1. Introduction

African swine fever (ASF) is a viral and acute hemorrhagic fever caused by the African swine fever virus (ASFV) in domestic pigs and wild pigs of different species [

1]. ASFV is a large and complex double-stranded DNA arbovirus, with a genome of 170-190 kb encoding 151-167 proteins [

2,

3]. As the sole representative of the Asfivirus genus within the Asfarviridae family, ASFV induces acute clinical manifestations including elevated body temperature, lethargy, loss of appetite, cutaneous discoloration, spleen enlargement, and hemorrhagic manifestations, typically resulting in catastrophic mortality rates [

4,

5]. This pathogen has progressively expanded its geographical reach in recent years, creating substantial challenges for international pork production systems [

6]. Currently, there is no effective vaccine or treatment for ASF, so early monitoring, diagnosis, and strict biosecurity measures are crucial for the prevention and controlling of ASF [

7]. Therefore, establishing an early, rapid, accurate, and field applicable detection method plays an important role in the prevention and control of African swine fever.

Numerous diagnostic techniques for ASFV identification have been established, including virus isolation, PCR, serological assays including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [

8,

9]. The existing gold standard for ASFV detection recommended by the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) is virus isolation, but the isolation and culture of ASFV must be carried out in animal biosafety level 3 laboratory (ABSL-3) or above, which is time-consuming and labor-intensive [

10]. Most serological antibody tests rely on the ELISA because it is simple and can be performed with large-scale sample testing, but it is not sensitive enough in early viral infection because antibody induction after viral infection requires relatively long time [

11]. Nucleic acid amplification techniques, particularly conventional PCR and its quantitative counterpart (qPCR), have become popular as the gold standards for detecting ASFV genomes owing to high specificity and sensitivity [

12]. However, these methods require expensive instruments and professional operators, making them less suitable for on-site applications. Therefore, developing new, convenient, simple, accurate, and inexpensive methods for detecting ASFV is the current and future development direction.

In recent years, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-associated Cas proteins have shown significant potential for rapid and sensitive nucleic acid detection [

13]. The CRISPR-Cas12b (C2c1) system is a dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease system [

14]. As the third most efficient CRISPR endonuclease after Cas9 and Cas12a, CRISPR/Cas12b exhibits strict complementarity dependence between single guide (sg) RNA and target DNA, eliminating tolerance for mismatches and thereby achieving superior specificity in molecular diagnostics applications [

15]. Cas12b uniquely combines cis-cleavage (target DNA-specific cutting) and trans-cleavage (non-specific ssDNA degradation) activities [

16]. Cis-cleavage of Cas12b refers to the sequence-specific cleavage of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) guided by the sgRNA [

17]. Trans cleavage of Cas12b can efficiently cleave non-specific single stranded DNA (ssDNA), including DNA modified with fluorescent and quenching groups (FQ), producing detectable fluorescence signals [

18]. Efficient trans cutting, as a superior signal amplification method, increases sensitivity by approximately 2 to 3 orders of magnitude. Cas12b’s cis-cleavage enables precise genome editing, while its trans-cleavage powers rapid diagnostics. By utilizing this characteristic, the CRISPR/Cas system has been combined with isothermal amplification technology to develop a series of simple, rapid, sensitive, and visual nucleic acid detection methods that do not require special precision instruments.

The B646L gene, encoding the viral major capsid protein p72, is highly conserved and well characterized. This target is widely used in both nucleic acid detection and phylogenetic analysis [

19,

20]. In this study, we established an RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS method for the detection of ASFV by selecting the B646L gene as the target and optimizing a specific combination of RPA primers, sgRNA and probes. Further, our research results indicated that the B646L-RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS method can be effectively applied to clinical ASFV detection, providing a new detection method for clinical ASF prevention and control.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Specimens

The virus DNA extraction kit Hipure Tissue DNA Mini Kit (D3121-02) and Hipure Blood DNA Mini Kit (D3111-02) were purchased from Magen Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China). The BL21(DE3) competent E.coli(CB105) was purchased from Tiangen BioTech Co., Ltd (Beijing China). The His-tag Protein Purification Kit (p2226) and DEPC-treated Water(DNase、RNase free,R0021) were bought from Beyotime Biotech, Inc. (Shanghai, China). The FastPure Gel DNA Extraction Mini Kit (DC301-01) and T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit (TR101-01) were both from Nanjing Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). Spin Column RNA Cleanup & Concentration Kit (B518688) was purchased from Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The recombinant polymerase amplification (RPA) kit (TwistAmp Basic, Cat #TABAS03KIT) was from TwistDx Limited (Maidenhead, UK). The lateral flow strip (31203) was purchased from TOBOLIO Biotech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The ASFV B646L gene standard plasmid was prepared and stored in our laboratory. The classical swine fever virus (CSFV) attenuated strain (CVCC AV1412) and porcine pseudorabies virus (PRV) attenuated strain (Bartha-K61) were purchased from Jiangsu Nannong Hi Tech Co., Ltd (Nanjing China). The inactivated porcine parvovirus (PPV4, S-1 strain) was purchased from Shangdong Huahong Biological Engineering Co., Ltd (Binzhou, China). PRRSV and PCV3 samples were isolated and stored in our laboratory.

2.2. Cloning of AapCas12b Gene, Protein Expression and Purification

The AapCas12b gene sequence was PCR-amplified from plasmid pAG001 His6-TwinStrep-SUMO-AapCas12b (Addgene) using specific primers pET28a-AapCas12b-F/R (

Table 1) and subsequently inserted into EcoR I / Xho I sites of pET28a through homologous recombination. Following transformation into BL21 (DE3) competent E. coli cells, protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 16°C for 18 h. Analysis of post-lysis revealed that AapCas12b was mainly in the soluble fraction. Subsequently, the AapCas12b underwent purification via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography after ultrasonic cell disruption. Three sequential dialysis cycles (2 h each) were performed at 4°C using a buffer containing 600 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5% glycerol, and 2 mM DTT. Protein purity and identity were confirmed through SDS-PAGE with Coomassie blue staining and Western blot analysis using His-tag specific antibody.

