Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

. These moduli appear as massless scalar fields in the effective four-dimensional theory and correspond to deformations of the CY manifold's size (Kähler moduli,

. These moduli appear as massless scalar fields in the effective four-dimensional theory and correspond to deformations of the CY manifold's size (Kähler moduli,  ), shape (complex structure moduli,

), shape (complex structure moduli,  ), and the value of the string coupling constant (encoded in the axio-dilaton,

), and the value of the string coupling constant (encoded in the axio-dilaton,  ).

). , for the moduli fields (Giddings, Kachru and Polchinski, 2002; Kachru et al., 2003; Balasubramanian et al., 2005). This potential, derived within the framework of four-dimensional N=1 supergravity, can potentially stabilize all moduli at specific values, giving them masses and fixing the parameters of the effective theory. The seminal work by Gukov, Vafa and Witten (2000) provided the structure of the flux-induced superpotential, W, while frameworks like KKLT (Kachru et al., 2003) and the Large Volume Scenario (LVS) (Balasubramanian et al., 2005; Conlon, Quevedo and Suruliz, 2005) demonstrated explicit (though often fine-tuned) mechanisms for achieving stabilization, typically resulting in metastable de Sitter or stable Minkowski/AdS vacua.

, for the moduli fields (Giddings, Kachru and Polchinski, 2002; Kachru et al., 2003; Balasubramanian et al., 2005). This potential, derived within the framework of four-dimensional N=1 supergravity, can potentially stabilize all moduli at specific values, giving them masses and fixing the parameters of the effective theory. The seminal work by Gukov, Vafa and Witten (2000) provided the structure of the flux-induced superpotential, W, while frameworks like KKLT (Kachru et al., 2003) and the Large Volume Scenario (LVS) (Balasubramanian et al., 2005; Conlon, Quevedo and Suruliz, 2005) demonstrated explicit (though often fine-tuned) mechanisms for achieving stabilization, typically resulting in metastable de Sitter or stable Minkowski/AdS vacua. , particularly in the early universe.

, particularly in the early universe. . They exhibit strong nonlinearities and couplings between different moduli fields. Such features are well-known prerequisites for complex dynamical behavior, including chaos, in many areas of physics and mathematics (Strogatz, 2015). The possibility that moduli dynamics could be chaotic raises profound questions about the predictability of string theory, the ability to dynamically reach and persist within stable vacuum configurations, and the likelihood of achieving a cosmological evolution consistent with observations. This paper investigates the implications of chaotic dynamics for the cosmological viability of string compactifications.

. They exhibit strong nonlinearities and couplings between different moduli fields. Such features are well-known prerequisites for complex dynamical behavior, including chaos, in many areas of physics and mathematics (Strogatz, 2015). The possibility that moduli dynamics could be chaotic raises profound questions about the predictability of string theory, the ability to dynamically reach and persist within stable vacuum configurations, and the likelihood of achieving a cosmological evolution consistent with observations. This paper investigates the implications of chaotic dynamics for the cosmological viability of string compactifications.Literature Review

Moduli Stabilization Mechanisms

that depends on the complex structure moduli (

that depends on the complex structure moduli ( ) and the axio-dilaton (

) and the axio-dilaton ( ), potentially stabilizing them. Their work laid the foundation for constructing vacua with broken supersymmetry and stabilized moduli, utilizing the superpotential structure identified by Gukov, Vafa and Witten (2000).

), potentially stabilizing them. Their work laid the foundation for constructing vacua with broken supersymmetry and stabilized moduli, utilizing the superpotential structure identified by Gukov, Vafa and Witten (2000). ). Addressing this required incorporating non-perturbative effects. The KKLT scenario (Kachru et al., 2003) proposed using Euclidean D3-brane instantons or gaugino condensation on D7-branes to generate non-perturbative contributions to the superpotential,

). Addressing this required incorporating non-perturbative effects. The KKLT scenario (Kachru et al., 2003) proposed using Euclidean D3-brane instantons or gaugino condensation on D7-branes to generate non-perturbative contributions to the superpotential,  . This, combined with the flux potential and an uplifting mechanism (e.g., anti-D3-branes), could stabilize all moduli in a metastable de Sitter vacuum. An alternative approach, the Large Volume Scenario (LVS) (Balasubramanian et al., 2005; Conlon, Quevedo and Suruliz, 2005), utilizes a combination of fluxes, leading-order α' corrections to the Kähler potential

. This, combined with the flux potential and an uplifting mechanism (e.g., anti-D3-branes), could stabilize all moduli in a metastable de Sitter vacuum. An alternative approach, the Large Volume Scenario (LVS) (Balasubramanian et al., 2005; Conlon, Quevedo and Suruliz, 2005), utilizes a combination of fluxes, leading-order α' corrections to the Kähler potential  , and non-perturbative effects to stabilize Kähler moduli at exponentially large volumes, naturally generating a hierarchy between the Planck scale and the supersymmetry breaking scale. These scenarios demonstrated the existence of mechanisms for full moduli stabilization within string theory.

, and non-perturbative effects to stabilize Kähler moduli at exponentially large volumes, naturally generating a hierarchy between the Planck scale and the supersymmetry breaking scale. These scenarios demonstrated the existence of mechanisms for full moduli stabilization within string theory.The String Landscape and Statistical Approaches

, rather than the dynamics governing how these minima might be reached.

, rather than the dynamics governing how these minima might be reached.Cosmological Dynamics of Moduli

- Initial Conditions: Where do moduli fields start in the early universe? Random initial conditions might lead to overshoot problems, where fields roll past desirable minima (Brustein and Steinhardt, 1993). Addressing the initial conditions problem remains a significant challenge.

