Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

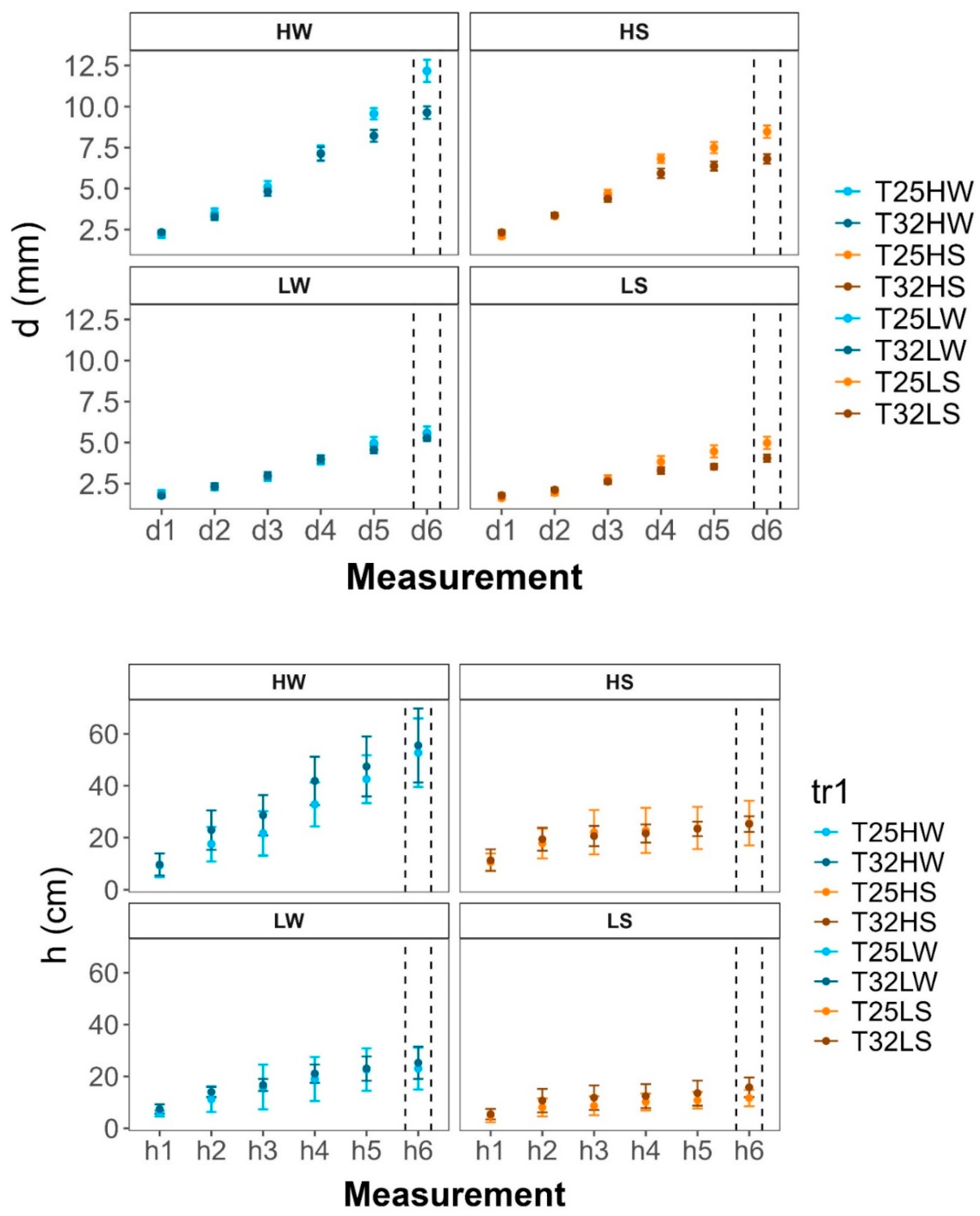

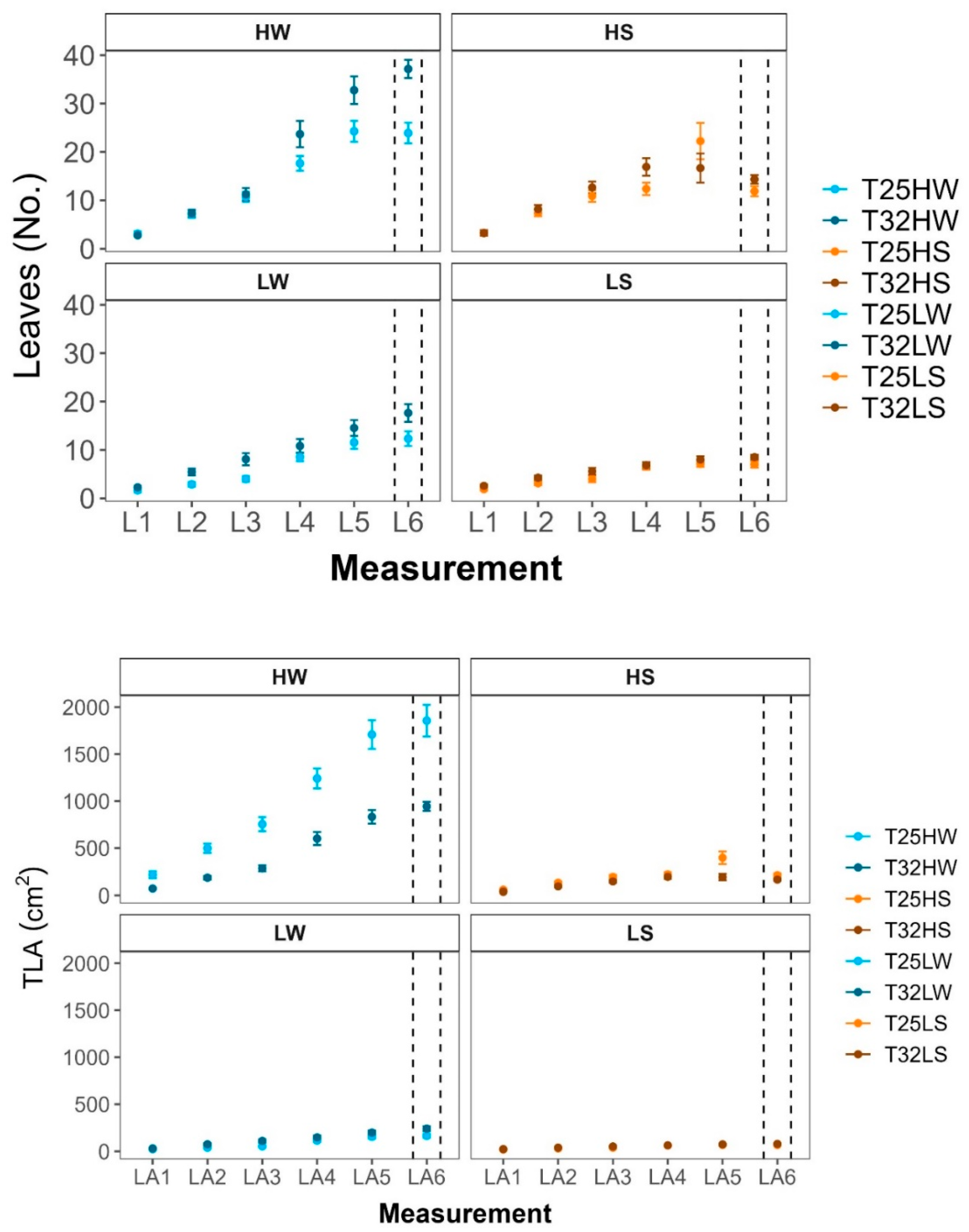

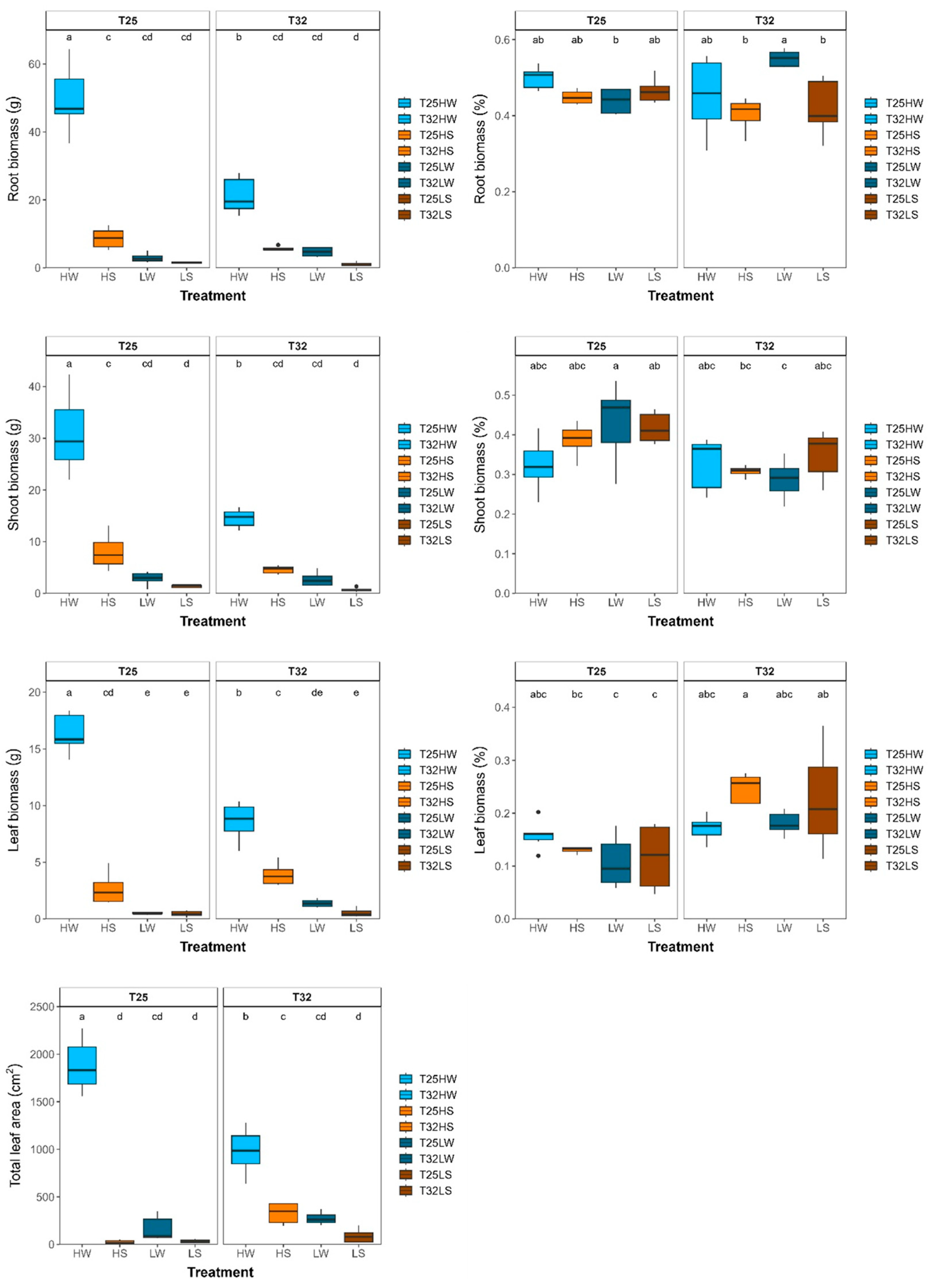

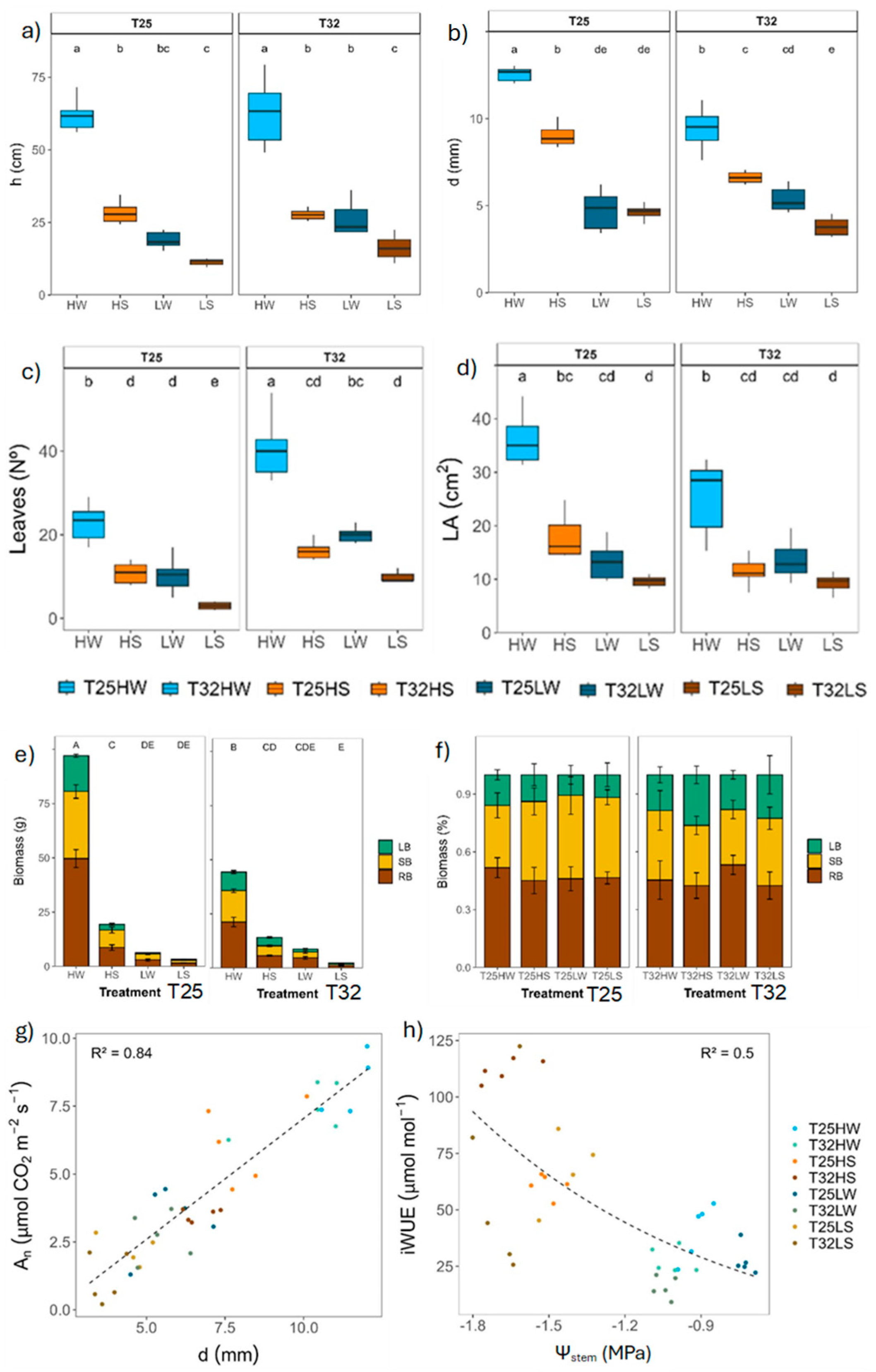

Changes in Morphology and Biomass Allocation

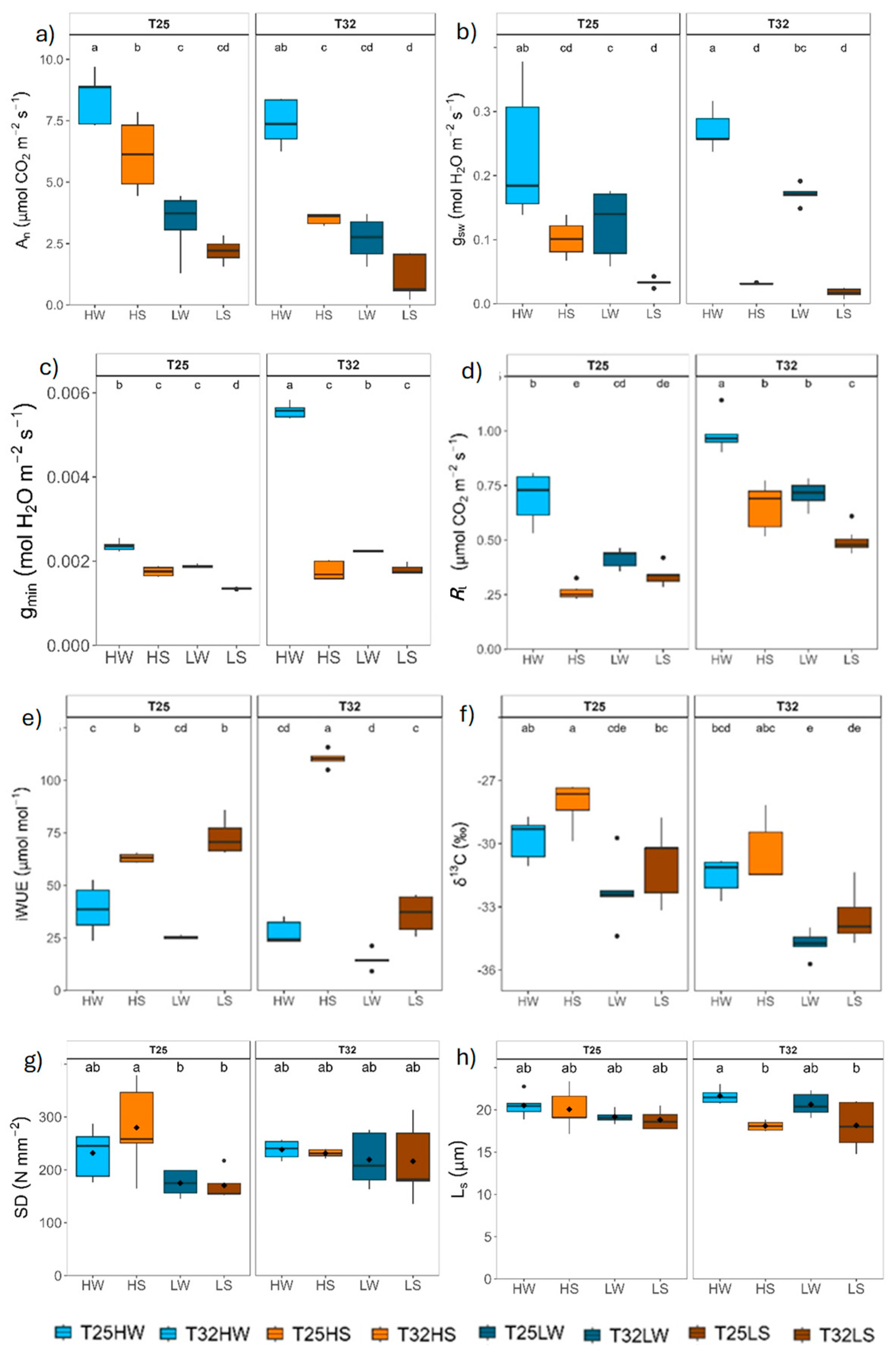

Leaf Gas Exchange, Water Use Efficiency and Stomatal Traits

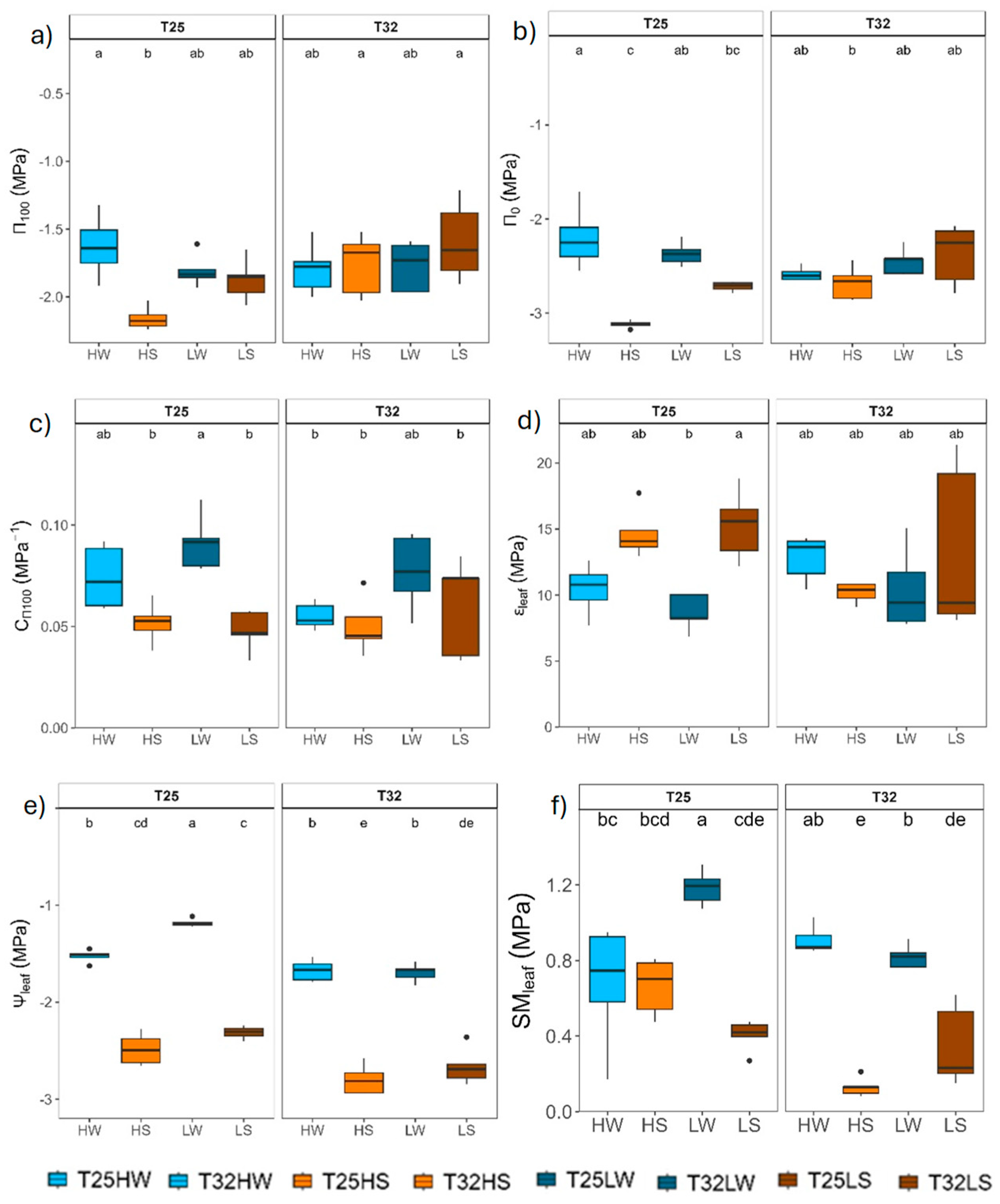

Leaf Water Relations

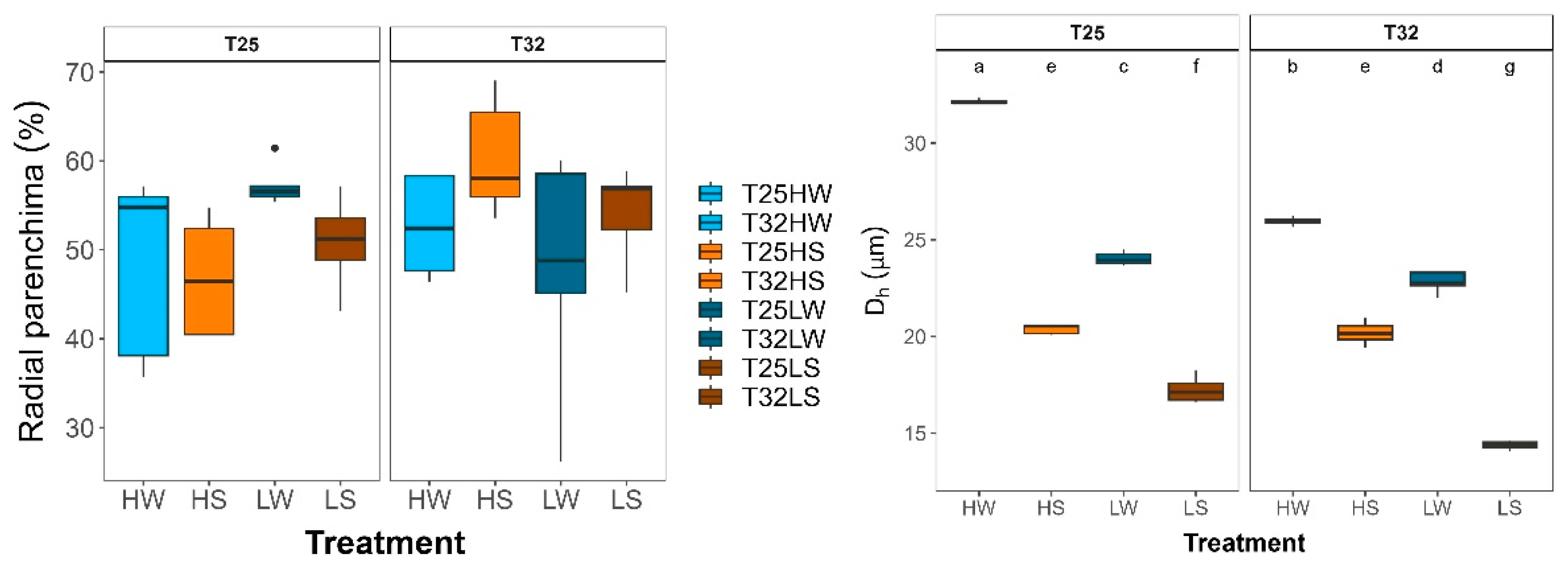

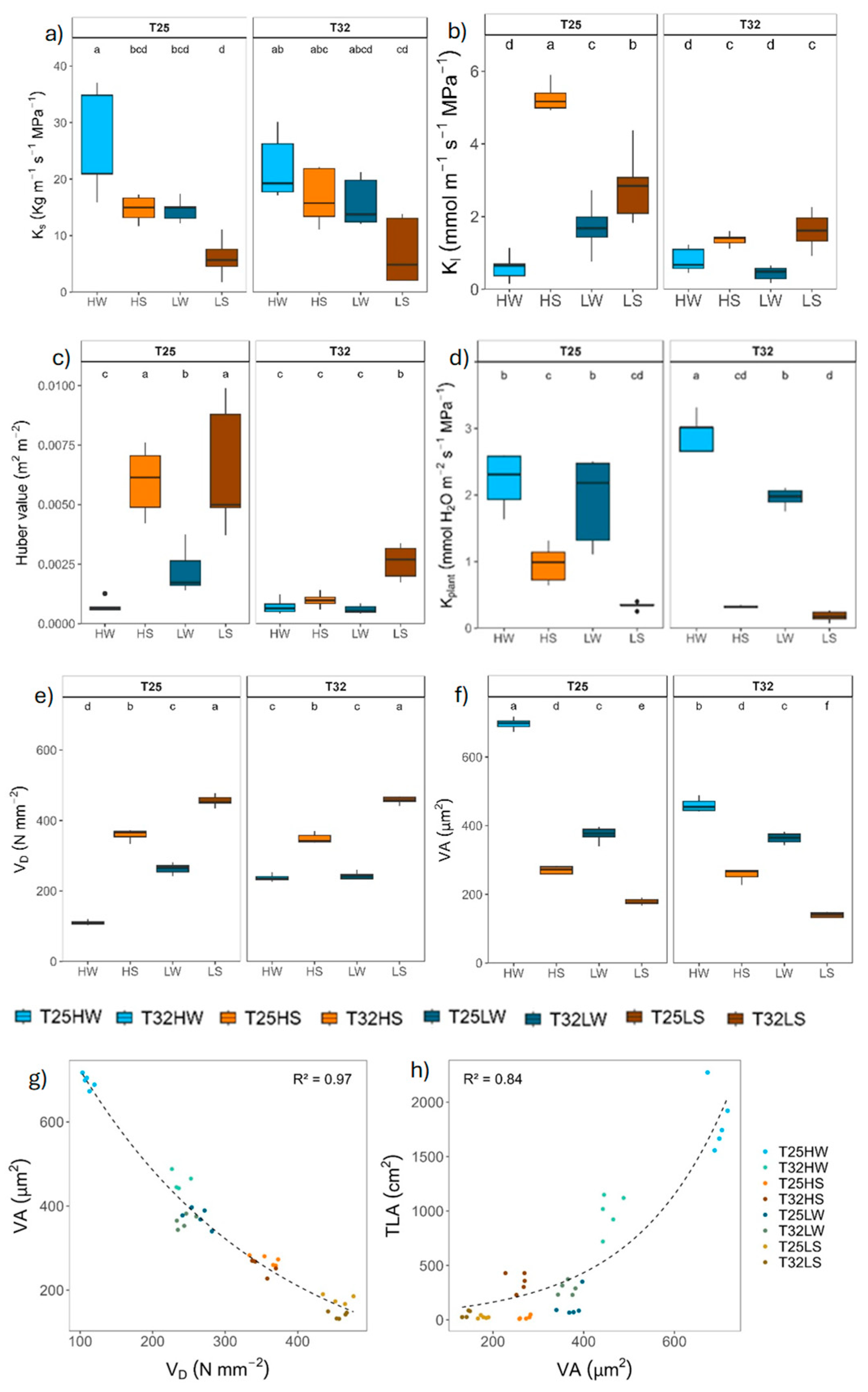

Hydraulic Traits and Stem Anatomy

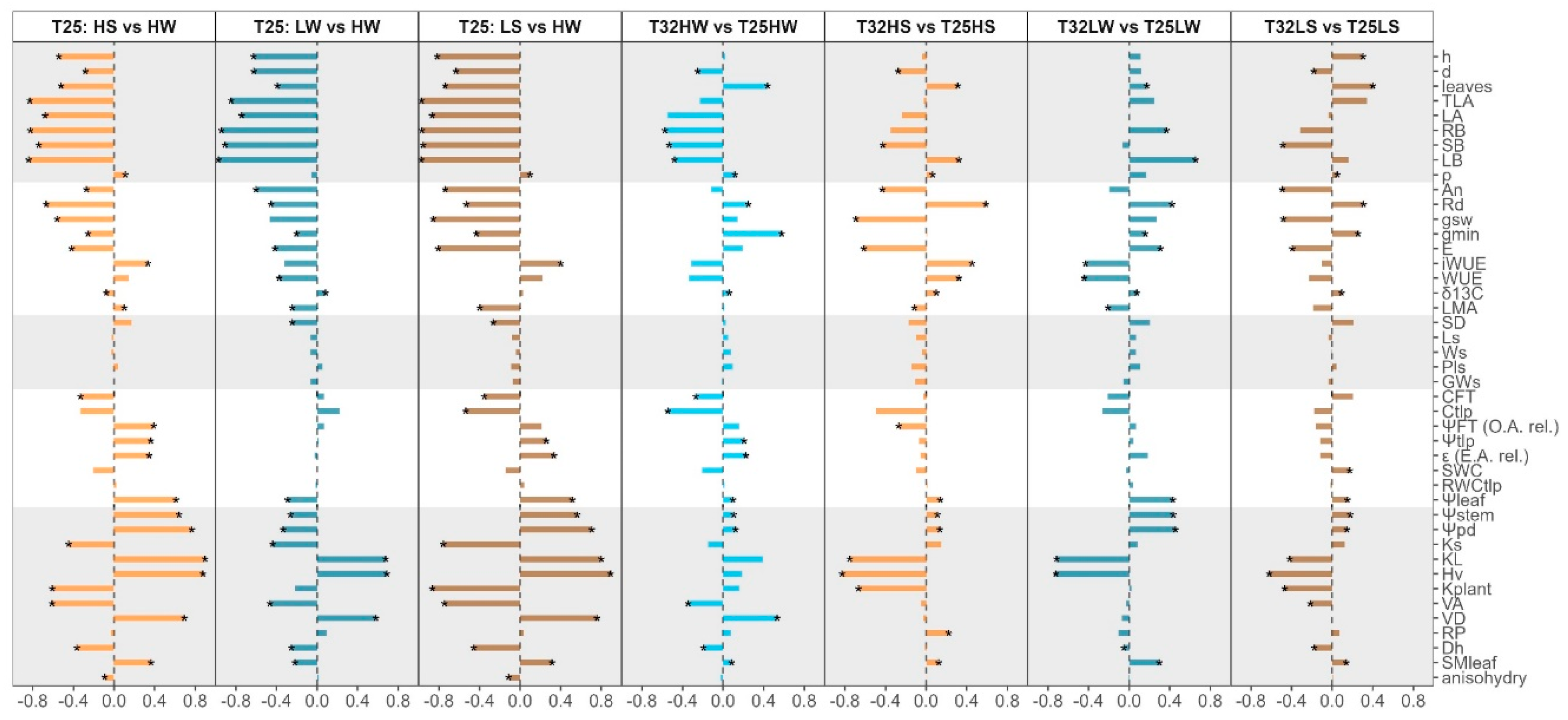

Plasticity in Response to Temperature, Light, and Water Availability

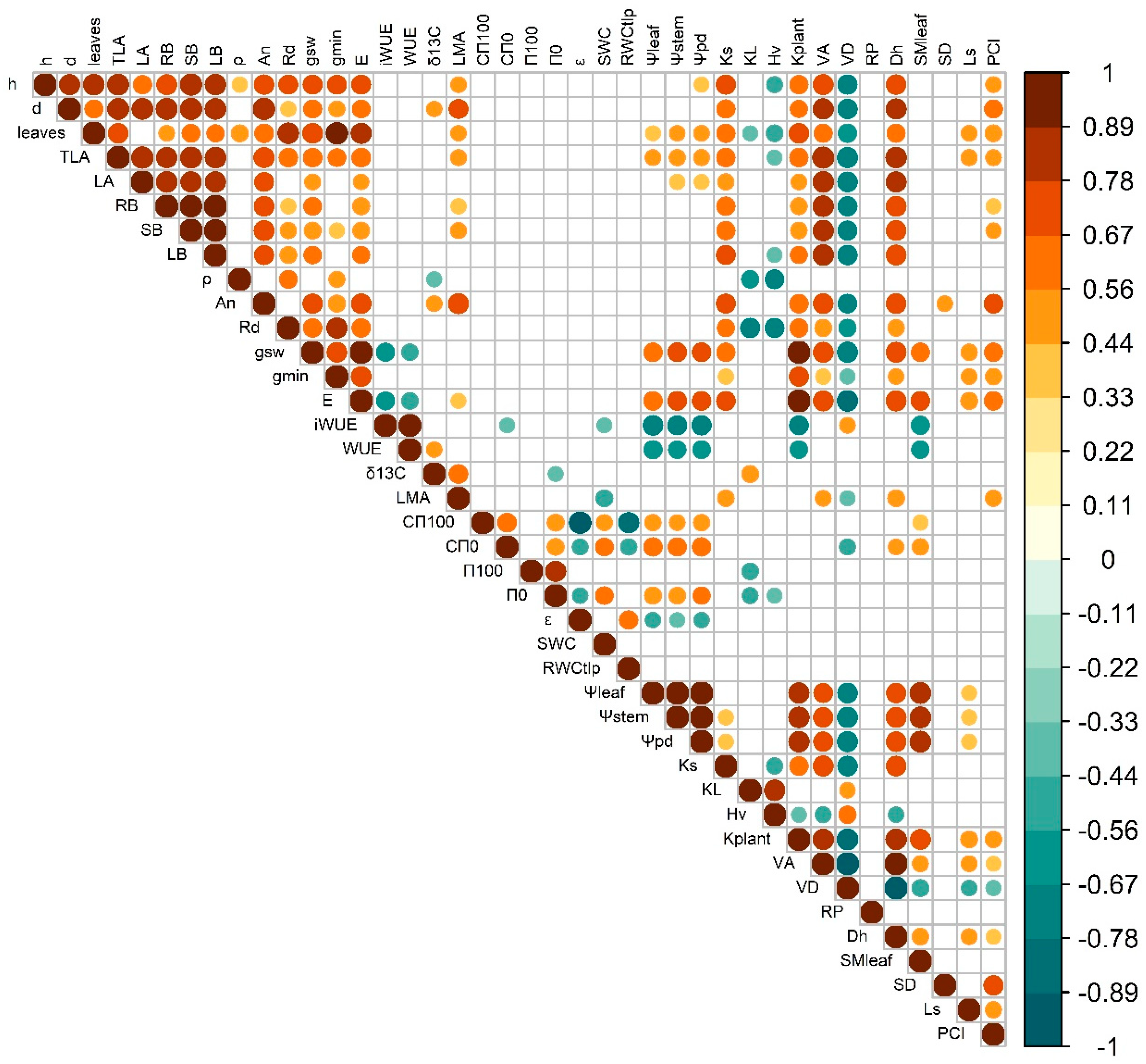

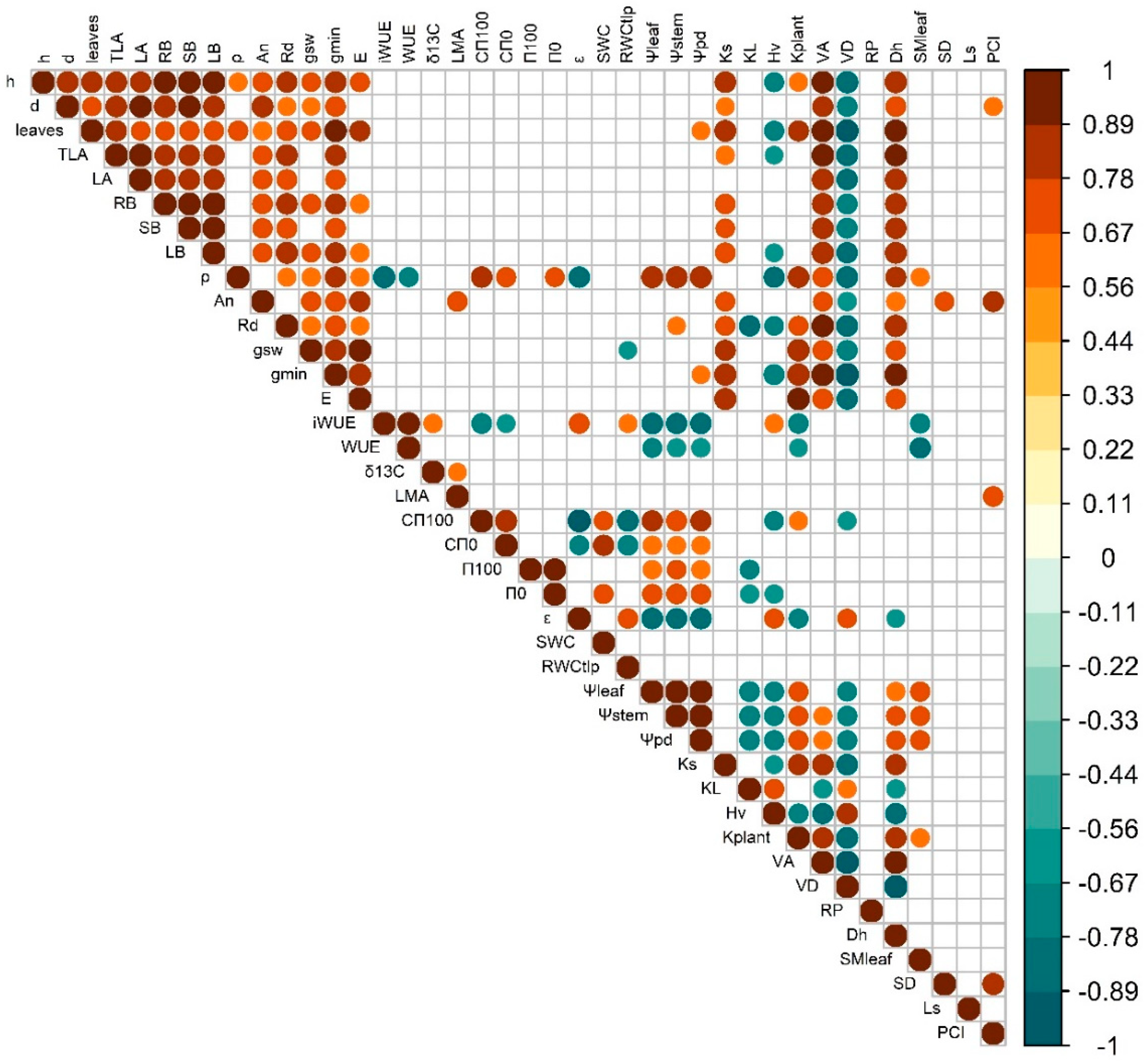

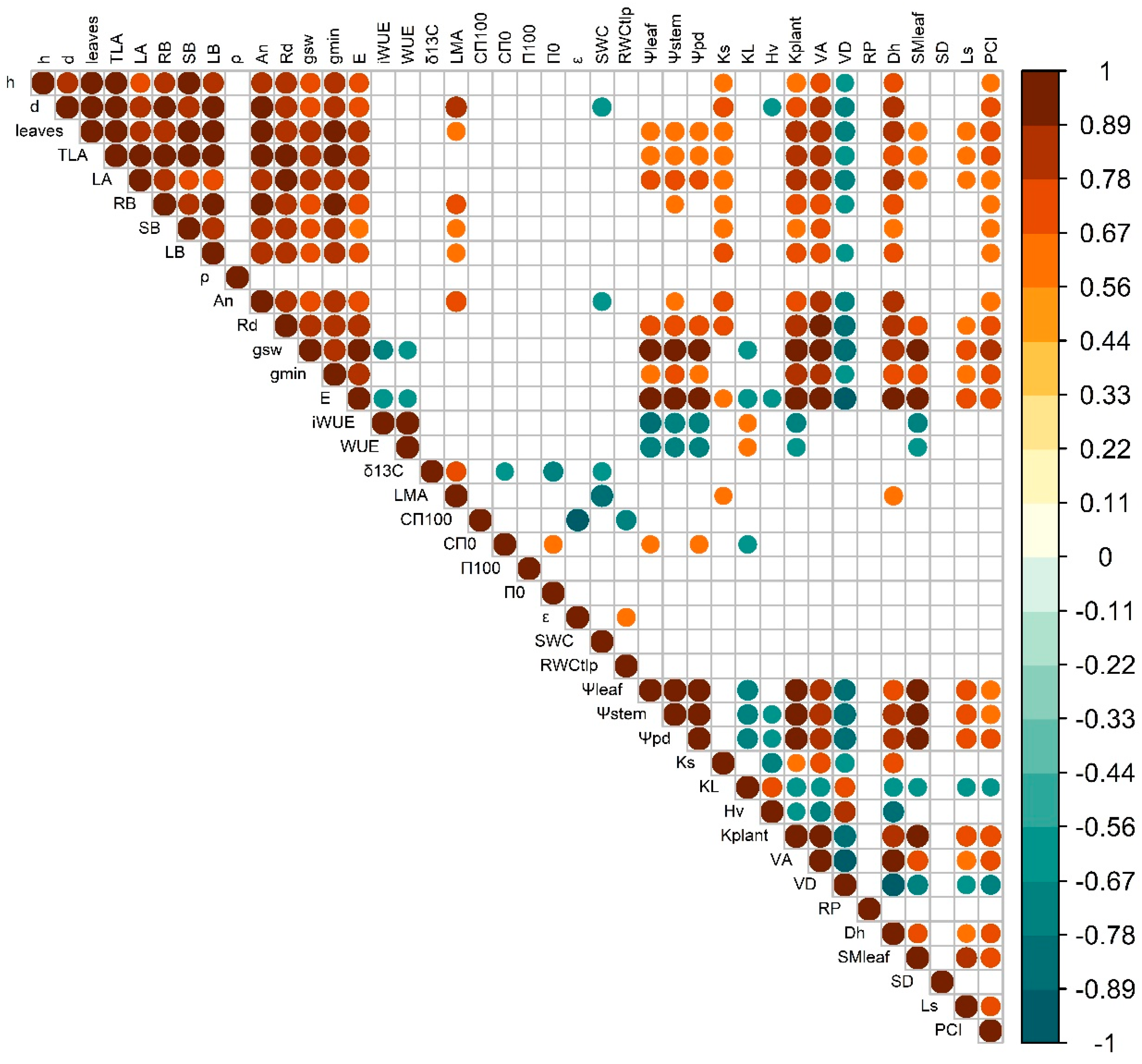

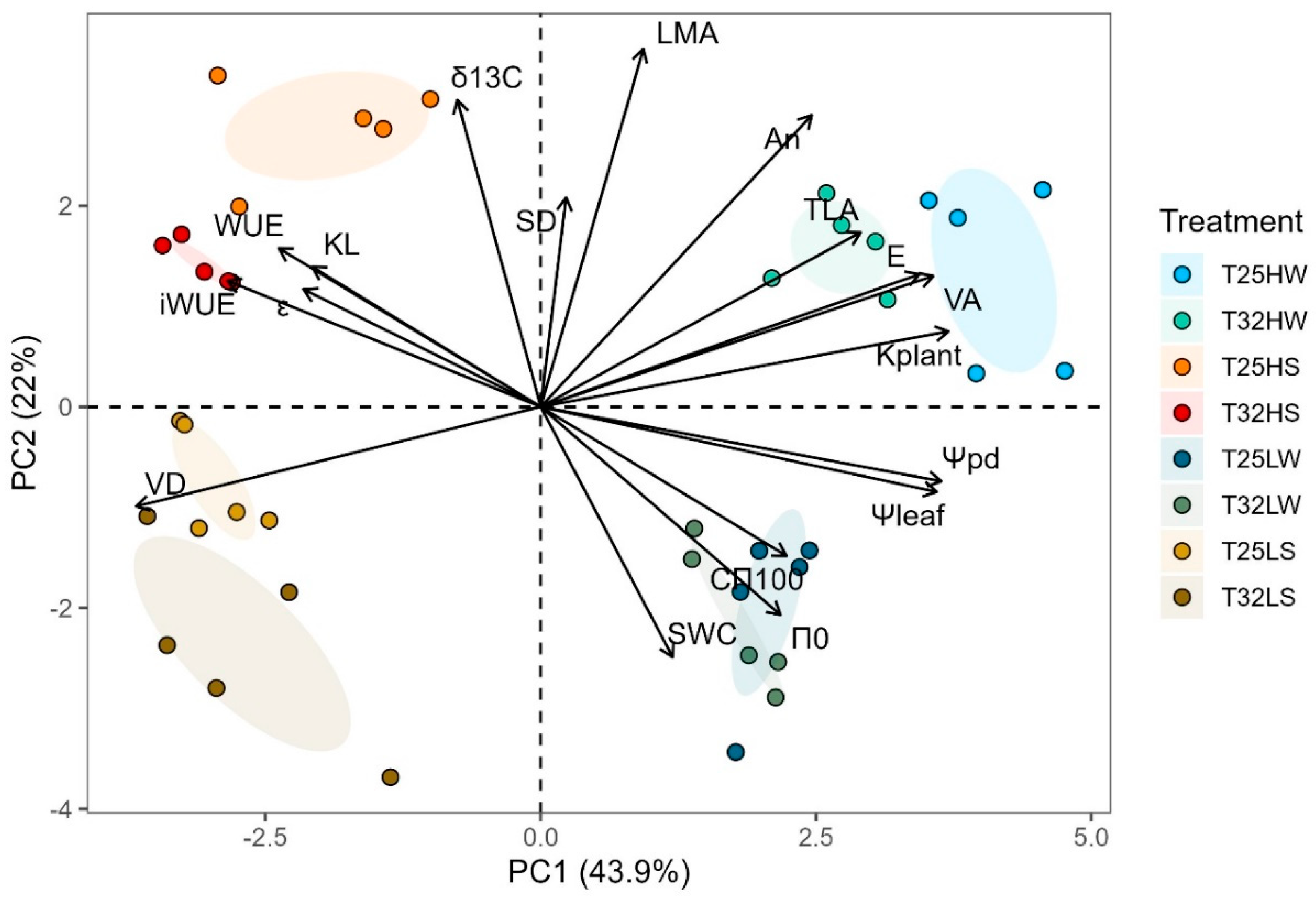

Correlations Among Traits and Principal Components Analysis (PCA)

3. Discussion

Impact of Warming on Plant Morphology, Physiology and Anatomy at High and Low Irradiance

Impact of Warming and Water Deficit at High and Low Light Intensity

Phenotypic Plasticity and Regeneration Niche of Beech Seedlings Under Multi-Stress Factors

4. Materials and Methods

