1. Introduction

The increasingly serious abuse of antibiotics resulting from the search for economic benefits [

1] has led to significant environmental pollution. In response to growing concerns regarding food safety and the issuance of the "Anti-Resistance Prohibition Order" [

2], the development and utilization of antibiotic alternatives have become crucial for sustainable development in the field of livestock husbandry [

3]. Pig manure, as one of the main sources of air pollutants, not only has adverse effects on animal health and growth performance, but also poses a threat to human health [

4]. While the pig industry has integrated advances in large-scale practices, the discharge of large quantities of manure into the environment poses substantial challenges to human living conditions, considering delayed modernization and the adoption of imperfect technologies, especially in the stage of finishing pigs, the utilization rate of feed nutrients decreases, the emissions increase, and thus cause serious fecal pollution. Furthermore, the reduction of carbon emissions, thereby reducing pollution, has become a key focus for many countries.

Based on this, plant polysaccharides, which present a wide range of pharmacological effects and high biological activity, are often used as an alternative in livestock production. Research has shown that, plant polysaccharides in animal husbandry can improve production performance, intestinal function, and immune response [

5,

6]. According to the report, it has been shown that the addition of

Astragalus polysaccharides to the diet can improve the growth performance of weaned piglets and increase their intestinal villus height which, in turn, increased intestinal barrier function, and it had an immunomodulatory effect, thus enhancing the immune response; in particular, it was shown to have an immunomodulatory effect on porcine peripheral blood mononuclear cells exposed to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and swine fever virus [

7,

8]. There are also reports pointing out that the addition of

Echinacea at an appropriate level can enhance macrophage bactericidal ability, thereby regulating host defence against pathogen invasion and enhancing immune function in mice [

9]. What is more valuable is the use of plant polysaccharides can improve the digestibility of nutrients in finishing pigs, thereby effectively controlling fecal excretion and reducing emissions of CO2 and other harmful gases [

10,

11,

12], thereby reducing the emission of toxic and harmful substances, leading to reduced environmental pollution. However, there is currently limited research on whether plant polysaccharides can improve the impact of heavy metal emissions in animal manure.

Boric acid, as an acidifier, can be widely present in nature, improving gastrointestinal pH and intestinal tissue structure, improving intestinal microbiota and pepsin activity, thereby promoting nutrient digestibility [

13], and it can improve growth performance and enhances immunity and antioxidant function, while reducing the release of toxic and harmful substances from the body [

14]. Furthermore, the results of previous experiments conducted by our have revealed that the addition of appropriate amounts of boron could mediate the apoptosis and immune function response of splenic lymphocytes in rats, implying that boron could be added in appropriate amounts as an immunomodulatory agent in human and animal foods. In response to these results [

15,

16,

17,

18], we conducted a related study in pigs to explore the effects of the combined application of the plant polysaccharides and boron.

As reported above, we have found that there are currently no reports on the effects of the combination of plant polysaccharides and boron on the health and fecal emissions of finishing pigs. Therefore, we tested these two additives, to determine whether any further improvement in the application effect can be obtained, and whether it can reduce the emission of harmful substances from animals, thus achieving a better overall effect. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the effects of different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid on the production performance of finishing pigs, as well as digestive enzyme activity, immune and antioxidant functions, and the emission of harmful gases and heavy metals in faeces and urine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and rearing conditions

The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved (Approval number: 2023029) by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Anhui Science and Technology University.

A total of 90 healthy 90-day-old three-way cross-bred finishing pigs (Duroc × Landrace × Large White) with an initial average body weight (BW) of 41.25 ± 3.07 kg were included in the experiment and collective rearing at Wu Zifeng finishing Farm, Anhui Hefeng Agriculture and Animal Husbandry Co., Ltd., China. Animals were managed and immunized daily according to the Hefeng livestock finishing pig management manual. The pigs were assigned into five pens in a completely randomized manner, where each pen was equipped with one funnel-shaped feed trough and two waterers for free feeding and drinking. Regular cleaning, ventilation, and exhaust were maintained in the pens to ensure cleanliness and good air quality. Daily observations and records were made regarding the feeding behaviour and mental status of the pigs.

2.2. Experimental design

Crossbred pigs were randomly assigned to five experimental groups, each replicate with 6 pigs and 3 replicates per group, and were fed by adding to the base ration as follows: Con) A control, in which animals received a basic feed; BA ) experimental group I, basic feed supplemented with 40 mg/kg of boric acid [

19,

20]; BA+APS) experimental group II , basic feed supplemented with 40 mg/kg of boric acid and 400 mg/kg of

Astragalus polysaccharides [

18,

21]; BA+GLP) experimental group III, basic feed supplemented with 40 mg/kg of boric acid and 200 mg/kg of

Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides [

22,

23]; and BA+EPS) experimental group IV, basic feed supplemented with 40 mg/kg of boric acid and 500 mg/kg of

Echinacea polysaccharides [

24]. The amount of boric acid and polysaccharides added was determined according to the literature and pre-experimentation in this subject group. The designed amounts were below the maximum amount of addition effectively utilized in the animals, and the optimum level was calculated. The experiment lasted a total of 90 days. The nutrient composition and levels in the basic feed provided to the animals are detailed in

Table 1.

2.3. Sample collection and processing

Animals were weighed and labelled prior to the start of the experiment, and the initial and final weight measurements were recorded. The amount of feed given and the amount of leftover feed were recorded daily. Three days before the end of the experiment, fresh faeces and urine were randomly collected from 2 pigs in each replicate every morning, which were mixed separately. Then, 50 g of each of urine and faeces were mixed according to a 1:1 ratio of faeces:urine in a plastic bottle, which had a small hole in the middle of the upper part of the bottle, and was sealed and preserved. Fermentation was carried out at natural room temperature (20 °C) for 24 h. NH

3 and H

2S emissions from the faeces were measured on 3 consecutive days using a combined multi-gas detector (Model: K-400A): Kailu Electronic Technology Co., Ltd. (Henan). A portable gas sampling pump was used to extract the gas from a small hole above the sample bottle by inserting it 2 cm above the faeces in the bottle, and the values of NH

3 and H

2S gases were recorded at the same time using a combined multi-gas detector [

25]. At the end of the experiment, the animals were fasted for 12 h and blood samples were taken from the ear vein, which were stored at 4 ℃. The samples were centrifuged at 3000 r/min to obtain serum samples, which were stored at −80 ℃. Anesthetizing the animal to make sample collection painless, tissue samples from the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, spleen, and lymph nodes were collected [

26]. Randomly sampling 6 pigs per group, for a total of 30 pigs sampled, and the samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 ℃ in an ultrafreezer.

2.4. Determination of production indices

2.4.1. Growth performance index

At the beginning and end of the experiment, animals were weighed on an empty stomach. The amount of feed given, the amount of leftover feed, and the amount of feed consumed were accurately recorded daily, in order to determine the average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI), and gain-to-feed ratio (G/F) of pigs during each developmental stage.

2.4.2. Determination of intestinal digestive enzyme activity

Duodenum, jejunum, and ileum tissues were placed in cryotubes and stored at −80 ℃ in an ultrafreezer. Frozen chyme was ground into tissue homogenate using a tissue homogenizer (20 μL, 100 μL, 200 μL, and 1,000 μL) with an adjustable single-channel pipette (Eppendorf AG, Germany). After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and the trypsin, maltase, and lipase activities were measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China).

2.4.3. Determination of antibody levels and cytokine markers

After thawing at room temperature, tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin-2 (IL-2), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) in serum samples and spleen and lymph node tissues were measured. The measurement was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions of kit (Beijing Dacome Technology Co, China).

2.4.4. Determination of antioxidant function

The levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (T-SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) in serum samples and spleen and lymph node tissue homogenates were measured using appropriate ELISA commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China), based on the manufacturer’s instructions, to determine the antioxidant status of pigs.

2.4.5. Determination of harmful gases and metallic elements in faeces

Freshly sealed faeces and urine were fermented at room temperature (20 ℃) for 24 h. Gas emissions of NH3, NH3-N, and H2S from faecal samples were continuously measured for three days in a composite multi-gas detector (K-400A; Henan Kailu Electronic Co., Ltd. China). A portable gas sampling pump (ZC500; suction flow rate at 500 mL/min; Henan Kailu Electronic) was used to extract gas from 2 cm above the faeces in the sample bottle through a small hole above the bottle. The gas values were recorded simultaneously using a composite multi-gas detector.

