1. Introduction

The increase in global environmental problems, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, and the depletion of natural resources, has intensified societal interest in promoting sustainable lifestyles and responsible behaviors to mitigate the effects of the ecological crisis. In this regard, environmental education serves as a fundamental tool to enhance pro-environmental behavior in its efforts to achieve environmental protection [

1]. Likewise, higher education plays a strategic role as an agent in shaping citizens capable of understanding, valuing, and acting responsibly in the face of contemporary environmental challenges [

2]. In this context, understanding the environmental attitudes and behaviors of university students has become a priority objective for designing educational strategies aimed at strengthening environmental awareness and promoting sustainable practices, especially in non-face-to-face modalities such as distance or online education.

Environmental attitudes constitute a set of learned beliefs, emotions, and dispositions that guide individuals’ behavior toward caring for the natural environment [

3,

4]. Various studies have shown that positive pro-environmental attitudes are essential for adopting sustainable behaviors [

4], although they do not always directly translate into concrete actions [

5,

6]. This dissonance between attitude and behavior has been widely analyzed through theoretical models such as the Theory of Planned Behavior, the Knowledge-Attitude-Practice Model, and the Capability-Motivation-Opportunity Model, which explain how internal and external factors interact to facilitate or limit the implementation of environmental values and beliefs [

7,

8].

Environmental behavior, on the other hand, is the external expression of attitude [

7]. It encompasses a wide range of actions aimed at minimizing negative impacts on the environment, such as energy saving, waste reduction, responsible consumption, and participation in environmental defense activities [

9]. These practices not only respond to personal convictions but are also conditioned by social, cultural, educational, and economic variables, highlighting the importance of analyzing the influence of factors such as age, gender, marital status, and academic major in shaping sustainable habits [

10,

11].

Various studies have shown that university students exhibit varying levels of environmental engagement depending on their social and educational context. For example, research conducted in countries such as Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico indicate that students pursuing degrees related to natural sciences tend to display stronger environmental attitudes and behaviors than those from other academic fields [

12,

13]. Similarly, [

14] found that sustainable consumption habits and waste management are strongly associated with the degree of environmental awareness promoted by educational institutions. These findings suggest that academic training and curriculum design are key determinants for strengthening environmental competencies in future professionals. However, the reality is more complex than it seems [

7]. The relationship between environmental knowledge and pro-environmental behavior has been controversial [

15,

16]), and may be influenced by various factors, such as motivational components in the form of personal attitude [

17]. Therefore, it is important to frequently study and monitor those factors that influence environmental behavior in educational segments where this topic has been little explored.

The distance education modality, which is increasingly widespread globally [

18], represents an additional challenge for promoting environmental attitudes and behaviors due to limited face-to-face interaction, the geographic and cultural diversity of students, and the particularities of virtual learning [

19]. However, studies such as [

20] indicate that, even in non-face-to-face contexts, it is possible to encourage pro-environmental attitudes through educational activities that promote critical reflection, indirect contact with nature, and the practical application of ecological knowledge. Therefore, it is important to first identify, from multiple dimensions, the environmental attitudes and behaviors in understudied student segments.

On the other hand, recent literature has emphasized the multidimensional analysis of environmental behaviors, considering not only individual factors but also the social and structural elements that condition their development [

21]. For instance, research by [

22] highlights the importance of environmental values, knowledge, and attitudes as significant predictors of sustainable behaviors. Similarly, [

23] points out that perceived behavioral control, understood as the perception of one’s ability to act, mediates the relationship between attitudes and environmental intentions, highlighting the need to strengthen not only knowledge but also students’ self-confidence and practical skills.

In this framework, studies such as that of [

24] show that environmental intention is a key link between attitude and behavior, making it essential for educational strategies to promote not only knowing but also the desire and ability to act environmentally. Additionally, research by [

25] underscores the positive impact of formal environmental education in improving attitudes and sustainable behaviors, supporting the relevance of incorporating these approaches in university programs, including those offered in distance learning modalities.

Considering this context, the present study is justified by the need to explore, analyze, and understand the environmental attitudes and behaviors of university students enrolled in distance education programs in Ecuador—a population segment that remains underexplored in the literature despite its increasing relevance. Addressing this gap is important, given the limited availability of data regarding beliefs and values on environmental factors and climate change in the Latin American population [

26]. Additionally, this research seeks to identify distinct environmental profiles within this population and determine the influence of sociodemographic variables on their environmental commitment. The aim is to provide valuable insights to inform the design of differentiated educational strategies, thereby enhancing environmental competencies tailored to the specific characteristics and needs of each student group.

In summary, this study addresses the environmental phenomenon from a multivariable approach, integrating descriptive and multivariate statistical analyses that allow understanding not only the levels of environmental attitudes and behaviors but also the interrelationships between dimensions, the existence of differentiated profiles, and the impact of sociodemographic factors. Thus, it contributes to the advancement of scientific knowledge about university environmental behavior and offers useful tools for the development of educational programs that promote active, critical, and transformative environmental citizenship.

