1. Introduction

Hypopressive Exercise (HE) has emerged as a postural and breathing-based rehabilitation exercise program used by therapists in the training of trunk stabilizing musculature such as the diaphragm, transverse abdominis, and pelvic floor muscles [

1]. Although previous studies have explored the application of HE in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunctions [

2], more recently HE has been applied as an alternative program for adults with non-specific low back pain [

3], and shoulder dysfunction [

4]. HE combines conventional postural reeducation principles with specific breathing exercises performed with or without the assistance of a wall [

1]. HE is commonly performed with a specific shoulder girdle positioning of arms elevated at 90 degrees of humeral elevation and shoulder internal rotation [

5]. The breathing standard of HE is based on slow lateral-costal breathing followed by an abdominal vacuum maneuver. This breathing maneuver is performed through an end-expiratory breath-hold followed by contraction of the accessory inspiratory musculature to enable the maintenance of the thoracic cage elevated while holding the breath [

5].

The Serratus Anterior (SA) and the latissimus dorsi (LD) have been hypothesized to be involved during HE due to the rib-cage lift during the abdominal vacuum maneuver and the arm position. The SA aids in lifting the ribs during inspiration when the shoulder complex is fixed [

6]. SA muscular weakness can contribute to altered scapular kinematics such as winged scapula with postural alterations [

7,

8]. The SA is one of the main stabilizers of the scapula and its main function is scapulothoracic protraction and upward humeral rotation [

9]. While the SA scapular stabilization function and assistance for the optimal motion of the shoulder complex is well known, its muscle activation through breathing maneuvers such as HE is less explored. An electromyographic study on healthy adult females revealed that HE was able to activate SA and other accessory respiratory muscles (scalene and sternocleidomastoid), especially during standing and seated HE positions [

10].

The selection of optimal exercises for musculoskeletal rehabilitation is a primary concern for therapists. The increased use of HE as a means to increase inspiratory muscle strength [

11] and reduce shoulder pain [

4], contrasts with the lack of studies assessing the level of SA and LD muscle activation during a variety of HE. Previous studies with surface electromyography (sEMG) have analyzed the neuromuscular activation of the abdominal, pelvic floor, and accessory respiratory muscles during HE in standing, supine, or seated open kinetic chain body positions [

2,

10,

12]. Nonetheless, no previous studies have explored SA and LD muscle activation during HE performed in closed kinetic chain positions.

Closed kinetic chain exercises are widely used in the initial treatment of shoulder dysfunctions to enable an increase of muscular activation in the periscapular stabilizing muscles while decreasing the involvement of prime movers of the shoulder [

13,

14]. Several closed kinetic chain exercises involving scapular protraction (i.e. push-up, plank, wall-press) have been reported as efficient in maintaining the optimal activation of the SA [14-16]. Exercise body position, surface of contact, and shoulder motion are other determinant factors to consider when selecting exercises for SA muscle rehabilitation [

13]. Closed kinetic chain exercises performed against a wall such as a wall press or wall slide are commonly prescribed in programs for SA rehabilitation [

17] and have demonstrated elicit higher levels of muscle activation in comparison to open kinetic chain exercises. HE is commonly performed in a closed-kinetic chain with the assistance of a wall to hypothetically elicit greater shoulder girdle activation.

Therefore, we aimed to describe sEMG activation levels and compare differences between SA and LD while performing standard HE in open and closed kinetic chain positions. Due to the periscapular stabilization and inspiratory functions of SA and LD [

18,

19], we hypothesized that these muscles would be activated during HE and that closed kinetic chain positions would achieve greater muscle recruitment than open kinetic chain positions during HE.

2. Results

All participants completed study-related tests successfully, and no unexpected adverse events or injuries occurred during the study. Participants' levels of physical activity were mostly high (44%) and moderate (52%) whereas only 4% accumulated low levels of physical activity. The average years of HE training practice were 3.83 (SD, 3.51) and the mean weekly training frequency was 2.24 days (SD, 1.69). 24 participants' dominant side was right and only one participant’s dominant side was left. The demographic and anthropometric descriptive data of participants are presented in

Table 1. The descriptive data of results by exercises and chain type are presented in

Table 2.

The descriptive sEMG values for each exercise and kinetic chain condition are presented in

Table 2. Across all exercises, SA activation was higher than LD. SA activation levels ranged from 20–40% of MVIC, characterized as moderate activity. LD activation levels were below 20% of MVIC in all conditions, indicating low activation levels.