- Inflationary Dynamics: If moduli fields play the role of the inflaton or are coupled to it, their dynamics are crucial for the success of inflation. Multi-field inflation models derived from string theory often exhibit complex trajectory behaviour in field space (e.g., Dias, Frazer and Liddle, 2012; Marsh et al., 2013; Bachlechner et al., 2017), which can affect predictions for cosmological observables.

- Post-Inflationary Evolution: After inflation, moduli fields typically oscillate around their potential minima, potentially dominating the energy density and leading to cosmological problems (the "cosmological moduli problem") unless they decay sufficiently early (Banks, Kaplan and Nelson, 1994; de Carlos et al., 1993).

is critically important. The complexity of the potential

is critically important. The complexity of the potential  suggests that this path could be highly non-trivial.

suggests that this path could be highly non-trivial.Chaos in Dynamical Systems

). Chaos arises generically in systems with sufficient nonlinearity, coupling, and dimensionality. Tools like phase space analysis, Poincaré sections, bifurcation diagrams, and Lyapunov exponent calculations are standard methods for detecting and characterizing chaos.

). Chaos arises generically in systems with sufficient nonlinearity, coupling, and dimensionality. Tools like phase space analysis, Poincaré sections, bifurcation diagrams, and Lyapunov exponent calculations are standard methods for detecting and characterizing chaos.Studies Suggesting Complex Dynamics in String Theory

- Numerical Simulations: Studies of specific inflationary models derived from string theory, particularly multi-field models like N-flation (Dimopoulos et al., 2008) or axion monodromy inflation (Silverstein and Westphal, 2008; McAllister, Silverstein and Westphal, 2010), often reveal complex dynamics and sensitivity to initial conditions, although not always explicitly framed as chaos (e.g., Underwood, 2011; Sumitomo and Tye, 2012).

- Random Potentials: Some works model the string landscape using random potentials. Analyses of particle motion in such random potentials often exhibit features associated with chaotic dynamics or diffusion (Aazami and Easther, 2006; Marsh et al., 2013).

- Fractal Basin Boundaries: In systems with multiple attractors (minima), the boundaries between their basins of attraction can be fractal, a common indicator of underlying chaotic dynamics (Grebogi, Ott and Yorke, 1983). This possibility has been explored in landscape contexts, where trajectories starting near such boundaries exhibit extreme sensitivity (McDonald and Vilenkin, 2018).

- Explicit Calculations in Simplified Models: Investigations of simplified toy models capturing features of string potentials, such as coupled fields with exponential terms (common in supergravity), sometimes demonstrate chaotic regimes for certain parameter ranges (e.g., Copeland, Liddle and Lyth, 1998, although pre-dating modern landscape studies).

Identified Gap

in string compactifications and highlights the crucial role of moduli dynamics in cosmology. Studies often reveal complex behavior and sensitivity in specific models or statistical ensembles. However, there is often a gap between observing complexity in simulations and demonstrating chaos according to its mathematical definition (positive Lyapunov exponents, mixing) for realistic potentials derived from supergravity. Furthermore, a systematic analysis connecting the formal definition of chaos directly to the phenomenological requirements of a viable cosmology (stable constants, predictable inflation) is needed. This paper aims to bridge this gap by focusing on the implications of SDIC, arguing that its presence is fundamentally incompatible with observed cosmological stability, irrespective of whether generic string dynamics are proven chaotic in full mathematical detail.

in string compactifications and highlights the crucial role of moduli dynamics in cosmology. Studies often reveal complex behavior and sensitivity in specific models or statistical ensembles. However, there is often a gap between observing complexity in simulations and demonstrating chaos according to its mathematical definition (positive Lyapunov exponents, mixing) for realistic potentials derived from supergravity. Furthermore, a systematic analysis connecting the formal definition of chaos directly to the phenomenological requirements of a viable cosmology (stable constants, predictable inflation) is needed. This paper aims to bridge this gap by focusing on the implications of SDIC, arguing that its presence is fundamentally incompatible with observed cosmological stability, irrespective of whether generic string dynamics are proven chaotic in full mathematical detail.Research Questions

- Mathematical Structure: What are the demonstrable mathematical properties (dimensionality, nonlinearity, coupling, parameter dependence) of the dynamical system governing the evolution of moduli fields (

) derived from Type IIB flux compactifications, as established in the literature, and how do these properties relate to the known prerequisites for chaotic behaviour?

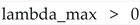

) derived from Type IIB flux compactifications, as established in the literature, and how do these properties relate to the known prerequisites for chaotic behaviour? - Definition and Implications of Chaos: What is the precise mathematical definition of dynamical chaos relevant to this system, with a specific focus on Sensitive Dependence on Initial Conditions (SDIC) as characterized by positive maximal Lyapunov exponents (

)? Crucially, what are the direct and unavoidable mathematical consequences of SDIC regarding the predictability and stability of trajectories within such a system?

)? Crucially, what are the direct and unavoidable mathematical consequences of SDIC regarding the predictability and stability of trajectories within such a system? -

Cosmological Viability: How do the mathematical consequences of chaotic moduli dynamics (specifically, the exponential divergence of trajectories implied by SDIC) compare with the observational requirements for a viable cosmological model describing our universe? In particular, how does SDIC conflict with:

- ◦

- The need for reliable stabilization of moduli to ensure time-independent fundamental constants?

- ◦

- The required predictability of cosmological epochs like inflation and reheating?

- Constraint on Viable Vacua: Does the potential incompatibility imply that any string vacuum state (defined by a specific

choice and corresponding potential

choice and corresponding potential  ) that aims to describe our observed universe must necessarily exhibit non-chaotic dynamics (

) that aims to describe our observed universe must necessarily exhibit non-chaotic dynamics ( ) in the relevant regions of moduli space and during the relevant cosmological eras?