The detection of metal ions and ammonia nitrogen emissions in faeces was performed by Qingdao Science and Technology Innovation Quality Testing Co., Ltd. in Qingdao High-tech Zone, Shandong Province, China.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Before analysis, all of the data were tested for normality using histograms and the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data were compared among groups using two-factor analysis of variance test after normal test processing and conversion, if necessary. Data that did not follow a normal distribution were processed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. differences were considered at p < 0.05. The initial body weight was included as a covariate in the growth performance analysis. The statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Correlations were assessed using Pearson correlation analysis of the Euclidean distance. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. GraphPad Prism (version 9.0 Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid on growth performance of finishing pigs

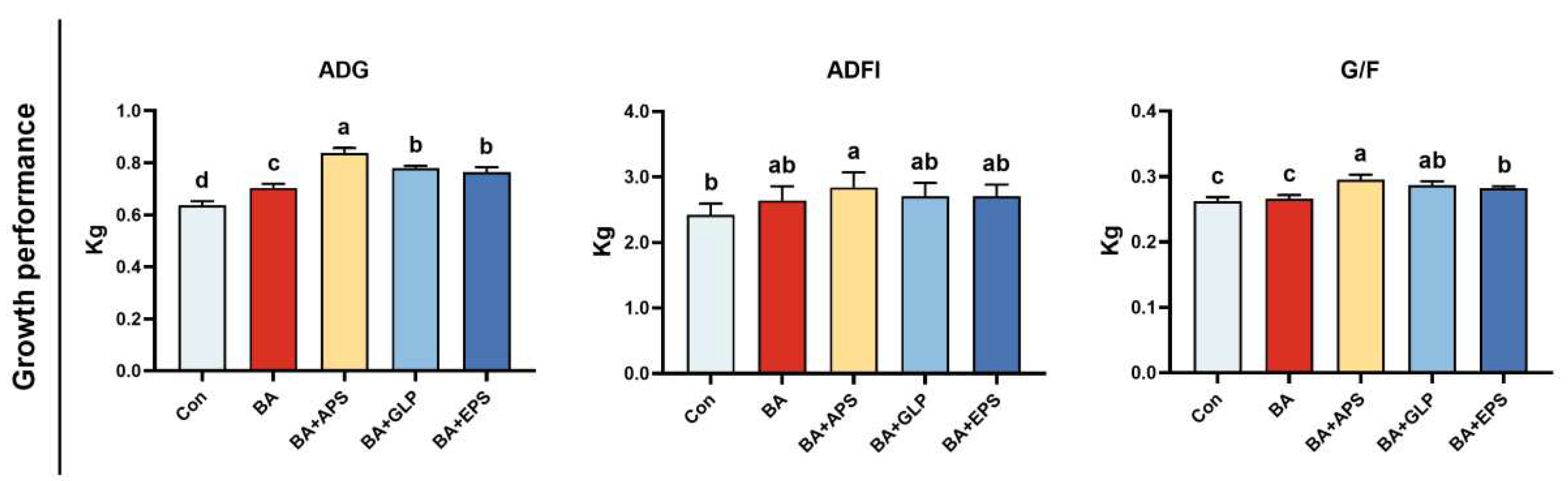

Compared to the Con (

Figure 1), BA exhibited a increase in ADG by 9.53% (

p < 0.05), while no differences were observed for ADFI and G/F. BA+APS exhibited increases in ADG, ADFI and G/F (

p < 0.05). BA+GLP and BA+EPS exhibited increases in ADG by 22.48% and 11.71%, respectively (

P < 0.05), while G/F also shows an upward trend compared to the Con (

p < 0.05). Compared with BA, increase in ADG and G/F were observed in BA+APS, BA+GLP and BA+EPS (

p < 0.05).

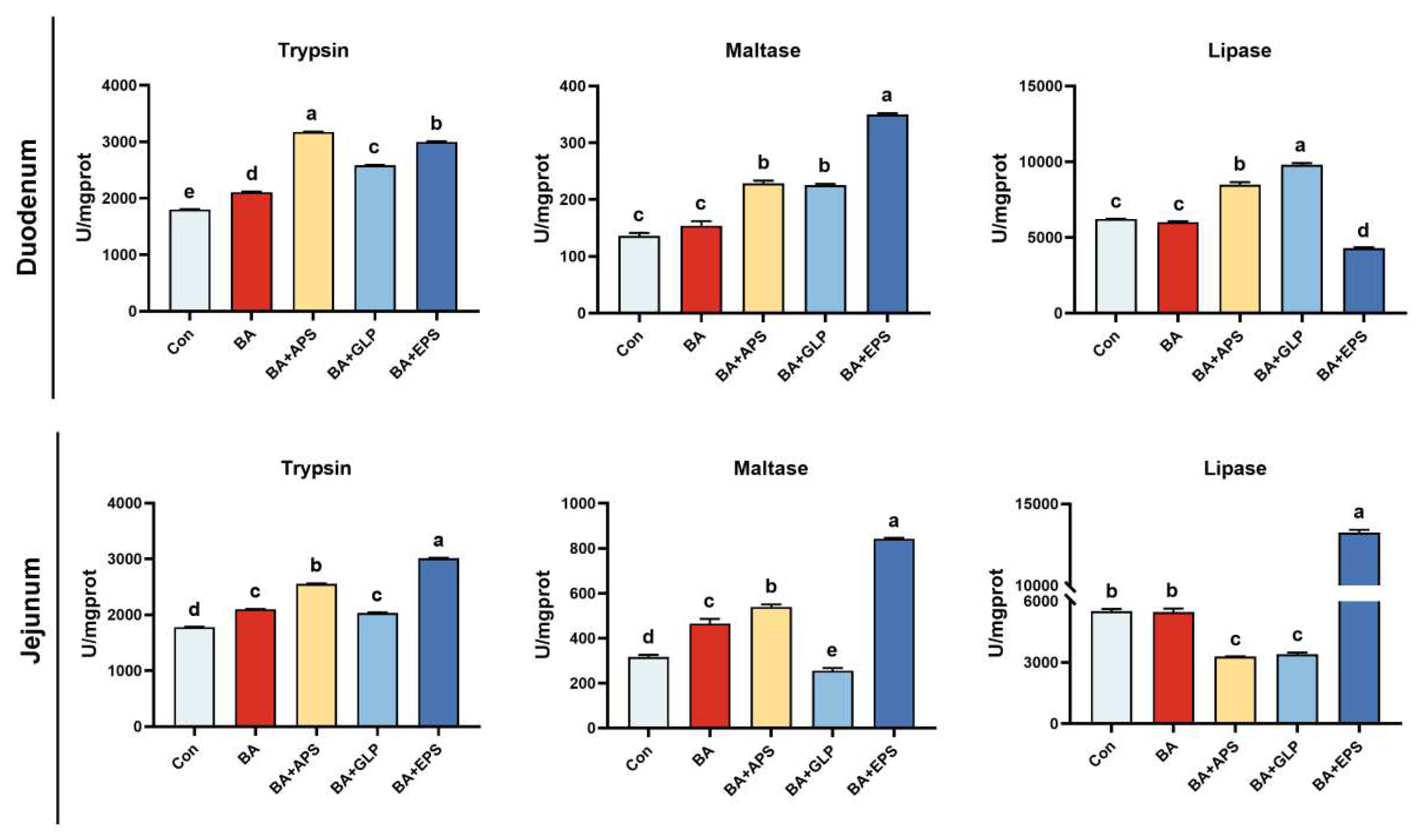

3.2. Effects of plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid on digestive enzyme activities of finishing pigs

Compared with the Con (

Figure 2), trypsin activity in the duodenum and jejunum of animals in other groups was increased (p < 0.05). In addition, maltase activity in the duodenum of animals in BA+APS, BA+GLP and BA+EPS and in the jejunum of animals in BA, BA+APS, and BA+EPS increased by 68.16%, 65.68%, 157.54%, 47.19%, 70.05%, and 166.36%, respectively (p < 0.05). Compared with the Con, lipase activity in the duodenum of animals in BA+APS and BA+GLP, as well as in the jejunum of animals in BA+EPS, was increased (p < 0.05). Duodenal and jejunal trypsin activities of pigs in the Con and BA presented differences (p < 0.05). Compared with BA, trypsin activity was increased in the duodenum of animals in BA+APS, BA+GLP and BA+EPS and in the jejunum of animals in BA+APS and BA+EPS (p < 0.05). In contrast, trypsin activity in the jejunum in animals in BA+GLP was decreased by 47.85% (p < 0.05). Moreover, maltase activity was increased in the duodenum of animals in groups BA+APS, BA+GLP and BA+EPS and in the jejunum of animals in BA+APS and BA+EPS (p < 0.05). Finally, lipase activity was increased (p < 0.05) in the duodenum of animals in BA+APS and BA+GLP, as well as in the jejunum of animals in BA+EPS.

