Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

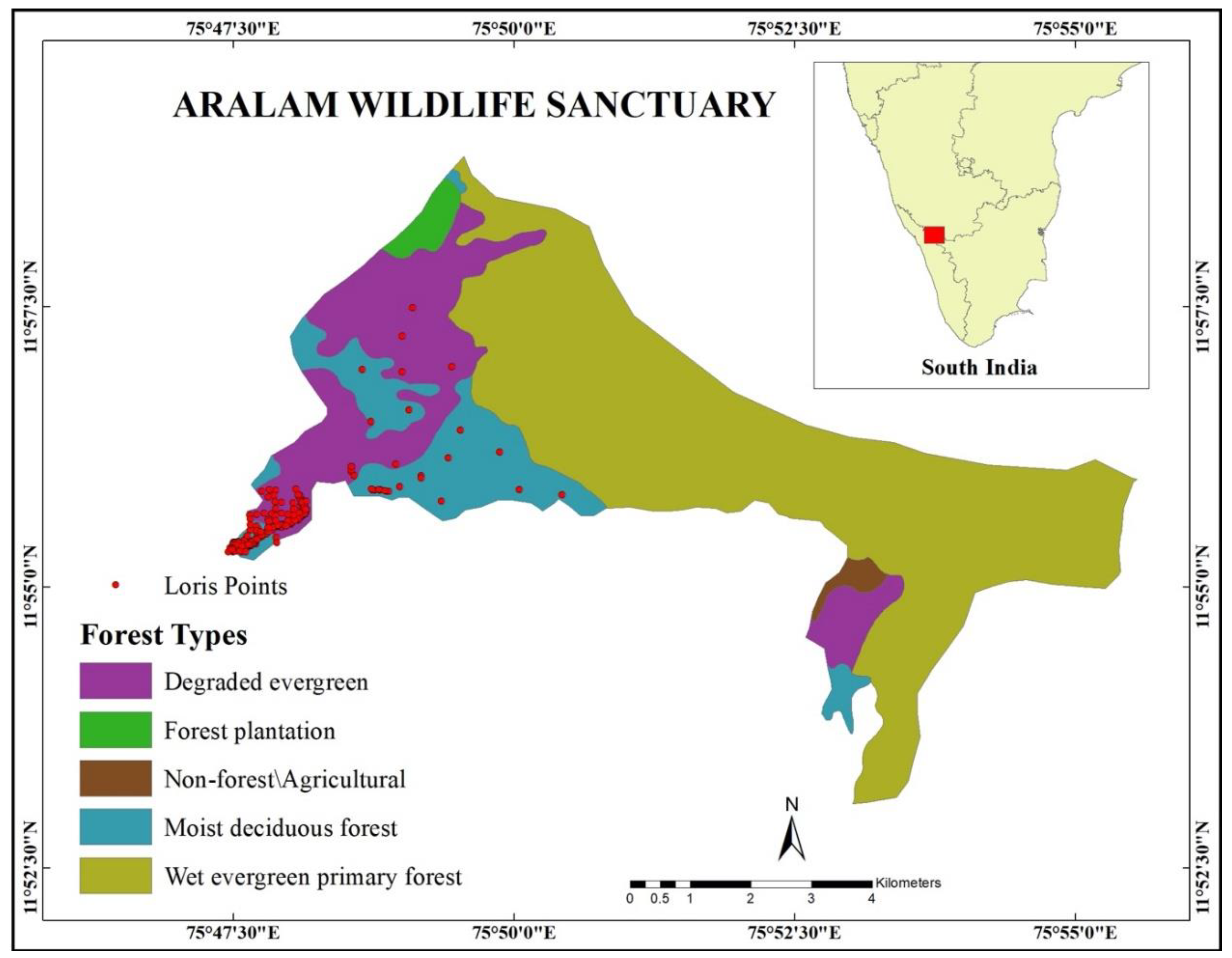

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Observation of Slender Loris Habitat Use

