1. Introduction

Gyrovirus galga1 (GyVg1) is a small, nonenveloped, single-stranded circular DNA virus with a genome length of approximately 2.4 kb that belongs to the genus

Gyrovirus of the

Anelloviridae family [

1]. In 2011, Rijsewijk et al. amplified and sequenced GyVg1 DNA from serum samples of diseased chickens in southern Brazilian poultry farms using phi29 DNA polymerase. The resulting genome shared organizational similarities with chicken anemia virus (CAV), marking the first identification of a CAV-related virus, provisionally designated Avian gyrovirus 2 (AGV2) [

2]. Concurrently, Sauvage et al. identified the first human gyrovirus associated with CAV in a skin swab sample from a healthy individual, this virus was named human gyrovirus (HGyV) [

3]. Later Chu et al. revealed >92% nucleotide sequence identity between HGyV and AGV2, with no discernible evolutionary divergence between avian and human isolates [

4], which indicated that AGV2 and HGyV are essentially the same virus. As of 2025, 15 species of gyrovirus have been identified [

5]. Kraberger et al. defined 69% as the threshold for the VP1 nucleotide sequence pairwise identity value; according to this threshold, they established 9 new species classified as new gyroviruses and adopted the binomial “genus + free appellation” species naming method proposed by Siddell [

6]. The original AGV2 was officially renamed GyVg1 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) [

7].

GyVg1 was first identified in Brazil in 2011 and is the second member of the genus Gyrovirus [

2]. Molecular epidemiological studies reveal its global distribution across Asia (China, Japan, Vietnam), South America (Brazil), Europe (France, Netherlands, Hungary, Italy), and Africa (South Africa), primarily linked to chickens but also found in feces of wild birds, humans, domestic cats, dogs, ferrets, and zoo animals [

4,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], suggesting a risk of cross-host transmission [

13,

14]. Regional prevalence varies markedly, South America reveals higher rates in poultry, reaching 60.4%~90.7% in Brazil and 60.32% in the southern Netherlands [

13,

14]. Asia reveals lower rates, with 1.2%~32.1% in Chinese chicken flocks [

14,

16,

17,

18] and 20.63% in symptomatic flocks in northern Vietnam [

19]. Reports from Africa and Europe predominantly involve human and ferret [

9,

10,

19,

20]. Epidemiological surveillance indicates that chicken co-infections are prevalent (82% of cases), with multi-pathogen interactions driving elevated morbidity and mortality rates [

21,

22]. These infections manifest as hemorrhagic lesions, gastric erosion, cranial edema, and systemic inflammation [

15,

21], directly linking to severe economic losses in poultry production, and the absence of commercial vaccines and antiviral therapies further amplifies this burden.

Current diagnostic challenges for GyVg1 stem from the absence of in vitro culture systems for viral isolation and standardized immunological assays. Molecular detection, particularly PCR-based methods, remains the primary diagnostic tool. However, PCR’s reliance on thermal cycling, prolonged runtime (~hours), and requirement for specialized laboratory equipment limit its field applicability. Recombinase-aided amplification (RAA), an emerging isothermal nucleic acid amplification technology, overcomes these limitations by enabling rapid target amplification (30 min) at constant temperatures (37°C~42°C) without thermal cyclers [

23,

24]. Our lab previously developed a 20-minute real-time fluorescent RAA assay for GyVg1 [

25], however, the binding of primers or probes to the target sequence can still tolerate a certain degree of mismatch, and there is no thermal cycle to prevent binding between primers, so eliminating nonspecific amplification is difficult. The target specificity and nuclease cleavage activity of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) systems allow CRISPR/Cas technology to achieve attomolar sensitivity and single-nucleotide specificity [

26]. Therefore, in this study, a CRISPR/Cas system and RAA technology were combined to construct a novel detection platform that eliminates nonspecific signals while maintaining field compatibility. Using the RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a framework, we established two visual detection assays for GyVg1: RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a combined with fluorescence (RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a‒FQ) and RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a combined with lateral flow strips (RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a‒LFS).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

4 GyVg1 strains were GX-202307-G1 (Genbank ID: OR921081), GX-202308-B (Genbank ID: PV165310), GX-202403-t8 (Genbank ID.: PV165317) and GX-202408-24 (Genbank ID: PV165321) (see

Table S1). The DNA materials of 13 closely related pathogens, including gyrovirus homsa1 (GyH1), chicken infectious anemia virus (CIAV), fowl adenovirus 4 (FAdV4), H9 subtype avian influenza virus (H9-AIV), Newcastle disease virus (NDV), avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV), chicken parvovirus (ChPV), avian leukosis virus (ALV), chicken astrovirus (CAstV), avian nephritis virus (ANV),

Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG) and

Mycoplasma synoviae (MS) were preserved in the laboratory and used to evaluate the specificity of the assays. Additionally, 192 clinical specimens (120 oropharyngeal/cloacal swabs; 72 tissue samples) were collected from live poultry markets and small-scale farms in Guangxi, China, and were frozen at −80°C.

2.2. Primer and crRNA Design

Three candidate crRNAs (Editgene, Guangzhou, China) were designed and screened to identify the optimal crRNA for CRISPR/Cas12a system establishment. All available GyVg1 sequences were retrieved from the NCBI database and subjected to multiple sequence alignment using the BioEdit program of DNASTAR software to identify conserved regions. The target locus was defined by the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM: 5′-TTTN-3′; N = A/C/G) on conserved sequence or its complementary strand. A 20-bp spacer sequence downstream of the PAM was selected for crRNA design, with the first 8 nucleotides designated as the seed region requiring 100% conservation [

27]. Each crRNA consists of a direct repeat sequence and a spacer sequence; Doudna’s research group previously obtained the optimal direct repeat sequence (5’-UAAUUUCUACUAAGUGUAGAU-3’) from which the crRNA sequences were determined [

28].

Three upstream and three downstream primers (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) were designed to flank the crRNA target region, with a primer size of 28–32 bp and an amplicon size of approximately 300 bp. The primer sequences were designed to avoid pairing with the crRNA sequences. Finally, a plasmid-specific pair flanking the amplicon termini were designed to enable quantification of template copy numbers. FQ-ssDNA and FB-ssDNA reporter were purchased by Editgene Biotech (Guangzhou, China) All sequences are shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Genomic DNA Extraction and Plasmid Standard Generation

The collected swab and tissue samples were presoaked with PBS, squeezed or ground, and 200 µL viral supernatant aliquoted into sample wells of 32-well plates using prepackaged viral RNA/DNA extraction kit (Biovet Biotech, Tianjin, China). Then executive Automated purification via NPA-32P nucleic acid extraction instrument (Bioer Tech, Hangzhou, China). Finally, genomic DNA aspiration completed within 18 min from designated nucleic acid wells.

