Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

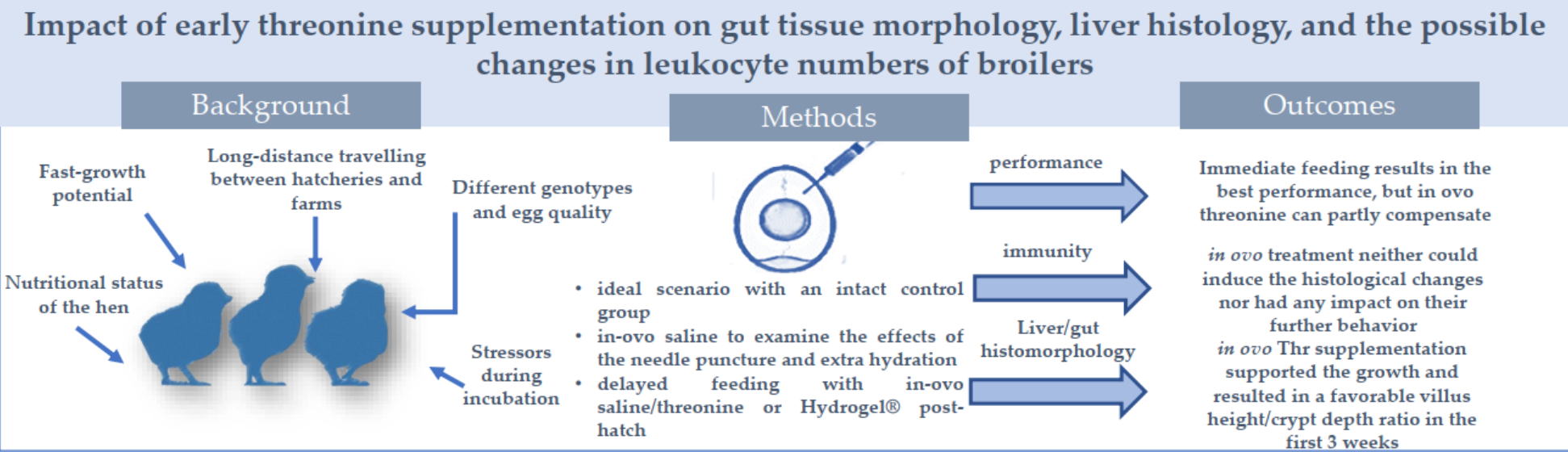

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Hatching protocol and treatment groups