2.3. Vegetation Sampling

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Note

3. Results

3.1. Habitat Structure

3.1.1. Tree Species

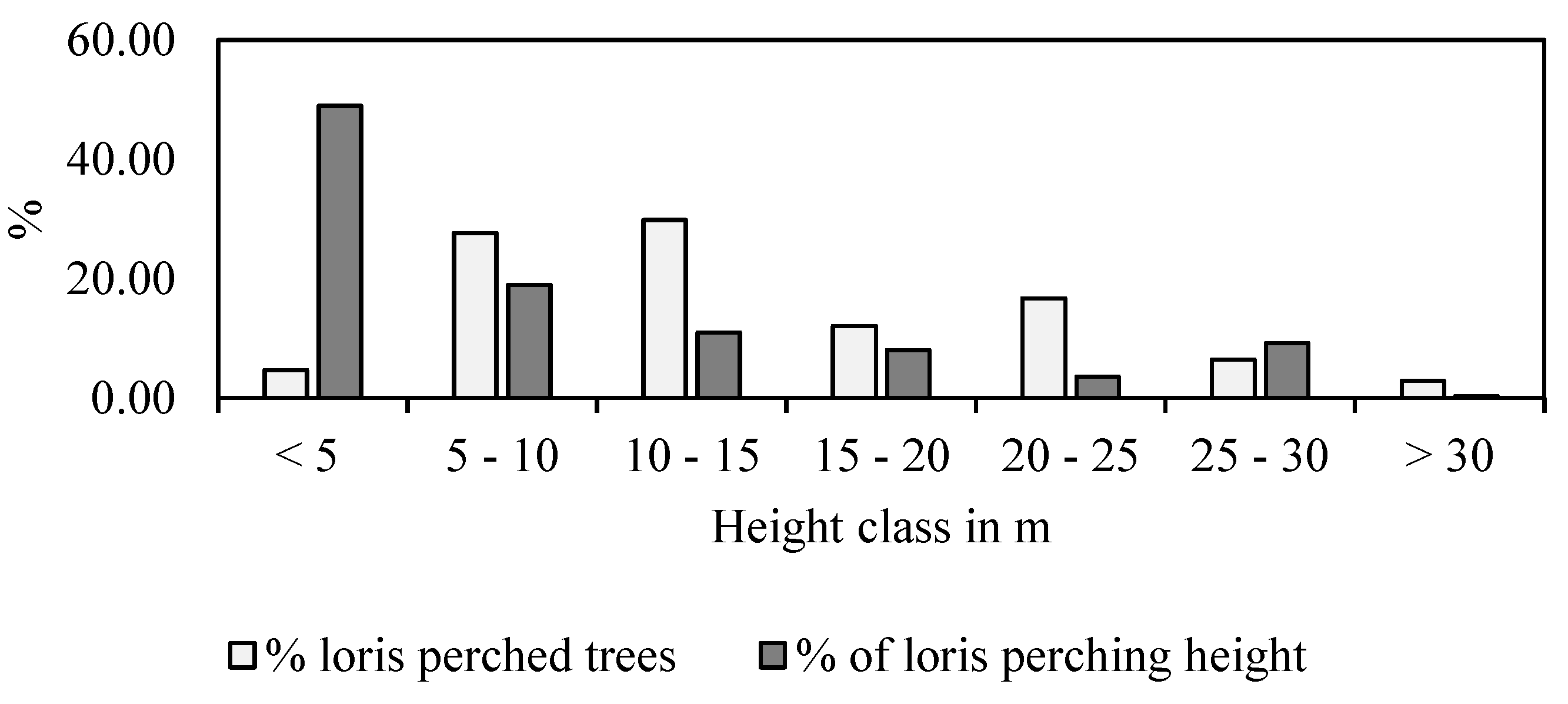

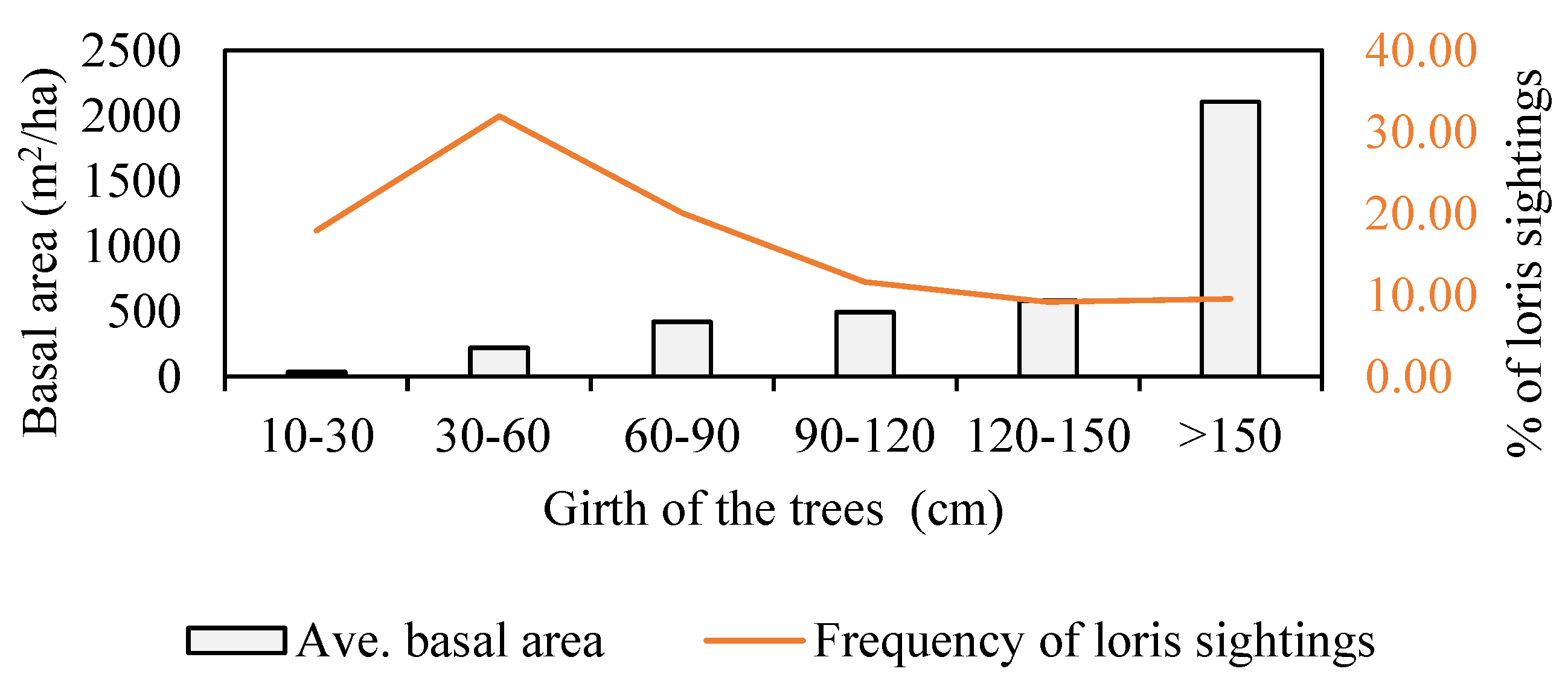

3.1.2. Density, Distribution, Height, Girth and Basal Area of Trees

3.1.3. Canopy and Ground Cover

3.1.4. Climbers

3.1.5. Climber and Leaf Connectivity

3.2. Habitat Use

3.2.1. Tree Use by Lorises

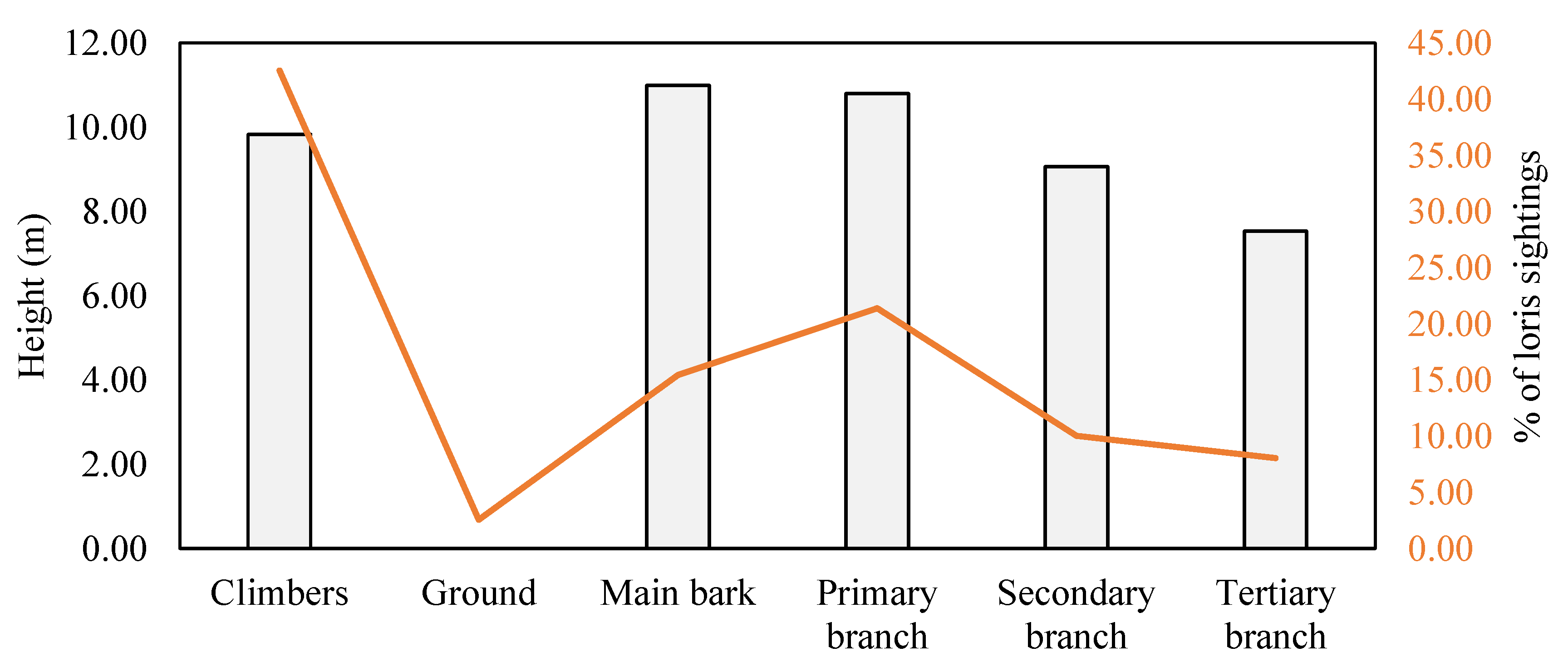

3.2.2. Substrate Size and Orientation

3.2.3. Time Spent at Various Substrates

3.2.4. Climbers Used by Lorises

3.2.5. Vegetation used for sleeping and feeding

4. Discussion

4.1. Vegetation Composition and Tree Diversity

4.2. Loris Habitat Preferences

4.3. Arboreal Locomotion and Substrate Use

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Species | All Trees | Loris encountered | Average Height | Average DBH | Distribution | Tree Type | |

| Count | % | Tree (m) | Occupied (m) | (cm) | |||

| Aporosa cardiosperma | 289 | 13.38 | 9.29 ± 0.77 | 9.46 ± 1.36 | 12.77 ± 0.58 | India and Sri Lanka | Evergreen |

| Xylia xylocarpa | 226 | 11.62 | 19.02 ± 1.28 | 9.99 ± 1.41 | 29.5 ± 1.11 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Naringi crenulata | 221 | 9.15 | 12.16 ± 1.13 | 7.74 ± 1.49 | 10.93 ± 6.46 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Hopea parviflora | 145 | 2.46 | 11.7 ± 2.39 | 13.43 ± 4.56 | 11.93 ± 0.84 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Antides mabunius | 136 | 1.76 | 11.28 ± 2.24 | 14.93 ± 5.71 | 13.06 ± 0.91 | Indo-Malesia to Australia and South China | Evergreen |

| Gossypium herbaceum | 83 | - | 9.15 ± 5.07 | - | 10.78 ± 0.65 | India, Arab, Persia, Afghanistan, Turkey, North Africa, Spain, Ukraine, China | Evergreen |

