Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

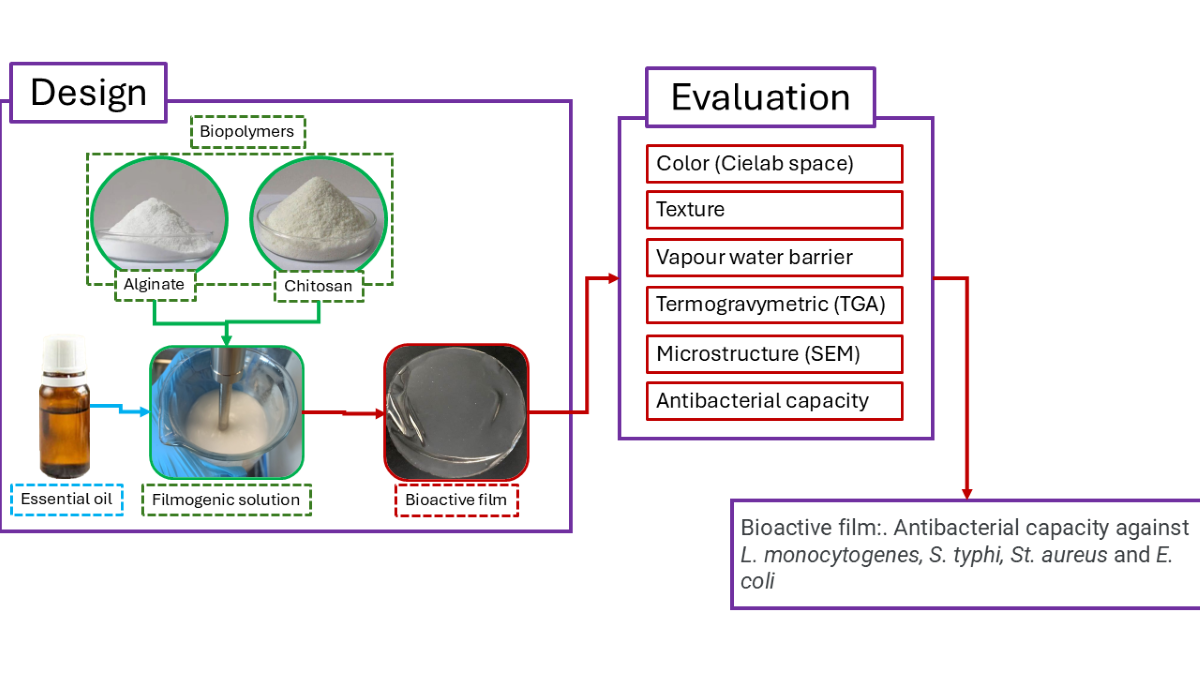

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Determination of Antibacterial Properties of Essential Oils

2.2.2. Preparation of Alginate-Chitosan Films

2.2.3. Preparation of Alginate-Chitosan Films with Antimicrobial Agents

2.2.4. Determination of Physical Properties

2.2.4.1. Film Thickness

2.2.4.2. Color, Yellowness Index, and Whiteness Index

2.2.4.3. Water Vapor Permeability (WVP)

2.2.5. Determination of Mechanical Properties

2.2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.2.7. Thermogravimetry Analysis

