1. Introduction

Angular modifications in the physiological curvatures of the spine have been associated with spinal dysfunction and altered biomechanics, which may contribute to musculoskeletal complaints in adolescent populations. However, the relevance of these findings to adult populations requires further investigation [

1]. Angular modifications in these sagittal plane curvatures often indicate spinal disorders [

2]. Using finite element modelling, Cho et al. computed that maintaining an erect sitting posture with increased lumbar lordosis during seated activities effectively reduces intradiscal pressure and cortical bone stress associated with degenerative disc diseases and spinal deformities. However, direct evidence explicitly linking increased lumbar lordosis to elevated intradiscal pressure remains limited in the current literature. [

3]. Increased lumbar lordosis has been associated with elevated strain on passive spinal structures, particularly the facet joints, intervertebral discs, and posterior ligamentous complex. Such alterations may contribute to mechanical overload, altered load distribution, and potential dysfunction in spinal stability and movement patterns. [

4]. Additionally, viscoelastic creep in lumbar structures has been associated with pain and further dysfunction over time [

5]. Spinal curvatures play a critical role in human biomechanics by optimizing energy expenditure and movement efficiency. Abnormal adaptations in thoracic and lumbar spine biomechanics, however, can lead to low back pain and dysfunction. This dysfunction may manifest as altered neuromuscular control, compensatory muscle activation patterns, and increased mechanical stress on spinal structures, which have been implicated in musculoskeletal discomfort and movement impairments [

6].

A systematic review and meta-analysis found that people with low back pain display more synchronous [in-phase] horizontal pelvis and thorax rotations compared to healthy controls, highlighting significant changes in spinal biomechanics associated with low back pain. For instance, individuals with low back pain often exhibit altered gait mechanics. [

7]. Furthermore, individuals with low back pain frequently show biomechanical alterations, such as changes in spine/trunk kinematics and muscle activity during movement tasks, which can exacerbate dysfunction over time [4, 6, 8].

The lumbar erector spinae muscle [LES], a superficial back muscle, spans multiple spinal segments [

7]. Patients with low back pain display altered muscle activation patterns [

6]. These individuals may use LES to compensate for passive ligamentous laxity, reducing the excessive forces on the lumbar spine [

9]. There is evidence suggesting that individuals with chronic LBP exhibit delayed onset times of lumbar erector spinae [LES] activation compared to healthy individuals, as shown by Suehiro et al. This finding highlights the potential role of altered muscle timing in the pathophysiology of LBP [

10]. For instance, a systematic review and meta-analysis reported that individuals with chronic LBP demonstrate increased LES muscle activation during forward propulsion activities [

11].

Additionally, a study found that patients with nonspecific LBP displayed altered muscle synergies, including independent activation of the lumbar multifidus on the painful side, differing from the coordinated activation patterns observed in healthy subjects [

12].

These findings suggest that heightened LES activation is a common characteristic among LBP patients, potentially serving as a compensatory mechanism to enhance spinal stability. Exercises targeting the LES, such as prone trunk extension, are clinically applied to strengthen these muscles [

13]. A randomized controlled trial demonstrates that classification-specific treatment improved pain, disability, and fear-avoidance beliefs in individuals with low back pain. While the study did not directly assess postural abnormalities or the prevention of spinal disorders, it highlights the potential benefits of tailored interventions for managing low back pain [

14]. Strengthening the LES and thoracic extensors may reduce excessive thoracic kyphosis [

15]. These exercises not only strengthen but also lengthen and stretch the muscles [

16]. However, the effects of these exercises on individuals with altered spinal alignment, such as excessive thoracic kyphosis and compensatory lumbar lordosis, remain unclear [

12]. The hypothesis of this study is that variations in lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis angles will significantly affect muscle activations during three different low back exercises.

Recent studies have highlighted the prevalence of excessive thoracic kyphosis among athletes engaged in specific sports. For instance, a study examining adolescent female field hockey players found a significant increase in thoracic kyphosis compared to non-athletes, suggesting that the sport's postural demands may contribute to this condition [

17].

Additionally, research focusing on young athletes reported a high prevalence of postural abnormalities, including kyphosis, with 85% of the athletes exhibiting this condition [

18].

Increased lumbar lordosis has been reported in dancers and gymnasts [

19,

20]. Previous studies indicate that muscle activation patterns, rather than lumbopelvic motion alone, play a critical role in understanding biomechanical changes. Moreover, research suggests that increased lumbar lordosis may contribute to the risk of low back pain, particularly during prolonged standing. [

21]

Additionally, a study found a correlation between reduced skeletal muscle mass, altered lumbar lordosis, and chronic LBP, indicating that changes in lumbar curvature may influence muscle activation patterns associated with LBP [

22].

