1. Introduction

Research in corpus linguistics has found that the informativity of a word predicts its degree of articulatory reduction above and beyond the unit’s predictability given the current context [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. These findings have been interpreted as evidence for speakers being sensitive to a word’s information content in deciding how to pronounce it, and for long-term memory representations of words accumulating information about its predictability or pronunciation details or both [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The effects of informativity are remarkably consistent in that all studies that have found an effect of local predictability also found an effect of informativity, suggesting that whenever speakers are sensitive to the probability of a word given a particular context, this information also accumulates in memory in association with that word. Consequently, these effects provide support for ‘rich memory’ views of the mental lexicon, in which every episode of producing or perceiving a word leaves a trace [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

However, the predictability of a word in a context is not independent of its average predictability, which is the inverse of informativity and is therefore perfectly correlated with it. Furthermore, when a context is rare, the word’s predictability given that context is unreliable and can be improved by taking the word’s average predictability into account. To take an extreme example, suppose that the word inched occurs only once in the corpus. Then all words following it would have a probability of zero, except for the word that happened to occur after it (let’s say closer), which would have a probability of 1. These estimates are highly unreliable, since they are based on a sample size of 1. By taking into account probabilities of words in other contexts, we might be able to estimate, for example, that up is a lot more probable than higher given inched.

In inferential statistics, this observation is behind the idea of hierarchical / mixed-effects models, which make use of adaptive partial pooling of evidence [

24]. In estimating some variable in some context, partial pooling relies on observations from that context to the extent that they are available, because they are more relevant than observations from other contexts. But the fewer such observations are available, the more the model’s estimate is based on observations from other contexts. It can be shown that the estimate resulting from partial pooling is generally more accurate than an estimate that does not take other contexts into account (for simulations in the context of estimating reduction probabilities, see [

25]). In corpus data, context frequency is 1 for a large proportion of contexts. For example, if context is operationalized as the preceding or following word, as in [

1], context frequency would be 1 for ~50% of contexts in any corpus, as shown in [

26]. Therefore partial pooling would yield substantial benefits in estimating predictability from naturalistic language input compared to relying completely on observed predictability given context. If speakers estimate predictability in context, it would therefore behoove them to rely on partial pooling to do so [

17].

How does partial pooling work? In hierarchical regression [

24], the partial pooling estimate for some characteristic (

) of a word (

w) in a context (

cx) would be estimated by Equation (1):

Here,

is the number of observations (frequency) of the context

cx,

is the observed variance of the characteristic (

) across words in the context

cx, and

is the variance of average

across words (

being averaged across all contexts in which each word occurs). Equation (1) says that the estimate based on the current context (

, here predictability) is weighted more when the context is frequent (

is high), and words tend not to vary in

within that context. Conversely, the estimate based on other contexts (informativity) is weighted more when words (within the relevant class) tend not to differ in (

). If

is predictability of the word given context, the variance parameters are relatively unimportant because word predictability distributions within and across contexts are both scale-free with an exponent of ~1, i.e., Zipfian [

26,

27], so

and

tend not to vary, while

, which also follows a scale-free Zipfian distribution, varies enormously across contexts. Therefore, the main influence on the importance of observed local predictability (

) vs. observed informativity (

) in estimating local predictability (

) given a context should be the frequency of that context.

The present paper demonstrates that, as expected from the reasoning above, the apparent effect of informativity is larger in rare contexts than in frequent ones, while the effect of local, contextual predictability is smaller in rare contexts. This follows directly from the fact that contextual predictability estimates are less reliable in rare contexts, and that informativity can help improve these estimates via partial pooling. Previous simulation work on this question in [

28] has investigated whether the

segmental informativity effect observed in [

29] could be spurious. However, even the rarest segments like [ð] or [ʒ] in English are very frequent relative to the average word, and therefore sampling noise is far less of a concern on the segmental level than on the lexical level examined here and in [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Thus, it is important to demonstrate that the effects of lexical informativity too cannot be explained by sampling noise in predictability.

We show, by simulation, that a significant effect of informativity and its greater magnitude in rare contexts could sometimes be due to sampling noise in the predictability estimates. We present a simple simulation approach to estimate how much of an observed effect of informativity is spurious, i.e., due to sampling noise. For our actual example, however, much of the effect of informativity is not due to sampling noise in predictability estimates. That is, although corpus data could show a significant effect of informativity in the same direction even if speakers showed no real sensitivity to informativity, our simulations show that the magnitude of that spurious effect would rarely be as large as the effect in the real data.

2. Materials and Methods

We begin by demonstrating that predictability and informativity behave as one would expect if (some of) the effect of informativity were due to partial pooling, i.e., informativity helping reduce noise in predictability estimates. Because there is more noise in smaller samples, this involves showing that these predictors interact with context frequency, such that the effect of predictability is stronger in frequent contexts and the effect of informativity is stronger in rare ones. We show this by fitting a regression model, predicting word duration (log scaled) from predictability, informativity and their interactions with context. We begin with a simple least squares linear regression model, fit using lm() in base R, and then check whether the interactions with context frequency are non-linear by using the generalized additive model, as implemented in the bam() function in the mgcv package in R.

The data come from the Switchboard Corpus [

30], using the revised word-to-speech alignments from [

31]. Specifically, to somewhat control prosody and availability of following context, we selected the words that followed repetition disfluencies in [

32]. For these words (

n = 5146), probabilities given the preceding word are available as are probabilities derived from an LSTM network [

33] trained on the same corpus (randomly reordered several times to remove order effects) in [

32]. We operationalize context as the preceding word in the utterance, so predictability is

, i.e., forward bigram surprisal with a flipped sign, and informativity is the expected surprisal averaged across contexts.

Bigram surprisal was chosen over LSTM surprisal because [

32] reports that the two operationalizations of contextual predictability are highly correlated for this sample of words (sharing >81% of variance) and the bigram operationalization makes it easier to determine which two contexts are ‘the same’ for the purposes of calculating context frequency. That is, words that end in the same word are ‘the same context’ for the present study. We return to this decision in the discussion.

Words that follow a repetition disfluency were chosen because they are relatively controlled for other factors that influence durations: they are almost always nouns following high-frequency function words (prepositions or articles) [

32], and surrounding words outside of the disfluency itself have little influence on their durations [

34,

35]. This makes the preceding local context an especially strong predictor in this context. However, this is a somewhat arbitrary choice, and any other set of words could be used to make the same point, since the results follow just from the existence of noise in the predictability estimates obtained from any corpus and the Law of Large Numbers. For example, see [

11] for an application of this method to word durations in a Polish corpus.