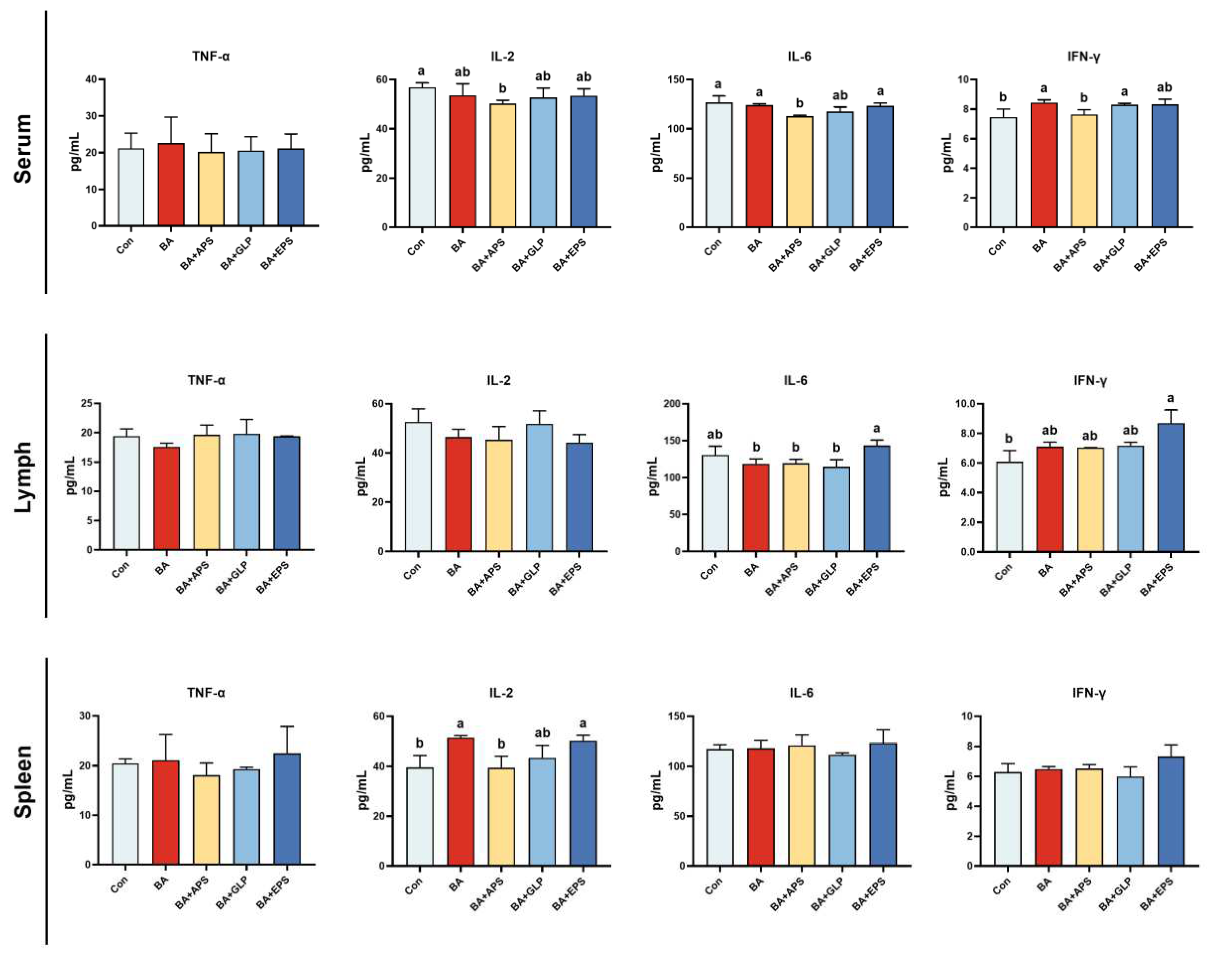

3.3. Effects of plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid on immune function of finishing pigs

Compared with the Con (

Figure 4), IFN-γ levels in the lymph nodes of animals in BA+EPS and IL-2 levels in the spleen of BA and BA+EPS were increased (p < 0.05), and IFN-γ levels in the serum of animals in BA, BA+GLP and BA+EPS were increased (p < 0.05) No difference was found in TNF-α level between serum and lymph nodes, or between serum and spleen. Moreover, compared with BA, IL-6 levels in the lymph nodes of animals in BA+EPS were increased (by 20.65%; p < 0.05). No difference was observed between the other groups.