2.3. Preparation of sgRNA

Based on the conserved B646L gene sequence obtained through multiple alignment, as well as the fixed scaffold sequence and the special PAM sequence 5′-TTN-3′ (where N can be any base of A, T, G, C) of AapCas12b, the encoding sequences for sgRNA targeting B646L gene were designed (

Table 1). The DNA template of sgRNA was attached with the T7 promoter sequence (GAAATTAATACGATACTATATATAGGG) (

Table 1), and then synthesized by Qingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. as the primers. The complementary primers were annealed in annealing buffer into double stranded (ds) DNA, followed by DNA extraction and purification. The purified dsDNA was used as a template to be transcribed into sgRNA through

in vitro transcription (IVT). The transcribed sgRNA was purified using a column RNA rapid concentration and purification kit (Sangon Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

2.4. B646L Mediated CRISPR/AapCas12b Reaction

The B646L DNA sequence was based on the ASFV YZ-1 genome (GenBank No: ON456300), and the plasmid pCE-B646L constructed in our laboratory was used as the template DNA for reaction. The CRISPR/AapCas12b reaction system was established as follows: 1 μL AapCas12b (250 ng/μL), 1 μL ssDNA probe (4μM, a 12-base-pair random DNA sequence with FAM as a reporter and BHQ1 as a quencher, as shown in

Table 1), 1 μL sgRNA (150 ng/μL), 2 μL buffer, 1µL plasmid pCE-B646L (100 ng/μL) or 2 μL B646L PCR amplified fragment (110 ng/μL), and add distilled water to a total volume of 20 µL. The reaction mix was incubated at 60 °C for 15 min for AapCas12b-mediated cleavage to occur. The reaction products were verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, blue light, UV light, and fluorescence detection, respectively.

2.5. Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA)

Following the design criteria for RPA primers, a length range of 28-35 base pairs and optimal amplicon sizes between 150-200 bp, two pairs of PRA primers targeting the B646L gene were designed (

Table 1). The reaction protocol followed the TwistAmp Basic Kit (TwistDx) specifications, with each 50 μL amplification mixture comprising 29.5 μL rehydration buffer, reaction beads, 0.48 μM forward/reverse primers, purified DNA template, 2.5 μL MgAc solution, and sterile water to adjust volume. Thermal incubation at 39℃ in a water bath for 15-20 min facilitated DNA amplification, with subsequent electrophoretic analysis of B646L gene products. Primer pairs underwent comparative evaluation to select optimal performer, with the chosen B646L-RPA amplicons subsequently integrated into CRISPR/AapCas12b detection workflows.

2.6. Establishment of RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-Lateral Flow Strip (LFS) Detection Method

Firstly, the biotin-conjugated single-stranded DNA probe (5′-6-FAM-TTTTTTTATTTTTTT-biotin-3′) was commercially synthesized. Subsequently, colloidal gold particles functionalized with FAM-specific antibody were conjugated to the ssDNA probe, forming a lateral flow detection complex with 5′-gold-antibody-FAM-ssDNA-biotin-3′ architecture. The amounts of reaction components are as follows: a 2 μL aliquot representing 10% of the RPA amplification product, 1 μL AapCas12b enzyme, 1 μL sgRNA complex, 2 μL reaction buffer, 1 μL of 20 nM gold-biotin ssDNA probe, and 12.5 µL buffer, totaling 20 µL. Following a 15-min incubation at 60°C, the LFS absorbent pad was immersed in the reaction mixture. After complete saturation of the nitrocellulose membrane within 1-2 min, the control (C) line’s gold signal confirmed test validity. Visual interpretation was performed by assessing colloidal gold accumulation at the test (T) line position, with positive results indicating ASFV target presence in analyzed samples. In the presence of ASFV target sequences, the CRISPR/AapCas12b complex cleaves the ssDNA reporter probe, dissociating FAM-labeled gold nanoparticles from biotin molecules. Streptavidin immobilized on the control line (C) retains the biotin components, while liberated FAM-gold complexes migrate laterally to be captured by second antibody at T line.

2.7. Sensitivity and Specificity of B646L-RPA-AapCas12b-LFS Detection Method

To assess the sensitivity of the detection, the standard plasmid pCE-B646L was diluted to different copy numbers, and continuous dilutions of plasmids with concentrations from 6 x 1010 copies/µL to 6 x 100 copies/µL were prepared. RPA amplification was performed on each plasmid dilution, followed by CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS detection. The minimum copy number of the target pCE-B646L plasmid was detected with test strip to determine the sensitivity.

For specificity, viral nucleic acids including DNA or RNA were extracted from the other swine virus samples, with RNA from porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) and classical swine fever virus (CSFV), DNA from porcine parvovirus (PPV4), porcine pseudorabies virus (PRV) and porcine circovirus types 3 (PCV3). The above viral RNA or DNA were used as the target DNA to conduct the CRISPR/AapCas12b reaction mediated by B646L sgRNA followed by LFS detection to determine the reaction specificity of CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS detection.

2.8. Detection of Clinical Samples by RPA-AapCas12b-LFS

In this study, the nucleic acid DNAs were extracted from various pig tissues including 3 hearts, 3 livers, 3 spleens, 3 lungs, 3 kidneys, 3 lymph nodes, 5 sera, 5 blood samples and 6 oral swabs by using High Tissue DNA Mini Kit (D3121-02) and High Blood DNA Mini Kit (D3111-02) according to the instructions. The above DNAs were used as the target DNA to conduct the CRISPR/AapCas12b reaction mediated by B646L sgRNA followed by LFS detection.

