1. Introduction

The micro-structure of a food is the complex organization and interaction of the components of a foodstuff, which results in visible and separate subdivisions of the different components at the microscopic level. In addition, the morphology of a food may include, in addition to the chemical and structural arrangement of its components, the relationships between each molecule within a microstructural network [

1]. Food is intended to provide pleasure by offering appetizing tastes, attractive smells and pleasurable textures, as well as vital nutrients and energy. In addition, consumers are looking for products with additional features such as longer shelf life, increased nutritional value and clear packaging. The development and production of nutritious food with adapted characteristics to meet specific consumer needs is a new paradigm in food science. Scientists and food producers use a variety of strategies to accomplish this objective, putting a primary emphasis on understanding and managing food structures, especially at the level of the microscopic. Three fundamental components of food micro-structure research are visualization, identification, and quantification; every one requires unique instruments and methods to provide significant understanding into the complicated structure of food components [

2].

According to Suresh and Samsher [

3] and others, functional attributes are the fundamental physico-chemical characteristics of foods that represent the intricate relationships among the compositions, physicochemical characteristics, and molecular configuration of food elements and the environment and circumstances whereby these are determined and correlated. In addition to demonstrating the potential that they can be effectively utilized to promote or substitute traditional protein, lipids, sugars (starch and sugars), and fiber, their functional properties are necessary to potentially aid in the prediction and accurate assessment regarding how novel lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins (starch and sugars) can function in particular food chains [

4]. Moreover, functional characteristics clarify how various components behave throughout heating and processing and additionally how their properties impact the final food items’ appearance, texture, and flavor. Swelling capacity, water uptake capacity, absorption of oil capacity, emulsion operation, consistency of emulsion, foam capacity, consistency of foam, gelatinization, bulk density, dextrinization, preservation, denaturation, coagulation, gluten formation, jelly, shortening, plasticity, flakiness, moisture retention, aeration, and sensory attributes are a few examples of functional properties. A food’s structure, quality, texture, nutritional value, acceptability, and (or) appearance all define its functional properties. A food’s organoleptic, physical, and/or chemical characteristics frequently dictate its functional characteristics [

5].

Alginate is a naturally occurring poly-anionic polymer that is biodegradable, non-toxic, and non-immunogenic. Alginates have many uses, such as wrapping fresh and cut vegetables and fruits, protecting food, thickening, gelling, emulsifying, and stabilizing food items like ice cream, sauces, and fruit pies, and delivering drugs for anti-reflux preparations. Alginate possesses anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant qualities. It dissolves progressively in the intestinal tract under alkalinity circumstances and remains stable in the stomach’s acidic gastric solution. Alginate is used in tumor therapy as part of the logical medication design for chemotherapy. Alginates are very helpful in restructuring foodstuffs that could oxidize or be destroyed by excessive heat because they form gels at low temperatures (e.g., meat products, fruits and vegetables) [

6]. Adequate sodium alginate (ALG) treatment encourages the structural change of succinylated glutenins and improves the complexes’ functional characteristics, such as improved water and oil holding capacity, thermal stability, emulsification, and foam stability [

7]. Alginate is frequently utilized in the beverage and food companies due to its thickening, gelling, and film-forming qualities, making it a crucial component. Alginate still needs to contend with various food hydrocolloids of comparable importance in this extremely competitive marketplace, such as marine hydrocolloids like agar and carrageenan, derivatives of cellulose like methyl cellulose and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), and plant gums like guar and locust bean [

8]. This review offers a summary that is primarily concerned with the usage of alginates in foodstuff. It was attempted to understand and address the latest studies that have recently been done on the application of alginate in the food company. Additionaly, understanding of alginate’s uses has advanced significantly, optimizing its use in food systems remains difficult due to the intricate interactions between its molecular structure, interactions within various food matrices, and processing conditions. In order to fully realize alginate’s potential in food technology, this review will critically analyze the current understanding of how alginate affects food microstructure and functional qualities, highlighting recent developments in alginate extraction and application in food industry and pointing out areas that require more study.

2. Materials and Methods

Finding relevant papers required a careful search of electronic databases, such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Among the search terms used were “food polymer,” “polysaccharides,” “alginate,” “health benefits,” “extraction method of alginate,” and “potential use of alginate in food industry.” Articles, reviews, and meta-analyses concentrating on the physiological effects as functional food, conventional method of extraction, and non-conventional method of extraction of alginate were the focus of this search approach. The only papers taken into consideration were those published in peer-reviewed publications and written in English. The publishing date was not restricted in order to cover a broad spectrum of research findings but more focused on recent publications (2010–2024) and experimental works published in the last 5 years,. More than 142 articles were found; however, we selected only 63 that contained all the information for the present study. In order to find pertinent information, a two-stage screening procedure was used. First, publications were found by searching for them using tools like Google Scholar, PudMed, and Science Direct, then their titles and abstracts were examined. Full-text analysis was then carried out in the second stage to make sure they satisfied all selection requirements. An overview of the physiological effects as functional food, possible use in food industry, and techniques of extraction of alginate both conventional and novel from seaweed extracts was provided by the synthesis of this data. Tables, graphics, and narrative synthesis were used where appropriate to summarize quantitative data. In order to guide future research and clinical applications, as well as to offer insights into the existing understanding of alginates, the synthesis findings are presented.

3. Sources and Structure of Alginate

Alginates are extensively utilized in many different sectors. They help preserve moisture, which enhances the texture of baked goods, guarantee a smooth texture and even dewatering of frozen foods, and offer dairy products and canned food consistency and a suitable appearance. Stabilizing beer foam is one of their more common uses. In order to improve the quality of functional food among commercial items, the food industry is currently using creative methods and efficient food additives due to the general worries about nutrition and wellness. To improve physicochemical qualities like flavor, taste, and texture, a variety of bioactive compounds have been developed. To suit the requirements of people around the world, the food sector employs a lot of ingredients nowadays. Alginate, one of the polysaccharides, has several uses in the food industry and in medicine, including medication administration [

9].

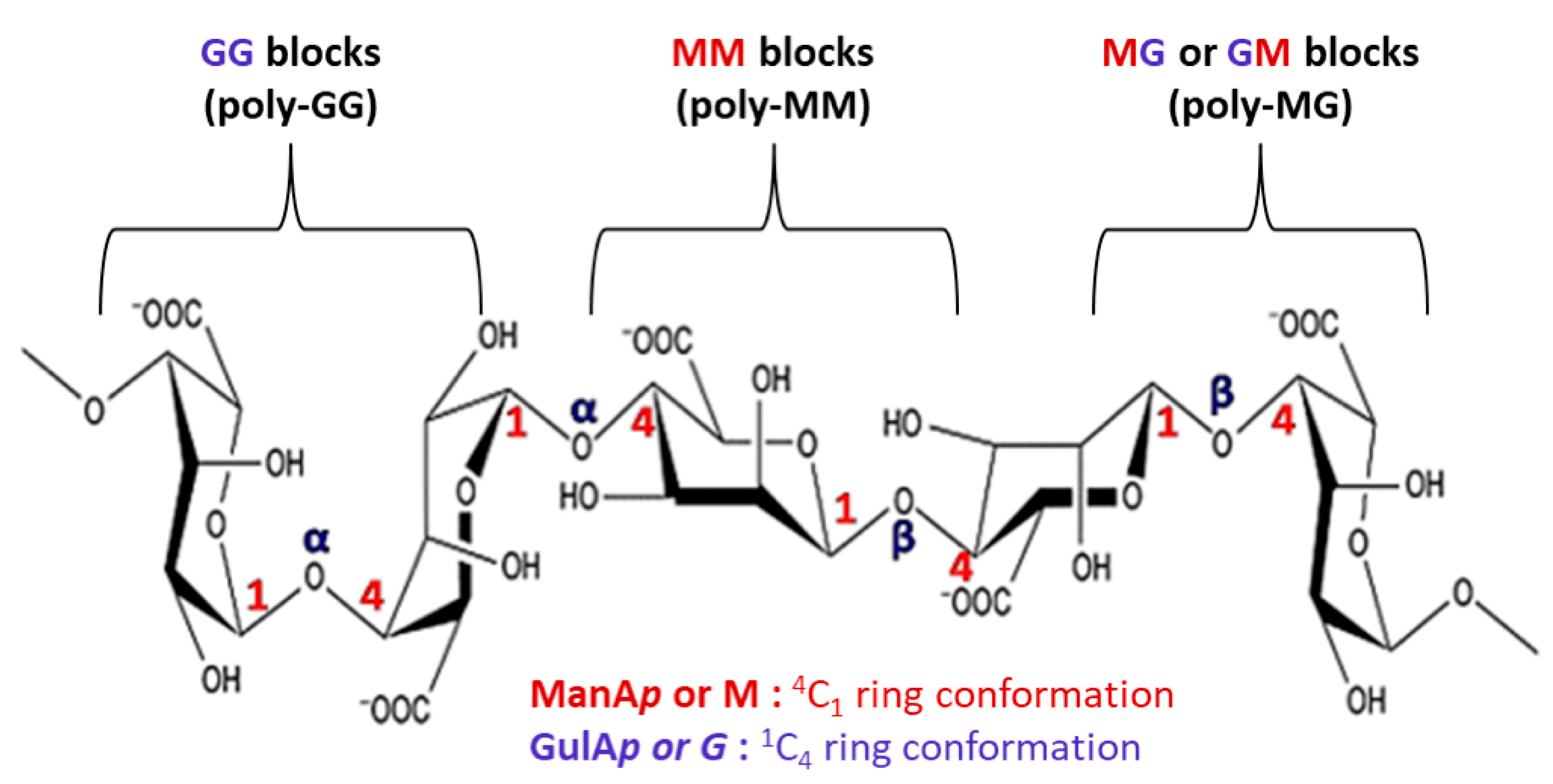

Alkaline extraction conditions purify the cell walls of brown algae found in marine environments, which are then used to generate alginate. Alginates consist of α-L-guluronic acid (G) that is 1→4-linked and β-D-mannuronic acid (M) pyranose that is still in a straight chain. The G blocks of this molecule are crucial because they allow the calcium and hydrogen ions to form gels at low temperatures by generating a distinctive “egg-box” shape. Additionally, the MG blocks aids in lowering the viscosity of the solution [

10]. It is organized with different ratios of GG, MG, and MM blocks in an uneven block-wise arrangement. The length of each block and the M/G ratio has a significant impact on the physicochemical characteristics of alginate. Whereas the GG blocks have α-1,4-glycosidic bonds, which introduce space steric barrier around the carboxyl, the MM blocks form a β-1,4-glycosidic link, giving the M block section a linear flexible structure. Because of this, the G-block segment offers a rigid and folded structural shape, which gives the molecular chain its notable rigidity (

Figure 1). Water-soluble alkali metal salts are generally referred to as alginate [

11]. A significant component of the cell walls of brown algae, primarily sargassum and kelp, is alginate. It consumes over 40% of the algae’s dry weight. Due of its limited solubility in water and high solubility in alkaline solutions, alginate is primarily removed. Alginate is dissolved from the algal cell wall using a sodium carbonate solution, and it is subsequently precipitated out by adjusting the pH with acid.