Plant Material, Growth Conditions and Treatments

Growth and Biomass Allocation

Gas Exchange and Water Use Efficiency

Stomatal Traits and Carbon Isotope Composition (δ13C)

Minimum Leaf Conductance or Residual Conductance (gmin)

Pressure Volume Curves and Relate Traits

Predawn and Midday Water Potentials

Hydraulic Conductivity and Huber Value

Stem Xylem Anatomy

Trait Variation and Plasticity

Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Symbol | Level for PPi | Definition | Values units |

| h | Plant | Plant height | (cm) |

| d | Plant | Plant diameter | (mm) |

| leaves | Plant | Number of fully developed leaves | (nº) |

| TLA | Plant | Total plant leaf area | (cm2) |

| LA | Leaf GE relations | Average leaf area | (cm2) |

| RB | Plant | Root biomass | (g) |

| SB | Plant | Shoot biomass | (g) |

| LB | Plant | Leaf biomass | (g) |

| ρ | Plant | Wood density | (g cm-3) |

| An | Leaf GE relations | Leaf net assimilation rate | (μmol CO2 m-2 s-1) |

| Rl | Leaf GE relations | Leaf respiration in the light | (μmol CO2 m-2 s-1) |

| gsw | Leaf GE relations | Leaf stomatal conductance to water vapour | (mol H2O m-2 s-1) |

| gmin | Leaf GE relations | Leaf minimum conductance to water vapour | (mmol H2O m-2 s-1) |

