1. Introduction

Animal models are a valuable source of information on the processes occurring in living organisms, enabling their use at least to a partial extent in the description of processes in the human body, where for bioethical reasons such studies are impossible to conduct [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Flores-Santin and Burggen [

5] indicate

Gallus domesticus as the third organism after mice and rats in terms of application in medical research. Hence, experiments using

G. domesticus can provide information on processes related to the development of the gastrointestinal tract, especially hindgut and intestinal digestion in response to the type of diet and in immunology, where in recent years they have also been used as model organisms to investigate the effect of light pollution on intestinal injury [

6,

7,

8]. From the nutritional point of view of broiler chickens, concentrate mixtures based on the use of post-extraction soybean meal and a high share of wheat grain may show a deficiency of dietary fibre (DF) necessary for the proper functioning of both the upper and lower digestive tract [

9,

10,

11,

12]. A high amount of wheat, triticale or barley grain in the diet, especially in young animals, may have an antinutritional effect due to the presence of arabinoxylans belonging to non-starch polysaccharides (NSP), which lowers the passage rate of digesta [

13,

14]. These compounds are present in cereal grains in soluble and insoluble forms, but their proportion affects the physicochemical properties of the food content related to viscosity, solubility, water holding capacity, fermentability, bulk and ability to bind bile acids [

15,

16]. One way to limit the soluble fibre contained in wheat grain is to add components rich in structural carbohydrates, not exceeding their share in the amount of 2-3% in concentrate mixtures for broiler chickens depending on the age of the birds [

17,

18,

19].

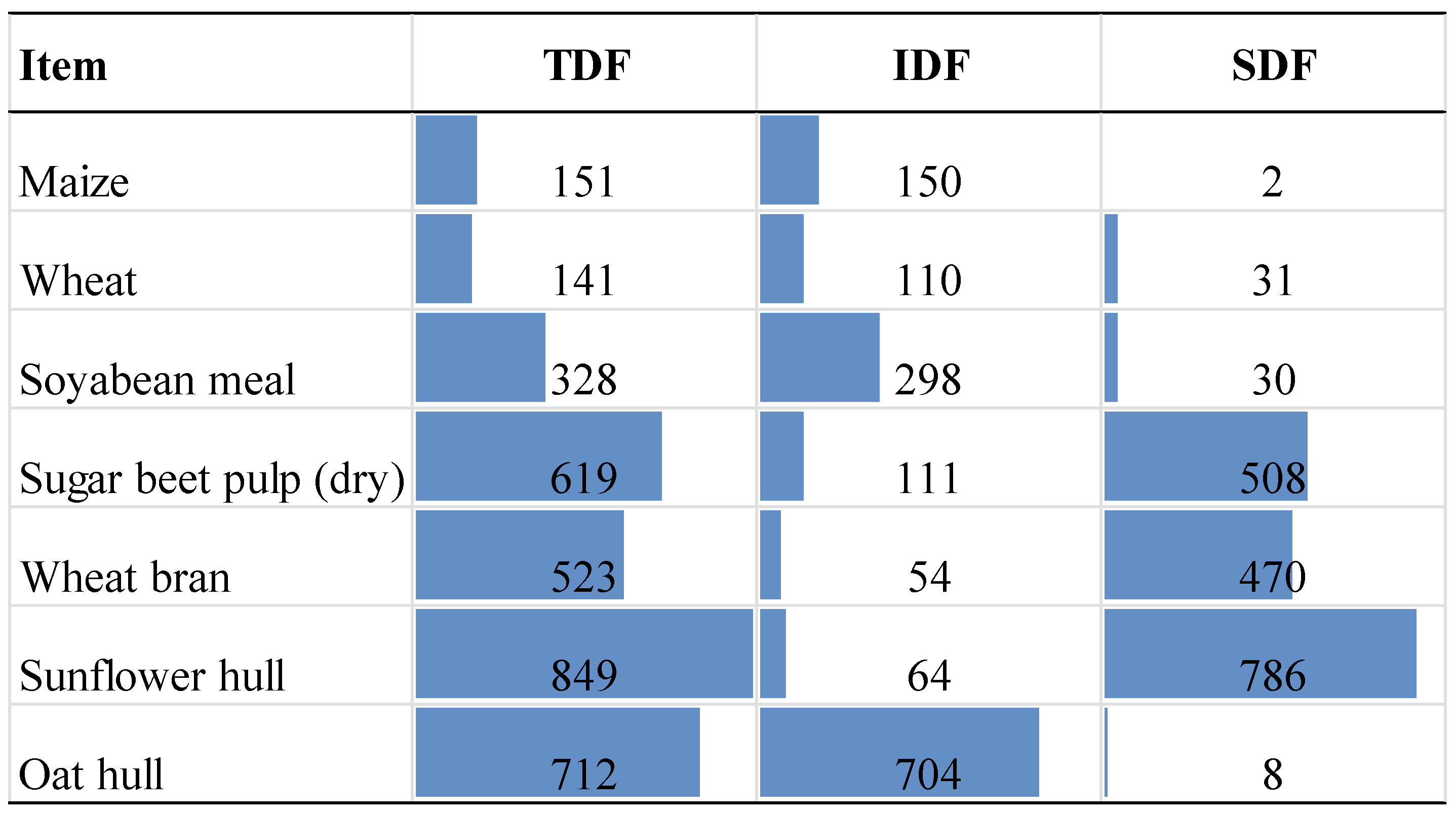

Taking into account the results for monogastric animals, a better definition of dietary fibre seems to be the analysis of Asp [

20] and taking into account: total dietary fibre (TDF), insoluble dietary fibre (IDF) and soluble dietary fibre (SDF). The by-products of the agro-food industry show different contents of soluble and insoluble fibre [

21,

22]. The component rich in insoluble fibre is oat hull (OH), where the main component is lignocellulose composed of insoluble cellulose (35-45%), hemicelluloses (32-35%) and acid-insoluble lignin (17-20%) [

23,

24,

25]. On the other hand, sunflower hull (SH), soybean hull, sugar beet pulp (SBP) and wheat bran (WB) show a higher amount of SDF [

26,

27]. The differentiation of the SDF and IDF composition within the components affects the production parameters of birds and the length and weight of selected digestive sections, as well as the organs associated with it, and consequently the health of birds related to ‘gut health’ [

15,

28,

29].

Studies related to the effect of different fibre sources on the gastrointestinal tract of birds are not a new issue and such comparisons have been performed earlier by many research teams [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Naeem et al. [

34] also consider the use of a small addition OH in the diet as a factor that can significantly reduce nitrogen emissions to the environment. However, there are few comparisons in the literature that take into account all the components taken into account when modelling changes depending on changes in the amount of DF in the diet [

35]. Multiple regression is a type of analysis in which independent variables have an impact on a single dependent variable, and its development also allows for Path analysis [

36]. This allows for the construction of a regression equation that can be used to model the process of changes within all factors that are important in the overall model of a given phenomenon, including in the case of the production process or digestion in the digestive tract of animals, as long as they form a logical whole [

37]. This type of analysis is used in the study of amino acid digestibility or in determining the relationship between blood markers and abdominal fat in broiler chickens [

8,

38].

The aim of the experiment was to compare the use of diets containing 50% of wheat grain with 3% of various crushed components rich in structural carbohydrates in the nutrition of broiler chickens on the formation of production parameters, weight or length of selected sections of the digestive tract and to take into account the data obtained during the measurements to create regression equations describing the range of changes depending on the types of fibre added to the mixtures during their preparation on all variables related to the measurements of the digestive tract from the proventriculus to the large intestine.

2. Results

2.1. Performance of Broiler Chickens

Table 1 presents performance of broiler chickens during entire experiment. In case of body weight (BW) at day 7 when chickens were allocated to groups no significant differences were stated (p>0.05). In day 21 in comparison with an application of 3 % of OH (0.56 kg) significantly decreased (p<0.01) BW of broiler chickens in comparison with control group (0.65).

Application of SH (0.64 kg) in this period gives results similar to control group (0.65 kg). On day 35 no significant difference was stated (p>0.05) from point of view oat and SH (in both cases 1.73 kg), but chickens in control group (1.77 kg) was significantly heavier (p<0.01) than in group with additional sources of soluble fibre: SBP and WB (respectively 1.66 and 1.64 kg).

