2. Materials and Methods

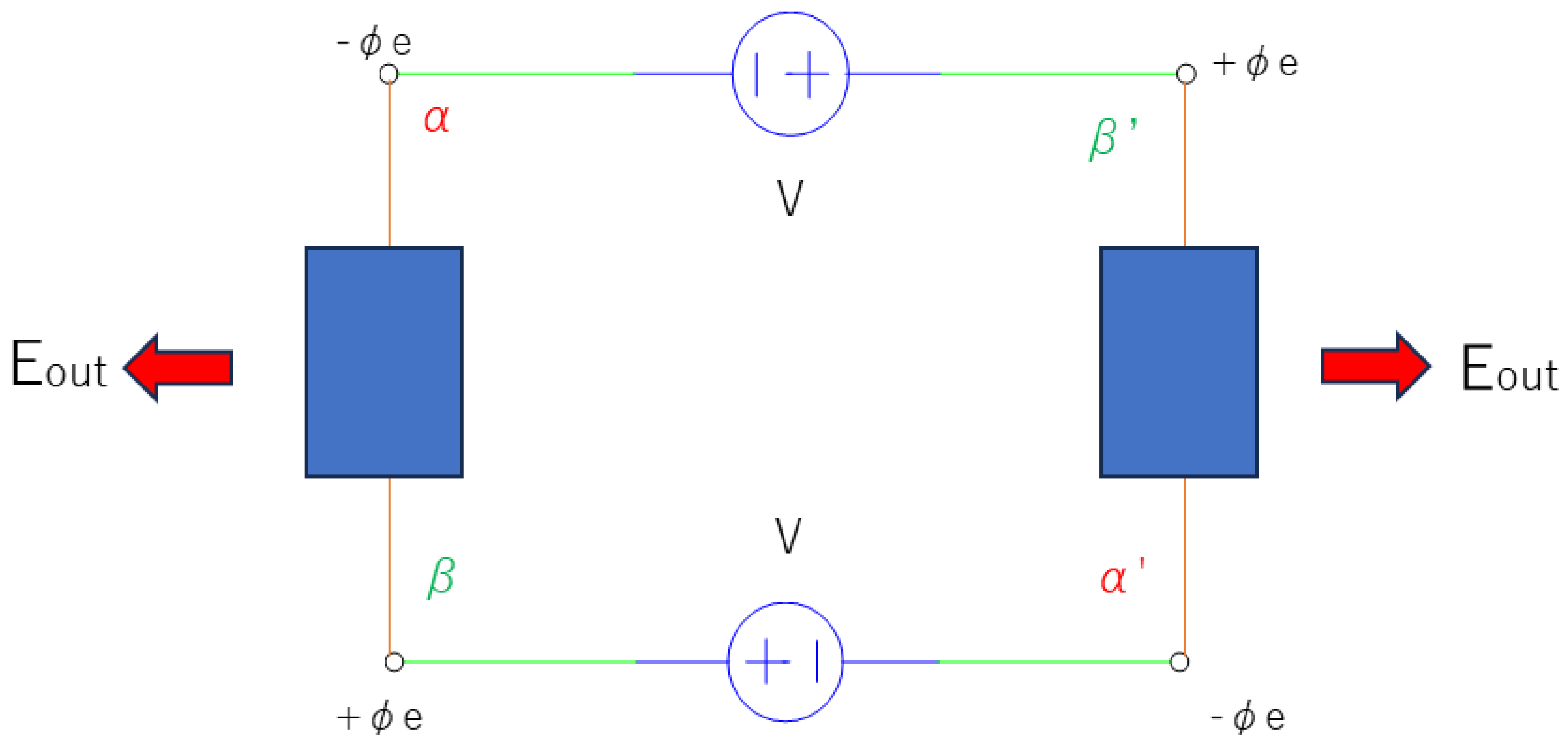

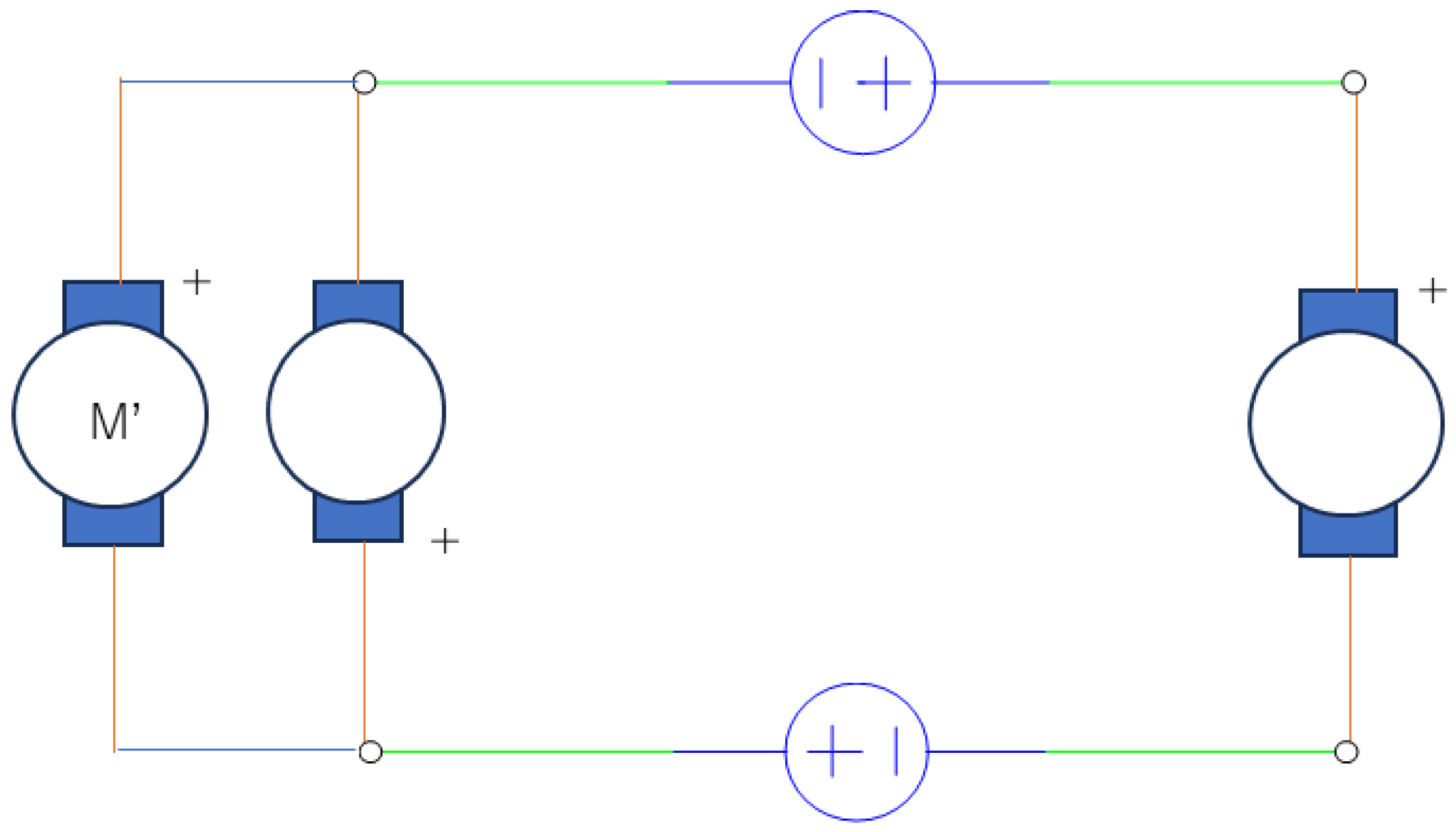

Figure 1 is a schematic of the presented model near its initial state. The circuit employs two same-output voltage sources V and two identical loads which are not pure electrical loads, as they must output an energy of

Eout per electron. As shown in the figure, this circuit system is highly symmetric. The voltage (

V) is expressed in terms of the electric potential (

φe) as follows:

Note that

α,

β,

α’ and

β’ in

Figure 1 are the names of taps.

