Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

11 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design, Animals and Housing

2.2. Diet

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance

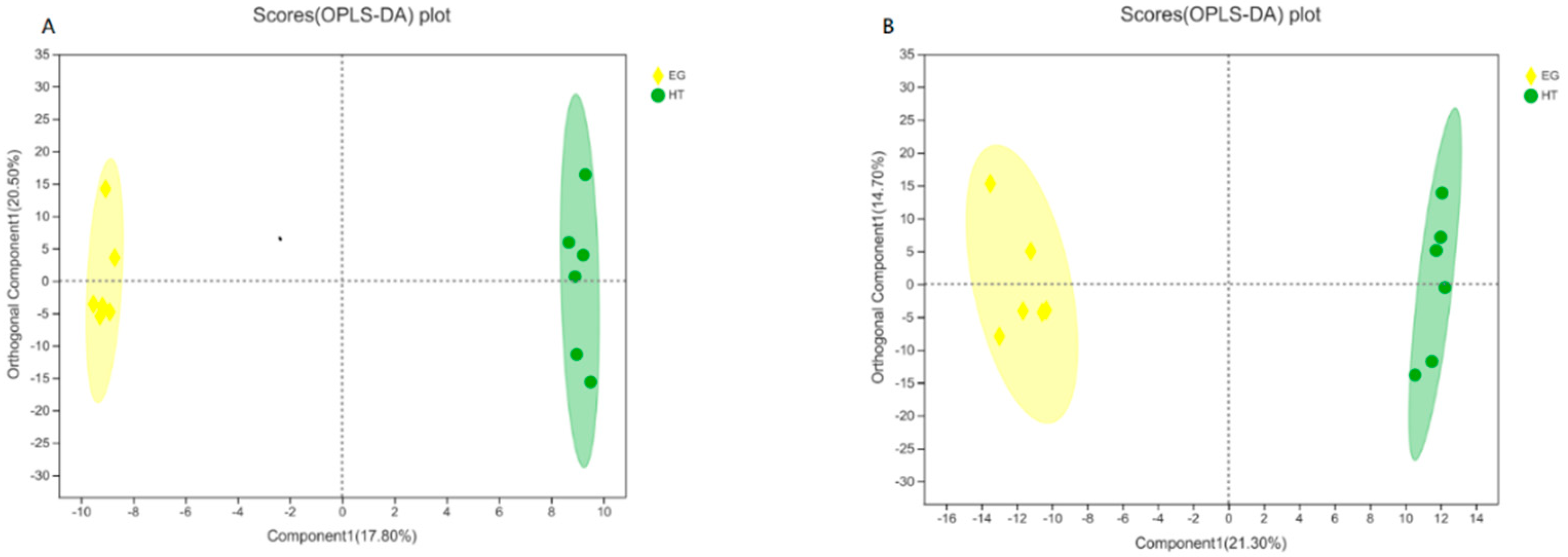

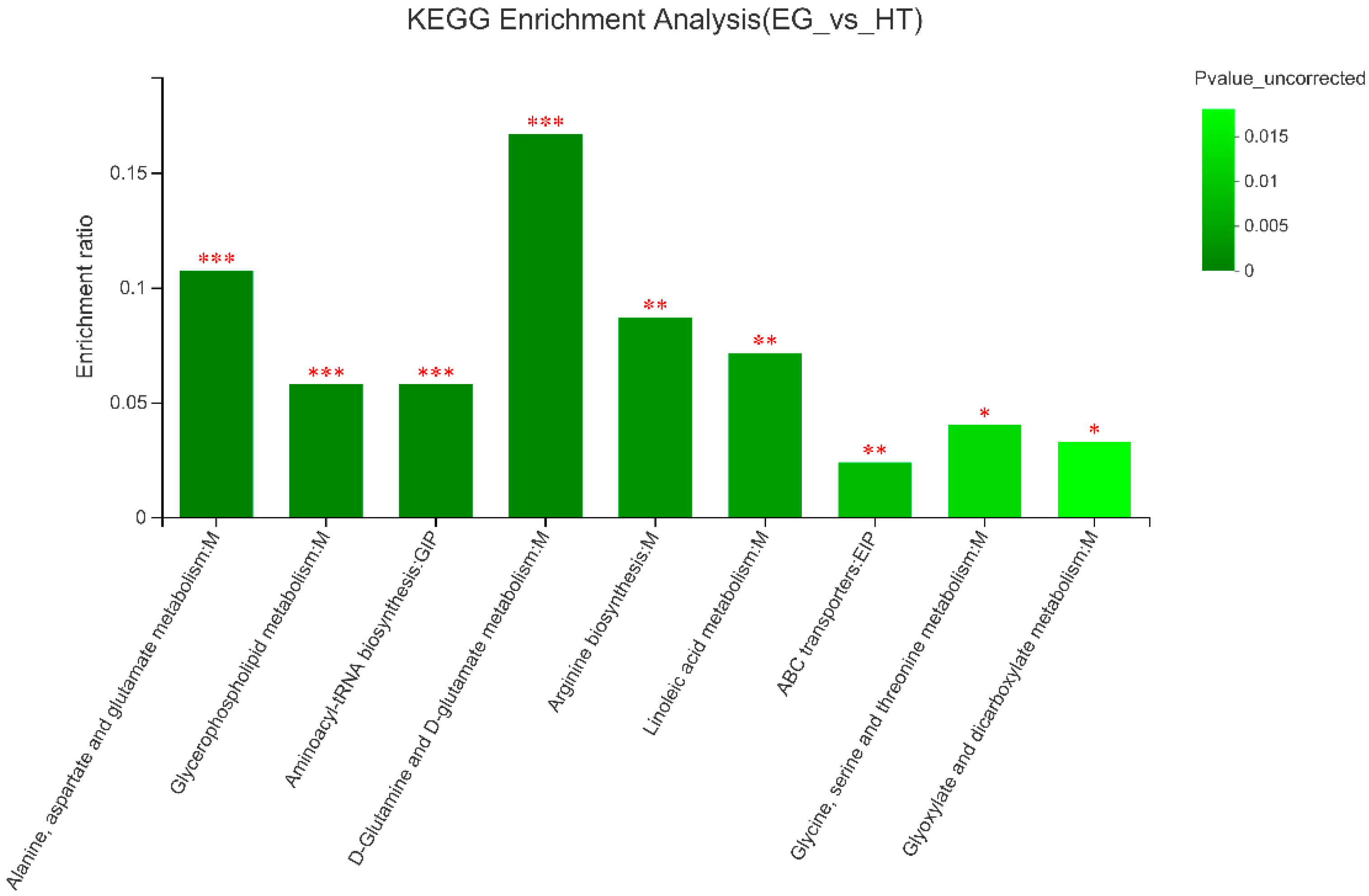

3.2. LC-MS Analysis

| Metabolites | VIP(HS&EG) | P-value | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citric acid | 5.92 | 0.04 | ↑ |

| L-aspartic acid | 6.94 | 0.02 | ↑ |

| L-glutamine | 3.91 | 0.02 | ↑ |

| L-proline | 5.82 | 0.03 | ↑ |

| (R)-(+)-2-Pyrrolidone-5-carboxylic acid | 5.23 | 0.02 | ↑ |

| Phosphatidylcholine (14:0/20:4[8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z]) | 3.94 | 0.05 | ↑ |

| 9,10,13-trihydroxy-octadecadienoic acid | 4.69 | 0.002 | ↑ |

