1. Introduction

Research on the gut microbiota has attained attention in recent years largely because of its relationship to gastrointestinal (GI) and extra gastrointestinal (extra-GI) diseases. The gut microbiota refers to the group of microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, archaea, protozoa, and fungi that coexist symbiotically in the host GI tract (Hou et al. 2022; de Vos et al. 2022; Pilla and Suchodolski 2019). They perform various functions in several important processes including energy metabolism, immunomodulation, digestion, fermentation, and protection against pathogens. Non-digestible compounds in food, such as plant-derived polysaccharides, and nutrients that escape from small intestines digestion can also be degraded by these microorganisms. Moreover, the gut microbiota also plays an important role in the homeostasis of the host by modulating the function of several vital systems, such as the cardiovascular, renal, and immune systems[

1,

2,

3].

From an immunological perspective, specific microorganisms can be recognized as pathogenic by the host immune system. However, the majority of gut microorganisms are non-pathogenic and, instead, co-exist with enterocytes in an interdependent relationship[

4]. A balanced and well-functioning microbiota can be both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory to maintain a balance that avoids over-inflammation while responding quickly to infections[

5]. The types of microorganisms that make up the microbiota vary from site to site and species to species[

6,

7].

In animals, the health status of the gut microbiome is connected to a variety of diseases. For example, dysbiosis, or an imbalance in the microbiome, has been associated with a number of inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and leaky gut syndrome in dogs. Previous research reported that dogs living in breeding conditions are more vulnerable than companions to chronic stress, which is linked to more gut disorder occurrences and increased dysbiosis. Intestinal dysbiosis is frequently associated with a decrease in microbial diversity in dogs with IBD[

8]. Diarrhea, colitis, and constipation are other diseases that affect millions of humans and dogs around the world and changes in the gut microbiota play a significant role in the onset and progression of these disorders[

1,

2]. Similarly, an imbalanced gut microbiota of dogs has also been linked to metabolic complications in the gut and many GI disorders, in which a classical treatment would involve the use of antimicrobial drugs and antibiotics[

2,

3]. However, it should be noted that antibiotic treatment increases the risk of developing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and poses threats on gut microbiota such as reduction of species diversity, alteration of metabolic activity, and consequent antibiotic-resistant organisms, which in turn can lead to antibiotic-associated diarrhea and recurrent infections[

3,

9]. Thus, there is a growing need for treatments that do not rely on antimicrobials, such as the use of natural agents, which do not pose a risk of AMR[

10,

11].

Nutraceuticals are a wide range of natural substances with health benefits and fewer side effects. They provide health benefits to the body and aid in the prevention of diseases[

12]. A large variety of nutraceutical groups have antioxidant activity, making them useful agents in a variety of disorders[

13] which include oxidative stress, a major component in several gastrointestinal disorders[

14]. Among these nutraceuticals are bromelain (B),

Lentinula edodes (LE), and quercetin (Q).

Bromelain (B), is a complex mixture of enzymes and bioactive compounds naturally occurring in various parts of pineapple, including its stems, fruit, and roots [

15]. Among its constituents, proteinases and proteases are the key enzymes responsible for protein breakdown within the body. Notably, bromelain can easily be absorbed in the body without interfering with protein digestion in the gastrointestinal tract. In addition to its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, bromelain has demonstrated efficacy in managing various gastrointestinal ailments such as dyspepsia [

16].

Quercetin (Q), is a significant polyphenolic flavonoid, present in a wide range of fruits and vegetables, including apples, onions, grapes, berries, and capers [

17]. Human studies has indicated that quercetin, in addition to being a potent antioxidant, has valuable anti-inflammatory qualities [

13]. Additionally, it has been shown to improve intestinal dysbiosis (HFD) in mice fed a high-fat diet by attenuating lipoprotein-dependent activation of the lipoprotein-dependent pathway (TLR-4) [

18].

Lastly, mushrooms contain a wide variety of bioactive substances including polysaccharides, dietary fibers, minerals, and proteins[

19,

20].

Lentinula edodes (LE), in particular, is a mushroom used in supplement preparations and has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-diabetic properties in both humans and animal models[

21,

22,

23]. In addition to their biological effects, there has also been work focusing on regulating gut microbiota through the use of mushrooms’ polysaccharides[

24,

25].

Here, we sought to evaluate the activity of a formulated antioxidant-rich supplement composed of the natural ingredients B, Q, and LE on the gut microbiota of healthy adult dogs and determine if this new formulation impacts microbiota stability in the gut when compared to a placebo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and study design

In a double blinded randomized controlled trial, a total of 30 adult female American Staffordshire Terrier dogs, weighing 17 ± 1.5 kg and 5 ± 1 years old were selected from Ente Nazionale Cinofilia Italiana (ENCI/

www.enci.it), a registered dog breeder in Italy. Animals participating in this study were the same as those reported[

14]. The study was performed in strict compliance with the guidelines of the Ministry of Health for the use of animals in research. Before signing a formal informed consent, the overall objectives of the study were disclosed to the breeder. Both study protocols and the use of supplements were approved by the Ethical Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Turin on 19 July 2022 under protocol number 2741.

The health status of all animals was evaluated by a veterinarian through a general physical examination followed by a copromicroscopic analysis of their feces. All animals were found to be healthy with no underlying conditions that required treatment. The 30 dogs were randomly allocated to two groups: a control (CTR, n = 15) and treatment (TRT, n = 15) group. Dogs were housed in cages (3 dogs per cage), with an area of 6 ±2 square meters. To ensure animal welfare following the principles of animal welfare legislation (Regolamento regionale 11 novembre 1993, Italy), dogs were provided with an open space of the same size as their box thus avoiding public stress due to collective manipulation. Animals in both groups received a commercially available diet (“Royal Canin, Medium Adult Dry Dog Food”) (Supplemental

Table 1) from 7 days prior to the commencement of the study to allow the GI system to adapt to the new diet. The daily calories intake of each group was calculated per FEDIAF Nutritional Guidelines (FEDIAF, 2021) using the following equation such that “ME” is metabolizable energy and “BW” is body weight:

In both the CTR and TRT groups, each participant was given either a placebo of maltodextrin powder, or a formulated feed containing a mixture of nutraceutical ingredients in their food once a day for 28 days. Dosage: 1 g / 10 Kg of BW (Atuahene et al. 2023).