| Actinodaphne maderaspatana | 82 | 2.46 | 8.62 ± 1.77 | 9.08 ± 2.84 | 15.5 ± 2.18 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Antiaris toxicaria | 71 | - | 17.29 ± 1.78 | - | 28.87 ± 1.79 | Paleotropics | Evergreen |

| Terminalia paniculata | 70 | 3.87 | 12.69 ± 1.87 | 8.73 ± 2.69 | 28.62 ± 2.91 | India | Deciduous |

| Schleichera oleosa | 63 | 2.82 | 22.14 ± 2.26 | 11.34 ± 2.91 | 18.3 ± 1.87 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Chionanthus mala-elengi subsp. mala-elengi | 59 | 1.76 | 6.71 ± 0.67 | 8.41 ± 3.44 | 10.07 ± 0.48 | Endemic to Peninsular India | Evergreen |

| Xanthophyllum flavescens | 57 | 1.76 | 9.63 ± 1.23 | 11.2 ± 3.12 | 8.33 ± 0.51 | China to Indomalaysia | Deciduous |

| Strychnosnux-vomica | 55 | 0.35 | 21.95 | 9.14 | 7.47 ± 0.79 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Chionanthus albidiflorus | 54 | - | 7.64 ± 3.95 | - | 8.83 ± 0.95 | Indo-Malesia | Evergreen |

| Dead Trees | 53 | 3.17 | 16.49 ± 1.69 | 8.41 ± 2.93 | 28.47 ± 1.98 | ||

| Polyalthia longifolia | 53 | 0.35 | 10.06 | 1 | 6.72 ± 0.71 | India and Sri Lanka | Evergreen |

| Stereospermum colais | 50 | 0.7 | 17.83 ± 7.17 | 13.5 ± 8.5 | 19.74 ± 1.66 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Syzygium cumini | 50 | 0.7 | 19.2 ± 9.45 | 15 | 10.25 ± 0.99 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Vateria indica | 49 | 1.06 | 16.97 ± 7.82 | 13.53 ± 8.67 | 16.98 ± 2.16 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Holigarna arnottiana | 47 | 5.28 | 17.43 ± 1.85 | 12.04 ± 2.71 | 25.85 ± 2.96 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Plumeria obtusa | 45 | 2.46 | 11.58 ± 1.91 | 5.84 ± 1.61 | 21.55 ± 3.73 | Central America, from Mexico to Panam | Deciduous |