Therefore, the current research aims to investigate the effects of spinal alignment on muscle activations during prone trunk extension exercises.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This prospective study analysed the relationship between spinal alignment and muscle activation patterns of iliocostalis lumborum (ICL) and longissimus thoracis (LT) during three low back rehabilitation exercises. It was registered in the ctv.veeva.com Protocol Registration and Results System (clinical trial number: NCT05748548). The study was approved by the University of Health Sciences Gulhane Scientific Research Ethics Committee on November 22, 2022, with approval number 2022-338/ 46418926) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all 22 participants (14 females, 8 males). It was registered in the ctv.veeva.com Protocol Registration and Results System (clinical trial number: NCT05748548, date: 03/03/2023).

Participants were split into two groups based on lumbar lordosis and thoracic posture: G1 (hyper lordotic lumbar angle- increased thoracic kyphosis, n=11) and G2 (normal lordotic lumbar-thoracic angle, n=11). Both groups were matched for general and medical characteristics.

The age criteria for both groups is being between 18-24 years. Inclusion criteria for G1: who had lumbar lordosis angles of ≤45° and thoracic kyphosis angles ≥40°, while those in G2 who had angles within normal ranges. The classification of lumbar lordosis angles of ≤45° and thoracic kyphosis angles ≥40° aligns with established thresholds in the literature. Normal lumbar lordosis typically ranges from 20° to 45°, with hyper lordosis often defined as an angle exceeding this range. Similarly, normal thoracic kyphosis is between 20° and 40°, with angles greater than 40° indicating hyper kyphosis. Therefore, participants in G1, with lumbar lordosis angles of ≤ 45° and thoracic kyphosis angles ≥40°, fall within these established parameters for hyper lordosis and increased kyphosis [23-25].

Exclusion criteria included metabolic, neuromuscular, or musculoskeletal conditions, previous spinal surgery, or participation in muscle-strengthening training within the last six months. None of the participants had experienced back or chest pain in the past year, and none reported pain during the tests.

