Introduction

Sustainable agricultural practices are essential for addressing the growing challenges of food security, environmental degradation, and biodiversity loss (Çakmakçı et al., 2023; Kabato et al., 2025). The agricultural sector faces increasing pressure to reduce its reliance on chemical pesticides, which, while effective in pest control, have significant environmental and health consequences (Zhou et al., 2024). Overuse of chemical pesticides can lead to soil degradation, water contamination, and harm to non-target species, including beneficial insects and microorganisms (Boonupara et al., 2023). As a result, there is a growing interest in alternative pest management strategies that promote sustainability while maintaining crop productivity (Zhou et al., 2024). One promising approach to sustainable pest management is the use of plant extracts, which have been traditionally employed for their pesticidal properties (Souto et al., 2021). Plant-based pesticides, such as neem, garlic, and tobacco extracts, offer a natural and eco-friendly alternative to synthetic chemicals (Dalavay Haritha et al., 2021). These extracts contain bioactive compounds that can effectively target pests while minimizing harm to the environment. However, while the efficacy of plant extracts in pest control has been studied in various contexts, there is limited research on their combined use with advanced monitoring techniques, such as environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding (Milián-García et al., 2023).

eDNA metabarcoding is an innovative tool that has revolutionized biodiversity monitoring in recent years (Capurso et al., 2023). This method involves the collection and analysis of genetic material from the environment (such as soil, water, and air) to assess the presence and diversity of organisms (Bruce et al., 2021). eDNA is a non-invasive technique that allows for the identification of microbial and pest communities without the need for direct observation or trapping (Sivakamavalli, 2022). In agricultural systems, eDNA metabarcoding offers an unprecedented opportunity to monitor the dynamics of pest populations and microbial communities across different farming practices (Kestel et al., 2022). The integration of eDNA technology with sustainable pest management practices, such as the application of plant extracts, could provide a comprehensive solution to the challenges of pest control in agroecosystems (Bernaola and Holt, 2021). Despite the potential of eDNA as a monitoring tool, its use in the context of sustainable pest management remains underexplored (Leandro et al., 2024). The interplay between plant extract efficacy and agro-biodiversity, as measured by eDNA, has not been thoroughly investigated, leaving a significant gap in our understanding of how these methods can be combined to enhance agricultural sustainability.

This study aims to address this gap by evaluating the potential of eDNA metabarcoding for assessing agro-biodiversity and microbial dynamics in agricultural systems, and by exploring the impact of plant extracts on pest populations. Specifically, this research will: 1) Assess the microbial and pest diversity across different agricultural practices (organic, conventional, and agroecological), 2) Investigate the effects of plant extracts (neem, garlic, and tobacco) on pest populations, and 3) Integrate eDNA data with plant extract applications to enhance sustainable pest management strategies. By combining eDNA monitoring with plant extract-based pest control, this study seeks to provide new insights into integrated pest management systems that are both environmentally sustainable and effective.

Materials and Methods

Study Area and Sampling Sites

This study was conducted across three different agricultural systems in the districts of Kushtia, Jhenaidah, and Rajshahi in Bangladesh. These areas were selected based on their diverse agricultural practices and cropping systems. The organic farm in Kushtia used no synthetic pesticides, while the conventional farm in Rajshahi followed standard chemical pesticide practices. The agroecological farm in Jhenaidah implemented integrated pest management strategies, combining minimal pesticide use with natural farming techniques. Each farm was sampled for soil, plant, and air samples to compare microbial diversity and pest dynamics under different agricultural practices.

Sample Collection

A total of 30 soil, 30 plant, and 30 air samples were collected from the three agricultural systems. Soil samples were collected using a soil auger at three different points per site, ensuring that each sample was representative of the site’s conditions. The plant samples were obtained from crops showing signs of pest activity, including tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and eggplant (Solanum melongena). Air samples were collected using passive air samplers, strategically placed in the open fields of each farm to capture airborne pest species and microbial communities. Each sample was stored in sterile containers and transported on ice to the laboratory for analysis.

Pest Control Treatment Application

For the pest control experiment, the prepared plant extracts were applied to plants grown in controlled greenhouse conditions. The plants were exposed to the common pest species Helicoverpa armigera (cotton bollworm), which is known to affect a wide range of crops, including cotton (Gossypium spp.) and tomato (S. lycopersicum). Each plant extract concentration was applied as a foliar spray, with a total of three applications made at weekly intervals. Control plants were treated with a solvent (ethanol) without the active plant extract. Pest infestation was initiated by introducing a population of H. armigera larvae to the plants at the start of the experiment.