| Sapindus trifoliatus | 44 | 1.41 | 14.86 ± 1.82 | 8.65 ± 3.87 | 13.41 ± 1.56 | South Asia | Deciduous |

| Artocarpus hirsutus | 43 | 3.52 | 21.82 ± 0.89 | 16.72 ± 3.71 | 29.53 ± 3.43 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Dillenia pentagyna | 40 | 2.11 | 27.13 ± 2.67 | 10.48 ± 4.81 | 51.41 ± 6.1 | China to Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Baccaurea courtallensis | 39 | 0.35 | 8.53 | 2.74 | 7.19 ± 0.47 | Endemic to Peninsular India | Evergreen |

| Myristica beddomei | 38 | 2.82 | 12.03 ± 2.45 | 4.72 ± 2.95 | 12.81 ± 1.13 | Endemic to Peninsular India | Evergreen |

| Lagerstroemia speciosa subsp. Speciosa | 37 | 0.7 | 25.3 | 16.22 ± 13.79 | 22.07 ± 2.1 | S-China (Yunnan), India, | Evergreen |

| Shorea roxburghii | 36 | 0.7 | 7.01 | 4 ± 1 | 7.92 ± 1.16 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Rotheca serrata | 33 | 4.23 | 10.24 ± 1.13 | 15.24 ± 3.21 | 12.26 ± 1.35 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Drypetes venusta | 32 | 1.06 | 10.06 ± 2.14 | 13.45 ± 8.59 | 11.15 ± 1.68 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Deciduous |

| Buchanania axillaris | 30 | 2.11 | 13.56 ± 3.56 | 6.08 ± 2.45 | 13.75 ± 1.95 | India and Sri Lanka, Myanmar | Deciduous |

| Anacolosa densiflora | 26 | 0.7 | 12.04 ± 0.15 | 16.5 ± 13.5 | 17.95 ± 3.82 | India | Evergreen |

| Madhuca longifolia | 26 | 0.35 | 7.32 | 4.57 | 7.09 ± 0.69 | India and Myanmar | Deciduous |

| Lagerstroemia microcarpa | 25 | 0.35 | 22.56 | 18 | 28.01 ± 3.86 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Deciduous |

| Clausena anisata | 23 | 1.41 | 13.94 ± 0.89 | 9.93 ± 6.06 | 11.93 ± 1.53 | India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Africa | Evergreen |

| Butea monosperma | 20 | 0.7 | 17.53 ± 1.68 | 6.1 ± 6.1 | 19.91 ± 4.79 | India, Sri Lanka and S.E.Asia. | Deciduous |

| Gmelina arborea | 20 | 0.7 | 17.53 ± 1.37 | 6.86 ± 2.29 | 22.47 ± 4.69 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Terminalia bellirica | 19 | 0.7 | 22.1 ± 0.15 | 6 ± 4 | 40.94 ± 5.95 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Vatica chinensis | 18 | - | 11.08 ± 5.59 | - | 12.41 ± 1.22 | India and Sri Lanka | Evergreen |

| Ixora polyantha | 17 | - | 4.99 ± 2.37 | - | 6.13 ± 0.35 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Tarenna monosperma | 17 | - | 6.71 ± 4.18 | - | 5.82 ± 0.59 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Lannea coromandelica | 15 | 1.41 | 19.66 ± 3.55 | 8.75 ± 3.45 | 31.64 ± 5.79 | Southern Asia | Deciduous |

| Litsea coriacea | 15 | 1.06 | 10.87 ± 1.93 | 15.5 ± 8.23 | 10.12 ± 2.03 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Knema attenuata | 14 | - | 12.21 ± 7.15 | - | 8.14 ± 0.85 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Deciduous |

| Melia azedarach | 14 | - | 5.70 ± 1.73 | - | 7.55 ± 0.89 | Paleotropics | Deciduous |

| Solanum erianthum | 12 | 0.35 | 8.23 | 5.5 | 8.73 ± 0.98 | South East Asia and North Australia | Deciduous |

| Vitex altissima | 12 | 0.35 | 22.25 | 30 | 30.58 ± 4.59 | India | Deciduous |

| Terminalia crenulata | 11 | 1.06 | 25.1 ± 0.81 | 11.38 ± 8.33 | 91.56 ± 6.59 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Olea wightiana | 11 | 0.7 | 12.19 ± 3.96 | 10 ± 5 | 10.91 ± 2.07 | Endemic to Peninsular India | Deciduous |

| Alstonia scholaris | 10 | 0.35 | 7.62 | 10 | 9.2 ± 2.41 | South and South East Asia to Australia | Evergreen |

| Artocarpus gomezianus | 10 | 0.35 | 11.89 | 9.14 | 23.78 ± 4.22 | India and Sri Lanka | Deciduous |

| Cinnamomum keralaense | 9 | 0.35 | 9.14 | 20 | 11.74 ± 2.26 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Atalantia monophylla | 8 | - | 11.05 ± 1.70 | - | 15.24 ± 2.8 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Memecylon umbellatum | 8 | - | 9.75 ± 2.96 | - | 11.09 ± 2.03 | India and Sri Lanka | Deciduous |

| Polyalthia fragrans | 8 | - | 4.23 ± 3.11 | - | 8.12 ± 1.93 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Erythrina stricta | 8 | 1.41 | 21.11 ± 4.17 | 6.69 ± 3.77 | 26.94 ± 3.71 | India, China, Nepal, Thailand and Vietnam | Deciduous |

| Scolopia crenata | 8 | 0.35 | 8.53 | 10 | 7.44 ± 0.76 | Indo-Malesia | Evergreen |

| Hopea ponga | 7 | - | 13.44 ± 9.11 | - | 14.23 ± 4.51 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Lepisanthes tetraphylla | 7 | - | 6.14 ± 2.14 | - | 5.5 ± 1.37 | Indo-Malesia and Africa | Evergreen |