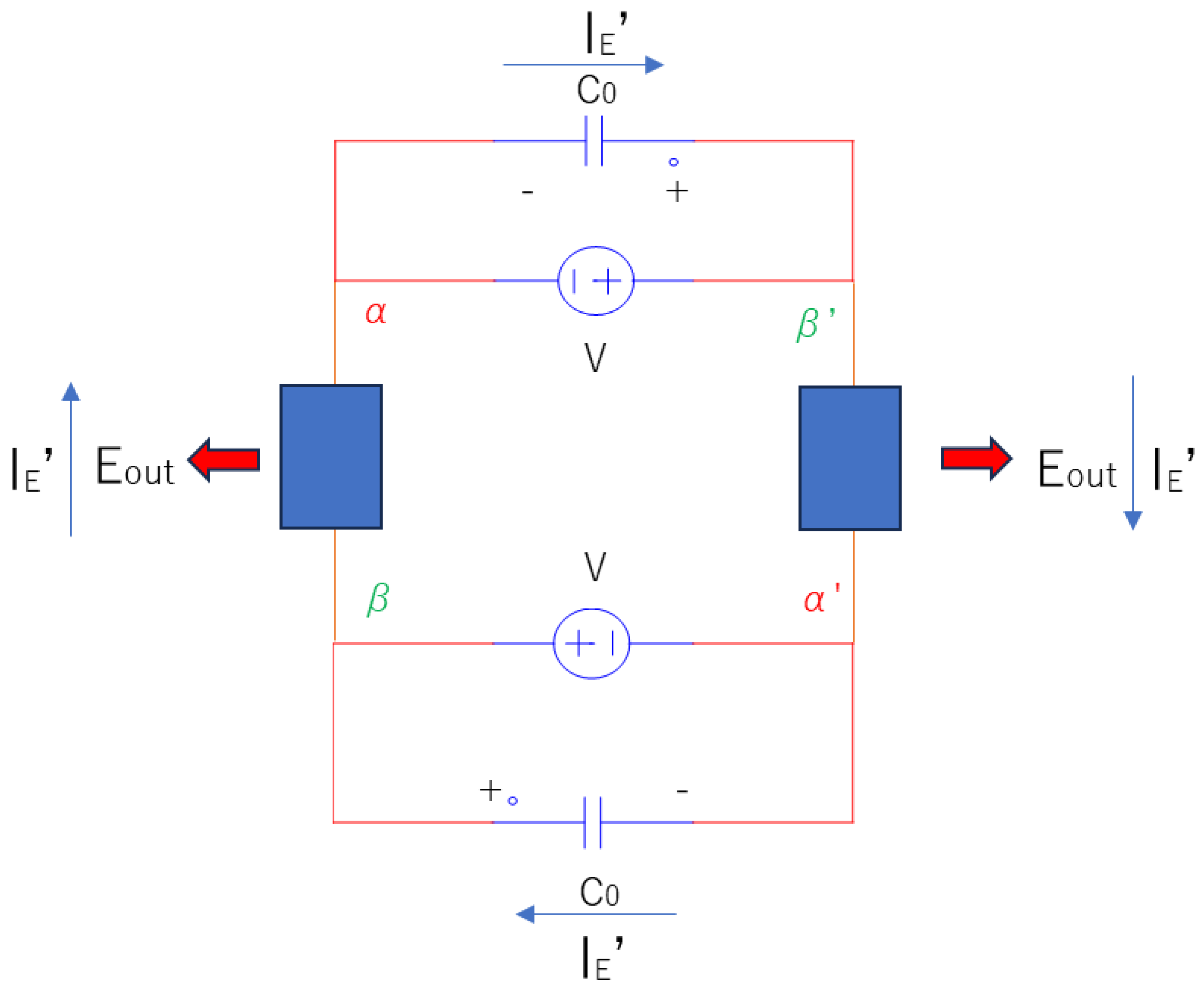

The principle of the model is shown in

Figure 2, which (unlike

Figure 1) includes a pair of stray capacitors C

0 embedded in a vacuum. At initial time

t = 0, the stray condensers C

0 are shorted. (Note that a condenser is generally shorted at the initial state due to its voltage–current characteristic.) Moreover, completely at

t=0, the loads do not output the energies due to no current because the stary condenser C

0 are shorted and thus at

t=0, all the currents in the system are distributed to the stray condenser C

0. At some transition time

t =

tc, which is essentially equal to the time constant (

) (i.e., the product of the capacitance (

C0) and load resistance (

R) of the load), there is a transient current (

i) in the loads and an emergent electric potential (

φ) defined as follows:

where

e is the electron charge.