Using purified DNA as the template, PCR amplification was performed with the primers GyVg1-F/GyVg1-R and Tks Gflex™ DNA Polymerase (Takara, Dalian, China). The PCR products were verified by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by purification of the target DNA fragment. The purified fragment was ligated into the TOPO vector (Tolo Biotech, Shanghai, China) and transformed into E.coli DH5α (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) via heat-shock treatment. Positive clones were screened, and the recombinant plasmid was extracted and designated as the plasmid standard TOPO-S1. The plasmid concentration was calculated and stored at −20°C.

2.4. Primer and crRNA Screening

We screen primers and crRNAs in accordance with the instructions of the RAA kit (ZhuangBo Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanning, China) and LbCas12a Nuclease (Editgene,Guangzhou, China). Amplification premix was prepared by combining lyophilized enzyme pellets with 25 μL Buffer A, 13.5 μL RNase-free water, and 2 μL each of forward/reverse primers (10 μM) in a reaction tube. After adding 5 μL template DNA to the tube base and 2.5 μL Buffer B to the cap, the 50 μL reaction system underwent three rapid inversions followed by brief centrifugation. Amplification proceeded at 39°C for 30 min using a metal-block thermal cycler.

Cleavage mixture containing 3 µL of 10× cleavage buffer, 3 µL of LbCas12a nuclease (1 µM), 2 µL of crRNA (500 nM), 6 µL of FQ-ssDNA reporter (2 µM) and 15 µL RNase-free water was pre-incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Subsequently, 3 μL RAA amplicon was transferred to the cap-containing reaction vessel, followed by immediate vortex mixing, centrifugation, and real-time fluorescence monitoring at 37°C using a QuantStudio5 qPCR instrument (Thermo Fisher, Massachusetts, USA). Fluorescence intensity was recorded every 30 s over 20 min to quantify trans-cleavage activity.

2.5. Optimization of the RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a Reaction

Using the standard RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a framework with plasmid standard TOPO-S1 (positive control) and RNase-free water (negative control), we systematically refined reaction parameters through fluorescence-based kinetic analysis. Temperature gradients (37°C, 38°C, 39°C, 40°C, 41°C and 42°C) were methodically evaluated for both amplification and trans-cleavage steps to establish optimal thermal conditions. Component concentrations of the primers (200 nM, 300 nM, 400 nM, 500 nM, and 600 nM), crRNA (8.3 nM, 16.7 nM, 25 nM, 33 nM, 41.3 nM, 50 nM, and 58 nM, based on the assumption that the concentration of the LbCas12a nuclease in the standard system is 33 nM), and FQ-ssDNA reporter (200 nM, 300 nM, 400 nM, 500 nM, and 600 nM) were sequentially optimized. Final validation employed FB-ssDNA reporter (50 nM, 100 nM, 200 nM, 300 nM, 400 nM, and 500 nM) cross-validated via CRISPR lateral flow strips (Tolo Biotech, Shanghai), with optimal concentrations determined by fluorescence) and test/control (T/C) line intensity.

2.6. Sensitivity and Specificity Evaluation

To assess the sensitivity of the RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a system, positive plasmids spanning seven orders of magnitude (2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 500, and 5000 copies/µL) were analysed using RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a-FQ method, and real-time fluorescence data and UV-visualized reaction products were recorded. While for RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS method, tested across a continuous plasmid gradient (5.0×100~5.0×108 copies/µL), achieved a sensitivity threshold validated by lateral flow strip T/C line intensity.

Specificity evaluation included screening 13 avian pathogens (GyH1, CIAV, FAdV4, H9-AIV, NDV, IBV, IBDV, ChPV, ALV, ANV, CAstV, MG, MS) mimicking GyVg1-associated symptoms or co-prevalent infections. The results were validated by real-time fluorescence curves, UV-induced product fluorescence, and lateral flow strip T/C line readouts.

2.7. Practical Application in Clinical Samples

The RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a‒FQ and RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a‒LFS methods established in this study were used to analyse 192 clinical samples collected in the laboratory. The results were compared with those of a qPCR assay [

29] to evaluate the consistency of the three detection methods.