The analysis of muscle activation by kinetic chain condition revealed significant differences for the left LD, with higher activation in the closed-chain condition with a small effect size (p=0.03; r=0.19) (see

Table 3). No significant differences for neuromuscular activation were observed for SA or right LD between kinetic chain conditions.

When muscle activation between exercise positions is analyzed, the results reveal significant differences between standing, kneeling, and seated positions for the left SA (p<0.001;

ε²=0.09), left LD (p=0.04;

ε²=0.04), and right LD (p=0.01;

ε²=0.05) with small to moderate effect sizes (

Table 4). The post hoc comparisons showed significantly higher left SA activation in standing vs seated (W=-4.57; p<0.001) and kneeling vs seated (W=-4.59; p<0.001). However, no significant differences were found between standing and kneeling (p = 0.998).

Post hoc analysis for the right LD found higher significant activation in vs seated vs kneeling (W=2.86; p<0.05). No other significant pairwise comparison differences were found for right LD nor right SA, or left LD across positions.

3. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the muscle activity of SA and LD between six pairs of HE performed in closed and open kinetic chains positions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze sEMG and LD activation across diverse HE positions. Additionally, no previous studies aimed to assess differences between HE in closed vs open kinetic chains. Our findings support the initial hypothesis that HE performed in a closed kinetic chain elicits greater muscle activity than open-chain positions, especially for the left LD. We also found differences in neuromuscular activity of SA and LD concerning body position and moderate levels of SA activation across analyzed positions, while LD muscle recruitment remained low.

Previous studies have analyzed shoulder and trunk neuromuscular recruitment (i.e. infraspinatus, deltoids, serratus anterior, trapezius, erector spinae, and external oblique) with diverse closed-kinetic chain exercises in a wall press which is similar to the standing HE exercise performed against the wall in our study [

15]. However, in HE specific breathing maneuvers are added to the body position, which could result in differences in muscle activation. The sEMG data collection was done during the abdominal vacuum maneuver of HE which is performed while keeping the thoracic cage high and ribs wide. Research has demonstrated that LD muscle recruitment rises with inspiratory load and pressure generated [

18]. Inspiratory muscle fatigue affects the activity of the LD [

27] and the SA [

19]. While the LD is active during a deep inspiration (inspiratory volume close to maximum vital capacity), it also assists in keeping the chest high [

18]. The LD muscle activation during all HE positions in our study was less than 21% of MVIC. These data suggest that the LD acts as an accessory inspiratory muscle and periscapular stabilizer rather than a primary mover. Similarly, Hardwick et al. [

17] found minimal LD activity during a wall press exercise in a standing position with forearms against the wall with 90 degrees of humeral elevation.

The SA showed a higher percentage of activation than the LD for all HE positions. SA percentage of MVIC was characterized by moderate activation levels with higher neuromuscular recruitment in the closed-kinetic chain for the left side. Hardwick et al. [

17] found significant differences in SA activation when a wall-press exercise was performed with a humeral elevation higher than 90 degrees as compared to 90 degrees elevation. Digiovani et al. [

26] noted that moderate activation levels (21% - 40%) of MVIC could be adequate for early-phase neuromuscular training in a rehabilitation context.

The standing vs kneeling comparison did not reveal significant differences in SA or LD activation. The sEMG comparison for SA and LD between different positions revealed significant differences for the left SA in the kneeling positions compared to the seated position, and for the right LD in the seated position compared to the kneeling position. While SA muscle activation was greater in the standing and kneeling positions compared to seated, the seated position elicited the highest right LD activation in compared to standing or kneeling. Machado et al. [

10] reported higher levels of SA activation in the standing and seating HE positions when compared to the supine HE positions in a group of healthy adult females.