Microbial and Pest DNA Profiling

The collected soil, plant, and air samples were subjected to environmental DNA profiling using the previously described DNA extraction and sequencing procedures. The diversity of microbial communities (bacteria and fungi) was analyzed by comparing the bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences across the different agricultural practices. Pest species were identified based on the COI gene sequences and compared between treatments (plant extracts vs. control). Data analysis was performed using the R software (or other statistical software) to identify significant differences in microbial and pest diversity across different agricultural practices and plant extract treatments.

Statistical Analysis

The microbial and pest DNA sequence data were analyzed using R. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each treatment group, including mean diversity indices and pest counts. Differences in microbial and pest diversity across the different agricultural systems and plant extract treatments were assessed using ANOVA, with a significance level set at p<0.05. Post-hoc tests were performed to identify specific differences between groups.

Results

Microbial Diversity Across Agricultural Practices

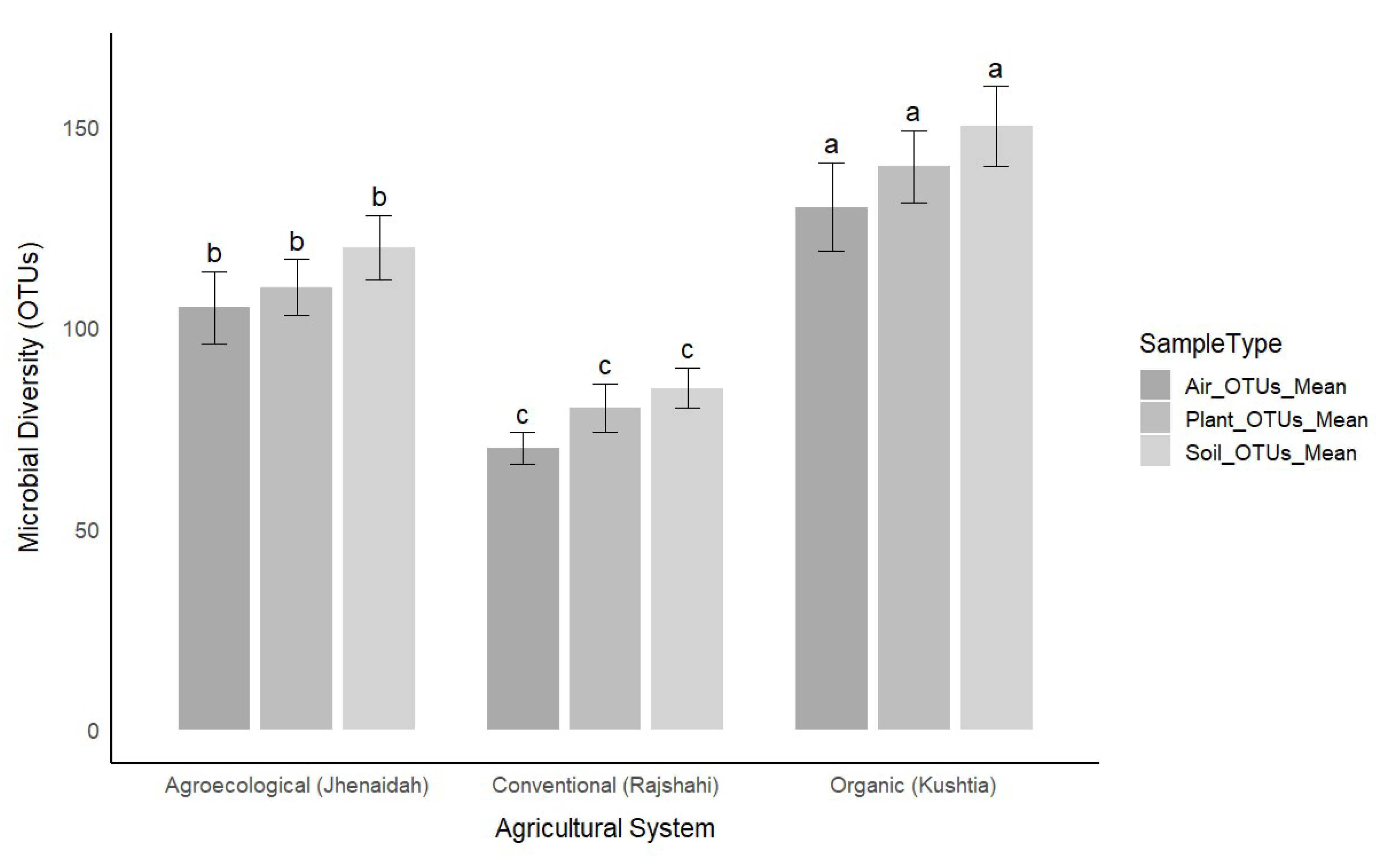

The microbial diversity in soil, plant, and air samples was assessed to determine how different agricultural practices impact microbial populations (