3. Results

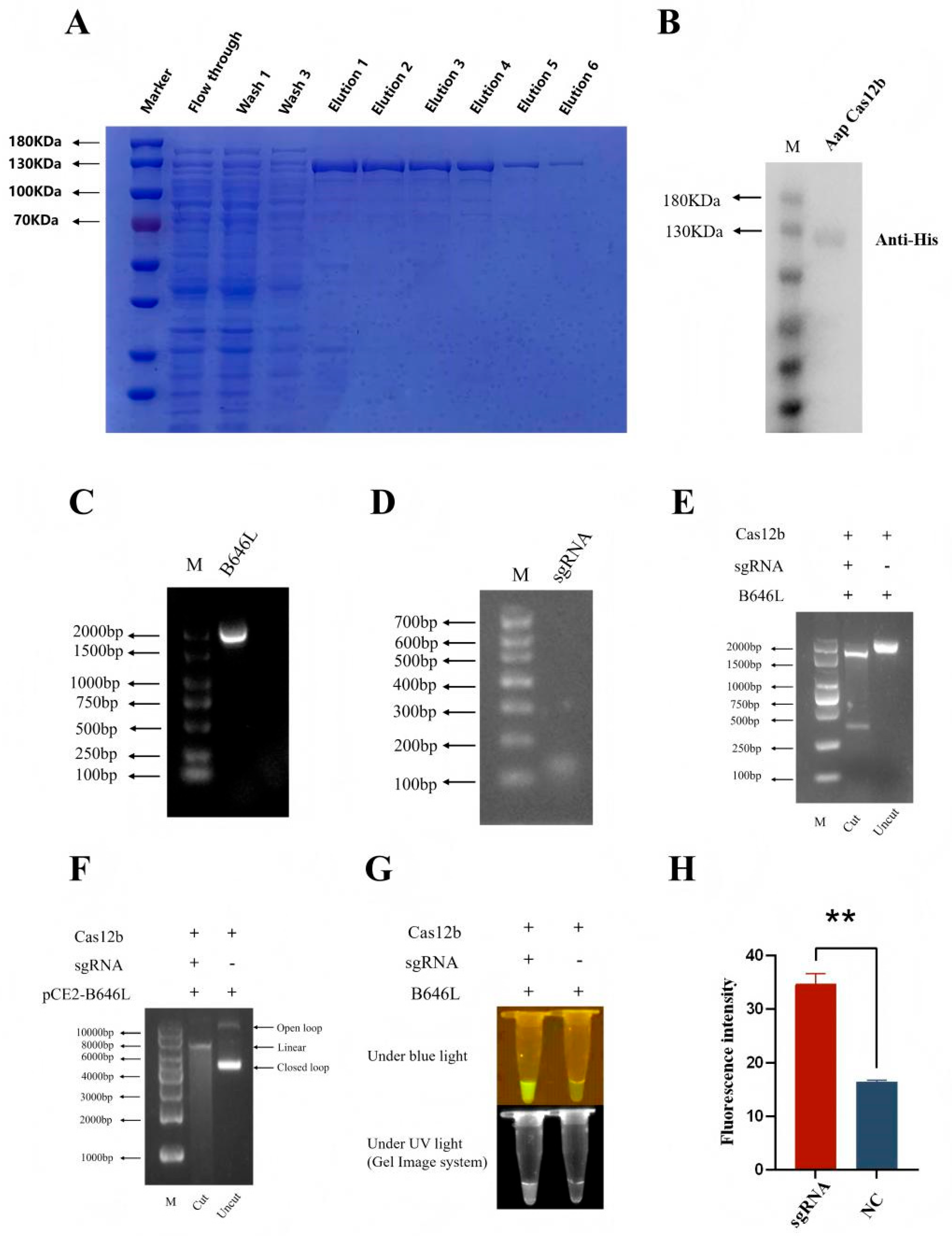

3.1. The Expression and Purification of AapCas12b

The AapCas12b gene was PCR amplified, and the PCR product was cloned into the pET28a vector by homologous recombination, followed by transformation into BL21(DE3) competent

E. coli. The purified AapCas12b protein was verified by SDS-PAGE plus commassie blue staining and immunoblotting with anti-His antibody. The results showed that the purified AapCas12b protein had a molecular weight of approximately 130 kDa (

Figure 1A) and was recognized by a mouse anti-His tag monoclonal antibody (

Figure 1B).

3.2. Validation of the Cleavage Activities of the Purified AapCas12b Protein

Cas12b uniquely combines cis-cleavage (target DNA-specific cutting) and trans-cleavage (non-specific ssDNA degradation) activities [

16]. To verify the cis-cleavage and trans-cleavage activities of the purified AapCas12b protein, a DNA template of ASFV B646L PCR products (

Figure 1C), a sgRNA of ASFV B646L (

Figure 1D) were generated, and a ssDNA probe (

Table 1) was synthesized. The purified AapCas12b protein could cleave the DNA template of ASFV B646L PCR products into two DNA segments (

Figure 1E). Further, the purified AapCas12b protein could cleave the plasmid pCE-B646L into a linearized configuration (

Figure 1F). The purified AapCas12b protein could also exhibit trans-cleavage activity to cleave ssDNA probe and generate a light signal (

Figure 1G and H). These results suggested that the cis and trans cleavage activities of purified AapCas12b protein are high, and the purified AapCas12b protein is feasible for subsequent detections.

