Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Justification

1.2. Objectives

1.2.1. Broad Objective

1.2.2. Specific Objectives

- 1)

- To determine the rectal temperature of finishing turkeys fed diets supplemented with riboflavin (vitamin B2) and/or protease enzyme.

- 2)

- To determine the pulse rate of finishing turkeys fed diets supplemented with riboflavin (vitamin B2) and/or protease enzyme.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Poultry Production

2.2. Heat Stress

2.3. Riboflavin (Vitamin B2)

2.4. Protease Enzymes

2.6. Physiological Parameters

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Location

3.2. Experimental Birds, Materials and Management

3.3. Source of Riboflavin and Protease Enzyme

3.4. Experimental Design

3.5. Experimental Diet

| Four experimental diets were used and they are: | |

| Diet 1 | basal diet without riboflavin and protease enzyme. |

| Diet 2 | basal diet with riboflavin 6mg/kg. |

| Diet 3 | basal diet with protease enzyme 1000mg/kg. |

| Diet 4 | basal diet with riboflavin and protease enzyme (6mg+1000mg)/kg. |

3.6. Data Collection

3.6.1. Rectal Temperature

3.6.2. Pulse Rate

3.6.3. Environmental Indicators in the Poultry House

2.7. Statistical Design and Analysis

| Gross composition of diets (%) | ||

| Ingredient | Pre-starter (0-4 weeks) | Starter (4-8 weeks) |

|

Maize |

42.50 |

50.00 |

| Soybean Meal | 40.70 | 36.00 |

| Fish Meal (72%) | 9.00 | 8.90 |

| Bone Meal | 4.50 | 3.00 |

| Limestone | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| *Vitamin/trace mineral Premix | 0.50 | 0.15 |

| Lysine | 0.10 | 0.20 |

| DL Methionine | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| Salt | 0.30 | 0.25 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Calculated analyses | ||

| Metabolizable Energy (Kcal/kg) | 2,840 | 2878.7 |

| Crude Protein (%) | 28.19 | 26.62 |

| Crude Fibre (%) | 3.00 | 3.97 |

| Ether Extract (%) | 3.78 | 2.89 |

| Calcium (%) | 2.16 | 1.39 |

| Phosphorus (%) | 0.86 | 0.67 |

| Lysine (%) | 1.91 | 1.89 |

| Methionine (%) | 0.88 | 0.68 |

| Arginine (%) | 1.82 | 1.71 |

|

T1 (Control ) |

T2 (Riboflavin ) |

T3 (Protease) |

T4 (Riboflavin and Protease) |

|

|

Supplemental levels of feed additives |

0 | 6mg/kg | 1000mg/k g |

6mg+1000mg/kg |

| Ingredient composition | ||||

| Maize | 555 | 555 | 555 | 555 |

| Soya Bean Meal | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 |

| Fish meal (72% CP) | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| Wheat offal | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Palm oil | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| Bone Meal | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Limestone | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| *Vitamin/mineral Premix | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Methaonine | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lysine | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Salt (NaCl) | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Total | 1000.00 | 1000.00 | 1000.00 | 1000.00 |

| Calculated analysis | ||||

| Metabolisable Energy (Kcal/kg) | 2952.92 | 2952.92 | 2952.92 | 2952.92 |

| Crude Protein (%) | 21.90 | 21.90 | 21.90 | 21.90 |

| Crude Fibre (%) | 3.70 | 3.70 | 3.70 | 3.70 |

| Ether Extract (%) | 3.39 | 3.39 | 3.39 | 3.39 |

| Phosphorus (%) | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Calcium (%) | 2.38 | 2.38 | 2.38 | 2.38 |

| Lysine (%) | 1.29 | 1.29 | 1.29 | 1.29 |

| Methionine (%) | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

|

T1 (Control ) |

T2 (Riboflavin ) |

T3 (Protease) |

T4 (Riboflavin and Protease) |

|

|

Supplemental levels of feed additives |

0 | 6mg/kg | 1000mg/k g |

6mg+1000mg/kg |

| Ingredient composition | ||||

| Maize | 645 | 645 | 645 | 645 |

| Soya Bean Meal | 205 | 205 | 205 | 205 |

| Fish meal (72% CP) | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Wheat offal | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 |

| Palm oil | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Bone Meal | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 |

| Limestone | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| *Vitamin/mineral Premix | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Methaonine | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lysine | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Salt (NaCl) | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Total | 1000.00 | 1000.00 | 1000.00 | 1000.00 |

| Calculated analysis | ||||

| Metabolisable Energy (Kcal/kg) |

3030.64 | 3030.64 | 3030.64 | 3030.64 |

| Crude Protein (%) | 18.31 | 18.31 | 18.31 | 18.31 |

| Crude Fibre (%) | 3.45 | 3.45 | 3.45 | 3.45 |

| Ether Extract (%) | 2.84 | 2.84 | 2.84 | 2.84 |

| Phosphorus (%) | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Calcium (%) | 2.19 | 2.19 | 2.19 | 2.19 |