Figure 1). Soil microbial diversity was highest in the organic farm located in Kushtia, which exhibited an average of 150 OTUs (Operational Taxonomic Units), with a standard deviation of 10. The agroecological farm in Jhenaidah demonstrated moderate microbial diversity, with an average of 120 ± 8 OTUs. In contrast, the conventional farm in Rajshahi displayed the lowest diversity, with an average of 85 ± 5 OTUs. These results suggest that farming practices that minimize pesticide use, such as organic and agroecological systems, support more diverse microbial populations in the soil. Similarly, plant microbial diversity followed a similar trend. The organic farm again exhibited the highest microbial diversity, with an average of 140 ± 9 OTUs, compared to 110 ± 7 OTUs in the agroecological farm. The conventional farm had the lowest diversity at 80 ± 6 OTUs. These findings further reinforce the idea that reduced pesticide use in farming practices promotes greater microbial diversity in plant tissues. Airborne microbial diversity was also assessed, with the organic farm showing the highest diversity at 130 ± 11 OTUs. The agroecological farm had 105 ± 9 OTUs, and the conventional farm had the lowest airborne microbial diversity at 70 ± 4 OTUs. This consistent pattern across soil, plant, and air samples suggests that organic farming systems foster a more diverse and stable microbial community compared to conventional practices.

