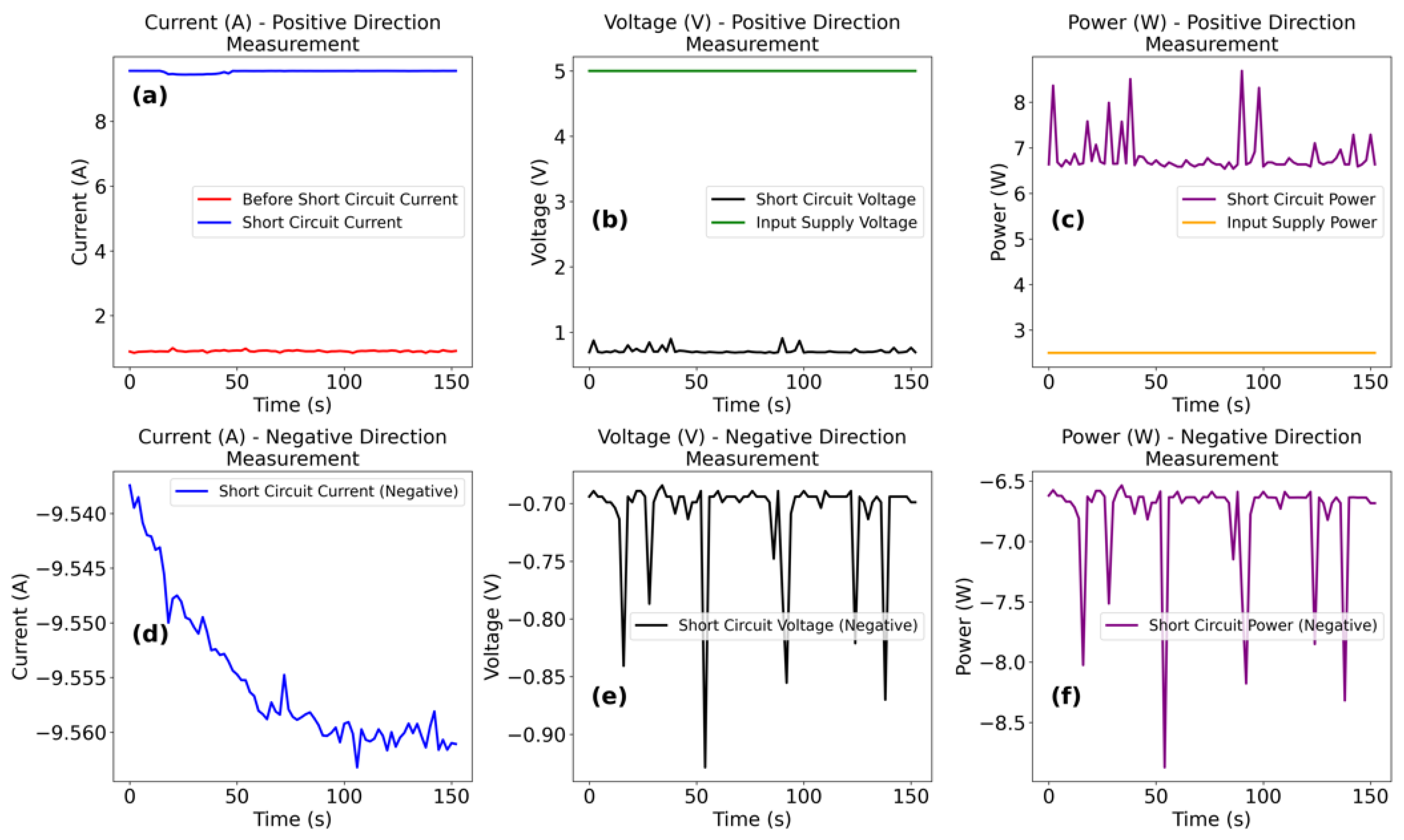

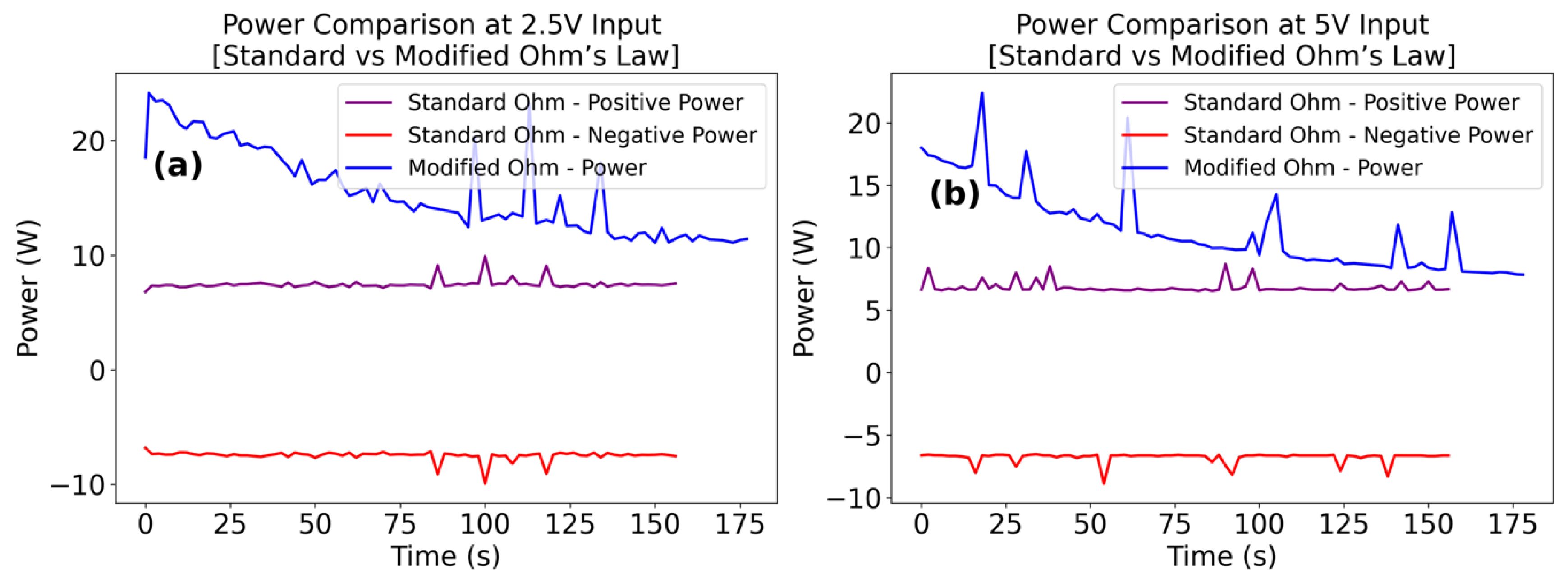

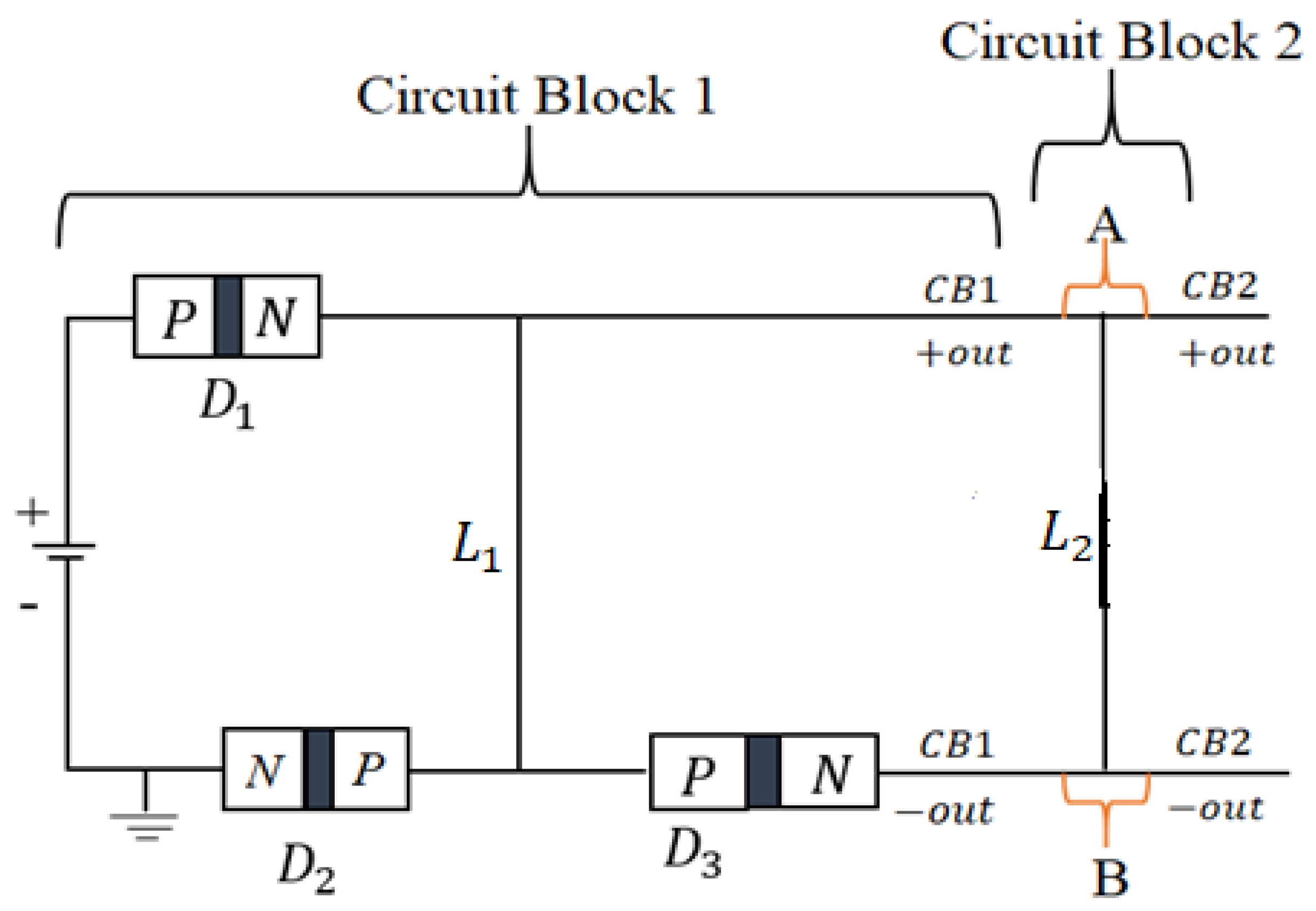

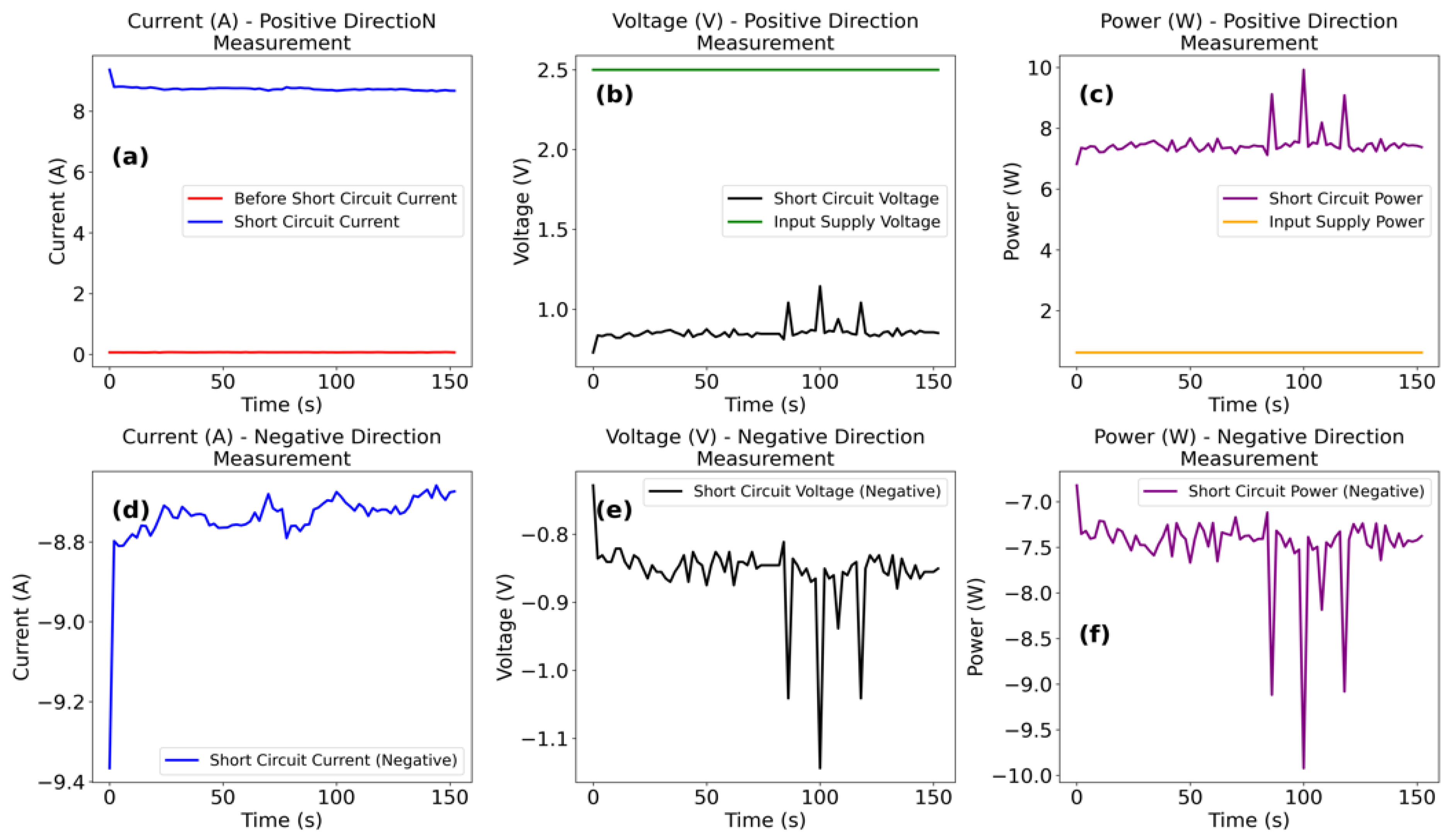

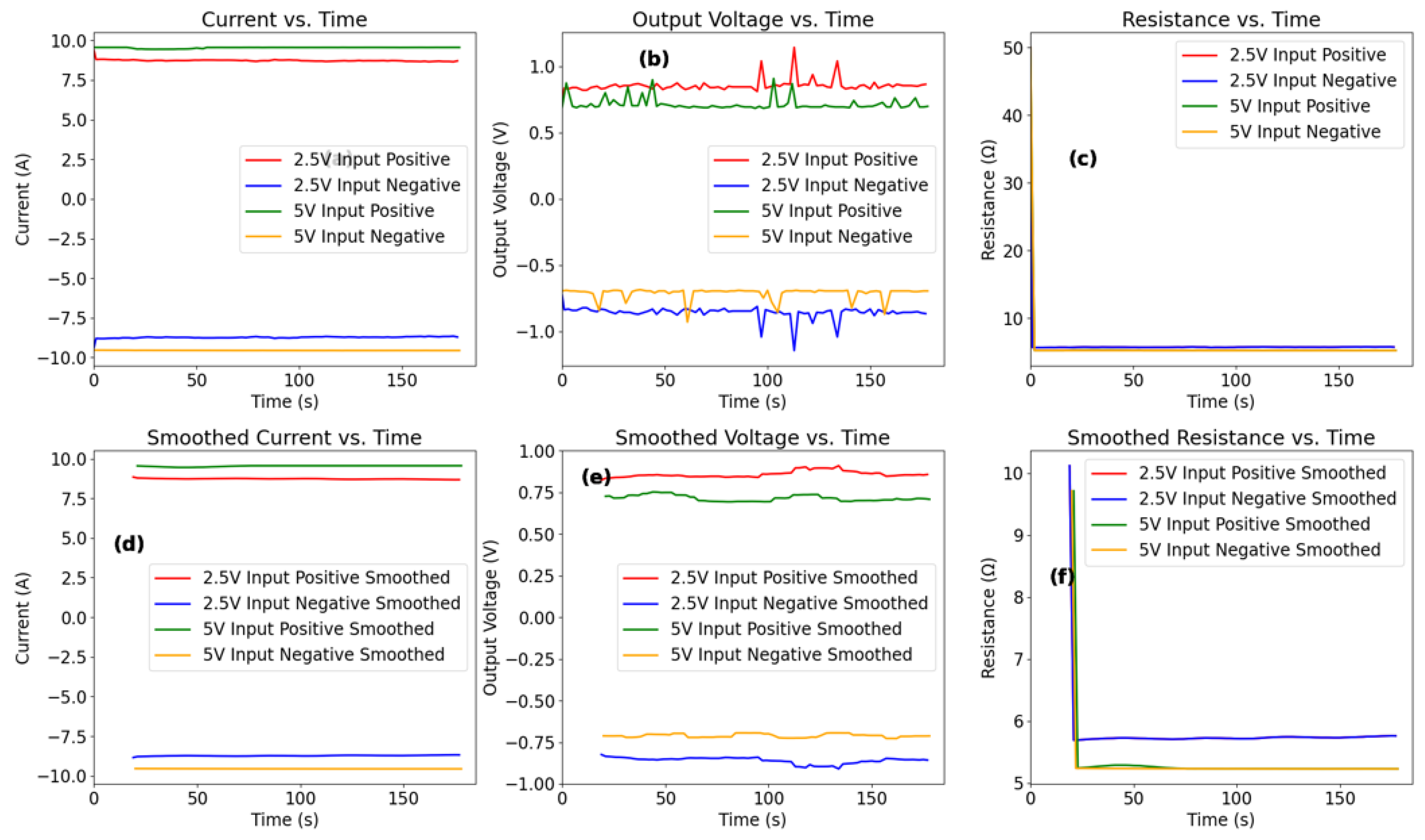

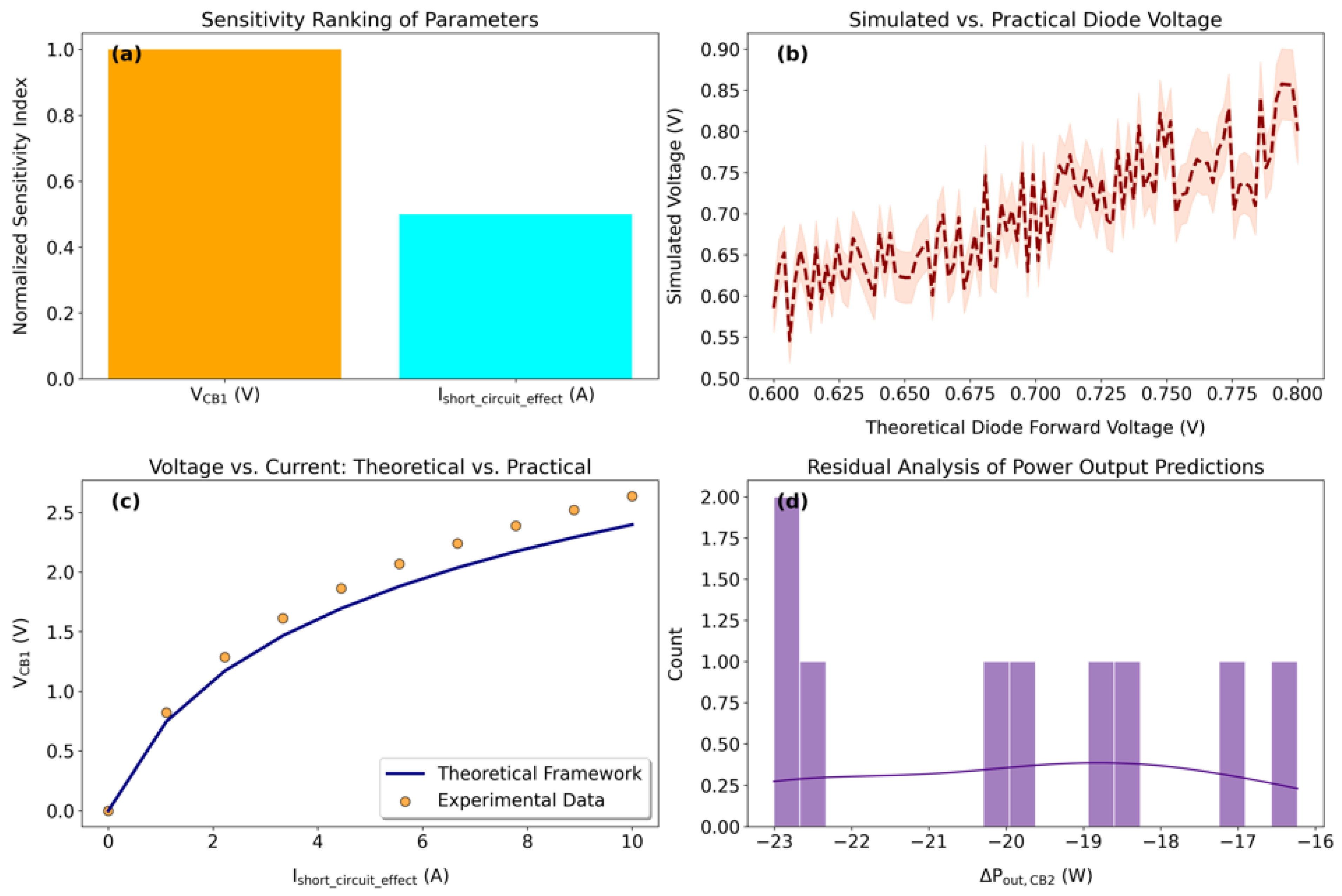

The transition from Ohmic to non-Ohmic states within “Circuit Block 2” fundamentally alters the operational characteristics of “Circuit Block 1”. Experimental results presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4 reveal that the short-circuit voltage and current measurements indicate a significant excess of energy output compared to the initial energy input, specifically for external voltage inputs of

and

. Despite this, conventional electronic and engineering circuit models, which adhere to the Standard Ohm’s Law and typically operate at higher voltages relative to current, cannot reconcile these results. The non-Ohmic properties inherent in the energy-circuit’s components at the terminal of “Circuit Block 2” introduce a discrepancy that must be resolved to align the generated power with standard power systems. This resolution necessitates a transformation of the non-Ohmic sections to produce an Ohmic output. At its core, “Circuit Block 1” exhibits an extraordinary capacity to impede backflow while redirecting and accumulating the excess short-circuit current introduced through (

). Consequently, the inferred excess accumulative power output from “Circuit Block 2” can be harnessed and converted into an Ohmic form, ensuring a relatively stable current. This approach facilitates the achievement of higher power levels through voltage boosting, which becomes imperative due to the substantial voltage drop during the short-circuit phase. Despite the potential of this approach, a critical challenge arises: no known electronic system is capable of directly accommodating relatively low input voltages while simultaneously handling high input currents, similar to the results reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4. In addressing this gap, two possible alternatives emerge, with the second being recommended as an immediate solution for any intended application of the energy circuit for energy generation. One approach involves designing and developing constant current boost converters capable of operating within the unconventional regime of low voltage and high current inputs. This would necessitate the development of oscillators specifically engineered for such a framework, representing a transformative advancement in circuit theory. However, the feasibility of such a development remains contingent upon significant progress within the electronics industry, necessitating rigorous testing and sophisticated analysis that extends beyond the scope of this paper. As a more practical alternative, the recommended approach entails modifying existing standard constant current boost converters. This modification involves introducing an independent low-power source at the short-circuit nodes of “Circuit Block 2”, such as a