3. Results

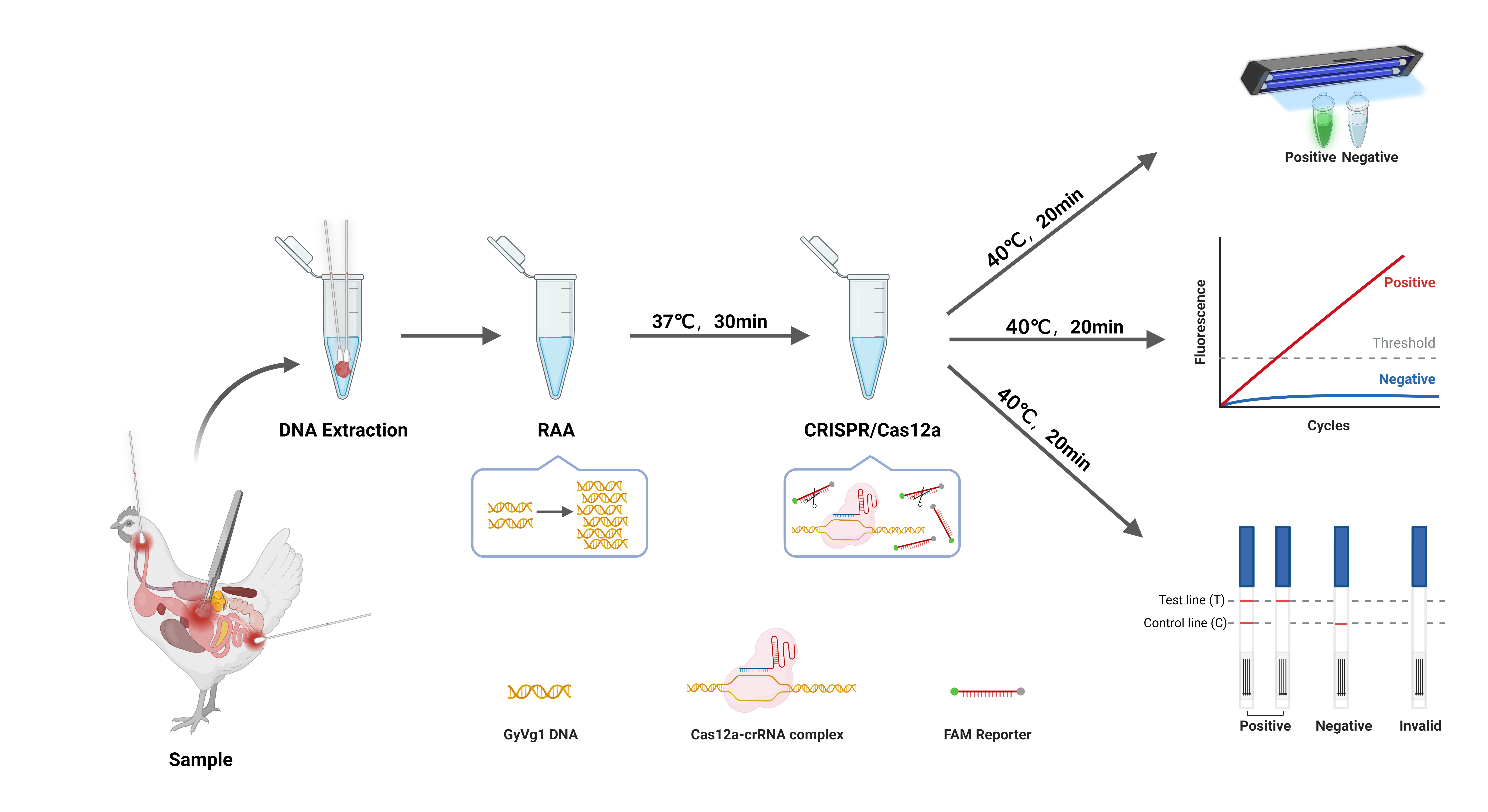

3.1. Study Protocol

Figure 1 illustrates RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a workflow for GyVg1 detection, enabling rapid, equipment-free pathogen screening. Following nucleic acid extraction, the protocol comprises two core phases. The first is Isothermal Amplification: RAA reaction at 37°C~42°C for 30 min generates sufficient target DNA for downstream CRISPR activation; Then CRISPR-Cas12a Signal Amplification: The Cas12a-crRNA complex binds to target DNA via PAM recognition, triggering collateral ssDNA reporter cleavage. This cascade amplifies fluorescence or lateral flow signals, allowing naked-eye interpretation under UV light or via test strips.

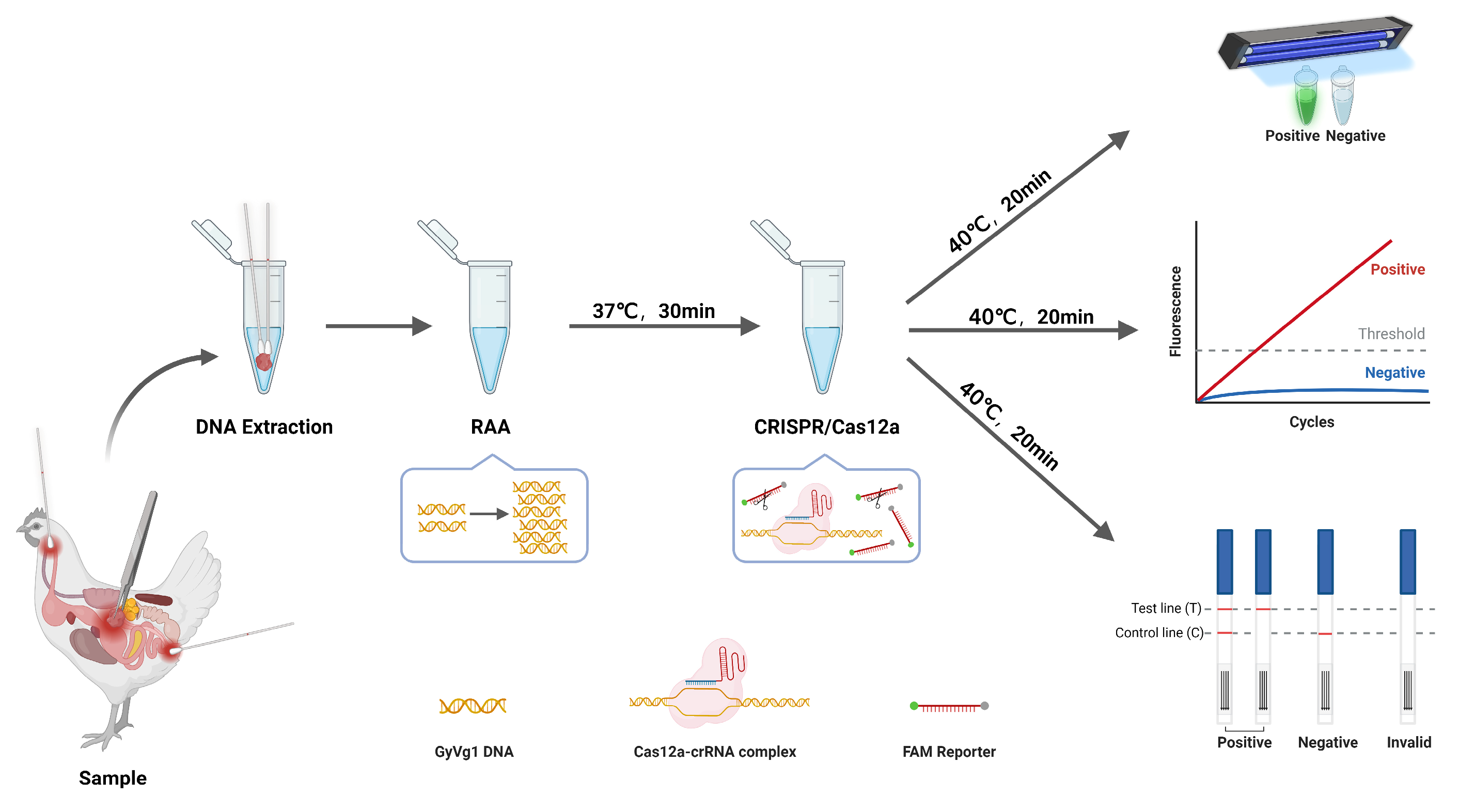

3.2. Standard RAA and the CRISPR/Cas12a System

A systematic screening strategy (3×3×3) was implemented to screen primer-crRNA combinations, comprising 27 experimental conditions paired with matched negative controls (n=54 total), and all reactions underwent 40-cycle real-time CRISPR-Cas12a analysis. Initial screening revealed partial fluorescence activation with crRNA1 and crRNA2 (

Figure 2a,b), while crRNA3 demonstrated universal target responsiveness across all positive groups (

Figure 2c). By contrast, the GyVg1-F3/GyVg1-R3 primer pair coupled with crRNA3 exhibited superior fluorescence and zero false-positive signals in controls (

Figure 2d), validating this combination as the optimal detection system.