2.2.8. Antibacterial Effect of the Alginate-Chitosan Films

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of Essential Oils

3.2. Determination of Physical Properties

3.2.1. Film Thickness

3.2.2. Color Measurement, Yellowness Index (YI), and Whiteness Index (WI)

3.2.3. Water Vapor Permeability

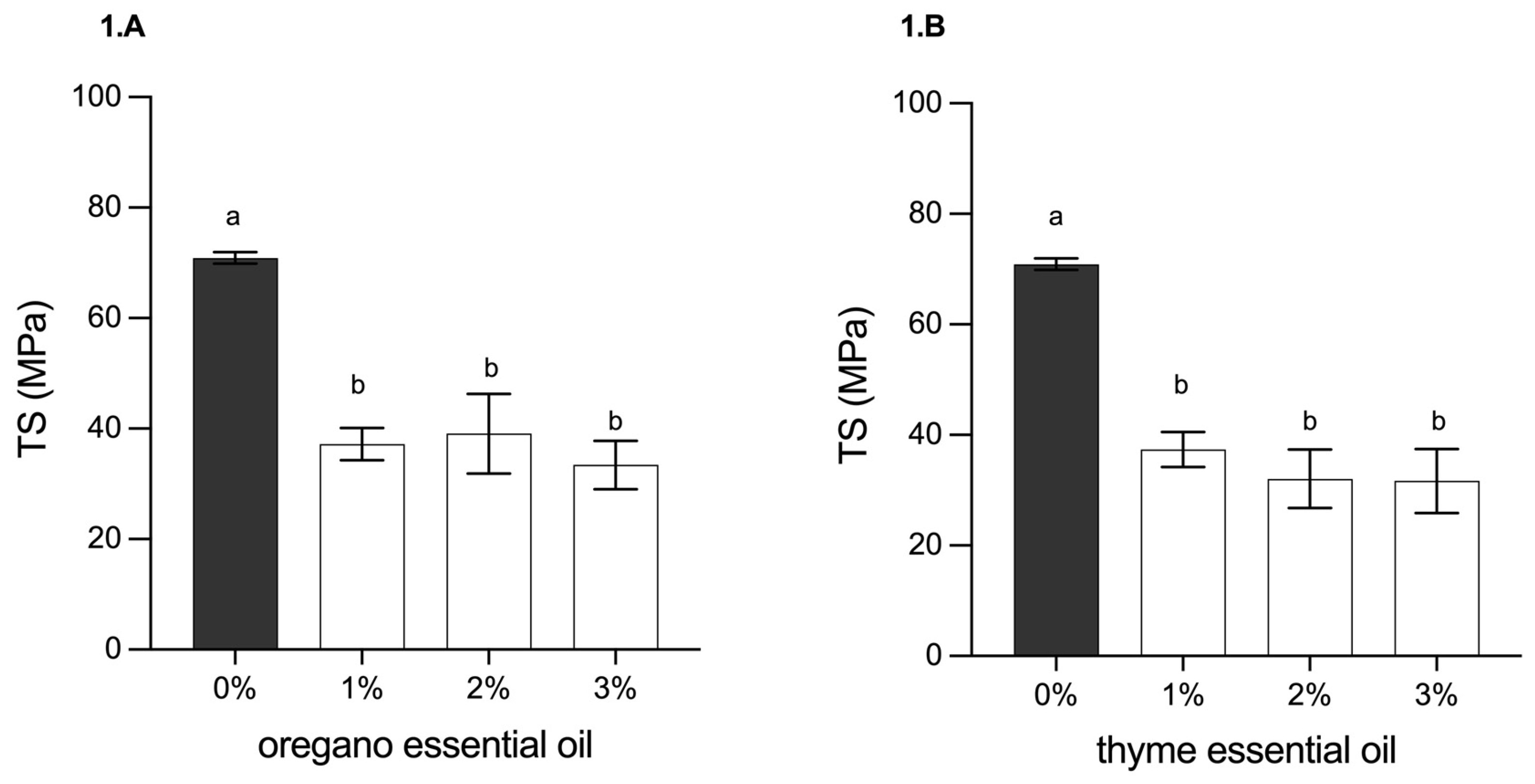

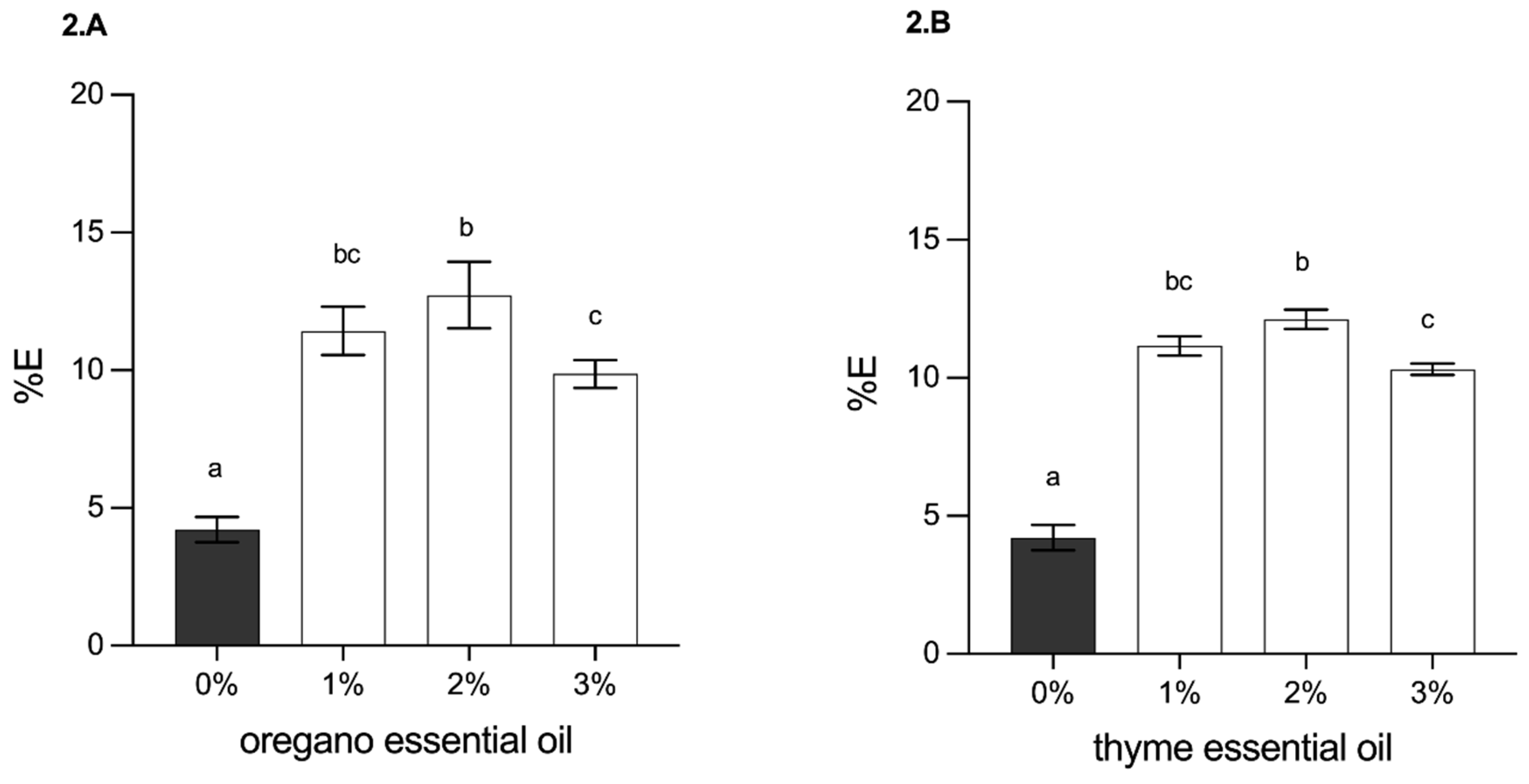

3.2.4. Determination of Mechanical Properties (Tensile Strength and Elongation at Break)

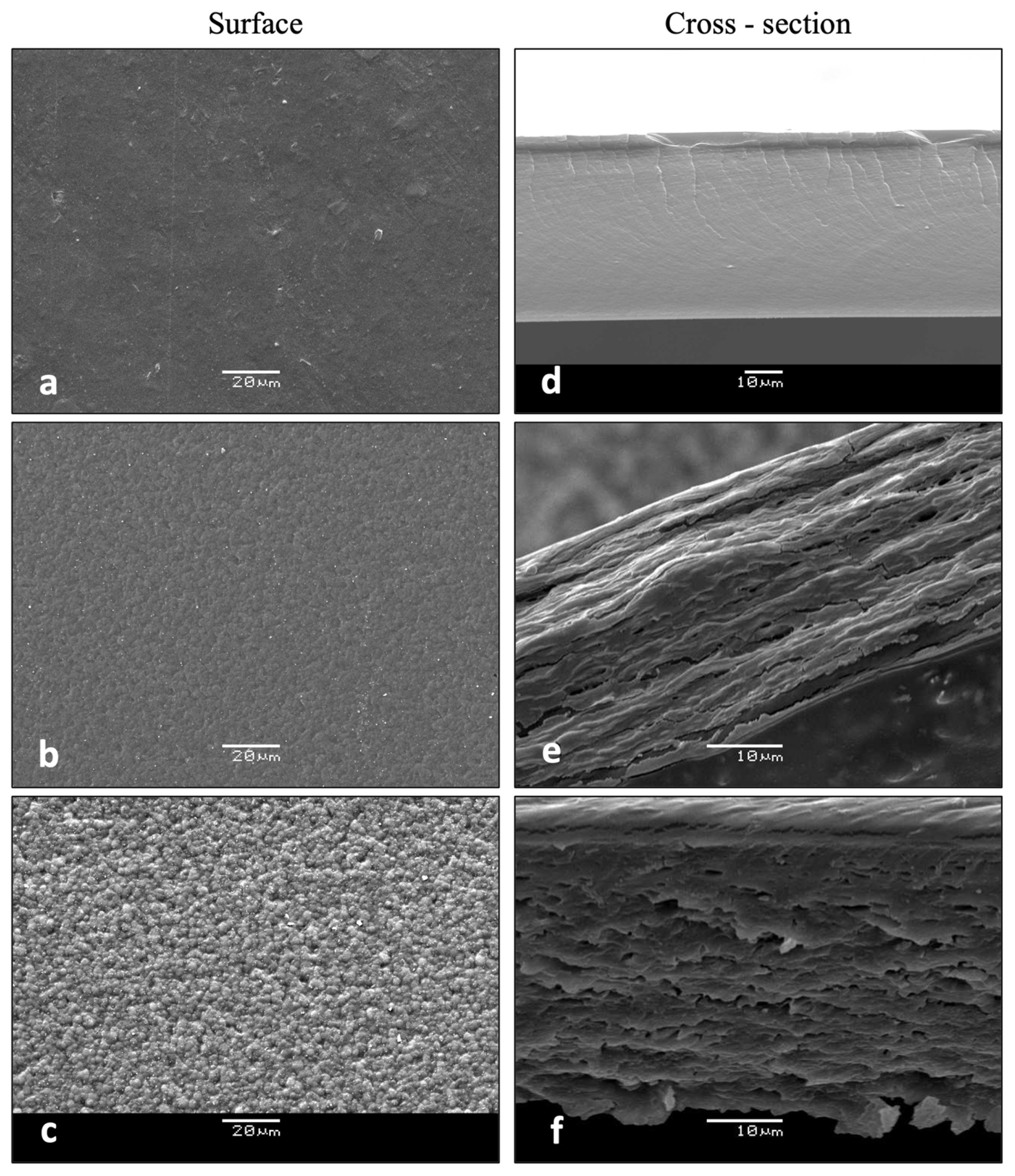

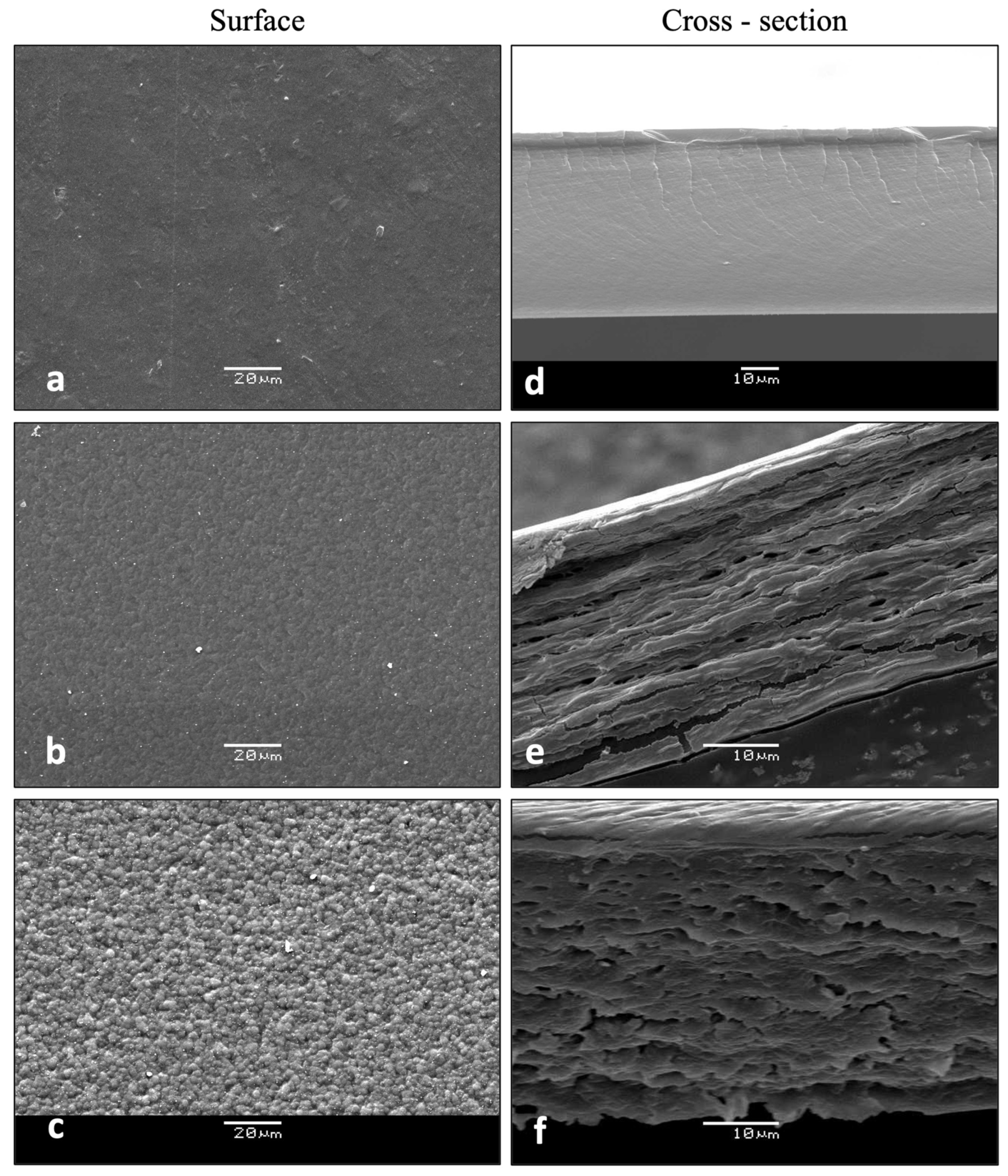

3.2.5. Microstructural Features

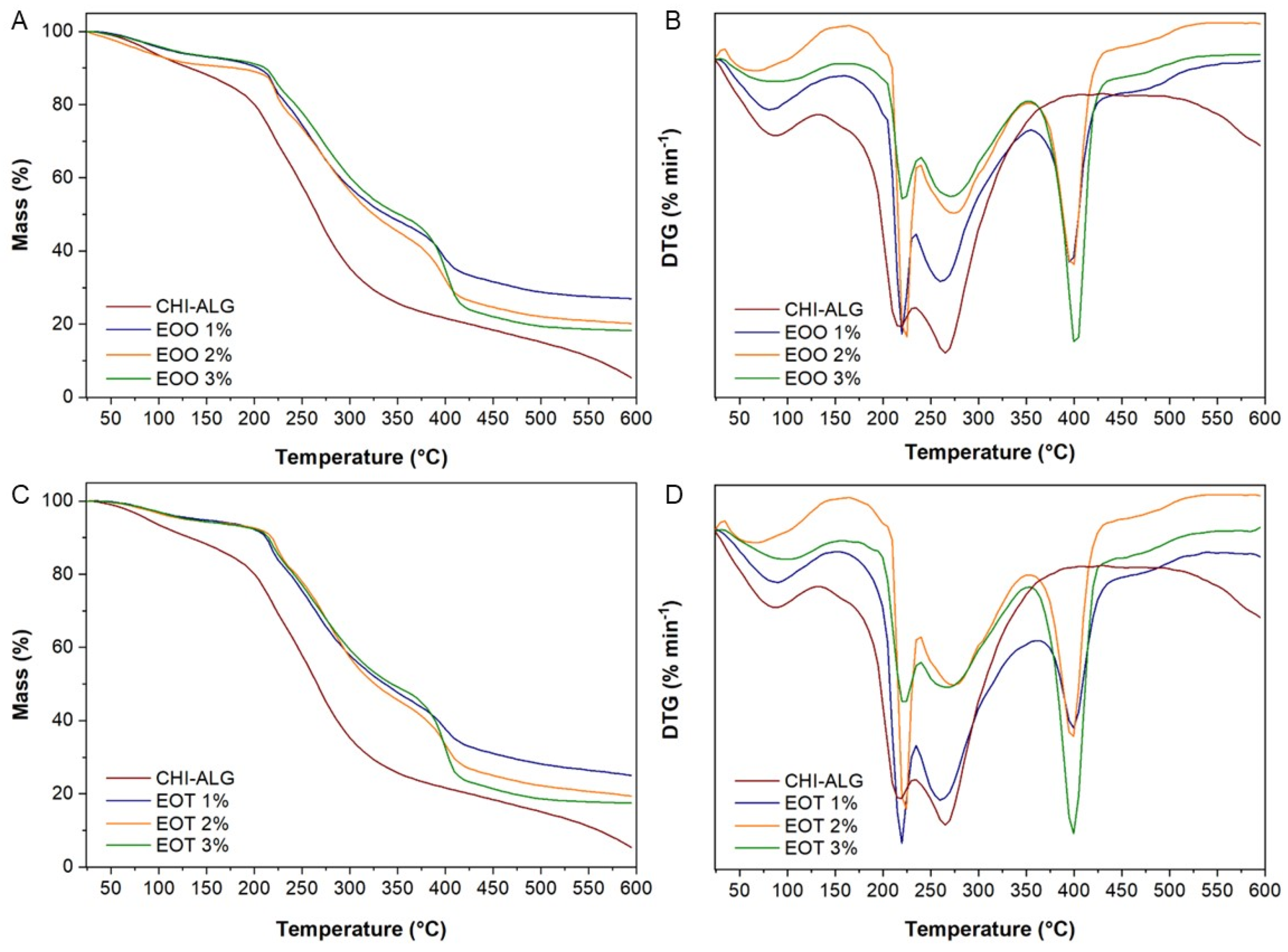

3.2.6. Thermogravimetry Analysis

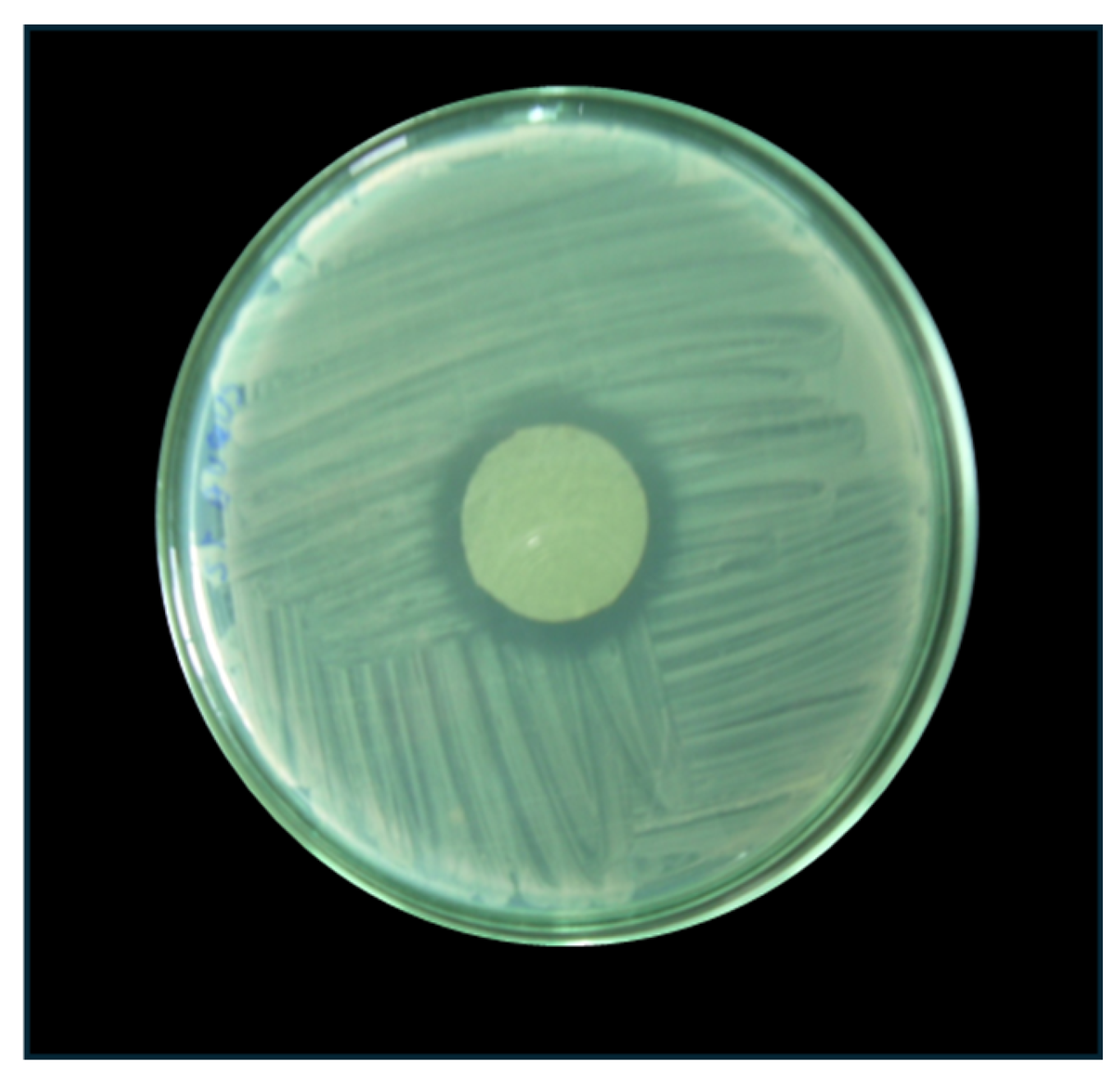

3.2.7. Antibacterial Effect of Alginate-Chitosan Films

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Disclosure Statement

References

