Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

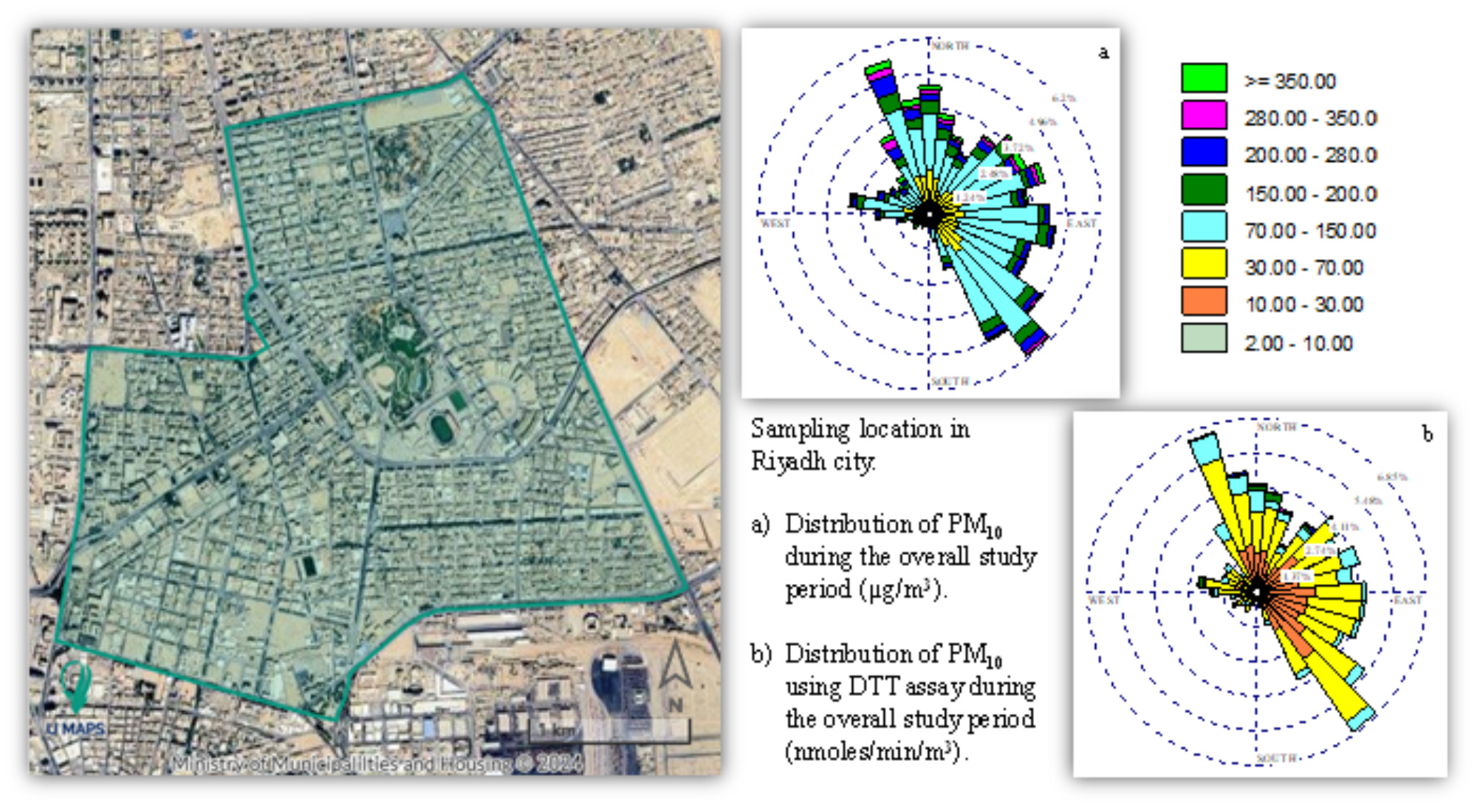

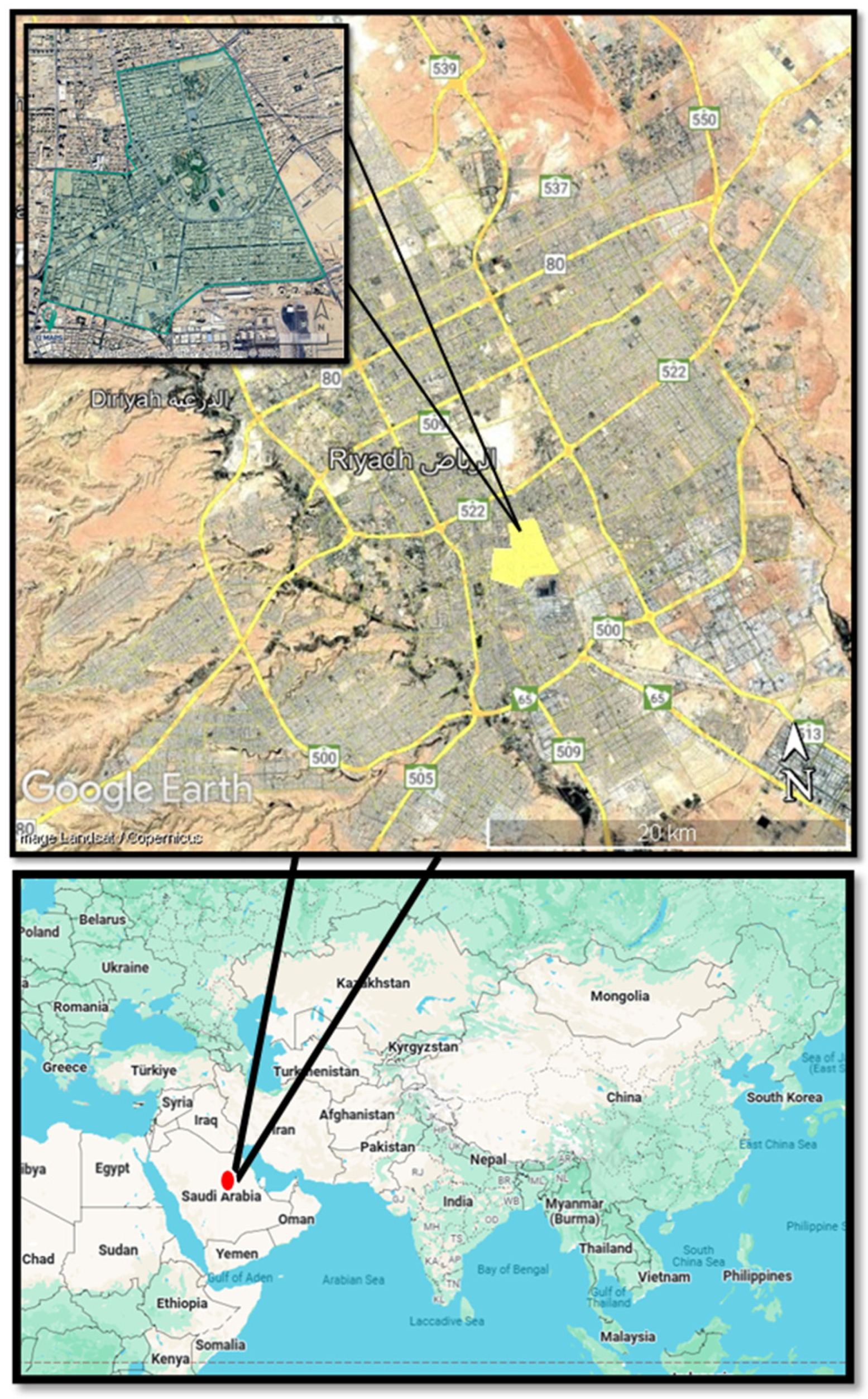

2.1. Sampling Location and Period

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Chemical and Toxicological Analysis

