Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

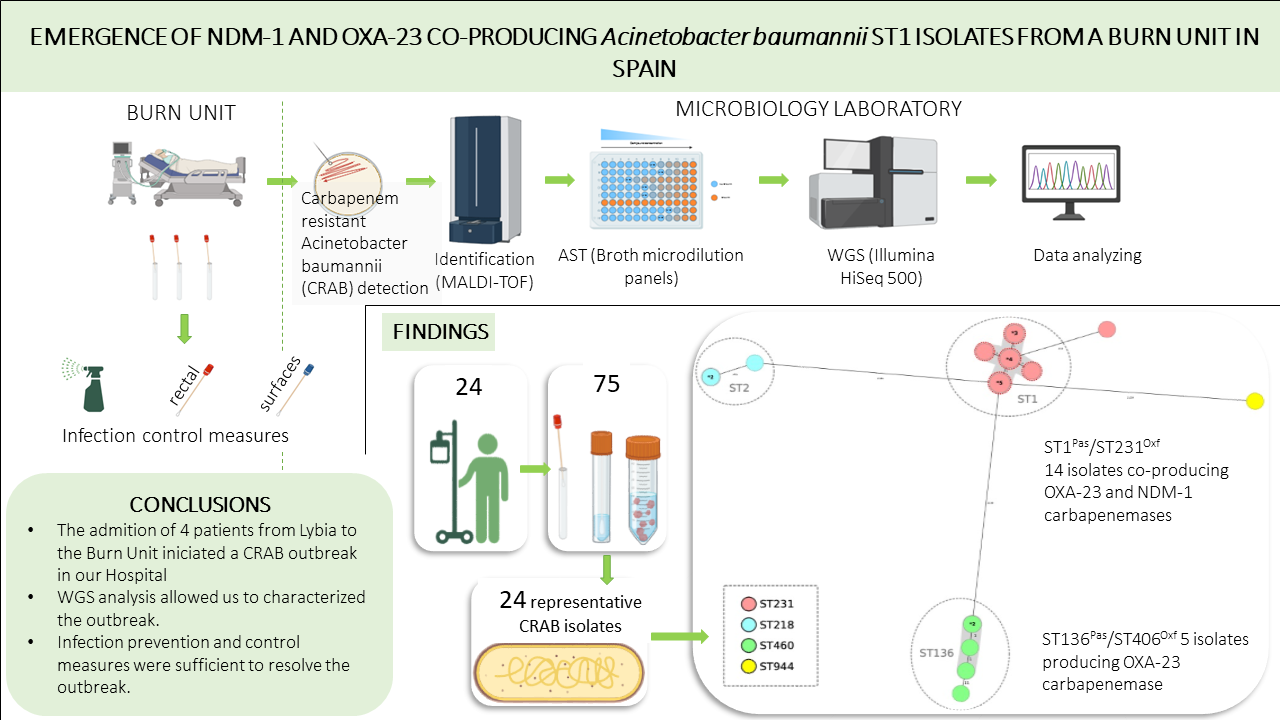

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Identification of Bacterial Isolates and Extraction of Carbapenemases Gene

