1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is one of the most lethal gynecologic malignancies worldwide, posing significant challenges due to late detection, high recurrence, and poor survival rates [

1]. Serous ovarian carcinomas (SOCs), the most prevalent form of epithelial OC, are classified by the WHO into serous cystadenomas, adenofibromas, borderline tumors, and low- and high-grade carcinomas [

2]. Although OC incidence in the U.S. has declined by ~2% annually from 2017 to 2021, African American (AA) women continue to experience significantly lower 5-year survival rates compared to Caucasian American (CA) women (CDC (

https://gis.cdc.gov); [

3]). Population-specific genetic and molecular differences partly drive these disparities [

4,

5].

miRNAs are small, non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression by degrading or inhibiting translation of target mRNAs, thereby influencing oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes [

6]. MicroRNA (miRNA) expression variations may partially explain ethnic differences in SOC, given their roles in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, invasion, and angiogenesis [

7]. miRNAs are thus promising candidates for diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers [

8,

9]. Circulating miRNAs are stable in biofluids and can be detected through advanced techniques like in situ hybridization and qRT-PCR, enhancing their clinical utility [

10].

Historically, High-grade SOC has been associated with mutations in TP53 and BRCA1/2, which are targets of standard therapies, including platinum-taxane combinations and PARP inhibitors [

11]. However, resistance and recurrence remain significant barriers. Conventional biomarkers such as CA125 and HE4 lack sensitivity and specificity, especially in early-stage disease, prompting interest in miRNA-based alternatives [

12].

Several miRNAs—such as miR-200, miR-141, let-7b, and miR-199a—have been identified as prognostic in OC [

13]. Genes like ITGB1, TIMP3, and BRAF, listed in the Human Protein Atlas (TCGA), also emerge as potential prognostic markers. ITGB1, often upregulated in OC, promotes tumor progression [

14,

15]. TIMP3 functions as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting MMPs, promoting apoptosis, and preventing angiogenesis [

16]. Downregulation of TIMP3—as influenced by miR-30d—is associated with poorer outcomes and increased invasiveness [

17]. BRAF mutations, especially V600E, are linked to favorable outcomes in low-grade serous tumors [

18]. miR-143, known to target BRAF, has been shown to suppress tumor proliferation and chemoresistance in lung cancer models [

19], suggesting similar potential in SOC.

Our current study focuses on the differential expression of miR-192, miR-30d, hsa-miR-16-5p, miR-143-3p, and miR-20a-5p and their relationship with the prognostic markers ITGB1, TIMP3, and BRAF, to better understand the molecular basis of racial disparities in SOC outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

Real-Time qPCR

The expression of the miRNA genes analyzed in this study was assessed with Real-Time qPCR, as optimized previously [

20], using cDNA prepared from 35 samples, consisting of 19 paraffin-embedded SOC samples and 16 fresh tissues of ovarian cancer archival de-identified patient samples. Using miR-192-5p, miR-30D, hsa-miR-16 -1-5p, miR-143-3p, miR-20a-5p primer sets and the U6 gene (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) as an internal reaction control (

Table 1), the PCR analyses were performed using the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Oslo, Norway). The reactions were carried out in quadruplicate using the SYBR green Master Mix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The Real-Time data were analyzed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The normalized expression was calculated using the ΔCt (Livak) method35 [

21].

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis of miRNA (miR-192-5p, miR-30D, hsa-miR-16 -1-5p, miR-143-3p, miR-20a-5p) gene differential expression and correlated survival analysis in Caucasian versus African American ovarian cancer samples in TCGA was performed using the UALCAN online database platform [

22]. Predicted prognostic markers associated with the selected miRNAs were identified using the Human Protein Atlas (

www.proteinatlas.org) embedded in the UALCAN database. The association between predicted prognostic markers and target miRNAs was performed using miRTargetLink 2.0 [

23] and Enrichr (www. maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr) [

24] Online platforms to establish interactive miRNA target gene and target pathway networks.

Changes in Cycle Threshold (ΔCt) values obtained from RTqPCR were analyzed for relative expression using Microsoft Excel. Further statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R (version 4.42). We performed linear regression analyses to assess the associations between the relative expression levels of miR-192-5p, miR-30D, hsa-miR-16 -1-5p, miR-143-3p, miR-20a-5p, and key independent variables, including Ethnicity, Stage at Diagnosis, Age at Diagnosis, Overall Survival (OS_ Months), and OS_ Status (

Supplementary Table S1). The normality of continuous quantitative variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and statistical significance was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05. A Wilcoxon test was used to assess survival differences between ethnic groups. The association between two categorical variables was assessed using Fisher’s exact test.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative and Quantitative Clinical and Pathological Characterization of the Patients in the LLU Cohort

All patients in the LLU cohort were diagnosed with high-grade serous ovarian cancer (

Supplementary Table S1). Of these, 8 patients were diagnosed with stage I, 4 with stage II, 19 with stage III, and 4 with stage IV. All patients underwent debulking surgery (optimal cytoreduction) followed by chemotherapy with carboplatin/paclitaxel. Analysis of overall survival between the African American and Caucasian groups did not show a statistical difference, as shown in the Kaplan-Meier curve in the

Supplementary Figure S3.