After showing that the effects of informativity and predictability interacts with context frequency as expected if informativity effects were due to partial pooling, we investigate how much of the informativity effect is likely to be spurious – i.e., partial pooling helping with mismatch between corpus predictability estimates and the predictability values actually driving reduction within the speaker.

To do this, we repeatedly generate data samples in which predictability has the bivariate relationship with duration observed in the real data while informativity has no effect, i.e., the variance not accounted for by predictability is random noise. We generate the same Zipfian distribution of context frequencies as in the real data, but there is no correlation between the true magnitude of the effect of predictability and context frequency. That is, the magnitude of the predictability effect is constant across contexts. We then fit the same model we fit to the real data, with predictability and informativity as predictors, with or without context frequency and interactions with it. We ask: 1) how often do we get a ‘false alarm’ on informativity: how often do we observe a significant effect of informativity (at p < .05) in the same direction as in the real data, even though the data are generated by a process in which there is no true effect of informativity, and 2) how often is that effect at least as large as the effect in the real data.

While average predictability is the same as in the real data in these simulations, and constant across contexts, predictability in each context is subject to sampling noise. That is, feeds into a binomial distribution with context frequency serving as the number of trials. On each ‘trial’, i.e., token of the preceding word, a biased coin is tossed, which come up heads with the probability given by ’s probability given the preceding word, . This process inevitably produces sampling noise. For example, if you toss a coin that has a 50% probability of coming up heads 5 times, the coin will not come up heads on exactly 2.5 occasions. The effect of this sampling noise is what adding informativity to the regression model can alleviate.

We then investigate whether there is an upper bound on the magnitude of the spurious effect of informativity by injecting increasing amounts of noise in the predictability estimates. In reality, corpus probabilities diverge from probabilities experienced by the speaker in ways that go beyond sampling noise in the strict sense: the corpus is not a faithful reflection of the speaker’s experience. Therefore, predictability estimates are noisier than the above sampling process estimates. We therefore add increasing random noise to the predictabilities, , transformed into log odds so that they can range from minus to plus infinity. This noise is again independent of context frequency in the simulations below, although this assumption can be relaxed. We examine the same two questions above: 1) how often do we detect a significant but spurious effect of informativity, and 2) how often is that effect at least as large as the effect in the real data. If increasing noise led to unbounded growth of both false alarm rates and effect sizes, then the study of informativity would be doomed, in that any effect of informativity could be attributed to noise in corpus predictabilities.

3. Results

3.1. Predictability, Informativity and Context Frequency

Table 1 and

Table 2 present the linear regression model results.

Table 1 presents an analysis in which predictability and informativity jointly predict duration, as in previous work. The two predictors together explain 43.9% of variance in duration. Most of the variance in duration explained by informativity is also explained by predictability and vice versa. Thus, removing the effect of informativity from the model in

Table 1 reduces adjusted

R2 to 38.9%, while removing predictability reduces it to 40.7%.

The model in

Table 2 adds interactions with context frequency predicted by partial pooling.

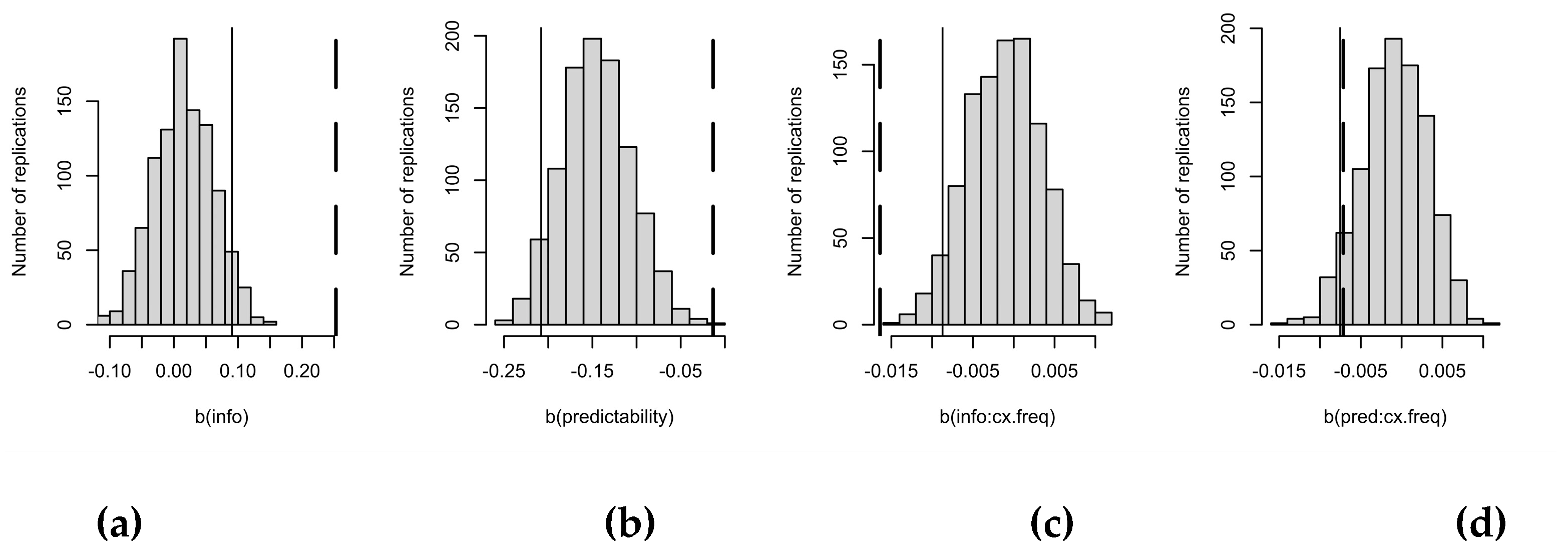

Figure 1 plots these interactions. Adding the interactions improves the model significantly (

F(3,5060) = 27.842,

p < .00001), though not by much (improving adjusted

R2 by 0.9% from 43.9% to 44.8%).