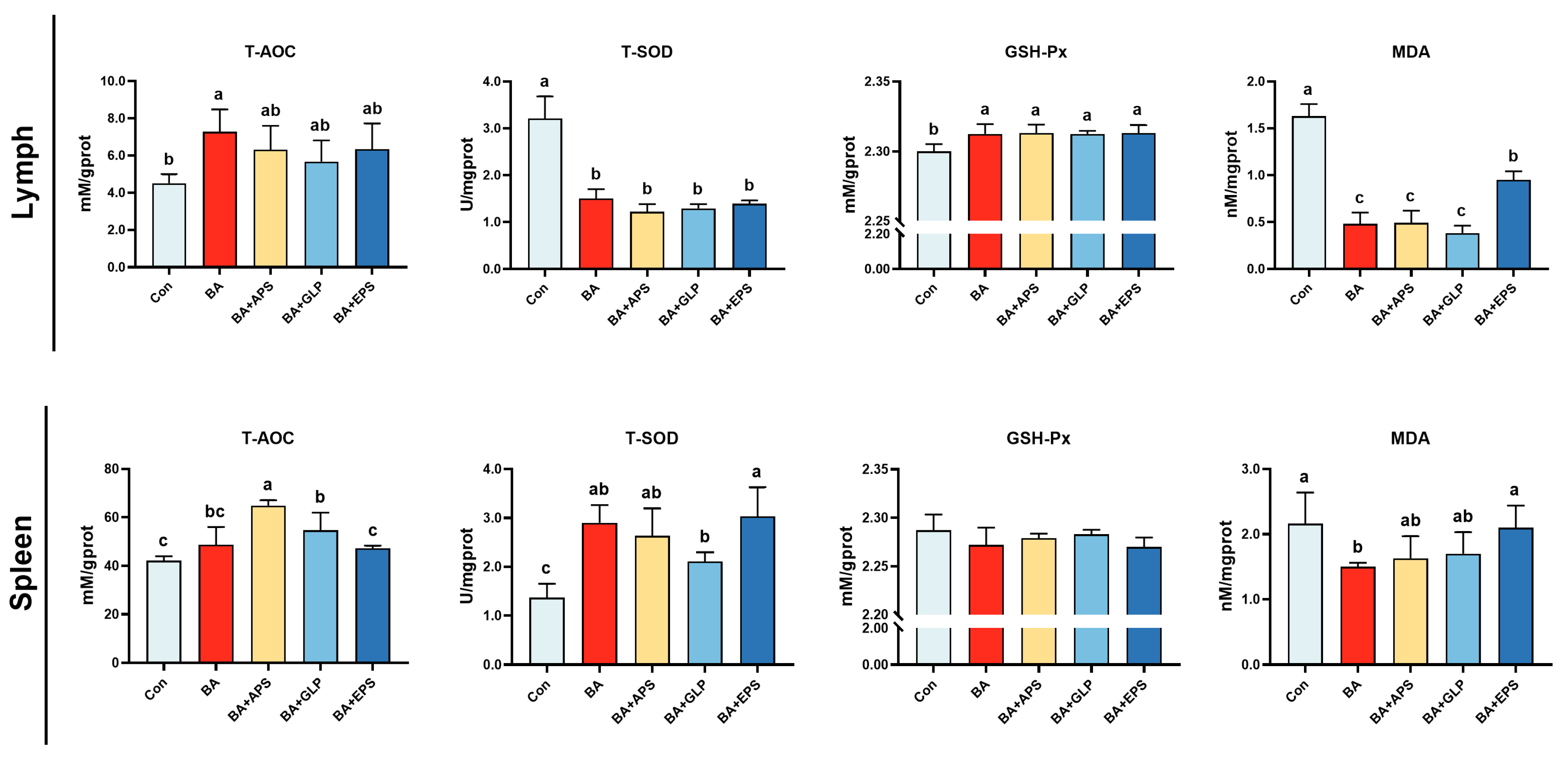

3.4. Effects of plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid on antioxidant activity of finishing pigs

Compared with the Con (

Figure 5), T-AOC activity in the lymph nodes of BA and in the spleen of BA+APS and BA+GLP was increased (p < 0.05), and T-SOD and GSH-Px activity in the lymph nodes of animals in other groups was found to be increased (p < 0.05). No difference was found in GSH-Px activity in the spleen. Compared with BA, T-AOC activity in the spleen of animals in BA+APS, as well as MDA content in lymph nodes and spleens of animals in BA+EPS were increased (by 33.3%, 40%, and 97.9%, respectively; p < 0.05), while no difference was observed between other groups.

3.5. Effects of plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid on the emission of harmful substances in manure of finishing pigs

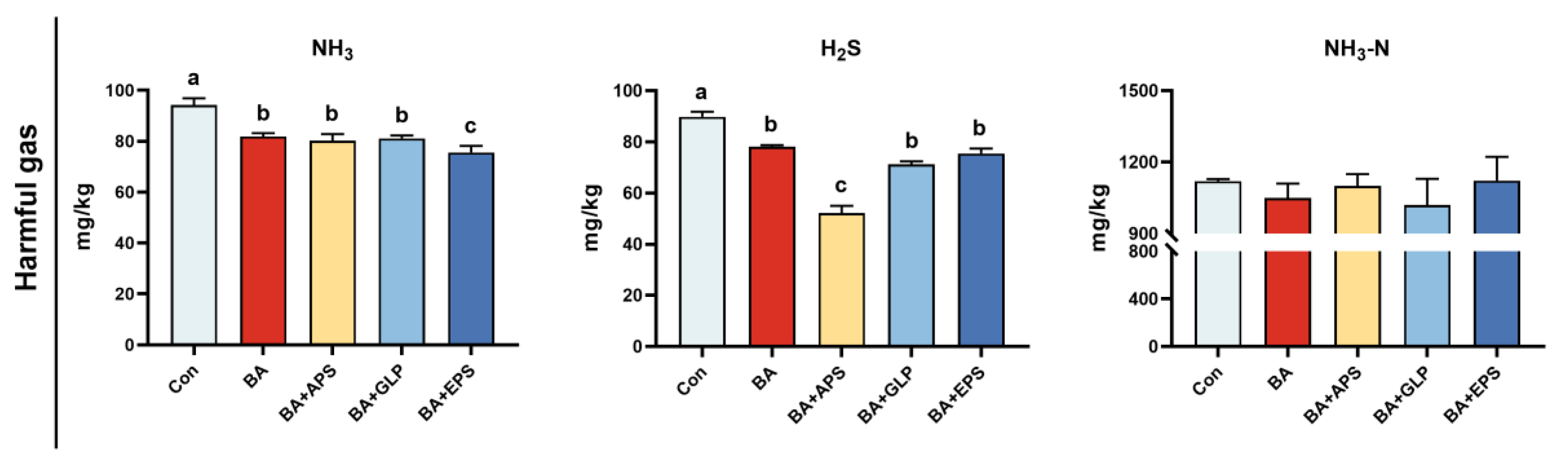

NH

3 and H

2S emissions were decreased in other groups (p < 0.05), compared to the Con. No difference was found in NH

3-N emissions in the faeces. Compared with BA, NH

3 emissions in BA+EPS and H

2S emissions in BA+APS decreased by 9.33% and 50%, respectively (p < 0.05), while no change in NH

3-N was observed (

Figure 6).

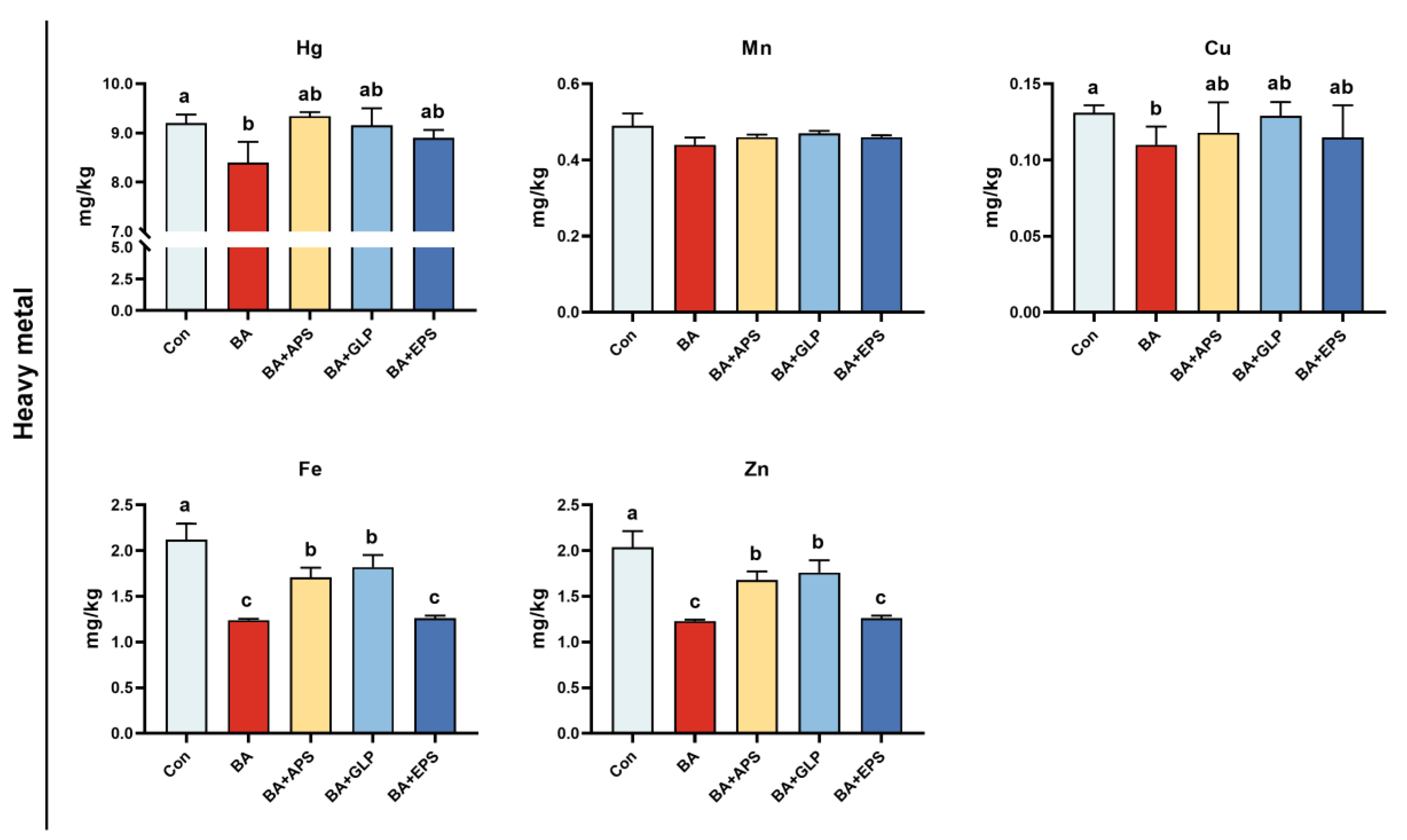

Compared with the Con (

Figure 7), no differences were observed regarding metal manganese emissions in the faeces and urine of animals in each experimental group. Compared to the Con, mercury (Hg), copper (Cu), iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) emissions in BA, as well as iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) emissions in BA+APS, BA+GLP and BA+EPS were decreased, Fe and Zn emissions in BA were decreased (by 37.1% and 40%, respectively; p < 0.05).

