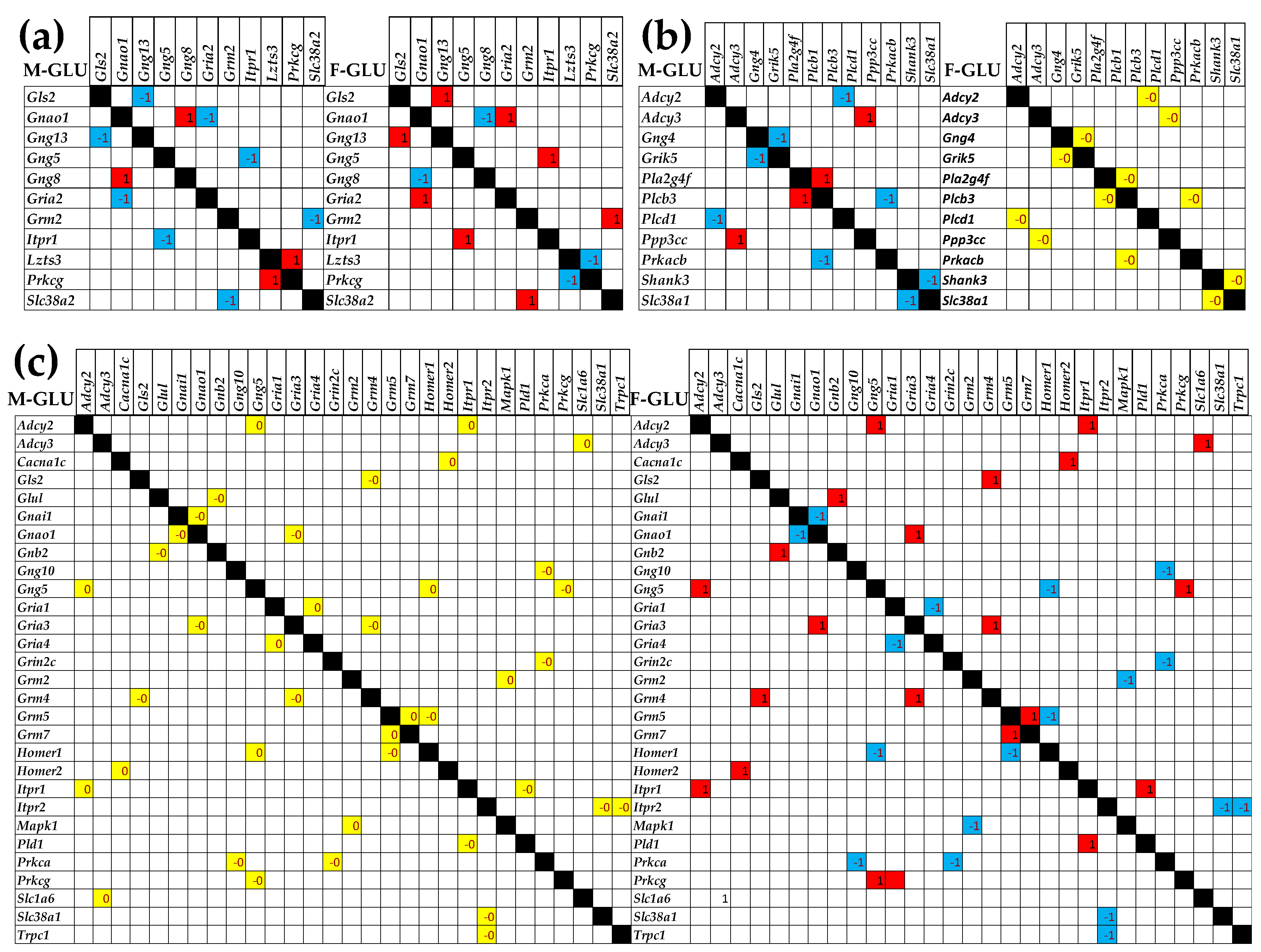

3.5. Sex Differences Between the Significantly Regulated GLU Genes in the PVN by the Induction of Infantile Spasms in the Betamethasone-Primed Rats

