1. Introduction

The interplay between spinal alignment and the multifaceted nature of low back pain (LBP) underscores the fundamental importance of maintaining optimal spinal posture. Based on seminal studies, the narrative emphasises how the curvature of the thoracic and lumbar regions is shaped by the biomechanical properties of the spinal ligaments as well as the synergistic and antagonistic forces of the surrounding musculature [

1]. Deviations from ideal spinal curvatures, manifested as increased lordosis or marked kyphotic postures, are not only a precursor to chronic LBP, but are also understood to disrupt normal lumbar motion patterns [

2]. These changes can trigger conditions such as thoracic flexion syndrome and complicate shoulder mechanics [

3]. This can lead to problems such as shoulder flexion dysfunction [

4]. In response to these challenges, the strategic strengthening of the thoracic and lumbar spine's extensor musculature emerges as a pivotal intervention. This approved approach aims to correct excessive thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis, reduce spinal disorders and prevent subsequent complications [

5]. The essence of this therapeutic strategy rests on identifying and implementing exercises that effectively bolster these critical spinal regions.

Despite the dominance of subjective assessments in existing literature, which evaluate the efficacy of exercises in reducing pain, enhancing lumbar muscle strength, and alleviating disability, there remains a notable scarcity of studies leveraging objective metrics for these evaluations. investigates the positive effects of specific exercise methods, such as Tai Chi and Pilates, on individuals suffering from chronic LBP, highlighting notable improvements in pain, function and kinesiophobia [

6]. However, objective studies demonstrating decreased lumbar muscle activation on both symptomatic and asymptomatic sides in patients with chronic LBP are rare [

7] .The criticality of targeted muscle activation is brought to the fore by Park et al. (2015) and Kim et al. (2015), who demonstrated that exercises like the prone trunk extension and the abdominal drawing-in maneuver during prone hip extension significantly modulate the activity of the thoracic and lumbar erector spinae muscles, as well as the gluteus maximus [

8,

9]. Similarly, a study of superman exercise revealed no significant difference in activity levels of the longissimus and iliocostalis muscles between stable and unstable modalities [

10]. Building on this foundation, the present study aims to delve deeper into the effects of the abdominal drawing-in maneuver on the activation of thoracic and lumbar erector spinae muscles throughout a variety of low back exercises in individuals with non-specific low back pain. This inquiry is twofold: firstly, to systematically assess the efficacy of different low back exercises in conjunction with the abdominal drawing-in maneuver for optimizing the engagement of specific muscle groups, and secondly, to distill actionable insights that could refine therapeutic approaches to ameliorating LBP. The hypothesis driving this research postulates that the abdominal drawing-in maneuver, when integrated into selected low back exercises, will significantly enhance the activation of the thoracic and lumbar erector spinae muscles, thereby contributing to improved spinal alignment and reduction in LBP symptoms among individuals with non-specific low back pain.

2. Materials and Methods

The sample size for this investigation was calculated using a power analysis. Based on the results of a pilot study involving 10 subjects, a sample size of 40 subjects was required to provide an effect size of 0.40 (calculated by partial η2 of 0.20), an alpha level of 0.05, and a power of 0 .80. Twenty subjects with non-spesific low back pain were recruited to accommodate the calculated sample size. The inclusion criteria for the subjects were as follows: 1) current pain at lumbar pain. 2) not participating in any regular flexibility or strengthening exercise programs. 3) no history of surgery at lumbar spine.4) had a kyphosis angle of 20-45 degrees. 5) had a lumbar lordosis angle between 20-40 degrees. Participants were excluded according to the following criteria: acute low back pain, had a scoliosis, recent spinal surgery, and previous whiplash injury. This study was approved by the University of Health Sciences Scientific Research Ethic Board and all procedures were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov Protocol Registration and Results System website (clinical trial number NCT05748509). All participants provided written informed consent before the data collection began.