2.2. Instrumentation

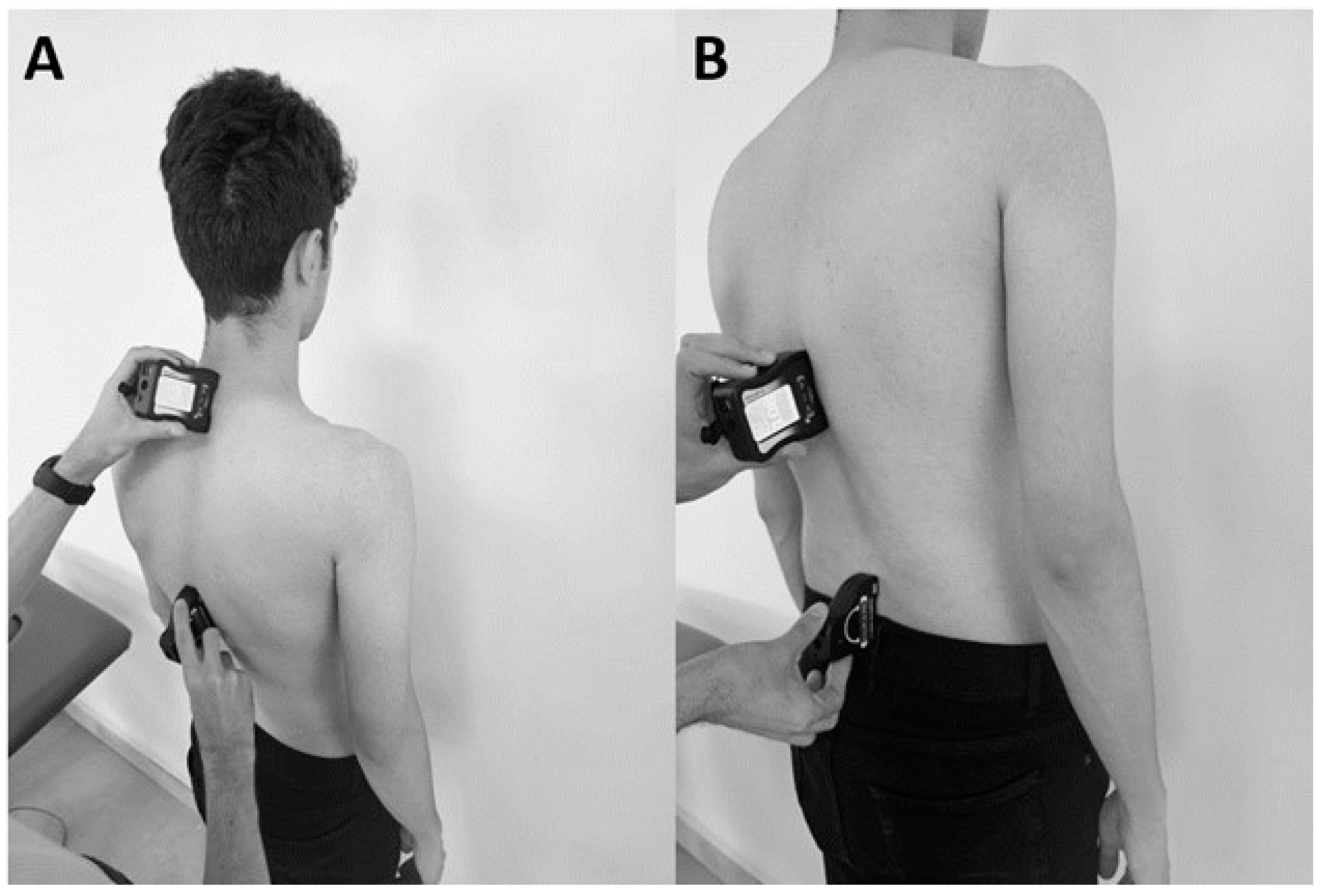

Subjects were asked to stand with their feet shoulder-width apart, their arms folded, and their hands on their chest for the measurements of lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis. Subjects were asked to stand with their feet shoulder-width apart, their arms folded, and their hands on their chest while having their lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis angles assessed using a dual inclinometer (Baseline®, Aurora, IL, USA). Measurements were made by a PhD graduate evaluator with eighteen years of experience in the physiotherapy profession. Hunter et al. demonstrated that the gravity-dependent inclinometer provides angle measurements comparable to those obtained using the modified Cobb method on radiographs, confirming its validity as a reliable and safe clinical tool for assessing thoracic kyphosis [

26].

The inclinometer sensors were positioned using the spinous processes of the first thoracic vertebra (T1), the twelfth thoracic vertebra (T12), and the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) (

Figure 1). The L5 spinous process, which is the most prominent spinal process, was located above the sacrum, the T12 spinous process was located superior to the L1 point spinal process, and the T1 spinal process was located inferior to the seventh cervical vertebra. Then, using the inclinometers, the angles between T1 and T12 and between L5 and T12 were measured to evaluate thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis, respectively.

2.2.1. Electromyography (EMG) Protocol

Electromyographic (EMG) data were acquired using a Noraxon Ultium EMG sensor system (Noraxon USA, Inc., Scottsdale, AZ, USA) with a sampling frequency of 4000 Hz per channel, gain of 1000, signal-to-noise ratio of 1 μV root mean square (RMS), common mode rejection ratio (CMRR) of −100 dB, and input impedance >100 mΩ. Before electrode placement, the skin was prepared by removing hair and cleansing the area with an alcohol swab to ensure signal quality. Bipolar surface electrodes were used, placed bilaterally on the iliocostalis lumborum pars lumborum (ICL) at the L3 spinal level, the longissimus thoracis (LT) at T9, and the iliocostalis lumborum pars thoracis (ICT) at T10. The electrodes were positioned midway between the lateral-most palpable border of the erector spinae and a vertical line through the posterosuperior iliac spine, based on SENIAM guidelines, and spaced at a 2 cm interelectrode distance [

27,

28].

The standardization of resistance was aimed at improving comparability across subjects and minimizing variability. However, to account for individual strength differences, resistance was applied progressively, and each participant exerted their maximum voluntary effort. This approach ensured that MVIC values reflected true maximal exertion rather than absolute resistance levels.

To ensure the accuracy of MVICs, investigators provided verbal encouragement during each test to maximize participant effort. Different testing maneuvers were carefully employed for each muscle group to ensure specific muscle activation. Investigators performing the MVIC tests were blinded to participant grouping to minimize bias and ensure consistency in data collection.

To minimize crosstalk from adjacent muscles, electrode placement adhered strictly to the SENIAM recommendations, and rigorous filtering was applied to the recorded data. A band-pass filter (10-500 Hz) using a first-order high-pass and fourth-order low-pass Butterworth filter was applied, along with a notch filter at 60 Hz to remove powerline noise. Additionally, potential electrocardiographic (ECG) artifacts in signals recorded from the thoracic region were filtered. The RMS values were calculated using a 100 ms moving window. Each trial's EMG data were normalized to the mean RMS of the maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC), expressed as a percentage (%MVIC). The mean %MVIC from three trials was used for analysis. The Noraxon MyoResearch XP software (version 3.16; Noraxon USA, Inc.) processed all data.

2.3. Procedures

The exercise protocol consisted of three distinct phases: concentric, isometric, and eccentric. To control the speed of the concentric and eccentric phases, a 30-bpm rhythm was played with the help of a metronome, and the exercises were performed in accordance with this. The isometric phase was maintained for 10 seconds during each repetition (3 repetitions for each movement). Participants rested for 30 seconds between repetitions and took a one-minute break between exercises to mitigate fatigue. Exercises were performed in a randomized order using predefined sequences (e.g., 1-2-3, 3-2-1, 2-1-3, 2-3-1).

Exercise Descriptions:

Prone Thoracic Extension (PTE): Participants were positioned prone on a plinth, with the head aligned at the midline and arms relaxed by their sides. For the exercise, the arms were crossed over the chest, the legs remained flat on the plinth, and the trunk was extended to the maximum possible range while maintaining a neutral head position.