2.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Tests

2.4. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Reads Assembly

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis and Diversity

2.6. Antibiotics Resistance Genes, Virulence-Associated Genes, and Plasmids

2.7. Insertion Sequences in Carbapenem-Resistant A. baumannii

3. Results

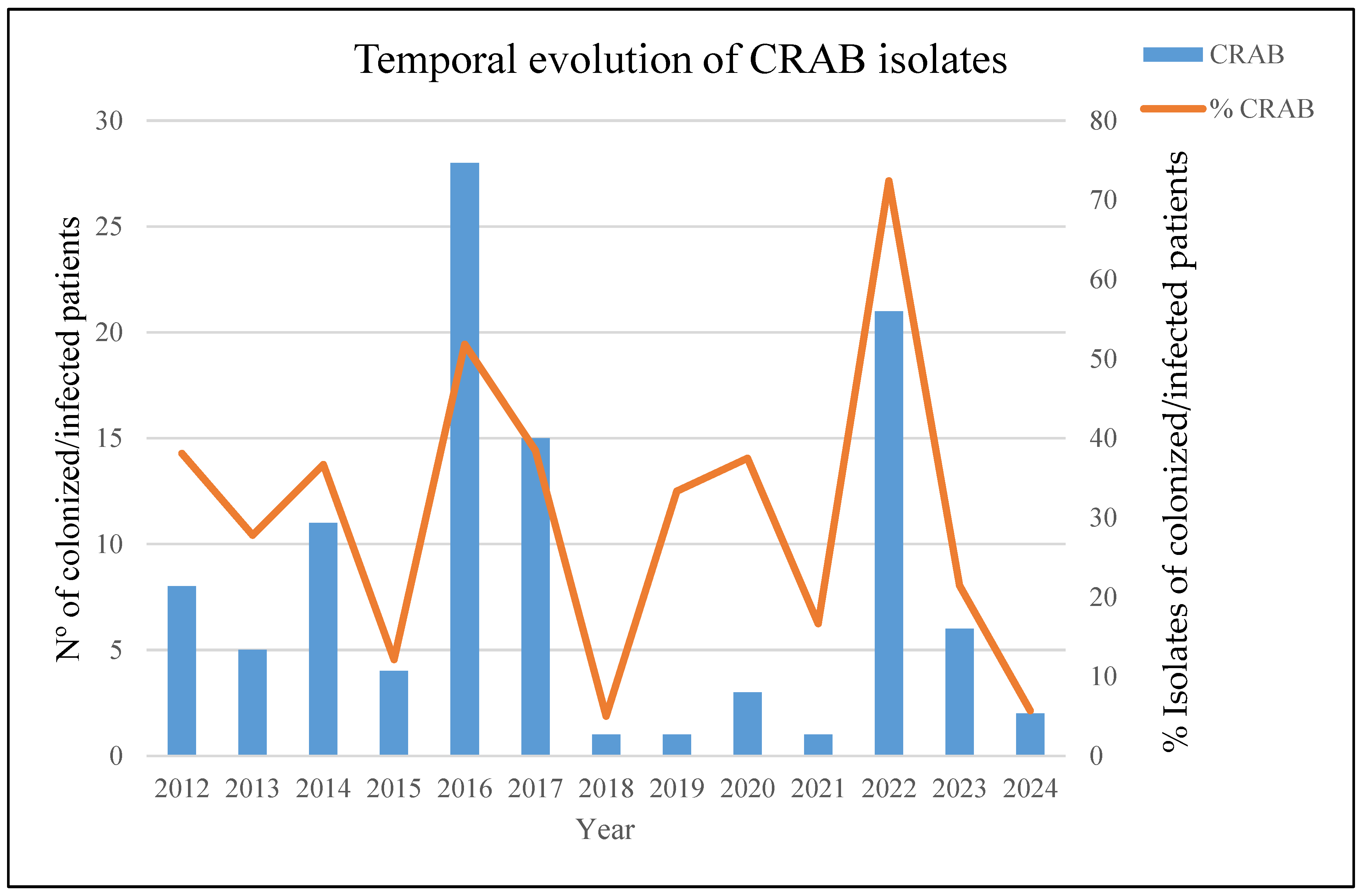

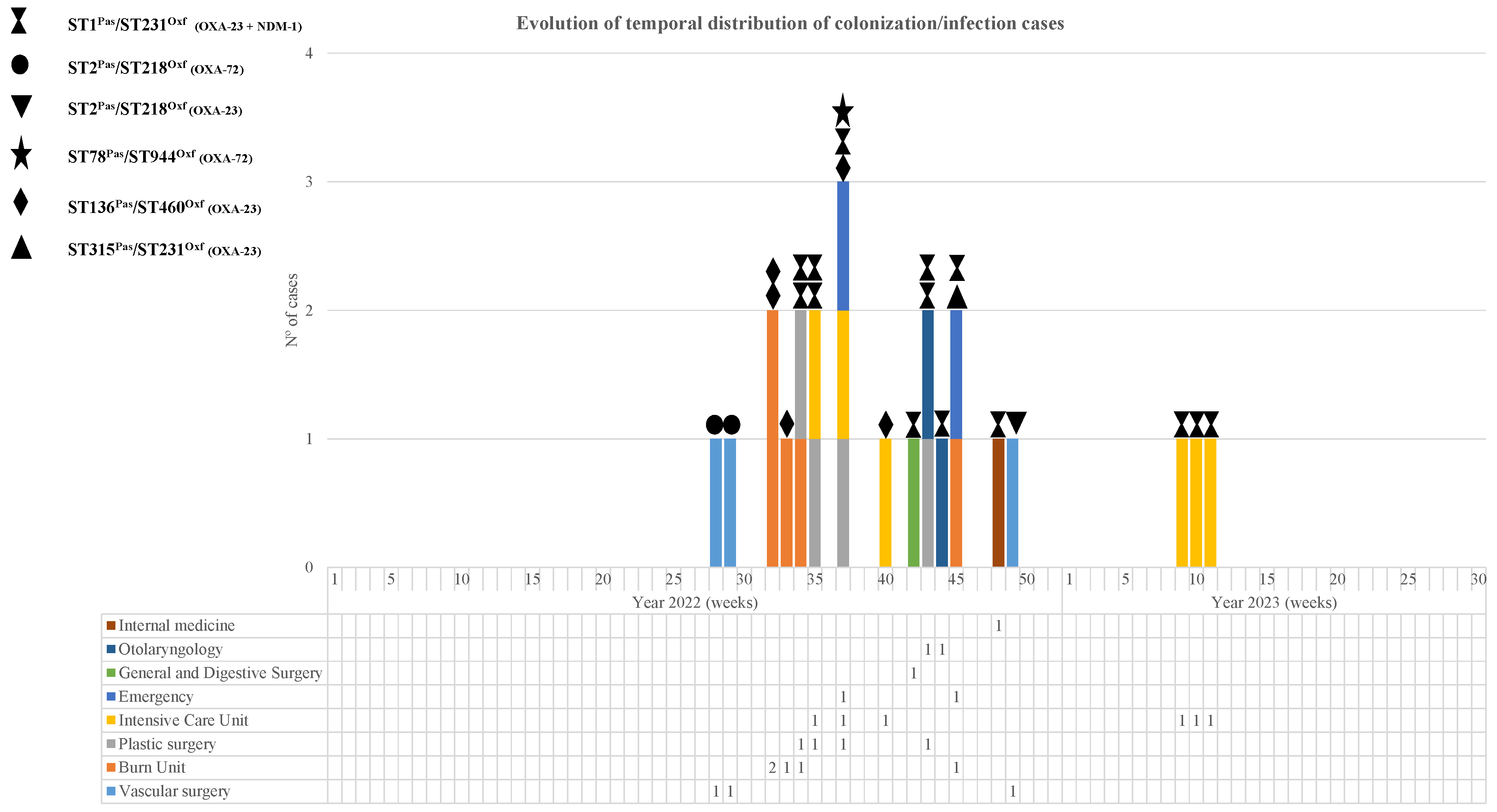

3.1. Patients and Description of the Outbreak

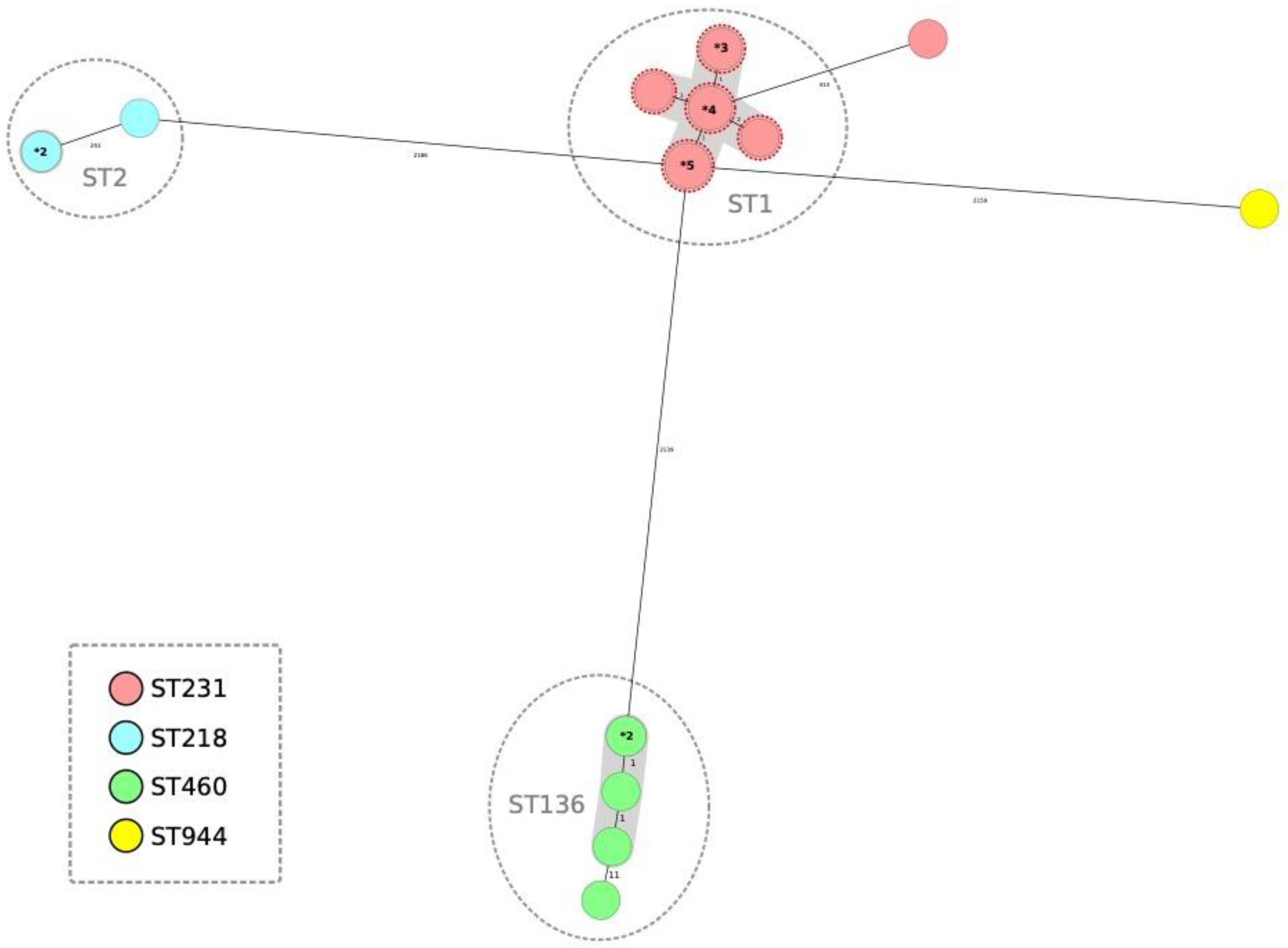

3.2. Carbapenemases Types and Phylogenetic Analysis of CRAB Isolates

3.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing of CRAB Isolates

3.4. Resistome and Virulome of Carbapenemases-Producing CRAB

3.5. Characterization of the Virulence-Associated Genes

3.6. Capsular Exopolysaccharide in CRAB Isolates

3.7. Detection of Plasmids in CRAB Isolates

3.8. Infection Control Measures and Outcome

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDRAB | Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