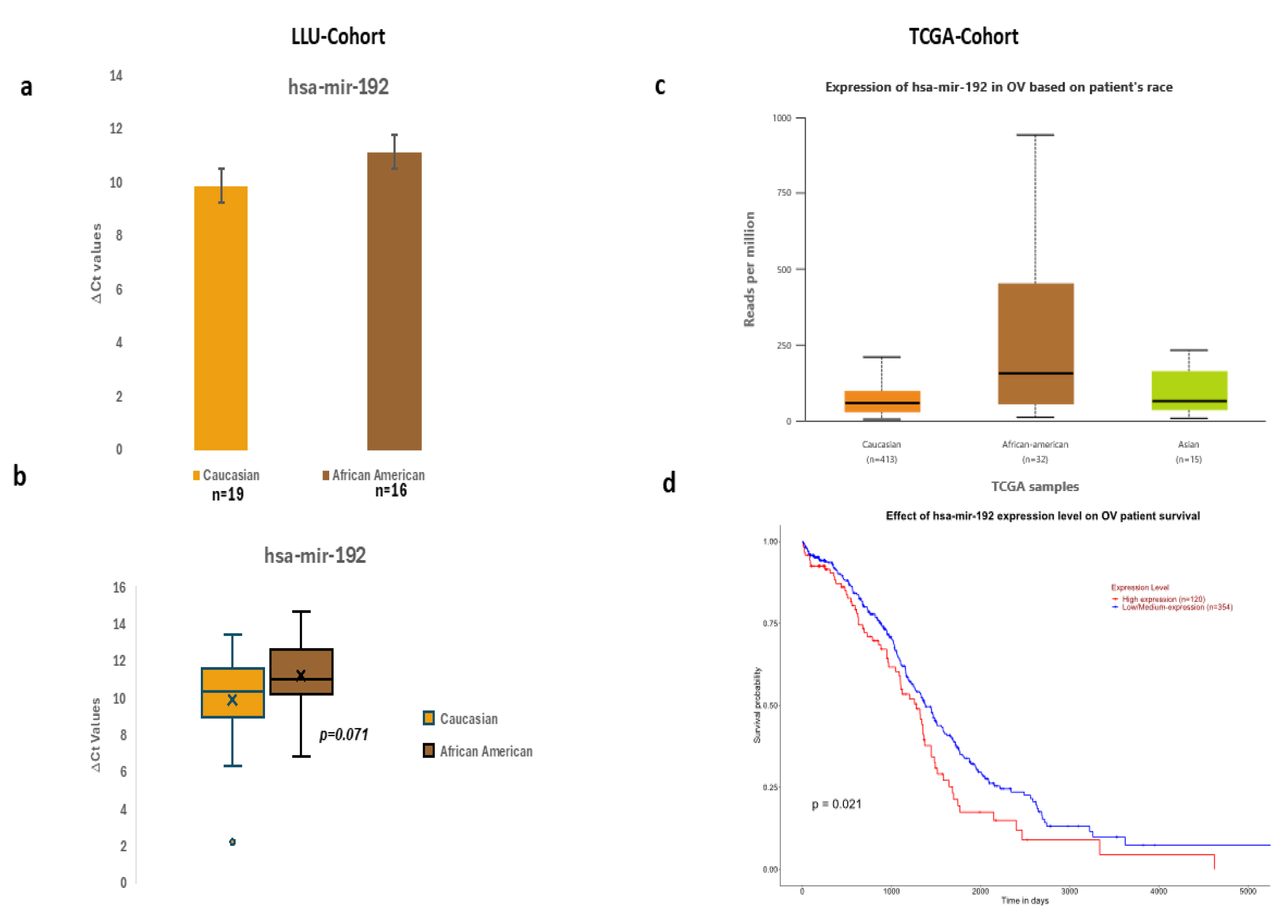

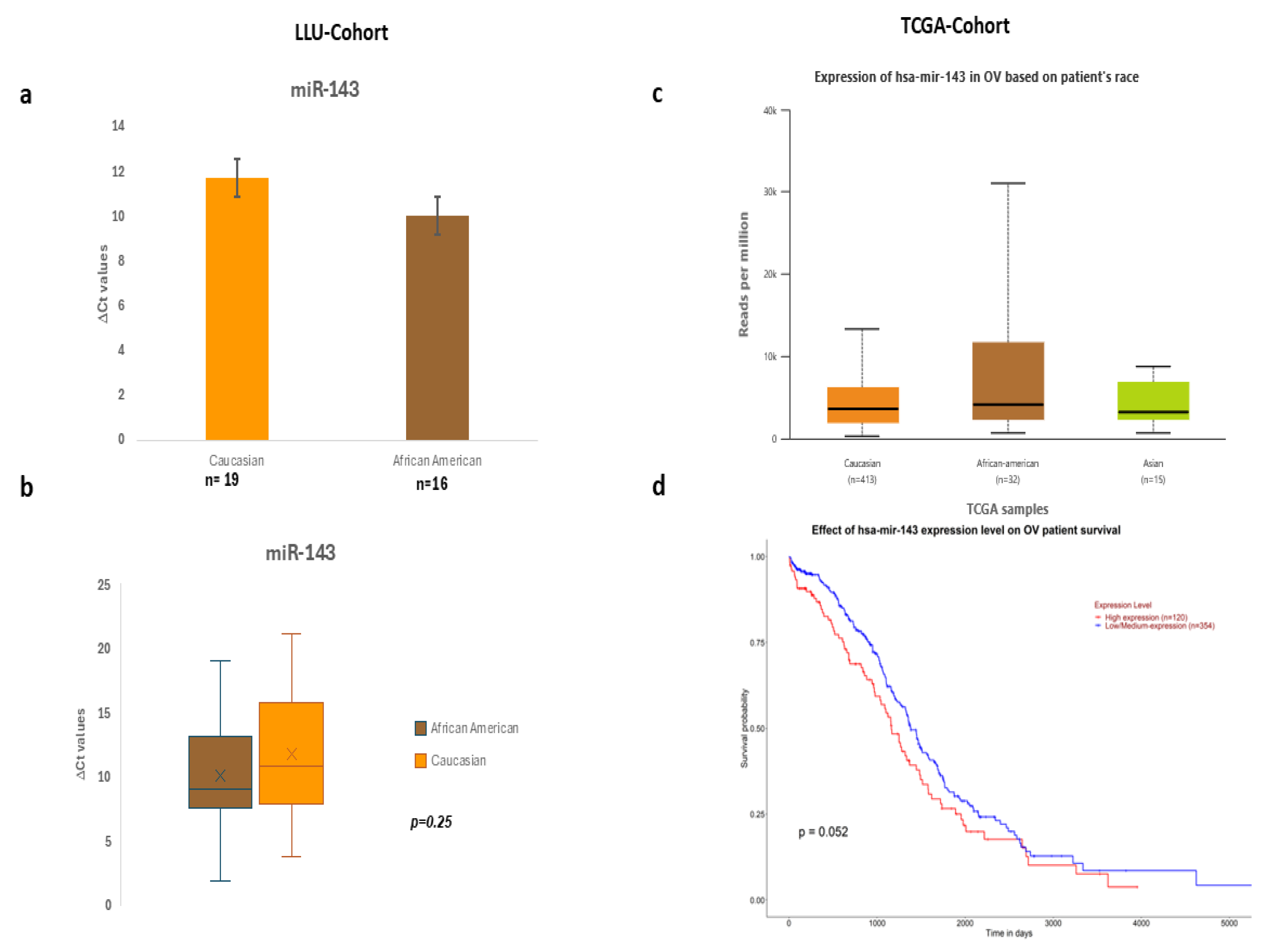

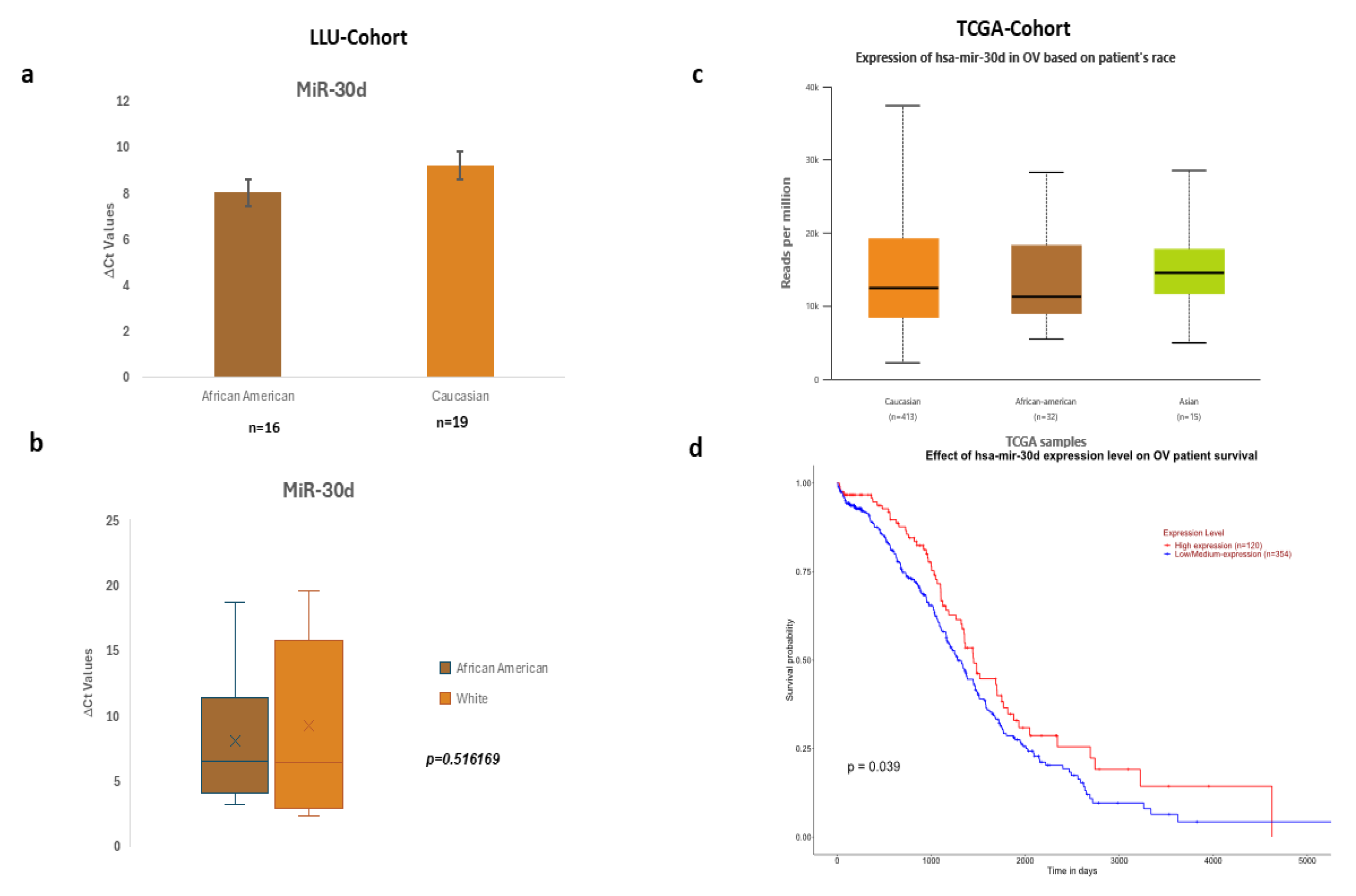

3.2. Differential Expression of miR-192, miR-30D, hsa-miR-16-5p, miR-143-3p, and miR-20a-5p in LLU vs. TCGA Ovarian Cancer Cohorts

To establish whether the targeted miR-192, miR-30D, hsa-miR-16 -1-5p, miR-143-3p, and miR-20a-5p were expressed differentially in the two ethnic groups constituting the LLU cohort, we performed real-time qPCR and assessed their fold expression compared to the control gene, U6. We validated our results by observing similar trends in the fold expression of miR-192-5p, miR-30D, hsa-miR-16 -1-5p, miR-143-3p, and miR-20a-5p in a large TCGA sample (n=444), as shown in

Figure 1 (a,b, c, d), 2 (a, b, c, d), 3 (a, b, c, d), and

Supplementary Figure S1 and Figure S2.

