1. Introduction

Transportation is a major contributor to global carbon emissions, with private vehicles—particularly internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs)—accounting for a substantial proportion of sectoral emissions. As vehicular decarbonization emerges as a critical strategy for climate change mitigation [

1,

2], electric vehicles (EVs) have gained global prominence over the past two decades due to their potential for reducing operational emissions [

3,

4]. However, while EVs produce no direct tailpipe emissions, their environmental benefits are contingent on the carbon intensity of electricity generation. In regions where fossil fuel-based thermal power plants dominate the energy mix, EVs merely shift emissions from the vehicle operation phase to the energy production stage [

5], sparking ongoing debates about their net carbon mitigation potential [

6,

7].

In general, vehicle life cycle emissions span production, usage, maintenance, and end-of-life phases, with the usage stage contributing 62%–70% of total emissions [

8]. Consequently, comparative analyses of EV and ICEV carbon footprints have predominantly focused on operational phases [

9,

10,

11]. However, such studies often assume uniform travel patterns and equivalent annual mileage between EV and ICEV users—an assumption challenged by recent empirical findings. For instance, Liu and Xu [

12] revealed that EV owners in China exhibit 1.5 times higher annual mileage than ICEV owners. This disparity raises a critical question: Under comparable vehicle lifespans (e.g., 100,000 km or 150,000 km), could higher annual mileage among EV owners negate their carbon advantage, particularly in regions reliant on fossil fuel-based electricity?

To address this gap, this study conducts a granular comparative analysis of annual carbon emissions between EV and ICEV owners, incorporating two novel dimensions: (1) Differential usage behaviors: systematic integration of mileage disparities and travel mode preferences (e.g., EV owners’ propensity for private vehicle reliance); (2) Multifaceted emission determinants: regional power grid carbon intensity, charging infrastructure efficiency, vehicle-specific energy consumption metrics (kWh/100km for EVs; L/100km for ICEVs), temperature effects, and vehicle classification. By bridging these overlooked factors, this paper provides policymakers with actionable insights to optimize EV adoption strategies and maximize environmental benefits.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews relevant literature;

Section 3 details the methodology;

Section 4 presents results;

Section 5 discusses implications; and Section 6 concludes with policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

The conceptual foundation of life cycle assessment (LCA) traces back to the late 1960s when the Midwest Research Institute (MRI) conducted a groundbreaking energy analysis for The Coca-Cola Company, systematically evaluating beverage containers from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal [

13]. This seminal work laid the groundwork for modern LCA methodologies, which gained prominence in environmental management during the 1990s following the establishment of ISO 14040 standards that formalized LCA frameworks [

14]. As a comprehensive analytical tool, LCA quantifies environmental impacts across a product’s entire life cycle, encompassing raw material acquisition, manufacturing, transportation, operational use, and ultimate disposal/recycling [

15]. Its capacity to provide quantifiable environmental metrics has established LCA as an indispensable methodology for comparative environmental impact studies.

In the automotive emissions research, LCA applications have evolved to address both direct exhaust emissions during vehicle operation and cumulative impacts across full life cycles [

6,

10,

11,

16]. Recent comparative studies utilizing LCA frameworks reveal divergent conclusions regarding the carbon efficiency of EVs versus ICEVs. A substantial body of research demonstrates EVs’ environmental advantages: Qiao et al. [

17] reported 18% lower life cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for EVs compared to ICEVs in 2015, projecting further reductions to 34.1 t CO2eq by 2020 through grid decarbonization. Similarly, Wu et al. [

8] identified a 13.4% GHG reduction potential for Chinese EVs by 2020 through electricity mix optimization. Zhang et al. [

18] concluded that most EVs exhibit emission reduction effects relative to ICEVs, estimating that in China, EVs achieved emission reductions of 6.56% to 44.4% in 2020, 13.97% to 53.39% in 2025, and 19.65% to 57.49% in 2030. These findings align with global observations that EV emissions strongly correlate with regional grid cleanliness [

19,

20,

21,

22].

Contrasting evidence, however, suggests contextual limitations to EV superiority. Hawkins et al. [

23], Petrauskienė et al. [

24] and Nuez et al. [

25] cautioned that fossil-dependent energy systems could negate EV benefits, exemplified by Li et al. [

26] finding of 24-31% higher emissions for Chinese EVs under 2018 grid conditions. Kurien and Srivastava [

5] found that fossil fuels account for 81.7% of India’s power generation energy mix; and in this scenario, except for two-wheel EVs, the indirect carbon emissions of most EVs surpass those of ICEVs. Moreover, regional case studies further illustrate this paradox: in Poland’s coal-intensive grid, daily EV operation (26 km) generates 2.49–3.28 kgCO

2/day, comparable to ICEV emissions [

27]. Furthermore, Zhang et al. [

18] found that the carbon emission reduction rate of EVs exhibits significant variation depending on driving mileage and vehicle type. In 2020, EVs with a driving mileage exceeding 700 kilometers demonstrated minimal to no emission reduction benefits, or in some cases, negative effects. Additionally, production-phase analyses also show higher GHG emissions for EVs due to battery manufacturing [

28,

29,

30,

31].

While existing research has extensively examined technical parameters (e.g., powertrain efficiency, grid emission factors) and vehicle characteristics (e.g., range, weight), critical behavioral dimensions remain understudied. Researchers generally assume that EVs and ICEVs have comparable service lifespans, typically estimated to be around 10 years or 150,000 km [

19,

32,

33,

34]. This indicates that EV owners exhibit similar daily vehicle usage patterns compared to ICEV owners. However, emerging evidence suggests significant differences in usage patterns between EV and ICEV owners [

12,

35,

36]. The operational cost advantages of EVs [

37], their environmentally-friendly nature [

4], and policy support [

38,

39] may incentivize greater utilization intensity, as demonstrated by Chinese EV owners driving 50% more annual kilometers than ICEV counterparts [

12]. This behavioral divergence results in the temporal compression of emissions during the life cycles of EVs, as intensive usage patterns condense total emissions into a shorter operational timeframe. This phenomenon is often overlooked in conventional LCA models, which typically assume uniform usage patterns.

However, this oversight carries substantial methodological implications. Given comparable vehicle lifespans (e.g., 150,000 km), intensified EV usage accelerates emission accumulation during the operational phase. For instance, an EV reaching its 150,000 km lifespan in 10 years versus an ICEV achieving the same over 15 years would exhibit distinct annual emission profiles, even with per-kilometer EV advantages. Such temporal dynamics challenge conventional annual emission comparisons and necessitate user-centric analytical frameworks. Therefore, this study addresses this critical gap by developing a usage-phase LCA model that explicitly incorporates behavioral differences between EV and ICEV owners. Building upon established parameters including grid carbon intensity, charging efficiency, energy consumption rates, and thermal effects, this study proposes a novel comparative framework from private vehicle owners’ perspectives. This approach enables more nuanced assessments of real-world emission tradeoffs between emerging and conventional vehicle technologies.