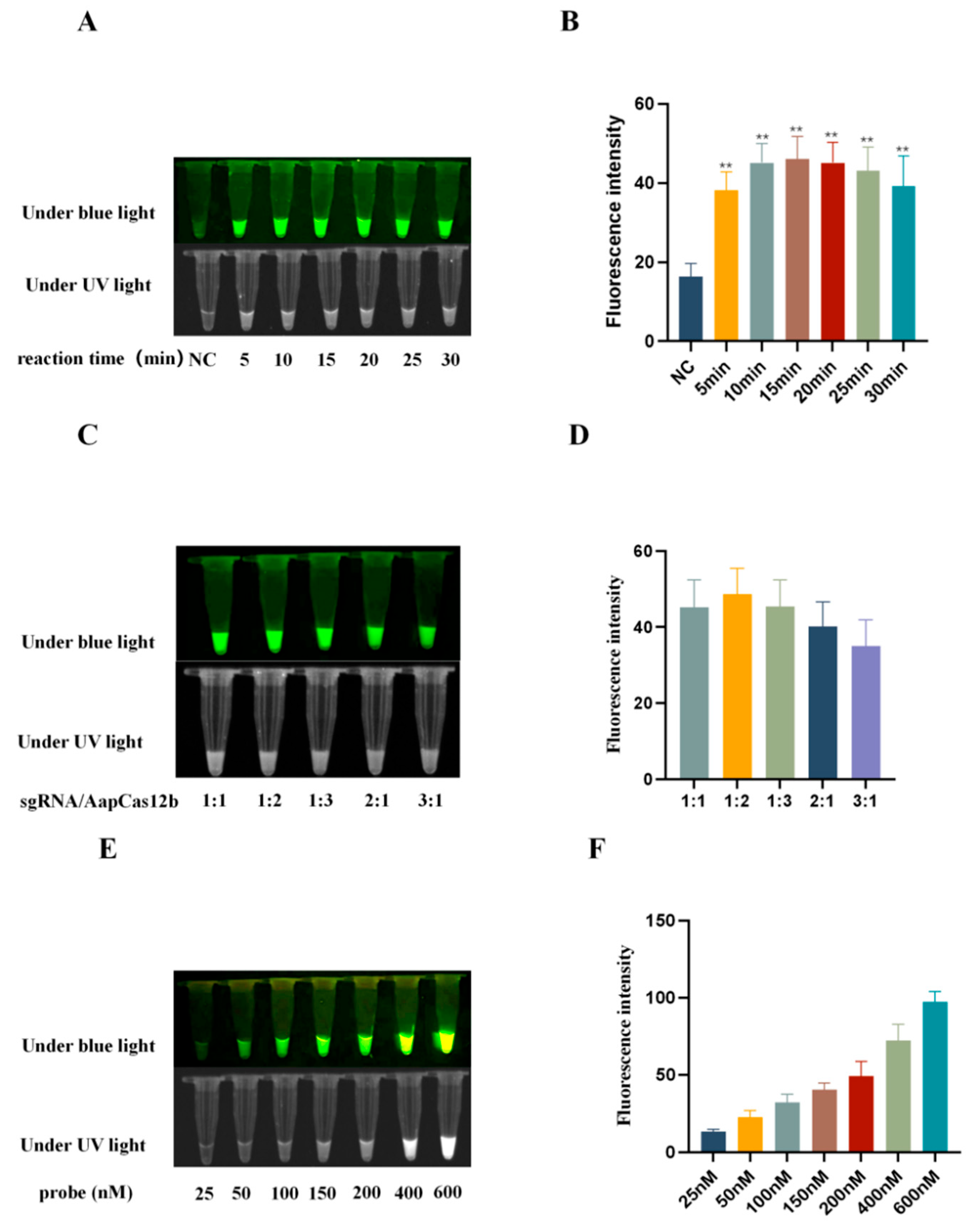

3.3. Optimization of Reaction Conditions of CRISPR/AapCas12b Assay

In order to optimize the reaction conditions including time, sgRNA/AapCas12b ratio, and probe concentration, the blue light, ultraviolet light, and fluorescence signals caused by the AapCas12b trans cutting of the ssDNA probe were analyzed. First, the CRISPR/AapCas12b reactions were performed for durations of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 min, respectively. The results showed that when the reaction time was 15 min, the light signal was better than other time groups (

Figure 2A and 2B). Second, the CRISPR/AapCas12b reactions were carried out at different ratios of sgRNA/AapCas12b (1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 2:1 and 3:1). The results have shown that the cutting activity of AapCas12b is affected by the sgRNA/AapCas12b ratio, and the signal of probe is higher at a 1:2 gRNA/AapCas12b ratio than at other ratios (

Figure 2C and 2D). Third, the CRISPR/AapCas12b reactions were carried out with the increase of probe concentration from 25 nM to 600 nM. The results showed that the signal intensity of the blue light, ultraviolet light and fluorescence signals all increased continuously (

Figure 2E and 2F). Considering the balance of signal to noise, the probe concentration of 150 nM was considered as appropriate.