Previous sEMG studies with HE has primarily focused on the pelvic floor and anterior abdominal muscles assessed in the supine, quadruped, prone plank, and standing positions [

2,

12,

28]. In a group of healthy adult females, Ithamar et al. [

12] used sEMG to evaluate abdominal wall and pelvic floor musculature activation during HE performed in the standing, quadruped, and supine positions. This study found significant differences between selected body positions, specifically in the standing position compared to supine and Quiroz et al. [

28] compared the sEMG activity of the rectus abdominis, transverse, and external oblique muscles during a prone plank exercise versus a prone plank exercise performed with the HE is breathing technique. They reported that the addition of HE breathing to the prone plank exercise activated the transverse abdominus, internal oblique, and external oblique muscles to a greater degree than the traditional prone plank while activation of the rectus abdominis activity was reduced [

28]. Of interest, a voluntary abdominal contraction performed during closed kinetic chain exercises has been shown to activate in greater proportion to the SA [

29]. The SA and LD, through costal attachments, are interdigitated to costal attachments of the external oblique abdominis LD [6, 30]. The superficial lamina of the thoracolumbar fascia is derived in large part from the aponeurosis of the LD [

30]. The previously demonstrated activation of the external oblique during HE [

12] could be a contributory mechanism for the SA and LD activation levels described in our study.

Our sample consisted of healthy adults with previous experience in the HE technique. This data should not be extrapolated to other age groups or those with medical conditions including shoulder pathologies. Future studies analyzing muscle activation of HE in specific groups including athletes or adults suffering from shoulder dysfunction or lumbar pain are warranted. Additionally, sEMG was analyzed during isometric positions which are commonly practiced in HE programs and generate a more reliable sEMG measurement. However, this limits the generalization of results to dynamic HE or other exercises of a similar nature. Also, only two back muscle groups were analyzed. Due to sample size, sex-difference comparisons were not made. Questions remained unanswered about the neuromuscular role of other periscapular musculature (i.e. trapezius inferior, superior) or accessory breathing musculature such as external intercostalis during HE. Future studies analyzing clinical populations such as those with scapular dyskinesis, shoulder impingement, or postural dysfunction are warranted. Additionally, sEMG was analyzed only during isometric positions, which is how HE is commonly practiced, and to generate a more reliable sEMG measurement. However, this limits the generalization of results, which may not reflect dynamic or functional exercises of a similar nature. Additional studies using real-time dynamic analysis could complement our findings. Also, only two back muscle groups were analyzed. Questions remained unanswered about the neuromuscular role of other periscapular musculature (i.e., trapezius inferior, superior) or accessory breathing musculature such as external intercostalis during HE. Future studies should evaluate EMG activation of back and shoulder musculature during distinct positions such as quadruped, supine, standing, and in stable and unstable positions.

This study was designed to measure levels of activation of SA and LD muscles during open and closed kinetic chain HE positions. Our findings reveal that HE performed with a closed-kinetic chain elicits greater muscle activity of the SA than open-chain exercises. The level of activation of SA during closed kinetic chain HE performed on the wall is moderate, while LD is low. Body position influenced sEMG activation, with the standing and kneeling positions enabling better activation for the SA and the seated position for the LD. This information can better aid therapists and practitioners in the exercise selection and progression of HE positions in closed-chain for scapular stabilization rehabilitation. Closed kinetic chain HE could be useful for early phases of rehabilitation, for patients whose pain or limited range of motion might not tolerate high-load scapular exercises. Additional research is warranted to determine the impact and usefulness of HE in clinical conditions with periscapular conditions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Design

This study was a prospective cross-sectional study that used a repeated-measures, within-subject design. We used the checklist for reporting and critically appraising studies using EMG (CEDE-Check) as a comprehensive checklist for reporting the sEMG methodology used in this study [

20] (see supplementary file 1).

4.2. Participants

A priori power analysis using G*Power (v3.1) with effect size d=0.5, α=0.05, and power=0.8 for a repeated measures design indicated a sample size of 24; thus, 25 participants were recruited. Twenty-five healthy adults (4 males and 21 females) participated in the present study. The study was conducted between December 2023 and February 2024. Recruitment of participants was made through physical therapy clinics from the Girona area (Spain) and by word of mouth. Inclusion criteria to participate in this study were: a) to be between 20 to 60 years of age; b) to have a minimum practice experience with HE of 12 weeks and; c) to not have any musculoskeletal pain and or dysfunctions in the shoulder and back region. The exclusion criteria were: a) any contraindication to performing the HE programs (hypertension, pregnancy, pulmonary obstructive dysfunctions) or b) any injury that did not allow the completion of the HE. Before commencing the study, the participants were informed about data collection procedures and the intervention program. The study was approved by the Research Ethics and Biosafety Committee of the University of Girona (project number: CEBRU0046-23). All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

4.3. Procedures

Data were collected in a physical therapy clinic. Before the testing session, height and body mass were measured using a precision stadiometer and balance (SECA 700). Participants underwent a familiarization session with the same evaluator to ensure understanding and execution of the HE intervention. Participants also were introduced to sEMG before all testing. The abbreviated format of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used to characterize participants' physical activity levels [

21]. The intensity combined with the time spent on each activity was used to calculate the IPAQ summative score (MET min/week). The level of physical activity classification followed the criteria available in Craig et al. [

21] which classifies physical activity levels as low, moderate, and high.