At time (

tc), considering the above definition of the emergent electric potential (

φ), the following condition must be satisfied:

Note that resistance (

R) is the internal ones of the loads in

Figure 2. The right-hand side of this inequality indirectly defines the energy of the voltage source V, which essentially equals to the Joule heating. Thus, for an electron, we can rewrite the condition (3) as:

where

kB and

T denote the Boltzmann constant and temperature, respectively. Note that both the sides of inequality (4) imply the avarage energy of an electron.The left-side implies a work which an electron receives from the condenser. In most situations, the temperature is the room temperature (i.e.

) but inequality (4) implies that Joule heating is ineffective.

As discussed later, the term equals the kinetic energy.

When the above condition is satisfied, the energies stored in the condensers are discharged, because the energy balance between the condenser C

0 and the voltage source V breaks. Under the energy-conservation law, energy interchange between the paired up-condenser and down-condenser in

Figure 2 induces a constant current (

IE’) along the C

0-load-to-C

0-load loop. Because the condensers C

0 are embedded in a vacuum and cannot be touched, a divergent current (

IE’) is generated. Note that if the inequality is not satisfied, the condensers never discharge their current but if the inequality is satisfied, the voltage sources V momentary operate until the condensers begin discharging at time (

tc) and are dormant thereafter, thereby generating energy.