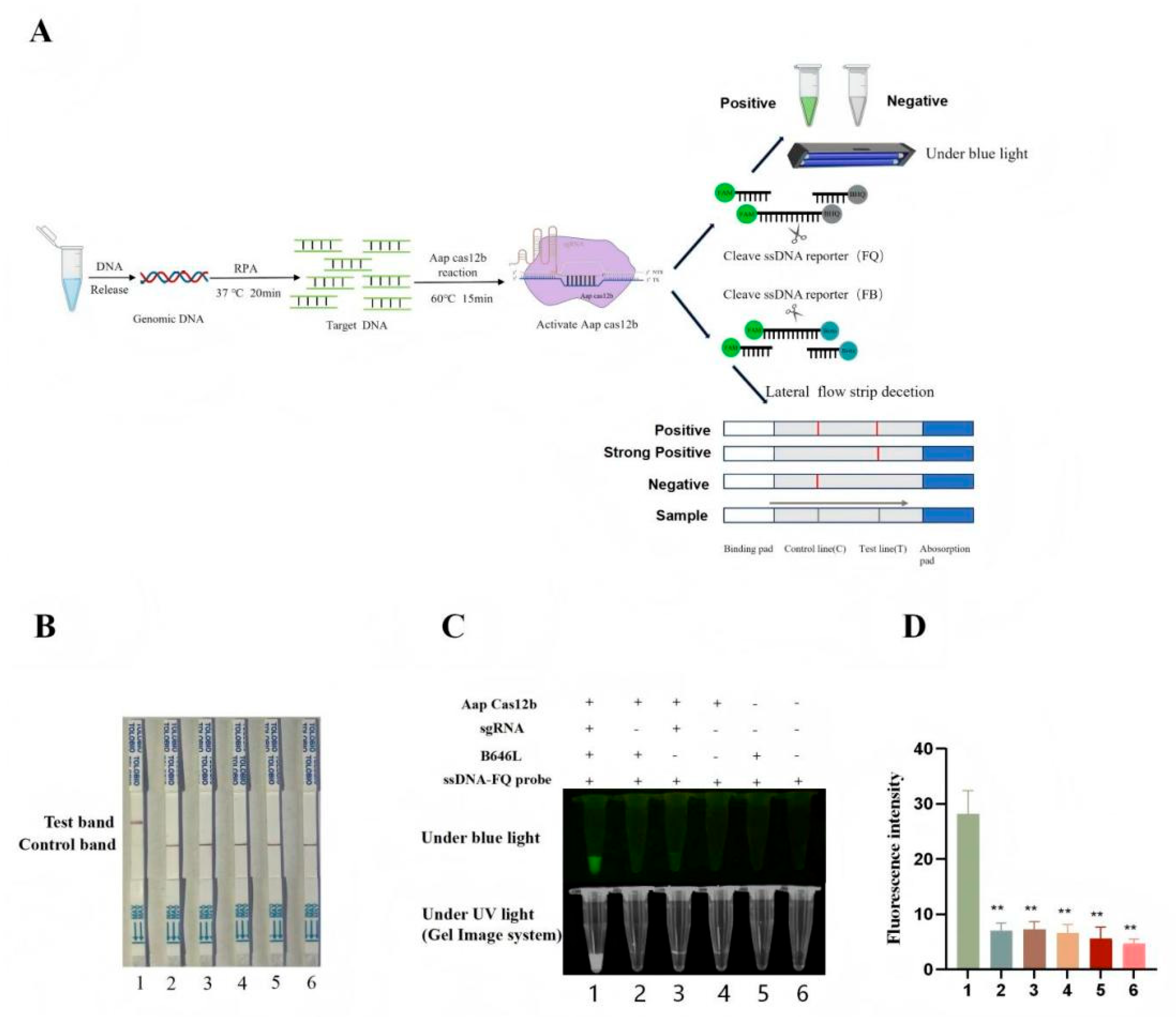

3.4. Establishment of CRISPR/AapCas12b Mediated Lateral Flow Strip (LFS) Method

The green fluorescence of probe can be observed under blue light , but a device that emits blue light is still needed, which is not convenient for field detection. In order to develop a convenient and efficient visual detection method, the CRISPR/AapCas12b mediated lateral flow strip (LFS) method was established. As shown in

Figure 3A, the ssDNA probe labeled by 5’-FAM and 3’-biotin was used for LFS detection. The FAM antibody cross-linked gold particles on the test strip react with the FAM from probe. If the sample to be tested contains the ASFV B646L gene, the CRISPR/AapCas12b system will cut off the ssDNA probe and separate the FAM gold particles from biotin. Thus, the FAM gold particles are able to cross the streptavidin coated C line, continue to migrate forward, and will be captured by secondary antibody on the T line, presenting a positive gold line (

Figure 3A). On the contrary, the ssDNA report probe in the negative sample reaction is not cleaved and will be completely captured by C line streptavidin (

Figure 3A). Our results demonstrated that the gold particle signal appeared on the T line of the LFS only when AapCas12b, crRNA, B646L gene, and gold particle probe are all present (

Figure 3B). The detection results of AapCas12b-LFS were completely consistent with those of blue light, ultraviolet light, and fluorescence signals (

Figure 3C-D).

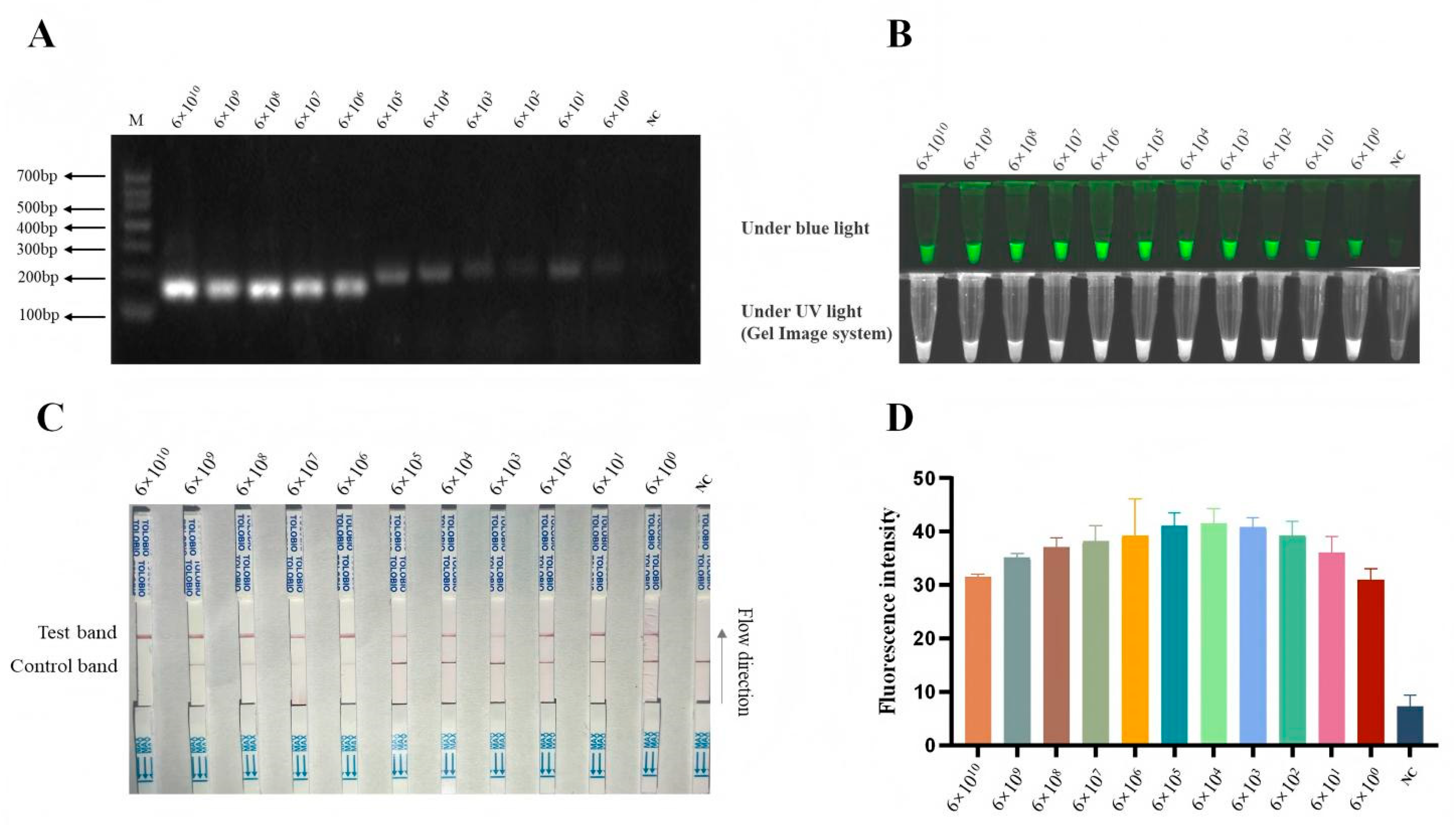

3.5. Sensitivity of B646L-RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS Method

To enhance the detection sensitivity of the CRISPR/AapCas12b system, we developed two RPA primers (

Table 1) targeting the ASFV B646L gene before CRISPR/AapCas12b reaction (

Figure 3A). Our results suggested that both pairs of RPA primers exhibited comparable performance in the B646L gene amplification (not shown), and the RPA primer 1 (RPA-B646L-F1/R1) was selected for subsequent experiments. Next, pCE-B646L plasmids were serially diluted 10-fold to obtain concentrations ranging from 6 × 10¹⁰ copies/µL to 6 × 10⁰ copies/µL. Each dilution was subjected to RPA, and the amplification products (

Figure 4A) were subsequently detected using the AapCas12b-LFS system. The sensitivity of AapCas12b-based detection was assessed via LFS (

Figure 4B) and cross-verified by using light and fluorescence detections (

Figure 4C and 4D). As shown in the results, the RPA-AapCas12b-LFS system achieved a low limit of detection of 6 copies/µL (

Figure 4B-D). The results suggested that the B646L-RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12a-LFS method has very high sensitivity for the detection of ASFV.