Between days 7-21 the highest intake of feed (p<0.01) was noted in chickens where 3% of SBP was used (1.03 kg), the lowest was stated in case of WB (0.94 kg). In period between days 21-35 the highest feed intake (p<0.05) was noted in case of chickens fed diet with SH and WB (respectively 1.84 and 1.81 kg per bird), lowest were noted in treatment of broiler chickens fed diet with OH (1.71 kg). Taking into a consideration period from between days 7 and 35 day of life intake of feed wasn’t statistically significant (p>0.05).

The lowest FCR (p<0.01) in period from 7 to 21 days of life of broiler chickens was observed in case of control diet and SH treatment (respectively 1.87 and 1.95 kg/kg). From the other side the highest FCR (p<0.01) was noted in treatment of chickens fed diet with 3% of OH (2.35 kg/kg). In period from 21 and 35 days of life the lowest FCR (p<0.01) was stated in treatment of chickens fed 3% OH diet (1.53 kg/kg) and control group (1.59 kg/kg). Beside of this highest amount of feed per kg of growth (p<0.01) was observed in case of treatment fed diet with 3 % of WB (1.77 kg/kg). Taking into a consider FCR from entire experiment the lowest value (p<0.01) was noted in control group of chickens (1.68 kg/kg), but difference was statistically significant with 3% treatment (1.86 kg/kg).

2.2. Weight of Individual Organs

During experiment weight of individual organs was analysed (

Table 2). The heaviest proventriculus (p<0.01) was observed in case of WB (8.0 g), the lightest in case of control group and OH treatment (respectively 6.8 and 6.7 g).

From point of view significance level at p<0.05, chickens fed diet with WB, SH and SBP (respectively 8.0, 7.5 and 7.6 g) have significant heavier proventriculus than mentioned bird of control group and OH treatment. The heaviest gizzard (p<0.01) was stated in case of 3% OH treatment (35.4 g) and 3% SH treatment (33.8 g) the lowest in case of control group (26.1 g). Difference in weight of heart was also observed (p<0.01), the heaviest was stated in chickens fed diet with OH (12.3 g), the lightest in treatment fed diet with 3% of SH. At significance level (p<0.05) heart in case of broiler chickens fed diet with OH was significant heavier in comparison with treatments of chickens obtaining WB or SH (respectively 10.1 and 9.9 g). In case of liver no significant differences was proved (p>0.05).

2.3. Length of intestines

Table 3 presents lengths of gastrointestinal tract of birds from duodenum to large intestine. Analysing duodenum length the longest (p<0.01) was measured in SH treatment of chickens (28.3 cm), whereas the shortest in case OH treatment (25.6 cm). No significant differences (p>0.05) was stated between OH and SBP treatments (respectively 25.6 and 26.5 cm).

No significant differences was stated in case of jejunum length (p=0.09). The longest ileum (p<0.01) was measured in case of control group and OH treatment of chickens (respectively 77.6 and 77.3 cm) in comparison with SH and SBP (respectively 70.3 and 70.2 cm). No significant differences was observed in length of ceca between treatments (p>0.05). In control group and OH treatment of broiler chickens (in both cases 9.7 cm) the longest large intestine was stated (p<0.01), whereas in SBP treatment this part of gastrointestinal tract was the shortest (8.2 cm). Taking into a consideration total length of intestines the longest was stated in case of control group (210.3 cm) in comparison with SBP treatment where 193.3 cm were stated at the significance level p<0.01.

2.4. Correlation Between Dietary Fibre Types and Measurements of Intestines and Organs

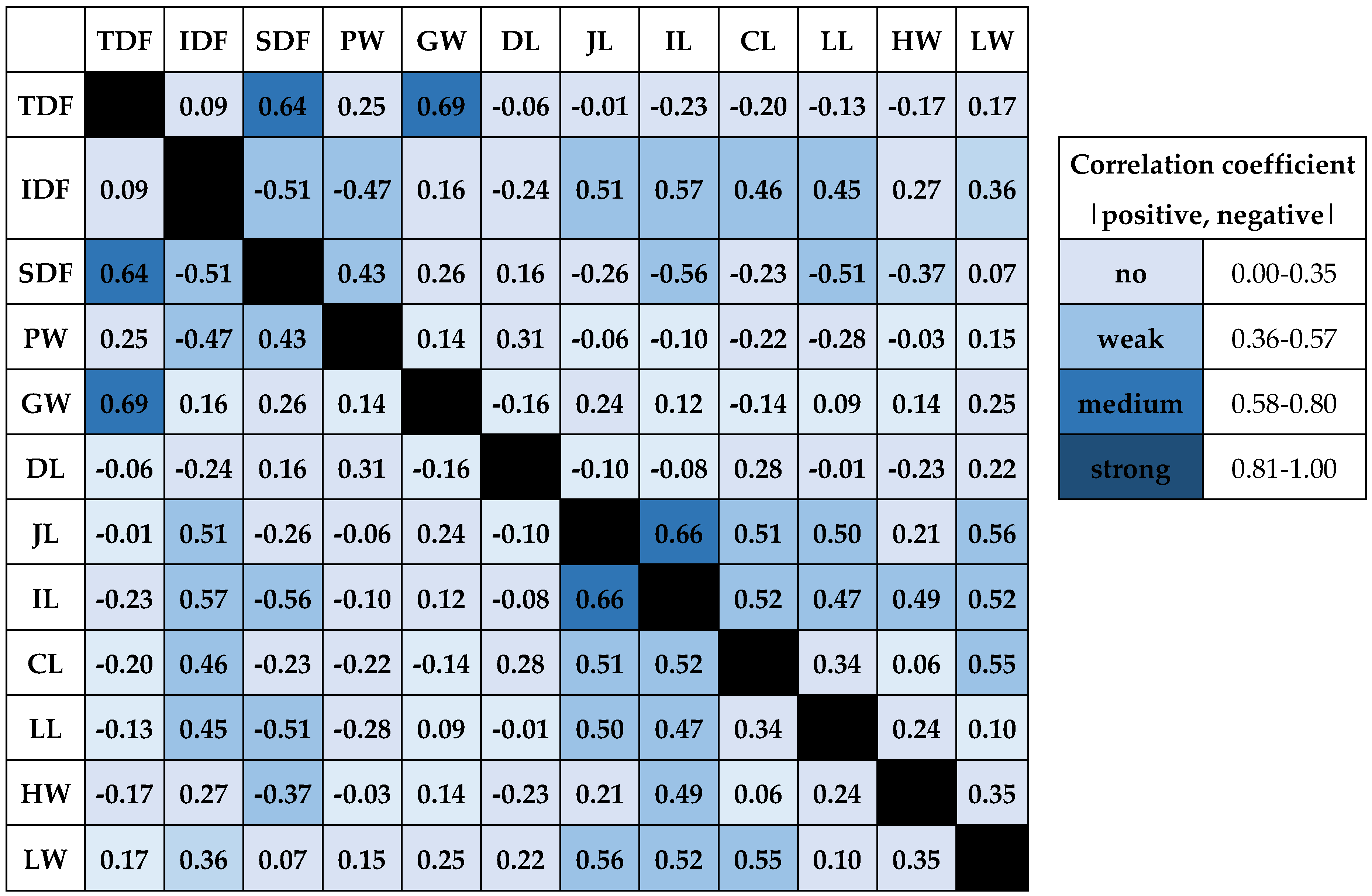

Figure 1 presents the relationship between individual variables calculated using Spearman correlation. A moderate positive correlation (p<0.05) was found between TDF contained in chicken diet and SDF (r = 0.64), as well as between TDF content in diet and gizzard weight (r = 0.69). A weak negative correlation was found in the digestive tract of chickens between IDF fibre and SDF (r = -0.51) and IDF and proventriculus weight (r = -0.47).

However, a weak positive correlation was found between IDF and intestines from jejunum to large intestine inclusive, in the r range from 0.45 to 0.57. A weak positive correlation was also determined between IDF content and liver weight (r = 0.36). The weight of the muscular stomach was positively weakly correlated with the SDF level (r = 0.43) and negatively weakly with the IDF level (r = - 0.47). No significant correlations were found between the weight of the glandular stomach and the measurements of the remaining intestinal sections and organ weights (p>0.05). The weight of the muscular stomach was moderately positively correlated with the amount of TDF in the diet (r = 0.69), and no significant correlations were found for the remaining variables (p > 0.05). There was also no correlation for the length of the duodenum and the remaining variables (p > 0.05). In the case of jejunum length, a moderate positive correlation was found in relation to the level of IDF in the diet (r = 0.51). The increase in the length of this section of the digestive tract was also moderately positively correlated with the remaining sections of the intestines in the r coefficient range from 0.50 to 0.56. The liver weight is also correlated to a similar extent (r = 0.56). In the case of the ileum, moderate positive correlations were found with respect to IDF (positive, r = 0.57) and to SDF (negative, r = -0.56).