Laminaria hyperborean, Macrocystis pyrifera, Laminaria digitata, Ascophyllum nodosum, Sargassum spp.

, Laminaria japonica, Ecklonia maxima, and Lessonia nigrescens are the primary algae species utilized for alginate extraction [

12].

It has been demonstrated that the bacterial genera

Pseudomonas and

Azotobacter secrete alginate. The opportunistic human pathogen

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the soil-dwelling

Azotobacter vinelandii have been the subjects of the majority of studies on the molecular mechanisms underlying bacterial alginate production. In nature, these two genera secrete alginate for distinct reasons with distinct material qualities, but using very similar molecular pathways to create it: While

Azotobacter produces a stiffer alginate (usually with higher concentrations of G residues) that stays closely associated with the cell and enables the formation of desiccation-resistant cysts, some

P. aeruginosa strains (also known as

mucoid strains) can secrete copious amounts of alginate to aid in the formation of thick, highly structured biofilms [

14].

Zahira B. et al. [

15] found that the alginate yields of eight brown algal species collected from the Northwestern Atlantic coast of Morocco ranged from 2.7% to 27.5% dw in their study “Isolation and FTIR-ATR and H NMR Characterization of Alginates from the Main Alginophyte Species of the Atlantic Coast of Morocco”.

Laminaria ochroleuca had the largest percentage of alginates, while

Bifurcaria bifurcata had the lowest alginate concentration. The yield of alginates in

S. muticum, C. tamariscifolia, C. humilis, and

F. vesiculosus was more than 18% dw. Some well-known alginophytes from around the world have been reported to have contents similar to these [

15].

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

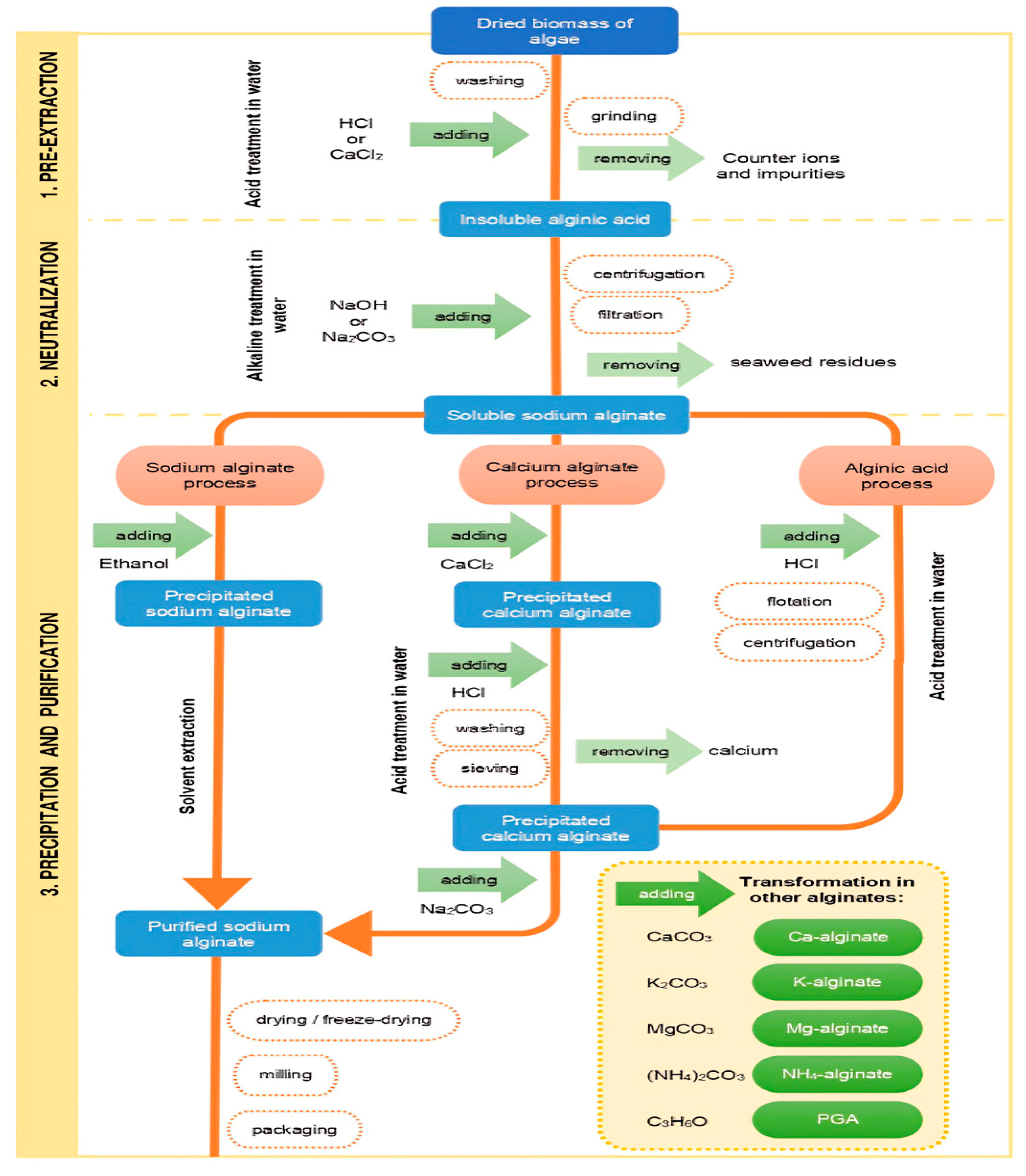

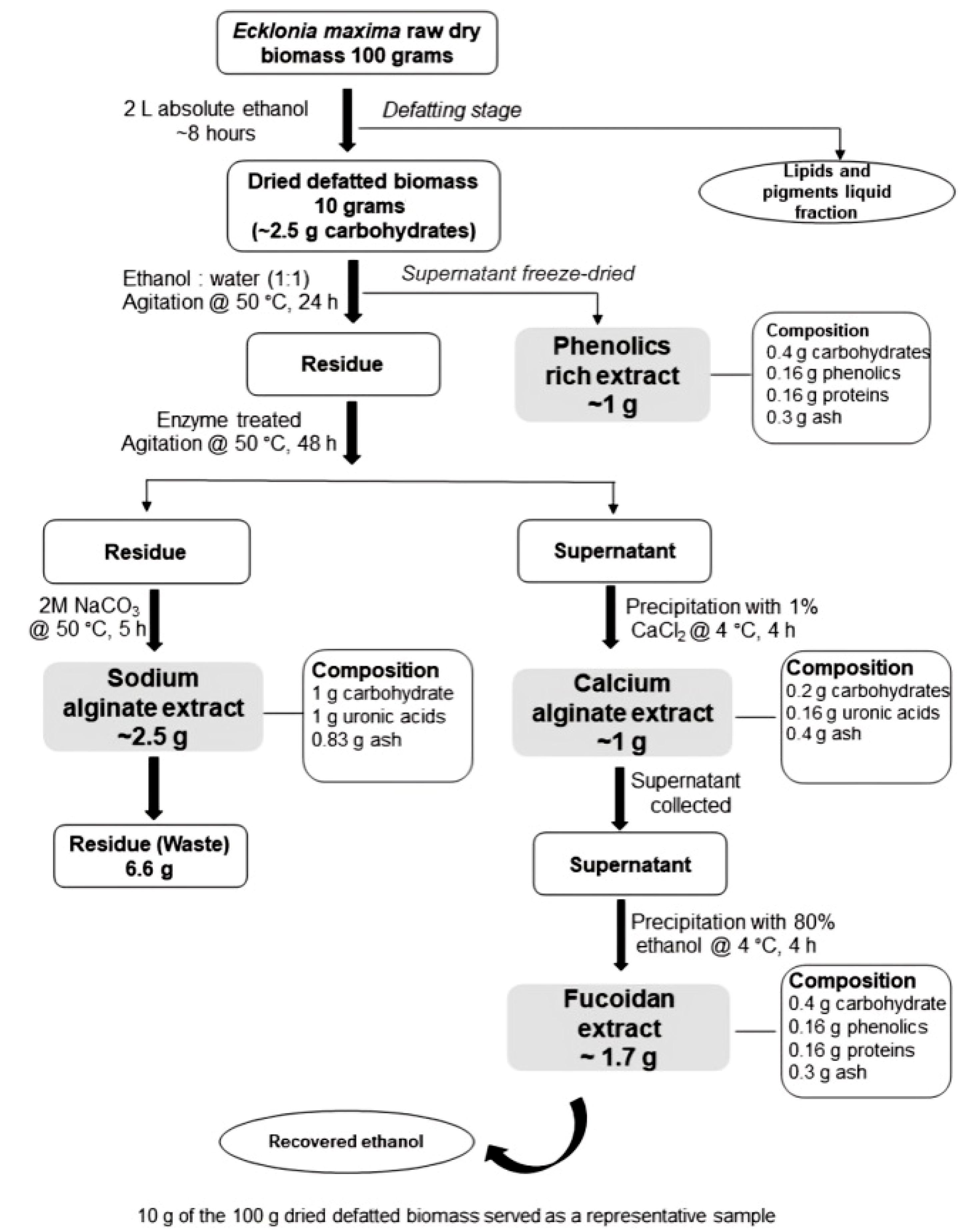

4. Alginate Production Process: A Conventional Approach

Alginate is extracted from seaweed using a multi-step procedure. In short, the first steps involve washing, drying, and grinding raw seaweed into a fine powder. After soaking the seaweed biomass in water to regain its moisture it, several chemicals are then introduced to the seaweed to eliminate undesirable components. After breaking down the algae cell wall with an acid or alkali pre-treatment, sodium carbonate is extracted to remove water-soluble alginate from the seaweed biomass structure. Alginate can be recovered from the solution using one of three precipitation routes: sodium alginate, calcium alginate, or alginic acid. Sodium alginate is often the final product that is isolated (

Figure 2) [

16].