3.6. Sex Differences Between the Significantly Regulated GABA Genes in the PVN by the Induction of Infantile Spasms in the Betamethasone-Primed Rats

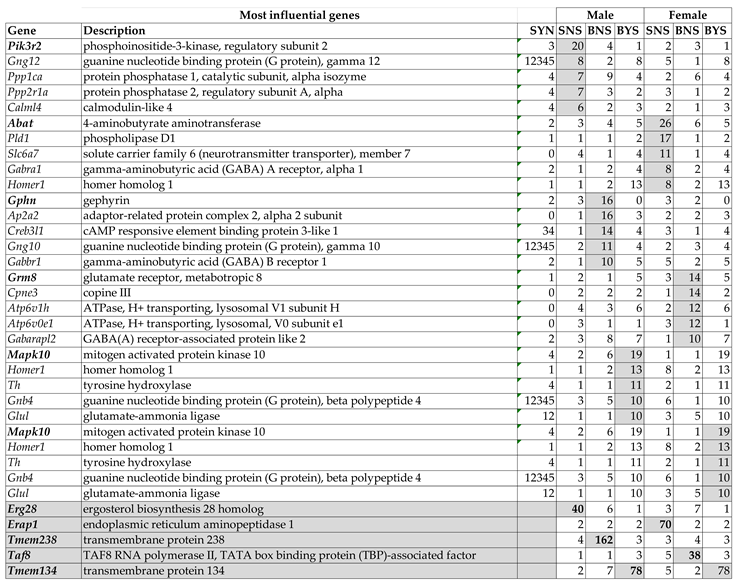

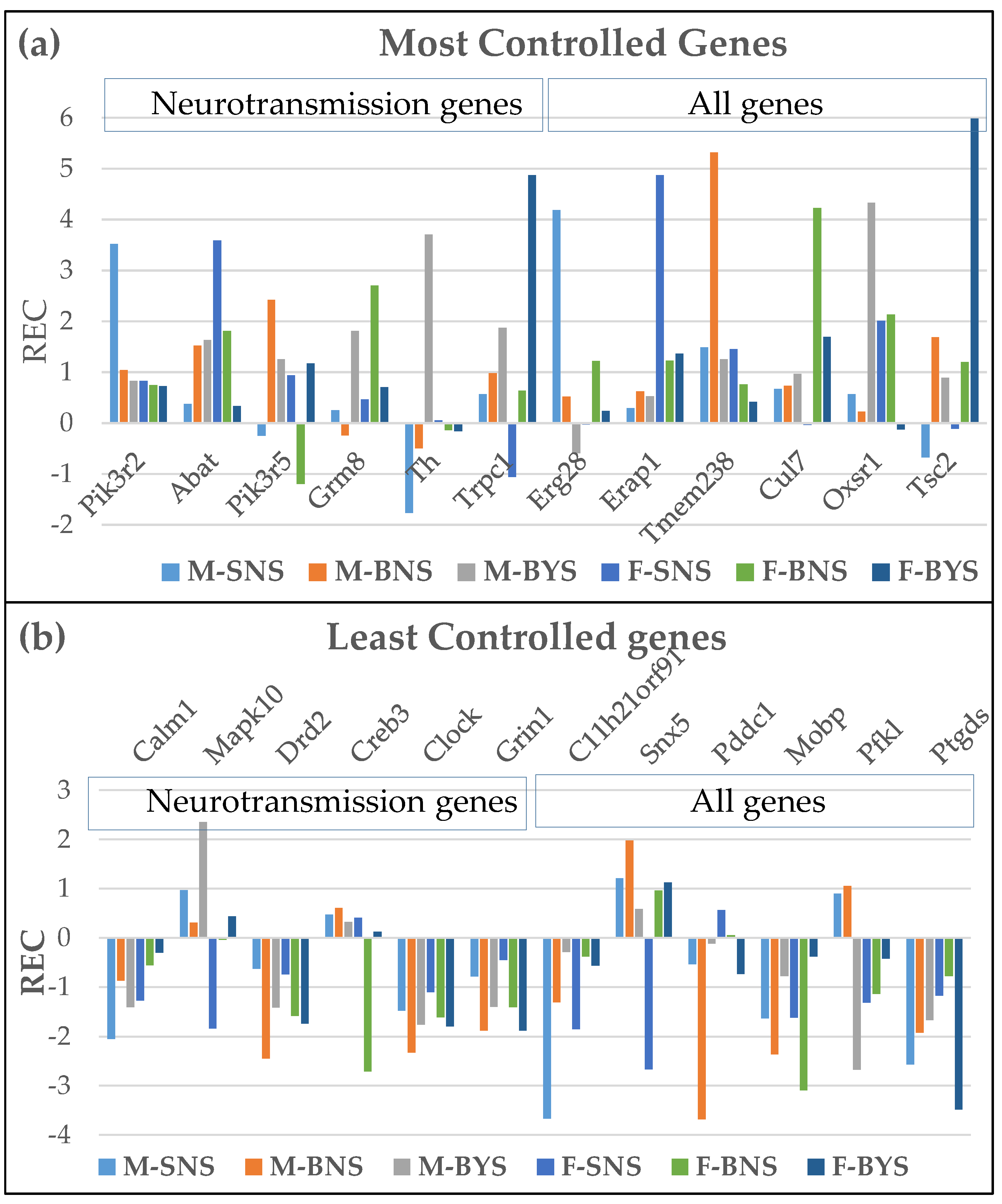

3.7. Sex Dichotomy of the Genes’ Transcriptomic Networks

3.8. Sex Dichotomy of the Genes’ Hierarchy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Synaptic vesicle cycle. Available on line at: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?rno04721. Accessed on: 12/12/2024.

- Glutamatergic synapse. Available at https://www.genome.jp/pathway/rno04724. Access on: 12/12/2024.

- GABAergic synapse. Available at: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?rno04727. Accessed on: 12/12/2024.

- Cholinergic synapse. Available at: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?rno04725. Accessed on: 12/12/2024.

- Dopaminergic synapse. Available at: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?rno04728. Accessed on: 12/12/2024.

- Serotonergic synapse. Available at: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?rno04726. Accessed on: 12/12/2024.