Superman Exercise (SE): Participants were positioned prone with shoulders abducted to 180 degrees and elbows extended. Both the upper and lower extremities were lifted simultaneously off the surface to achieve a full-body extension.

Unstable Superman Exercise (USE): A Swiss ball was placed beneath the umbilicus of the participants. The feet were positioned shoulder-width apart, flat against a wall for support, and the legs were fully extended. While prone on the Swiss ball, the arms, hips, and legs were simultaneously extended to maintain a balanced position throughout the movement.

Proper form was emphasized, and real-time verbal feedback was provided to ensure consistent technique. The protocol standardized exercise intensity and reduced variability through objective timing and positional guidance.

Figure 2.

The low back exercises (A: Prone thoracic extension (PTE), B: Superman exercise (SE), C: Unstable superman exercise (USE).

Figure 2.

The low back exercises (A: Prone thoracic extension (PTE), B: Superman exercise (SE), C: Unstable superman exercise (USE).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The sample size for the study was determined using prior reference studies reporting an effect size of 1.3, which indicated that a minimum of 11 participants per group would be required to achieve a statistical power of 80% at a significance level of p < 0.05 [

29].

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS (version 26.0). T-test performed to determine if “general and medical characteristics” were not different. To evaluate the muscle activity differences, a three-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed. The analysis included the following factors: group (two levels: intervention and control), muscle (multiple levels, representing each analyzed muscle), and exercise (multiple levels, representing different exercise types). Interaction effects between these factors (group × muscle, group × exercise, muscle × exercise, and group × muscle × exercise) were thoroughly examined. Following significant main or interaction effects, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests were applied to determine specific differences between conditions. These post hoc tests ensured control over Type I error while identifying significant pairwise differences

Between-group comparisons were explicitly analyzed for each muscle to assess whether group-specific differences in muscle activity existed across the exercises. This approach ensured the analysis addressed all relevant hypotheses and provided detailed insights into group, muscle, and exercise interactions. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

There were no statistically significant differences between G1 and G2 in terms of age, sex, height, or mass (p >0.05). However, significant differences were observed in thoracic kyphotic angles and lumbar lordosis angles between the groups. G2 exhibited significantly lower thoracic kyphotic angles compared to G1 (p < 0.001, η² = 0.34), while lumbar lordosis angles were significantly higher in G2 than in G1 (p < 0.001, η² = 0.39) (

Table 1).