| E | Leaf GE relations | Leaf transpiration | (mol H2O m-2 s-1) |

| iWUE | Not used for PPi | Intrinsic water use efficiency | (μmol CO2 mol-1 H2O) |

| WUE | Not used for PPi | Water use efficiency | (μmol CO2 mol-1 H2O) |

| δ13C | Not used for PPi | Carbon isotope composition | (‰) |

| LMA | Leaf GE relations | Leaf mass per area | (g m-2) |

| SD | Stomatal anatomy | Stomatal density | (nº stomata per mm2) |

| Ls | Stomatal anatomy | Stomatal length | (μm) |

| PCI | Stomatal anatomy | Potential conductance index | (μm2 mm-2 10-4) |

| Ws | Stomatal anatomy | Stomatal complex width | (μm) |

| Pls | Stomatal anatomy | Stomatal pore length | (μm) |

| GWs | Stomatal anatomy | Guard cell width | (μm) |

| C_Π100(CFT) | Leaf water relations | Leaf capacitance at full turgor | (MPa-1) |

| C_Π0 (CTLP) | Leaf water relations | Leaf capacitance at turgor loss point | (MPa-1) |

| Π100 (ΨFT) | Leaf water relations | Leaf osmotic potential at full turgor | (MPa) |

| Π0 (ΨTLP) | Leaf water relations | Leaf turgor loss point | (MPa) |

| εleaf | Leaf water relations | Leaf maximum Young's modulus of elasticity | (MPa) |