In their study on the extraction of alginate from brown seaweed, Danya G. et al. [

17] discovered that the alginate content of the various species was greater than 16% dw in the investigated area. Species, exhibiting an intriguing dietary fiber content as a nutraceutical food source, with the exception of

H. cuneiformis, which had the lowest average (13.3%). The extracted alginates of the chosen species and the reported commercial alginates from around the world were identical, according to physicochemical studies and spectroscopic methods (FTIR and NMR study). It is possible to draw the conclusion that the alginates that were extracted from

Turbinaria triquetra, Sargassum aquifolium, Dictyota dichotoma, Padina boergesenii, and

Hormophysa cuneiforms could be used as alginophyte industrial exploitation to produce mannuronic acid-enriched alginate, which is suggested to be used in food products and to create elastic gels. Furthermore, when compared to the international alginate regulation, the alginate extracted from the five chosen seaweeds also showed food-grade quality. Because of the variations in viscosity among the seaweeds examined, the food industry can take advantage of this recognition to use in a variety of processed products. To ascertain the alginate’s high molecular weight, the molecular weight must be evaluated prior to exploitation. Furthermore, the safe utilization of these seaweeds depends on the storage duration and potential variations in the alginate yield or characterization [

17].

Additionally, the work on the evaluation and characterization of alginate extracted from brown seaweed by Rashedy, S. et al. [

18] displays the sodium alginate yield of the five species under study, which were collected in the Red Sea. There were notable differences in the alginate content between the species. The alginate yield varied by 8.9% between the species, with

T. triquetra recording the greatest average (22.2 ± 0.56% dw) and

H. cuneiformis recording the lowest average (13.3 ± 0.52% dw) [

18].

Anak A. et al.’s [

19] study, “Extraction and characterization of sodium alginate from three brown algae collected from Sanur Coastal Waters, Bali as biopolymer agent,” revealed that the yield percentages produced by

S. aquifolium (21.74 ± 2.135%) and

T. ornata (20.16 ± 3.644%) were higher than those produced by

P. australis (5.89 ± 1.537%). Comparing

S. aquifolium and

T. ornata to

P. australis, the results of Duncan’s test showed a significant difference (

p < 0.05) in the yield. The yield that the two brown algae produced was surprisingly higher than that of the conventional alginate. Their findings differ from those of Reski et al. [

20] who reported low yields by calcium extraction (11.70 ± 0.41%) and acid extraction (9.95 ± 0.31%). However, according to Latifi et al. [

21], alginate extraction using the calcium approach yielded high yields between 25.02 and 30.01%. The yield results may be affected by the comparison group and extraction temperature [

22].

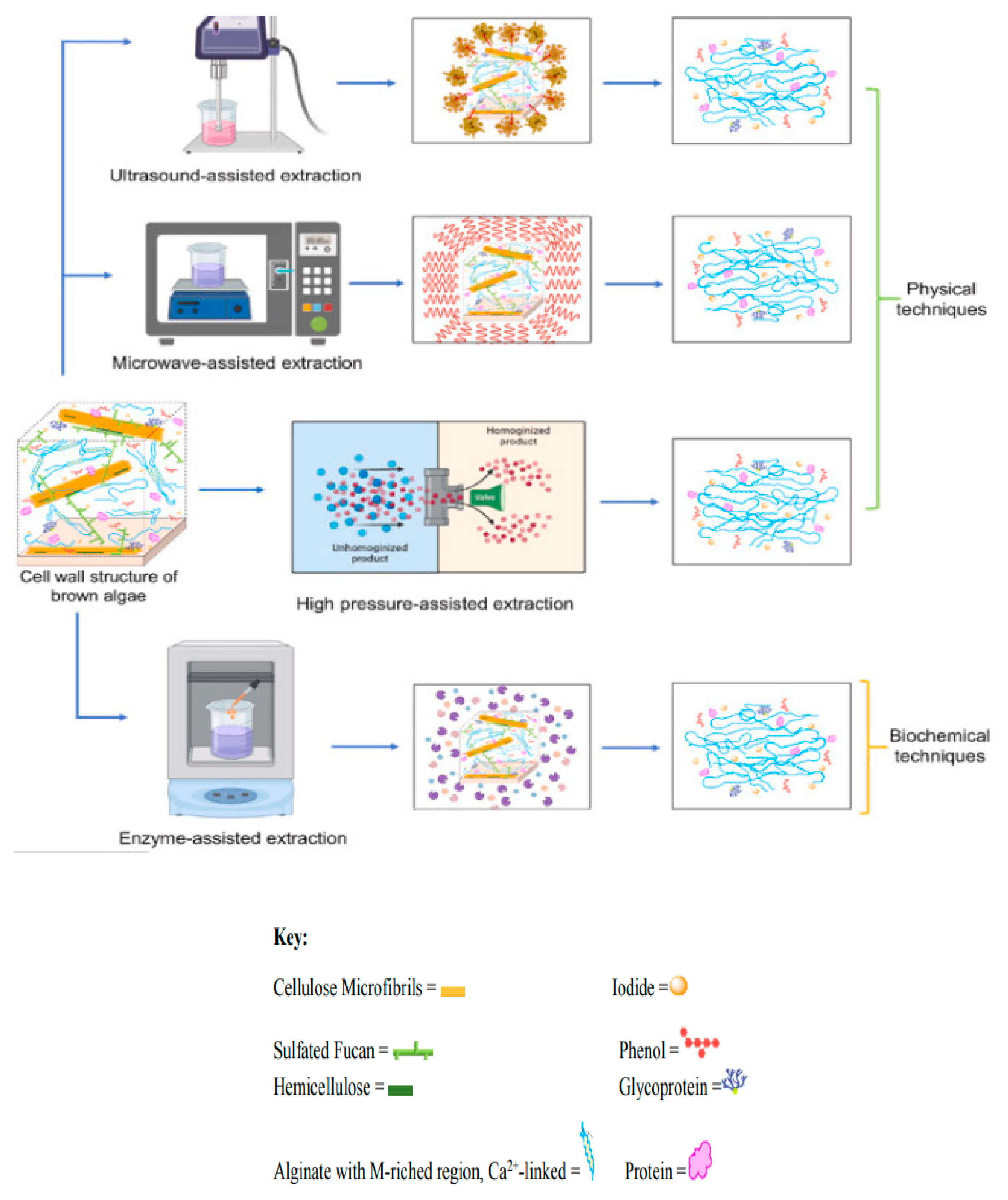

5. Alginate Production Process: Novel Technology Approach

5.1. Microwave Assisted Extraction (MAE)

The use of microwaves to extract components from plant material has attracted a lot of attention and shown great promise in recent years. The extraction phase limits the efficient extraction of several important components from plant material, and conventional methods for the extraction of active ingredients are time and solvent intensive. Among the appealing aspects of this novel, promising microwave aided extraction approach are its high and quick extraction performance ability with reduced solvent consumption and the protection it provides for thermally unstable elements [

23]. Plant material has been successfully isolated using MAE. To their knowledge, only one prior study from their research group focuses on the extraction of alginates from the brown seaweed species

Saccorhiza polyschides. Despite being a significant extraction technique, only a small number of studies have documented the use of microwave technology for the extraction of polysaccharides (such as agar and fucoidans) from seaweeds [

24].

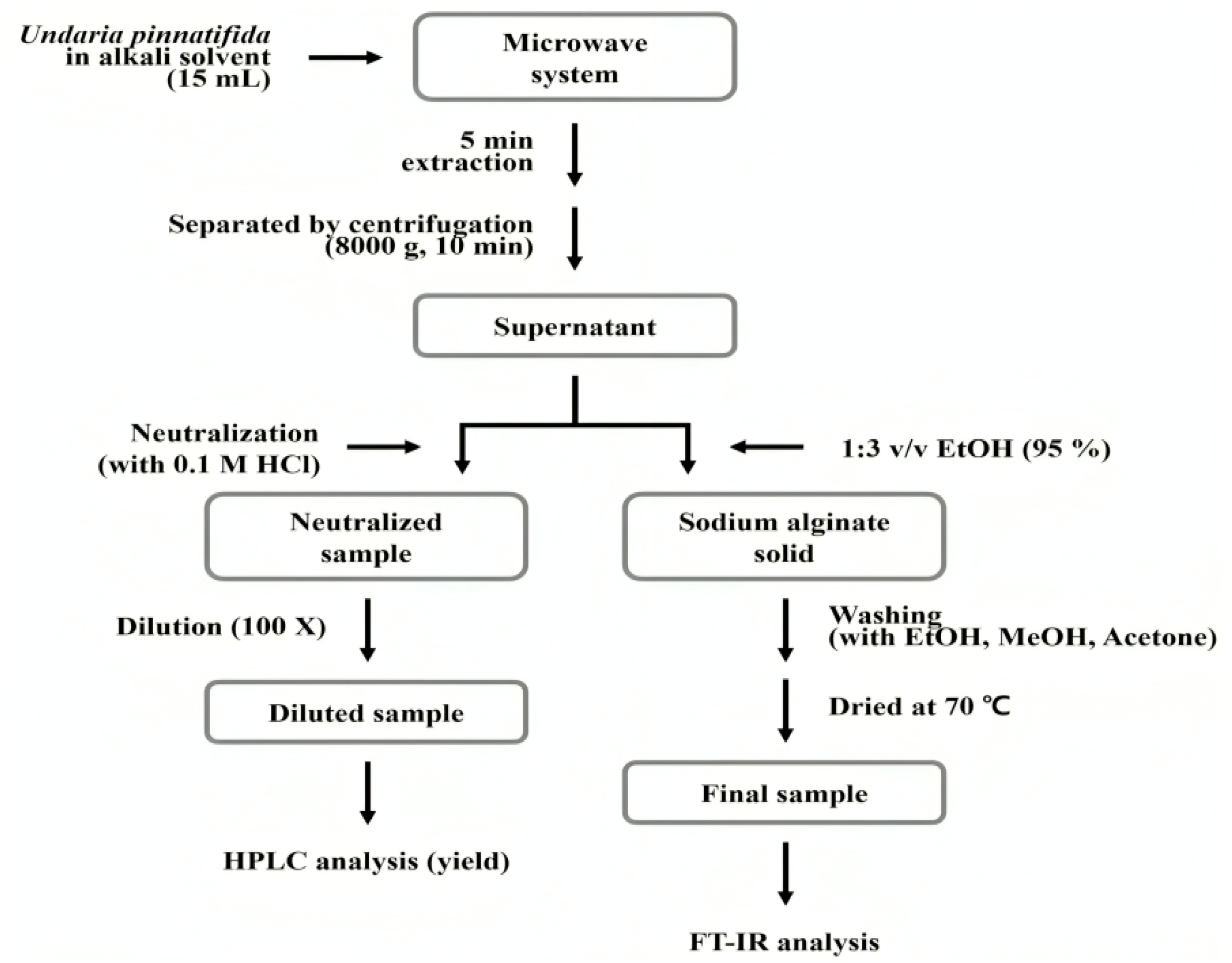

The study “Microwave-assisted extraction of sodium alginate from brown macro-algae

Nizimuddinia zanardini, optimization and physicochemical properties” by Torabi, P. et al. [

25] reported that the sodium alginate extraction yeild (EY) ranged from 24.21% to 33.33% based on dry matter (

Figure 3). The maximum yield was recorded at 75 °C, 400 W, 30 min, and 20 mL/g S/A ratio. Furthermore, at 45 °C, 400 W, 10 min, and a S/A ratio of 20 mL/g, the lowest yield was achieved. This research presents the first extraction of sodium alginate from

N. zanardini using a microwave. Temperature, time, microwave power, and S/A ratio were the four independent factors whose impacts on sodium alginate’s EY and Uronic acid were investigated. The findings showed that the EY and UA of sodium alginate were significantly impacted by the process factors and the use of microwaves during extraction [

25].