) in the relevant regions of moduli space and during the relevant cosmological eras?

Analysis and Results

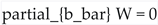

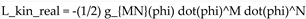

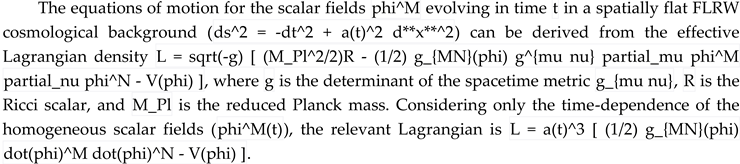

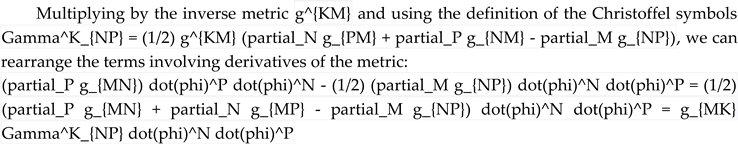

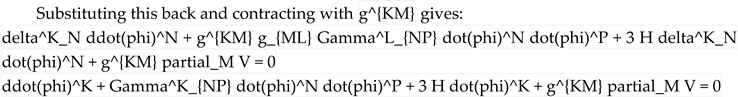

The Dynamical System: Moduli Evolution in Supergravity

- High Dimensionality: The number of real moduli fields (e.g., 2 * h^(2,1) + 2 * h^(1,1) + 2 for complex structure, Kähler, and axio-dilaton fields in Type IIB) can be large in typical Calabi-Yau compactifications, leading to a high-dimensional phase space (Kreuzer and Skarke, 2000).

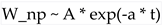

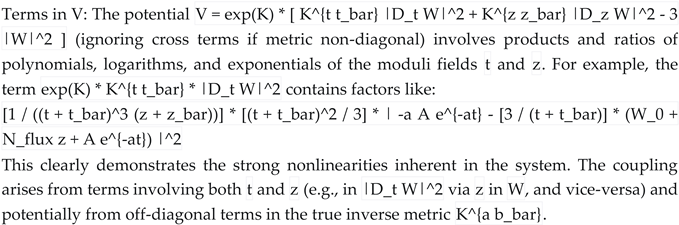

- Nonlinearity: Strong nonlinearities are inherent in the supergravity structure. They arise from the exponential factor exp(K), terms like |D W|^2 and |W|^2 in V, logarithmic dependencies in K (e.g., K ~ -log(Vol)), transcendental functions in W_flux, non-perturbative exponential terms in W_np (e.g., ~ exp(-a*t^i)), and the velocity-squared kinetic terms involving Christoffel symbols Gamma^M_{NP} which depend on the field positions phi^M.

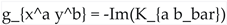

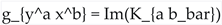

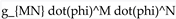

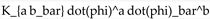

- Coupling: Fields are generically coupled. This occurs through off-diagonal terms in the field-space metric g_{MN} (derived from K_{a b_bar}), through the Christoffel symbols Gamma^M_{NP} in the kinetic terms, and through cross-terms involving different fields within the potential V.

- Parameter Dependence: The system depends critically on the discrete choices of background fluxes N_flux. Different flux choices lead to different forms of W and thus different potential landscapes V, creating a vast "landscape" of different dynamical systems (Denef and Douglas, 2004).

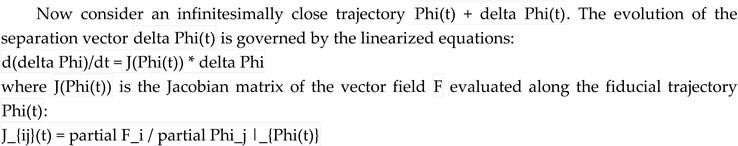

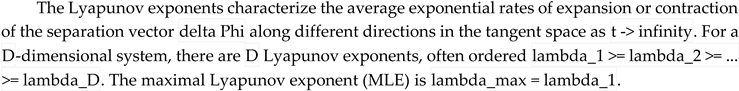

Mathematical Definition of Chaos and Sensitive Dependence (SDIC)

- Sensitive Dependence on Initial Conditions (SDIC): Trajectories starting arbitrarily close together diverge exponentially, on average.

- Topological Transitivity (or Mixing): The dynamics eventually map any given region of the invariant set to overlap with any other region; trajectories explore the entire set over time.

- Density of Periodic Orbits: Unstable periodic orbits are dense within the invariant set.

- where ||...|| denotes a suitable norm in the tangent space, and the limit assumes the initial separation delta Phi(0) is aligned along the direction of maximal expansion (Benettin et al., 1980).

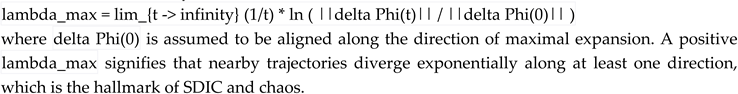

Consequences of SDIC (lambda_max > 0)

- Exponential Loss of Predictability: The exponential divergence exp(lambda_max * t) implies that any uncertainty in the initial conditions delta Phi(0) is amplified exponentially over time. To predict the state Phi(t) with a desired accuracy epsilon after time t, the initial state Phi(0) must be known with an accuracy delta Phi(0) ~ epsilon * exp(-lambda_max * t). This required precision shrinks exponentially, rapidly becoming physically impossible to achieve for any significant evolution time t. Long-term prediction becomes impossible in practice.