2.4. Wind and Pollutant Rose Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

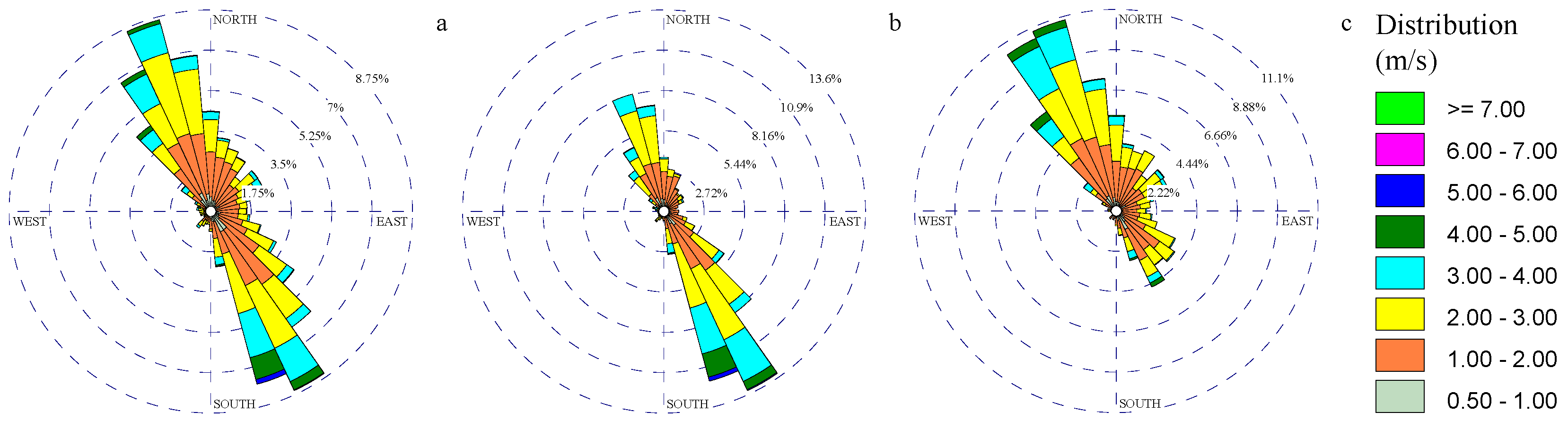

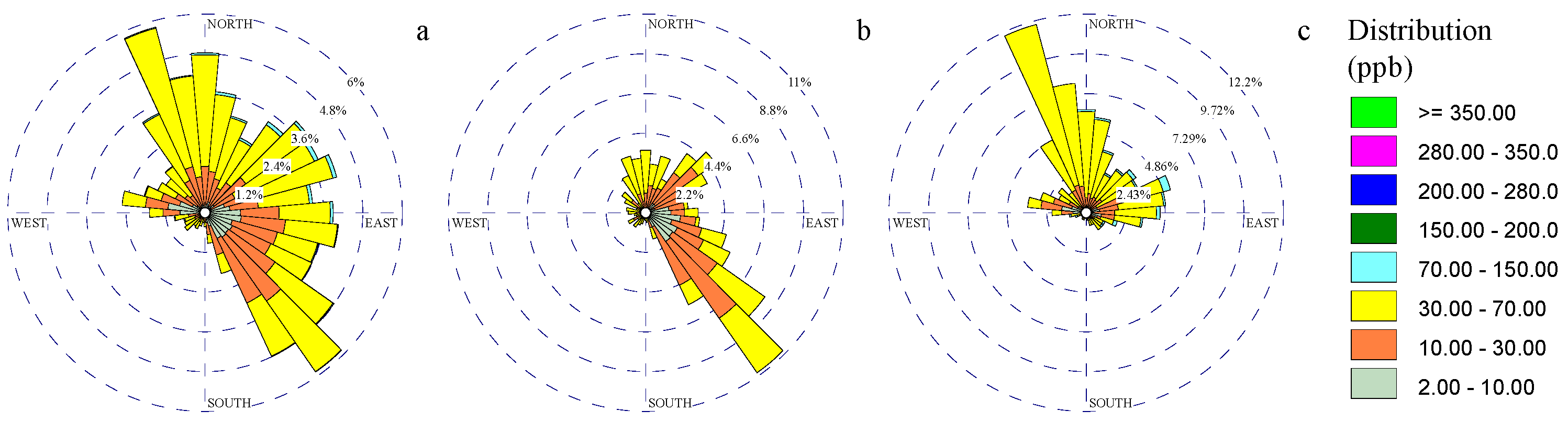

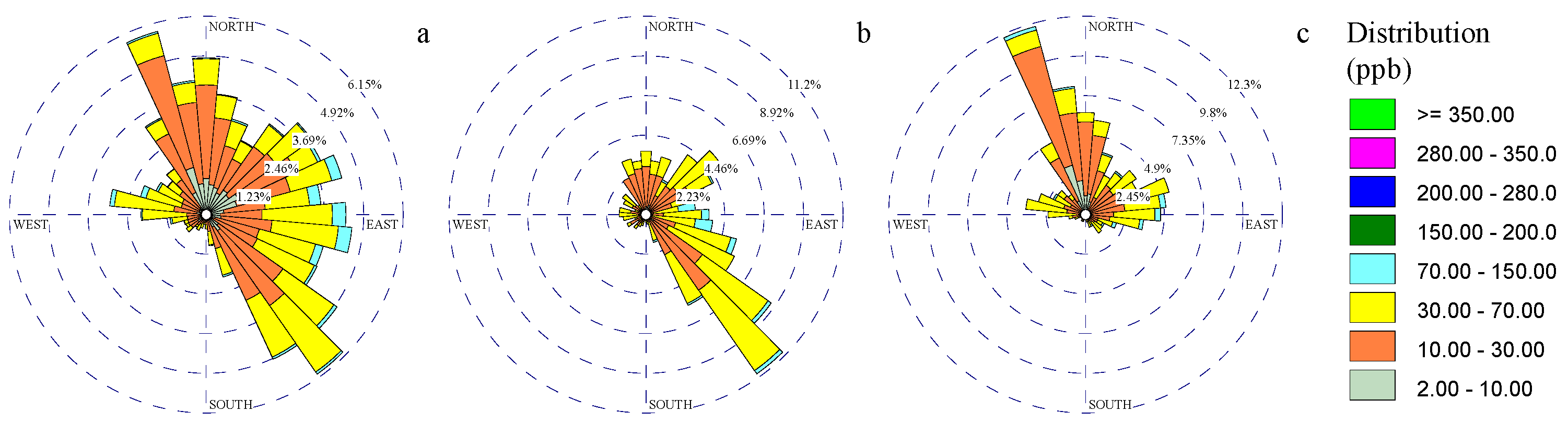

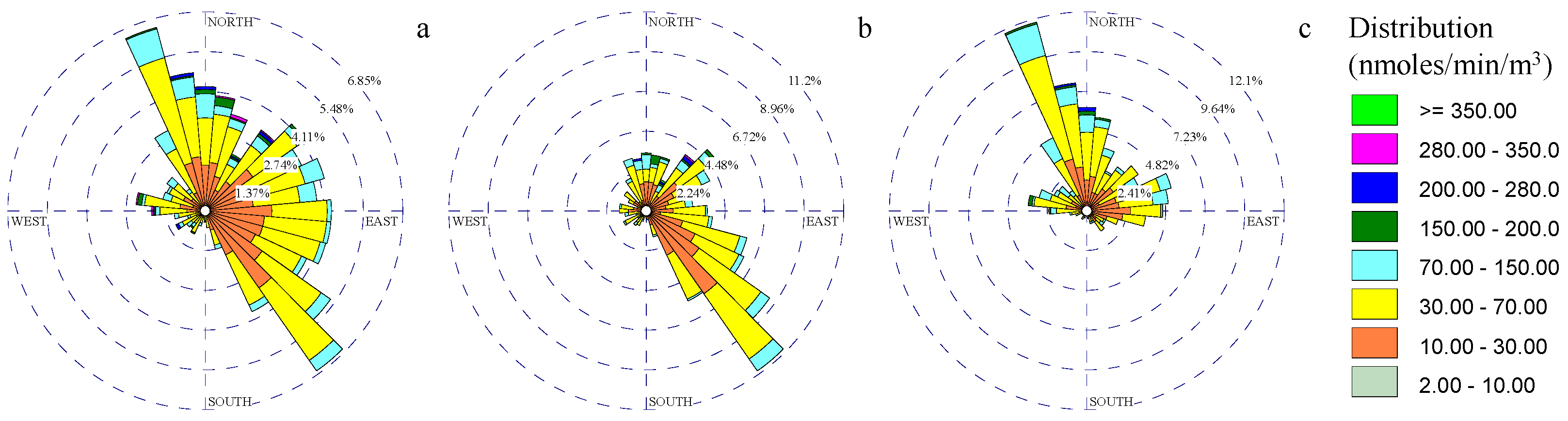

3.1. Wind and Gaseous Pollutant Rose Diagrams

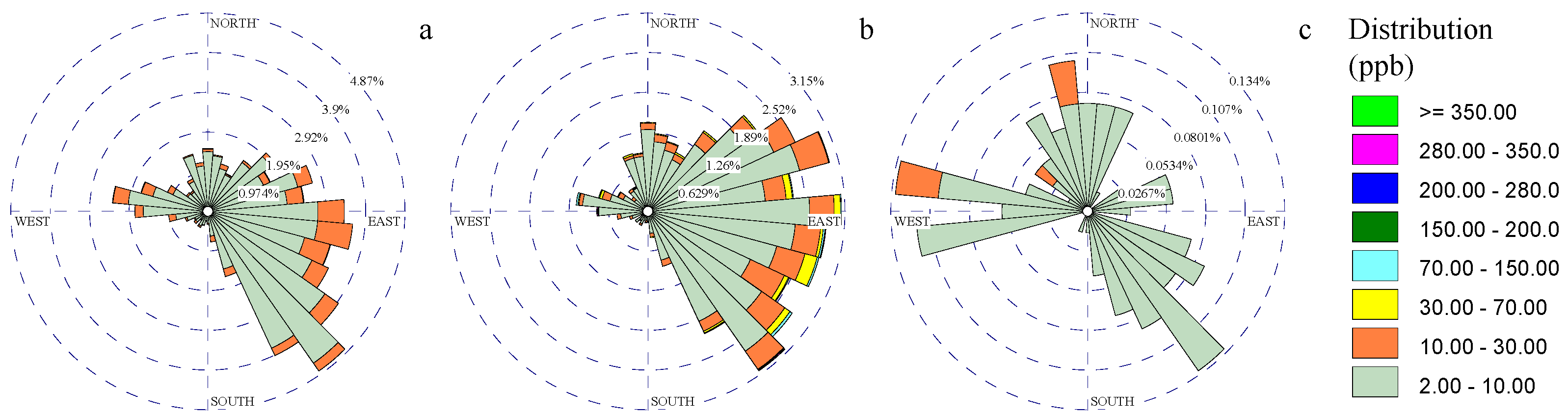

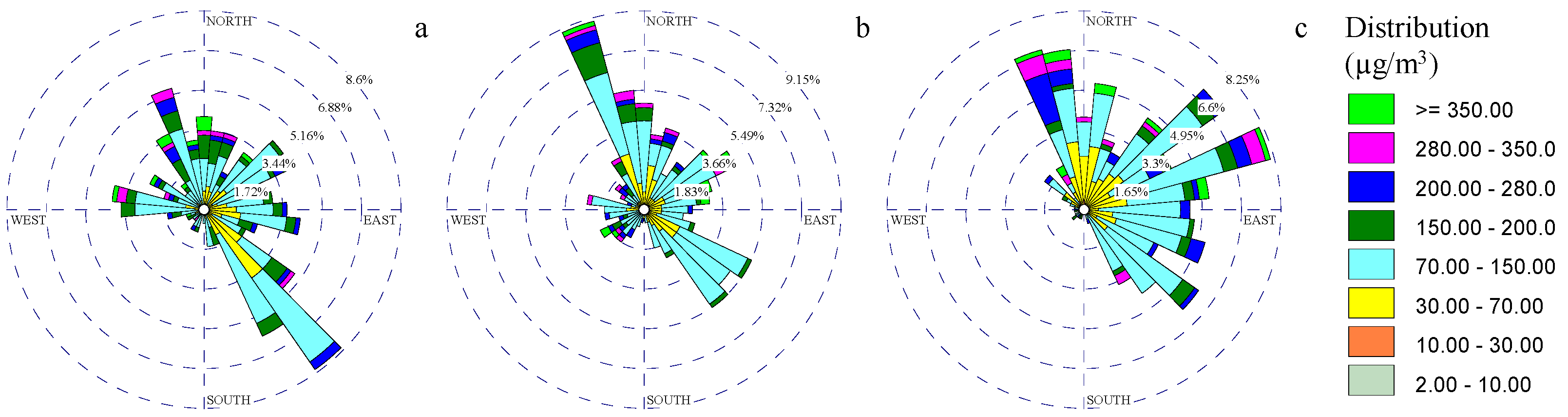

3.2. Metal Rose Diagrams

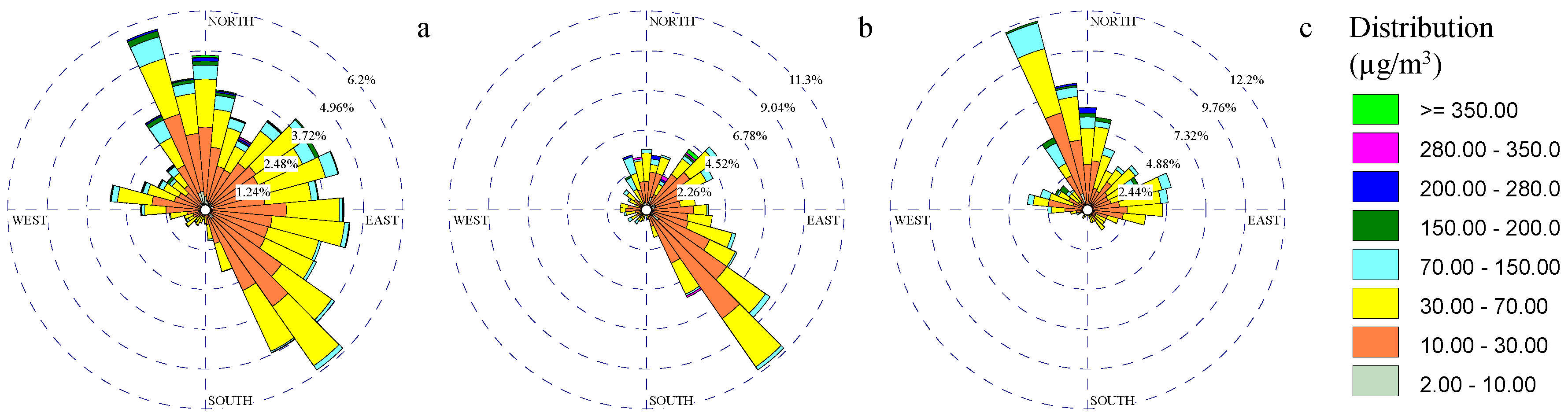

3.3. Particulate Matter Rose Diagrams

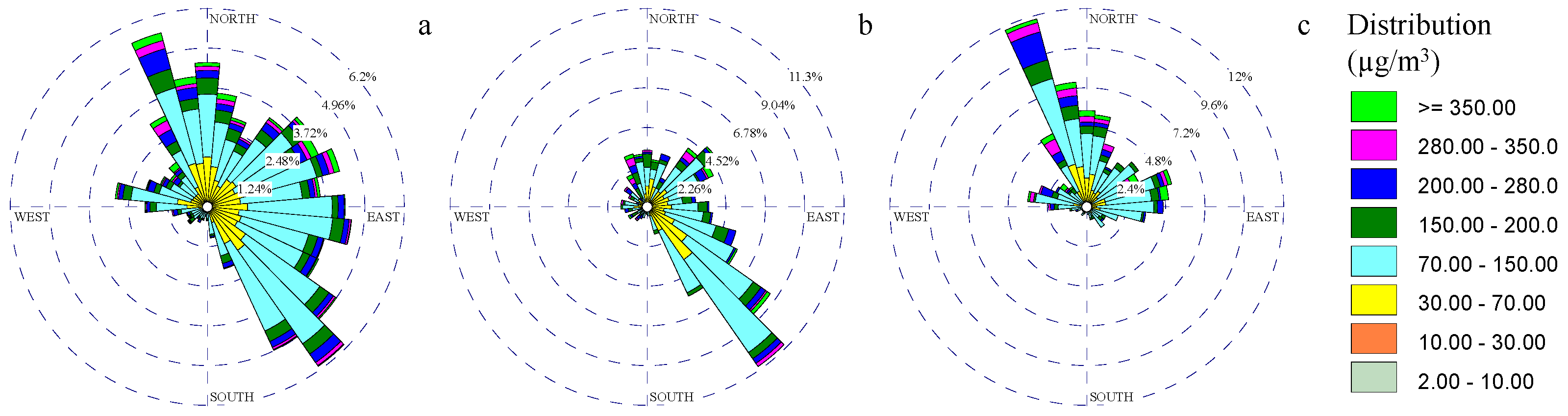

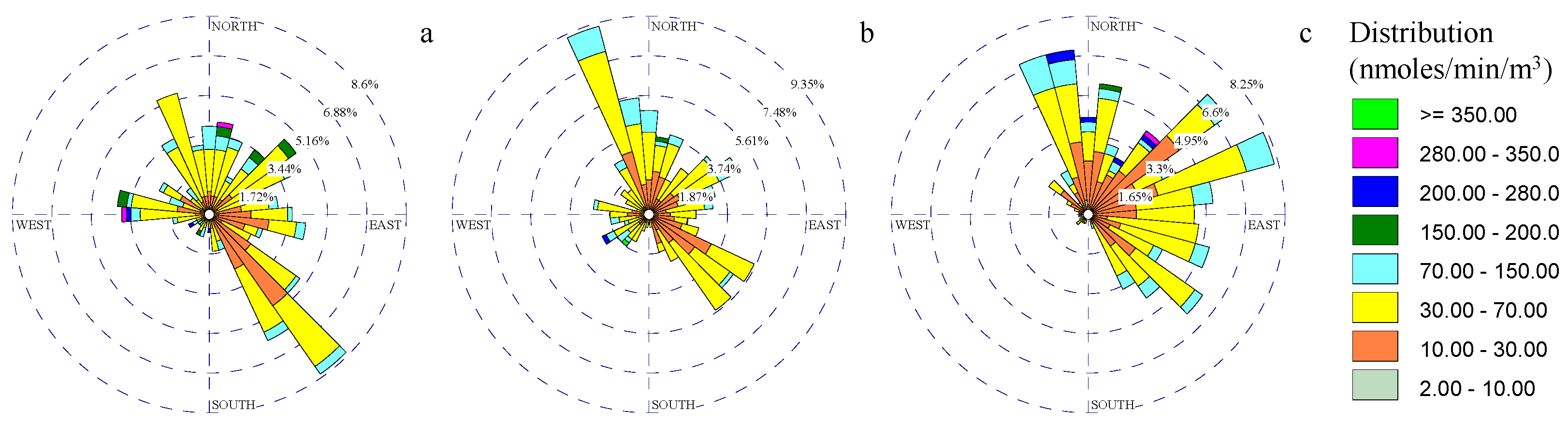

3.4. PM Toxicity Rose Diagrams

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manisalidis, I.; Stavropoulou, E.; Stavropoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and Health Impacts of Air Pollution: A Review. Front. Public Heal. 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, L.; Huang, S. Air Pollutants and Early Origins of Respiratory Diseases. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2018, 4, 75–94. [CrossRef]

- Badyda, A.; Gayer, A.; Czechowski, P.; Majewski, G.; Dąbrowiecki, P. Pulmonary Function and Incidence of Selected Respiratory Diseases Depending on the Exposure to Ambient PM10. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1954. [CrossRef]