2.1 EMG Recording and Data Analysis

EMG data were collected using Noraxon Ultium EMG sensor system (Noraxon USA, Inc., Scottsdale, Arizona- sampling frequency of 4000 Hz per channel; gain: 1000 (signal to noise ratio;1 μV RMS); common mode rejection rate (CMRR): -100 dB; input impedance >100 mΩ.). Any hair on the skin was first removed, and then the area was cleansed with an alcohol swab before electrodes were connected to detect EMG signals [

11]. The electrodes were positioned bilaterally on the iliocostalis lumborum pars lumborum (right ICL and left ICL) at the L3 level, midway between the lateral-most palpable border of the erector spinae and a vertical line through the posterosuperior iliac spine; on the longissimus thoracis (right LT and left LT) at the T9 level, midway between a line through the spinous process and a vertical line through the posterosuperior iliac spine, located approximately 5 cm laterally; and on the iliocostalis lumborum pars thoracis (right ICT and left ICT) at the T10 level, midway between the lateral-most palpable border of the erector spinae and a vertical line through the posterosuperior iliac spine [

8]. The sample rate was set to 2000 Hz. Two filters were applied, including a band-pass filtered from 10 to 500 Hz using a first-order high-passand fourth-order low-pass Butterworth filter to remove unacceptable artifacts and a notch filter (60 Hz) to eliminate noise. A moving 100-ms window was used to calculate root mean square (RMS) values. The Noraxon MyoResearch XP program was used to process the data (version 3.16; Noraxon Inc, Scottsdale, AZ, USA). The data for each trial were expressed as a percentage of the calculated mean RMS of the MVIC (%MVIC), and the mean %MVIC of 3 trials was used for analysis [

12].

2.2 Procedures

Each muscle underwent a maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC), and the EMG signal amplitude was recorded, in order to normalize the EMG data. The test postures were similar to those in books on manual muscle testing that physical therapists frequently employ, except in the case of the back muscles, more manual resistance was used. The maximum resistance was applied by progressively increasing the manual pressure, which was then applied and held for 5 seconds. With a 30-second break in between each contraction, each muscle test was performed three times. Also, by examining the EMG amplitudes during the manual muscle tests, proper electrode placement was validated. When performing the MVIC for the erector spina muscles, the lower extremities were stabilized while the prone trunk was extended to its full range of motion and resistance was applied in the upper thoracic area [

8,

13].

The training session, which lasted about 30 minutes, acquainted the subjects with using an abdominal drawing-in maneuver (ADIM) before the assessment. Each participant used a pressure biofeedback device to practice abdominal hollowing while being informed of the function and pressure monitoring system of the device (Chattanooga Group, Hixson, TN). The EMG activity was measured during lumbal extension exercises, performed with and without doing an ADIM. Each repeat of the exercises was kept in isometric position for 10 seconds. A metronome was used to control the time and speed of movement. The exercises were performed at a comfortable speed and consisted of a concentric phase, isometric phase, and eccentric phase. The exercises were carried out in a random order. In order to lessen the effects of tiredness, rest intervals of 30 seconds were permitted between each exercise repeat, and a minute-long break was provided between workouts. Each subject, in random order, performed the lumbal extension exercises with and without doing an ADIM [

9,

12].

2.3 Exercise Procedures

2.3.1. Prone Trunk Extension Exercise

Participants were asked to extend their trunks continuously while resting on their backs while touching a horizontal bar that was positioned 10 cm above the plinth. Each subject maintained a steady tempo throughout trunk extension thanks to the auditory cues given by an electronic metronome. In order to achieve lumbar extension during the ascent phase and return to neutral during the descend phase, participants were given specific instructions. Each participant had two different forms of fixation for trunk extension: one at the popliteal fossa of the knee and the posterior superior iliac spine of the pelvic region, and the other at the thoracolumbar junction in addition to the first fixation [

14].

2.3.2. Superman Exercise

Participants begin this hyperextension exercise in a lying-prone position with neutral spine curvatures. Throughout the whole exercise session, hands and arms were held at the level of the temporal bone with the feet flat on the floor, the legs extended, and the arms flexed. Participants had been told to perform lumbar hypertension (about 20 degrees) during the ascent phase and return to neutral (0 degrees) during the descent phase [

10].

2.3.3. Unstable Superman Exercise

The same steps as the Superman exercise are included here, however the range of motion is used in unstable conditions: Assuring that the participant's feet were shoulder-width apart, flat against a wall for support, and legs completely extended, a Swiss Ball was placed under the participant's umbilicus. Throughout the exercise, hands were held at the level of the temporal bone with arms extended [

10].