Nesic, A. et al. [

26] reported that the final product of untreated alginate produced by employing traditional techniques (demineralization and alkaline treatment) is 32% in their work on “Microwave Assisted Extraction of Raw Alginate as a Sustainable and Cost-Effective Method to Treat Beach-Accumulated

Sargassum Algae.” As it is known that repeating the demineralization and alkalinization procedures to drive the extraction up to high yields, depending on extraction duration and temperature, might result in a high yield of alginates, this outcome is expected. This approach, however, necessitates a significant number of solvents, high energy usage, and lengthy extraction duration. In reality, because of the anticipated eventual uses in the food, pharmaceutical, and biomedical industries, this process produces a very clean polymer.

As was already noted, alternative, environmentally friendly, and economically viable extraction methods can be used for agricultural purposes. According to preliminary findings, untreated algae could not have their alginate removed in water. The breakdown of algal cell walls and the simpler release of alginate in water, on the other hand, were made possible by microwave pre-treatment. The extraction yield is less than 5%, though. Additionally, Rostami et al. achieved the lowest alginate yield (3.8%) for the water treatment [

27]. Using the alkaline extraction method increased the amount of extracted alginate from pre-treated algae by 20–24%, while using the acid + alkaline method raised it by 32–36% [

26]. A simplified schematic representation of traditional alginate manufacturing processes is displayed in

Figure 3.

Mário S. et al. [

28] state in their study “Microwave-Assisted Alginate Extraction from Portuguese Saccorhiza polyschides -Influence of Acid Pre-treatment” that MAE of alginate was then performed on all harvested samples after they were subjected to the conventional acid pre-treatment previously described and under ideal conditions. In order to determine whether

Saccorhiza polyschides showed notable yield changes in alginate that might have resulted from its natural life cycle, this comparison sought to gather data between the two processes carried out with a brief time delay. In all seaweed samples studied, an increase in the yield of alginate extraction from

Saccorhiza polyschides under ideal acid pre-treatment conditions was noted. Increases compared to values obtained with traditional acid pre-treatment ranged from 100% in the August harvest to 143% in the July harvest. The results unambiguously demonstrate that acid pre-treatment has a significant impact on alginates’ MAE [

28].

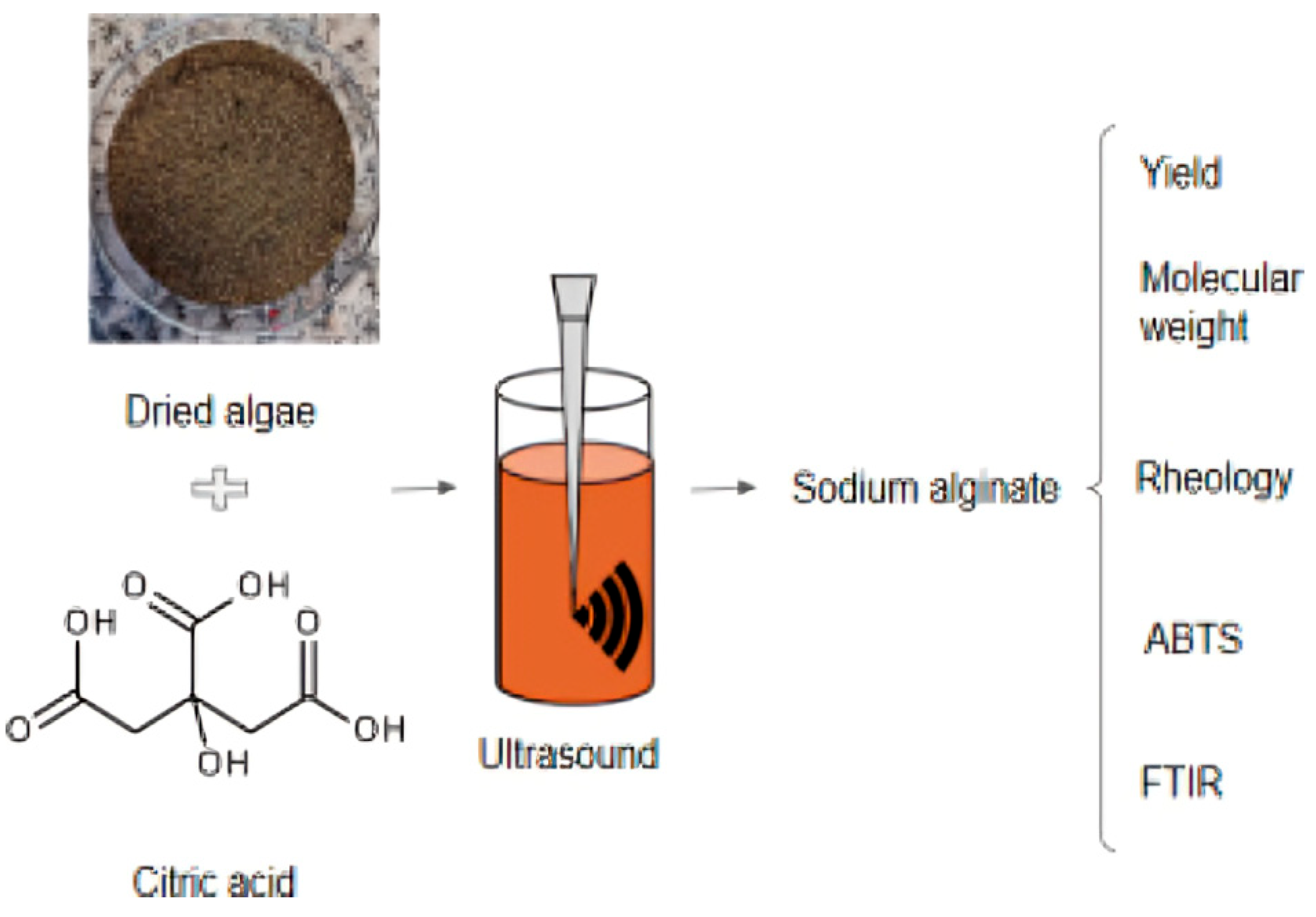

5.2. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Alginate

Ultrasound-assisted extraction is regarded as a unique extraction method that requires less solvent, is easy to handle, environmentally benign, and has a quick extraction rate [

29].

Sargassum binderi and

Turbinaria ornate alginate extraction was studied by Youssouf et al. [

30] at different pH values, solid loading ratios, and extraction times, along with the inclusion of ultrasound therapy [

30]. Alginate extraction yielded 54.06% under ideal conditions (pH 12 using Na

2CO

3, 1:100 loading ratio, 40 min with ultrasound at 25 kHz, 150 W). However, the experimental results demonstrated that, as previously mentioned, the extraction process is highly sensitive to pH. The ultrasound creates physical forces like shear, acoustic streaming, and microjets, which cause the cell wall to disperse, the particle size to decrease, and the solvent and target molecules to make good contact [

31].

Ummat, V. et al. [

32] found that the crude alginate yield varied from 0.020% (30% US amplitude and 10 min sonication time) to 6.19% (55% US amplitude and 20 min sonication time) in their work on “Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Alginate from

Fucus vesiculosus Seaweed By-Product Post-Fucoidan Extraction.” When the alginate content of the crude alginate samples was measured, a sample treated with 55% US amplitude for 6 min of sonication produced a maximum value of 78.22%, while a sample treated with 30% US amplitude for 30 min produced a minimum value of 39.76%. The most optimal extraction parameters for getting crude alginate with the highest alginate content (%) were determined to be a US amplitude of 68.86% and a sonication period of 30 min. Alginate content (%) was significantly impacted by the independent variable (% ultrasonic amplitude), however crude alginate yield was not significantly impacted [

32].

According to the study “Ultrasound-assisted extraction of alginate from

Ecklonia maxima with and without the addition of alkaline cellulase factorial and kinetic analysis” by Van Sittert, D. et al. [

33], the alginate extraction yield increased non-linearly fairly rapidly (compared to the later extraction times) for the first 60 min of extraction for all experimental runs (

Figure 4). After 60 min, there was a more gradual and linear rise until the extraction was finished. After the extraction procedure, the measured alginate concentrations ranged from 11.6 to 18.1 g/L; taking into account that 40 g/L or 4% of the dry matter was charged at the beginning of the experiment, these yields correspond to 29.0 to 45.3% of the initial dry weight (dw) being extracted as alginate. Specifically, the largest alginate yields of 45.3% and 40.3% of initial dw under endpoint circumstances were achieved by experimental runs (pH 10, 60 °C, E:S 0%), and (pH 10, 60 °C, E:S 1%) [

33].

5.3. Enzyme Assisted Extraction (EAE) of Alginate

The breakdown of polysaccharide cell walls by enzymes is one of the most effective extraction methods for increasing the yield of bioactive chemicals. Comparing enzyme extraction to the traditional approach, the molecular weight of the polysaccharides isolated from

Ecklonia radiata algae is reduced by 20 to 50%, suggesting that enzymes are capable of hydrolyzing certain bonds in alginate molecules [

34]. The water extraction approach produced the lowest alginate extraction yield (3.30%) in one study, although the alkalase (3.5%) and cellulase (3.47%) treatments resulted in a marginal increase in the extraction process yield [

35]. The optimal conditions for extracting sulfated polysaccharide from

Turbinaria turbinata are a cellulase concentration of 1.5 µL/mL and a hydrolysis time of 19.5 h, which yielded 25.13% [

36]. Similarly, the yields of sulfated polysaccharides extracted from the alga

Turbinaria turbinate which were extracted using the enzymes cellulose, amyloglucosidase, and vicozyme were higher than those obtained without the enzyme-assisted extraction processes. Furthermore, compared to standard water extraction without enzymes (3.8%), the alginate yield rose by up to 6.60% with the introduction of cellulase, whereas alkalase had no effect. Additionally, alginates with the lowest M/W ratio and the least amount of chemical contamination with proteins and polyphenols are produced by the employment of alkalase and cellulase enzymes [

27].