| Lysine (%) | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 |

| Methionine (%) | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.56 |

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

4.1.1. Effect of Feed Supplementation with Riboflavin and Protease Enzyme on Rectal Temperature of Finishing Turkeys

4.1.2. Effect of Feed Supplementation with Riboflavin and Protease Enzyme on Pulse Rate of Finishing Turkeys

4.1.3. Result of Ambient Temperature and Relative Humidity of the Poultry House

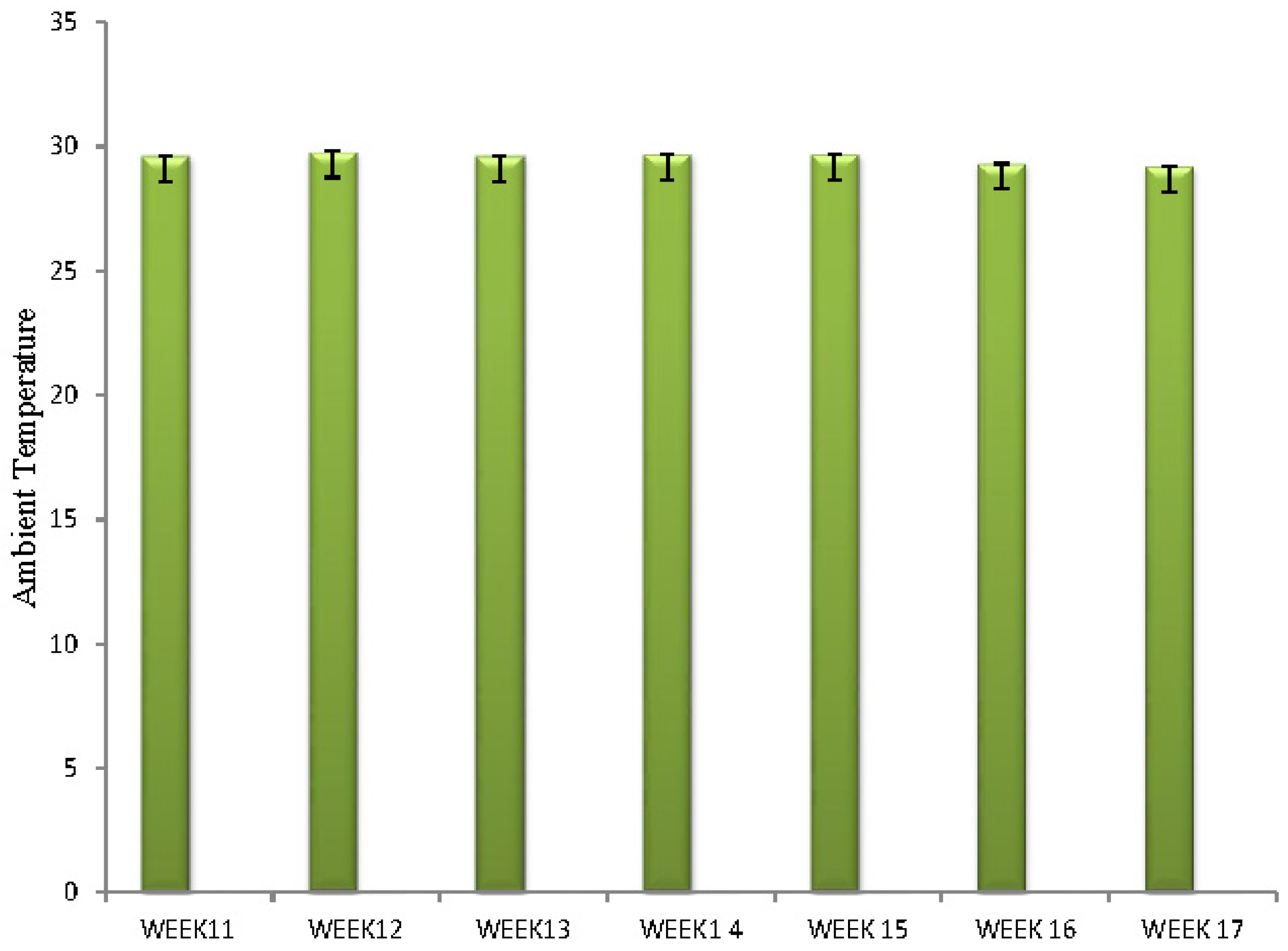

4.1.3.1. Ambient Temperature

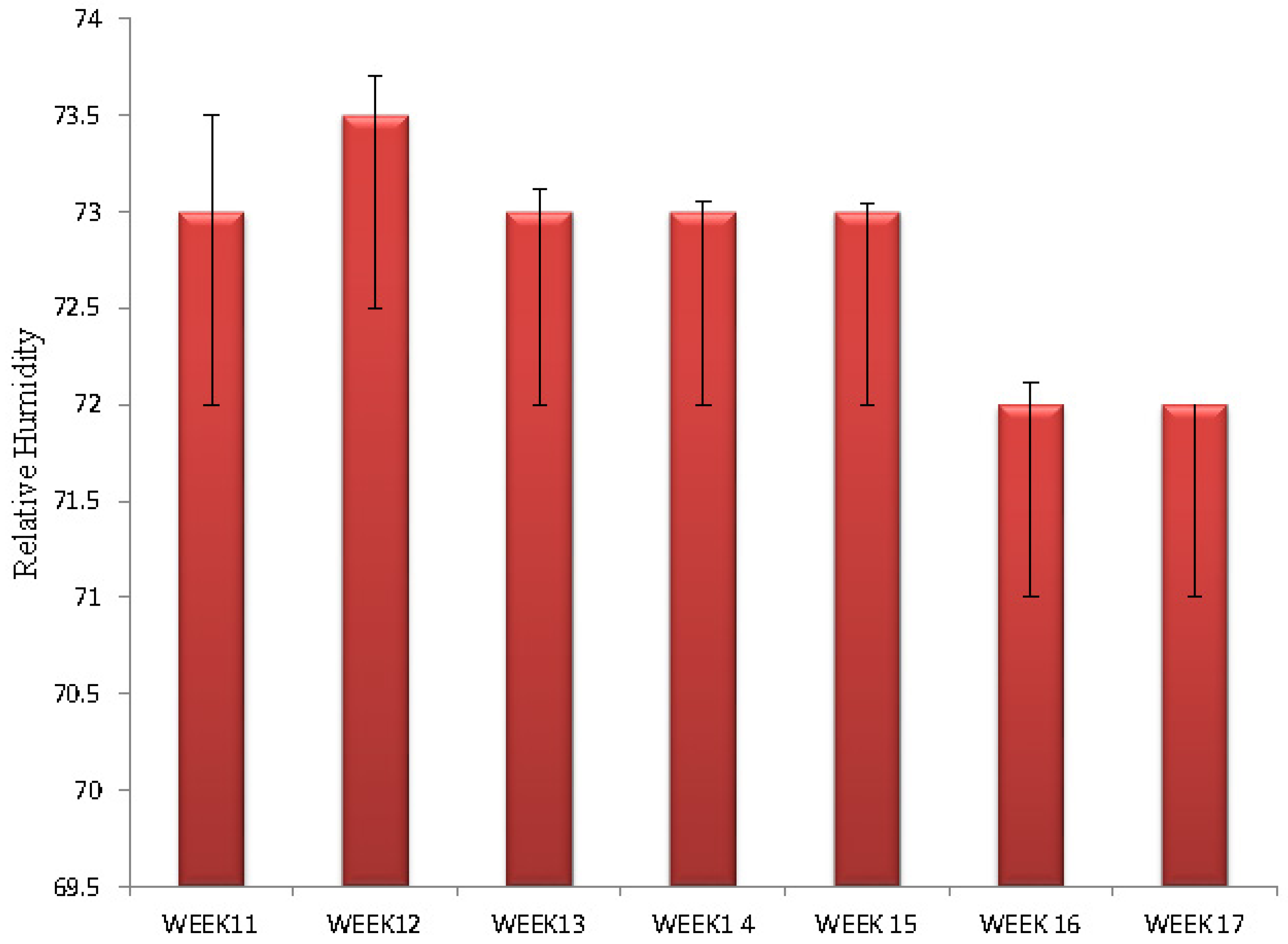

4.1.3.2. Relative Humidity

4.2. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Recommendation

References

- A.w TY, Jones DP, McCormick DB. (1983). Uptake of riboflavin by isolated rat liver cells. Journal Nutrition 113:1249-54. [CrossRef]

- Ajakaiye J.J., Ayo J.O. and Ojo S.A. (2010). Effects of heat stress on some blood parameters and egg production of Shika Brown layer chickens transported by road. Biological Research 43:183-189. [CrossRef]

- Ajakaiye, J.J; Perez-Bello, A; Mollineda-Trujillo, A. (2011). Impact of heat stress on egg quality hens supplemented with I-ascorbic and dl-tocopherol acetate. Veterinrski Arhiv 81 (1), 119-132.

- Altan, O.; Altan A.; Oguz I.; Pabuccuoglu, A.; and Konyalioglu, S. (2000). Effects of heat stress on growth, some blood variables and lipid oxidation in broilers exposed to high temperature at an early age. British Poultry Science, 41:489-493. [CrossRef]

- Anonymous, (1987). Animal Houses - rules for isolation and heating TS 5087, Turk Standards Institute. NecatiBeyEvanue No: 112, Bakanliklar-Ankara. pp. 1-12 (in Turkish).

- Antonelli, G.; Turriziani, O. 2012. Antiviral therapy: Old and current issues. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 40, 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Austic, R.E., (1985). Feeding poultry in hot and cold climates. In: Stress Physiology in Livestock.Vol. 3. Yousef, M.K. (Ed.). CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL., pp: 123-136.