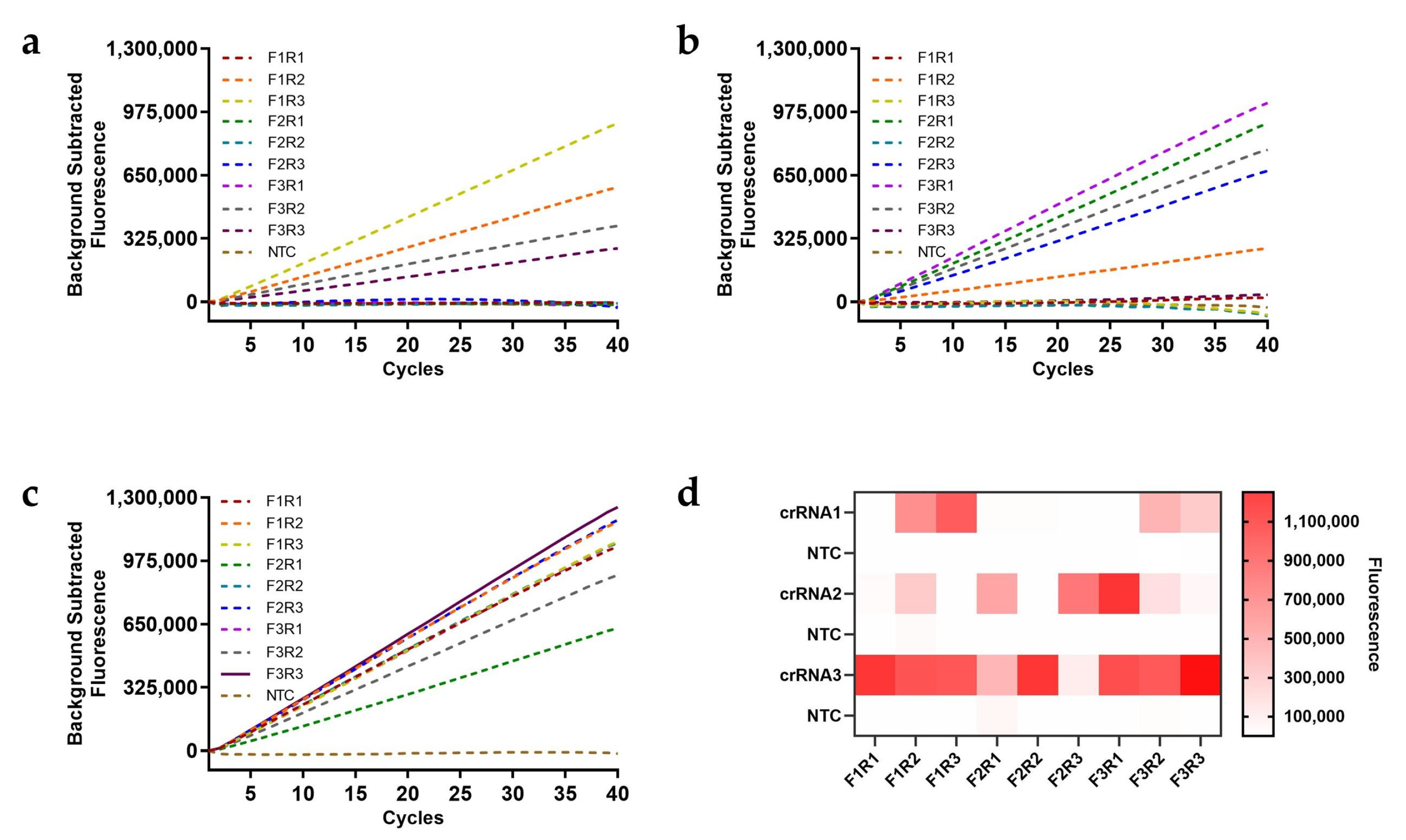

3.3. Ideal Reaction Conditions for RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a

Temperature optimization studies identified 37°C (RAA amplification) and 40°C (Cas12a cleavage) as optimal conditions, delivering maximal fluorescence signal development and reaction efficiency (

Figure 3a,b). Subsequent component optimization revealed in

Figure 2: 500 nM primers (

Figure 3c) and 25 nM crRNA (

Figure 3d) achieved 100% target activation, 500 nM FQ-ssDNA (

Figure 3e) and 300 nM FB-ssDNA (

Figure 3f) maximized fluorescence and T line intensity.

These empirically derived parameters (summarized in

Table 2) define the optimized RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a system for field diagnostics.

3.4. Sensitivity of the RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a Assay

Sensitivity analysis comparing fluorescence (FQ) and lateral flow strip (LFS) readouts revealed distinct detection limits for the RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a platform. As demonstrated in

Figure 3, the RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a-FQ assay achieved attomolar sensitivity with a detection limit of 2 copies/µL (

Figure 4a), while its visual detection limit under UV light reached 10 copies/µL (

Figure 4b). In contrast, the RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS variant exhibited a 250-fold lower sensitivity, requiring 5×10² copies/µL to generate a discernible T-line signal (

Figure 4c). These results highlight the superior analytical performance of fluorescence-based readouts for detection and underscore the practicality of LFS for rapid field applications where moderate sensitivity suffices.