In their work titled “Sequential and enzyme-assisted extraction of algal bio-products from

Ecklonia maxima,” Blessing et al [

37] found that the sequential enzyme-assisted extraction yielded yields of 17.6% (

w/

w) fucoidan and 9.5% (

w/

w) calcium alginate, respectively (

Figure 5). Afterwards, aqueous sodium carbonate was used to extract 25% (

w/

w) sodium alginate from the leftover seaweed residue. They used the same algal biomass to extract fucoidan, alginate, and phenolics. In contrast to those extracted using conventional techniques, which varied from 1.1% to 6.8%, the yields for fucoidans were comparatively high [

37].

According to the study “Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Alginate from Beach Wrack

Fucus vesiculosus” by Malvis R. et al. [

38], the recovered monosaccharides following hydrolysis add up to 24.8%dw without anhydro adjustment. Alginate and other polysaccharides most likely account for the remaining 32.4% of the overall mass balance as they were not measured with the HPLC method. Both extraction duration and enzyme activity had a significant impact on the extraction yield, according to the data, which also demonstrated a similar pattern for the four enzymes under investigation: higher alginate yields are the consequence of longer extraction times and higher enzyme activity. The highest experimental extraction yield (9.60 ± 1.03%) was achieved with Alcalase 2.4 L (15 h, 824.5 U), followed by Viscozyme (9.19 ± 0.75%, 15 h, 500 U), Neutrase 0.8 L (8.76 ± 0.22%, 15 h, 824.5 U), and Celluclase 1.5 L (8.75 ± 0.17%, 15 h, 311.4 U). However, no significant differences were found between the various enzymes tested. The macroalgae species, growth conditions, and the extraction and purification process are some of the variables that affect alginate extraction yield [

38].

In their work on “A novel enzyme-assisted one-pot method for the extraction of fucoidan and alginate oligosaccharides from

Lessonia trabeculata and their bioactivities,” Yan, C. et al. [

39] stated that crude alginate oligosaccharides were purified in a multifunctional membrane separation plant (LNG-UF-101, Shanghai Longyi Membrane Separation Equipment Engineering Co. Shanghai, China) before alginate oligosaccharides (AOS) were obtained. Around 21.36% of AOS was produced by L. trabeculata. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was used to examine each tube with a high sugar content in order to determine the composition of AOS. The tri-saccharides, tetra-saccharides, and penta-saccharides made up the majority of AOS, according to the TLC data [

39].

5.4. Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) of Alginate

Getachew, A. et al. [

40] reported the crude alginate and fucoidan contents of the extract at various extraction temperatures in their work, “Effect of Extraction Temperature on Pressurized Liquid Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from

Fucus vesiculosus.” The extract’s alginate content rose from 120 to 130 degrees Celsius. There was no discernible difference in the extractions at 130 and 150 °C, however the alginate yield decreased as the temperature rose. At 140 °C, 2.08 ± 0.12% alginate was the most amount that could be extracted [

40].

A novel extraction techniques called liquid extraction under pressure uses high temperatures and pressures to quickly and efficiently extract target chemicals in a light- and oxygen-free environment while using the least amount of solvent possible (

Figure 6) [

25]. While the high pressure keeps the solvent below the boiling point, the high temperature improves the sample’s dissolution and speeds up its rate of diffusion [

41]. There are several names for the pressurized liquid extraction process, including pressurized fluid extraction (PFE), pressurized solvent extraction (PSE), accelerated solvent extraction (ASE), critical water extraction (SWE), and hot water extraction (HWE), depending on the solvent and the circumstances (

Table 1). Different kinds of static [

42] or dynamic [

43] extraction apparatus with pressurized liquid have been utilized to extract polysaccharides from brown algae. Some indoor equipment (off-scale laboratory) can be utilized in dynamic mode (continuous flow), although the equipment used was laboratory-scale commercial equipment typically used for pressured liquid extraction, created by Dionex Corporation (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in 1995 [

44].

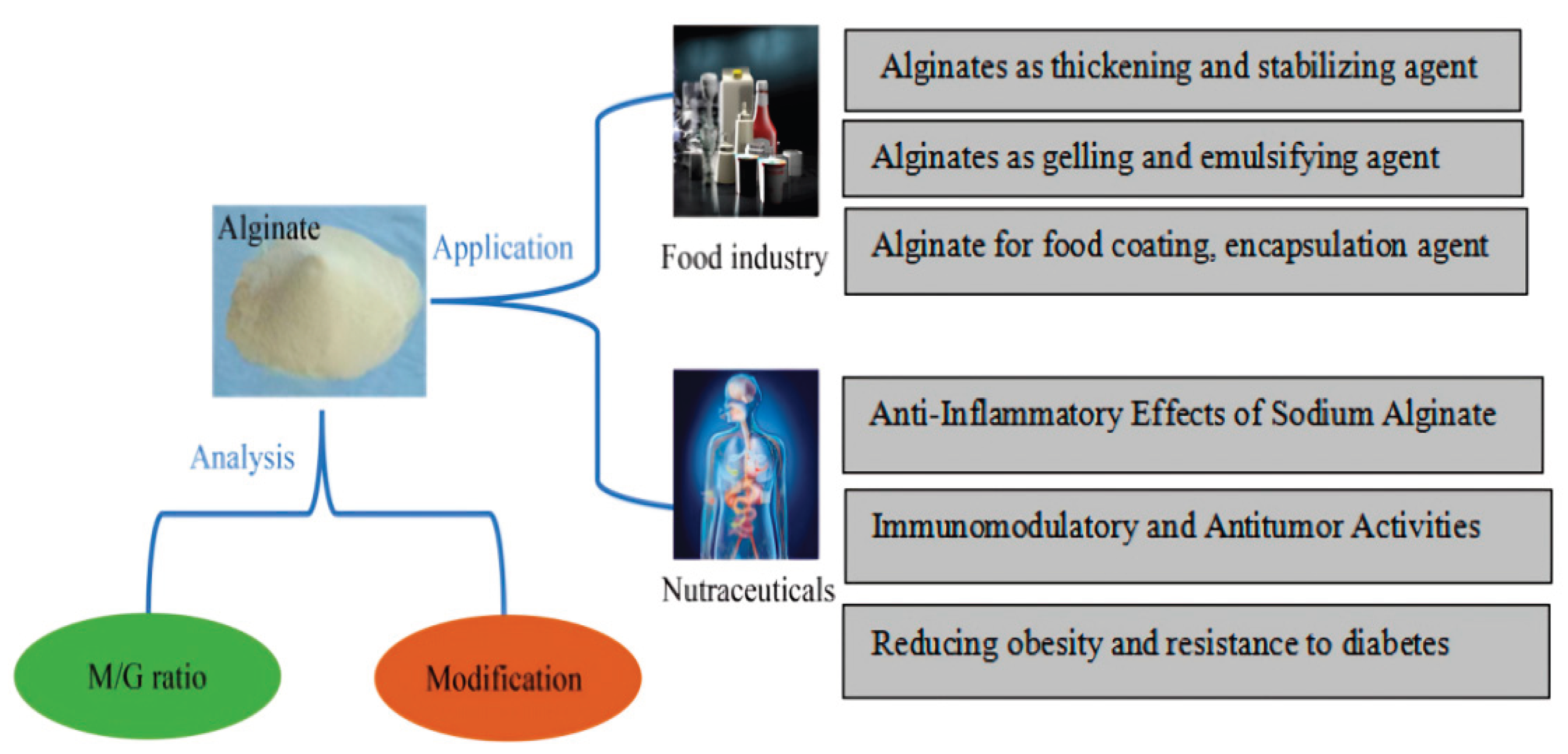

6. Application of Alginate Food Polymer in Food Industry

The food industry has taken a keen interest in alginate, a naturally occurring anionic polysaccharide that is mostly derived from brown seaweeds, because of its distinct physicochemical characteristics and range of applications. Alginate, a food polymer that is made up of residues of β-D-mannuronic acid (M) and α-L-guluronic acid (G), has remarkable gelling, thickening, and stabilizing properties due to its ability to form hydrogels in the presence of divalent cations like calcium ions [

45].

Alginates are a class of viscous polysaccharides that are extracted from brown seaweed and that certain bacterial species create as an extracellular matrix. Alginates have long been employed in a variety of food applications as thickeners, emulsifiers, and stabilizing agents (

Table 2). Because of their distinct biochemical and biophysical characteristics, alginates are finding a variety of new uses in food. Modified alginate based emulsion, which offers steady and regulated discharge, may be a promising solution to the problems facing emulsifiers in the food company. This is because proteins and surfactant based emulsions have been found to become unstable over time. High oil management and a reduction in the breakdown of unsaturated fatty acids are two benefits of alginate emulsion. Alginate’s ability to function as an emulsifier in water/oil solutions was then found. Water and oil phases in food systems can be dispersed by alginate. In the process of making margarine, mayonnaise, and salad dressings, this characteristic can stabilize the emulsion and stop the water and oil phases from separating. Additionally, employing alginate modified with Dodecenyl Succinic Anhydride (DSA) enhances its hydrophobic properties and qualifies it as a viable option for emulsification. Alginate emulsions are a promising emulsifier in the food sector due to their stability across a range of temperature, pH, and ionic strength. Alginate’s high emulsifying activity and durability at acidic pH values, in particular, can encourage its usage in food items that need gelation and contain ascorbic acid or citric acid [

45]. The gel-forming properties of alginate enable the production of a variety of food structures and textures. A gel’s characteristics are determined by its M/G ratio; a higher G content makes the gel stronger and more brittle, while a higher M content makes the gel softer and more elastic. To satisfy consumer preferences, food technologists can create products with particular textural qualities thanks to this tunability. Alginate is used to stabilize cheeses and yogurts in dairy applications, improving mouthfeel and avoiding whey separation. It helps bakery goods retain moisture, which prolongs their shelf life and keeps them soft. Furthermore, alginate can be used to create heat-stable gels, which makes it appropriate for items that need to be heated, like baked goods and canned foods [