2.2. Formulated Feed Composition

The formulated feed consisted of a mixture of nutraceuticals including 1.35% each of bromelain (B) and quercetin (Q), and 1.00% Lentinula edodes mushrooms (LE). Exact compositions of the formulated feed were previously reported[

14] and can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

2.3. Safety and Nutritional Parameters

An experienced veterinarian measured the body weights (BW) at T0 (baseline) and then at T28 (28 days after the beginning of the feed supplement administration) for all animals. A Body Condition Score (BCS), using a scale of 1 to 9, was determined through a physical (visual) examination and palpation at T0 and T28 by the same experienced veterinarian. Additionally, the fecal pH was determined using a calibrated pH instrument at T0 and T28 (HI 9125 pH/ORP meter; Hanna Instruments, Bedfordshire, UK). The data for these parameters have been reported previously[

14].

2.4. Fecal Sample Collection

Fresh fecal samples were collected in a sterile plastic bag using a sterile spatula and temporarily held at 4 °C freezer until moving into a -80°C freezer until sequencing, as previously described[

14]. To minimize bias, a non-biased blinded procedure was employed for the identification of all samples. Microbiome analysis was subsequently conducted on fecal samples collected at T0, T28, and T35.

2.5. Fecal DNA extraction, PCR Amplification and Amplicon Target Sequencing

Microbial DNA was extracted from a total of 150 mg of fecal samples using a DNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research; Irvine, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocols, including a bead beating step. Total DNA was quantified using a QubitTM 3 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA), and subjected to a PCR step where the V3-V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using indexed primers[

26] and DNA was purified using a Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina; San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The generated amplicons were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq (San Diego, CA, USA) using a 2 x 250 bp paired-end v2 sequencing kit.

2.6. Computation and Sequence Analysis

The resulting raw sequences (FASTQ) were processed using the same standard operation procedure as previously described[

27]. Briefly, sequences were filtered and processed using DADA2 in the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME 2) program[

28]. Chimeric sequences were identified and subsequently removed from the dataset and the remaining sequences were then grouped into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) and assigned taxonomy using the Greengenes database (version 13.8). The ASV abundance tables, the taxonomy tables and associated phylogenetic trees were imported into R v4.3.2 [

29] and used to build a phyloseq object[

30].

2.7. Taxonomic Statistical Analysis

The phyloseq object, containing the ASV abundances, was used to calculate alpha- and beta-diversity along with differential abundance analyses of taxa. For alpha-diversity, samples were rarefied down to the read depth of the sample with the lowest read depth and Shannon’s diversity, the observed species and the inverse Simpson metrics calculated. Beta-diversity was conducted using Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix in the vegan package[

31]. The Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix was further used in a PERMANOVA analysis with the adonis function of the vegan package[

32] with 1,000 permutations. For diversity metrics, the threshold for significance was set at p < 0.05.

To examine if individual ASVs changed over time, differential abundance analysis was conducted using the ancombc2 function in the ANCOM-BC package[

33] in R. P-values were adjusted using the false discovery rate procedure and ASVs with a corrected p-values < 0.1 were considered significant.

3. Results

A total of 5,346,677 reads were generated across the 90 samples. After filtering and sequence clean-up an average read count per sample of 60,075 ± 4122 were retained, which clustered into 3,038 distinct amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) that classified into 15 phyla, 103 families and 153 genera. To ensure comprehensive alpha and beta diversity analyses, samples were rarefied based on the sample with the lowest read count, which was 51,499 reads. The rarefaction curves, depicted in Supplementary

Figure 1, indicated that this read depth was sufficient to capture most of the diversity within the samples.