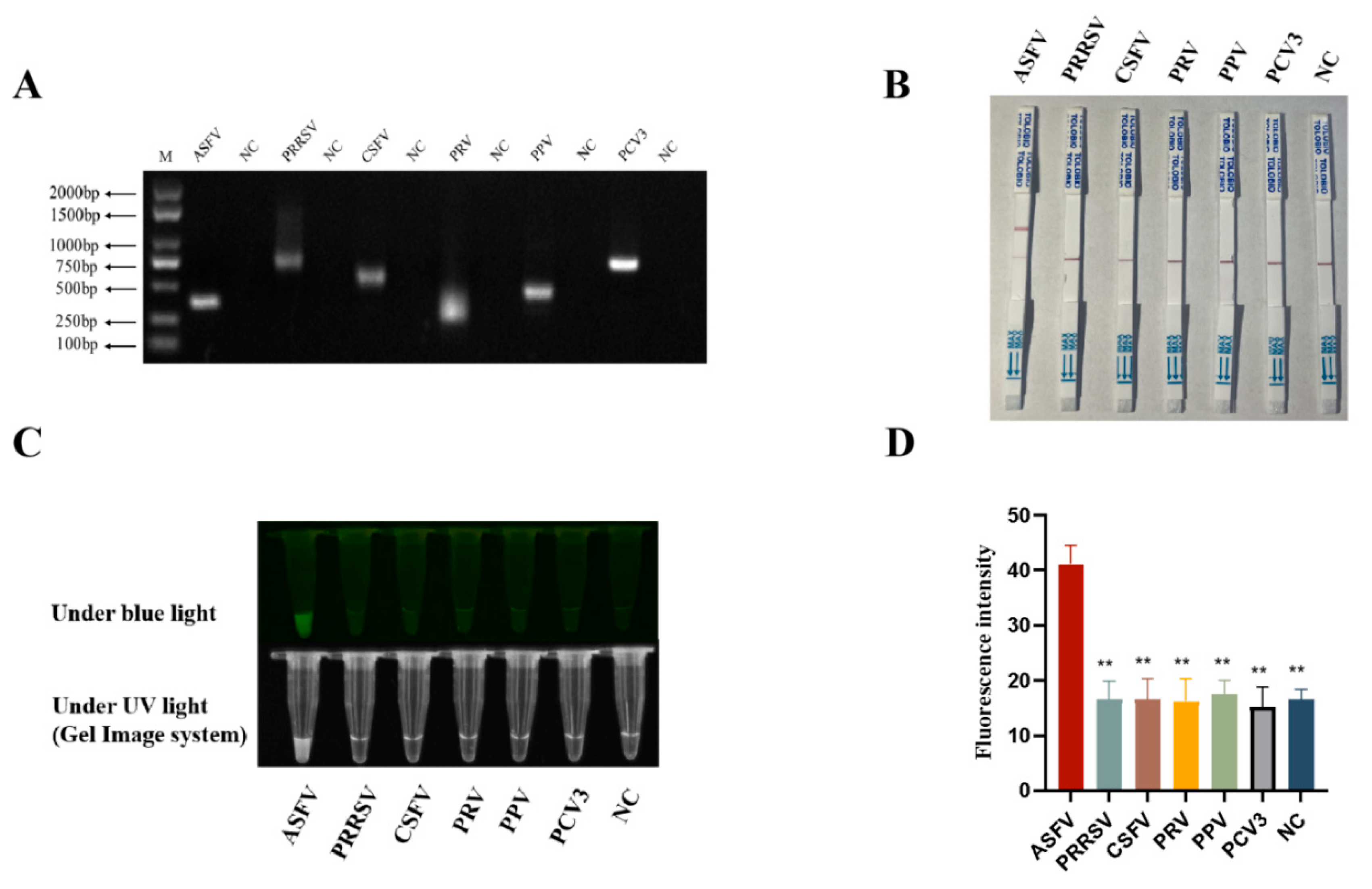

3.6. Specificity of RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS Detection Method

In order to verify the specificity of RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b detection method, nucleic acid samples of five pig viruses other than ASFV were obtained, including the RNA from RNA viruses PRRSV and CSFV, DNA from DNA viruses PRV, PPV4 and PCV3. The nucleic acid samples of five pig viruses and ASFV were all confirmed by PCR (

Figure 5A) by using the specific PCR primers (

Table 1). Results from the RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS assay showed that gold particle signals were observed on the C lines of all porcine virus samples, whereas only the ASFV sample additionally presented positive gold particle signal on its T line (

Figure 5B). Similar results were also obtained from RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b reaction detection using blue and ultraviolet lights, and fluorescence detection (

Figure 5C-D). In summary, the RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b method had very high specificity for detection of ASFV.

3.7. RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS Detection of Clinical Samples

A total of 34 clinical samples were detected by using the established RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS system. The results from RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS showed that 17 clinical samples were positive (Nos.1–17), and 17 clinical samples were negative (Nos.18–34) (

Figure 6). To validate the reliability of the CRISPR/AapCas12b-LPS assay in ASFV detection, verification was carried out by using qPCR which is recommended by the WOAH (

Table 1). The results of qPCR showed that the RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS detection results were completely consistent with the qPCR detection results (

Table 2). These result further confirmed the reliability of the RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS method for detecting clinical samples of ASFV.