input, to elevate the low short-circuit voltage before feeding it into the boost converter. Importantly, as demonstrated in subsequent results, this auxiliary power source does not contribute to the final boosted power output. Rather, its sole function is to ensure the boost converter operates effectively, given that it may require a higher input voltage than the available short-circuit output. To justify this integration and facilitate the transition from non-Ohmic behavior in “Circuit Block 2” to an Ohmic model in “Circuit Block 3”, a robust theoretical foundation is necessarily provided in this section. This foundation elucidates the framework governing the transition from unconventional circuit behavior to regimes constrained by established circuit theory. The observed data in

Table 3 and

Table 4, alongside

Figure 17, derived from the experimental setup in

Figure 12, provide the empirical basis for this analysis. Since the principal objective of this study is to explore conditions under which the law of energy conservation may be broken at macroscopic scales in classical settings, a theoretical framework alone is insufficient. To reinforce these findings, simulated methods are employed beyond “Circuit Block 3” (mirroring the mentioned design of a constant current boost convertor that accepts low input voltages and high input currents) to demonstrate the extension of unconventional results into conventional systems. This section, therefore, not only establishes a theoretical basis but also provides a practical pathway for the broader application of the energy circuit in real-world scenarios.

4.3.1. Combining Independent DC Voltage Sources (Analysis and Implications)

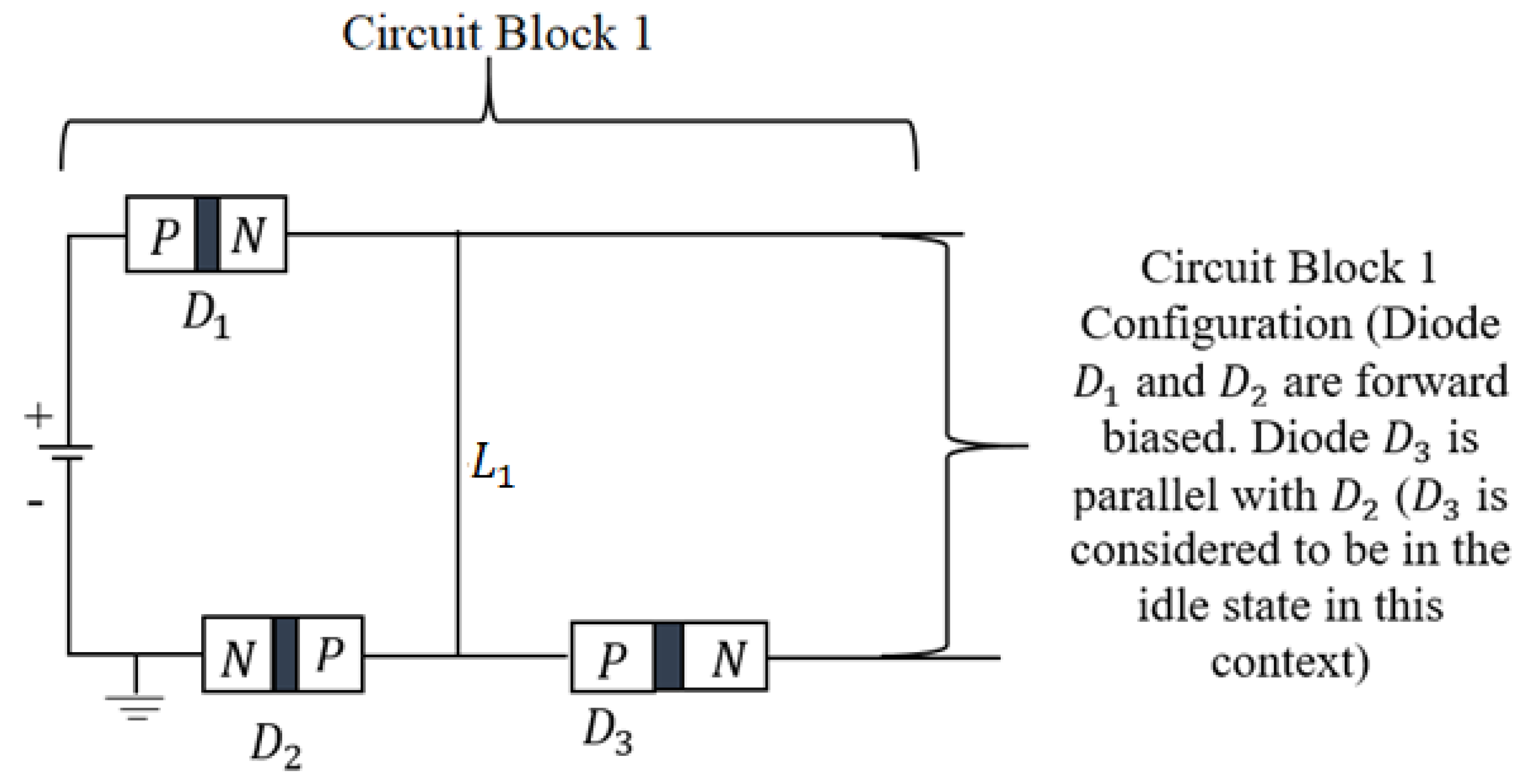

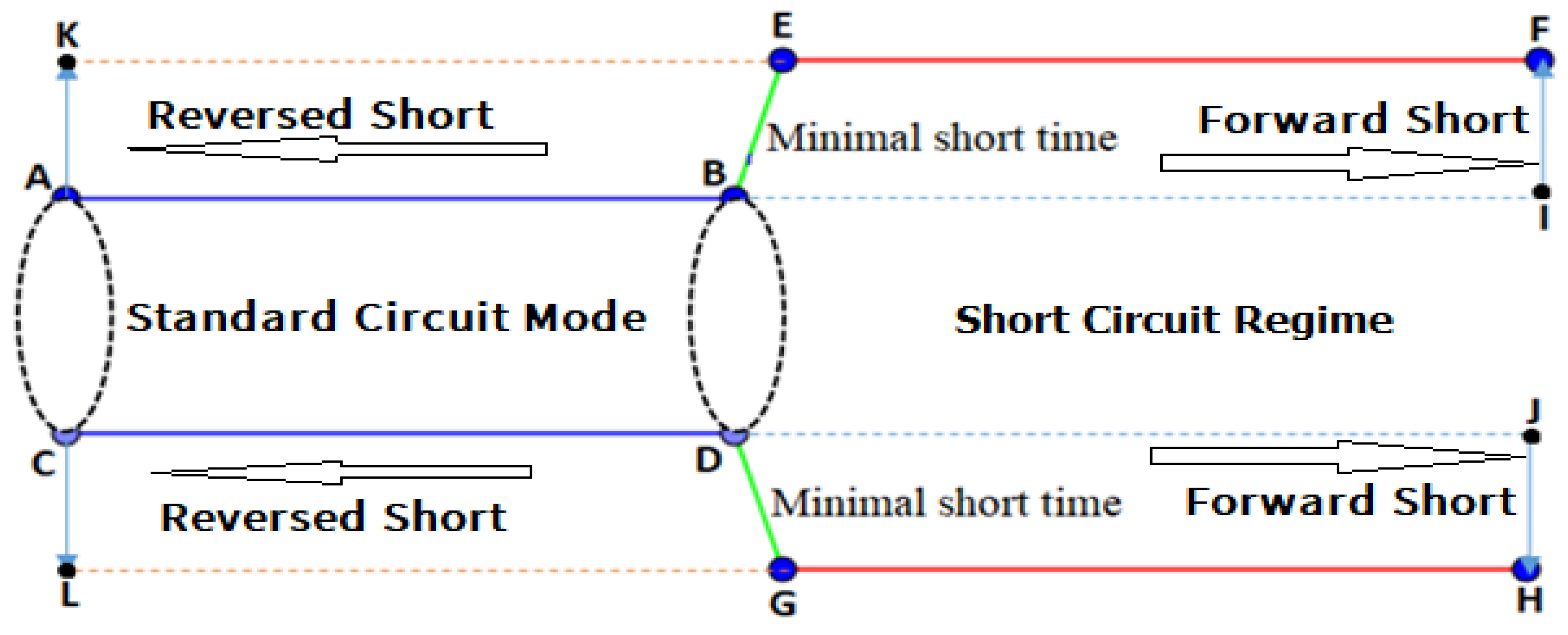

This section presents the first experimental and theoretical framework for combining two independent DC voltage sources at a common node without shared grounding, a configuration that fundamentally violates conventional circuit theory. Unlike traditional systems constrained by Kirchhoff’s voltage and current laws, this architecture challenges the foundational assumption that voltage sources require a mutual reference ground to operate synergistically.

4.3.1.1. Theoretical Considerations of Combining DC Voltage Sources

This section shows that when two independent DC voltage sources -such as a

supply

and approximately, a

source

(based on the “Circuit Block 2” output measurements provided in

Table 4 and

Figure 16) -are galvanically isolated (i.e., not referenced to the same ground), their circuit topology must conform to fundamental circuit laws. Direct connection without isolation challenges Kirchhoff’s laws and conventional circuit principles. The short-circuit analysis results provide a framework where traditional circuit constraints are both violated and redefined at the interface between conventional and unconventional energy systems.