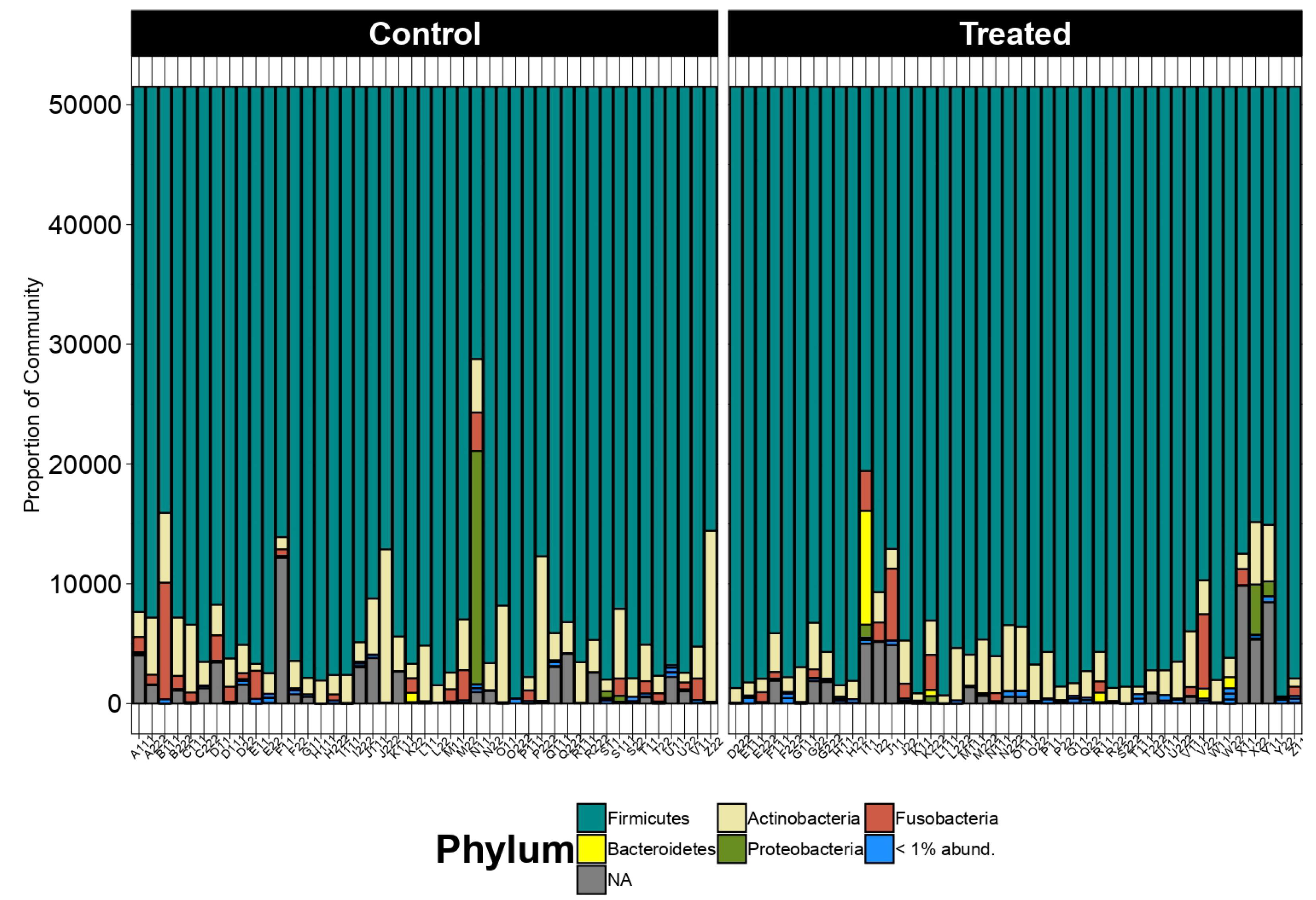

At the phylum level, the taxonomic distribution displayed remarkable consistency across all samples. The Firmicutes emerged as the predominant phylum, followed by the Actinobacteriota and Fusobacteriota, as illustrated in

Figure 1. This uniformity underscores the substantive presence and importance of these phyla within the studied microbiome.

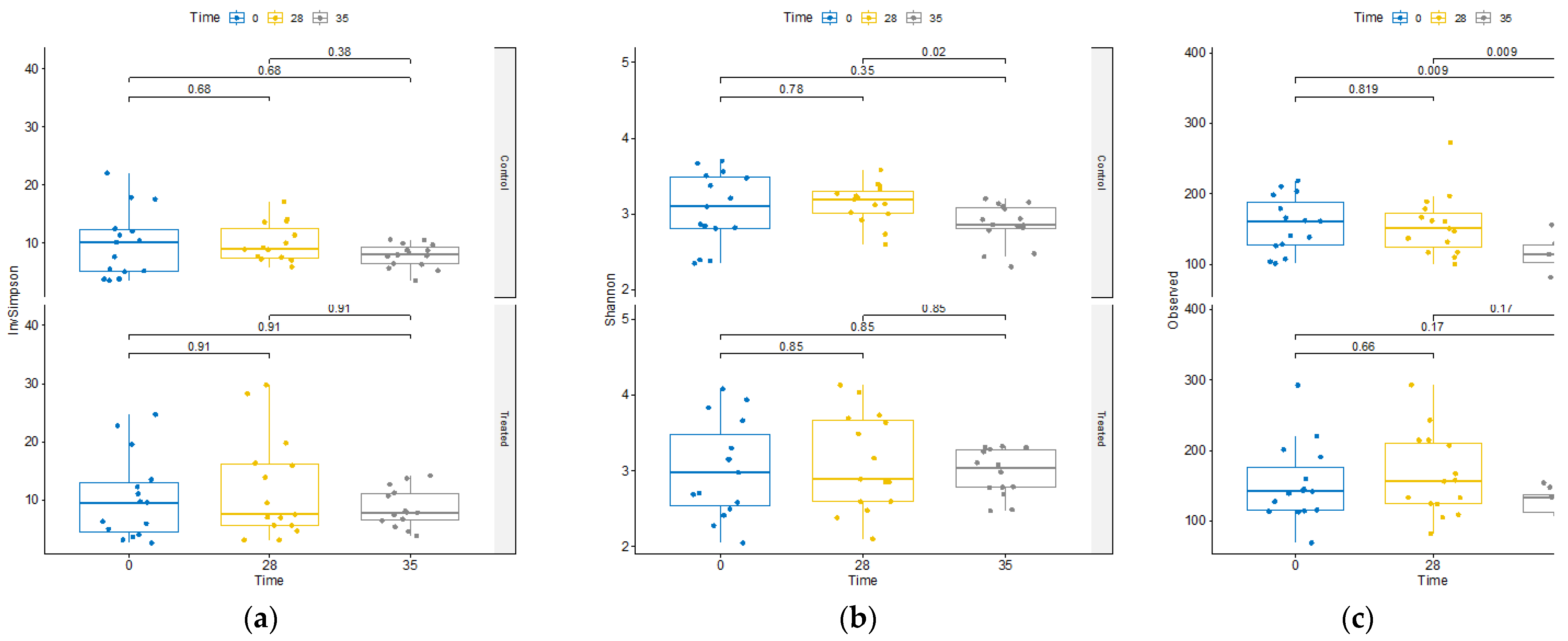

The impact of the supplement on microbiome diversity was rigorously assessed. Comparative analysis across treatments at T0, T28, and T35 revealed no discernible differences in alpha diversity metrics between the treatment groups (Supplementary

Figure 2). Moreover, as shown in

Figure 2, within the TRT group, assessment of diversity alterations over time exhibited no significant changes in alpha diversity.

Contrarily, within the CTR group, we observed a decline in alpha diversity at day 35 (

Figure 2). This decline was evident in both the total observed ASVs and the Shannon’s index, a widely used metric that accounts for species richness and evenness in data evaluation, highlighting a substantial reduction in diversity within this group at that specific time point.