- Velíšek, L.; Jehle, K.; Asche, S.; Velíšková, J. Model of infantile spasms induced by N-methyl-D-aspartic acid in prenatally impaired brain. Ann Neurol 2007, 61, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Chachua, T.; Goletiani, C.; Sidyelyeva, G.; Veliskova, J.; Velisek, L. Prenatal corticosteroids modify glutamatergic and GABAergic synapse genomic fabric: insights from a novel animal model of infantile spasms. J Neuroendocrinol 2013, 25, 964–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Chachua, T.; Iacobas, S.; Benson, M.J.; Borges, K.; Veliskova, J.; Velisek, L. ACTH and PMX53 recover synaptic transcriptome alterations in a rat model of infantile spasms. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Velisek, L. Regeneration of neurotransmission transcriptome in a model of epileptic encephalopathy after antiinflammatory treatment. Neural Regen Res 2018, 13, 1715–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrachovy, R.A. West's syndrome (infantile spasms). Clinical description and diagnosis. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2002, 497, 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dulac, O.; Soufflet, C.; Chiron, C.; Kaminska, A. What is West syndrome? Int Rev Neurobiol 2002, 49, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hrachovy, R.A.; Frost, J.D., Jr. Infantile spasms. Handbook of clinical neurology 2013, 111, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavone, P.; Striano, P.; Falsaperla, R.; Pavone, L.; Ruggieri, M. Infantile spasms syndrome, West syndrome and related phenotypes: what we know in 2013. Brain Dev 2014, 36, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, M.T.; Weiss, S.K.; Adams-Webber, T.; Ashwal, S.; Stephens, D.; Ballaban-Gill, K.; Baram, T.Z.; Duchowny, M.; Hirtz, D.; Pellock, J.M.; et al. Practice parameter: medical treatment of infantile spasms: report of the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society. Neurology 2004, 62, 1668–1681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Go, C.Y.; Mackay, M.T.; Weiss, S.K.; Stephens, D.; Adams-Webber, T.; Ashwal, S.; Snead, O.C., 3rd; Child Neurology, S.; American Academy of, N. Evidence-based guideline update: medical treatment of infantile spasms. Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology 2012, 78, 1974–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riikonen, R. The latest on infantile spasms. Curr Opin Neurol 2005, 18, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lux, A.L.; Edwards, S.W.; Hancock, E.; Johnson, A.L.; Kennedy, C.R.; Newton, R.W.; O'Callaghan, F.J.; Verity, C.M.; Osborne, J.P. The United Kingdom Infantile Spasms Study (UKISS) comparing hormone treatment with vigabatrin on developmental and epilepsy outcomes to age 14 months: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 2005, 4, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikonen, R. Long-term outcome of patients with West syndrome. Brain Dev 2001, 23, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthvigsson, P.; Olafsson, E.; Sigurthardottir, S.; Hauser, W.A. Epidemiologic features of infantile spasms in Iceland. Epilepsia 1994, 35, 802–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harini, C.; Nagarajan, E.; Bergin, A.M.; Pearl, P.; Loddenkemper, T.; Takeoka, M.; Morrison, P.F.; Coulter, D.; Harappanahally, G.; Marti, C.; et al. Mortality in infantile spasms: A hospital-based study. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, E.C.; Osborne, J.P.; Edwards, S.W. Treatment of infantile spasms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013, CD001770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachua, T.; Yum, M.-S.; Velíšková, J.; Velíšek, L. Validation of the rat model of cryptogenic infantile spasms. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 1666–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mareš, P.; Velíšek, L. N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-induced seizures in developing rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 1992, 65, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, M.S.; Chachua, T.; Velíšková, J.; Velíšek, L. Prenatal stress promotes development of spasms in infant rats. Epilepsia 2012, 53, e46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Watabe, A.M.; Kato, F. Enhanced long-term potentiation in mature rats in a model of epileptic spasms with betamethasone-priming and postnatal N-methyl-d-aspartate administration. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.; Yi, M.H.; Pandit, S.; Park, J.B.; Kwon, H.H.; Zhang, E.; Kim, S.; Shin, N.; Kim, E.; Lee, Y.H.; et al. Altered expression of KCC2 in GABAergic interneuron contributes prenatal stress-induced epileptic spasms in infant rat. Neurochemistry international 2016, 97, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janicot, R.; Shao, L.R.; Stafstrom, C.E. 2-deoxyglucose and beta-hydroxybutyrate fail to attenuate seizures in the betamethasone-NMDA model of infantile spasms. Epilepsia Open 2022, 7, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, B.; Murphy, D.; Japundzic-Zigon, N. The Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus in Control of Blood Pressure and Blood Pressure Variability. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 858941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velíšková, J. Sex matters in epilepsy. In Developmental Epilepsy: From Clinical Medicine to Neurobiological Mechanisms, Stafstrom, C.E., Velíšek, L., Ed.; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2019; pp. 387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, P.O.; Bergson, C.; Undie, A.S.; Goldman-Rakic, P.S.; Lidow, M.S. Up-regulation of the D1 dopamine receptor-interacting protein, calcyon, in patients with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003, 60, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.M.; Park, D.; Han, J.K.; Jang, J.I.; Park, J.Y.; Hwang, E.M.; Seok, H.; Chang, S. Calcyon forms a novel ternary complex with dopamine D1 receptor through PSD-95 protein and plays a role in dopamine receptor internalization. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 31813–31822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Huang, W.; Yang, J.; Wen, Z.; Geng, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Systematic identification of hepatitis E virus ORF2 interactome reveals that TMEM134 engages in ORF2-mediated NF-kappaB pathway. Virus Res 2017, 228, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, M.S.; Blum, K.; Oscar-Berman, M.; Braverman, E.R. Low dopamine function in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: should genotyping signify early diagnosis in children? Postgrad Med 2014, 126, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, M.V.; Gulledge, A.T. Serotonin and prefrontal cortex function: neurons, networks, and circuits. Mol Neurobiol 2011, 44, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, S. Serotonergic modulation of Neural activities in the entorhinal cortex. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 2012, 4, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Seyedabadi, M.; Fakhfouri, G.; Ramezani, V.; Mehr, S.E.; Rahimian, R. The role of serotonin in memory: interactions with neurotransmitters and downstream signaling. Exp Brain Res 2014, 232, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J. The role of steroid hormones in the sexual differentiation of the human brain. J Neuroendocrinol 2022, 34, e13050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutia, C.A.; Christian-Hinman, C.A. Mechanisms linking neurological disorders with reproductive endocrine dysfunction: Insights from epilepsy research. Front Neuroendocrinol 2023, 71, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akman, O.; Moshe, S.L.; Galanopoulou, A.S. Sex-specific consequences of early life seizures. Neurobiol Dis 2014, 72 Pt B, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Iacobas, D.A. . Analyzing the Cytoskeletal Transcriptome: Sex Differences in Rat Hypothalamus. In: Dermietzel, R. (eds) The Cytoskeleton. Neuromethods 2013, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Velíšková, J.; Iacobas, D.; Iacobas, S.; Sidyelyeva, G.; Chachua, T.; Velíšek, L. Oestradiol Regulates Neuropeptide Y Release and Gene Coupling with the GABAergic and Glutamatergic Synapses in the Adult Female Rat Dentate Gyrus. J Neuroendocrinol 2015, 27, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J. The Sexual Differentiation of the Human Brain: Role of Sex Hormones Versus Sex Chromosomes. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2019, 43, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sex differences in the synaptic genomic fabrics of the rat hypothalamic paraventricular node. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE123721. Accessed on 01/04/2025.