- Luchansky, J.B., Barlow, K., Webb, B., Beczkiewicz, A., Merrill, B., Vinyard, B.T., Shane, L.E., Shoyer, B.A., Osoria, M., Campano, S.G., Porto-Fett, A.C.S. (2024). Inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella spp. During Cooking of Country Ham and Fate of L. monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus During Storage of Country Ham Slices. Journal of Food Protection, 87. [CrossRef]

- Movahedi, F., Nirmal, N., Wang, P. Fatemeh, Jin, H., Grøndahl1, L., and Li, L. (2024). Recent advances in essential oils and their nanoformulations for poultry feed. Journal Animal Sciences Biotechnology 15, 110. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro Cerqueira de Oliveira. L., Monteiro de Barros da Cruz Machado, A.C., de Freitas Guimarães Filho, C.E., Almeida Esmerino, E., Andrade Calixto, F.A. Marques de Mesquita, E.F., Holanda Duarte, M.C.K. (2025). Evaluation of the antimicrobial effect of oregano essential oil (Origanum vulgare) on cooked mussels (Perna perna) experimentally contaminated with Escherichia coli and Salmonella Enteritidis. Food Control, Volume 167. [CrossRef]

- Chroho, M., Youssef Rouphael, Y., Petropoulos, S.A. and Bouissane, L. (2024). Carvacrol and Thymol Content Affects the Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Origanum compactum and Thymus zygis Essential Oils. Antibiotics 13, no. 2: 139. [CrossRef]

- Hajibonabi, A., Yekani, M., Sharifi, S., Sadri Nahad, J., Maleki Dizaj, S., Yousef Memar, M. (2023). Antimicrobial activity of nanoformulations of carvacrol and thymol: New trend and applications. OpenNano, 13. [CrossRef]

- Basavegowda N and Baek K.H. (2021). Synergistic antioxidant and antibacterial advantages of essential oils for food packaging applications. Biomolecules, 11(9),1267. [CrossRef]

- Micić, D.; Đurović, S.; Riabov, P.; Tomić, A.; Šovljanski, O.; Filip, S.; Tosti, T.; Dojčinović, B.; Božović, R.; Jovanović, D.; Blagojevićet, S. (2021). Rosemary Essential Oils as a Promising Source of Bioactive Compounds: Chemical Composition, Thermal Properties, Biological Activity, and Gastronomical Perspectives. Foods, 10, 2734. [CrossRef]

- Yemiş G.P, Candoğan K. (2017). Antibacterial activity of soy edible coatings incorporated with thyme and oregano essential oils on beef against pathogenic bacteria. Food Sciences. Biotechnol, 26(4). [CrossRef]

- Amadio C, Farrando S, Zimmermann M. (2019). Effect of chitosan coating enriched with oregano essential oil on the quality of refrigerated meat hamburgers. Rev. Fac. Ciencias Agrar, 51(1), 173–189. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:204810268.