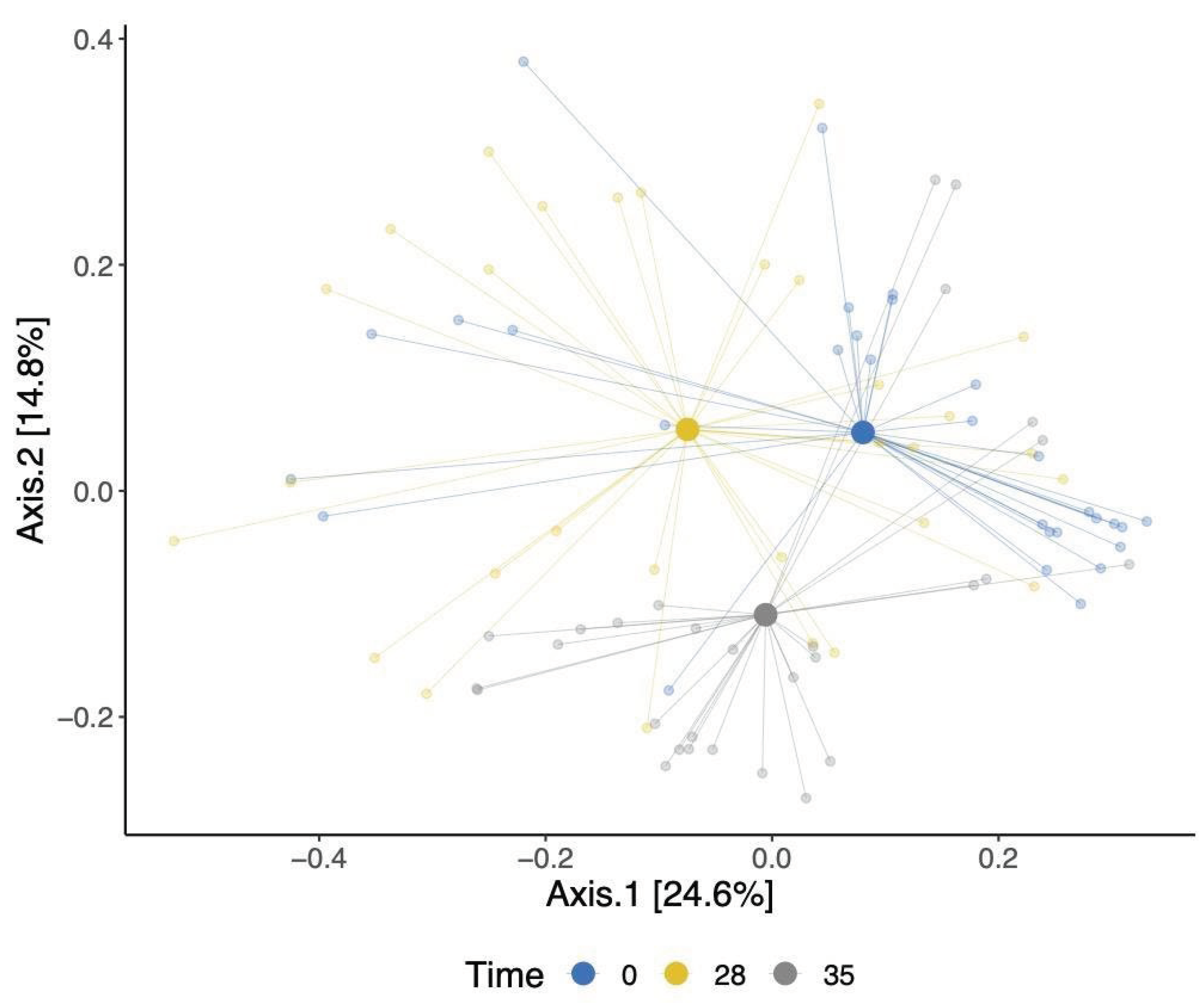

Our analysis of beta diversity showed a shift in the overall gut bacterial communities over time point (

Figure 3). This was confirmed using an adonis test, which showed that the observed separation is statistically associated with time point differences. The identified changes were evident in both the TRT and CTR groups, signifying shifts in the bacterial communities within these cohorts. Moreover, a modest statistically significant dissimilarity was noted when comparing the bacterial compositions of dogs between the TRT and CTR groups (p-value = 0.02), as shown in Supplementary

Figure 3.

We then identified ASVs that were determined to be differentially abundant in the TRT group between T0 and T28. Several ASVs were found to be differentially abundant in this group over time (

Table 1) including increased abundance of ASVs belonging to the Bifidobacterium (β = 0.065, SD = 0.014, corrected p-value < 0.001), Lactobacillaceae (unclassified at genus level) (β = 0.104, SD = 0.022, corrected p-value < 0.001) and Peptostreptococcaceae (unclassified at genus level) (β = 0.05, SD = 0.015, corrected p-value = 0.019). There was also a decrease in ASVs belonging to the Fusobacteria (unclassified at species level) (β = -0.070, SD = 0.023, corrected p-value = 0.049), Peptococcus (β = -0.059, SD = 0.010, corrected p-value = 0.007) and Dorea (β = -0.053, SD = 0.015, corrected p-value = 0.019).

Table 1.

Differentially abundant ASVs by time within treated dogs as determined by ANCOM-BC (T0 vs T28).

Table 1.

Differentially abundant ASVs by time within treated dogs as determined by ANCOM-BC (T0 vs T28).