| RWCTLP | Leaf water relations | Relative water content at the turgor loss point | (%) |

| SWC | Leaf water relations | Leaf saturated water content | (g g-1) |

| Ψleaf | Leaf water relations | Leaf midday water potential | (MPa) |

| Ψstem | Leaf water relations | Stem midday water potential | (MPa) |

| Ψpd | Not used for PPi | Predawn water potential | (MPa) |

| SMleaf | Not used for PPi | Leaf safety margin | (MPa) |

| Anisohydry | Plant | Ratio Ψleaf to Ψpd | (dimensionless) |

| KS | Stem | Hydraulic specific conductivity | (kg m-1 s-1 Mpa-1) |

| KL | Stem | Leaf hydraulic conductivity | (mmol m-1 s-1 Mpa-1) |

| Hv | Plant | Huber value | (m2 m-2) |

| kplant | Plant | Plant hydraulic conductance | (mmol m-2 s-1 Mpa-1) |

| VA | Stem | Average vessel lumen area | (μm2) |

| VD | Stem | Vessel density | (nº vessels per mm2) |

| RP | Stem | Xylem area occupied by radial parenchyma | (%) |

| Dh | Not used for PPi | Hydraulic diameter | (μm) |

Appendix A

| Group of variables | Measured variables | Well-watered | Water deficit | ||

| T25 | T32 | T25 | T32 | ||

| Response to Light (HW vs LW) | Response to Light (HW vs LW) | Response to Light (HS vs LS) | Response to Light (HS vs LS) | ||