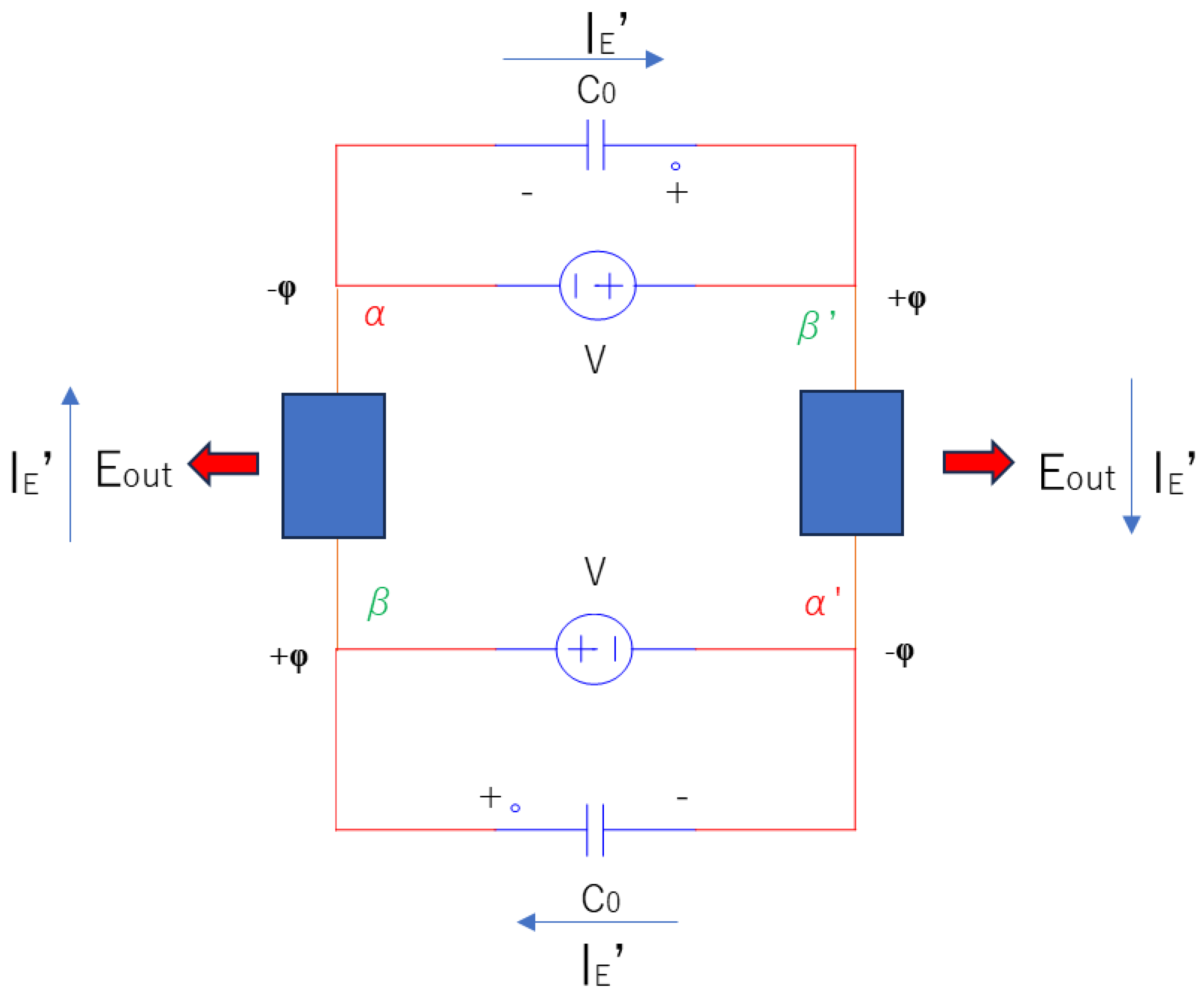

We now discuss the emergent electric potential (φ) after steady-state.

In the vicinity of tap

α or

β at

t =

tc, we have:

and

where

Ee and

Ec0 denote the ohmic and condenser-associated electric fields, respectively.

Note that the vector (ds) aligns along the direction of (IE’).

Given that the condenser discharges the current at this time, we have:

However, in the vicinity of a tap, because

, we have:

giving rise to

This equation implies that the ohmic voltage is ineffective. Tha volatge of the condenser is updated as follows.

In the steady-state where (

Eout) is nonzero, the electric potential becomes:

with

This emergent electric potential (

φ) is demonstrated in

Figure 3. Note that the electric potential (

φ) is not ohmic but a new electric potential of the stray condenser during time

Let us introduce wave function contributing to the electron motion.

The general form of the Hamiltonian is:

where the first and second terms describe the center-of-mass motion and the net electron–electron interaction, respectively. As will be discussed soon, the following assumption holds:

Moerover, as will be described, assuming that the scalar is distributed along x-axis and provides the center-of- mass motion that is equal to the kinetic energy, this scalar results in a relatively large kinetic energy. Thus, the rest momenta along the other dimentions can be neglected. The reason why results in the center-of-mass motion is that it is a constant and does not depend on relative ordinates. Therefore, one-dimension motion is allowed. Then, let us consider reason of the formation of the approxiamtion (14). We can assume a uniform electrical potential (φ) at tap α or β, implying that each electron has approximately the same electrical potential (φ) because whether the potential (φ) is macroscopic or microscopic cannot be discerned. This implies that, as (φ) cannot coexist with a Coulomb interaction potential (φM), the Hamiltonian (Heff) is sufficiently small. Note that the satisfaction of the condition (4) implies no Joule heating and thus we do not need to consider many electrons’ interaction. That is, one-particle picutre is allowed. Moreover, the condition (4) also implies that an electron penetrates lattices. Thus, the electron receives no external forces.

The Hamiltonians at tap

α is:

where

m,

, and

denote the mass of an electron, the Hamiltonian of up-spin electron, and the Hamiltonian of down-spin electron, respectively. Note that, due to the symmetry, the Hamiltonians of tap

α’ is the same forms as those of tap

α, Eq. (15). Moreover, as discussed, each Hamiltonian essentially implies one-particle picture.

The exclusion prenciple claims that the energies of up- and down-spin electrons are the same.

Therefore, we consider degeneracies here.

where

k is the wavenumber.

Thus, the wavefunctions with each spin are

Note that we employed a delta function as the egenfunction of the position.

For the case of tap α

’ we alter the correspondence of the first and second terms of Eq. (15).

Note that (

j) is the imaginary unit. Similarly to tap

α, tap

β satisfies the following Hamiltonians:

From the exclusion principle,

where

The wave functions of

β is:

For the case of tap

β’, we alter the correspondence of the first and second terms of Eq. (20):

In the above equation, the delta functions are substitued.