The length of the ileum was also moderately positively correlated with the length of the jejunum (r = 0.66) and weakly with the length of the cecum (r = 0.52) and large intestine (r = 0.47). In addition, the length of this section was weakly positively correlated with the weight of the heart and liver (r = 0.49 and r = 0.52, respectively). The length of the cecum was positively and weakly correlated with the level of IDF in the feed (r = 0.46), and a weak correlation was also indicated for this variable and the length of the jejunum and ileum (r = 0.51 and r = 0.52, respectively). A similar level of correlation (r = 0.55) was observed between the length of the cecum and the weight of the liver. The length of the large intestine was weakly positively correlated with the level of IDF (r = 0.45) and weakly negatively with the level of SDF (r = -0.51) in the diet of broiler chickens and weakly positively with the lengths of the small intestine components (r = 0.50 and r = 0.47, respectively). In the case of heart weight, only a weak positive correlation (r = 0.49) was found with the length of the ileum. Liver weight showed a weak positive correlation with dietary IDF level (r = 0.36), heart weight (r = 0.35). Liver weight was also weakly correlated with jejunum, ileum and cecum lengths, with r ranging from 0.52 to 0.56.

2.5. Model of Development of Gastrointestinal Tract of Broiler Chickens at Day 35

Analysing the process of modelling equations for individual variables in the multiple regression model, a significant effect of independent variables on jejunal length was found (p = 0.002, R2 = 0.59), the length of the large intestine and liver weight were of significant importance for the value of the dependent variable in this case.

Table 4.

Multiple regression equations taking into account the effect of dietary fibre and the measurements analysed in the experiment.

Table 4.

Multiple regression equations taking into account the effect of dietary fibre and the measurements analysed in the experiment.

| DV |

Intercept |

Coefficients for independent variables as constituents of equation with sign |

p-value |

R2 |

| TDF |

IDF |

SDF |

PW |

GW |

DW |

JL |

IL |

CL |

LL |

HW |

LW |

| PW |

3.855 |

0.000 |

-0.043 |

0.025 |

- |

0.029 |

0.160 |

0.068 |

0.054 |

-0.173 |

-0.229 |

0.130 |

-0.033 |

0.125 |

0.24 |

| GW |

-45.687 |

0.436 |

-0.101 |

-0.186 |

0.787 |

- |

-0.399 |

-0.065 |

0.000 |

-0.044 |

1.398 |

-0.134 |

0.357 |

0.073 |

0.30 |

| DW |

26.527 |

0.016 |

-0.045 |

0.000 |

0.732 |

-0.068 |

- |

-0.267 |

0.002 |

0.503 |

0.818 |

-0.270 |

0.202 |

0.144 |

0.22 |

| JL |

31.861 |

-0.061 |

0.072 |

0.082 |

0.748 |

-0.026 |

-0.640 |

- |

0.299 |

0.236 |

1.533* |

-0.578 |

0.500* |

0.002 |

0.59 |

| IL |

8.718 |

-0.084 |

0.138 |

-0.127 |

1.065 |

0.000 |

0.010 |

0.539 |

- |

0.585 |

-0.643 |

0.638 |

0.108 |

0.002 |

0.58 |

| CL |

3.550 |

-0.097 |

0.082 |

0.079 |

-0.378 |

-0.004 |

0.239 |

0.047 |

0.064 |

- |

0.066 |

-0.108 |

0.159 |

0.002 |

0.43 |

| LL |

-0.409 |

-0.016 |

0.014 |

-0.018 |

-0.232 |

0.053 |

0.181 |

0.141* |

-0.033 |

0.030 |

- |

0.094 |

-0.093 |

0.099 |

0.27 |

| HW |

11.913 |

0.045 |

-0.032 |

-0.104 |

0.443 |

-0.017 |

-0.200 |

-0.179 |

0.109 |

-0.169 |

0.316 |

- |

0.186 |

0.177 |

0.19 |

| LW |

-32.160 |

0.157 |

-0.128 |

-0.077 |

-0.335 |

0.135 |

0.448 |

0.461* |

0.056 |

0.739 |

-0.930 |

0.555 |

- |

0.007 |

0.51 |

In addition, independent variables also had an effect (p = 0.002) on dependent variables in the form of ileal and caecal length (R2 = 0.58 and R2 = 0.43, respectively), but none of the individual variables had a more significant effect than the others (p>0.05). A significant effect of independent variables was also found in the case of liver weight (p=0.007, R2=0.51) and in this case jejunal length was a significant component of the regression equation (p<0.05). The trend was also found in the case of equations describing the parameters of the muscular stomach weight and large intestine length (0.073 and 0.099, respectively). There was no significant influence of independent variables on the dependent variable such as the weight of the glandular stomach, heart weight, or duodenum length (p>0.05).

3. Discussion

3.1. Animal Models in Human Study

Animal models help explain the nature of phenomena occurring in living organisms. In the case of

Gallus domesticus, research is carried out on adults, but some experiments are also performed on embryos, thanks to which research using this type of model organisms is used in developmental biology, virology, immunology, oncology, epigenetic regulation of gene expression and understanding of human disease [

4,

39,

40,

41]. Fu and Cheng [

42] linked the animal model and dysbiosis in the cecum with the occurrence of aggressive behaviour in poultry, the mechanism of which can also be compared to dysbiosis of the large intestine in humans in neuropsychiatric studies. The hindgut seems to be the most promising part of the digestive tract of broiler chickens where studies can be conducted using dietary fibre and its effect on the development of individual sections, as well as the relationship with microflora and stress behaviours related to fibre balance and microbial dysbiosis caused by stressors [

43]. Ojo et al. [

44] in their meta-analysis and systematic review emphasized that low concentration of dietary fibres in diet with the presence of products wealth with fat and sugars can favoured the appearance of diabetes type 2 in this group of people. Niekamp and Kim [

45] on the other hand, noted an association between microbial dysbiosis in the colon and the metabolites produced by them with an increase in the occurrence of colorectal cancer.

Of course, due to the specificity of animal nutrition and the structure of their digestive tracts, not all processes can be fully reproduced in human nutrition, but the processes occurring in some sections have a similar course, especially when is taken into account the structure of the epithelium and the relationship between it and the symbiotic microorganisms occurring in a given section, which affect the maintenance of intestinal health and cooperation with the body’s immune system [

46]. However, as Shehata et al. [

47] emphasize, from the point of view of gut health, in the case of poultry, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are the dominant groups of microorganisms, while in the case of humans, the ratio between them constitutes a health/meatbolism associated marker. This creates the possibility of transferring part of the research to model organisms and comparing also using analyses of the possibilities of regenerating the microflora and epithelium, the damage of which can also be induced as a result of the occurrence of stress factors, similarly to the studies by Ji et al. [

48] where AA broiler model was used to check improvement of intestinal barrier by

Bacillus subtilis M6, from which results can also be used in the case of humans. In the case of

Gallus domesticus, the physiological structure of the upper digestive tract has practically no replication in the structure of the human digestive tract, the gizzard compensates for the lack of teeth, the crop plays the role of storing food and preparing it for further digestion processes, only the glandular stomach performs a similar function to the human stomach [

49]. The situation is different in the intestinal section, where the processes that occur can be comparable to other monogastric animals, in this case also with the specificity of digestion in humans. In the case of the cecum, they can be a replication of the processes occurring in humans in the colon and be related to research aimed at reducing dysbiosis in this region with a simultaneous effect on the regeneration of the epithelium associated with the reconstruction of the mucin layer [

47]. Also, the study of the digestibility and absorption of nutrients takes place up to the end of the ileum; the results of such comparisons can be used to create models of processes occurring in the human digestive tract related to disorders of the digestive process and the regeneration of the interaction of the digestive and immune system microflora.

The subject of the study was to compare changes in the digestive tract of broiler chickens as representatives of

Gallus domesticus, less typical than slow-growing birds in the form of laying birds, of course subjected to genetic selection in terms of body weight gain and the most efficient use of feed [

50]. However, even in the case of such a short growth period, adaptations of some sections of the digestive tract to the type of diet received are visible, for example Tejeda and Kim [

51] draw attention to the phenomenon of compensation for the growth of birds as a result of the use of a small amount of additional DF (especially IDF) in the diet, which increases the intake of nutrients from the diet and affects the better use of feed. Additionally, the parent flocks of these birds also require maintaining a special diet balance to enable the achievement of high egg production, and therefore a large number of chicks, and thus this can be achieved by diluting the diet to a greater extent than in fast-growing birds [

52]. Similarly, in laying hens, lower energy and nutrient requirements allow the use of up to 10% lignocellulose [

53].