- Prenatal betamethasone remodels the genomic fabrics of the synaptic transmission in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Available on line at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE124613. Accessed on 01/04/2025.

- Remodeling of synaptic transmission genomic fabrics in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of a rat model of autism. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE128091. Accessed on: 01/04/2025.

- Iacobas, D.A. The Genomic Fabric Perspective on the Transcriptome Between Universal Quantifiers and Personalized Genomic Medicine. Biol Theory 2016, 11, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Lee, P.R.; Cohen, J.E.; Fields, R.D. Coordinated Activity of Transcriptional Networks Responding to the Pattern of Action Potential Firing in Neurons. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, R.J. Sex-steroid actions on neurotransmission. Curr Opin Neurol. 1998 11(6):667-71. [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.C.; Kumar, A. Sex, senescence, senolytics, and cognition. Front Aging Neurosci. 2025 4;17:1555872. [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, D.; Purves-Tyson, T.D.; Allen, K.M.; Weickert, C.S. Impacts of stress and sex hormones on dopamine neurotransmission in the adolescent brain. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014; 231(8):1581-99. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Ede, N.; Iacobas, D.A. The Gene Master Regulators (GMR) Approach Provides Legitimate Targets for Personalized, Time-Sensitive Cancer Gene Therapy. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.; Cheng, B.; Sharma, D.R.; Yadav, S.; Stempinski, E.S.; Mamtani, S.; Shah, E.; Deo, A.; Acherjee, T.; Thomas, T.; et al. PPAR-gamma activation enhances myelination and neurological recovery in premature rabbits with intraventricular hemorrhage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M. The KEGG database. Novartis Found Symp. 2002;247:91-101.