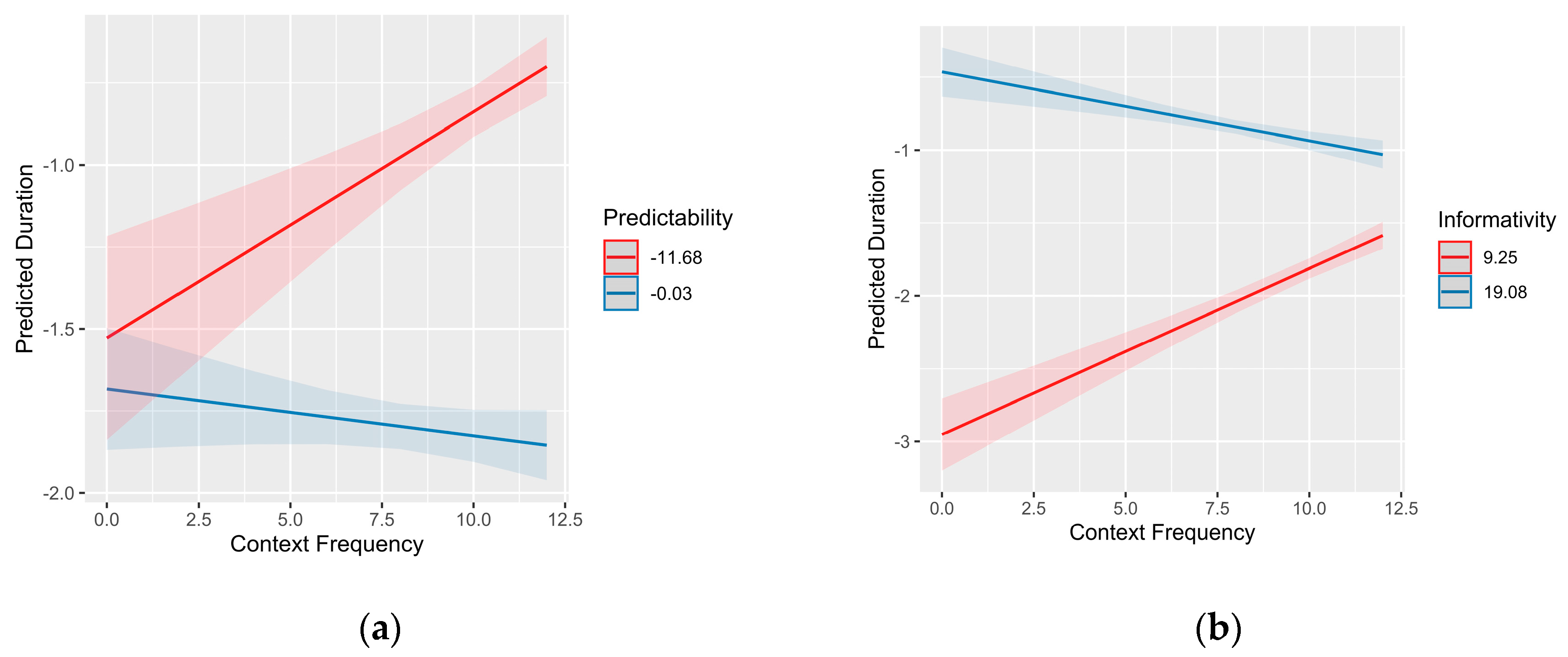

Figure 1a shows that the effect of predictability increases with context frequency, such that there is no effect of predictability given a novel context (i.e., a word of frequency 1 / log frequency 0).

Figure 1b shows that, conversely, the effect of informativity decreases as context frequency increases. These interactions are as one would expect from partial pooling: predictability given context cannot be estimated well when the context is rare, and this is where informativity can best help estimate predictability. The directions of the effects of predictability and informativity are in the expected directions: words are shorter when they are predictable from the current context, and longer when they are (on average) informative.

3.2. Simulating What Would Happen If There Were No Informativity Effect

As described in the methods, we created 10,000 simulated datasets in which there was no real effect of informativity, and no real correlation between the effect of predictability and context frequency, but the main effect of predictability, the distribution of context frequencies, and the amount of noise were the same as in the real data. Predictability was generated by sampling from a binomial distribution, i.e., for each context, flipping a coin with probability corresponding to true predictability n times, and then noting the resulting sample predictability value.

Because previous studies on informativity did not look for interactions with context frequency, we begin with a model in which only main effects of predictability and informativity are fit.

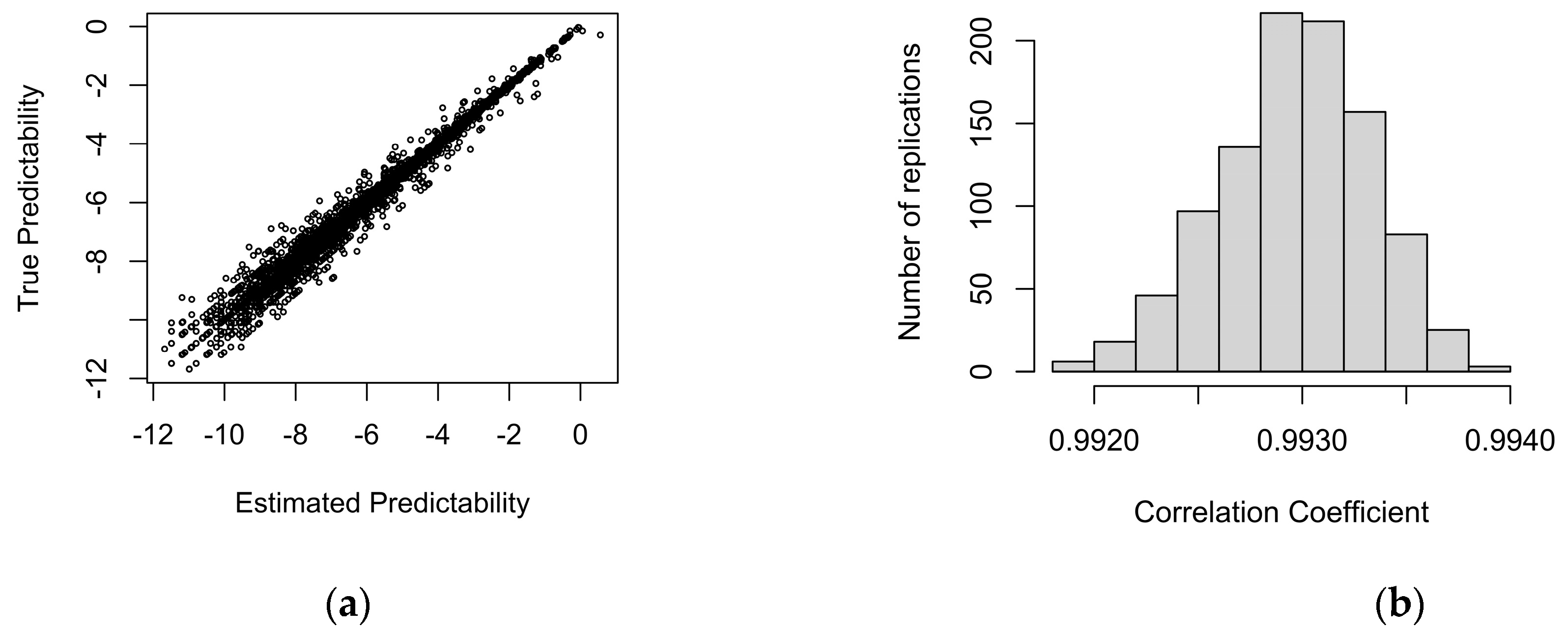

Figure 2 shows that true predictability and sample predictability are highly correlated, with r > .99.