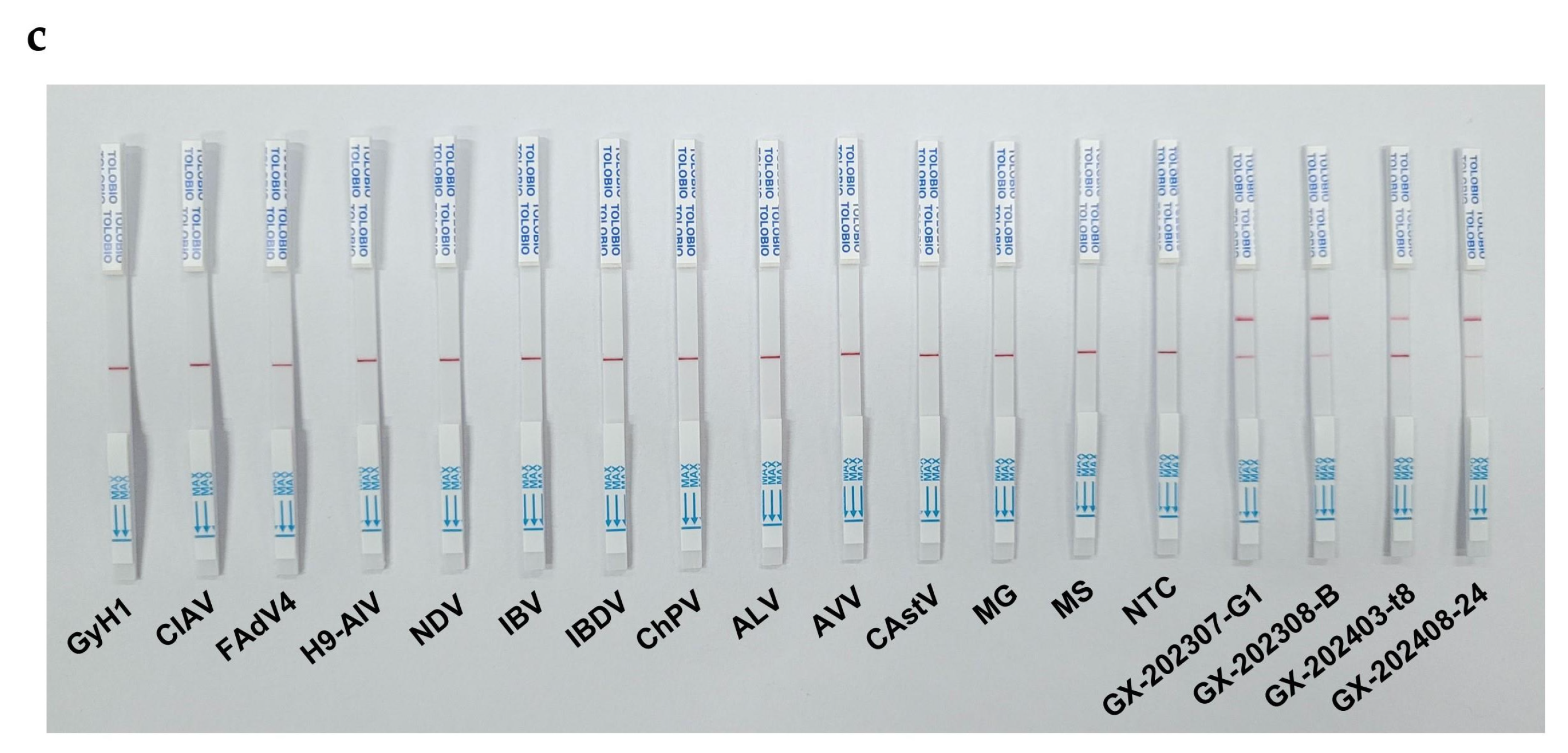

3.5. Specificity of the RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a Assay

Both RAA–CRISPR/Cas12a–FQ and RAA–CRISPR/Cas12a–LFS assays demonstrated exceptional specificity in detecting GyVg1 pathogens, as shown in

Figure 5: the four GyVg1 strains triggered corresponding fluorescence (

Figure 5a,b) and distinct T-line signals on test strips (

Figure 5c), while all 13 non-target avian viruses and negative controls exhibited no amplification or nonspecific reactions, confirming zero cross-reactivity across diverse avian pathogens.