The first and second terms of the above equation correspond to the left and right sides of the circuit in

Figure 3, respectively. The first and second terms are considered to be related through the Einstein–Podolosky–Rosen correlation [

20].

Here, we consider only the first term of Eq. (27).

The uncertainty relation gives

.

Because the momentum (

p) is constant as (

, the uncertainty

becomes infinite, defying the classical physical motion of an electron from one tap to the other. The wavefunction of the left part of the circuit is:

The probability density (

jE) of the flow:

is solved as:

Herein, we separately consider paired LEDs or paired DC motors as the loads.

DC motor loads

From the normalization condition:

we have

where

λ is the wavelength of an electron.

The wavenumber (

k) is defined as:

The wavenumber is also derived as:

from which the flow probability density (

jE) is obtained as:

To obtain the net current density [A/m

2], we multiply Eq. (37) by the electronic charge (

e):

Here, the area (

Si) is considered as a unit cell; for example,

Importantly, the net observed current

is then derived as:

LED loads

Under the normalization condition:

we again have:

but here we consider the momentum (

kL) of a photon with wavenumber [

21]:

The photon imparts its momentum to an electron and hole and thus the wave number of a carrier becomes a half of Eq. (43), considering the conservation of the momentum.

and

Similarly to the DC motor, the LED loads obtain a net current density of:

As the net current is contributed by an electron and a hole, we have:

Within the area (

Si) of a unit cell, e.g.,

Next, the DC-motor loads must satisfy two conditions. Let us consider these conditions:

The general motion equation of a motor is [

22] as follows:

where

Ra [Ω],

Ia [A],

L [H], and

E [V] denote the inner resistance, working current, inductance, and reverse electromotive force, respectively.

Let us first obtain the general solution from Eq. (50). To obtain this solution, setting the nonhomogeneous term

to zero, the general solution is immediately obtained as:

At completely

t = 0 when all currents flow into the condensers C

0 in our system, the initial current in the motor is zero; that is:

Moreover, the special solution of Eq. (50) is derived by:

Thus, by the substitution to Eq. (50),

and thus the net solution, i.e., the sum of the general solution and the special solution, is:

The transient equation of the motors in our system is then given by:

where

In this equation, the proportionality constant (kE) depends on the magnetic flux, and (Ωm) is the rotational velocity.

The current (Ia) is considered as the constant current under zero load (Ia0).

Under the working condition:

of our system,

importantly, the motor must satisfy:

where

Ωm0 is the speed under zero load.

We now derive the second mandatory condition of the motors. To this end, we discuss the voltages of the motor. At

, because the voltages of the condenser C

0 and voltage source V are canceled, the net voltage

Va = 0. From Eq. (56), we then have:

meaning that (

Ia0) is an induced loop current not induced by the voltage source. Note that, once the current (

Ia0) is formed as the loop current, the voltage (

Ec) is conserved. This fact is related to giving and receiving of energy between paired motors, as will be described.

When the current starts to be discharged by the inductor L of a motor, at

,

where

Vc is the discharging voltage of the inductor L.

As will be discussed soon, the above equation (61) neglects the Joule heating term of Eq. (56). Note that Eq. (60) and Eq. (61) are reverse electromotive forces, not ohmic voltages.