3.2. Diet Differentiation and Dietary Fibre

In the case of the conducted studies, the differentiating factor was various components obtained as by-products of the agri-food industry with a different share of SDF and IDF, which affect the dynamics of processes occurring in the digestive tract [

15,

35]. In addition, based on the collected empirical data, an attempt was made to fit the data to multiple regression equations in order to create a network model of connections of this type of phenomena for the entire digestive tract from the proventriculus to the large intestine inclusive. Individual groups were differentiated by the amount of structural components (3% of the diet share) rich in DF, five different diets were prepared, which were isoenergetic and isoproteic for both rearing periods. However, they contained different proportions of IDF and SDF, which was supposed to modify the process of gastrointestinal development and its adaptation to the type of diet consumed, affect the rate of content flow and, consequently, the degree of absorption of nutrients from the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract, which also affects the growth rate of birds, feed efficiency and health [

18,

54].

From OH as a source of lignocellulose, it is also possible to obtain hydrophobic cellulose constituting waterproof cellulose or nanocellulose surfaces that can be used in medicine, pharmaceuticals, agriculture and industry [

55]. It is also possible to obtain pectin from SBP and their further possible conversion to pectinooligosaccharides, which have prebiotic properties in stimulating probiotic bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract [

56]. They also positively influence the gastrointestinal immune barrier due to the interaction of the gastrointestinal microbiome, the host intestinal epithelium and the immune system [

57].

3.3. Performance of Broiler Chickens

In poultry nutrition, NSP contained in wheat grain used in large amounts in the diet can cause problems with digestion and absorption of components from the intestinal lumen, affecting body weight gain, but also changes in the microflora in the intestinal section, which affect the deterioration of litter quality and the creation of conditions favourable to the development of pathogenic bacteria [

58,

59]. Hence, in the case of starter (1-20 days) and grower (21-35 days) diets, the diets consisted of more than 50% of wheat grain. During balancing, isoenergetic and isoproteic diets were prepared. In the starter period, 12.5 MJ of metabolic energy and 220 g of total protein, while in the grower period, 13.0 MJ of metabolic energy and 200 g of total protein. The differentiating element in the individual diets was the content of TDF and its IDF and SDF fractions. The use of structural components increased the level of TDF, but also differentiated the individual diets in terms of IDF and SDF. The use of OH in amount of 3% increased the share of IDF in this group compared to the control group and a practically imperceptible increase in SDF, as this component consists mainly of insoluble fibre. In the other groups, the component used in a share of 3% (SH, SBP and WB) was a source of mainly soluble fibre, which almost doubled its content in the diet compared to the control group, but also reduced the content of insoluble fibre in these diets when the values are compared to the control group.

Table 1 presents the results of rearing chickens from 7 to 35 days of age. During the first days, the birds were kept together, while on day 7 they were assigned to individual replications within the treatments, maintaining an average body weight of 133 g within each. Feeding from 7 to 21 days of life affected the variability of the body weight of broiler chickens. The use of 3% OH significantly reduced the body weight gain (BWG) of chickens compared to the control group. The reason for these results could be the feeding of the birds with the control diet from the first to 7 days of life and too high a share of OH in this period as a result of a change in the diet when the gastrointestinal tract was not yet adapted to increased absorption of nutrients. Juanchich et al. [

60] emphasize in their studies that the size of the intestine and size of organs increases rapidly in the first days of development of the gastrointestinal tract. The change in diet required the adaptation of the chickens’ digestive tract to the new diet, which explains the lower growth of the chickens receiving OH, only later, as a result of the compensation mechanism, did the chickens’ digestive tract allow them to achieve a higher BW than in the other groups. Similar results were obtained in the studies of Rasool et al. [

61], feeding birds a diet containing 3% OH resulted in a significantly lower body weight of the chickens compared to the control group. Its amount during this period resulted in significantly lower feed utilization by the chickens compared to the group receiving SH or SBP.

Analysing the studies of Gonzalez-Alvarado et al. [

62], feeding OH from the first to the day 10 day significantly affects (p<0.01) the increase in BWG and FCR of broiler chickens compared to the control group, in this period SBP also increases FCR compared to the control group. Interestingly, SH did not significantly affect the BW differences compared to the control group, while in the case of SBP and wheat bran the difference was significant (p<0.05). Similarly, in the study by Kimiaeitalab et al. [

63], no differences in ADG were found between the control group and chickens fed a diet with 3% SH in the ranges from 0 to 9 days of life and between 10 and 21 days of life.

In the rearing period from 21 to 35 days, the growth of the birds in the group receiving OH in the diet was compensated for they consumed the lowest amount of feed, but the adaptation of the gizzard during this period allowed for much more effective use of feed than in the previous period when the gizzard was not developed; feed use was also the highest during this period. This indicates the possibility of using 3% OH without any problems in this period with the prospect of increasing its amount in the next period or introducing it interchangeably with whole cereal grain. Similar results were obtained in the study by Gonzalez-Alvarado et al. [

62], where the use of OH resulted in significantly higher body weight gains compared to the control group and the group receiving SBP. Also, Kakhki et al. [

64] obtained the highest body weight of chickens during the entire rearing period on the day 14, 28 and 36 of rearing when using OH, slightly worse results were obtained when using WB, while the body weight of chickens was significantly worse (p<0.05) when SBP was used in the diet. In the conducted experiment, the data of chickens receiving dried SBP and WB are definitely worse in comparison to all treatments, which indicates that high amount of these components affect the deterioration of the motility of the content and reduce the absorption of nutrients, and this also adversely affects the production results in broiler chicken rearing. This indicates the influence of SBP in the fermentation process and the impact on gut health, or a more effective use of it in ducks or geese. Similar observations were published in the study Bamedi et al. [

27] conducting an experiment on Japanese quail, they found a significant deterioration in production parameters when SBP constituted 4% of the diet, 2% of the diet affected similar or better production results compared to the control group. On the other hand, products obtained from SBP in the form of oligosaccharides have significant applications in human nutrition. Taking into account all the additives, the most stable solution seems to be SH, which practically does not differ in results from the control diet, but over the entire period the cost of feeding is higher compared to this diet. The most promising in this case seems to be the diet containing OH, but to achieve better results it would be necessary to reduce its use in the first week to 1%, and then gradually increase it, even to 5% in broiler chickens reared longer.

3.4. Analiza Morfometryczna Wybranych Organów ich Korelacja z Włóknem Pokarmowym w Diecie

The use of a higher amount of TDF and consequently SDF in the diet of chickens through the use of components in the form of SH, SBP and WB increased the weight of the proventriculus producing HCl and protein-degrading enzymes [

63]. The study did not determine the weight of the pancreas, but due to the higher viscosity of the feed content, the digestive system responded by increasing the production of amylase [

65,

66]. The proventriculus responded significantly to the increased amount of TDF and IDF in the diet, which reduced its weight, while the increased amount of SDF caused its weight to increase. Abdel-Daim et al. [

67] emphasize that medium amount of fibre in the diet affect HCl secretion, which seems to explain the increase in the weight of the proventriculus. In addition, IDF stimulates the proventriculus to secrete more HCl, thanks to which it acts in combination with the gizzard as a barrier to pathogenic bacteria by lowering the pH, but also affects enzymatic activity and digestibility of nutrients [

61]. Changes in the weight of the gizzard were mainly generated by the share of oat hull, it allowed for compensation of the birds’ growth after the change of diet on the day 7 of the birds’ life. Dixon et al. [

68] observed a lack of correlation between the weight of the gizzard and other organs, the increase in the amount of OH in the diet was accompanied by an increase in its weight, while interestingly,

ad libitum feeding did not cause significant differences in BW compared to chickens fed a diet with OH. Hikawczuk et al. [

54] observed an increase the weight of the gizzard with the increase the amount of OH in the diet, additionally, the use of this component and the IDF contained in it balanced the content of NSP in the diet based on 50% of barley grain, also affecting the weight of the gizzard at the level of 3% OH in the diet. The correlation analysis in the conducted experiment showed only an increase in its weight in the case of using a higher amount of TDF in the diet, without a significant effect of components in the form of IDF or SDF, which may also suggest that the proportion between the individual types of DF in the direction of the increase in the amount of IDF is of significant importance in the increase in its weight. To a lesser extent, with the share of SH, which to some extent explains the stability of the increase in BW throughout the rearing period compared to the control group of birds. Kimiaeitalab et al. [

63] in chickens on the day 21 of life found a significantly higher weight of the gizzard of chickens fed a diet with OH compared to the birds of the control group. SBP and WB did not have a significant effect on the increase in gizzard weight (p>0.05). However, in the study by Shang et al. [

65], a higher gizzard weight was shown on day 21 and 42 of rearing of broiler chickens fed a diet with WB compared to the control group, where the basic cereal component was maize. In the study by Gonzalez-Alvarado et al. [

62] when the basis of the diet was broken rice, the use of 3% SBP in the diet significantly increased (p<0.05) the gizzard weight, but on the other hand, comparing in the same experiment the use of a diet with 3% OH significantly increased the weight of the gizzard. Liver weight correlated positively with increased dietary IDF content and increased small intestine and caecal length in response to increased nutrient absorption from the jejunum and ileum and SCFA from the cecum, which was accompanied by increased heart weight.