During the second session testing was performed. Electromyographic data was collected bilaterally from the SA and LD using the mDurance® system (mDurance Solutions SL, Granada, Spain) previously validated for this purpose [

22]. This is a portable, wireless, and lightweight (30-gram) sEMG system that consists of a bipolar sEMG Shimmer3 sensor composed of two sEMG channels (Realtime Technologies Ltd, Dublin, Ireland). The two sEMG channels in each Shimmer sensor have a sampling rate of 1,024 Hz. Shimmer uses an 8.4 kHz bandwidth, a 24-bit EMG signal resolution, and an overall 100–10,000 V/V amplification. Pre-gelled Ag/AgCl electrodes with a 10 mm diameter and a 20 mm interelectrode spacing were utilized [

22]. A total of 6 solid hydrogel adhesive electrodes of 30 mm size (DORMO®, Telic Group SL, Spain) and a band were used to hold the sensors. Two electrodes were used for each muscle and side. The electromyographic data was collected via Bluetooth from the shimmer unit to the mDurance (Android) mobile application using a digital tablet (Samsung) and a cloud service that stores the sEMG signals. The Raw electromyographic data was digitally filtered using a fourth-order Butterworth bandpass bandwidth filter with a cut-off frequency at 20–450 Hz, and the signal was smoothed using a window size of 0.025 s root mean square to represent the amplitude values of the EMG [

22].

Participants were asked to bring comfortable clothing that did not interfere with the placement of the electrodes. sEMG testing followed the recommendations for the Surface Electromyography for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles (SENIAM) guidelines [

23]. The skin was shaved, scrubbed, and cleaned with 96º isopropyl alcohol (Micraderm, Spain), and allowed to dry to diminish skin impedance. The same evaluator tested all participants and was blinded to data analysis. Participants were seated with the shoulder in 90-degree abduction for bilateral electrode placement. For the SA, electrodes were positioned vertically along the axillary midline at the level of the sixth and eighth ribs in the direction of the muscle fiber, maintaining a distance of 2 cm between electrodes for adequate signal capture. For the LD, electrodes were placed lateral to thoracic vertebra 9, below the lower tip of the scapula, and over the muscular belly. The reference or ground electrode was placed on a superficial bony surface and distal to the electrodes such as the iliac crest.

To calculate the maximal sEMG activity of each muscle and normalize the amplitude of the signal during HE, participants performed three maximal voluntary isometric contractions (MVIC) against manual resistance. Participants underwent 5 minutes of familiarization with the MVIC assessment before testing. For the SA, the participant was placed in a seated position with scapular rotation upwards with the shoulder at 125º. For the LD the participant was positioned in the prone position and an upward arm extension was requested. The evaluator applied manual resistance against the movement for 5 seconds for 3 repetitions with a 30-second rest between repetitions for each muscle group. Verbal encouragement was provided, such as “push as hard as you can” and “keep pushing”. The mean value of muscle activity (microvolts) was calculated over 10 seconds and the average of the times in the different muscles and participants was used as the value of the analysis [

24].

4.4. Intervention

The HE was standardized and supervised by the same evaluator who had 7 years of experience teaching HE. Participants were barefoot and wore comfortable clothes. The HE was performed respecting the postural fundamentals described elsewhere [