|

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| CRAB | Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

|

| EARS-Net | European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network |

| HUG | University Hospital Getafe |

| AST | Antibiotic susceptibility testing |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| CgMLST | Multi-Locus Sequence-Typing analysis |

| ARGs | acquired antibiotic resistance genes |

| KL | K locus |

| OCL | OC Locus |

References

- Vahhabi, A.; Hasani, A.; Rezaee, M.A.; Baradaran, B.; Hasani, A.; Samadi Kafil, H.; Abbaszadeh, F.; Dehghani, L. A Plethora of Carbapenem Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: No End to a Long Insidious Genetic Journey. J Chemother 2021, 33, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, M.; Alvi, I.A.; Rehman, S.U. Insight into Acinetobacter baumannii: Pathogenesis, Global Resistance, Mechanisms of Resistance, Treatment Options, and Alternative Modalities. Infect Drug Resist 2018, 11, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, D.; Dolma, K.G.; Khandelwal, B.; Mitsuwan, W.; Mahboob, T.; Pereira, M.L.; Nawaz, M.; Wiart, C.; Ardebili, A.; Siyadatpanah, A.; et al. Acinetobacter baumannii: An Overview of Emerging Multidrug-Resistant Pathogen. Med J Malaysia 2022, 77, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Girerd-Genessay, I.; Bénet, T.; Vanhems, P. Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Outbreaks in Burn Units: A Synthesis of the Literature According to the ORION Statement. J Burn Care Res 2016, 37, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, Research, and Development of New Antibiotics: The WHO Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and Tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2022. Antimicrobial Resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net) - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2021 2022.

- GLASS, 2019, WHO. Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. 2015.

- CAESAR, 2019.

- CHINET, 2017.

- Amudhan, M.S.; Sekar, U.; Kamalanathan, A.; Balaraman, S. Bla(IMP) and Bla(VIM) Mediated Carbapenem Resistance in Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter Species in India. J Infect Dev Ctries 2012, 6, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.U.; Maryam, L.; Zarrilli, R. Structure, Genetics and Worldwide Spread of New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase (NDM): A Threat to Public Health. BMC Microbiol 2017, 17, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Ayala, J.A.; Bonomo, R.A.; González, L.J.; Vila, A.J. Protein Determinants of Dissemination and Host Specificity of Metallo-β-Lactamases. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathlouthi, N.; El Salabi, A.A.; Ben Jomàa-Jemili, M.; Bakour, S.; Al-Bayssari, C.; Zorgani, A.A.; Kraiema, A.; Elahmer, O.; Okdah, L.; Rolain, J.-M.; et al. Early Detection of Metallo-β-Lactamase NDM-1- and OXA-23 Carbapenemase-Producing Acinetobacter baumannii in Libyan Hospitals. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2016, 48, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamar, E.; Alonso, C.A.; Ferjani, S.; Jendoubi, A.; Hamzaoui, Z.; Jebri, A.; Saidani, M.; Ghedira, S.; Torres, C.; Boubaker, I.B.-B. NDM-1- and OXA-23-Producing Acinetobacter baumannii Isolated from Intensive Care Unit Patients in Tunisia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2018, 52, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revathi, G.; Siu, L.K.; Lu, P.-L.; Huang, L.-Y. First Report of NDM-1-Producing Acinetobacter baumannii in East Africa. Int J Infect Dis 2013, 17, e1255–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwingabiye, J.; Lemnouer, A.; Roca, I.; Alouane, T.; Frikh, M.; Belefquih, B.; Bssaibis, F.; Maleb, A.; Benlahlou, Y.; Kassouati, J.; et al. Clonal Diversity and Detection of Carbapenem Resistance Encoding Genes among Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates Recovered from Patients and Environment in Two Intensive Care Units in a Moroccan Hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragueh, A.A.; Aboubaker, M.H.; Mohamed, S.I.; Rolain, J.-M.; Diene, S.M. Emergence of Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Isolates in Hospital Settings in Djibouti. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelfetouh, A.; Torky, A.S.; Aboulmagd, E. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates from Egypt. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2019, 8, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub Moubareck, C.; Hammoudi Halat, D.; Nabi, A.; AlSharhan, M.A.; AlDeesi, Z.O.; Han, A.; Celiloglu, H.; Karam Sarkis, D. Detection of OXA-23, GES-11 and NDM-1 among Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Dubai: A Preliminary Study. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2021, 24, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, K.; Thirunarayan, M.A.; Krishnan, P. Coexistence of BlaOXA-23 with BlaNDM-1 and ArmA in Clinical Isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii from India. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010, 65, 2253–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.R.; Acharya, M.; Kakshapati, T.; Leungtongkam, U.; Thummeepak, R.; Sitthisak, S. Co-Existence of BlaOXA-23 and BlaNDM-1 Genes of Acinetobacter baumannii Isolated from Nepal: Antimicrobial Resistance and Clinical Significance. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leungtongkam, U.; Thummeepak, R.; Wongprachan, S.; Thongsuk, P.; Kitti, T.; Ketwong, K.; Runcharoen, C.; Chantratita, N.; Sitthisak, S. Dissemination of BlaOXA-23, BlaOXA-24, BlaOXA-58, and BlaNDM-1 Genes of Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates from Four Tertiary Hospitals in Thailand. Microb Drug Resist 2018, 24, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizova, L.; Bonnin, R.A.; Nordmann, P.; Nemec, A.; Poirel, L. Characterization of a Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Strain Carrying the BlaNDM-1 and BlaOXA-23 Carbapenemase Genes from the Czech Republic. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012, 67, 1550–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukovic, B.; Gajic, I.; Dimkic, I.; Kekic, D.; Zornic, S.; Pozder, T.; Radisavljevic, S.; Opavski, N.; Kojic, M.; Ranin, L. The First Nationwide Multicenter Study of Acinetobacter baumannii Recovered in Serbia: Emergence of OXA-72, OXA-23 and NDM-1-Producing Isolates. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2020, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, J.S.; Jarvis, W.R.; Emori, T.G.; Horan, T.C.; Hughes, J.M. CDC Definitions for Nosocomial Infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control 1988, 16, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organization for Standardization [ISO 20776-1] (2019). Part 1.