4. Discussion

CRISPR-Cas system has recently gained growing attention as a diagnostic tool due to its capability of specific gene targeting [

21]. It consists of Cas enzymes and a gRNA that can cleave the target DNA/RNA based on the sequence of the gRNA, making it an attractive genetic engineering technique [

22]. In addition to the target-specific binding and cleavage, the trans-cleavage activity was reported for some Cas proteins, including Cas12a, Cas12b and Cas13 which is to cleave the surrounding single-stranded DNA or RNA upon the target binding of Cas-gRNA complex [

23,

24]. Cas12a and Cas12b are both RNA-guided enzymes that target DNA, enabling their application in the detection of specific DNA sequences [

14]. Cas13a is also an RNA-cleaving enzyme, however, its target is RNA, a characteristic that enables it to be used for the detection of specific RNA molecules [

25,

26]. Among these Cas protein systems, the most significant difference lies in their optimal reaction temperatures: Cas12a and Cas13b operate at 37 ℃, whereas the Cas12b system functions at 60 ℃ [

27]. Cas12b, derived from thermophilic bacteria, is highly thermostable and functions optimally at 60°C and above [

18]. The thermostability of Cas12b allows for high-temperature incubations, which can improve editing efficiency and reduce off-target effects [

28].

Previously, our team have established the RPA-CRISPR-LbCas12a and RPA-CRISPR-LwCas13a detecting methods based on the ASFV D117L and S273R genes to detect the ASFV [

29,

30,

31]. Due to the different types of nucleic acids recognized by Cas12a and Cas13a, the combination of CRISPR/Cas12a and CRISPR/Cas13a systems may be used for simultaneous differential diagnosis of ASFV in a single-tube. However, one study has suggested that the efficiency of Cas12a could be suppressed by Cas13a components, when put them in a single reaction [

32]. The reaction temperature of Cas12b is 60 ℃, and it is possible that regulating different reaction temperatures to activate the activities of Cas12b and Cas13a, sequentially, and meanwhile, the high temperature of 60 ℃ can inactivate the enzymatic activity of Cas13a, thereby avoiding mutual interference. Thus, the aim of this study is to establish the RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b method for detecting the ASFV. Also, it will lay the foundation for the future design of a method for simultaneous differential diagnosis of ASFV by combining the Cas12b and Cas13a detection systems.

In current research, a rapid, low-cost and visual RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS nucleic acid test for ASFV detection by selecting the conserved structural gene B646L was established. The method combines RPA and LFS, and can be performed by non-specialists. The user only needs to add the required reagents to the nucleic acid sample to be tested, complete the reaction in a constant temperature water bath within 1 h, and observe the results with the naked eye. The reagents involved in the assay can be used for more than six months when stored between -15 ℃ and -25 ℃. Water bath pots and pipettes are the main equipment required to perform testing, showing the potential application in on-site ASFV testing.

Meanwhile, we optimized the CRISPR/AapCas12b reaction parameters including reaction time, probe and sgRNA/AapCas12b ratio, and achieved optimal visualization not only under blue and UV light, but also on lateral chromatography test strip. The detection sensitivity of RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS can reach 6 copies. At the same time, the test showed no cross-reactivity with five other swine viruses, proving its excellent specificity, which is very important in clinical testing. In addition, each strip test costs about $0.61 according to our estimation. For the detection of 34 clinical samples, the coincidence rate of RPA-CRISPR/AapCas12b-LFS test with qPCR test was 100%, demonstrating its reliability in clinical diagnosis.

5. Conclusions

We have developed a rapid, sensitive and specific RPA-CRISPR/Cas12b-LFS method for ASFV detection. It can be used for visual detection of ASFV in clinical samples and has potential significance for early monitoring, prevention, and control of ASF.

