Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Developing nations like Bangladesh have yet to adopt hybrid electrical vehicles (EVs) for goods carrying causes, whereas environmental pollution and fuel costs are hitting hard. The electrically powered cars and trucks market promises an excellent opportunity for environmentally friendly transportation. However, these countries' inadequate infrastructure, substantial initial expenses, and insufficient policies impeding widespread acceptance hold market growth back. This paper examines the current status of the electric car market in developing nations, focusing on the infrastructure and regulatory framework-related barriers and the growth-promoting aspects. To promote an expanding hybrid and EV ecosystem, this article outlines recent studies and identifies critical regions where support for policy and infrastructural developments are needed. It discusses how developing nations may adapt successful international practices to suit their specific needs. At the same time, the research adopted system dynamics and case study methods to assess a transportation fleet and find the feasibility of adopting EVs. Several instances are improving infrastructures for recharging, providing incentives for lowering the adoption process cost and creating appropriate regulatory structures that promote corporate and consumer involvement. Findings highlight how crucial it is for governments, businesses, customers, and international bodies to collaborate with each other to build an affordable and sustainable EV network. The investigation concludes with recommendations for more research and appropriate regulations that may accelerate the adoption of EVs, reduce their adverse impacts on the environment, and promote economic growth.

Keywords:

Introduction

- I.

- Policy and Regulatory Barriers [12]: Developing countries often lack consistent countrywide innovative strategies to promote any transformation like EVs, resulting in disjointed policies and weak incentives. Developing nations always respond to any transformations due to a lack of scientific knowledge practices and are afraid of federal interventions for subsidies. Any developing Governments commonly fail to support adequate subsidies, tax rebates, and breaks, or any other types of financial motivations to inspire EV consumption and infrastructure change. This policy and regulatory vacuum demoralize private entrepreneurs from stepping forward to invest and adopt new processes for transformed products like EVs.

- II.

- Inadequate infrastructure [13,14]: The second barrier is establishing a new structure for charging stations and making it accessible to urban and rural areas. Most developing nations face unstable electricity supplies, too, making things challenging for highly electricity-reliable vehicles. Such infrastructural inefficiency decreases potential consumer confidence and confines the feasibility of EV usage, mainly in rural and semi-urban areas.

- III.

- Economic Challenges [14,15]: EVs need high upfront costs, which are unaffordable for middle-class people in developing nations. The current practice is to produce fossil fuel vehicles through local manufacturing and assembly industries depending on imported vehicles. They used to get dual financial support from car manufacturers, dealers, and financial institutions to handle overly price-sensitive markets. Additionally, the limited availability of such reasonable financing options restricts EV selling toward higher and moderate-income groups, excluding the mass population living under the poverty line.

- IV.

- Environmental Concerns [14,15,16]: Developing countries' worrying reliance on fossil-fuel-based electricity undermines innovative electric vehicles' environmental paybacks. Such standard practices create skepticism about EVs' overall impact. Without a transition to cleaner energy sources, EV adoption may not achieve its intended sustainability goals.

- V.

- Limited Buyer Awareness and Trust [13,17]: Before a customer makes a buying decision, they have to have enough understanding of the product features. People in developing countries lack understanding and education on EV features, benefits, maintenance knowledge, finance requirements, and long-term savings calculations. Such awareness creates hesitancy in adopting EVs. Many misconceptions about EV reliability, weather sensitivity, battery lifespan, and upfront costs further diminish consumer trust.

- VI.

- Technological Gaps and Supply Chain Constraints [18,19]: Developing countries rely heavily on importing technologies rather than innovating them in their own countries. Such limitations create challenges in accessing unconventional EV technologies due to supply chain limitations and the high import cost of essential vehicle components. For instance, the Bangladesh government imposes 600-800 percent taxes for luxury vehicles, which restricts the affordability of high-quality EVs in local markets.

- VII.

- Urban-Rural Disparities [20]: In developing countries, most facilities are concentrated in major cities, and the rest struggle to have minimal facilities like roads and highways, high-end product accessibility, maintenance and repair facilities, and charging infrastructure. Moreover, EV-related customer services are often located in urban areas, leaving rural areas underserved. This discrepancy limits the spread of EV adoption to regions with improved infrastructure and financial resources.

- I.

- To examine EV adoption trends, challenges, and policy barriers in developing nations, highlighting market potential and identifying region-specific obstacles to widespread adoption. Analyzing barriers such as infrastructure limitations, high costs, and policy gaps alongside the potential of emerging EV markets driven by urbanization, environmental awareness, and a growing middle class.

- II.

- Build a System Dynamics simulation model on a transportation fleet case to examine costs, carbon emissions, revenues, fuel consumption, and maintenance expenses. Then, analyze and compare the current transportation scenario with hybrid and electric vehicle (EV) adoption to assess the operational, economic, and environmental impacts of adopting sustainable transportation solutions in fleet operations. It provides a possible scenario to identify key barriers and opportunities for sustainable fleet transitions.

- III.

- To propose actionable recommendations and policy strategies for overcoming barriers and tailoring global EV adoption practices to developing nations' socio-economic and infrastructural contexts.

Literature Review

Research Methodology

- I.