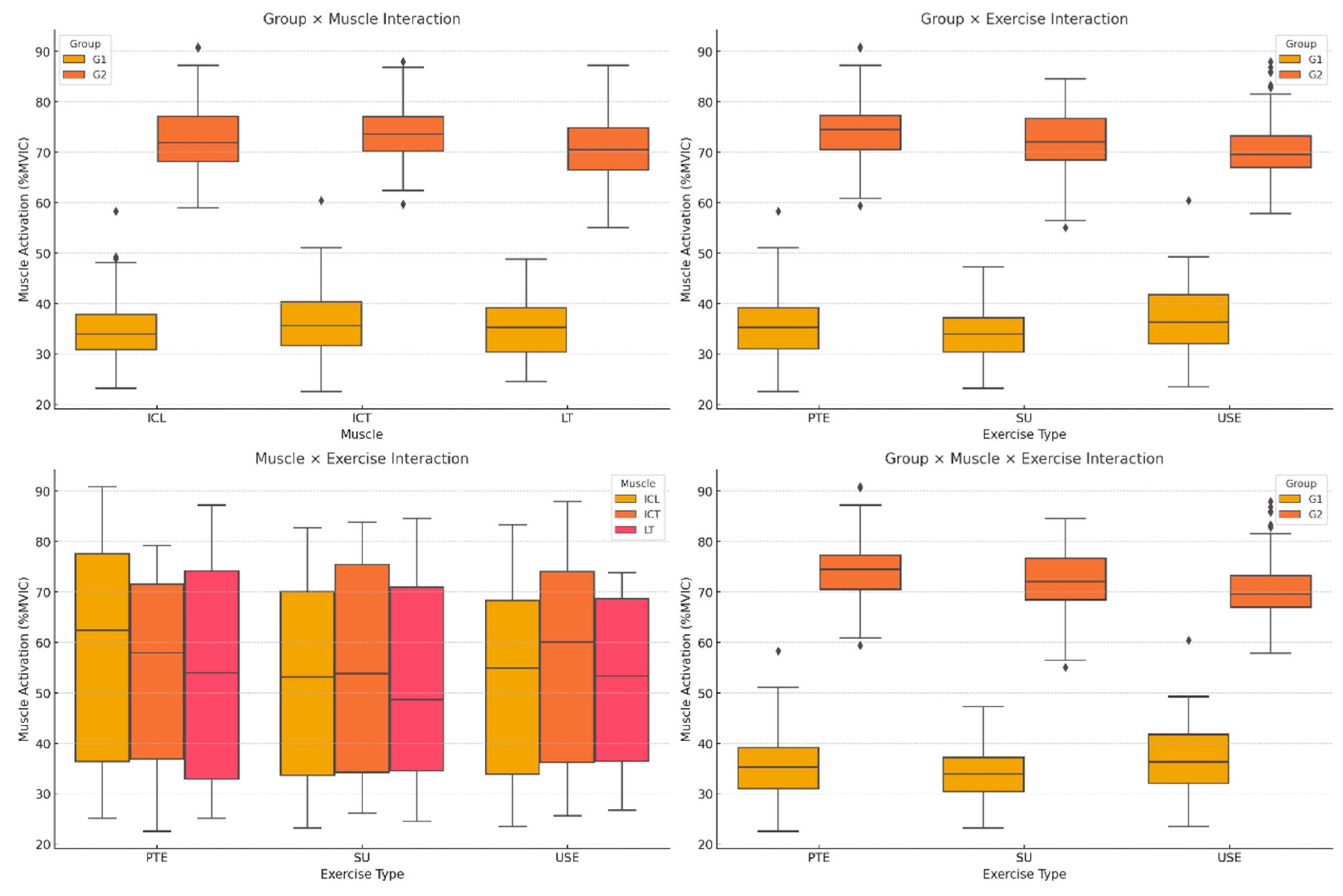

Figure 3.

Muscle Activation Differences Across Groups and Exercises.

Figure 3.

Muscle Activation Differences Across Groups and Exercises.

Inter-group comparisons of iliocostalis thoracis (ICT) and longissimus thoracis (LT) muscle activation revealed that G2 exhibited significantly higher activation across all exercises compared to G1 (p = 0.009, η² = 0.28,

Figure 1). This difference was most pronounced in ICT and LT, where G1 displayed significantly lower activation levels than G2 (p = 0.004, η² = 0.31). The exercise type also had a significant effect, with Unstable Superman Exercise (USE) eliciting the highest activation across all muscles (p < 0.001, η² = 0.37,

Figure 1).

The interaction between muscle and exercise showed that ICT and LT activation increased progressively with exercise complexity, while ICL activation remained relatively lower across all exercises (p = 0.012, η² = 0.25,

Figure 1). Furthermore, the three-way interaction between group, muscle, and exercise confirmed that G2 exhibited consistently higher activation across all conditions, particularly in USE, whereas G1 displayed lower and more uniform activation patterns across exercises (p = 0.006, η² = 0.29,

Figure 1).