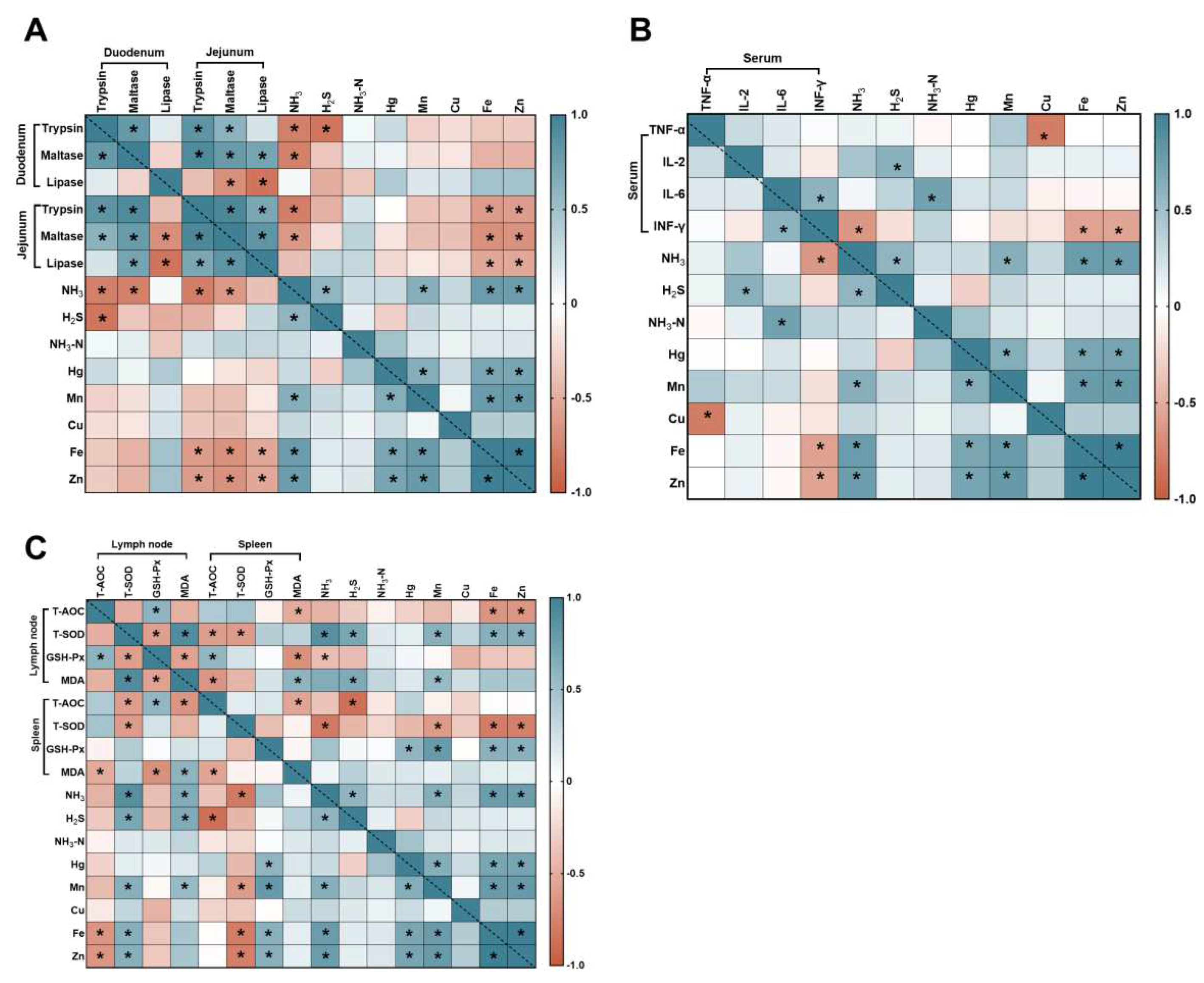

3.6. Correlation analysis

The correlation analyses among intestinal digestive enzymes, serum inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and emissions of harmful gases and heavy metals from fecal pollution in finishing pigs were presented. As described in

Figure 8, in the duodenum, the intestinal digestive enzymes were significantly negative correlated with NH

3, H

2S. In the jejunum, the intestinal digestive enzymes were significantly negative correlated with NH

3, Fe, and Zn. In the serum inflammatory responses, the IL-2 was significantly positive correlated with H

2S. The IL-6 was significantly positive correlated with NH

3-N. The INF-γ was significantly negative correlated with NH

3, Fe, and Zn. The TNF-α was significantly negative correlated with Cu. In the lymph node, the T-AOC was significantly negative correlated with Fe and Zn. The T-SOD was significantly positive correlated with NH

3, H

2S, Mn, Fe, and Zn. The MDA was significantly positive correlated with NH

3, H

2S, and Mn. In the spleen, the T-AOC was significantly negative correlated with H

2S. The T-SOD was significantly negative correlated with NH

3, Mn, Fe, and Zn. The GSH-Px was significantly positive correlated with Hg, Mn, Fe, and Zn. The NH

3 was significantly positive correlated with Mn, Fe and Zn. These results from the correlation analysis supported that the changes in intestinal digestive enzymes, serum inflammatory factors, oxidative stress response and emissions of harmful gases and heavy metals from feces and urine were tightly intertwined during the boric acid and plant polysaccharides to cope with the health of finishing pigs and the emission of harmful gases and heavy metals from feces.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid on animal performance and digestive function

Plant polysaccharides, which are known to possess various bioactive properties, can regulate animal nutritional requirements and potentially improve their digestive capacity, which may allow for the gradual elimination of antibiotics from animal husbandry [

27]. Studies have shown that supplementing broiler chicken feed with Astragalus polysaccharides effectively enhanced their immunity and growth performance [

28]. Similarly, feeding Echinacea polysaccharides to broiler chickens during the growing period increased their weight gain and feed conversion rate, compared to the control group [

29]. Additionally, it has been shown that providing an appropriate amount of boric acid during the growth period of pigs can increase ADG and ADFI [

30].

The functioning of digestive enzymes in the animal intestine is crucial for breaking down and absorbing ingested nutrients. The secretion and activity of these digestive enzymes can be influenced by various factors, such as the parts of the intestine and cells, amount and composition of amino acids, and digestion products of ingested proteins [

31,

32]. Previous studies have shown that supplementation with Astragalus polysaccharides in chicken feed can effectively enhance digestive enzyme activity and improve secretion in the chicken intestine [

33]. Additionally, it has been described that feeding Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides to freshwater shrimp (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) promoted growth and digestive enzyme activity, thus promoting digestive function [

34].

In this study, the combination of different plant polysaccharides and boric acid enhanced trypsin, maltase, and lipase activities in the duodenum and jejunum of finishing pigs, both when compared to the control group and the group supplemented with only boric acid. These results suggest that the combination of different plant polysaccharides and boric acid can improve the ability of the animals to chemically digest nutrients in the intestine. One possible mechanism underlying this effect may be that Astragalus polysaccharides and Echinacea extract can improve the balance of intestinal micro-organisms, thus maintaining intestinal function and promoting overall growth performance and health levels [

35,

36].

4.2. Effects of plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid on immune and antioxidant functions of finishing pigs

Several studies have highlighted that Echinacea can stimulate T-cell phagocytosis and enhance lymphocyte activity in broilers, as well as improving cell antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities [

37]. Therefore, Echinacea can be considered a recommended alternative to antibiotics [

38,

39,

40]. Moreover, Echinacea polysaccharides have been shown to improve immune indices and increase levels of INF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2 in sera [

41], as well as increasing total lgG and γ-interferon levels along with promoting increased expression of important cytokine genes in calves [

42]. Similarly, feeding Astragalus polysaccharides to mice with lung cancer resulted in improvements in white blood cell count, thymus index, spleen index, and cytokine levels, thus effectively regulating immune function [

43]. Moreover, Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides have been shown to possess immunomodulatory effects by increasing serum IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ levels, thus enhancing the activity of NK cells and T-cells, effectively regulating the immune response [

44].

Immune function and spleen lymphocyte proliferation were improved in mice by administering 0.4 mmol/L of boron [

15]. Some of the beneficial effects observed from the combinations used in this paper can be attributed to the individual immune-enhancing effects of boric acid, with its addition yielding a more pronounced improvement in antibody levels and cytokine production in finishing pigs.