| Sterculia villosa | 6 | - | 6.14 ± 2.14 | - | 9.97 ± 3.43 | South Asia and Myanmar | Deciduous |

| Dalbergia lanceolaria subsp. paniculata | 6 | 1.06 | 9.75 | 5.19 ± 2.62 | 12.47 ± 2.19 | India and Myanmar | Deciduous |

| Adina cordifolia | 5 | - | 15.02 ± 4.97 | - | 8.94 ± 1.23 | India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Indo-China | Deciduous |

| Agrostistachys borneensis | 5 | - | 5.00 ± 1.14 | - | 9.17 ± 0.23 | Indo-Malaya | Evergreen |

| Elaeocarpus serratus | 5 | - | 10.24 ± 6.81 | - | 16.81 ± 3.34 | India, Nepal, Malaysia | Evergreen |

| Neolamarckia cadamba | 5 | - | 8.47 ± 5.48 | - | 6.18 ± 1.48 | Asia, Pacific and Australia | Deciduous |

| Commiphora caudata | 5 | 0.7 | 21.18 ± 1.98 | 21.5 ± 6.5 | 21.84 ± 5.25 | India and Sri Lanka | Deciduous |

| Bridelia retusa | 4 | - | 5.87 ± 1.48 | - | 8.1 ± 1.12 | Indo-Malaya | Deciduous |

| Grewia tiliifolia Vahl | 4 | - | 15.62 ± 1.2 | - | 47.35 ± 13.13 | Tropical Africa, India to Indo-China | Deciduous |

| Wrightia arborea | 4 | - | 12.10 ± 2.9 | - | 27.06 ± 7.72 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Cinnamomum malabatrum | 4 | 0.35 | 29.57 | 10 | 18.46 ± 6.24 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Sterculia balanghas | 4 | 0.35 | 10 | 10 | 5.33 ± 1.94 | South Asia and Myanmar | Deciduous |

| Plumeria rubra | 3 | - | 7.92 ± 2.60 | - | 4.35 ± 0.46 | Native of Tropical America; widely naturalised elsewhere in the tropics | Deciduous |

| Casearia ovata | 2 | - | 5.94 ± 1.07 | - | 22.76 ± 18.62 | India and Sri Lanka | Evergreen |

| Garcinia morella | 2 | - | 6.40 ± 0 | - | 6.37 ± 0 | Indo-Malesia | Evergreen |

| Mallotus nudiflorus | 2 | - | 13.16 ± 5.84 | - | 9.55 ± 1.91 | Indo-Malaya | Evergreen |

| Terminalia alata | 2 | - | 14.62 ± 1.2 | - | 6.05 ± 0.64 | India | Deciduous |

| Terminalia catappa | 2 | - | 3.33 ± 0.46 | - | 4.3 ± 0.16 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Azadirachta indica | 1 | - | 16 | - | 21.65 | Indo-Malesia | Evergreen |

| Calophyllum inophyllum | 1 | - | - | 35.01 | Paleotropics | Evergreen | |

| Garcinia gummi-gutta | 1 | - | 5.49 | - | 3.18 | South India and Sri Lanka | Evergreen |

| Mangifera indica | 1 | - | 8.53 | - | 10.5 | Native to India and Burma. | Evergreen |

| Manilkara roxburghiana | 1 | - | 5.23 | - | 14.01 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Manilkara zapota | 1 | - | 8.23 | - | 53.16 | India and tropical America | Evergreen |

| Scleropyrum pentandrum | 1 | - | 11.28 | - | 6.37 | India and Sri Lanka | Evergreen |

| Spondia spinnata | 1 | - | 17.37 | - | 22.92 | Indo-Malesia | Deciduous |

| Dysoxylum malabaricum | 1 | 0.35 | 11.28 | 5 | 15.92 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

| Syzygium mundagam | 1 | 0.35 | 12.5 | 3.04 | 18.46 | Endemic to Western Ghats | Evergreen |

References

- Overdorff, D.J. Ecological correlates to social structure in two lemur species in Madagascar. Am J Phys Anthropol 1996, 100, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, E.P. Ranging patterns and habitat use of Sulawesi Tonkean macaques (Macaca tonkeana) in a human-modified habitat. Am J Primatol 2008, 70, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiduck, S. The use of disturbed and undisturbed forest by masked titi monkeys Callicebus personatus melanochir is proportional to food availability. Oryx 2002, 36, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The effect of forest clear-cutting on habitat use in Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in Shennongjia Nature Reserve, China. Primates 2004, 45, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campera, M.; Serra, V.; Balestri, M.; Barresi, M.; Ravaolahy, M.; Randriatafika, F.; Donati, G. Effects of habitat quality and seasonality on ranging patterns of collared brown lemur (Eulemur collaris) in littoral forest fragments. Int J Primatol 2014, 35, 957–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppley, T.M.; Hoeks, S.; Chapman, C.A.; Ganzhorn, J.U.; Hall, K.; Owen, M.A.; Adams, D.B.; Allgas, N.; Amato, K.R.; Andriamahaihavana, M.; et al. Factors influencing terrestriality in primates of the Americas and Madagascar. Proc Nat Ac Sci 2022, 119, e2121105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, G.R.; Marshall, A.J. Terrestriality across the primate order: A review and analysis of ground use in primates. Evol Anthropol 2024, 33, e22032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGraw, W.S.; Bshary, R. Association of terrestrial mangabeys (Cercocebus atys) with arboreal monkeys: experimental evidence for the effects of reduced ground predator pressure on habitat use. Int J Primatol 2002, 23, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, S.; Tschapka, M.; Heymann, E.W.; Heer, K. Vertical stratification of seed-dispersing vertebrate communities and their interactions with plants in tropical forests. Biol Rev 2021, 96, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Lin, N.; Huang, A.; Tong, D.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, C. Feeding postures and substrate use of François’ langurs (Trachypithecus francoisi) in the limestone forest of Southwest China. Animals 2024, 14, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Terrestriality and tree stratum use in a group of Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys. Primates 2007, 48, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.M.; Sterr, S.M.; Garber, P.A. Habitat use and ranging behavior of Callimico goeldii. Int J Primatol 2007, 28, 1035–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kumara, H.N.; Ananda, K.M.; Sharma, A.K. Behavioral responses of lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus) to a changing habitat in a tropical rain forest fragment in Western Ghats, India. Folia Primatol 2001, 72, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourthe, I.M.C.; Guedes, D.; Fidelis, J.; Boubli, J.P.; Mendes, S.L.; Strier, K.B. Ground use by northern muriquis. Am J Primatol 2007, 69, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, L.K.; Chapman, C.A. Primates in Fragments: Complexity and Resilience. New York, Springer, 2013.