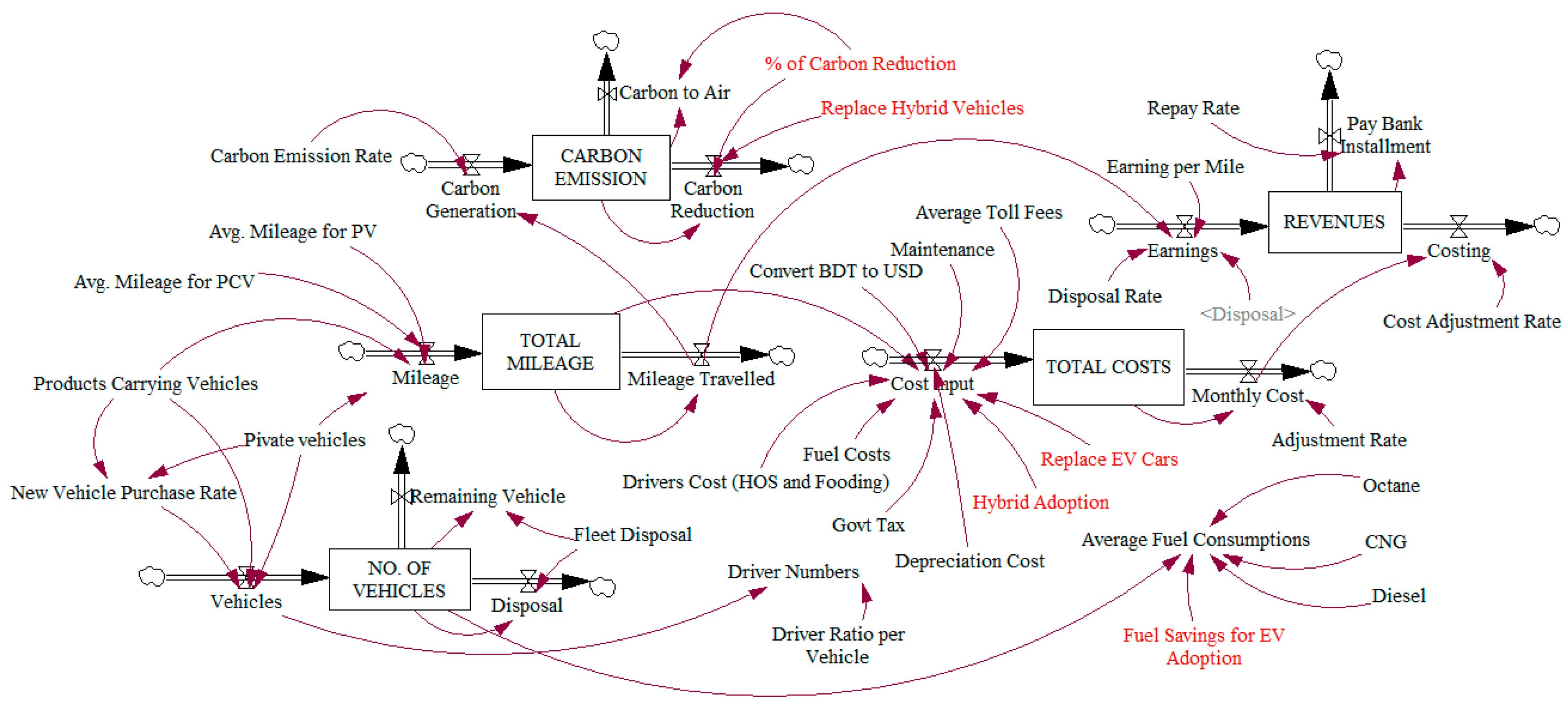

- System Dynamics (SD) Approach: The paper deployed the SD simulation model and simulated the interconnected variables to observe transitioning to Hybrids and EVs and find possible changes in operational costs, carbon emissions, and efficiency.

- II.

- Case Study Approach: A case Bangladeshi livestock farm considers drawing a simulation model and replicating its current processes. Later, hypothetical values are considered input to understand future transformations in light of key indicators. The case industry is one of the largest farms in terms of producing and transporting day-old chicks, milk, and livestock feed production and marketing of their products all over Bangladesh. Bangladesh is a small country of approximately 95,000 square miles, and the case farm's vehicle moves more than 5,50,000 miles per month.

- I.

- Fleet Composition: The type and number of vehicles. The model simplified the categories into Private Vehicles and Product-Carrying Vehicles.

- II.

