Submitted:

18 May 2023

Posted:

19 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental animals and experimental design

2.2. Sample collection

2.3. Gut microbiota analyses and bioinformatics

2.4. Predicted functions of pig gut microbiota

2.5. Quantification of short chain fatty acids (SCFA) and bile acids

2.6. Statistical analyses

3. Results

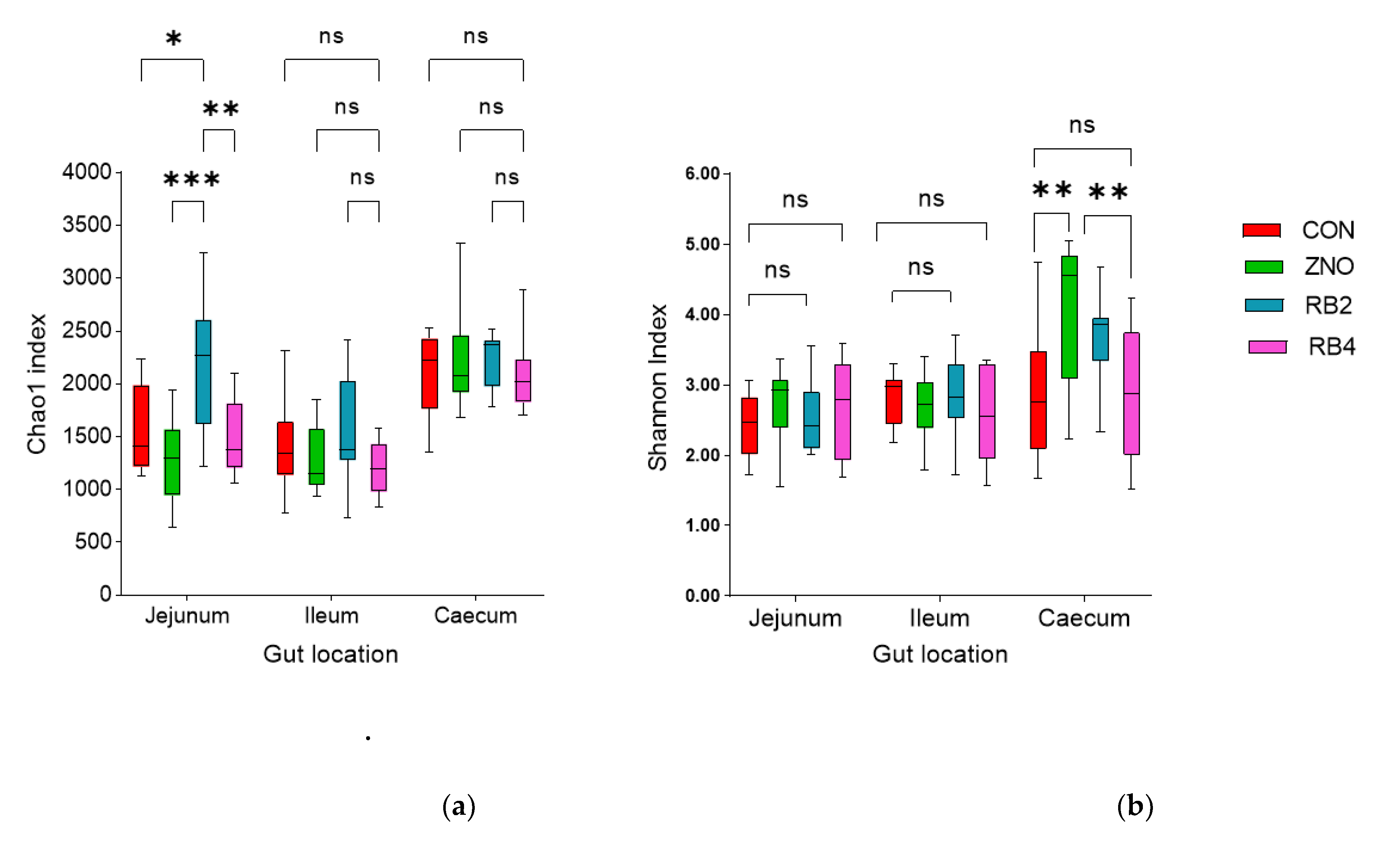

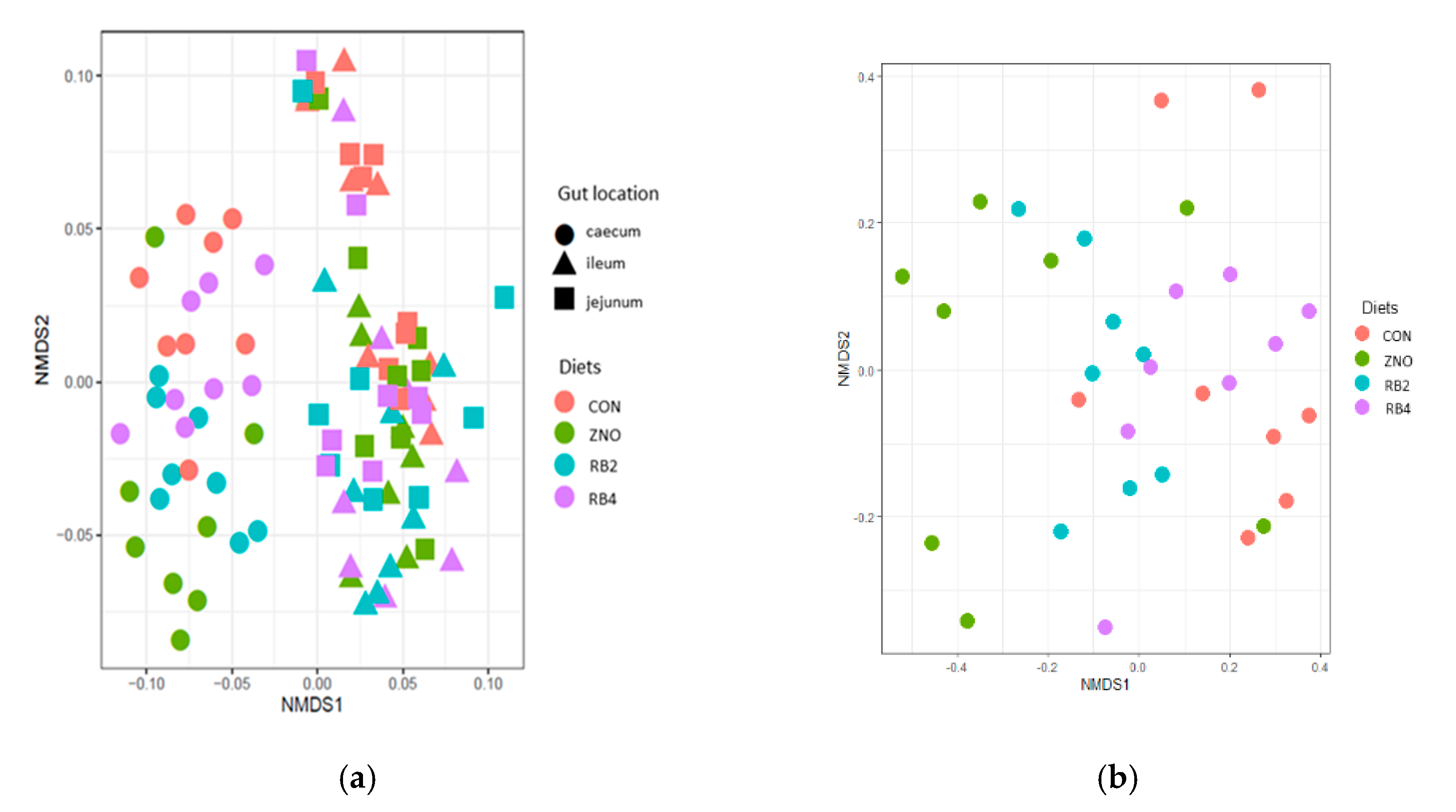

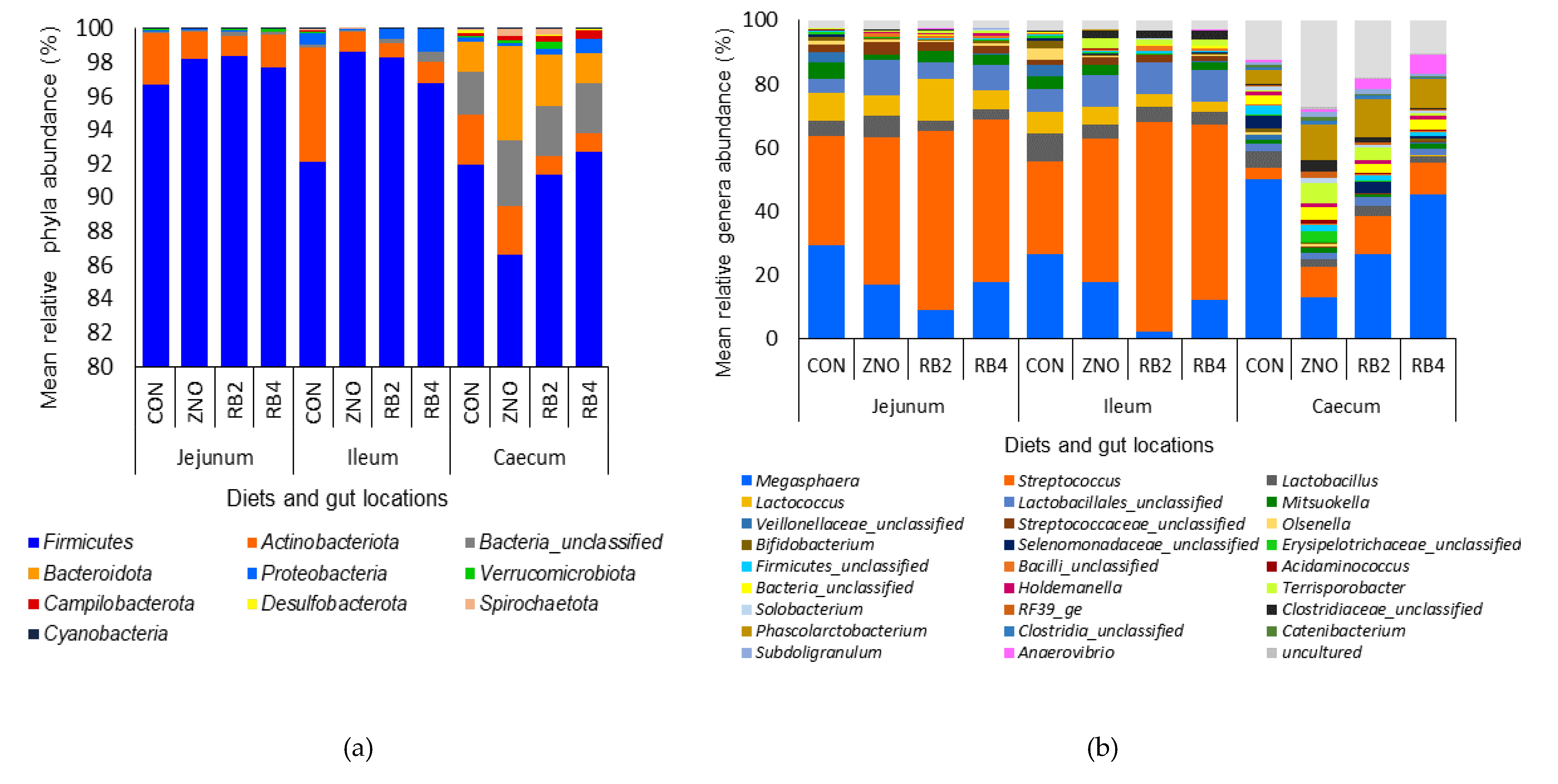

3.1. Effect of diets on gut microbial diversity and taxonomic composition

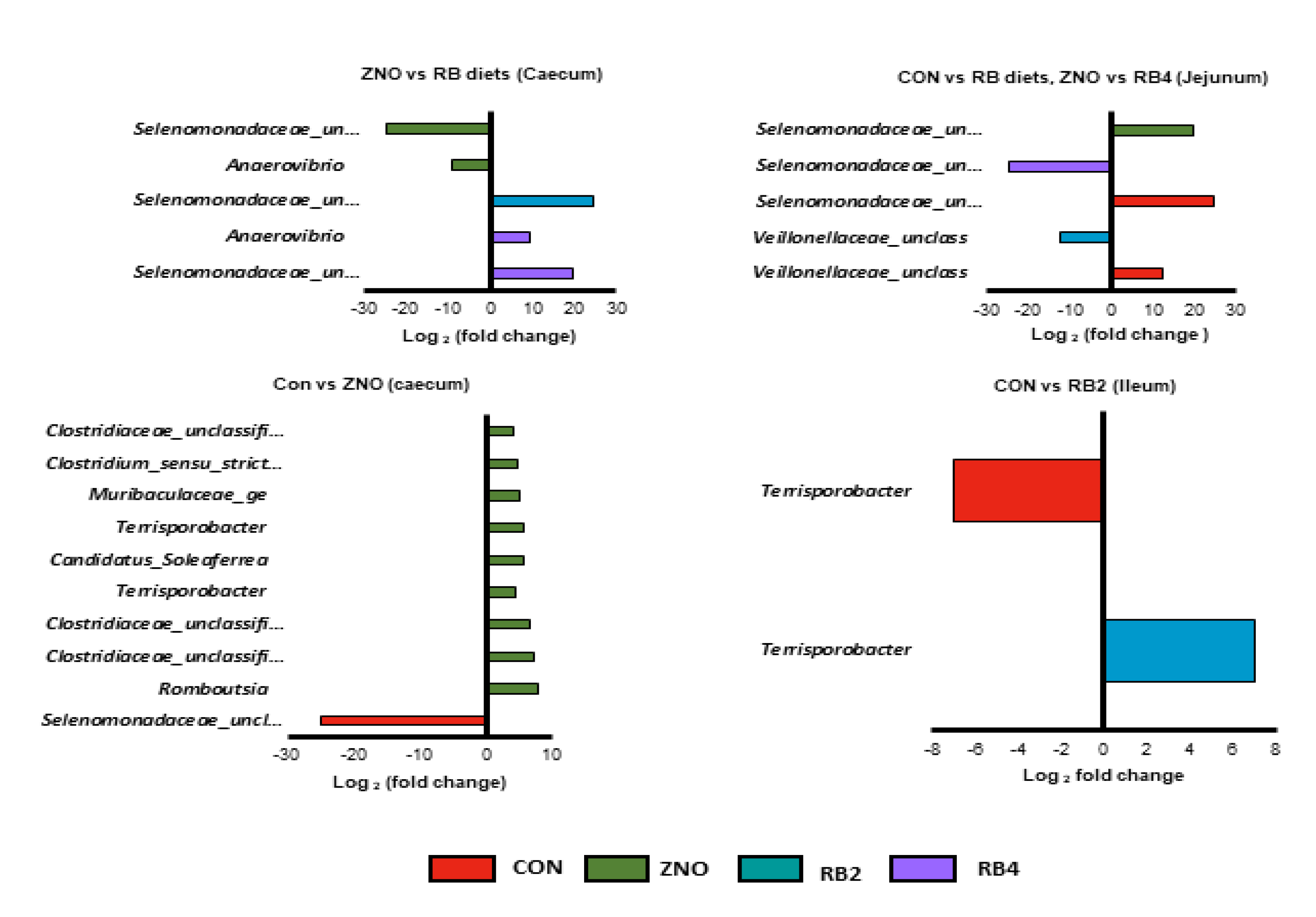

3.2. Differential abundant genera modulated by the diets

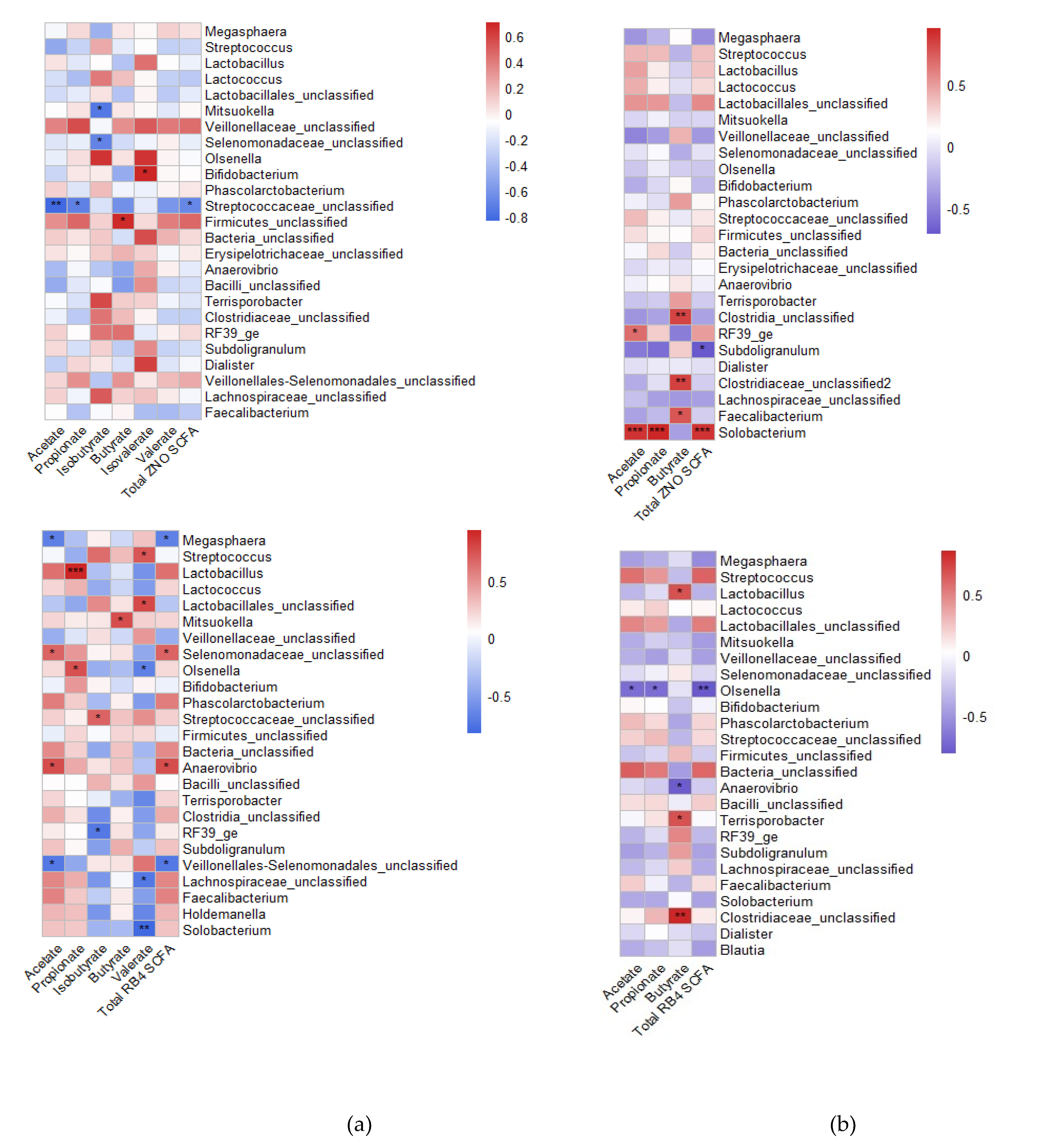

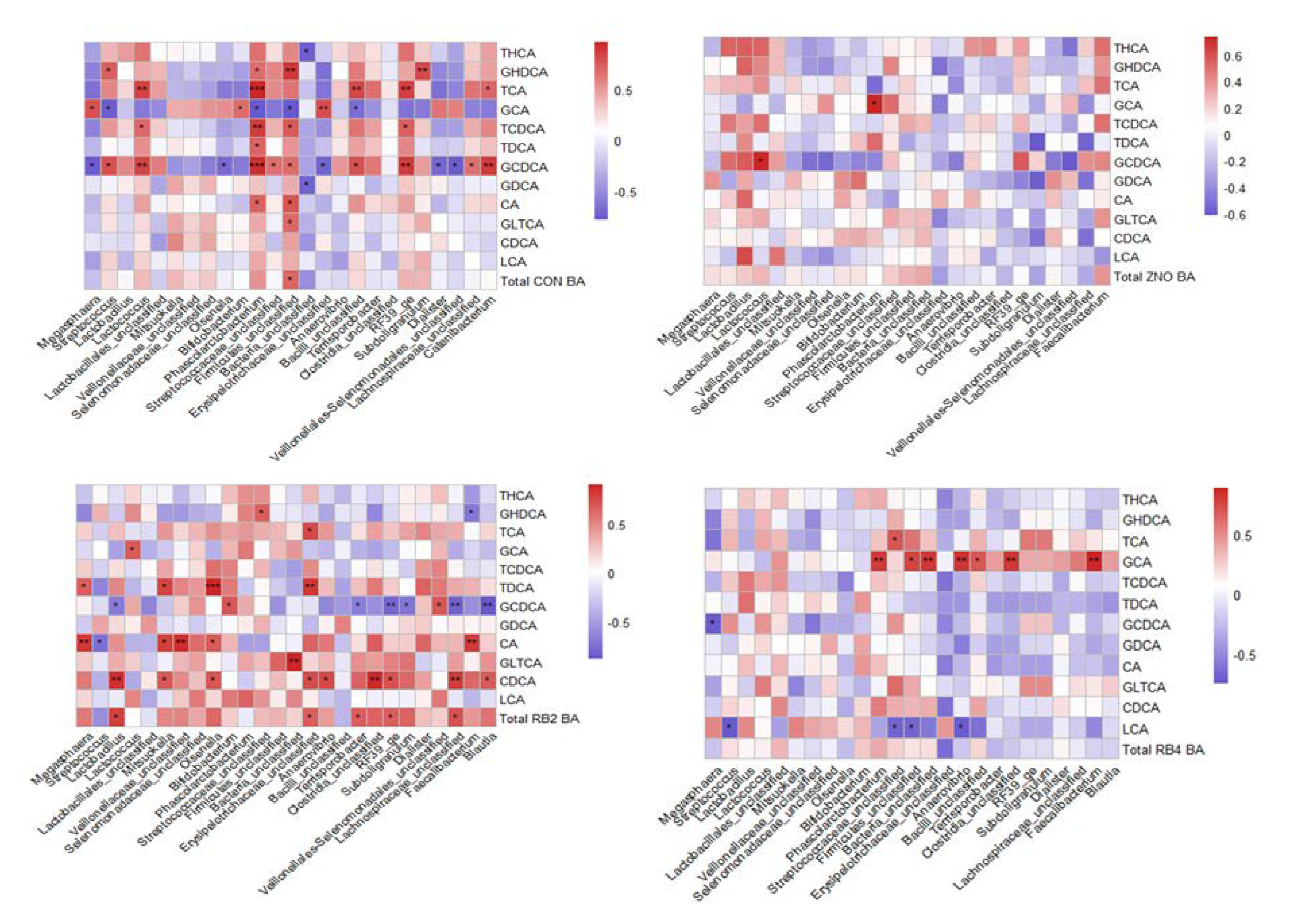

3.3. Metabolite profile and association with gut microbial composition

3.4. Predicted gut microbiota functions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, H.B.; Isaacson, R.E. The pig gut microbial diversity: Understanding the pig gut microbial ecology through the next generation high throughput sequencing. Veter- Microbiol. 2015, 177, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevarra, R.B.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Seok, M.-J.; Kim, D.W.; Na Kang, B.; Johnson, T.J.; Isaacson, R.E.; Kim, H.B. Piglet gut microbial shifts early in life: causes and effects. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, G.; Ma, S.; Zhu, Z.; Su, Y.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Mackie, R.; Liu, J.; Mu, C.; Huang, R.; Smidt, H.; et al. Age, introduction of solid feed and weaning are more important determinants of gut bacterial succession in piglets than breed and nursing mother as revealed by a reciprocal cross-fostering model. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1566–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevarra, R.B.; Hong, S.H.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, B.-R.; Shin, J.; Lee, J.H.; Na Kang, B.; Kim, Y.H.; Wattanaphansak, S.; Isaacson, R.; et al. The dynamics of the piglet gut microbiome during the weaning transition in association with health and nutrition. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valeriano, V.; Balolong, M.; Kang, D.-K. Probiotic roles ofLactobacillussp. in swine: insights from gut microbiota. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 122, 554–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Yao, W.; Li, J.; Shao, Y.; He, Q.; Xia, J.; Huang, F. Dietary garcinol supplementation improves diarrhea and intestinal barrier function associated with its modulation of gut microbiota in weaned piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Ma, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, T. Effects of Dietary Protein Level on the Microbial Composition and Metabolomic Profile in Postweaning Piglets. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huting, A.M.; Middelkoop, A.; Guan, X.; Molist, F. Using Nutritional Strategies to Shape the Gastro-Intestinal Tracts of Suckling and Weaned Piglets. Animals 2021, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Tan, B.; Song, M.; Ji, P.; Kim, K.; Yin, Y.; Liu, Y. Nutritional Intervention for the Intestinal Development and Health of Weaned Pigs. Front. Veter- Sci. 2019, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, R.; Oh, J.K.; Song, J.H.; Kang, D.-K. Gut microbiome-produced metabolites in pigs: a review on their biological functions and the influence of probiotics. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2022, 64, 671–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Kang, D.J.; Hylemon, P.B.; Bajaj, J.S. Bile acids and the gut microbiome. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 30, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, B.S.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Donovan, D.M.; Gay, C.G. Alternatives to antibiotics: a symposium on the challenges and solutions for animal production. Anim. Heal. Res. Rev. 2013, 14, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, R.; Kyriazakis, I.; Carroll, S.; Reynolds, F.; Wellock, I.; Broom, L.; Miller, H. Effect of rearing environment and dietary zinc oxide on the response of group-housed weaned pigs to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli O149 challenge. Animal 2011, 5, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becattini, S.; Taur, Y.; Pamer, E.G. Antibiotic-Induced Changes in the Intestinal Microbiota and Disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 458–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Xiao, K.; Song, J.; Luan, Z. Effects of zinc oxide supported on zeolite on growth performance, intestinal microflora and permeability, and cytokines expression of weaned pigs. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2013, 181, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Xu, Q.; Wang, C.; Zou, X.; Lu, J. Supplemental-coated zinc oxide relieves diarrhoea by decreasing intestinal permeability in weanling pigs. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2019, 47, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Su, J.-Q.; An, X.-L.; Huang, F.-Y.; Rensing, C.; Brandt, K.K.; Zhu, Y.-G. Feed additives shift gut microbiota and enrich antibiotic resistance in swine gut. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 621, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D.B.; Chénier, M.R. Antimicrobial use in swine production and its effect on the swine gut microbiota and antimicrobial resistance. Can. J. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.; Gao, K.; Peng, Y.; Mu, C.L.; Zhu, W.Y. Antibiotic-induced alterations of the gut microbiota and microbial fermentation in protein parallel the changes in host nitrogen metabolism of growing pigs. Animal 2019, 13, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starke, I.C.; Pieper, R.; Neumann, K.; Zentek, J.; Vahjen, W. The impact of high dietary zinc oxide on the development of the intestinal microbiota in weaned piglets. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 87, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, R.; Vahjen, W.; Neumann, K.; Van Kessel, A.G.; Zentek, J. Dose-dependent effects of dietary zinc oxide on bacterial communities and metabolic profiles in the ileum of weaned pigs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2011, 96, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciesinski, L.; Guenther, S.; Pieper, R.; Kalisch, M.; Bednorz, C.; Wieler, L.H. High dietary zinc feeding promotes persistence of multi-resistant E. coli in the swine gut. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0191660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahjen, W.; Pieper, R.; Zentek, J. Increased dietary zinc oxide changes the bacterial core and enterobacterial composition in the ileum of piglets1. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 2430–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schokker, D.; Zhang, J.; Vastenhouw, S.A.; Heilig, H.G.H.J.; Smidt, H.; Rebel, J.M.J.; Smits, M.A. Long-Lasting Effects of Early-Life Antibiotic Treatment and Routine Animal Handling on Gut Microbiota Composition and Immune System in Pigs. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0116523–e0116523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonetti, A.; Tugnoli, B.; Piva, A.; Grilli, E. Towards Zero Zinc Oxide: Feeding Strategies to Manage Post-Weaning Diarrhea in Piglets. Animals 2021, 11, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.; Kyvsgaard, N.C.; Battisti, A.; Baptiste, K.E. Environmental and public health related risk of veterinary zinc in pig production - Using Denmark as an example. Environ. Int. 2018, 114, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazdankhah, S.; Rudi, K.; Bernhoft, A. Zinc and copper in animal feed – development of resistance and co-resistance to antimicrobial agents in bacteria of animal origin. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2014, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednorz, C.; Oelgeschläger, K.; Kinnemann, B.; Hartmann, S.; Neumann, K.; Pieper, R.; Bethe, A.; Semmler, T.; Tedin, K.; Schierack, P.; et al. The broader context of antibiotic resistance: Zinc feed supplementation of piglets increases the proportion of multi-resistant Escherichia coli in vivo. Int. J. Med Microbiol. 2013, 303, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, S.P.A.; do Nascimento, H.M.A.; Sampaio, K.B.; de Souza, E.L. A review on bioactive compounds of beet (beta vulgaris l. Subsp. Vulgaris) with special emphasis on their beneficial effects on gut microbiota and gastrointestinal health. Critical Rev Food Sci and Nutr 2021, 61, 2022–2033. [Google Scholar]