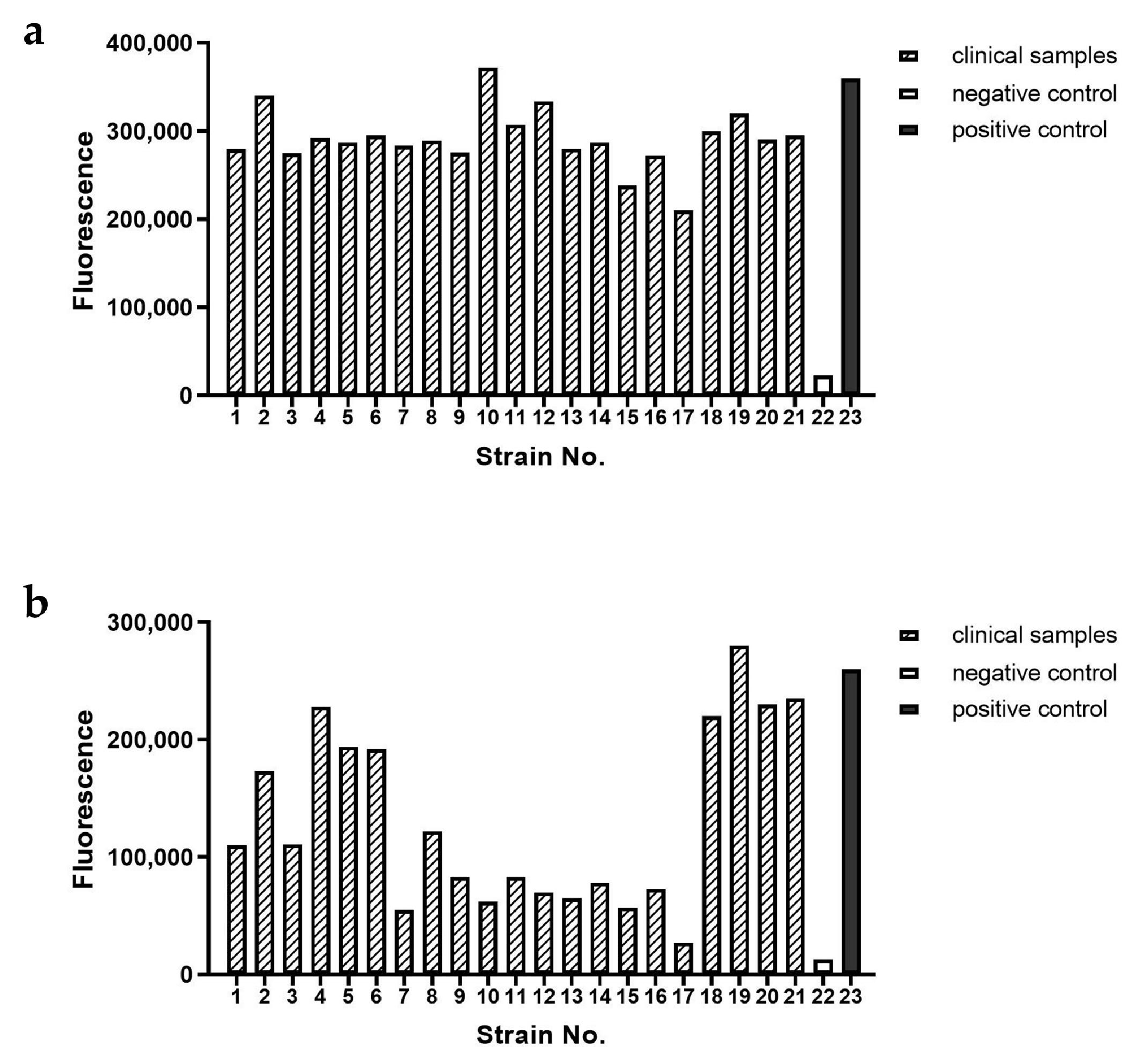

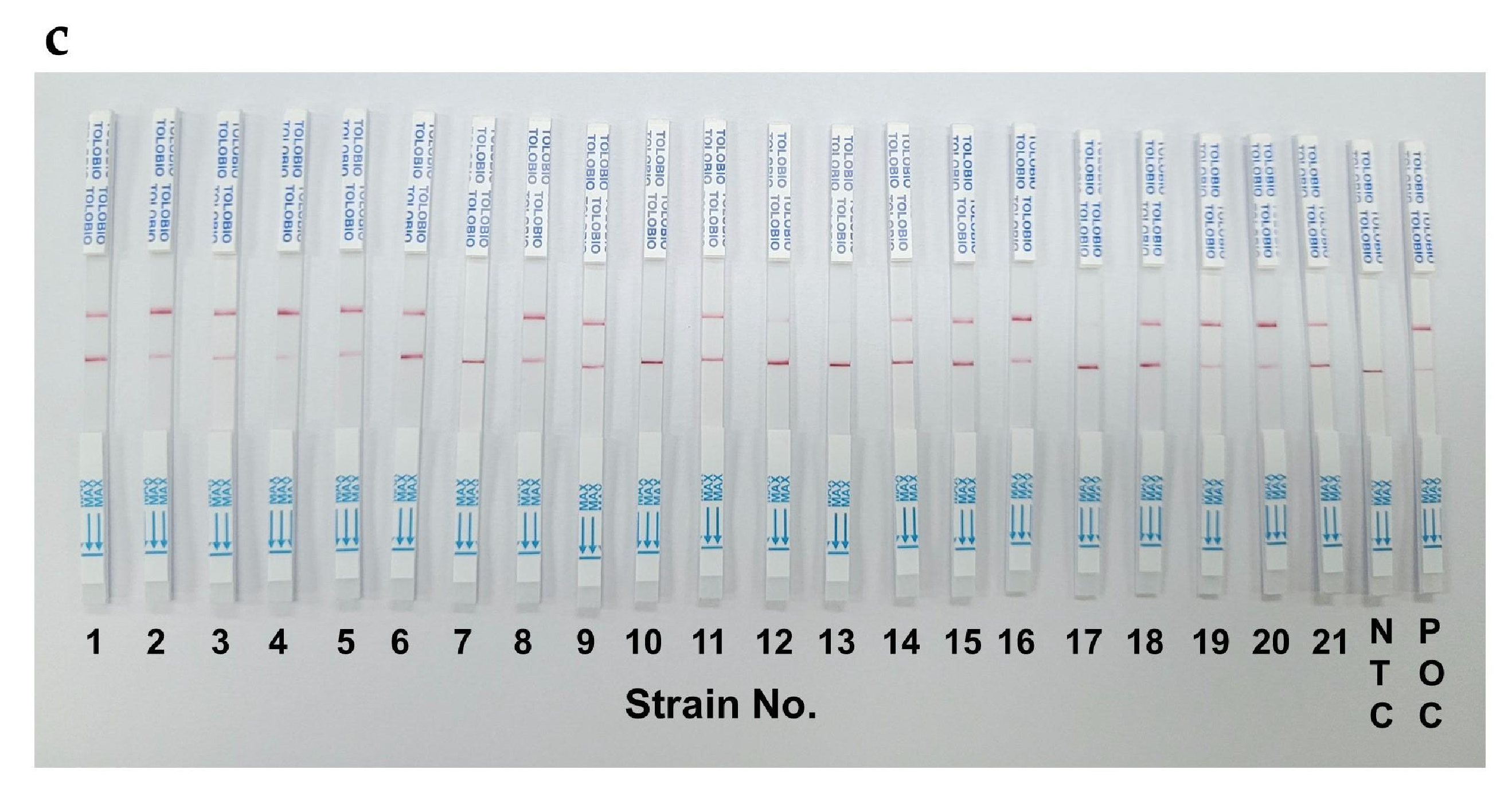

3.6. Practical Performance on Clinical Samples

In a clinical validation study comparing RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a-FQ, RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS, and qPCR using 192 prospectively collected clinical specimens, all three assays demonstrated high concordance with a Cohen’s Kappa value of 0.92 in pathogen detection. Notably, qPCR identified 21 positive cases (10.94%,

Figure 6a), a result fully replicated by the fluorescence-based RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a-FQ system (21/192,

Figure 6b). The RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS detected 18 positives (9.38%,

Figure 6c), showing 85.7% (18/21) agreement with the reference method. Sanger sequencing confirmed 100% concordance in all 21 positive samples, validating the method’s clinical-grade accuracy. This multi-platform evaluation establishes RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a technology as a robust diagnostic tool with dual-mode adaptability for both laboratories and point-of-care settings.