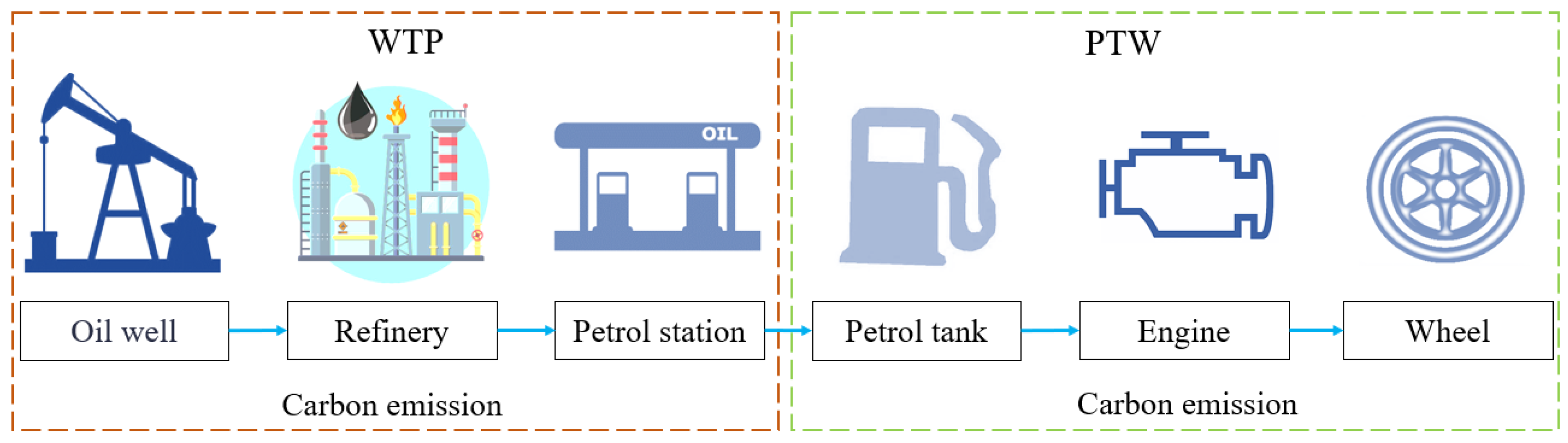

4. Case Study

Building on

Section 3’s framework—which quantifies interactions between grid carbon intensity (

CEG), vehicle efficiency, and usage pattern differences—we apply this model to real-world contexts via spatial stratification. China, the world’s largest EV market (15.52 million EVs by 2023) and a nation with significant interregional energy disparities, provides an ideal case study. Provincial

CEG varies widely—from 0.095 kgCO

2/kWh in hydropower-dominant regions to 1.092 kgCO

2/kWh in coal-reliant areas—offering natural experiments to investigate two questions: (1) how do spatial

CEG variations affect EV-ICEV carbon emission parity thresholds under different usage intensities? and (2) do observed behaviors (e.g., EV owners driving more mileage) erode emission advantages in specific energy regimes?

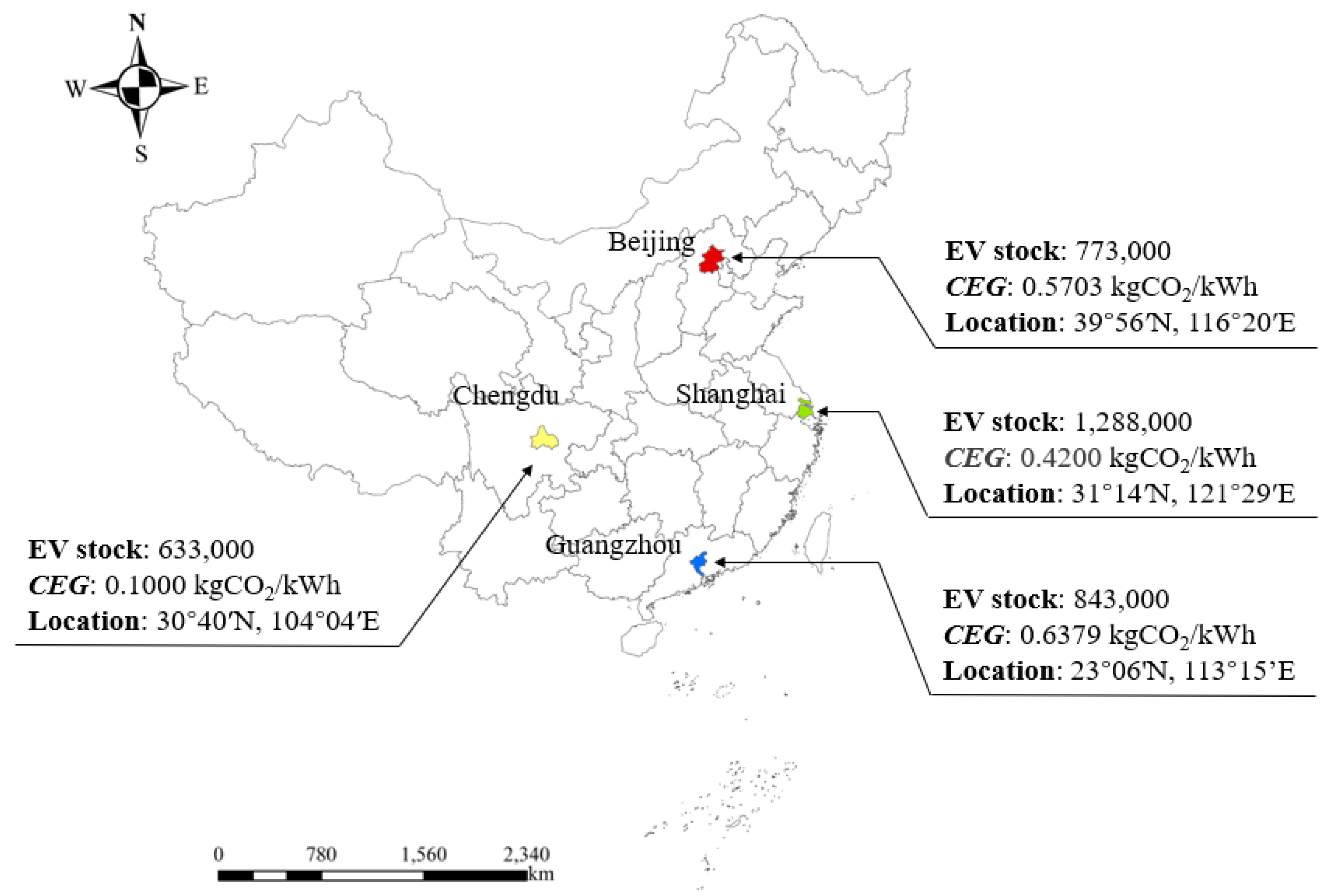

To analyze how regional energy profiles influence EVs’ emission reduction efficacy, we employ a spatially differentiated framework. Four megacities—Beijing (North China), Shanghai (East China), Guangzhou (South China), and Chengdu (Southwest China)—were selected (

Figure 7) to represent diverse grid types. By 2023, each city had over 500,000 EVs, with Shanghai leading at 1.288 million. Grid

CEG varied significantly in 2023: Chengdu (0.1000 kgCO

2/kWh, lowest) vs. Guangzhou (0.6379 kgCO

2/kWh, highest). This disparity underscores substantial regional differences in EVs’ indirect emissions compared to ICEVs.

Additionally, 100-kilometer energy consumption gap between EVs and ICEVs is a critical determinant of their emission disparities. To capture real-world patterns, we used web scraping to collect verified owner-reported data from major platforms (e.g., Dongchedi,

www.dongchedi.com; Autohome,

www.autohome.com.cn), yielding 19,057 valid records across four vehicle classes (A0, A, B, C) and two body types (sedans, SUVs): ICEVs (12,268 records), 6,192 sedans and 6,076 SUVs; EVs (6,789 records), 3,189 sedans and 3,600 SUVs. To account for regional variations in traffic, infrastructure, and driving behaviors, we analyzed energy consumption alongside city-specific grid emission factors.