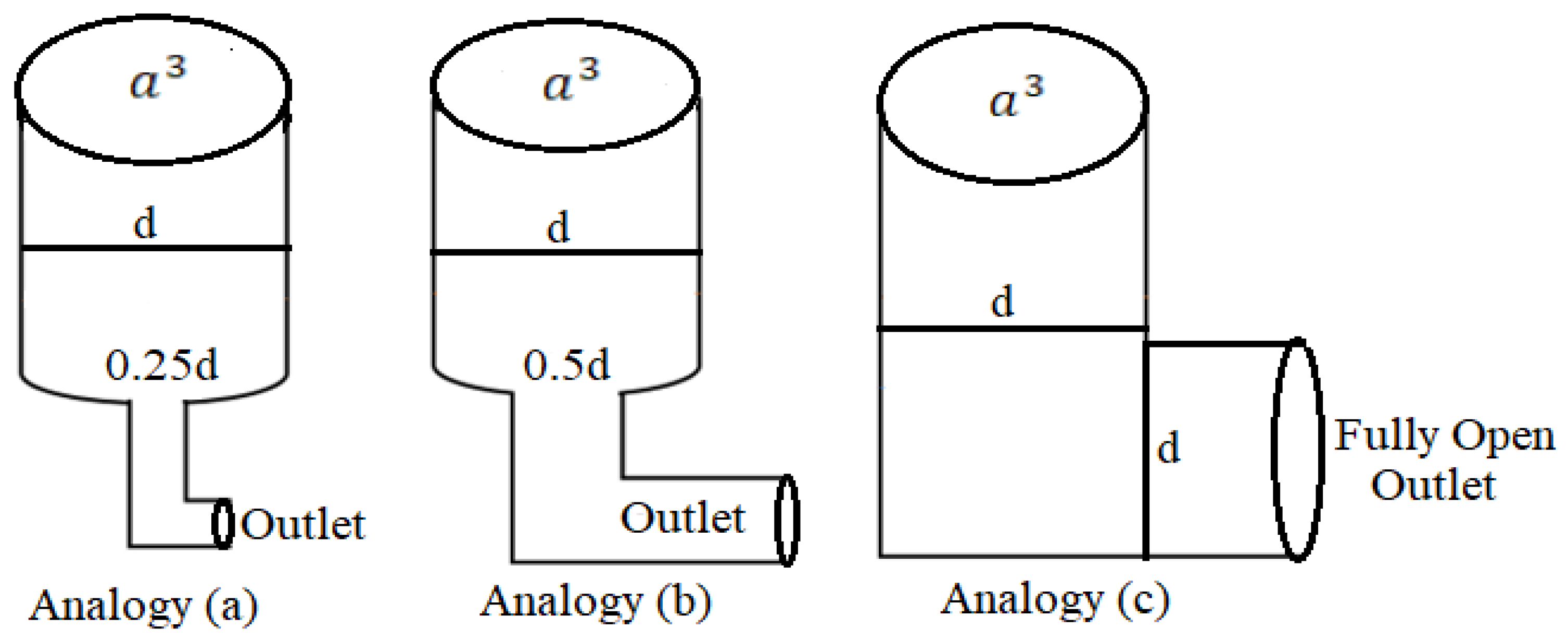

Kirchhoff's Voltage Law (KVL) Constraints. Kirchhoff's Voltage Law (KVL) mandates that the sum of voltages around any closed loop is zero: . If we set and for two distinct sources that are directly connected at a common node (e.g., linking their positive terminals), KVL is violated because the node cannot simultaneously maintain both potentials. This results in an undefined node potential or theoretically infinite circulating current between the sources. Conventionally, the node voltage follows: , a contradiction in this case. However, introducing a low-power constant current boost converter (say DC-DC) modifies this expectation. The new component operates at a slightly higher voltage than the short-circuit output from “Circuit Block 2”, ensuring that short-circuit currents remain bounded.

Kirchhoff's Current Law (KCL) and Current Distribution. Kirchhoff's Current Law (KCL) states that the sum of currents entering a node equals the sum leaving: At the shared node, currents from both sources ( corresponding to () and corresponding to ()) flow into the load. However, the voltage disparity also drives an internal circulating current () between the sources. Using the Standard Ohm's Law: , where is the total internal resistance of the sources. For low-impedance supplies (e.g., each), this current becomes: Ordinarily, such current could damage the lower voltage source through reverse power dissipation. However, the protection mechanism in “Circuit Block 1” prevents backflow, ensuring that no currents circulate undesirably.

Series Configuration (Voltage Summation). Connecting the and sources in series (positive terminal of one to negative terminal of the other) yields additive voltages: The load current is determined by the total voltage and load resistance : Both sources share the same current, making this configuration viable if the source can tolerate . The “short-parallel connection” within “Circuit Block 1” enforces unidirectional short-circuit current flow, ensuring viability in series arrangements. Notably, the short-circuit current from “Circuit Block 2” is significantly higher than the current required to activate the boost converter, ensuring stability.

Parallel Configuration (Circulating Currents and Node Voltage). For non-ideal sources with internal resistances and , the parallel connection results in a weighted node voltage: Assuming , the node voltage becomes: The circulating current is then computed as: In conventional systems, this circulating current risks overheating the lower-voltage source. However, “Circuit Block 1” introduces critical nonlinearity through its uncommon parallel diode configuration. This design sustains low-resistance pathways while blocking reverse currents, thereby eliminating thermal runaway risks. The diodes act as a resistive protection mechanism, ensuring stability without compromising performance.

Diode-OR Isolation for Reverse Current Mitigation. The short-circuit source of is already protected by the diode configuration in “Circuit Block 1”. This section focuses on applying a diode-OR circuit to the introduced low-power source, ensuring proper activation of the constant current boost converter. In a traditional diode-OR circuit, diodes and isolate the sources. Here, the source is routed through diode , while diode provides a protection mechanism for the source established in “Circuit Block 1”. The output voltage is given by: where (for 1N5408 power diodes). For and we have: . With this configuration, the source remains inactive unless the supply fails. This setup prevents reverse currents but does not allow voltage summation. Consequently, the intended goal is achieved -powering the constant current boost converter circuit, introduced in the next section as “Circuit Block 3”.