- Ayo, J. O., Oladele, S. B., Fayomi, A., Jumbo, S.D., and Hambolu, J.O. (1998). Body temperature, respiration and heart rate in Red Sokoto goat during harmattan season. Bulletin of Animal Health Production of Africa, 46: 161-166.

- Barrett, A.J., and McDonald, J.K. (1986). Nomenclature: Protease, proteinase and peptidase. Biochemical Journal 237, 935. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.J.; McDonald, J.K. (1986). Nomenclature: Protease, proteinase and peptidase. Biochemical Journal, 237, 935. [CrossRef]

- Bedanova I., Voslarova E., Vecerek V., Pistekova V., Chloupek P. (2006). Effects of reduction in floor space during crating on haematological indices in broilers. Berlin und Munchener Tierarztliche Wochenschrift 119: 17-21.

- Bianca, W. K., (1976). The Significance of Meteorology in Animal Production. International Journal of Biometeorology, 20: 139-156. [CrossRef]

- Borges, S.A., da Silva A.V.F., and Mairoka A., (2007). Acid-base balance in broilers. World’s Poultry Science Journal, 63: 73-81.

- Borges, S.A., da Silva A.V.F., Ariki J., Hooge D.M. and Cummings K.R., (2003). Dietary Electrolyte Balance for Broiler Chickens Exposed to Thermoneutral or Heat-Stress Environments. Poultry Science 82: 428-435. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. J., Brown, J. E., and Butts, W. T. (1973). Evaluating relationship among immatured measure of size, shape and performance of beef bulls.11. The relationships between immature measures of size shape and feedlot traits in young bulls. Journal of Animal Science, vol. 36, p. 1021-1023.

- Campbell, G. L., Bedford M. R. (1992). Enzyme application for monogastric feeds: a review. Canadian Journal of Animal Science, 72, 449-466. [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, A. D., Sapra, K.L., and Sharma R. K. (1972). Shank length, growth and carcass quality in broiler breeds of poultry. Industrial and Veterinary Journal, 1972, vol. 49, no. ,p. 506-511.

- Ciftci, M., Nihatertas, O., and Guler, T. (2005). Effects of vitamin E and vitamin C dietary supplementation on egg production and egg quality of laying hens exposed to a chronic heat stress. Revue de Médecine Véterinaire 156 (Suppl. II), 107-111.

- Cooper, M. A., and Washburn, K. W. (1998). The relationships of body temperature to weight gain, feed consumption, and feed utilization in broilers under heat stress. Poultry Science 77:237–242. [CrossRef]

- Craik, C.S.; Page, M.J.; Madison, E.L. (2011). Proteases as therapeutics. Biochemical Journal 435, 1–16.

- Daghir, N. J. (2009). Nutritional strategies to reduce heat stress in broilers and broiler breeders. Lohmann information 44: 6-15.

- Daghir, N.J. (2008). Poultry Production in Hot Climates. 2nd Edition, CAB International, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK. Pages: 387.

- Dai, S.F.; Gao, F.; Xu, X.L.; Zhang, W.H.; Song, S.X.; Zhou, G.H. (2012). Effects of dietary glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid on meat colour, pH, composition, and water- holding characteristic in broilers under cyclic heat stress. British Poultry Science 53, 471–481. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Palai, T. K.; Mishra, S. R.; Das, D.; Jena, B. (2011). Nutrition in relation to diseases and heat stress in poultry. Veterinary World, 4:429-432. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, T.M. (2002). Textbook of Biochemistry with Clinical Correlations, 5th ed.; Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA.

- El Bousy, A.R. & Van Marle, A.L. (1978). The effects of climate on poultry physiology in tropics and their improvement. World’s Poultry Science Journal 34, 155-170. [CrossRef]

- Emery, D. A., Vohra P., Ernst, R. A., and Morrison, S. R. (1984). The effect of cyclic and constant ambient temperatures on feed consumption, egg production, egg weight, and shell thickness of hens. Poultry Science 63:2027–2035. [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi G, Ferrari G, Verri A, Casirola D, Orsenigo M.N, Laforenza U. (2000). Riboflavin phosphorylation is the crucial event in riboflavin transport by isolated rate enterocytes. Journal of Nutrition; 130:2556-61. [CrossRef]

- Gencoglan, S., Gencoglan C., and Akyuz, A. (2009) Supplementary heat requirements when brooding tom turkey poults. South African Journal of Animal Science, 39 (1). [CrossRef]

- Geraert, P. A., J. C. F. Padilha and S. Guillaumin. (1996). Metabolic and endocrine changes induced by chronic heat exposure in broiler chickens: biological and endocrinological variables. British Journal of Nutrition, 75:205-216. [CrossRef]

- Gu, X. H., R. Du and L. Fang. (1999). Effect of humidity on rectal temperature, plasma t3 and insulin level in broilers under high ambient temperature. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 32:105-107.