- Ramsay, M.S.; Mercado Malabet, F.; Klass, K.; Ahmed, T.; Muzaffar, S. Consequences of habitat loss and fragmentation for primate behavioral ecology. In Primates in anthropogenic landscapes: Exploring primate behavioural flexibility across human contexts, pp. 9-28. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023.

- Arroyo-Rodríguez, V.; Mandujano, S. Conceptualization and measurement of habitat fragmentation from the primates’ perspective. Int J Primatol 2009, 30, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabarelli, M.; Gascon, C. Lessons from fragmentation research: improving management and policy guidelines for biodiversity conservation. Conserv Biol 2005, 19, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienert, J. Habitat fragmentation effects on fitness of plant populations – a review. J Nat Conserv 2004, 12, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umapathy, G.; Kumar, A. Impacts of forest fragmentation on lion-tailed macaque and Nilgiri langur in Western Ghats, south India. In L. K. Marsh (Ed.), Primates in fragments: Ecology and conservation, pp. 163–189. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press, 2003.

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.; Sandun, J. A review of the distribution of Grey Slender Loris (Loris lydekkerianus) in Sri Lanka. Prim Conserv 2008, 23, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanaolivu, S.D.; Kumara, H.N.; Singh, M.; Sudarsanam, D. Ecological determinants of Malabar Slender Loris (Loris lydekkerianus malabaricus, Cabrera 1908) occupancy and abundance in Aralam Wildlife Sanctuary, Western Ghats, India. Int J Primatol 2020, 41, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, H.; Meier, B. The subspecies of Loris tardigradus and their conservation status: A review. In L. Alterman, G. A. Doyle, & M. K. Izard (Eds.), Creatures of the dark: The nocturnal prosimians, pp. 193–210. New York: Plenum Press, 1995.

- Dittus, W.; Singh, M.; Gamage, S.N.; Kumara, H.N.; Kumar, A.; Nekaris, K.A.I. Loris lydekkerianus (amended version of 2020 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T44722A217741551. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishna, S.; Singh, M. Social behaviour of the slender loris (Loris tardigradus lydekkerianus). Folia Primatol 2002, 73, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekaris, K.; Bearder, S. The lorisiform primates of Asia and mainland Africa: Diversity shrouded in darkness. In C. J. Campbell, A. Fuentes, K. C. Mackinnon, M. Panger, & S. K. Bearder (Eds.), Primates in perspective, pp. 24–45. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Kumara, H.N.; Singh, M.; Kumar, S. Distribution, habitat correlates, and conservation of Loris lydekkerianus in Karnataka, India. Int J Primatol 2006, 27, 941–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishna, S.; Kumara, H.N.; Sasi, R. Distribution patterns of slender loris subspecies (Loris lydekkerianus) in Kerala, Southern India. Int J Primatol 2011, 32, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, S.N.; Padmalal, U.K.G.K.; Kotagama, S.W. Montane slender loris (Loris tardigradus nycticeboides) is a critically endangered primate that needs more conservation attention. J Dept Wildl Conserv 2014, 2, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gamage, S.; Liyanage, W.; Weerakoon, D.; Gunwardena, A. Habitat quality and availability of the Sri Lanka red slender Loris Loris tardigradus tardigradus (Mammalia: Primates: Lorisidae) in the Kottawa Arboretum. J Threatened Taxa 2009, 1, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, C.J.; Gamage, S.N.; Mahanayakage, C.A.; Padmalal, U.K.G.K.; Kotagama, S.W. Habitat suitability modelling for Montane Slender Loris in the Hakgala Strict Nature Reserve: A Geoinformatics approach. Wildlanka 2015, 3, 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Lindburg, D.G.; Udhayan, A.; Kumar, M.A.; Kumara, H.N. Status survey of slender loris Loris tardigradus lydekkerianus in Dindigul, Tamil Nadu, India. Oryx 1999, 33, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, D.T.; Izard, M.K. Scaling of growth and life history traits relative to body size, brain size, and metabolic rate in lorises and galagos (Lorisidae, Primates). Am J Phys Anthropol 1988, 75, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasi, R.; Kumara, H.N. Distribution and relative abundance of the slender loris Loris lydekkerianus in Southern Kerala, India. Prim Conserv 2014, 28, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanaolivu, S.D.; Erinjery, J.J.; Campera, M.; Singh, M. Distribution and habitat suitability of the Malabar Slender Loris (Lorislydekkerianus malabaricus) in the Aralam Wildlife Sanctuary, India. Land 2025, 14, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.R.R. Vegetation mapping and analysis of Aralam Wildlife Sanctuary using remote sensing techniques. KFRI Research Report 1999, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Charles-Dominique, P.; Bearder, S.K. Field studies of lorisoid behaviour: Methodological aspects. In G. A. Doyle & R. D. Martin (Eds.), The study of prosimian behaviour, pp. 567–629. New York: Academic Press, 1979.

- Nekaris, K.A. Foraging behaviour of the slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus lydekkerianus): Implications for theories of primate origins. J Hum Evol 2005, 49, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekaris, K.A.I. Activity budget and positional behavior of the Mysore slender loris (Loris tardigradus lydekkarianus): Implications for “slow climbing” locomotion. Folia Primatol 2001, 72, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, E.J.; Ramaroson, M.G. Rapid Assessment of the primate fauna of the eastern slopes of the Réserve Naturelle Intégrale d’Andringitra. Fieldiana: Zoology New Series 1996, 85, 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Nekaris, K.A.I. Observations of mating, birthing and parental behaviour in three subspecies of Slender Loris (Loris tardigradus and Loris lydekkerianus) in India and Sri Lanka. Int J Primatol 2003, 74, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, W.J. Ecological Census Techniques. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Nekaris, K.A.I.; Liyanage, W.; Gamage, S. Influence of forest structure and composition on population density of the red slender loris Loris tardigradus tardigradus in Masmullah proposed forest reserve, Sri Lanka. Mammalia 2005, 69, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, N. Illustrated manual on tree flora of Kerala supplemented with computer-aided identification. KFRI Research Report 2006, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Sasidharan, N. (Ed.). (2010). Forest Trees of Kerala, a checklist including exotics. KFRI Handbook No. 2.