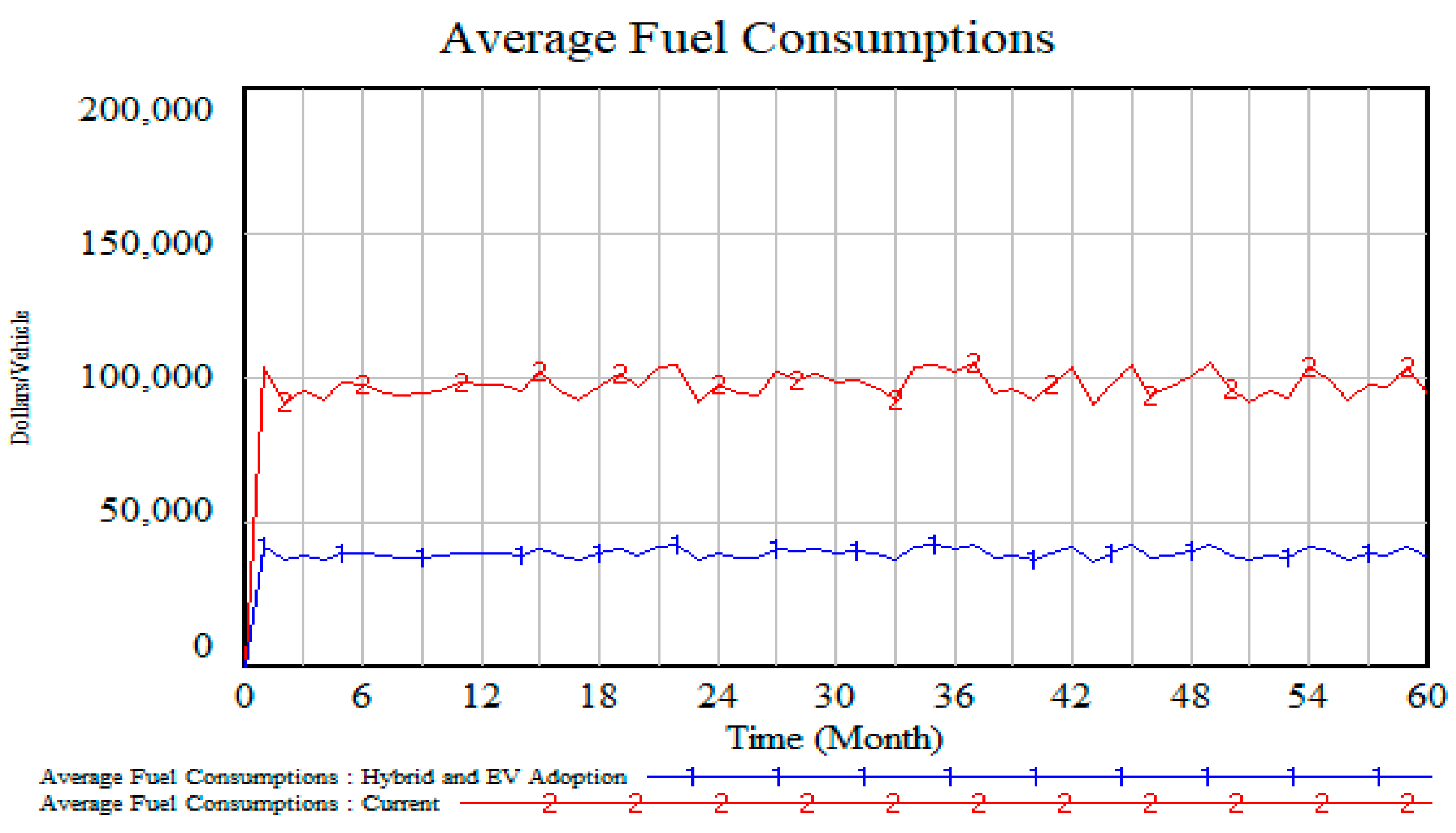

- Fuel Consumption: Differentiating between Diesel, Octane, and CNG fuel sources.

- III.

- Fuel Costs: The total fuel costs combined make an average per-mile cost.

- IV.

- Operational Metrics: Operational metrics rely on vehicle mileage (Bangladesh measures in kilometers but converted to miles for modeling purposes), maintenance costs (repairs, spare parts), fuel costs, and consumption efficiency.

- V.

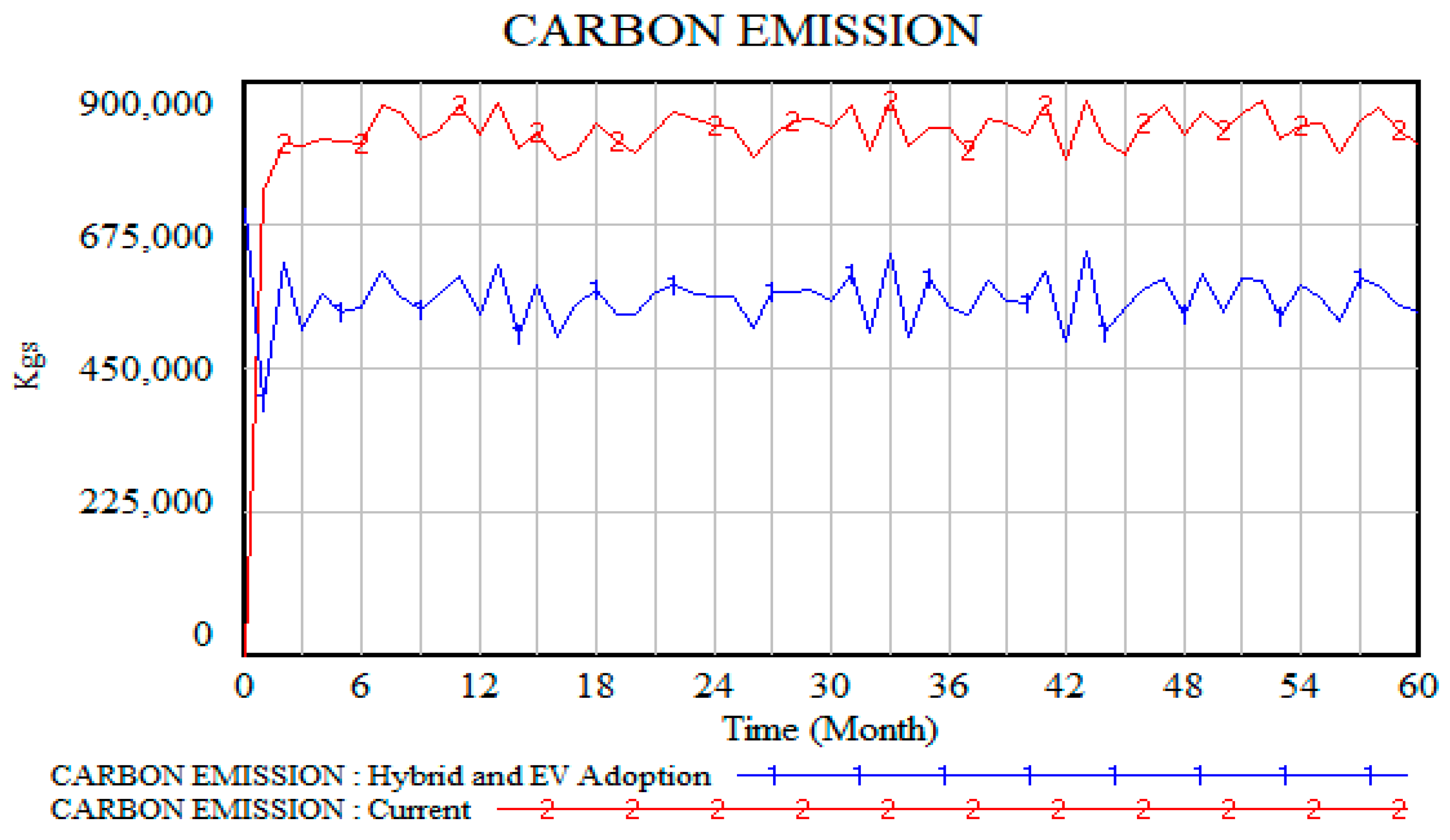

- Carbon Emissions: Most vehicles use diesel, and only 20 percent use Octane and CNG. The study estimates carbon emissions based on average mileage and fuel consumption. The average is nearly 1.46 Kg of carbon emissions while driving one mile by a 5-ton semi-truck.

Simulation Model on a Case Industry Transportation Fleet

- Represents the total fleet size, which impacts overall transportation operations.

- Directly connected to Fleet Disposal (removal of older vehicles) and New Vehicle Purchase Rate, affecting the fleet composition.

- Influences Total Mileage, as more vehicles lead to higher cumulative distance covered.

- The fleet size determines Driver Numbers and Driver Ratio per Vehicle, contributing to labor costs.

- Transition to hybrid or EV vehicles (via Replace Hybrid Vehicles and Replace EV Cars) reshapes the fleet for sustainability.

- Represents the cumulative distance covered by the fleet.

- Affected by the type of vehicles, with separate considerations for Avg. Mileage for PV (Private Vehicles) and Avg. Mileage for PCV (Product-Carrying Vehicles).