| Plant level | 10 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.56 |

| Stem | 6 | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.26 |

| Leaf (PV + GE) | 13 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.21 |

| Leaf hydric relations | 6 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Leaf GE relations | 7 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.29 |

| Overall | 29 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.35 |

| Group of variables | Measured variables | High light | Low light | ||

| T25 | T32 | T25 | T32 | ||

| Response to Water (HW vs HS) | Response to Water (HW vs HS) | Response to Light (HS vs LS) | Response to Light (HS vs LS) | ||

| Full plant | 10 | 0.67 | 0.57 | Full plant | 10 |

| Stem | 7 | 0.51 | 0.32 | Stem | 7 |

| Leaf (PV + GE) | 12 | 0.37 | 0.41 | Leaf (PV + GE) | 12 |

| Leaf water relations | 6 | 0.33 | 0.16 | Leaf water relations | 6 |

| Leaf GE relations | 6 | 0.39 | 0.61 | Leaf GE relations | 6 |

| Overall | 29 | 0.50 | 0.44 | Overall | 29 |

| Growth temperature | T25 | T32 | |||||||

| Treatment | HW | HS | LW | LS | HW | HS | LW | LS | |

| Sample size (n) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| h | (cm) | 61.9 ± 2.3 | 28.4 ± 1.6 | 18.9 ± 1.2 | 11.3 ± 0.5 | 63.1 ± 3.9 | 27.2 ± 0.8 | 26.2 ± 2.3 | 16.3 ± 1.6 |

| d | (mm) | 12.6 ± 0.2 | 9.0 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.2 |

| leaves | (nº) | 23 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | 10 ± 2 | 3 ± 0 | 41 ± 3 | 16 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 | 10 ± 0 |

| TLA | (cm2) | 1881.76 ± 113.43 | 214.56 ± 8.03 | 165.04 ± 54.89 | 31.34 ± 8.24 | 986.67 ± 68.17 | 328.22 ± 31.02 | 273.95 ± 26.37 | 86.74 ± 22.89 |

| LA | (cm2) | 36.16 ± 2.02 | 17.88 ± 1.71 | 13.37 ± 1.48 | 9.62 ± 0.42 | 25.41 ± 2.98 | 11.51 ± 1.1 | 13.65 ± 1.37 | 9.28 ± 0.71 |

| RB | (g) | 30.9 ± 3.1 | 8 ± 1.3 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 14.5 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| SB | (g) | 16.3 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 8.6 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| LB | (g) | 49.7 ± 4.1 | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 3 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 21.2 ± 2.2 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 1 ± 0.2 |

| TB | (g) | 95.8 ± 6.5 | 19.3 ± 2.5 | 6.6 ± 1.1 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 46.9 ± 2.6 | 14.8 ± 1 | 9 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 0.5 |

| RB | (%) | 32.4 ± 2.6 | 38.6 ± 1.9 | 43.2 ± 4 | 41.8 ± 1.6 | 32.7 ± 3 | 30.8 ± 0.8 | 28.7 ± 2 | 34.9 ± 2.2 |

| SB | (%) | 15.9 ± 1.1 | 13.1 ± 0.3 | 10.7 ± 2 | 11.7 ± 2.5 | 17.1 ± 1.1 | 24.7 ± 1.2 | 18.1 ± 0.9 | 22.6 ± 3.8 |

| LB | (%) | 50 ± 1.3 | 44.9 ± 1 | 43.8 ± 1.4 | 46.5 ± 1.3 | 45.3 ± 4.1 | 40.3 ± 2 | 55 ± 1 | 42.4 ± 2.7 |

| Ks | (kg m-1 s-1 Mpa-1) | 25.94 ± 4.21 | 14.78 ± 0.92 | 14.56 ± 0.91 | 6.11 ± 1.31 | 22.09 ± 2.58 | 16.85 ± 2.23 | 15.86 ± 1.93 | 7.19 ± 2.61 |

| KL | (mmol m-1 s-1 Mpa-1) | 0.62 ± 0.11 | 5.26 ± 0.15 | 1.72 ± 0.32 | 2.84 ± 0.45 | 0.81 ± 0.12 | 1.37 ± 0.07 | 0.44 ± 0.08 | 1.62 ± 0.23 |

| Kplant | (mmol m-2 s-1 Mpa-1) | 2.46 ± 0.31 | 0.96 ± 0.13 | 1.92 ± 0.29 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 2.93 ± 0.12 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 1.96 ± 0.06 | 0.18 ± 0.03 |

| HV | (cm2 m-2) | 7.6 ± 1 | 59.8 ± 6.4 | 21.9 ± 3.8 | 64.5 ± 12.1 | 7.2 ± 0.8 | 9.9 ± 0.9 | 6 ± 0.7 | 26 ± 3.2 |

| LMA | (g m-2) | 82.9 ± 1.4 | 90.2 ± 2.1 | 62.2 ± 1.4 | 49.6 ± 1.5 | 80.1 ± 1.9 | 43.9 ± 1.1 | 49.5 ± 0.7 | 40.5 ± 0.7 |

| An | (μmol m-2 s-1) | 8.4 ± 0.5 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 7.4 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| Rl | (μmol m-2 s-1) | 0.75 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.41 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.72 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.03 |

| gsw | (mmol m-2 s-1) | 232.7 ± 46.7 | 101.9 ± 13 | 124.8 ± 24 | 33.2 ± 3 | 271.4 ± 14 | 31.3 ± 0.5 | 171 ± 6.8 | 17.2 ± 3.2 |

| gmin | (mmol m-2 s-1) | 2.36 ± 0.06 | 1.75 ± 0.05 | 1.88 ± 0.02 | 1.35 ± 0.01 | 5.57 ± 0.08 | 1.78 ± 0.1 | 2.24 ± 0.01 | 1.81 ± 0.05 |

| E | (mol m-2 s-1) | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| iWUE | (μmol mol-1) | 38.8 ± 5.3 | 63.1 ± 0.9 | 25.4 ± 0.4 | 73.2 ± 4.7 | 27.8 ± 2.6 | 110.4 ± 1.7 | 14.7 ± 1.9 | 36.5 ± 5 |

| WUE | (μmol mol-1) | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0 | 4 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| δ13C | (‰) | -29.8 ± 0.5 | -27.6 ± 0.7 | -32.3 ± 0.7 | -30.9 ± 0.8 | -31.5 ± 0.4 | -30.4 ± 0.7 | -34.8 ± 0.3 | -33.5 ± 0.6 |

References

- IPCC Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report.Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kobe, R.K.; Pacala, S.W.; Silander Jr., J.A.; Canham, C.D. Juvenile Tree Survivorship as a Component of Shade Tolerance. Ecological Applications 1995, 5, 517–532. [CrossRef]

- Pineda-García, F.; Paz, H.; Meinzer, F.C. Drought Resistance in Early and Late Secondary Successional Species from a Tropical Dry Forest: The Interplay between Xylem Resistance to Embolism, Sapwood Water Storage and Leaf Shedding. Plant Cell Environ 2013, 36, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Matesanz, S.; Guilhaumon, F.; Araújo, M.B.; Balaguer, L.; Benito-Garzón, M.; Cornwell, W.; Gianoli, E.; van Kleunen, M.; Naya, D.E.; et al. The Effects of Phenotypic Plasticity and Local Adaptation on Forecasts of Species Range Shifts under Climate Change. Ecol Lett 2014, 17, 1351–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito Garzón, M.; Robson, T.M.; Hampe, A. ΔTraitSDMs: Species Distribution Models That Account for Local Adaptation and Phenotypic Plasticity. New Phytologist 2019, 222, 1757–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Valiente, J.A.; González-Martínez, S.C.; Robledo-Arnuncio, J.J.; Matesanz, S.; Anadon-Rosell, A.; Martínez-Vilalta, J.; López, R.; Cano-Martín, F.J. Genetically Based Trait Coordination and Phenotypic Plasticity of Growth, Gas Exchange, Allometry, and Hydraulics across the Distribution Range of Pinus Pinaster. New Phytologist 2025, 246, 984–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, P.B. The World-Wide ‘Fast–Slow’ Plant Economics Spectrum: A Traits Manifesto. Journal of Ecology 2014, 102, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavanetto, N.; Carmona, C.P.; Laanisto, L.; Niinemets, Ü.; Puglielli, G. Trait Dimensions of Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Woody Plants of the Northern Hemisphere. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Niinemets, Ü. Shade Tolerance, a Key Plant Feature of Complex Nature and Consequences. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 2008, 39, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.I.; Díez, B.; Kempes, C.P.; West, G.B.; Marquet, P.A. A General Theory for Temperature Dependence in Biology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2119872119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarathunge, D.P.; Drake, J.E.; Tjoelker, M.G.; López, R.; Pfautsch, S.; Vårhammar, A.; Medlyn, B.E. The Temperature Optima for Tree Seedling Photosynthesis and Growth Depend on Water Inputs. Glob Chang Biol 2020, 26, 2544–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, D.A.; Oren, R. Differential Responses to Changes in Growth Temperature between Trees from Different Functional Groups and Biomes: A Review and Synthesis of Data. Tree Physiol 2010, 30, 669–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B.; Sendall, K.M.; Rice, K.; Rich, R.L.; Stefanski, A.; Hobbie, S.E.; Montgomery, R.A. Geographic Range Predicts Photosynthetic and Growth Response to Warming in Co-Occurring Tree Species. Nat Clim Chang 2015, 5, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamori, W.; Hikosaka, K.; Way, D.A. Temperature Response of Photosynthesis in C3, C4, and CAM Plants: Temperature Acclimation and Temperature Adaptation. Photosynth Res 2014, 119, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.; Xu, Y.; Harmens, H.; Duan, H.; Feng, Z.; Hayes, F.; Sharps, K.; Radbourne, A.; Tarvainen, L. Reduced Photosynthetic Thermal Acclimation Capacity under Elevated Ozone in Poplar (Populus Tremula) Saplings. Glob Chang Biol 2021, 27, 2159–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, O.K.; Tjoelker, M.G. Thermal Acclimation and the Dynamic Response of Plant Respiration to Temperature. Trend Plant Sci 2003, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorter, H.; Niinemets, Ü.; Poorter, L.; Wright, I.J.; Villar, R. Causes and Consequences of Variation in Leaf Mass per Area (LMA): A Meta-Analysis. New Phytologist 2009, 182, 565–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westoby, M.; Falster, D.S.; Moles, A.T.; Vesk, P.A.; Wright, I.J. Plant Ecological Strategies: Some Leading Dimensions of Variation Between Species. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 2002, 33, 125–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, I.; Reich, P.; Westoby, M.; Ackerly, D.; Baruch, Z.; Bongers, F.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Cornelissen, J.; Diemer, M.; Flexas, J.; et al. The World-Wide Leaf Economics Spectrum. Nature 2004, 428, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchin, R.M.; Backes, D.; Ossola, A.; Leishman, M.R.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Ellsworth, D.S. Extreme Heat Increases Stomatal Conductance and Drought-Induced Mortality Risk in Vulnerable Plant Species. Glob Chang Biol 2022, 28, 1133–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, A.; Sevanto, S.; Close, J.D.; Nicotra, A.B. The Influence of Leaf Size and Shape on Leaf Thermal Dynamics: Does Theory Hold up under Natural Conditions? Plant Cell Environ 2017, 40, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; George-Jaeggli, B.; Borrell, A.; Jordan, D.; Koller, F.; Al-Salman, Y.; Ghannoum, O.; Cano, F.J. Coordination of Stomata and Vein Patterns with Leaf Width Underpins Water-Use Efficiency in a C4 Crop. Plant Cell Environ 2022, 45, 1612–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, K.Y.; Uddling, J.; De Kauwe, M.G. Temperature Responses of Photosynthesis and Respiration in Evergreen Trees from Boreal to Tropical Latitudes. New Phytologist 2022, 234, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, P.; Sendall, K.; Stefanski, A.; Wei, X.; Rich, R.; Montgomery, R. Boreal and Temperate Trees Show Strong Acclimation of Respiration to Warming. Nature 2016, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghannoum, O.; Phillips, N.; SEARS, M.; LOGAN, B.; Lewis, J.; Conroy, J.; Tissue, D. Photosynthetic Responses of Two Eucalypts to Industrial-Age Changes in Atmospheric [CO2] and Temperature: Eucalyptus Photosynthesis in Past and Future Climates. Plant Cell and Environment - PLANT CELL ENVIRON 2010.