2.2 In ovo intervention

2.3 Identification, feeding management, and housing

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

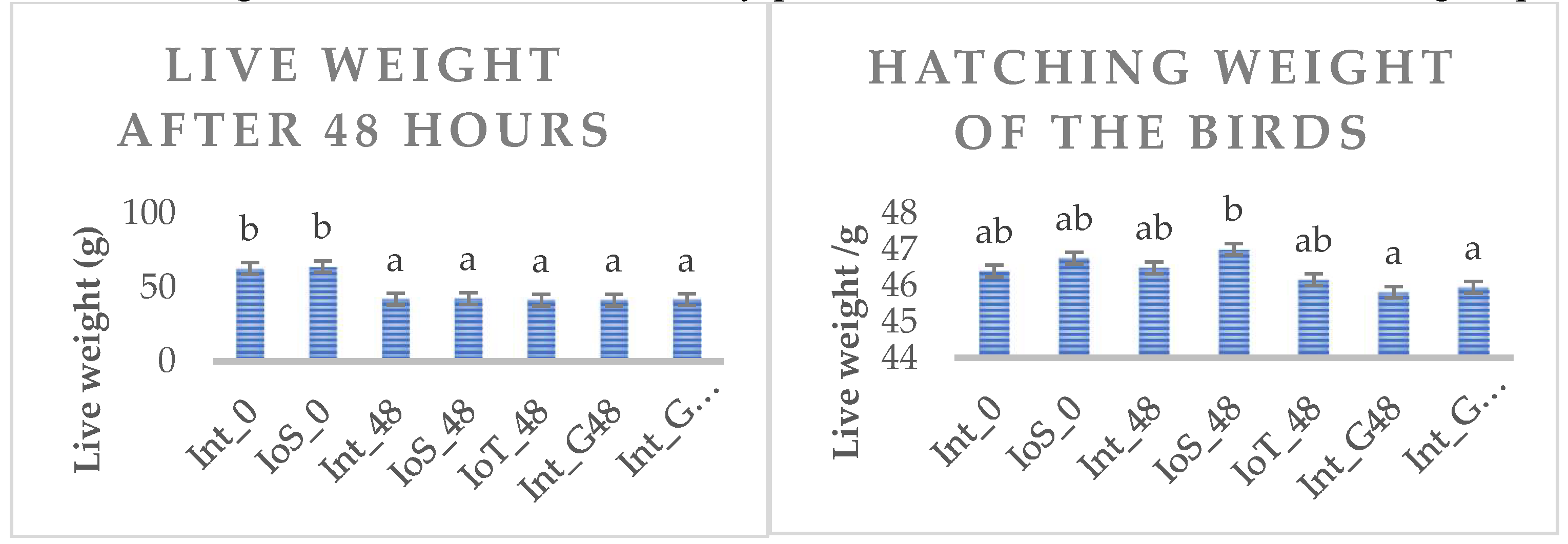

3.1. Growth performance and feed efficiency

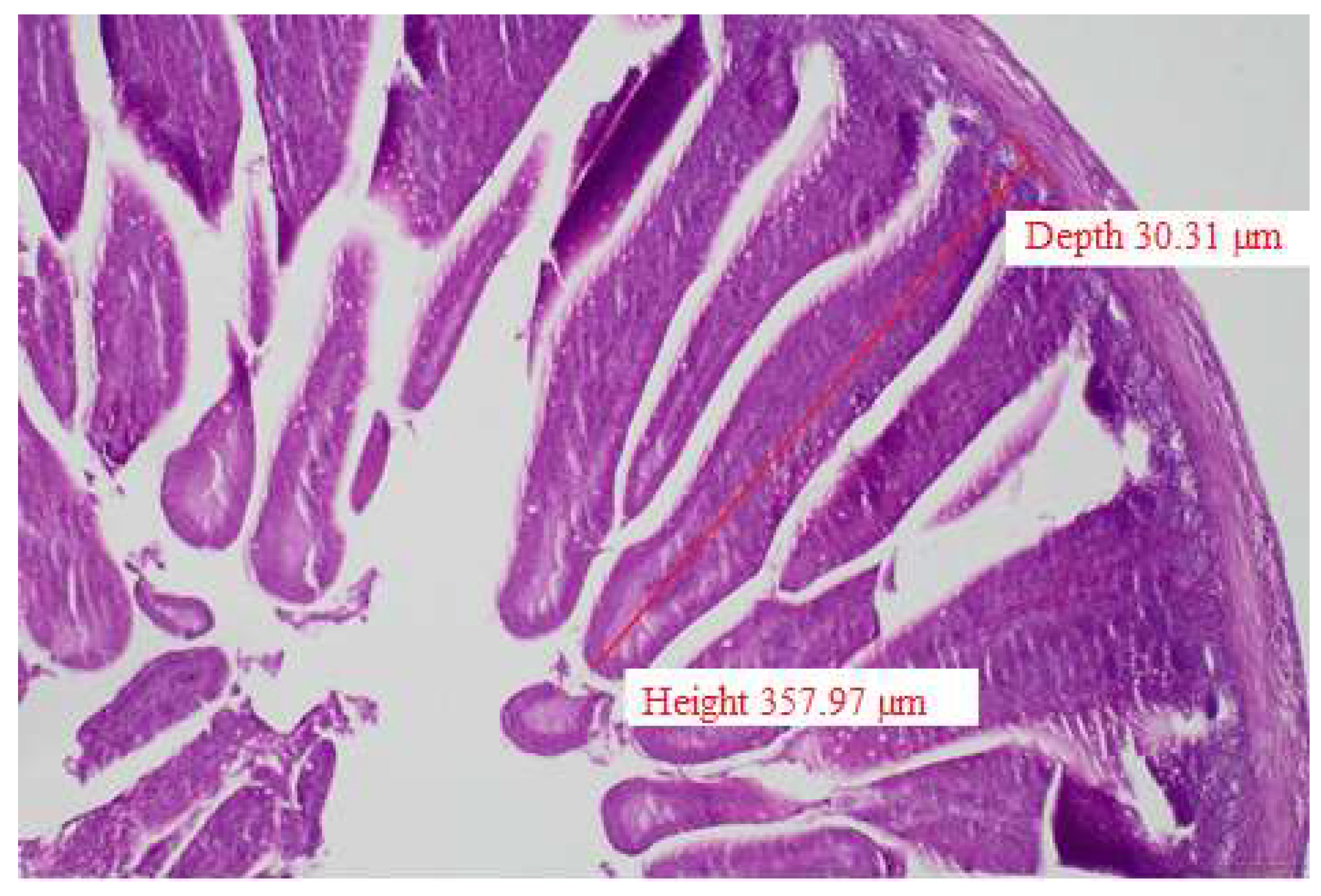

3.2. Intestinal morphometry

3.3. Liver histology and blood cell results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan H, Zengpeng L.V, Gan L, Guo Y: Transcriptomics-related mechanisms of supplementing laying broiler breeder hens with dietary daidzein to improve the immune function and growth performance of offspring J. Agric. Food Chem., 2018, 66, 2049–2060.