- Baião, D.D.S.; da Silva, V.; Paschoalin, M. Beetroot, a Remarkable Vegetable: Its Nitrate and Phytochemical Contents Can be Adjusted in Novel Formulations to Benefit Health and Support Cardiovascular Disease Therapies. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninfali, P.; Angelino, D. Nutritional and functional potential of Beta vulgaris cicla and rubra. Fitoterapia 2013, 89, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemzer, B.; Pietrzkowski, Z.; Spórna, A.; Stalica, P.; Thresher, W.; Michałowski, T.; Wybraniec, S. Betalainic and nutritional profiles of pigment-enriched red beet root (Beta vulgaris L.) dried extracts. Food Chem. 2010, 127, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhikara, N.; Kushwaha, K.; Sharma, P.; Gat, Y.; Panghal, A. Bioactive compounds of beetroot and utilization in food processing industry: A critical review. Food Chem. 2018, 272, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, B.; Peláez, C.; Martínez-Cuesta, M.C.; Parajó, J.C.; Alonso, J.L.; Requena, T. Emerging prebiotics obtained from lemon and sugar beet byproducts: Evaluation of their in vitro fermentability by probiotic bacteria. LWT 2019, 109, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danneskiold-Samsøe, N.B.; Barros, H.D.d.F.Q.; Santos, R.; Bicas, J.L.; Cazarin, C.B.B.; Madsen, L.; Kristiansen, K.; Pastore, G.M.; Brix, S.; Júnior, M.R.M. Interplay between food and gut microbiota in health and disease. Food Res. Int. 2018, 115, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Merwe, M. Gut microbiome changes induced by a diet rich in fruits and vegetables. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2021, 72, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, T.; Howatson, G.; West, D.J.; Stevenson, E.J. The Potential Benefits of Red Beetroot Supplementation in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2801–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Hathan, B.S. Chemical composition, functional properties and processing of beetroot—a review. Int J Sci and Eng Res 2014, 5, 679–684. [Google Scholar]