Yokhana et al. [

69] found an increase in liver weight in layer-strain poultry when 1% insoluble fibre was added to the diet of the birds. In addition, Juanchich et al. [

60] in their studies also indicate that the jejunum is the main section of the intestines that responds first to the type of diet, which may consequently entail the development of subsequent sections and affect liver weight.

The increase in heart weight can be associated with an increase in blood flow rate and the work of the gizzard and absorption in the intestinal section, which compensate for the dilution of the diet with greater absorption of nutrients and more finely divided flowing content. However, there is little information on this subject in the available literature. Gonzalez-Ortiz et al. [

70] emphasize that application of xylanase enzyme in the diet of broiler chickens has no effect on changing heart weight. Wang et al. [

71] in a prospective cohort study in the case of humans related presence of DF with lowering of LDL cholesterol level, but there is no possibility of comparison in the case of even a larger group of patients using regression analysis for obvious bioethical reasons of changes in weight of heart as a result of increasing amount of DF in the diet. The study conducted in the case of chickens may indicate that DF in the form of IDF affects the increase in heart weight, although more studies had to be conducted in this case. Correlation analysis showed that heart weight decreased in response to increased SDF in the diet, while it increased in the case of increased ileum length and liver weight. However, when comparing heart weight, it was the diet associated with SH that influenced the lowest myocardial weight (9.9 g), while slightly heavier hearts were found in the case of the WB diet (10.1 g). The highest weight was obtained with the OH diet (12.3 g), but the value was not significantly different from chickens fed the control diet and the diet containing SBP. Saadatmand et al. (2019) also observed in their study a significantly higher (p<0.05) heart weight when an insoluble fibre in the form of 3% rice husk with 110% of threonine requirement was used compared to 3% and 110% of threonine requirement.

3.5. Morphometric Analysis of Intestinal Sections and Their Correlation with Dietary Fibre in the Diet

The use of OH at a level of 3% significantly shortened (p<0.05) the length of the duodenum in chickens receiving this diet, compared to chickens fed the control diet. The opposite is the case with SH, the duodenum is elongated, while the lengths of the jejunum and ileum are shortened, a trend in shortening the jejunum (p=0.09) and shortening is observed in the case of the use of SBP (p<0.05). Correlation analysis did not indicate a significant relationship (p<0.05) between the length of the duodenum and the remaining variables related to the type of DF and the measurements of the digestive tract. This corresponds to the results obtained by Scholey et al. [

72] who found no difference (p>0.05) in duodenum length even when OH constituted 9% of the diet in measurements from 21 and 35 days of broiler chickens’ life, which also emphasizes the role of the gizzard in precise grinding of the digesta. Additionally, Jangiaghdam et al. [

73] in chickens fed diet where main cereal was maize addition of SH or soybean hull have no significant effect on the length of duodenum. Saadatmand et al. [

74] also found no significant changes in duodenum length compared to the control group in the case of SBP and rice hull. The control group and the group receiving OH were accompanied by elongation of the jejunum and ileum, the use of components rich in SDF caused shortening of the jejunum and large intestine, which suggests the presence of compounds easily absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, especially in the case of SBP. Sadeghi et al. [

21] reported a significant increase in jejunum and ileum length as a result of the use of SBP in the chicken diet compared to the control group and the rice hull diet. Correlation analysis showed that the jejunum responded to the increase in dietary IDF by increasing its length, its growth also correlated with the growth of other intestinal segments and an increase in liver weight. The ileum lengthened when the diet was richer in IDF and shortened when the diet was richer in SDF. Increasing its length caused the length of other intestinal segments, which was also accompanied by an increase in liver and heart weight, suggesting a response of these organs to increased transport of nutrients through the portal vein. The cecum increased in length in response to the increase in the proportion of IDF in the diet. The increase in its length was accompanied by an increase in the length of the small intestine and liver weight. Similarly, Jimenez-Moreno et al. [

75] also indicate that a small addition of DF affects the morphology of the intestines of broiler chickens. Additionally, the large intestine responded to the type of fibre. SDF caused its shortening, while IDF caused its lengthening, and with the increase in its length, the length of the small intestine also positively correlated. Looking at the changes from the point of view of the overall hindgut, the longest intestine length was found in the control group, which suggests that in response to the increased content of NSP in the case of 50% wheat grain in the diet. The length of this part increased as a form of adaptation to the diet consumed. The addition of OH shortens the total length of the intestines due to the gizzard works similar as a mill, but in order to be able to absorb in the appropriate amount of nutrients, the digestive tract adapts by lengthening the small and large intestine. Similarly, de Souza Leite et al. [

76] found an increase in the length and weight of the intestinal section in response to the addition of lignin in the diet. The greatest shortening of the intestinal length occurred with the use of SBP, which indicates the presence of easily soluble carbohydrates. Wróblewska et al. [

14] found a significant reduction (p<0.05) in total intestinal length following the use of triticale at 30% of the diet compared to a diet based on barley grain.

3.6. Experimental Model Based on Morphometric Measurements and Dietary Fibre Content

In the experiment conducted during the modelling of multiple regression equations, the effect of soluble and insoluble DF and their interaction in the form of TDF on the weight or length of organs or sections of the digestive tract and related to the digestive tract in the 35 day of life of broiler chickens was taken into account. This was a time long enough to show significant differences in the case of variance analyses depending on the proportion of soluble and insoluble fibre in the diet of broiler chickens [

51]. Additionally Ginindza et al. [

77] comparing fast-growing Ross-308 and slow-growing Venda birds, found a higher nutrient intake in slow-growing native birds at the level of 5.7 - 5.8% of the diet. Modelling the entire process in this case takes into account data from all groups, taking into account the significance of the tested equation and its fit to the data obtained on the basis of the data obtained as a result of the previously planned experimental design.

The obtained equations also draw attention to the need to increase the amount of data or develop a method to even better equalize the data in replications at the beginning of the experiment. However, despite the availability of such data, the effect of DF use, including different shares of additional cellulose or lignocellulose in the diet on changes and the possibility of fitting them to the multiple regression equation in the case of the small intestine, cecum and changes in liver weight, is outlined. Rybicka et al. [

78] noted a shortening of the small intestine length (p<0.05) in chickens fed almond shell, compared to groups receiving lignocellulose or more or less crushed straw. On the other hand, [

21] noted an increase in liver weight when rice husk and SBP were added to the animals’ diet, compared to SBP alone, but did not find any significant differences in heart weight between treatments (control, RH, SBP and RH/SBP). There was no significant effect of the independent variables analysed in the experiment on the weight of the glandular and muscular stomachs and the length of the duodenum (p>0.05), which suggests that taking into account all groups and preparing the model does not have a quantitative effect in the final summation on the values of these parameters. Changes in the jejunum were significantly associated with the change in the length of the large intestine and liver weight in birds. On the other hand, the model based on all components also showed the effect of all variables analysed together on the significance of the constructed regression equation (p<0.05) for its better fit to the data, similarly to subsequent sections in the form of the ileum and cecum. The significance of the effect of independent variables on the dependent variable was also indicated in the case of liver weight, among all the components of the equation, changes in the length of the jejunum were significant. In turn, Oliveira et al. [

79] noted a significant reduction in the weight of proventriculus and gizzard as a result of the use of SDF compared to insoluble fibre at 35 days of age of broiler chickens. The use of soluble fibre by the researchers significantly increased the length of the small and large intestine.