| Phosphatidylcholine (22:6[4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z]) | 5.35 | 0.05 | ↓ |

| Phosphatidylserine (18:0/20:0) | 3.59 | 0.02 | ↓ |

| LysoPC (16:0) | 10.43 | 0.005 | ↓ |

| LysoPC (20:4[5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z]) | 3.56 | <0.001 | ↓ |

| LysoPC (18:1[9Z]) | 5.97 | 0.03 | ↓ |

| LysoPC (17:0) | 8.95 | 0.002 | ↓ |

| LysoPC (18:0) | 6.93 | 0.02 | ↓ |

| LysoPC (P-18:1[9Z]) | 8.38 | <0.001 | ↓ |

| LysoPC (20:1[11Z]) | 3.56 | 0.02 | ↓ |

| LysoPC (P-18:0) | 5.80 | 0.03 | ↓ |

3.3. Blood Paraments

| Items2 | 0 | 400 | 800 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.80a ± 0.11 | 3.57b ± 0.52 | 3.21b ± 0.26 | <0.01 |

| Free fatty acids (μmol/L) | 106.68a ± 3.24 | 89.06b ± 1.46 | 106.68b ± 3.24 | <0.01 |

| Corticosterone (ng/mL) | 15.78a ± 0.51 | 12.14b ± 0.72 | 12.14 b ± 1.22 | 0.02 |