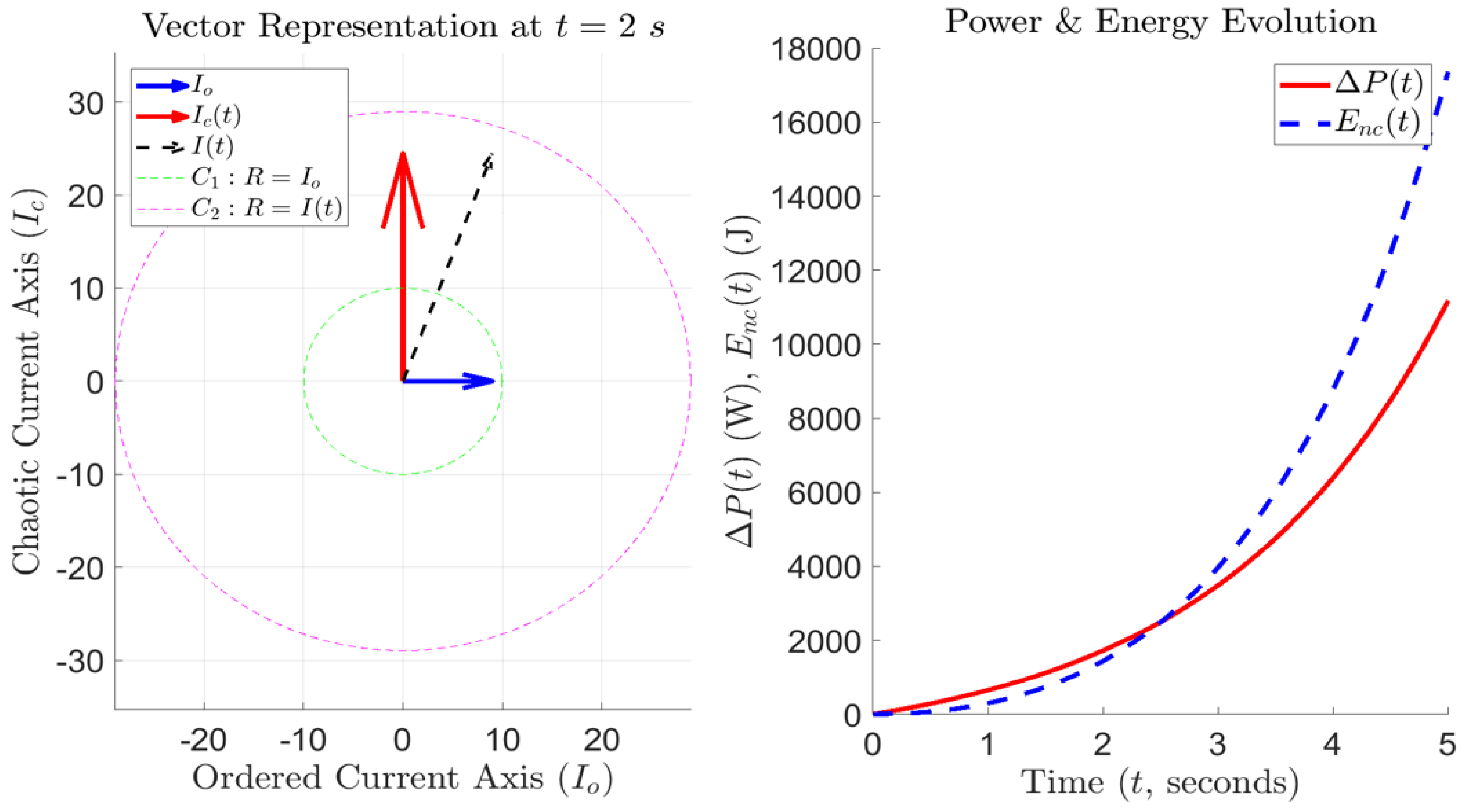

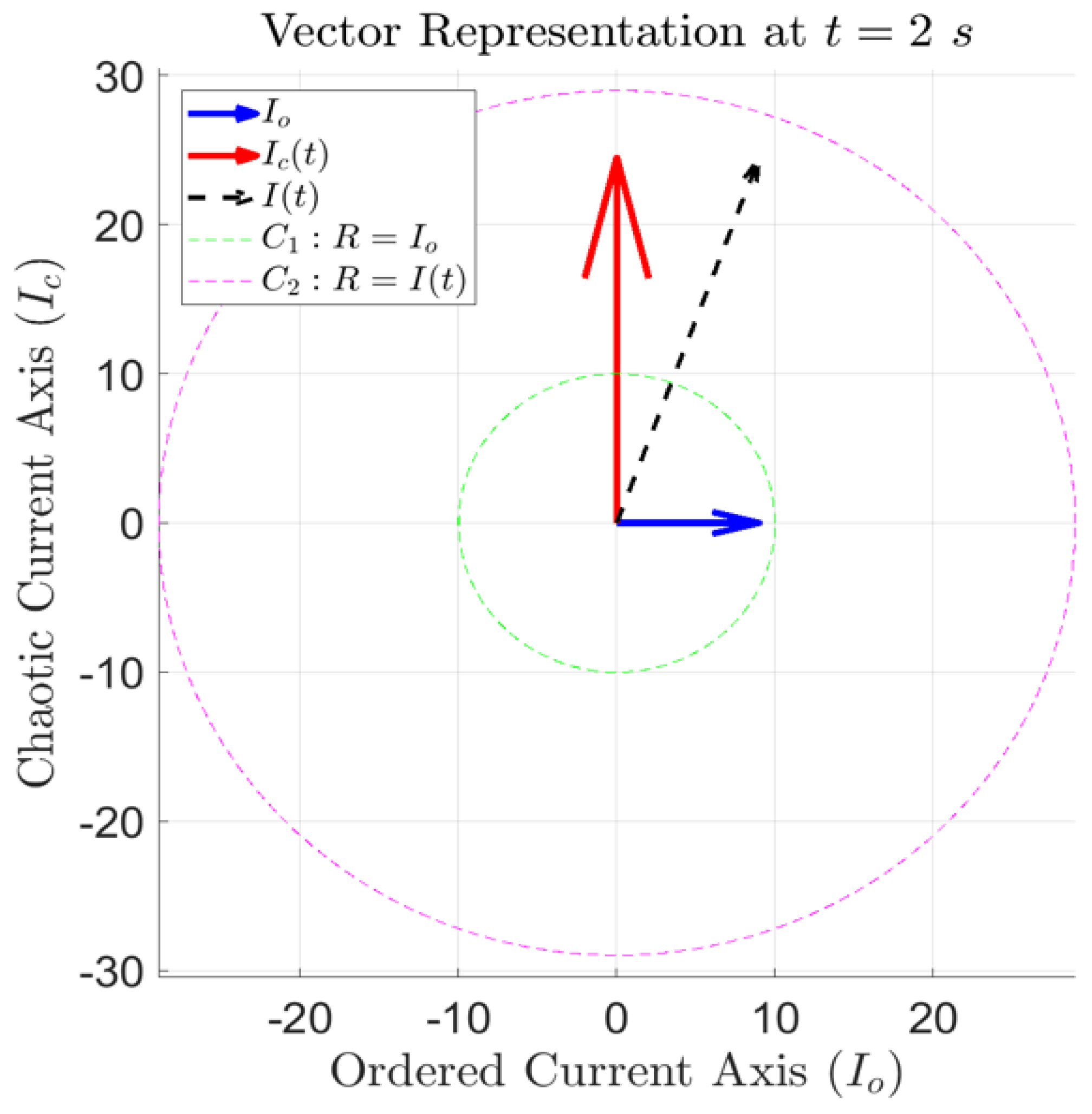

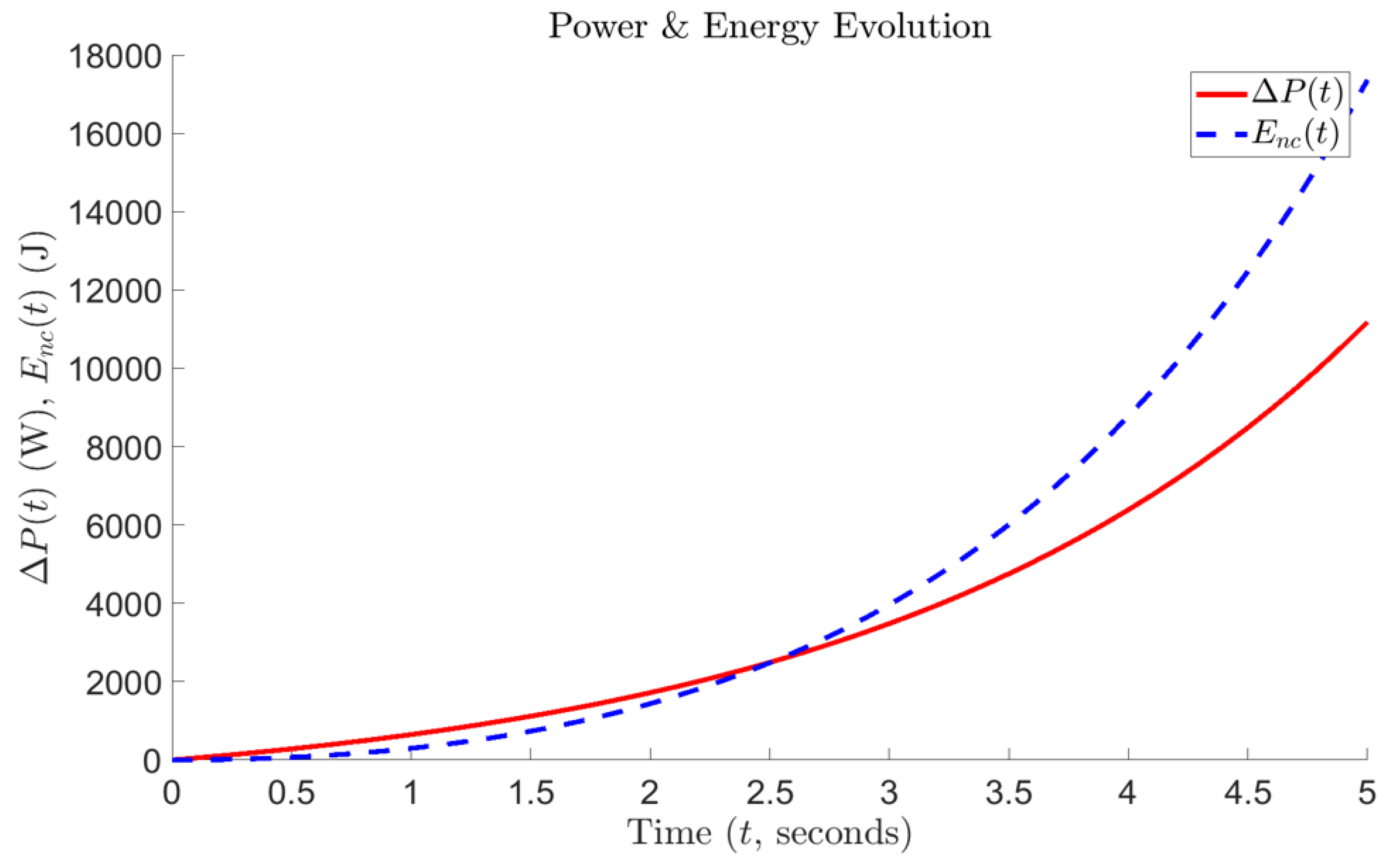

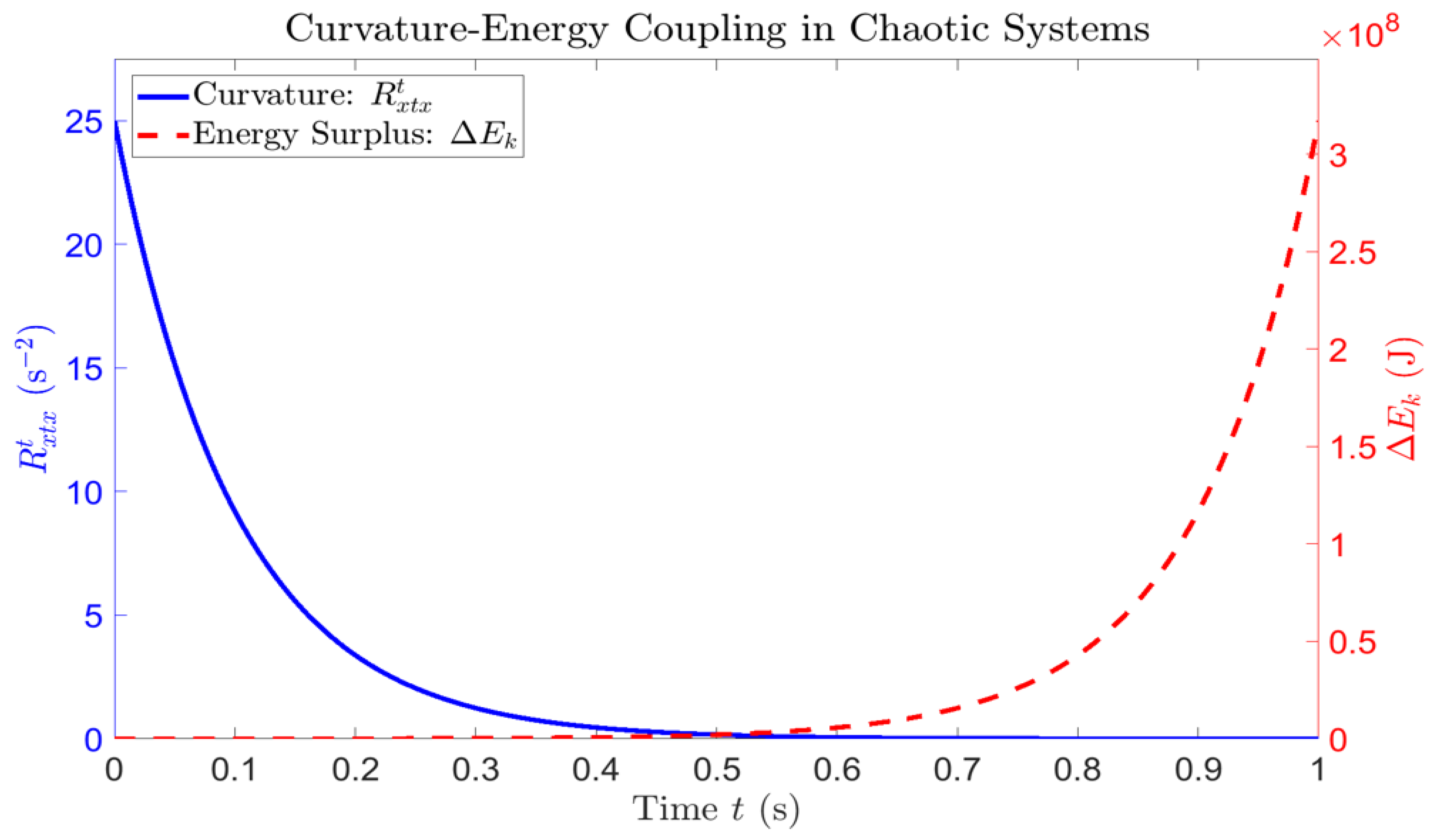

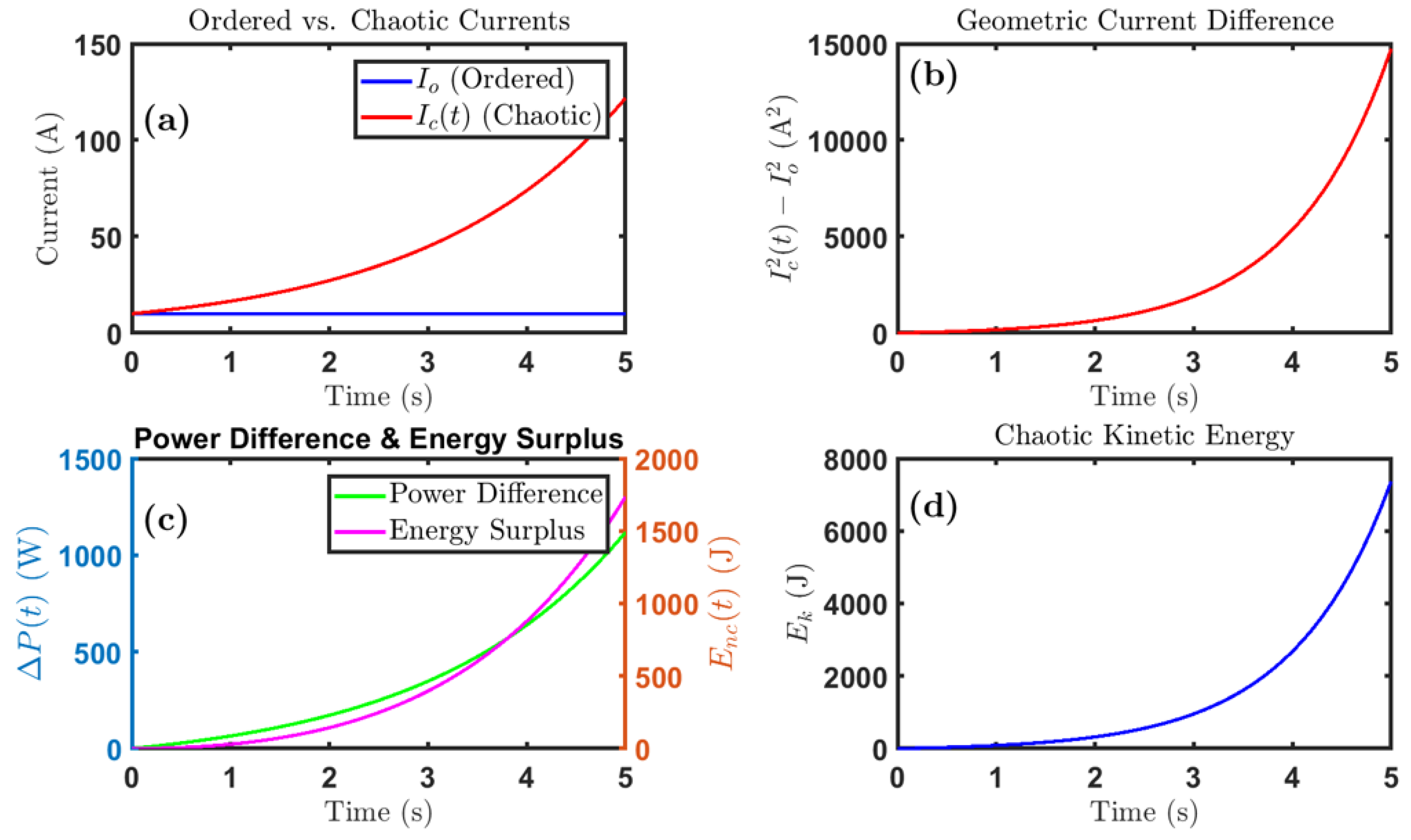

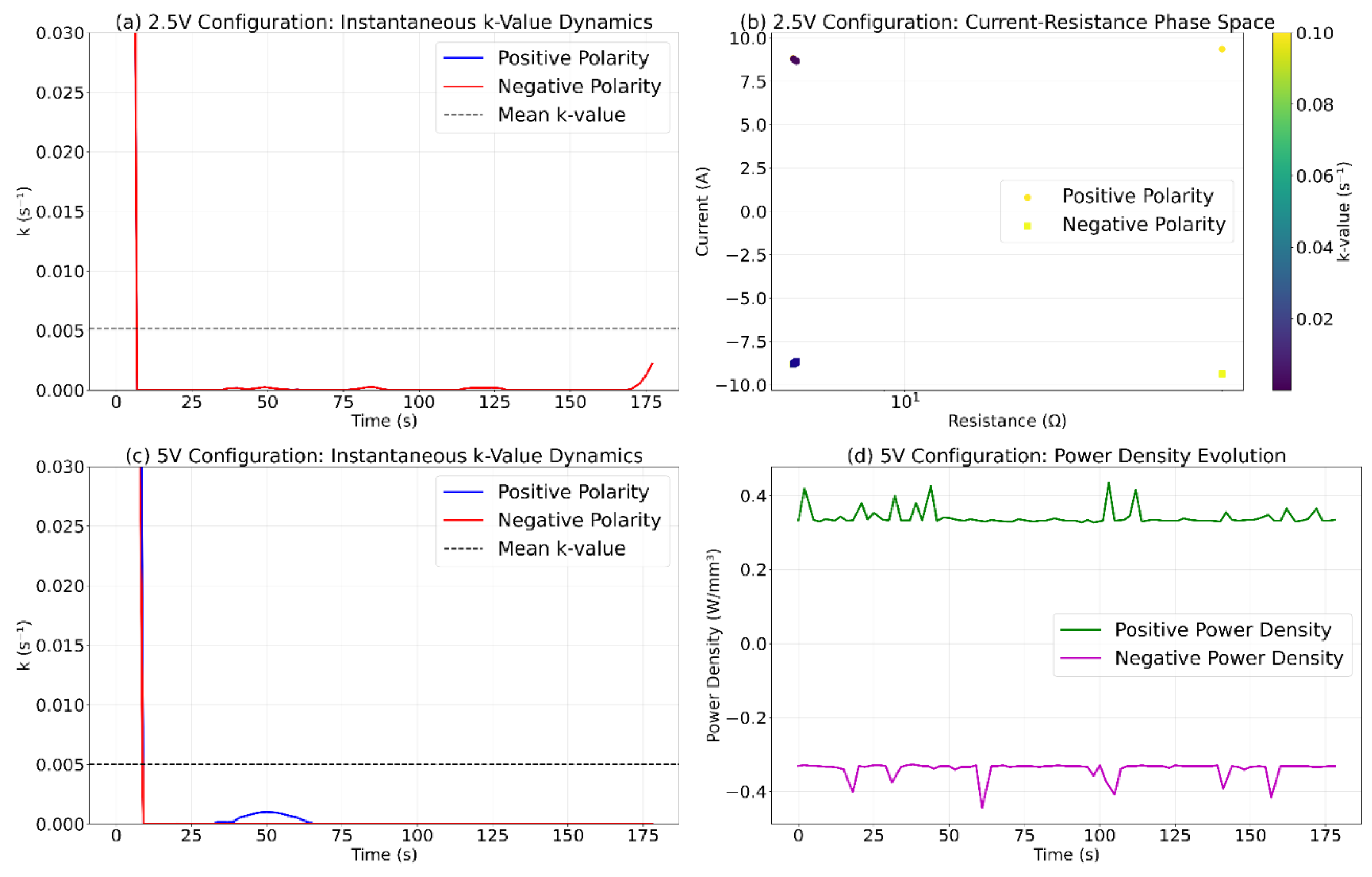

Current Distribution in Non-Ideal Parallel Circuits. In parallel circuit configurations, the currents from each source are given by: and . For : and . Conventionally, the negative signifies reverse current flow into the source -a condition that risks component degradation through Joule heating in linear systems. However, “Circuit Block 1” introduces nonlinear impedance characteristics, dynamically modulating the low-resistance pathway to suppress reverse currents while maintaining forward conduction. This is achieved through synchronized diode biasing, which enforces unidirectional current flow into “Circuit Block 3,” effectively rectifying to a positive value () despite the voltage differential. The observed deviation from classical circuit theory emerges from the system’s inherent chaotic dynamics, as quantified by the Modified Ohm’s Law (Equation 1), which redefines nodal behavior under time-dependent resistance conditions. Backflow is eliminated, and energy is redistributed through geometric manifolds (Equation 36 and Equation 37), allowing the architecture to convert unconventional short-circuit outputs (“Circuit Block 2”) into stabilized, Ohmic-compatible currents (“Circuit Block 3”). This transformation supports the hypothesis that chaotic energy terms () dominate in non-autonomous systems, enabling controlled energy amplification.

Remark 8 (Simulation-Driven Design Rationale). Although experimental validation of multi-source integration is still underway, the simulated framework offers critical insights into low-voltage activation thresholds and current stabilization mechanisms essential for practical constant current boost converter design. This approach eliminates the prohibitive complexity of iterative hardware recalibration in “Circuit Block 3”, demonstrating that a unified converter architecture -capable of dynamically adjusting to multiple output voltages through parametric tuning -delivers superior scalability compared to fixed-output configurations. Serving as a bridge between theoretical innovation and engineering pragmatism, the computational model prioritizes system adaptability over custom circuit modifications for each voltage regime.