- Kumarathunge, D.P.; Medlyn, B.E.; Drake, J.E.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Aspinwall, M.J.; Battaglia, M.; Cano, F.J.; Carter, K.R.; Cavaleri, M.A.; Cernusak, L.A.; et al. Acclimation and Adaptation Components of the Temperature Dependence of Plant Photosynthesis at the Global Scale. New Phytologist 2019, 222, 768–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.G.; Dukes, J.S. Plant Respiration and Photosynthesis in Global-Scale Models: Incorporating Acclimation to Temperature and 2. Glob Chang Biol 2013, 19, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.; Ingwers, M.; McGuire, M.A.; Teskey, R.O. Stomatal Conductance Increases with Rising Temperature. Plant Signal Behav 2017, 12, e1356534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, J.E.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Vårhammar, A.; Medlyn, B.E.; Reich, P.B.; Leigh, A.; Pfautsch, S.; Blackman, C.J.; López, R.; Aspinwall, M.J.; et al. Trees Tolerate an Extreme Heatwave via Sustained Transpirational Cooling and Increased Leaf Thermal Tolerance. Glob Chang Biol 2018, 24, 2390–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kauwe, M.G.; Medlyn, B.E.; Pitman, A.J.; Drake, J.E.; Ukkola, A.; Griebel, A.; Pendall, E.; Prober, S.; Roderick, M. Examining the Evidence for Decoupling between Photosynthesis and transpiration during Heat Extremes. Biogeosciences 2019, 16, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Liu, R.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Slot, M. Contrasting Responses of Two C4 Desert Shrubs to Drought but Consistent Decoupling of Photosynthesis and Stomatal Conductance at High Temperature. Environ Exp Bot 2023, 209, 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, H.; Cernusak, L.A.; Saurer, M.; Gessler, A.; Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Lehmann, M.M. Uncoupling of Stomatal Conductance and Photosynthesis at High Temperatures: Mechanistic Insights from Online Stable Isotope Techniques. New Phytologist 2024, 241, 2366–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbeck, L.C.; Schuler, P.; Lehmann, M.M.; Mas, E.; Mekarni, L.; Pivovaroff, A.L.; Turberg, P.; Grossiord, C. Increasing Temperature and Vapour Pressure Deficit Lead to Hydraulic Damages in the Absence of Soil Drought. Plant Cell Environ 2022, 45, 3275–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogren, W.L. Photorespiration: Pathways, Regulation, And. Annu Rev Plant Biol 1984, 35, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Mittler, R. Reactive Oxygen Species and Temperature Stresses: A Delicate Balance between Signaling and Destruction. Physiol Plant 2006, 126, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, A.M.; Woodward, F.I. The Role of Stomata in Sensing and Driving Environmental Change. Nature 2003, 424, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, P.; Brodribb, T. Stomatal Control and Water Transport in the Xylem. In Vascular Transport in Plants; 2005; pp. 69–89 ISBN 9780120884575.

- Choat, B.; Brodribb, T.J.; Brodersen, C.R.; Duursma, R.A.; López, R.; Medlyn, B.E. Triggers of Tree Mortality under Drought. Nature 2018, 558, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantova, M.; Cochard, H.; Burlett, R.; Delzon, S.; King, A.; Rodriguez-Dominguez, C.M.; Ahmed, M.A.; Trueba, S.; Torres-Ruiz, J.M. On the Path from Xylem Hydraulic Failure to Downstream Cell Death. New Phytologist 2023, 237, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossiord, C.; Sevanto, S.; Borrego, I.; Chan, A.M.; Collins, A.D.; Dickman, L.T.; Hudson, P.J.; McBranch, N.; Michaletz, S.T.; Pockman, W.T.; et al. Tree Water Dynamics in a Drying and Warming World. Plant Cell Environ 2017, 40, 1861–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, D.A.; Domec, J.-C.; Jackson, R.B. Elevated Growth Temperatures Alter Hydraulic Characteristics in Trembling Aspen (Populus Tremuloides) Seedlings: Implications for Tree Drought Tolerance. Plant Cell Environ 2013, 36, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.K.; Scoffoni, C.; Sack, L. The Determinants of Leaf Turgor Loss Point and Prediction of Drought Tolerance of Species and Biomes: A Global Meta-Analysis. Ecol Lett 2012, 15, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Way, D.A.; Sadok, W. Systemic Effects of Rising Atmospheric Vapor Pressure Deficit on Plant Physiology and Productivity. Glob Chang Biol 2021, 27, 1704–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Cadahía, E.; Fernández de Simón, B. Specific Leaf Metabolic Changes That Underlie Adjustment of Osmotic Potential in Response to Drought by Four Quercus Species. Tree Physiol 2021, 41, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maherali, H.; DeLucia, E.H. Xylem Conductivity and Vulnerability to Cavitation of Ponderosa Pine Growing in Contrasting Climates. Tree Physiol 2000, 20, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCulloh, K.A.; Petitmermet, J.; Stefanski, A.; Rice, K.E.; Rich, R.L.; Montgomery, R.A.; Reich, P.B. Is It Getting Hot in Here? Adjustment of Hydraulic Parameters in Six Boreal and Temperate Tree Species after 5 Years of Warming. Glob Chang Biol 2016, 22, 4124–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.S.; Montagu, K.D.; Conroy, J.P. Changes in Wood Density of Eucalyptus Camaldulensis Due to Temperature—the Physiological Link between Water Viscosity and Wood Anatomy. For Ecol Manage 2004, 193, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.S.; Montagu, K.D.; Conroy, J.P. Temperature Effects on Wood Anatomy, Wood Density, Photosynthesis and Biomass Partitioning of Eucalyptus Grandis Seedlings. Tree Physiol 2007, 27, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellin, A.; Kupper, P. Temperature, Light and Leaf Hydraulic Conductance of Little-Leaf Linden (Tilia Cordata) in a Mixed Forest Canopy. Tree Physiol 2007, 27, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.; French, B.; Prior, L. Have Plants Evolved to Self-Immolate? Front Plant Sci 2014, 5, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Amthor, J.S.; Duursma, R.A.; O’Grady, A.P.; Choat, B.; Tissue, D.T. Carbon Dynamics of Eucalypt Seedlings Exposed to Progressive Drought in Elevated [CO2] and Elevated Temperature. Tree Physiol 2013, 33, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Atkin, O.K.; Robson, T.M.; Zaragoza-Castells, J.; Gil, L.; Aranda, I. Thermal Acclimation of Leaf Dark Respiration of Beech Seedlings Experiencing Summer Drought in High and Low Light Environments. Tree Physiol 2010, 30, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osonubi, O.; Davies, W.J. The Influence of Water Stress on the Photosynthetic Performance and Stomatal Behaviour of Tree Seedlings Subjected to Variation in Temperature and Irradiance. Oecologia 1980, 45, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, F.J.; Sánchez-Gómez, D.; Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Warren, C.R.; Gil, L.; Aranda, I. Effects of Drought on Mesophyll Conductance and Photosynthetic Limitations at Different Tree Canopy Layers. Plant Cell Environ 2013, 36, 1961–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, F.J.; López, R.; Warren, C.R. Implications of the Mesophyll Conductance to CO2 for Photosynthesis and Water-Use Efficiency during Long-Term Water Stress and Recovery in Two Contrasting Eucalyptus Species. Plant Cell Environ 2014, 37, 2470–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, M.K.; Scoffoni, C.; Ardy, R.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Cao, K.; Sack, L. Rapid Determination of Comparative Drought Tolerance Traits: Using an Osmometer to Predict Turgor Loss Point. Methods Ecol Evol 2012, 3, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salman, Y.; Ghannoum, O.; Cano, F.J. Elevated [CO2] Negatively Impacts C4 Photosynthesis under Heat and Water Stress without Penalizing Biomass. J Exp Bot 2023, 74, 2875–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochard, H.; Pimont, F.; Ruffault, J.; Martin-StPaul, N. SurEau: A Mechanistic Model of Plant Water Relations under Extreme Drought. Ann For Sci 2021, 78, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R.; Cano, F.J.; Martin-StPaul, N.K.; Cochard, H.; Choat, B. Coordination of Stem and Leaf Traits Define Different Strategies to Regulate Water Loss and Tolerance Ranges to Aridity. New Phytologist 2021, 230, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, A.-C.; Burghardt, M.; Alfarhan, A.; Bueno, A.; Hedrich, R.; Leide, J.; Thomas, J.; Riederer, M. Effectiveness of Cuticular Transpiration Barriers in a Desert Plant at Controlling Water Loss at High Temperatures. AoB Plants 2016, 8, plw027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duursma, R.A.; Blackman, C.J.; Lopéz, R.; Martin-StPaul, N.K.; Cochard, H.; Medlyn, B.E. On the Minimum Leaf Conductance: Its Role in Models of Plant Water Use, and Ecological and Environmental Controls. New Phytologist 2019, 221, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.; Alfarhan, A.; Arand, K.; Burghardt, M.; Deininger, A.-C.; Hedrich, R.; Leide, J.; Seufert, P.; Staiger, S.; Riederer, M. Effects of Temperature on the Cuticular Transpiration Barrier of Two Desert Plants with Water-Spender and Water-Saver Strategies. J Exp Bot 2019, 70, 1613–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergarechea, M.; del Río, M.; Gordo, J.; Martín, R.; Cubero, D.; Calama, R. Spatio-Temporal Variation of Natural Regeneration in Pinus Pinea and Pinus Pinaster Mediterranean Forests in Spain. Eur J For Res 2019, 138, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamerlynck, E.; Knapp, A.K. Photosynthetic and Stomatal Responses to High Temperature and Light in Two Oaks at the Western Limit of Their Range. Tree Physiol 1996, 16, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küppers, M.; Schneider, H. Leaf Gas Exchange of Beech (Fagus Sylvatica L.) Seedlings in Lightflecks: Effects of Fleck Length and Leaf Temperature in Leaves Grown in Deep and Partial Shade. Trees 1993, 7, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachofen, C.; D’Odorico, P.; Buchmann, N. Light and VPD Gradients Drive Foliar Nitrogen Partitioning and Photosynthesis in the Canopy of European Beech and Silver Fir. Oecologia 2020, 192, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, H.B.H.; Tardieu, F. Quantitative Analysis of the Combined Effects of Temperature, Evaporative Demand and Light on Leaf Elongation Rate in Well-Watered Field and Laboratory-Grown Maize Plants. J Exp Bot 1996, 47, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin III, F.S.; Bloom, A.J.; Field, C.B.; Waring, R.H. Plant Responses to Multiple Environmental Factors: Physiological Ecology Provides Tools for Studying How Interacting Environmental Resources Control Plant Growth. Bioscience 1987, 37, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Pearcy, R.W. Drought Can Be More Critical in the Shade than in the Sun: A Field Study of Carbon Gain and Photo-Inhibition in a Californian Shrub during a Dry El Niño Year. Plant Cell Environ 2002, 25, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Robson, T.; Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Valladares, F. Limited Capacity to Cope with Excessive Light in the Open and with Seasonal Drought in the Shade in Mediterranean Ilex Aquifolium Populations. Trees 2008, 22, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Gil, L.; Pardos, J. Effects of Thinning in a Pinus Sylvestris L. Stand on Foliar Water Relations of Fagus Sylvatica L. Seedlings Planted within the Pinewood. Trees 2001, 15, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Gil, L.; Pardos, J.A. Physiological Responses of Fagus Sylvatica L. Seedlings under Pinus Sylvestris L. and Quercus Pyrenaica Willd. Overstories. For Ecol Manage 2002, 162, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunel, C.; Garnier, E.; Joffre, R.; Kazakou, E.; Quested, H.; Grigulis, K.; Lavorel, S.; Ansquer, P.; Castro, H.; Cruz, P.; et al. Leaf Traits Capture the Effects of Land Use Changes and Climate on Litter Decomposability of Grasslands across Europe. Ecology 2009, 90, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschaplinski, T.J.; Gebre, G.M.; Shirshac, T.L. Osmotic Potential of Several Hardwood Species as Affected by Manipulation of Throughfall Precipitation in an Upland Oak Forest during a Dry Year. Tree Physiol 1998, 18, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, Ü. Global-Scale Climatic Controls of Leaf Dry Mass per Area, Density, and Thickness in Trees and Shrubs. Ecology 2001, 82, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Bergasa, L.F.; Gil, L.; Pardos, J.A. Effects of Relative Irradiance on the Leaf Structure of Fagus Sylvatica L. Seedlings Planted in the Understory of a Pinus Sylvestris L. Stand after Thinning. Ann. For. Sci. 2001, 58, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Pardos, J.A.; Gil, L.; Aranda, I. Ability to Avoid Water Stress in Seedlings of Two Oak Species Is Lower in a Dense Forest Understory than in a Medium Canopy Gap. For Ecol Manage 2008, 255, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, T.D. Effects of Moderate Heat Stress on Photosynthesis: Importance of Thylakoid Reactions, Rubisco Deactivation, Reactive Oxygen Species, and Thermotolerance Provided by Isoprene. Plant Cell Environ 2005, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, D.J.; Bauerle, W.L. Inhibition and Acclimation of C3 Photosynthesis to Moderate Heat: A Perspective from Thermally Contrasting Genotypes of Acer Rubrum (Red Maple). Tree Physiol 2007, 27, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvucci, M.E.; Crafts-Brandner, S.J. Mechanism for Deactivation of Rubisco under Moderate Heat Stress. Physiol Plant 2004, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciais, P.; Reichstein, M.; Viovy, N.; Granier, A.; Ogée, J.; Allard, V.; Aubinet, M.; Buchmann, N.; Bernhofer, C.; Carrara, A.; et al. Europe-Wide Reduction in Primary Productivity Caused by the Heat and Drought in 2003. Nature 2005, 437, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumrani, K.; Bhatia, V.S. Interactive Effect of Temperature and Water Stress on Physiological and Biochemical Processes in Soybean. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2019, 25, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. Abiotic Stress, the Field Environment and Stress Combination. Trends Plant Sci 2006, 11, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Rivero, R.M.; Shulaev, V.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Abiotic and Biotic Stress Combinations. New Phytologist 2014, 203, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Mittler, R. Plant Responses to Multifactorial Stress Combination. New Phytologist 2022, 234, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Sinclair, T.R.; Zhu, M.; Messina, C.D.; Cooper, M.; Hammer, G.L. Temperature Effect on Transpiration Response of Maize Plants to Vapour Pressure Deficit. Environ Exp Bot 2012, 78, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadok, W.; Lopez, J.R.; Smith, K.P. Transpiration Increases under High-Temperature Stress: Potential Mechanisms, Trade-Offs and Prospects for Crop Resilience in a Warming World. Plant Cell Environ 2021, 44, 2102–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, S.; Guha, A.; Kholova, J.; Pandravada, A.; Messina, C.D.; Cooper, M.; Vadez, V. Maize, Sorghum, and Pearl Millet Have Highly Contrasting Species Strategies to Adapt to Water Stress and Climate Change-like Conditions. Plant Science 2020, 295, 110297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seversike, T.M.; Sermons, S.M.; Sinclair, T.R.; Carter Jr, T.E.; Rufty, T.W. Temperature Interactions with Transpiration Response to Vapor Pressure Deficit among Cultivated and Wild Soybean Genotypes. Physiol Plant 2013, 148, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riar, M.K.; Sinclair, T.R.; Prasad, P.V.V. Persistence of Limited-Transpiration-Rate Trait in Sorghum at High Temperature. Environ Exp Bot 2015, 115, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, T.; Wankmüller, F.J.P.; Sadok, W.; Carminati, A. Transpiration Response to Soil Drying versus Increasing Vapor Pressure Deficit in Crops: Physical and Physiological Mechanisms and Key Plant Traits. J Exp Bot 2023, 74, 4789–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.; Bartlett, M.; Buckley, T. The Poorly-Explored Stomatal Response to Temperature at Constant Evaporative Demand. Plant Cell Environ 2024, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Sengupta, S.; Fritschi, F.B.; Azad, R.K.; Nechushtai, R.; Mittler, R. The Impact of Multifactorial Stress Combination on Plant Growth and Survival. New Phytologist 2021, 230, 1034–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Peláez-Vico, M.Á.; Sinha, R.; Pascual, L.S.; Mittler, R. The Impact of Multifactorial Stress Combination on Plants, Crops, and Ecosystems: How Should We Prepare for What Comes Next? The Plant Journal 2024, 117, 1800–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B.; Oleksyn, J. Climate Warming Will Reduce Growth and Survival of Scots Pine except in the Far North. Ecol Lett 2008, 11, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertin, T.M.; McGuire, M.A.; Teskey, R.O. Higher Growth Temperatures Decreased Net Carbon Assimilation and Biomass Accumulation of Northern Red Oak Seedlings near the Southern Limit of the Species Range. Tree Physiol 2011, 31, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelder, H.A.; Poorter, L.; Sterck, F.J. Wood Mechanics, Allometry, and Life-History Variation in a Tropical Rain Forest Tree Community. New Phytologist 2006, 171, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacke, U.G.; Sperry, J.S.; Pockman, W.T.; Davis, S.D.; McCulloh, K.A. Trends in Wood Density and Structure Are Linked to Prevention of Xylem Implosion by Negative Pressure. Oecologia 2001, 126, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, J. Evolution of Water Transport and Xylem Structure. Int J Plant Sci 2003, 164, S115–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roderick, M.L.; Berry, S.L. Linking Wood Density with Tree Growth and Environment: A Theoretical Analysis Based on the Motion of Water. New Phytologist 2001, 149, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochard, H.; Martin, R.; Gross, P.; Bogeat-Triboulot, M.B. Temperature Effects on Hydraulic Conductance and Water Relations of Quercus Robur L. J Exp Bot 2000, 51, 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, I.C.; Leuschner, C. Leaf Size and Leaf Area Index in Fagus Sylvatica Forests: Competing Effects of Precipitation, Temperature, and Nitrogen Availability. Ecosystems 2008, 11, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Jiang, K.-Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.-X.; Ni, C.-Y.; Wang, Y.-L.; Teng, N.-J. The Effect of Experimental Warming on Leaf Functional Traits, Leaf Structure and Leaf Biochemistry in Arabidopsis Thaliana. BMC Plant Biol 2011, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, D.M. Transpiration and Leaf Temperature. Annu Rev Plant Biol 1968, 19, 211–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasini, D.E.; Koepke, D.F.; Bush, S.E.; Allan, G.J.; Gehring, C.A.; Whitham, T.G.; Day, T.A.; Hultine, K.R. Tradeoffs between Leaf Cooling and Hydraulic Safety in a Dominant Arid Land Riparian Tree Species. Plant Cell Environ 2022, 45, 1664–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorter, L.; McDonald, I.; Alarcón, A.; Fichtler, E.; Licona, J.-C.; Peña-Claros, M.; Sterck, F.; Villegas, Z.; Sass-Klaassen, U. The Importance of Wood Traits and Hydraulic Conductance for the Performance and Life History Strategies of 42 Rainforest Tree Species. New Phytologist 2010, 185, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencuccini, M.; Rosas, T.; Rowland, L.; Choat, B.; Cornelissen, H.; Jansen, S.; Kramer, K.; Lapenis, A.; Manzoni, S.; Niinemets, Ü.; et al. Leaf Economics and Plant Hydraulics Drive Leaf : Wood Area Ratios. New Phytologist 2019, 224, 1544–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.; Stocker, B.D.; Hofhansl, F.; Zhou, S.; Dieckmann, U.; Prentice, I.C. Towards a Unified Theory of Plant Photosynthesis and Hydraulics. Nat Plants 2022, 8, 1304–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šigut, L.; Holišová, P.; Klem, K.; Šprtová, M.; Calfapietra, C.; Marek, M. V; Špunda, V.; Urban, O. Does Long-Term Cultivation of Saplings under Elevated CO2 Concentration Influence Their Photosynthetic Response to Temperature? Ann Bot 2015, 116, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.; Maroco, J.; Pereira, J. Understanding Plant Responses to Drought - From Genes to the Whole Plant. Functional Plant Biology - FUNCT PLANT BIOL 2003, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameye, M.; Wertin, T.M.; Bauweraerts, I.; McGuire, M.A.; Teskey, R.O.; Steppe, K. The Effect of Induced Heat Waves on Inus Taeda and Uercus Rubra Seedlings in Ambient and Elevated CO2 Atmospheres. New Phytologist 2012, 196, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didion-Gency, M.; Vitasse, Y.; Buchmann, N.; Gessler, A.; Gisler, J.; Schaub, M.; Grossiord, C. Chronic Warming and Dry Soils Limit Carbon Uptake and Growth despite a Longer Growing Season in Beech and Oak. Plant Physiol 2024, 194, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; O’Grady, A.P.; Duursma, R.A.; Choat, B.; Huang, G.; Smith, R.A.; Jiang, Y.; Tissue, D.T. Drought Responses of Two Gymnosperm Species with Contrasting Stomatal Regulation Strategies under Elevated [CO2] and Temperature. Tree Physiol 2015, 35, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasini, D.E.; Koepke, D.F.; Grady, K.C.; Allan, G.J.; Gehring, C.A.; Whitham, T.G.; Cushman, S.A.; Hultine, K.R. Adaptive Trait Syndromes along Multiple Economic Spectra Define Cold and Warm Adapted Ecotypes in a Widely Distributed Foundation Tree Species. Journal of Ecology 2021, 109, 1298–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, A.-C.; Burghardt, M.; Riederer, M. The Ecophysiology of Leaf Cuticular Transpiration: Are Cuticular Water Permeabilities Adapted to Ecological Conditions? J Exp Bot 2017, 68, 5271–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billon, L.M.; Blackman, C.J.; Cochard, H.; Badel, E.; Hitmi, A.; Cartailler, J.; Souchal, R.; Torres-Ruiz, J.M. The DroughtBox: A New Tool for Phenotyping Residual Branch Conductance and Its Temperature Dependence during Drought. Plant Cell Environ 2020, 43, 1584–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, M.E.; Henry, C.; John, G.P.; Medeiros, C.D.; Pan, R.; Scoffoni, C.; Buckley, T.N.; Sack, L. Pinpointing the Causal Influences of Stomatal Anatomy and Behavior on Minimum, Operational, and Maximum Leaf Surface Conductance. Plant Physiol 2024, 196, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garen, J.C.; Michaletz, S.T. Temperature Governs the Relative Contributions of Cuticle and Stomata to Leaf Minimum Conductance. New Phytologist 2025, 245, 1911–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietsch, G.M.; Carlson, W.H.; Heins, R.D.; Faust, J.E. The Effect of Day and Night Temperature and Irradiance on Development of Catharanthus Roseus (L.) `Grape Cooler’. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science jashs 1995, 120, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotelli, M.; Rudolph, P.; Rennenberg, H.; Gessler, A. Irradiance and Temperature Affect the Competitive Interference of Blackberry on the Physiology of European Beech Seedlings. New Phytol 2005, 165, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, F.; Grace, J.; Borghetti, M. Adjustment of Tree Structure in Response to the Environment under Hydraulic Constraints. Funct Ecol 2002, 16, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addington, R.N.; Donovan, L.A.; Mitchell, R.J.; Vose, J.M.; Pecot, S.D.; Jack, S.B.; Hacke, U.G.; Sperry, J.S.; Oren, R. Adjustments in Hydraulic Architecture of Pinus Palustris Maintain Similar Stomatal Conductance in Xeric and Mesic Habitats. Plant Cell Environ 2006, 29, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochard, H.; Lemoine, D.; Dreyer, E. The Effects of Acclimation to Sunlight on the Xylem Vulnerability to Embolism in Fagus Sylvatica L. Plant Cell Environ 1999, 22, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. Significance of Temperature in Plant Life. In Plant Growth and Climate Change; 2006; pp. 48–69 ISBN 9780470988695.

