2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal and Experimental Design

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Institute of Animal Science, Guangdong Academy of Agriculture Science, Guangzhou, P. R. China, with the approval number GAASISA-2022-003.

A total of 750 1-d male 817 crossbred broilers (39.50 g ± 0.20 g) were randomly assigned to 5 treatment groups (

Table 1), each with 6 replicates of 25 broilers. Birds in the control group (CON) and LPS-challenged treatment (LPS) were fed a basal diet, and birds in the other 3 treatments received the basal diet with 150, 300, or 450 mg/kg added GA (GA150, GA300, GA450). On days 14, 17, and 20 of the trial, birds in the LPS, GA150, GA300, and GA450 treatments were injected intraperitoneally with 0.5 mL of LPS (0.5 mg/kg body weight), while birds in CON received an equal amount of normal saline.

GA (99.6% purity) was obtained from Wufeng Chicheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Yichang, Hubei, China). LPS from Escherichia coli serotype O55:B5 was purchased (L4005, Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. Ltd, St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Diets and Chicken Husbandry

The basic diet (

Table 2) is formulated based on the nutritional requirements of fast-growing yellow-feathered broilers in China's "National Agricultural Industry Standard Nutrient Requirements for Yellow-feathered Broilers" (NY/T3645-2020) [

11].

The 50-day experiment was carried out in the testing farm of the Institute of Animal Science, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Broilers were raised in floor pens and had ad libitum access to diets and water. Room temperature was maintained at 27 to 30 °C. For the first 3 d, the light was kept constant for 23 h per d, and then reduced by 2 h per d and maintained at 16 h per d.

2.3. Measurements of Growth Performance

The BW of the birds was measured at 1 and 50 d of age on a pen basis and feed intake was recorded daily. Mortality was checked daily, and dead birds were recorded and weighed to adjust estimates of gain, intake, and feed conversion ratio, as appropriate. The final body weight (FW), average daily feed intake (ADFI), average daily gain (ADG), and Feed-to-gain ratio (F: G) were calculated.

2.4. Sample Collection

On the 50th day of the experiment, two experimental chickens with a weight close to the average were selected from each treatment group for slaughter. The left breast muscle was taken to measure breast muscle color, pH value, cooking loss, drip loss, shear force, crude fat and other indicators. The right breast muscle specimen was taken and stored in a -80 °C ultra-low temperature refrigerator to detect the antioxidant index, shelf life index and related gene expression.

2.5. Determination of Meat Quality

The brightness (L*), redness (a*), and yellowness (b*) value of slaughtered pectoral muscles were measured by a colorimeter (CR-410, Minolta, Japan) after 45 min and 24 h at room temperature. Each sample was measured three times and the average value was taken. The pH of the slaughtered pectoral muscles was determined using a muscle pH meter (HI8242, HANNA, Italy) after 45 min and 24 h of standing at room temperature, with each sample measured three times and the average value taken. The drip loss was measured according to the procedure reported by Jin et al. [

12]. Briefly, breast muscle chunks (size 2 × 3 × 4 cm) were weighed, and suspended in a cup at 4 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, the weight was recorded to calculate drip loss.

2.6. Determination of Intramuscular Fat and Total Volatile Base Nitrogen Contents

Approximately 20 g of pectoral muscle samples were weighed, the fascia was removed, minced, placed in a Petri dish, and freeze-dried at -80 °C for 48 h. Accurately take 2 g of freeze-dried sample seal it in a filter bag and extract it through a Soxhlet extraction device (XT15i, USA). After extraction, the filter paper tube was removed and the fat bottle was placed back into a constant temperature oven at 105 °C for 3.5 h, then removed, cooled and weighed to calculate the intramuscular fat (IMF) content. The total volatile base nitrogen (TVB-N) values were measured according to the method proposed by Chen et al. [

13], with results expressed in milligrams of TVB-N per 100 g of sample.