- EUCAST. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 12.0. 2022. 2022.

- Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. M100. 33rd Edition 2023.

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving Bacterial Genome Assemblies from Short and Long Sequencing Reads. PLoS Comput Biol 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, M.; Mather, A.E.; Sánchez-Busó, L.; Page, A.J.; Parkhill, J.; Keane, J.A.; Harris, S.R. ARIBA: Rapid Antimicrobial Resistance Genotyping Directly from Sequencing Reads. Microb Genom 2017, 3, e000131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diancourt, L.; Passet, V.; Nemec, A.; Dijkshoorn, L.; Brisse, S. The Population Structure of Acinetobacter baumannii: Expanding Multiresistant Clones from an Ancestral Susceptible Genetic Pool. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartual, S.G.; Seifert, H.; Hippler, C.; Luzon, M.A.D.; Wisplinghoff, H.; Rodríguez-Valera, F. Development of a Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme for Characterization of Clinical Isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 4382–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucidi, M.; Visaggio, D.; Migliaccio, A.; Capecchi, G.; Visca, P.; Imperi, F.; Zarrilli, R. Pathogenicity and Virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii: Factors Contributing to the Fitness in Healthcare Settings and the Infected Host. Virulence 2024, 15, 2289769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Vazquez, M.; Oteo-Iglesias, J.; Sola-Campoy, P.J.; Carrizo-Manzoni, H.; Bautista, V.; Lara, N.; Aracil, B.; Alhambra, A.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; Campos, J.; et al. Characterization of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella oxytoca in Spain, 2016-2017. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019, 63, e02529–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K.L.; Cahill, S.M.; Holt, K.E.; Hall, R.M.; Kenyon, J.J. Identification of Acinetobacter Baumannii Loci for Capsular Polysaccharide (KL) and Lipooligosaccharide Outer Core (OCL) Synthesis in Genome Assemblies Using Curated Reference Databases Compatible with Kaptive. Microb Genom 2020, 6, e000339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkey, J.; Hamidian, M.; Wick, R.R.; Edwards, D.J.; Billman-Jacobe, H.; Hall, R.M.; Holt, K.E. ISMapper: Identifying Transposase Insertion Sites in Bacterial Genomes from Short Read Sequence Data. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.D.; Bishop, B.; Wright, M.S. Quantitative Assessment of Insertion Sequence Impact on Bacterial Genome Architecture. Microb Genom 2016, 2, e000062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, K.E.; Hamidian, M.; Kenyon, J.J.; Wynn, M.T.; Hawkey, J.; Pickard, D.; Hall, R.M. Genome Sequence of Acinetobacter baumannii Strain A1, an Early Example of Antibiotic-Resistant Global Clone 1. Genome Announc 2015, 3, e00032–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, C.-K.; Lee, H.; Jeong, S.H.; Yong, D.; Lee, K. A Novel Insertion Sequence, ISAba10, Inserted into ISAba1 Adjacent to the Bla(OXA-23) Gene and Disrupting the Outer Membrane Protein Gene CarO in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 361–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smani, Y.; Fàbrega, A.; Roca, I.; Sánchez-Encinales, V.; Vila, J.; Pachón, J. Role of OmpA in the Multidrug Resistance Phenotype of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 1806–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ni, Z.; Tang, J.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, F. The AbaI/AbaR Quorum Sensing System Effects on Pathogenicity in Acinetobacter baumannii. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 679241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, A.H.K.; Slamti, L.; Avci, F.Y.; Pier, G.B.; Maira-Litrán, T. The PgaABCD Locus of Acinetobacter baumannii Encodes the Production of Poly-Beta-1-6-N-Acetylglucosamine, Which Is Critical for Biofilm Formation. J Bacteriol 2009, 191, 5953–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neres, J.; Wilson, D.J.; Celia, L.; Beck, B.J.; Aldrich, C.C. Aryl Acid Adenylating Enzymes Involved in Siderophore Biosynthesis: Fluorescence Polarization Assay, Ligand Specificity, and Discovery of Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors via High-Throughput Screening. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 11735–11749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaras, A.P.; Dorsey, C.W.; Edelmann, R.E.; Actis, L.A. Attachment to and Biofilm Formation on Abiotic Surfaces by Acinetobacter baumannii: Involvement of a Novel Chaperone-Usher Pili Assembly System. Microbiology (Reading) 2003, 149, 3473–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; De Silva, P.M.; Al-Saadi, Y.; Switala, J.; Loewen, P.C.; Hausner, G.; Chen, W.; Hernandez, I.; Castillo-Ramirez, S.; Kumar, A. Characterization of Extremely Drug-Resistant and Hypervirulent Acinetobacter baumannii AB030. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lötsch, F.; Albiger, B.; Monnet, D.L.; Struelens, M.J.; Seifert, H.; Kohlenberg, A. ; European Antimicrobial Resistance Genes Surveillance Network (EURGen-Net) carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii capacity survey group; EURGen-Net carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii capacity survey group Epidemiological Situation, Laboratory Capacity and Preparedness for Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Europe, 2019. Euro Surveill 2020, 25, 2001735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doughty, E.L.; Liu, H.; Moran, R.A.; Hua, X.; Ba, X.; Guo, F.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Holmes, M.; van Schaik, W.; et al. Endemicity and Diversification of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in an Intensive Care Unit. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2023, 37, 100780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medioli, F.; Bacca, E.; Faltoni, M.; Burastero, G.J.; Volpi, S.; Menozzi, M.; Orlando, G.; Bedini, A.; Franceschini, E.; Mussini, C.; et al. Is It Possible to Eradicate Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) from Endemic Hospitals? Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedenić, B.; Bratić, V.; Mihaljević, S.; Lukić, A.; Vidović, K.; Reiner, K.; Schöenthaler, S.; Barišić, I.; Zarfel, G.; Grisold, A. Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria in a COVID-19 Hospital in Zagreb. Pathogens 2023, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Qiao, F.; Cai, L.; Zong, Z.; Zhang, W. Effect of Daily Chlorhexidine Bathing on Reducing Infections Caused by Multidrug-Resistant Organisms in Intensive Care Unit Patients: A Semiexperimental Study with Parallel Controls. J Evid Based Med 2023, 16, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangioni, D.; Fox, V.; Chatenoud, L.; Bolis, M.; Bottino, N.; Cariani, L.; Gentiloni Silverj, F.; Matinato, C.; Monti, G.; Muscatello, A.; et al. Genomic Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) in Mechanically Ventilated COVID-19 Patients and Impact of Infection Control Measures on Reducing CRAB Circulation during the Second Wave of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Milan, Italy. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e0020923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Deng, C.; Yang, G.; Shen, M.; Chen, B.; Tian, R.; Zha, H.; Wu, K. Molecular Epidemiology and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates from Patients Admitted at ICUs of a Teaching Hospital in Zunyi, China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1280372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Reuter, S.; Wille, J.; Xanthopoulou, K.; Stefanik, D.; Grundmann, H.; Higgins, P.G.; Seifert, H. A Global View on Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. mBio 2023, e0226023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, H.; Ahmad, M.; Younas, S.; Junaid, K.; Abosalif, K.O.A.; Abdalla, A.E.; Alameen, A.A.M.; Elamir, M.Y.M.; Bukhari, S.N.A.; Ahmad, N.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Extensively-Drug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Sequence Type 2 Co-Harboring Bla NDM and Bla OXA From Clinical Origin. Infect Drug Resist 2021, 14, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choby, J.E.; Ozturk, T.; Satola, S.W.; Jacob, J.T.; Weiss, D.S. Widespread Cefiderocol Heteroresistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens. Lancet Infect Dis 2021, 21, 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahryari, S.; Mohammadnejad, P.; Noghabi, K.A. Screening of Anti-Acinetobacter baumannii Phytochemicals, Based on the Potential Inhibitory Effect on OmpA and OmpW Functions. R Soc Open Sci 2021, 8, 201652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioy, V.S.; Goussard, S.; Guerineau, V.; Yoon, E.-J.; Courvalin, P.; Galimand, M.; Grillot-Courvalin, C. Aminoglycoside Resistance 16S RRNA Methyltransferases Block Endogenous Methylation, Affect Translation Efficiency and Fitness of the Host. RNA 2014, 20, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, K.J.; Rather, P.N.; Hare, R.S.; Miller, G.H. Molecular Genetics of Aminoglycoside Resistance Genes and Familial Relationships of the Aminoglycoside-Modifying Enzymes. Microbiol Rev 1993, 57, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed-Ahmed, M.A.E.