- Extreme Sensitivity to Parameters: Just as the system is sensitive to initial conditions, chaotic systems are often extremely sensitive to small changes in system parameters (Ott, 2002). In our context, this suggests that small variations in the underlying parameters defining the potential V (beyond the discrete flux choice, e.g., parameters in W_np or coefficients of alpha' or loop corrections to K) could lead to vastly different dynamical behaviour, further hindering predictability.

- Complex Phase Space Structure: Systems with positive Lyapunov exponents often exhibit complex structures in phase space. For instance, if multiple stable minima (attractors) exist, the boundaries separating their basins of attraction can be fractal (Grebogi, Ott and Yorke, 1983). Trajectories starting near such boundaries exhibit transient chaos and unpredictable final states, making it uncertain which minimum the system will eventually settle into, even if it does settle.

-

Enhanced Vacuum Instability and Potential for Accelerated Decay: Beyond hindering predictable stabilization, chaotic dynamics can actively compromise the stability of potential minima, particularly metastable ones common in string landscape scenarios (e.g., KKLT de Sitter vacua). Mechanisms include:

- ◦

- Dynamical Exploration and Effective Barrier Reduction: Chaotic trajectories explore a large volume of phase space. This exploration might uncover pathways over or through potential barriers that are not apparent in static analyses. The kinetic energy gained during chaotic oscillations can help overcome barriers classically, or the system might dynamically reach configurations where tunneling barriers are effectively lowered, potentially enhancing decay rates Gamma ~ exp(-S), where S is the bounce action.

- ◦

- Increased Probability of Escape: The erratic nature of chaotic motion means the system doesn't simply oscillate stably within a potential well. It constantly probes the boundaries of its basin of attraction. This increases the likelihood, compared to regular motion, of finding an escape route, especially from shallow or complex minima.

- ◦

- Potential for Resonant Effects: Chaotic systems exhibit a broad spectrum of frequencies. It's conceivable that certain frequencies within the chaotic motion could resonate with quantum tunneling modes or other instability triggers, potentially leading to significantly accelerated decay, although this is likely highly model-dependent.

- ◦

- Implication: Even if a suitable metastable minimum exists, chaotic dynamics during the approach or even transiently within the basin could drastically shorten its lifetime, rendering it cosmologically unviable.

Confrontation with Cosmological Requirements

-

Requirement 1: Stable Moduli and Time-Independent Constants: Our universe exhibits stable fundamental constants (electron mass, fine structure constant, etc.) to high precision (Uzan, 2011; Olive and Pospelov, 2008). In string theory, these constants depend on the vacuum expectation values (VEVs) of the moduli fields phi_a. Achieving stable constants requires the moduli to be dynamically stabilized at fixed values phi_a = phi_0, corresponding to a minimum of the potential V.

- ◦

- Conflict with SDIC: If the dynamics near the minimum phi_0 or along the trajectory leading to it were chaotic (lambda_max > 0), reliable stabilization would be compromised. The exponential divergence means that trajectories starting near an intended path to the minimum would rapidly deviate. Even if a minimum exists, reaching it from generic initial conditions becomes highly improbable without extreme fine-tuning. The system might wander indefinitely or be easily perturbed out of shallow minima. Furthermore, chaotic dynamics can actively destabilize minima by enhancing pathways for vacuum decay, potentially destroying the required long-term stability even if a minimum is momentarily reached. The very nature of SDIC resists settling reliably into and remaining within a specific state.

-

Requirement 2: Predictable Cosmological Evolution (e.g., Inflation): Key cosmological epochs, such as inflation, must proceed predictably to explain observations like the cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropies and large-scale structure (Baumann and McAllister, 2015). Successful inflation requires a controlled roll of the inflaton field, a specific number of e-folds, and a predictable end (reheating).

- ◦

- Conflict with SDIC: If the inflaton is a modulus field or is significantly coupled to moduli exhibiting chaotic dynamics, the inflationary trajectory phi_a(t) becomes subject to SDIC. The number of e-folds, the amplitude of generated density perturbations (which depend on the potential and field velocities), and the conditions at the end of inflation would become exponentially sensitive to the pre-inflationary values of phi_a. This would destroy the predictive power of the inflationary scenario, making it impossible to reliably achieve the conditions observed in our universe from generic initial conditions. Any successful prediction would appear as an extreme fine-tuning of initial state parameters, contrary to the motivation for inflation.

Result: Fundamental Conflict

Discussion

, and the fundamental requirements for a cosmologically viable effective field theory derived from string theory. Our results demonstrate that if the evolution of moduli fields

, and the fundamental requirements for a cosmologically viable effective field theory derived from string theory. Our results demonstrate that if the evolution of moduli fields  were governed by chaotic dynamics during crucial cosmological periods, the resulting exponential sensitivity and potential for enhanced vacuum instability would render the universe's evolution unpredictably dependent on initial conditions and potentially too short-lived, fundamentally contradicting the observed stability, predictability, and longevity of our cosmos.

were governed by chaotic dynamics during crucial cosmological periods, the resulting exponential sensitivity and potential for enhanced vacuum instability would render the universe's evolution unpredictably dependent on initial conditions and potentially too short-lived, fundamentally contradicting the observed stability, predictability, and longevity of our cosmos.

Interpreting the Main Result

derived from supergravity remains a formidable challenge, both analytically and computationally. Instead, our analysis focuses on the implications if chaos, as defined mathematically (

derived from supergravity remains a formidable challenge, both analytically and computationally. Instead, our analysis focuses on the implications if chaos, as defined mathematically ( ), were present. We have shown that the primary characteristic of chaos—SDIC—leads to consequences (exponential loss of predictability, unreliable stabilization, and potential enhancement of vacuum decay rates) that are irreconcilable with observations such as the time-independence of fundamental constants, the requirements for successful inflation and reheating, and the apparent long-term stability of our universe.