- Klewicka, E.; Zduńczyk, Z.; Juśkiewicz, J.; Klewicki, R. Effects of lactofermented beetroot juice alone or with n-nitroso-n-methylurea on selected metabolic parameters, composition of the microbiota adhering to the gut epithelium and antioxidant status of rats. Nutrients 2015, 7, 5905–5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.U.; Butt, M.S.; Randhawa, M.A.; Shahid, M. Nephroprotective effects of red beetroot-based beverages against gentamicin-induced renal stress. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, P.; Houshialsadat, Z.; Gaeini, Z.; Bahadoran, Z.; Azizi, F. Functional properties of beetroot (Beta vulgaris) in management of cardio-metabolic diseases. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wootton-Beard, P.C.; Brandt, K.; Fell, D.; Warner, S.; Ryan, L. Effects of a beetroot juice with high neobetanin content on the early-phase insulin response in healthy volunteers. J. Nutr. Sci. 2014, 3, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, D.V.T.; Pereira, A.D.; Boaventura, G.T.; Ribeiro, R.S.d.A.; Verícimo, M.A.; de Carvalho-Pinto, C.E.; Baião, D.d.S.; Del Aguila, E.M.; Paschoalin, V.M.F. Short-Term Betanin Intake Reduces Oxidative Stress in Wistar Rats. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinedo-Gil, J.; Tomás-Vidal, A.; Jover-Cerdá, M.; Tomás-Almenar, C.; Sanz-Calvo, M.Á.; Martín-Diana, A.B. Red beet and betaine as ingredients in diets of rainbow trout (oncorhynchus mykiss): Effects on growth performance, nutrient retention and flesh quality. Arch Anim Nutr 2017, 71, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinedo-Gil, J.; Martín-Diana, A.B.; Bertotto, D.; Sanz-Calvo, M. .; Jover-Cerdá, M.; Tomás-Vidal, A. Effects of dietary inclusions of red beet and betaine on the acute stress response and muscle lipid peroxidation in rainbow trout. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 44, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, G.; Wu, X.; Chen, D.; Yu, B.; He, J. Adaptation of gut microbiome to different dietary nonstarch polysaccharide fractions in a porcine model. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, C.; Howell, K.; Padayachee, A.; Comino, T.; Chhan, R.; Zhang, P.; Ng, K.; Cottrell, J.J.; Dunshea, F.R. Effect of a polyphenol-rich plant matrix on colonic digestion and plasma antioxidant capacity in a porcine model. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 57, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, H.; Xie, P.; Li, Z.; Yin, Y.; Blachier, F.; Kong, X. Dietary supplementation with fermented Mao-tai lees beneficially affects gut microbiota structure and function in pigs. AMB Express 2019, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, T.; O’neill, H.M.; Bedford, M.; McDermott, K.; Miller, H. Effect of xylanase and xylo-oligosaccharide supplementation on growth performance and faecal bacterial community composition in growing pigs. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2021, 274, 114822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozich, J.J.; Westcott, S.L.; Baxter, N.T.; Highlander, S.K.; Schloss, P.D. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5112–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, D.H.; Tyson, G.W.; Hugenholtz, P.; Beiko, R.G. STAMP: Statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3123–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for rna-seq data with deseq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, S.; Weinmaier, T.; Schmidt, B.L.; Albertson, D.G.; Poloso, N.J.; Dabbagh, K.; DeSantis, T.Z. Piphillin: Improved Prediction of Metagenomic Content by Direct Inference from Human Microbiomes. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0166104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langille, M.G.I.; Zaneveld, J.; Caporaso, J.G.; McDonald, D.; Knights, D.; Reyes, J.A.; Clemente, J.C.; Burkepile, D.E.; Vega Thurber, R.L.; Knight, R.; et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.E.; Bedford, M.R.; Miller, H.M. The effects of xylanase on grower pig performance, concentrations of volatile fatty acids and peptide YY in portal and peripheral blood. Animal 2018, 12, 2499–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, W.; Lee, Y.-K.; Xie, J.; Zhang, H. Spatial Heterogeneity and Co-occurrence of Mucosal and Luminal Microbiome across Swine Intestinal Tract. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. How to: Use the psych package for factor analysis and data reduction. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University, Department of Psychology 2016.