- Directly influences Fuel Costs, Maintenance, and Toll Fees, which feed into Total Costs.

- Higher mileage from fossil-fuel vehicles increases Carbon emissions, while hybrid and EV adoption reduces the emission rate.

- Drives Revenues, as mileage is a key factor in calculating earnings per mile.

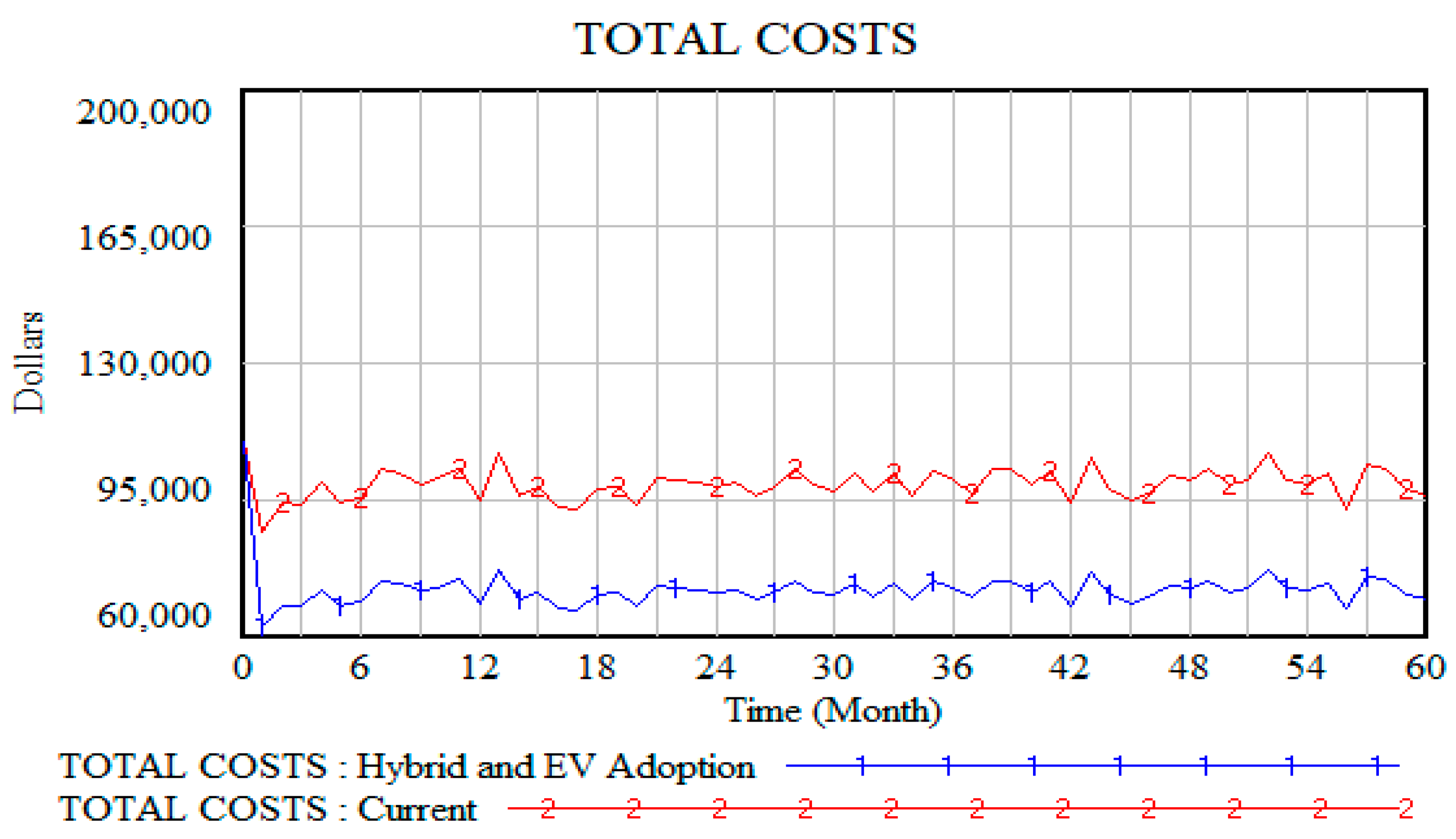

- Captures all expenses, including Fuel Costs, Maintenance, Toll Fees, Driver Costs, and Govt Tax.

- Influenced by Fleet Disposal (older vehicles are more expensive to maintain) and the adoption of Hybrid Vehicles and EV Cars, which reduce fuel and maintenance expenses.

- Higher mileage increases costs, particularly for fossil-fuel vehicles, but fuel savings from EV adoption mitigate these impacts.

- Directly affects Revenues, as cost adjustments can improve profit margins.

- Connected to Cost Adjustment Rate, allowing for operational efficiency evaluation.

- Represents income generated from fleet operations, determined by Earning per Mile and total mileage.

- Dependent on operational efficiency, as higher Total Costs reduce profit margins.

- Influenced by the repayment rate, which reflects installment payments for new vehicles, including hybrids and EVs.

- Disposal Rate contributes to revenues through the sale of decommissioned vehicles.

- A strong focus on sustainability (via hybrid and EV adoption) increases long-term profitability by reducing operational costs and carbon penalties.

- It reflects total greenhouse gas emissions from the fleet, which are influenced by the carbon emission rate and total mileage.

- High emissions are driven by fossil-fuel vehicles, while Hybrid Vehicles and EV Cars significantly reduce carbon output.

- Connected to the percentage of carbon reduction, which tracks the environmental impact of adopting sustainable technologies.

- Carbon reduction strategies influence policy compliance and operational reputation, indirectly affecting Revenues.

- Long-term reductions in emissions align with lower fuel consumption and maintenance costs, as seen in the Total Costs variable.

Findings and Discussion

- I.

- Emerging EV Markets in Developing Nations: Any developing nation with a growing middle-class population is becoming a potential EV market due to rapid urbanization, which raises environmental awareness. For instance, India, Brazil, South Africa, and Bangladesh are countries with growing populations along with moderate education, infrastructural developments, and technological learning and facilities. These factors create opportunities for EV growth, especially in urban and semi-urban regions.

- II.