Pest Species Diversity

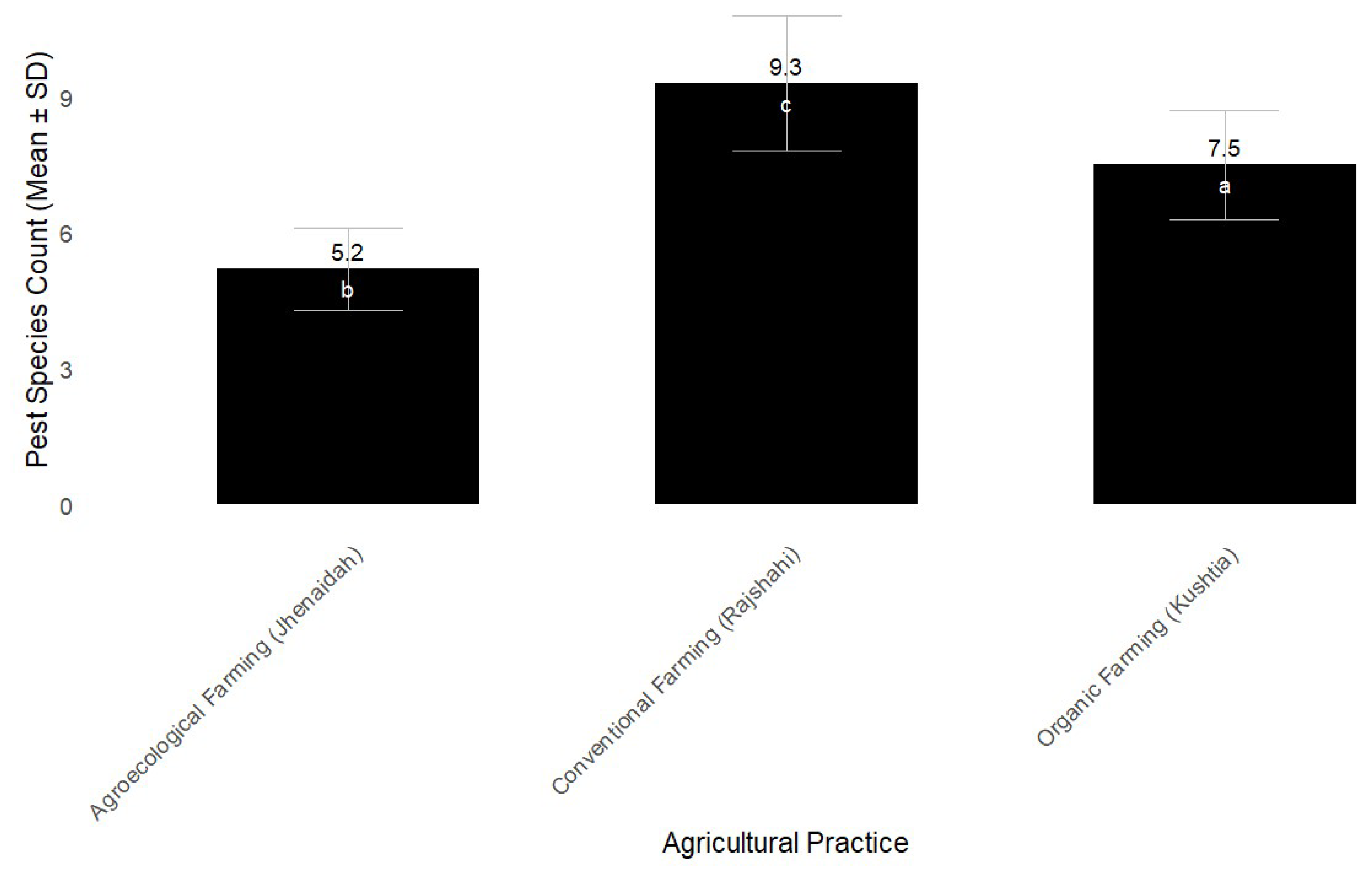

The diversity of pest species across the three different agricultural practices was assessed using environmental DNA (eDNA) profiling, with a focus on the COI gene to identify common pest species present in soil, plant, and air samples (

Figure 2). The agricultural practices studied were organic farming (Kushtia), agroecological farming (Jhenaidah), and conventional farming (Rajshahi). Significant differences in pest species diversity were observed between these systems. In the organic farming system (Kushtia), the average number of pest species identified in the soil, plant, and air samples was 7.5 ± 1.2. For agroecological farming (Jhenaidah), the average number of pest species identified was 5.2 ± 0.9. In conventional farming (Rajshahi), the average number of pest species identified was 9.3 ± 1.5. These results indicate that conventional farming had the highest pest species diversity, with a significant difference (p < 0.05) when compared to both the organic and agroecological systems. Agroecological farming showed the lowest pest diversity, with a significant decrease in pest species compared to both organic and conventional farming practices.