- Franco D, Rois D, Arias A, Justo JR, Marti-Quijal FJ, Khubber S, Barba FJ, López-Pedrouso M, Manuel Lorenzo J. Effect of Breed and Diet Type on the Freshness and Quality of the Eggs: A Comparison between Mos (Indigenous Galician Breed) and Isa Brown Hens. Foods. 2020, 9, 342 .

- de Jong, I.C., & van Emous, R.A. (2017): Broiler breeding flocks: Management and animal welfare. In T. Applegate (Ed.), Achieving sustainable production of poultry meat. 2017, 3, 1–19. Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing. https://doi.org/10.19103/AS.2016.0011.26.

- Liu H, Ding P, Tong Y, He X, Yin Y, Zhang H, Song Z, Metabolomic analysis of the egg yolk during the embryonic development of broilers, Poult. Sci., 2021, 100, 101014. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves FM, Santos VL, Contreira CL, Farina G, Kreuz BS, Gentilini FP, Anciuti MA, Rutz F.In-ovo nutrition: Strategy for precision nutrition in poultry industry. Arch Zootec. 2013, 62, 45–55.

- Batal AB, Parsons CM: Effect of fasting versus feeding oasis after hatching on nutrient utilization in chicks. Poult. Sci. 2002, 81, 853–859.

- Jha R, Singh AK, Yadav S, Berrocoso JFD, Mishra B. Early Nutrition Programming (in ovo and Post-hatch Feeding) as a Strategy to Modulate Gut Health of Poultry. Front Vet Sci. 2019, 21, 82. [CrossRef]

- Riva S, Monjo TP, The importance of early nutrition in broiler chickens: Hydrated gels enriched with nutrients, an innovative feeding system. Anim Husb Dairy Vet Sci, 2020, 4, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Jha R, Singh AK, Yadav S, Berrocoso JFD, Mishra B. Early Nutrition Programming (in ovo and Post-hatch Feeding) as a Strategy to Modulate Gut Health of Poultry. Front Vet Sci. 2019, 21, 82. [CrossRef]

- Uni Z, Ferket RP. Methods for early nutrition and their potential. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2004, 60, 101–111.

- Noy, Y. and Sklan, D. Yolk utilization in the newly hatched poult. British Poult Sci. 2001, 39, 446–451.

- Geyra,A., Uni, Z. and Sklan, D. Enterocyte dynamics and mucosal development in the posthatch chick. Poult Sci. 2001, 80, 776–782. [CrossRef]

- Vieira SL, Moran ET, Effects of delayed placement and used litter on broiler yields. J App Poult Res, 1999, 8, 75-81. [CrossRef]

- Sharma J and Burmester B, Resistance of Marek's disease at hatching in chickens vaccinated as embryos with the turkey herpesvirus. Avian Dis, 1982, 134-149.

- Berrocoso JD, Kida R, Singh AK, Kim YS, Jha R. Effect of in ovo injection of raffinose on growth performance and gut health parameters of broiler chicken. Poult Sci. 2017, 96, 1573–1580. [CrossRef]

- Bhanja SK, Mandal AB. Effect of in ovo injection of critical amino acids on pre and post-hatch growth, immunocompetence and development of digestive organs in broiler chickens. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2005, 18, 524–531.

- Ohta Y, Yoshida T, Tsushima N, Kidd MT. The needle bore diameter for in ovo amino acid injection has no effect on hatching performance in broiler breeder eggs. J Poult Sci. 2002, 39, 194–197. [CrossRef]

- Jeurissen SH, Lewis F, van der Klis JD, Mroz Z, Rebel JM, and ter Huurne AA. Parameters and techniques to determine intestinal health of poultry as constituted by immunity, integrity, and functionality. Curr Issues Intest Microbiol. 2002, 3, 1–14.

- Gore AB, Qureshi MA. Enhancement of humoral and cellular immunity by vitamin E after embryonic exposure. Poult Sci. 1997, 76, 984–991. [CrossRef]

- Kidd MT. Nutritional modulation of immune function in broilers. Poult Sci. 2004, 83, 650–657. [CrossRef]

- Kidd MT, Peebles ED, Whitmarsh SK, Yeatman JB, Wideman RF. Growth and immunity of broiler chicks as affected by dietary arginine. Poult Sci. 2001, 80, 1535–1542. [CrossRef]

- Kogut MH, Klasing K. An immunologist’s perspective on nutrition, immunity, and infectious diseases: Introduction and overview. J Appl Poult Res. 2009, 18, 103–110. [CrossRef]

- Sisrat S.D., Chaitrashree A. R., Ramteke B.N. Early post-hatch feeding chicks and practical constrains- A review. Agricultural Reviews. 2018, 39, 226–233.