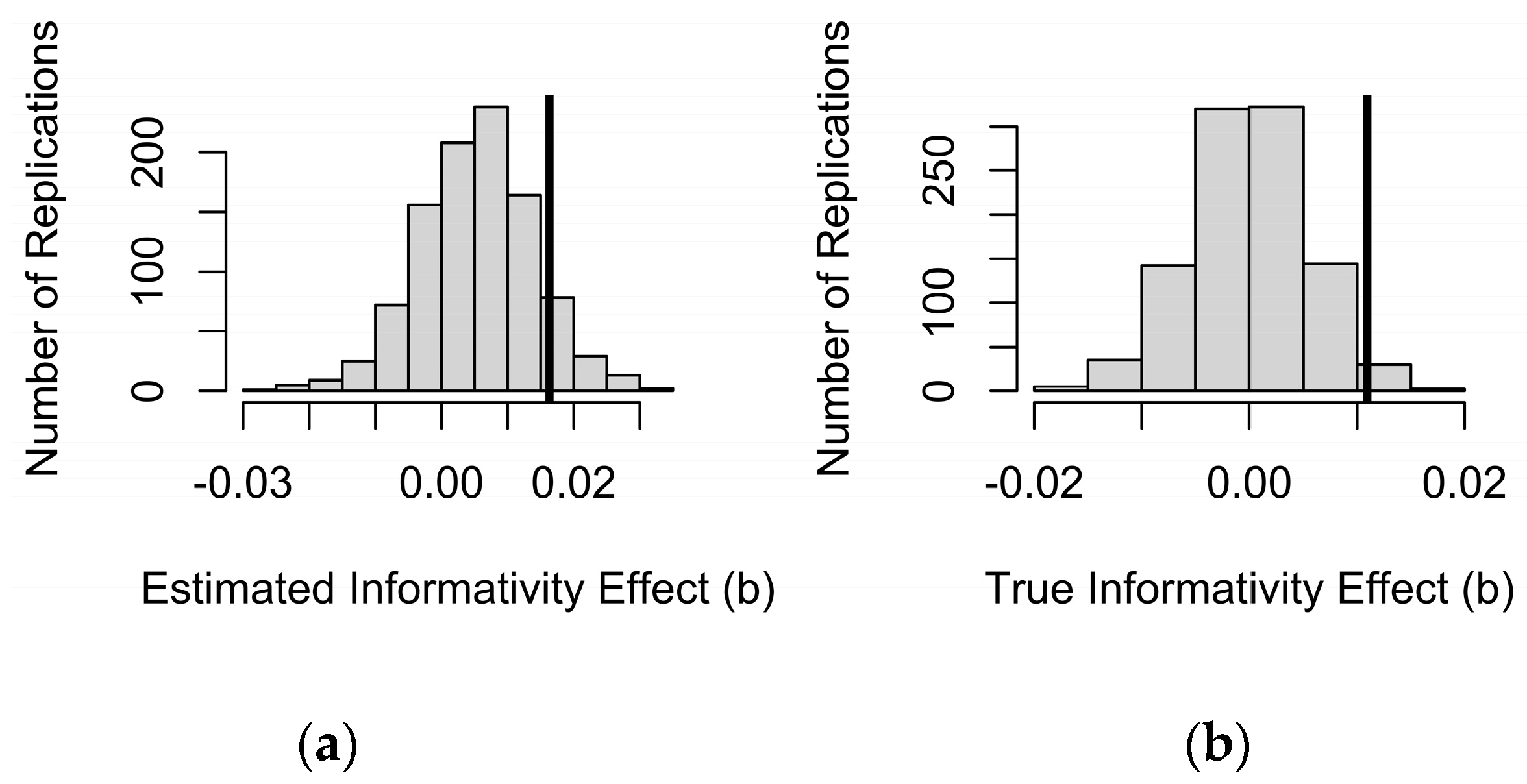

Despite this strong correlation, the divergence between true predictability and sample predictability is sufficient for informativity to have a significant (but spurious) effect at the .05 alpha level more than 9% of the time when probability and informativity are estimated from the sample (

Figure 3a). Furthermore, this spurious effect of informativity is usually in the same, theoretically motivated direction as in the real data (73% of the coefficients in

Figure 3a are positive, and 91% of significant coefficients are). Of course, if this test were perfectly calibrated, then it should have come out significant by chance 5% of the time, and be positive or negative about equally often. This is what we observe in

Figure 3b, where the (unobtainable in practice) true predictability and informativity values are used as predictors instead of their values in the simulated data sample. Thus, the small amount of sampling noise seen in

Figure 2 is enough to double the false alarms rate, if we simply accept that an observed effect of informativity is a true effect as long as it is significant in a regression model that also includes predictability.