- Gueye, E. F., Ndiaye, A., and Branckaert, R. D. S. (1998). Prediction of body weight on the basis of body measurement in mature indigenous chickens in Senegal. Livestock Research for Rural Development, vol. 10, no. 3.

- Halliwell, B.E. and J.M.C. Gutteridge, (1989). Lipid peroxidation: A radical chain reaction. In: Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. 2nd Edn., Oxford University Press, New York, pp: 188-218.

- Henken, A. M., Groote Schaarsberg A.M. J., and Nieuwland M. G. B. (1983). The effect of environmental temperature on immune response and metabolism of the young chicken. Effect of environmental temperature on the humoral immune response following injection of sheep red blood cells. Poultry Science 62:51–58.

- Holik, V. (2009). Management of laying hens to minimize heat stress. Lohmann Information, 44:16-29.

- Ibe, S. N. (1989). Measurement of size and confirmation in commercial broilers. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics, vol. 106, p. 461-469. [CrossRef]

- Ibe, S. N., and Ezekwe, A. G. (1994). Quantifying size and shape differences between Muturu and N‘Dama breeds of cattle. Nigerian Journal of Animal Production, vol. 21, p.51-58. [CrossRef]

- Ilori, B.M, Peters, S.O, Yakubu, A, Imumorin, I.G, Adeleke, M.A, Ozoje, M.O, Ikeobi, C.O.N, and Adebambo, O.A. (2012). Physiological adaptation of local, exotic and crossbred turkeys to the hot and humid tropical environment of Nigeria. ActnAgriculturaeScandinavica,Section A-Animal Science.

- Imik, H.; Atasever, M.A.; Urgar, S.; Ozlu, H.; Gumus, R.; Atasever, M. (2012). Meat quality of heat stress exposed broilers and effect of protein and vitamin E. British Poultry Science, 53, 689-698. [CrossRef]

- Jisha, V. N.; Smitha, R. B.; Pradeep, S. (2013). Versatility of microbial proteases. Advances in Enzyme Research, 1(3): 39-51. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P .C., Panda, B., and Joshi, B. C. (1980). Effect of ambient temperature on semen characteristics of White Leghorn male chickens. Indian Veterinary Journal, 57, 52–56.

- Kirk, O.; Borchert, T.V.; Fuglsang, C.C. (2002). Industrial enzyme applications. Current Opinion in Biotechnolonogy, 13, 345–351.

- Knowles T.G., and Broom D.M. (1990). The handling and transport of broilers and spent hens. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 28: 75-91. [CrossRef]

- Kohne, H. J., and Jones, J. E. (1976). The relationship of circulating levels of estrogens, corticosterone and calcium to production performance of adult turkey hens under conditions of increasing ambient temperature. Poultry Science 55:277–285. [CrossRef]

- Konca, Y. (2001). Turkey Brooding. Agricultural Research and Education Coordination (TAYEK/TYUAP), Proc. Animal Working Group Meeting in 2001. Ege Agricultural Research Institute Directorate, 27-29 March, Izmir, Publ. No: 100. pp. 21-31. (in Turkish).

- Lara L. J., RostagnoM. H. (2013). Impact of Heat Stress on Poultry Production. Animals 3, 356-369.

- Leenstra, F. and A. Cahaner. (1991). Genotype by environment interactions using fast growing, lean or fat broiler chickens, originating from the Netherlands and Israel, raised at normal or low temperature. Poultry Science 70:2028-2039.

- Leeson, S. and Summers, J.D. (1991). Commercial Poultry Nutrition. University books, Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

- Leeson S.; Caston L. J.; Yungblat D. (1996). Adding roenzyme to wheat diets of chickens and turkey broilers. Journal of Applied Poultry Research, vol. 5, 167-172. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yi, L.; Marek, P.; Iverson, B.L. (2013). Commercial proteases: Present and future. FEBS Letters 587, 1155–1163. [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Y. (1999). Studies on the effect of heat stress on performance and meat quality of broilers and anti-stress effect of riboflavin. Ph. D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing.

- Lin, H., E. Decuypere and J. Buyse. (2006). Acute heat stress induces oxidative stress in broiler chickens. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part A. 144:11-17. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H., H. F. Zhang, H. C. Jiao, T. Zhao, S. J. Sui, X. H. Gu, Z. Y. Zhang, J. Buyse and E. Decuypere. (2005a). The thermoregulation response of broiler chickens to humidity at different ambient temperatures I. One-week-age. Poultry Science 84:1166-1172.

- Lin, H., H. F. Zhang, R. Du, X. H. Gu, Z. Y. Zhang, J. Buyse and E. Decuypere. (2005b). The thermoregulation response of broiler chickens to humidity at different ambient temperatures I. Fourweek- age. Poultry Science 84:1173-1178.

- Lu, Q. Wen, J. Zhang, H. (2007). Effect of chronic heat exposure on fat deposition and meat quality in two genetic types of chicken. Poultry Science 86, 1059–1064.