-G.; Amin, M.A.; Tawakol, W.M.; Loucif, L.; Bakour, S.; Rolain, J.-M. High Prevalence of Bla(NDM-1) Carbapenemase-Encoding Gene and 16S RRNA ArmA Methyltransferase Gene among Acinetobacter baumannii Clinical Isolates in Egypt. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 3602–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Urtaza, S.; Ocampo-Sosa, A.; Molins-Bengoetxea, A.; El-Kholy, M.A.; Hernandez, M.; Abad, D.; Shawky, S.M.; Alkorta, I.; Gallego, L. Molecular Characterization of Multidrug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Clinical Isolates from Alexandria, Egypt. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1208046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genteluci, G.L.; de Souza, P.A.; Gomes, D.B.C.; Sousa, V.S.; de Souza, M.J.; Abib, J.R.L.; de Castro, E.A.R.; Rangel, K.; Villas Bôas, M.H.S. Polymyxin B Heteroresistance and Adaptive Resistance in Multidrug- and Extremely Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Curr Microbiol 2020, 77, 2300–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschiari, M.; Lòpez-Lozano, J.-M.; Di Pilato, V.; Gimenez-Esparza, C.; Vecchi, E.; Bacca, E.; Orlando, G.; Franceschini, E.; Sarti, M.; Pecorari, M.; et al. A Five-Component Infection Control Bundle to Permanently Eliminate a Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Spreading in an Intensive Care Unit. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghnieh, R.A.; Kanafani, Z.A.; Tabaja, H.Z.; Sharara, S.L.; Awad, L.S.; Kanj, S.S. Epidemiology of Common Resistant Bacterial Pathogens in the Countries of the Arab League. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, e379–e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-Y.; Apisarnthanarak, A.; Khan, E.; Suwantarat, N.; Ghafur, A.; Tambyah, P.A. Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Enterobacteriaceae in South and Southeast Asia. Clin Microbiol Rev 2017, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wareth, G.; Linde, J.; Nguyen, N.H.; Nguyen, T.N.M.; Sprague, L.D.; Pletz, M.W.; Neubauer, H. WGS-Based Analysis of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Vietnam and Molecular Characterization of Antimicrobial Determinants and MLST in Southeast Asia. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldali, J.A. Acinetobacter baumannii: A Multidrug-Resistant Pathogen, Has Emerged in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2023, 44, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcone, M.; Tiseo, G.; Carbonara, S.; Marino, A.; Di Caprio, G.; Carretta, A.; Mularoni, A.; Mariani, M.F.; Maraolo, A.E.; Scotto, R.; et al. Mortality Attributable to Bloodstream Infections Caused by Different Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli: Results From a Nationwide Study in Italy (ALARICO Network). Clin Infect Dis 2023, 76, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goic-Barisic, I.; Music, M.S.; Drcelic, M.; Tuncbilek, S.; Akca, G.; Jakovac, S.; Tonkić, M.; Hrenovic, J. Molecular Characterisation of Colistin and Carbapenem-Resistant Clinical Isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii from Southeast Europe. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2023, 33, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, R.M.; Janssen, H.; Hey-Hadavi, J.H.; Hackel, M.; Sahm, D. Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli Recovered from Respiratory and Blood Specimens from Adults: The ATLAS Surveillance Program in European Hospitals, 2018-2020. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2023, 61, 106724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, S.; Adler, A. Introduction and Spread of NDM-Producing Enterobacterales and Acinetobacter baumannii into Middle Eastern Countries: A Molecular-Based Hypothesis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2023, 21, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandfort, M.; Hans, J.B.; Fischer, M.A.; Reichert, F.; Cremanns, M.; Eisfeld, J.; Pfeifer, Y.; Heck, A.; Eckmanns, T.; Werner, G.; et al. Increase in NDM-1 and NDM-1/OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Germany Associated with the War in Ukraine, 2022. Euro Surveill 2022, 27, 2200926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Microbiological data of patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Age | Sex | Date of first isolation | Sample | Diagnostic /colonization | Clinical Ward where the sample was obtained |