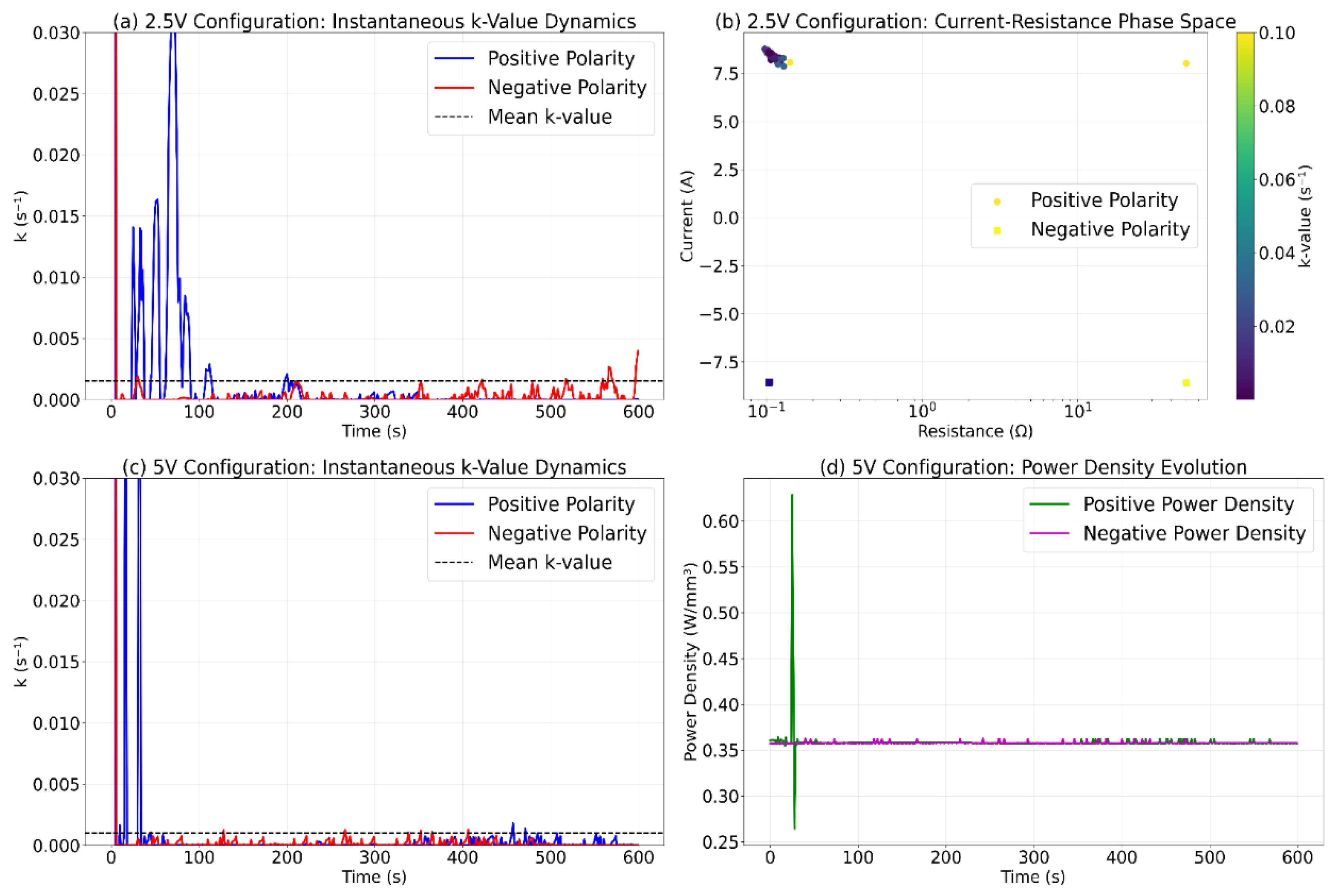

4.3.1.2 Description of the Simulation Framework

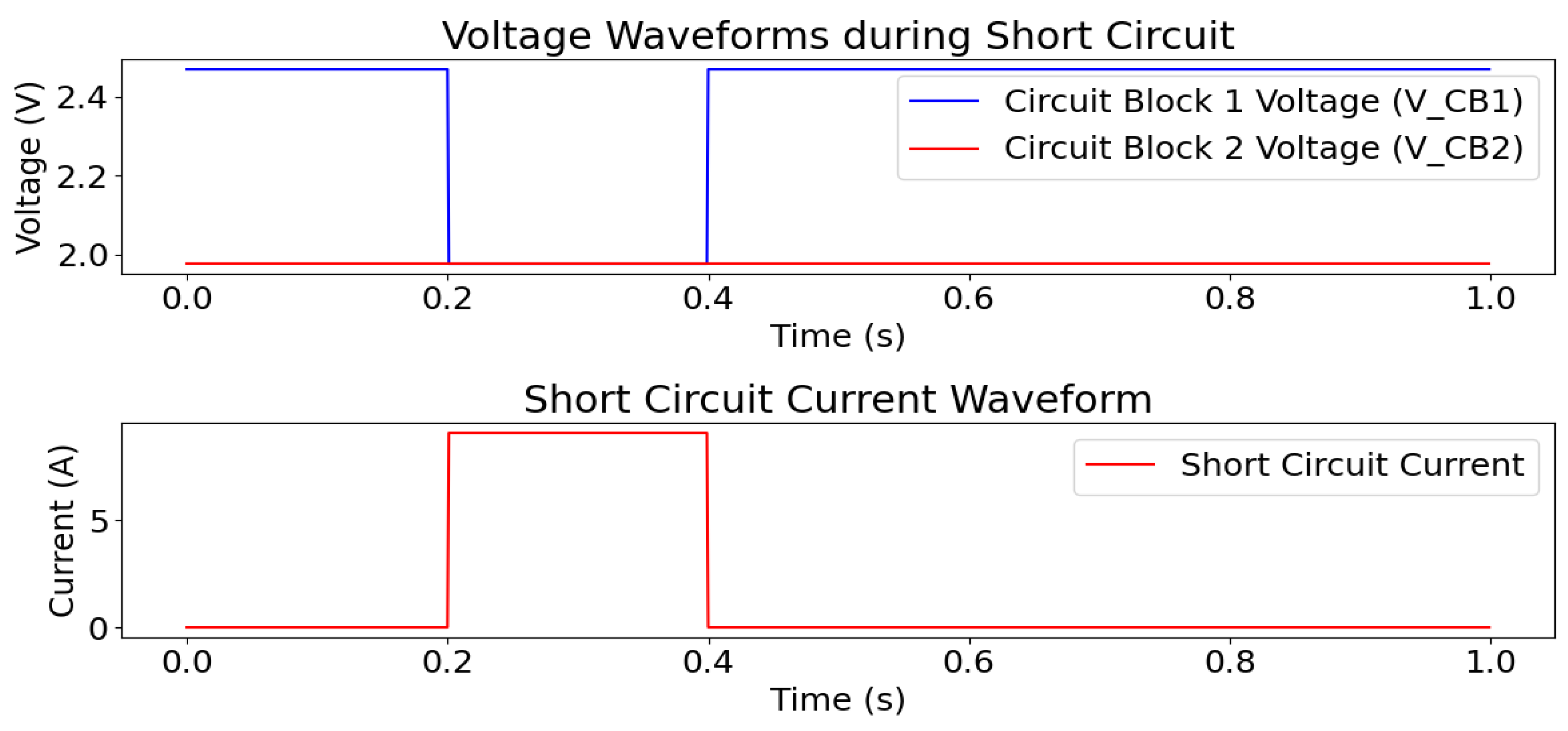

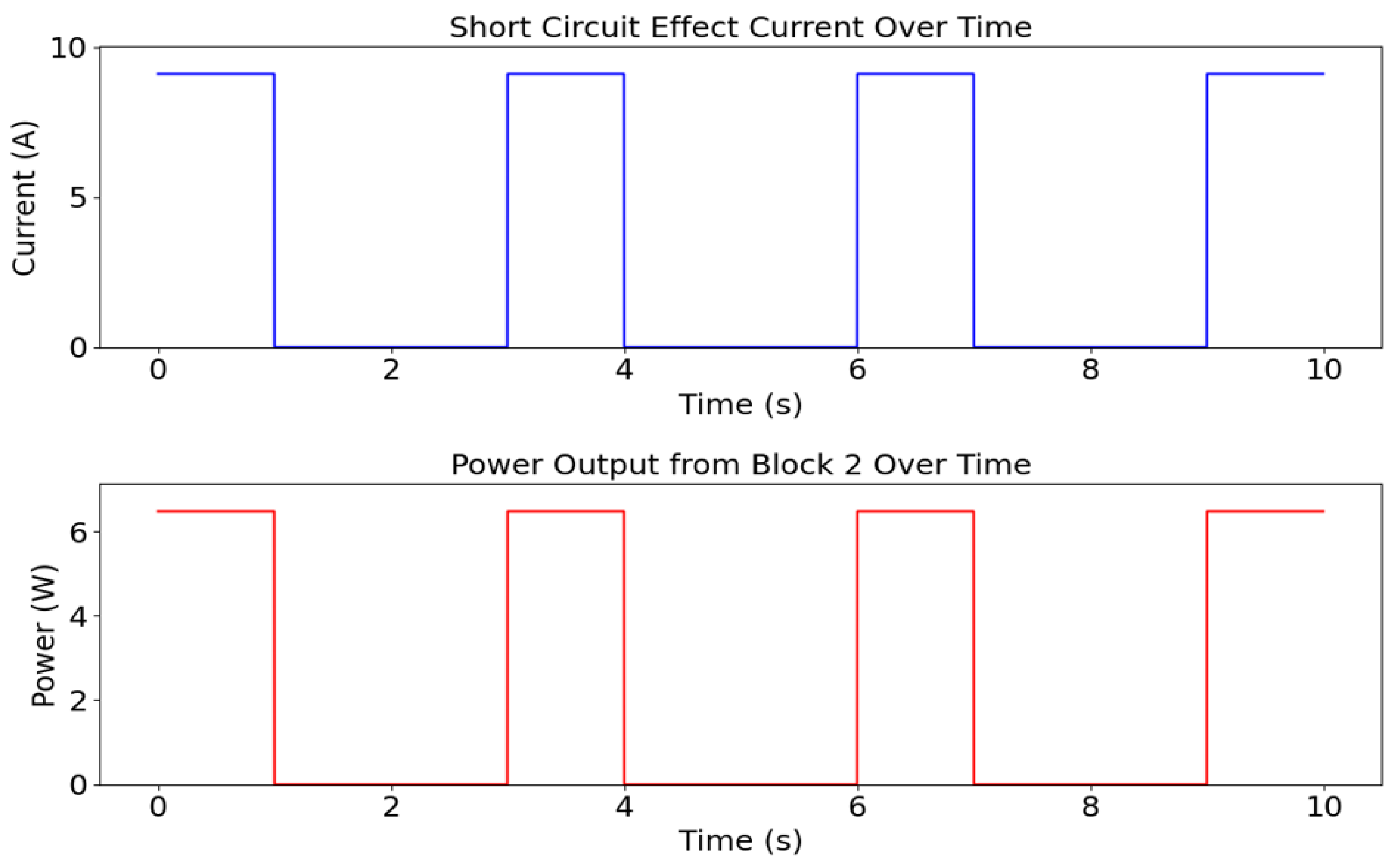

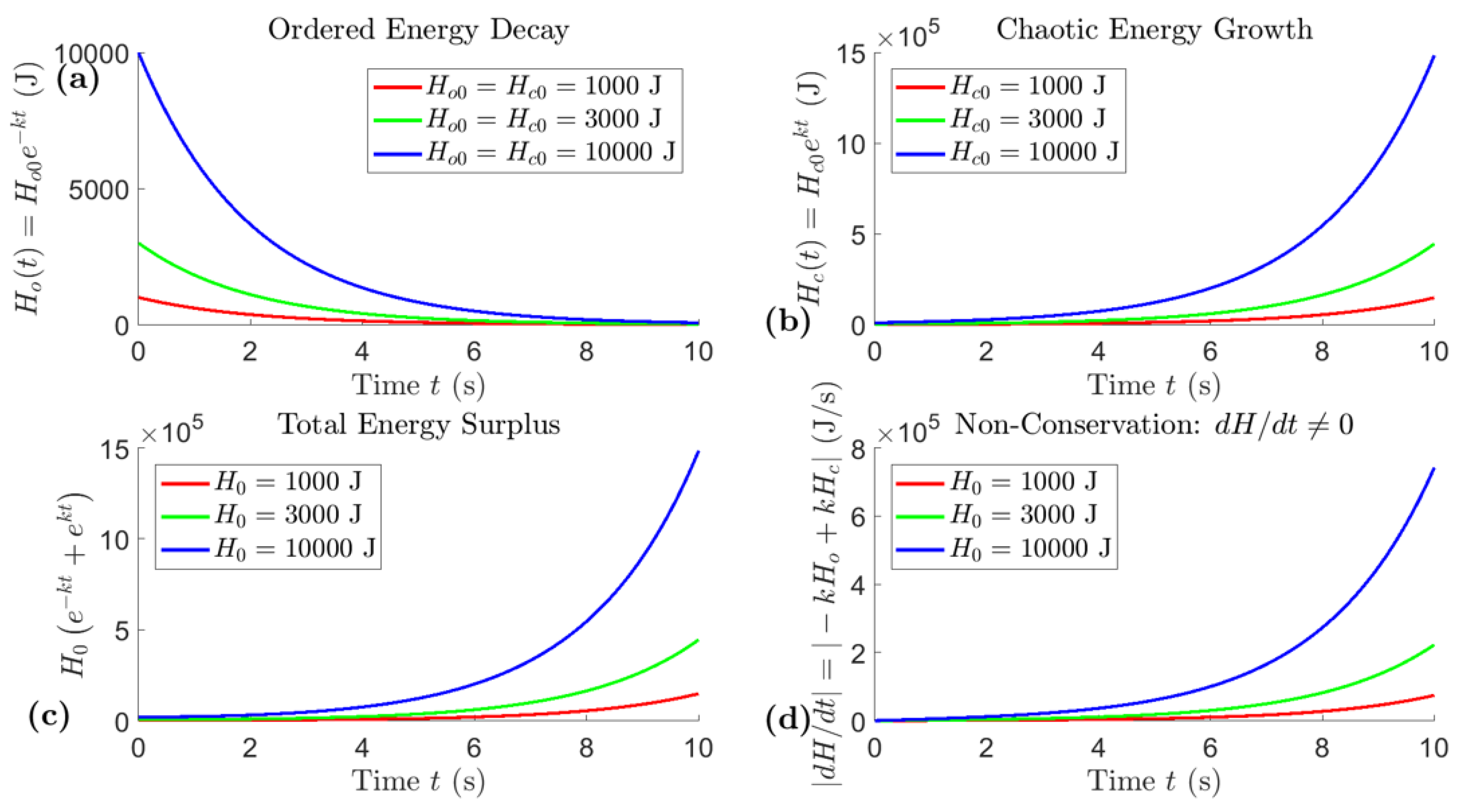

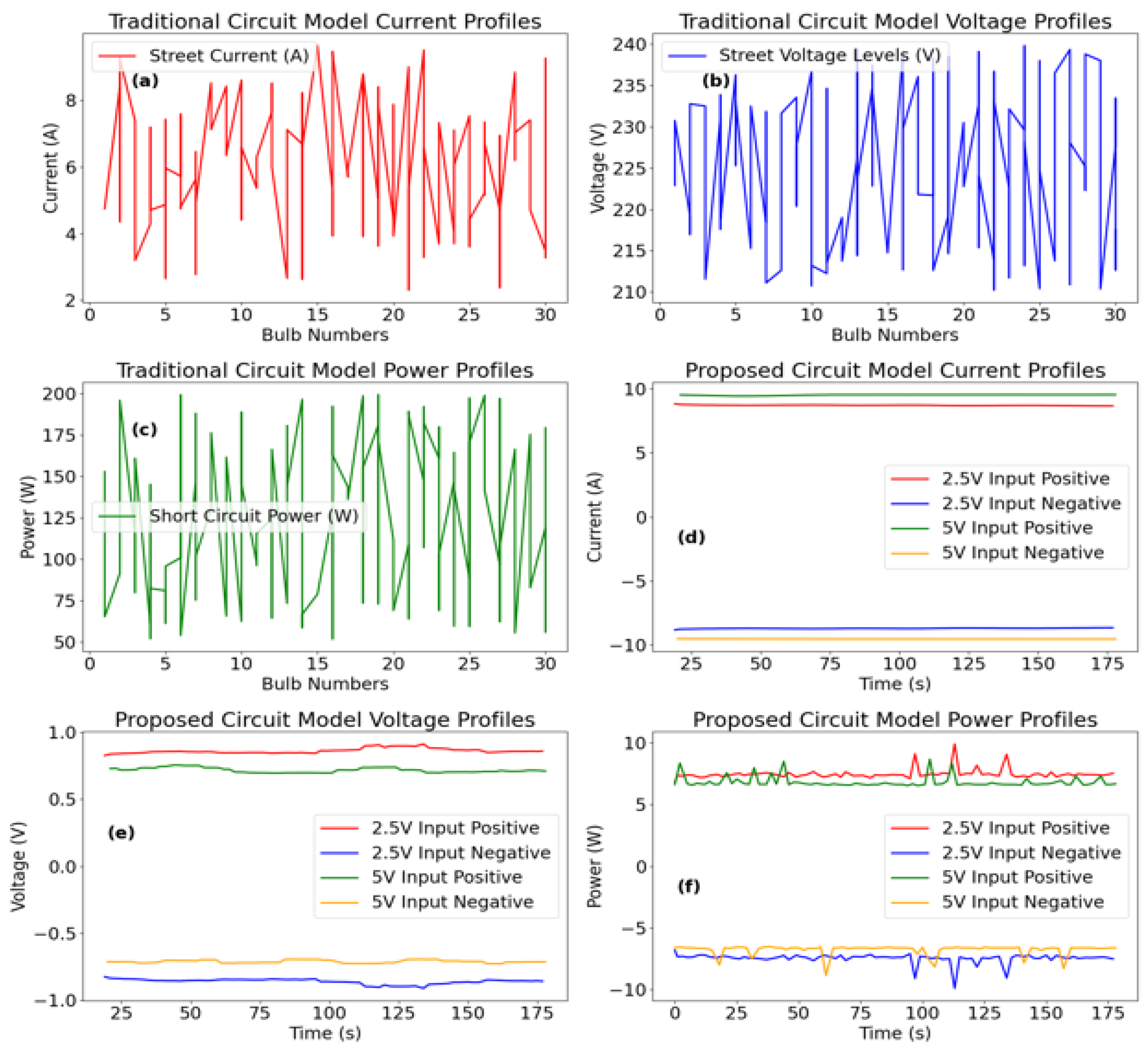

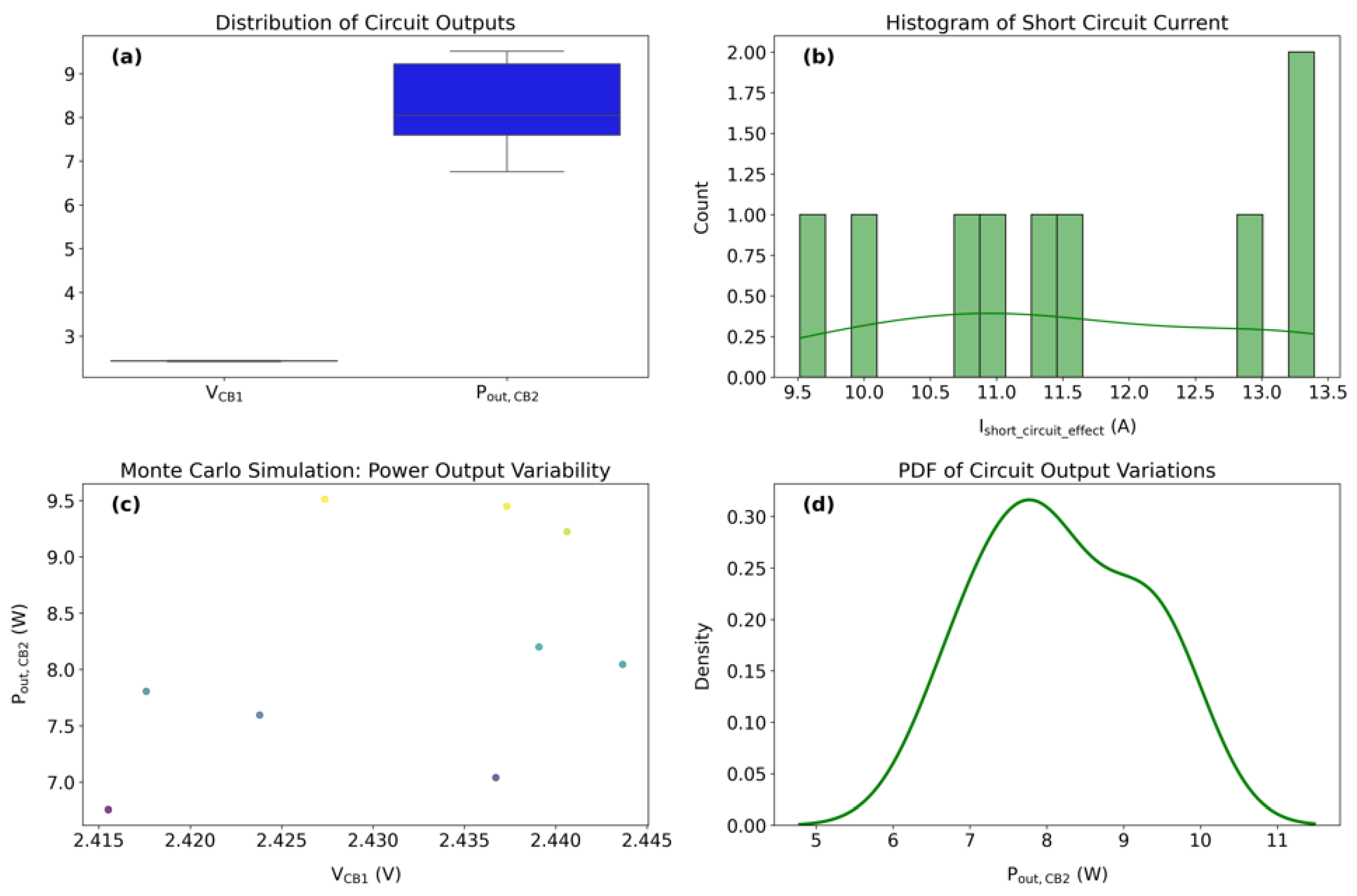

The simulation framework is designed to model the complex electrical interactions governing short circuit behavior within the proposed energy-circuit. It begins with “Circuit Block 1”, which represents the power source, while accounting for practical resistances introduced by connecting wires and the internal resistance of the source. This approach ensures a realistic representation of electrical circuits, acknowledging that completely resistance-free conditions are unattainable. Incorporating these elements allows the simulation to align with real-world constraints, providing an experimentally valid analysis of short circuit phenomena. To establish the transition from transient short circuit currents to a time-dependent and continuous framework, the simulation applies Equation 1 and Equation 5 across experimental through . These equations govern the transformation process, ensuring that short circuit currents evolve dynamically over time. Furthermore, the framework validates that the Modified Ohm’s Law functions coherently between experimental applications (Equation 116) and computational methodologies (the simulation itself), reinforcing the consistency of the proposed model across different investigative approaches. A crucial aspect of the simulation is its ability to experimentally verify the dependency of generated short circuit current on initial circuit power input -an inherent property of the Modified Ohm’s Law. To illustrate this dependency, simulation experiments utilize a power supply. The structured analysis of to provides insights into how the “energy-circuit” responds to controlled disruptions while effectively managing excess power for sustained operation. Addressing the necessity of a robust simulation platform, the paper implements Python-based modeling executed on Google Colab. The choice for Python is driven by two primary factors: accessibility to open-source computational resources and the limitations of conventional circuit simulation tools in handling time-dependent short circuits. A significant challenge in simulating electrical short circuits arises from the constraints inherent in standard circuit simulation software. Programs such as SPICE-based simulators and MATLAB/Simulink, despite their widespread use in circuit analysis, struggle to accurately model short circuits in a dynamic time-dependent framework. These tools primarily operate under steady-state or quasi-static assumptions, making them unsuitable for capturing rapid transient current surges and the continuous evolution of circuit behavior during a short circuit event. Their reliance on predefined stability conditions hinders their ability to represent the dynamic and nonlinear electrical interactions occurring within an actively disrupted circuit. Further assessments highlight the computational limitations of these conventional tools. For instance, LTspice, a widely adopted SPICE-based simulator, relies on fixed time-step algorithms that often fail to resolve the complex relationships between time-varying resistances and transient current responses. Similarly, COMSOL Multiphysics, known for its coupled physics simulations, introduces significant computational overhead that impedes real-time modeling of sustained short circuits. This challenge stems from the numerical instability encountered when solving stiff differential equations over extended timeframes. Specifically, COMSOL’s discretization techniques struggle to maintain accuracy when resolving instantaneous voltage collapses and rapid current escalations inherent to short circuit conditions. As a result, neither tool offers a satisfactory resolution for simulating the continuous evolution of circuit parameters under persistent short circuit scenarios. To overcome these limitations, the Python-based simulation framework utilizes scientific computing libraries to dynamically solve the governing differential equations of the “energy-circuit”. The implementation of adaptive solvers ensures high temporal resolution while mitigating numerical instabilities -issues that often hinder traditional simulation tools, particularly in real-world scenarios such as electrical short circuit measurements and analysis. Additionally, executing the framework on Google Colab enhances scalability by enabling integration with open-source resources while ensuring reproducibility across diverse computational environments.