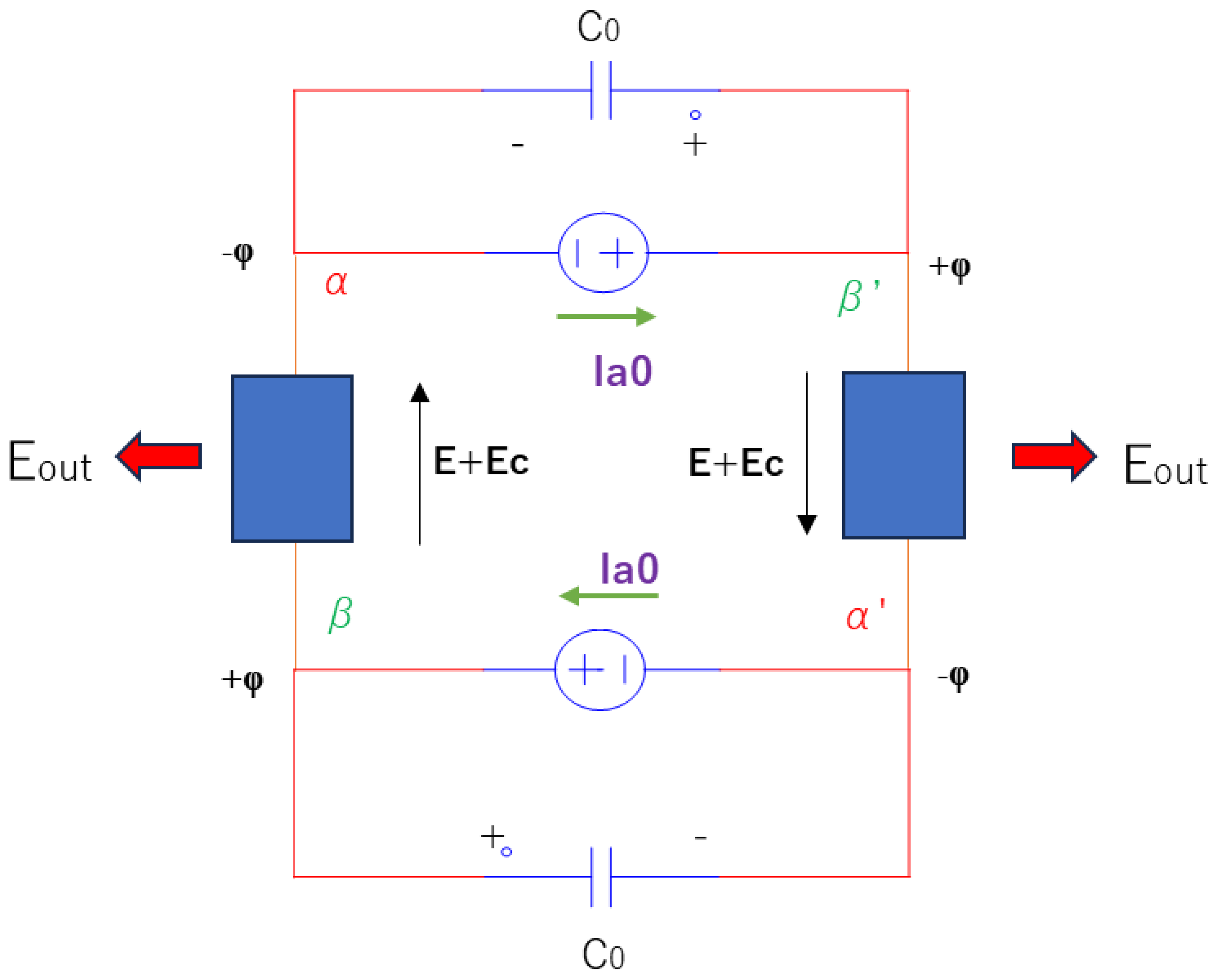

The motor voltage becomes the superposition of (

Ec) and (

E), as shown in

Figure 4. Thus, the net energy of an electron is (i.e., the updated condenser voltage):

To form the above Eq. (62), the motors must satisfy:

where

denotes the impedance input to the other motor during the current discharge, which may include the internal resistance of the voltage source V, and

is the time constant of

that is required for the formation of the loop current (

Ia0). The left-side of Eq. (63) is the coil discharge of the motor, but because the motors are paired in our system, they reciprocally provide and receive energy. Provided that the second condition above is satisfied, the Joule heating term is absent and the motor receives a relatively large input voltage, as discussed in the Results section. Moreover, we will show that because the voltage of a motor is:

implying that the voltage sources V are nonoperational, the loop current (

Ia0) is conserved steadily.

The macroscopic current (

Ia0) can coexist with the microscopic current

in the load but the two currents are not superposed, so an additive current does not appear. Thus, if a current meter is connected in series with a motor, it records either the current (

Ia0) or the current

at each moment, presenting widely fluctuating currents to the experimental observer. Accordingly, we set a detour for the current

in the system with paired DC motors (

Figure 5). In the Results section, we will discuss the importance of:

in the system with DC motor loads. The macroscopic current interferes with the microscopic current , necessitating a detour. As described in the main body, it can be interpreted that the current in the left-side motor alternatively chooses the detour: The emergent electric potential provides a constant current is independent of the resistance Therefore, a large resistance (for example, 1.0 MΩ) allows the current flow. For the same reason, this equation is not an ohmic equation so Joule heating is absent. Note that will be described in the Discussion section.