- Iacobas, S.; Iacobas, D.A. Astrocyte proximity modulates the myelination gene fabric of oligodendrocytes. Neuron Glia Biol. 2010; 6(3):157-69. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Thomas, N.M.; Iacobas, D.A. Plasticity of the myelination genomic fabric. Mol Genet Genomics. 2012; 287(3):237-46. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Stout, R.F.; Spray, D.C. Cellular Environment Remodels the Genomic Fabrics of Functional Pathways in Astrocytes. Genes (Basel). 2020; 11(5):520. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng J, Bai, S.; Yu, H.; He, H.; Fan, C.; Hao, Y.; Guan, Y. A PIK3R2 Mutation in Familial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy as a Possible Pathogenic Variant. Front Genet. 2021; 12:596709. [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Jiao, X.; Li, H. MicroRNA-126-3P targets PIK3R2 to ameliorate autophagy and apoptosis of cortex in hypoxia-reoxygenation treated neonatal rats. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2023; 69(12):210-217. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wei, Z.H.; Liu, C.; Li, G.Y.; Qiao, X.Z.; Gan, Y.J.; Zhang, C.C.; Deng, Y.C. Genetic variations in GABA metabolism and epilepsy. Seizure. 2022; 101:22-29. [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Qin, H.; Liu, L.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, Y.; Yu, X.; Su, C. GABA regulates metabolic reprogramming to mediate the development of brain metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025; 44(1):61. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhen, Y.; Ban, W.; Zhu, G. Molecular profiling of a rat model of vascular dementia: Evidences from proteomics, metabolomics and experimental validations. Brain Res. 2025; 1846:149254. Epub 2024 Sep 26. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, G.; Yang, C. Transcriptomic and network analysis identifies shared pathways across Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Brain Res. 2025; 1854:149548. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Kilic-Berkmen, G.; Scorr, L.M.; McKay, L.; Thayani, M.; Donsante, Y.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Norris, S.A.; Wright, L.; Klein, C.; Feuerstein, J.S. et al. Sex Differences in Dystonia. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2024; 11(8):973-982. [CrossRef]

- Abeledo-Machado, A.; Peña-Zanoni, M.; Bornancini, D.; Camilletti, M.A.; Faraoni, E.Y.; Marcial, A.; Rulli, S.; Alhenc-Gelas, F.; Díaz-Torga, G.S. Sex-specific Regulation of Prolactin Secretion by Pituitary Bradykinin Receptors. Endocrinology. 2022; 163(9):bqac108ors. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.S.; Diaguarachchige De Silva, K.H.; Hashemi, A.; Duncan, R.E.; Grapentine, S.; Bakovic, M.; Lu, R. Transcription factor CREB3 is a potent regulator of high-fat diet-induced obesity and energy metabolism. Int J Obes (Lond). 2022; 46(8):1446-1455. [CrossRef]

- Deluca, A.; Bascom, B.; Key Planas, D.A.; Kocher, M.A.; Torres, M.; Arbeitman, M.N. Contribution of neurons that express fruitless and Clock transcription factors to behavioral rhythms and courtship. iScience. 2025; 28(3):112037. [CrossRef]

- Towers, E.B.; Kilgore, M.; Bakhti-Suroosh, A.; Pidaparthi, L.; Williams, I.L.; Abel, J.M.; Lynch, W.J. Sex differences in the neuroadaptations associated with incubated cocaine-craving: A focus on the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. Front Behav Neurosci. 2023; 16:1027310. [CrossRef]

- Eskow Jaunarajs, K.L.; Scarduzio, M.; Ehrlich, M.E.; McMahon, L.L.; Standaert, D.G. Diverse Mechanisms Lead to Common Dysfunction of Striatal Cholinergic Interneurons in Distinct Genetic Mouse Models of Dystonia. J Neurosci. 2019; 39(36):7195-7205. [CrossRef]