Voltage Simulation Algorithm. The voltage simulation algorithm codifies the empirical dynamics of voltage collapse observed under short circuit conditions, as reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The process initiates with the external DC power source establishing the voltage at “Circuit Block 1” (CB1), nominally measured at approximately

. Upon activation of the short circuit pathway, a sharp voltage reduction is recorded-dropping to the

range for a

input, and

for a

input. These discontinuities in voltage are algorithmically encoded by introducing a transformation coefficient,

, empirically derived from the ratio between the output voltage under short circuit conditions at “Circuit Block 2” (CB2) and the nominal CB1 voltage. For instance, under a

input scenario, the transformation is captured as:

. Let

denote the stabilized voltage at CB1 immediately before the short circuit is triggered. The function

, formalized in Equation 120, defines the corresponding voltage at CB2 as a scaled response to

under short circuit conditions:

Equation 120 furnishes a deterministic computational law governing voltage translation from CB1 to CB2, embodying the empirical energy dissipation and redistribution phenomena triggered by short circuit events. The algorithm enforces this transformation consistently across simulations, initially assigning the CB1 voltage via controlled DC input, and then applying the scaling factor

to derive the resultant voltage at CB2. Once the transformation is executed, the simulation advances to quantify the instantaneous power output at CB2, using the voltage value obtained from Equation 120. This transition sets the stage for the power simulation captured in Equation 121:

Equation 121 provides a foundational expression for computing the simulated power input into “Circuit Block 3”, a topic further analyzed in subsequent sections. Through this approach, the simulation framework successfully integrates empirical observations with computational modeling, ensuring a comprehensive representation of the circuit’s dynamic voltage behavior under short circuit conditions.

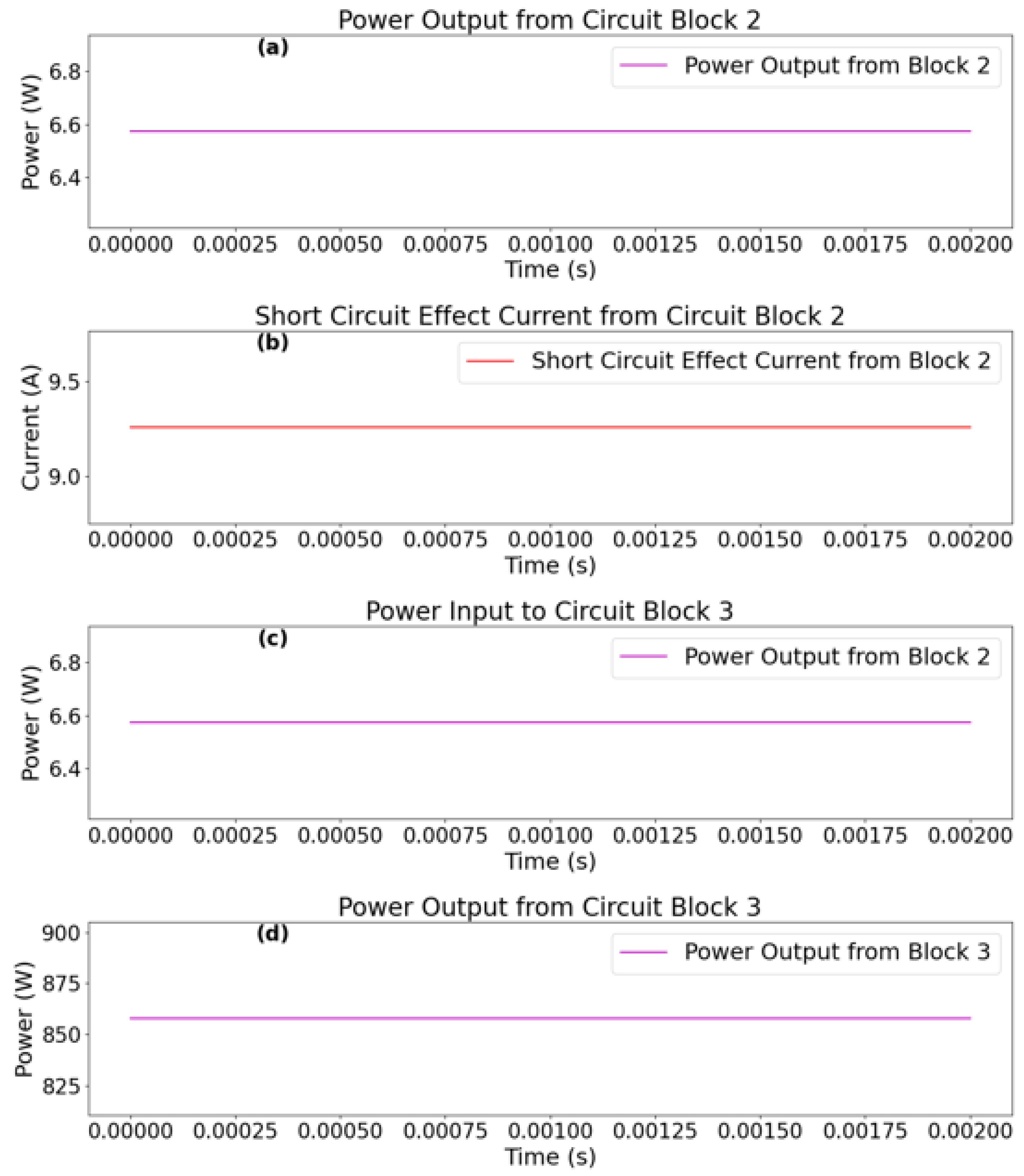

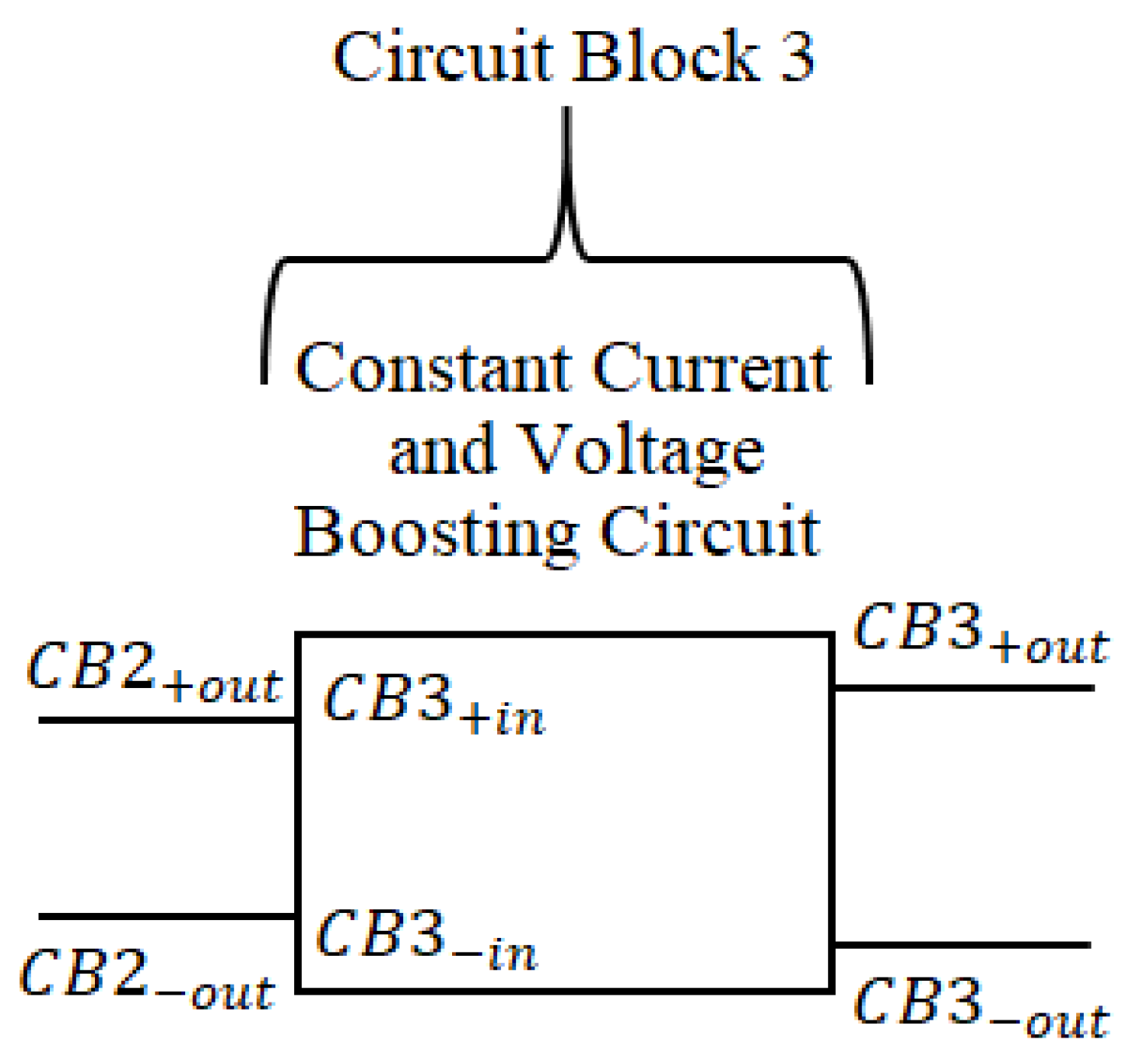

4.3.2. Circuit Block 3 (Advancing Energy Transformation)

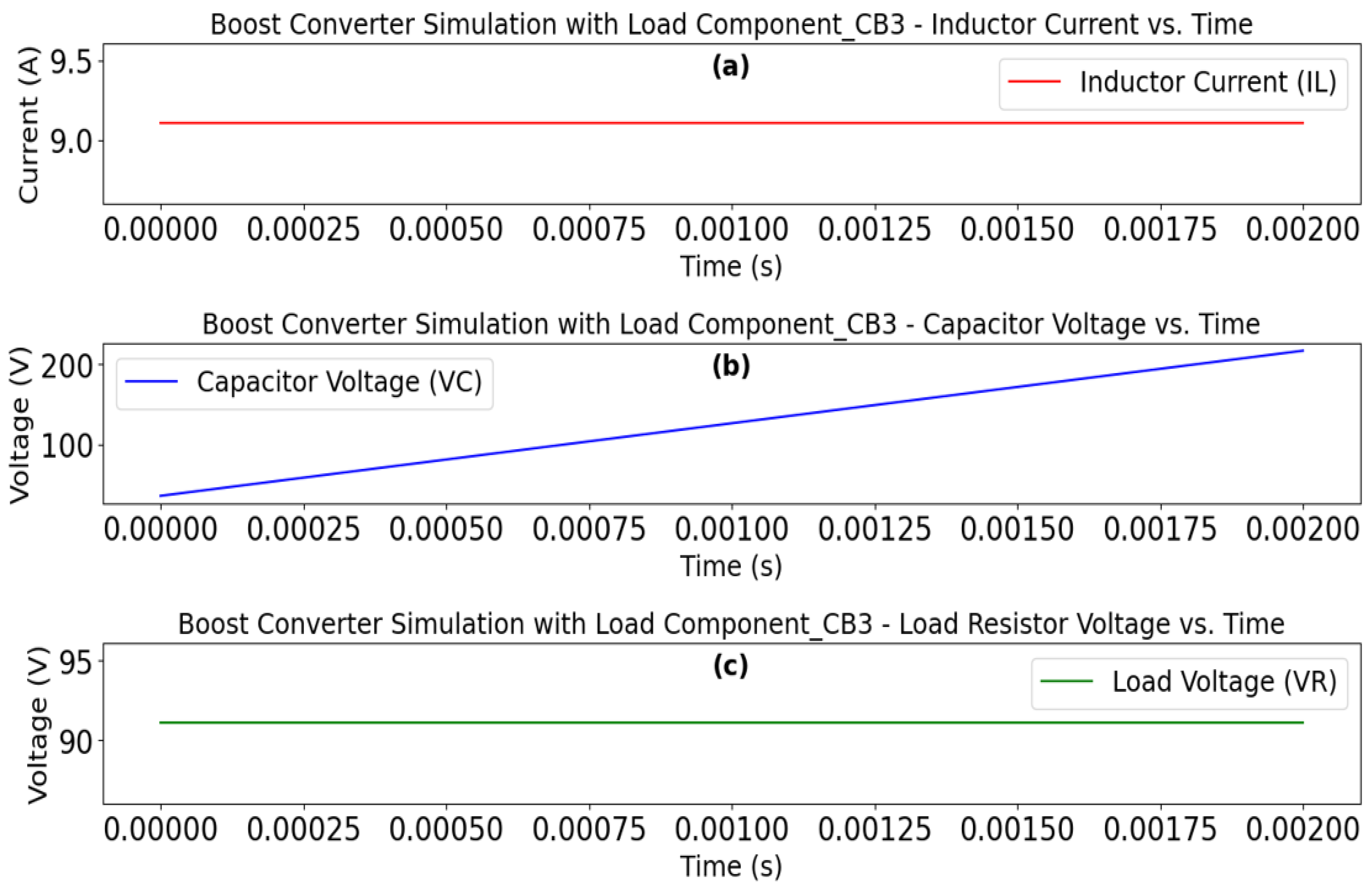

This section introduces “Circuit Block 3”, a crucial component designed to transform the non-Ohmic output from “Circuit Block 2” into an Ohmic format suitable for standard circuit applications. Building upon the energy transformation process, “Circuit Block 3” introduces the “load component_CB3”, with a constant current boost converter characteristics. Unlike “Circuit Block 1” and “Circuit Block 2”, which operate through Ohmic to non-Ohmic state, “Circuit Block 3” aims for an Ohmic state while maintaining a high and consistent current. To achieve this transition, “Circuit Block 3” leverages the existing resistance from “Circuit Block 1”, denoted as (Equation 118), rather than introducing additional resistive elements (a simplification for simulation purposes). This effective resistance is then incorporated into the analysis of energy conservation to investigate the energy-circuit’s behavior. Within “Circuit Block 3”, the “load component_CB3” plays a key role in achieving the Ohmic state while maintaining consistent short-circuit current. Its primary function is to boost the voltage to its highest achievable level while keeping the current constant. Ideally, this component would be a boost converter circuit. This section explores a simplified design for the “load component_CB3” based on mathematical formulas describing the dynamics of the inductor current () and capacitor voltage () over time. The developed mathematical structure, focusing on the inductor and capacitor as the main components of “Circuit Block 3”, will later be used in simulations to analyze the component’s behavior within the “energy-circuit”.