46]. Probiotics, vitamins, and antioxidants are just a few of the bioactive substances that can be effectively encapsulated in alginate’s gel matrix. This encapsulation ensures the stability and bioavailability of sensitive ingredients after ingestion by shielding them from environmental stresses like pH changes and enzymatic degradation. To increase the viability of

Lactobacillus casei during storage and gastrointestinal transit, for example, alginate-based microgels have been used to encapsulate the bacteria. The preservation of polyphenols’ antioxidant activity through encapsulation in alginate matrices has also been demonstrated, aiding in the creation of functional foods with advantageous health effects [

47]. The ability of alginate to form films is used to make edible coatings that prolong the shelf life of perishable products by acting as barriers against moisture, oxygen, and microbiological contamination. Meats, cheeses, and fresh-cut fruits and vegetables benefit most from these coatings. The protective effect of alginate films is further increased by adding antimicrobial agents, such as essential oils or silver nanoparticles. For instance, it has been shown that alginate films containing oregano essential oil are effective at preventing bacteria from growing on seafood products. Alginate can also be combined with other biopolymers, such as chitosan, to enhance the mechanical characteristics of films and provide extra antimicrobial activity [

48]. Alginate is being investigated as a nutraceutical delivery system as a result of the growing demand for functional foods. Sensitive compounds can be encapsulated in it for controlled release in the gastrointestinal tract due to its gentle gelation conditions and biocompatibility. Delivery systems based on alginate have been developed for a variety of bio-actives, such as curcumin, omega-3 fatty acids, and different vitamins. These systems improve the efficacy and health benefits for consumers by protecting the encapsulated compounds and enabling targeted release [

49]. The viscosity-modifying qualities of alginate are used to modify the rheological behavior of food items. Because of its shear-thinning behavior, it facilitates manufacturing while preserving product stability in processes like pumping and mixing. Alginate prevents phase separation and adds a pleasing mouthfeel to sauces, dressings, and drinks. Its capacity to interact with other hydrocolloids, including carrageenan and pectin, enables the creation of intricate textures and stability profiles that are suited to particular uses [

50]. Alginate is appropriate for 3D food printing applications due to its quick gelation when calcium ions are present. Customized textures and shapes can be produced by varying the alginate concentrations and cross-linking conditions, opening the door to innovative food designs and individualized nutrition [

8].

Because alginate can thicken marmalade, jars, savory sauces, and desserts, it can be used to introduce what consumers want like low-fat products, modern water storage capacity for industrial foods, and organoleptic properties. This makes alginate a versatile ingredient in the food industry. To measure product quality and trust, several key elements are essential. For instance, solutions including network interaction have varying viscosities depending on the molecular weight of the alginate. It indicates that a higher alginate molecular weight results in more engagement. For example, the viscosity improves as the alginate concentration rises, but the viscosity decreases when the temperature rises because of changes in the chain structure.

Weak viscosity and a reduction in electric charges are the results of high salt and pH (below 3 and above 11). In general, alginate and polysaccharides can work in concert. Gums interact with alginate due to their charges and flexibility. However, the concentration of calcium determines excellent qualities. When 2 mM of calcium ions were added to the gums derived from T. cordifolia bark and I. gabonensis seeds, the best compact gel was produced [

51].

Alginate is a linear polymer that, when dissolved in water and dried, forms a clear, translucent film. Alginate films are resistant to ripping, oil-impermeable, and have exceptional tensile strength and flexibility. Alginate turns into an edible coating that provides protective properties to food after an aqueous solution is applied to its surface. Alginate’s capacity to form films has great potential in the functional food sector because of the current push to reduce or replace non-biodegradable or non-recyclable food packaging. Food coatings made of alginate are safe to use, simple to prepare, and have a long shelf life and high product stability. Nonetheless, alginate gels are permeable to water and oxygen due to their porous structure [

52].

The growing consumer demand for clean-label and eco-friendly food ingredients are met by alginate, a naturally occurring, biodegradable polymer. By lowering dependency on artificial additives, its use can support more environmentally friendly methods of food production. Additionally, alginate’s potential to create edible packaging materials and its function in extending the shelf life of food reduce food waste, underscoring its importance in advancing sustainability in the food industry.

7. Alginate’s Possible Use in Functional Foods

The functional food industry is very interested in alginate, a natural brown seaweed polysaccharide, because of its many health benefits and adaptable properties. Using alginate as a glue, foods that promote gut health can be prepared by encouraging the growth of good bacteria in the gut by acting as a prebiotic [

52]. Prebiotics have the potential to improve digestion, reduce the risk of digestive disorders and improve the gut flora in general. By delaying stomach emptying, the ability of alginate to form gel-like structures is another known property that can contribute to a sense of satiety. This makes it a useful ingredient in weight loss products, as it can help you to reduce your calorie intake by helping you feel fuller for longer. In addition to its role in promoting satiety, alginate may also help to control blood sugar levels by delaying the breakdown and absorption of carbohydrates, causing the blood sugar level to rise more slowly after a meal. Alginate can therefore be an excellent ingredient in foods intended to control diabetes or stimulate the secretion of insulin [

53]. Alginate is also useful for producing low-fat and low-sugar foods due to its ability to replicate the structure of fat and sugars. It can provide healthier substitutes for added calories in foods such as yoghurt, ice cream and snacks by providing a creamy flavor of fat or a sweetened consistency. Brown algae contains a natural polysaccharide called alginate, which has shown promising results in lowering LDL (bad) cholesterol and improving cardiovascular health [

54]. The main mechanism for this effect is the ability of alginate to bind to bile acids in the digestive tract. The liver produces bile acids from cholesterol, which are necessary for digesting fats. After ingestion, alginate binds to bile acids in the gut to form a gel-like structure which prevents absorption of the bile acids in the small intestine and promotes their elimination in the faces. In response to this loss, the liver uses cholesterol as a raw material to produce more bile acid. LDL cholesterol levels are reduced because the liver uses circulating cholesterol to create new bile acids. Alginate can also bind to cholesterol directly in the intestine, blocking its absorption and reducing cholesterol levels in the blood. According to research, including in vitro and animal studies, alginate can successfully reduce total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol without significantly altering HDL (Good) cholesterol. These results were confirmed by some clinical studies in humans, which showed that the use of alginate supplements could significantly lower LDL cholesterol [

55]. In addition to its well-known benefits in lowering cholesterol and improving gut health, alginate has antioxidant properties which can protect cells against oxidative damage. The imbalance between antioxidants and free radicals in the body causes oxidative stress, which damages DNA, proteins and cells. Chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and certain forms of cancer are also associated with this damage. According to some research, alginate contains antioxidants such as polyphenols which can counteract free radicals and reduce oxidative damage. Alginate has the potential to reduce inflammation, which is a major cause of many chronic diseases, by scavenging these harmful free radicals. Oxidative stress-related diseases such as heart disease and neurodegenerative diseases can be prevented or delayed by the antioxidant activity of alginate [

56].

A third of the world’s population suffers from obesity, which has spread like a pandemic and increases the risk of type 2 diabetes in those individuals. There aren’t many safe and efficient anti-obesity medications available right now. Using natural food ingredients to Fight obesity is a new trend. An energy-restricting food additive called alginate has been created to help obese people lose weight. A 12-week dietary intervention study has demonstrated this [

44]. Anti-inflammatory activities are among the many beneficial biological effects of sodium alginate that have been authorized. In 2022, Niu et al. proposed that by regulating oxidative stress, intestinal microbes, and inflammatory factors, sodium alginate combined with chlorogenic acid improves the therapeutic effect on ulcerative colitis [

57]. Innate immune cells’ surface receptors play a crucial role in identifying infections and triggering immunological reactions (

Figure 7). They are crucial for phagocytosis and complement regulation and activation, pro-inflammatory signaling pathway initiation, and apoptosis induction. Kurachi et al. confirmed that alginate treatment could stimulate TNF-α release in RAW264.7 cells by comparing the effects of alginate polymers with varying Mw and M/G ratios on tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production [

58].

8. Discussion

The genera

Laminaria, Macrocystis, and

Ascophyllum are among the brown seaweeds that are the main source of alginate produced worldwide. Aquaculture is the source of alginate; however a considerable quantity is extracted from wild seaweed. In addition to seaweed, microorganisms like

Azotobacter and

Pseudomonas species can also be used to extract alginate [

13]. The sources of alginate are still limited to seaweed and little bacterial species, therefore searching for other alternatives is crucial for alginate variety production. Only three species of brown seaweed

Laminaria,

Microcystis, and

Ascophyllum are thought to be sufficiently abundant or appropriate for use in alginate extraction on a commercial basis.

Sargassum and other seaweed species are usually only utilized in situations where commercial sources are scarce. This is because

sargassum alginate was found to be of “borderline” quality [

12]. Because they are prevalent in particular geographic areas and contain large amounts of alginic acid, the precursor to alginates,

Laminaria,

Macrocystis, and

Ascophyllum are the finest algae species for extracting alginate for the food field. These species, whose alginate concentrations range from 17% to 44%, are the most significant sources of alginate. This species’ thick, strong stipes (stems) contains a high concentration of high-quality alginate; typically, only the stipes are collected and dried. However, the yield of alginate extraction varies depending on the species and age of the seaweed, as well as environmental factors like light intensity, water temperature, currents, and nutritional status, as well as extraction methods.

The type of algae, extraction techniques, chemical modification, and other factors all affect the quality and quantity of the alginate that is produced from brown seaweeds, which has a varied yield. The most common method for extracting alginates is conventional alkaline extraction [

19]. Alginate is most commonly extracted from seaweed using the conventional extraction method, which has several disadvantages. Taking a long time the procedure consists of several stages, such as pre-treatment, acid treatment, alkaline extraction, bleaching, drying, and precipitation, uses a lot of solvents and reagents. Numerous solvents and reagents are needed for the procedure. Ineffective to increase the yield of alginate, the acid treatment of biomass might be enhanced. On the other hand, new extraction methods like ultrasound and microwave aided extractions have drawn a lot of attention. The physiochemical, mechanical, and prospective uses of alginate are significantly influenced by the extraction parameters, such as temperature and extraction time.