Here, let us introduce the output electric power (

WR0). The incremental value in the right-side motor in

Figure 5 is

where

Considering the symmetry in

Figure 5, i.e., because the voltage (

) in the right-side motor is eccentially equal to that of the left-side motor

, Eq. (66) must equal to the incremental electric power (

dW) in the left side motor.

Generally, we have, in the resistence and in the left motor of

Figure 5,

where

p is the propotional constant. The reason to introduce this constant will be discussed in the Discussion section. Eqs. (68) and (68-2) imply the current

is common to the left motor and the resistance. Considering Eq. (66),

Given

of the left-side motor, we obtain

Integrating both sides of Eq. (70) gives

where WR0 is the electric power in the resistance (R0), which was defined by .

Provided that the conditions in our system are satisfied, Eq. (71) is not a Joule-heating expression. The absence of Joule heating can be explained by the dead voltage sources, as frequently described in this paper. The voltage sources are only temporarily active in the vicinity of the initial time.

Note that, although the general current was considered and because this current is common to the resistance and the left motor that is, for the symmetry, equal to that of the right-side motor , the derivation that results in Eq. (71) makes us interpret that in the left-side motor chooses the the path of the resistance (R0) instead of the path of the left-side motor. Note that the current cannnot coexist simultaneously in both the left motor and the resistance because of the Kirchhoff’s current law.

3. Results

We first present the results of the paired-LED system with:

or

where

ω is the angular frequency. The divergent current is

Given the approximate wavelength (

λ) of a blue LED:

the angular frequency is calculated as:

The above current and voltage are valid.

The results of the LED system are summarized in the following three figures: a schematic configuration of the circuit, a photograph of the initial experimental setup, and a photograph of the experimental result.

We now present the results of the paired motor system.

Table 1 lists the specifications of the employed DC motor, and

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show a potable tester and the employed paired motors, respectively.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present the three stages of the paired motor experiments: the circuit configurations, the preparations of the experiments, and the experimental results.

Table 2 compares the experimentally observed currents

with the theoretical currents determined as:

where (

E +

Ec)/2 is the emergent electric potential (

φ) with

As the emergent electric potential must not be significantly larger than the input electric potential (

φe), we approximate

as a compromise. As shown,

Table 2 confirms sufficient agreements between the experimental and theoretical values.

Table 3 lists the generated electric power (

WR0) for different input voltages (2

φe)

. Note that, in this table, (

φ) in Eq. (71) is again defined by Eq. (82).The values of

Table 3 are sufficiently large, which are almost equal to those of nuclear power stations. This implies that the values of

Table 3 have provided significant technical merits.

For comfirmation, we validate Eq. (71); that is:

in the paired motor system. The electric power of the LED is obtained simply by replacing coefficient 0.45 [A/V

2] with 0.04 [A/V

2] as:

Assuming

and

we obtain

from which

is calculated as:

On the other hand, the direct electric power

W’LED is defined as simply

Thus

validating the expression of

WLED. Considering that Eq. (83) (i.e., Eq. (71)) differs only in the coefficient (i.e.,

), it is allowed to mention that the above result (91) also validates Eq. (71).

Figure 11 shows the circuit configuration when another motor is employed as the detour. The detour motor operated only when its polarity was reversed from that of the paired motors. In this configuration, the additional motor exchanged energy with the left member of the motor pair. The exchanged energy is:

where

E [V] are exchanged among

[V], because the voltage (

Ec) indirectly implies the loop current (

Ia0) and if the motor M’ included this voltage (

Ec), its current would also be the same loop current (

Ia0). This case would claim that the current through the left menber of the paired motors becomes zero, considering the Kirchhoff’s current law. However, acutal experiments show that the left motor of the paired motors is still rotating. Accordingly, the voltage that makes the motor M’ work is

[V].