All lumbal extension workouts included the ADIM, which was carried out under the

supervision of a pressure biofeedback device (PBFU;Chattanooga Group, Hixson, TN, USA). In the prone position, the PBFU was placed beneath the lower abdomen of the participants. As soon as the

metronome began, individuals started the ADIM with the pressure set to 70 mmHg. They reduced the pressure to 60 mmHg and kept it there. Data collected within pressure changes of +5 mmHg were used for the statistical analysis [

12].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analysis were conducted using SPSS (ver. 26.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to confirm that the data were distributed normally. Four separate 2 × 2 analyses of variance determined main and interaction effects for each tested muscle. The within-subject factor was condition (two levels: with and without an ADIM). A statistical significance level was set at 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 40 participants with non-specific low back pain were included in this study. The percentage of female patients was 73.3% (n=11). The average age and BMI of patients were 21.42±1.07 years and 20.65±2.08 kg/m2, respectively. The right side was dominant in 80% (n=32) of the participants.

There was a significant main effect for condition for the EMG signal amplitude of the iliocostalis lumborum pars thoracis (F1,14 = 117.142, p<0.001), iliocostalis lumborum pars lumborum (F1,14 = 82.328, p<0.001), and longissimus thoracis (F1,14 = 69.852, p = 0.008).

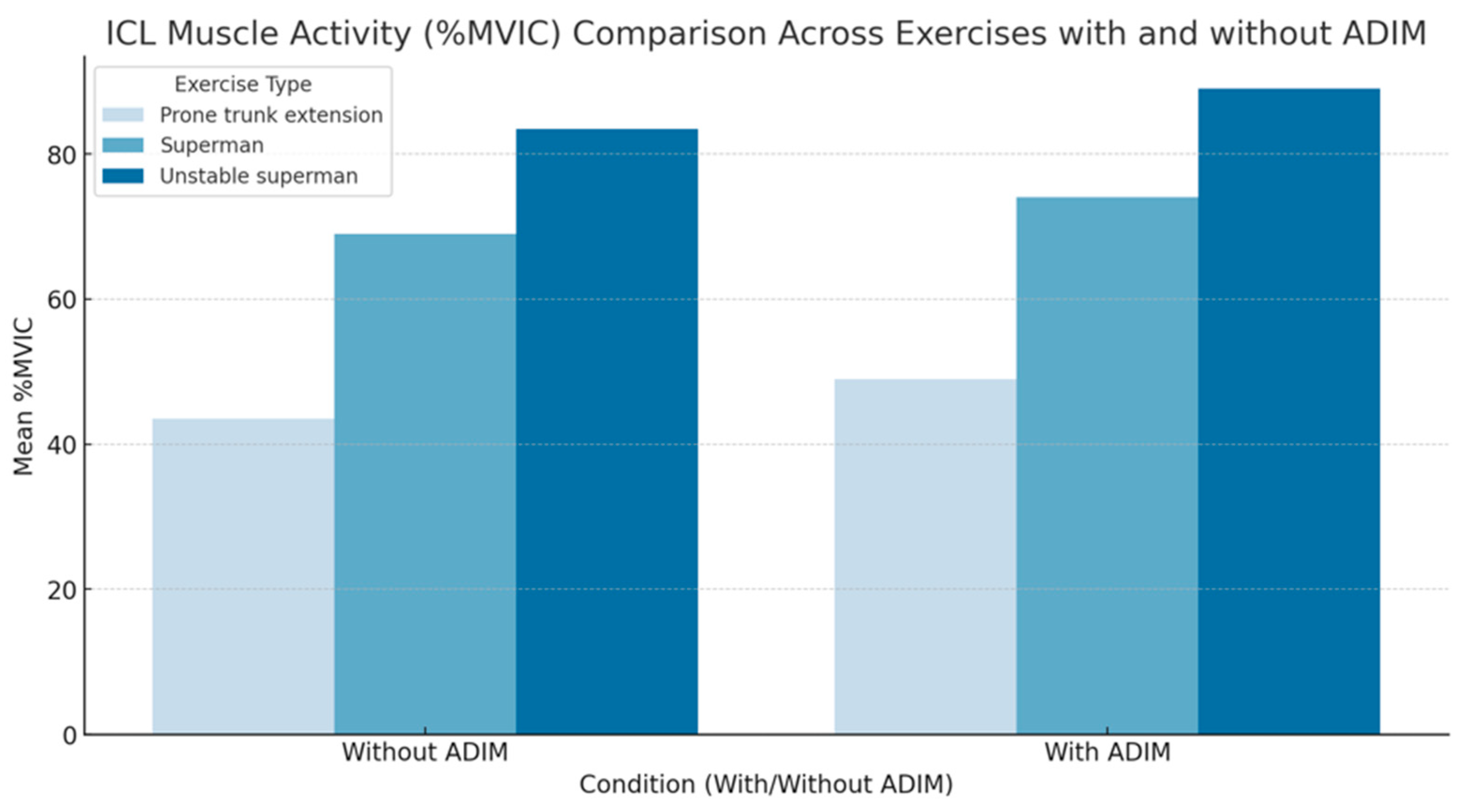

The right ICL and left ICL activity was a significant main effect of the exercise type (F