- MacLeod, M.G. (2004). Climate-Nutrition Interactions in Poultry.1rst Annual Confrence , FVM., Moshtohor. Roslin Institute (Edinburgh), Scotland EH25 9PS 1-21.

- Mashaly, M. M., Hendricks, G. L., Kalama, M. A., Gehad A. E., Abbas, A. O., and Patterson, P. H. (2004). Effect of Heat Stress on Production Parameters and Immune Responses of Commercial Laying Hens1. Poultry Science 83:889–894. [CrossRef]

- McCormick D. B., Zhang Z. (1993). Cellular assimilation of water soluble vitamin in mammal: riboflavin, B6, biotin and C. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biologic and Medicine 202:265-70.

- McCormick DB. The fate of riboflavin in the mammal. Nutrition Reviews 1972;30:75–9. [CrossRef]

- McCracken, K. G., Paton, D. C., and Afton, A. D. (2000). Sexual size dimorphism of the musk duck. Wilson Bulletin, vol. 112, no. 4, p. 457-466. [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, C. D., Bramwell, R.K., Wilson, J. L., and Howarth, B. Jr. (1995). Fertility of male and female broiler breeders following exposure to elevated ambient temperatures. Poultry Science 74:1029–1038. [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, C.D.; Bramwell, R.K.; Wilson, J.L.; and Howarth, B. (1995). Fertility of male and female broiler breeders following exposure to an elevated environmental temperature. Poultry Science 74, 1029–1038. [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, C.D.; Hood, J.E.; and Parker, H.M. (2004). An attempt at alleviating heat stress infertility in male broiler breeder chickens with dietary ascorbic acid. International Journal of Poultry Science 3, 593–602.

- McKee, S. R., and Sams, A. R. (1997). The Effect of Seasonal Heat Stress on Rigor Development and the Incidence of Pale, Exudative Turkey Meat. Poultry Science 76:1616–1620. [CrossRef]

- Miles, R.D. (1999). Understanding heat stress in poultry and strategies to improve production through good management and maintaining nutrient and energy intake. Nutrition and Management Department of Dairy and Poultry Sciences University of Florida Gainesville. pp. 1-20.

- Mitchell M. A., Kettlewell P. J. (1998). Physiological stress and welfare of broiler chickens in transit: Solutions not problems! Poultry Science 77: 1803-1814.

- Mittal, J. P. and Ghosh, P. K. (1979). Body temperature, respiration and pulse rate in Corriedale, Marwari and Magra Sheep in the Rajasthan desert. Journal of Agricultural Science (Cambridge), 95: 587-591. [CrossRef]

- Monsi, A. (1992). Appraisal of interrelationships among live measurements at different ages in meat type chickens. Nigerian Journal of Anim.al Production, vol. 19, no.1&2, p.15- 24.

- Mótyán, J.A; Tóth, F.,and Tőzsér, J. (2013). Research Applications of Proteolytic Enzymes in Molecular Biology Biomolecules, 3, 923-942. [CrossRef]

- Muiruri, H. K., and Harrison, P. C. (1991). Effect of roost temperature on performance of chickens in hot ambient environments. Poultry Science. 70:2253–2258. [CrossRef]

- Mujahid, A., Y. Yoshiki, Y. Akiba and M. Toyomizu, (2005). Superoxide radical production in chicken skeletal muscle induced by acute heat stress. Poultry Science, 84: 307-314. Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Ranieri, M. S.; and Bernabucci, U. (2010). Effects of climate changes on animal production and sustainability of livestock systems. Livestock Science 130, 57–69.

- Neurath, H.; Walsh, K.A. (1976). Role of proteolytic enzymes in biological regulation (a review). Proceedings of National Academy of Science, USA, 73, 3825–3832. [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C.J., Saville-Weeks C. (1993). Poultry handling and transport. In: Livestock handling and transport. GRANDINT (ed) Wallingford Oxon UK: CAB International pp 273-287.

- Nienaber, J. A., and Hahn, G. L. (2007). Livestock production system management responses to thermal challenges. International Journal of Biometeorology. 52, 149–157. [CrossRef]

- North, M.O., (1984). Commercial Chicken Production Manual: Poultry Housing. AVI Publishing Company, Inc. Westport, Connecticut. pp. 148-177.

- Northcutt, J. K., E. A. Foegeding and F. W. Edens. (1994). Waterholding properties of thermally preconditiond chicken breast and leg meat. Poultry Science 73:308-316. [CrossRef]

- Ogah, D. M. (2011). Assessing Size and Conformation of the Body of Nigerian Indigenous Turkey. Slovak Journal of Animal Science, 44 (1): 21-27.

- Ogah, D.M., Musa, I. S., Yakubu, A., Momoh, M.O. and Dim, N. I. (2009). Variation in morphological traits of geographical separated population of indigenous muscovy duck (Cairina moschata) in Nigeria. Proceeding of 5th International Poultry Conference Taba Egypt, p. 46-52.