Research Objective and Questions

The primary objective of this study is to analyze the environmental attitudes and behaviors of distance education university students in Ecuador, identifying differences between dimensions, environmental profiles, and the influence of sociodemographic variables to guide educational strategies that strengthen students’ environmental engagement. Furthermore, the following research questions are addressed:

What are the predominant environmental attitudes and behaviors among distance education university students in Ecuador?

Are there significant differences between the various dimensions that shape environmental attitudes and behaviors?

What relationships exist between the dimensions of environmental attitudes and behaviors, and what environmental profiles can be identified among students?

Which sociodemographic variables significantly influence the environmental attitudes and behaviors of university students?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Study

This study follows a non-experimental, quantitative, descriptive, and explanatory design. A cross-sectional design was used to collect data at a single point in time, aiming to characterize the environmental attitudes and behaviors of distance education university students, analyze the relationships between these dimensions, and determine the influence of sociodemographic variables. Through the application of multivariable statistical techniques, this study sought not only to describe the levels of environmental commitment but also to identify patterns, profiles, and associated factors that contribute to explaining the diversity of environmental perceptions and practices among the student population.

2.2. Participants

The sample consisted of 405 distance education students from the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL), Ecuador. Of the total participants, 38% were male and 62% female, with ages ranging from 19 to 33 years, where the age group 19 to 25 years represented 35% of the sample. Regarding marital status, 64% identified as single, while the remaining percentage reported being married, in a free union, divorced, or separated. Academically, the students belonged to three major fields: Social Sciences, Education, and Humanities (31%), Economic and Business Sciences (26%), and Natural and Exact Sciences (43%). The sample size was determined based on practical limitations in data collection rather than predefined criteria [

27]. However, a typical sample size for a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error is approximately 384 participants. With 405 participants, the sample remains within an acceptable range for social research studies.

2.3. Instrument for Data Collection

A structured online questionnaire was applied, based on the validated instrument used by [

3,

28] to assess pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in university contexts. The instrument was divided into two main sections:

- a)

Sociodemographic data: Including age, sex, marital status, and academic discipline.

- b)

Environmental dimensions: Evaluated through 19 items on environmental attitudes and 16 items on environmental behaviors, distributed across the following dimensions:

Environmental attitudes:

Environmental Apathy (APA – 4 items); Reflects the level of disinterest or indifference toward environmental issues and the lack of engagement in their resolution.

Anthropocentrism (ANT – 5 items): Evaluates the perception of the environment based on human benefits, prioritizing human well-being over ecological conservation.

Connectedness (CON – 5 items): Assesses the degree to which individuals feel part of nature and emotionally connected with animals, plants, and ecosystems.

Emotional Affinity (EMO – 5 items): Measures the intensity of the emotional bond with nature, where environmental contact influences well-being, happiness, and stress reduction.

Environmental behaviors:

Energy Efficiency and Resource Management (ENE – 4 items): Refers to daily actions aimed at conserving water, energy, and promoting sustainable mobility, such as walking or using public transportation.

Waste Management (GRE – 5 items): Involves behaviors related to waste separation, reuse, and proper disposal of household and hazardous waste.

Ecological Consumption (ECO – 4 items): Evaluates the preference for sustainable, recyclable, and minimally packaged products, along with responsible consumption practices.

Activism (ACT – 3 items): Reflects active participation in initiatives, organizations, or movements that promote environmental protection and improvement [

3].

Responses were rated on a three-point ordinal scale: 1 = Never, 2 = Sometimes, and 3 = Almost Always [

2]. The instrument’s reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, obtaining an overall score of α = 0.82, which is considered acceptable since it exceeds the threshold of 0.7

2.4. Data Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using R software [

29], applying descriptive and multivariate techniques to characterize environmental attitudes and behaviors and evaluating the influence of sociodemographic factors.