- Menzel, A.; Sparks, T. Temperature and Plant Development: Phenology and Seasonality. In Plant Growth and Climate Change; 2006; pp. 70–95 ISBN 9780470988695.

- Weih, M.; Liu, H.; Colombi, T.; Keller, T.; Jäck, O.; Vallenback, P.; Westerbergh, A. Evidence for Magnesium–Phosphorus Synergism and Co-Limitation of Grain Yield in Wheat Agriculture. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 9012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossani, C.M.; Sadras, V.O. Chapter Six - Water–Nitrogen Colimitation in Grain Crops. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press, 2018; Vol. 150, pp. 231–274 ISBN 0065-2113.

- Sperfeld, E.; Martin-Creuzburg, D.; Wacker, A. Multiple Resource Limitation Theory Applied to Herbivorous Consumers: Liebig’s Minimum Rule vs. Interactive Co-Limitation. Ecol Lett 2012, 15, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-StPaul, N.; Delzon, S.; Cochard, H. Plant Resistance to Drought Depends on Timely Stomatal Closure. Ecol Lett 2017, 20, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemoine, D.; Jacquemin, S.; Granier, A. Beech (Fagus Sylvatica L.) Branches Show Acclimation of Xylem Anatomy and Hydraulic Properties to Increased Light after Thinning. 2002, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacke, U.; Sauter, J.J. Vulnerability of Xylem to Embolism in Relation to Leaf Water Potential and Stomatal Conductance in Fagus Sylvatica f. Purpurea and Populus Balsamifera. J Exp Bot 1995, 46, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Cano, F.J.; Gascó, A.; Cochard, H.; Nardini, A.; Mancha, J.A.; López, R.; Sánchez-Gómez, D. Variation in Photosynthetic Performance and Hydraulic Architecture across European Beech (Fagus Sylvatica L.) Populations Supports the Case for Local Adaptation to Water Stress. Tree Physiol 2015, 35, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likhachev, E. Dependence of Water Viscosity on Temperature and Pressure. Technical Physics 2003, 48, 514–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, T.T.; Pallardy, S.G. Vulnerability of Xylem to Embolism in Relation to Leaf Water Potential and Stomatal Conductance in Fagus Sylvatica f. Purpurea and Populus Balsamifera. Botanical Review 2002, 68, 270–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santakumari, M.; Berkowitz, G.A. Chloroplast Volume: Cell Water Potential Relationships and Acclimation of Photosynthesis to Leaf Water Deficits. Photosynth Res 1991, 28, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, I.M.; Sharp, R.E.; Boyer, J.S. Leaf Magnesium Alters Photosynthetic Response to Low Water Potentials in Sunflower 1. Plant Physiol 1987, 84, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuschner, C. Drought Response of European Beech (Fagus Sylvatica L.)—A Review. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst 2020, 47, 125576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson-Lazowski, A.; Cano, F.J.; Kim, M.; Benning, U.; Koller, F.; George-Jaeggli, B.; Cruickshank, A.; Mace, E.; Jordan, D.; Pernice, M.; et al. Multi-Omic Profiles of Sorghum Genotypes with Contrasting Heat Tolerance Connect Pathways Related to Thermotolerance. J Exp Bot 2024, erae506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Robson, T.M.; Cano, F.J.; Alté, L.; Sánchez-Gómez, D. Stomatal and Non-Stomatal Limitations on Leaf Carbon Assimilation in Beech (Fagus Sylvatica L.) Seedlings under Natural Conditions. For Syst 2012, 21, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Cano, F.; Valbuena, M.; Gil, L.; Aranda, I. Functional Performance of Oak Seedlings Naturally Regenerated across Microhabitats of Distinct Overstorey Canopy Closure. New For (Dordr) 2009, 39, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osonubi, O.; Davies, W.J. Root Growth and Water Relations of Oak and Birch Seedlings. Oecologia 1981, 51, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, T.; Pallardy, S. Acclimation and Adaptive Responses of Woody Plants to Environmental Stresses. The Botanical Review 2002, 68, 270–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Gil, L.; Pardos, J. Seasonal Water Relations of Three Broadleaved Species (Fagus Sylvatica L., Quercus Petraea (Mattuschka) Liebl. and Quercus Pyrenaica Willd.) in a Mixed Stand in the Centre of the Iberian Peninsula. For Ecol Manage 1996, 84, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, S.J.; Scholz, F.G.; Campanello, P.I.; Montti, L.; Jimenez-Castillo, M.; Rockwell, F.A.; Manna, L. La; Guerra, P.; Bernal, P.L.; Troncoso, O.; et al. Hydraulic Differences along the Water Transport System of South American Nothofagus Species: Do Leaves Protect the Stem Functionality? Tree Physiol 2012, 32, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Calcerrada Jesús and Sancho-Knapik, D. and M.-S.N.K. and L.J.-M. and M.N.G. and G.-P.E. Drought-Induced Oak Decline—Factors Involved, Physiological Dysfunctions, and Potential Attenuation by Forestry Practices. In Oaks Physiological Ecology. Exploring the Functional Diversity of Genus Quercus L.; Gil-Pelegrín Eustaquio and Peguero-Pina, J.J. and S.-K.D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 419–451 ISBN 978-3-319-69099-5.