- Ohkawa H. Ohishi N. Yagi K.A. (1982). Simple method for microdetermination of flavin in human serum and whole blood by high performance liquid chromatography. Biochemistry International 4:187 94.

- Osman, A. M. A., E. S. Tawfik, F. W. Klein and W. Hebeler. (1989). Effect of environmental temperature on growth, carcass traits and meat quality of broilers of both sexes and different ages. 1. Growth. Archiv fur Geflugelkunde 53:168-175.

- Park, S.O., Hwangbo, J., Ryu, C.M., Park, B.S., Chae, H.S., Choi, H.C., Kang, H.K., Seo, O.S., and Choi, Y.H. (2013). Effects of extreme heat stress on growth performance, lymphoid organ, IgG and cecum microflora of broiler chickens. International Journal of Agricultural Biology, 15: 1204–1208.

- Powers, H. J. (2003). Riboflavin (vitamin B2) and health. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 77:1352–60.

- Ramnath, V., Rekha, P. S., and Sujatha, K. S. (2008). Amelioration of heat stress induced disturbances of antioxidant defense system in chicken by Brahma Rasayana. Evidence- Based Complementary and Alternative Medecine 5 (Suppl. I), 77-84. [CrossRef]

- Rani, K.; Rana, R.; Datt, S. (2012). Review on latest overview of proteases. International Journal Current Life Science 2, 12–18.

- Rao, M. B., Tanksale, A. M., Ghatge, M. S. and Deshpande, V. V. (1998). Molecular and biotechnological aspects of microbial proteases. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 62, 597-635. [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.B.; Tanksale, A.M.; and Ghatge, M.S.; Deshpande, V.V. (1998). Molecular and biotechnological aspects of microbial proteases. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 62, 597–635. [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.B.; Tanksale, A.M.; Ghatge, M.S.; Deshpande, V.V. (1998). Molecular and biotechnological aspects of microbial proteases. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 62, 597–635. [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, N.D.; and Barrett, A.J. (1993). Evolutionary families of peptidases. Biochemical Journal 290, 205–218. [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, N.D.; Barrett, A.J.; and Bateman, A. (2012). MEROPS: The database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Research 40, D343–D350. [CrossRef]

- Ray, A. (2012). Protease enzyme- potential industrial scope. International Journal Technology 2, 1–4.

- Renaudeau, D.; Collin, A.; Yahav, S.; de Basilio, V.; Gourdine, J. L.; and Collier, R.J. (2012). Adaptation to hot climate and strategies to alleviate heat stress in livestock production. Animal, 6, 707–728. [CrossRef]

- Rozenboim, I., Tako, E., Gal-Garber, O., Proudman, J. A and Uni, Z. (2007). The effect of heat stress on ovarian function of laying hens Poultry Science 86:1760–1765.

- Sahin, K. and O. Kucuk, (2003). Heat stress and dietary vitamin supplementation of poultry diets. Nutr. Abstr. Rev. Ser. B. Livestock Feeds Feeding, 73: 41R-50R. [CrossRef]

- Sahin, K., and Kucuk O. (2001). Effects of vitamin C and vitamin E on performance, digestion of nutrients and carcass characteristics of Japanese quails reared under chronic heat stress (34 °C). Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 85, 335-341.

- Sahin, K., N. Sahin, M. Onderci, S. Yaralioglu and O.Kucuk, (2001). Protective role of supplemental vitamin E on lipid peroxidation, vitamins E, A and some mineral concentrations of broilers reared under heat stress. Veterinary Medicine, Czech Republic, 46: 140-144. [CrossRef]

- Sandercock, D. A., R. R. Hunter, G. R. Nute, M. A. Mitchell and P. M. Hocking. (2001). Acute heat stress-induced alterations in blood acid/base status and skeletal muscle membrane integrity in broiler chickens at two ages: implications for meat quality. PoultryScience 80:418-425. [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.R., DeShazer, J.A., and Roller, W.L. (1983). Effect of thermal and gaseous environment on livestock. In: Ventilation of Agricultural Structures. EdsHellickson, M. A. and Walker, J.N., The American Society of Agricultural Engineers, 2950 Niles Road St. Joseph, Michigan 49085- 9659, USA. pp.121-165.

- Selye, H. (1976). Forty years of stress research: principal remaining problems and misconceptions.

- Seskevicience, J.; Jeroch, H.; Danieke, S.; Gruzauskas, R.; Volker, L.; Broz, J. (1999). Feeding value of wheat and wheat-based diets with different content of soluble pentosans when fed to broiler chickens without or with enzyme supplementation. Archive Furgeflugelkunde, vol. 63, pp. 129-132. [CrossRef]

- Shafee, N., Aris, S. N., Rahman, R. Z. A., Basri, M. and Salleh, A. B. (2005). Optimization of Environmental and Nutritional Conditions for the Production of Alkaline Protease by a Newly Isolated Bacterium Bacillus cereus Strain 146. Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 1, 1-8.

- Shahin, K.A. (1996). Analysis of muscle and bone weight variation in an Egypt strain of Peking ducklings. Annual Zootechnology, vol. 45, no. 2, p. 173-184.