- Dobaradaran, S., Geravandi, S., Goudarzi, G., Idani, E., Salmanzadeh, S., Soltani, F., Yari, A. R., & Mohammadi, M.J. Determination of Cardiovascular and Respiratory Diseases Caused by PM10 Exposure in Bushehr. 2016.

- Khaniabadi, Y.O.; Polosa, R.; Chuturkova, R.Z.; Daryanoosh, M.; Goudarzi, G.; Borgini, A.; Tittarelli, A.; Basiri, H.; Armin, H.; Nourmoradi, H.; et al. Human Health Risk Assessment Due to Ambient PM10 and SO2 by an Air Quality Modeling Technique. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 111, 346–354. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-M.; Vichit-Vadakan, N.; Kan, H.; Qian, Z. Public Health and Air Pollution in Asia (PAPA): A Multicity Study of Short-Term Effects of Air Pollution on Mortality. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1195–1202. [CrossRef]

- Mebrahtu, T.F.; Santorelli, G.; Yang, T.C.; Wright, J.; Tate, J.; McEachan, R.R. The Effects of Exposure to NO2, PM2.5 and PM10 on Health Service Attendances with Respiratory Illnesses: A Time-Series Analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 122123. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Seo, J.H.; Weon, S. Visualizing Indoor Ozone Exposures via O-Dianisidine Based Colorimetric Passive Sampler. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132510. [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A.; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A. V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R. V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease: An Update to the Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.T.; Fang, T.; Verma, V.; Zeng, L.; Weber, R.J.; Tolbert, P.E.; Abrams, J.Y.; Sarnat, S.E.; Klein, M.; Mulholland, J.A.; et al. Review of Acellular Assays of Ambient Particulate Matter Oxidative Potential: Methods and Relationships with Composition, Sources, and Health Effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4003–4019. [CrossRef]

- Lionetto, M.; Guascito, M.; Giordano, M.; Caricato, R.; De Bartolomeo, A.; Romano, M.; Conte, M.; Dinoi, A.; Contini, D. Oxidative Potential, Cytotoxicity, and Intracellular Oxidative Stress Generating Capacity of PM10: A Case Study in South of Italy. Atmosphere (Basel). 2021, 12, 464. [CrossRef]

- Ratto, G.; Maronna, R.; Berri, G. Analysis of Wind Roses Using Hierarchical Cluster and Multidimensional Scaling Analysis at La Plata, Argentina. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 2010, 137, 477–492. [CrossRef]

- AZIZI, M.; Hashim, N.H. Wind Rose Analysis for UTHM and Possible Pollution Sources Zone. Prog. Eng. Appl. Technol. 2021, 2, 432–443.

- Linda, J.; Hasečić, A.; Pospíšil, J.; Kudela, L.; Brzezina, J. Impact of Wind-Induced Resuspension on Urban Air Quality: A CFD Study with Air Quality Data Comparison. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 74. [CrossRef]