- Uni Z; Ferket P.R. Enhancement of development of oviparous species by in ovo feeding. US Regular Patent US, 2003, 6, B2.

- Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. 19th Ed., AOAC INTERNATIONAL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, Official Method 2008.01. Revised October 2013.

- Fischer AH, Jacobson KA, Rose J, Zeller R. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. CSH Protoc. 2008, 1, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, M., Arsi, K., Donoghue, A.M.. Production and characterization of avian crypt-villus enteroids and the effect of chemicals. BMC Vet Res 2020, 16, 179. [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, A.A., Chaves, L.S., Lopes, K.L. Leandro A.M, Café N.S.M, & Stringhini, J. H. Inoculação de nutrientes em ovos de matrizes pesadas. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia, 2006, 35, 2018–2026.

- Jia, C. L., Wei, Z. H., Yu, M., Wang, X. Q., & Yu, F. Effect of in-ovo feeding maltose on the embryo growth and intestine development of broiler chicken. Ind Jour Anim Sci, 2011, 81, 503–506.

- Zhai, W., Gerard, P. D., Pulikanti, R., & Peebles, E. Effects of in ovo injection of carbohydrates on embryonic metabolism, hatchability, and subsequent somatic characteristics of broiler hatchlings. Poult Sci, 2011, 90, 2134–2143. [CrossRef]

- Retes, P. L. In ovo feeding of carbohydrates for broilers-a systematic review. J Anim Phys and Anim Nutr, 2018, 102, 2,361–369.

- Kadam, M. M., Bhanja, S. K., Mandal, A. B., Thakur, R., Vasan, P., Bhattacharyya, A., & Tyagi, J. S., Effect of in ovo threonine supplementation on early growth, immunological responses and digestive enzyme activities in broiler chickens. British Poult Sci, 2008, 49(6), 736–741. [CrossRef]

- Kadam M., Barekatain R., Bhanja Kumar S., Iji P.,Prospects of in ovo feeding and nutrient supplementation for poultry: The science and commercial applications - a review. In: Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2013, 93(15). 1-2.

- Alabi, J.O, Fafiolu, A.O, Bhanja, S.K, Oluwatosin, O.O, Onagbesan, O.M, Dada, I.D, Goel, A., Mehra, M., Gopi, M., Rokade, J.J., Kolluri, G. and Pearlin, B.V. 2022. In ovo L-Threonine feeding modulates the blood profile and liver enzymes activity of CARIBRO Vishal broiler chickens. Indian Journal Poultry Science, 2020, 57, 241-249. [CrossRef]

- Li D.L, Wang J.S, Liu L.J, Li K, Xu Y.B, Ding X.Q, Wang Y.Y, Zhang Y.F, Xie L.Y, Liang S, Wang Y.X, Zhan X.A, Effects of early post-hatch feeding on the growth performance, hormone secretion, intestinal morphology, and intestinal microbiota structure in broilers,Poult Sci, 2022, 101, 102133.

- S.I. Boersma S.I, Robinson F.E, Renema R.A, Fasenko G.M, Administering Oasis Hatching Supplement Prior to Chick Placement Increases Initial Growth with No Effect on Body Weight Uniformity of Female Broiler Breeders After Three Weeks of Age,J App Poult Res,2003, 12, 3, 428-434. [CrossRef]

- Al-Huwaizi H. J. N, Ammar H.A. The effect of fasting and early feeding after hatching with the nutritional supplement gel 95 and the safmannan prebiotic gel and the mixture between them on the productive performance of broiler chicks. IOP Conference Series. Earth and Environmental Science, 2021, 735(1).

- van der Wagt I, de Jong I.C, Mitchell M.A, Molenaar R, van den Brand H. A review on yolk sac utilization in poultry Poult. Sci., 2020, 99, 162–2175.

- Mousavi, S., Foroudi, F., Baghi, F., Shivazad, M., & Ghahri, H., The effects of in ovo feeding of threonine and carbohydrates on growth performance of broiler chickens. In: Proceedings of the British Society of Animal Science, 2009, 198-198. [CrossRef]

- Tahmasebi, S., & Toghyani, M. Effect of arginine and threonine administeredin ovoon digestive organ developments and subsequent growth performance of broiler chickens. J of Anim Phys and Anim Nutr, 2015, 100(5). 947–956.