| 1 | 72 | M | 07/07/2022 | Biopsy | Diagnostic | Vascular surgery |

| 2 | 89 | M | 14/07/2022 | Abscess/Pus | Diagnostic | Vascular surgery |

| 3 | 35 | M | 06/08/2022 | Burn exudate | Colonization | Burn Unit |

| 4 | 24 | M | 06/08/2022 | Tracheal aspirate | Diagnostic | Burn Unit |

| 5 | 19 | M | 14/08/2022 | Tracheal aspirate | Diagnostic | Burn Unit |

| 6 | 32 | M | 15/08/2022 | Tracheal aspirate | Diagnostic | Burn Unit |

| 7 | 50 | M | 17/08/2022 | Catheter | Diagnostic | Plastic surgery |

| 8 | 50 | M | 25/08/2022 | Catheter | Diagnostic | Plastic surgery |

| 9 | 78 | M | 25/08/2022 | Blood | Diagnostic | Intensive Care Unit |

| 10 | 68 | M | 05/09/2022 | Burn exudate | Diagnostic | Plastic surgery |

| 11 | 84 | F | 09/09/2022 | Aspirate puncture | Diagnostic | Intensive Care Unit |

| 12 | 82 | F | 11/09/2022 | Surgical wound exudate | Diagnostic | Emergency |

| 13 | 90 | M | 28/09/2022 | Blood | Diagnostic | Intensive Care Unit |

| 14 | 46 | F | 13/10/2022 | Rectal swab | Colonization | General and digestive surgery |

| 15 | 78 | M | 19/10/2022 | Abscess/Pus | Diagnostic | Otolaryngology |

| 16 | 79 | F | 21/10/2022 | Rectal swab | Colonization | Plastic surgery |

| 17 | 63 | F | 27/10/2022 | Rectal swab | Colonization | Otolaryngology |

| 18 | 61 | F | 03/11/2022 | Rectal swab | Colonization | Burn Unit |

| 19 | 43 | F | 06/11/2022 | Skin and soft tissue exudate | Diagnostic | Emergency |

| 20 | 19 | F | 24/11/2022 | Rectal swab | Colonization | Internal medicine |

| 21 | 57 | F | 01/12/2022 | Non-surgical wound exudate | Diagnostic | Vascular surgery |

| 22 | 52 | F | 21/02/2023 | Rectal swab | Colonization | Intensive Care Unit |

| 23 | 78 | M | 28/02/2023 | Tracheal aspirate | Diagnostic | Intensive Care Unit |

| 24 | 64 | F | 03/03/2023 | Tracheal aspirate | Diagnostic | Intensive Care Unit |

| Antibiotics. | *S % Total isolates (n) | *I % Total isolates (n) | *R % Total isolates (n) | MIC50 | MIC90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amikacin | 4.2 (1) | - | 95.8 (23) | 32 | 32 |

| Cefiderocol** | 83.3 (20) | - | 16.7 (4) | - | - |

| Ceftazidime | 0 | - | 100 (24) | >16 | >16 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0 | - | 100 (24) | >2 | >2 |

| Colistin | 91.6 (22) | - | 8.3 (2) | 1 | 1 |

| Gentamicin | 0 | - | 100 (24) | >8 | >8 |

| Imipenem | 0 | - | 100 (24) | >16 | >16 |

| Meropenem | 0 | - | 100 (24) | >16 | >16 |

| Piperaciclin/Tazobactam | 0 | - | 100 (24) | >32/4 | >32/4 |

| Tobramycin | 0 | - | 100 (24) | >8 | >8 |

| Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole | 0 | 12.5 (3) | 87.5 (21) | >8/152 | >8/152 |

| *S: Susceptibility. *R: Resistance. *I Susceptible increased exposure. | |||||

| **Disc diffusion method (30µg) on plate. It is considered susceptible with a zone diameter of ≥17 mm according to PK-PD breakpoint. | |||||

| Isolate | Pasteur ST | Oxford ST | Acquired β-lactamase | Chromosomal β-lactamase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbapenemase | Carbapenemase | AmpC | |||

| 1 | 2 | 218 | blaOXA-72 | blaOXA-66 | blaADC-30 |

| 2 | 2 | 218 | blaOXA-72 | blaOXA-66 | blaADC-30 |

| 3 | 136 | 460 | blaOXA-23 | blaOXA-409 | blaADC-88 |

| 4 | 136 | 460 | blaOXA-23 | blaOXA-409 | blaADC-88 |

| 5 | 136 | 460 | blaOXA-23 | blaOXA-409 | blaADC-88 |

| 6 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 7 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 8 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 9 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 10 | 136 | 460 | blaOXA-23 | blaOXA-409 | blaADC-88 |

| 11 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 12 | 78 | 944 | blaOXA-72 | blaOXA-90 | blaADC-152 |

| 13 | 136 | 460 | blaOXA-23 | blaOXA-409 | blaADC-88 |

| 14 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 15 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 16 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 17 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 18 | 315 | 231 | blaOXA-23 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-79 |

| 19 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 20 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 21 | 2 | 218 | blaOXA-23 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-30 |

| 22 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 23 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

| 24 | 1 | 231 | blaOXA-23blaNDM-1 | blaOXA-69 | blaADC-191 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).