1,14= 82.69; p<0.001; partial η

2=0.88, respectively) and ADIM exercises (F

1,14= 114.23; p<0.001; partial η

2=0.92). For prone trunk extension, superman and unstabile superman exercises performed with an ADIM, the EMG signal amplitude decreased significantly in the right ICL (mean difference: 14.06;17.34;20.02, respectively;

Figure 1) and left ICL (mean difference: 13.06;18.21;21.32, respectively;

Figure 1). In addition, the muscle activity of both ICL were greater in the unstable superman exercise than in the superman exercise and prone trunk extension exercise (p<0.01;

Figure 1).

The right ICT and left ICT activity was a significant main effect of the exercise type (F

1,14= 100.69; p<0.001; partial η

2=0.90, respectively) and ADIM exercises (F

1,14= 117.13; p<0.001; partial η

2=1.13). For prone trunk extension, superman and unstabile superman exercises performed with an ADIM, the EMG signal amplitude increased significantly in both the ICT (mean difference: 6.45;7.32;8.89, respectively;

Figure 2). In addition, the muscle activity of both ICT were greater in the unstabile superman exercise than in the superman exercise and prone trunk extension exercise (p<0.01;

Figure 2).

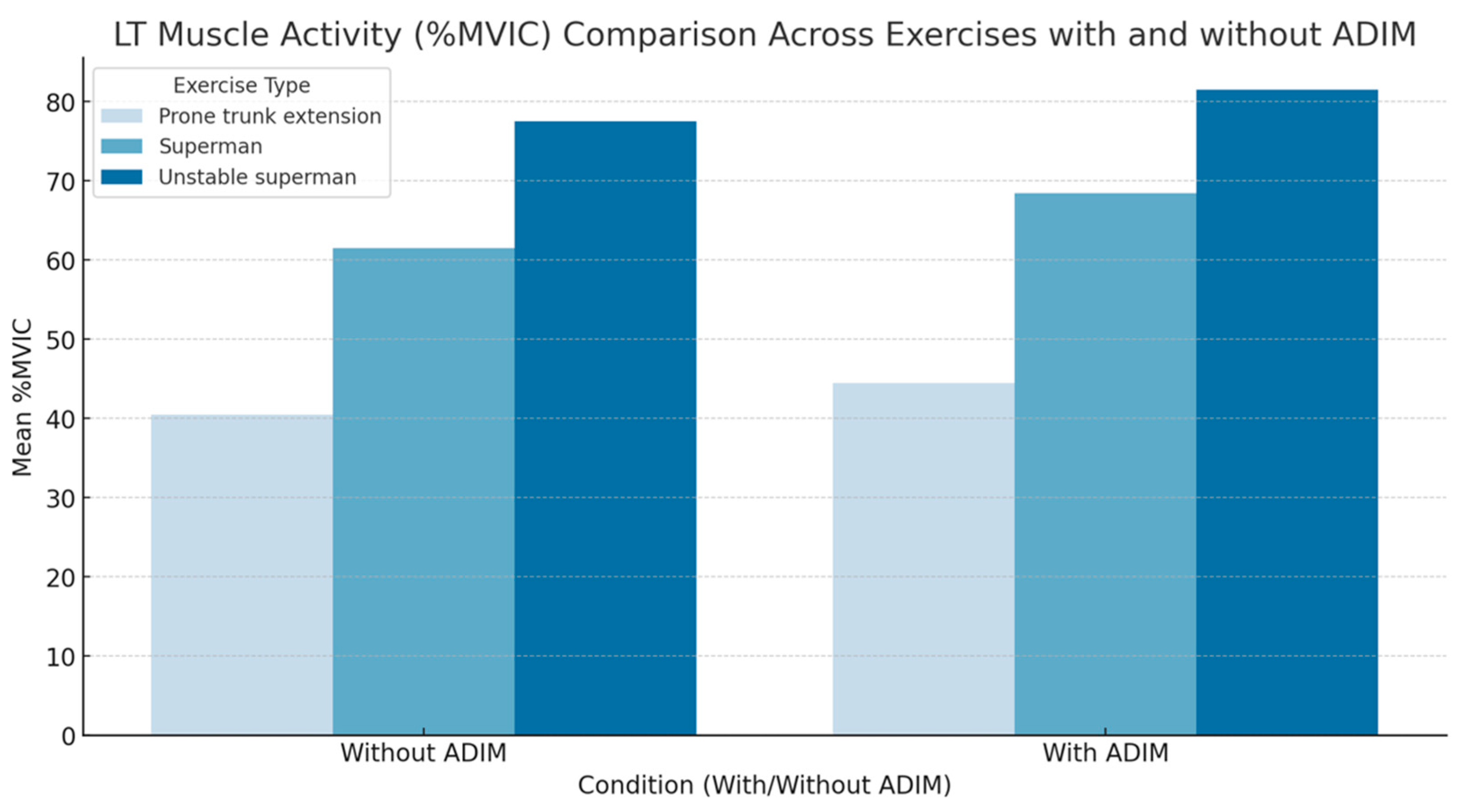

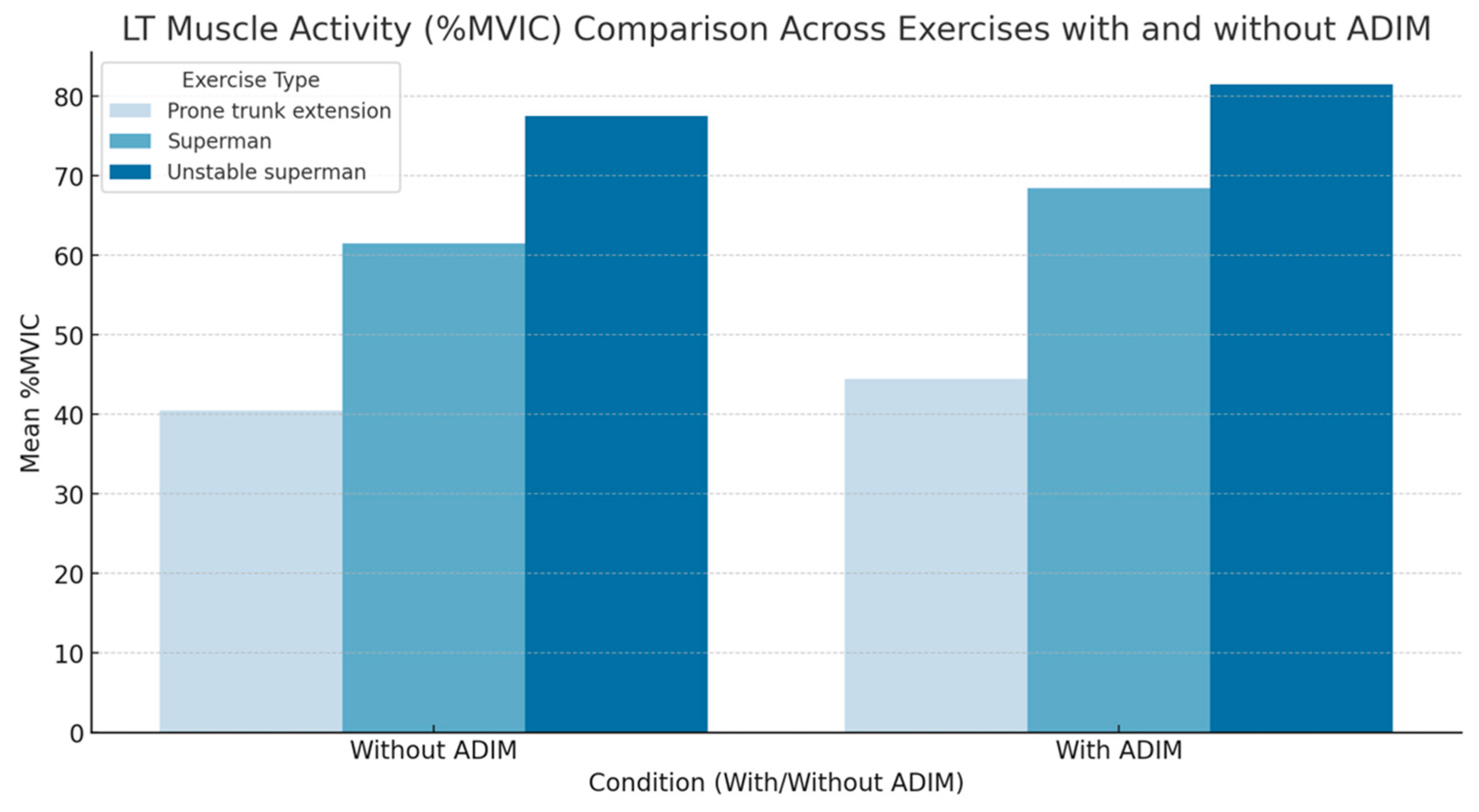

The right LT and left LT activity was a significant main effect of the exercise type (F