Figure 1.

a-b: Expression of miR192 in the LLU cohort based on differences in ΔCt values, c-d: TCGA cohort expression in OV based on patients' race and overall survival.

Figure 1.

a-b: Expression of miR192 in the LLU cohort based on differences in ΔCt values, c-d: TCGA cohort expression in OV based on patients' race and overall survival.

Figure 2.

a-b Expression of hsa- miR-143-3p in LLU cohort based on differences in ΔCt values, c-d: TCGA cohort expression in OV based on patients' race and overall survival.

Figure 2.

a-b Expression of hsa- miR-143-3p in LLU cohort based on differences in ΔCt values, c-d: TCGA cohort expression in OV based on patients' race and overall survival.

Figure 3.

a-b: Expression of miR-30d in LLU cohort based on differences in ΔCt values, c-d: TCGA cohort expression in OV based on patients' race and overall survival.

Figure 3.

a-b: Expression of miR-30d in LLU cohort based on differences in ΔCt values, c-d: TCGA cohort expression in OV based on patients' race and overall survival.

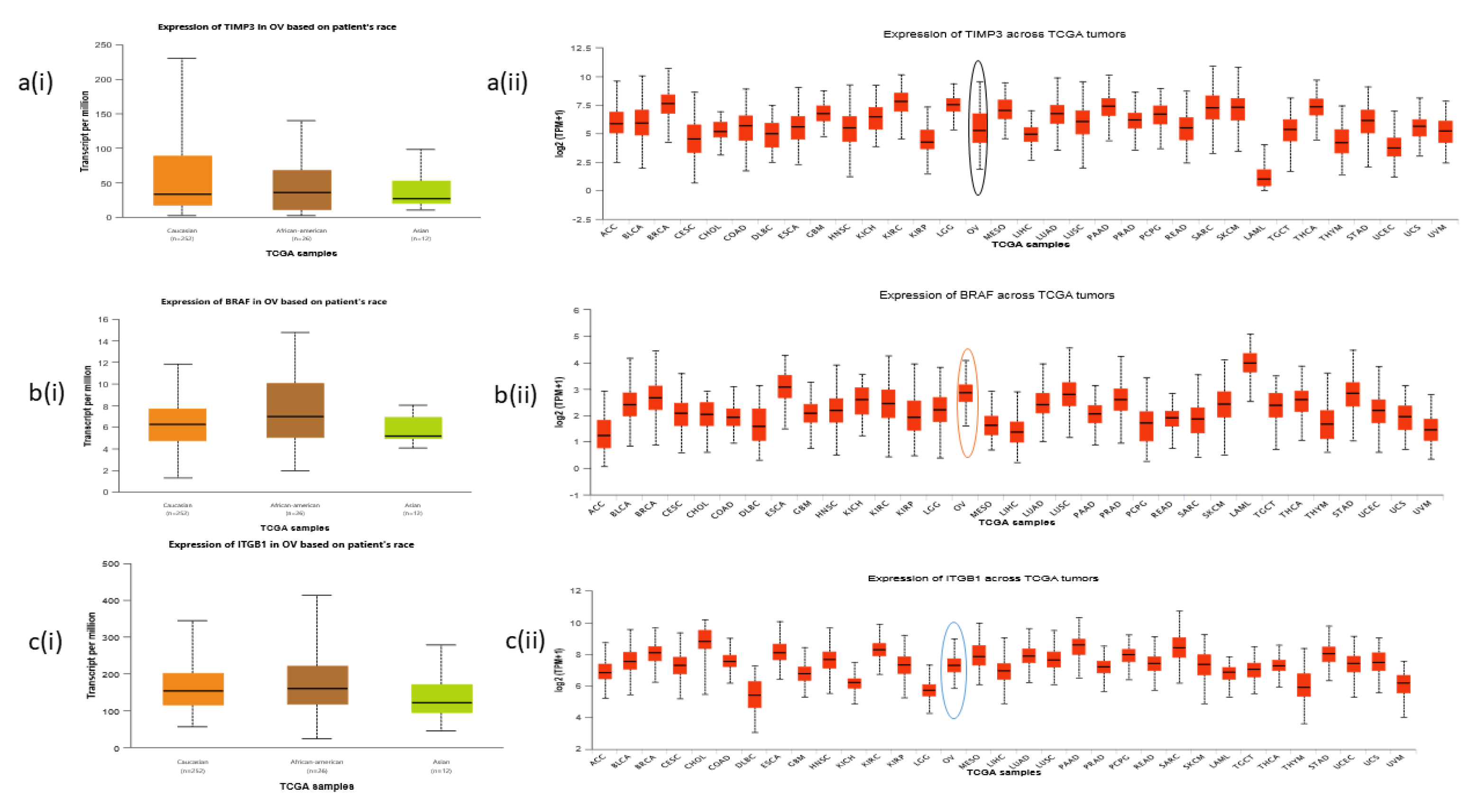

3.3. Differential Expression of Predicted Prognostic Markers in Ovarian Cancer Tissues from the TCGA Cohort

TCGA data showed evidence of differential expression of predicted prognostic markers TIMP3, BRAF, and ITGB1 based on patient’s race across ovarian cancer tumors, as shown in

Figure 4 (a-c).