- Kim J.H, Lee E.S, Song K.J, Kim B.M, Ham J.S, Oh M.H. (2022). Development of Desiccation-Tolerant Probiotic Biofilms Inhibitory for Growth of Foodborne Pathogens on Stainless Steel Surfaces. Foods, 11(6), 831. [CrossRef]

- Chawla R, Sivakumar S, Kaur H. (2021). Antimicrobial edible films in food packaging: Current scenario and recent nanotechnological advancements- a review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl, 2,100024. [CrossRef]

- Benavides, S., Mariotti-Celis, M.S., Paredes, M.J.C., Parada, J.A., Franco, W. V., 2021. Thyme essential oil loaded microspheres for fish fungal infection: microstructure, in vitro dynamic release and antifungal activity. J. Microencapsul. 38, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, V., Ranjha, R., Gupta, A.K., 2023. Polymeric encapsulation of anti-larval essential oil nanoemulsion for controlled release of bioactive compounds. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 150, 110507. [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.Y., Ahmad Rafiee, A.R., Leong, C.R., Tan, W.N., Dailin, D.J., Almarhoon, Z.M., Shelkh, M., Nawaz, A., Chuah, L.F., 2023. Development of sodium alginate-pectin biodegradable active food packaging film containing cinnamic acid. Chemosphere 336, 139212. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Wu X, Chen J, He J. (2021). Effects of cinnamon essential oil on the physical, mechanical, structural and thermal properties of cassava starch-based edible films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol, 184, 574–583. [CrossRef]

- Sharma S, Barkauskaite S, Jaiswal A.K, Jaiswal S. (2021). Essential oils as additives in active food packaging. Food Chem, 343, 128403. [CrossRef]

- Azadbakht E, Maghsoudlou Y, Khomiri M, Kashiri M. (2018). Development and structural characterization of chitosan films containing Eucalyptus globulus essential oil: Potential as an antimicrobial carrier for packaging of sliced sausage. Food Packag. Shelf Life, 17(2018), 65–72. [CrossRef]

- Chawla R, Sivakumar S, Kaur H. (2021). Antimicrobial edible films in food packaging: Current scenario and recent nanotechnological advancements- a review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl, 2(2021),100024. [CrossRef]

- Moeini A., Germann N., Malinconico M., Santagata G. (2021). Formulation of secondary compounds as additives of biopolymer-based food packaging: A review, Trends in Food Science & Technology, 114(1), 342-354. [CrossRef]

- Gan H, Lv M, Lv C, Fu Y, Ma H. (2021). Inhibitory effect of chitosan-based coating on the deterioration of muscle quality of Pacific white shrimp at 4°C storage. J. Food Process. Preserv, 45(2), e15167. [CrossRef]

- Benavides S, Cortés P, Parada J, Franco W. (2016). Development of alginate microspheres containing thyme essential oil using ionic gelation. Food Chem. 204(2016), 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Pan J, Li Y, Chen K, Zhang Y, Zhang H. (2021). Enhanced physical and antimicrobial properties of alginate/chitosan composite aerogels based on electrostatic interactions and noncovalent crosslinking. Carbohydr. Polym, 266, 118102. [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Khorrami N, Radi M, Amiri S, Abedi E, McClements D.J. (2022). Fabrication, characterization, and performance of antimicrobial alginate-based films containing thymol-loaded lipid nanoparticles: Comparison of nanoemulsions and nanostructured lipid carriers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol, 207, 801–812. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:247831372.

- Gedikoğlu A, Sökmen M, Çivit A. (2019). Evaluation of Thymus vulgaris and Thymbra spicata essential oils and plant extracts for chemical composition, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties. Food Sci. Nutr, 7(5), 1704–1714. [CrossRef]

- Kiehlbauch J.A, Hannett G.E, Salfinger M, Archinal W, Monserrat C, Carlyn C. (2000). Use of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guidelines for disk diffusion susceptibility testing in New York State Laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol, 38, 3341–3348. [CrossRef]

- Lijun Sun, Jiaojiao Sun, Lei Chen, Pengfei Niu, Xingbin Yang, Yurong Guo (2017). Preparation and characterization of chitosan film incorporated with thinned young apple polyphenols as an active packaging material, Carbohydrate Polymers, 163, Pages 81-91. [CrossRef]

- Benavides S, Villalobos-Carvajal R, Reyes J.E. (2012). Physical, mechanical and antibacterial properties of alginate film: Effect of the crosslinking degree and oregano essential oil concentration. J. Food Eng, 110(2012), 232–239. [CrossRef]

- Jinman He, Wanli Zhang, Gulden Goksen, Mohammad Rizwan Khan, Naushad Ahmad, Xinli Cong (2024). Functionalized sodium alginate composite films based on double-encapsulated essential oil of wampee nanoparticles: a green preservation material, Food Chemistry: X, Volume 24. [CrossRef]

- Łopusiewicz Ł, Drozlowska E, Trocer P, Kostek M, Śliwiński M, Henriques M.H.F, Bartkowiak A, Sobolewski P. (2020). Whey protein concentrate/isolate biofunctional films modified with melanin from watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) seeds. Materials (Basel), 13(17), 3876. [CrossRef]

- Mchugh H, Bustillos A, Krochta J. (1993). Hydrophilic Edible Films: Modified Procedure for Water Vapor Permeability and Explanation of Thickness Effects. J. Food Sci, 58(4), 899–903. [CrossRef]

- Gennadios, A., Hanna, M.A., Kurth, L.B., 1997. Application of edible coatings on meats, poultry, and seafood. Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft Und-Technologie 30, 337–350. [CrossRef]

- Chen M.H., Yeh G.H., Chiang B.H. (1996) Antimicrobial and physicochemical properties of methylcellulose and chitosan films containing a preservative. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, (20), pp. 379-390. [CrossRef]