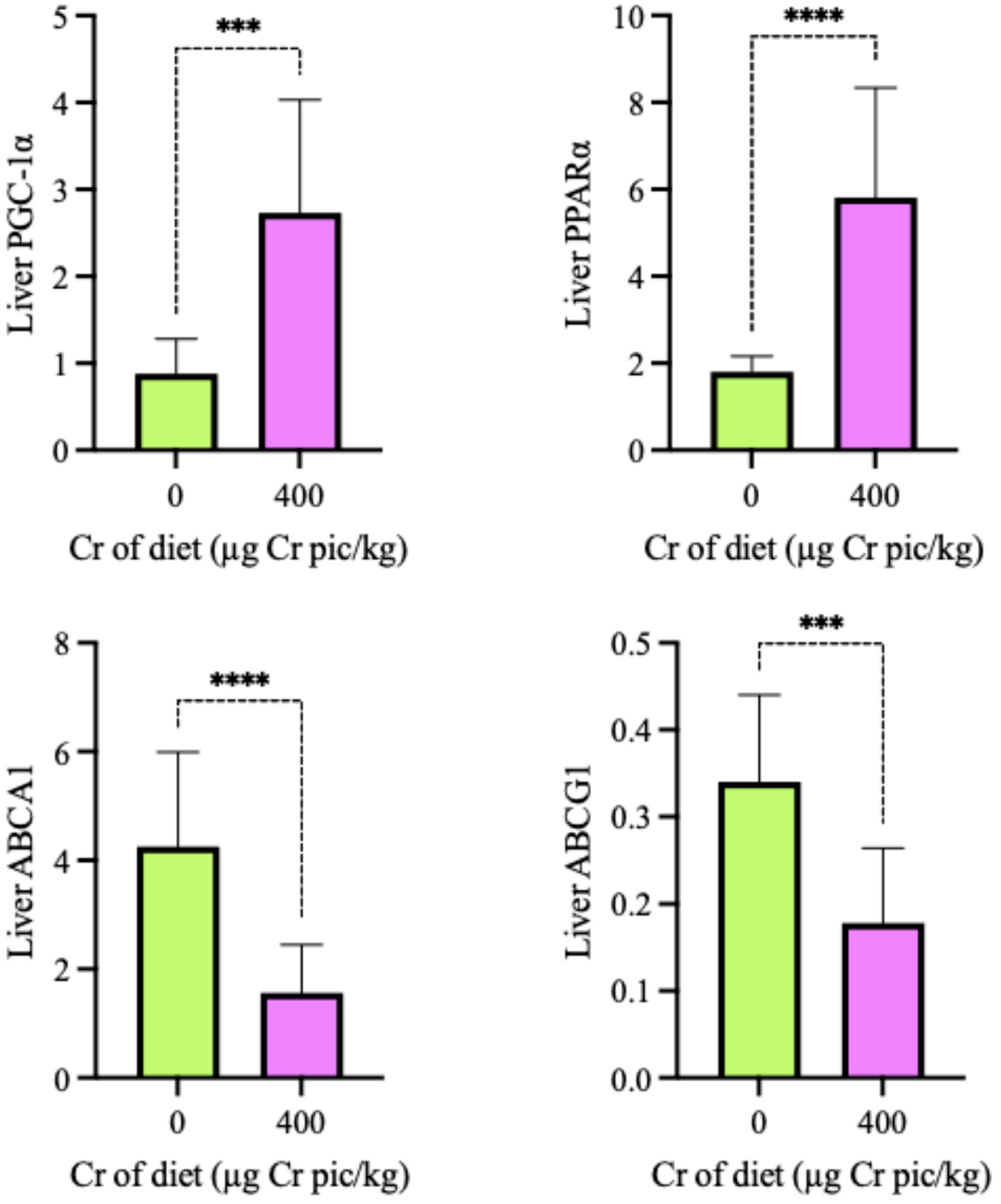

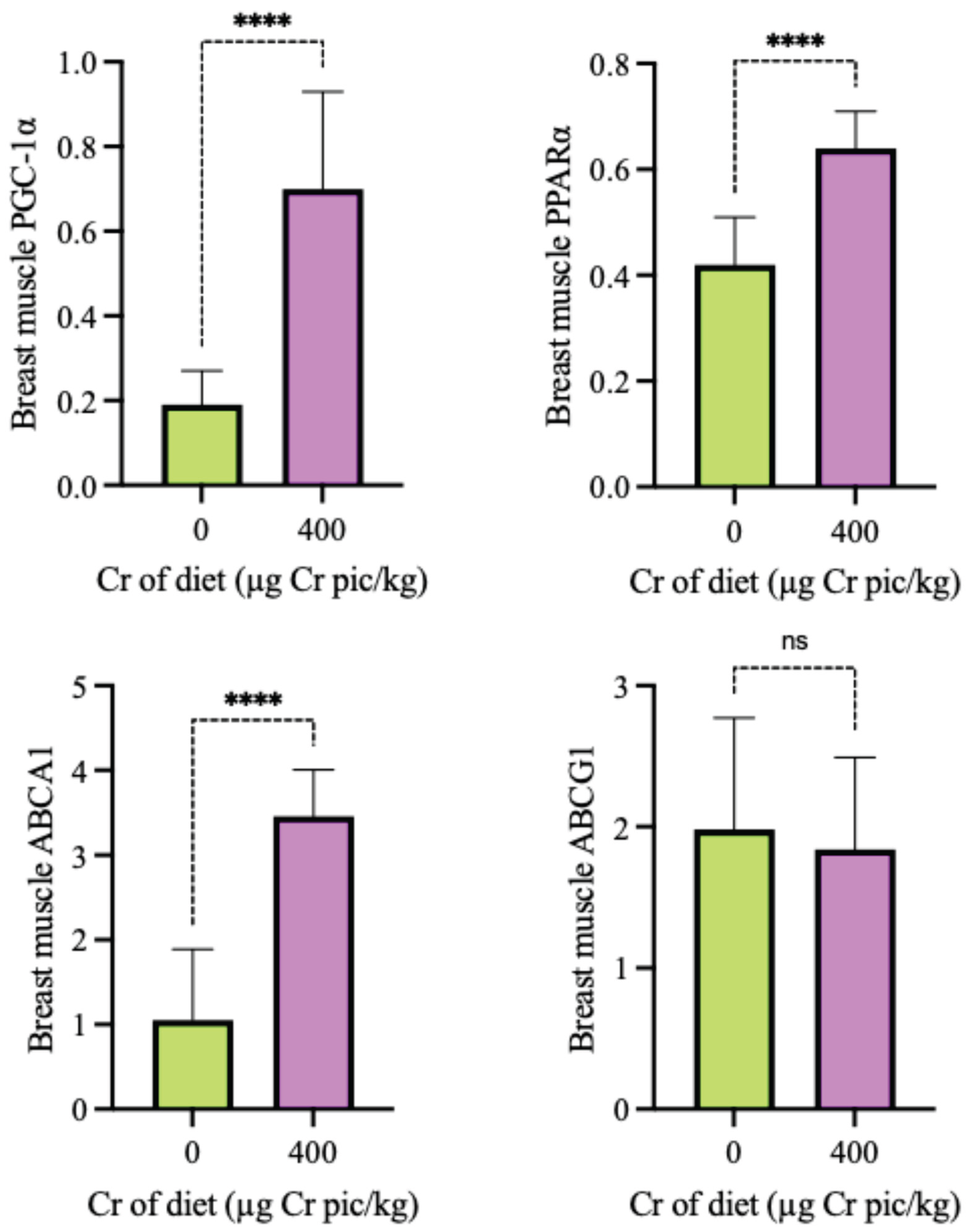

3.4. Genes Associated with Glycolipid Homeostasis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, L.-P.; Liu, Y.-L.; Zhang, J.-X.; Ding, K.-N.; Lu, M.-H.; He, Y.-M. Heat stress in broilers of liver injury effects of heat stress on oxidative stress and autophagy in liver of broilers. Poultry science 2022, 101, 102085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apalowo, O.O.; Ekunseitan, D.A.; Fasina, Y.O. Impact of Heat Stress on Broiler Chicken Production. Poultry 2024, 3, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Seong, P.; Seol, K.-H.; Park, J.-E.; Kim, H.; Park, W.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, S.D. Effects of heat stress on growth performance, physiological responses, and carcass traits in broilers. Journal of Thermal Biology 2025, 127, 103994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Mishra, P.; Al Amaz, S.; Mahato, P.L.; Das, R.; Jha, R.; Mishra, B. Dietary supplementation of microalgae mitigates the negative effects of heat stress in broilers. Poultry science 2023, 102, 102958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Ouyang, J.; Deng, C.; Zhou, H.; You, J.; Li, G. Effects of dietary tryptophan supplementation on rectal temperature, humoral immunity, and cecal microflora composition of heat-stressed broilers. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 10, 1247260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Li, B.; Wu, M.; Deng, Y.; Li, J.; Xiong, Y.; He, S. Effect of dietary supplemental vitamin C and betaine on the growth performance, humoral immunity, immune organ index, and antioxidant status of broilers under heat stress. Tropical animal health and production 2023, 55, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Kambe, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Arulmozhiraja, S.; Ito, S.; Nakagawa, Y.; Tokiwa, H.; Nakano, S.; Shimano, H. Elucidation of molecular mechanism of a selective PPARα modulator, pemafibrate, through combinational approaches of X-ray crystallography, thermodynamic analysis, and first-principle calculations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xiao, G.; Trujillo, C.; Chang, V.; Blanco, L.; Joseph, S.B.; Bassilian, S.; Saad, M.F.; Tontonoz, P.; Lee, W.P. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) influences substrate utilization for hepatic glucose production. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 50237–50244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, M.; Ambrożewicz, E.; Gęgotek, A.; Toczek, M.; Skrzydlewska, E. Long-term administration of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor (URB597) to rats with spontaneous hypertension disturbs liver redox balance and phospholipid metabolism. Advances in Medical Sciences 2019, 64, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, K.; Ozbey, O.; Onderci, M.; Cikim, G.; Aysondu, M.H. Chromium