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alou, M.T.; Lagier, J.-C.; Raoult, D. Diet influence on the gut microbiota and dysbiosis related to nutritional disorders. Hum. Microbiome J. 2016, 1, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, T.E.; Houghton, D.; Stewart, C.J.; Blain, A.P.; McMahon, N.; Siervo, M.; West, D.J.; Stevenson, E.J. Whole beetroot consumption reduces systolic blood pressure and modulates diversity and composition of the gut microbiota in older participants. NFS J. 2020, 21, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüello, H.; Estellé, J.; Leonard, F.C.; Crispie, F.; Cotter, P.D.; O’sullivan, O.; Lynch, H.; Walia, K.; Duffy, G.; Lawlor, P.G.; et al. Influence of the Intestinal Microbiota on Colonization Resistance to Salmonella and the Shedding Pattern of Naturally Exposed Pigs. mSystems 2019, 4, e00021–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, H.; Smidt, H. Microbiota development in piglets. The suckling weaned piglet 2020, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Fang, C.; Zhao, L.; Chen, F. The Maturing Development of Gut Microbiota in Commercial Piglets during the Weaning Transition. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, A.; He, M.; Mao, L.; Zou, H.; Peng, Q.; Xue, B.; Wang, L.; et al. Coated zinc oxide improves intestinal immunity function and regulates microbiota composition in weaned piglets. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 2123–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Zhu, C.; Chen, S.; Gao, L.; Lv, H.; Feng, R.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Z. Dietary High Zinc Oxide Modulates the Microbiome of Ileum and Colon in Weaned Piglets. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namkung, H.; Gong, J.; Yu, H.; de Lange, C.F.M. Effect of pharmacological intakes of zinc and copper on growth performance, circulating cytokines and gut microbiota of newly weaned piglets challenged with coliform lipopolysaccharides. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 86, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yin, J.; Xu, K.; Li, T.; Yin, Y. What Is the Impact of Diet on Nutritional Diarrhea Associated with Gut Microbiota in Weaning Piglets: A System Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awati, A.; Williams, B.A.; Bosch, M.W.; Gerrits, W.J.J.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Effect of inclusion of fermentable carbohydrates in the diet on fermentation end-product profile in feces of weanling piglets1. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 2133–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlmans, M.A.; Korpela, K.; Riksen-Walraven, J.M.; de Vos, W.M.; de Weerth, C. Maternal prenatal stress is associated with the infant intestinal microbiota. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 53, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.B.; Borewicz, K.; White, B.A.; Singer, R.S.; Sreevatsan, S.; Tu, Z.J.; Isaacson, R.E. Longitudinal investigation of the age-related bacterial diversity in the feces of commercial pigs. Veter- Microbiol. 2011, 153, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looft, T.; Johnson, T.A.; Allen, H.K.; Bayles, D.O.; Alt, D.P.; Stedtfeld, R.D.; Sul, W.J.; Stedtfeld, T.M.; Chai, B.; Cole, J.R.; et al. In-feed antibiotic effects on the swine intestinal microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 1691–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Nie, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fan, Q.; Yan, X. Gradual Changes of Gut Microbiota in Weaned Miniature Piglets. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; He, X.; Yang, H. Microbial composition in different gut locations of weaning piglets receiving antibiotics. Asian-Australasian J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 30, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluske, J.R. Feed- and feed additives-related aspects of gut health and development in weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 4, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.P.; Rubio, L.A.; Duncan, S.H.; Donachie, G.E.; Holtrop, G.; Lo, G.; Farquharson, F.M.; Wagner, J.; Parkhill, J.; Louis, P.; et al. Pivotal Roles for pH, Lactate, and Lactate-Utilizing Bacteria in the Stability of a Human Colonic Microbial Ecosystem. mSystems 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Duncan, S.H.; Sheridan, P.O.; Walker, A.W.; Flint, H.J. Microbial lactate utilisation and the stability of the gut microbiome. Gut Microbiome 2022, 3, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, N.; Duncan, S.H.; Young, P.; Belenguer, A.; McWilliam Leitch, C.; Scott, K.P.; Flint, H.J.; Louis, P. Phylogenetic distribution of three pathways for propionate production within the human gut microbiota. ISME J. 2014, 8, 1323–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brestenský, M.; Nitrayová, S.; Bomba, A.; Patráš, P.; Strojný, L.; Szabadošová, V.; Pramuková, B.; Bertková, I. The content of short chain fatty acids in the jejunal digesta, caecal digesta and faeces of growing pigs. Livest Sci 2017, 205, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.E.; Kim, S.W. Intestinal microbiota and its interaction to intestinal health in nursery pigs. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 8, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, R.; Liu, R.; Li, L. Goat milk fermented by lactic acid bacteria modulates small intestinal microbiota and immune responses. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 65, 103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I.I.; Honda, K. Intestinal Commensal Microbes as Immune Modulators. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Xie, G.X.; Jia, W.P. Bile acid-microbiota crosstalk in gastrointestinal inflammation and carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat 2018, 15, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winston, J.A.; Theriot, C.M. Diversification of host bile acids by members of the gut microbiota. Gut Microbes 2019, 11, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Zhang, F.; Chen, L.; Yang, Q.; Su, H.; Yang, X.; He, H.; Ling, M.; Zheng, J.; Duan, C.; et al. Dietary chenodeoxycholic acid improves growth performance and intestinal health by altering serum metabolic profiles and gut bacteria in weaned piglets. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Gui, W.; Koo, I.; Smith, P.B.; Allman, E.L.; Nichols, R.G.; Rimal, B.; Cai, J.; Liu, Q.; Patterson, A.D. The microbiome modulating activity of bile acids. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 979–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, A.; Sayin, S.I.; Marschall, H.-U.; Bäckhed, F. Intestinal Crosstalk between Bile Acids and Microbiota and Its Impact on Host Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O. Insights into the Role of Erysipelotrichaceae in the Human Host. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, N.W.; De Zoete, M.R.; Cullen, T.W.; Barry, N.A.; Stefanowski, J.; Hao, L.; Degnan, P.H.; Hu, J.; Peter, I.; Zhang, W.; et al. Immunoglobulin A Coating Identifies Colitogenic Bacteria in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cell 2014, 158, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson-Trick, E.C.L.; Getz, L.J.; Slaine, P.D.; Thornbury, M.; Lamoureux, E.; Cook, J.; Langille, M.G.I.; Murray, L.E.; McCormick, C.; Rohde, J.R.; et al. Taxonomic differences of gut microbiomes drive cellulolytic enzymatic potential within hind-gut fermenting mammals. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0189404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Tena, M.; del Pulgar, E.M.G.; Benítez-Páez, A.; Sanz, Y.; Alegría, A.; Lagarda, M.J. Plant sterols and human gut microbiota relationship: An in vitro colonic fermentation study. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 44, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.C.; Bandeira, V.; Fonseca, C.; Cunha, M.V. Egyptian Mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon) Gut Microbiota: Taxonomical and Functional Differences across Sex and Age Classes. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, I.; Perdicaro, D.J.; Brown, A.W.; Hammons, S.; Carden, T.J.; Carr, T.P.; Eskridge, K.M.; Walter, J. Diet-Induced Alterations of Host Cholesterol Metabolism Are Likely To Affect the Gut Microbiota Composition in Hamsters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, I.; Wallace, G.; Zhang, C.; Legge, R.; Benson, A.K.; Carr, T.P.; Moriyama, E.N.; Walter, J. Diet-Induced Metabolic Improvements in a Hamster Model of Hypercholesterolemia Are Strongly Linked to Alterations of the Gut Microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 4175–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria, U.; Arias, N.; Boqué, N.; Macarulla, M.; Portillo, M.; Martínez, J.; Milagro, F. Reshaping faecal gut microbiota composition by the intake of trans-resveratrol and quercetin in high-fat sucrose diet-fed rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Q.; Yang, G.-Q. Betacyanins from Portulaca oleracea L. ameliorate cognition deficits and attenuate oxidative damage induced by D-galactose in the brains of senescent mice. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients (%) | Control (CON) | Diet with ZnO (ZNO) | 2% red beetroot supplemented diet (RB2) | 4% red beet root supplemented diet (RB4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barley | 15.00 | 15.00 | 14.70 | 14.40 |

| Wheat | 28.17 | 28.17 | 27.51 | 26.95 |

| Micronized maize bulk | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.45 | 2.40 |

| Micronized oats | 5.00 | 5.00 | 4.90 | 4.80 |

| Fishmeal bulk | 6.00 | 6.00 | 5.88 | 5.76 |

| Soya hypro | 18.16 | 18.16 | 17.80 | 17.43 |

| Full fat soybean | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.45 | 2.40 |

| Pig weaner premix | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| Whey powder bulk | 13.89 | 13.89 | 13.61 | 13.33 |

| Potato protein | 1.60 | 1.60 | 1.57 | 1.54 |

| Sugar/sucrose | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.60 |

| L-Lysine | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.27 |

| DL-Methionine | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| L-Threonine | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| L-Tryptophan | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| L-Valine | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Vitamin E | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Pan-tek robust | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Sucram | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Benzoic acid | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| Pigzin (zinc oxide) | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Di-calcium phosphate | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.08 |