The Inductor Current (). The basic formula for the voltage across an inductor is given by;

In Equation 122,

represents the voltage across the inductor,

is the inductance itself, and

signifies the rate of change of the inductor current over time. Equation 122 is a fundamental relationship used in boost converter applications, and it has been adapted for various purposes by [

83,

84,

85]. In the boost converter circuit, during the on-time (

) of the switch, the voltage across the inductor is the difference between the input voltage (

) and the output voltage (

). This is because the inductor is effectively connected to the input during this time. Further, during the on-time (

) of the switching element, the inductor current (

) increases, and during the off-time (

), the inductor discharges through the load. In this case, we consider the scenarios; due to the on-time (

) and due to the off-time (

).

During ON time (). The voltage across the inductor (

) is equal to the difference between the input voltage (

) and the output voltage (

) according to Equation 123.

Now, relating Equation 123 to Equation 122 we obtain Equation 124, which is to be further reduced as:

.

During OFF time (). The voltage across the inductor (

) is equal to the output voltage (

), a situation expressible according to Equation 125.

Applying Equation 125 to Equation 122 we obtain;

which on rearranging becomes Equation 126.

Next, we express the duty cycle (

) in terms of time. The duty cycle is defined as the ratio of the on-time (

) of the switch to the total time period (

), as expressed in Equation 127.

The total period is the sum of the ON and OFF times and can be expressible according to Equation 128.

Using Equation 127 in Equation 128 we get;

Solving for

and

we have;

Now, we can express the rate of change of inductor current

during the entire period as;

Simplifying Equation 131 further, we obtain Equation 132 as follows.

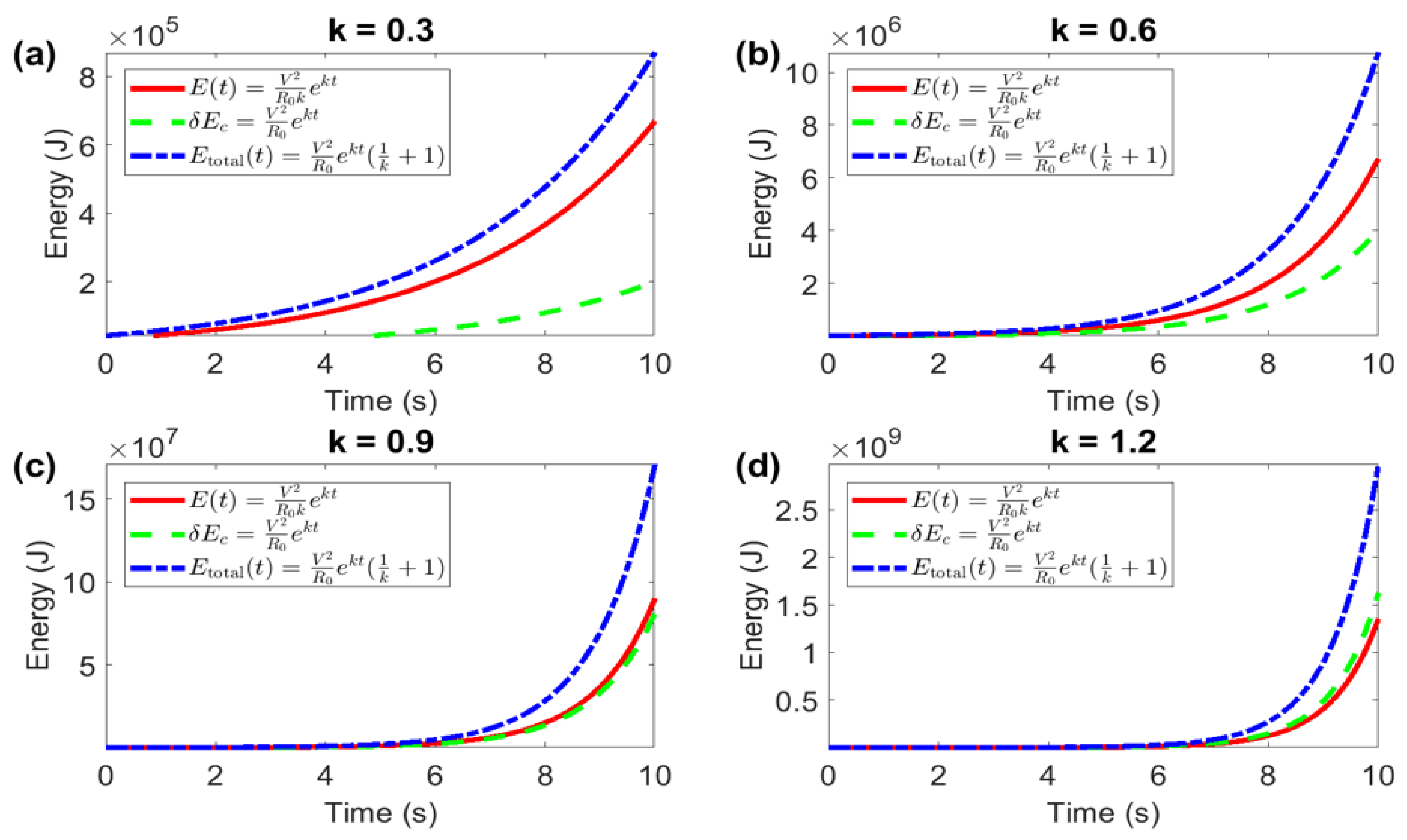

Equation 132 which is a first-order linear differential equation provides the final expression for the rate of change of inductor current with respect to during the entire switching period within the “Circuit Block 3”. If we integrate this equation over time, we can obtain the actual expression for as worked out in the subsequent section.

Remark 9 (On “energy-circuit” Simulation). The on-time () event in “load component_CB3” can be related to the switching frequency () as . Substituting this into the duty cycle definition (Equation 127), we get . This duty cycle definition will later be used for simulating real-world scenarios of the proposed “energy-circuit”.

Solution for the Constancy of . Proceeding from Equation 132, the goal of this workflow is to find the actual expression for

, by integrate both sides of the equation with respect to time

.

Solving Equation 133 gives;

Where is the constant of integration.

Equation 134 can be rewritten to give the following relationship;

The integration of

with respect to time results in

, and the integration of

with respect to time results in

, and the operation can be expressed according to Equation 135.

Equation 135 further simplifies to Equation 136 as follows.

Here, is a constant of integration.

Determining the integration constant . To determine

, we need an initial condition. This can be achieved by setting

, the inductor current

is equal to the short circuit effect current (

), which is the initial condition to be used in the “energy-circuit” simulation.

Substituting and Equation 137 into Equation 136, we then solve for as follows;

, which reduces to Equation 138.

Now, substituting Equation 138 back into Equation 136 we obtain;

, which simplifies to:

Equation 139 provides the actual expression for the inductor current () as a function of time in the boost converter circuit for “Circuit Block 3”.

Capacitor Voltage (). To complete the mathematical representation of the capacitor voltage (

) equation, this section uses the fundamental relationship in circuit analysis, which relates the current (

), capacitance (

), and voltage (

) for a capacitor according to Equation 140.

In this case, the current

is the inductor current (

), and the voltage

is the capacitor voltage (

) [

84]. Therefore, Equation 140 becomes.

Now, the next task is to solve the differential Equation 141 for , since the inductor current () is known from the boost converter equations through Equation 138.

Rearranging Equation 141 we get;

We then integrate Equation 142 with respect to time to obtain Equation 143.

Where

is the constant of integration. Substituting for

from Equation 140:

Solving Equation 144 reduces the problem to:

This equation represents the voltage across the capacitor as a function of time. The integration constant would be determined by the initial voltage condition across the capacitor, typically provided in the problem statement or the energy-circuit's initial state.

Determining the integration constant . The constant

is determined using the initial condition for the capacitor voltage, typically

. Assume at

, the capacitor voltage is known:

Substituting

into the expression for

(Equation 145) we obtain:

, which simplifies to:

Thus, the expression for the capacitor voltage becomes:

Equation 148 gives the expression for the capacitor voltage () in terms of the inductor current () and other circuit parameters constituting the “load component_CB3”. The equation suggests that the voltage across the capacitor changes over time due to the combined effects of the inductance , the difference between the input and output voltages , and a short circuit current effect . The equation is quadratic in time , indicating that the voltage may increase non-linearly over time due to the inductive effects, and also linearly due to the short circuit effect. The term involving suggests that the inductive component contributes to a parabolic increase in voltage over time, while the term involving suggests a linear contribution from the short circuit effect. The mathematical formulations through “Circuit Block 3” will be highly relied on, through simulating the provided “energy-circuit”.

“Load Component_CB3” Major Simulation Elements-An Overview. “Load Component_CB3” is a specialized circuit designed to efficiently convert excess energy from “Circuit Block 2” into a usable DC voltage. This voltage boost is essential for integrating the energy circuit into conventional electrical systems. The circuit's ability to handle low input voltages, as shown in

Table 1, makes it a valuable component for exploring potential applications that challenge traditional energy conservation paradigms.

Inductor (L). The inductor value (

) in the “load component CB3” significantly influences energy storage and transfer. Its selection is based on factors including desired output voltage, input voltage, duty cycle, switching frequency, and ripple current. The inductor must be capable of handling the required current and operating within the specified input voltage range. For simulation purposes, the inductor value will be fixed.

Equation 149 considers;

is the inductor value.

is the desired output voltage.

is the input voltage.

is the duty cycle of the converter.

is the switching frequency.

is the peak-to-peak inductor ripple current.

Switching Element. In practical settings, the objective here is to choose a switching element (such as MOSFET) capable of handling the desired voltage and current while minimizing ON resistance (). The procedure involves considering the voltage rating, ensuring the switching element in this context can handle maximum current, and selecting a switching element with low ON resistance to reduce power losses.

Diode (D). In this step, a diode can be selected with a voltage rating higher than the desired output voltage. The diode is crucial for allowing current flow and maintaining the desired output voltage.

Output Capacitor (C). In designing the “Load Component_CB3”, the output capacitor should be capable to handle the output current and maintain the required output voltage. This component assists in smoothing out voltage variations and ensuring stability in the output.

Remark 10 (Energy Transformation in “Circuit Block 3”). The selection of “

load component_CB3” enhances the overall efficiency of the energy circuit and its role in challenging conventional energy conservation laws. Specifically, it facilitates the transformation of the excess energy generated in “Circuit Block 2” from a non-Ohmic to an Ohmic framework, questioning the global validity of energy conservation. Within “Circuit Block 3”, the primary objective is to refine the outputs derived from “Circuit Block 2” into an Ohmic format suitable for standard circuit applications. This transformation is a crucial step toward integrating the circuit into conventional electrical systems while maintaining its theoretical significance.