- Munné-Bosch, S.; Alegre, L. Die and Let Live: Leaf Senescence Contributes to Plant Survival under Drought Stress. Functional Plant Biology 2004, 31, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WARREN, C.R.; ARANDA, I.; CANO, F.J. Responses to Water Stress of Gas Exchange and Metabolites in Eucalyptus and Acacia Spp. Plant Cell Environ 2011, 34, 1609–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Sánchez-Gómez, D.; Cadahía, E.; Fernández de Simón, B. Ecophysiological and Metabolic Response Patterns to Drought under Controlled Condition in Open-Pollinated Maternal Families from a Fagus Sylvatica L. Population. Environ Exp Bot 2018, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R.; Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Gil, L. Physiological and Morphological Response to Water Deficit in Seedlings of Five Provenances of Pinus Canariensis: Potential to Detect Variation in Drought-Tolerance. Trees 2009, 23, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limousin, J.-M.; Roussel, A.; Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Torres-Ruiz, J.M.; Moreno, M.; Garcia de Jalon, L.; Ourcival, J.-M.; Simioni, G.; Cochard, H.; Martin-StPaul, N. Drought Acclimation of Quercus Ilex Leaves Improves Tolerance to Moderate Drought but Not Resistance to Severe Water Stress. Plant Cell Environ 2022, 45, 1967–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanourakis, D.; Heuvelink, E.; Carvalho, S.M.P. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Physiological and Anatomical Components Involved in Higher Water Loss Rates after Leaf Development at High Humidity. J Plant Physiol 2013, 170, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grime, J.P.; Mackey, J.M.L. The Role of Plasticity in Resource Capture by Plants. Evol Ecol 2002, 16, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaland, T.R.; Wright, J.; Ratikainen, I.I. Individual Reversible Plasticity as a Genotype-level Bet-hedging Strategy. J Evol Biol 2021, 34, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.E.; Papaj, D.R. Why Study Plasticity in Multiple Traits? New Hypotheses for How Phenotypically Plastic Traits Interact during Development and Selection. Evolution (N Y) 2022, 76, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlichting, C.D.; Pigliucci, M. Phenotypic Evolution: A Reaction Norm Perspective; Sinauer Associates Incorporated: Sunderland, 1998; ISBN 9780878937998. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buskirk, J.; Steiner, U.K. The Fitness Costs of Developmental Canalization and Plasticity. J Evol Biol 2009, 22, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, T.; Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Sánchez-Gómez, D.; Aranda, I. Summer Drought Impedes Beech Seedling Performance More in a Sub-Mediterranean Forest Understory than in Small Gaps. Tree Physiol 2009, 29, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossiord, C.; Buckley, T.N.; Cernusak, L.A.; Novick, K.A.; Poulter, B.; Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Sperry, J.S.; McDowell, N.G. Plant Responses to Rising Vapor Pressure Deficit. New Phytologist 2020, 226, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Gil, L.; Pardos, J. Water Relations and Gas Exchange in Fagus Sylvatica L. and Quercus Petraea (Mattuschka) Liebl. In a Mixed Stand at Their Southern Limit of Distribution in Europe. Trees 2000, 14, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, E.; Cochard, H.; Deluigi, J.; Didion-Gency, M.; Martin-StPaul, N.; Morcillo, L.; Valladares, F.; Vilagrosa, A.; Grossiord, C. Interactions between Beech and Oak Seedlings Can Modify the Effects of Hotter Droughts and the Onset of Hydraulic Failure. New Phytologist 2024, 241, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, N.; Richardson, A. Stomatal Length Correlates with Elevation of Growth in Four Temperate Species†. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 2009, 28, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araus, J.L.; Febrero, A.; Vendrell, P. Epidermal Conductance in Different Parts of Durum Wheat Grown under Mediterranean Conditions: The Role of Epicuticular Waxes and Stomata. Plant Cell Environ 1991, 14, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaux, R.H. Variation in the Tissue Water Relations of Two Sympatric Hawaiian Dubautia Species and Their Natural Hybrid. Oecologia 1984, 65, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TYREE, M.T.; HAMMEL, H.T. The Measurement of the Turgor Pressure and the Water Relations of Plants by the Pressure-Bomb Technique. J Exp Bot 1972, 23, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, E.; Bousquet, F.; Ducrey, M. Use of Pressure Volume Curves in Water Relation Analysis on Woody Shoots: Influence of Rehydration and Comparison of Four European Oak Species. Ann. For. Sci. 1990, 47, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KUBISKE, M.E.; ABRAMS, M.D. Pressure-Volume Relationships in Non-Rehydrated Tissue at Various Water Deficits. Plant Cell Environ 1990, 13, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodribb, T.J.; Holbrook, N.M. Stomatal Protection against Hydraulic Failure: A Comparison of Coexisting Ferns and Angiosperms. New Phytologist 2004, 162, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salman, Y.; Cano, F.J.; Mace, E.; Jordan, D.; Groszmann, M.; Ghannoum, O. High Water Use Efficiency Due to Maintenance of Photosynthetic Capacity in Sorghum under Water Stress. J Exp Bot 2024, 75, 6778–6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R.; Nolf, M.; Duursma, R.A.; Badel, E.; Flavel, R.J.; Cochard, H.; Choat, B. Mitigating the Open Vessel Artefact in Centrifuge-Based Measurement of Embolism Resistance. Tree Physiol 2019, 39, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, T.M.; Sánchez-Gómez, D.; Cano, F.J.; Aranda, I. Variation in Functional Leaf Traits among Beech Provenances during a Spanish Summer Reflects the Differences in Their Origin. Tree Genet Genomes 2012, 8, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, A.; Klepsch, M.; Karimi, Z.; Jansen, S. How to Quantify Conduits in Wood? Front Plant Sci 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valladares, F.; Sánchez-Gómez, D.; Zavala, M.A. Quantitative Estimation of Phenotypic Plasticity: Bridging the Gap between the Evolutionary Concept and Its Ecological Applications. Journal of Ecology 2006, 94, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Tgrowth | Light | Water | Tgrowth x Light | Tgrowth x Water |

Light x Water |

Tgrowth x Light x Water |

| h | 6.70 * | 297.50 *** | 193.51 *** | 3.16 | 0.76 | 67.01 *** | <0.01 |

| d | 42.33 *** | 520.49 *** | 98.20 *** | 42.15 *** | 1.05 | 29.80 *** | 6.72 * |

| Leaves | 100.86 *** | 145.62 *** | 188.08 *** | 7.40 ** | 23.78 *** | 34.68 *** | 2.88 |

| TLA | 9.40 ** | 300.24 *** | 276.75 *** | 39.46 *** | 45.09 *** | 150.84 *** | 60.06 *** |

| LA | 14.39 *** | 89.00 *** | 74.64 *** | 12.26 ** | 0.89 | 26.41 *** | 1.16 |

| RB (abs) | 41.51 *** | 240.44 *** | 149.30 *** | 45.23 *** | 24.45 *** | 109.47 *** | 35.29 *** |

| SB (abs) | 19.35 *** | 145.18 *** | 74.65 *** | 15.00 *** | 5.46 * | 55.17 *** | 6.45 * |

| LB (abs) | 8.48 ** | 267.33 *** | 122.04 *** | 15.91 *** | 18.65 *** | 90.60 *** | 27.50 *** |

| RB (rel) | 0.30 | 0.71 | 9.25 ** | 4.69 * | 5.96 * | 0.02 | 5.29 * |

| SB (rel) | 15.35 *** | 4.59 * | 1.84 | 3.93 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 4.80 * |

| LB (rel) | 25.41*** | 1.53 | 2.84 | 1.08 | 4.37 * | <0.01 | 1.17 |

| An | 18.99 *** | 169.38 *** | 52.01 *** | 2.37 | 2.77 | 7.88 ** | 0.95 |

| Rl | 195.44 *** | 66.12 *** | 229.84 *** | 3.53 | 0.19 | 67.24 *** | 10.88 ** |

| gsw | 0.01 | 26.59 *** | 119.13 *** | 1.21 | 9.21 ** | 4.94 * | 0.70 |

| gmin | 652.60 *** | 700.90 *** | 1149.90 *** | 232.70 *** | 379.90 *** | 470.70 *** | 432.10 *** |

| E | 0.15 | 50.60 *** | 195.30 *** | 2.74 | 26.13 *** | 2.79 | 2.03 |

| iWUE | 1.02 | 108.38 *** | 390.07 *** | 77.93 *** | 17.56 *** | 18.80 *** | 84.06 *** |

| WUE | 7.26 * | 59.41 *** | 97.25 *** | 38.82 *** | 2.68 | 6.81 * | 44.05 *** |

| LMA | 264.22 *** | 505.64 *** | 166.07 *** | 22.42 *** | 111.74 *** | 7.13 ** | 118.75 *** |

| δ13C | 31.65 *** | 50.34 *** | 11.99 ** | 0.08 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.32 |

| SD | 0.59 | 10.49 ** | 0.29 | 4.55 * | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.82 |

| LS | <0.01 | 2.98 | 11.35 ** | 0.67 | 6.55 * | 0.33 | 0.22 |

| PCI | 1.00 | 27.23 *** | 6.87 * | 7.18 * | 11.39 ** | 0.03 | 2.03 |

| C_Π0 | 1.49 | 5.69 * | 21.60 *** | 1.00 | 5.47 * | 3.01 | 0.22 |

| C_ Π100 | 33.79 *** | 22.46 *** | 86.54 *** | 0.49 | 14.93 *** | 22.86 *** | 0.33 |

| Π0 | 5.02 * | 1.43 | 2.46 | 0.11 | 11.08 ** | 6.28 * | 1.67 |

| Π100 | 0.27 | 4.25 * | 16.44 *** | 1.40 | 16.27 *** | 4.50 * | 0.88 |

| εleaf | 0.28 | 0.04 | 9.40 ** | 0.11 | 7.08 * | 4.19 * | 0.66 |

| Ψleaf | 69.36 *** | 29.73 *** | 737.58 *** | 6.85 * | 0.01 | <0.01 | 4.305 * |

| Ψstem | 59.97 *** | 15.49 *** | 710.44 *** | 12.86 ** | 0.07 | 0.35 | 0.75 |

| Ψpd | 46.04 *** | 11.67 ** | 852.71 *** | 1.87 | 0.03 | 3.55 | 4.87 * |

| SMleaf | 13.28 *** | 3.69 | 107.36 *** | 0.41 | 5.42 * | 5.53 * | 29.57 *** |

| Ks | 0.14 | 32.26 *** | 28.46 *** | 0.38 | 0.81 | 0.01 | 0.93 |

| Kl | 90.41 *** | 0.40 | 221.90 *** | 0.85 | 74.61 *** | 27.33 *** | 54.54 *** |

| Hv | 76.66 *** | 15.01 *** | 99.57 *** | 1.45 | 55.79 *** | 1.05 | 6.37 * |

| kplant | 0.39 | 23.98 *** | 256.35 *** | 0.01 | 7.94 ** | 2.54 | 3.85 |

| VD | 48.24 *** | 447.68 *** | 2158.38 *** | 55.35 *** | 42.96 *** | 5.88 * | 87.85 *** |

| VA | 261.49 *** | 893.15 *** | 2680.29 *** | 90.51 *** | 90.14 *** | 111.22 *** | 148.31 *** |

| RP | 2.17 | 0.05 | 0.93 | 3.67 | 3.00 | 0.06 | <0.01 |

| Dh | 245.32 *** | 1165.82 *** | 3405.51 *** | 11.11 ** | 52.28 *** | 14.03 *** | 190.31 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).