), were present. We have shown that the primary characteristic of chaos—SDIC—leads to consequences (exponential loss of predictability, unreliable stabilization, and potential enhancement of vacuum decay rates) that are irreconcilable with observations such as the time-independence of fundamental constants, the requirements for successful inflation and reheating, and the apparent long-term stability of our universe.

in the relevant domain of phase space and during the relevant cosmological eras. Any potential

in the relevant domain of phase space and during the relevant cosmological eras. Any potential  arising from a specific flux choice

arising from a specific flux choice  that induces chaotic dynamics (

that induces chaotic dynamics ( ) in regions crucial for cosmological evolution or leads to chaos-induced vacuum decay on timescales shorter than observed cannot describe our universe.

) in regions crucial for cosmological evolution or leads to chaos-induced vacuum decay on timescales shorter than observed cannot describe our universe.

Implications for the String Landscape

) (Susskind, 2003; Douglas, 2003). Much research has focused on identifying vacua within this landscape that possess desirable static properties, such as N=1 supersymmetry (possibly broken), the correct gauge group and matter content for the Standard Model, and a small positive cosmological constant (Denef and Douglas, 2004). Our analysis adds a crucial dynamical constraint: viability requires not only finding a suitable minimum in the potential

) (Susskind, 2003; Douglas, 2003). Much research has focused on identifying vacua within this landscape that possess desirable static properties, such as N=1 supersymmetry (possibly broken), the correct gauge group and matter content for the Standard Model, and a small positive cosmological constant (Denef and Douglas, 2004). Our analysis adds a crucial dynamical constraint: viability requires not only finding a suitable minimum in the potential  but also ensuring that the dynamics governing the evolution towards and stabilization within that minimum are non-chaotic (

but also ensuring that the dynamics governing the evolution towards and stabilization within that minimum are non-chaotic ( ) and do not trigger premature decay.

) and do not trigger premature decay.

that induce chaotic potentials (at least in the cosmologically relevant field ranges and epochs) are effectively ruled out as descriptions of our universe. The requirement of non-chaotic, stable dynamics acts as a selection principle, potentially significantly restricting the subset of viable vacua within the landscape beyond static considerations alone. It underscores the importance of studying not just the minima of the landscape potential but also the dynamical trajectories that populate or avoid these minima, and the stability of those minima against dynamical perturbations.

that induce chaotic potentials (at least in the cosmologically relevant field ranges and epochs) are effectively ruled out as descriptions of our universe. The requirement of non-chaotic, stable dynamics acts as a selection principle, potentially significantly restricting the subset of viable vacua within the landscape beyond static considerations alone. It underscores the importance of studying not just the minima of the landscape potential but also the dynamical trajectories that populate or avoid these minima, and the stability of those minima against dynamical perturbations.

Addressing Potential Subtleties

- Localized Chaos: Could chaos exist but be confined to regions of moduli space far from the eventual vacuum, or limited to very early cosmological times before observable structures are set? While possible, this does not negate the core issue. If the trajectory towards the final vacuum must pass through a chaotic region, SDIC during that phase could still render the final outcome unpredictable, highly sensitive to unmeasurable initial conditions, or even trigger decay before stabilization. Furthermore, if inflation involves moduli fields, chaotic dynamics (

) during this critical period would be disastrous for predictability. The requirement seems to be non-chaotic behavior along the entire relevant cosmological trajectory.

) during this critical period would be disastrous for predictability. The requirement seems to be non-chaotic behavior along the entire relevant cosmological trajectory. - Strength of Stabilization: Could stabilization mechanisms create potential wells so deep and steep that they effectively suppress chaos near the minimum? A stable minimum, by definition, corresponds to locally convergent dynamics (negative eigenvalues of the stability matrix, implying local

). However, the basin of attraction leading to that minimum could still be affected by chaos. If the approach involves traversing regions where

). However, the basin of attraction leading to that minimum could still be affected by chaos. If the approach involves traversing regions where  , predictability is lost. Furthermore, complex systems can exhibit fractal basin boundaries even when the attractors themselves are simple fixed points (Grebogi, Ott and Yorke, 1983), making the final state exquisitely sensitive to initial conditions near the boundaries. Crucially, even if the minimum is deep, chaotic dynamics within the basin might explore escape routes or trigger instabilities (as discussed in 4.3.4) that would not occur with regular dynamics, potentially leading to decay. The stability of the final point does not guarantee a predictable or safe path to it.

, predictability is lost. Furthermore, complex systems can exhibit fractal basin boundaries even when the attractors themselves are simple fixed points (Grebogi, Ott and Yorke, 1983), making the final state exquisitely sensitive to initial conditions near the boundaries. Crucially, even if the minimum is deep, chaotic dynamics within the basin might explore escape routes or trigger instabilities (as discussed in 4.3.4) that would not occur with regular dynamics, potentially leading to decay. The stability of the final point does not guarantee a predictable or safe path to it. - Transient Chaos: Systems can exhibit chaotic behavior for a finite time before settling into a regular state (transient chaos) (Ott, 2002). While potentially less severe than sustained chaos, significant exponential divergence during the transient phase could still amplify initial uncertainties to unacceptable levels, impacting predictability. This is particularly relevant if the transient chaotic phase coincides with critical events like the end of inflation or reheating, where sensitivity can spoil desired outcomes. Moreover, even transient chaos could be sufficient to dynamically probe instability pathways and trigger vacuum decay if the system passes near regions of instability during the chaotic phase.