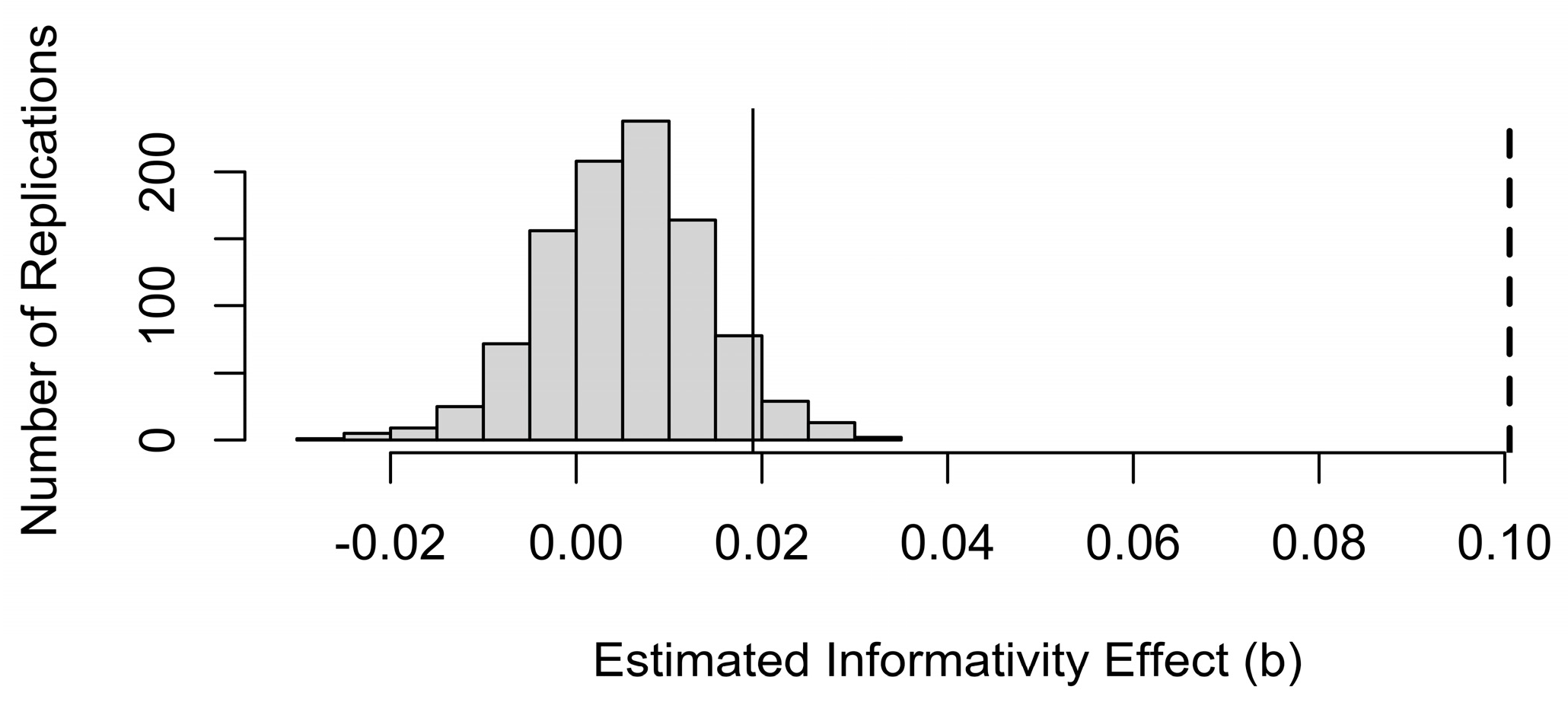

However,

Figure 4 shows that the observed size of the informativity coefficient, shown by the vertical dashed line, is much larger than the coefficients obtained in the simulated samples, where there is no true effect of informativity. Thus, although a significant effect of informativity could be spurious, an effect of the size we observed is unlikely to be due to sampling noise alone. Since we made 1,000 simulations, p < 1/1,000 or .001.

3.3. Beyond Sampling Noise

The results in

Figure 4 are encouraging, in that the spurious contribution to the effect of informativity in the real data appears to be relatively small – most of the observed effect looks real. However,

Figure 4 may be underestimating the noise in predictability estimates because it assumes that the predictabilities that feed into the binomial distribution generating the word counts in the corpus always match the predictabilities in the speakers’ experience that are driving reduction. In reality, this is of course not true. Thus, we inject varying amounts of noise into these underlying predictabilities to simulate the potential for mismatch between true predictability (in a speaker’s experience) and predictability in the corpus.

Specifically, the injected noise is randomly distributed on the log odds scale, both for context probability and for word probability given context. Context frequencies are then drawn from a multinomial distribution, with the summed context frequency the same as in the real data. Each word’s number of tokens in a particular context is drawn from a binomial distribution with probability of drawing the word based on its (noisified) probability given context, and the number of trials equal to the (noisified) context frequency. The resulting word frequency in context was divided by frequency in context to yield speaker’s predictability in context, which fed into the calculation of speaker’s informativity. Speaker’s predictability operationalizes the probability of the word given context in the speaker’s experience, which we assume is generated from the underlying community probability by the bi/multinomial sampling process described above. Speaker’s predictability was used to generate word durations by using the predictability coefficient from the model of real data and adding Gaussian noise matching the residuals in the model of real data (

Table 1). Predictabilities and informativities calculated from the real corpus served as corpus estimates of predictability and informativity to compare with the speakers’ predictability and informativity.