In summary of this subsection, it can be stated that DF affects differences in model changes in the lower part of the digestive tract, but does not have a significant effect in the experiment used on significant changes in values in the upper section. An interesting element for the future could be to check the changes in the modelling of regression equations in the case of using one component, e.g., OH on changes in the digestive tract of chickens, also taking into account individual weeks of the birds’ life.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Diets

The experiment on broiler chickens was approved by the Faculty Team for Animal Welfare of the Faculty of Biology and Animal Nutrition at the University of Life Sciences in Wrocław no. 0058 in Register of Users of animals used in procedures according with ordinance described in article no.3 of Dz.U.2021 position 1331, 2338 on the protection of animals used for scientific and educational purposes. In experiment 150 broiler chickens were kept in 30 metabolic cages useful during digestibility trial. Design of experiment assumed use of a single experimental factor in form of additional source of DF in diets of 5 treatments. Each treatment consisted of 6 replications of 5 chicks each (n=30 in each treatment). Similar average of BW was taking into consideration and checked on the beginning of experiment what allows to observe changes between treatments during experiment caused by different variants of experimental factor. Diets was differentiated by the addition of structural components in the amount of 3% of structural additives (OH, SH, SBP and WB), except for the control group where standard diet contained maize and soybean meal was used. Vaccinated, one-day-old Ross 308 chickens with an average body weight of 44.8 g were kept together for the first 7 days of life and fed a starter mixture based on wheat grain and soybean extraction meal (

Table 5).

At 7 days of age, chicks weighing approximately 133 g were randomly assigned to five treatments. The birds continued to be fed starter-type diet until 21 days of age. From 21 to 35 days of age, the chicks received a grower mix with the same type and share of structural components as in the starter mixes (

Table 6). The chicks were kept under standard rearing conditions. The temperature on the first day of the experiment was 32°C, then it was systematically lowered to 24°C in the second week of the experiment and 20°C in the last days of the chicks’ life. The lighting program included 23 hours of light and 1 hour of darkness in the first few days; after the day 7 the length of the light day was shortened to 20 hours, while from the day 14to the day 35 the length of the light day was 18 hours. The diets were offered to the chickens

ad libitum, taking into account uneaten food during the recording of feed intake. Water was provided to the chickens using nipple drinkers. Body weight, feed intake and feed conversion ration were recorded on the days 21 and 35 day. Humidity in the room was maintained in the range of 55-60% and was reduced with the age of the birds.

4.2. Chemical Analysis

Chemical analysis at the initial stage was performed to select the appropriate amount of components in individual diets within the framework of the birds’ demand for nutrients in order to determine the chemical composition of individual diets. Then it was also performed for individual diets prepared before the start of rearing. Metabolizable energy (ME) for each component of diet was calculated on the basis equations present in the European Tables of Energy Values for Poultry [

80]. After evaluation of ME in components diets was prepared in terms of level of metabolizable energy, nutrients and minerals using The Polish Requirements of Poultry Nutrition [

81]. In nutrition starter and grower diets was used. First starter diet was used to 20th day of life of chickens. In each treatment diet per 1 kg of feed 12.5 MJ ME/kg and about 220 g/kg of crude protein (

Table 5). Second grower diet was given to chickens from 21 to 35 days of life (

Table 6). The use of the mixtures was deliberately changed over time to also check whether the additional source of DF would significantly affect the growth of the birds, or whether it would have no significant effect and would affect the health of the birds.

The chemical composition of individual components and diets was determined using the Official Methods of Analysis (AOAC) [

82]. During the analysis following constituents were determined Dry matter (DM, AOAC; 934.01); crude protein (CP, Kjeldahl method, AOAC 984.13); crude ash (CA, AOAC 942.05), ether extract (EE, Soxhlet method, AOAC, 920.39A), crude fibre (CF, Hennenberg and Stohmann method, AOAC 978.10). On the other hand, the contents of TDF, IDF and SDF in the feed components were determined as the average value from the studies [

15,

25,

83,

84]. Then, the fibre fraction content in ingredients was used to calculated total content for individual diets (

Figure 2).

4.3. Length and Weight Measurements

On day 35, 90 birds from each feeding group were sacrificed for the purpose of measuring the weight or length of selected sections of the digestive tract. Birds were sacrificed by concussion following a truncheon strike and a rapid sublingual incision for the bleeding of birds. Then, the gastrointestinal tract of birds was prepared and food content was removed from sections of intestines, proventriculus and gizzard. In the next stage of the procedure, measurements were taken of the length of selected sections of intestines (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, large intestine) and the weight of selected organs (proventriculus, gizzard, heart and liver).

4.4. Statistical Analysis

For statistical verification, the obtained results were analysed in Statistica 13.3 (Tibco Software Inc., Palo Alto, USA, 2017) using the one-way analysis of variance test. Following model of one-way ANOVA was used:

where constituents of equation means:

yij—value of observed dependent variable

µ—general mean in population (effect of common factors)

αi—effect of structural component

εij—effect of random factors

The significance of differences was determined at two levels of significance: p<0.05 and p<0.01. Tukey’s HSD test was used to determine differences between mean values. The normality of data distribution in the experimental groups was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, while the homogeneity of variance between groups was tested using Leven’s test.

Covariance analysis was used for measuring the length of intestinal segments and the weight of selected organs; no significant difference was found in the body weight of birds during dissection.

The Spearman correlation test was used to determine the correlation between fibre types and selected intestinal lengths or the weight of selected organs; the null hypothesis was verified at the significance level of p<0.05.

The components of the multiple regression equation were calculated using the least squares method, the significance of individual variable coefficients was verified based on the student’s t-test, while the significance of the equation describing the effect of independent variables on the tested dependent variable was verified using the F test. The verification of hypotheses using both tests was performed at the significance level of p<0.05, with the simultaneous determination of the R

2 coefficient of fit of the data to the equation. Following equation was used:

where constituents of equation means:

Y – dependent variable

x – independent variable

β0 – intercept

β1, β2, …, βk – coefficients

ε – error term

5. Conclusions

In the conducted experiment, individual diets containing SBP and WB resulted in lower BW and FCR. OH, when changed from the control diet used in the first seven days, was able to compensate for the lower availability of ingredients and influence the differentiation of the digestive tract sections and production results that did not differ significantly from the control diet on the 35th day of life. Modelling the process of digestive tract development of different diets indicates a lack of significant influence of independent variables on the upper part of gastrointestinal tract. Significant changes under the influence of different sources of DF were found in the intestinal section and the metabolically related liver. In the case of multiple regression analysis, no significant effect was found on the heart weight of chickens. Further studies are required to more precisely determine the influence of soluble and insoluble fibre on changes in the digestive tract of chickens. An interesting future project would be to investigate the effect of additives being a source of insoluble and soluble fibre in the chicken diet in separate experiments, or using individual ingredients being their sources constituting 0, 25, 50, 75 and 100% of the TDF additive.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H. and A.S.-T.; methodology, T.H.; software, A.Z., A.R. and K.L.-S.; validation, T.H., P.W.; formal analysis, T.H., K.L.-S.; investigation, P.W. and A.S.-T.; resources, T.H.; data curation, T.H., A.Z. and A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, T.H, P.W. and A.S.-T.; writing—review and editing, P.W., A.R and A.S.-T.; visualization, T.H, A.Z. and A.R.; supervision, A.S.-T. and K.L.-S.; project administration, T.H.; funding acquisition, T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded from internal grant from the Faculty of Biology and Animal Breeding, Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences: B/030/0068/16