Predictability in Fundamental Theory

), it would imply a practical limit to our ability to predict the state of the universe, even with perfect knowledge of the underlying laws, due to the impossibility of specifying initial conditions with infinite precision. Furthermore, if chaos actively promotes vacuum decay, it would challenge the very persistence of any realized state. The apparent regularity, predictability, and longevity of our universe, as evidenced by the success of precision cosmology, strongly suggest that such chaotic dynamics are not dominant in the effective laws governing its large-scale evolution.

), it would imply a practical limit to our ability to predict the state of the universe, even with perfect knowledge of the underlying laws, due to the impossibility of specifying initial conditions with infinite precision. Furthermore, if chaos actively promotes vacuum decay, it would challenge the very persistence of any realized state. The apparent regularity, predictability, and longevity of our universe, as evidenced by the success of precision cosmology, strongly suggest that such chaotic dynamics are not dominant in the effective laws governing its large-scale evolution.

Dynamical Selection

) provides a powerful dynamical selection criterion for viable models within the string landscape. It complements static selection criteria (correct particle spectrum, gauge group, etc.) and potentially anthropic arguments. A universe capable of evolving complex structures, including observers, likely requires a degree of stability, predictability, and longevity that is fundamentally incompatible with chaotic dynamics governing its defining parameters. The existence of our stable, predictable universe is therefore evidence that the underlying string theory dynamics, for the specific configuration realized, operate within a non-chaotic and dynamically stable regime.

) provides a powerful dynamical selection criterion for viable models within the string landscape. It complements static selection criteria (correct particle spectrum, gauge group, etc.) and potentially anthropic arguments. A universe capable of evolving complex structures, including observers, likely requires a degree of stability, predictability, and longevity that is fundamentally incompatible with chaotic dynamics governing its defining parameters. The existence of our stable, predictable universe is therefore evidence that the underlying string theory dynamics, for the specific configuration realized, operate within a non-chaotic and dynamically stable regime.

Conclusion

determined by the choice of background fluxes

determined by the choice of background fluxes  , the Kähler potential

, the Kähler potential  , and the superpotential

, and the superpotential  .

.

,

,  , non-perturbative terms), coupling between different moduli fields via the Kähler metric and potential terms, and a critical dependence on the discrete choice of fluxes.

, non-perturbative terms), coupling between different moduli fields via the Kähler metric and potential terms, and a critical dependence on the discrete choice of fluxes.

). The core of our analysis focused on the direct and unavoidable mathematical consequences of SDIC: an exponential amplification of initial uncertainties leading to a fundamental loss of long-term predictability, the inherent difficulty in reliably stabilizing moduli at fixed values, and the potential for chaotic dynamics to actively enhance vacuum instability and accelerate decay processes.

). The core of our analysis focused on the direct and unavoidable mathematical consequences of SDIC: an exponential amplification of initial uncertainties leading to a fundamental loss of long-term predictability, the inherent difficulty in reliably stabilizing moduli at fixed values, and the potential for chaotic dynamics to actively enhance vacuum instability and accelerate decay processes.

). Similarly, the predictability required for crucial epochs like cosmic inflation, which successfully explains large-scale cosmic properties, is destroyed if the underlying scalar field dynamics exhibit SDIC. Furthermore, the apparent longevity of our universe is inconsistent with dynamics that might trigger rapid, chaos-induced vacuum decay.

). Similarly, the predictability required for crucial epochs like cosmic inflation, which successfully explains large-scale cosmic properties, is destroyed if the underlying scalar field dynamics exhibit SDIC. Furthermore, the apparent longevity of our universe is inconsistent with dynamics that might trigger rapid, chaos-induced vacuum decay.

) is phenomenologically disallowed in any string vacuum configuration aiming to describe our observed universe. The stability, predictability, and required longevity inherent in cosmological observations act as a powerful dynamical filter on the string landscape. While the string landscape potentially contains regions or flux choices leading to chaotic dynamics, the specific configuration corresponding to our universe must reside in a regime where the dynamics are non-chaotic (

) is phenomenologically disallowed in any string vacuum configuration aiming to describe our observed universe. The stability, predictability, and required longevity inherent in cosmological observations act as a powerful dynamical filter on the string landscape. While the string landscape potentially contains regions or flux choices leading to chaotic dynamics, the specific configuration corresponding to our universe must reside in a regime where the dynamics are non-chaotic ( ) during all cosmologically relevant periods and in the relevant regions of moduli space, and where these dynamics do not lead to premature vacuum decay.

) during all cosmologically relevant periods and in the relevant regions of moduli space, and where these dynamics do not lead to premature vacuum decay.

Appendix A

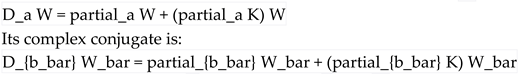

(whose scalar components are the complex moduli

(whose scalar components are the complex moduli  ) (Wess and Bagger, 1992; Freedman and Van Proeyen, 2012). The bosonic part of the Lagrangian relevant for the scalar dynamics in curved spacetime (ignoring fermions and gauge fields for simplicity) is determined by two key functions of the complex scalar fields

) (Wess and Bagger, 1992; Freedman and Van Proeyen, 2012). The bosonic part of the Lagrangian relevant for the scalar dynamics in curved spacetime (ignoring fermions and gauge fields for simplicity) is determined by two key functions of the complex scalar fields  :

:-

Kähler Potential

: A real function whose second derivatives define the Kähler metric of the scalar field manifold:

: A real function whose second derivatives define the Kähler metric of the scalar field manifold: where

where and

and  . This metric determines the scalar kinetic terms. Its inverse is denoted

. This metric determines the scalar kinetic terms. Its inverse is denoted  .