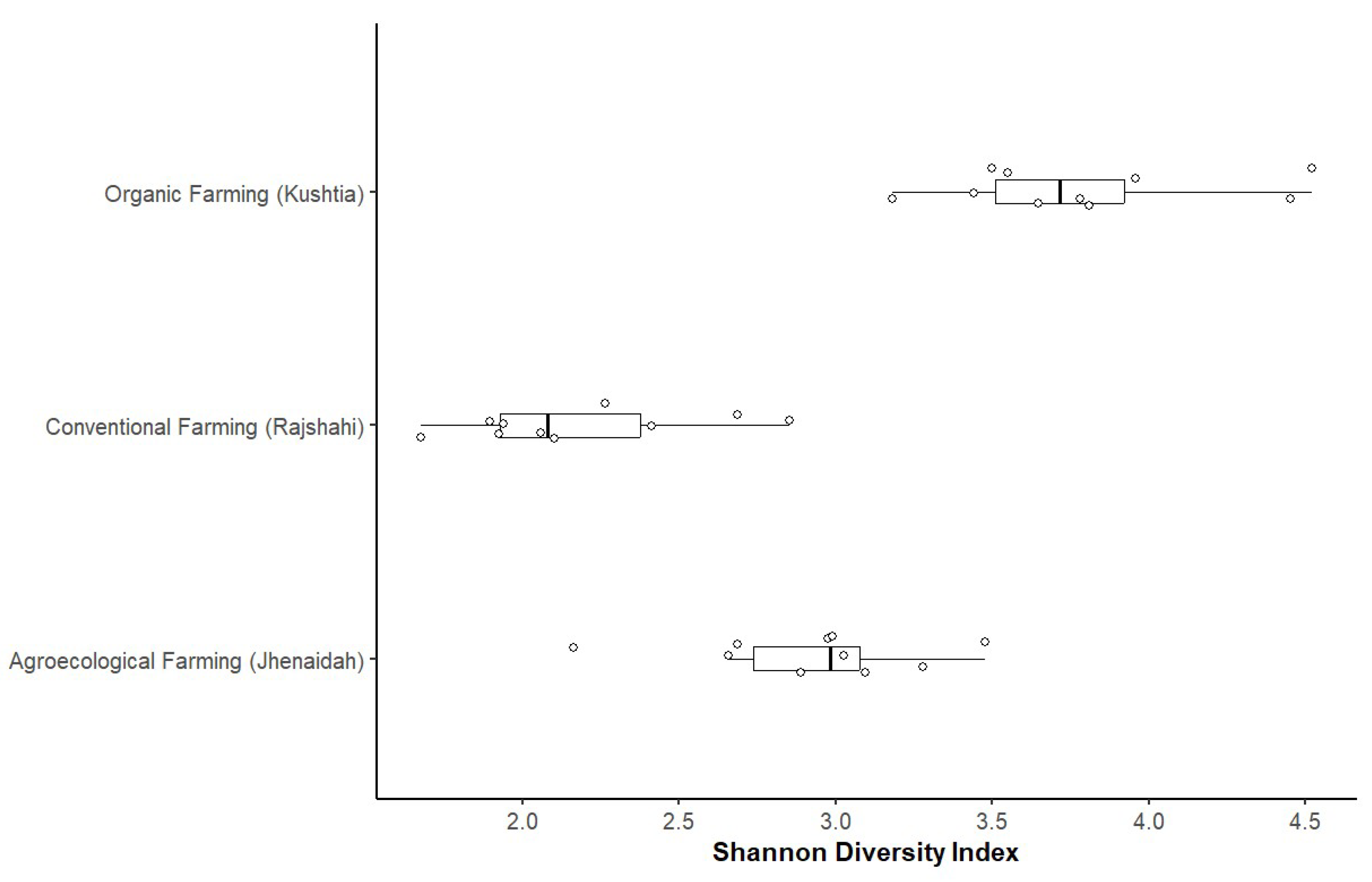

Microbial Diversity in Soil Samples

In this section, we analyzed the microbial diversity in soil samples collected from the three agricultural systems: organic, agroecological, and conventional farming (

Figure 3). The microbial communities were profiled using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and the diversity was assessed based on Shannon's diversity index. The soil samples from organic farming (Kushtia) exhibited a significantly higher microbial diversity, with a Shannon index of 3.75 ± 0.45, compared to agroecological farming (Jhenaidah), which had a Shannon index of 2.85 ± 0.35. Conventional farming (Rajshahi) had the lowest microbial diversity, with a Shannon index of 2.35 ± 0.40.