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arcuri, S.; Pennarossa, G.; Pasquariello, R.; Prasadani, M.; Gandolfi, F.; Brevini, T.A.L. Generation of porcine and rainbow trout 3D intestinal models and their use to investigate astaxanthin effects in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.J.; Chang, Y.; Song, J. The pig as an optimal animal for cardiovascular research. Lab. Anim. 2024, 53, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Shujaat, S.; Braem, A.; Politis, C.; Jacobs, R. 3D-printed porous Ti6Al4V scaffolds for long bone repair in animal models: a systematic review. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2022, 17, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, P.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, D.; Nandi, S.K. Role of animal models in biomedical research: a review. Lab. Anim. Res. 2022, 38, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Santin, J.; Burggren, W.W. Beyond the chicken: Alternative avian models for developmental physiological research. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 712633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhang, M.; Feng, J. Gut microbiota alleviates intestinal injury induced by extended exposure to light inhibiting the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in broiler chickens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregaskes, C.A.; Kaufman, J. Chickens as a simple system for scientific discovery: The example of the MHC. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 135, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula Reis, M.; Sakomura, N.K.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A.; Da Silva, E.P.; Kebreab, E. Partitioning the efficiency of utilization of amino acids in growing broilers: Multiple linear regression and multivariate approaches. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hao, E.; Chen, X.; Huang, C.; Lin, G.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Shi, L.; Xuan, F.; Cheng, D.; et al. Dietary fiber level improve growth performance, nutrient digestibility, immune and intestinal morphology of broilers from day 22 to 42. Animals 2023, 13, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, N.A.; Desai, D.N.; Avari, P.E.; Ranade, A.S. Use of natural insoluble fiber in oat hulls (Avena sativa) as non-antibiotic growth promoter in broilers. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2020, 10, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, O.O.; Park, C.S.; Adeola, O. Nutritional potentials of atypical feed ingredients for broiler chickens and pigs. Animals 2021, 11, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamroz, D.; Jakobsen, K.; Bach Knudsen, K.E.; Wiliczkiewicz, A.; Orda, J. Digestibility and Energy value of non-starch polysaccharides in young chickens, ducks and geese, fed diets containing high amounts of barley. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002, 131, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, A.B.; Wandrag, D.B.R. Effect of different dietary fibre raw material sources on production and gut development in fast-growing broilers. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 54, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, P.; Hikawczuk, T.; Szuba-Trznadel, A.; Wiliczkiewicz, A.; Zinchuk, A.; Rusiecka, A.; Laszki-Szcząchor, K. Effect of triticale grain in diets on performance, development of gastrointestinal tract and microflora in crop and ileum of broiler chickens. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrocoso, J.D.; García-Ruiz, A.; Page, G.; Jaworski, N.W. The effect of added oat hulls or sugar beet pulp to diets containing rapidly or slowly digestible protein sources on broiler growth performance from 0 to 36 days of age. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 6859–6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Moreno, E.; Frikha, M.; de Coca-Sinova, A.; Lázaro, R.P.; Mateos, G.G. Oat hulls and sugar beet pulp in diets for broilers. 2. Effects on the development of the gastrointestinal tract and on the structure of the jejunal mucosa. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 2013, 182, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmad, G.S.; Lim, C.B.; Kim, I.H. Effect of dietary almond hull on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, organ weight, caecum microbial counts, and noxious gas emission in broilers. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2024, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, P.; Hikawczuk, T.; Sierżant, K.; Wiliczkiewicz, A.; Szuba-Trznadel, A. Effect of oat hull as a source of insoluble dietary fibre on changes in the microbial status of gastrointestinal tract in broiler chickens. Animals 2022, 12, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz-Aliabadi, F.; Hassanabadi, A.; Golian, A.; Zerehdaran, S. Optimisation of broilers performance to different dietary levels of fibre and different levels and sources of fat from 0 to 14 days of age. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asp, N.-G. Dietary fibre-definition, chemistry and analytical determination. Mol. Asp. Med. 1987, 9, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Toghyani, M.; Gheisari, A. Effect of various fiber types and choice feeding of fiber on performance, gut development, humoral immunity, and fiber preference in broiler chicks. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 2734–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.; Sakkas, P.; Kyriazakis, I. What are the limits to feed intake of broilers on bulky feeds? Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 100825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Itani, K.; Kaczmarek, S.; Smith, A.; Svihus, B. Influence of particle size and inclusion level of oat hulls on retention and passage in the anterior digestive tract of broilers. Brit. Poult. Sci. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewole, D.I.; Oladokun, S.; Santin, E. Effect of organic acids-essential oils blend and oat fiber combination on broiler chicken growth performance, blood parameters, and intestinal health. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röhe, I.; Zentek, J. Lignocellulose as an insoluble fiber source in poultry nutrition: a review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, T.; Tahir, M.; Naz, S.; Khan, R.U.; Alhidary, I.A.; Abdelrahman, S.H.; Selvaggi, M. Effect of soy hulls as alternative ingredient on growth performance, carcase quality, nutrients digestibility and intestinal histological features in broilers. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 23, 1336–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamedi, A.; Salari, S.; Baghban, F. Changes in performance, cecal microflora counts and intestinal histology of Japanese quails fed diets containing different fibre sources. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2024, 25, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.; Mishra, P. Dietary fiber in poultry nutrition and their effects on nutrient utilization, performance, gut health, and on the environment: a review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewole, D.; MacIsaac, J.; Fraser, G.; Rathgeber, B. Effect of oat hulls incorporated in the diet of fed as free choice on growth performance, carcass yield, gut morphology and digesta short chain fatty acids of broiler chickens. Suatainability 2020, 12, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, K.; Apajalahti, J.; Smith, A.; Ghimire, S.; Svihus, B. The effect of increasing the level of oat hulls, extent of grinding and their interaction on the performance, gizzard characteristics and gut health of broiler chickens fed oat-based pelleted diets. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 2024, 308, 115858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawash, M.A.; Farkas, V.; Such, N.; Mezőlaki, Á.; Menyhárt, L.; Pál, L.; Csitári, G.; Dublecz, K. Effects of barley- and oat-based diets on some gut parameters and microbiota composition of the small intestine and ceca of broiler chicken. Agriculture 2023, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz-Aliabadi, F.; Hassanabadi, A.; Zerehdaran, S.; Noruzi, H. Evaluation of the effect of different levels of fiber and fat on young broiler’s performance, pH, and viscosity of digesta using response surface methodology. Iran. J. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2023, 13, 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Adewole, D. Effect of dietary supplementation with coarse or extruded oat hulls on growth performance, blood biochemical parameters, ceca microbiota and short chain fatty acids in broiler chickens. Animals 2020, 10, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Burton, E.; Scholey, D.; Alkhtib, A.; Broadberry, S. Efficacy of oat hulls varying in particle size in mitigating performance deterioration in broilers fed low-density crude protein diets. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garçon, C.J.J.; Ellis, J.L.; Powell, C.D.; Navarro Villa, A.; Garcia Ruiz, A.I.; France, J.; de Vries, S. A dynamic model to measure retention of solid and liquid digesta fractions in chickens fed diets with differing fibre sources. Animal 2023, 17, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bila, L.; Tyasi, T.L.; Tongwane, T.W.N.; Mulaudzi, A.P. Correlation and path analysis of body weight and biometric traits of Ross 308 breed of broiler chickens. J. World Poult. Res. 2021, 11, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebong, U.N.; Sam, I.M.; Essien, C.A.; Okon, L.S. Estimation of carcass yield from morphometric traits of ROSS 308 strain of broiler chickens raised in humid zone of Nigeria. AJAFS, 2023, 7, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, S.Z.; Jiang, X.F.; Zhang, K.; Ma, G.W.; Wu, M.Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, H. Construction of multiple linear regression models using blood biomarkers for selecting against abdominal fat traits in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, M.; Dunislawska, A.; Stadnicka, K.; Grochowska, E. Chicken embryo as a model in epigenetic research. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachholz, G.E.; Rengel, B.D.; Vargesson, N.; Fraga, L.R. From the farm to the lab: How chicken embryos contribute to the field of teratology. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 666726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beacon, T.H.; Davie, J.R. The chicken model organism for epigenomic research. Genome 2021, 64, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Cheng, H.-W. The influence of cecal microbiota transplantation on chicken injurious behavior: Perspective in human neuropsychiatric research. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, W. Dietary fiber intake and gut microbiota in human health. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, O.; Feng, Q.-Q.; Ojo, O.O.; Wang, X.-H. The role of dietary fibre in modulating gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niekamp, P.; Kim, C.H. Microbial metabolite dysbiosis and colorectal cancer. Gut Liver 2023, 17, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasuriya, S.S.; Park, I.; Lee, K.; Lee, Y.; Kim, W.H.; Nam, H.; Lillehoj, H.S. Role of physiology, immunity, microbiota and infectious diseases in the gut health of poultry. Vaccines 2022, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehata, A.A.; Yalçin, S.; Latorre, J.D.; Basiouni, S.; Attia, Y.A.; El-Wahab, A.A.; Visscher, C.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Huber, C.; Hafez, H.M.; et al. Probiotics, prebiotics, and phytogenic substances for optimizing gut health in poultry. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Zhang, L.; Lin, H.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X. Bacillus subtilis M6 improves intestinal barrier, antioxidant capacity and gut microbial composition in AA broiler. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 965310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denbow, D.M. Chapter 14 – Gastrointestinal Anatomy and Physiology. In Sturkie’s Avian Physiology, 6th ed.; Academic Press, 2015; pp. 337–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, R.A.; Hanotte, O. Domestic chicken diversity: origin, distribution, and adaptation. Anim. Genet. 2021, 52, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejeda, O.J.; Kim, W.K. Role of dietary fiber in poultry nutrition. Animals 2021, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Emous, R.A.; Mens, A.J.W.; Winkel, A. Effects of diet density and feeding frequency during the rearing period on broiler breeder performance. Brit. Poult. Sci. 2021, 62, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhe, I.; Vahjen, W.; Metzger, F.; Zentek, J. Effect of a “diluted” diet containing 10% lignocellulose on the gastrointestinal tract, intestinal microbiota, and excreta characteristics of dual purpose laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikawczuk, T.; Szuba-Trznadel, A.; Wróblewska, P.; Wiliczkiewicz, A. Oat hull as a source of lignin-cellulose complex in diets containing wheat or barley and its effect on performance and morphometric measurements of gastrointestinal tract in broiler chickens. Agriculture 2023, 13, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, G.A.G.; Mantovan, J.; Marim, B.M.; Kishimea, J.O.F.; Mali, S. Surface modification of cellulose from oat hull with citric acid using ultrasonication and reactive extrusion assisted processes. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gómez, S.; Yáñez, R.; Alonso, J.L. A new strategy for a separate manufacture arabinooligosaccharides and oligogalacturonides by hydrothermal treatment of sugar beet pulp. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2024, 17, 4711–4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukema, M.; Faas, M.M.; de Vos, P. The effects of different dietary fiber pectin structures on the gastrointestinal immune barrier: impact via gut microbiota and direct effects on immune cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1364–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Bhuiyan, M.M.; Hopcraft, R. Non-starch polysaccharide degradation in the gastrointestinal tract of broiler chickens fed commercial-type diets supplemented with either a single dose of xylanase, a double dose of xylanase, or a cocktail of non-starch polysaccharide-degrading enzymes. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.T. Sources and levels of copper affect liver copper profile, intestinal morphology and cecal microbiota population of broiler chickens fed wheat-soybean meal diets. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanchich, A.; Urvoix, S.; Hennequet-Antier, C.; Narcy, A.; Mignon-Grasteau, S. Phenotypic timeline of gastrointestinal tract development in broilers divergently selected for digestive efficiency. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, A.; Qaisrani, S.N.; Khalique, A.; Hussain, J. Insoluble fiber source influences performance, nutrients digestibility, gut development and carcass traits of broilers. Pak. J. Agri. Sci. 2023, 60, 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- González-Alvarado, J.M.; Jiménez-Moreno, E.; González-Sánchez, D.; Lázaro, R.; Mateos, G.G. Effect of inclusion of oat hulls and sugar beet pulp in the diet on productive performance and digestive traits of broilers from 1 to 42 days of age. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 2010, 162, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimiaeitalab, M.V.; Cámara, L.; Mirzaie-Goudarzi, S.; Jiménez-Moreno, E.; Mateos, G.G. Effects of the inclusion of sunflower hulls in the diet on growth performance and digestive tract traits of broilers and pullets fed a broiler diet from zero to 21 d of age. A comparative study. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakhki, R.A.M.; Navarro-Villa, A.; de los Mozos, J.; de Vries, S.; García-Ruiz, A.I. Evaluation of fibrous feed ingredients alternatives to oat hulls as a source of feed structure in broiler diets. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.; Wu, D.; Liu, H.; Manfuz, S.; Piao, X. The impact of wheat bran on the morphology and physiology of the gastrointestinal tract in broiler chickens. Animals 2020, 10, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetland, H.; Svihus, B.; Krogdahl, Å. Effects of oat hulls and wood shavings on digestion in broilers and layers fed diets based on whole or ground wheat. Brit. Poult. Sci. 2003, 44, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Daim, A.S.A.; Tawfeek, S.S.; El-Nahas, E.S.; Hassan, A.H.A.; Youssef, I.M.I. Effect of feeding potato peels and sugar beet pulp with or without enzyme on nutrient digestibility, intestinal morphology, and meat quality of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. J. 2020, 8, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, L.M.; Brocklehurst, S.; Hills, J.; Foister, S.; Wilson, P.W.; Reid, A.M.A.; Caughey, S.; Sandilands, V.; Boswell, T.; Dunn, I.C.; et al. Dilution of broiler breeder diets with oat hulls prolongs feeding but does not affect central control of appetite. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokhana, J.S.; Parkinson, G.; Frankel, T.L. Effect of insoluble fiber supplementation applied of different ages on digestive organ weight and digestive enzymes of layer-strain poultry. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ortiz, G.; Sola-Oriol, D.; Martinez-Mora, M.; Perez, J.F.; Bedford, M.R. Response of broiler chickens fed wheat-based diets to xylanase supplementation. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 2776–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Y.-M.; Sea, M.M.-M.; Ng, K.; Wang, M.; Chan, I.H.-S.; Lam, C.W.-K.; Sanderson, J.E.; Woo, J. Dietary fiber intake, myocardial injury, and major adverse cardiovascular events among end-stage kidney disease patients: a prospective cohort study. Kidney Int. Rep. 2019, 4, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholey, D.V.; Marshall, A.; Cowan, A.A. Evaluation of oats with varying hull inclusion in broiler diets up to 35 days. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 2566–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangiaghdam, S.; Mirzaie Goudarzi, S.; Saki, A.A.; Zamani, P. Growth performance, nutrient digestibility, gastrointestinal tract traits in response to dietary fiber sources in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. J. 2022, 10, 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Saadatmand, N.; Toghyani, M.; Gheisari, A. Effects of dietary fiber and threonine on performance, intestinal morphology and immune responses in broiler chickens. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 5, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Moreno, E.; Frikha, M.; de Coca-Sinova, A.; Lázaro, R.P.; Mateos, G.G. Oat hulls and sugar beet pulp in diets for broilers. 2. Effects on the development of the gastrointestinal tract and on the structure of the jejunal mucosa. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 2013, 182, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Leite, B.G.; Granghelli, C.A.; de Arruda Roque, F.; Bueno Carvalho, R.S.; Scapin Lopes, M.H.; Pelissari, P.H.; Tuckmantel Dias, M.; da Silva Araújo, C.S.; Araújo, L.F. Evaluation of dietary lignin on broiler performance, nutrient digestibility, cholesterol and triglycerides concentrations, gut morphometry, and lipid oxidation. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginindza, M.; Mbatha, K.R.; Ng’ambi, J. Dietary crude fiber levels for optimal productivity of male Ross 308 broiler and Venda chickens aged 1 to 42 days. Animals 2022, 12, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybicka, A.; del Pozo, R.; Carro, D.; García, J. Effect of type of fiber and its physiochemical properties on performance, digestive transit time and cecal fermentation in broilers from 1 to 23d of age. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, N.R.; Santos, F.R.; Sousa Silva, M.R.; Rissato, I.S.; Roque, G.C.; Silva, C.M.; Barros, H.S.S.; Silva, N.F.; Minafra, C.S.; Araújn Neto, F.R. Dietary levels of soluble and insoluble fibre sources for young slow-growing broilers. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 69, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World’s Poultry Science Association, Nutrition of the European Federation of Branches Subcommittee Energy of the Working Group (Beekbergen). European Tables of Energy Values of Feeds for Poultry, 3rd ed.; WPSA: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1989; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Smulikowska, S.; Rutkowski, A. Polish Requirements of Poultry Nutrition, 4th ed.; Instytut Fizjologii i Żywienia Zwierząt, PAN: Jabłonna, Poland, 2005. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 19th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boazar, E.; Salari, S.; Erfanimejd, N.; Fakhur, K.M. Effect of mash and pellet diets containing different sources of fiber on growth performance and cecal microbial population of broiler chickens. J. Livest. Sci. Technol. 2021, 9, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hikawczuk, T. Effect of non-starch polysaccharides of cereal grains on physiological parameters of crop and ileum, and digestibility of nutrients in broiler chicken. Ph.D. Thesis, Wroclaw, 2013. (In Polish). Available online: https://www.dbc.wroc.pl/dlibra/publication/24396/edition/21350#description.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).