- Li Y. xin, Erhunmwunsee F, Liu M, Yang K, Zheng W, Tian J. (2022). Antimicrobial mechanisms of spice essential oils and application in food industry. Food Chem, 382, 132312. [CrossRef]

- Yemiş G.P, Candoğan K. (2017). Antibacterial activity of soy edible coatings incorporated with thyme and oregano essential oils on beef against pathogenic bacteria. Food Sci. Biotechnol, 26(4),1113–1121. [CrossRef]

- Jouki M, Yazdia F.T, Mortazavia S.A, Koocheki A, Khazaei N. (2014). Effect of quince seed mucilage edible films incorporated with oregano or thyme essential oil on shelf life extension of refrigerated rainbow trout fillets. Int. J. Food Microbiol, 174, 88–97. [CrossRef]

- Irianto H.E, Marpaung D.B, Ggiyatmi Fransiska D, Basriman I. (2021). Anti-bacterial Activity of Alginate Based Edible Coating Solution Added with Lemongrass Essential Oil against Some Pathogenic Bacteria. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci, 934. [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri F.M, Martelli S.M, Caon T, Velasco J.I, Buontempo R.C, Bilck A.P, Innocentini Mei L.H. (2018). The effect of fatty acids on the physicochemical properties of edible films composed of gelatin and gluten proteins. LWT—Food Sci. Technol, 87,293–300. [CrossRef]

- Vieira T.M, Moldão-Martins M, Alves V.D. (2021). Design of chitosan and alginate emulsion-based formulations for the production of monolayer crosslinked edible films and coatings. Foods, 10(7),1654. [CrossRef]

- Tan L.F, Elaine E, Pui L.P, Nyam K.L, Yusof Y.A. (2021). Development of chitosan edible film incorporated with Chrysanthemum morifolium essential oil. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment, 20(1), 55–66. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:231612621.

- Kporwodu., F., Garcia, C.V., Shin, G.H., Kim, J.T. (2018). Alginate biocomposite films incorporated with cinnamon essential oil nanoemulsions: Physical, mechanical, and antibacterial properties. Int. J. Polym. Sci, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-González L, González-Martínez C, Chiralt A, Cháfer M. (2010). Physical and antimicrobial properties of chitosan-tea tree essential oil composite films. J. Food Eng, 98(4), 443–452. [CrossRef]

- Sharma S, Barkauskaite S, Duffy B, Jaiswal A.K, Jaiswal S. (2020). Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity of Biodegradable Active Packaging Enriched with Clove and Thyme Essential Oil for Food Packaging Application. Foods, 9(8), 1117. [CrossRef]

- Radev R.S, Dimitrov G.A. (2017). Water vapor permeability of edible films with different composition. Sci. Work. Univ. Food Technol, 64, 96–102. https://uft-plovdiv.bg/site_files/file/scienwork/scienworks_2017/docs/2-15.pdf.

- Moeini A, Cimmino A, Masi M, Evidente A, Van Reenen A. (2020) The incorporation and release of ungeremine, an antifungal Amaryllidaceae alkaloid, in poly(lactic acid)/poly(ethylene glycol) nanofibers. J Appl Polym Sci. 137:e49098. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla J, Atarés L, Vargas M, Chiralt A. (2012). Effect of essential oils and homogenization conditions on properties of chitosan-based films. Food Hydrocoll, 26(2012), 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Karami P, Zandi M, Ganjloo A. (2022). Evaluation of physicochemical, mechanical, and antimicrobial properties of gelatin-sodium alginate-yarrow (Achillea millefolium L.) essential oil film. J. Food Process. Preserv, 46(7),1–14. [CrossRef]

- Cofelice M, Cuomo F, Chiralt A. (2019). Alginate films encapsulating lemongrass essential oil as affected by spray calcium application. Colloids and Interfaces, 3(58), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Nur Hanani Z.A, Aelma Husna A.B. (2018). Effect of different types and concentrations of emulsifier on the characteristics of kappa-carrageenan films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol, 114, 710–716. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Ma Q, Critzer F, Davidson P.M, Zhong Q. (2015). Physical and antibacterial properties of alginate films containing cinnamon bark oil and soybean oil. LWT—Food Sci. Technol, 64(1), 423–430. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Barjas, G., Jimenez, R., Romero, R., Valdes, O., Nesic, A., Hernández-García, R., Neira, A., Alejandro-Martín, S., de la Torre, A. F. (2023). Value-added long-chain aliphatic compounds obtained through pyrolysis of phosphorylated chitin. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 238, 124130. [CrossRef]

- Conzatti, G., Faucon, D., Castel, M., Ayadi, F., Cavalie, S., Tourrette, A. (2017). Alginate/chitosan polyelectrolyte complexes: A comparative study of the influence of the drying step on physicochemical properties. Carb. Polym. 72, 142-151 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, G., Paredes, J. C., Cabrera, G., Casals, P. (2002). Synthesis and characterization of chitosan alkyl carbamates. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 86(11), 2742-2747. [CrossRef]

- Kulig, D.; Zimoch-Korzycka, A.; Jarmoluk, A.; Marycz, K. (2016). Study on Alginate–Chitosan Complex Formed with Different Polymers Ratio. Polymers, 8 (5), 167. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zhang, C-J., Zhao, J-C., Guo, Y., Zhu, P., Wang, D-Y. (2016). Bio-based barium alginate film: Preparation, flame retardancy and thermal degradation behavior, Carbohydrate Polymers 139(30), 106-114 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Becheran-Maron L., Peniche C., Arguelles-Monal W. (2004). Study of the inter-polyelectrolyte reaction between chitosan and alginate: influence of alginate composition and chitosan molecular weight. Int. J. Biol. Macromol; 34: 127–133. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Ren, Z., Li, H., Xue, Y., Zhang, M., Li, R., & Liu, P. (2024). Preparation and sustained-release of chitosan-alginate bilayer microcapsules containing aromatic compounds with different functional groups. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 271 (2), 132663. [CrossRef]