. - Superpotential

: A holomorphic function (

: A holomorphic function ( ).

).

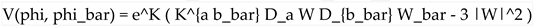

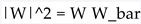

:

:

is derived from

is derived from  and

and  via the standard formula:

via the standard formula: where

where  . This potential governs the interactions and self-interactions of the scalar moduli fields.

. This potential governs the interactions and self-interactions of the scalar moduli fields. are given by:

are given by:

Field Space Metric (Real Fields)

into real and imaginary parts. Let the set of all real scalar components be denoted by

into real and imaginary parts. Let the set of all real scalar components be denoted by  . For example, if we have

. For example, if we have  complex fields

complex fields  , then

, then  represents the

represents the  real fields

real fields  .

. on the space of real fields

on the space of real fields  can be derived from the Kähler metric

can be derived from the Kähler metric  . Using the chain rule (

. Using the chain rule ( ), the kinetic term

), the kinetic term  (in a flat spacetime for simplicity,

(in a flat spacetime for simplicity,  ) must match

) must match  . This yields relations like:

. This yields relations like: . The factor of 1/2 arises from the standard definition of real scalar kinetic terms.

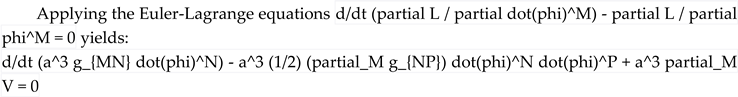

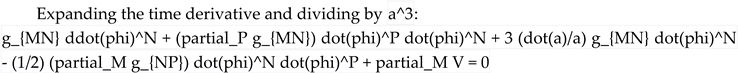

. The factor of 1/2 arises from the standard definition of real scalar kinetic terms.Equations of Motion (Real Fields)

, including the force term from the potential

, including the force term from the potential  and the Hubble friction term

and the Hubble friction term  .

.Lyapunov Exponents: Conceptual Basis

and the linearized equations for

and the linearized equations for  over long times. Techniques like Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization are often employed periodically on the set of vectors spanning the tangent space to prevent numerical overflow and to extract the different exponents (Benettin et al., 1980; Ott, 2002).

over long times. Techniques like Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization are often employed periodically on the set of vectors spanning the tangent space to prevent numerical overflow and to extract the different exponents (Benettin et al., 1980; Ott, 2002).Examples of Nonlinear Terms in V

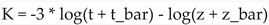

- Kähler Potential:

(Nonlinear logarithms)

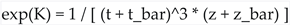

(Nonlinear logarithms) - Exponential Factor:

(Highly nonlinear in

(Highly nonlinear in  and

and  )

) -

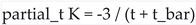

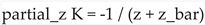

Derivatives of K:

- ◦

- ◦

-

Derivatives of W:

- ◦

- ◦

-

Kähler-Covariant Derivatives:

- ◦

- ◦

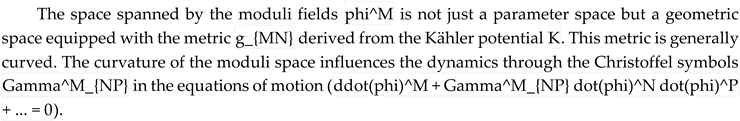

Moduli Space Geometry and Dynamics

) and depend on position (

) and depend on position ( ) through the metric components in

) through the metric components in  . Geodesic motion (motion under no potential,

. Geodesic motion (motion under no potential,  ) on a curved manifold can itself be chaotic. For instance, geodesic motion on a surface of constant negative curvature is a classic example of chaotic dynamics (Ott, 2002). While the potential

) on a curved manifold can itself be chaotic. For instance, geodesic motion on a surface of constant negative curvature is a classic example of chaotic dynamics (Ott, 2002). While the potential  often dominates the dynamics in string cosmology, the underlying geometry can also play a role, particularly if the potential is relatively flat or if the space has regions of significant negative curvature, which tends to enhance the divergence of nearby trajectories (related to the geodesic deviation equation).

often dominates the dynamics in string cosmology, the underlying geometry can also play a role, particularly if the potential is relatively flat or if the space has regions of significant negative curvature, which tends to enhance the divergence of nearby trajectories (related to the geodesic deviation equation).References

- Aazami, A.; Easther, R. (2006) Cosmology from random potentials. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2006(03), 013. [CrossRef]

- Ashok, S.K.; Douglas, M.R. (2004) Counting flux vacua. Journal of High Energy Physics 2004(01), 060. [CrossRef]

- Bachlechner, T.; Marsh, M.C.D.; McAllister, L.; Wrase, T. (2017) Searching the landscape of random supergravities. Journal of High Energy Physics 2017(1), 123. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, V.; Berglund, P.; Conlon, J.P.; Quevedo, F.; Suruliz, K. (2005) Systematics of moduli stabilisation in Calabi-Yau flux compactifications. Journal of High Energy Physics 2005(03), 007. [CrossRef]

- Banks, T.; Kaplan, D.B.; Nelson, A.E. (1994) Cosmological implications of dynamical supersymmetry breaking. Physical Review D 49(2), 779–787. [CrossRef]

- Baumann, D.; McAllister, L. (2015) Inflation and String Theory; Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Becker, M.; Haack, M.; Louis, J. (2002) Supersymmetry breaking and alpha-prime corrections to flux induced potentials. Journal of High Energy Physics 2002(06), 060. [CrossRef]