Discussion

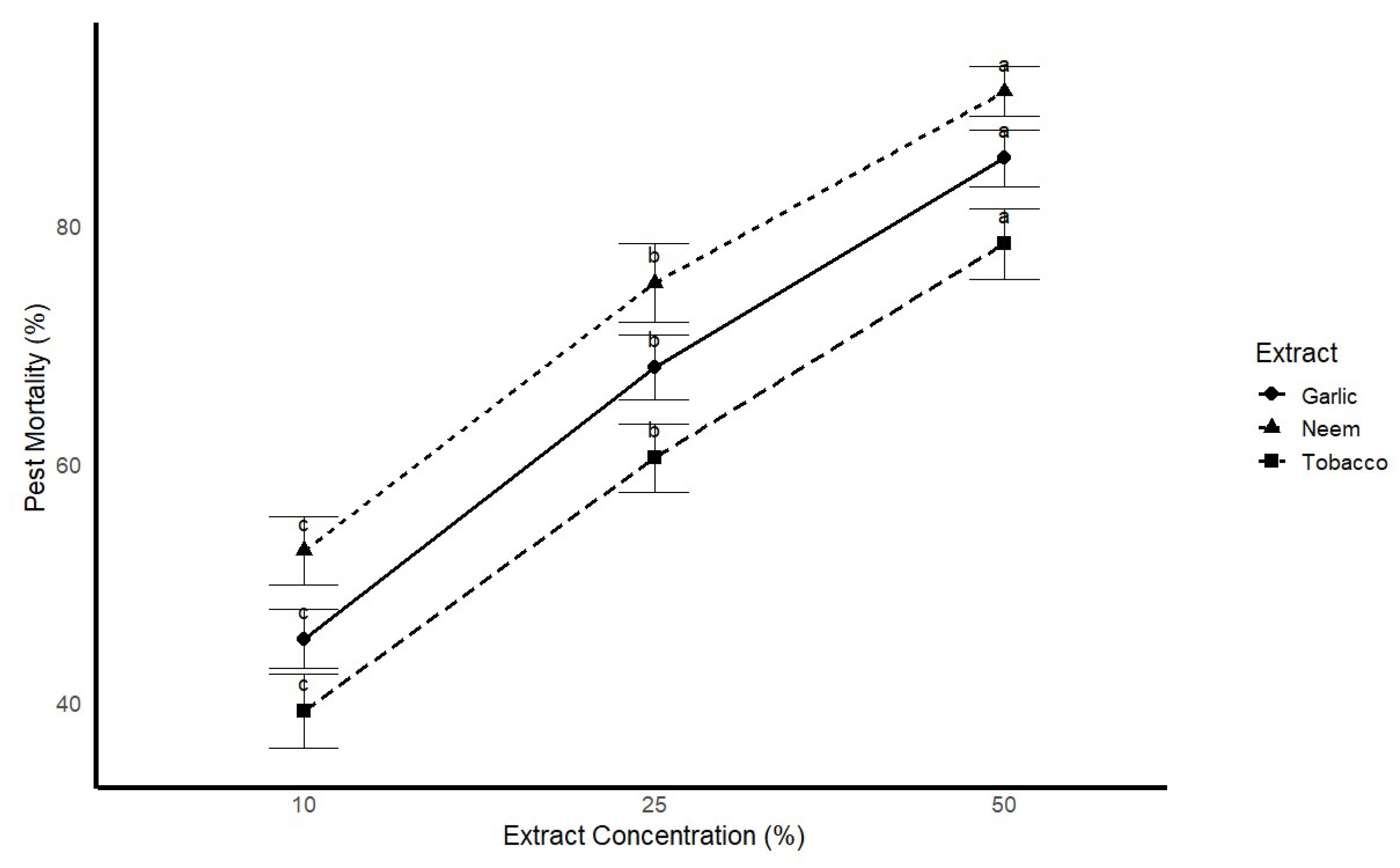

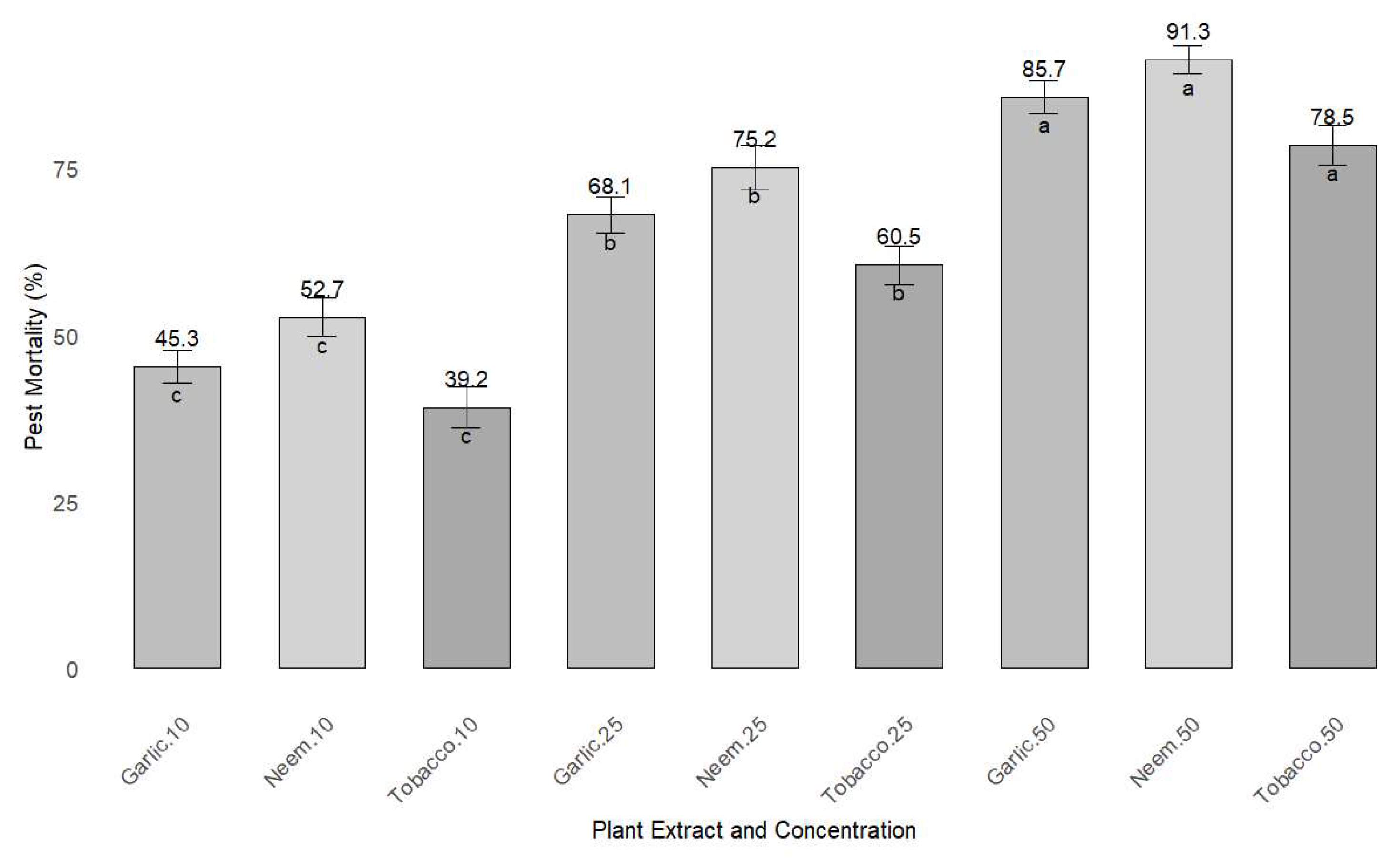

Our findings indicate that each agricultural system influenced the diversity and abundance of microbial communities, with significant differences in the pest species count across the systems. The organic farm in Kushtia had a moderate pest species count, while the conventional farm in Rajshahi exhibited the highest pest species count, likely due to the intensive use of chemical pesticides that may have disrupted the natural pest control mechanisms. The agroecological farm in Jhenaidah, with its integrated pest management strategies, demonstrated the lowest pest species count, suggesting that minimal pesticide use combined with natural farming techniques could be an effective approach to maintaining pest control without harming the environment. In terms of microbial diversity, the organic farm showed a higher diversity of bacterial communities compared to the other systems, which may be attributed to the absence of chemical pesticides and the rich, organic soil content. Conversely, the conventional farm, which relied heavily on chemical inputs, exhibited a lower microbial diversity, potentially due to the toxic effects of pesticides on beneficial microorganisms. The agroecological farm, which used a combination of organic and conventional practices, exhibited intermediate microbial diversity, indicating that a balanced approach could help maintain microbial health while ensuring pest control. The plant extract treatments, particularly neem, garlic, and tobacco, demonstrated promising results for pest control. Neem and garlic extracts showed the highest mortality rates in pests at the higher concentrations (50%), which aligns with previous studies indicating their pesticidal properties. Tobacco extract also showed moderate efficacy at higher concentrations. These results suggest that plant-based pesticides could be a viable alternative to chemical pesticides in sustainable farming systems, providing an eco-friendly and less toxic method for controlling pests.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of agricultural practices in shaping microbial diversity and pest dynamics. Organic and agroecological farming practices promote microbial diversity and sustainable pest control, while conventional farming may lead to reduced microbial diversity and increased pest pressure. The use of plant extracts such as neem, garlic, and tobacco offer an effective and environmentally friendly alternative for pest management, with neem and garlic extracts showing the highest efficacy at higher concentrations. Future research should focus on exploring the long-term impacts of these farming systems and plant-based pesticides on ecosystem health, including soil fertility, biodiversity, and resistance development in pests. Additionally, integrating these practices into broader agricultural systems could help address the challenges of sustainable food production while minimizing environmental harm.