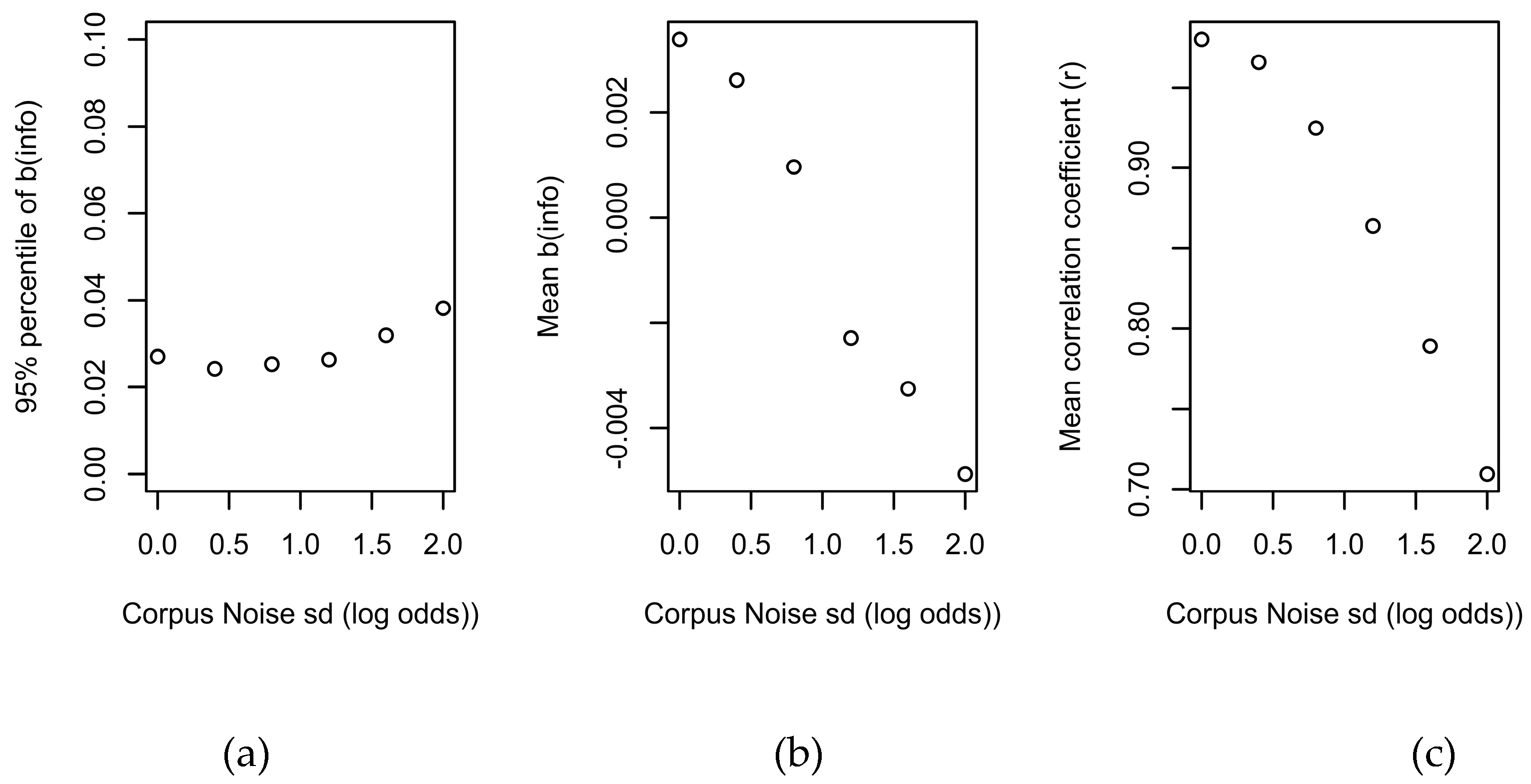

Figure 5a shows the relationship between noise level and the 95% percentile on the sampling distribution of informativity coefficients shown as the thin vertical line in

Figure 4. Recall that the worry was that, as noise level increases – i.e., as corpus probabilities deviate from the probabilities in the speaker’s experience – informativity would become more and more likely to yield an effect as large as the one we observed in the data (shown by the dashed line in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5a).

Figure 5a suggests that this is unlikely: large spurious informativity coefficients do become slightly more likely with increading noise, as shown in (a). However, this is a small increase, and the mean value of the spurious informativity coefficient actually decreases, becoming negative, as shown in (b). Thus, the increase in (a) is because of increasing variability across replications with increased noise, and not because of increasing bias. The bias in favor of a spurious positive informativity effect is actually highest when corpus probabilities match the probabilities that generated the data well.

Figure 5c shows that the correlation between corpus and speaker log probabilities is surprisingly robust to the injection of noise, so that even noise with a standard deviation of 2 on the log odds scale reduces the correlation only to 0.7. This is likely because the log transformation eliminates all zero probabilities from the sample (since they become infinite). By the time noise reaches 2, sample size has shrunk from 2302 to 1162. It is therefore almost impossible to inject enough noise into the log probabilities for the 95% percentile to approach the coefficient observed in the real data (0.1, at the top of

Figure 5a). Therefore, mismatch between the probabilities driving reduction and corpus probabilities is unlikely to explain away informativity effects.

3.4. Interactions with Context Frequency

So far we have examined whether the main effect of informativity in

Table 1 could be spurious, and we have concluded that much of it is not. What of the predictability:context.frequency and informativity:context.frequency effects in

Table 2? How much of these interactions is likely due to partial pooling helping address sampling noise in predictability? We repeat the sampling procedure in

Section 3.2, but now fit the models in

Table 1 and

Table 2. In these simulations, there is no effect of informativity and no true interactions, and all of the variance shared between predictability and informativity is due to predictability (as assumed by the model in

Table 1 that did not include an informativity predictor).

As shown in

Figure 4a, the simple effect of informativity is stronger than expected, while

Figure 4b shows that the simple effect of predictability is weaker than expected if all of the variance shared between informativity and predictability were attributable to predictability. Thus, again some of the informativity effect appears to not be spurious. Furthermore, much of the interaction of informativity with context frequency in

Figure 1b appears to be real (

Figure 4c). That is, the effect of informativity may genuinely be greater in rare contexts: this is not just due to sampling noise in predictability estimates. In contrast,

Figure 4d shows that all of the interaction of predictability with context frequency in

Figure 1a is potentially spurious (with the alpha level at .05), due to the greater sampling noise in predictability estimates based on rare contexts, despite its low p value in

Table 2.

Figure 6.

Fitting the full model in

Table 2 to data generated without any true effect of informativity and no speaker/corpus probability mismatch. Dashed lines show observed coefficients from

Table 2. Thin solid lines show the critical value of the coefficient in the same direction. Simple effect of informativity in (a), and of predictability in (b), and interactions of context frequency with informativity in (c) and with predictability in (d).

Figure 6.

Fitting the full model in

Table 2 to data generated without any true effect of informativity and no speaker/corpus probability mismatch. Dashed lines show observed coefficients from

Table 2. Thin solid lines show the critical value of the coefficient in the same direction. Simple effect of informativity in (a), and of predictability in (b), and interactions of context frequency with informativity in (c) and with predictability in (d).

4. Discussion

Informative words have been repeatedly observed to be longer than less informative words. Furthermore, the effect of informativity has been observed to hold even if predictability given the local context is included in the regression model of word duration. The present paper pointed out that informativity could improve local predictability estimates because of sampling noise in the latter, especially in rare contexts. This means that one would expect some effect of informativity to come out in a regression model that includes predictability even if reduction were driven by predictability alone.

We then examined by simulation whether an effect of informativity observed in a real dataset is small enough to have emerged from sampling noise, or from a mismatch between corpus probabilities and the probabilities driving reduction, in a world where differences in word duration were entirely due to predictability in the local context. We have shown that there is bias in informativity coefficient estimates: a spurious effect of informativity does come out significant and in the expected direction (showing an effect in the opposite direction of the reductive effect of predictability) more often than the p value in a regression model that includes both predictability and informativity would lead us to expect. However, the effect is smaller than the one observed in the real data, and does not increase with increasing mismatch between corpus probabilities and the true probabilities driving reduction. Therefore, we can conclude that the effect of informativity in the real data is unlikely to be entirely attributable to sampling noise in predictability estimates.

We also showed that predictability and informativity interact with context frequency as one would expect from the predictability estimates being less reliable when they are conditioned on rare contexts. These interactions with context frequency are new effects, not previously tested in the literature, but predicted by the idea of informativity effects being due to adaptive partial pooling of probabilities across contexts. Our simulations show that the interaction of predictability with context frequency observed in the real data might be attributable to this effect of the Law of Large Numbers (i.e., p>.05). However, some of the interaction of informativity with context frequency is not attributable to there being more noise in predictability estimates for informativity to compensate for in rare contexts. So, overall, not all of the effect of informativity is attributable to predictability, and the effect of informativity may genuinely be stronger in rare contexts.