supplementation can alleviate negative effects of heat stress on egg production, egg quality and some serum metabolites of laying Japanese quail. Journal of Nutrition 2002, 132, 1265–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Lin, H.; Jiang, K.; Jiao, H.; Song, Z. Corticosterone administration and high-energy feed results in enhanced fat accumulation and insulin resistance in broiler chickens. British poultry science 2008, 49, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, M.A.; Grimes, J.L.; Lloyd, K.E.; Krafka, K.; Lamptey, A.; Spears, J.W. Chromium propionate in broilers: effect on insulin sensitivity. Poultry Science 2016, 95, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghyani, M.; Toghyani, M.; Shivazad, M.; Gheisari, A.; Bahadoran, R. Chromium Supplementation Can Alleviate the Negative Effects of Heat Stress on Growth Performance, Carcass Traits, and Meat Lipid Oxidation of Broiler Chicks without Any Adverse Impacts on Blood Constituents. Biological Trace Element Research 2012, 146, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, K.; Sahin, N.; Kucuk, O. Effects of chromium, and ascorbic acid supplementation on growth, carcass traits, serum metabolites, and antioxidant status of broiler chickens reared at a high ambient temperature (32°C). Nutrition Research 2003, 23, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkari, R.; Mandal, A.; Bhanja, S.; Goel, A.; Mehera, M. Dietary supplementation of chromium picolinate on productive performance and cost economics of coloured broiler chicken during hot-humid summer. International Journal of Livestock Research 2018, 8, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; He, X.; Ma, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Gao, F. Increased fat synthesis and limited apolipoprotein B cause lipid accumulation in the liver of broiler chickens exposed to chronic heat stress. Poultry Science 2019, 98, 3695–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloche, K.; Dozier III, W.; Brandebourg, T.; Starkey, J. Skeletal muscle growth characteristics and myogenic stem cell activity in broiler chickens affected by wooden breast. Poultry Science 2018, 97, 4401–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Yu, M.; Zhang, M.; Feng, J. Effects of Heat Stress on Breast Muscle Metabolomics and Lipid Metabolism Related Genes in Growing Broilers. Animals 2024, 14, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, N.; Hayirli, A.; Orhan, C.; Tuzcu, M.; Akdemir, F.; Komorowski, J.R.; Sahin, K. Effects of the supplemental chromium form on performance and oxidative stress in broilers exposed to heat stress. Poultry Science 2017, 96, 4317–4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, S.; Habibian, M.; Moeini, M.M.; Abdolmohammadi, A.R. Effects of Different Levels of Organic and Inorganic Chromium on Growth Performance and Immunocompetence of Broilers under Heat Stress. Biological Trace Element