This review showed that the non-conventional extraction techniques are obviously preferred than conventional extraction techniques. The food industry can use unconventional extraction techniques to extract alginate since they can be more economical, efficient, and environmentally friendly than traditional techniques. Using sound waves to break down cell walls, ultrasound-assisted extraction accelerates the release of chemicals and decreases particle size. UAE is quick, easy on the environment, and industrially scalable [

31]. The process known as microwave-assisted extraction breaks down cell walls and releases their contents by using microwaves. Bioactive chemicals are extracted from plants using pressurized liquid extraction, which involves high heat and pressure. Cell membrane electroporation is induced during pulsed electric fields extraction to boost extraction yield. Using a shift in temperature and pressure, supercritical CO

2 (SC-CO

2) extraction turns a gas into a supercritical fluid [

17]. Alginate extraction should be optimized to minimize carbon emissions, lower energy consumption, and combine alginate extraction with the manufacture of other value-added products in order to ensure sustainable alginate manufacturing.

The food industry has come to rely heavily on alginate, a natural polysaccharide that comes from brown seaweeds, because of its special structural and functional qualities. This review explored how alginate affects food microstructure and how it functions as a food polymer, emphasizing new developments and uses [

59]. The linear structure of alginate, which is made up of mannuronic (M) and guluronic (G) acid units, gives it unique gelling and film-forming properties. Gel strength and stability are greatly influenced by the M/G ratio; a larger G concentration improves calcium ion crosslinking and gel firmness. Alginate’s structural adaptability enables it to gel at low temperatures, making it appropriate for a range of food applications [

60]. Bioactive substances including vitamins, polyphenols, and probiotics can be encapsulated in alginate to protect them from the environment and increase their stability and bioavailability. Alginate beads, for example, have demonstrated enhanced homogeneity and stability when cocoa extract is encapsulated within them, particularly when calcium-induced gelation takes place internally [

61]. Alginate works well as a stabilizer and thickener in products like dairy products, sauces, and jams. In low-fat and reduced-sugar formulations, its gel-forming qualities help create the desired textures, while its shear-thinning behavior makes processing simple [

62]. Alginate-based coatings and films provide protection from microbiological contamination, gas exchange regulation, and moisture retention. Alginate coatings, for instance, have been used to prolong the shelf life of fresh-cut fruits and vegetables by slowing down respiration and postponing browning [

63]. Probiotics can be better preserved during storage and transit through the gastrointestinal tract by encapsulating them in alginate microgels. Research shows that probiotic strains like

Lactobacillus casei can be successfully shielded from harmful environments by alginate-based delivery systems [

61]. Several functional ingredients can be incorporated into alginate due to its versatility. For example, films based on alginate have been created to deliver bioactive substances, essential oils, and antioxidants, thereby improving the functional aspects of food products [

64]. Alginate gels are shown to have a porous network structure by sophisticated imaging methods like scanning electron microscopy (SEM). This microstructure improves the texture of food products and allows for the controlled release of encapsulated compounds. The microstructure can be tailored to satisfy particular functional requirements by adjusting the gelation conditions, such as pH and calcium concentration. Alginate is a natural polymer that provides a sustainable substitute for artificial additives. It is appropriate for environmentally friendly food packaging options due to its non-toxic and biodegradable qualities. The increasing need for ecologically friendly food packaging materials is in line with research into edible films and coatings based on alginate [

64].

This review revealed that research on using edible bio-polymers to coat and form films on food products has recently increased. Films and coatings that are edible or biodegradable can be utilized to preserve the product’s quality over time. Freshly cut fruits, vegetables, and meat items covered with alginate solutions and additives have shown encouraging outcomes. However, new antibacterial, anti-oxidative, and anti-browning chemicals could be added to increase food safety and quality even further. It is possible to gain a deeper comprehension of any potential synergistic effects between active drugs and alginate coating. Alginate and its numerous derivatives have long been used in food and even as a binder in aquaculture because of their special abilities to agglutinate, thicken, gel, form films, and stabilize. Its ability to thicken makes it useful for ice cream toppings, syrups, and sauces [

65].

Alginate is an effective and organic food ingredient. Alginate has been used extensively in the food and nutraceutical industries due to its superior functional qualities of ion cross-linking, pH sensitivity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability when compared to other seaweed polysaccharides. Moreover, alginate is the only polysaccharide in which every component residue naturally contains carboxyl groups [

66]. Food films and colloids can be made with it. Its many beneficial biological properties also present chances for its development into nutraceuticals and functional foods. More research is needed to better understand the bioactivities and prospective uses of alginate, despite advancements in its manufacture and utilization in the food and nutraceutical industries. The development of functional foods or nutraceuticals is based on enhanced safety information and analysis techniques. The manufacture and use of alginate in the food and nutraceutical industries have been sufficiently studied, but further investigation is required to improve our understanding of its biological activity and its uses. Without a doubt, these investigations will improve the basis for future alginate production and use.

9. Challenges and Future Trend

Among the difficulties facing alginate research today are: The majority of research efforts are restricted to the experimental scale. Unfortunately a small number of research investigations include human clinical trials; Alginate manufacturing is still in its early stages as an industry. Regarding enzymatic digested alginate, the main factors limiting industrial production are: the high cost of alginate manufacturing; and the low yield and hydrolysis effectiveness of existing alginate lyases (alginate polymer-breaking enzymes that create monosaccharides or oligosaccharides). Alginate-based medications are therefore costly and put a greater financial strain on patients, particularly those that are not yet covered by health insurance. Despite these difficulties, alginate’s remarkable structural flexibility, high bioavailability, and variety of advantageous effects make it valuable for research, development, and a wide range of applications. For their possible uses, it is worthwhile to put in more work.

Future study should concentrate on the following areas: To give comprehensive experimental evidence for enhancing the dependability and persuasiveness of alginate products, more human clinical studies must be conducted. To increase the yield and production rate of alginate, more effective manufacturing techniques must be created. To achieve stable and effective alginate lyase, one approach calls for extensive study of large-scale screening and identification of microbes that produce the enzyme, cloning and expression of genes encoding alginate lyase, purification and characterization of enzymes with high catalytic activity, and optimization of the enzymatic hydrolysis process [

63]. Furthermore, comprehensive multidisciplinary methods must be created to alter and describe algae, exposing the underlying structure-function link. We think that the combined efforts of researchers will soon lead to the development and success of medications based on alginate.

10. Conclusions

Alginate has been used extensively in the food and nutraceutical industries due to its superior functional qualities, which when compared to other seaweed polysaccharides, include ion cross-linking, pH sensitivity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. The only polysaccharide that has carboxyl groups naturally present in every constituent residue is alginate. Food films and food colloids can be made with it. It also possesses a number of beneficial biological properties that hold promise for its development into nutraceuticals and functional foods. Despite advancements in the production and use of alginate in the food and nutraceutical industries, further research is still needed to fully comprehend its bioactivities and studies could explore the techno-economic viability of alginate applications in food systems. Better safety knowledge and analysis techniques serve as the cornerstone for its advancement in functional foods or nutraceuticals. An enhanced foundation for the future production and use of alginate will undoubtedly be provided by additional research in the aforementioned field.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dong, J.; St. Jeor, V.L. Food microstructure techniques. In Food Analysis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 557–570.

- Verboven, P.; Defraeye, T.; Nicolai, B. Measurement and visualization of food microstructure: Fundamentals and recent advances. Food Microstruct. Its Relatsh. Qual. Stab. 2018, 2, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh Chandra and Samsher Singh. Assessment of functional properties of different flours. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 2013, 8, 38; 4849-4852. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S.; Singh, S. Assessment of functional properties of different flours. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 4849–4852. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S.; Singh, S.; Kumari, D. Evaluation of functional properties of composite flours and sensorial attributes of composite flour biscuits. Optimization of biorefinery production of alginate, fucoidan and laminarin from brown seaweed. Durvillaea potatorum. Algal Res. 2019, 2, 3681–3688. [Google Scholar]

- Martău, G.A.; Mihai, M.; Vodnar, D.C. The Use of Chitosan, Alginate, and Pectin in the Biomedical and Food Sector-Biocompatibility, Bioadhesiveness, and Biodegradability. Polymers 2019, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma Khanal, B.K.; Bhandari, B.; Prakash, S.; Liu, D.; Zhou, P.; Bansal, N. Modifying textural and microstructural properties of low fat Cheddar cheese using sodium alginate. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 83, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pournaki, S.K.; Aleman, R.S.; Hasani-Azhdari, M.; Marcia, J.; Yadav, A.; Moncada, M. Current Review: Alginate in the Food Applications. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2024, 7, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannikova, A.; Evteev, A.; Pankin, K.; Evdokimov, I.; Kasapis, S. Microencapsulation of fish oil with alginate: In-vitro evaluation and controlled release. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 90, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Mooney, D.J. Alginate: Properties and biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Fernández, N.; Torres, M.D.; González-Muñoz, M.J.; Domínguez, H. Recovery of bioactive and gelling extracts from edible brown seaweed Laminaria ochroleuca by non-isothermal autohydrolysis. Food Chem. 2019, 277, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Li, X.; Yan, Q.; Reaney, M.J.T.; Jiang, Z. Alginate Oligosaccharides: Production, Biological Activities, and Potential Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 1859–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abka-Khajouei; Roya; Tounsi, L.; Shahabi, N.; Patel, A.K.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P. Structures, properties and applications of alginates. Mar. drugs. 2022, 20, 364.