2.7. Determination of Pectoral Muscle Fatty Acid Composition

Weigh about 1 g of pectoral muscle tissue sample and homogenize. Add 2 mL of n-hexane and shake at 50 °C for 30 min, add 3 mL of KOH methanol solution (0.4 mol/L) and shake at 50 °C for 30 min, then add 1 mL of water and 2 mL of n-hexane and mix well. The upper layer was separated, and the composition and proportion of fatty acids were determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) using an Agilent 7890B-5977A gas chromatography-mass spectrometer (GC-MS).

2.8. Determination of Pectoral Muscle Antioxidant Index

Weighing approximately 1 g of broiler breast muscle samples, the tissue was then cut into pieces and homogenized to a concentration of 10% in normal saline at a ratio of 1:9 (sample: normal saline). Moreover, the commercially available reagent kits of the malonic dialdehyde (MDA, A003-1-2) content, total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD, A001-1-2), catalase (CAT, A007-1-1), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px, A005-1-2) and total anti-oxidative capacity(T-AOC, A015-1-2)were used to determine the concentration of MDA and the activities of antioxidant enzyme in muscle following the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng Biotech Limited., Nanjing, China).

2.9. Expression of Related Genes in Pectoral Muscle

Total RNA was extracted from jejunal mucosa using RNAiso plus (9109, TAKARA, Tokyo, JP) and reverse transcribed with the PrimeScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (6210A, TAKARA). Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR PremixExTaq II (RR820A, TAKARA) and the real-time PCR system (ABI 7500, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). The primers used are shown in

Table 3. Results were normalized to the abundance of

β-actin transcripts and relative quantification was calculated using the 2

–△△CT method.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

A pen or individual bird was taken as the experimental unit. The effects of treatment were examined by multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) using SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The treatment means were compared by Duncan’s multiple range tests at P < 0.05 significance levels. Tabulated results were shown as means with standard error of mean (SEM).

4. Discussion

Growth performance is one of the most important indicators to evaluate whether an additive is effective or not. While LPS stimulation, as a stress model, can change the content of water and electrolytes in the small intestine, causing an imbalance of homeostasis in the intestinal tract of broiler chickens, which can reduce the growth performance of poultry [

14]. Zhang et al. injected LPS into the peritoneal cavity of AA chickens at the ages of 16, 18, and 20 days, which significantly reduced the body weight gain of broilers at the ages of 1 to 21 days [

15]. This is similar to the results of the present experiment, therefore, alleviating the decline in growth performance caused by LPS stimulation could also reflect the effect of the additive. Samuel et al. increased feed conversion ratios from 21 to 42 days of age and 1 to 42 days of age by adding 75 to 100 mg/kg of GA to 1-day-old AA broiler diets [

16]. This was similar to the results of the present experiment, where GA addition increased body weight and decreased FCR in starter stage, finshing stage, and whole stage compared to the LPS-stimulated group. Another study showed that the addition of grape pomace rich in GA by drinking water increased the body weight of broiler chickens by 5.8% and resulted in a cecal microbial composition that was more favorable for energy deposition in broiler chickens, thereby promoting weight gain in broiler chickens [

17]. In addition, GA has been shown to have antimicrobial properties, induce changes in the microbiota toward a more favorable composition and activity, promote gastrointestinal epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation, and repair damaged mucosa to improve nutrient digestion and absorption [

18,

19,

20]. Therefore, the positive effects on growth performance shown in this study can be explained by the fact that GA may counteract the impairment of LPS on the digestion and absorption capacity of broiler chickens by suppressing the inflammatory response and using the intestine as a target organ by maintaining its barrier function.