References

- Çakmakçı, R. , Salık, M. A., & Çakmakçı, S. Assessment and principles of environmentally sustainable food and agriculture systems. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1073. [Google Scholar]

- Kabato, W.; Getnet, G.T.; Sinore, T.; Nemeth, A.; Molnár, Z. Towards climate-smart agriculture: Strategies for sustainable agricultural production, food security, and greenhouse gas reduction. Agronomy 2025, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Achal, V. A comprehensive review on environmental and human health impacts of chemical pesticide usage. Emerging Contaminants 2024, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonupara, T.; Udomkun, P.; Khan, E.; Kajitvichyanukul, P. Airborne pesticides from agricultural practices: A critical review of pathways, influencing factors, and human health implications. Toxics 2023, 11, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Arcot, Y.; Medina, R.F.; Bernal, J.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Akbulut, M.E. Integrated pest management: an update on the sustainability approach to crop protection. ACS omega 2024, 9, 41130–41147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souto, A.L.; Sylvestre, M.; Tölke, E.D.; Tavares, J.F.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Cebrián-Torrejón, G. Plant-derived pesticides as an alternative to pest management and sustainable agricultural production: Prospects, applications and challenges. Molecules 2021, 26, 4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milián-García, Y.; Pyne, C.; Lindsay, K.; Romero, A.; Hanner, R.H. Unveiling invasive insect threats to plant biodiversity: Leveraging eDNA metabarcoding and saturated salt trap solutions for biosurveillance. Plos one 2023, 18, e0290036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capurso, G.; Carroll, B.; Stewart, K.A. Transforming marine monitoring: Using eDNA metabarcoding to improve the monitoring of the Mediterranean Marine Protected Areas network. Marine Policy 2023, 156, 105807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, K., Blackman, R. C., Bourlat, S. J., Hellström, M., Bakker, J., Bista, I., ... & Deiner, K. (2021). A practical guide to DNA-based methods for biodiversity assessment. Pensoft Publishers.

- Sivakamavalli, J. (2022). Environment biomonitoring with eDNA—A new perspective to identify biodiversity. In New Paradigms in Environmental Biomonitoring Using Plants (pp. 109–164). Elsevier.