- Kermanshahi, H., Golian, A., Khodambashi Emami, N., Daneshmand, A., Ghofrani Tabari, D., & Ibrahim, S. A. Effects of in ovo injection of threonine on hatchability, intestinal morphology, and somatic attributes in Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica). J of App Anim Res, 2016, 45(1), 437–441.

- Filho A, Ferket, P, Malheiros R, Bruno de Oliveira C.J, Aristimunha P, Wilsmann, D , Patricia G. Enrichment of the amnion with threonine in chicken embryos affects the small intestine development, ileal gene expression and performance of broilers between 1 and 21 days of age. Poult Sci. 2018, 98. 10.3382/ps/pey461. [CrossRef]

- Y.P. Chen, Y.F. Cheng, X.H. Li, W.L. Yang, C. Wen, S. Zhuang, Y.M. Zhou, Effects of threonine supplementation on the growth performance, immunity, oxidative status, intestinal integrity, and barrier function of broilers at the early age, Poult Sci, 2017, 96, 2,. [CrossRef]

- Law G.K, Bertolo R.F, Adjiri-Awere A, Pencharz P.B, Ball R.O, Adequate oral threonine is critical for mucin production and gut function in neonatal piglets Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol., 2007,292,G1293-G1301. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Zeng X, Mao X, Wu G, Qiao S. Optimal dietary true ileal digestible threonine for supporting the mucosal barrier in small intestine of weanling pigs J. Nutr., 2010, 140, 981.

- Lien K.A, Sauer W.C, Mosenthin R., Souffrant W.B, Dugan M.E. Evaluation of the 15N-isotope dilution technique for determining the recovery of endogenous protein in ileal digestion of pigs: Effect of dilution in the precursor pool for endogenous nitrogen secretion. J Anim. Sci., 1997, 75,148. [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Lugo M, Su C-L, and Austic R.E, Threonine Requirement and Threonine Imbalance in Broiler Chickens. Poult Sci, 1994, 73, 670–681. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC) Nutrient requirements of poultry. 9th Edition, National Academy Press, Washington DC. 1994.

- Ospina-Rojas I., Murakami A., Oliveira C., Guerra A. Supplemental glycine and threonine effects on performance, intestinal mucosa development, and nutrient utilization of growing broiler chickens. Poult Sci. 2013, 92, 2724–2731. [CrossRef]

- Corzo A, Kidd M.T, Dozier W.A, Pharr G.T, Koutsos D.A. Dietary threonine needs for growth and immunity of broilers raised under different litter conditions J. Appl. Poult. Res., 2007, 16, 574582.

- Azzam M.M.M, Dong X.Y, Xie P, Zou X.T. Influence of L-threonine supplementation on goblet cell numbers, histological structure and antioxidant enzyme activities of laying hens reared in a hot and humid climate Br. Poult. Sci., 2012, 53, 640.

- Star, M. Rovers, E. Corrent, J.D. Van der Klis. Threonine requirement of broiler chickens during subclinical intestinal Clostridium infection Poult. Sci., 2012, 91, 643.

- Geyra A, Uni Z, Sklan D. The effect of fasting at different ages on growth and tissue dynamics in the small intestine of the young chick. British J of Nutr. 2001, 86, 53–61. [CrossRef]

- Bigot K, Mignon-Grasteau S, Picard M, Tesseraud S. Effects of delayed feed intake on body, intestine, and muscle development in neonate broilers. Poult Sci. 2003, 82, 781–788. [CrossRef]

- Lamot DM, van de Linde IB, Molenaar R, van der Pol CW, Wijtten PJA, Kemp B; et al. Effects of moment of hatch and feed access on chicken development. Poultry Science. 2014, 93, 2604–2614. [CrossRef]

- Proszkowiec-Weglarz, M,Schreier L.L. , Kahl S., Miska K.B. , Russell B. , Elsasser T.H. Effect of delayed feeding post-hatch on expression of tight junction- and gut barrier-related genes in the small intestine of broiler chickens during neonatal development Poult. Sci., 2020, 99, 4714–4729.

- Alexandre L DE, B.M.F., Olivera, C.J.B., Freitas Neto, O.,C., Candice M C G DE,Leon, Saravia, M.M.S., Andrade, M.F.S., White, B. and Givisiez, P.E.N., Intra-Amnionic Threonine Administered to Chicken Embryos Reduces Enteritidis Cecal Counts and Improves Posthatch Intestinal Development. J of Immun Res. 2018, 9.

- Oort J, Scheper RJ. Histopathology of acute and chronic inflammation. Agents Actions Suppl. 1977, 25-30.