- Sellers, W. A biomechanical investigation into the absence of leaping in the locomotor repertoire of the slender loris (Loris tardigradus). Folia Primatol 1996, 67, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensociologie: Grundzuge der Vegetationskunde, 3te aufl. Vienna: Springer- Verlag, 1964.

- Kent, M.; Coker, P. Vegetation Description and Analysis: A Practical Approach, pp. 167-169. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1992.

- Svensson, M.S.; Nekaris, K.A.I.; Bearder, S.K.; Bettridge, C.; Butynski, T.; Cheyne, S.M.; Das, N.; de Jong, Y.; Luhrs, A.M.; Luncz, L.; et al. Sleep patterns, daytime predation and the evolution of diurnal sleep site selection in lorisiforms. Am J Phys Anthropol 2018, 166, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearder, S.K.; Nekaris, K.A.I.; Buzzell, C.A. Dangers in the night: Are some nocturnal primates afraid of the dark? In L. E. Miller (Ed.) Eat or be Eaten: Predator sensitive foraging among primates, pp 21–43. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Pascal, J.P.; Ramesh, B.R.; Franceschi, D.D. Wet evergreen forest types of the southern Western Ghats, India. Trop Ecol 2004, 45, 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Karuppusamy, S. Vegetation and Forest Types of the Western Ghats. In Biodiversity Hotspot of the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka, pp. 25-61. Apple Academic Press, 2024.

- Kumara, H.N.; Mahato, S.; Singh, M.; Molur, S.; Velankar, A.D. Mammalian diversity, distribution and potential key conservation areas in the Western Ghats. Cur Sci 2023, 124, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigwan, B.K.; Kulkarni, A.; Smrithy, V.; Datar, M.N. An overview of tree ecology and forest studies in the Northern Western Ghats of India. iForest 2024, 17, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, T.; Ganesan, R.; Devy, M.S.; Davidar, P.; Bawa, K.S. Assessment of plant biodiversity at a mid elevation evergreen forest of Kalakad–Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, Western Ghats, India. Cur Sci 1996, 71, 379–392. [Google Scholar]

- Murali, K.S.; Shankar, U.; Shaanker, R.U.; Ganeshaiah, K.N.; Bawa, K.S. Extraction of non-timber forest products in the forests of Biligiri Rangan Hills, India. 2. Impact of NTFP extraction on regeneration, population structure, and species composition. Economic Botany 1996, 252-269.

- Condit, R.; Ashton, P.S.; Baker, P.; Bunyavejchewin, S.; Gunatilleke, S.; Gunatilleke, N.; Hubbell, S.P.; Foster, R.B.; Itoh, A.; LaFrankie, J.V.; Lee, H.S. Spatial patterns in the distribution of tropical tree species. Science 2000, 288, 1414–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarapandian, S.M.; Swamy, P.S. Forest structure in the Western Ghats. Proc Indian Ac Sci 1999, 109, 517–529. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy, N. Climber diversity in tropical forests. J Trop Ecol 1999, 15, 315–332. [Google Scholar]

- Nekaris, K.A.I.; Jayewardene, J. Survey of the slender loris (Primates, Lorisidae) in Sri Lanka. J Zool 2003, 259, 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Gamage, S.; Marikar, F.; Groves, C.; Turner, C.; Padmalal, K.; Kotagama, S. Phylogenetic relationship among slender loris species (Primates, Lorisidae: Loris) in Sri Lanka based on mtDNA CO1 barcoding. Turkish J Zool 2019, 43, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandass, D.; Campbell, M.J.; Hughes, A.C.; Mammides, C.; Davidar, P. Edge disturbance drives liana abundance increase and alteration of liana–host tree interactions in tropical forest fragments. Ecol Evol 2017, 8, 4237–4251. [Google Scholar]

- Gamage, S.N.; Hettiarachchi, C.J.; Mahanayakage, C.A.; Padmalal, U.K.G.K.; Kotagama, S.W. Factors influencing site occupancy of Montane Slender Loris (Loris tardigradus nycticeboides) in Sri Lanka. Wildlanka 2015, 3, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Birot, H.; Campera, M.; Imron, M.A.; Nekaris, K.A.I. Artificial canopy bridges improve connectivity in fragmented landscapes: the case of Javan slow lorises in an agroforest environment. Am J Primatol 2020, 82, e23076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimloo, L.; Campera, M.; Imron, M.A.; Rakholia, S.; Mehta, A.; Hedger, K.; Nekaris, K.A.I. Habitat Use, Terrestriality and Feeding Behaviour of Javan Slow Lorises in Urban Areas of a Multi-Use Landscape in Indonesia. Land 2023, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladik, C.M.; Charles-Dominique, P.; Petter, J. Feeding strategies of five nocturnal prosimians in the dry forest of the west coast of Madagascar. In P. Charles-Dominique et al. (Eds.), Nocturnal Malagasy Primates, pp. 41–73. New York Academic Press, 1980.