Research focused on the antioxidant function of Echinacea has revealed that the addition of 0.5–2.0% Echinacea to animal feed increased the Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity, as well as catalase (CAT) and SOD activity, in the serum and spleen of broilers [

30]. Similarly, adding Echinacea to the diet of crucian carp stimulated their growth performance and elicited an antioxidant response [

45]. Feeding large yellow croaker with 150 mg/kg of Astragalus polysaccharides increased liver T-AOC, GSH-Px, and lysozyme activities [

46]. Furthermore, supplementation with Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides has been shown to alleviate oxidative stress and inflammation in rats by up-regulating SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px activities, increasing IL-10 levels, and preventing excess production of MDA [

47]. The addition of 160 mg/L of boron positively affected the development of ostrich kidneys, inhibited cell apoptosis, regulated enzyme activity, improved the antioxidant system, and enhanced overall antioxidant capacity [

48]. This enhanced antioxidant effect can be attributed to the fact that Astragalus polysaccharides, Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides, and Echinacea extract individually possess antioxidant properties. When combined with boric acid, their effects are synergistically enhanced, resulting in promotion of their effects.

4.3. Effects of plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid on toxic and harmful substances in animal body

Faeces emit pungent and toxic gases such as NH

3 and H

2S, which can pollute the air and threaten human health if discharged in excess, considering that NH

3 causes respiratory diseases and H

2S damages the nervous system [

49]. Plant secondary metabolites have been shown to improve the composition of animal rumen bacterial communities, leading to reduced methane emissions and influencing rumen fermentation [

50]. A previous study has shown that feeding a mixture of plant extracts to growing pigs reduced the emission of harmful gases (NH

3 and H

2S) from their faeces [

51].

In this study, the addition of boric acid alone led to reductions in NH

3 and H

2S emissions, when compared with the control group. However, the combined use of boric acid and plant polysaccharides further reduced NH

3 and H

2S emissions. In particular, when boric acid was combined with

Echinacea polysaccharides, the NH

3 emissions were reduced, while its combination with

Astragalus polysaccharides led to a reduction of H

2S emissions. These results can be attributed to the fact that boric acid can improve animal digestion and promote protein digestion and absorption in the feed, while plant polysaccharides enhance the intestinal microbial community and improve intestinal function [

52]. The addition of polysaccharides to ruminant diets regulates rumen microbial populations, favouring the growth of beneficial micro-organisms while inhibiting methanogenic bacteria, thus helping to reduce methane production [

53,

54]. Thus, the combined supplementation of boric acid and plant polysaccharides enhances gastrointestinal digestion, leading to a reduction in the emission of harmful gases in faeces.

Excessive emission of heavy metal substances in faeces can have detrimental effects on the environment and food safety. Moreover, the long-term accumulation of metals in the soil poses risks to both the atmosphere and agricultural products. Common metal residues found in livestock and poultry faeces include Zn, Fe, lead, chromium, cadmium, arsenic, Hg, and others. In this study, the addition of boric acid alone led to reductions in the emission of Cu, Fe, and Zn, when compared to the control group. However, when boric acid was combined with plant polysaccharides—particularly

Echinacea polysaccharides—further reductions in the emissions of Fe and Zn were noted. This can be attributed to the influence of boron on the mineral metabolism of animals [

55], while the addition of polysaccharides may have had a more effect on mineral absorption [

56]. The combined supplementation enhanced mineral absorption in the body, thereby reducing the emission of heavy metal substances through the faeces and urine [

57].

4.4. Correlation analysis between intestinal digestive enzymes, serum in-flammatory factors, oxidative stress response and emissions of harmful gases and heavy metals from feces and urine.

As one of the most common substrates in biogas production, feces from cows and pigs are generally believed to stabilize the biogas process by providing the necessary nutrients and trace elements [

58], and the generation of harmful gases can have a huge impact on the environment and seriously pollute human health. Research reports indicate that supplementing pigs with lipase in their diet can promote their digestion rate of nutrients, thereby having a beneficial effect on intestinal proteases and reducing NH

3 emissions. This is consistent with our research results, where NH

3 decreases with the increase of digestive enzymes [

59]. Metallic elements present in livestock manure as co-contaminants have the potential to cause terrestrial ecotoxic impacts when the manure is used as fertilizer on agricultural soils, research has found that zinc and copper are the main contributors to the overall impact on soil [

60]. Research has reported that there is a correlation between the three elements Fe, Mn, and Al in the body and the inflammatory response in humans and animals [

61], which is consistent with this conclusion, previous results of this experiment showed that a diet with a copper level of 20 mg·kg-1 significantly increased TNF-α in piglet serum [

62,

63]. This consistent with our results this time, as TNF-α increases, leads to a decrease in the content of Cu element in manure. Further studies have pointed out that heavy metals or toxic elements are one of the interfering factors affecting the absorption process of trace elements from the intestine [

64].

This study analyzed the correlation between changes in harmful gas and element content and intestinal digestive enzymes, serum inflammation, and oxidative stress response, and found that in our study, Intestinal digestive enzymes, serum inflammatory factors, and oxidative stress response were highly correlated with the emissions of three gases, affecting the emission of harmful gases from animals.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the combined use of boric acid and plant polysaccharides in the diets of finishing pigs led to favourable effects, when compared to the use of boric acid alone. In particular, these combinations resulted in a increase in the average daily gain and average daily feed intake of the pigs, while simultaneously reducing the feed-to-gain ratio. Moreover, the combined use of boric acid and plant polysaccharides effectively increased the trypsin and maltase activities in the duodenum and jejunum of the pigs. In this study, the combination of boric acid and three polysaccharides, by increasing the activity of intestinal digestive enzymes, inhibiting the action of inflammatory factors, and reducing immune stress responses, the digestion and absorption of substances can be improved, effectively reducing the release of NH3 and H2S, reduced the content of harmful heavy metals in feces, and thus achieved a reduction in environmental pollution. Among the observed effects, the combination of boric acid and Echinacea polysaccharides presented the most pronounced benefits. This study provided a basis for future research on boric acid and plant polysaccharides as a green feed additive in pigs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D., F.Z., H.F., Y.Z., C.Z., M.R., E.J., and Y.G.; methodology, J.D., F.Z., and E.J.; formal analysis, J.D., F.Z., and C.Z.; resources, J.D., F.Z; data curation, J.D., H.F., and M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.; writing—review and editing, J.D., F.Z., and E.J.; project administration, J.D., Y.Z., and Y.G.; funding acquisition, J.D. and E.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32172816, 32002160), the Anhui Natural Science Foundation Project (2108085MC117, 2208085MC77), the Natural Science Key Foundation of Anhui Education Department (2022AH040032, KJ2021A0868). the Anhui Province Graduate Innovation and Entrepreneurship Practice Project (2022cxcysj196). the Innovation Project for College Students in Anhui Province (S202310879072).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Anhui Science and Technology University (permission number: No. SYXK2020-0053).

Data Availability Statement

Raw data collected and presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kasimanickam, V.; Kasimanickam, M.; Kasimanickam, R. Antibiotics use in food animal production: escalation of antimicrobial resistance: where are we now in combating AMR? Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongyu, P.; Xiaoyu, L.; Qingbo, D.; Hao, C.; Yongping, X. Research progress in the application of chinese herbal medicines in aquaculture: A review. Engineering 2017, 3, 731–737. [Google Scholar]