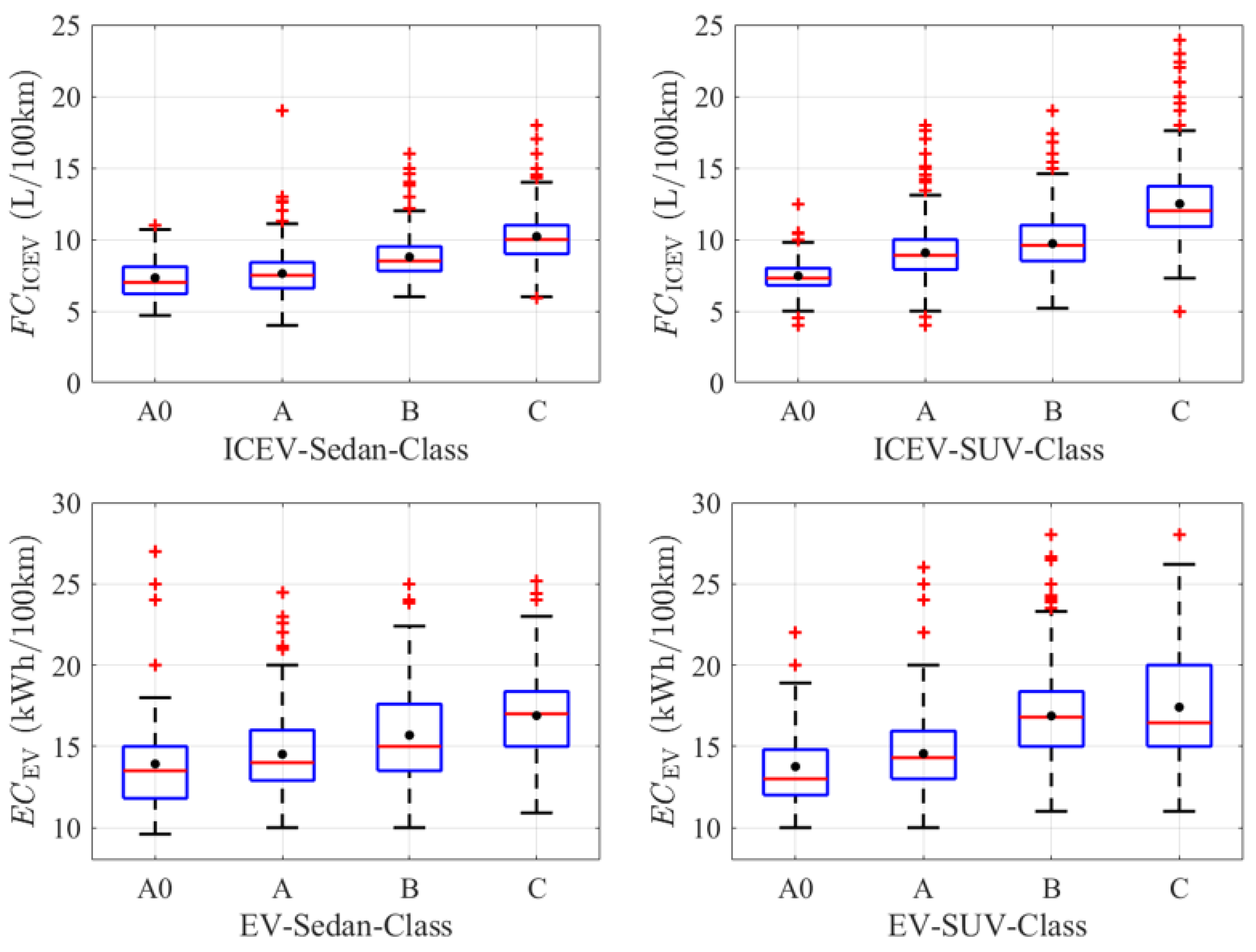

Figure 8 shows separate boxplots for EV and ICEV energy consumption in Beijing, with median (red lines), mean (black dots), and outliers (+). After removing outliers, we calculated descriptive statistics (median, quartiles, max, min, mean) to characterize energy consumption patterns. By integrating these with grid

CEG and annual mileage, we quantify annual carbon emission disparities between EV and ICEV owners.

Moreover, in the case study, for the efficiency factors

ηcharge (charging losses) and

ηtrans (transmission losses), based on statistical data provided by the National Energy Administration, we set

ηtrans to 6.5%, and

ηcharge to 10% [

54]. In addition, assuming that the average annual mileage of ICEV owners is 10,000 km, a value grounded in a synthesis of statistical datasets and real-world vehicle usage scenarios [

19,

33]. Based on these settings, this study uses a combined visualization approach overlaying violin plots and boxplots to display the distribution and heterogeneity of carbon emissions from EVs and ICEVs across four regional grid carbon intensities (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Chengdu), four vehicle categories (A0 to C-class sedans/SUVs), and mileage multipliers relative to the ICEV baseline (