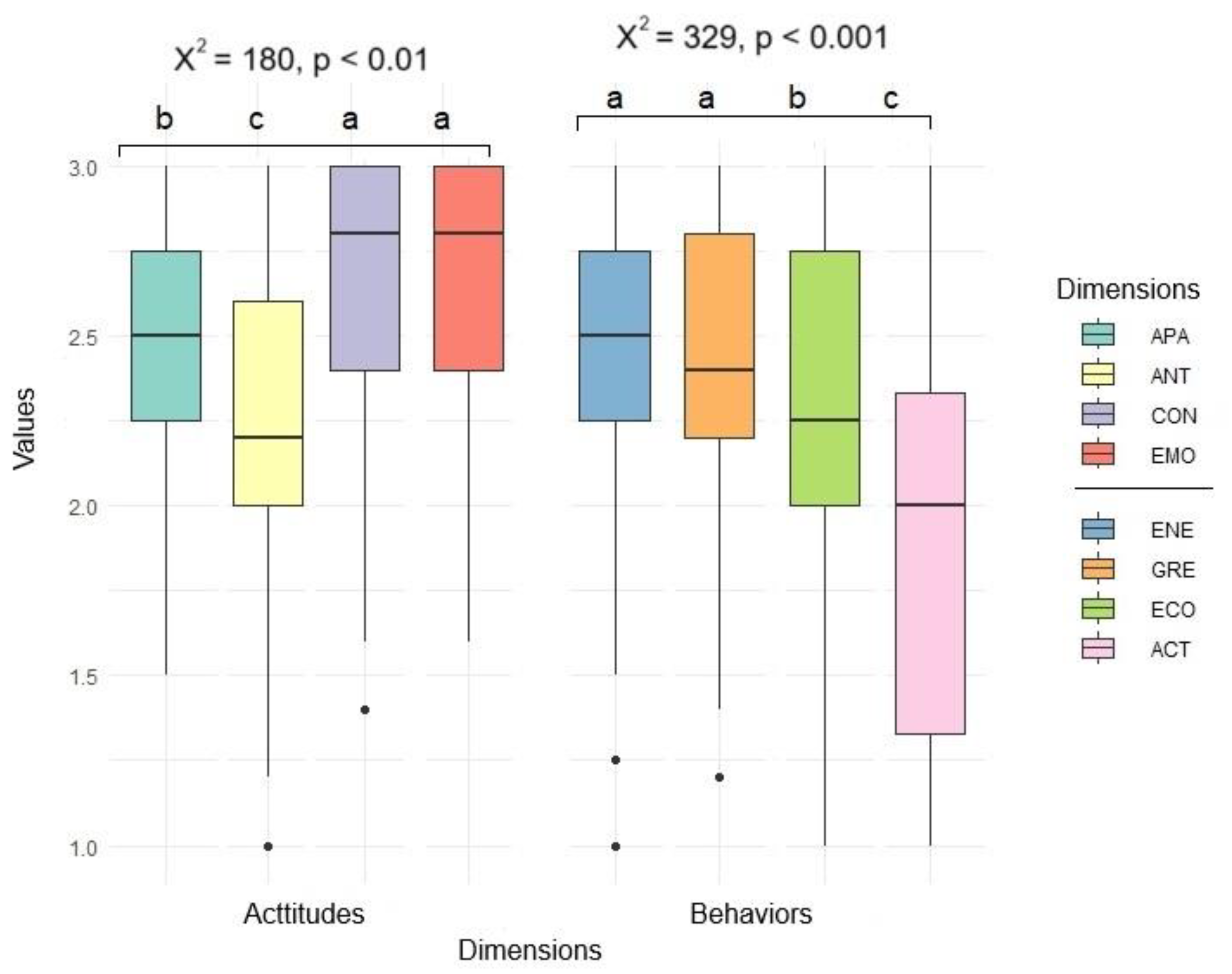

Descriptive Analysis: Descriptive statistics were used to identify general trends within the sample, focusing on the dimensions of environmental attitudes and behaviors. Boxplots were generated to visualize the distribution and dispersion of each dimension and highlight potential differences.

Comparison between Dimensions: To determine whether significant differences existed between the dimensions of attitudes and behaviors, the Friedman test was applied, which is appropriate for ordinal data and related groups. Upon obtaining significant results, a post hoc analysis was performed using Wilcoxon paired tests with Bonferroni adjustment to identify specific differences between pairs of dimensions.