| Taxonomic classification |

Higher Abundance Timepoint |

beta

coefficient |

Standard

deviation |

W statistic |

p-value |

Corrected p-value |

ASV code |

| Fusobacteria_unclassified |

T0 |

-0.047 |

0.016 |

-2.972 |

0.003 |

0.050 |

ASV334 |

| Fusobacteria_unclassified |

T0 |

-0.070 |

0.023 |

-3.025 |

0.002 |

0.049 |

ASV029 |

|

Bifidobacterium sp |

T28 |

0.065 |

0.014 |

4.698 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

ASV073 |

| Bifidobacterium animalis |

T28 |

0.089 |

0.023 |

3.925 |

0.000 |

0.005 |

ASV117 |

| Bifidobacterium breve |

T28 |

0.070 |

0.023 |

2.993 |

0.003 |

0.050 |

ASV007 |

| Lactobacillaceae_unclassified |

T28 |

0.104 |

0.022 |

4.697 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

ASV256 |

| Lactobacillaceae_unclassified |

T28 |

0.063 |

0.017 |

3.827 |

0.000 |

0.006 |

ASV585 |

| Lactobacillaceae_unclassified |

T28 |

0.111 |

0.025 |

4.489 |

0.000 |

0.001 |

ASV098 |

| Lactobacillaceae hamsteri |

T28 |

0.098 |

0.027 |

3.568 |

0.000 |

0.012 |

ASV440 |

| Anaerorhabdus furcosa |

T28 |

0.055 |

0.016 |

3.318 |

0.001 |

0.022 |

ASV269 |

| Bacillaceae_unclassified |

T28 |

0.047 |

0.016 |

2.847 |

0.004 |

0.070 |

ASV706 |

| Lactobacillus hamsteri |

T28 |

0.064 |

0.023 |

2.715 |

0.007 |

0.099 |

ASV408 |

|

Peptococcus sp |

T0 |

-0.059 |

0.016 |

-3.590 |

0.000 |

0.012 |

ASV519 |

| Peptostreptococcaceae_unclassified |

T28 |

0.050 |

0.015 |

3.387 |

0.001 |

0.019 |

ASV003 |

| Peptostreptococcaceae_unclassified |

T28 |

0.046 |

0.015 |

3.140 |

0.002 |

0.037 |

ASV006 |

| Dorea longicatena |

T0 |

-0.053 |

0.015 |

-3.418 |

0.001 |

0.019 |

ASV262 |

We also observed ASVs that were differentially abundant in the placebo group between T0 and T28 (Supplemental

Table S2). These included increased abundances of ASVs belonging to the Bifidobacterium (β = 0.019, SD = 0.007, corrected p-value = 0.081) and

Lactobacillaceae (unclassified at genus level) (β = 0.084, SD = 0.027, corrected p-value = 0.058). There were also decreases in the abundances of ASVs belonging to the Fusobacteria (unclassified at species level) β = -0.058, SD = 0.021, corrected p-value = 0.081). Although there were changes in both the TRT and CTR groups, differences in the CTR group were less pronounced than changes in the TRT group as observed by beta coefficients.

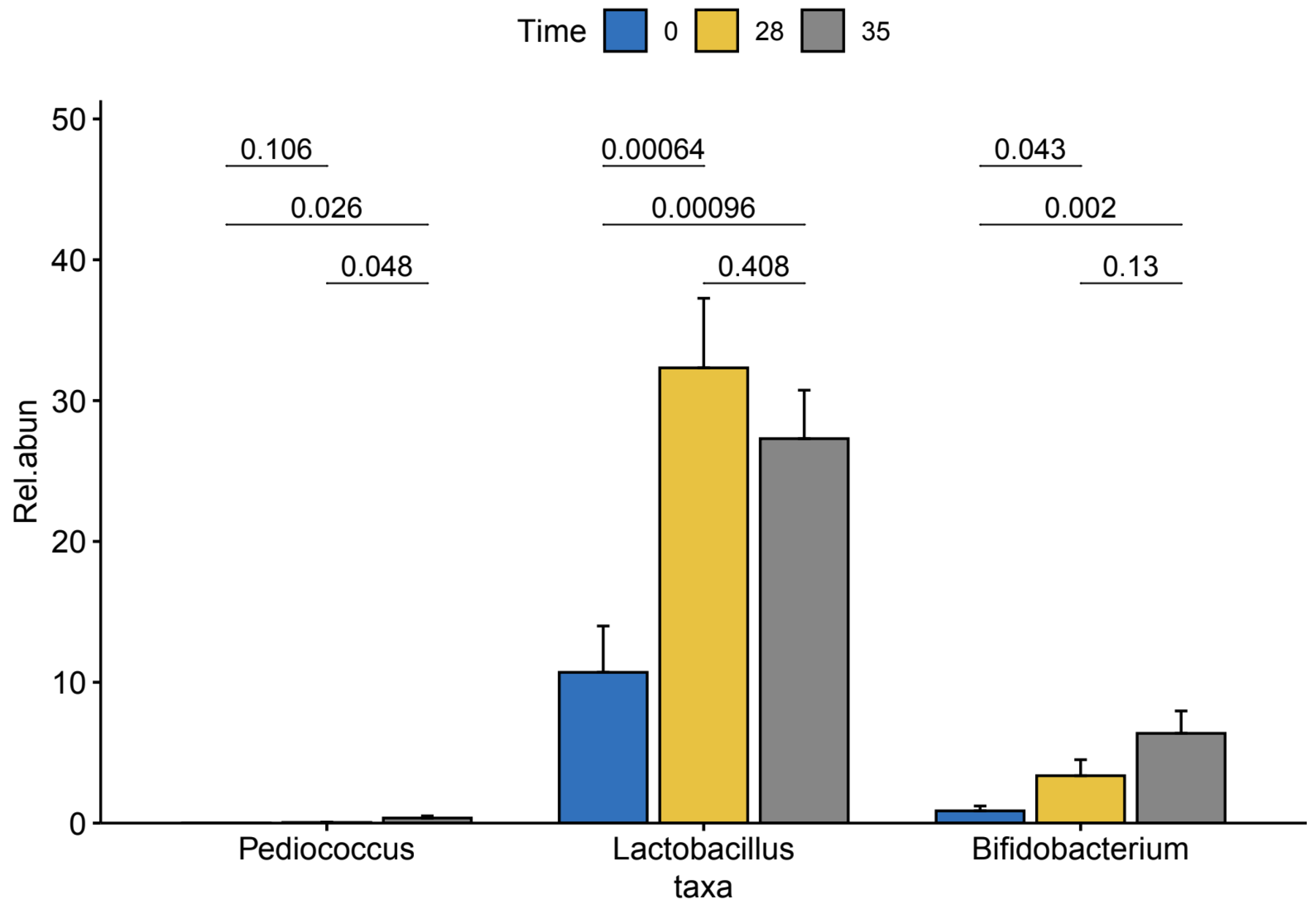

We then conducted a pairwise analysis of differences in relative abundance of the three enriched genera within our TRT group between time points using pairwise t-test (

Figure 4). We found a significant increase in Lactobacillus (p-value = 0.00064) and Bifidobacterium (p-value = 0.043) from T0 to T28. We also observed significant increases in the abundances of the Lactobacillus (p-value = 0.00096) and Bifidobacterium (p-value = 0.002) from T0 to T35.