Research 2012, 146, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanian, R.; Rasouli, E. Dietary chromium methionine supplementation could alleviate immunosuppressive effects of heat stress in broiler chicks. Journal of Animal Science 2015, 93, 3355–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, A.; Lopes, P.C.F.; Boiago, M.M.; Silva, A.M.S.; Montassier, H.J.; de Souza, P.A. Productive and immunological traits of broiler chickens fed diets supplemented with chromium, reared under different environmental conditions. Revista Brasileira De Zootecnia-Brazilian Journal of Animal Science 2012, 41, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Naz, S.; Dhama, K. Chromium: Pharmacological Applications in Heat-Stressed Poultry. International Journal of Pharmacology 2014, 10, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, K.; Sahin, N.; Onderci, M.; Gursu, F.; Cikim, G. Optimal dietary concentration of chromium for alleviating the effect of heat stress on growth, carcass qualities, and some serum metabolites of broiler chickens. Biological Trace Element Research 2002, 89, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, L.Y.; Zeng, J.W.; Chu, X.W.; Mao, L.M.; Luo, H.J. Efficacy of trivalent chromium on growth performance, carcass characteristics and tissue chromium in heat-stressed broiler chicks. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2009, 89, 1782–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatya, J.L.; Haldar, S.; Ghosh, T.K. Effects of chromium supplementation from inorganic and organic sources on nutrient utilization, mineral metabolism and meat quality in broiler chickens exposed to natural heat stress. Animal Science 2004, 79, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeini, M.M.; Bahrami, A.; Ghazi, S.; Targhibi, M.R. The Effect of Different Levels of Organic and Inorganic Chromium Supplementation on Production Performance, Carcass Traits and Some Blood Parameters of Broiler Chicken Under Heat Stress Condition. Biological Trace Element Research 2011, 144, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaupere, C.; Liboz, A.; Fève, B.; Blondeau, B.; Guillemain, G. Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertz, W.; Schwarz, K. Relation of glucose tolerance factor to impaired intravenous glucose tolerance of rats on stock diets. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content 1959, 196, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, W. Chromium occurrence and function in biological systems. Physiological reviews 1969, 49, 163–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.J.; Li, X.M.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, J.H.; Zhang, M.H. Effects of Dietary Chromium Picolinate on Gut Microbiota, Gastrointestinal Peptides, Glucose Homeostasis, and Performance of Heat-Stressed Broilers. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, N.; Akdemir, F.; Tuzcu, M.; Hayirli, A.; Smith, M.; Sahin, K. Effects of supplemental chromium sources and levels on performance, lipid peroxidation and proinflammatory markers in heat-stressed quails. Animal feed science and technology 2010, 159, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Barrio, A.S.; Mansilla, W.; Navarro-Villa, A.; Mica, J.; Smeets, J.; Den Hartog, L.; García-Ruiz, A. Effect of mineral and vitamin C mix on growth performance and blood corticosterone concentrations in heat-stressed broilers. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 2020, 29, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Takahashi, T.; Sumitani, K.; Takatsu, H.; Urano, S. Glucocorticoid generates ROS to induce oxidative injury in the hippocampus, leading to impairment of cognitive function of rats. Journal of clinical biochemistry and nutrition 2010, 47, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, O.E.; Kalhan, S.C.; Hanson, R.W. The key role of anaplerosis and cataplerosis for citric acid cycle function. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 30409–30412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broeks, M.H.; Meijer, N.W.; Westland, D.; Bosma, M.; Gerrits, J.; German, H.M.; Ciapaite, J.; van Karnebeek, C.D.; Wanders, R.J.; Zwartkruis, F.J. The malate-aspartate shuttle is important for de novo serine biosynthesis. Cell Reports 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Si, X.; Ji, Y.; Yang, Q.; Bai, J.; He, Y.; Jia, H.; Song, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, L. l-Proline improves the cytoplasmic maturation of mouse oocyte by regulating glutathione-related redox homeostasis. Theriogenology 2023, 195, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzouk, M.M.; Hegazi, N.M.; El Shabrawy, M.O.; Farid, M.M.; Kawashty, S.A.; Hussein, S.R.; Saleh, N.A. Discriminative Metabolomics Analysis and Cytotoxic Evaluation of Flowers, Leaves, and Roots Extracts of Matthiola longipetala subsp. livida. Metabolites 2023, 13, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.-C.; Liu, J.-M.; Lee, K.-I.; Tang, F.-C.; Fang, K.-M.; Yang, C.-Y.; Su, C.-C.; Chen, H.-H.; Hsu, R.-J.; Chen, Y.-W. Cr (VI) induces ROS-mediated mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in neuronal cells via the activation of Akt/ERK/AMPK signaling pathway. Toxicology in Vitro 2020, 65, 104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, A.; Wroblewski, J.M.; Cai, L.; de Beer, M.C.; Webb, N.R.; van der Westhuyzen, D.R. Nascent HDL formation in hepatocytes and role of ABCA1, ABCG1, and SR-BI. Journal of lipid research 2012, 53, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenson, R.S.; Brewer Jr, H.B.; Davidson, W.S.; Fayad, Z.A.; Fuster, V.; Goldstein, J.; Hellerstein, M.; Jiang, X.-C.; Phillips, M.C.; Rader, D.J. Cholesterol efflux and atheroprotection: advancing the concept of reverse cholesterol transport. Circulation 2012, 125, 1905–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Content |