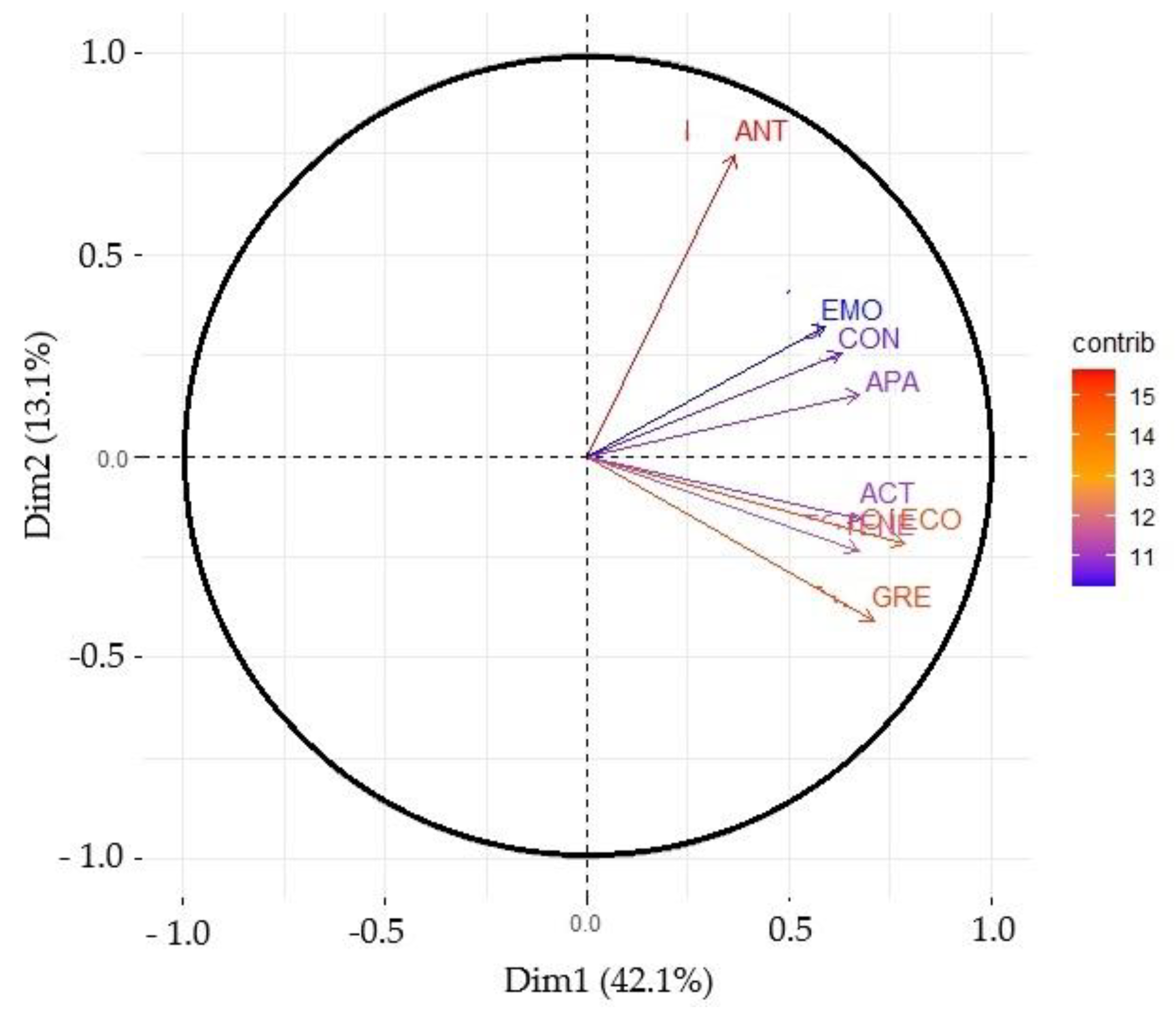

Principal Component Analysis (PCA): A PCA was conducted to explore the structural relationships between the eight environmental dimensions and identify natural groupings among pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. This analysis allowed for the visualization of how dimensions associate and contribute to the total variability in the model.