- Petter, J.J.; Hladik, C.M. Observations on the home range and population density of Loris tardigradus in the forests of Ceylon. Mammalia 1970, 34, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramoniam, S. Some observations on the habits of the slender loris (Loris tardigradus). J Bombay Nat Hist Soc 1957, 54, 387–398. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.R. Sleep-related behavioural adaptations in free-ranging anthropoid primates. Sleep Med Rev 2000, 4, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.B.; Clark, D.A. Distribution and effects on tree growth of lianas and woody hemiepiphytes in a Costa Rican tropical wet forest. J Trop Ecol 1990, 6, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malizia, A.; Grau, H.R. Liana-host tree associations in a subtropical montane forest of north-western Argentina. J Trop Ecol 2006, 22, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepthy, K.B.; Sunil, J.; Manoj, V.S.; Dhanya, M.K.; Maya, T.; Kuriakose, K.P.; Krishnaprasad, K.P. A new report of the myrmecophilous root mealy bug Xenococcus annandalei Silvestri (Rhizoecidae: Hemiptera)-a devastating pest. Entomon 2017, 42, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Prathapan, K.D.; Chaboo, C.S. Biology of Blepharida-group flea beetles with first notes on natural history of Podontia congregata Baly, 1865 an endemic flea beetle from southern India (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Galerucinae, Alticini). ZooKeys 2011, 157, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Wainhouse, D.; Murphy, S.; Greig, B.; Webber, J.; Vielle, M. The role of the bark beetle Cryphalus trypanus in the transmission of the vascular wilt pathogen of takamaka (Calophyllum inophyllum) in the Seychelles. For Ecol Manag 1998, 108, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styrsky, J.D.; Eubanks, M.D. Ecological consequences of interactions between ants and honeydew-producing insects. Proc Royal Soc B 2007, 274, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankara, R.K.; Bhat, H.R.; Kulkarni, V.A.; Ramachandra, T.V. Mini Forest - An experiment to evaluate the adaptability of Western Ghats species for afforestation. Environ Conserv J 2011, 121, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra, T.V.; Setturu, B.; Rajan, K.S.; Subash Chandran, M.D. Modelling the forest transition in Central Western Ghats, India. Spatial Inf Res 2017, 25, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L. Beyond deforestation: restoring forests and ecosystem services on degraded lands. Science 2008, 320, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scientific Name | Type | Distribution | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gnetum edule | Woody lianas | India | 22.16 |

| Acacia caesia | A prickly climbing shrub | Indo-Malesia | 21.50 |

| Calycopteris floribunda | Scandent climbing shrubs | Indo-Malesia | 11.75 |

| Piper sarmentosum | Perennial herb with creeping rhizomes | India and Malesia | 11.08 |

| Derris scandens | Woody lianas | Indo-Malesia | 9.75 |

| Aspidopterys canarensis | Woody lianas | Endemic to Western Ghats | 5.87 |

| Ipomoea marginata | Extensive twiners | Paleotropics | 3.60 |

| Cissus repens | Creepers | Indo-Malesia | 3.34 |

| Ventilago maderaspatana | Climbing shrubs | Indo-Malesia | 2.54 |

| Cissus latifolia | Climbing shrubs | India and Sri Lanka | 2.14 |

| Piper nigrum | Glabrous climbers, climbing shrub | India and Sri Lanka | 1.34 |

| Bauhinia scandens | Woody Lianas | Indo-Malesia | 1.20 |

| Argyreiaelliptica sp. | Twiners | India and Sri Lanka | 0.93 |

| Piper mullesua | Woody Lianas | India | 0.93 |

| Calamus travancoricus | Very slender climbing canes | Endemic to Western Ghats | 0.67 |

| Unidentified | 0.67 | ||

| Mimosa diplotricha | Rambling shrubs, exotic climber | Native of Tropical America; a weed in India | 0.53 |

| Seasons/Time Duration | Height at Which the Loris Was Spotted (m) | Dry / Summer | S.W. Monsoon | Post Monsoon |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| February to May | June to November | December to January | ||

| Early night (19-22 hrs.) | Average | 7.35 ± 0.87 | 8.09 ± 1.26 | 7.58 ± 1.39 |

| Range | 30 - 0.0 | 30 - 1.21 | 30 - 0.6 | |

| n | 68 | 46 | 25 | |

| Mid night (22-01 hrs.) | Average | 11.36 ± 1.79 | 11.43 ± 1.66 | 8.35 ± 1.57 |

| Range | 31 - 0.0 | 30 - 0.0 | 25 - 0.0 | |

| n | 31 | 38 | 23 | |

| Late night (1-4 hrs.) | Average | 16.87 ± 2.82 | 11.17 ± 2.21 | 11.80 ± 1.81 |

| Range | 30 - 0.0 | 30 - 0.91 | 25 - 0.0 | |

| n | 16 | 22 | 19 | |

| Early dawn (4-6 hrs.) | Average | 16.22 ± 3.12 | 21 ± 4.58 | 11.42 ± 3.17 |

| Range | 28 - 2.13 | 30 - 10.00 | 30 - 2.00 | |

| n | 11 | 5 | 11 |

| Climbers the Loris Was Spotted on | Count | % |

|---|---|---|

| Acacia caesia | 44 | 33.59 |

| Gnetumedule sp. | 29 | 22.14 |

| Aspidopteryscanarensis sp. | 15 | 11.45 |

| Acacia caesia + Gnetumedule sp. | 11 | 8.40 |

| Acacia caesia + Calycopteris floribunda | 5 | 3.82 |

| Acacia caesia +Gnetumedule sp. + Aspidopteryscanarensis sp. | 4 | 3.05 |

| Calycopteris floribunda | 4 | 3.05 |

| Gnetumedule sp. + Aspidopteryscanarensis sp. | 4 | 3.05 |

| Acacia caesia + Aspidopteryscanarensis sp. | 3 | 2.29 |

| Derris scandens | 3 | 2.29 |

| Gnetumedule sp. + Calycopteris floribunda | 2 | 1.53 |

| Gnetumedule sp. + Derris scandens | 2 | 1.53 |

| Acacia caesia +Gnetumedule sp. + Aspidopteryscanarensis sp. | 1 | 0.76 |

| Derris scandens+ Calycopteris floribunda | 1 | 0.76 |

| Gnetumedule sp. + Cissusrepens sp. | 1 | 0.76 |

| Gnetumedule sp. + Piper sarmentosum | 1 | 0.76 |

| Ipomoea marginata | 1 | 0.76 |

| Scientific Name | % |

|---|---|

| Xylia xylocarpa | 15.08 |

| Dillenia pentagyna | 8.54 |

| Artocarpus hirsutus | 5.28 |

| Syzygium cumini | 5.03 |

| Holigarna arnottiana | 4.27 |

| Terminalia paniculata | 4.27 |

| Dead Tree | 4.02 |

| Terminalia bellirica | 4.02 |

| Aporosa cardiosperma | 3.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).