- Al–Dabbous, A.N.; Goel, A.; Alsulaili, A.; Al-Dabbous, S.K.; Shalash, M. Evaluating Particulate Matter Mass and Count Concentrations in a Vehicle Cabin: Insights from Kuwait City. J. Eng. Res. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dabbous, A.N.; Khan, A.R.; Al-Rashidi, M.S.; Awadi, L. Carbon Dioxide and Volatile Organic Compounds Levels in Mosque in Hot Arid Climate. Indoor Built Environ. 2013, 22, 456–464. [CrossRef]

- Al Nadhairi, R.; Al Kalbani, M.; Al Khazami, S.; Al Hashmi, M.; Al Zadai, S.; Al-Rumhi, Y.; Al-Kindi, K.M. Air Quality and Health Risk Assessment during Middle Eastern Dust Storms: A Study of Particulate Matter. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. 2025, 18, 587–603. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Hong, S.; Mu, H.; Tu, P.; Yang, L.; Ke, B.; Huang, J. Characteristics and Meteorological Factors of Severe Haze Pollution in China. Adv. Meteorol. 2021, 2021, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Saudi General Authority for Statistics General Authority for Statistics Available online: https://portal.saudicensus.sa/portal/public/1/15/1367?type=DASHBOARD.

- IQAIR Riyadh Air Quality Index (AQI) Available online: https://www.iqair.com/saudi-arabia/ar-riyad/riyadh.