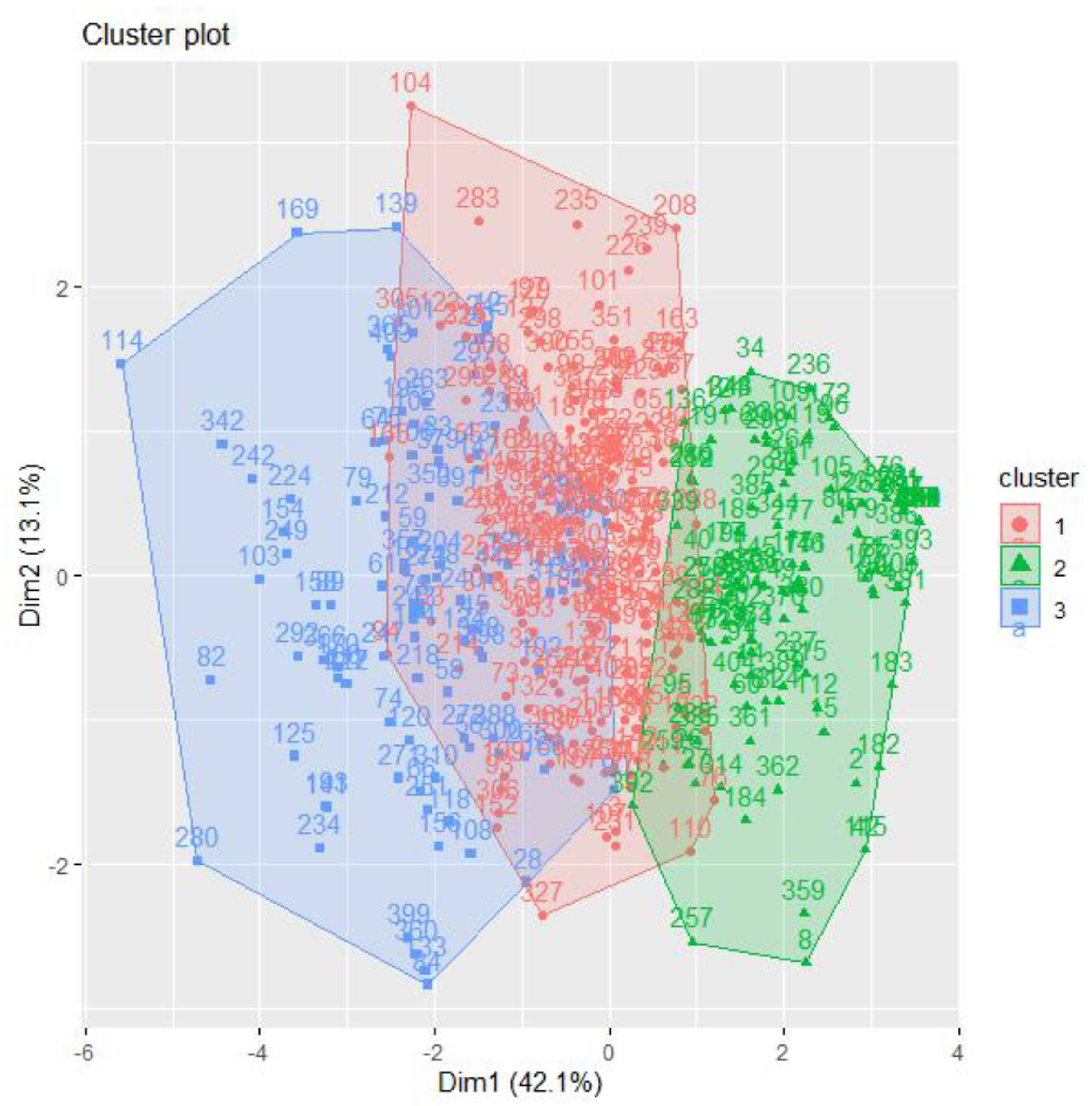

Cluster Analysis (K-means): To identify environmental profiles within the student population, a cluster analysis using the K-means algorithm was performed. This procedure grouped students based on their scores across environmental dimensions, generating profiles that reflect different levels of environmental commitment.

Multivariable Analysis of Sociodemographic Influence:

PERMANOVA (Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance): To evaluate whether sociodemographic variables significantly influenced environmental attitudes and behaviors, a PERMANOVA was applied, given its robustness in analyzing multivariate differences in non-parametric data. A global model was initially applied with all sociodemographic variables, followed by individual models to identify which variables had the most explanatory power.