- Yonus, M., Nisa, Q., Munir, M., Jamil, T., Kaboudi, K., Rehman, Z., Shah, M. Viral hepatitis in chicken and turkeys. World's Poult Sci J, 2017, 73(2), 379-394. [CrossRef]

- Ito, NMK & Miyaji, CI & Lima, EA & Okabayashi, S & Claure, RA & Graça, EO. Entero-hepatic pathobiology: Histopathology and semi-quantitative bacteriology of the duodenum. BRAZ J POULT SCI. 2004, 6. 10.1590/S1516-635X2004000100005.

- van der Wagt, I., de Jong, I. C., Mitchell, M. A., Molenaar, R., van den Brand, H. A review on yolk sac utilization in poultry. Poult Sci, 2020, Volume 99, Issue 4, Pages 2162-2175, ISSN 0032-5791. [CrossRef]

- Harmon, B. G. Avian Heterophils in Inflammation and Disease Resistance. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77, 972–977.

| Hatching day | °C | CO2 concentration % |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Incubation | 37.9 | 0.60 |

| 2 | 37.9 | 0.60 | |

| 3 | 37.9 | 0.60 | |

| 4 | 37.9 | 0.60 | |

| 5 | 37.9 | 0.60 | |

| 6 | 37.9 | 0.60 | |

| 7 | 37.8 | 0.60 | |

| 8 | 37.8 | 0.60 | |

| 9 | 37.6 | 0.60 | |

| 10 | Candling | 37.6 | 0.60 |

| 11 | 37.5 | 0.35 | |

| 12 | 37.5 | 0.35 | |

| 13 | 37.4 | 0.35 | |

| 14 | 37.3 | 0.35 | |

| 15 | 37.3 | 0.35 | |

| 16 | 37.2 | 0.35 | |

| 17 | Candling, in-ovo intervention, placing into the incubator | 37.1 | 0.35 |

| 18 | 37.0/36.7 | 0.35/0.60 | |

| 19 | 36.7 | 0.60 | |

| 20 | 36.5 | 0.60 | |

| 21 | 36.2 | 0.60 | |

| 22 | 36.2/35.8 | 0.35 |

| Treatment code | Feed access | Early nutrition method | numbr of eggs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Int_0 | Immediate | - | 160 |

| IoS_0 | in ovo, saline | 160 | |

| Int_48 | 48h delayed solid feed access | - | 160 |

| IoS_48 | in ovo, saline | 160 | |

| IoT_48 | in ovo Thr | 160 | |

| Int_G48 | Hydrogel | 160 | |

| Int_GT48 | Hydrogel+Thr | 160 |

| Ingredients | Starter (1–10) |

Grower (11–21) |

Finisher (22–35) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn (grain) | 551 | 577 | 601 |

| Corn gluten (60%) | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Sunflower meal | 53.5 | 53.5 | 75 |

| Soybean meal (CP 44.2%) | 262 | 230 | 175 |

| Fat, vegetable | 44.7 | 55 | 67.00 |

| MCP | 18.7 | 17.5 | 15 |

| Limestone | 15 | 13.5 | 12.2 |

| NaCl | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| L-Lysin HCl | 5.2 | 4.6 | 4.3 |

| DL-Methionin | 4.5 | 3.9 | 3.2 |

| L-Treonin | 2.6 | 2.3 | 1.8 |

| Premix1 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Total | 1000.00 | 1000.00 | 1000.00 |

| Nutrient content (g/kg) | |||

| AMEn (MJ/kg) | 12.5 | 12.9 | 13.4 |

| DM % | 90 | 91.3 | 91.1 |

| Crude protein | 204.2 | 190.7 | 174.9 |

| Crude fat | 71.87 | 82.3 | 94.4 |

| Crude fiber | 41.5 | 41.1 | 44.8 |

| Lysine* | 13.5 | 12,1 | 10,8 |

| M + C* | 10.8 | 9.9 | 9.0 |

| Threonin* | 9.7 | 8,8 | 7,8 |

| Triptophan* | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.7 |

| Ca | 9.6 | 8.7 | 7.8 |

| P avaliable | 4.7 | 4.5 | 3.9 |

| Na | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Int_0 | IoS_0 | Int_48 | IoS_48 | IoT_48 | Int_G48 | Int_GT48 | RMSE | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d10 | 233a | 245b | 191c | 193c | 196c | 194c | 192c | 25.8 | <0.0001 |

| d21 | 855ab | 882a | 766c | 782cd | 809bd | 777cd | 785cd | 95.3 | <0.0001 |

| d35 | 2218a | 2238a | 2072b | 2113ab | 2086b | 2096ab | 2100ab | 257.4 | <0.0001 |

| Int_0 | IoS_0 | Int_48 | IoS_48 | IoT_48 | Int_G48 | Int_GT48 | RMSE | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed intake (kg/day/pen) | |||||||||