Figure 4.

a-c: Expression patterns of predicted target markers TIMP3, BRAF, and ITGB1.

Figure 4.

a-c: Expression patterns of predicted target markers TIMP3, BRAF, and ITGB1.

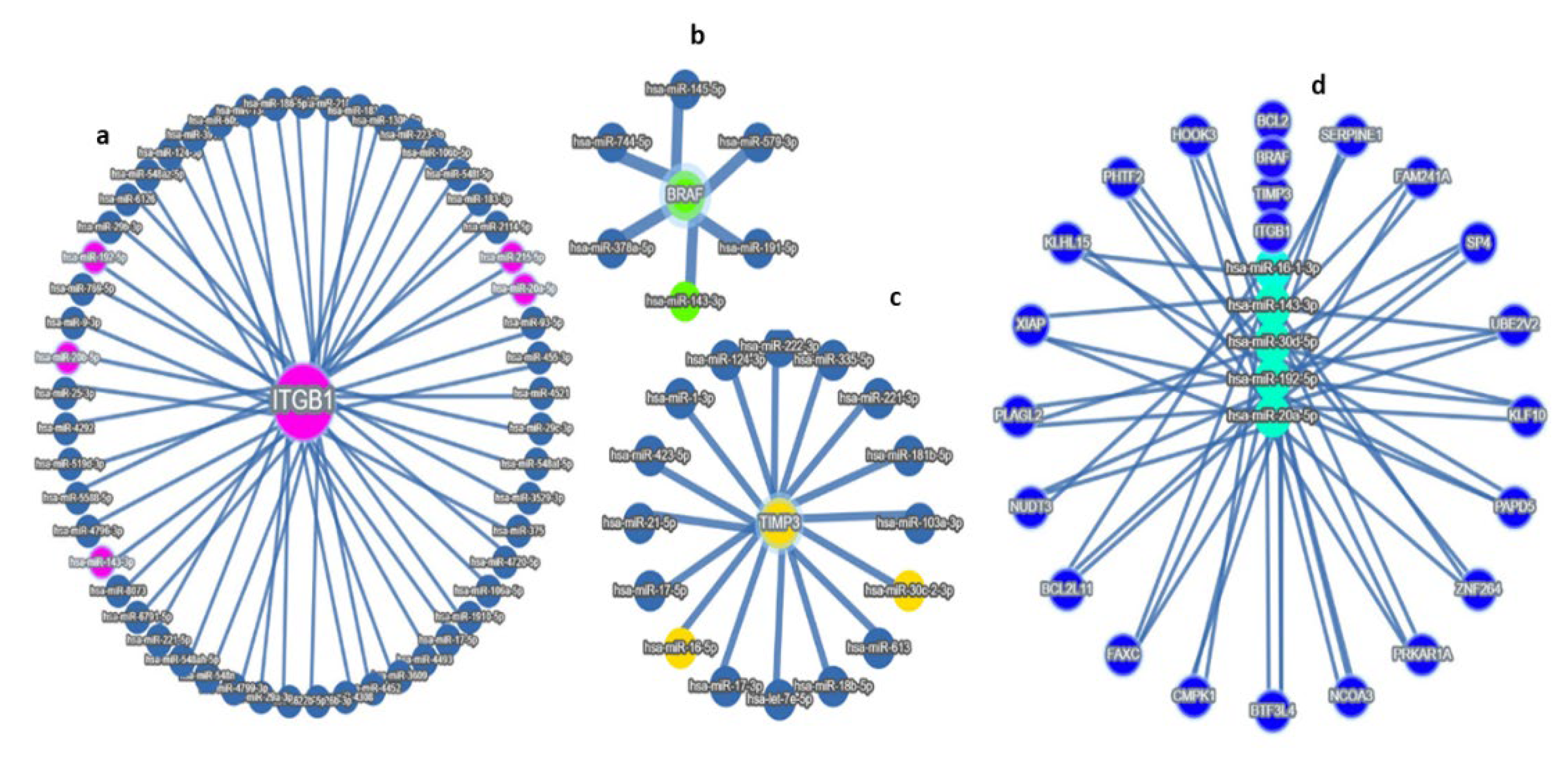

3.4. miRNAs Linked to Predicted Prognostic Genes:

We have found that miR192, miR-143-3p, and miR-20a were related to three critical prognostic genes: ITGB1, BRAF, and TIMP3, respectively (

Figure 5a-d).