- Alghamdi, A.G.; EL-Saeid, M.H.; Alzahrani, A.J.; Ibrahim, H.M. Heavy Metal Pollution and Associated Health Risk Assessment of Urban Dust in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0261957. [CrossRef]

- El-Mubarak, A.H.; Rushdi, A.I.; Al-Mutlaq, K.F.; Bazeyad, A.Y.; Simonich, S.L.M.; Simoneit, B.R.T. Occurrence of High Levels of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in Particulate Matter of the Ambient Air of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2015, 40, 81–92. [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Al-Tayib, M.; Hag-Elsafi, S.; Al-Duwarij, N. Assessment of Pollution Sources in the Southeastern of the Riyadh and Its Impact on the Population/Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2016, 9, 328. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, B.; Shareef, M.M.; Husain, T. Study of Chemical Characteristics of Particulate Matter Concentrations in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2015, 6, 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, B.; Pasha, M.; N, T. Assessment of Ambient Air Quality in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Curr. World Environ. 2014, 9, 227–236. [CrossRef]

- Bian, Q.; Alharbi, B.; Collett, J.; Kreidenweis, S.; Pasha, M.J. Measurements and Source Apportionment of Particle-Associated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Ambient Air in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 137, 186–198. [CrossRef]

- Altuwayjiri, A.; Pirhadi, M.; Kalafy, M.; Alharbi, B.; Sioutas, C. Impact of Different Sources on the Oxidative Potential of Ambient Particulate Matter PM10 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Focus on Dust Emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150590. [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Perrone, M.R.; Becagli, S.; Pietrogrande, M.C.; Russo, M.; Caricato, R.; Lionetto, M.G. Ecotoxicity, Genotoxicity, and Oxidative Potential Tests of Atmospheric PM10 Particles. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 221, 117085. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Polidori, A.; Arhami, M.; Shafer, M.M.; Schauer, J.J.; Cho, A.; Sioutas, C. Redox Activity and Chemical Speciation of Size Fractioned PM in the Communities of the Los Angeles-Long Beach Harbor. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2008, 8, 6439–6451. [CrossRef]

- Shafer, M.M.; Hemming, J.D.C.; Antkiewicz, D.S.; Schauer, J.J. Oxidative Potential of Size-Fractionated Atmospheric Aerosol in Urban and Rural Sites across Europe. Faraday Discuss. 2016, 189, 381–405. [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Verma, V.; Bates, J.T.; Abrams, J.; Klein, M.; Strickland, M.J.; Sarnat, S.E.; Chang, H.H.; Mulholland, J.A.; Tolbert, P.E.; et al. Oxidative Potential of Ambient Water-Soluble PM 2.5 in the Southeastern United States: Contrasts in Sources and Health Associations between Ascorbic Acid (AA) and Dithiothreitol (DTT) Assays. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 3865–3879. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Ahmed, C.M.S.; Canchola, A.; Chen, J.Y.; Lin, Y.-H. Use of Dithiothreitol Assay to Evaluate the Oxidative Potential of Atmospheric Aerosols. Atmosphere (Basel). 2019, 10, 571. [CrossRef]

- Aldekheel, M.; Tohidi, R.; Al-Hemoud, A.; Alkudari, F.; Verma, V.; Subramanian, P.S.G.; Sioutas, C. Identifying Urban Emission Sources and Their Contribution to the Oxidative Potential of Fine Particulate Matter (Pm2.5) in Kuwait 2023.

- Herner, J.D.; Green, P.G.; Kleeman, M.J. Measuring the Trace Elemental Composition of Size-Resolved Airborne Particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 1925–1933. [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, S.; Balasubramanian, R. Determination of Water-Soluble Inorganic and Organic Species in Atmospheric Fine Particulate Matter. Microchem. J. 2006, 82, 49–55. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, K.-J.; Chan, C.-C.; Su, T.-C.; Lee, C.-T.; Tang, C.-S. The Effect of Urban Air Pollution on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Coagulation, and Autonomic Dysfunction in Young Adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 176, 370–376. [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, B.; Reiners, J.J.; Xu, X.; Lemke, L.D. Identification and Influence of Spatio-Temporal Outliers in Urban Air Quality Measurements. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 573, 55–65. [CrossRef]

- Samani, A.A.N.; Dadfar, S.; Shahbazi, A. A Study on Dust Storms Using Wind Rose, Storm Rose and Sand Rose (Case Study: Tehran Province). Desert 2013, 18, 9–18.

- Alharbi, B.H.; Alduwais, A.K.; Alhudhodi, A.H. An Analysis of the Spatial Distribution of O 3 and Its Precursors during Summer in the Urban Atmosphere of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2017, 8, 861–872. [CrossRef]

- Meteostat Meteostat Riyadh Available online: https://meteostat.net/en/place/sa/riyadh?s=40438&t=2019-12-01/2020-09-25.

- Altuwayjiri, A.; Pirhadi, M.; Taghvaee, S.; Sioutas, C. Long-Term Trends in the Contribution of PM 2.5 Sources to Organic Carbon (OC) in the Los Angeles Basin and the Effect of PM Emission Regulations. Faraday Discuss. 2020, 0–37. [CrossRef]

- Ogen, Y. Assessing Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) Levels as a Contributing Factor to Coronavirus (COVID-19) Fatality. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 138605. [CrossRef]

- Bian, Q.; Alharbi, B.; Shareef, M.M.; Husain, T.; Pasha, M.J.; Atwood, S.A.; Kreidenweis, S.M. Sources of PM 2.5 Carbonaceous Aerosol in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 3969–3985. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, B.; Shareef, M.M.; Husain, T. Study of Chemical Characteristics of Particulate Matter Concentrations in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2015, 6, 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.L.; Hess, P.G.; Jain, S.L.; Arya, B.C.; Sharma, C. Surface Ozone in the Indian Region. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 6572–6584. [CrossRef]

- Amouei Torkmahalleh, M.; Hopke, P.K.; Broomandi, P.; Naseri, M.; Abdrakhmanov, T.; Ishanov, A.; Kim, J.; Shah, D.; Kumar, P. Exposure to Particulate Matter and Gaseous Pollutants during Cab Commuting in Nur-Sultan City of Kazakhstan. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 880–885. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, R.; Sera, F.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Guo, Y.; Tong, S.; Lavigne, E.; Correa, P.M.; Ortega, N.V.; Achilleos, S.; et al. Interactive Effects of Ambient Fine Particulate Matter and Ozone on Daily Mortality in 372 Cities: Two Stage Time Series Analysis. BMJ 2023, e075203. [CrossRef]