- Benettin, G.; Galgani, L.; Giorgilli, A.; Strelcyn, J.-M. (1980) Lyapunov characteristic exponents for smooth dynamical systems and for Hamiltonian systems; a method for computing all of them. Part 1: Theory and Part 2: Numerical application. Meccanica 15(1), 9–30. [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.; Haack, M.; Pajer, E. (2006) Constructing string vacua with stabilized moduli. Physical Review D 73(4), 046006. [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R.; Polchinski, J. (2000) Quantization of four-form fluxes and dynamical neutralization of the cosmological constant. Journal of High Energy Physics 2000(06), 006. [CrossRef]

- Brustein, R.; Steinhardt, P.J. (1993) Challenges for superstring cosmology. Physics Letters B 302(2-3), 196–201. [CrossRef]

- Candelas, P.; Horowitz, G.T.; Strominger, A.; Witten, E. (1985) Vacuum configurations for superstrings. Nuclear Physics B 258, 46–74. [CrossRef]

- Cicoli, M. (2013) String Loop Effects in Flux Compactifications and Inflation. Classical and Quantum Gravity 30(21), 214002. [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.P.; Quevedo, F.; Suruliz, K. (2005) Large-volume flux compactifications: Moduli spectrum and D3/D7 inflation. Journal of High Energy Physics 2005(08), 007. [CrossRef]

- Copeland, E.J.; Liddle, A.R.; Lyth, D.H. (1998) Chaotic hybrid inflation. Physical Review D 58(6), 063508. [CrossRef]

- de Carlos, B.; Casas, J.A.; Quevedo, F.; Roulet, E. (1993) Model independent properties and cosmological implications of the dilaton and moduli sectors of 4-d strings. Physics Letters B 318(3), 447–456. [CrossRef]

- Denef, F.; Douglas, M.R. (2004) Distributions of flux vacua. Journal of High Energy Physics 2004(05), 072. [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.; Frazer, J.; Liddle, A.R. (2012) Multifield consequences for D-brane inflation. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2012(06), 020. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, S.; Kachru, S.; McGreevy, J.; Wacker, J.G. (2008) N-flation. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2008(08), 003. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.R. (2003) The statistics of string/M theory vacua. Journal of High Energy Physics 2003(05), 046. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.R.; Kachru, S. (2007) Flux compactification. Reviews of Modern Physics 79(2), 733–796. [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.Z.; Van Proeyen, A. (2012) Supergravity; Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Giddings, S.B.; Kachru, S.; Polchinski, J. (2002) Hierarchies from fluxes in string compactifications. Physical Review D 66(10), 106006. [CrossRef]

- Grana, M. (2006) Flux compactifications in string theory: A comprehensive review. Physics Reports 423(3), 91–158. [CrossRef]

- Grebogi, C.; Ott, E.; Yorke, J.A. (1983) Fractal basin boundaries, long-lived chaotic transients, and unstable-unstable pair bifurcation. Physical Review Letters 50(13), 935–938. [CrossRef]

- Green, M.B.; Schwarz, J.H.; Witten, E. (1987) Superstring Theory; Cambridge University Press; (2 Volumes); ISBN 978-0521357524, 978-0521357531.

- Gukov, S.; Vafa, C.; Witten, E. (2000) CFT's from Calabi-Yau four-folds. Nuclear Physics B 584(1-2), 69–108, Erratum-ibid. B608 (2001) 477-478. [CrossRef]

- Kachru, S.; Kallosh, R.; Linde, A.; Trivedi, S.P. (2003) De Sitter vacua in string theory. Physical Review D 68(4), 046005. [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, M.; Skarke, H. (2000) Complete classification of reflexive polyhedra in four dimensions. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 4(6), 1209–1230. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, D.J.; McAllister, L.; Wrase, T. (2013) Inflation and the Starobinsky Model in Flux Compactifications. Journal of High Energy Physics 2013(12), 078. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, M.C.D.; McAllister, L.; Wrase, T. (2014) The wasteland of random supergravities. Journal of High Energy Physics 2014(3), 102. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pedrera, D.; Mehta, P.; Rummel, M. (2013) Finding the needle in the haystack: the statistics of locating desired vacua in the landscape. Journal of High Energy Physics 2013(6), 110. [CrossRef]

- McAllister, L.; Silverstein, E.; Westphal, A. (2010) Gravity waves and linear inflation from axion monodromy. Physical Review D 82(4), 046003. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.I.; Vilenkin, A. (2018) Fractal boundaries in the string theory landscape. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2018(03), 006. [CrossRef]

- Olive, K.A.; Pospelov, M. (2008) Environmental dependence of masses and coupling constants. Physical Review D 77(4), 043524. [CrossRef]

- Ott, E. (2002) Chaos in Dynamical Systems, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Polchinski, J. (1998) String Theory. Cambridge University Press; (2 Volumes); ISBN 978-0521633031, 978-0521633048.

- Silverstein, E.; Westphal, A. (2008) Monodromy in the CMB: Gravity waves and string inflation. Physical Review D 78(10), 106003. [CrossRef]

- Strogatz, S.H. (2015) Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering, 2nd ed.; Westview Press; ISBN 978-0813349107.

- Sumitomo, Y.; Tye, S.H.H. (2012) A Stringy Mechanism for A Small Vacuum Energy - Multi-moduli Cases -. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2012(11), 006. [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. (2003) The Anthropic Landscape of String Theory. arXiv:preprint hep-th/0302219. [CrossRef]

- Underwood, B. (2011) A systematic study of D-brane inflation. Journal of High Energy Physics 2011(11), 097. [CrossRef]

- Uzan, J.-P. (2011) Varying Constants, Gravitation and Cosmology. Living Reviews in Relativity 14(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Wess, J.; Bagger, J. (1992) Supersymmetry and Supergravity, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press; ISBN 978-0691025308.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).