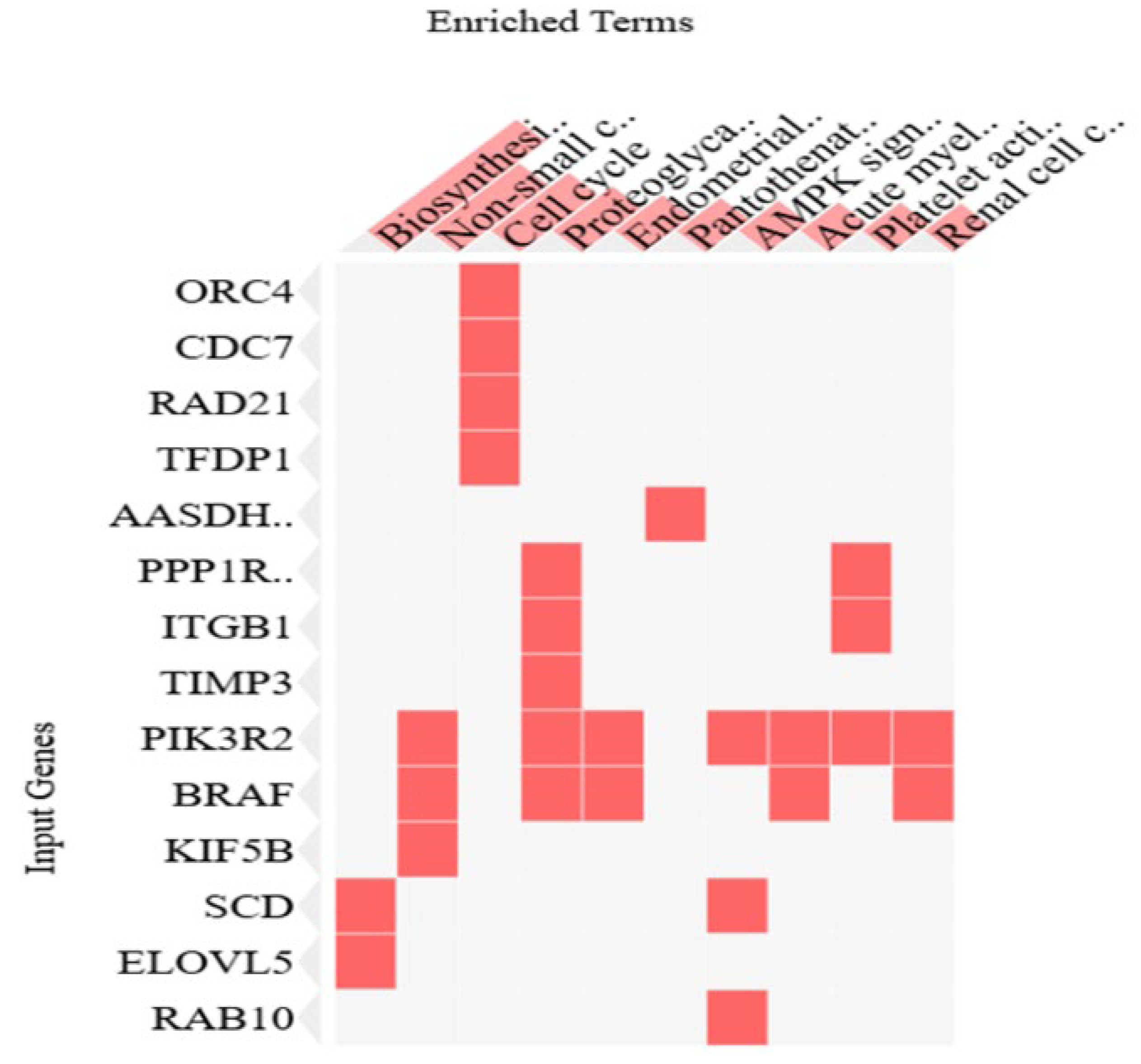

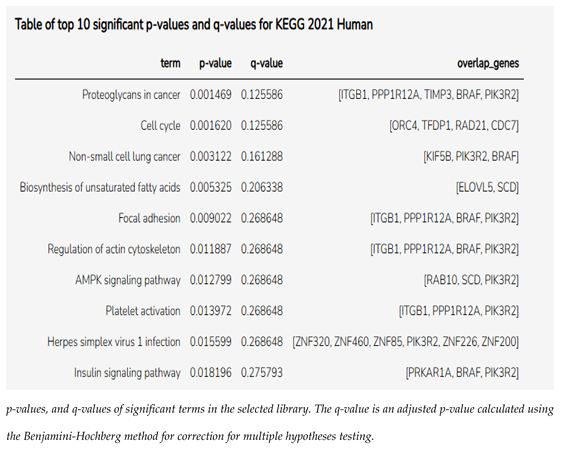

3.5. Enrichment Pathway Analysis of miRNAs Linked to Prognostic Markers

Using the Enrichr online program (Enrichr), we generated a cluster gram out of the 81 genes from miRNA enrichment analysis, showing the top 10 most significant genes and pathways, as shown in the cluster gram in

Figure 6 and

Table 2.

4. Discussion

Ovarian cancer (OC) remains a highly lethal disease due to the absence of early symptoms and the frequent development of recurrence and chemoresistance. As a result, identifying reliable biomarkers for early diagnosis and predicting therapeutic response is critical to improving patient outcomes [

25]. While BRCA1/2 mutation testing is a current standard for families with a strong history of OC, and may reduce mortality by up to 10% [

6], only a small proportion of patients carry these mutations. This underscores the need for additional prognostic markers, particularly those linked to chemoresistance [

26].

In our study, we identified three promising prognostic markers—ITGB1, TIMP3, and BRAF—using data from the Human Protein Atlas (

www.proteinatlas.org). miRNAs targeting these genes were predicted using TargetScanHuman 8.0 and prioritized with miRTargetLink 2.0, highlighting hsa-miR-192-5p, hsa-miR-143-3p, and miR-30d as key candidates (see

Supplementary Table S2). The identified gene set (n=81) was analyzed using Enrichr, revealing that “proteoglycans in cancer” and “cell cycle” pathways were among the most enriched. Notably, ITGB1, TIMP3, and BRAF showed strong interactions with hsa-miR-143-3p, while hsa-miR-192-5p and miR-30d were broadly connected to genes associated with these prognostic markers.

Among these, hsa-miR-143-3p was found to be downregulated in our samples, although not significantly (p=0.258). This miRNA is typically downregulated in many malignancies and influences tumor progression by regulating targets such as ITGB1, which has been shown to promote invasion and metastasis [

27,

28]. In serous ovarian cancer (SOC), targeting ITGB1 with hsa-miR-143-3p may reduce tumor aggressiveness and improve therapeutic outcomes. miRTargetLink2.0 also identified hsa-miR-124-3p as a potential regulator of ITGB1, previously studied in pancreatic cancer [

29]. Overexpression of ITGB1 is associated with chemoresistance and poor outcomes in high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) [

25,

30,

31].