4. Discussion

This study provides evidence that the use of a novel supplement that includes a blend of nutraceuticals in the form of B, Q and LE results in a shift in the gut microbiome of healthy dogs after four weeks of treatment. Although we did not observe changes in alpha diversity after the supplementation in the TRT group as measured by inverse Simpson’s Index, Shannon’s Diversity Index or observed species, we found shifts in individual taxa over time. It has previously been shown that supplementation of this blend of nutraceuticals improves stress and inflammatory outcomes and also increases the presence of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in this cohort of dogs[

14]. We postulate that the shift in the gut microbiome has a hand in modulating improvement in these biomarkers. While there were decreases in the alpha diversity over time, specifically in observed ASVs and Shannon Diversity in the control group these differences were likely due to the natural fluctuations of the gut microbiome.

ASVs belonging to the family

Bifidobacteriaceae and

Lactobacillaceae were increased after supplementation administration in the TRT group. Members of the

Bifidobacteria and

Lactobacillaceae include commensal bacteria that produces several SCFAs including propionate, acetate and formate as a product of carbohydrate fermentation[

34]. While

Bifidobacteria tends to have a lower abundance in dogs, when compared to humans, it provides metabolites that promote anti-inflammation in dogs, such propionate, which decreases the production of cytokines that promote inflammation including IL-6 and IL-8[

35]. We also observed decreases in ASVs belonging to

Peptococcus and

Dorea longicatena, both of which are SCFA-producers and known to be residents in the guts of healthy canines under the state of eubiosis[

36] (Suchodolski et a. 2013). We postulate that this reduction in these groups of bacteria may be a result of the increase of the other SCFA-producers including

Lactobacillaceae. Panasevich et al. showed, in a cohort of healthy adult Beagles, that after administration of nonviable

Lactobacillus acidophilus plus prebiotics the dogs had a significant increase in total SCFA, significant increase in abundance of bacteria belonging to

Lactobacillaceae and a decrease in

Dorea when compared to dogs on a control diet [

37].

Additionally, the ASVs belonging to

Dorea longicatena may have a role in levels of cortisol, the hormone that responds to stress, in the dogs. Associations between cortisol and gut microbial abundance in dogs have been already explored[

2,

38]. Briefly, in a randomized study of 20 5-month-old beagles examining the safeness of softening dog food with water, dogs that consumed softened dog food had higher levels of cortisol and higher levels of pathogenic bacteria including

Enterococcus[

38]. In our prior study, we found that cortisol decreased in the dogs 28 days after supplementation administration[

14]. Moreover, work in our group has previously shown that a 35-day

Saccharomyces boulardii supplementation resulted in a decrease in cortisol levels and a decrease in ASVs belonging to the genus

Dorea [

2] as in the current study.

We also observed a decrease in ASVs belonging to the

Bacteroides in the TRT group.

Bacteroides are among the gut microbes that can metabolize tryptophan into various metabolites including indole and the indole-related skatole[

39,

40]. Indole is involved in intra-bacterial communication and has been linked to the reduction in motility[

41], cytotoxicity[

42] and invasiveness [

43] of pathogenic bacteria. Despite these benefits, excess indole can be detrimental to the host. In studies involving rodent models, germ-free rodents that were colonized with indole-producing

E. coli had significantly higher emotional responses to mildly stressful events in study involving mice[

44] and increased anxiety-like behavior in rats[

45] when compared to rodents that were colonized with non-indole-producing

E. coli. This provides a possible link between the decreased

Bacteroides and our previous observation of decreased cortisol and the decreased indole in this cohort of dogs[

14].

Our work here shows that the dogs in the TRT group had an increase in abundance of ASVs belonging to the

Lactobacillaceae family. Members of

Lactobacillaceae family have been inversely associated with calprotectin, a protein that is released by neutrophils which are white blood cells. The presence of calprotectin in feces is indicative of gastrointestinal inflammation[

46]. In our prior study, calprotectin was significantly reduced over the course of supplementation administration in dogs[

14]. Similarly, a double-blind study of 22 dogs, given either a Lactic-acid bacteria (LAB) supplement containing

Limosilactobacillus fermentum,

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, and

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum or placebo over 7 days, showed that all dogs given the LAB supplement had negligible levels of calprotectin while five dogs given placebo had increased calprotectin after supplementation[

47].

Our study used a double blinded randomized controlled design, an optimal study design which guaranteed high quality of the evidence. However, this study is limited by the use of 16S rRNA sequencing which is able to examine the structural profiles of the gut microbial communities and not the functional aspects of the gut microbiome which would be attainable if we conducted whole-genome metagenomics, metatranscriptomics or meta-proteomics. However, we note that we have previously reported on fecal measures in our prior study[

14], including the sum of all SCFA that are bacterial-derived. This information provides valuable insights into the functional roles of certain members of the gut microbiome. An additional limitation of this study is that we observed changes in features of the microbiome over time in the placebo group, namely decreases in observed species after administration of the placebo supplement in addition to changes in individual ASV abundances over the course of placebo supplementation. Despite this, the differences observed in ASVs abundances were more pronounced in the TRT group providing some evidence that the supplement might be contributing to the shift in the microbiome. We also found that there is an overall difference in the microbial communities between the two groups (Supplemental