- Qian-Jun Shen, Jinyue Sun, Jia-Neng Pan, Ting Yu, Wen-Wen Zhou (2024) Synergistic antimicrobial potential of essential oil nanoemulsion and ultrasound and application in food industry: A review. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, Volume 98. [CrossRef]

| Strains | Antibacterial Parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/mL) | MBC (mg/mL) | |||

| EOT | EOO | EOT | EOO | |

| E. coli. | 1.39±0.03a | 0.69±0.03b | 2.78±0.04a | 2.78±0.04a |

| S. enterica | 1.39±0.03a | 0.69±0.03b | 5.56±0.04ª | 2.78±0.04b |

| S. aureus | 0.69±0.03a | 0.35±0.03b | 2.78±0.04a | 1.39±0.04b |

| L. monocytogenes | 0.35±0.03a | 0.17±0.03b | 2.78±0.04a | 1.39±0.04b |

| Essential Oil Type | %EO | Thickness (x10-2 mm) |

Color (CIELAB Space) | WVP (g/m s Pa)x10-9 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | ΔE | YI | WI | ||||

| Control | 0.0 | 3.49±0.37a | 98.5±0.17a | -1.52±0.18a | 5.47±0.18a | 4.26±0.21a | 7.94±0.27a | 94.12±0.20a | 4.03±0.47ab |

| EOO | 1.0 | 3.82±0.07a | 88.3±0.20b | -3.46±0.22b | 11.69±0.16b | 12.1±0.11b | 18.9±0.23b | 83.10±0.10b | 3.19±0.15a |

| 2.0 | 3.77±0.12a | 87.2±0.47c | -3.56±0.08b | 11.65±0.13b | 13.0±0.37c | 19.1±0.18b | 82.37±0.29c | 2.47±1.00b | |

| 3.0 | 3.79±0.09a | 86.4±0.09c | -3.52±0.15b | 11.63±0.07b | 13.6±0.06c | 19.2±0.11b | 81.83±0.05c | 1.80±0.39c | |

| EOT | 1.0 | 3.78 ± 0.05a | 87.8±0.10b | 3.35±0.14b | 11.52±0.07b | 12.3±0.06b | 18.7±0.11b | 82.94±0.04b | 3.04±0.35a |

| 2.0 | 3.82 ± 0.08a | 86.8±0.04c | -3.70±0.03c | 11.64±0.03b | 13.3±0.04c | 19.1±0.05c | 82.05±0.04c | 2.45±0.16a | |

| 3.0 | 3.80 ± 0.05a | 86.3±0.03d | -3.43±0.02b | 11.96±0.14c | 13.9±0.05d | 19.7±0.22d | 81.54±0.07d | 1.65±0.69b | |

| Sample | Temperature (°C) | Weight Loss (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Peak | End | ||

| Chitosan (CHI) | 24 | 66 | 135 | 3.8 |

| 251 | 310 | 402 | 50.4 | |

| Alginate (ALG) | 25 | 69 | 185 | 10.6 |

| 191 | 244 | 266 | 24.0 | |

| 266 | 284 | 319 | 10.9 | |

| 319 | 399 | 544 | 11.0 | |

| CHI-ALG | 30 | 87 | 133 | 10.1 |

| 134 | 216 | 234 | 24.6 | |

| 235 | 265 | 385 | 42.4 | |

| EOT 1% | 24 | 90 | 156 | 6.4 |

| 179 | 220 | 235 | 12.9 | |

| 236 | 260 | 360 | 34.9 | |

| 361 | 400 | 442 | 14.7 | |

| 443 | 477 | 525 | 4.2 | |

| EOT 2% | 26 | 73 | 157 | 5.9 |

| 195 | 225 | 239 | 11.1 | |

| 240 | 274 | 351 | 37.0 | |

| 352 | 399 | 443 | 18.8 | |

| 444 | 476 | 523 | 4.0 | |

| EOT 3% | 28 | 102 | 156 | 5.9 |

| 204 | 223 | 240 | 11.4 | |

| 241 | 267 | 352 | 41.3 | |

| 353 | 399 | 443 | 27.5 | |

| 444 | 477 | 524 | 3.6 | |

| EOO 1% | 24 | 81 | 149 | 7.0 |

| 205 | 219 | 235 | 10 | |

| 236 | 261 | 355 | 32.2 | |

| 356 | 396 | 438 | 15.5 | |

| 439 | 476 | 523 | 4.2 | |

| EOO 2% | 24 | 70 | 145 | 9.2 |

| 205 | 224 | 239 | 12.0 | |

| 240 | 273 | 353 | 32.0 | |

| 354 | 399 | 438 | 19.2 | |

| 439 | 476 | 523 | 4.0 | |

| EOO 3% | 26 | 83 | 149 | 6.8 |

| 204 | 221 | 241 | 18.3 | |

| 242 | 273 | 353 | 30.9 | |

| 354 | 400 | 438 | 26.8 | |

| 439 | 476 | 522 | 3.8 | |

| Concentration (%) | Inhibition Zone by Type of Essential Oil (Diameter in mm) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | S. enterica | S. aureus | L. monocytogenes | |||||

| EOO | EOT | EOO | EOT | EOO | EOT | EOO | EOT | |

| 0.0 | 0Aa | 0Aa | 0Aa | 0Aa | 0Aa | 0Aa | 0Aa | 0Aa |

| 1.0 | 26±1.2Ba | 30±0.9Bb | 22±0.2Ba | 26±0.8Ba | 24±1.4Ba | 27±0.09Ba | 27±1.8Ba | 40±0.9Bc |

| 2.0 | 25±0.9Ba | 39±1.5Cb | 28±1.6Ca | 28±2.1Ba | 30±0.1Ba | 38±0.13Cb | 37±1.3Cb | 46±1.5Bc |

| 3.0 | 39±1.3Ca | 41±1.3Ca | 35±0.8Da | 36±0.9Ca | 43±1.2Ca | 49±0.09Db | 49±1.3Db | 55±1.3Cb |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).