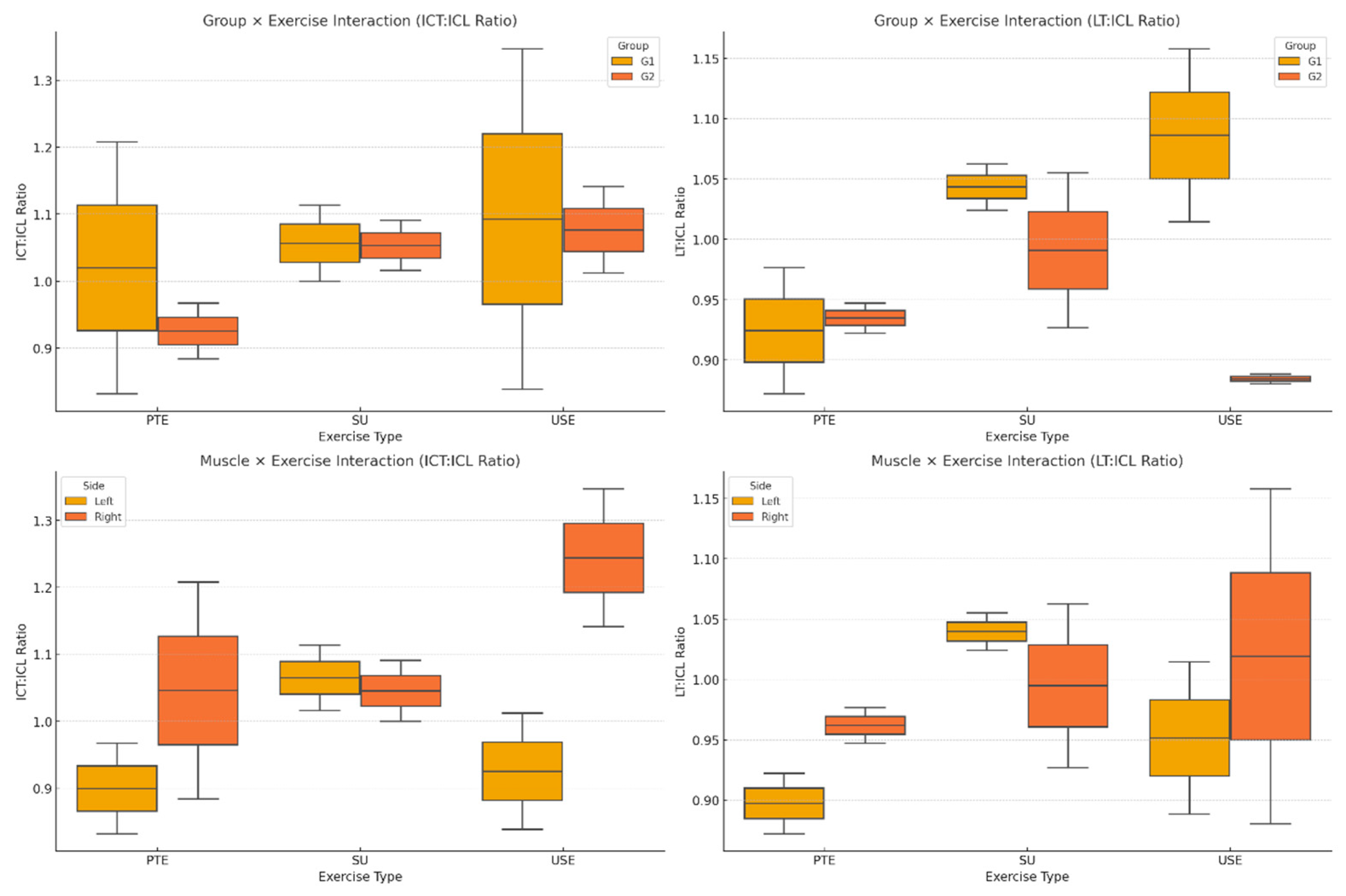

Figure 4.

ICT:ICL and LT:ICL Ratios Across Groups and Exercises.

Figure 4.

ICT:ICL and LT:ICL Ratios Across Groups and Exercises.

The ICT:ICL and LT:ICL ratios were significantly different across groups and exercises (p = 0.008, η² = 0.26,

Figure 2). The group-by-exercise interaction revealed that G2 had higher ICT:ICL and LT:ICL ratios than G1 across all exercises, with the greatest difference observed in the USE condition (p = 0.003, η² = 0.32). These findings suggest that exercise complexity plays a critical role in influencing muscle coordination and relative activation.

The interaction between muscle ratio and exercise indicated that side differences (left vs. right) did not significantly influence ICT:ICL and LT:ICL ratios (p = 0.070, η² = 0.19). However, the USE exercise showed greater variability in these ratios compared to PTE and SU (p = 0.014, η² = 0.24,

Figure 2). This suggests that the instability introduced in USE may contribute to greater fluctuations in neuromuscular coordination, particularly in the LT:ICL ratio.

4. Discussion

This study concluded that hyperlordosis and excessive thoracic kyphosis affect muscle activation during different lower back exercises. The superficial EMG results for the iliocostalis lumborum (IL) and longissimus thoracis (LT) muscles were analyzed during prone trunk extension, stable Superman, and Unstable Superman exercises.

Regarding the iliocostalis lumborum pars lumborum, the G1 group showed greater muscle activity than the normal group. This may be due to the inability of the thoracic part to exhibit sufficient activity, leading to compensation by the lumbar region. The authors also calculated the thoracic-to-lumbar activity ratio, finding that the G1 group had a lower thoracic-to-lumbar ratio. Park et al. also found that this ratio was lower in the thoracic kyphotic group during trunk extension exercises. This result aligns with the current study, where the same outcome was observed in two other exercises. However, in this study, the effect sizes for the differences in thoracic and lumbar muscle activation were higher (η² = 0.34–0.39), indicating a stronger relationship between spinal curvature and compensatory muscle activation than previously reported. From this perspective, exercises aimed at correcting thoracic kyphosis may involve insufficient thoracic muscle activity [

27].

Park et al. reported that hyperkyphotic individuals exhibited less muscle activity during prone trunk extension exercises. The current study found similar results in the hyperlordotic and kyphotic groups during this exercise. Additionally, the same group demonstrated lower muscle activity during the Superman and Unstable Superman exercises. In this study, group differences in EMG activity across exercises showed strong effect sizes (η² = 0.28–0.37), reinforcing the notion that hyperlordotic and kyphotic individuals exhibit significantly lower activation levels across dynamic postural exercises. As Park concluded, while the aim of exercises for kyphosis and hyperlordosis may be appropriate, they may not achieve the desired muscle activation [

27]. The authors suggest that future research should explore different exercise modifications to address this issue.

Carvalheiro Reiser et al. [

30] investigated paravertebral muscle activity during the Unstable Superman Exercise and found that both iliocostalis and longissimus muscles exhibited higher activity compared to the Stable Superman Exercise. Similarly, this study observed greater muscle activity in the Unstable Superman Exercise compared to both prone trunk extension and the Stable Superman Exercise. The effect of exercise instability on muscle activation in this study was substantial (η² = 0.25–0.32), confirming that neuromuscular demand increases with movement complexity. Multiple studies have examined the effectiveness of performing exercises on unstable surfaces [31-33].