This result extends prior simulation work in [

37] that showed that the segmental informativity effect observed in [

38] (e.g., [t] is less informative and more likely to be deleted than [k] in English) could not be attributed to noise in local predictability estimates. Like [

28], we observe that most of the effect of informativity in the real data is not due to noise in predictability estimates. However, this result is more surprising on the lexical level examined here than on the segmental level examined in [

28], because segmental contexts are abundantly frequent and few in number, and therefore sampling noise in predictability is rather low at the segmental level. In contrast, word frequency distributions are Zipfian, with half the words occurring only once in the corpus, resulting in many contexts where estimating local predictability is virtually impossible.

Of course, the present work shows only that the effect of informativity in the data cannot be explained by local predictability. It therefore leaves open the possibility that other stable characteristics of words that do not change across contexts and correlate with informativity would explain away the informativity effect. We do not consider this likely because previous work in [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] has addressed many of these potential explanations. However, if some of the effect of informativity in the regression models fit by these previous studies could be due to noise in predictability estimates, the possibility that the remainder of the informativity effect is explained away by other stable, context-independent but word-specific factors remains open (e.g., [

36]). The methodology proposed here can incorporate such additional predictors, by creating simulated data in which all predictors but informativity have the effects they do in the real data, fitting a model with all predictors, including informativity, and testing how often we obtain an informativity effect of the observed magnitude and direction. This represents an important direction for future work.

A genuine effect of informativity, and its interaction with context frequency can be due to speakers themselves representing their linguistic experience in a way that results in adaptive partial pooling, as argued in [

17] and [

37]. Adaptive partial pooling is directly predicted by probabilistic models of the mind [

17,

37,

38], which propose that the language learner engages in hierarchical inference, building rich structured representations and apportioning credit for the observations among them. However, it is also compatible with other “rich memory” models in which experienced observations are not discarded even if the learner generalizes over them. All such rich memory models can be understood as performing adaptive partial pooling at the time of production. For example, an exemplar / instance-based model stores specific production exemplars/instances tagged with contextual features [

39,

40]. It then produces a weighted average of the stored exemplars, with the weight reflecting overlap between the tags associated with each exemplar and the current context. The average is naturally dominated by exemplars that match the context exactly when such exemplars are numerous, and falls back on more distant exemplars when nearby exemplars are few. Modern deep neural networks also appear to be rich memory systems that implement a kind of hierarchical inference when generating text, in that best performance is achieved when the network is more than big enough to memorize the entire training corpus [

41,

42]. Increasing the size of the network beyond the point at which it can memorize everything appears to benefit the network specifically when the context frequency distribution is Zipfian [

43,

44], by allowing it to retrieve memorized examples when the context is familiar and to fall back on generalizing over similar contexts when it is not. The existence of implicit partial pooling in such models may be why attempts to add explicit partial pooling to them to improve generalization to novel contexts [

45] have led to limited improvements in performance.

Within the usage-based phonology literature, informativity effects have been considered to be one of a number of effects that go by the name of ‘frequency in favorable contexts’ (FFC). In general, the larger the proportion of a word’s tokens that occur in contexts that favor reduction, the more it will be reduced in other contexts [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Informative words can be seen as one type of low-FFC word, because (by definition of informativity) they tend to have low predictability given the contexts in which they occur. In this literature, informativity effects have been argued to be due to storage of phonetically detailed pronunciation tokens in the memory representations of words [

18,

19] and are therefore often thought to be categorically distinct from the online, in-the-moment reduction effects driven by predictability in the current context.

However, the distinction between informativity and local predictability may also be an artifact of how we traditionally operationalize the notion of ‘current context’. In reality, a word is never in exactly the same context twice. All contexts have a frequency of 1 if you look closely enough, and predictability of a word in a context always involves some generalization over contexts. That is, true predictability must always lie between predictability given the current context and average predictability across contexts (i.e., the inverse of informativity). The present paper treated contexts as being the same if they end in the same word. This is motivated by findings that the width of the context window does not appear to matter for predicting word duration (and other measures of word accessibility) from contextual predictability [

32,

46]. That is, language models with very narrow (one-word) and very broad windows generate upcoming word probabilities that are equally good at predicting word duration and fluency [

32,

46], suggesting that it is largely predictability given the preceding word that matters. However, [

46] nonetheless shows that a large language model (with a short context window) outperforms an ngram model in yielding predictability estimates predictive of word durations. It therefore seems likely that the notion of ‘current context’ in our studies is too narrow, and speakers actually generalize over the contexts that we considered distinct. For example, even if it is only the preceding word that matters, distributionally similar preceding words might behave alike, which a large language model would pick up on by using distributed semantics word representations (a.k.a. embeddings) instead of the local codes of an ngram model. Thus, another direction for future work is to try to determine what makes contexts alike in conditioning reduction.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the 2024 meeting of the Association for Laboratory Phonology in Seoul, Korea, and the 2024 annual meeting of the Cognitive Science Society in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Many thanks to the audience members for helpful discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Seyfarth, S. (2014). Word informativity influences acoustic duration: Effects of contextual predictability on lexical representation. Cognition, 133, 140-155. [CrossRef]

- Cohen Priva, U. (2015). Informativity affects consonant duration and deletion rates. Laboratory Phonology, 6(2), 243-278. [CrossRef]

- Sóskuthy, M., & Hay, J. (2017). Changing word usage predicts changing word durations in New Zealand English. Cognition, 166, 298-313. [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, J. K. (2018). Word length and the principle of least effort: language as an evolving, efficient code for information transfer. Ph.D. Dissertation, UCSD.

- Barth, D. (2019). Effects of average and specific context probability on reduction of function words BE and HAVE. Linguistics Vanguard, 5(1), 20180055. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, D. (2021). Probabilistic reduction and mental accumulation in Japanese: Frequency, contextual predictability, and average predictability. Journal of Phonetics, 87, 101061. [CrossRef]

- Tang, K., & Shaw, J. A. (2021). Prosody leaks into the memories of words. Cognition, 210, 104601. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. F. (2022). The interaction between predictability and pre-boundary lengthening on syllable duration in Taiwan Southern Min. Phonetica, 79(4), 315-352. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. F. (2023). Word-level and syllable-level predictability effects on syllable duration in Taiwan Mandarin. In Proceedings of the 20th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic, August 7-11 (pp.1350-1354).