Figure 3) suggesting a nuanced but noteworthy divergence between the microbiota of these distinct experimental cohorts.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that a supplement containing Q, B, and LE alters the gut microbiota of adult dogs after a 4-week treatment. Although promoting the growth of various microbes, the supplement does not disturb the overall gut microbiome diversity. This suggests its potential as a microbial modulator without compromising the overall balance, making it a candidate for investigating its role alongside or in support of antibiotics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Rarefaction curves for all samples for treated and control groups; Figure S2: Alpha diversity analysis of treated vs control groups at T0, T28 and T35; Figure S3: A principal coordinate analysis using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix for β diversity colored by treated and control groups; Table S1: Composition of nutraceutical and placebo; Table S2: Differentially abundant ASVs by time within control group as determined by ANCOM-BC

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M. and D.A.; methodology, D.A., G.M., G.S. and B.S.; software, B.S., I.Z.C. and D.A.; validation, G.M., E.M., B.S. and G.S.; formal analysis, I.Z.C., B.S. and D.A.; investigation, D.A., G.M. and B.S.; resources, G.M. and B.S.; data curation, D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.; writing—review and editing, E.M., G.S., I.Z.C., D.A., B.S., F.B., and G.M.; visualization, D.A., I.Z.C. and G.S.; supervision, G.M. and G.S.; project administration, E.M. and G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Dept. of Veterinary Sciences, University of Turin (Italy). The APC was funded by the Dept. of Veterinary Sciences, University of Turin (Italy). I.Z.C. was supported by the University of Wisconsin-Madison (USA) Department of Bacteriology Roland and Nina Girolami Predoctoral Fellowship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Regulations for the care and use of animals set forth by the Italian Ministry of Health were followed during this study’s execution (D.L. n. 26, 2014), and Regulation (EC) N. 767/2009 was used to regulate the use of supplements. This study was approved by the Ethical Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Turin (19 July 2022; protocol n. 2741).

Informed Consent Statement

A written informed consent form was signed by the dog breeder after being apprised of this study’s procedures.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request to the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Giulio, P. Intestinal Dysbiosis: Definition, Clinical Implications, and Proposed Treatment Protocol (Perrotta Protocol for Clinical Management of Intestinal Dysbiosis, PID) for the Management and Resolution of Persistent or Chronic Dysbiosis. Arch. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 7, 056–063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meineri, G.; Martello, E.; Atuahene, D.; Miretti, S.; Stefanon, B.; Sandri, M.; Biasato, I.; Corvaglia, M.R.; Ferrocino, I.; Cocolin, L.S. Effects of Saccharomyces Boulardii Supplementation on Nutritional Status, Fecal Parameters, Microbiota, and Mycobiota in Breeding Adult Dogs. Vet. Sci. China 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchodolski, J.S. Analysis of the Gut Microbiome in Dogs and Cats. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2022, 50 Suppl 1, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Nageshwar Reddy, D. Role of the Normal Gut Microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilla, R.; Suchodolski, J.S. The Role of the Canine Gut Microbiome and Metabolome in Health and Gastrointestinal Disease. Front Vet Sci 2019, 6, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, G.; Rybakova, D.; Fischer, D.; Cernava, T.; Vergès, M.-C.C.; Charles, T.; Chen, X.; Cocolin, L.; Eversole, K.; Corral, G.H.; et al. Correction to: Microbiome Definition Re-Visited: Old Concepts and New Challenges. Microbiome 2020, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrigues, Q.; Apper, E.; Chastant, S.; Mila, H. Gut Microbiota Development in the Growing Dog: A Dynamic Process Influenced by Maternal, Environmental and Host Factors. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 964649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhimi, S.; Kriaa, A.; Mariaule, V.; Saidi, A.; Drut, A.; Jablaoui, A.; Akermi, N.; Maguin, E.; Hernandez, J.; Rhimi, M. The Nexus of Diet, Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Dogs. Metabolites 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.; Guarner, F.; Bustos Fernandez, L.; Maruy, A.; Sdepanian, V.L.; Cohen, H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 572912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, J.F.; Hanna, W.J.B.; Reid-Smith, R.; Drost, K. Antimicrobial Drug Use and Resistance in Dogs. Can. Vet. J. 2002, 43, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caneschi, A.; Bardhi, A.; Barbarossa, A.; Zaghini, A. The Use of Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance in Veterinary Medicine, a Complex Phenomenon: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, K.A.; Mohamad Annuar, M.S.; Ahmad, N. Chapter 9 - Nano-Delivery Systems for Nutraceutical Application. In Nanotechnology Applications in Food; Oprea, A.E., Grumezescu, A.M., Eds.; Academic Press, 2017; pp. 179–202 ISBN 9780128119426.

- Kelsey, N.A.; Wilkins, H.M.; Linseman, D.A. Nutraceutical Antioxidants as Novel Neuroprotective Agents. Molecules 2010, 15, 7792–7814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atuahene, D.; Costale, A.; Martello, E.; Mannelli, A.; Radice, E.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Chiofalo, B.; Stefanon, B.; Meineri, G. A Supplement with Bromelain, Lentinula Edodes, and Quercetin: Antioxidant Capacity and Effects on Morphofunctional and Fecal Parameters (Calprotectin, Cortisol, and Intestinal Fermentation Products) in Kennel Dogs. Veterinary Sciences 2023, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavan, R.; Jain, S.; Shraddha; Kumar, A. Properties and Therapeutic Application of Bromelain: A Review. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2012, 2012, 976203. [CrossRef]