x = 1, 1.5, 2). The corresponding results are presented in

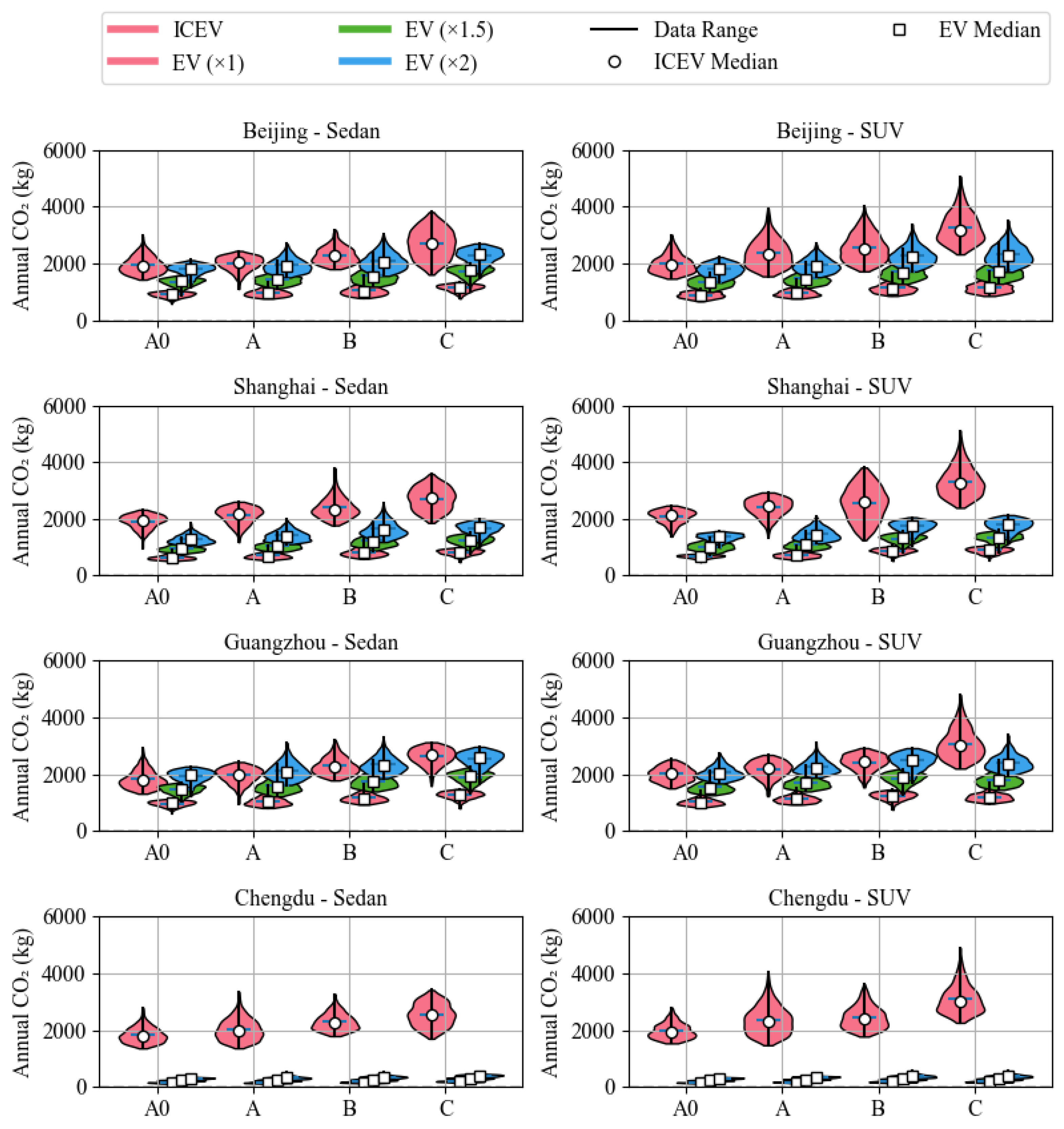

Figure 9.

As shown in

Figure 9, grid carbon intensity is pivotal in shaping EV emission distributions. In high-carbon regions (e.g., Guangzhou), high-energy-consuming EVs at the maximum percentile emit more than medium/low-energy ICEVs (≤75th percentile) but less than high-energy ICEVs (maximum percentile). In contrast, low-carbon regions (e.g., Chengdu) use grid decarbonization to offset extreme EV usage (maximum percentile), ensuring all percentile ranges retain EVs’ absolute emission advantage. Second, regional heterogeneity emerges in the impact of annual mileage multipliers (x). In high-carbon regions (e.g., Guangzhou), higher x drives nonlinear dispersion growth in EV emissions—e.g., C-class SUVs see a 62.5% IQR increase—especially among extreme high-energy users (maximum percentile). Low-carbon regions (e.g., Chengdu) show modest dispersion growth (IQR increase < 35%), as grid decarbonization mitigates high-mileage emission penalties.

Lastly, energy consumption quantiles reveal technological optimization priorities. High-energy models (e.g., C-class SUVs) exhibit right-skewed EV emission distributions (long tails). In Guangzhou, x = 2 drives maximum EV emissions (5.32 tCO2/year) above ICEVs’ 75th percentile (4.80 tCO2/year), meaning 25% of high-energy EV owners exceed medium/low-energy ICEVs (Q1–Q3). Intelligent energy management is thus critical to mitigate extreme-scenario risks. Additionally, low-energy models (e.g., A0-class) show IQR values 35%–45% of same-level ICEVs with no significant skewness. For example, Beijing’s A0-class EVs (x = 1.5) have a 25th–75th percentile range of 1.2–1.7 tCO2/year, confirming robust emission advantages across driving behaviors.