- Wang, S. F. (2024). Contrast and predictability in the variability of tonal realizations in Taiwan Southern Min. In Proceedings of Speech Prosody 2024, July 2-5, Leiden, the Netherlands (pp. 542-546).

- Kaźmierski, K. (2025). The role of informativity and frequency in shaping word durations in English and in Polish. Speech Communication, 103239. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, T. F., & Buz, E. (2017). Signal reduction and linguistic encoding. In E. M. Fernández & H. S. Cairns (Eds.), The handbook of psycholinguistics, 38-81. Malden, MA: Wiley.

- Bybee, J. (2001). Phonology and language use. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Goldinger, S. D. (1998). Echoes of echoes? An episodic theory of lexical access. Psychological Review, 105(2), 251-279.

- Port, R. F., & Leary, A. P. (2005). Against formal phonology. Language, 81(4), 927-964. [CrossRef]

- Hall, K. C., Hume, E., Jaeger, T. F., & Wedel, A. (2018). The role of predictability in shaping phonological patterns. Linguistics Vanguard, 4(s2), 20170027. [CrossRef]

- Kapatsinski, V. (2021). Hierarchical inference in sound change: Words, sounds, and frequency of use. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 652664. [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. (2023). The long-term accrual in memory of contextual conditioning effects. In M. Díaz-Campos & S. Balasch (Eds.), The Handbook of Usage-Based Linguistics, 179-195. Malden, MA: Wiley.

- Kapatsinski, V. (2023). Understanding type and token frequency effects in usage-based linguistics. In M. Díaz-Campos & S. Balasch (Eds.), The Handbook of Usage-Based Linguistics, 91-106. Malden, MA: Wiley.

- Brown, E. K. (2020). The effect of forms’ ratio of conditioning on word-final /s/ voicing in Mexican Spanish. Languages, 5(4), 61. [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. L., Raymond, W. D., Brown, E. K., & File-Muriel, R. J. (2021). Lexically specific accumulation in memory of word and segment speech rates. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, 17(3), 625-651.

- Raymond, W. D., Brown, E. L., & Healy, A. F. (2016). Cumulative context effects and variant lexical representations: Word use and English final t/d deletion. Language Variation and Change, 28(2), 175-202. [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. K. (2023). Cumulative exposure to fast speech conditions duration of content words in English. Language Variation and Change, 35(2), 153-173. [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2007). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Barth, D., & Kapatsinski, V. (2018). Evaluating logistic mixed-effects models of corpus-linguistic data in light of lexical diffusion. In D. Speelman, K. Heylen & D. Geeraerts (Eds.), Mixed-effects regression models in linguistics, 99-116. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Baayen, R. H. (2001). Word frequency distributions. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Ellis, N. C., O’Donnell, M. B., & Römer, U. (2016). Does language Zipf right along? Investigating robustness in the latent structure of usage and acquisition. In J. Connor-Linton & L. Wander Amoroso (Eds.), Measured language: Quantitative approaches to acquisition, assessment and variation (pp.33-50). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Cohen Priva, U., & Jaeger, T. F. (2018). The interdependence of frequency, predictability, and informativity in the segmental domain. Linguistics Vanguard, 4(s2), 20170028.

- Cohen Priva, U. (2017). Informativity and the actuation of lenition. Language, 93(3), 569-597. [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, J. J., Holliman, E. C., & McDaniel, J. (1992). SWITCHBOARD: Telephone speech corpus for research and development. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, & Signal Processing (ICASSP) ’92, March 23-26, San Francisco, CA (pp. 517–520).

- Deshmukh, N., Ganapathiraju, A., Gleeson, A., Hamaker, J., & Picone, J. (1998). Resegmentation of SWITCHBOARD. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Spoken Language Processing (ICSLP), Nov 30 – Dec 4, Sydney, Australia, (pp.1543–1546).

- Harmon, Z., & Kapatsinski, V. (2021). A theory of repetition and retrieval in language production. Psychological Review, 128(6), 1112-1144. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S., & Schmidhuber, J. (1997). Long short-term memory. Neural Computation, 9(8), 1735–1780.

- Clark, T. H., Poliak, M., Regev, T., Haskins, A. J., Gibson, E., & Robertson, C. (2025). The relationship between surprisal, prosody, and backchannels in conversation reflects intelligibility-oriented pressures. Ms. https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/uydmx_v1.

- Dammalapati, S., Rajkumar, R., Ranjan, S., & Agarwal, S. (2021, February). Effects of duration, locality, and surprisal in speech disfluency prediction in English spontaneous speech. In Proceedings of the Society for Computation in Linguistics 2021, February 14-19, Held Online (pp. 91-101).

- Bybee, J., & Brown, E. K. (2024). The role of constructions in understanding predictability measures and their correspondence to word duration. Cognitive Linguistics, 35(3), 377-406. [CrossRef]

- Kleinschmidt, D. F., & Jaeger, T. F. (2015). Robust speech perception: recognize the familiar, generalize to the similar, and adapt to the novel. Psychological Review, 122(2), 148-203. [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell, T. J. (2015). Productivity and reuse in language: A theory of linguistic computation and storage. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Pierrehumbert, J. B. (2002). Word-specific phonetics. In C. Gussenhoven & N. Warner (Eds.), Laboratory phonology 7 (pp.101-140). Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Jamieson, R. K., Johns, B. T., Vokey, J. R., & Jones, M. N. (2022). Instance theory as a domain-general framework for cognitive psychology. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(3), 174-183. [CrossRef]

- Belkin, M., Hsu, D., Ma, S., & Mandal, S. (2019). Reconciling modern machine-learning practice and the classical bias–variance trade-off. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(32), 15849-15854. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Bengio, S., Hardt, M., Recht, B., & Vinyals, O. (2021). Understanding deep learning (still) requires rethinking generalization. Communications of the ACM, 64(3), 107-115.

- Feldman, V. (2020). Does learning require memorization? A short tale about a long tail. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing, June 22-26, Chicago, IL (pp. 954-959).

- Feldman, V., & Zhang, C. (2020). What neural networks memorize and why: Discovering the long tail via influence estimation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 2881-2891.

- White, J., Goodman, N., & Hawkins, R. (2022). Mixed-effects transformers for hierarchical adaptation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01749.

- Regev, T. I., Ohams, C., Xie, S., Wolf, L., Fedorenko, E., Warstadt, A., ... & Pimentel, T. (2025). The time scale of redundancy between prosody and linguistic context. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.11630.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).