| d1-10 | 23.2a | 24a | 17.9b | 17.7b | 17.8b | 17.1b | 17.9b | 1.72 | <0.0001 |

| d11-21 | 72.8ab | 75.6a | 66.8c | 66.7c | 69.1bc | 67.3c | 66.8c | 1.36 | <0.0001 |

| d22-35 | 145.6a | 144.4a | 136.9b | 138.6ab | 137.6b | 138.6ab | 140.1ab | 6.22 | 0.04 |

| d1-35 | 85.35a | 86.3a | 78.3b | 78.2b | 79.3b | 78.9b | 79.1b | 3.52 | <0.0001 |

| Feed conversion ratio (kg feed/ kg gain) | |||||||||

| d1-10 | 1.24a | 1.21ab | 1.24a | 1.21ab | 1.18b | 1.15b | 1.23ab | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| d11-21 | 1.28ab | 1.3a | 1.28ab | 1.24ab | 1.24b | 1.26ab | 1.23b | 0.77 | 0.001 |

| d22-35 | 1.49b | 1.48b | 1.45ab | 1.45a | 1.5b | 1.46a | 1.48b | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| d1-35 | 1.37ab | 1.37ab | 1.35b | 1.32bc | 1.36ac | 1.34c | 1.34c | 0.13 | 0.043 |

| Average daily gain (g/d) | |||||||||

| d1-10 | 18.6b | 19.8a | 14.4c | 14.6c | 15.0b | 14.8b | 14.5b | 2.57 | <0.0001 |

| d11-21 | 56.5ab | 57.9a | 52.1c | 53.5bc | 55.6ab | 53.0bc | 53.9bc | 7.1 | <0.0001 |

| d22-35 | 97.5 | 97.1 | 93.8 | 95.0 | 91.2 | 94.5 | 94.2 | 14.28 | 0.13 |

| d1-35 | 62.0a | 62.6a | 57.8b | 59ab | 58.3b | 58.5ab | 58.7ab | 7.19 | <0.0001 |

| Int_0 | IoS_0 | Int_48 | IoS_48 | IoT_48 | Int_G48 | Int_GT48 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Villus height (µm) | ||||||||

| D | 580.8ab | 506.5a | 673.2b | 639.8ab | 621.8ab | 579.2ab | 586.1ab | 0.032 |

| I | 302.6a | 295.4a | 363.6ab | 375.3b | 358.7ab | 400b | 364.5ab | 0.0011 |

| C | 318.3ab | 377.8a | 347.2ab | 308.1ab | 357.3a | 310.5ab | 258.2b | 0.0055 |

| Crypt depth (µm) | ||||||||

| D | 111.3a | 110.3a | 109.5a | 80.5b | 115.4a | 100.1ab | 103.9ab | 0.001 |

| I | 88.1 | 94.6 | 93.3 | 94.9 | 83.4 | 106.0 | 85.6 | 0.16 |

| C | 92.5ab | 87.4a | 104.5b | 81.4a | 110.5b | 94.4ab | 82a | 0.0004 |

| Villus height/Crypt depth ratio | ||||||||

| D | 4.3a | 4.6a | 4.8a | 8.2b | 5.5a | 5.1a | 3.9a | <0.001 |

| I | 3.4ab | 3a | 3.8ab | 4ab | 3.8ab | 3.8ab | 4.4b | 0.0082 |

| C | 4.0 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 0.28 |

| Int_0 | IoS_0 | Int_48 | IoS_48 | IoT_48 | Int_G48 | Int_GT48 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Villus height (µm) | ||||||||

| D | 340.6c | 214.9a | 288.5b | 240.8b | 283.4b | 321.6bc | 250.0ab | <0.001 |

| I | 158.6 | 140.2 | 167.4 | 140.8 | 154.7 | 157.1 | 142.9 | 0.057 |

| C | 164.2b | 126.4a | 159.8ab | 146.4ab | 156.5ab | 132.1ab | 130.0ab | 0.0085 |

| Crypt depth (µm) | ||||||||

| D | 36.3 | 29.2 | 35.6 | 34.0 | 36.5 | 31.8 | 35.6 | 0.43 |

| I | 32.5 | 30.3 | 33.7 | 29.6 | 32.6 | 33.6 | 32.8 | 0.14 |

| C | 29.9 | 25.3 | 30.3 | 29.1 | 28.3 | 26.5 | 26.7 | 0.059 |

| Villus height/Crypt depth ratio | ||||||||

| D | 7.7 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 9.2 | 7.2 | 0.28 |

| I | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 0.96 |

| C | 5.7b | 5.1b | 3.7a | 4.5ab | 4.5ab | 4.9b | 4.9b | 0.006 |

| Int_0 | IoS_0 | Int_48 | IoS_48 | IoT_48 | Int_G48 | Int_GT48 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Villus height (µm) | ||||||||