3,

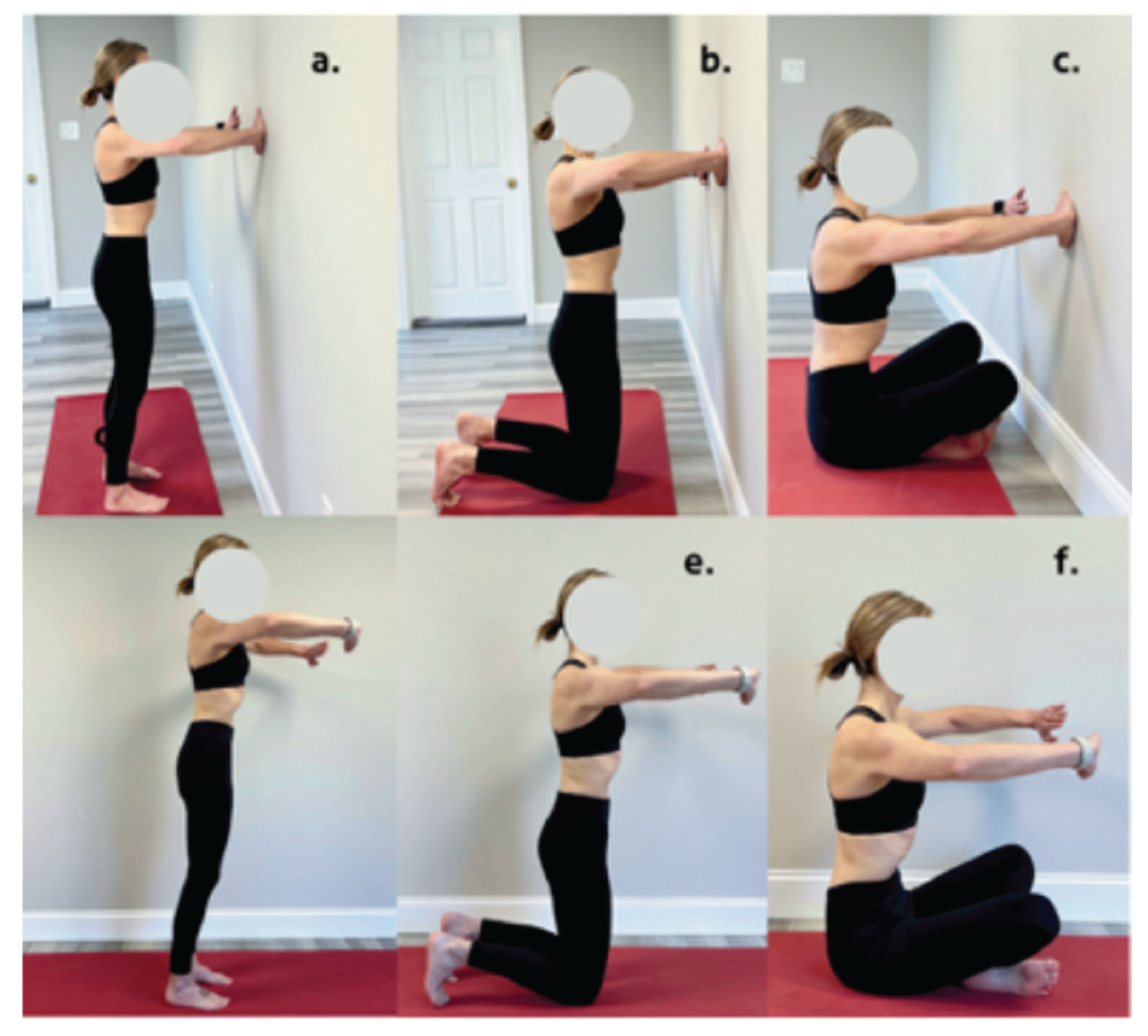

5]: (a) neutral pelvis and axial elongation; (b) dorsiflexion of the ankles for sitting, and kneeling positions; (c) knee bending; (d) scapular adduction of the shoulder girdle muscles; (e) three breathing cycles with lateral rib breathing and slow, deep exhalations (maximum inhalation and exhalation); (f) maintenance of breathing after expansion of the rib cage (abdominal vacuum phase). Instructions based on the postural fundamentals were provided during each position as a means of feedback and encouragement. The protocol consisted of 6 distinct positions: a) standing open-chain; b) kneeling open-chain; c) sitting open-chain; d) standing closed-chain; e) kneeling closed-chain; and f) sitting closed-chain. Exercise order was randomized for each participant and positions were all performed on a mat or against the wall during closed kinetic chain positions.