Author Contributions

J.Z and W.Z (Wanglong Zheng) conceived and designed the experiments; W.H, Y.C and W.Z (Wangli Zheng) performed the experiments; L.C, Z.X and X.K analyzed the data and drew the figures; J.Z, N.C and J.B wrote the manuscript, made revisions and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was partly supported by the 2024 Annual Special Funds for Municipal-School Cooperation Projects of Yangzhou City (YZ2024220) and the Open Project Program of Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Zoonosis (No. R2304) and the Undergraduate Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (XCX20250819, XCX20240816) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Solikhah, T.I.; Rostiani, F.; Nanra, A.F.P.; Dewi, A.D.P.P.; Nurbadri, P.H.; Agustin, Q.A.D.; Solikhah, G.P. African swine fever virus: Virology, pathogenesis, clinical impact, and global control strategies. Vet World 2025, 18, 1599–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, L.K.; Chapman, D.A.G.; Netherton, C.L.; Upton, C. African swine fever virus replication and genomics. Virus Res 2013, 173, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.L.; Xi, F.; Zeng, W.X.; Zhao, Y.F.; Cao, W.J.; Liu, C.; Yang, F.; Ru, Y.; Xiao, S.Q.; Zhang, S.L.; et al. Structural basis of RNA polymerase complexes in African swine fever virus. Nat Commun 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruedas-Torres, I.; Nga, B.T.T.; Salguero, F.J. Pathogenicity and virulence of African swine fever virus. Virulence 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.X.; Li, T.T.; Huang, T.; Zhao, G.H.; Wang, X.; Li, J.N.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Z.X.; Zheng, J.; Weng, C.J. S5092 inhibit ASFV infection by targeting the pS273R protease activity in vitro. Vet Microbiol 2025, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceruti, A.; Kobialka, R.M.; Abd El Wahed, A.; Truyen, U. African Swine Fever: A One Health Perspective and Global Challenges. Animals-Basel 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Zhang, X.H.; Qi, W.B.; Yang, Y.Z.; Liu, Z.X.; An, T.Q.; Wu, X.H.; Chen, J.X. Prevention and Control Strategies of African Swine Fever and Progress on Pig Farm Repopulation in China. Viruses-Basel 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Ge, X.N.; Gao, P.; Zhou, Q.Q.; Han, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.N.; Yang, H.C. Advances in the diagnostic techniques of African swine fever. Virology 2025, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Sun, Z.Y.; Sun, S.H.; Zhang, K.L.; Deng, D.F.; He, P.; Zhang, P.P.; Xia, N.W.; Jiang, S.; Zheng, W.L.; et al. The capsid protein p72 specific mAb and the corresponding novel epitope based ELISAs for detection of ASFV infection. Vet Microbiol 2025, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.Q.; Tian, X.G.; Lai, R.R.; Wang, X.L.; Li, X.W. Current detection methods of African swine fever virus. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.J.; Tesfagaber, W.; Zhang, J.W.; Li, F.; Sun, E.C.; Tang, L.J.; Bu, Z.G.; Zhu, Y.M.; Zhao, D.M. Establishment of an indirect immunofluorescence assay for the detection of African swine fever virus antibodies. J Integr Agr 2024, 23, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.X.; Shen, T.R.; Feng, Z.X.; Diao, S.J.; Yan, Y.; Du, Z.K.; Jin, Y.L.; Gu, J.Y.; Zhou, J.Y.; Liao, M.; et al. Development of a highly sensitive TaqMan method based on multi-probe strategy: its application in ASFV detection. Biol Methods Protoc 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.F.; Luo, S.H.; Li, W.B.; Su, W.T.; Chen, S.T.; Liu, C.C.; Pan, W.L.; Situ, B.; Zheng, L.; Li, L.; et al. Co-freezing localized CRISPR-Cas12a system enables rapid and sensitive nucleic acid analysis. J Nanobiotechnol 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, F.; Cui, T.T.; Feng, G.H.; Guo, L.; Xu, K.; Gao, Q.Q.; Li, T.D.; Li, J.; Zhou, Q.; Li, W. Repurposing CRISPR-Cas12b for mammalian genome engineering. Cell Discov 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurel, F.; Wu, Y.C.; Pan, C.T.; Cheng, Y.H.; Li, G.; Zhang, T.; Qi, Y.P. On- and Off-Target Analyses of CRISPR-Cas12b Genome Editing Systems in Rice. Crispr J 2023, 6, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.J.; Fang, T.T.; Cai, Q.S.; Li, H.; Li, H.Y.; Sun, H.Q.; Zhu, M.Z.; Dai, L.S.; Shao, Y.Q.; Cai, L. Rapid detection of in sputum using CRISPR-Cas12b combined with cross-priming amplification in a single reaction. J Clin Microbiol 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Ye, X.F.; Liu, Y.F.; Li, W.T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Yi, C.Q.; Liu, C.X. Regulating cleavage activity and enabling microRNA detection with split sgRNA in Cas12b. Nat Commun 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Macaluso, N.C.; Pizzano, B.L.M.; Cash, M.N.; Spacek, J.; Karasek, J.; Miller, M.R.; Lednicky, J.A.; Dinglasan, R.R.; Salemi, M.; et al. A thermostable Cas12b from leverages one-pot discrimination of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Ebiomedicine 2022, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, V.; Spinard, E.; Xu, L.Z.; Berninger, A.; Barrette, R.W.; Gladue, D.P.; Faburay, B. Full-Length ASFV B646L Gene Sequencing by Nanopore Offers a Simple and Rapid Approach for Identifying ASFV Genotypes. Viruses-Basel 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Zhao, D.M.; Wang, J.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, M.; Gao, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, J.F.; Bu, Z.G.; Rao, Z.H.; et al. Architecture of African swine fever virus and implications for viral assembly. Science 2019, 366, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.; Balusamy, S.R.; Perumalsamy, H.; Ståhlberg, A.; Mijakovic, I. CRISPR-Cas target recognition for sensing viral and cancer biomarkers. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, 10040–10067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Goswami, H.N.; Whyms, C.T.; Sridhara, S.; Li, H. Structural principles of CRISPR-Cas enzymes used in nucleic acid detection. J Struct Biol 2022, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Cheng, Q.X.; Liu, J.K.; Nie, X.Q.; Zhao, G.P.; Wang, J. CRISPR-Cas12a has both - and -cleavage activities on single-stranded DNA. Cell Res 2018, 28, 491–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, P.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Loi, K.J.; Adler, B.A.; Lahiri, A.; Vohra, K.; Shi, H.L.; Rabelo, D.B.; Trinidad, M.; Boger, R.S.; et al. Structure-guided discovery of ancestral CRISPR-Cas13 ribonucleases. Science 2024, 385, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.J.; Li, R.R.; Qiu, X.; Fan, T.Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L. Advances in application of CRISPR-Cas13a system. Front Cell Infect Mi 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.C.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.Q.; Bai, X.; Zhang, T. Rapid Detection of Feline Calicivirus Using Lateral Flow Dipsticks Based on CRISPR/Cas13a System. Animals-Basel 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Quan, X.Y.; Li, Y.C.; Guo, H.Y.; Kong, F.E.; Lu, J.H.; Teng, L.R.; Wang, J.S.; Wang, D. Visual detection of SARS-CoV-2 with a CRISPR/Cas12b-based platform. Talanta 2023, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Rananaware, S.R.; Yang, L.G.; Macaluso, N.C.; Ocana-Ortiz, J.E.; Meister, K.S.; Pizzano, B.L.M.; Sandoval, L.S.W.; Hautamaki, R.C.; Fang, Z.R.; et al. Engineering highly thermostable Cas12b viastructural analyses for one-pot detection of nucleic acids. Cell Rep Med 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.S.; Jiang, S.; Xia, N.W.; Zhang, Y.W.; Zhang, J.J.; Liu, A.J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Chen, N.H.; Meurens, F.; Zheng, W.L.; et al. Rapid Visual Detection of African Swine Fever Virus with a CRISPR/Cas12a Lateral Flow Strip Based on Structural Protein Gene D117L. Animals-Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.S.; Jiang, S.; Xia, N.W.; Zhang, J.J.; Liu, A.J.; Deng, D.F.; Zhang, C.Y.; Sun, Y.X.; Chen, N.H.; Kang, X.L.; et al. Development of visual detection of African swine fever virus using CRISPR/ LwCas13a lateral flow strip based on structural protein gene D117L. Vet Microbiol 2024, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.J.; Zhang, D.S.; Hao, W.L.; Liu, A.J.; Xia, N.W.; Cui, M.; Luo, J.; Jiang, S.; Zheng, W.L.; Chen, N.H.; et al. Parallel and Visual Detections of ASFV by CRISPR-Cas12a and CRISPR-Cas13a Systems Targeting the Viral S273R Gene. Animals-Basel 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, T.; Qiu, Z.Q.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Zhu, D.B.; Zhou, X.M. Exploiting the orthogonal CRISPR-Cas12a/Cas13a-cleavage for dual-gene virus detection using a handheld device. Biosens Bioelectron 2022, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).