Similarly, miR-30d was downregulated in our cohort (p=0.5169), and has been implicated in the regulation of TIMP3, a tumor suppressor involved in apoptosis, anti-angiogenesis, and ECM remodeling [

32,

33]. Reduced TIMP3 expression often due to promoter methylation or miRNA suppression is linked to poor prognosis in several cancers, including ovarian [

34,

35,

36,

37]. In this context, miR–30d–mediated suppression of TIMP3 could enhance tumor invasiveness and resistance to therapy.

We also examined the prognostic relevance of BRAF, which is associated with favorable outcomes in certain ovarian cancer subtypes, such as serous borderline tumors and low-grade serous carcinomas. [

38]. Research in lung cancer shows that hsa-miR-143-3p can directly target BRAF, inhibiting cell proliferation and reducing chemoresistance [

38], suggesting a broader applicability across cancer types.

Across our LLU and TCGA cohorts, we observed that miR-192, miR-30d, hsa-miR-16-1-5p, miR-143-3p, and miR-20a-5p were differentially expressed between African American and Caucasian patients. Although these differences were not statistically significant, their dysregulation in the context of specific prognostic markers supports their relevance in exploring racial disparities in ovarian cancer outcomes. In future analyses, we will perform miRNA sequencing to validate the expression patterns of these miRNAs.

Emerging evidence suggests that miR-192-5p, for example, can suppress cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), while promoting apoptosis in some cancers [

39]. Understanding how miRNA alterations—whether driven by mutations, polymorphisms, or epigenetic modifications—differ across racial groups could shed light on mechanisms underlying ovarian cancer disparities and identify novel therapeutic targets.

Overall, our findings underscore the critical role of miRNAs in modulating oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. These molecular interactions influence disease progression, chemoresistance, and patient survival, and highlight miRNAs as valuable tools for prognosis and targeted therapy development in ovarian cancer.

Future direction:

Small sample sizes of minority women in individual studies limit the statistical power to fully evaluate the impact of environmental, genetic, and clinical factors on ovarian cancer risk and survival within these populations. Therefore, in future studies, we aim to validate our findings by analyzing a larger cohort of samples from individuals of African ancestry. We plan to increase the sample size and comprehensively assay all miRNAs associated with the ITGB1, TIMP3, and BRAF genes. Our long-term objective is to investigate the therapeutic potential of miRNA mimics and inhibitors in ovarian cancer, using both in vitro and in vivo models, to develop targeted treatments for aggressive tumor subtypes.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study identifies ITGB1, TIMP3, and BRAF, along with their associated miRNAs, as promising prognostic markers and potential therapeutic targets in ovarian cancer. Through integrated bioinformatic analyses, we demonstrate that dysregulation of hsa-miR-143-3p, miR-30d, and miR-192-5p may contribute to chemoresistance and tumor progression, particularly in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Although our current findings are limited by small sample sizes, especially among minority populations, they highlight the importance of miRNA-mediated regulation in ovarian cancer biology and suggest new avenues for addressing racial disparities. Future efforts will focus on validating these results in larger, more diverse cohorts and exploring the therapeutic potential of miRNA-based interventions to improve outcomes for patients with aggressive disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Jane Muinde: Performed miRNA extraction from both FFPEs and Fresh Tissue samples, cDNA synthesis, RT-qPCR, Δ Ct value analysis, miRTargetLink analysis, gene enrichment analysis, and compiled original manuscript. Skyler: Helped with miRNA extraction, miRNA analysis using UALCAN software. Romi: MiRNA extraction from FFPE and fresh tissue samples, cDNA synthesis, and TR-qPCR, offered technical support Umang: Software and Statistical Analysis. Dr. Carter: Provided FFPE tumour samples, performed analysis of data, review, and editing. Dr. Kremsky: Offered guidance and design on performing Online miRTarget Link, Enrichr analysis of target genes, review, and editing. Dr. MirShahidi: Provided Fresh tissue tumour samples, review, and editing. Dr. Salma Khan: Principal Investigator, Conceptualization, Provided research guidance and resources for this project, supervision, review and editing

Data Availbility Statement

Protocol Title

LLUCC Biospecimen Lab IRB approval Number: 58238.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Carter and Dr. Mirshahidi for assisting with archival tumour samples. We also thank Dr. Unternaehrer for assisting with RT-qPCR data analysis and Dr. Suzanne Philips, Chair of the Earth and Biological Sciences, for her constant support. We thank Dr. Schulte for assisting with overall survival analysis. Finally, we thank the Center for Health Disparities and Molecular Medicine for providing the resources we needed for this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ITGB1 |

Integrin beta-1 |

| BRAF |

B-Raf Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase |

| TIMP3 |

TIMP Metallopeptidase Inhibitor 3 |

| LLU |

Loma Linda University |

References

- Shaik, B., et al. An Overview of Ovarian Cancer: Molecular Processes Involved and Development of Target-based Chemotherapeutics. Curr Top Med Chem 2021, 21, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, A., et al. The multiple facets of ovarian high grade serous carcinoma: A review on morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular features. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2025, 208, 104603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaia-Oltean, A.I., et al. The shifting landscape of genetic alterations separating endometriosis and ovarian endometrioid carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res 2021, 11, 1754–1769. [Google Scholar]

- Peres, L.C. and J.M. Schildkraut, Racial/ethnic disparities in ovarian cancer research. Adv Cancer Res, 2020. 146: p. 1-21.

- Srivastava, S.K., et al., Racial health disparities in ovarian cancer: not just black and white. Journal of Ovarian Research, 2017. 10(1): p. 58.

- Sathipati, S.Y. and S.Y. Ho, Identification of the miRNA signature associated with survival in patients with ovarian cancer. Aging (Albany NY), 2021. 13(9): p. 12660-12690.