4. Discussion

The novel gyrovirus GyVg1, exhibiting broad zoonotic potential across humans and animals, poses a significant public health threat due to its unique pathogenic dynamics. While GyVg1 alone displays limited virulence, its clinical severity emerges through viral synergism, mirroring the high mortality observed in avirulent Newcastle disease virus coinfection [

21]. Alarmingly, GyVg1 contamination has been detected in 28% (9/32) of commercial poultry vaccines [

30], suggesting vaccine manufacturing chains as a transmission vector contributing to its global dissemination. Despite its endemic prevalence and worldwide spread, no targeted therapeutics or vaccines have been developed for its prevention and control, highlighting an urgent unmet need. Given its stealth transmission via subclinical carriers and contaminated biologics, implementing rapid, accurate diagnostic tools for GyVg1 identification becomes epidemiologically critical to disrupt transmission cascades and guide containment strategies.

The evolution of nucleic acid amplification technologies has revolutionized pathogen diagnostics, with isothermal methods emerging as practical alternatives to traditional PCR by enabling rapid target replication at constant temperatures using basic equipment like water baths or thermal cups [

31]. Among prevalent techniques including loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), RAA, rolling circle amplification (RCA), and cross-priming amplification (CPA). RAA distinguishes itself through streamlined primer design, rapid amplification (<30 min), and moderate thermal requirements though susceptible to nonspecific amplification. To address this limitation, we proposed a synergistic RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a platform: RAA is responsible for efficient isothermal target amplification and CRISPR/Cas12a is responsible for collateral cleavage, which activates upon sequence-specific recognition, triggering fluorescent or nanoparticle-based visual readouts via the ssDNA reporter. This bimodal system achieves dual enhancement of sensitivity and discrimination against false positives, and bridges laboratory-grade precision with field-deployable simplicity, demonstrating particular value in resource-constrained clinical settings.

Through systematic optimization of primer/crRNA selection, temperature, and component concentration, we established a rapid (<1 hour) two-step RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a visual detection platform comprising sequential 30-minute isothermal amplification and 20-minute Cas12a trans-cleavage phases. This is a deliberate temporal separation strategy that circumvents the sensitivity-compromising risks of premature CRISPR interference in one-pot systems [32, 33]. While addressing persistent incompatibility issues in existing spatial or physical segregation methods [34-37] (such as phase-separating solutions, PAM attenuation, mDcrRNA, PC-linkers) through ambient aerosol dissipation-enabled field adaptability, particularly suited for decentralized d [32,33iagnostics in agricultural settings where nucleic acid cross-contamination risks necessitate rapid airborne particle clearance.

This CRISPR/Cas12a-driven system enables clinic-ready GyVg1 diagnosis across settings: fluorescence quantification detects presymptomatic infections (2 copies/µL), UV visualization supports resource-limited labs (10 copies/µL), and LFS strips meet World Health Organization’s ASSURED criteria for field use (5×10

2 copies/µL), all enabled by VP2-targeted crRNA design ensuring species-specificity. RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a‒LFS shares 250-fold less sensitive than RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a‒FQ yet comparable to real-time fluorescent RAA assays (1×10² copies/µL) [

25]. Therefore, RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a is an efficient and inexpensive diagnostic tool for GyVg1.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, an RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a detection platform for GyVg1 was successfully developed in this study, and two rapid visual detection methods—RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a‒FQ and RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a -LFS—were established based on this platform and achieved high sensitivity and specificity. These easy-to-operate and low-cost assays provide powerful point-of-care detection tools for grassroots systems and significantly improve the efficiency of GyVg1 diagnosis, endowing the RAA‒CRISPR/Cas12a detection platform with broad application prospects.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: Detailed information of the obtained GyVg1 stains.

Author Contributions

writing—original draft preparation, conceptualization, investigation, writing—review and editing, and formal analysis, D.Y.; funding acquisition and project administration, Z.X., writing—review and editing, investigation, validation and visualization, Y.Z.; conceptualization, methodology and supervision, Z.X.; investigation and visualization, Q.F., S.L., L.X. and M.L.; formal analysis and validation, T.Z., M.Z. and X.L.; Data curation, Y.W., A.W. and L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Guangxi Science Base and Talents Special Program, grant number AD17195083; the CARS-Guangxi Poultry Industry Innovation Team, grant number nycytxgxcxtd-2024-19; Guangxi Key Technologies R&D Program, grant number AB25069499 and the Guangxi BaGui Scholars Program Foundation, grant number 2019A50.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal protocol used in the present study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Guangxi Veterinary Research Institute (No. #2019C0408). All the methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the poultry farmers in various areas and the live poultry market around Guangxi for providing swab and chicken tissue samples and the Key Laboratory of China (Guangxi)-ASEAN Cross-Border Animal Disease Prevention and Control, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Guangxi Key of Veterinary Biotechnology and Guangxi Veterinary Research Institute for providing their support for this study.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kraberger S, Opriessnig T, Celer V, Maggi F, Okamoto H, Blomstrom AL et al. Taxonomic updates for the genus Gyrovirus (family Anelloviridae): recognition of several new members and establishment of species demarcation criteria. ARCH VIROL 2021, 166, 2937–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijsewijk FA, Dos SH, Teixeira TF, Cibulski SP, Varela AP, Dezen D et al. Discovery of a genome of a distant relative of chicken anemia virus reveals a new member of the genus Gyrovirus. ARCH VIROL 2011, 156, 1097–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauvage V, Cheval J, Foulongne V, Gouilh MA, Pariente K, Manuguerra JC et al. Identification of the first human gyrovirus, a virus related to chicken anemia virus. J VIROL 2011, 85, 7948–7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu DK, Poon LL, Chiu SS, Chan KH, Ng EM, Bauer I et al. Characterization of a novel gyrovirus in human stool and chicken meat. J CLIN VIROL 2012, 55, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan T, Wang Z, Li R, Zhang D, Song Y, Cheng Z. Gyrovirus: current status and challenge. FRONT MICROBIOL 2024, 15, 1449814. [Google Scholar]