1,14= 62.69; p<0.001; partial η

2=0.81, respectively) and ADIM exercises (F

1,14= 74.88; p<0.001; partial η

2=0.84). For prone trunk extension, superman and unstabile superman exercises performed with an ADIM, the EMG signal amplitude increased significantly in both the LT LT (mean difference: 9.37;10.43;12.13, respectively;

Figure 3). In addition, the muscle activity of both LT were greater in the unstabile superman exercise than in the superman exercise and prone trunk extension exercise (p<0.01;

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

This comprehensive study provides an in-depth analysis of the effects of the abdominal drawing-in maneuver (ADIM) on electromyographic (EMG) activity during various exercises specifically tailored for individuals with non-specific low back pain. Through meticulous EMG analysis, we observed substantial modulation in the activation patterns of essential spinal stabilizing muscles, including the iliocostalis lumborum pars thoracis (ILCT), iliocostalis lumborum pars lumborum (ILCL), and longissimus thoracis (LT). These findings underscore ADIM's role as an effective tool for altering muscle recruitment during exercises, which holds promise for both therapeutic and preventive strategies aimed at managing back pain.

Our results demonstrated significant increases in EMG signal amplitude in the ILCT and LT muscles, with ADIM exhibiting variable effects on the ILCL across different exercises, including prone trunk extension, superman, and the unstable superman. Notably, the unstable superman exercise resulted in the greatest increase in muscle activation, suggesting that the combination of ADIM with exercises on unstable platforms may offer unique benefits for spinal muscle conditioning and rehabilitation. This increased muscle engagement in unstable conditions may be indicative of a heightened neuromuscular response, which could play a crucial role in enhancing stability, core strength, and endurance, all of which are critical components in managing and preventing low back pain.

The clinical implications of these findings are significant. ADIM’s ability to selectively activate key spinal stabilizers supports its integration into rehabilitation programs focused on improving core stability and strength. The enhanced muscle activity during unstable exercises reinforces the potential benefit of combining ADIM with instability in exercise protocols. Such an approach may provide functional advantages for patients who require increased proprioceptive feedback and dynamic stability. In cases of chronic or recurrent low back pain, the integration of ADIM into unstable exercises could foster a more resilient core, which is essential for maintaining stability and protecting against injury during daily activities. By targeting specific spinal stabilizers, ADIM not only contributes to core strength but also reinforces the body’s protective mechanisms, potentially reducing the risk of pain exacerbation and future injury.

This study builds upon and extends the existing literature. It corroborates the findings of Kim (2017), who highlighted ADIM’s efficacy in increasing thoracic extensor muscle activity while decreasing lumbar muscle activation [

15]. This variation in lumbar activation may be due to differences in electrode placement or the localized stabilization effect of ADIM in the thoracic region. Such findings are critical for clinicians, as they emphasize the importance of understanding regional differences when utilizing ADIM in rehabilitation. By tailoring ADIM-based exercises to focus on either thoracic or lumbar stability based on patient needs, clinicians can create more effective and customized treatment plans. For instance, exercises that enhance thoracic stability without overloading the lumbar region may be particularly beneficial for patients experiencing localized lumbar or thoracic discomfort, thereby improving rehabilitation outcomes.

Furthermore, this study uniquely explores the combined effects of ADIM and the unstable superman exercise, revealing significant changes in muscle activity patterns. This finding aligns with recommendations by Behm et al. (2005), which advocate for the use of unstable surfaces in core-strengthening exercises to increase neuromuscular activation and balance [

17]. When combined with ADIM, these exercises may amplify therapeutic outcomes by enhancing activation in spinal stabilizers, promoting core control, and improving balance. The proprioceptive feedback offered by instability, alongside ADIM’s targeted muscle activation, creates a functional approach to core strengthening, particularly valuable for patients in the early stages of rehabilitation. This dual approach may help develop body awareness, control, and stability, which are essential for daily movements and activities, as well as for progressing to more advanced exercise levels as recovery progresses.