- Daubner, S.C.; Le, T.; Wang, S. Tyrosine hydroxylase and regulation of dopamine synthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys 2011, 508, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Byun, J.; Kang, H.C.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Kwon, Y.J.; Cho, Y.Y. Karyoptosis as a novel type of UVB-induced regulated cell death. Free Radic Res 2024, 58, 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Tang, J.; Chen, K.; Wu, M.; Wu, X.; Qiu, X. A transcriptomics-based analysis of mechanisms involved in the sex-dependent effects of diazepam on zebrafish. Aquat Toxicol 2024, 275, 107063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yotova, A.Y.; Li, L.L.; O'Leary, A.; Tegeder, I.; Reif, A.; Courtney, M.J.; Slattery, D.A.; Freudenberg, F. Synaptic proteome perturbations after maternal immune activation: Identification of embryonic and adult hippocampal changes. Brain Behav Immun 2024, 121, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wang, Y.; He, F.; Chen, C.; Wu, L.W.; Yang, L.F.; Ma, Y.P.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Z.Q.; Chen, C.; et al. Novel West syndrome candidate genes in a Chinese cohort. CNS Neurosci Ther 2018, 24, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, A.L.; Hyde, T.M.; Deep-Soboslay, A.; Kleinman, J.E.; Sodhi, M.S. Sex differences in glutamate receptor gene expression in major depression and suicide. Mol Psychiatry 2015, 20, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipnis, P.A.; Sullivan, B.J.; Kadam, S.D. Sex-Dependent Signaling Pathways Underlying Seizure Susceptibility and the Role of Chloride Cotransporters. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philibert, C.E.; Garcia-Marcos, M. Smooth operator(s): dialing up and down neurotransmitter responses by G-protein regulators. Trends Cell Biol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Hernandez, A.J.; Munguba, H.; Levitz, J. Emerging modes of regulation of neuromodulatory G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Neurosci 2024, 47, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, M.J.; Lipp, P.; Bootman, M.D. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2000, 1, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Suadicani, S.O.; Spray, D.C.; Scemes, E. A stochastic two-dimensional model of intercellular Ca2+ wave spread in glia. Biophys J 2006, 90, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharyan, R.; Atshemyan, S.; Boyajyan, A. Risk and protective effects of the complexin-2 gene and gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia. Recent Adv DNA Gene Seq. 2014; 8(1):30-4. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.M.; Loke, S.; Wrucke, B.; Engelhardt, A.; Demis, S.; O'Reilly, K.; Hess, E.; Wickman, K.; Hearing, M.C. Suppression of pyramidal neuron G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel signaling impairs prelimbic cortical function and underlies stress-induced deficits in cognitive flexibility in male, but not female, mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021; 46(12):2158-2169. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Kou, H.; Demy, D.L.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Wen, Z.; Herbomel, P.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J. The different roles of V-ATPase a subunits in phagocytosis/endocytosis and autophagy. Autophagy. 2024; 20(10):2297-2313. [CrossRef]

- Prinslow, E.A.; Stepien, K.P.; Pan, Y.Z.; Xu, J.; Rizo, J. Multiple factors maintain assembled trans-SNARE complexes in the presence of NSF and alphaSNAP. Elife 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ma, L.; Yuan, J.; Huang, Y.; Ban, Y.; Zhang, P.; Tan, D.; Liang, M.; Li, Z.; Gong, C.; Xu, T. et al. GLS2 reduces the occurrence of epilepsy by affecting mitophagy function in mouse hippocampal neurons. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2024; 30(10):e70036. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, M.; Hebert, L.P.; Dugast, E.; Lardeux, V.; Letort, K.; Thiriet, N.; Belnoue, L.; Balado, E.; Solinas, M.; Belujon, P. Sex-dependent effects of stress on aIC-NAc circuit neuroplasticity: Role of the endocannabinoid system. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2025; 138:111335. [CrossRef]

- Sazhina, T, Tsurugizawa T, Mochizuki Y, Saito A, Joji-Nishino A, Ouchi K, Yagishita S, Emoto K, Uematsu A. Time- and sex-dependent effects of juvenile social isolation on mouse brain morphology. Neuroimage. 2025 Mar 4;310:121117. [CrossRef]

- Wei, A.; Zhao, A.; Zheng, C.; Dong, N.; Cheng, X.; Duan, X.; Zhong, S.; Liu, X.; Jian, J.; Qin, Y. et al. Sexually dimorphic dopaminergic circuits determine sex preference. Science. 2025; 387(6730):eadq7001. [CrossRef]