Figure 1 illustrates the analyzed positions. The selection of HE positions was based on their beginner level and on being common positions utilized in the previous literature [

1]. Additionally, isometric arm and body positions were selected to minimize possible variations at the electrode site. All HE arm positions were maintained at 90 degrees of shoulder elevation at the scapular plane with the same degree of elbow flexion for all positions. The standardization of the body stance of the closed-kinetic chain HE was based on the distance of the arm extended at 90 degrees of elevation. 3 repetitions of each exercise were performed with 3 minutes of recovery between exercises. Breathing was cued with the following instructions: inhale for 2 seconds, exhale for 4 seconds, breath-hold while performing an abdominal vacuum for 10 seconds.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive characteristics were calculated, and results were presented as means and standard deviations (SD) and medians. Normality was tested for all the variables using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Levene´s test was used to verify the homogeneity of the variables analyzed. The effect of the chains (open-chain vs closed-chain) was analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test and a rank biserial correlation was used to determine the effect size and interpreted as follows: small >0.1 to 0.3; medium >0.3 to 0.50 and large >0.50 to 1.00. The interaction between exercises was also analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis followed by Bonferroni post-hoc correction for each variable. Epsilon-squared (ε

2) was used to determine the magnitude of the effect and interpreted based on the recommendations of Field [

25]: very small <0.01; small ≥0.01 to <0.06; medium ≥0.06 to <0.14 and large ≥0.14. Statistical significance was set up at p≤0.05. All statistical tests were performed using JASP (JASP Team, version 0.17.3 [Computer Software], Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Additionally, we characterized the % of MVIC as very high (≥60%), high (41%–60%), moderate (21%–40%), or low (0%–20%) following previous research [

26].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: CEDE Checklist for reporting and critically appraising studies using EMG (CEDE-check).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.H.R. and T.R.R.; methodology, E.H.R. and T.R.R; formal analysis, D.A.A.; data curation, D.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R.R.; writing—review and editing, E.H.R. and T.R.R, supervision, D.C.O., C.T.M. and T.R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics and Biosafety Committee of the University of Girona (project number: CEBRU0046-23; November 27,2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request by the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all participants in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EMG |

Electromyography |

| HE |

Hypopressive exercise |

| LD |

Latissimus dorsi |

| MVIC |

Maximal voluntary isometric contraction |

| SA |

Serratus anterior |

| sEMG |

Surface electromyography |

References

- Hernández Rovira E, Rebullido TR, Cañabate D, Torrents Martí C. What Is Known from the Existing Literature about Hypopressive Exercise? A PAGER-Compliant Scoping Review. J Integr Complement Med. Published online April 17, 2024. j. [CrossRef]

- Navarro Brazález B, Sánchez Sánchez B, Prieto Gómez V, De La Villa Polo P, McLean L, Torres Lacomba M. Pelvic floor and abdominal muscle responses during hypopressive exercises in women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39(2):793-803. [CrossRef]

- Bellido-Fernández L, Jiménez-Rejano JJ, Chillón-Martínez R, Lorenzo-Muñoz A, Pinero-Pinto E, Rebollo-Salas M. Clinical relevance of massage therapy and abdominal hypopressive gymnastics on chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(16):4233-4240. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-López I, Peña-Otero D, Eguillor-Mutiloa M, Bravo-Llatas C, Atín-Arratibel MDLÁ. Manual therapy on the diaphragm is beneficial in reducing pain and improving shoulder mobility in subjects with rotator cuff injury: A randomized trial. Int J Osteopath Med. 2023;50:100682. [CrossRef]

- Rebullido TR, Chulvi-Medrano I. The Abdominal Vacuum Technique for Bodybuilding. Strength Cond J. 2020;42(5):116-120. [CrossRef]

- Neumann DA, Camargo PR. Kinesiologic considerations for targeting activation of scapulothoracic muscles - part 1: serratus anterior. Braz J Phys Ther. 2019;23(6):459-466. [CrossRef]

- Martin RM, Fish DE. Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Park SY, Yoo WG. Activation of the serratus anterior and upper trapezius in a population with winged and tipped scapulae during push-up-plus and diagonal shoulder-elevation. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2015;28(1):7-12. [CrossRef]

- Lung K, St Lucia K, Lui F. Anatomy, Thorax, Serratus Anterior Muscles. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed March 2, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531457/.