- Shareef, M.M.; Husain, T.; Alharbi, B. Analysis of Relationship between O3, NO, and NO2 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Asian J. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 12, 17–29. [CrossRef]

- Offenberg, J.H.; Lewis, C.W.; Lewandowski, M.; Jaoui, M.; Kleindienst, T.E.; Edney, E.O. Contributions of Toluene and α-Pinene to SOA Formed in an Irradiated Toluene/α-Pinene/NOx/ Air Mixture: Comparison of Results Using 14C Content and SOA Organic Tracer Methods. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 3972–3976. [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, L.; Donahue, N.M.; Pandis, S.N. High Formation of Secondary Organic Aerosol from the Photo-Oxidation of Toluene. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 2973–2986. [CrossRef]

- Kourtidis, K.A.; Ziomas, I.; Zerefos, C.; Kosmidis, E.; Symeonidis, P.; Christophilopoulos, E.; Karathanassis, S.; Mploutsos, A. Benzene, Toluene, Ozone, NO2 and SO2 Measurements in an Urban Street Canyon in Thessaloniki, Greece. Atmos. Environ. 2002, 36, 5355–5364. [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.; von Ehrenstein, O.; Weiland, S.; Wagner, C.; Wellie, O.; Nicolai, T.; von Mutius, E. Modeling Annual Benzene, Toluene, NO2, and Soot Concentrations on the Basis of Road Traffic Characteristics. Environ. Res. 2002, 90, 111–118. [CrossRef]

- Schnitzhofer, R.; Beauchamp, J.; Dunkl, J.; Wisthaler, A.; Weber, A.; Hansel, A. Long-Term Measurements of CO, NO, NO2, Benzene, Toluene and PM10 at a Motorway Location in an Austrian Valley. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 1012–1024. [CrossRef]

- Zuraski, K.; Harkins, C.; Peischl, J.; Coggon, M.M.; Stockwell, C.E.; Robinson, M.A.; Gilman, J.; Warneke, C.; McDonald, B.C.; Brown, S.S. On-Road Measurements of Nitrogen Oxides, CO, CO 2 , and VOC Emissions in Two Southwestern U.S. Cities. ACS ES&T Air 2025, 2, 589–598. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zboon, K. Effect of Cement Industry on Ambient Air Quality and Potential Health Risk: A Case Study from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. JORDANIAN J. Eng. Chem. Ind. 2021, 4, 14–23. [CrossRef]

- Stanislaus, A.; Marafi, A.; Rana, M.S. Recent Advances in the Science and Technology of Ultra Low Sulfur Diesel (ULSD) Production. Catal. Today 2010, 153, 1–68. [CrossRef]

- Wallington, T.J.; Anderson, J.E.; Dolan, R.H.; Winkler, S.L. Vehicle Emissions and Urban Air Quality: 60 Years of Progress. Atmosphere (Basel). 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Miyama, E.; Managi, S. Global Environmental Emissions Estimate: Application of Multiple Imputation. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2014, 16, 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dombek, T.; Hand, J.; Zhang, Z.; Gold, A.; Ault, A.P.; Levine, K.E.; Surratt, J.D. Seasonal Contribution of Isoprene-Derived Organosulfates to Total Water-Soluble Fine Particulate Organic Sulfur in the United States. ACS Earth Sp. Chem. 2021, 5, 2419–2432. [CrossRef]

- Gamnitzer, U.; Karstens, U.; Kromer, B.; Neubert, R.E.M.; Meijer, H.A.J.; Schroeder, H.; Levin, I. Carbon Monoxide: A Quantitative Tracer for Fossil Fuel CO2? J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2006, 111, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Okoshi, R.; Rasheed, A.; Chen Reddy, G.; McCrowey, C.P.; Curtis, D.B. Size and Mass Distributions of Ground-Level Sub-Micrometer Biomass Burning Aerosol from Small Wildfires. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 89, 392–402. [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Polidori, A.; Schauer, J.J.; Shafer, M.M.; Cassee, F.R.; Sioutas, C. Physicochemical and Toxicological Profiles of Particulate Matter in Los Angeles during the October 2007 Southern California Wildfires. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 954–960. [CrossRef]

- Altuwayjiri, A.; Pirhadi, M.; Taghvaee, S.; Sioutas, C. Long-Term Trends in the Contribution of PM 2.5 Sources to Organic Carbon (OC) in the Los Angeles Basin and the Effect of PM Emission Regulations. Faraday Discuss. 2021, 226, 74–99. [CrossRef]

- Fussell, J.C.; Franklin, M.; Green, D.C.; Gustafsson, M.; Harrison, R.M.; Hicks, W.; Kelly, F.J.; Kishta, F.; Miller, M.R.; Mudway, I.S.; et al. A Review of Road Traffic-Derived Non-Exhaust Particles: Emissions, Physicochemical Characteristics, Health Risks, and Mitigation Measures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6813–6835. [CrossRef]

- Grigoratos, T.; Martini, G. Brake Wear Particle Emissions: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 2491–2504. [CrossRef]

- Hulskotte, J.H.J.; Denier van der Gon, H.A.C.; Visschedijk, A.J.H.; Schaap, M. Brake Wear from Vehicles as an Important Source of Diffuse Copper Pollution. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 56, 223–231. [CrossRef]

- Flament, P.; Mattielli, N.; Aimoz, L.; Choël, M.; Deboudt, K.; Jong, J. de; Rimetz-Planchon, J.; Weis, D. Iron Isotopic Fractionation in Industrial Emissions and Urban Aerosols. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 1793–1798. [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, J.G.; Kraemer, S.M.; Teutsch, N.; Borer, P.M.; Halliday, A.N.; Kretzschmar, R. Iron Isotope Fractionation during Proton-Promoted, Ligand-Controlled, and Reductive Dissolution of Goethite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 3787–3793. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Amelung, W.; Xing, Y.; Bol, R.; Berns, A.E. Iron Cycling and Isotope Fractionation in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Earth-Science Rev. 2019, 190, 323–352. [CrossRef]

- Choël, M.; Deboudt, K.; Osán, J.; Flament, P.; Van Grieken, R. Quantitative Determination of Low- Z Elements in Single Atmospheric Particles on Boron Substrates by Automated Scanning Electron Microscopy−Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 5686–5692. [CrossRef]