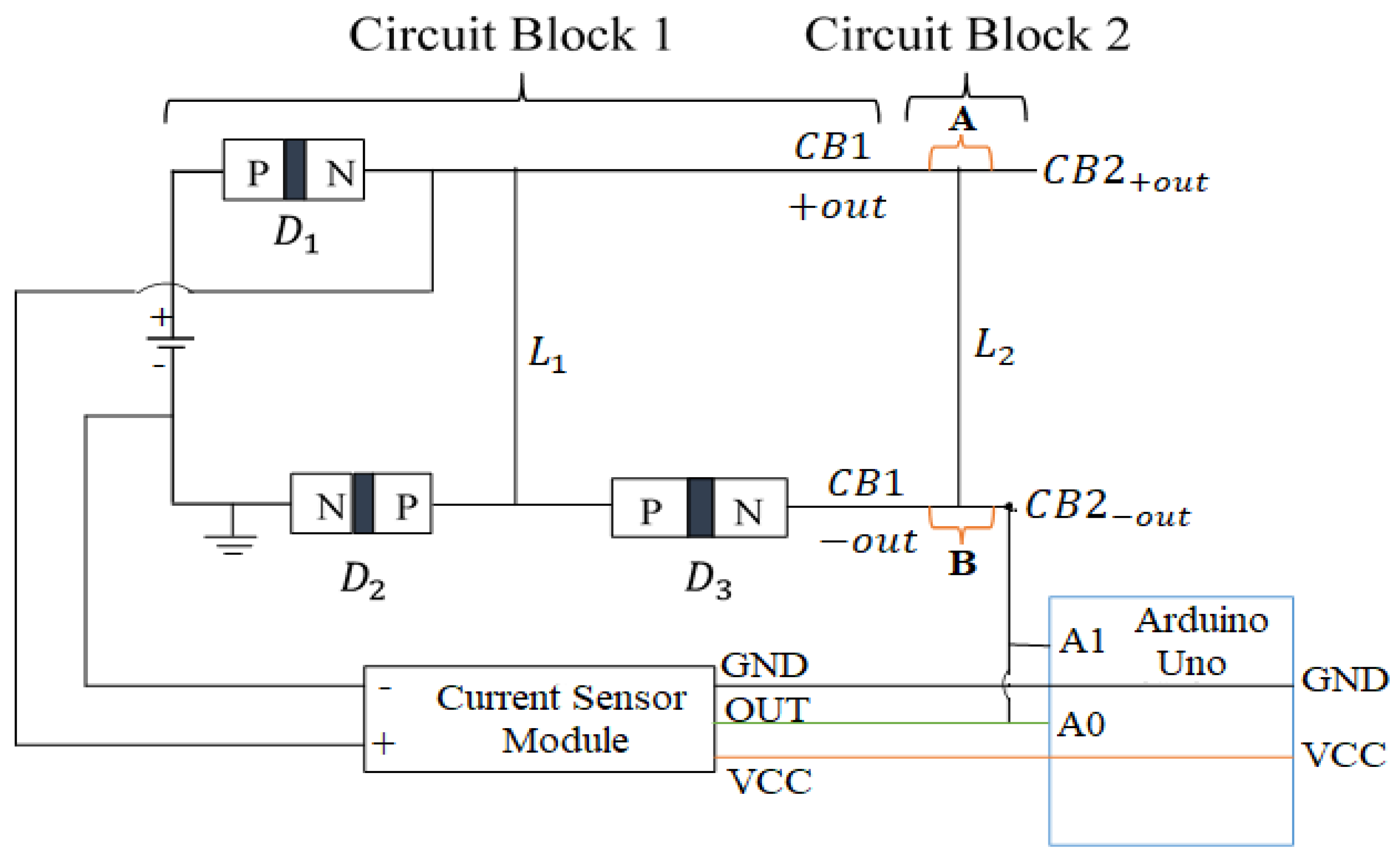

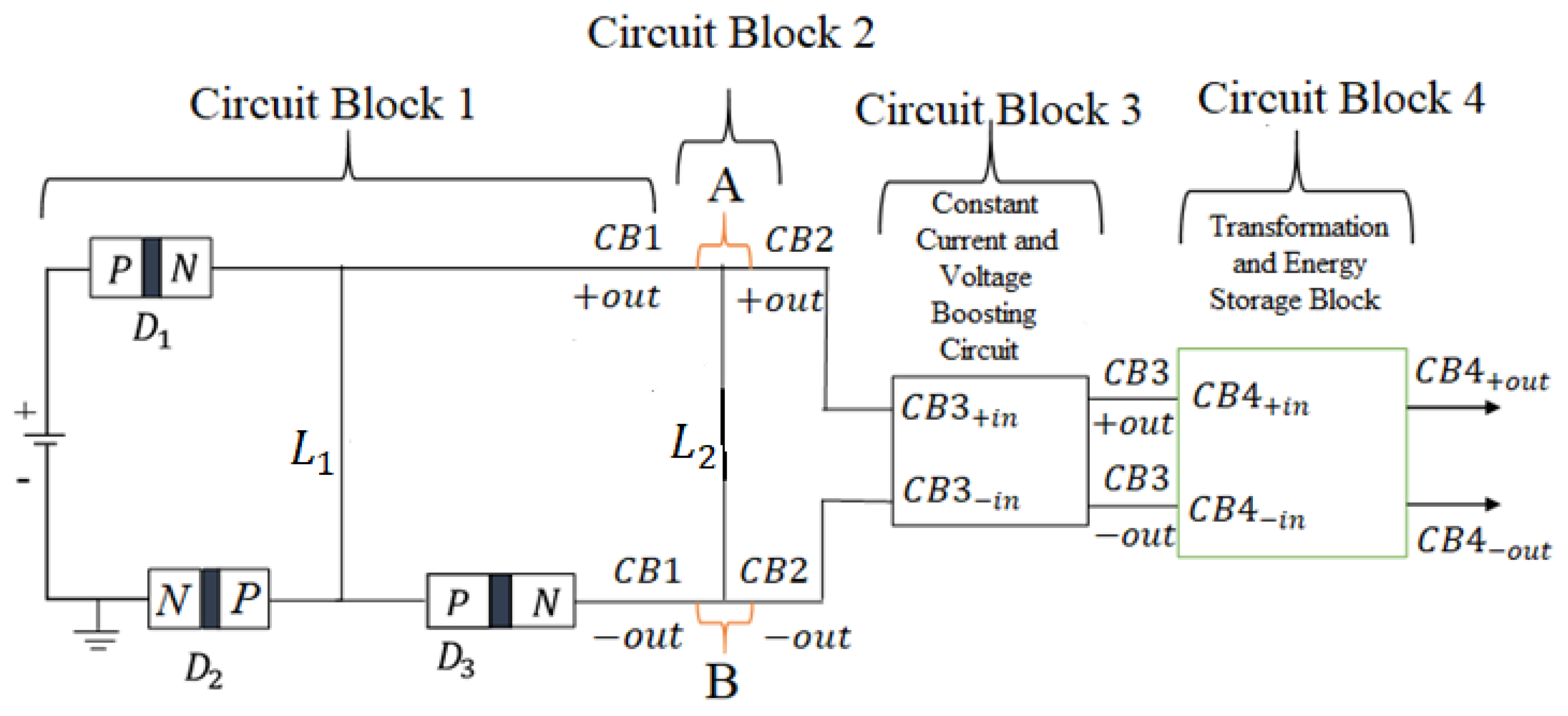

Figure 13 provides a block diagram of the “energy-circuit” component, “Circuit Block 3”.

A Skeptics Note (Clarifying Energy Transformation in “Circuit Block 3”). The primary role of “Circuit Block 3” is to transition the energy circuit from the non-Ohmic framework introduced through “Circuit Block 1” and “Circuit Block 2” to an Ohmic model compatible with existing engineering systems, rather than to generate excess power. The objective of challenging the law of energy conservation is already demonstrated in “Circuit Block 2”, as detailed in the results section. Indeed, both theoretical and experimental findings suggest that future research could further explore multiple frameworks for breaking the law of energy conservation at macroscopic levels, based on the proposed circuit model, depicted in

Figure 12. Therefore, “Circuit Block 3” serves primarily as an interface that aligns the energy circuit with conventional electrical systems, ensuring practical compatibility. Given its higher power input and output compared to external power inputs to “Circuit Block 1”, as indicated in

Table 3 and

Table 4, it facilitates seamless integration into existing infrastructure by utilizing excess power for voltage amplification. This design highlights adaptability to modern electrical and electronic technologies. This clarification is necessary due to skepticism regarding the introduction of capacitive and inductive elements into the energy circuit, which some argue undermines the possibility of energy creation. However, this paper presents a distinct perspective, emphasizing that the energy-generation framework in “Circuit Block 1” and “Circuit Block 2” is strictly resistive, built upon materials -such as diodes -that do not store substantial electric charge. Any argument seeking to invalidate the proposed circuit model beyond “Circuit Block 2” is therefore rooted misconceptions either related to perpetual motion machines (PMMs) or otherwise. Notably, this paper does not focus on developing PMMs but rather on re-examining the fundamental principles governing energy conservation.

4.3.3. Circuit Block 4 (Post Energy Generation-Energy Storage Component)

This section extends the discussion into a familiar domain -energy storage frameworks. “Circuit Block 4” addresses a critical aspect of the proposed energy circuit: the storage and management of harnessed energy. While “Circuit Block 3” is responsible for transforming excess power generated by “Circuit Block 1” and “Circuit Block 2”, the ability to store this energy effectively is essential for practical applications. Therefore, this section focuses on the role of “Circuit Block 4” as the energy storage component, a fundamental element in any energy system. The significance of “Circuit Block 4” lies in its function as an energy conservation interface. It captures the output power from “Circuit Block 3” and optimizes its distribution for various applications. This process may involve integrating a power control unit that regulates the output, ensuring that energy is efficiently managed and adjusted to meet different operational requirements. Additionally, “Circuit Block 4” can incorporate energy storage mechanisms such as batteries or supercapacitors, allowing surplus energy to be retained for future use. This capability introduces the possibility of a self-sustaining energy circuit, a concept that aligns with the growing interest in sustainable energy solutions. The idea of self-charging systems has gained considerable attention in recent years, particularly in response to the increasing demand for renewable and autonomous energy sources. Although fully operational self-charging electrical circuits have yet to be realized, advancements in magnetic resonance and metamaterials offer promising directions for future exploration [

86,

87,

88,

89,

90]. Within this context, “Circuit Block 4”, through its energy storage capabilities, establishes a foundation for further research in this field. A key component of “Circuit Block 4” is its power control unit, which plays a crucial role in managing the excess energy transferred from “Circuit Block 3”. This unit ensures a smooth transition to a stable power level by precisely regulating energy flow, thereby minimizing losses and maintaining power quality. Furthermore, it facilitates voltage alignment with the power supply or even enables an increase to higher desired values. This controlled adjustment establishes a regenerative loop, potentially challenging conventional energy conservation principles while maintaining a consistent power output.

Figure 14 presents the overall energy circuit configuration, illustrating the specific components within “Circuit Block 4” through a block diagram. Thus, “Circuit Block 4” serves as both a storage mechanism for the generated energy and a potential enabler of self-charging functionality. While fully autonomous self-charging energy systems remain an area of ongoing research, the design principles underlying “Circuit Block 4” offer valuable insights into future advancements in energy generation, storage, and management.

Selection of the “Circuit Block 4” Energy Storage Unit. The role of “Circuit Block 4” within the proposed energy circuit is to incorporate an efficient energy storage mechanism that captures and manages the high-power output generated by “Circuit Block 4”. Among various storage options, this paper emphasizes the advantages of a capacitor-based system while acknowledging alternative solutions for diverse applications. A well-designed capacitor-based storage unit ensures efficient energy management through a dedicated circuit comprising a diode to prevent reverse current flow, a current-limiting resistor to regulate charging speed, and a voltage regulator to maintain optimal charging levels [

91,

92]. During discharge, a controlled switch and a load resistor facilitate a stable energy release. Capacitors are particularly advantageous due to their rapid charging and discharging capabilities, which align with the high-power nature of “Circuit Block 4”. Additionally, their long cycle life ensures durability over repeated charge-discharge cycles, and their low internal resistance enhances energy transfer efficiency. However, alternative storage technologies merit consideration based on specific application needs. Traditional batteries, such as Lithium-ion (Li-ion) and Lithium Polymer (Li-poly), offer higher energy density, enabling greater energy storage within a compact volume, though they lack the rapid energy release efficiency of capacitors [

93,

94]. Supercapacitors provide an intermediate solution by combining the high energy density of batteries with the fast charging and discharging characteristics of capacitors [

95]. Another alternative, the flywheel energy storage system, utilizes mechanical rotation for energy retention, delivering high power output but requiring more space [

56]. Given these considerations, selecting the most suitable storage unit for “Circuit Block 4” depends on balancing response time, energy capacity, and operational efficiency.

Remark 11 (Recommendation and Considerations). The choice between a capacitor-based storage system and alternative solutions depends on the specific requirements of the application. For scenarios demanding rapid response times and frequent charge-discharge cycles, capacitors offer an optimal solution. In contrast, applications requiring higher energy density and extended storage durations may benefit more from batteries or supercapacitors. A careful assessment of the operational constraints and performance needs is essential to determine the most appropriate energy storage unit for “Circuit Block 4”.

4.3.4. Circuit Block 5 (Automation and Safety Control)

The sequential development from “Circuit Block 1” through “Circuit Block 4” demonstrates the achievement of the paper’s primary objective -energy generation in “Circuit Block 1” and “Circuit Block 2”, followed by energy transition and storage in “Circuit Block 3” and “Circuit Block 4”. However, the safe and controlled operation of the energy circuit remains crucial, particularly when adapting the system to real-world applications where power requirements vary. To address this need, “Circuit Block 5” is introduced as an automation and safety control mechanism, ensuring the system operates within safe limits while maintaining optimal efficiency. The integration of “Circuit Block 5” is essential for regulating short circuit current outputs and durations, especially since prolonged short circuits may be unnecessary or even detrimental, depending on the power source and application. To achieve this, an automated control mechanism is recommended to manage the on-off durations of power creation events. Previous experiments incorporated an Arduino-based sensor system to measure output voltage and current within the energy circuit, demonstrating the feasibility of real-time monitoring. A similar sensing system can be implemented in “Circuit Block 5” to control the timing of short circuit events and facilitate seamless energy generation. Functioning as a critical safeguard, “Circuit Block 5” actively monitors the short circuit current within “Circuit Block 2” and dynamically adjusts the system’s parameters when necessary. This is achieved by integrating a sensor system consisting of a current sensor and a microcontroller, which continuously tracks current flow and detects abnormal fluctuations or prolonged high-current levels. Given that the “energy-circuit” model has the potential for a cycle-recharging mechanism, the control system intervenes when a risk is identified. It either terminates the short circuit event or momentarily disrupts it after supplying excess current for a predefined duration. This safety feature is particularly significant in light of research findings that highlight the risks associated with prolonged short circuits, including contact welding in electrical systems, even in vacuum environments [

96]. Through the implementation of a dynamic control system, “Circuit Block 5” mitigates these hazards and enhances the overall safety of the energy circuit. Beyond its protective function, “Circuit Block 5” plays a pivotal role in balancing energy generation and system reliability. By precisely regulating short circuit durations, it ensures that maximum energy is extracted without compromising the stability of the system or connected components.

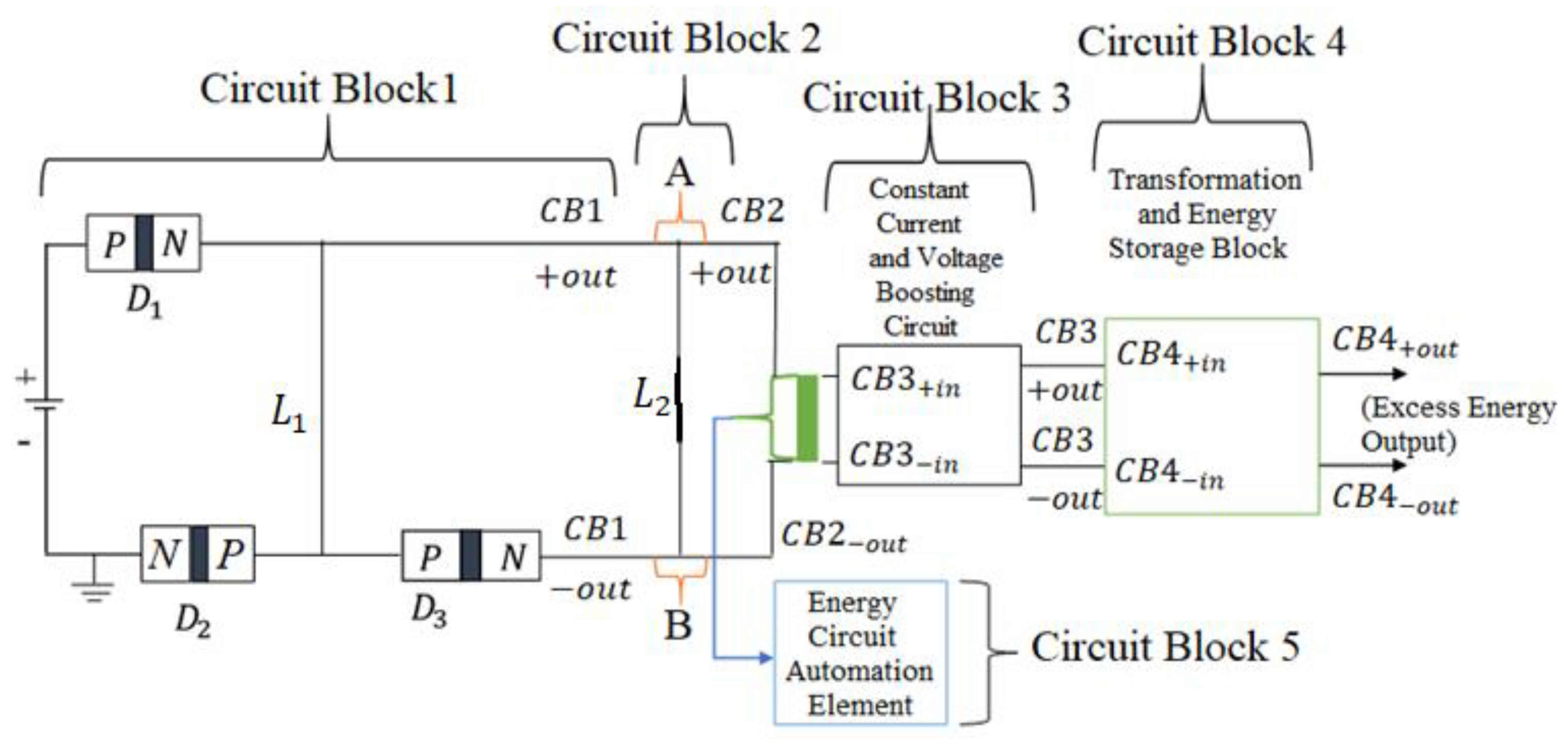

Figure 9 presents a block diagram illustrating the placement of “Circuit Block 5” within the overall “energy-circuit” configuration, emphasizing its role in maintaining both efficiency and safety.

The Sensing Element Operation Mechanism. The operation of “Circuit Block 5” is centered on a sensing element that continuously monitors the short circuit current input to “Circuit Block 3”, particularly at nodes and . The current sensor generates an analog signal proportional to the short circuit current, which is then processed by the microcontroller. Predefined threshold values establish safe operating limits for the short circuit duration, ensuring that the system operates within optimal parameters. The microcontroller continuously compares real-time current measurements against these thresholds and autonomously adjusts the duration of the short circuit event when necessary. If the detected short circuit current exceeds or falls below acceptable limits, the microcontroller activates an automation mechanism to regulate the energy circuit’s operation. This closed feedback loop ensures continuous communication between the sensor, microcontroller, and the broader energy system, enabling real-time adjustments that enhance both safety and energy efficiency.

Remark 12. The sensing element in “Circuit Block 5” operates using an external power source independent of the input power supplied to “Circuit Block 1”. However, a significant advantage of the “energy-circuit” model is its ability to self-sustain, making it possible to power the sensing element using excess energy stored in “Circuit Block 4”. Experimental results indicate that the final output energy from “Circuit Block 3” is significantly higher than the initial input energy supplied to “Circuit Block 1”. This intentional design enables the sensing element to transition from relying on an external power source to a self-sustaining mode, further enhancing the autonomy and efficiency of the system. This dual-mode functionality aligns with the self-charging characteristics of the “energy-circuit” model, reinforcing its innovative approach to energy generation and management.

Remark 13. Overall “energy-circuit” Representation. The overall configuration of the energy circuit, encompassing all major components from power input to energy storage, is illustrated in

Figure 9. The automation block (“Circuit Block 5”) is strategically positioned before “Circuit Block 3”, forming an integrated system that optimizes energy utilization while ensuring safety and reliability. This block diagram provides a comprehensive representation of the energy circuit’s design, highlighting the interconnections between circuit components and the crucial role of automation in regulating energy flow. Through this structured approach, the “energy-circuit” model presents a novel framework that combines energy generation, unconventional conservation, and intelligent control mechanisms.