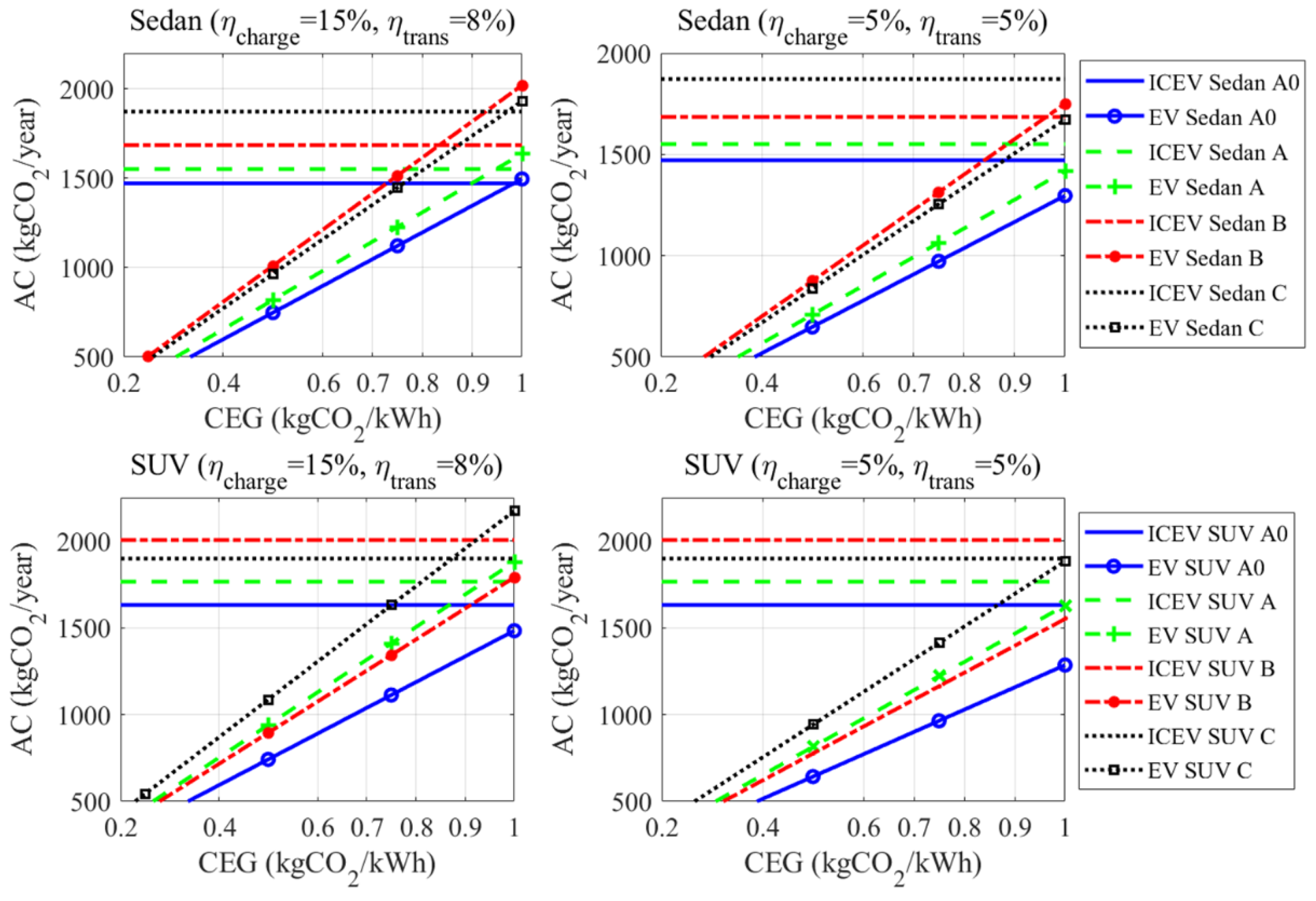

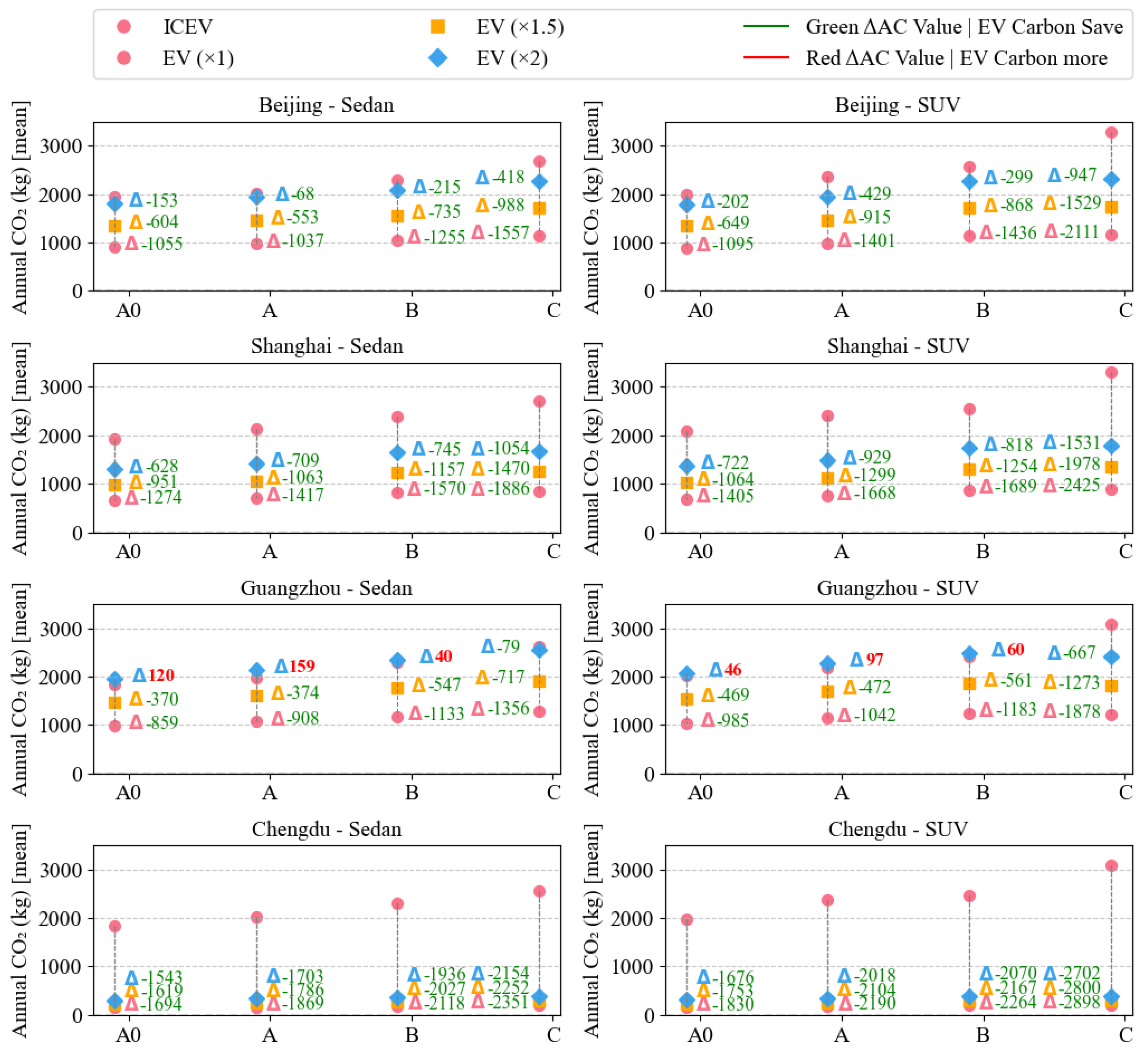

The above analysis reveals heterogeneity in carbon emission distributions between EVs and ICEVs across cities, vehicle classes, and mileage multiplier (

x) scenarios. However, real-world distributions are shaped by intertwined user behaviors and regional grid characteristics, necessitating standardized models to identify universal patterns among core variables. Therefore, using average energy consumption data by vehicle class, the study constructs a lollipop chart (

Figure 10) to quantify direct effects of grid carbon intensity (

CEG) and mileage multiplier (

x) on carbon emission differences (Δ

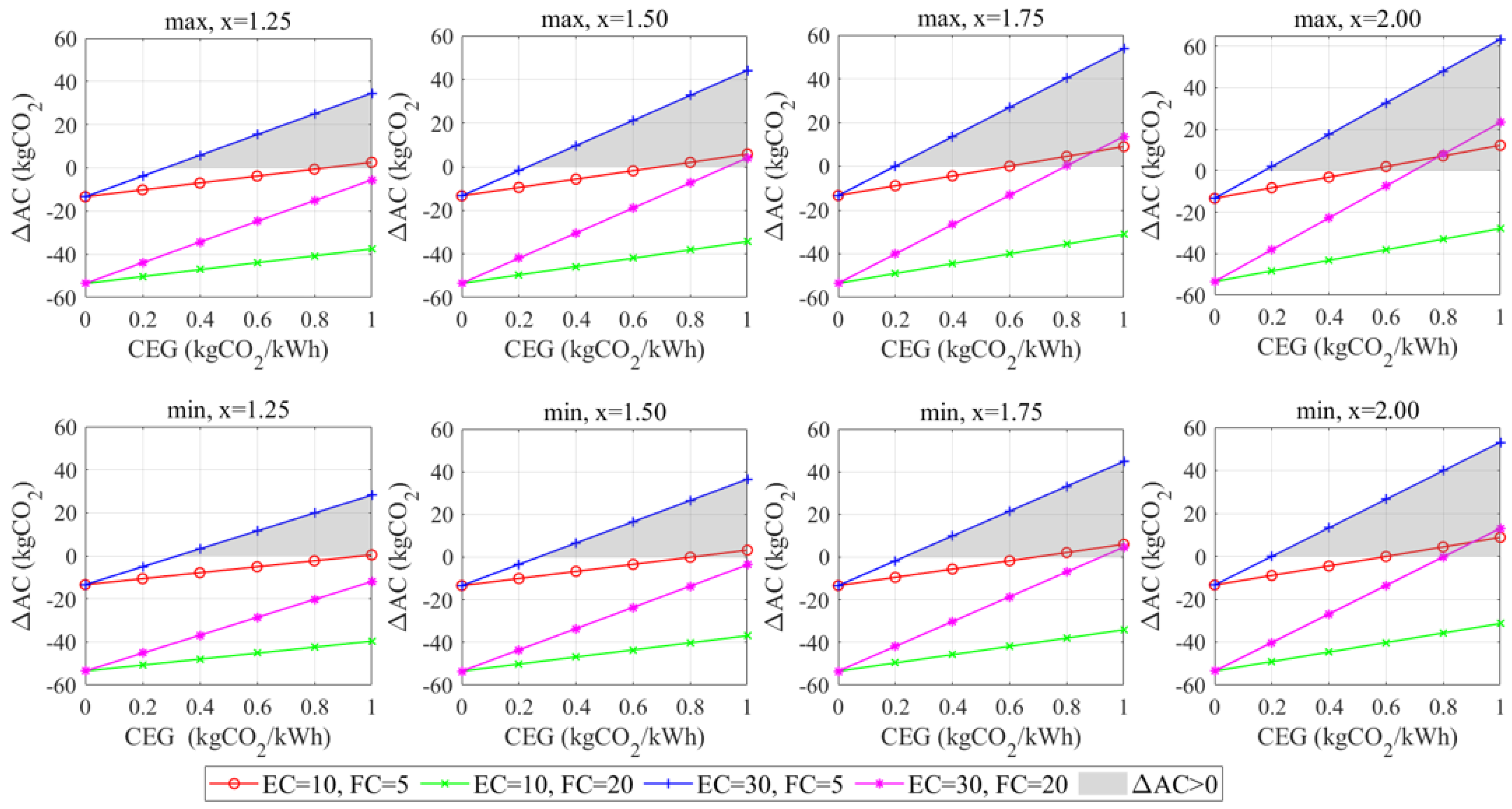

AC) between identical EV and ICEV classes. This method minimizes outlier impacts and isolates CEG-x interactions, establishing robust theoretical bounds for policy design.