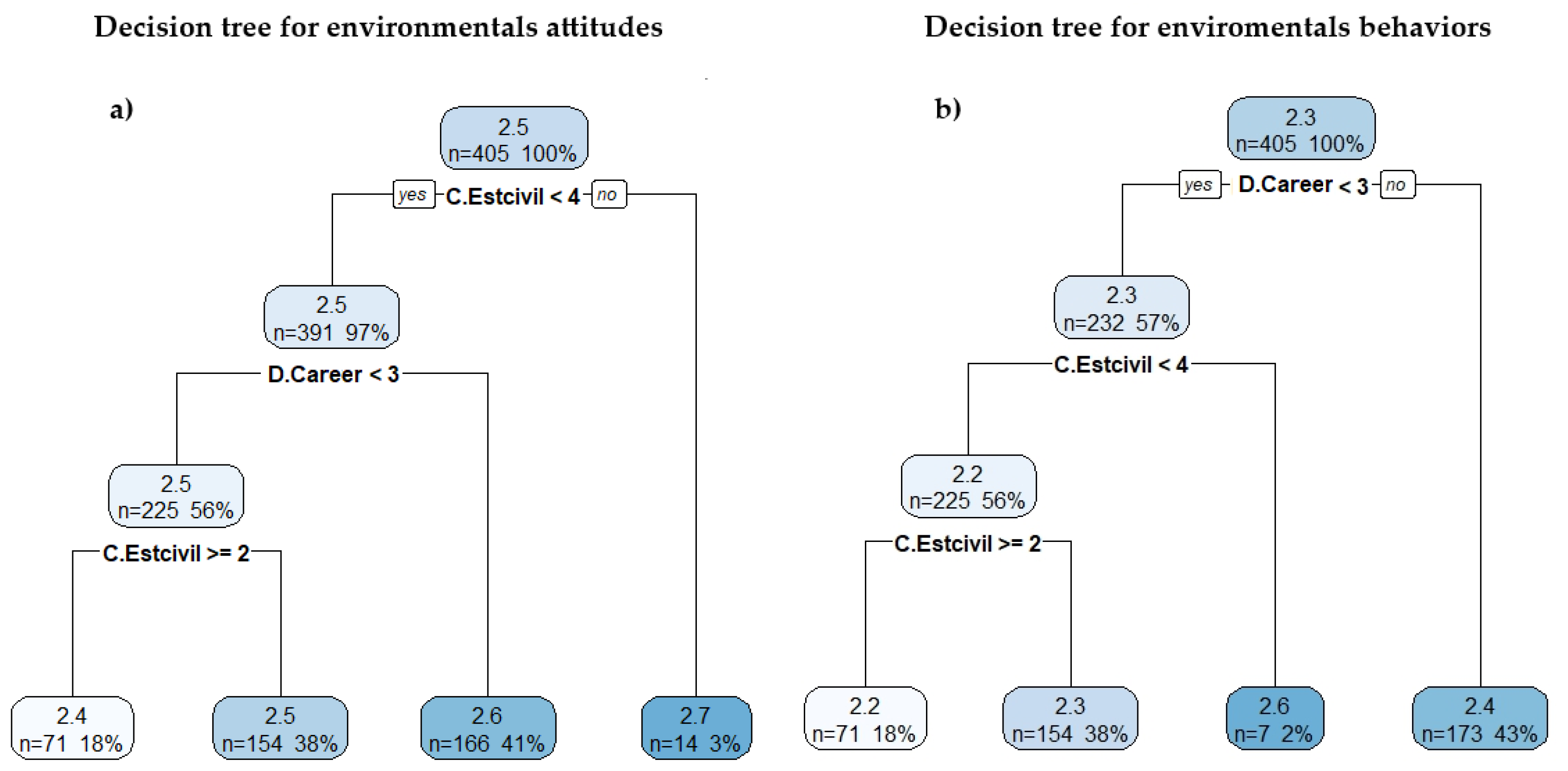

Decision Trees (CART – Classification and Regression Trees): To identify and hierarchically visualize which sociodemographic variables had the most discriminative power on environmental attitudes and behaviors, decision trees were generated. This technique produced interpretive models that reflect the combinations of sociodemographic characteristics associated with higher or lower levels of environmental commitment.

These multivariate analyses provided a comprehensive understanding of the relationships between environmental dimensions, sociodemographic factors, and identified profiles, allowing for the design of targeted educational strategies to strengthen environmental engagement in the university context.

4. Discussion

This study analyzed the environmental attitudes and behaviors of distance-education university students in Ecuador, identifying differences among dimensions, environmental profiles, and the influence of sociodemographic factors. These findings are particularly relevant given that higher education plays a crucial role in shaping environmentally responsible citizens [

3].

First, descriptive results revealed that the dimensions most highly valued by students were Connectivity with Nature and Emotional Affinity, indicating a strong affective connection to the natural environment. This trend suggests students perceive nature not as an external element but as an integral part of their existence, reflected in statements such as "I feel part of nature" or "I need to spend time in nature to be happy." This finding has significant implications, as several studies demonstrate that emotional connections to nature serve as critical antecedents for developing positive pro-environmental attitudes [

20]. However, such emotional connections do not always translate into concrete actions [

33], as evidenced by the low scores in Environmental Activism observed in this study. This gap between sentiment and action aligns with [

5], who argue that translating attitudes into behaviors depends on factors like perceived costs, anticipated benefits, and personal self-regulation. Thus, while students’ emotional identification with nature is encouraging, environmental education programs must enhance self-efficacy, awareness of environmental impacts, and opportunities for practical action, particularly in regions where biodiversity faces constant threats.

The differences found between environmental attitudes and behaviors suggest that university students prioritize certain aspects of their relationship with the natural environment, showing greater inclination towards positive emotional and cognitive attitudes but less involvement in collective actions demanding higher effort, such as environmental activism. This pattern concurs with findings by [

25], highlighting that although environmental education strengthens positive attitudes toward the environment, the transition to sustainable behaviors significantly depends on additional contextual and motivational factors.

In this regard, Principal Component Analysis revealed a clear relational structure between affective and cognitive dimensions (Connectivity and Emotional Affinity) and certain everyday behaviors, notably waste management and ecological consumption. This indicates students maintain coherence between their feelings, thoughts, and environmental actions, although limited primarily to low-effort individual activities. This result aligns with [

22], who argue environmental values and knowledge significantly influence pro-environmental behaviors, predominantly those requiring minimal effort, resources, and time, whereas more demanding actions like activism remain less common due to their higher social and personal costs.

Cluster analysis identified three distinct environmental profiles: highly committed, moderately committed, and low commitment students, with the majority displaying a moderate profile characterized by intermediate attitudes and behaviors. This typology matches findings by [

12], who identified similar profiles among Cuban university students, noting a medium level of environmental identity. Likewise, [

14] and [

13] confirm heterogeneous environmental profiles among university students, emphasizing that environmental commitment varies based on academic area and cultural context. Furthermore, prior research confirms that personal and social factors like individual motivation, perceived efficacy, and environmental participation opportunities significantly explain these profile differences [

6,

8]. These insights underscore the importance of accurately characterizing commitment levels to design targeted and effective educational strategies tailored to each identified profile, particularly relevant in distance education contexts with unique educational and environmental challenges [

19,

25].

Regarding the influence of sociodemographic variables on environmental attitudes and behaviors, academic major emerged as the most significant factor, influencing both attitudes and behaviors. This finding aligns with [

13], who highlight the significant impact of academic specialization on environmental knowledge levels and effective pro-environmental behavior adoption. This study confirmed that students from natural sciences programs exhibited higher levels of environmental practices, supporting the argument by [

30] and [

31] that specialized knowledge about natural resources and environmental issues increases the likelihood of positive attitudes towards environmental conservation. This aspect gains particular relevance given the distance education context, where environmental knowledge acquisition differs markedly from traditional in-person education.