- Hay, I.D.; Ur Rehman, Z.; Moradali, M.F.; Wang, Y.; Rehm, B.H. Microbial alginate production, modification and its applications. Microb Biotechnol. 2013, 6, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belattmania; Zahira; Kaidi, S.; El Atouani, S.; Katif, C.; Bentiss, F.; Jama, C.; Reani, A.; Sabour, B.; Vasconcelos, V. Isolation and FTIR-ATR and 1H NMR characterization of alginates from the main alginophyte species of the atlantic coast of Morocco. Molecules 2020, 25, 4335. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saji, S.; Hebden, A.; Goswami, P.; Du, C. A Brief Review on the Development of Alginate Extraction Process and Its Sustainability. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danya, G.; Subaranjani, S.; Ranjini, M.; Mahenthiran, R. Mahenthiran. Extraction of alginate from brown seaweed. Int. J. Res. Trends Innov. 2021, 6, 2456–3315. [Google Scholar]

- Rashedy, S.H.; Abd El Hafez, M.S.M.; Dar, M.A.; Cotas, J.; Pereira, L. Evaluation and Characterization of Alginate Extracted from Brown Seaweed Collected in the Red Sea. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putripermatasari, A.A.A.; Rosiana, W.; Wiradana, P.A.; Lestari, M.D.; Widiastuti, N.K.; Kurniawan, S.B.; Widhiantara, G. Extraction and characterization of sodium alginate from three brown algae collected from Sanur Coastal Waters, Bali as biopolymer agent. Biodiversitas 2022, 23, 1655–1663. [Google Scholar]

- Reski, S., M. E. Mahata, A. Yuniza, and Y. Rizal. "Alginate extraction from Turbinaria murayana seaweed as a feed additive for poultry." Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2025, 13, 6: 1184–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Latifi, A. M. , Sadegh Nejad, E., & Babavalian, H. Comparison of extraction different methods of sodium alginate from brown alga Sargassum sp. localized in the Southern of Iran. Journal of Applied Biotechnology Reports, 2015, 2, 2, 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Peteiro, C. Alginate Production from Marine Macroalgae, with Emphasis on Kelp Farming; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahelivao, M.P.; Andriamanantoanina, H.; Heyraudb, A.; Rinaudob, M. Structure and properties of three alginates from Madagascar seacoast alge. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 32, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, F.; Oliveira, F.; Correia, M.; Morais, S.; Delerue-Matos, C. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Alginate from Portuguese Brown Algae. Proc. Chem Por 2014, 32, 1245–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, P.; Hamdami, N.; Keramat, J. Microwave-assisted extraction of sodium alginate from brown macro-algae Nizimuddinia zanardini, optimization and physicochemical properties. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2021, 57, 872–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesic, A.; De Bonis, M.V.; Dal Poggetto, G.; Ruocco, G.; Santagata, G. Microwave Assisted Extraction of Raw Alginate as a Sustainable and Cost-Effective Method to Treat Beach-Accumulated Sargassum Algae. Polymers 2023, 15, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, Z.; Tabarsa, M.; You, S.G.; Rezaei, M. Relationship between molecular weights and biological properties of alginates extracted under different methods from Colpomenia peregrina. Process Biochem. 2017, 58, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Gomes, F.; Oliveira, F.; Morais, S.; Delerue-Matos, C. Microwave-Assisted Alginate Extraction from Portuguese Saccorhiza polyschides Influence of Acid Pretreatment. Int. J. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2015, 9, 1231. [Google Scholar]

- Nigam, S.; Singh, R.; Bhardwaj, S.K.; Sami, R.; Nikolova, M.P.; Chavali, M.; Sinha, S. Perspective on the Therapeutic Applications of Algal Polysaccharides. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 30, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssouf, L.; Lallemand, L.; Giraud, P.; Soulé, F.; Bhaw-Luximon, A.; Meilhac, O.; D’Hellencourt, C.L.; Jhurry, D.; Couprie, J. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and structural characterization by NMR of alginates and carrageenans from seaweeds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 166, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadam, S.U.; Tiwari, B.K.; O’Connell, S.; O’Donnell, C.P. Effect of Ultrasound Pretreatment on the Extraction Kinetics of Bioactives from Brown Seaweed (Ascophyllum nodosum). Sep. Sci. Technol. 2014, 50, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummat, V.; Zhao, M.; Sivagnanam, S.P.; Karuppusamy, S.; Lyons, H.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Noore, S.; Rai, D.K.; Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G.; O’Donnell, C. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Alginate from Fucus vesiculosus Seaweed By-Product Post-Fucoidan Extraction. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sittert, D.; Lufu, R.; Mapholi, Z. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of alginate from Ecklonia maxima with and without the addition of alkaline cellulase -factorial and kinetic analysis. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 2781–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensiddhi, S.; Lorbeer, A.J.; Lahnstein, J.; Bulone, V.; Franco, C.M.M.; Zhang, W. Enzyme-assisted extraction of carbohydrates from the brown alga Ecklonia radiata: Effect of enzyme type, pH and buffer on sugar yield and molecular weight profiles. Process Biochem. 2016, 51, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borazjani, N.J.; Tabarsa, M.; You, S.G.; Rezaei, M. Effects of extraction methods on molecular characteristics, antioxidant properties and immunomodulation of alginates from Sargassum angustifolium. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammed, A.M.; Jaswir, I.; Simsek, S.; Alam, Z.; Amid, A. Enzyme aided extraction of sulfated polysaccharides from Turbinaria turbinata brown seaweed. Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Blessing Mabate, Brett Ivan Pletschke, Sequential and enzyme-assisted extraction of algal bioproducts from Ecklonia maxima. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2024, 173, 0141–0229.

- Malvis Romero, A.; Brozio, F.; Kammler, S.; Burkhardt, C.; Baruth, L.; Kaltschmitt, M.; Antranikian, G.; Liese, A. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Alginate from Beach Wrack Fucus vesiculosus . Chem. Ing. Tech. 2023, 95, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Pan, M.; Geng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ye, S. A novel enzyme-assisted one-pot method for the extraction of fucoidan and alginate oligosaccharides from Lessonia trabeculata and their bioactivities. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2024, 42, 1998–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, A.T.; Holdt, S.L.; Meyer, A.S.; Jacobsen, C. Effect of Extraction Temperature on Pressurized Liquid Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Fucus vesiculosus. Mar. Drugs. 2022, 20, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Vivas, D.; Ortega-Barbosa, J.P.; del Pilar Sánchez-Camargo, A.; Rodríguez-Varela, L.I.; Parada-Alfonso, F. Pressurized Liquid Extraction of Bioactives. Compr. Foodomics 2021, 754–770. [Google Scholar]

- Santoyo, S.; Plaza, M.; Jaime, L.; Ibañez, E.; Reglero, G.; Señorans, J. Pressurized liquids as an alternative green process to extract antiviral agents from the edible seaweed Himanthalia elongata. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravana, P.S.; Cho, Y.J.; Park, Y.B.; Woo, H.C.; Chun, B.S. Structural, antioxidant, and emulsifying activities of fucoidan from Saccharina japonica using pressurized liquid extraction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 153, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrinčić, A.; Balbino, S.; Zorić, Z.; Pedisić, S.; Kovačević, D.B.; Garofulić, I.E.; Dragović-Uzelac, V. Advanced technologies for the extraction of marine brown algal polysaccharides. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, G. , Gåserød, O., Krych, Ł., Castro-Mejía, J. L., Kot, W., Saarinen, M.T.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Nielsen, D.S.; Rattray, F.P. Nielsen, and Fergal, P. Rattray. Modulating the Gut Microbiota with Alginate Oligosaccharides In Vitro. Nutraceuticals 2022, 3, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idota; Yoko; Kato, T.; Shiragami, K.; Koike, M.; Yokoyama, A.; Takahashi, H.; Yano, K.; Ogihara, T. Mechanism of suppression of blood glucose level by calcium alginate in rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 1362–1366.

- Idota, Y.; Kogure, Y.; Kato, T.; Ogawa, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Kakinuma, C.; Yano, K.; Arakawa, H.; Miyajima, C.; Kasahara, F.; et al. Cholesterol-lowering effect of calcium alginate in rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 39, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, B.S.; Buazar, F.; Hosseini, S.M.; Mousavi, S.M. Enhanced antibacterial activity, mechanical and physical properties of alginate/hydroxyapatite bionanocomposite film. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noore, S.; Pathania, S.; Fuciños, P.; O’Donnell, C.P.; Tiwari, B.K. Nanocarriers for Controlled Release and Target Delivery of Bioactive Compounds; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, D.; Yang, X.; Yao, L.; Hu, Z.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Lu, J. Potential Food and Nutraceutical Applications of Alginate: A Review. Mar Drugs 2022, 20, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdi, Z. Applications of Alginate in the Fields of Research Medicine, Industry and Agriculture. In Alginate-Applications and Future Perspectives; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Puscaselu, G.; Roxana; Lobiuc, A.; Dimian, M.; Covasa, M. Alginate: From food industry to biomedical applications and management of metabolic disorders. Polymers 2020, 12, 2417. [CrossRef]

- Łętocha; Anna; Miastkowska, M.; Sikora, E. Preparation and characteristics of alginate microparticles for food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 3834. [CrossRef]

- Petzold; Guillermo; Rodríguez, A.; Valenzuela, R.; Moreno, J.; Mella, K. Alginate as a versatile polymer matrix with biomedical and food applications. In Materials for Biomedical Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 323–350.

- Rezaul, M.; Shishir, I.; Ferdowsi, R.; Rahman, R.T.; Van Vuong, Q. Micro and nano encapsulation, retention and controlled release of flavor and aroma compounds: A critical review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman; Mostafizur, M.; Shahid, M.A.; Hossain, M.T.; Sheikh, M.S.; Rahman, M.S.; Uddin, N.; Rahim, A.; Khan, R.A.; Hossain, I. Sources, extractions, and applications of alginate: A review. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 443.

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, G.; Chen, H. The Applications of Alginate in Functional Food Products. J Nutr Food Sci. 2020, 3, 013. [Google Scholar]

- Bojorges, H.; López-Rubio, A.; Martínez-Abad, A.; Fabra, M.J. Overview of alginate extraction processes: Impact on alginate molecular structure and techno-functional properties. Trends Food Sci. Amp; Technol. 2023, 140, 924–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Cui, Z. The combination of sodium alginate and chlorogenic acid enhances the therapeutic effect on ulcerative colitis by the regulation of inflammation and the intestinal flora. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 10710–10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurachi, M.; Nakashima, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Oda, T.; Miyajima, C.; Iwamoto, Y.; Muramatsu, T. Comparison of the activities of various alginates to induce TNF-α secretion in RAW264.7 cells. J. Infect. Chemother. 2005, 11, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan; Rama, R.; Olasupo, A.D.; Patel, K.H.; Bolarinwa, I.F.; Oke, M.O.; Okafor, C.; Nkwonta, C.; Ifie, I. Edible biopolymers with functional additives coatings for postharvest quality preservation in horticultural crops: A review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1569458.

- Yerramathi; Bhagath, B.; Muniraj, B.A.; Kola, M.; Konidala, K.K.; Arthala, P.K.; Sharma, T.S.K. Alginate biopolymeric structures: Versatile carriers for bioactive compounds in functional foods and nutraceutical formulations: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127067.

- Katarzyna, A.; Sionkowska, A. State of innovation in alginate-based materials. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitanya, M.; Pawar, S.; Suvarna, V. Recent advancements in alginate-based films for active food packaging applications. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1246–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belik, A.; Silchenko, O.; Malyarenko, A.; Rasin, M.; Kiseleva, M.; Kusaykin, S. Ermakova. Two new alginate lyases of PL7 and PL6 families from polysaccharide-degrading bacterium Formosa algae KMM 3553T: Structure, properties, and products analysis. Marine Drugs 2020, 18, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zeng, D.; Wu, J. Lin. Single-point mutation near active center increases substrate affinity of alginate lyase AlgL-CD. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 21, 406. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).