- Kestel, J. H., Field, D. L., Bateman, P. W., White, N. E., Allentoft, M. E., Hopkins, A. J., ...; Nevill, P. Applications of environmental DNA (eDNA) in agricultural systems: Current uses, limitations and future prospects. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 847, 157556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernaola, L.; Holt, J.R. Incorporating sustainable and technological approaches in pest management of invasive arthropod species. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 2021, 114, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro, C.; Jay-Robert, P.; Pétillon, J. eDNA for monitoring and conserving terrestrial arthropods: Insights from a systematic map and barcode repositories assessments. Insect conservation and diversity 2024, 17, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcenilla, C., Cobo-Díaz, J. F., De Filippis, F., Valentino, V., Cabrera Rubio, R., O’Neil, D., ...; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A. Improved sampling and DNA extraction procedures for microbiome analysis in food-processing environments. Nature Protocols 2024, 19, 1291–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Microbial diversity (measured as Operational Taxonomic Units, OTUs) across three agricultural practices: organic (Kushtia), agroecological (Jhenaidah), and conventional (Rajshahi). Bar heights represent the mean microbial diversity (OTUs) for soil, plant, and air samples, with error bars indicating standard deviations. Significance labels (a, b, c) above the bars indicate statistically significant differences between agricultural systems, as determined by ANOVA (p < 0.05). The figure highlights the impact of agricultural practices on microbial community structure across different sample types.

Figure 1.

Microbial diversity (measured as Operational Taxonomic Units, OTUs) across three agricultural practices: organic (Kushtia), agroecological (Jhenaidah), and conventional (Rajshahi). Bar heights represent the mean microbial diversity (OTUs) for soil, plant, and air samples, with error bars indicating standard deviations. Significance labels (a, b, c) above the bars indicate statistically significant differences between agricultural systems, as determined by ANOVA (p < 0.05). The figure highlights the impact of agricultural practices on microbial community structure across different sample types.

Figure 2.

Pest species diversity (count of identified pest species) across three agricultural practices: organic (Kushtia), agroecological (Jhenaidah), and conventional (Rajshahi). Bar heights represent the mean pest species count, with error bars indicating the standard deviation. Significance letters (a, b, c) indicate statistically significant differences between practices as determined by ANOVA (p < 0.05). Conventional farming exhibited the highest pest diversity, followed by organic and agroecological practices.

Figure 2.

Pest species diversity (count of identified pest species) across three agricultural practices: organic (Kushtia), agroecological (Jhenaidah), and conventional (Rajshahi). Bar heights represent the mean pest species count, with error bars indicating the standard deviation. Significance letters (a, b, c) indicate statistically significant differences between practices as determined by ANOVA (p < 0.05). Conventional farming exhibited the highest pest diversity, followed by organic and agroecological practices.

Figure 3.

Pest species diversity (mean ± standard deviation) across different agricultural practices. Organic farming in Kushtia showed a significantly higher pest diversity (7.5 ± 1.2, denoted 'a') compared to agroecological farming in Jhenaidah (5.2 ± 0.9, denoted 'b') and conventional farming in Rajshahi (9.3 ± 1.5, denoted 'c'). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Pest species diversity (mean ± standard deviation) across different agricultural practices. Organic farming in Kushtia showed a significantly higher pest diversity (7.5 ± 1.2, denoted 'a') compared to agroecological farming in Jhenaidah (5.2 ± 0.9, denoted 'b') and conventional farming in Rajshahi (9.3 ± 1.5, denoted 'c'). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Pest mortality rate (%) under different concentrations of plant extracts (Azadirachta indica - Neem, Allium sativum - Garlic, Nicotiana tabacum - Tobacco) against Helicoverpa armigera. Mortality was significantly higher at 50% concentration of Neem and Garlic extracts compared to lower concentrations and Tobacco extract. Different letters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences between treatments at p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Pest mortality rate (%) under different concentrations of plant extracts (Azadirachta indica - Neem, Allium sativum - Garlic, Nicotiana tabacum - Tobacco) against Helicoverpa armigera. Mortality was significantly higher at 50% concentration of Neem and Garlic extracts compared to lower concentrations and Tobacco extract. Different letters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences between treatments at p < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Pest mortality rates under different plant extract concentrations, with standard error bars. The values on top of the bars represent the mean mortality percentage, while the letters indicate statistical significance between treatments (a, b, c). The plot shows pest mortality rates for three plant extracts (neem, garlic, and tobacco) at concentrations of 10%, 25%, and 50%. Data are presented as mean ± SE, with statistical comparisons made using ANOVA.

Figure 5.

Pest mortality rates under different plant extract concentrations, with standard error bars. The values on top of the bars represent the mean mortality percentage, while the letters indicate statistical significance between treatments (a, b, c). The plot shows pest mortality rates for three plant extracts (neem, garlic, and tobacco) at concentrations of 10%, 25%, and 50%. Data are presented as mean ± SE, with statistical comparisons made using ANOVA.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).