While the positive relationship between environmental knowledge and pro-environmental behavior is widely supported [

11], evidence also suggests this relationship is not always linear or direct [

32]. This indicates that while specialized knowledge influences pro-environmental attitudes and sustainable practices, other factors such as individual motivation, perceived barriers, and actual opportunities for environmental action must be considered [

7,

33].

Additionally, results revealed a significant but less explanatory influence of age on environmental attitudes and marital status on environmental behaviors. These findings expand understanding of how personal and familial responsibilities may influence specific environmental practices, an area less explored in prior studies. [

8] argue that personal variables such as age and life stage (reflected in marital status) could modify individual priorities regarding environmental participation, leading to varying commitment and action levels based on personal circumstances.

Conversely, gender showed no significant differences in this study, contrasting with previous international research typically indicating higher environmental concern among women compared to men [

34,

35,

36]. This discrepancy may partially stem from the unique educational and cultural context of this study, involving distance-learning students with different sociodemographic and academic profiles than those reported elsewhere. [

35] identified gender-based differences in climate change perceptions among Mexican education students, likely influenced by traditional social roles. Similarly, [

36] noted heightened emotional responses to environmental threats among women. [

34] also observed significant gender mediation in economic perspectives and environmental concern. [

26] further suggest gender significantly shapes climate change perceptions across Latin America. The absence of gender differences in our study suggests that the distance education modality and predominantly female sample might have homogenized environmental perceptions and attitudes, reducing traditional gender disparities.

Decision trees confirmed marital status significantly influenced environmental attitudes, while academic major primarily influenced behaviors, possibly due to family and work responsibilities impacting environmental perceptions and actions. Akhtar et al. [

8] argue that personal context-related motivation and opportunities are crucial in activating sustainable behaviors.

Likewise, the role of social and cultural context is also determinant. For instance, [

19] suggests that informational incentives and the way environmental messages are communicated significantly influence the adoption of pro-environmental practices. This could explain why, despite students demonstrating positive attitudes, their actual behaviors do not reach the same levels, particularly in dimensions such as activism, which demand higher social and collective mobilization.

Regarding sustainable consumption, [

24] emphasizes the importance of attitudes and their conversion into intention and actual behavior. This underscores the need for educational strategies to focus not only on knowledge transmission but also on strengthening motivation and the capacity for action, as illustrated by [

37] in their analysis of consumers’ environmentally responsible behavior.

Moreover, international studies such as those conducted by [

14] in Budapest, and [

6] in multicultural contexts, consistently highlight that environmental attitude, while generally positive, require the development of specific competencies and a favorable environment to translate into concrete actions. This is particularly relevant in distance education modalities, where direct interaction and practical experiences are inherently limited.

Finally, it is important to note that the findings of this study are aligned with [

38], who, through a bibliometric analysis, concluded that research on environmental behavior has evolved towards multidimensional approaches integrating personal, social, and academic factors, as implemented in this study through a combination of descriptive, multivariate, and predictive analyses.

Overall, results highlight a solid foundation of pro-environmental attitudes among distance-learning university students underline the need to strengthen mechanisms to convert these attitudes into sustainable, collective behaviors, considering the critical role of sociodemographic variables and academic context. Universities thus emerge as pivotal agents of sustainability change, preparing professionals to influence their environment through knowledge, values, and attitudes [

39]. Hence, targeted educational strategies are recommended for the identified environmental profiles, enhancing commitment areas like activism and aligning with students’ personal and academic characteristics.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the environmental attitudes and behaviors of distance learning university students in Ecuador, providing empirical evidence about their characteristics, differences, relationships, and associated sociodemographic factors. The main conclusions, organized according to the research questions, are presented below:

5.1. Predominant Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors

The comprehensive analysis of environmental attitudes and behaviors indicates that university students exhibit a positive evaluation of the environment, with the highest scores recorded in the Connectedness with Nature (CON) and Emotional Affinity (EMO) dimensions. These findings suggest that students maintain a strong emotional relationship with nature and a favorable perception of its care and protection. However, this emotional commitment does not always translate into real active behaviors, as the Environmental Activism (ACT) dimension obtained the lowest scores, indicating lower participation in collective environmental actions. Regarding daily environmental behaviors, relatively high levels were observed in Energy Efficiency (ENE) and Waste Management (GRE). Nevertheless, the results show that, despite environmental awareness, there is still a significant gap between attitude and environmental practice, an aspect that should be considered in the formulation of educational and awareness strategies for this type of population.

5.2. Significant Differences Between Dimensions of Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors

The significant differences found between the dimensions of environmental attitudes and behaviors confirm that not all dimensions are perceived and practiced equally by the students. Dimensions associated with daily and low-effort habits, such as waste management and energy efficiency, are more frequently practiced than those requiring greater social or collective involvement, such as environmental activism. This finding reinforces the need to promote actions from higher education that are oriented toward citizen and community engagement, going beyond individual and everyday practices to encourage active participation in broader socio-environmental issues.