- Sangu, N.; Shimojima, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Ohashi, T.; Tohyama, J.; Yamamoto, T. A 7q31.33q32.1 microdeletion including LRRC4 and GRM8 is associated with severe intellectual disability and characteristics of autism. Hum Genome Var. 2017; 4:17001. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.; Kannan, K.; Faustin, A.; Shroff, S.; Thomas, C.; Heguy, A.; Serrano, J.; Snuderl, M.; Devinsky, O. Cardiac arrhythmia and neuroexcitability gene variants in resected brain tissue from patients with sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). NPJ Genom Med. 2018; 3:9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tang, F.; Hu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Y.; Ma, Y. TMT-based proteomics profile reveals changes of the entorhinal cortex in a kainic acid model of epilepsy in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2023; 800:137127. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chen, X.; Pan, X.; Deng, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Liao, D.; Xu, J.; Chen, M. et al. Single-cell transcriptome analyses reveal critical roles of RNA splicing during leukemia progression. PLoS Biol. 2023; 21(5):e3002088. [CrossRef]

- Keustermans, G.C.; Kofink, D.; Eikendal, A.; de Jager, W.; Meerding, J.; Nuboer, R.; Waltenberger, J.; Kraaijeveld, A.O.; Jukema, J.W.; Sels, J.W. et al. Monocyte gene expression in childhood obesity is associated with obesity and complexity of atherosclerosis in adults. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1):16826. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Tuli, N.Y.; Iacobas, S.; Rasamny, J.K.; Moscatello, A.; Geliebter, J.; Tiwari, R.K. Gene master regulators of papillary and anaplastic thyroid cancers. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 2410–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwehn, P.M., Falter-Braun, P. Inferring protein from transcript abundances using convolutional neural networks. BioData Mining 2025 18. [CrossRef]

- Mekic, R.; Zolotovskaia, M.A.; Sorokin, M.; Mohammad, T.; Shaban, N.; Musatov, I.; Tkachev, V.; Modestov, A.; Simonov, A.; Kuzmin, D. et al. Number of human protein interactions correlates with structural, but not regulatory conservation of the respective genes. Front Genet. 2024; 15:1472638. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, J.; Cui, X. Research progress on estrogen and estrogen receptors in the occurrence and progression of autoimmune thyroid diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2025; 24(6):1038033. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Aten, S.; Ramirez-Plascencia, O.; Blake, C.; Holder, G.; Fishbein, E.; Vieth, A.; Zarghani-Shiraz, A.; Keister, E.; Howe, S.; Appo, A. et al. A time for sex: circadian regulation of mammalian sexual and reproductive function. Front Neurosci. 2025; 18:1516767. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Nebieridze, N.; Velíšek, L.; Velíšková, J. Estrogen Protects Neurotransmission Transcriptome During Status Epilepticus. Front Neurosci, 3: 12. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shi, C.; Tao, D.; Yang, C.; Luo, Y. Modulating reward and aversion: Insights into addiction from the paraventricular nucleus. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024, 30, e70046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ma, D.; Zhang, M.; Tang, M.; Ouyang, T.; Zhang, F.; Shi, X.; et al. Paraventricular hypothalamic RUVBL2 neurons suppress appetite by enhancing excitatory synaptic transmission in distinct neurocircuits. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, H.; Hanson, J.; Phelan, K.D.; Baldini, G. MC4R Localizes at Excitatory Postsynaptic and Peri-Postsynaptic Sites of Hypothalamic Neurons in Primary Culture. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Thomas, N.; Spray, D.C. Sex-dependent gene regulatory networks of the heart rhythm. Funct Integr Genomics 2010, 10, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Amuzescu, B.; Iacobas, D.A. Transcriptomic uniqueness and commonality of the ion channels and transporters in the four heart chambers. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Fan, C.; Iacobas, S.; Spray, D.C.; Haddad, G.G. Transcriptomic changes in developing kidney exposed to chronic hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 349, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).