- Barriers to EV Adoption: Despite the promising potential, EV adoption in developing nations remains low due to economic constraints, limited infrastructure, and policy gaps. High upfront costs, inadequate charging infrastructure, and unreliable electricity are common challenges faced in countries like India and Nigeria.

- III.

- Urban-Centric Market Trends: The EV market in countries like Brazil is largely concentrated in urban centers, with rural areas having limited access. Similarly, India has seen growth in electric two-wheelers and three-wheelers, but the electric car and bus markets remain underdeveloped due to affordability and infrastructure limitations.

- IV.

- Dependence on Imported EV Models: Many developing nations rely heavily on imported EV models, driving up costs and limiting accessibility for middle- and lower-income groups. The lack of local manufacturing prevents economies of scale, making EVs less competitive and widely affordable.

- V.

- Progress Through Localized Initiatives: Some countries are making strides through innovative approaches. Kenya has seen growth in electric motorcycles driven by rising fuel costs and local startup support, while Indonesia is leveraging its nickel reserves to attract EV battery manufacturers and promote localized production.

- VI.

- Need for Targeted Policies and Investments: Developing nations must adopt targeted strategies, including promoting affordable EV models, expanding charging infrastructure, and creating incentives. These measures can help address barriers and leverage the growth potential of EV markets across diverse regions and demographics.

- I.

- Promote Affordable EV Models: To cater to price-sensitive consumers, governments must prioritize producing and promoting affordable EV models such as two-wheelers, three-wheelers, and small electric cars. India's focus on electric scooters and auto-rickshaws is a successful example of targeting affordability and accessibility, making EVs more viable for the general population.

- II.

- Develop Scalable Charging Infrastructure: Establishing cost-effective and scalable charging infrastructure is essential for widespread EV adoption. Leveraging solar-powered charging stations can address electricity reliability issues while simultaneously integrating renewable energy into the EV ecosystem, reducing reliance on conventional energy sources.

- III.

- Implement Tailored Policy Incentives: Clear and consistent policy frameworks, such as subsidies for manufacturers, reduced taxes on EV imports, and concessional financing for buyers, are crucial for lowering barriers to EV adoption. Additionally, region-specific policies should focus on rural electrification and underserved areas to ensure equitable access to EV technology.

- IV.

- Encourage Public-Private Partnerships: Governments should collaborate with private firms to accelerate charging networks and Infrastructure deployment. As demonstrated in the United States, public-private partnerships can ensure widespread coverage, leveraging private sector expertise and investment to create a sustainable EV ecosystem.

- V.

- Foster International Collaborations: Partnerships with global automakers and battery manufacturers can facilitate technology transfer and reduce production costs. Developing nations should also seek funding from international bodies to support EV initiatives, accelerate local production, and build a robust and sustainable transportation network.

- I.

- Short-term policy on introducing incentives and pilot infrastructure projects: In the immediate term, governments in developing countries should focus on creating financial incentives to make EVs more affordable. Subsidies for EV buyers, tax reductions, and concessional financing options can significantly lower the barriers to entry for consumers. Pilot projects to build localized charging infrastructure in urban centers can also serve as test cases for larger-scale implementation. Public-private partnerships can accelerate these projects, ensuring cost-effective solutions and quick deployment. For example, subsidized solar-powered charging stations could address both affordability and energy reliability issues.

- II.

- Medium-term on developing nationwide infrastructure and fostering partnerships: The focus should shift toward expanding EV infrastructure nationwide over the medium term. Developing a comprehensive charging station network, particularly in underserved rural areas, is critical to promoting widespread adoption. Governments must partner with private firms and international organizations to secure the necessary funding and technical expertise. India's FAME (Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles) initiative serves as a valuable model, combining infrastructure development with policy support. Furthermore, standardizing EV regulations across regions will reduce uncertainty for manufacturers and investors, encouraging them to participate in the market.

- III.

- Long-term policies on building renewable-integrated EV ecosystems and robust regulatory frameworks: In the long term, integrating renewable energy into EV ecosystems is essential to maximize their environmental benefits. Investments in renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind, should be prioritized to power EV charging networks sustainably. Robust regulatory frameworks must be established to ensure long-term market stability and innovation. Policies that promote domestic EV manufacturing can reduce reliance on imports, lowering costs and boosting local economies. International collaborations can further support the development of technology and infrastructure tailored to the needs of developing nations.

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Varma, M.; Mal, H.; Pahurkar, R.; Swain, R. Comparative analysis of green house gases emission in conventional vehicles and electric vehicles. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology 2020, 29, 689–695. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Kanwal, A.; Asim, M.; Pervez, M.; Mujtaba, M.; Fouad, Y.; Kalam, M. Transforming the transportation sector: Mitigating greenhouse gas emissions through electric vehicles (EVs) and exploring sustainable pathways. AIP Advances 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleel, M.; Nassar, Y.; El-Khozondar, H.J.; Elmnifi, M.; Rajab, Z.; Yaghoubi, E.; Yaghoubi, E. Electric vehicles in China, Europe, and the united states: Current trend and market comparison. Int. J. Electr. Eng. and Sustain. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ugwu, M.C.; Adewusi, A.O. International ev policies: A comparative review of strategies in the United States and Nigeria for promoting electric vehicles. International Journal of Scholarly Research and Reviews 2024, 4, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpås, M.; Flataker, A.F.; Sæle, H.; Torsæter, B.N.; Lindberg, K.B.; Jiang, S.; Sørensen, Å.L.; Botterud, A. Learning from the Norwegian electric vehicle success: An overview. IEEE Power and Energy Magazine 2023, 21, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Talreja, P.; Shrivastava, A. Performance evaluation of electric vehicle stocks: Paving a way towards green economy. In The international conference on global economic revolutions, Springer: 2023; Vol. 1999, pp 175-194.