- Wang, L., et al. Drug resistance in ovarian cancer: from mechanism to clinical trial. Mol Cancer 2024, 23, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshamrani, A.A., Roles of microRNAs in Ovarian Cancer Tumorigenesis: Two Decades Later, What Have We Learned? Front Oncol, 2020. 10: p. 1084.

- Ismail, A., et al., The role of miRNAs in ovarian cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic resistance – A focus on signaling pathways interplay. Pathology - Research and Practice, 2022. 240: p. 154222.

- Rawlings-Goss, R.A., M.C. Campbell, and S.A. Tishkoff. Global population-specific variation in miRNA associated with cancer risk and clinical biomarkers. BMC Medical Genomics 2014, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Malley, D.M., et al., PARP Inhibitors in Ovarian Cancer: A Review. Target Oncol, 2023. 18(4): p. 471-503.

- Dochez, V., et al., Biomarkers and algorithms for diagnosis of ovarian cancer: CA125, HE4, RMI and ROMA, a review. J Ovarian Res, 2019. 12(1): p. 28.

- Huang, J., W. Hu, and A.K. Sood. Prognostic biomarkers in ovarian cancer. Cancer Biomark 2010, 8, 231–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. and W. Zou. Inhibition of integrin β1 decreases the malignancy of ovarian cancer cells and potentiates anticancer therapy via the FAK/STAT1 signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep 2015, 12, 7869–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T., et al., The prognostic value of ITGA and ITGB superfamily members in patients with high grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell Int, 2020. 20: p. 257.

- Hakamy, S., et al., Assessment of prognostic value of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP3) protein in ovarian cancer. Libyan J Med, 2021. 16(1): p. 1937866.

- Lee, W.T., et al., Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 3: Unravelling Its Biological Function and Significance in Oncology. Int J Mol Sci, 2024. 25(6).

- Moujaber, T., et al., BRAF Mutations in Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer and Response to BRAF Inhibition. JCO Precis Oncol, 2018. 2: p. 1-14.

- Abrehdari-Tafreshi, Z., et al., The Role of miR-29a and miR-143 on the Anti-apoptotic MCL-1/cIAP-2 Genes Expression in EGFR Mutated Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma Patients. Biochemical Genetics, 2024. 62(6): p. 4929-4951.

- Rood, K., et al. Regulatory and Interacting Partners of PDLIM7 in Thyroid Cancer. Current Oncology, 2023. 30, 10450-10462. [CrossRef]

- Agostini, A., et al., The microRNA miR-192/215 family is upregulated in mucinous ovarian carcinomas. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 11069.

- Chandrashekar, D.S., et al. UALCAN: A Portal for Facilitating Tumor Subgroup Gene Expression and Survival Analyses. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, F., et al., miRTargetLink 2.0-interactive miRNA target gene and target pathway networks. Nucleic Acids Res, 2021. 49(W1): p. W409-w416.

- Kuleshov, M.V., et al., Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016. 44(W1): p. W90-7.

- Han, J. and L. Lyu, Identification of the biological functions and chemo-therapeutic responses of ITGB superfamily in ovarian cancer. Discov Oncol, 2024. 15(1): p. 198.

- Zheng, H.C., The molecular mechanisms of chemoresistance in cancers. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(35): p. 59950-59964.

- Wu, J., et al., Biological functions and potential mechanisms of miR-143-3p in cancers (Review). Oncol Rep, 2024. 52(3).

- Ju, Y., et al., Identification of miR-143-3p as a diagnostic biomarker in gastric cancer. BMC Medical Genomics, 2023. 16(1): p. 135.

- Idichi, T., et al., Involvement of anti-tumor miR-124-3p and its targets in the pathogenesis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: direct regulation of ITGA3 and ITGB1 by miR-124-3p. Oncotarget, 2018. 9(48): p. 28849-28865.

- Piperigkou, Z., et al., The microRNA-cell surface proteoglycan axis in cancer progression. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology, 2022. 322(5): p. C825-C832.

- Su, C., et al., Integrinβ-1 in disorders and cancers: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Cell Communication and Signaling, 2024. 22(1): p. 71.

- Sun, B. , et al., MicroRNA-30d target TIMP3 induces pituitary tumor cell growth and invasion. Gland Surg, 2021. 10(12): p. 3314-3323.

- Fan, D. and Z. Kassiri, Biology of Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP3), and Its Therapeutic Implications in Cardiovascular Pathology. Front Physiol, 2020. 11: p. 661.

- Li, X. , et al., Targeting INHBA in Ovarian Cancer Cells Suppresses Cancer Xenograft Growth by Attenuating Stromal Fibroblast Activation. Dis Markers, 2019. 2019: p. 7275289.

- Gu, X. , et al., TIMP-3 Expression Associates with Malignant Behaviors and Predicts Favorable Survival in HCC. PLOS ONE, 2014. 9(8): p. e106161.

- Escalona, R.M., et al., Expression of TIMPs and MMPs in Ovarian Tumors, Ascites, Ascites-Derived Cells, and Cancer Cell Lines: Characteristic Modulatory Response Before and After Chemotherapy Treatment. Frontiers in Oncology, 2022. Volume 11 - 2021.

- Lee, W.-T., P.-Y. Wu, and Y.-F. Huang, EP265/#388 TIMP3 attenuates aggressiveness of ovarian cancer cells and enhances the sensitivity to paclitaxel. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, 2023. 33: p. A186-A187.

- Perrone, C., et al., Targeting BRAF pathway in low-grade serous ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol, 2024. 35(4): p. e104.

- Fu, S., et al., MiR-192-5p inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion in papillary thyroid carcinoma cells by regulation of SH3RF3. Biosci Rep, 2021. 41(9).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).