Figure 10 shows that in high-carbon regions (e.g., Guangzhou,

CEG = 0.6379 kgCO

2/kWh), higher x values (e.g.,

x = 2, double the baseline mileage) drive Δ

AC toward zero or positivity—notably for A0-, A-, and B-class models—indicating EV emissions may exceed comparable ICEVs. Conversely, in low-carbon regions (e.g., Chengdu,

CEG = 0.1000 kgCO

2/kWh), all same-class Δ

AC values remain negative, confirming EVs emit significantly less than ICEVs—even at doubled mileage. Thus, the

CEG-

x interaction is pivotal in determining the degree of EVs’ emission advantage.

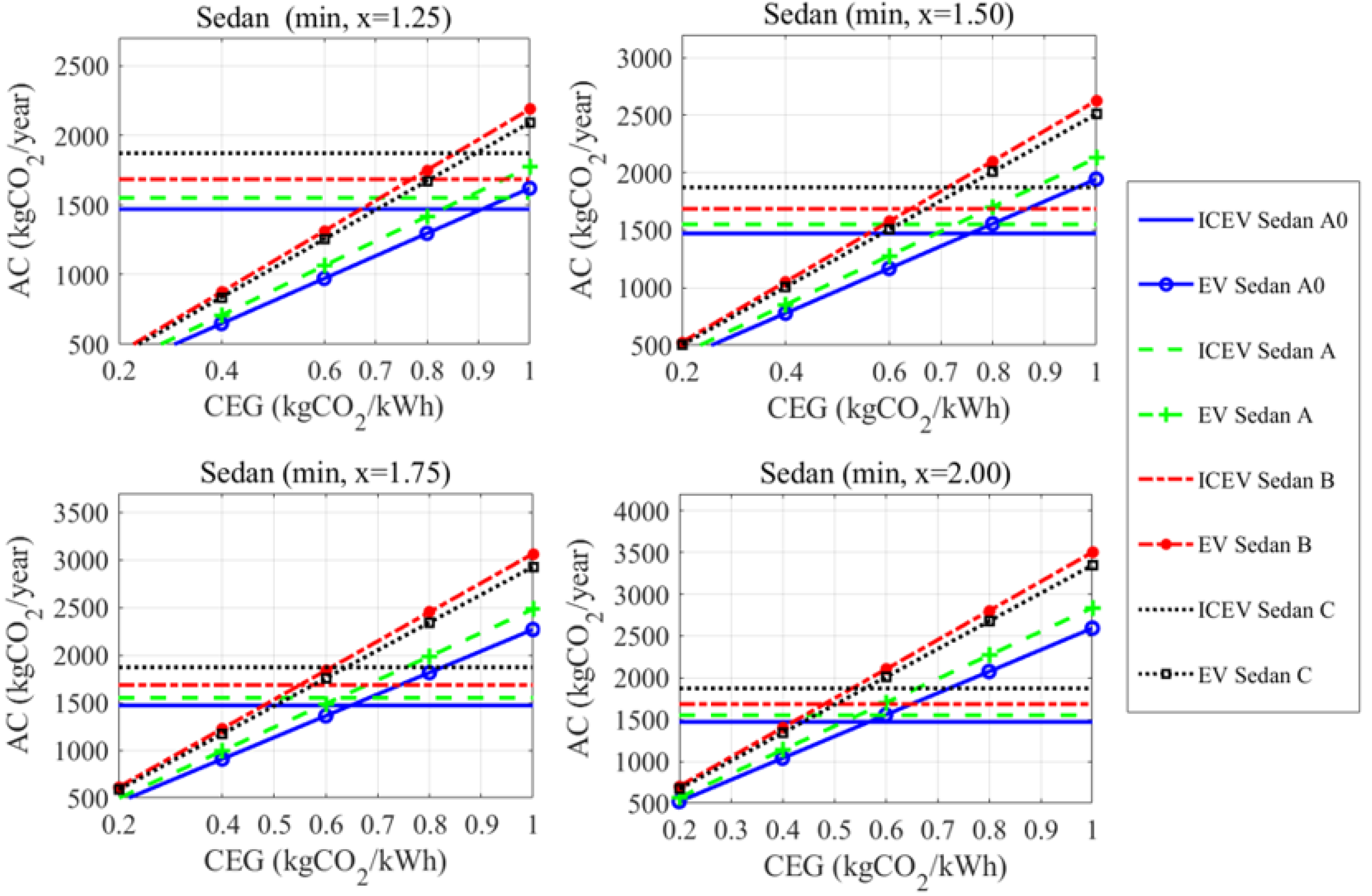

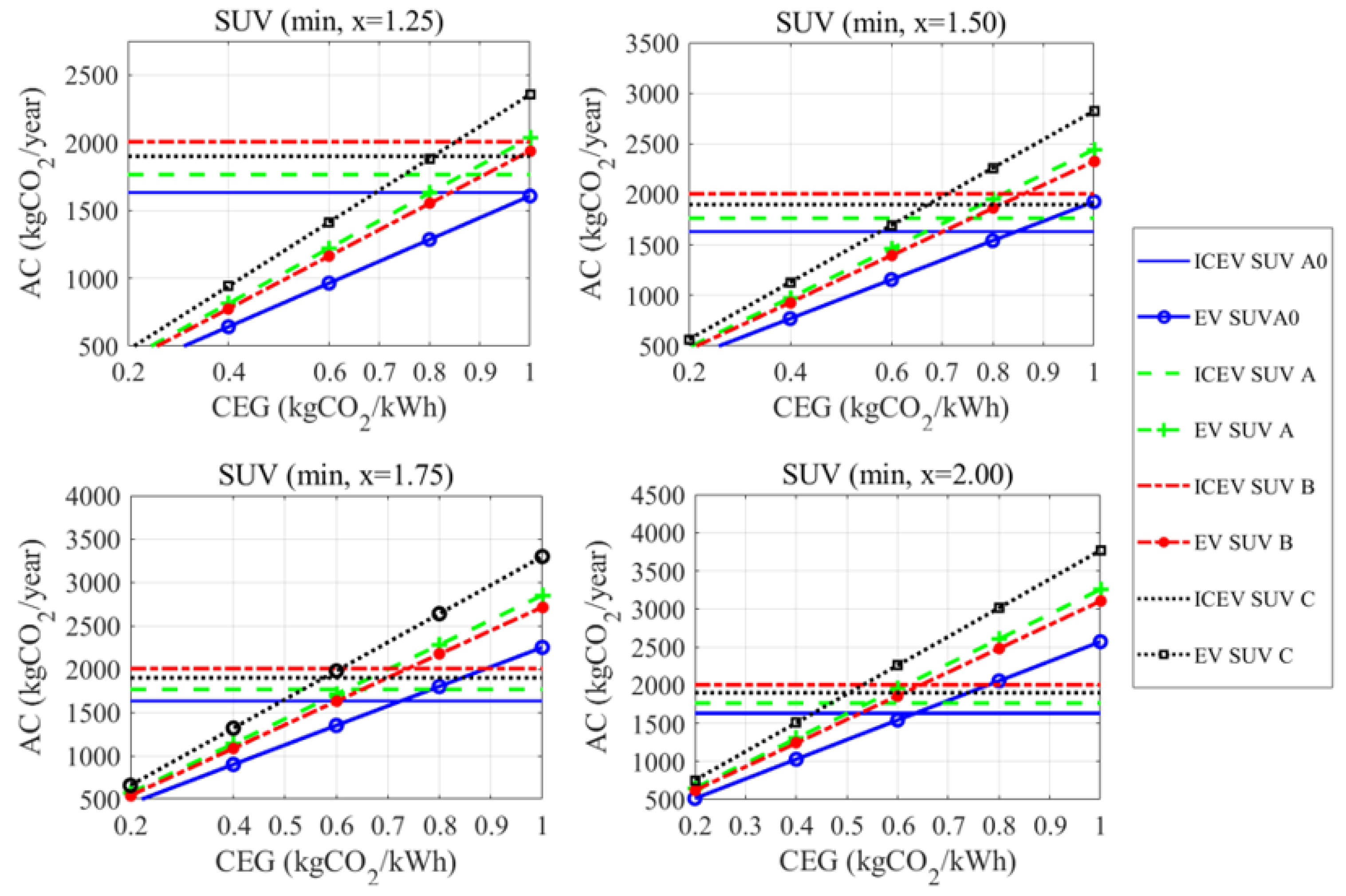

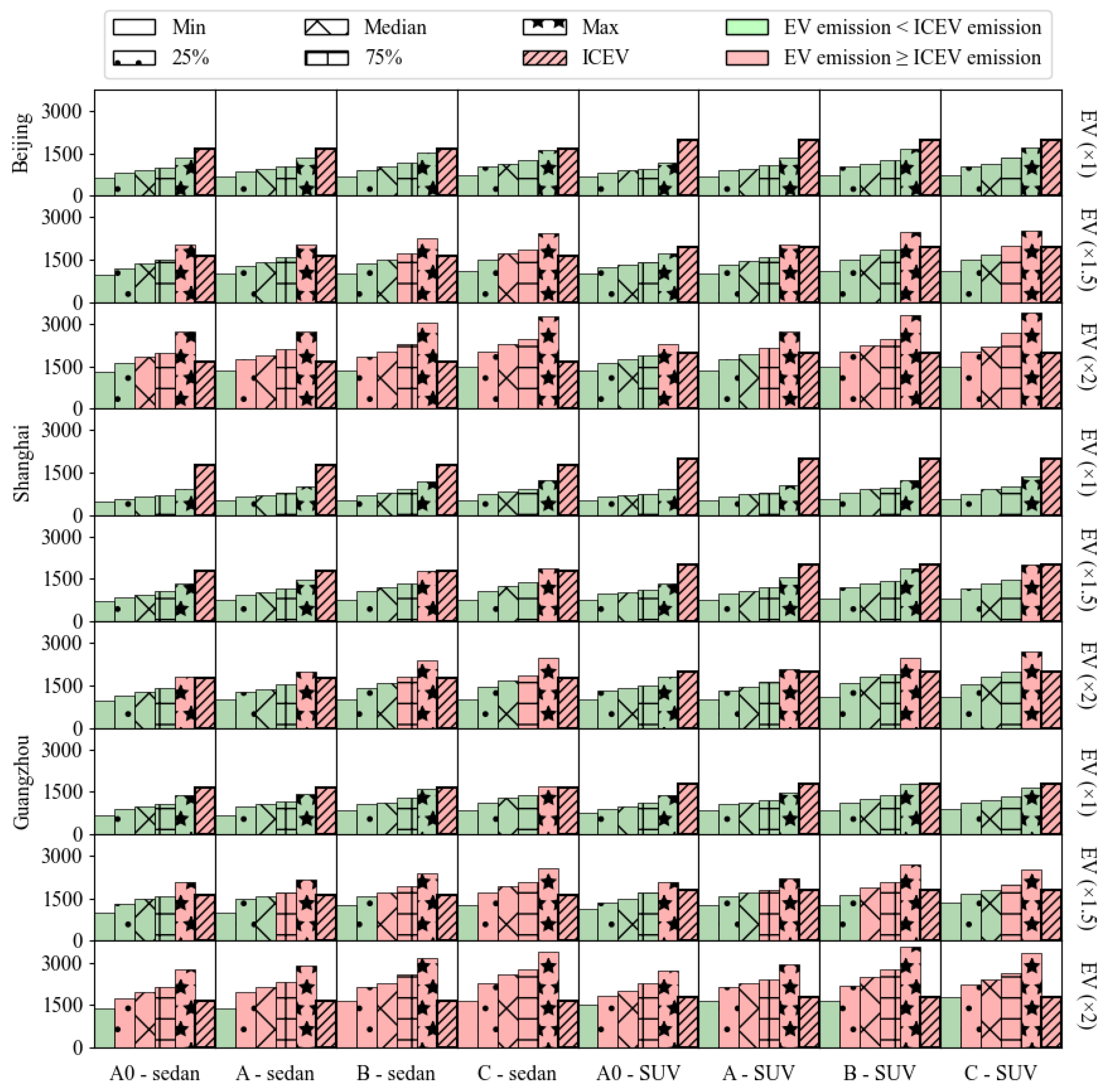

While

Figure 10 explores same-class policy-sensitive ranges for grid carbon intensity (

CEG) and mileage multiplier (

x), real-world consumer choices often involve cross-class comparisons (e.g., B-class EVs vs. A-class ICEVs). To address this, we extend the analysis framework by benchmarking against A-class ICEVs’ median fuel consumption—which accounts for ~50% of China’s passenger car sales—and evaluating EV emission quantiles (minimum, 25th, median, 75th, maximum) from real-world data. This quantifies extreme user behavior impacts on emission reduction potential (

Figure 11). Notably, Chengdu is excluded from cross-class analysis because its ultra-low grid

CEG (0.1 kgCO

2/kWh) ensures all EV quantiles—including the maximum—lie below ICEVs’ 25th percentile (

Figure 9), leaving no policy optimization space. Thus, we focus on medium/high-carbon grids (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou) to analyze

CEG-energy consumption interactions.

Figure 11 shows EVs’ emission advantage depends on vehicle energy consumption and grid

CEG. A0-class EVs—powered by low energy consumption—remain below A-class ICEVs’ median emissions even under high-carbon grids (e.g., Guangzhou) and doubled mileage (

x = 2, 20,000 km). In addition, B- and C-class EVs, however, are highly sensitive to both factors: C-class SUVs at Guangzhou’s max percentile with

x = 2 emit 1.3 times A-class ICEVs’ median, exceeding the benchmark. Finally, low-energy EVs (minimum–25th percentile) outperform ICEVs universally, but high-energy EVs (75th–max percentile) approach or surpass ICEV benchmarks in medium/high-carbon grids.