- Du, D.L.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, K.Q.; Zhi, S.L. Seasonal pollution characteristics of antibiotics on pig farms of different scales. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, R.; Kim, I.H. Effects of Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus subtilis complex on growth performance and faecal noxious gas emissions in growing-finishing pigs. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 1554–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.M.; Han, Q.J.; Wang, K.L.; Xu, Y.L.; Lan, J.H.; Cao, G.T. Astragalus and ginseng polysaccharides improve developmental, intestinal morphological, and immune functional characters of weaned piglets. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.-H.; Yang, F.-X.; Bai, Y.-C.; Zhao, J.-Y.; Hu, M.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Dou, T.-F.; Jia, J.-J. Research progress on the mechanisms underlying poultry immune regulation by plant polysaccharides. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1175848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuge, Z.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-H.; Liu, P.-Q.; Yan, X.-D.; Yue, Y.; Weng, X.-G.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.-F. Effects of astragalus polysaccharide on immune responses of porcine PBMC stimulated with PRRSV or CSFV. PLoS One 2012, 7, e29320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.L.; Zhang, H.R.; Han, Q.J.; Lan, J.H.; Chen, G.Y.; Cao, G.T.; Yang, C.M. Effects of astragalus and ginseng polysaccharides on growth performance, immune function and intestinal barrier in weaned piglets challenged with lipopolysaccharide. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, A.K.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.P.; Chen, H.L.; Zheng, S.S.; Li, Y.L.; Xu, X.; Li, W.F. Echinacea purpurea extract polarizes M1 macrophages in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages through the activation of JNK. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 2664–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, D.K.; Divya, D.; Mohan, K. Potential Role of Plant Polysaccharides as Immunostimulants in Aquaculture – A Review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2023, 23, 951–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H. Supplementation of Non-Starch Polysaccharide Enzymes Cocktail in a Corn-Miscellaneous Meal Diet Improves Nutrient Digestibility and Reduces Carbon Dioxide Emissions in Finishing Pigs. Animals 2020, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, O.G.; Moehn, S.; Edeogu, I.; Price, J.; Leonard, J. Manipulation of Dietary Protein and Nonstarch Polysaccharide to Control Swine Manure Emissions. J. Environ. Qual. 2005, 34, 1461–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlin, B.V.; Muthuvel, S.; Govidasamy, P.; Villavan, M.; Alagawany, M.; Ragab Farag, M.; Dhama, K.; Gopi, M. Role of acidifiers in livestock nutrition and health: A review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haseeb, K.; Wang, J.; Xiao, K.; Yang, K.L.; Peng, K.M. Effects of boron supplementation on expression of hsp70 in the spleen of african ostrich. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 182, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.F.; Jin, E.H.; Deng, J.; Pei, Y.Q.; Ren, M.; Hu, Q.Q.; Gu, Y.F.; Li, S.H. GPR30 mediated effects of boron on rat spleen lymphocyte proliferation, apoptosis, and immune function. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Ren, M.; Liu, W.; Liang, S.; Hu, Q.; Gu, Y.; Li, S. Effect of boron on thymic cytokine expression, hormone secretion, antioxidant functions, cell proliferation, and apoptosis potential via the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 11280–11291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, E.; Li, S.; Ren, M.; Hu, Q.; Gu, Y.; Li, K. Boron affects immune function through modulation of splenic T lymphocyte subsets, cytokine secretion, and lymphocyte proliferation and apoptosis in rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017, 178, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.M.; Han, Q.J.; Wang, K.L.; Xu, Y.L.; Lan, J.H.; Cao, G.T. Astragalus and ginseng polysaccharides improve developmental, intestinal morphological, and immune functional characters of weaned piglets. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, S.F.; Monegue, J.S.; Lindemann, M.D.; Cromwell, G.L.; Matthews, J.C. Dietary supplementation of boron differentially alters expression of borate transporter (NaBCl) mRNA by jejunum and kidney of growing pigs. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 143, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Li, S.; Ren, M.; Hu, Q.; Gu, Y.; Li, K. Boron affects immune function through modulation of splenic T lymphocyte subsets, cytokine secretion, and lymphocyte proliferation and apoptosis in rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017, 178, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Xia, W.; Wei, J.; Ding, X. Therapeutic effect of astragalus polysaccharides on hepatocellular carcinoma H22-bearing mice. Dose-Response 2017, 15, 3517–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Li, L.; Chen, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z. GPP (composition of ganoderma iucidum poly-saccharides and polyporus umbellatus poly-saccharides) enhances innate immune function in mice. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.L.; He, L.P.; Yang, Y.; Liu, F.J.; Cao, Y.; Zuo, J.J. Effects of extracellular polysaccharides of ganoderma lucidum supplementation on the growth performance, blood profile, and meat quality in finisher pigs. Livest. Sci. 2015, 178, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Wang, H.; Yan, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Shi, D.; Guo, S.; Wu, L.; Liu, C. Echinacea purpurea (L.) moench extract suppresses inflammation by inhibition of C3a/C3aR signaling pathway in TNBS-induced ulcerative colitis rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 307, 116221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippe, F.-X.; Canart, B.; Vandenheede, M.; Nicks, B. Comparison of ammonia and greenhouse gas emissions during the fattening of pigs, kept either on fully slatted floor or on deep litter. Livest. Sci. 2007, 111, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, K.A.; Genova, J.L.; Pazdziora, M.L.; Hennig, J.F.; Azevedo, L.B.d.; Veiga, B.R.d.M.; Rodrigues, G.d.A.; Carvalho, S.T.; Paiano, D.; Saraiva, A.; et al. The role of dietary monoglycerides and tributyrin in enhancing performance and intestinal health function in nursery piglets. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 22, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Rajan, D.K.; Muralisankar, T.; Ganesan, A.R.; Marimuthu, K.; Sathishkumar, P. The potential role of medicinal mushrooms as prebiotics in aquaculture: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 1300–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.J. Effect of dietary Astragalus membranaceus polysaccharide on the growth performance and immunity of juvenile broilers. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 3489–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.T.; Chen, C.L.; Wang, C.C.; Yu, B. Growth performance and antioxidant capacity of broilers supplemented with echinacea purpurea L. in the diet. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2012, 21, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, T.A.; Spears, J.W. Effect of dietary boron on growth performance, calcium and phosphorus metabolism, and bone mechanical properties in growing barrows. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 79, 3120–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Liu, C.; Zeng, X.; Yue, L.; Mao, X.; Qiao, S.; Wang, J. Amino acids modulates the intestinal proteome associated with immune and stress response in weaning pig. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 3611–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyoung, H.; Lee, J.J.; Cho, J.H.; Choe, J.; Kang, J.; Lee, H.; Liu, Y.H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.B.; Song, M. Dietary glutamic acid modulates immune responses and gut health of weaned pigs. Animals 2021, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.H.; Liu, C.Y.; Qu, D.; Chen, Y.; Huang, M.M.; Liu, Y.P. Antibacterial evaluation of sliver nanoparticles synthesized by polysaccharides from astragalus membranaceus roots. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 89, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.K.; Zhuo, C.; Teng, C.Y.; Yu, S.M.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Ren, G.M.; Yu, M.; Qu, J.J. Effects of ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides on chronic pancreatitis and intestinal microbiota in mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 93, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthias, A.; Banbury, L.; Bone, K.M.; Leach, D.N.; Lehmann, R.P. Echinacea alkylamides modulate induced immune responses in T-cells. Fitoterapia 2008, 79, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, S.; Zadeh, Z.T.; Torshizi, M.; Omidbaigi, R.; Rokni, H. Effect of the three herbal extracts on growth performance, immune system, blood factors and lntestinal selected bacterial population in broiler chickens. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2011, 13, 527–539. [Google Scholar]

- Gh, G.; Toghyani, M.; Moattar, F. The effects of echinacea purpurea L. (purple coneflower) as an antibiotic growth promoter substitution on performance, carcass characteristics and humoral immune response in broiler chickens. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 2332–2338. [Google Scholar]