- Kandler, K.; Benker, N.; Bundke, U.; Cuevas, E.; Ebert, M.; Knippertz, P.; Rodríguez, S.; Schütz, L.; Weinbruch, S. Chemical Composition and Complex Refractive Index of Saharan Mineral Dust at Izaña, Tenerife (Spain) Derived by Electron Microscopy. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 8058–8074. [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; He, K.; Cheng, Y.; Duan, F.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, M.; Weber, R. A Yearlong Study of Water-Soluble Organic Carbon in Beijing II: Light Absorption Properties. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 89, 235–241. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Mu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shao, L. A Comparison Study on Airborne Particles during Haze Days and Non-Haze Days in Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 456–457, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jing, J.; Tao, J.; Hsu, S.C.; Wang, G.; Cao, J.; Lee, C.S.L.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Chemical Characterization and Source Apportionment of PM2.5 in Beijing: Seasonal Perspective. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 7053–7074. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.-L.; Bi, X.-H.; Wu, J.-H.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Yao, L.; Jiao, L.; Feng, Y.-C. Characterization and Source Identification of Heavy Metals in Ambient PM10 and PM2.5 in an Integrated Iron and Steel Industry Zone Compared with a Background Site. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 875–887. [CrossRef]

- Matović, V.; Buha, A.; Bulat, Z.; Đukić-Ćosić, D. Cadmium Toxicity Revisited: Focus on Oxidative Stress Induction and Interactions with Zinc and Magnesium. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2011, 62, 65–76. [CrossRef]

- Pant, P.; Harrison, R.M. Estimation of the Contribution of Road Traffic Emissions to Particulate Matter Concentrations from Field Measurements : A Review. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 77, 78–97. [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Wang, C.; Wei, J.; Wang, D.; Jin, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Ren, A.; Yin, C. Essential Trace Elements in Placental Tissue and Risk for Fetal Neural Tube Defects. Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105688. [CrossRef]

- Alahabadi, A.; Ehrampoush, M.H.; Miri, M.; Ebrahimi Aval, H.; Yousefzadeh, S.; Ghaffari, H.R.; Ahmadi, E.; Talebi, P.; Abaszadeh Fathabadi, Z.; Babai, F.; et al. A Comparative Study on Capability of Different Tree Species in Accumulating Heavy Metals from Soil and Ambient Air. Chemosphere 2017, 172, 459–467. [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, M.; Tsang, Y.F.; Kim, K.-H. Heavy Metals in Food Crops: Health Risks, Fate, Mechanisms, and Management. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 365–385. [CrossRef]

- Ronco, A.M.; Arguello, G.; Suazo, M.; Llanos, M.N. Increased Levels of Metallothionein in Placenta of Smokers. Toxicology 2005, 208, 133–139. [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Cassee, F.R.; van der Gon, H.A.C.D.; Gehrig, R.; Gustafsson, M.; Hafner, W.; Harrison, R.M.; Jozwicka, M.; Kelly, F.J.; Moreno, T. Urban Air Quality: The Challenge of Traffic Non-Exhaust Emissions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 275, 31–36.

- Alharbi, B.; Shareef, M.M.; Husain, T. Study of Chemical Characteristics of Particulate Matter Concentrations in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2015, 6, 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A.; Ezzati, M.; Dockery, D.W. Fine-Particulate Air Pollution and Life Expectancy in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 376–386. [CrossRef]

- Manousakas, M.; Diapouli, E.; Belis, C.A.; Vasilatou, V.; Gini, M.; Lucarelli, F.; Querol, X.; Eleftheriadis, K. Quantitative Assessment of the Variability in Chemical Profiles from Source Apportionment Analysis of PM10 and PM2.5 at Different Sites within a Large Metropolitan Area. Environ. Res. 2021, 192, 110257. [CrossRef]

- Khodeir, M.; Shamy, M.; Alghamdi, M.; Zhong, M.; Sun, H.; Costa, M.; Chen, L.C.; Maciejczyk, P. Source Apportionment and Elemental Composition of PM2.5 and PM10 in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2012, 3, 331–340. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hemoud, A.; Al-Dousari, A.; Al-Shatti, A.; Al-Khayat, A.; Behbehani, W.; Malak, M. Health Impact Assessment Associated with Exposure to PM10 and Dust Storms in Kuwait. Atmosphere (Basel). 2018, 9, 6. [CrossRef]

- Mijić, Z.; Tasić, M.; Rajšić, S.; Novaković, V. The Statistical Characters of PM10 in Belgrade Area. Atmos. Res. 2009, 92, 420–426. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-López, M.A.; Rodríguez-González, M.A.; Soto-Villalobos, R.; Gómez-Sánchez, L.E.; Benavides-Ríos, Á.G.; Benavides-Bravo, F.G.; Walle-García, O.; Pamanés-Aguilar, M.G. Statistical Analysis of PM10 Concentration in the Monterrey Metropolitan Area, Mexico (2010–2018). Atmosphere (Basel). 2022, 13, 297. [CrossRef]

- Borlaza, L.J.; Weber, S.; Marsal, A.; Uzu, G.; Jacob, V.; Besombes, J.-L.; Chatain, M.; Conil, S.; Jaffrezo, J.-L. Nine-Year Trends of PM 10 Sources and Oxidative Potential in a Rural Background Site in France. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 8701–8723. [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Uzu, G.; Favez, O.; Borlaza, L.J.S.; Calas, A.; Salameh, D.; Chevrier, F.; Allard, J.; Besombes, J.-L.; Albinet, A.; et al. Source Apportionment of Atmospheric PM 10 Oxidative Potential: Synthesis of 15 Year-Round Urban Datasets in France. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 11353–11378. [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, H.; Janssen, N.A.H.; Fischer, P.H.; Kos, G.P.A.; Weijers, E.P.; Cassee, F.R.; van der Zee, S.C.; de Hartog, J.J.; Brunekreef, B.; Hoek, G. Contrasts in Oxidative Potential and Other Particulate Matter Characteristics Collected Near Major Streets and Background Locations. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 185–191. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Guo, H.; Cheng, T.; Li, X. Particle Size Distributions of Oxidative Potential of Lung-Deposited Particles: Assessing Contributions from Quinones and Water-Soluble Metals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 6592–6600. [CrossRef]

- Cipoli, Y.A.; Rienda, I.C.; de la Campa, A.M.S.; Kováts, N.; Nunes, T.; Feliciano, M.; Hoffer, A.; Jancsek-Turóczi, B.; Alves, C. Emission Factors, Chemical Composition and Ecotoxicity of PM10 from Road Dust Resuspension in a Small Inland City. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 748. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).