Muscle pH value is an important index to evaluate muscle quality and the decomposition rate of muscle glycogen after poultry slaughter, which is mainly affected by phosphofructokinase activity [

21]. The amount of lactic acid produced in muscle is related to the glycogen content in the muscle. The more glycogen reserves in muscle, the more lactic acid is produced during strenuous exercise, the more it accumulates, and the lower of the pH value, which leads to meat acidification. In addition, studies have shown that the pH value of breast muscle is negatively correlated with brightness, yellowness, and shear force [

22], and differences in muscle fiber composition, density, and diameter can affect muscle pH [

23]. In the present study, the addition of 150 mg/kg GA obviously reduced the pH value of breast muscle 45 min after slaughter. It has been reported that GA added to the diet can be distributed to tissues throughout the body [

24], which could be responsible for the decrease in the pH value of muscle tissue. The meat color is one of the main quality attributes that directly influence consumer choice. Fresh chicken breasts are slightly pink, but may also appear white to yellow due to several factors [

25]. It has been reported that the color of meat may be influenced by the concentration of myoglobin, its chemical and physical state, and the structure of the meat surface [

25,

26]. Drip loss is a major indicator of muscle water-holding capacity. Muscle with weak water-holding capacity have accelerated loss of total pigments and soluble nutrients, resulting in impaired meat color and flavor [

27]. Muscle brightness was correlated with drip loss, with higher brightness being associated with poorer water-holding capacity and relatively higher drip loss. The results of the present study showed that the addition of 450 mg/kg GA had higher pectoral muscle brightness value compared to the LPS and CON groups. Increased brightness value and drip loss often imply accelerated muscle protein degradation [

28], and lower pH reduces the hydrolytic potential of proteins, which reduces the muscle's water-locking capacity, and free water in the muscle seeps out of the surface of the muscle, which leads to an increase in brightness [

29].

Oxidative reactions are still going on in the muscle after the animal is slaughtered. The activities of auto-antioxidant enzymes decreases continuously with the prolongation of post-slaughter muscle placement time, and if it decreases to a level that does not effectively reduce ROS, it can lead to muscle quality degradation and the production of toxic and hazardous substances, such as volatile saline nitrogen, thus affecting the shelf life of the product, which is not conducive to the health of the consumer ([

30]Onk et al., 2019). Volatile saline nitrogen content, as an indicater of the proteolysis level, increased with storage time, thus accelerating muscle spoilage [

31]. The addition of 450 mg/kg GA significantly reduced the volatile saline nitrogen content of pectoral muscle. In addition to its antioxidant function, this may be due to the fact that GA inhibited the growth of

Pseudomonas spp. and

Enterobacter spp. in muscle, which can use amino acids as a growth substrate to produce sulfur-containing compounds and amines with an off-flavor, resulting in a rapid increase in the volatile base nitrogen content [

32,

33]. The test results suggest that the addition of GA is beneficial to improve the storage stability of muscle and prolong the shelf life.

Eating foods rich in n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA) and essential fatty acids can play a natural preventive role in cardiovascular disease and other health problems [

34,

35]. The nutritional quality of chicken is an important factor affecting the health of consumers. Studies have found that PUFA can be effectively deposited in chicken and improve the quality of chicken [

36]. The fatty acid composition of intramuscular fat, on the other hand, has implications for human health, and it is generally recognized that higher PUFA/SFA ratios are less likely to increase the incidence of cardiovascular disease and that PUFA/SFA > 0.45 barely increases the incidence of cardiovascular disease [

37]. However, lipid oxidation increases linearly with increasing PUFA content, and the oxidative stability of unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) decreases with increasing levels of unsaturation. omega-3 long-chain unsaturated fatty acids, especially docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6n-3), are very sensitive to oxidation, and the body's antioxidant capacity has a significant effect on their content [

38]. DHA can promote brain and retinal development, inhibit inflammation, and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and obesity [

39]. Studies have shown that adding basil, thyme, and sage to the diet can significantly increase the healthy ALA (C18:3n-3), EPA (C20:5n-3), DHA, and total PUFA content and improve the fatty acid profile in broiler muscles [

40]. In this experiment, the addition of GA not only improved the antioxidant properties of broiler thigh muscle but also enhanced its nutritional value by increasing health-promoting n-3 PUFA. Since there was no change in the unsaturated fatty acid content in the diets of each stage, the higher unsaturated fatty acid content in the thigh meat of broilers supplemented with natural feed additives may be due to the protective effect of antioxidants on the oxidative decomposition of unsaturated fatty acids. Therefore, GA may increase the relative content of DHA in breast muscle through antioxidant action, thus improving the nutritional quality of muscle.