- Kostiuchenko, O.; Kravchenko, N.; Markus, J.; Burleigh, S.; Fedkiv, O.; Cao, L.; Letasiova, S.; Skibo, G.; Fåk Hållenius, F.; Prykhodko, O. Effects of Proteases from Pineapple and Papaya on Protein Digestive Capacity and Gut Microbiota in Healthy C57BL/6 Mice and Dose-Manner Response on Mucosal Permeability in Human Reconstructed Intestinal 3D Tissue Model. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand David, A.V.; Arulmoli, R.; Parasuraman, S. Overviews of Biological Importance of Quercetin: A Bioactive Flavonoid. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2016, 10, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porras, D.; Nistal, E.; Martínez-Flórez, S.; Pisonero-Vaquero, S.; Olcoz, J.L.; Jover, R.; González-Gallego, J.; García-Mediavilla, M.V.; Sánchez-Campos, S. Protective Effect of Quercetin on High-Fat Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice Is Mediated by Modulating Intestinal Microbiota Imbalance and Related Gut-Liver Axis Activation. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2017, 102, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xie, W.; Sun, H.; Cao, K.; Yang, X. Effect of the Structural Characterization of the Fungal Polysaccharides on Their Immunomodulatory Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 3603–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziaja-Sołtys, M.; Radzki, W.; Nowak, J.; Topolska, J.; Jabłońska-Ryś, E.; Sławińska, A.; Skrzypczak, K.; Kuczumow, A.; Bogucka-Kocka, A. Processed Fruiting Bodies of Lentinus Edodes as a Source of Biologically Active Polysaccharides. NATO Adv. Sci. Inst. Ser. E Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatvani, N. Antibacterial Effect of the Culture Fluid of Lentinus Edodes Mycelium Grown in Submerged Liquid Culture. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2001, 17, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handayani, D.; Chen, J.; Meyer, B.J.; Huang, X.F. Dietary Shiitake Mushroom (Lentinus Edodes) Prevents Fat Deposition and Lowers Triglyceride in Rats Fed a High-Fat Diet. J. Obes. 2011, 2011, 258051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzberger, C.S.G.; Smânia, A.; Pedrosa, R.C.; Ferreira, S.R.S. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Shiitake (Lentinula Edodes) Extracts Obtained by Organic Solvents and Supercritical Fluids. J. Food Eng. 2007, 80, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Liang, Q.; Fenix, K.; Tamang, B.; Hauben, E.; Ma, L.; Zhang, W. Combining the Anticancer and Immunomodulatory Effects of Astragalus and Shiitake as an Integrated Therapeutic Approach. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayachandran, M.; Xiao, J.; Xu, B. A Critical Review on Health Promoting Benefits of Edible Mushrooms through Gut Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of General 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene PCR Primers for Classical and Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Diversity Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga-Chaves, I.; Eggers, S.; Kates, A.E.; Safdar, N.; Suen, G.; Malecki, K.M.C. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status Is Associated with Low Diversity Gut Microbiomes and Multi-Drug Resistant Microorganism Colonization. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team, R.; Others R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2013.

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS One 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, J.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; O’Hara, B.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Oksanen, M.J.; Suggests, M. The Vegan Package. Community ecology package 2007, 10, 719. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, P. VEGAN, a Package of R Functions for Community Ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 2003, 14, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Peddada, S.D. Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunvold, G.D.; Hussein, H.S.; Fahey, G.C., Jr; Merchen, N.R.; Reinhart, G.A. In Vitro Fermentation of Cellulose, Beet Pulp, Citrus Pulp, and Citrus Pectin Using Fecal Inoculum from Cats, Dogs, Horses, Humans, and Pigs and Ruminal Fluid from Cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 3639–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinolo, M.A.R.; Rodrigues, H.G.; Hatanaka, E.; Sato, F.T.; Sampaio, S.C.; Curi, R. Suppressive Effect of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Production of Proinflammatory Mediators by Neutrophils. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchodolski, J.S. Companion Animals Symposium: Microbes and Gastrointestinal Health of Dogs and Cats. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panasevich, M.R.; Daristotle, L.; Quesnell, R.; Reinhart, G.A.; Frantz, N.Z. Altered Fecal Microbiota, IgA, and Fermentative End-Products in Adult Dogs Fed Prebiotics and a Nonviable Lactobacillus Acidophilus. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, K.; Jian, S.; Xin, Z.; Wen, C.; Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Deng, B.; Deng, J. Effects of Softening Dry Food with Water on Stress Response, Intestinal Microbiome, and Metabolic Profile in Beagle Dogs. Metabolites 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roager, H.M.; Licht, T.R.; Poulsen, S.K.; Larsen, T.M.; Bahl, M.I. Microbial Enterotypes, Inferred by the Prevotella-to-Bacteroides Ratio, Remained Stable during a 6-Month Randomized Controlled Diet Intervention with the New Nordic Diet. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennoune, N.; Andriamihaja, M.; Blachier, F. Production of Indole and Indole-Related Compounds by the Intestinal Microbiota and Consequences for the Host: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, T.; Englert, D.; Lee, J.; Hegde, M.; Wood, T.K.; Jayaraman, A. Differential Effects of Epinephrine, Norepinephrine, and Indole on Escherichia Coli O157:H7 Chemotaxis, Colonization, and Gene Expression. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 4597–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledala, N.; Malik, M.; Rezaul, K.; Paveglio, S.; Provatas, A.; Kiel, A.; Caimano, M.; Zhou, Y.; Lindgren, J.; Krasulova, K.; et al. Bacterial Indole as a Multifunctional Regulator of Klebsiella Oxytoca Complex Enterotoxicity. MBio 2022, 13, e0375221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Young, K.D. Indole Production by the Tryptophanase TnaA in Escherichia Coli Is Determined by the Amount of Exogenous Tryptophan. Microbiology 2013, 159, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, H.-D.; Milman, A.; Monnoye, M.; Douard, V.; Philippe, C.; Aubert, A.; Castanon, N.; Vancassel, S.; Guérineau, N.C.; Naudon, L.; et al. The Gut Microbiota Metabolite Indole Increases Emotional Responses and Adrenal Medulla Activity in Chronically Stressed Male Mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 119, 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaglin, M.; Rhimi, M.; Philippe, C.; Pons, N.; Bruneau, A.; Goustard, B.; Daugé, V.; Maguin, E.; Naudon, L.; Rabot, S. Indole, a Signaling Molecule Produced by the Gut Microbiota, Negatively Impacts Emotional Behaviors in Rats. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayling, R.M.; Kok, K. Fecal Calprotectin. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2018, 87, 161–190. [Google Scholar]

- Herstad, K.M.V.; Vinje, H.; Skancke, E.; Næverdal, T.; Corral, F.; Llarena, A.-K.; Heilmann, R.M.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Steiner, J.M.; Nyquist, N.F. Effects of Canine-Obtained Lactic-Acid Bacteria on the Fecal Microbiota and Inflammatory Markers in Dogs Receiving Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Treatment. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).