| Sodium carbonate | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Sipernat 50 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Red beetroot | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 |

| Soya oil | 3.40 | 3.40 | 3.33 | 3.26 |

| Total (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Dry matter (%) | 89.93 | 89.65 | 89.47 | 89.01 |

| Analysed nutrient | ||||

| Ash (%) | 6.80 | 7.50 | 6.70 | 6.60 |

| Ether extract (%) | 6.73 | 6.99 | 6.62 | 5.92 |

| Crude protein (%) | 21.30 | 21.30 | 20.70 | 20.40 |

| Crude fibre (%) | 1.90 | 1.50 | 1.80 | 2.20 |

| Zinc (mg/kg) | 422.00 | 2252.00 | 193.00 | 187.00 |

|

Phylum |

Diets | Gut locations | dSEM | P value | |||||||

| CON | ZNO | RB2 | RB4 | Jejunum | Ileum | Caecum | fL | eD | gL* D | ||

| Firmicutes | 93.58a | 94.48a | 96.01a | 95.72a | 97.74a | 96.46a | 90.64b | 0.617 | 0.000 | 0.312 | 0.062 |

| Actinobacteriota | 4.25a | 1.88ab | 1.06b | 1.42b | 1.93a | 2.51a | 2.02a | 0.347 | 0.733 | 0.004 | 0.224 |

| Bacteria unclassified | 0.95a | 1.37a | 1.13a | 1.26a | 0.17b | 0.28b | 3.09a | 0.206 | 0.000 | 0.796 | 0.800 |

| Bacteroidota | 0.61a | 1.86a | 1.03a | 0.59a | 0.003b | 0.005b | 3.06a | 0.248 | 0.000 | 0.067 | 0.029 |

| Proteobacteria | 0.31ab | 0.11b | 0.31ab | 0.71a | 0.03b | 0.66a | 0.39a | 0.068 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.126 |

| Verrucomicrobiota | 0.09a | 0.06a | 0.18a | 0.08a | 0.11a | 0.04a | 0.16a | 0.026 | 0.187 | 0.389 | 0.132 |

| Campilobacterota | 0.09a | 0.08a | 0.13a | 0.16a | 0.01b | 0.01b | 0.32a | 0.041 | 0.002 | 0.916 | 0.921 |

| Desulfobacterota | 0.07a | 0.01a | 0.03a | 0.04a | 0.004b | 0.001b | 0.11a | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.230 | 0.213 |

| Spirochaetota | 0.05a | 0.13a | 0.11a | 0.01a | 0.001b | 0.03b | 0.19a | 0.026 | 0.003 | 0.259 | 0.058 |

| SFCA | Diets | P value | ||||||

| CON | ZNO | RB2 | RB4 | SEM | *L | #D | +L*D | |

| Acetate | 69.14a | 54.76b | 63.81ab | 56.64b | 3.32 | < 0.01 | < 0.05 | > 0.05 |

| Propionate | 23.83a | 17.04d | 20.34b | 19.16c | 1.42 | < 0.05 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Isobutyrate | 2.59a | 1.60b | 1.79b | 0.86c | 0.36 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 |

| Butyrate | 9.48a | 6.76b | 8.08ab | 7.09b | 0.61 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | > 0.05 |

| Isovalerate | 1.11a | 0.71b | 0.67b | 0.44c | 0.14 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.05 |

| Valerate | 1.55a | 0.82b | 0.58c | 0.63c | 0.22 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.05 |

| Location | ||||||||

| 1Plasma | 1.99 | 1.87 | 2.31 | 1.61 | 0.15 | < 0.01 | > 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| 1Jejunum | 7.40b | 7.88b | 11.28a | 7.08b | 0.97 | < 0.01 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| 1Ileum | 9.21a | 7.91b | 9.82a | 8.45a | 0.42 | < 0.01 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Caecum | 24.91 | 22.36 | 23.71 | 22.12 | 0.65 | < 0.05 | > 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Colon | 24.57a | 19.25b | 17.32b | 22.29ab | 1.61 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Feces | 39.61a | 22.43c | 30.84b | 23.27c | 4.00 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Total SCFA | 107.70a | 81.69b | 95.28a | 84.82b | 5.876 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Bile acids | Diets | P value | ||||||

| CON | ZNO | RB2 | RB4 | SEM | *L | #D | +L*D | |

| THCA | 40.74a | 27.29b | 16.88c | 26.86b | 4.90 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.75 |

| GHDCA | 33.78b | 46.08a | 25.76c | 33.45b | 4.20 | < 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.62 |

| TCA | 1.50b | 1.56b | 1.96a | 1.30b | 0.14 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| GCA | 0.40b | 0.47b | 0.45b | 1.37a | 0.23 | > 0.05 | 0.01 | > 0.05 |

| TCDCA | 21.90a | 8.89c | 8.30c | 15.09b | 3.18 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| TDCA | 5.11a | 3.42b | 4.07ab | 3.90b | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.93 |

| GCDCA | 15.42c | 13.88c | 35.91a | 25.40b | 5.10 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.25 |

| GDCA | 3.57b | 4.91a | 2.95c | 3.26b | 0.43 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.05 |

| GLTCA | 2.11ab | 1.99b | 3.60a | 1.96b | 0.40 | < 0.05 | < 0.01 | 0.18 |

| CA | 3.80b | 2.59c | 4.23a | 1.63d | 0.59 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| CDCA | 121.16b | 72.28c | 147.09a | 74.32c | 18.34 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| DCA | 0.10b | 0.14b | 0.31a | 0.12b | 0.05 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | 0.20 |

| LCA | 134.25a | 108.90b | 118.20b | 107.66b | 6.13 | < 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.42 |

| Location | ||||||||

| 1Jejunum | 138.20b | 135.03b | 210.83a | 128.68c | 19.32 | < 0.01 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Ileum | 95.20a | 40.21c | 29.11d | 50.09b | 14.40 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.05 |

| Caecum | 23.95a | 17.37b | 15.65b | 12.84c | 2.35 | < 0.01 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Colon | 59.88a | 28.45c | 46.40b | 21.10d | 8.77 | <0.01 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Faeces | 66.59c | 71.33b | 67.72c | 83.62a | 3.90 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.05 |

| Total unconjugated | 259.30a | 183.91b | 269.83a | 183.74b | 23.41 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Total conjugated | 124.52a | 108.48b | 99.88b | 112.60b | 5.12 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Total bile acids | 383.82a | 292.39b | 369.71a | 296.33b | 23.98 | < 0.001 | < 0.05 | < 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).