Under physiological conditions, animals produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can cause damage to the body [

41]. Multiple studies have shown that polyphenols can improve tissue oxidative status by scavenging free radicals and increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes [

42,

43,

44]. Dietary addition of plant polysaccharides, polyphenols and other bioactive substances can improve the antioxidant capacity of muscle and improve muscle quality [

45,

46]. GA is a good natural antioxidant that can eliminate ROS such as superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals [

47,

48]. Ramay et al. have shown that antioxidant enzymes such as CAT, SOD and GSH-Px can work together to reduce MDA content, remove excess ROS, reduce oxidative damage of breast muscle, and thus maintain better muscle mass [

45]. In this experiment, the addition of GA to the diet could alleviate the effects of LPS-induced increase in muscle MDA content and decrease in T-SOD, GSH-PX and CAT activities. This is consistent with previous study that GA can improve the antioxidant capacity of broiler chicken muscle [

16,

49]. In summary, our results further confirmed that GA can effectively exert its antioxidant function to ensure animal health and growth.

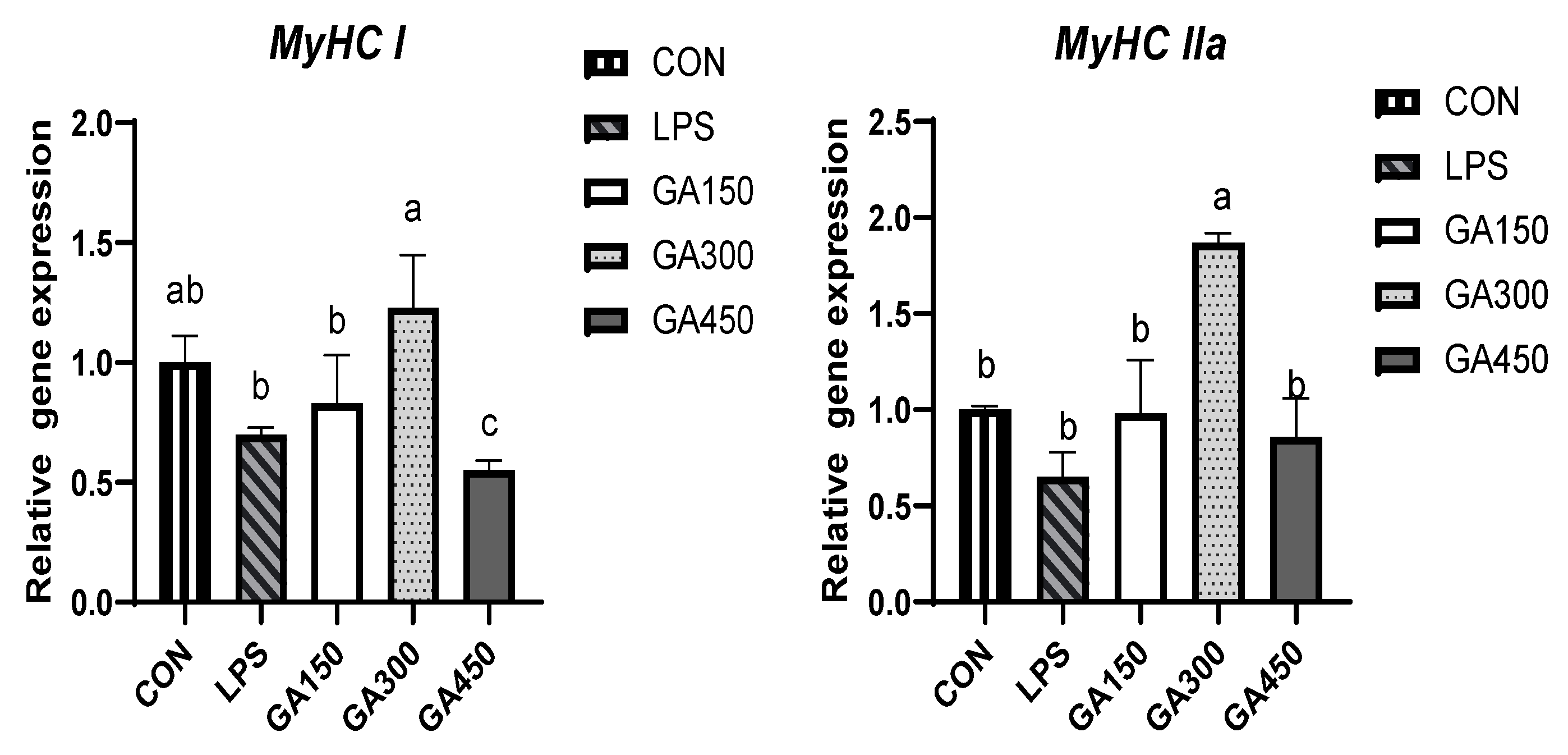

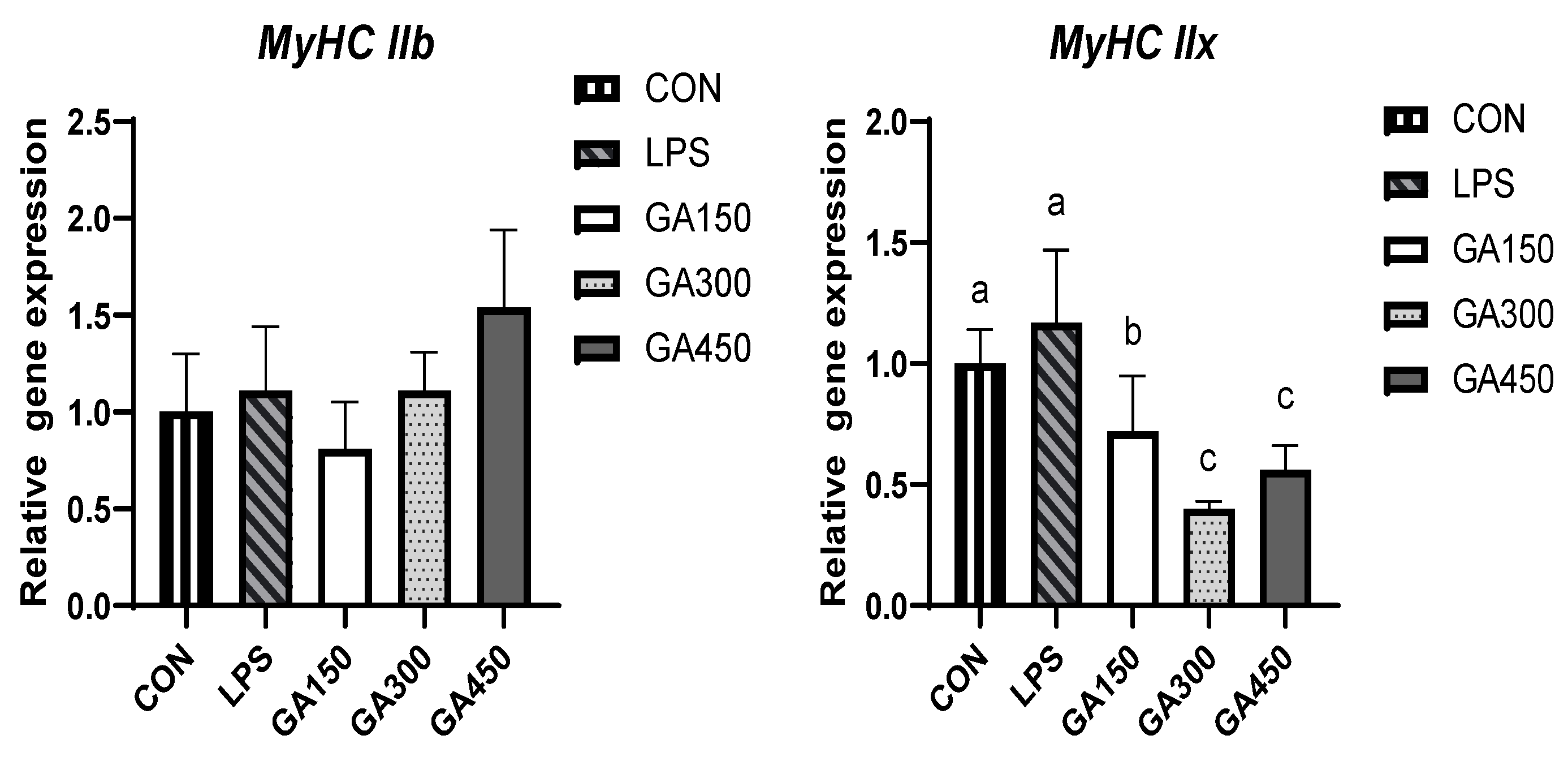

Shear force is an indicator of muscle tenderness, which is inversely related to tenderness, and is related to myofiber diameter and fascicle membrane thickness. The myosin heavy chain method of classifying muscle fiber types is based on their ATPase activity and maximum contraction velocity, which classifies myosin heavy chains into four different major isoforms: slow oxidizing (I), fast oxidizing (IIa), fast fermenting (IIb), and intermediate (IIx) [

50]. Aerobic endurance exercise in humans and animals effectively induces skeletal muscle type remodeling, i.e., the gradual transformation of skeletal muscle fibers from fast muscle (high proportion of

MyHC type IIb fibers) to slow muscle (high proportion of

MyHC type I fibers) [

51]. This adaptive remodeling process of muscle fiber type is crucial for the body's energy homeostasis, fatigue alleviation, and improvement of livestock and poultry meat quality [

52]. Type I fibers contain more mitochondria and aerobic metabolic enzymes such as cytochrome oxidase and succinate dehydrogenase, while type IIb fibers contain less mitochondria and more glycogen and glycolytic enzymes, and type IIa fibers are involved in glycolysis and aerobic oxidation. The heme content of type IIb fibers was lower than other types of fibers, the proportion of oxidized myosin heavy chain in muscle is negatively correlated with myofibril diameter, and the proportion of intermediate type is positively correlated with the proportion of myofibrils [

53]. This experiment found that the addition of GA increased the gene expression of oxidized myosin heavy chain in the breast muscle of broiler chickens, reduced the gene expression of intermediate myosin heavy chain, promoted the differentiation of muscle fiber heavy chain type to the oxidized muscle fiber, reduced the diameter of breast muscle fibers and increased the density. This suggests that GA may reduce muscle shear force, increase muscle tenderness and improve meat quality by regulating the muscle fiber structure type. It is similar to the findings on polyphenol in fattening pigs [

54].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.X., Z.L., D.R.; Data curation, T.X., M.H., J.W., and S.T.; Formal analysis, T.X., Z.L., and D.R.; Investigation and Project administration, C.Z., J.Y., D.X., and Q.F.; Resources, F.D. and Z.C.; Supervision, S.J.; Writing—original draft, T.X., M.H., J.W.; Writing—review editing, Z.C., D.R., and S.J.; Funding acquisition, S.J.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.