- Machado V, Dornelas De Andrade A, Rattes C, et al. Effects of abdominal hypopressive gymnastics in the volume distribution of chest wall and the electromyographic activity of the respiratory muscles. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:e322-e323. [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Campos D, Sanchez-Jorge S, Terrón-Manrique P, et al. The Main Role of Diaphragm Muscle as a Mechanism of Hypopressive Abdominal Gymnastics to Improve Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):4983. [CrossRef]

- Ithamar L, De Moura Filho AG, Benedetti Rodrigues MA, et al. Abdominal and pelvic floor electromyographic analysis during abdominal hypopressive gymnastics. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018;22(1):159-165. [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Rebolledo G, Morales-Verdugo J, Orozco-Chavez I, Habechian FAP, Padilla EL, De La Rosa FJB. Optimal activation ratio of the scapular muscles in closed kinetic chain shoulder exercises: A systematic review. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2021;34(1):3-16. [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Rebolledo G, Orozco-Chavez I, Morales-Verdugo J, Ramirez-Campillo R, Cools AMJ. Electromyographic analysis of the serratus anterior and upper trapezius in closed kinetic chain exercises performed on different unstable support surfaces: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13589. [CrossRef]

- Pozzi F, Plummer HA, Sanchez N, Lee Y, Michener LA. Electromyography activation of shoulder and trunk muscles is greater during closed chain compared to open chain exercises. J Electromyogr Kinesiol Off J Int Soc Electrophysiol Kinesiol. 2022;62:102306. [CrossRef]

- Gioftsos G, Arvanitidis M, Tsimouris D, et al. EMG activity of the serratus anterior and trapezius muscles during the different phases of the push-up plus exercise on different support surfaces and different hand positions. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28(7):2114-2118. [CrossRef]

- Hardwick DH, Beebe JA, McDonnell MK, Lang CE. A comparison of serratus anterior muscle activation during a wall slide exercise and other traditional exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(12):903-910. [CrossRef]

- Watson AHD, Williams C, James BV. Activity patterns in latissimus dorsi and sternocleidomastoid in classical singers. J Voice Off J Voice Found. 2012;26(3):e95-e105. [CrossRef]

- Lomax M, Tasker L, Bostanci O. An electromyographic evaluation of dual role breathing and upper body muscles in response to front crawl swimming. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(5):e472-478. [CrossRef]

- Besomi M, Devecchi V, Falla D, et al. Consensus for experimental design in electromyography (CEDE) project: Checklist for reporting and critically appraising studies using EMG (CEDE-Check). J Electromyogr Kinesiol Off J Int Soc Electrophysiol Kinesiol. 2024;76:102874. [CrossRef]

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381-1395. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Molina A, Ruiz-Malagón EJ, Carrillo-Pérez F, et al. Validation of mDurance, A Wearable Surface Electromyography System for Muscle Activity Assessment. Front Physiol. 2020;11:606287. [CrossRef]

- Hermens HJ, Freriks B, Disselhorst-Klug C, Rau G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J Electromyogr Kinesiol Off J Int Soc Electrophysiol Kinesiol. 2000;10(5):361-374. [CrossRef]

- Ekstrom RA, Soderberg GL, Donatelli RA. Normalization procedures using maximum voluntary isometric contractions for the serratus anterior and trapezius muscles during surface EMG analysis. J Electromyogr Kinesiol Off J Int Soc Electrophysiol Kinesiol. 2005;15(4):418-428. [CrossRef]

- Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 4th ed. London: Sage Publications; 2013.

- Digiovine NM, Jobe FW, Pink M, Perry J. An electromyographic analysis of the upper extremity in pitching. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1(1):15-25. [CrossRef]

- Lomax M, Tasker L, Bostanci O. Inspiratory muscle fatigue affects latissimus dorsi but not pectoralis major activity during arms only front crawl sprinting. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(8):2262-2269. [CrossRef]

- Quiroz Sandoval GA, Tabilo N, Bahamondes C, Bralic P. Surface electromyography comparison of the abdominal hypopressive gymnastics against the prone bridge exercise. Rev Andal Med Deporte. 2019;12(3):243-246. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Scatolin R, Hotta GH, Cools AM, Custodio GAP, De Oliveira AS. Effect of conscious abdominal contraction on the activation of periscapular muscles in individuals with subacromial pain syndrome. Clin Biomech. 2021;84:105349. [CrossRef]

- Willard FH, Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Danneels L, Schleip R. The thoracolumbar fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerations. J Anat. 2012;221(6):507-536. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).