Interestingly, the study also found that incorporating ADIM into superman exercises did not significantly affect muscle thickness but did reduce muscle fatigue, as noted in previous studies [

8,

16]. This reduction in muscle fatigue suggests that ADIM can enhance endurance and maintain prolonged muscle activation without inducing hypertrophy. This characteristic is advantageous for patients with chronic low back pain, who often need sustained support from spinal stabilizers during daily tasks that require prolonged muscle engagement. Reduced fatigue enables patients to maintain muscle activation over longer durations, potentially alleviating discomfort associated with static postures and prolonged activities, such as sitting or standing for extended periods. For individuals with chronic low back pain, ADIM could therefore play a critical role in improving posture, stability, and functional performance, supporting a more active lifestyle while minimizing pain and discomfort.

The fatigue-reducing effect of ADIM offers practical benefits for those struggling to sustain muscle activation during prolonged activities. By lowering fatigue, ADIM allows patients to maintain core stability during tasks that require extended muscle engagement. For patients with chronic low back pain, ADIM may improve their ability to perform essential daily tasks without experiencing muscle exhaustion, thus contributing to enhanced endurance, functional capacity, and overall quality of life. This effect may be particularly beneficial for patients less focused on muscle hypertrophy and more concerned with functional strength and stability, as it promotes spinal support without increasing muscle bulk, which can sometimes be counterproductive for those with certain spinal conditions.

While this study provides valuable insights, it also acknowledges certain limitations, particularly the participants’ lack of prior experience with ADIM. To improve the generalizability of these findings, future research should encompass a broader demographic, including individuals with varying levels of familiarity with ADIM, as recommended by Barbosa et al. (2018) [

18]. Examining a more diverse sample would enrich the study’s findings and reveal how experience with ADIM influences muscle activation, stability, and fatigue across different populations. Moreover, expanding the participant pool to include individuals with varying fitness levels and pain intensities could yield further insights into ADIM’s efficacy and adaptability in broader clinical and functional applications.

From a clinical standpoint, incorporating participants with diverse experience levels in future studies would allow for the development of more personalized and effective ADIM-based protocols. This individualized approach could account for patient familiarity and proficiency with ADIM, making it more accessible and beneficial to a wider range of patients, including those new to core stabilization techniques. Tailoring ADIM application based on experience and fitness levels could optimize its therapeutic benefits, making it a valuable addition to the repertoire of clinicians treating patients with non-specific low back pain.

In summary, this study offers a thorough evaluation of ADIM’s effects across different exercises, highlighting the importance of exercise stability and its influence on muscle activation outcomes. The findings support the strategic integration of ADIM into rehabilitation and training protocols, underscoring its promise as a tool to improve intervention effectiveness in non-specific low back pain. By focusing on stability and targeted muscle activation, ADIM offers potential benefits in terms of pain management, reducing pain intensity, and minimizing functional limitations in patients. This study advocates for continued exploration and application of ADIM in both clinical and athletic settings, aiming to improve outcomes for individuals suffering from low back pain through enhanced core stability, muscle endurance, and precise muscle activation. Future research should further explore ADIM’s applications across diverse populations and settings, aiming to validate and expand its utility, ultimately solidifying its role as an effective strategy in the management of non-specific low back pain.

5. Conclusions

This research provides compelling evidence on the effectiveness of the abdominal drawing-in maneuver (ADIM) in modulating electromyographic (EMG) activity across various muscles during different exercises in individuals with non-specific low back pain. Our findings reveal that ADIM significantly enhances EMG activity in key spinal stabilizing muscles, with notable exceptions and variations observed, which align with and expand upon previous studies. Specifically, the incorporation of ADIM into exercises such as prone trunk extension, superman, and unstable superman exercises has been shown to significantly affect muscle activation, indicating its potential utility in rehabilitation and training protocols for back pain management.