- Siddell SG, Walker PJ, Lefkowitz EJ, Mushegian AR, Dutilh BE, Harrach B et al. Binomial nomenclature for virus species: a consultation. ARCH VIROL 2020, 165, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsani A, Opriessnig T, Celer V, Maggi F, Okamoto H, Blomstrom AL et al. Taxonomic update for mammalian anelloviruses (family Anelloviridae). ARCH VIROL 2021, 166, 2943–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi F, Macera L, Focosi D, Vatteroni ML, Boggi U, Antonelli G et al. Human gyrovirus DNA in human blood, Italy. EMERG INFECT DIS 2012, 18, 956–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagini P, Bedarida S, Touinssi M, Galicher V, de Micco P. Human gyrovirus in healthy blood donors, France. EMERG INFECT DIS 2013, 19, 1014–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher E, Pazar P, Kovacs E, Farkas SL, Lengyel G, Jakab F et al. Molecular detection and characterization of human gyroviruses identified in the ferret fecal virome. ARCH VIROL 2014, 159, 3401–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji J, Yu Z, Cui H, Xu X, Ma K, Leng C et al. Molecular characterization of the Gyrovirus galga 1 strain detected in various zoo animals: the first report from China. MICROBES INFECT 2022, 24, 104983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu S, Man Y, Yu Z, Xu X, Ji J, Kan Y et al. Molecular analysis of Gyrovirus galga1 variants identified from the sera of dogs and cats in China. Vet Q 2024, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Lv Q, Li Y, Yu Z, Huang H, Lan T et al. Cross-species transmission potential of chicken anemia virus and avian gyrovirus 2. INFECT GENET EVOL 2022, 99, 105249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Man Y, Xu X, Wang Y, Ji J, Yao L et al. Genetic heterogeneity and potential recombination across hosts of Gyrovirus galga1 in central and eastern China during 2021 to 2024. Poult Sci 2024, 103, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos SH, Knak MB, de Castro FL, Slongo J, Ritterbusch GA, Klein TA et al. Variants of the recently discovered avian gyrovirus 2 are detected in Southern Brazil and The Netherlands. VET MICROBIOL 2012, 155, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye J, Tian X, Xie Q, Zhang Y, Sheng Y, Zhang Z et al. Avian Gyrovirus 2 DNA in Fowl from Live Poultry Markets and in Healthy Humans, China. EMERG INFECT DIS 2015, 21, 1486–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao S, Tuo T, Gao X, Han C, Li Y, Gao Y et al. Avian gyrovirus 2 in poultry, China, 2015-2016. Emerg Microbes Infect 2016, 5, e112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Xie Q, Yang Q, Luo Y, Wan P, Wu C et al. Prevalence and phylogenetic analysis of Gyrovirus galga 1 in southern China from 2020 to 2022. Poult Sci 2024, 103, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran G, Huynh L, Dong HV, Rattanasrisomporn A, Kayan A, Bui D et al. Detection and Molecular Characterization of Gyrovirus Galga 1 in Chickens in Northern Vietnam Reveals Evidence of Recombination. Animals (Basel) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Smuts, HE. Novel Gyroviruses, including Chicken Anaemia Virus, in Clinical and Chicken Samples from South Africa. Adv Virol 2014, 2014, 321284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolnik C, Wandrag DB. Avian gyrovirus 2 and avirulent Newcastle disease virus coinfection in a chicken flock with neurologic symptoms and high mortalities. AVIAN DIS 2014, 58, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao S, Gao X, Tuo T, Han C, Gao Y, Qi X et al. Novel characteristics of the avian gyrovirus 2 genome. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 41068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li J, Macdonald J, von Stetten F. Correction: Review: a comprehensive summary of a decade development of the recombinase polymerase amplification. ANALYST 2020, 145, 1950–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan M, Liao C, Liang L, Yi X, Zhou Z, Wei G. Recent advances in recombinase polymerase amplification: Principle, advantages, disadvantages and applications. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 1019071. [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, Zhao J, Yu H, Zhang Y, Yin W, Xie Z, et al. Establishment of the real-time RAA detection method for Gyrovirus galga1. Chinese Veterinary Science. 2024, 54, 1577–1585 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Kellner MJ, Joung J, Collins JJ, Zhang F. Multiplexed and portable nucleic acid detection platform with Cas13, Cas12a, and Csm6. SCIENCE 2018, 360, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetsche B, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Slaymaker IM, Makarova KS, Essletzbichler P et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. CELL 2015, 163, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen JS, Ma E, Harrington LB, Da CM, Tian X, Palefsky JM et al. CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. SCIENCE 2018, 360, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu D, Xie Z, Zhao J, Zhang Y, Xie Z, Xie L et al. Establishment of the duplex real-time PCR detection method for gyrovirus galga1 and gyrovirus homsa1. Chin J Vet Sci 2025, 45, 59–65 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Varela AP, Dos SH, Cibulski SP, Scheffer CM, Schmidt C, Sales LF et al. Chicken anemia virus and avian gyrovirus 2 as contaminants in poultry vaccines. BIOLOGICALS 2014, 42, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava P, Prasad D. Isothermal nucleic acid amplification and its uses in modern diagnostic technologies. 3 BIOTECH 2023, 13, 200. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Cao G, Chen X, Yang J, Shi M, Wang Y et al. One-pot platform for rapid detecting virus utilizing recombinase polymerase amplification and CRISPR/Cas12a. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2022, 106, 4607–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uno N, Li Z, Avery L, Sfeir MM, Liu C. CRISPR gel: A one-pot biosensing platform for rapid and sensitive detection of HIV viral RNA. ANAL CHIM ACTA 2023, 1262, 341258. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Zhou M, Hu Z, Deng W, Li Z, Wu L et al. Rapid and sensitive Cas12a-based one-step nucleic acid detection with ssDNA-modified crRNA. ANAL CHIM ACTA 2023, 1276, 341622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin K, Guo J, Guo X, Li Q, Li X, Sun Z et al. Fast and visual detection of nucleic acids using a one-step RPA-CRISPR detection (ORCD) system unrestricted by the PAM. ANAL CHIM ACTA 2023, 1248, 340938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Qian X, Zheng M, Deng K, Li C. Enhancement and inactivation effect of CRISPR/Cas12a via extending hairpin activators for detection of transcription factors. Mikrochim Acta 2023, 191, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Zou L, Liang Y, Liu Q, Sun Q, Pang Y et al. [Rapid detection and genotyping of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.4/5 variants using a RT-PCR and CRISPR-Cas12a-based assay]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2023, 43, 516–526. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).