Now, building on the above analysis, this study focuses on four critical dimensions: power grid decarbonization, class-based vehicle control, user behavior guidance, and cross-regional collaboration. A targeted policy framework is proposed to systematically optimize the carbon emission reduction potential of electric vehicles.

First, regional grid decarbonization is critical to unlocking EVs’ emission reduction potential. As shown in

Figure 9, Chengdu (characterized by a low-carbon grid with a carbon emission intensity (

CEG) of 0.1 kgCO

2/kWh) demonstrates an absolute advantage for EVs: even when annual mileage doubles (

x = 2, relative to a 10,000 km baseline), EVs’ lifetime emissions remain significantly lower than those of ICEVs. In contrast, Guangzhou (a high-carbon grid with

CEG = 0.6379 kgCO

2/kWh) shows that high-energy-consuming EVs may exceed ICEV emissions. Thus, coal-dependent regions must prioritize grid decarbonization—via wind, solar, and energy storage integration—to reduce CEG and realize EVs’ potential. Policies should include implementing a renewable energy quota system, expanding carbon market coverage, and accelerating flexible thermal power plant upgrades.

Second, differentiated vehicle promotion strategies are necessary. As shown in

Figure 11, A0-class EVs (e.g., 11.6 kWh/100km energy consumption) outperform A-class ICEVs even in high-carbon grids. By contrast, B- and C-class EVs in high-energy-consumption scenarios—even at doubled annual mileage (

x = 2)—may emit more carbon than A-class ICEVs. Therefore, high-carbon regions (e.g., Guangzhou) should prioritize subsidies for A0/A-class EVs and restrict high-energy models (e.g., C-class SUVs). In low-carbon regions (e.g., Chengdu), all EV classes can be promoted universally. Additionally, strengthening energy efficiency labeling will guide consumers toward low-energy models.

Third, dynamic monitoring of owner behavior can refine mileage incentive mechanisms.

Figure 10 shows that in high-carbon grids, doubling annual mileage (

x = 2) narrows and even reverses the carbon emission gap (Δ

AC) between EVs and ICEVs—e.g., A0, A, and B-class vehicles in Guangzhou switch to net higher emissions. To address this, policymakers should launch a driving data platform and design dynamic carbon credit policies for high-mileage users. Specifically: (1) high-mileage owners (>20,000 km/year) choosing high-energy models should face carbon taxes; (2) those selecting low-energy models should receive charging subsidies to incentivize efficiency.

Fourth, cross-regional collaboration and differentiated policies are essential.

Figure 9 reveals city-specific variations in vehicle-related emissions: Guangzhou realizes EV benefits only via specific models, while Chengdu—with inherently low grid carbon intensity—requires no additional policies. A national policy framework should therefore adopt regionally tailored measures based on grid carbon intensity (low/medium/high): (1) high-carbon regions should mandate manufacturers to sell ≥60% low-energy models (e.g., A0 and A-class); (2) low-carbon regions can relax restrictions on higher-energy models; (3) cross-regional green electricity trading should be expanded to allow high-carbon regions to purchase western hydropower/wind quotas and reduce

CEG.

Overall, the carbon emission reduction benefits of EVs are significantly contingent upon the collaborative optimization of the power grid’s cleanliness, the energy efficiency of vehicle models, and user behavior patterns. Policy-making must steer clear of a “one-size-fits-all” approach. By fostering the low-carbon transition of the power grid, enforcing classification-based management of vehicle models, guiding adjustments in user behaviors, and enhancing regional collaboration and cooperation, the full potential of EVs’ carbon emission reduction benefits can be realized.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary

This study investigates the annual carbon emission disparities between EVs and ICEVs, with a focus on the interplay between owners’ vehicle usage patterns (e.g., annual mileage) and regional grid carbon intensity. By developing a usage-phase life cycle assessment (LCA) model, this study systematically quantifies the impacts of key variables—energy consumption metrics (ECEV and FCICEV), grid carbon intensity (CEG), and mileage patterns—on the carbon parity thresholds between EVs and ICEVs. Through scenario analyses and case studies across four Chinese megacities (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Chengdu), three critical findings emerge:

(1) Grid carbon intensity dominance: EVs exhibit significant carbon reduction advantages in low-CEG regions, even with doubled annual mileage. Conversely, in high-CEG regions, high-energy-consuming EVs may surpass ICEV emissions under extreme usage scenarios.

(2) Behavioral impact: EV owners’ higher annual mileage (1.5–2×ICEV baselines) accelerates emission accumulation, particularly in coal-dependent grids, potentially negating per-kilometer carbon advantages.

(3) Vehicle class heterogeneity: Small, low-energy EVs (e.g., A0-class sedans) consistently outperform ICEVs across all CEG ranges, while high-energy models (e.g., C-class SUVs) risk carbon parity reversal in high-CEG regions.

5.2. The Policy Implications of the Findings

The findings in this study highlight the need for spatially and technologically differentiated policies to maximize EV carbon reduction benefits:

(1) Grid decarbonization prioritization. Specifically, in high-CEG regions (e.g., coal-dependent areas), accelerate the integration of renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and storage technologies, while systematically phasing out coal-fired power plants. Implement carbon pricing mechanisms to incentivize the transition to cleaner energy systems. Conversely, in low-CEG regions, prioritize the widespread adoption of EVs across all vehicle categories while maintaining the momentum of ongoing grid decarbonization efforts.

(2) Vehicle class-specific promotion. Specifically, in high-CEG regions, establish mandatory quotas for low-energy vehicle models (e.g., at least 60% A0/A-class EVs) while imposing stricter restrictions on high-energy-consuming models (e.g., C-class SUVs). Furthermore, enhance energy efficiency labeling systems and provide targeted subsidies for low-consumption electric vehicles to effectively guide consumer preferences.

(3) Dynamic behavioral incentives. Establish real-time driving data platforms to monitor high-mileage users. Introduce carbon taxes for high-energy EV owners (>20,000 km/year) and charging subsidies for low-energy adopters.

(4) Cross-regional collaboration. Enable green electricity trading between high- and low-carbon regions to reduce CEG disparities. Develop national EV policies with regional adaptability, such as tiered subsidies based on local grid profiles.

5.3. Conclusions and Further Research

This study demonstrates that EVs’ carbon reduction potential is contextually contingent, requiring synergistic optimization of grid cleanliness, vehicle efficiency, and user behavior. While EVs generally outperform ICEVs in low-carbon grids, their advantages diminish or reverse in fossil-heavy regions, especially for high-energy models under intensive usage. Policymakers must adopt a no “one-size-fits-all” approach, balancing technological promotion with grid transformation and behavioral guidance.

Future research on carbon emission reduction in EVs can be further deepened in the following directions to refine the theoretical framework and strengthen policy guidance. First, full Lifecycle Integration: Expand LCA boundaries to include upstream emissions (battery production, raw material extraction) and end-of-life recycling, particularly for next-generation battery technologies (e.g., solid-state, sodium-ion). Second, behavioral economics analysis: Investigate drivers of EV owners’ high-mileage behavior (e.g., cost sensitivity, policy incentives) through mixed-method studies (surveys, experiments) to refine incentive designs. Third, global comparative analysis: Compare EV-carbon parity thresholds across diverse energy regimes (e.g., Norway’s renewables vs. India’s coal reliance) to derive universally adaptable policy frameworks. By addressing these dimensions, future work can enhance the precision of EV carbon assessments and support global efforts toward sustainable transportation transitions.