|---|---|

| Ingredients | |

| Corn | 56.51 |

| Soybean meal | 35.52 |

| Limestone | 1.00 |

| Soybean oil | 4.50 |

| NaCl | 0.30 |

| dL-Met | 0.11 |

| CaHPO4 | 1.78 |

| Premix1 | 0.28 |

| Total | 100.00 |

| Nutrient levels | |

| ME/(MJ/Kg) | 12.73 |

| CP | 20.07 |

| AP | 0.40 |

| Ca | 0.90 |

| Met | 0.42 |

| Lys | 1.00 |

| Met+Cys | 0.78 |

| Primer name1 | Primer sequence 5’-3’2 | Product size (bp) | GenBank accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | F: CTGTGTTCCCATCTATCGT | 270 | NM_205518.2 |

| R: TCTTCTCTCTGTTGGCTTTG | |||

| ABCA1 | F: TCATCCACCGCCGCCACATT | 223 | NM204145 |

| R: GGCTGAGGAAGGCACTGAAGTC | |||

| ABCG1 | F: AACCAGTGGCTTGGATAGTGC | 298 | XM_025145525.1 |

| R: CCTTACCAGTCGGCTGTTCTG | |||

| PPARα | F: CAAACCAACCATCCTGACGAT | 22 | NM_001001464.1 |

| R: GGAGGTCAGCCATTTTTTGGA | |||

| PGC-1α | F: TGCAGCGCGATCTGAATG | 110 | NM_001006457.1 |

| R: GTTCTTGTCCTTGAGCCACTGAT | |||

| R: CAAGACTGACTGTGAAGGCATCCA |

| Items2 | 0 | 400 | 800 | P-value |

| ADFI/g | 97.21b ± 4.22 | 105.02a ± 2.61 | 108.55a ± 5.56 | 0.02 |

| ADG/g | 56.37b ± 3.15 | 64.37a ± 1.58 | 68.51a ± 4.11 | <0.01 |

| FCRg/g | 1.73a ± 0.04 | 1.63b ± 0.04 | 1.59b ± 0.06 | <0.01 |

| Breast muscle rate (%) | 17.85b ± 1.27 | 19.18a ± 1.18 | 18.90a ± 0.7 | 0.01 |

| abdominal fat rate (%) | 0.77a ± 0.20 | 0.59b ± 0.22 | 0.56b ± 0.10 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).