As observed in these studies, an unstable surface tends to generate greater muscle activity, which is consistent with the current findings. The authors suggest that using an unstable surface presents a challenge that increases concentration and encourages greater muscular participation. Additionally, this study found that the interaction between instability and muscle activity had a significant effect (p = 0.006, η² = 0.29), suggesting that individuals with altered spinal curvatures may require greater stabilization efforts to achieve optimal muscle engagement. Another study examining the effect of an unstable surface in the sitting position on lumbar and thoracic muscle activity found no significant differences between the conditions. This may be due to the lack of muscle strain in the sitting position, despite the unstable surface [

34].

A study examining posterior muscle chain activity during different extension exercises found no significant differences between iliocostalis lumborum pars thoracis and pars lumborum. This finding is consistent with the results of the group with normal spinal curvatures in this study [

35]. However, the present study demonstrated that G2 exhibited significantly higher thoracic-to-lumbar activation ratios than G1 (η² = 0.26), further supporting the hypothesis that normal spinal curvature enhances thoracic muscle function during extension exercises.

This study could have included individuals with both thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis. The effect of unstable surfaces on muscle activity during prone extension exercises could also be further explored. Although a validation study was added regarding the measurement of thoracic kyphosis with an inclinometer, no measurement validity was found regarding lumbar lordosis.

This study only examined the acute effects of spinal alignment on muscle activation, without investigating long-term outcomes. Future research should investigate whether these acute activation patterns translate into long-term neuromuscular adaptations, particularly in hyperlordotic and kyphotic individuals. Incorporating follow-up measurements in future research could provide valuable insights into the sustained impact of these findings over time.

5. Conclusions

The muscle response obtained from prone extension, Superman, and Unstable Superman exercises—commonly recommended for lower back and thoracic regions—may be associated with individual lumbar and thoracic curvatures. Given the strong effect sizes observed in this study, posture-correcting exercises should be integrated into rehabilitation and strength training programs to enhance thoracic and lumbar muscle function. Incorporating posture-correcting exercises into programs may increase the effectiveness of these exercises for spinal muscles.

Author Contributions

ESA, DT, and TYŞ made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. ESA and ÇS were involved in the acquisition of data, and ESA, TYŞ, and NÜY contributed to data analysis and interpretation. ESA drafted the manuscript, while DT and NÜY critically revised it for intellectual content. All authors have approved the submitted version, agree to be personally accountable for their contributions, and will ensure that any questions regarding the integrity or accuracy of the work are appropriately addressed and resolved.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the University of Health Sciences Gulhane Scientific Research Ethics Committee on November 22, 2022, with approval number 2022-338/ 46418926) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent forms were obtained from the patients. Complete written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data illustrated in the present study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Smith, A.; O'Sullivan, P.; Straker, L. Classification of sagittal thoraco-lumbo-pelvic alignment of the adolescent spine in standing and its relationship to low back pain. Spine 2008, 33, 2101–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muyor, J.M.; Antequera-Vique, J.A.; Oliva-Lozano, J.M.; Arrabal-Campos, F.M. Evaluation of dynamic spinal morphology and core muscle activation in cyclists—a comparison between standing posture and on the bicycle. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22, 9346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.; Han, J.-S.; Kang, S.; Ahn, C.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, K.-T.; Kim, A.-R.; Hwang, J.-M. Biomechanical effects of different sitting postures and physiologic movements on the lumbar spine: A finite element study. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd Rahman, N.A.; Li, S.; Schmid, S.; Shaharudin, S. Biomechanical factors associated with non-specific low back pain in adults: A systematic review. Phys. Ther. Sport 2023, 59, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Kordi Yoosefinejad, A.; Motealleh, A.; et al. Comparison of flexion relaxation phenomenon between female yogis and matched non-athlete group. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.W.; Danneels, L. Changes in structure and function of the back muscles in low back pain: Different time points, observations, and mechanisms. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 49, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Stabbert, H.; Bagwell, J.J.; Teng, H.L.; Wade, V.; Lee, S.P. Do people with low back pain walk differently? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sport Health Sci. 2022, 11, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S.; Bangerter, C.; Schweinhardt, P.; Meier, M.L. Identifying motor control strategies and their role in low back pain: A cross-disciplinary approach bridging neurosciences with movement biomechanics. Front. Pain Res. 2021, 2, 715219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkery, M.B.; O'Rourke, B.; Viola, S.; Yen, S.C.; Rigby, J.; Singer, K.; Thomas, A. An exploratory examination of the association between altered lumbar motor control, joint mobility and low back pain in athletes. Asian J. Sports Med. 2014, 5, e24283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suehiro, T.; Mizutani, M.; Ishida, H.; Kobara, K.; Osaka, H.; Watanabe, S. Individuals with chronic low back pain demonstrate delayed onset of the back muscle activity during prone hip extension. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2015, 25, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.W.; Ugbolue, U.C.; Gao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Baker, J.S.; Dutheil, F. Erector spinae muscle activation during forward movement in individuals with or without chronic lower back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2023, 5, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wattananon, P.; Silfies, S.P.; Tretriluxana, J.; Jalayondeja, W. Lumbar multifidus and erector spinae muscle synergies in patients with nonspecific low back pain during prone hip extension: A cross-sectional study. PM R 2019, 11, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateuchi, H.; Taniguchi, M.; Mori, N.; Ichihashi, N. Balance of hip and trunk muscle activity is associated with increased anterior pelvic tilt during prone hip extension. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2012, 22, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-H.; Park, K.-N.; Kwon, O.-Y. Classification-specific treatment improves pain, disability, fear-avoidance beliefs, and erector spinae muscle activity during walking in patients with low back pain exhibiting lumbar extension-rotation pattern: A randomized controlled trial. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 2020, 43, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elpeze, G.; Usgu, G. The effect of a comprehensive corrective exercise program on kyphosis angle and balance in kyphotic adolescents. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufail, M.; Lee, H.; Moon, Y.G.; Kim, H.; Kim, K. The effect of lumbar erector spinae muscle endurance exercise on perceived low-back pain in older adults. Phys. Activ. Rev. 2021, 9, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, R.; Mobarakabadi, L.; Alizadhen, H.M.; Hendrick, P. Thoracic kyphosis comparisons in adolescent female competitive field hockey players and untrained controls. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2012, 52, 545–550. [Google Scholar]