- Ajanovic, A.; Siebenhofer, M.; Haas, R. Electric mobility in cities: The case of Vienna. Energies 2021, 14, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. A consumer-oriented incentive strategy for ev charging in multiareas under stochastic risk-constrained scheduling framework. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2022, 58, 5262–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, S.A.; Ahmad, F.; Al-Wahedi, A.M.A.; Iqbal, A.; Ali, A. Navigating the complex realities of electric vehicle adoption: A comprehensive study of government strategies, policies, and incentives. Energy Strategy Reviews 2024, 53, 101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-f.; de Rubens, G.Z.; Noel, L.; Kester, J.; Sovacool, B.K. Assessing the socio-demographic, technical, economic and behavioral factors of nordic electric vehicle adoption and the influence of vehicle-to-grid preferences. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 121, 109692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Wang, X.; Mendoza, J.C.; Ackom, E.K. Electricity (in) accessibility to the urban poor in developing countries. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: energy and environment 2015, 4, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, M.; Ghimire, L.P.; Kim, Y.; Aryal, P.; Khadka, S.B. Identification and analysis of barriers against electric vehicle use. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.M.; Menon, N.; Ermagun, A. Equitable distribution of electric vehicle charging infrastructure: A systematic review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 206, 114825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddoha, M.; Kashem, M.A.; Nasir, T. A review of transportation 5.0: Advancing sustainable mobility through intelligent technology and renewable energy. Future Transportation 2025, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashem, M.A.; Shamsuddoha, M.; Nasir, T. Sustainable transportation solutions for intelligent mobility: A focus on renewable energy and technological advancements for electric vehicles (evs) and flying cars. Future Transportation 2024, 4, 874–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, M.A.; Manikandan, K. Smart integration of renewable energy into transportation: Challenges, innovations, and future research directions. Journal of Renewable Energies 2024, 27, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liusito, J.R.; Pandowo, M.H.; Tielung, M.V. The influence of product review and consumer trust on consumer purchase intention of electric vehicle in manado. Jurnal EMBA: Jurnal Riset Ekonomi, Manajemen, Bisnis dan Akuntansi 2024, 12, 912–923. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.R.; Islam, M.T.; Islam, K.S.; Hossain, A. Closing the productivity gap in electric vehicle manufacturing: Challenges and solutions. Innovatech Engineering Journal 2024, 1, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashem, M.A.; Shamsuddoha, M.; Nasir, T. Smart transportation and carbon emission from the perspective of artificial intelligence, internet of things, and blockchain: A review for sustainable future. 2024.

- Ermagun, A.; Tian, J. Charging into inequality: A national study of social, economic, and environment correlates of electric vehicle charging stations. Energy Research & Social Science 2024, 115, 103622. [Google Scholar]

- Taljegard, M.; Walter, V.; Göransson, L.; Odenberger, M.; Johnsson, F. Impact of electric vehicles on the cost-competitiveness of generation and storage technologies in the electricity system. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14, 124087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonprong, S.; Punturasan, N.; Varnakovida, P.; Prechathamwong, W. Towards sustainable urban mobility: Voronoi-based spatial analysis of ev charging stations in bangkok. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P. Innovations in electric vehicle technology: A review of emerging trends and their potential impacts on transportation and society. Reviews of Contemporary Business Analytics 2021, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, M.S.; Sreenivasan, A.V.; Sharp, B.; Du, B. Well-to-wheel analysis of greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption for electric vehicles: A comparative study in oceania. Energy Policy 2021, 158, 112552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann, A.; Zenglein, M.J. China's leverage of industrial policy to absorb global value chains in emerging industries. Economic and Social Upgrading in Global Value Chains: Comparative Analyses, Macroeconomic Effects, the Role of Institutions and Strategies for the Global South 2022, 413-436.

- Patil, P. Electric vehicle charging infrastructure: Current status, challenges, and future developments. International Journal of Intelligent Automation and Computing 2019, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.T.; Sulaiman, N.B.; Hussain, M.S.; Jabir, M. Optimal management strategies to solve issues of grid having electric vehicles (ev): A review. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 33, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, F. Electric vehicles: Benefits, challenges, and potential solutions for widespread adaptation. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinloye, T.; Oluwatobi, O.; Ugboma, O.; Dickson, O.F.; Uzondu, C.; Mogaji, E. Driving the electric vehicle agenda in nigeria: The challenges, prospects and opportunities. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2024, 130, 104182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadian, G.; Khodayar, M.; Shahidehpour, M. Accelerating the global adoption of electric vehicles: Barriers and drivers. The Electricity Journal 2015, 28, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, S.; Zirogiannis, N.; Siddiki, S.; Duncan, D.; Graham, J.D. Overcoming the shortcomings of us plug-in electric vehicle policies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 113, 109291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, E.E.; Nguyen, V.N.; Michaelides, D.N. The effect of electric vehicle energy storage on the transition to renewable energy. Green Energy and Intelligent Transportation 2023, 2, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y. Public-private partnerships in the electric vehicle charging infrastructure in china: An illustrative case study. Advances in civil engineering 2018, 2018, 9061647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Steen, M.; Van Schelven, R.; Kotter, R.; van Twist, M.J.; Van Deventer Mpa, P. Ev policy compared: An international comparison of governments' policy strategy towards e-mobility. E-mobility in Europe: Trends and good practice 2015, 27-53.

- George, A.S. Strategic battery autarky: Reducing foreign dependence in the electric vehicle supply chain. Partners Universal International Research Journal 2024, 3, 168–182. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, S.C.; Teicher, H.; Meyboom, A. Infrastructure as social catalyst: Electric vehicle station planning and deployment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2015, 100, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amante García, B.; Canals Casals, L. Barriers to electrification: Analyzing critical delays and pathways forward. World electric vehicle journal 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, X.; Tan, S. Electric vehicle integration in coupled power distribution and transportation networks: A review. Energies 2024, 17, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Gong, K.; Li, A. Electric vehicle adoption and counter-urbanization: Environmental impacts and promotional effects. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2024, 132, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, T.; Dhar, S.; Painuly, J. Understanding barriers to electric vehicle adoption for personal mobility: A case study of middle income in-service residents in hyderabad city, india. Energy Policy 2022, 167, 112956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsey, N.; Nicholas, M. Update on electric vehicle costs in the united states through 2030. Int. Counc. Clean Transp 2019, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sierzchula, W.; Bakker, S.; Maat, K.; Van Wee, B. The influence of financial incentives and other socio-economic factors on electric vehicle adoption. Energy policy 2014, 68, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Zheng, J.; Jamal, A.; Zahid, M.; Almoshageh, M.; Safdar, M. Electric vehicles charging infrastructure planning: A review. International Journal of Green Energy 2024, 21, 1710–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VP, K. Gap analysis in eco categories, electric vehicle comparison and solutions to global transport challenges. Komunikácie-vedecké listy Žilinskej univerzity v Žiline 2023, 25, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddoha, M.; Kashem, M.A.; Nasir, T. Smart transportation logistics: Achieving supply chain efficiency with green initiatives. In Data analytics for supply chain networks, Springer: 2023; pp 243-258.