- Tierra, M. Echinacea:an effective alternative to antibiotics. J.Herb.Pharmacother 2008, 7, 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, R.; Zhang, P.; Deng, Z.; Jin, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y. Diversity of antioxidant ingredients among Echinacea species. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 170, 113699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogal, M.; Johnston, S.L.; Klein, P.; Schoop, R. Echinacea reduces antibiotic usage in children through respiratory tract infection prevention: a randomized, blinded, controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2021, 26, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.Z.; Zhi, C.P.; Su, Y.L.; Chen, J.X.; Gao, D.B.; Li, S.H.; Shi, D.Y. Effect of echinacea on gut microbiota of immunosuppressed ducks. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seckin, C.; Kalayci, G.A.; Turan, N.; Yilmaz, A.; Yilmaz, H. Immunomodulatory effects of echinacea and pelargonium on the innate and adoptive immunity in calves. Food Agric. Immunol. 2018, 29, 744–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.J.; Long, T.T.; Zhou, L.J.; Bao, Y.X. Immunomodulatory effects of herbal formula of astragalus polysaccharide (APS) and polysaccharopeptide (PSP) in mice with lung cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.H.; Shi, S.S.; Chen, Q.; Lin, S.Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, S.Z.; Chen, C.M. Antitumor and immunomodulatory activities of ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides in glioma-bearing rats. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.i.; Fu, J.; Li, Z.; Fang, W.i.; Zou, J.i. Effects of a dietary administration of purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) on growth, antioxidant activities and 8 miRNAs expressions in crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Aquac. Res. 2016, 47, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, H.; Mai, K.; He, G. Dietary astragalus polysaccharides ameliorates the growth performance, antioxidant capacity and immune responses in turbot (scophthalmus maximus L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 99, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, G.Y.; Lei, A.T.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; Xie, J.H.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, T.J.; Su, D. The protective effects of the ganoderma atrum polysaccharide against acrylamide-induced inflammation and oxidative damage in rats. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaliq, H.; Wang, J.; Xiao, K.; Yang, K.L.; Sun, P.P.; Lei, C.; Qiu, W.W.; Lei, Z.X.; Liu, H.Z.; Song, H.; et al. Boron affects the development of the kidney through modulation of apoptosis, antioxidant capacity, and Nrf2 pathway in the african ostrich chicks. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 186, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Cho, J.H.; Yoo, J.S.; Huang, Y.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, S.O.; Zhou, T.X.; Kim, I.H. Effect of soybean hull supplementation to finishing pigs on the emission of noxious gases from slurry. Anim. Sci. J. 2009, 80, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joch, M.; Mrazek, J.; Skrivanova, E.; Cermak, L.; Marounek, M. Effects of pure plant secondary metabolites on methane production, rumen fermentation and rumen bacteria populations in vitro. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Lim, S.U.; Kim, I.H. Effect of fermented chlorella supplementation on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, blood characteristics, fecal microbial and fecal noxious gas content in growing pigs. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 25, 1742–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Jiang, W.H.; Yang, F.W.; Cheng, Y.L.; Guo, Y.H.; Yao, W.R.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, H. The combination of microbiome and metabolome to analyze the cross-cooperation mechanism of echinacea purpurea polysaccharide with the gut microbiota in vitro and in vivo. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 10069–10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, K.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, T.; Ou, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhong, S.; Tan, K. Role of Polysaccharides from Marine Seaweed as Feed Additives for Methane Mitigation in Ruminants: A Critical Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Cheng, L.; Jonker, A.; Munidasa, S.; Pacheco, D. A review: plant carbohydrate types—the potential impact on ruminant methane emissions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 880115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, C.D.; Herbel, J.L.; Idso, J.P. Dietary boron modifies the effects of vitamin D3 nutrition on indices of energy substrate utilization and mineral metabolism in the chick. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1994, 9, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.H.; Kumar, P.; Kim, J.H.; Patel, R. Removal of heavy metals by polysaccharide: a review. Polym.-Plast. Tech. Mat. 2020, 59, 1770–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.L.; Sun, X.H.; Zhao, J.L.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Y.F.; Fan, L.N.; Li, Z.X.; Sun, Y.Z.; Wang, M.Q.; Wang, F. The effects of zinc deficiency on homeostasis of twelve minerals and trace elements in the serum, feces, urine and liver of rats. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordell, E.; Nilsson, B.; Nilsson Påledal, S.; Karisalmi, K.; Moestedt, J. Co-digestion of manure and industrial waste – The effects of trace element addition. Waste Manage. 2016, 47, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.B.; Cao, S.C.; Liu, J.; Pu, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.F. Effects of dietary energy and lipase levels on nutrient digestibility, digestive physiology and noxious gas emission in weaning pigs. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1963–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydow, M.; Chrzanowski, Ł.; Leclerc, A.; Laurent, A.; Owsianiak, M. Terrestrial ecotoxic impacts stemming from emissions of Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb and Zn from manure: a spatially differentiated assessment in europe. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.-M.; Lee, Y.; Bok, J.D.; Kim, E.B.; Chung, M.I. Analysis of ionomic profiles of canine hairs exposed to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced stress. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016, 172, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Zheng, W.; Guo, R.; Yao, W. Effect of dietary copper level on the gut microbiota and its correlation with serum inflammatory cytokines in Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Zheng, W.; Xue, Y.; Yao, W. Suhuai suckling piglet hindgut microbiome-metabolome responses to different dietary copper levels. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.R.; Han, X.Y.; Wang, Y.Z. Effects on growth and cadmium residues from feeding cadmium-added diets with and without montmorillonite nanocomposite to growing pigs. Vet. Human Toxicol. 2004, 46, 238–241. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on growth performance of finishing pigs (n = 6): ADG: Average daily weight gain; ADFI: average daily feed intake; G/F: gain-to-feed ratios. Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b,c,d Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on growth performance of finishing pigs (n = 6): ADG: Average daily weight gain; ADFI: average daily feed intake; G/F: gain-to-feed ratios. Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b,c,d Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on intestinal digestive enzyme activities of finishing pigs (n = 6): Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b,c,d,e Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on intestinal digestive enzyme activities of finishing pigs (n = 6): Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b,c,d,e Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on cytokines of finishing pigs (n = 6): TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor; IL-2: interleukin-2; IL-6: interleukin-6; IFN-γ: interferon-gamma; Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum poly-saccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on cytokines of finishing pigs (n = 6): TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor; IL-2: interleukin-2; IL-6: interleukin-6; IFN-γ: interferon-gamma; Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum poly-saccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on antioxidant function of finishing pigs (n = 6): T-AOC: Total antioxidant capacity; T-SOD: superoxide dismutase; GSH-Px glutathione peroxidase; MDA malondialdehyde. Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum poly-saccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b,c Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on antioxidant function of finishing pigs (n = 6): T-AOC: Total antioxidant capacity; T-SOD: superoxide dismutase; GSH-Px glutathione peroxidase; MDA malondialdehyde. Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum poly-saccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b,c Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on harmful gas and ammonia nitrogen emissions in faeces and urine of finishing pigs (n = 6): Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum poly-saccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b,c Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on harmful gas and ammonia nitrogen emissions in faeces and urine of finishing pigs (n = 6): Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum poly-saccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b,c Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on metal elements in faeces and urine of finishing pigs (n = 6): Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum poly-saccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b,c Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effects of Adding different plant polysaccharides combined with boric acid in the diet on metal elements in faeces and urine of finishing pigs (n = 6): Con: control; AB: boric acid; APS: Astragalus polysaccharides; GLP: Ganoderma lucidum poly-saccharides; EPS: Echinacea polysaccharides. a,b,c Different letters indicate differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Heatmap of Pearson’s correlation coefficients between intestinal digestive enzymes, serum inflammatory factors, oxidative stress response and emissions of harmful gases and heavy metals from feces and urine. (A) Intestinal digestive enzymes; (B) Serum inflammatory factors; (C) Oxidative stress response. In the panel, orange with a p < 0.05 represents a significant positive correlation, cyan with a p < 0.05 represents a significant negative correlation, and white represents no correlation. * p < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of Pearson’s correlation coefficients between intestinal digestive enzymes, serum inflammatory factors, oxidative stress response and emissions of harmful gases and heavy metals from feces and urine. (A) Intestinal digestive enzymes; (B) Serum inflammatory factors; (C) Oxidative stress response. In the panel, orange with a p < 0.05 represents a significant positive correlation, cyan with a p < 0.05 represents a significant negative correlation, and white represents no correlation. * p < 0.05.

Table 1.

Diet composition and nutrient level of basal diet (air-dried basis).

Table 1.

Diet composition and nutrient level of basal diet (air-dried basis).

| Ingredients |

Content (%) |

Nutrients |

Content |

| Corn |

25.05 |

ME (pig) kcal/kg |

3055.00 |

| Wheat |

25.00 |

DM asf/% |

87.77 |

| Wheat middings mix |

18.50 |

CP/% |

13.51 |

| Wheat flour |

15.00 |

CEE/% |

2.97 |

| Rice bran meal |

12.50 |

C-fiber/% |

3.68 |

| Limestone (40) |

1.03 |

Ca/% |

0.75 |

| Calcium hydrogen phosphate |

0.95 |

Avail P/% |

0.30 |

| Soybean oil |

0.80 |

Total AA/% |

12.15 |

| Sodium bicarbonate |

0.28 |

Total lys/% |

0.81 |

| Edible salt |

0.20 |

Total met/% |

0.25 |

| 98.5% Lys-HCl |

0.58 |

|

|

| 98.5% L-threonine |

0.10 |

|

|

| 33% Ethoxyquin |

0.03 |

|

|

| Total |

100.00 |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).