- Babagoltabar Samakoush, H.; Norasteh, A. Prevalence of postural abnormalities of spine and shoulder girdle in Sanda professionals. Ann. Appl. Sport Sci. 2017, 5, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambegaonkar, J.P.; Caswell, A.M.; Kenworthy, K.L.; Cortes, N.; Caswell, S.V. Lumbar lordosis in female collegiate dancers and gymnasts. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 2014, 29, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Hemecourt, P.A.; Hresko, M.T. Spinal deformity in young athletes. Clin. Sports Med. 2012, 31, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, C.J.; Norton, B.J.; Callaghan, J.P.; Hwang, C.T.; Van Dillen, L.R. Is lumbar lordosis related to low back pain development during prolonged standing? Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.W.; Park, S.J.; Chung, S.G. Relationships between skeletal muscle mass, lumbar lordosis, and chronic low back pain in the elderly. Neurospine 2023, 20, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.M.; Jou, I.M.; Yu, C.Y. Lumbar lordosis: normal adults. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 1992, 91, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ulmar, B.; Gühring, M.; Schmälzle, T.; Weise, K.; Badke, A.; Brunner, A. Inter- and intra-observer reliability of the Cobb angle in the measurement of vertebral, local and segmental kyphosis of traumatic lumbar spine fractures in the lateral X-ray. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2010, 130, 1533–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perriman, D.M.; Scarvell, J.M.; Hughes, A.R.; Ashman, B.; Lueck, C.J.; Smith, P.N. Validation of the flexible electrogoniometer for measuring thoracic kyphosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010, 35, E633–E640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J.; Rivett, D.A.; McKiernan, S.; Weerasekara, I.; Snodgrass, S.J. Is the inclinometer a valid measure of thoracic kyphosis? A cross-sectional study. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2018, 22, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.H.; Kang, M.H.; Kim, T.H.; An, D.H.; Oh, J.S. Selective recruitment of the thoracic erector spinae during prone trunk-extension exercise. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2015, 28, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegeman, D.; Hermens, H. Standards for Surface Electromyography: The European Project Surface EMG for Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles (SENIAM); Roessingh Research and Development: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.-A.; Jung, S.-H. Comparison of muscle activity of the erector spinae according to thoracic spine extension mobility. J. Musculoskelet. Sci. Technol. 2021, 5, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheiro Reiser, F.; Gonçalves Durante, B.; Cordeiro de Souza, W.; Paulo Gomes Mascarenhas, L.; Márcio Gatinho Bonuzzi, G. Paraspinal muscle activity during unstable superman and bodyweight squat exercises. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2017, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, Y.; Chung, Y. The influence of an unstable surface on trunk and lower extremity muscle activities during variable bridging exercises. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2014, 26, 521–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bervis, S.; Kahrizi, S.; Parnianpour, M.; Amirmoezzi, Y.; Shokouhi, M. Effect of pelvic tilt on kinematics and electromyographic activities of lumbar spine muscles during asymmetric lifting tasks. Hum. Factors 2020, 62, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Bhanot, K.; Ferreira, G. Lower extremity and trunk electromyographic muscle activity during performance of the Y-balance test on stable and unstable surfaces. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2022, 17, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, P.; Dankaerts, W.; Burnett, A.; et al. Lumbopelvic kinematics and trunk muscle activity during sitting on stable and unstable surfaces. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2006, 36, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, E.M.; Van Oosterwijck, J.O.; Vleeming, A.; Vanderstraeten, G.G.; Danneels, L.A. Posterior muscle chain activity during various extension exercises: An observational study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).