The differential impact of ADIM, particularly in the context of unstable exercise conditions, highlights the nuanced role of this maneuver in optimizing muscle function and reducing fatigue. This observation suggests that ADIM, especially when combined with exercises performed on unstable platforms, can offer enhanced therapeutic benefits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y.; methodology, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y.; software, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y.; validation, E.S.A.; formal analysis, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y.; investigation, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y.; resources, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y.; data curation, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y.; project administration, C.S., E.S.A., D.T., T.Y.S., and N.U.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Health Sciences (approval number: 2022-141; date of approval: 21.04.2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to all participants who generously contributed their time and effort to participate in this study. Special thanks are extended to the technical staff for their invaluable assistance with the electromyographic (EMG) data collection and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dolan P, Adams MA, Hutton WC. Commonly adopted postures and their effect on the lumbar spine Spine. 1988, 13, 197–201. [CrossRef]

- Kendall FP, McCreary EK, P.G. Provance Muscles: testing and function (4th ed), Williams and Wilkins, London, UK, 1993.

- Sahrmann, SA. Movement System Impairment Syndromes of the Extremities, Cervical and Thoracic Spine. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2010.

- Lewis JS, Valentine RE. Clinical measurement of the thoracic kyphosis. A study of the intra-rater reliability in subjects with and without shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskel Disord. 2010, 11, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball JM, Gagle P, Johnson BE, et al. Spinal extension exercises prevent natural progression of kyphosis. Osteopjoros Int. 2009, 20, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu J, Yeung A, Xiao T, et al. Chen-Style Tai Chi for Individuals (Aged 50 Years Old or Above) with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu KW, Maharjan S, Sornkaew K, et al. Multifidus Muscle Contractility Deficit Was Not Specific to the Painful Side in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain During Remission: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Pain Research. 2022, 15, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park KH, Oh JS, An DH, et al. Difference in selective muscle activity of thoracic erector spinae during prone trunk extension exercise in subjects with slouched thoracic posture. PM&R. 2015, 7, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim TW, Kim YW. Effects of abdominal drawing-in during prone hip extension on the muscle activities of the hamstring, gluteus maximus, and lumbar erector spinae in subjects with lumbar hyperlordosis. Sports Med Health Sci. 2015, 27, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheiro Reiser F, Gonçalves Durante B, Cordeiro de Souza W, et al. Paraspinal Muscle Activity during Unstable Superman and Bodyweight Squat Exercises. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2017, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haksever B, Soylu C, Demir P, Yildirim NU. Unraveling the Muscle Activation Equation: 3D Scoliosis-Specific Exercises and Muscle Response in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Applied Sciences. 2024, 14, 6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh JS, Cynn HS, Won JH, et al. Effects of performing an abdominal drawing-in maneuver during prone hip extension exercises on hip and back extensor muscle activity and amount of anterior pelvic tilt. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2007, 37, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Garcia FJ, Moreside JM, McGill SM. (MVC techniques to normalize trunk muscle EMG in healthy women. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2010, 20, 10–16. [CrossRef]

- Kim JS, Kang MH, Jang JH, et al. Comparison of selective electromyographic activity of the superficial lumbar multifidus between prone trunk extension and four-point kneeling arm and leg lift exercises. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015, 27, 1037–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, YW. Effects of prone trunk extension exercise using different fixations and with and without abdominal drawing-in maneuver in healthy individuals. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang YI, Park DJ. Comparison of lumbar multifidus thickness and perceived exertion during graded superman exercises with or without an abdominal drawing-in maneuver in young adults. J Exerc Rehabil. 2018, 14, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behm DG, Leonard AM, Young WB, et al. Trunk muscle electromyographic activity with unstable and unilateral exercises. J Strength Cond Res. 2005, 19, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa AC, Vieira ER, Silva AF, et al. Pilates experience vs. muscle activation during abdominal drawing-in maneuver. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018, 22, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee JK, Lee JH, Kim KS, et al. Effect of abdominal drawing-in maneuver with prone hip extension on muscle activation of posterior oblique sling in normal adults. J Phys Ther Sci. 2020, 32, 401–404. [CrossRef]

- Ishida H, Hirose R, Watanabe S. Comparison of changes in the contraction of the lateral abdominal muscles between the abdominal drawing-in maneuver and breathe held at the maximum expiratory level. Manual therapy. 2012, 17, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Diaz D, Romeu M, Velasco-Gonzalez C, et al. The effectiveness of 12 weeks of Pilates intervention on disability, pain and kinesiophobia in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2018, 32, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natour J, Cazotti Lde A, Ribeiro LH, et al. Pilates improves pain, function and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2015, 29, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges PW, Danneels L. Changes in structure and function of the back muscles in low back pain: different time points, observations, and mechanisms. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019, 49, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).