- Singer, T. P.; Kenny, W. C. (1974). Biochemistry of covalently-bound flavins. Vitamins and Hormones, 32:1-45.

- Smits, C. H. M.; Annison G. (1996). Non-starch plant polysaccharide in broiler nutrition towards a physiologically valid approach to their determination. World’s Poultry Science Journal, vol. 52, pp. 203-206. [CrossRef]

- Sumantha, A., Sandhya, C., Szakacs, G., Soccol, C.R. and Pandey, A. (2005). Production and partial purification of a neutral metalloprotease by fungal mixed substrate fermentation. Food Technology and Biotechnology, 43, 313-319.

- Vecerek V., Grbalova S., Voslarova E., Janackova B., and Melena M. (2006). Effects of travel distance and the season of the year on death rates of broilers transported to poultry processing plants. Poultry Science 85: 1881-1884. [CrossRef]

- White HB III, Merrill AH Jr. Riboflavin-binding proteins. Annual Review of Nutrition 1988;8: 279–99.

- Whitehead, C. C., Bollengier-Lee, S., Mitchell, M. A., and Williams, P. E.V. (1998). Alleviation of depression in egg production in heat stressed laying hens by vitamin E. In Proceedings of 10th European Poultry Conference, Jerusalem, Israel. Pages 576– 578.

- Yakubu, A., Ogah, D. M., and Idahor, K. O. (2009). Principal component analysis of the morphostructural indices of White Fulani cattle. Trakia Journal Science, vol. 7, p. 67- 73.

- Zanette D, Monaco HL, Zanotti G, Spadon P. (1984). Crystallisation of hen egg white riboflavin-binding protein. Journal of Molecular Biology 180:1185–7.

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Jia, G.Q.; Zuo, J.J.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, J.; Ren, L.; Feng, D.Y. (2012). Effects of constant and cyclic heat stress on muscle metabolism and meat quality of broiler breast fillet and thigh meat. Poultry Science 91, 2931–2937. [CrossRef]

| Age (weeks) | Control | Basal diet with riboflavin (6mg/kg) | Basal diet with protease enzyme (1000mg/kg) |

Basal diet with riboflavin and protease enzyme (6mg/kg+1000mg /kg) |

| 11 | 40.931 ± 0.099 | 41.081 ± 0.099 | 40.975 ± 0.099 | 40.875 ± 0.099 |

| 12 | 41.131 ± 0.099 | 40.919 ± 0.099 | 40.794 ± 0.099 | 40.869 ± 0.099 |

| 13 | 40.931 ± 0.099 | 40.938 ± 0.099 | 40.950 ± 0.099 | 40.788 ± 0.099 |

| 14 | 40.969 ± 0.099 | 41.113 ± 0.099 | 40.931 ± 0.099 | 41.063 ± 0.099 |

| 15 | 40.925 ± 0.099 | 40.875 ± 0.099 | 40.919 ± 0.099 | 41.119 ± 0.099 |

| 16 | 40.525 ± 0.099 | 40.594 ± 0.099 | 40.644 ± 0.099 | 40.588 ± 0.099 |

| 17 | 40.350 ± 0.099 | 40.431 ± 0.099 | 40.419 ± 0.099 | 40.425 ± 0.099 |

| Source | Degree of Freedom | Mean-square | * |

| Treatment | 3 | 0.854 | NS |

| Week | 6 | 0.000 | *** |

| Treatmeat * Week | 18 | 0.552 | NS |

| Error | 420 |

| Age (week) | Control | Diet with riboflavin (6mg/kg) |

Diet with protease enzyme (1000mg/kg) |

Diet with riboflavin and protease enzyme (6mg/kg+100 0mg/kg) |

| 11 | 167.50ab±1.708 | 162.500bc±1.708 | 164.750b±1.708 | 171.250defg±1. 708 |

| 12 | 153.25defg±1.708 | 157.750cd±1.708 | 157.500cde±1.708 | 156.000defg±1. 708 |

| 13 | 154.50defg±1.708 | 151.000fg±1.708 | 156.000defg±1.708 | 156.000defg±1. 708 |

| 14 | 156.75def±1.708 | 157.250de±1.708 | 155.750defg±1.708 | 153.500defg±1. 708 |

| 15 | 155.000defg±1.708 | 156.313def±1.70 8 |

155.000efg±1.708 | 154.500defg±1. 708 |

| 16 | 154.250defg±1.708 | 152.750defg±1.70 8 |

151.750g±1.708 | 155.500defg±1. 708 |

| 17 | 154.750defg±1.708 | 154.500defg±1.70 8 |

150.250a±1.708 | 153.500defg±1. 708 |

| Source | Degree of Freedom | Standard Error of Mean |

| Treatment | 3 | 40.437 NS |

| Week | 6 | 1343.336 *** |

| Treatment * week | 18 | 85.062 * |

| Error | 420 | 46.703 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).