- Nayeem, M.H.; Moradi, S.; Hossain, N.U.I.; Shamsuddoha, M.; Islam, M.S. System dynamics modeling for assessing operational performance of an airport terminal. Case Studies on Transport Policy 2025, 19, 101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trend | Country | Features | Instance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy-driven Growth [12] | Norway, China | Government subsidies, tax exemptions, and stringent emission regulations. | Norway and China have achieved over 80% EV market share by offering incentives such as tax exemptions, toll-free access, and charging subsidies. |

| Infrastructure Expansion [13,14] | United States, Germany | Deployment of extensive charging networks and integration with renewable energy grids. | Germany and the US lead in charging network deployment, ensuring seamless long-distance travel for EV users. |

| Cost Competitiveness [21] | India, Southeast Asia | Introduction of affordable EV models targeting price-sensitive markets. | India and Southeast Asia focus on affordable EV models like two-wheelers and small cars, catering to price-sensitive populations. |

| Urban-centric Adoption [22] | Europe, Japan | Focus on urban areas with high population density and short commuting distances. | Europe prioritizes urban EV adoption due to dense populations and short commute distances, where charging infrastructure is more feasible. |

| Technological Innovations [23] | Tesla (U.S.), BYD (China) | Advanced battery technologies, extended ranges, and integrated autonomous driving features. | Tesla has advanced battery technologies with the development of the 4680 battery cell, which offers higher energy density, extended vehicle range, and reduced production costs. |

| Coal-centric Power Challenges [24] | India, South Africa | High reliance on coal-based electricity, reducing the environmental benefits of EV adoption. | India heavily relies on coal-based electricity, with NTPC Limited as one of the largest coal power producers. |

| Export-driven Production [25] | China, South Korea | Dominance in global EV manufacturing and export markets, driven by competitive production. | China, led by companies like BYD, dominates the global EV manufacturing market through highly competitive production practices and state-backed incentives. |

| Challenge | Examples | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Charging Infrastructure [26] | Nigeria, Bangladesh | Inadequate public charging stations restrict EV usability and convenience. |

| Unreliable Power Grids [11] | India, South Africa | Frequent power outages undermine charging reliability and consumer trust. |

| Urban-Rural Disparity [20,22] | Indonesia, Kenya | Charging infrastructure is concentrated in urban areas, excluding rural users. |

| Grid Capacity Constraints [27] | Pakistan, Vietnam | Overburdened grids are unable to support widespread EV adoption. |

| High Infrastructure Costs [28] | Philippines, Ghana | Lack of funding delays the deployment of essential charging networks. |

| Technology Gaps [29] | Uganda, Cambodia | Limited access to advanced charging technologies hinders adoption speed. |

| Policy Barrier | Example | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of financial incentives and affordable financing options [30] | India, Bangladesh | High upfront costs of EVs remain unaffordable for lower-income groups, limiting adoption. |

| Fragmented regulations and inconsistent policies [31] | Brazil, South Africa | Inconsistent EV adoption strategies create market uncertainty for manufacturers and buyers. |

| Absence of long-term renewable energy strategies [32] | Coal-dependent countries like India | The environmental benefits of EVs are diminished due to reliance on coal for electricity. |

| Limited public-private partnerships [33] | Nigeria, Vietnam | Insufficient infrastructure growth, including EV charging networks, hinders adoption. |

| Weak national EV strategies [34] | Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia | Failure to attract private-sector investment and build consumer confidence. |

| Over-reliance on imported EV technology [35] | African nations, Southeast Asia | Local industries lack growth opportunities, increasing dependency and costs. |

| Lack of EV-specific urban planning [36] | Latin America | Charging infrastructure fails to meet urban demand, leading to adoption bottlenecks. |

| Delayed implementation of emission mandates [37] | Brazil, South Asia | Slow regulatory changes reduce the urgency for manufacturers to shift to EV production. |

| Weak integration with public transport systems [38] | South Asia, Indonesia | EV adoption fails to address mass transit challenges, limiting environmental benefits. |

| Aspect | Example | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Rising urbanization and environmental awareness [39] | India, South Africa | Increased demand for affordable and sustainable transportation solutions drives EV market growth. |

| Growing middle class [40] | Brazil, Indonesia | Expanding middle-income populations provide a larger consumer base for EV adoption. |

| High upfront costs of Evs [41] | Bangladesh, Nigeria | Price-sensitive markets face reduced affordability, limiting ownership to higher-income groups. |

| Dependence on imports [35] | African nations, Southeast Asia | Lack of local manufacturing raises EV prices and restricts access in cost-sensitive regions. |

| Limited financing options [30,42] | Brazil, Vietnam | The absence of affordable financing leaves lower-income populations underserved. |

| Inadequate charging infrastructure [43] | Kenya, Pakistan | Insufficient charging networks restrict EV usage, particularly in rural and semi-urban areas. |

| Unreliable power grids [27] | South Africa, India | Frequent power outages reduce consumer trust and hinder charging network development. |

| Urban-rural disparity [20,22] | Indonesia, Sub-Saharan Africa | Rural areas lack basic electricity and charging infrastructure, limiting EV adoption outside cities. |

| Policy and regulatory gaps [44] | Brazil, Bangladesh | Weak incentives and inconsistent policies fail to attract investments and build consumer confidence. |

| Sl No | Vehicle | Total | Miles | Fuel Costs | Maintenance | Toll Fee | Driver | Tax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chicks | 51 | 269,057 | 4,098,678 | 793,373 | 473,019 | 746,418 | 77,274 |

| 2 | Feed | 24 | 71,930 | 1,511,757 | 419,032 | 67,650 | 208,408 | 25,579 |

| 3 | Comercial | 14 | 73,894 | 1,567,678 | 212,198 | 296,635 | 228,002 | 11,550 |