5.3. Relationships Between Dimensions and Identified Environmental Profiles

The PCA revealed that the environmental dimensions are structured into differentiated groupings, where pro-environmental attitudes are primarily related to individual, low-effort behaviors, but not with collective actions such as activism. Based on the cluster analysis, three environmental profiles were identified: a) Highly committed students: Demonstrating the highest levels of environmental attitudes and behaviors. B) Moderately committed students: With intermediate levels of environmental engagement, representing the most prevalent profile. C) Low-commitment students: Characterized by lower levels of environmental awareness and action.

The moderate commitment profile was the most representative, suggesting that the student population is not homogeneous in terms of their environmental awareness and practices. This highlights the importance of designing differentiated educational strategies according to the level of commitment detected, focusing on enhancing areas with lower engagement and fostering active participation in environmental issues.

5.4. Influence of Sociodemographic Variables

The multivariable analysis confirmed that sociodemographic variables influence the configuration of environmental attitudes and behaviors. Academic discipline was the most influential factor, indicating that students from natural and environmental sciences disciplines demonstrated higher levels of environmental commitment compared to those from social sciences and economics. Marital status also showed significant effects, suggesting that personal responsibilities may influence the adoption of certain environmental practices. On the other hand, age showed a moderate relationship with environmental attitudes, while gender did not have a significant impact.

Overall, it can be concluded that, although distance learning students exhibit favorable attitudes toward the environment, a gap persists between recognizing the problem and taking effective action to address it. The segmentation into environmental profiles and the influence of sociodemographic factors highlight the need to implement differentiated educational strategies adapted to the various levels of environmental commitment and the academic context of the students. Finally, future research should delve into the impact of additional contextual variables, such as previous environmental education experiences and the sociocultural environment of the students, to further enhance the understanding of the factors influencing pro-environmental behavior in higher education.

6. Limitations of the Study

Among the primary limitations of this study is that the research was conducted ex-clusively with distance-learning university students from a single higher education institution in Ecuador. Although this approach provides valuable and representative insights within this specific context, it highlights the necessity of expanding future analyses to include face-to-face students and those from other universities. Such expansion would strengthen the generalizability of results and enrich comparisons across different educational settings.

Additionally, data were collected through a self-administered questionnaire, implying that responses were based on participants’ perceptions and honesty without direct verification of the reported environmental behaviors. Despite this limitation, the instrument used has demonstrated validity and reliability in previous studies, enabling the acquisition of robust results consistent with international literature.

Another possible limitation is that the measurement of environmental attitudes and behaviors employed a three-point ordinal scale, which simplified the variability of responses. However, this methodological choice facilitated participants’ comprehension of the instrument and promoted higher engagement and response rates, ensuring the completeness and consistency of the data.

Similarly, while the analysis focused on basic sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, marital status, and academic discipline, future research could include additional contextual, cultural, and economic factors that might also significantly influence environmental perceptions and actions. Nevertheless, the inclusion of these basic variables allowed for the identification of relevant and differentiating patterns within the studied sample, generating valuable insights for an initial understanding of the phenomenon.

Finally, although the cross-sectional study design enabled an accurate diagnostic assessment of environmental attitudes and behaviors at a specific moment, longitudinal studies could provide complementary information regarding the evolution of these dimensions over time. Nonetheless, the results obtained here constitute a solid and updated foundation for future research and the development of educational strategies aimed at strengthening environmental commitment in distance higher education contexts.

7. Future Perspectives

The results obtained in this study open multiple avenues for further research and action within higher environmental education, particularly in Latin American countries characterized by high biodiversity but simultaneously facing increasing environmental threats due to climate change, ecosystem degradation, and unsustainable consumption patterns. In this context, it is essential that universities, as agents of social transformation, deepen their analysis of students’ environmental commitment—not only from an individual perspective but also by considering the sociocultural, economic, and ecological contexts in which students develop.

Future studies should expand this research to other educational institutions and modalities, incorporating complementary variables such as environmental knowledge levels, access to natural spaces, prior experiences with ecological activities, and the role of digital media in shaping environmental awareness. Additionally, conducting longitudinal studies would be valuable to observe changes in environmental attitudes and behaviors over time and to assess the impact of specific educational interventions.

Particularly in Latin America, which hosts a significant portion of the world’s biodiversity and is one of the regions most vulnerable to climate change impacts [

40], it is strategic to promote research aimed at understanding how environmental perceptions can translate into concrete conservation actions. It is crucial to closely integrate curricular content with each country’s ecological reality, fostering community engagement projects, sustainable entrepreneurship, and student leadership that contribute to environmental stewardship. Thus, environmental education can become a transformative tool, tailored to local needs and capable of driving lasting change in both individual and collective practices.