| D | 768.9ab | 748.8ab | 830.9a | 790.8ab | 755.6ab | 690.1b | 765.8ab | 0.04 |

| I | 210.6a | 221.3ab | 216.1a | 199.3a | 282.8b | 218.7a | 180.4a | 0.0004 |

| C | 214.9 | 235.3 | 220.8 | 237.9 | 205.2 | 211.1 | 217.2 | 0.45 |

| Crypt depth (µm) | ||||||||

| D | 86.1 | 103.5 | 106.8 | 89.5 | 97.4 | 104.5 | 113.2 | 0.09 |

| I | 61.8 | 59.2 | 55.3 | 58.4 | 72 | 66.8 | 60.7 | 0.08 |

| C | 61.9 | 64.3 | 54.3 | 56.1 | 58.8 | 56.1 | 55.2 | 0.26 |

| Villus height/Crypt depth ratio | ||||||||

| D | 9.6a | 7.8ab | 8.1ab | 9.1ab | 8.2ab | 6.6b | 7.4ab | 0.01 |

| I | 3.5ab | 3.8ab | 4ab | 3.5ab | 4.2a | 3.3ab | 3b | 0.01 |

| C | 3.6 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 0.29 |

| Int_0 | IoS_0 | Int_48 | IoS_48 | IoT_48 | Int_G48 | Int_GT48 | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterophil granulocyte infiltration | ||||||||

| day 1 | 0.66ab | 0.75ab | 1.0b | 0.58a | 1.0b | 1.0b | 1.0b | 0.01 |

| day 3 | 0.41ab | 1.0b | 0.25a | 0.57ab | 1.0b | 1.0b | 0.75ab | 0.0007 |

| day 21 | 1.1ab | 0.3a | 0.58a | 1.41b | 1.66b | 1.19ab | 1.6b | <0.001 |

| Vacuolization | ||||||||

| day 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| day 3 | 0.16ab | 0a | 0a | 0.42b | 0a | 0a | 0a | 0.017 |

| day 21 | 0a | 0a | 0a | 0.28b | 0a | 0a | 0a | 0.007 |

| Mononuclear infiltration | ||||||||

| day 1 | 0a | 0a | 0a | 0.25 | 0a | 0a | 0a | 0.01 |

| day 3 | 1.41b | 0.33a | 0a | 0.71ab | 0.5a | 1ab | 0a | 0.008 |

| day 21 | 1.77ab | 2b | 1.6ab | 1.3ab | 2.33b | 1.33a | 1.33a | <0.001 |

| Lipid accumulation in liver cells | ||||||||

| day 1 | 1.0a | 1.2b | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a | 0.014 |

| day 3 | 0.25a | 1.66c | 0.75ab | 1.0b | 1.0b | 1.0b | 1.0b | <0.001 |

| day 21 | 0a | 0a | 0a | 0a | 0a | 0.8b | 0.4ab | <0.001 |

| Int_0 | IoS_0 | Int_48 | IoS_48 | IoT_48 | Int_G48 | Int_GT48 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At hatch | ||||||||

| HE | -- | 0.715 | 0.6 | 0.728 | 0.586 | 0.676 | 0.715 | 0.09 |

| LYM | - | 0.216 | 0.316 | 0.198 | 0.305 | 0.241 | 0.216 | 0.13 |

| MON | - | 0.019 | 0.036 | 0.026 | 0.025 | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.10 |

| EOS | - | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.068 | 0.067 | 0.048 | 0.86 |

| 48 hours post-hatch | ||||||||

| HE | 0.629 | 0.529 | 0.619 | 0.597 | 0.610 | 0.525 | 0.629 | 0.052 |

| LYM | 0.291 | 0.386 | 0.305 | 0.339 | 0.314 | 0.397 | 0.291 | 0.79 |

| MON | 0.035 | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.025 | 0.034 | 0.028 | 0.035 | 0.90 |

| EOS | 0.045 | 0.038 | 0.048 | 0.039 | 0.042 | 0.050 | 0.045 | 0.05 |

| 21 days of age | ||||||||

| HE | 0.314 | 0.323 | 0.296 | 0.346 | 0.317 | 0.357 | 0.314 | 0.33 |

| LYM | 0.578 | 0.579 | 0.613 | 0.570 | 0.571 | 0.563 | 0.578 | 0.82 |

| MON | 0.054 | 0.043 | 0.040 | 0.035 | 0.044 | 0.040 | 0.054 | 0.47 |

| EOS | 0.053 | 0.055 | 0.051 | 0.049 | 0.065 | 0.040 | 0.053 | 0.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).