| 4 | Private | 21 | 28,546 | 300,882 | 182,025 | 6,260 | 15,790 | 51,820 |

| 5 | Milk | 8 | 14,624 | 235,515 | 119,220 | 600 | 33,848 | 24,078 |

| 6 | Egg | 10 | 54,963 | 971,999 | 306,599 | 246,949 | 197,409 | 35,142 |

| 7 | Project | 14 | 9,069 | 101,037 | 62,643 | 1,630 | 4,583 | 10,500 |

| Total | 142 | 522,083 | 8,787,546 | 2,095,090 | 1,092,743 | 1,434,458 | 335,943 | |

| Average Expenses per Mile | 16.83 | 4.01 | 2.09 | 2.75 | 0.64 | |||

| Time (Month) | 5 | 15 | 25 | 35 | 50 | 60 |

| Avg. Fuel Consumptions* | 39,092 | 40,625 | 37,764 | 41,814 | 38,461 | 37,530 |

| : Current Scenario | 97,731 | 101,563 | 94,409 | 104,534 | 96,152 | 93,824 |

| CARBON EMISSION* | 537,967 | 581,165 | 561,604 | 590,365 | 538,282 | 539,897 |

| : Current Scenario | 807,196 | 820,705 | 829,166 | 828,051 | 822,986 | 801,019 |

| Carbon Reduction* | 94,144 | 101,704 | 98,281 | 103,314 | 94,199 | 94,482 |

| : Current Scenario | 807,196 | 820,705 | 829,166 | 828,051 | 822,986 | 801,019 |

| NO. OF VEHICLES* | 149.2 | 149.38 | 150.67 | 151.42 | 150.4 | 150.06 |

| : Current Scenario | 149.2 | 149.38 | 150.67 | 151.42 | 150.4 | 150.06 |

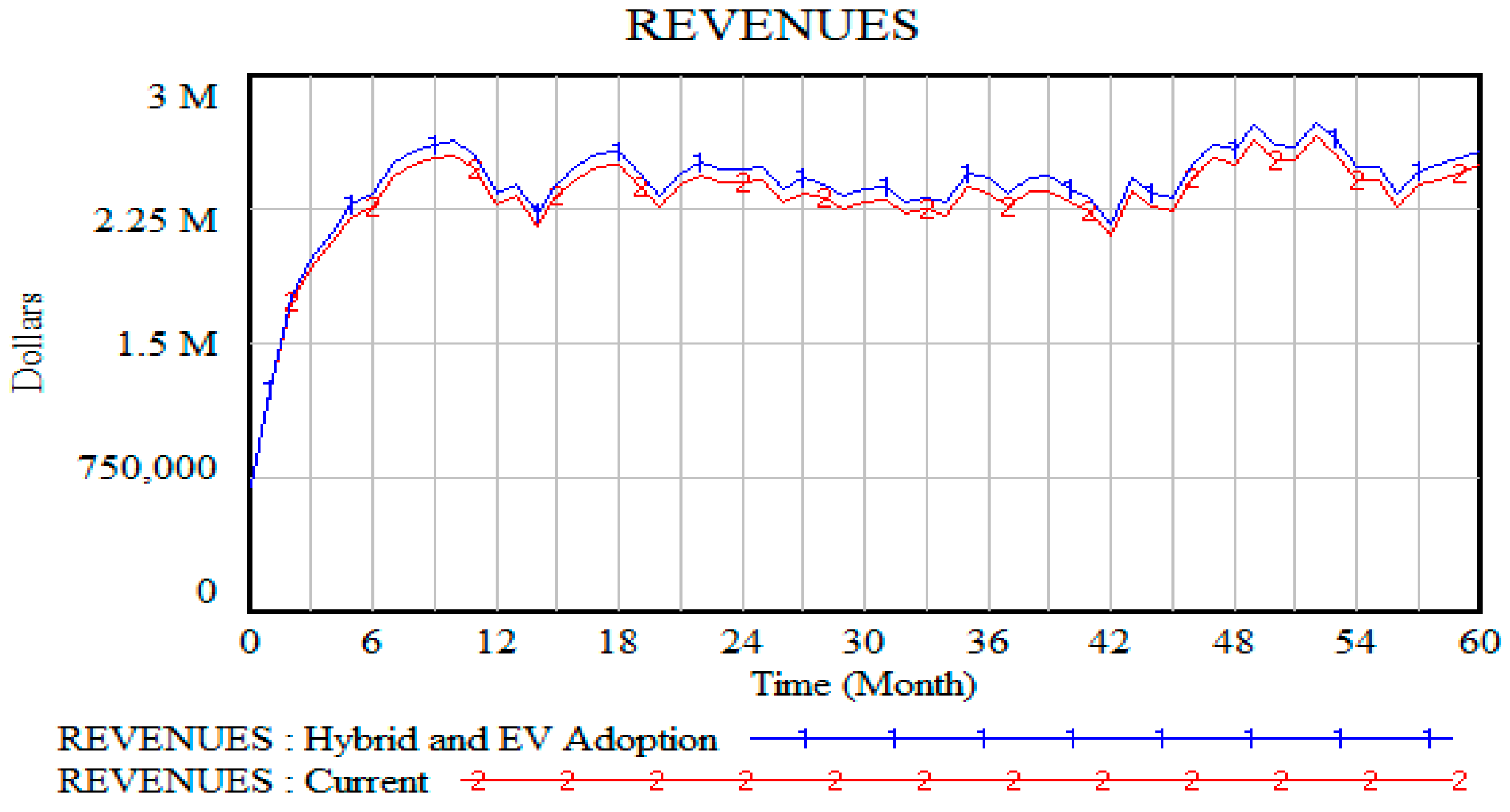

| REVENUES* | 2.272 M | 2.395 M | 2.484 M | 2.445 M | 2.608 M | 2.578 M |

| : Current Scenario | 2.208 M | 2.321 M | 2.410 M | 2.371 M | 2.528 M | 2.498 M |

| TOTAL COSTS* | 67,914 | 71,108 | 71,671 | 73,929 | 71,300 | 69,322 |

| : Current Scenario | 93,999 | 98,419 | 99,198 | 102,324 | 98,685 | 95,947 |

| TOTAL MILEAGE* | 548,896 | 531,885 | 534,216 | 565,995 | 580,274 | 543,548 |

| : Current Scenario | 548,896 | 531,885 | 534,216 | 565,995 | 580,274 | 543,548 |

| *Hybrid/EV adoption scenarios | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).